ContentslistsavailableatSciVerseScienceDirect

Industrial

Crops

and

Products

j o u r n al hom ep a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / i n d c r o p

Fractioning

and

chemical

characterization

of

barks

of

Betula

pendula

and

Eucalyptus

globulus

Isabel

Miranda,

Jorge

Gominho

∗,

Inês

Mirra,

Helena

Pereira

CentrodeEstudosFlorestais,InstitutoSuperiordeAgronomia,UniversidadeTécnicadeLisboa,TapadadaAjuda,1349-017Lisboa,Portugal

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received17February2012 Receivedinrevisedform3April2012 Accepted14April2012

Keywords: BetulapendulaRoth. EucalyptusglobulusLabill. Bark

Particlesize Chemicalcomposition

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Thecompositionofbirch(BetulapendulaRoth.)andeucalypt(EucalyptusglobulusLabill.)barkswas studiedaftergrindingandfractioningintodifferentparticlessizes.

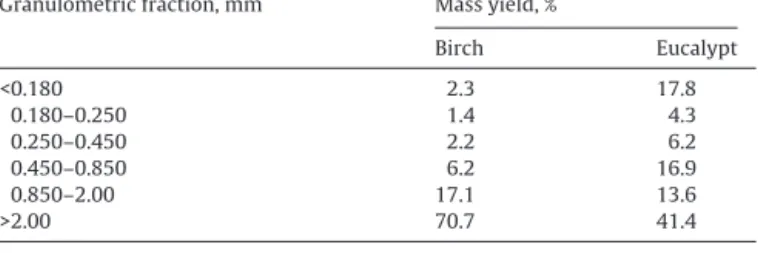

Therewasasignificantdifferenceinthefractionationofbothbarksinrelationtotheyieldoffines(5.9% and28.3%ofparticlesunder0.450forbirchandeucalypt,respectively)andofcoarserparticlesover2mm (70.7%and41.4%).

Thechemicalcompositionofbirchandeucalyptbarks,asamassweighedaverageofallgranulometric fractionswas,respectively:ash2.9%and12.1%;totalextractives17.6%and6.5%(hydrophilicextractives weredominant),lignin27.9%and28.8%andholocellulose49.8%and62.6%.Birchbarkcontaineda con-siderableamountofsuberin(5.9%)whereaseucalyptbarkcontainedaverysmallamount(<1%).The carbohydratecompositiondifferedbetweenbirchandeucalyptbarks,i.e.,respectively,glucose47.0% and68.4%,andxylose33.8%and23.2%oftotalneutralmonosaccharides.

Ashelementalcompositionwasdifferentinbothspecies.Birchbarkcontainedinrelationtoeucalypt bark,inthe0.250–0.450mmfraction,moreN(0.69%vs.0.26%)andP(0.075%vs.0.001%),andlessCa (0.39%vs.0.62%),K(0.24%vs.0.31%)andMg(0.07%vs.0.15%).HighconcentrationofZnwasfoundin birchbark(217mg/kgvs.11mg/kgineucalyptbark).

Aftergrindingandgranulometricseparation,extractiveswerepresentpreferentiallyinthefinest frac-tionwithanenrichmentindichloromethaneandethanolsolublesespeciallyinthecaseofbirchbark. Eucalyptbarkhadahighcontentofcelluloseandhemicellulosesespeciallyinthecoarserfraction.The fibrouscharacterofthisfractionshowsitspotentialasafibersource.

© 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Barkrepresentsasubstantialproportion oftheaboveground

totalbiomassoftrees.Duringindustrialprocessingfortimberorfor

pulping,barkisremovedfromthelogsandconstitutesanimportant

millresidualmaterialthatisusuallyburntforenergyproduction.

Inaddition tobeingconsidereda valuablesolid biofuel,barkis

alsoscrutinizedformoreadded-valueproductsthatwillconsider

potentialspecificchemicalcompositionorproperties(Demirbas,

2010).

Barkvalorization,namelyifenvisagedwithinabiorefinery

plat-form,thereforerequiresacarefulexaminationofcompositionand

processing characteristics.Barks areusually rich in extractives,

includingorganicsolventandwatersolubles,andin

polypheno-lics,and theyalsocontaina highamountof inorganicmaterial

(FengelandWegener,1984;Pereiraetal.,2003).Structurallybarks

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:jgominho@isa.utl.pt(J.Gominho).

arecomplextissuesandtheirsampling,characterizationand

pro-cessinghavedifficultiesthatarenotfound,e.g.inwoodprocessing.

Hardwoodspeciesarepresentlythemostimportantsourceof

woodforpulpproduction(Pattetal.,2006).Whitebirch(Betula

pendula) is thedominant pulpwood species in Northern

Euro-peancountries(especially inFinlandand Russia)and eucalypts

(mainlyEucalyptusglobulus)aredominantinPortugalandSpain,

in Southern Europe. The pulpwood consumption in Europe in

2010ofbirchandeucalyptwas,respectively,18425millionm3and

13708millionsm3,correspondingto12.5%and9.3%ofthetotal

pulpwoodconsumption(CEPI,2010).

Inbothcasesconsiderableamountsofbarkaremadeavailable

fromlogdebarking, and areseparated inthemillas aresidual

productandusedasfuel.

InE.globulustreesattheageusedforpulping(9–13yearsin

temperateclimates)barkhasathicknessintherangeof3–16mm

andcorrespondsto7–20%ofo.d.massofthestemdependingon

siteandgenetics(ascompiledinPereiraetal.,2010).

