UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA

“JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO”

FACULDADE DE MEDICINA VETERINÁRIACÂMPUS ARAÇATUBA

AVALIAÇÃO MITOCONDRIAL EM CÉLULAS

MONONUCLEARES PERIFÉRICAS CANINAS

INFECTADAS COM O VÍRUS DA CINOMOSE

Sabrina Donatoni Agostinho

Médica VeterináriaAraçatuba – SP

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA

“JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO”

FACULDADE DE MEDICINA VETERINÁRIACÂMPUS ARAÇATUBA

AVALIAÇÃO MITOCONDRIAL EM CÉLULAS

MONONUCLEARES PERIFÉRICAS CANINAS

INFECTADAS COM O VÍRUS DA CINOMOSE

Sabrina Donatoni Agostinho

Orientadora: Prof

a. Adj.Tereza Cristina Cardoso Silva

Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária – Unesp, Campus de

Araçatuba, como parte das exigências para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ciência Animal (Medicina Veterinária Preventiva).

Araçatuba – SP

Catalogação na Publicação (CIP)

Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação – FMVA/UNESP

Agostinho, Sabrina Donatoni

A275a Avaliação mitocondrial em células mononucleares periféricas caninas

infectadas com o vírus da cinomose / Sabrina Donatoni Agostinho.

Araçatuba: [s.n], 2013

51f. il.; + CD-ROM

Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Estadual Paulista,

Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária, 2013

Orientadora: Profa Adj. Tereza Cristina Cardoso Silva

1. Virus da cinomose canina 2. Estresse oxidativo3. Mitocôndrias 4. Morbillivirus 5. Imunossupressão

DADOS CURRICULARES DA AUTORA

SABRINA DONATONI AGOSTINHO – nascida em 18 de novembro de 1986,

na cidade de Araçatuba, com graduação em Medicina Veterinária pela

Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho” (UNESP) – Araçatuba – SP, em 2010. Realizou Estágio de Iniciação Científica durante a graduação e

“Em vez de amor, dinheiro, fé, fama, equidade, dê

-me a

verdade.”

AGRADECIMENTOS

Agradeço à minha orientadora Profa. Adj. Tereza Cristina Cardoso Silva pelas oportunidades oferecidas, pelo conteúdo compartilhado ao longo destes anos e pelo exemplo como pesquisadora.

À Profa. Dra. Sílvia Helena Venturoli Perri pela disponibilidade e atenção oferecida para a análise estatística dos resultados deste projeto.

À Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária de Araçatuba – UNESP, pela oportunidade de realização do Mestrado.

À Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) pelo apoio financeiro a este projeto.

Ao companheiro de pesquisa Flávio T. L. B. Roncatti pelas experiências compartilhadas ao longo destes anos.

A toda equipe do Laboratório de Virologia Animal, da Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária de Araçatuba – UNESP, pelo trabalho e dedicação oferecidos desde a época de minha graduação até a finalização do mestrado.

TRABALHO REALIZADO NO LABORATÓRIO DE VIROLOGIA

ANIMAL, FACULDADE DE MEDICINA VETERINÁRIA, CAMPUS

DE ARAÇATUBA COM O APOIO DA FUNDAÇÃO DE AMPARO À

PESQUISA DO ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO (2010/12721-6 e

