„Revista română de sociologie”, serie nouă, anul XXVII, nr. 1–2, p. 111–124, Bucureşti, 2016

Creative Commons License Attribution-NoDerivs CC BY-ND

THE TRADITION OF MAY DEVOTIONS TO THE VIRGIN MARY

IN LATGALE (LATVIA):

FROM THE PAST TO THE PRESENT

AIGARS LIELB RDIS*

ABSTRACT

An important role has been allocated to the Virgin Mary since the very beginnings of Christianity. According to the calendar of the Roman Catholic Church, May is dedicated to honouring the Virgin Mary. Due to her human origins, she has become an intermediary between people and God, capable of influencing the decisions of her son Jesus Christ, and providing assistance to people of her own accord. Together with God and Jesus Christ, she is considered to have extraordinary, saintly qualities in Latvian Catholic communities.

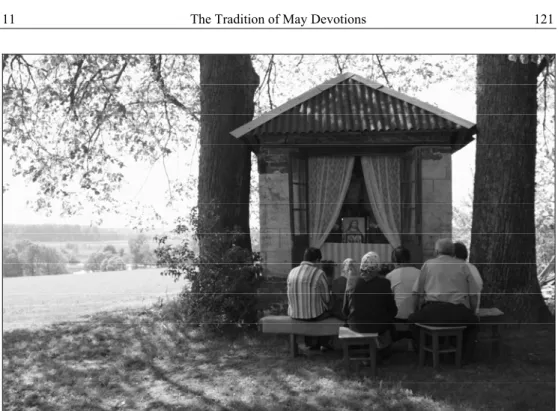

At the beginning of the 19th century, the tradition of May devotions began to spread widely in Catholic territories in Latvia. Currently the services are usually performed by womenfolk in the rural environment. Every evening or on weekends in May, people gather to pray and sing in churches, cemeteries, at crossroads, or in the centre or the edge of villages where crucifixes are located.

Keywords: May Devotions, Virgin Mary, Latgale, Catholicism, Jesuits, crucifixes.

INTRODUCTION

According to the Calendar of the Roman Catholic Church, May is dedicated to the honouring of the Virgin Mary. The tradition of May devotions in the present form – honouring the Virgin Mary over the entire month of May – can be traced back to the late 18th century in Rome, where Father Latomia of the Roman College of the Society of Jesus made a vow to devote the month of May to Mary to counteract infidelity and immorality among students. The practice spread from Rome to Jesuit Colleges and thence to nearly every Catholic Church adhering to

*

the Latin rite. (Golweck, 1911: 542) This vow had been carried out in practice in many Catholic territories in Eastern Europe as well, through the Jesuits’ colleges, schools and rural missions. Using current geographical terms this would be in Lithuania, Poland, Belorussia, Russia, and Latvia. Nevertheless this tradition did not establish roots in every place due to varying historical circumstances.

The tradition of May devotions is still widespread in Latvia today. For Catholic communities, which are located mostly in Latgale (the eastern part of Latvia) and in isolated places in Augšzeme (the south-eastern part of Latvia) and Kurzeme (the western part), May is a time when prayers and songs are devoted to the Virgin Mary. Every evening or on weekends, mainly in the rural environment, womenfolk gather to venerate the Virgin Mary in churches, in the villages, at crossroads and at cemeteries where wooden crucifixes are located.

This publication contains an analysis of the tradition of May devotions, emphasizing the historical background, the development and an explication of the tradition nowadays. The study is based on historical sources, scientific publications and fieldwork materials.