TherearefewstudiesonB.pendulabarkcontent.Jensen(1948)

reported3.4%outerbarkinbirchlogs.Bhat(1982)referredthatbark

thicknessisstronglyassociatedwithstemdiameterandreported

0926-6690/$–seefrontmatter © 2012 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.04.024

ameanvalueof16.6mmforthedoublebarkthicknessoftrees

aged65–95years.Repola(2008)reportedadoublebarkthickness

atbreastheightbetween2.5and38.7cmintreeswithinanage

rangeof7and132years.Foryoungtreeswith1–16yearsofage

and0.3–24.0cmstemdiameter,Trockenbrodt(1991)reportedbark

thicknessvaluesbetween7.1and26.1mm.

Somestudieshave characterizedeucalypt barkanatomically

(Quilhóetal.,1999,2000)andchemically(Sakai,2001;Bargatto,

2010)aswellasbirchbark(Bhat,1982;Trockenbrodt,1991;Harkin

and Rowe,1971). Howeverlittle is known ontheirfractioning

behaviorandonthechemicalcharacteristicsofdifferentfractions.

Theuseoffractioningisusuallyinvolved inbiomassprocessing

andmaybeusedforselectiveenrichmentofspecificcomponents

bytakingadvantageofthebiomasschemicalandstructural

het-erogeneity(Mirandaetal.,2012;Silvaetal.,2011).However,this

isspeciesspecificanddependsonthespecificbarkcharacteristics,

asrecentlyshownforPiceaabies,PinussylvestrisandQuercuscerris

(Mirandaetal.,2012;Senetal.,2010).

Thispaperstudiesthechemical composition ofthebarks of

thesetwo importantEuropeanhardwoods, silver birch(B.

pen-dula)andTasmanianbluegum(E.globulus),obtainedasresidual

by-productsofcommercialdebarkinginpulpmills,after

fractiona-tionintodifferentparticlesizes.Summativechemicalanalysisand

inorganiccompositionwere determinedfor eachgranulometric

fraction,aswellasbulk density.Theobjectiveistoanalyzethe

potentialoftrituratingandparticlefractioningasabiomass

pre-treatmentstepforaselectivecomponentenrichmentwithinabark

valorizationchainforenergy,compositematerialsandchemicals.

2. Materialsandmethods

2.1. Sampling

Barksfrombirch(B.pendula Roth)and eucalypt(E. globulus

Labill.)wereobtainedbyindustrialstemdebarkinginpulpmills,

andwereprovidedbySödra(Sweden)andCelbi(Portugal),

respec-tively.Thebulkbarksampleswereair-driedatambientconditions

andanyvisiblewoodchipswereremoved.

2.2. Fractioning

Thebarkswerefractionatedusingaknifemill(RetschSM2000)

withan outputsieve of 10mm×10mm and screened using a

vibratorysievingapparatus(RetschAS200basic).Thefollowing

sievemesh sizeswereused: 80(0.180mm),60(0.250mm),40

(0.450mm),20(0.850m),15(1.0mm)and10(2.0mm).Themass

ofthefractionretainedoneachsievewasweighedandthe

corre-spondingsevenmassfractionsyieldsweredetermined.

2.3. Bulkdensity

Thebulk densityof thegranulatedsampleswasdetermined

for each sieve fraction using a cylindrical container (29.8mm

height×28.1mmdiameter)astheratioofthemasssampleinthe

containertothevolumeofthecontainer.Thedeterminationwas

madeintriplicatesamples.

2.4. Microscopicobservations

Thedifferentgranulometricfractionsofthebarksampleswere

observedmicroscopicallyaftercelldissociationbymacerationin

a1:1glacialaceticacid:hydrogenperoxidesolution,andstaining

withastrablue.

2.5. Chemicalcharacterization

Chemicalsummativeanalysisincludeddeterminationof ash,

extractives soluble in dichloromethane, methanol, ethanol and

water,suberin,Klasonandacidsolublelignin,andholocellulose,

aswellasthemonomericcompositionofpolysaccharides.

Thegranulometricfractions withparticlesizeover 40 mesh

werecarefullygroundpriortochemicalanalysisinordertoobtain

particlesthatpassedthroughthe40meshsieve.

Theunextractedbarksampleswereusedtodetermine1%NaOH

solubles.

AshcontentwasdeterminedaccordingtoTAPPIStandardT15

os-58using2.0gsamplesastheresidueofovernightincineration

at450–500◦C.

The alkaline lixiviation with1% NaOH was carried out in a

stirredglassreactorwithrefluxusing1.0gofmaterialwitha1:50

solid:liquidratio,at100◦Cduring1h.

SolventextractionwasperformedinaSoxtecextractor

succes-sivelywithdichloromethane,methanol,ethanolandwaterduring

1.5hwitheachsolvent,andtheextractivessolubilizedbyeach

sol-ventweredeterminedusingthemassdifferencefromthemassof

thesolidresidueafterdryingat105◦Candreportedasapercentage

oftheoriginalsamples.

Suberin content was determined on 1.5g of extractive-free

material by refluxing with100ml of a 3% NaOCH3 solution in

CH3OH during 3h (Pereira, 1988a). The sample was filtrated,

washed withmethanol, again refluxed with100ml CH3OH for

15minandfiltrated.ThecombinedfiltrateswereacidifiedtopH

6with2MH2SO4andevaporatedtodryness.Theresiduewas

sus-pendedin50mlwaterandthealcoholysisproductsrecoveredwith

dichloromethaneinthreesuccessiveextractions,eachwith50ml

dichloromethane.Thecombinedextractsweredriedover

anhy-drousNa2SO4andevaporatedtodryness.Thesuberinextracts,that

includethefattyacidandfattyalcoholmonomersofsuberin,were

quantifiedgravimetrically,andtheresultsexpressedinpercentof

theinitialdrymass.