SUMÁRIO

1. CONSIDERAÇÕES GERAIS 13

1.1. Aspectos gerais 13

1.2. Mediadores da morte celular programada 16 1.3. Mitocôndria e estresse oxidativo 20

2. OBJETIVO GERAL 25

2.1. Objetivos específicos 25

3. CONCLUSÕES 26

4. REFERÊNCIAS 27

5. ARTIGO CIENTÍFICO 34

5.1. ABSTRACT 35

5.2. INTRODUCTION 36

5.3. MATERIAL AND METHODS 37

5.4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 40

AVALIAÇÃO MITOCONDRIAL EM CÉLULAS MONONUCLEARES PERIFÉRICAS CANINAS INFECTADAS COM O VÍRUS DA CINOMOSE

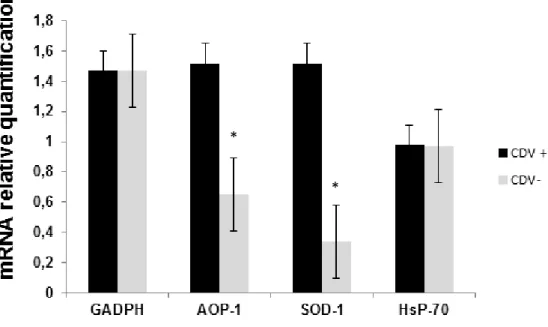

RESUMO - A disfunção mitocondrial está associada com a manifestação e com a origem de doenças e distúrbios metabólitos. Um novo paradigma complementa um dogma recente relacionado com esta função, onde moléculas presentes no meio extra ou intra-mitocondrial podem atuar como reguladores da resposta imunológica nata, decorrente de um estresse e/ou de uma infecção. O vírus da cinomose canina é responsável por um quadro de depleção quando se encontra em fase de produção viral, principalmente nas células imunocompetentes. Neste sentido, células mononucleares de sangue periférico canino (CMPC) foram coletadas de cães saudáveis, cultivadas e infectadas pela estirpe vacinal CDV (Onderstepoort). Após 24h post-infection (p.i.), as enzimas superóxido dismutase 1 (SOD1), proteína antioxidante 1 (AOP-1) e estresse térmico 70 (Hsp-70) foram detectadas pela reação de imunofluorescência. A expressão do mRNA dos respectivos genes foi realizada em CMPC CDV+ e CDV - após 24h de infecção com a reação em cadeia da polimerase em tempo real. As sondas fluorescentes JC-1 e MitoTracker™

Green foram utilizadas para avaliar potencial de membrana e função mitocondrial, respectivamente. A estirpe vacinal induziu a perda da viabilidade em mais de 80% das células infectadas em comparação ao grupo controle (p = 0,001) após 24 h. A permeabilidade da membrana mitocondrial (Δψ) detectada

pelo uso da sonda MitoTracker™Green e JC-1 revelou um aumento da Δψ e

primeira descrição da alteração de bioenergética mitocondrial induzida pela infecção com o CDV em CMPC cultivadas in vitro.

Palavras-Chave: vírus da cinomose canina, estresse oxidativo, mitocôndrias,

CANINE PERIPHERAL BLOOD MONONUCLEAR CELLS INFECTED WITH

DISTEMPER VIRUS INDUCE MITOCHONDRIAL DYSFUNCTION

ABSTRACT- Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with the manifestation and origin of diseases and disorders. The new paradigm complements the current mitochondrial dogma, whereby molecules present on or inside the mitochondria may act as immune regulators in response to stress or pathogens. Canine distemper virus infection (CDV) is responsible to immunosuppressive stage when the virus replicates among immune cells. For this purpose, canine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) collected from healthy dogs were cultured and infected by CDV vaccine strain (Onderstepoort) and after 24 h post-infection (p.i.) superoxide dismutase (SOD1), antioxidant like protein 1 (AOP-1) and heat shock protein 70 (Hsp-70) enzymes were search in PBMC by immunofluorescence. The expression of mRNA of respective genes was performed in infected and uninfected canine PBMC at 24 h post-infection by real time polymerase chain reaction. Mitochondrial dysfunction was evaluated

by the use of MitoTracker™Green and JC-1 probes at the same post-infection

time. The vaccine strain induced loss of PBMC viability in more than 80% of infected cells in comparison to control group (p<0.001) at 24h post-infection. The mitochondrial membrane permeability (Δψ) searched by MitoTracker™

Green and JC-1 probes revealed an increase of Δψ in the CDV + group

Keywords: canine distemper virus, oxidative stress, mitochondria, Morbillivirus,

13

1 CONSIDERAÇÕES GERAIS

1.1 Aspectos gerais

A cinomose canina é uma doença infecciosa que ocorre mundialmente e infecta todas as famílias da ordem Carnivora (APPEL; SUMMERS, 1999; DEEM et al., 2000). O vírus da cinomose é classificado como pertencente à família Paramyxoviridae, relacionado intimamente, em

termos antigênicos e bioquímicos, ao vírus do sarampo nos seres humanos e o vírus da peste bovina nos ruminantes (BEINEKE et al., 2008). Os três vírus são grupados em conjunto em um único gênero, o Morbillivirus. Os Morbilivirus são

vírus relativamente grandes (150 – 250 nm de diâmetro), contendo RNA com

simetria helicoidal e possuem um envelope de lipoproteína (LAMB & KOLAKOFSKY, 2001; VAN REGENMORTEL et al., 2000).