ROOTS, SOIL, AND JESUITS

From the second half of the 16th century, after the Council of Trent (1545– 1563), there was an active period of Counter-Reformation and Re-Catholicisation in Europe. It was a time rich in pilgrimages, miraculous experiences, and the missions of different orders, especially of the Jesuits. In some regions, for example, in Eastern Europe, the activities of Catholics continued at a high intensity until the 19th century.

contribution to the consolidation of the vernacular or home religion in Europe, which was usually intermingled with experience from the local religion and prior practices. Trevor Johnson writing about the popular religion in Germany and Central Europe in 1400–1800 noticed that through sacraments, Jesuits taped into a vast reservoir of popular religious culture. Prayers, charms, conjurations, blessings and exorcisms were a vital ingredient of popular techniques of protection against disease, disaster and sorcery. (Johnson, 1996: 198)

After the Livonian War (1558–1583), the current territory of Latvia was divided into Catholic and Lutheran lands. In 1582, Polish King, Stephen Bathory arrived in Livonia with the Jesuits Piotr Skarga, Martin Laterna and Jan Vincery. (Kleijntjenss, 1941: VII) In 1583, the first Jesuit school in Riga was established and the Bishopric in Cēsis was founded. After that, Jesuit mission centres in Riga and in the current central part of Latvia were opened. (Kleijntjenss, 1941: XI) Jesuit Antonio Possevino, who was an adviser to King Stefan Bathory resided in Riga at this time as well. In the following centuries, Livonia became an area of Jesuit pastoral, economic and political activities and influence. The interchange of personnel from the Jesuit Order between other European countries ensured the circulation and transfer of spiritual practices from other Jesuit mission points and schools.

After the Polish-Swedish War (1600–1629), Latgale (called Inflanty or Polish Livonia) was separated from the other Latvian regions. The western and central part of Latvia came under the rule of the Kingdom of Sweden, whereas the eastern part remained in the Catholic Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In 1621, the Jesuits were expelled from Riga (this had happened before, in 1587), but they periodically returned to the city despite the prohibitions. (Kleijntjenss, 1941: XXIII) In 1625, the residence in Cēsis was closed and the Jesuits were expelled from the central part of Latvia by the Swedish authorities. (Kleijntjenss, 1941: 283) The Jesuits moved to other missions in the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia (the southern part of today’s Latvia) and to Polish Livonia where the mission of Dinaburg (today Daugavpils) had existed since 1630. (Kleijntjenss, 1940: 243–260)

in the territory of Tsarist Russia. Hence, many Jesuits from other European countries, in which their activities had been banned, migrated to the territories which today are Latvia, Lithuania, Belorussia, and Russia. Their brought with them their experience and religious beliefs and ritual practices, which they attempted to cultivate in the new territories. One of these practices was the May devotions to Mary, which soon found a place in Catholic Latvia.

In 1814, Pius VII re-established the Jesuit Order (Oxford Dictionary, 1998: 1924.), but in 1820 Jesuits were expelled from the Russian territories, because of the Tsar’s decision to sustain the position of Orthodoxy and to further the Russification of non-Russian speaking nations. It is thought that the late 18th century and the first quarter of the 19th century was the time when the tradition of May devotions commenced in the Latvian Catholic community. After the banishment of the Jesuits, the new practice was continued by the people without the direct involvement and physical presence of the Jesuits. In future years the Jesuits sustained Catholic traditions by publishing books, which were sent into the territory of Latgale. In the circumstances of Russification and the oppression of Catholicism, the tradition of May devotions also gradually gained the character of resistanc

e.

CATHOLICISM, CRUCIFIXES AND THE VIRGIN MARY

From the end of the 12th century, the current territory of Latvia came under the influence of Catholicism by degrees. In the 13th century, the territory of today’s Latvia and Estonia formed the Confederation of Livonian countries, which at the beginning was a union of Catholic lands. St. Mary became the patron of Catholic Livonia and gradually entered the people’s religion, traditions and their everyday lives. (Lielb rdis, 2015: 94–95)

Catholic saints (e.g. the Virgin Mary, St. Anna, Jesus Christ, St. Anthony), continued to exist. Moreover, most of the significant festival days were named after Catholic saints. The spring and the autumn markets, for instance, which were very popular, retained saints as patrons.