Klason and acid-soluble lignin, and carbohydrates contents

weredeterminedon0.35gofextractedanddesuberinized

sam-ples.Sulfuricacid(72%,3.0ml)wasaddedtothesampleandthe

mixtureplacedinawaterbathat30◦Cfor1hafterwhichthe

sam-plewasdilutedtoaconcentrationof3%H2SO4andhydrolyzedfor

1hat120◦C.Thesamplewasvacuum-filteredthroughacrucible

andwashedwithboilingpurifiedwater.Klasonligninwas

deter-minedasthemassofthesolidresidueafterdryingat105◦Cand

acid-solubleligninwasdeterminedonthefiltratebymeasuring

theabsorbanceat206nmusingaUV/VISspectrophotometer.

Kla-sonligninandacid-solubleligninwerereportedaspercentageof

theoriginalsampleandcombinedtogivethetotallignincontent.

Thepolysaccharideswerecalculatedbasedontheamountofthe

neutralsugarmonomersreleasedbytotalhydrolysis,after

deriva-tizationasalditolacetatesandseparationbygaschromatography

withamethodadaptedfromTappi249cm-00.Thehydrolyzed

car-bohydrateswerederivatizedasalditolacetatesandseparatedbyGC

(HP5890Agaschromatograph)equippedwithaFIDdetector,using

heliumascarriergas(1ml/min)andafusedsilicacapillarycolumn

S2330(30m×0.32mmi.d.×0.20mfilmthickness).Thecolumn

programtemperaturewas225–250◦C,with5◦C/minheating

gra-dient,andthetemperatureofinjectoranddetectorwas250◦C.For

quantitativeanalysistheGCwascalibratedwithpurereference

compoundsandinositolwasusedasaninternalstandardineach

run.

Theholocellulosecontentwasdeterminedonthe

extractive-freesamplesbythechloritemethod(Rowell,2005):1gofsample

wasplacedinanErlenmeyerflask(300ml)and32mlofdistilled

water wasadded.While slowlyshaking, 0.750gof NaClO2 and

Table1

Massyields(%oftotaldrymass)ofthedifferentgranulometricfractionsaftermilling ofbarks.

Granulometricfraction,mm Massyield,%

Birch Eucalypt <0.180 2.3 17.8 0.180–0.250 1.4 4.3 0.250–0.450 2.2 6.2 0.450–0.850 6.2 16.9 0.850–2.00 17.1 13.6 >2.00 70.7 41.4

glassandboiledat70–80◦Cfor60min.Again,0.750gofNaClO2

and0.3mlofaceticacidwereaddedandboiled3times.After

cool-ing,thesamplewasfilteredusingafilterflaskandwashedwith

coldwaterandacetone50%untilfreeofacid.Theinsolubleportion

wasdriedat105◦Cfor4h,cooledinadesiccatorandweigheduntil

constantweight.Theashcontentoftheobtainedholocellulosewas

determinedbyincinerationandtheash-freeholocellulosecontent

wascalculatedaspercentofdrymassoftheinitialsample.

2.6. Ashcomposition

Nitrogen wasdetermined by the Kjeldahl method (Jackson,

1958)inaTecatorequipment(Herdon,VA,USA).Aftera

hydrochlo-ricdigestionoftheash(MartiandMu ˜noz,1957),phosphoruswas

determined by molecularabsorption spectrometryin a Hitachi

U-2000VIS/UVequipment,andalltheothermineralswere

deter-minedbyatomicabsorptionspectrophotometerinaPyeUnicam

SP-9apparatus(Cambridge,UK)equippedwithagraphitefurnace

GF95.

3. Resultsanddiscussion

3.1. Barkfractioning

Thebarksofbirch(B.pendulaRoth.)andeucalypt(E.globulus

Labill.)weremilledandthemassyieldsobtainedforthedifferent

granulometricfractionsaresummarizedinTable1.

Therewasasignificantdifferenceinthefractionationofboth

barks.Forbirchbarktheyieldoffineswaslow,i.e.only5.9%were

particlesunder0.450mm,andthemajorfractioncorrespondedto

thelargestparticles,i.e.70.7%ofparticlesover2mm.Thisgrinding

behaviorwithlittleformationoffineswasalsofoundforconifer

barksofPinuspinaster(Vázquezetal.,1987), P.sylvestrisand P.

abies(Mirandaetal.,2012).

Onthecontrary,inthecaseofeucalyptbarkasignificantamount

offineswasobtainedwith17.8%ofparticlesunder0.180mmand

thefractionswiththelargerparticlesshowedcomparativelylower

yields(e.g.41%forparticlesover2mm).

Theseresultsshowthatthemillingprocessappliesdifferently

todifferentbarksand thebarkstructuralfeaturesinfluencethe

grindingbehavior.Barksaremadeupofdifferenttissues–phloem,

peridermandrhytidome–invaryingextentandcellular

charac-teristics.

Inthecaseofeucalyptbark,thereisnorhytidome,sinceolder

peridermsaresheddedoutbythetreeandonlyathinperiderm

coversthephloem(Quilhóetal.,2000).Thephloemisrather

uni-formandischaracterizedbytangentiallayersofaxialparenchyma

cellsthatareinterspersedbyregionsoffibers,representing,

respec-tively,50%and28%ofthetotalcross-sectionalarea(Quilhóetal.,

1999,2000).Itis therefore understandable thatfracture occurs

preferentiallybythefragileandthinwalledparenchymaregions,

leaving thefibrous bundles in the coarserfractions. This could

betrackedmacroscopicallysincethe>2mmfractionhadaclear

Fig.1. Eucalypt(EucalyptusglobulusLabill.)bark.(a)Granulometricfractionwith >2mmparticles,observedunderthemagnifyingglass;(b)microscopicobservations ofdissociatedcellsobtainedfromthe1to2mmgranulometricfraction.

fibrousaspect(Fig.1a)whichwasfurtherobservedmicroscopically

byanalyzingthecelltypesafterdissociation(Fig.1b).