14

FIGURA 1- a) Esquema ilustrado da partícula viral do vírus da cinomose canina, família Paramyxoviridae, gênero Morbillivirus. Morfologia circular, variando á

pleomórfica, com envelope viral (lipid bilayer), fita simples de ácido ribonucleico (RNA),

15

Em relação ao tropismo celular, o vírus da cinomose canina apresenta uma variedade de órgãos e tecidos que são susceptíveis à replicação viral (BAUMGÄRTNER; ALLDINGER, 2005; DEEM et al., 2000). Diversos são os tipos celulares, de origem primária ou de linhagem que já foram utilizados no estudo da replicação deste vírus, incluindo “African Green

Monkey Kidney cell” (células Vero), “marmoset lymphoid cells” (B95a), “

Madin-Darby Canine Kidney cells” (MDCK), macrófagos e linfócitos caninos (GUO;

LU, 2000; KAJITA et al., 2006; SULTAN et al., 2009; TECHANGAMSUWAN et al., 2009).

Na tentativa de elucidar os eventos celulares envolvidos nos processos de desmielinização e remielinização do sistema nervoso central (SNC), e de buscar estratégias terapêuticas que resolvam ou impeçam os danos gerados, como nas doenças neurodegenerativas que acometem os seres humanos, estudos têm sido desenvolvidos empregando modelos experimentais de desmielinização através da infecção pelo vírus da cinomose (VANDELVELDE et al., 1985; BAUMGÄRTNER ; ALLDINGER, 2005; BEINEKE et al., 2008; SCHWAB et al., 2007; VANDELVELDE ; ZURBRIGGEN, 2005).

16

1.2 Mediadores da morte celular programada

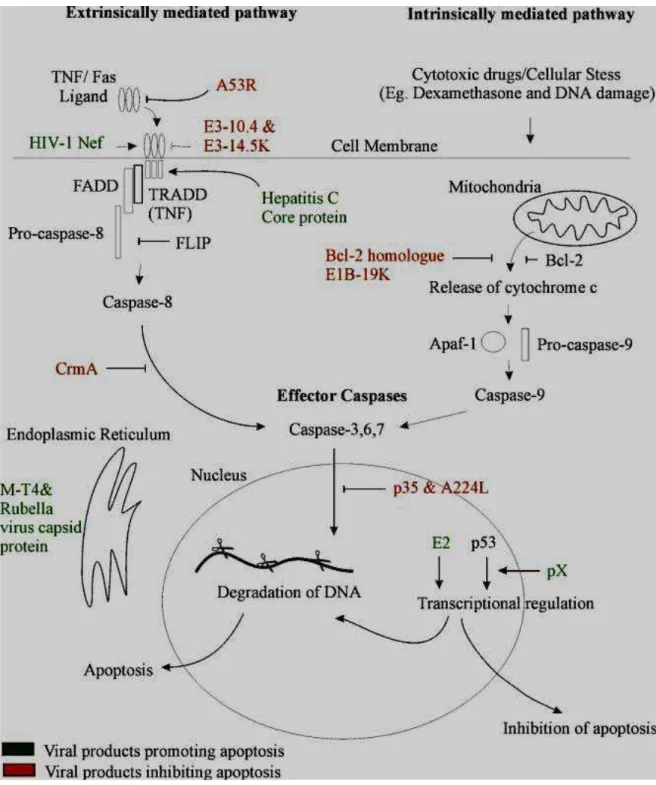

O processo de morte celular programada ou também apoptose, se caracteriza por uma forma de destruição celular pela ativação de uma série, coordenada e programada internamente, de eventos executados por um conjunto exclusivo de conjuntos gênicos (PILLET et al., 2009). Este processo representa um importante papel na homeostasia de todos os organismos multicelulares, eliminando células alteradas, tais como células com mutações genéticas ou infectadas por vírus (PILLET et al., 2009). Fragmentos celulares também conhecidos como corpos apoptóticos são rapidamente fagocitados por células especializadas ou células vizinhas aos fragmentos, evitando assim o início do processo inflamatório (BEST, 2008). O processo de apoptose pode ser iniciado por estímulos fisiológicos e patológicos e está presente em diversas doenças imunossupressivas, em humanos e animais, e na maioria das infecções virais (BEST, 2008).