In contrast to the previously mentioned territories of Vidzeme and Kurzeme, Catholicism has endured in Latgale throughout nearly all of the period from the 12th century until today, even though in the first centuries this was purely a formality. In Latgale, Catholicism became not just the primary religion, but it also had a significant role in the development of the national identity. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, when national consciousness had awakened in Latvian society, the inhabitants of Latgale often called themselves Catholics, i.e. substituting their national identity with membership in a religious confession. (Adamovičs, 1934–1935: 21610; Br vzemnieks, 1991: 93) This kind of positioning of themselves by the people of Latgale was made possible by the fact that until the founding of Latvia as a state in 1918, Latgale had been separated from the other territory of Latvia since the early 17th century. Catholicism was one of the most significant factors forming Latgale’s cultural and societal singularity and sense of being different.

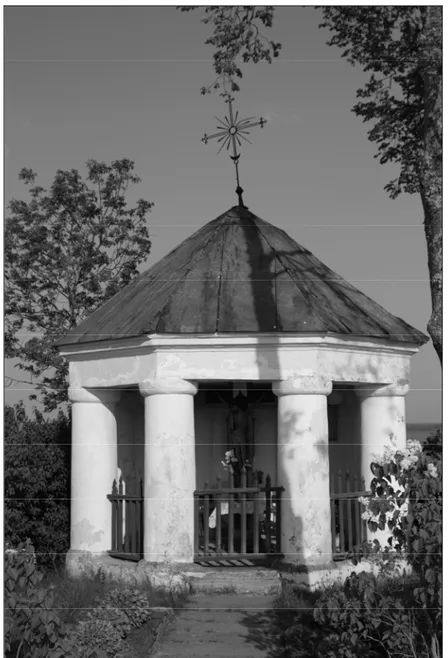

Some of the visual evidence, which indicates regional differences and can still be noticed today, is the presence of crucifixes in the Latgale landscape. The origins of crucifixes in Latvia, like elsewhere in Europe, are connected with the spread of Catholicism, especially with Jesuit missions in towns, villages and isolated hamlets. Luis Chatellier noted that the most novel and essential thing that the missionaries brought was the cross in the most literary sense of the word. From the end of the 17th century, the ceremony of planting a cross assumed increasing importance in the procedure of a mission. (Chatellier, 1997: 108) The crucifix was planted at the end of the mission, which usually lasted from 7–9 days, but could also be longer. The cross, which on average was 2.5 metres high, marked the particular territories and people’s belonging to Catholicism. In Latgale, crosses can be found in the centre or at the outskirts of villages. They are often located along the main road or at crossroads, giving travellers a place to stop, rest and spend some time in prayer.

Figure no. 1 – A cross shelter made of wood, Sakstagals neighbourhood, 2014.

Photo: Aigars Lielbārdis.

BOOKS, TRADITION AND PERFORMANCE

It is thought that the tradition of May devotions began in Latgale at the turn of the 18th–19th centuries. The commencement of the tradition, like elsewhere in Europe, was connected with the Jesuits who were active in the territory of Latgale until 1820. The Jesuits introduced and spread the tradition, but after they were banished from the Russian Empire, monks from other orders and priests continued the devotions. The ritual reached its height in the mid-19th century when guidelines and descriptions for the performance of the tradition were published in prayer and song books, as well as in separate publications. Prior to the early 20th century, the tradition, like other Catholic religious activities, was restricted in Tsarist Russia and conducted semi-secretly. It is considered that the tradition was most widely and openly practiced after the nation gained its independence and until World War II, i.e. the 1920s to 1940s. In most cases the May devotions continue to take place without the presence of a priest, which makes this a folk tradition, a folk religious practice, which has been passed down through the generations until today.