Birchbarkis markedlydifferentin structure. Itis composed

of twodistinct zones,thephloemandanimportant outerbark

(rhytidome)consistingofnumeroustightlypackedperidermsthat

includephellemlayersofthickandthin-walledcorkcells(Bhat,

1982).Thephloemhasagreatproportionofscelenchymaandthe

proportionofsclereidspredominatesoverthatoffibers.In

conse-quencethecoarserfractionofbirchdifferedmacroscopicallyfrom

thatofeucalyptbarkshowinganaspectofirregularlymoreorless

cubicparticlesofphloemandofflakesshapedparticlesfromthe

rhytidome(Fig.2a).Microscopically,aggregatesofsclerifiedcells

andofthephellemtissuecouldbeobserved(Fig.2b).

3.2. Bulkdensity

Table2givesthebulkdensityofthedifferentbark

granulomet-ricfractions.Bothbarksdifferedsignificantlyindensity,withmean

valuesof277kg/m3and169kg/m3forbirchandeucalypt,

respec-tively.Inthecaseofbirchbarkthereisacleartrendofincreasing

bulkdensitywiththedecreaseofparticledimensioninagreement

withtheoverallideathatsmallparticlesmaybebettercompacted

thanlargerparticles.

The eucalypt barkgranulates did not showa cleartrend of

Fig.2. Birch(BetulapendulaRoth.)bark.(a)Granulometricfractionwith>2mm particles,observedunderthemagnifyingglass;(b)microscopicobservationsof dissociatedcellsobtainedfromthe0.180to0.250mmgranulometricfraction.

betweenfractionsweresmaller.Theelongatedformoftheeucalypt

barkfractionsdoesnotallowaneasycompactionofparticles.

Verylittleinformation existsonbarkbulkdensity. Similarly

tothedifferencefoundhereforeucalyptandbirchbarks,abulk

densityof250kg/m3wasreportedfor0.120–0.50mmsizedbark

particlesofE.globulus(SarinandPant,2006).

Itisobviousthatbulkdensitiesofgranulatedbarksaremuch

lowerthanthecorrespondingparticledensity.Birchandeucalypt

barkshavebasicdensitiesranging,respectively,from452kg/m3to

559kg/m3(Bhat,1982;LambandMarden,1968),andfrom374to

454kg/m3(QuilhóandPereira,2001).Thisdifferencebetweenthe

Table2

Bulkdensity(kg/m3)forthedifferentgranulometricfractionsofthebirchand euca-lyptbarks.

Granulometricfraction,mm Bulkdensity,kg/m3

Birch Eucalypt <0.180 311.3 160.8 0.180–0.250 305.1 155.5 0.250–0.450 300.7 189.9 0.450–0.850 271.0 192.1 0.850–2.00 255.6 153.2 >2.00 239.0 181.2 Mean 276.9±28.9 169.4±18.5 Table3

Ashcontent(%oftotaldrymass)ofthedifferentgranulometricfractionsaftermilling ofbarks.

Granulometricfraction,mm Ash,%oftotaldrymass

Birch Eucalypt <0.180 3.4 23.1 0.180–0.250 4.5 14.7 0.250–0.450 2.5 15.9 0.450–0.850 2.6 7.9 0.850–2.00 2.1 6.7 >2.00 2.2 4.3 Mean 2.9±0.9 12.1±7.1

soliddensityofbothbarksisinaccordancewiththeir

correspond-ingstructuralfeatures,asdiscussedpreviously.

3.3. Ashcontentandcomposition

Theashcontentof thebirchand eucalyptbarksamples

col-lectedatthemillaftermillingand separationintothedifferent

granulometricfractionsisreportedinTable3.Thewholebiomass

ofbirchandeucalyptbarkshadanashcontentof2.9%and12.1%,

respectively,determinedasamassweighedaverageofallfractions.

ForB.pendulabark,Werkelinetal.(2005)reportedasimilarash

contentof3.8%andSaarelaetal.(2005)reportedvaluesbetween

1.0%and1.9%.Ashcontentforotherbirchspecieswasreportedas

1.7%forBetulaalleghaniensisand1.8%forBetulapapyrifera(Corder,

1976).

Thebirchbarkfractionsshowedhigherashcontentinthefiner

particles (4.5%in the 0.180–0.250mm fractionand 2.2%in the

>2mmfraction).Itisknownthatashtendstoaccumulateinthe

finersizedfractionduringbiomassprocessingduetothesmallsize

andbrittlenessofinorganicmaterial(Bridgemanetal.,2007;Liu

andBi,2011).Howevertheextentofmineralaccumulationinbark

fractionsdependsonthespecies(Mirandaetal.,2012).

TheashcontentofE.globulusbarkwasreportedas4.7%(Vázquez

etal.,2008)and4.5%(Akyuzetal.,2003)andintherangeof1.6–3.5% (Pereira, 1988b).Thepresent eucalyptbarksamplehada much

highermineralcontentwhichshowsthatthebarkobtainedinthe

millcontainedconsiderablecontaminationwithsoilparticlesand

otherextraneousfinematerial.Theamountofincrustatedsand

granuleswasnotoriousbyadirectmacroscopicobservationofthe

sample.Duetotheirsmallsize,theseparticleswereretainedin

thefinergranulometricfractionsafterthemillingandscreening.

AsshownbyTable3,thisoccurredespeciallyinthefinestparticles

(e.g.23.1%ashcontentinparticlessizebelow0.180mm)whilethe

largerdimensionparticlesshowedanashcontentsimilartothe

valuesreportedintheliteratureforeucalyptbark(4.3%in>2mm

particles).

Asimilaroccurrenceofsubstantialaccumulationofminerals

wasalsofoundforpinebarkobtainedatthemill(Mirandaetal.,

2012).Thisclearlyshowstheimportanceofbarkcleaningduring

fieldandmillhandlinginordertoavoidunsuitablecontaminations

duringsubsequentbarkvalorizationsteps.