A morte celular programada pode desempenhar um papel importante no mecanismo imunossupressor em estudos in vitro da infecção do vírus da

cinomose (GUO; LU, 2000). Este estudo concluiu que as estirpes virais utilizadas na formulação de vacinas podem induzir ao processo de morte celular programada, neste caso particular nas células Vero, e este fenômeno seria dependente da replicação celular do vírus da cinomose. Outros descreveram a importância desse processo na patogenia da degeneração oligodendrocítica na cinomose clínica (BEINEKE et al., 2008).

O processo de apoptose é induzido por uma cascata de eventos moleculares que podem ser iniciados de estímulos distintos, culminando na ativação das caspases (cysteine aspartic acid-specific proteases) (KAJITA et

17

condensação da cromatina e fragmentação do DNA (KAJITA et al., 2006). Ademais, estudos descreveram a ativação da caspase 3, 8 e 9 no processo de infecção viral, associando este mecanismo ao processo de morte celular programada no caso da cinomose canina (KAJITA et al., 2006; PILLET et al., 2009; DEL PUERTO et al., 2010)

Em relação à interação vírus-células, especificamente células mononucleares, existe descrição da participação direta e indireta do processo de infecção na destruição celular (SCHOBESBERGER et al., 2005). A participação viral no processo de linfopenia é um evento inicial e a severidade da destruição celular está intimamente correlacionada com a evolução do quadro infeccioso com a consequente persistência viral nos tecidos linfoides e no sistema nervoso central (SCHOBESBERGER et al., 2005).

Estudos recentes demonstraram que alguns vírus desenvolveram mecanismos de prevenir ou pelo menos controlar alguns aspectos ligados ao processo de apoptose (BEST, 2008). Neste sentido, a estirpe viral 5804Pell do vírus da cinomose, considerada virulenta, foi utilizada para verificar a ação direta da infecção viral na depleção do sistema imunológico (PILLET ; VON MESSLING, 2009). Esses autores concluíram que, em monocamadas de células MDCK a infecção pelo vírus da cinomose resultou em um aumento não significativo do processo de apoptose. Em contrapartida, em furões experimentalmente infectados pela mesma estirpe viral, foi possível concluir que uma extensiva infecção viral está associada à morte celular programada e á alterações do ciclo celular. Entretanto, a infecção viral não pode ser considerada a causa principal da leucopenia observada neste modelo biológico (PILLET; VON MESSLING, 2009).

Recentemente, a infecção in vitro da estirpe viral Lederle em

18

ativação extrínseca do mecanismo de morte celular programada decorrente da infecção pelo vírus da cinomose (Del PUERTO et al., 2011a,b). A mesma estirpe viral também induziu em células tumorais HeLa a expressão de mRNA relacionado ao gene da caspase-3, diferentemente entre as células infectadas e não infectadas. Em relação à caspase-8, nenhuma diferença foi descrita entre as células infectadas e não infectadas (Del PUERTO et al., 2011a,b).

Diante do exposto, podemos concluir que a mesma estirpe viral pode ativar tanto a via extrínseca quanto a via intrínseca do processo de apoptose dependendo do tipo celular envolvido. Ademais, nenhum estudo, até a presente data, avaliou os eventos iniciais do processo de morte celular programada em células mononucleares periféricas cultivadas in vitro e subsequentemente

infectadas com o vírus da cinomose. Em contrapartida, em um estudo com o vírus do sarampo, pertencente à mesma família Paramyxoviridae, foi