The banning of the Jesuits’ activities in the Russian Empire, including Latgale, was one of the first and most significant steps for reducing the influence of Catholicism and to weaken its positions in the regions traditionally considered to be Catholic. The influence and the power of the Jesuits were known from their achievements elsewhere in Europe. Missionaries methodically traversed entire regions, from the big cities to the smallest villages, reaching everyone individually. Such missionary activity had not been seen since the early centuries of Christianity. (Chatellier, 1997: 85) In addition, the Jesuits published Church literature in the Latgalian orthography, founded and ran schools as well as missions and used a dialect of the local language in their communication with the community. This also strengthened the community’s confidence and may have created the desire for self-determination, which was not expedient for the government of the Tsarist nation.

Books of a religious nature helped people learn to read in their native language, but in Latgale there was a restriction on printing from 1864–1904, which banned the issue of books in Latin letters in the Latgalian orthography. The use of the national language was also restricted in schools and the state administration, especially starting from the 1880s. In this way, religious activities in Latgale served not only in strengthening identity and language, but also manifested themselves as resistance to the existing governmental system. During the printing ban, books with Latin letters were published outside the Russian Empire, for example in Konigsberg, and were brought in as contraband. The publication dates on the title pages of books published during the printing ban, were shown as being before the printing ban and the place of publication was also shown as being elsewhere.

and God] (Pilniejga gromata, 1857), which was republished many times. The place of issue was shown in this book as Vilnius, while the date of publication as 1857. This bypassed the censor, allowing users of the book to avoid confiscation.

The first known description of the May devotions in the Latgalian orthography was published in 1843, in a separate publication named Gromatynia kolposzonas Jumpraway Maryay por maja mienesi [Book of Worship of the Virgin Mary in May]. (Gromatynia, 1843) The publication included lessons and sequential instruction for those practicing the tradition of May devotions:

“Anyone who wishes to worship the Virgin Mary during that month [May], should do so. On the evening before the first day of May [i.e. 30 April] the gathered should recite the Rosary or the Litany, or 7 prayers to the Virgin Mary. After this, one person should hold 12 notes or leaflets [znaczkenia] from the first chapter in their hands, each should take one: each note will announce the type of worship which should be done all month”. (Gromatynia, 1843: 4) The notes will show the kinds of prayer which must be said all month (2nd and 4th note), that one must get up from sleep without tarrying (1st note), avoid telling lies (7th note), avoid gossiping (9th note), not to eat breakfast or lunch on Saturdays (10th note), that one must go to church every Sunday and must recite Ave Maria 7 times next to the icon of Mary and kiss the ground 7 times, etc. (Gromatynia, 1843: 5–7) There are 12 notes in total.

This is followed by teachings for each day, which must be done during the month of May: “Each day, one note must be taken from the second chapter. The note will reveal how one must worship the Virgin Mary throughout the day”. (Gromatynia, 1843: 4) The book contains a section to be read for each day or teachings about some miracle in the life of the Virgin Mary, which is to be followed by prayers. This should be done if there is time, and if one can’t fulfil what has been set on some day and it is omitted, then this is not a sin. (Gromatynia, 1843: 5) In the notes that are to be performed each day – prayers at various times, the Ave Maria and Pater Noster (1st, 2nd and 3rd note), which must be recited lying in the shape of a cross (8th note), one must be on one’s guard not to unnecessarily mention God’s name (4th note), and not to stare in the direction that one really wishes to all day (10th note). (Gromatynia, 1843: 7–8) There are 12 notes in total as well.

God” (Pilniejga gromata, 1857: 618–659) which was the most widely spread 19th century prayer and song book, and was an important precondition for introducing the tradition into the wider community, and so that the practice of the tradition would be similar in different places.

Concepts about religion and deities were created through these short stories, telling of the presence of God, the Devil, Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary in people’s everyday lives. An understanding of deities was developed in vernacular religion through a simplified Catholicism. Even though religious activities adhered to by the populace often differed in both form as well as understanding from official church practice, the final result was that knowledge about the content of Christianity in society was kindled. The May devotions can be counted among the traditions of home religion too, as they were mainly performed without the presence of an official church representative, and continue in the same way today.