The occasional problem of excessive sand and soil in the

eucalypt stem raw-material for thepulping industry is already

identified,dependingonthecaretakenbycontractorsduringfield

treeharvestingandhandlingsincethesoftandmoisteucalyptbark

allowseasyincrustationofthemineralparticles.

Twoofthebarkgranulometricfractions(0.250–0.450mmand

<0.180mm)werecharacterizedinrelationtomineralcomposition,

asshowninTable4.

Theconcentrationsofthemajorelementsweredifferentinboth

species.Birchbarkcontainedinrelationtoeucalyptbarkinthe

Table4

Elementalconcentrationsinbarksamplesofbirchandeucalyptdeterminedinthe 0.250–0.450mmand<0.180mmgranulometricfractions.

Birch Eucalypt 0.250–0.450mm <0.180mm 0.250–0.450mm <0.180mm N(%) 0.69 0.50 0.26 0.19 Ca(%) 0.393 0.303 0.623 0.181 Mg(%) 0.072 0.049 0.154 0.120 Na(%) 0.013 0.011 0.070 0.080 K(%) 0.242 0.169 0.308 0.230 P(%) 0.075 0.022 0.001 0.001 Cu(mg/1000g) 3.37 1.86 4.70 4.08 Zn(mg/1000g) 216.77 152.58 11.39 6.45 Ni(mg/1000g) 1.77 1.65 5.37 3.68 Cr(mg/1000g) 2.18 1.72 9.38 3.01 Pb(mg/1000g) 2.15 1.43 2.02 1.47

vs.0.001%),butlessCa(0.39%vs.0.62%),K(0.24%vs.0.31%)andMg

(0.07%vs.0.15%).

HighconcentrationofZnwasfoundintheashesofbirchbark

with217mg/kgincomparisonwith11mg/kgineucalyptbark.

Therewereonlysmalldifferencesinthemineralcomposition

ofboth fractions (Table 4)withtheexceptionof Ca

concentra-tionwhichdecreasedsubstantiallyinthefinestfractionofeucalypt

bark.

Thevaluesareintherangeofthosereportedforbirchbarks

byWerkelinetal.(2005),Saarelaetal.(2005)andReimannetal. (2007)andforeucalyptbarksbyPereira(1988b)andDamindaSilva etal.(1983).

3.4. Alkalineextraction

Alkalineextractionwith1%NaOH solubilized51.7% of birch

barkand43.3% ofeucalyptbark.Theseresultsarein therange

foundrecentlyforthealkalineextractionofspruceandpinebarks

(Mirandaetal.,2012)butarehigherthanthe1%NaOHextractives

reportedforE.globulusbarkbyVázquezetal.(2008)andbyPereira

(1988b),respectively,at26.6%and20.4–30.6%.HarkinandRowe (1971)alsoreportedforB.alleghaniensisand B.papyrifera28.4%

and25.1%,respectively.

Thehigheramountsofsubstancesremovedbyalkaline

lixivi-ationofbirchbarkincomparisontoeucalyptbarkareinrelation

withthepresenceofhigheramountsofextractivesandsuberinas

wellasofhemicelluloses.Suchcompoundsarepresentinhigher

contentsinthebirchbark,asdiscussedbelow.

3.5. Summativechemicalcomposition

Thebirchandeucalyptbarkswerechemicallycharacterizedand

thecompositioncalculatedasamassweighedaverageofall

gran-ulometricfractionsisshowninTable5.

Thereareconsiderabledifferencesbetweenbirchandeucalypt

barksinrelationtoextractives,suberinandholocellulosecontents.

Eucalyptbarkcontainslessextractivesthanbirchbarkbutmore

celluloseandhemicellulosesexpressedasholocellulose.

As regards the total extractives content, birch bark has

approximatelythree timesmore extractivesthaneucalypt bark

(respectively, 17.6% and 6.5%). Polar compounds extracted by

ethanol and water, which include especially phenolics and

polyphenolics,correspondedtoasignificantproportionofthetotal

content(60.8%inbirchand83.0%ineucalyptofthetotal

extrac-tives).Waxes and other non-polar compoundsthat are soluble

indichloromethane andmethanol makeuptheremaining bark

extractives,representing31.8%ofthetotalextractivesinbirchbark,

and16.9%ineucalyptbark.

Table5

Summativechemicalcomposition(%o.d.material)ofthebirchandeucalyptbarks, calculatedasmassweighedaverageofallgranulometricfractions.

Birch Eucalypt Ash 2.9 12.1 Extractives 17.6 6.5 Dichloromethane 5.1 0.9 Methanol 0.5 0.2 Ethanol 5.5 1.3 Water 5.2 4.1 Suberin 5.9 0.98a Lignin 27.9 34.1 Klason 26.4 26.6 Acidsoluble 1.5 7.5 Holocellulose 49.8 62.6

aSuberincontentdeterminedin40–60meshfraction.

Appreciabledifferencesarealsofoundinthecontentofsuberin.

Thebirchbarksamplecontainedaconsiderableamountofsuberin

(5.9%)whereastheeucalyptbarkcontainedaverysmallamount

(less than1%). Thisis in direct relationwiththedifferences in

theanatomicalstructureofbothbarks,i.e.withtheabsenceofa

rhytidomewithsuberizedphellemtissuesineucalyptbark.

Thebirchandeucalyptbarksamplesshowedsimilarcellwall

lignificationbuttherewasastrikingchemicaldifferencebetween

bothbarksinrelationtoholocellulosecontent:eucalyptbarkhad

muchhigherholocellulose(62.6%vs.49.8%).