19

20

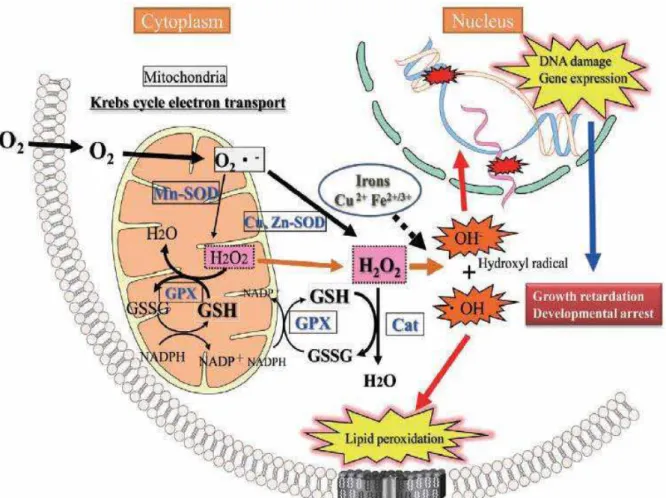

1.3 Mitocôndria e estresse oxidativo

A mitocôndria está envolvida em uma variedade de processos metabólicos incluindo a produção de ATP, homeostase do cálcio, proliferação celular, morte celular programada e síntese de aminoácidos, nucleotídeos e lipídeos (KOSHIBA, 2012). Embora cada mitocôndria tenha seu próprio genoma, a maioria das proteínas mitocondriais é codificada pelo DNA do núcleo (WEST et al., 2011). A distribuição, forma e funcionamento destas organelas são regulados por estímulos intrínsecos e extrínsecos da morte celular programada, os quais em alguns casos incluem os vírus (OHATA ; NISHIYAMA, 2011). O mecanismo de imunossupressão induzido pelo CDV permanece não elucidado. Sabe-se que após a infecção por aerossóis, a replicação viral tem início nos tecidos linfoides do trato respiratório superior e as alterações decorrentes desta infecção incluem atrofia do timo, depleção de células T e B, além de corpúsculos de inclusão em células linfáticas e reticulares. Ainda, tem sido demonstrado que a produção de citocinas do sangue periférico é diminuída (BAUMGÄRTNER; ALLDINGER, 2005).

21

cadeia respiratória (HALLIWEZ ; WHITEMAN, 2004; HOOPER et al., 2012; STONE ; YANG, 2006).

As células são protegidas contra o insulto oxidativo através de produtos antioxidantes naturais, em especial a glutationa, e por diversas enzimas antioxidantes como a superóxido dismutase (SOD1), catalase e glutationa peroxidase (HOOPER et al., 2012; TAKASHI, 2012). A SOD1 catalisa a neutralização do superóxido (O2-) em peróxido de hidrogênio (H2O2) e oxigênio (O2), enquanto a glutationa peroxidase e a catalase neutralizam a produção de H2O2 (HOOPER et al., 2012). Pela rápida eliminação do O2-, a SOD reduz a produção do radical hidroxila atenuando assim os danos oxidativos aos constituintes celulares. Os organismos vivos produzem espécies reativas de oxigênio (ERO) durante processos fisiológicos e em resposta a estímulos exógenos, sendo que a cadeia respiratória mitocondrial é a principal fonte consumidora de oxigênio no sistema celular, assim com também é a maior fonte de ERO (CLOONAN; CHOI, 2012). A produção de ERO é controlada pelo equilíbrio nas reações de oxidação e redução (status redox),

um desequilíbrio no status redox, promove uma produção em excesso de ERO

(CLOONAN; CHOI, 2012; TAKASHI, 2012).

Os organismos possuem mecanismos para protegê-los dos danos causados pelas ERO e que atuam para manter o equilíbrio redox (KOSHIBA, 2012). Estes sistemas de defesa antioxidantes incluem antioxidantes não enzimáticos, como as vitaminas A, C, e ácido úrico; enzimas com propriedades antioxidantes, como as catalases, glutationa peroxidase, p.e. AOP-1, superóxido dismutase (Figura 3) e tioredoxinas (STONE; YANG, 2006; WEST, 2012).

22

sonda JC-1 identifica populações de mitocôndrias com diferentes potenciais de membrana por diferencial em espectro de cor. A sua cor é alterada do verde para o laranja ou vermelho, com o aumento do potencial de membrana (STONE; YANG, 2006). A fluorescência verde do JC-1 ocorre devido à formação de monômeros, apresentando excitação e emissão máximas de 510 e 527 nm, respectivamente, enquanto a fluorescência vermelha do JC-1 é devido à formação de J-agregados, com excitação e emissão máximas de 485 e 585 nm respectivamente (HALLIWELL; WHITEMAN, 2004).