In the Soviet period, until the 1980s, religious activities were combatted, banned and the state repressed ordinary people and priests. In the first years of the Soviet era, religious conviction and activities were often adequate reasons for a person to be jailed or deported to Siberia, thus Catholic traditions were practiced secretly. To reduce the influence and presence of religion in the Soviet period, many village crucifixes were destroyed, while cultural centres, crash repair workshops and warehouses were set up in churches. The situation changed in the 1980s, and with the regaining of an independent state in 1991, religious confessions also gained “freedom”.

Figure no. 3 – May devotions performance at Makuži, 2014. Photo: Aigars Lielbārdis.

CONCLUSION

Granted the fact that the tradition of May devotions only began in the late 18th century in Rome, and presume that the tradition was already known in Eastern Europe at the turn of the 18th–19th centuries, then only 20 years were needed to bring the tradition to life in the territory of Latgale. But this time was sufficient if one takes into account the Jesuit Order’s discipline, methodology and the perseverance of the monks in maintaining the Catholic tradition. (Wright, 2004: 56) In addition, in the late 18th century after the discontinuation of the Jesuit Order’s activities elsewhere in Europe, many of them arrived in the territory of the Russian Empire, including Latgale. In this way the Jesuits gained additional personnel for their work in the missions and schools. After 1820, when the Jesuits were driven from the Russian Empire, the tradition of May devotions which they had started was continued by monks and priests from other orders and, most importantly – by the common folk without the presence of church representatives.

One of the reasons for the popularity of the Jesuits was the fact that they attempted to involve the community in religious activities – pilgrimages and open air theatricals. The tradition of May devotions is also an example – prayers are recited together, songs are sung, notes are drawn out, a practice which is looked at with humour today. The reason for the merriment could be, for example, if one were to draw a note which forbade them from imbibing strong alcoholic drinks for the entire month of May (6th note). In this way the tradition offers a religious experience, musical pleasure, and the community is brought closer together through the time spent together.

The presence of crucifixes in the cultural and natural landscape of Latgale and Augšzeme is a centuries old legacy of the Jesuits. Initially the crucifixes were mounted to mark a place and community, denoting that it adhered to Catholicism, but later they became places of prayer and gathering. Like elsewhere in Europe, there was a diversity of crucifixes and this diversity continues to exist in Latgale, in terms of form, materials, placement and artistic execution, though all are united by similar functions. The crucifixes are “used” mainly in the month of May when the people come together in the evenings in smaller or larger groups and perform the May devotions.

The designation “Catholic” during the 19th century in Latgalian society, included not just belonging to a different religion, but also one’s national identity. In turn, the Latvian language form or High Latvian dialect spoken in Latgale made them different from the rest of Latvian society.

The image of the Virgin Mary also helped the tradition to take root. From the beginnings of Catholicism, it had taken a more and more significant role in the culture of Latvia, replacing, intertwining and taking over the functions of Laima, the deity of the Latvian pre-Christian religion. In addition – the image of the Virgin Mary continued a tradition from the Middle Ages in the religious concepts of the mid-19th century – that deities are present in the daily lives of the community, take part in solving everyday problems, at times becoming angry, jealous, offended or very happy. Deities had human features and weaknesses. The barrier between reality and religious experience was broken down through the legends and stories of various sacred miracles. The simplification of the images of various saints and deities can be linked with the minds of people at the time. Their understanding of the connectivity of things, which was maintained in this kind of model in later centuries, created and strengthened the home religion, which continued to distance itself even more from the official practices and position of the church.