Therearefewpublishedreferencesonthechemical

composi-tionofhardwoodbarks.ForthebirchbarksofB.alleghaniensisand

B.papyrifera,HarkinandRowe(1971)reported,respectively,total

extractives17.4%and22.4%,andlignin40.6%and37.8%.

ForE.globulusbark,Yadavetal.(2002)reported7.2%alcohol

extractives,15.5%waterextractives,28.0%ligninand62.2%total

carbohydrates.Vázquez etal. (2008) reported19.2% lignin and

Sakai (2001)18.6% lignin,43.2% cellulose and19.6% pentosans.

Pereira(1988b)referred6.3–8.5%extractives,16.7–21.1%Klason

lignin,48.2–54.9%celluloseand7.0–19.6%pentosans.

ThecarbohydratecompositionisgivenbyTable6inrelationto

theproportionofneutralmonosaccharides.Therearealso

consid-erabledifferencesbetweenbirchandeucalyptbarksespeciallyin

relationtoglucoseandxylosecontents.Glucoserepresented68.4%

and47.0%oftotalneutralmonosaccharides,respectively,in

euca-lyptandbirchbarksandxylose23.2%and33.8%,respectively.This

isclearlyindicativeofadifferentproportionofcelluloseand

hemi-cellulosesineucalyptandbirchbark.Takingroughlytheratioof

glucosetoxyloseasindicativeofcellulosetohemicelluloses,there

isastrikingdifference:2.96ineucalyptbarkand1.39inbirchbark.

Thechemicalcompositionofthexylansalsodiffersbetweenthe

species:theratioofarabinosetoxylosewas0.12ineucalyptbark

and0.31inbirchbark.

Vázquez et al. (2008)reported similarmonomeric

composi-tion ofpolysaccharides for E.globulusbark: a predominanceof

glucosewith70.4%andanimportantcontentofxyloseof20.8%

with3.6% ofgalactose,3.7% of arabinoseand 1.4% ofmannose.

Bargatto(2010)reportedalsothecarbohydratecompositionofE.

grandis×urophyllaandE.grandisbarks,respectively,forglucose

Table6

Carbohydratecompositionofthedifferentbarksin%oftotalneutral monosaccha-rides(40–60meshgranulometricfraction).

Monosaccharide Birch Eucalypt

Glucose 47.0 68.4 Mannose 4.1 1.9 Galactose 3.8 3.3 Rhamnose 1.1 0.4 Xylose 33.8 23.2 Arabinose 10.3 2.7

Table7

Chemicalcomposition(%oftotaldrymass)ofthedifferentgranulometricfractions aftermillingofbirchandeucalyptbarks.

Birchbark Eucalyptbark

F M C F M C Extractives 24.0 15.6 12.0 11.0 6.2 5.5 Dichloromethane 7.5 4.2 3.1 2.6 0.9 0.6 Methanol 0.5 0.5 0.2 0.4 0.3 0.2 Ethanol 8.8 5.1 4.3 1.9 1.2 1.1 Water 6.3 5.7 4.4 6.2 4.0 3.6 Suberin 7.3 6.0 7.2 – – – Lignin 27.1 28.5 27.1 29.0 29.2 22.1 Klason 26.0 27.2 25.1 26.6 26.1 18.9 Acidsoluble 1.1 1.4 2.0 2.4 3.1 3.1 Holocellulose 38.0 56.3 55.1 64.3 53.4 70.0 Granulometricfractions:fine(F,<0.180mm),medium(M,0.250–0.450mm)and coarse(C,>2mm).

76.4%and77.6%,xylose18.9%and16.9%,galactose1.8%and2.3%,

arabinose2.0%and2.2%,ramnose0.6%and0.7%.

HarkinandRowe(1971)reportedfor B.alleghaniensisandB.

papyrifera,respectively:glucose54%and53%,galactose3%and2%,

mannose1%,xylose32%and36%,arabinose8%and6%.

Itisinterestingalsotonoticethatthechemicaldifferencein

polysaccharidecompositionbetweentheB.pendulaandE.globulus

barksalsooccursinthecorrespondingwoods:xyloseandglucose

contents(%oftotal neutralmonosaccharides)represent,

respec-tively,32.6%,and61.4%inB.pendulawoodand20.0%and75.3%in

E.globuluswood(Pintoetal.,2005).

3.6. Effectofparticlesizeonbarkchemicalcomposition

Table7summarizestheresultsobtainedforthechemical

com-position of the fractions of <0.180mm (fine), 0.250–0.450mm

(medium)and >2mm(coarse)of themilledbirchand eucalypt

barks.

Aparticlesizeeffectwasobservedonthecontentand

compo-sitionofextractivesofbirchandeucalyptbark.Extractiveswere

presentpreferentiallyinthefinestfractionduetoenrichmentin

nonpolarandpolarcompounds.Theextractivescontentwas

high-estinthefine fraction, i.e.24.0% incomparison with12.0% for

thecoarserfractioninthecaseofbirchbarkand11.0%vs.5.5%

ineucalyptbark.Asregardscompositionofextractivestherewas

anenrichmentindichloromethaneandethanolsolublesinthefine

fractionespeciallyinthecaseofbirchbark.

Forthestructuralcomponents,theobserveddifferenceswere

eitherofsmallmagnitudeorwithoutaconsistentpatternof

varia-tionforbirchbark.Forinstance,suberincontentwassimilarinthe

threebirchbarkfractions.However,consideration ofthe

chem-icalcomposition basedonextractive-freematerial (ascouldbe

obtainedafterextractionofthebark)pointsoutthatsuberin

con-tentincreasesinthefinerfraction:respectively,9.6%,7.1%and8.1%

ofextractive-freematerialinthefine,mediumandcoarsefractions.

Ineucalyptbarkthelignincontentwashighestinthefine

frac-tion,i.e.29.0%incomparisonwith22.1%forthecoarserfraction

whileholocellulosecontentwashighestinthecoarsefraction.