A MitoTracker™Green, considerada uma nova sonda de avaliação

da função mitocondrial, se comparada com a JC-1, não é fluorescente em soluções aquosas e se torna fluorescente quando acumulada no ambiente lipídico da mitocôndria. Os espectros de excitação e emissão máximos são de 490 e 516 nm, respectivamente. Notadamente, esta sonda parece acumular-se preferencialmente na mitocôndria, indiferente do potencial de membrana mitocondrial, tornando-o um instrumento para a possível determinação da massa mitocondrial Porém, de forma contraditória, estudos indicaram que esta sonda reflete o status funcional da mitocôndria (SCOTT, 2010; STONE ; YANG, 2006).

23

do processo de morte celular programada em infecção de células tumorais (MOLOUKI et al., 2010).

24

Um parâmetro importante da funcionalidade mitocondrial é o potencial de membrana (Δψ) (CLOONAN; CHOI, 2012). Esse potencial pode ser

aferido por uso de sondas fluorescentes, que quando atravessam a membrana mitocondrial emitem fluorescência em diferentes comprimentos de onda detectada por microscopia, citometria de fluxo ou espectrofotometria. Em síntese, até a presente data, nenhum estudo avaliou a influência da infecção pelo vírus da cinomose canina no potencial de membrana mitocondrial da célula hospedeira.

Ademais, a mitocôndria possui dois compartimentos individualizados por uma membrana com dupla camada, uma externa e outra interna (KOSHIBA, 2012). Outra característica importante é a presença do seu próprio genoma, constituído de 16 Kb, circular que codifica 13 proteínas correspondentes à exatamente 13 genes. Essas informações estão intimamente relacionadas ao processo de respiração celular para produzir adenosina trifosfato (ATP) (MOLOUKI et al., 2010).

Os produtos reativos de oxigênio que são gerados pela respiração mitocondrial em algumas situações podem ser suprimidos durante o curso da infecção viral (CLOONAN; CHOI, 2012). Concomitante a produção do estresse oxidativo, o aumento da permeabilidade da membrana mitocondrial (Δψ)

ocasionado pela infecção viral pode levar a destruição desta organela (HOOPER et al., 2012). Entretanto, recentes estudos revelaram que em alguns modelos virais a inibição do estresse oxidativo se faz necessário para que o metabolismo celular seja eficiente na manutenção do metabolismo energético para a produção de novas partículas virais (MOLOUKI et al., 2010).

25

2 OBJETIVO GERAL

Avaliar os efeitos da infecção in vitro do vírus vacinal da cinomose

canina em células mononucleares periféricas caninas, relacionados à expressão da enzima SOD (superóxido dismutase-1) e ao emprego de sondas fluorescentes MitoTracker™Green e JC-1 no mecanismo funcional da

mitocôndria após 24 h de exposição viral.

2.1 OBJETIVOS ESPECÍFICOS

2.1.1 Promover o cultivo in vitro de células mononucleares periféricas

caninas (CMPC) saudáveis para realizar a infecção com a estirpe viral vacinal (CDV-Onderstrepoort);

2.1.2 Avaliar parâmetros como viabilidade celular e uso das sondas MitoTracker™Green e JC-1 por citometria de fluxo e

imunocitoquímica;

26

3 CONCLUSÕES

3.1 A infecção de CMPC com a estirpe vacinal do CDV acarretou um aumento da permeabilidade da membrana mitocondrial, evidenciado pela intensa marcação com as sondas MitoTracker™Green e JC-1

concomitante a diminuição da viabilidade celular 24 h após a infecção;

3.2 A expressão de mRNA relacionados aos genes codificadores de SOD-1 e AOP-1 foi considerada estatisticamente superior no grupo CDV + quando comparados aos mesmos no grupo CDV- (p<0.005). Não houve diferença na expressão da Hsp70 entre os dois grupos estudados.

3.3 A infecção das CMPC in vitro com a estirpe vacinal CDV acarreta uma

27

4 REFERÊNCIAS

APPEL, M.J.G; SUMMERS, B.A. Canine distemper: current status. In: CARMICHAEL,

L.E. Recent advances in canine infectious diseases. Ithaca, NY: International

Veterinary Information Service, 1999, p.6.