Economic conditions and migration have contributed to the gradual disappearance of the tradition of May devotions from its traditional rural environment, as fewer and fewer people participate in the sessions and the younger generation take part more and more rarely. The tradition is also declining because its performance requires musical skill, knowledge and experience, which have not always been passed on to the younger generation. But, official church events, without necessarily meaning to, also contribute to the decline in the performance of the tradition in the open air next to crucifixes. May devotions are broadcast on the radio throughout the month of May. As a result, those people who practice this tradition no longer travel to the crucifixes, but sit next to the radio at home instead and worship the Virgin Mary in this way. This means that the tradition is in flux and is gaining a new form of existence, and therefore – it is alive.

REFERENCES

1. ADAMOVIČS, LUDVIGS (1934–1935). “Latvju bazn cas vesture” [History of Latvian Church]. In Šv be, A.; Būmanis, K. and Dišlērs, K. (eds.), Latviešu konversācijas vārdnīca [Latvian Conversation Lexicon], vol. XI, R ga: A. Gulbja apg ds, col. 21519–21611.

2. ADAMOVIČS, LUDVIGS (1933). Vidzemes baznīca un latviešu zemnieks (1710-1740) [Church and Latvian peasant in Livland (1710–1740)], R ga: Ģener lkomisija Latvijas Vidusskolu Skolot ju Kooperat v .

3. BR VZEMNIEKS, FRICIS (1991). Autobiogrāfiskas skices [Autobiographic Sketches], R ga: Liesma. 4. CHATELLIER, LOUIS (1997). The Religion of the poor. Rural missions in Europe and the

5. GOLWECK, FREDERICK G. (1911). “Months”. In The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. XI, New York: Robert Appleton Company, p. 542–543.

6. Gromatynia (1843). Gromatynia kolposzonas Jumpraway Maryay por maja mienesi [Book of Worship of the Virgin Mary in May], Wilna: Izdrukawota uz Kolna Pestieytoja.

7. JOHNSON, TREVOR (1996). “Blood, Tears and Xavier-Water: Jesuit Missionaries and Popular religion in the Eighteenth-century Upper”. In Johnson, T. and Scribner, B. (eds.), Popular Religion in Germany and Central Europe, 1400–1800, New York: St. Martin’s Press, p. 183–202. 8. KLEIJNTJENSS, JANS (eds.) (1941). Latvijas vēstures avoti jezuitu ordeņa archivos [Sources of Latvian History in Archives of Jesuit Order.], part II, series: Latvijas vēstures avoti [Sources of Latvian History], vol. 3, R ga: Apg ds Latvju Gr mata.

9. KLEIJNTJENSS, JANS (eds.) (1940). Latvijas vēstures avoti jezuitu ordeņa archivos [Sources of Latvian History in Archives of Jesuit Order.], part I, series: Latvijas vēstures avoti [Sources of Latvian History], vol. 3, R ga: Latvijas Vēstures institūta apg diens.

10. LIELB RDIS, AIGARS (2015). “Catholic Saints in the Latvian Calendar”. In Minniyakhmetova, T. and Velkoborska, K. (eds.), The Ritual Year 10. Magic in Rituals and Rituals in Magic, Innsbruck, Tartu: ELM Scholary Press, p. 91–99.

11. Oxford Dictionary (1998). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, New York: Oxford University Press.

12. Pilniejga gromata (1857). Pilniejga gromata łyugszonu uz guda Diwa Kunga ikszan Tryjadibas winiga, Wyssu swatokas Jumprawas Maryas un Diwa swatu [Complete Prayer Book in Honour of the Trinity, the Blessed Mary and God], Wilna: Noma taysieszonas gromotu A. Dworca.

13. POLLEN, JOHN H. (1912). “Society of Jesus”. In: The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. XIV, New York: Robert Appleton Company, p. 81–110.

14. POWER, EILEEN (2011). “Introduction”. In: Herolt, Johannes, Miracles Of The Blessed Virgin Mary, Seattle, Washington: Create Space Independent Publishing Platform, A Division of Amazon, p. I–XXVII.