Thedifferencesinthechemicalcompositionofthebarkfractions

areduetothedifferentanatomicaltissuesthatconditionthe

dis-tributionofsizesaftergrinding(Vázquezetal.,2001).Bridgeman

etal.(2007)reportedthatcellulose,hemicellulosesandlignintend

toremaininthelargerparticlesizedfraction.TamakiandMazza

(2010)andChundawatetal.(2007)alsoreportedcompositional

changeswithparticlesize:withincreasingparticlesizeextractives

contenttendtodecreaseandhemicellulosesandglucancontentto

increasewhilelignincontentdidnotshowcleartrends.

Theresultsshowedthatgrindingandfractionation by

parti-clesizeareunitoperationsthatmaybeusedtoselectiveenrich

fractionsinsolublematerials(thefinestfractions)forbothbarks.

Coarserfractionstendtohaveahigherholocellulosecontentand

willbethereforemoresuitableforcarbohydraterelateduses.

4. Conclusions

Structuralandanatomicalfeaturesareimportantcharacteristics

that influence bark processing, namely their grinding

behav-iorand particle fractioning.Accordingly thebarks of birchand

eucalyptshoweddifferentsizereductionpatternandparticle

char-acteristics.Thereforebiomasspre-treatmentssuchasmillingand

fractioninghavetobeadaptedtothespecificbiomasssource.

Birchandeucalyptbarkssubstantiallydifferedintheirchemical

composition,leadingtodifferentpotentialvalorizationroutes.

Birchbarkhasahighcontentofextractivesandanappreciable

amountofsuberinthatallowconsideringtheiruse.Fractionation

bysizeisadequateforaselectiveenrichmentinthesecomponents

inthefinerfractions.

Eucalyptbarkhasahighcontentofcelluloseandhemicelluloses

thatisenrichedinthecoarserfraction.Thefibrouscharacterofthis

fractionshowsitspotentialasafibersource.

Theresultsalsoshowedtheimportanceofacarefulfield

han-dling of stems in order to avoid excessive contamination with

minerals.

Acknowledgements

ThisworkwassupportedbytheEUresearchproject“AFORE

–Forestbiorefineries:Added-valuefromchemicalsandpolymers

bynewintegratedseparation,fractionationandupgrading

tech-nologies”underthe7thResearchFrameworkProgramme.Centro

deEstudosFlorestaisisaresearchunitsupportedbythenational

fundingofFCT–Fundac¸ãopara aCiência eaTecnologia

(PEst-OE/AGR/UI0239/2011).

References

Akyuz,M.,Sahin,A.,Alma,A.,Bektap,I.,Usta,A.,2003.Conversionoftreebark intobakelite-likethermosettingmaterialsbyphenolation.In:XIIWorldForest Congress,QuébecCity,Canada,September30.

Bargatto,J.,2010.Avaliac¸ãodopotencialdacascadeEucalyptusspp.paraaproduc¸ão debioethanol.Ph.D.Dissertation.UniversidadedeS.Paulo,EscolaSuperiorde AgriculturaLuizdeQueirós,Piracicaba,Brazil.

Bhat,K.M.,1982.Anatomy,basicdensityandshrinkageofbirchbark.IAWABulletin 3(3–4),207–213.

Bridgeman,T.G.,Darvell,L.I.,Jones,J.M.,Williams,P.T.,Fahmi,R.,Bridgwater,A.V., Barraclough,T.,Shield,I.,Yates,N.,Thai,S.C.,Donnison,I.S.,2007.Influenceof particlesizeontheanalyticalandchemicalpropertiesoftwoenergycrops.Fuel 86,60–72.

CEPI,2010.KeyStatistics2010.EuropeanPulpandPaperIndustry.

Chundawat,S.P.S.,Venkatesh,B.,Dale,B.E.,2007.Effectofparticlesizebased sepa-rationofmilledcornstoveronAFEXpretreatmentandenzymaticdigestibility. BiotechnologyandBioengineering96(2),219–231.

Corder,S.E.,1976.Propertiesandusesofbarkasanenergysource.ResearchPaper 31,ForestResearchLaboratory,OregonStateUniversity,Corvallis.

DamindaSilva,H.,Poggiani,F.,Coelho,L.C.,1983.Biomass,nutrientcontentand concentrationinfiveEucalyptusspeciescultivatedonlowsoilfertility.Boletim dePesquisaFlorestal,Colombo6/7,9–25.

Demirbas,A.,2010.BiorefineriesforBiomassUpgradingFacilities(GreenEnergyand Technology).Springer-Verlag,London.

Fengel,D.,Wegener,G.,1984.Wood:Chemistry,Ultraestructure,Reactions.Walter deGruyter,Berlin.

Harkin,J.M.,Rowe,J.W.,1971.Barkanditspossibleuses.ResearchNoteFPL,091.U.S. DepartmentofAgriculture.ForestService.ForestProductsLaboratory,Madison, Wisconsin.

Jackson,M.L.,1958.SoilChemicalAnalysis.Prentice-Hall,Inc.,Madison,Wisconsin. Jensen,W.,1948.Omytskiktsavfalletvidframställningavbörkfaner(Aboutthe sur-facelayerwastefromproductionofbirchveneer).Ph.D.Thesis.ActaAcad. Aboensis,Math.Phys.XVI,3.

Lamb,F.M.,Marden,R.M.,1968.BarkspecificgravitiesofselectedMinnesotatree species.ForestProductsJournal18(9),76–82.

Liu,X.,Bi,X.T.,2011.Removalofinorganicconstituentsfrompinebarksand switch-grass.FuelProcessingTechnology92(7),1273–1279.