BAUMGÄRTNER, W; ALLDINGER, S. The pathogenesis of canine distemper virus

induced demyelination: a biphasic process. Experimental models of multiple sclerosis. Springer, New York.Lavi E., Constantinescu, C.S. (Eds) .p. 871–887, 2005.

BEINEKE A; PUFF C; SEEHUSEN, F; BAUMGÄRTNER, W. Pathogenesis and

immunopathology of systemic and nervous canine distemper. Veterinary Immunology

and Immunopathology. doi:10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.09.023. 18 p. 2008.

BEST, M.S. Viral subversion of apoptotic enzymes: escape from death row. Annual

Review Microbiology, v.62, p. 171-192, 2008.

28

DEEM, S.L; SPELMAN, L.H; YATES, R.A; MONTALI, R.J. Canine Distemper in terrestrial carnivores: a review. Journal Zoo Wildlife Medicine, v. 31, p. 441-451, 2000.

DEL PUERTO, H.L.; MARTINS, A.S.; MILSTED, A.; FAGUNDES, E.M.S.; BRAZ, G.F.; HISSA, B.; ANDRADE, L.O.; ALVES, F.; RAJÃO, D.S.; LEITE, R.C.; VASCONCELOS, A.C. canine distemper virus induces apoptosis in cervical derived cell lines. Virology Journal, v. 8, e334, 2011a.

DEL PUERTO, H.L.; MARTINS, A.S.; MORO, L.; MILSTED, A.; ALVES, F.; BRAZ, G.F.; VASCONCELOS, A.C. caspase 3/8/9, bax and Bcl-2 expression in the cerebellum, lymph nodes and leucocytes of dogs naturally infected with canine distemper virus. Genetics and Molecular Research, v.9, p.151-161, 2010.

DEL PUERTO, HL.; MARTINS, A.S.; BRAZ, G.F.; ALVES, F.; HEINEMANN, M.B.; RAJÃO, D.S.; ARAÚJO, E.C.; MARTINS, S.F.; NASCIMENTO, D.R.; LEITE, R.C.; VASCONCELOS, A.C. Vero cells infected with Lederle strain of canine distemper virus have increased Fas receptor signaling expression at 15 h post-infection. Genetics and Molecular Research, v. 10, p. 2527-2533, 2011b.

DERAKHSHAN, M. Effect of measles virus (MV) on mitochondrial respiration. Indian

29

GUO, A; LU, C. P. Canine distemper virus causes apoptosis of Vero cells. Journal

Veterinary Medicine, v. 47, p.183–190, 2000.

HALLIWELL, B.; WHITEMAN, M. Measuring reactive species and oxidative damage in

vivo and cell culture: how should you do it and what do the results mean? British

Journal Pharmacology, v.142, p.231-255, 2004.

HAY, S.; KANNOURAKIS, G. A time to kill: viral manipulation of the cell death program.

Journal General Virology,v. 83, p. 1547-64, 2002.

HOOPER, P.L.; HIGHTOWER, L.E.; HOOPER, P.L. Loss of stress response as a consequence of viral infections: implications for disease and therapy. Cell stress and chaperones, doi: 10.1007/s12192-012-0352-4, 2012.

ITO, M; WATANABE, M; IHARA ,T; KAMIYA, H; SAKURAI, M. Measles virus induces apoptotic cell death in lymphocytes activated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

(PMA) calcium ionophore. Clinical Experimental Immunology, v. 108. p. 266–271,

1997.

KAJITA, M; KATAYAMA, H; MURATA, T; KAI, C; HORI, M; OZAKI, H. Canine Distemper Virus induces apoptosis through Caspase-3 and -8 activation in Vero cells.

30

KOSHIBA, T. Mitochondrial-immediate antiviral immunity. Biochimica et Biophysica

Acta. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamrc. 2012.03005, 2012.

LAMB, R.A; KOLAKOFSKY, D. Paramyxoviridae: the viruses and their replication. In:

KNIPE, D.M.; HOWLEY, P.M. (Eds) Fields of Virology. 4th.ed. Philadelphia:

Lippencott, Willians and Weekings, 2001.p.1305-1443.