Marti,F.,Mu ˜noz,J.,1957.FlamePhotometry.ElsevierPublishing,London. Miranda,I.,Gominho,J.,Mirra,I.,Pereira,H.,2012.Chemicalcharacterizationofbarks

fromPiceaabiesandPinussylvestrisafterfractioningintodifferentparticlesizes. IndustrialCropsandProducts36,395–400.

Patt,R.,Kordsachia,O.,Fehr,J.,2006.EuropeanhardwoodsversusEucalyptusglobulus asarawmaterialforpulping.WaterScienceandTechnology40,39–48. Pereira,H.,1988a.ChemicalcompositionandvariabilityofcorkformQuercussuber

L.WaterScienceandTechnology22,211–218.

Pereira,H.,1988b.Variabilityinthechemicalcompositionofplantationeucalypts (EucalyptusglobulusLabill.).WoodandFiberScience20(1),82–90.

Pereira,H.,Grac¸a,J.,Rodrigues,J.C.,2003.Woodchemistryinrelationtoquality.In: Barnett,J.R.,Jeronimidis,G.(Eds.),WoodQualityanditsBiologicalBasis.CRC Press,BlackwellPublishing,Oxford,pp.53–83.

Pereira,H.,Miranda,I.,Gominho,J.,Tavares,F.,Quilhó,T.,Grac¸a,J.,Rodrigues,J., Shatalov,A.,Knapic,S.,2010.In:CentrodeEstudosFlorestais(Ed.),Qualidade TecnológicadoEucaliptoEucalyptusglobulus.InstitutoSuperiordeAgronomia, UniversidadeTécnicadeLisboa,Lisboa.

Pinto,P.C.,Evtuguin, D.V.,PascoalNeto,C.,2005.Structureof hardwood glu-curonoxylans:modificationsandimpactonpulpretentionduringwoodkraft pulping.CarbohydratePolymers60,489–497.

Quilhó,T.,Pereira,H.,Richter,H.G.,1999.Variabilityofbarkstruturein plantation-grownEucalyptusglobulus.IAWAJournal20(2),171–180.

Quilhó,T.,Pereira,H.,Richter,H.G.,2000.Within-treevariationinphloemcell dimensionsandproportionsinEucalyptusglobulus.IAWAJournal21(1),31–40. Quilhó,T.,Pereira,H.,2001.Withinandbetween-treevariationofbarkcontentand wooddensityofEucalyptusglobulusincommercialplantations.IAWAJournal 22(3),255–265.

Reimann,C.,Arnoldussen,A.,Finne,T.E.,Koller,F.,Nordgulen,Ø.,Englmaier,P., 2007.Elementcontentsinmountainbirchleaves,barkandwoodunderdifferent anthropogenicandgeogenicconditions.AppliedGeochemistry22,1549–1566. Repola,J.,2008.BiomassequationsforbirchinFinland.SilvaFennica42(4),605–624. Rowell,R.M.,2005.HandbookofWoodChemistryandWoodComposites.CRCPress,

Madison,USA.

Saarela,K.-E.,Harju,L.,Lill,J.-O.,Heselius,S.-J.,Rajander,J.,Lindroos,A.,2005. Quan-titativeelementalanalysisofdry-ashedbarkandwoodsamplesofbirch,spruce andpinefromsouth-westernFinlandusingPIXE.ActaAcademiaeAboensis, SeriesB65(4),1–27.

Sakai,K.,2001.Chemistryofbark.In:Hon,D.N.-S.,Shiraishi,N.(Eds.),Woodand CellulosicChemistry.,2nded.MarcelDekker,NewYork.

Sarin,V.,Pant,K.K.,2006.Removalofchromiumfromindustrialwastebyusing eucalyptusbark.BioresourceTechnology97,15–20.

Sen,A.,Miranda,I.,Santos,S.,Grac¸a,J.,Pereira,H.,2010.Thechemicalcomposition ofcorkandphloemintherhytidomeofQuercuscerrisbark.IndustrialCropsand Products31,417–422.

Silva,G.G.D.,Guilbert,S.,Rouau,X.,2011.Successivecentrifugalgrindingandsieving ofwheatstraw.PowderTechnology208,266–270.

Tamaki,Y.,Mazza,G.,2010.Measurementofstructuralcarbohydrates,lignins,and micro-componentsofstrawandshives:effectsofextractives,particlesizeand cropspecies.IndustrialCropsandProducts31,534–541.

Trockenbrodt,M.,1991.Qualitativestructuralchangesduringbarkdevelopmentin Quercusrobur,Ulmusglabra,PopulustremulaandBetulapendula.IAWABulletin 12(1),5–22.

Vázquez,G.,Parajó,J.C.,Antorrena,G.,1987.Sugarsfrompinebarkbyenzymatic hydrolysis.Effectofsodiumchloritetreatments.WaterScienceandTechnology 21,167–178.

Vázquez,G.,González-Alvarez,J.,Freire,S.,López-Suevos,F.,Antorrena,G.,2001. CharacteristicsofPinuspinasterbarkextractsobtainedundervariousextraction conditions.HolzalsRohundWerkstoff59,451–456.

Vázquez,G.,Fontenla,E.,Santos,J.,Freire,M.S.,González-Álvarez,J.,Antorrena,G., 2008.Antioxidantactivityandphenoliccontentofchestnut(Castaneasativa) shellandeucalyptus(Eucalyptusglobulus)barkextracts.IndustrialCropsand Products28,279–285.

Werkelin,J.,Skrifvars,B-J.,Hupa,M.,2005.Ash-formingelementsinfour Scan-dinavianwoodspecies.Part1:Summerharvest.Biomass&Bioenergy 29, 451–466.

Yadav,K.R.,Sharma,R.K.,Kothari,R.M.,2002.Bioconversionofeucalyptusbark wasteintosoilconditioner.BioresourceTechnology81,163–165(Short com-munication).