MARTELLA, V.; ELIA, G.; LUCENTE, M.S.; DACARO, N.; LORUSSO, E.; BANYAI, K.; BLIXENKRONE-MØLLER, M.I.; LAN, N.T.; YAMAGUCHI, R.; CIRONE, F.; CARMICHAEL, L.E.; BUONAVOGLIA, C. Genotyping canine distemper virus (CDV) by hemi-nested multiplex PCR provides a rapid approach for investigation of CDV outbreaks. Veterinary Microbiology, v. 122, p. 32-42, 2007.

MOLOUKI, A.; HSU, YI-TE.; JAHANSHI, R. I. F.; ROSLI, R.; YUSOFF, K. Newcastle virus infection promotes Bax redistribution to mitochondria and cell death in HeLa cells.

Intervirology, v.53, p.87-94, 2010.

NORRIS, J.M; KROCKENBERGER, M. B; BAIRD, A.A; KNUDSEN G. Canine distemper: re-emergence of an old enemy. Australian Veterinary Journal, v. 84, p. 362–363, 2006.

OHATA, A.; NISHIYAMA, Y. Mitochondria and viruses. Mitochondrion, v.11, p.1-12,

31

PARDO, I.D.R; JOHNSON, G.C; KLEIBOEKER, S.B. Phylogenetic characterization of canine distemper viruses detected in naturally infected dogs in North America. Journal Clinical Microbiology, v. 43. p. 5009–5017. 2005.

PILLET, S.; VON MESSLING, V. canine distemper virus selectively inhibits apoptosis progression in infected immune cells. Journal Virology, v.83, p. 6279-6287, 2009.

SCHWAB, S; SEELIGER, H.F; PAPAIOANNOU, N; PSALLA, D; POLIZOPULOU, Z; BAUMGÄRTNER, W. Non-suppurative Meningoencephalitis of unknown origin in cats

and dogs: an immunohistochemical study. Journal Comparative Pathology,v.136. p.

96-110, 2007.

SCHWARTZMAN, R.A.; CIDLOWSKI, J.A. Apoptosis: molecular biology of programmed cell death. Endocrinology Review,v.14, p. 133-151, 1993.

SCOTT, I. The role of mitochondria in the mammalian antiviral defense system.

Mitochondrion, v. 10, p. 316-320, 2010.

SHCOBESBERGER, M.; SUMMERFIELD, A.; DOHERR, M.G.; ZURBRIGGEN, A.; GRIOT, C. canine distemper virus-induced depletion of uninfected lymphocytes is

associated with apoptosis. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology, v. 104,

32

SIES, H. Strategies of antioxidant defense. European Journal Biochemistry, v. 215, p. 213–219, 1993.

STONE, J.R.; YANG, S. Hydrogen peroxide: a signaling messenger. Antioxidant

Redox, v. 8, p. 243-270, 2006.

SULTAN, S.; LAN, N.T.; UEDA, T.; YAMAGUCHI, R.; MAEDA, K.; KAI, K. Propagation

of Asian isolates of canine distemper virus (CDV) in hamster cell lines. Acta

Veterinaria Scandinavica, v.51, 38, 2009.

TAKAHASHI, M. Oxidative stress and redox regulation on in vitro development of

mammalian embryos. Journal Reproduction Development, v.58, p.1-9, 2012.

TECHANGAMSUWAN, S.; HAAS, L.; ROHN, K.; BAUMGÄRTNER, W.; WEWETZER, K. Distinct tropism of canine distemper virus strains to adult olfactory ensheathing cells and Schwann cells in vitro. Virus Research, v.144, p. 195-201, 2009.

33

VALYI-NAGY, T.; DERMODY, T.S. Review: Role of oxidative damage in the pathogenesis of viral infections of the nervous system. Histology and Histopathology Celular and Molecular Biology, v.20, p.957-967, 2005.

VAN REGENMORTEL, H.V.M.; FAUQUET, C.M.; BISHP, D.H.L.; CARSTENS, E.; ESTES, M.K.; LEMON, S.; MANILOFF, J.; MAYO, M.A.; McGREOCH, D.; PRINGLE,

C.R.; WICKNER, R.B. (Eds). Virus taxonomy: proceedings of seventh report of

international committee on taxonomy of viruses. New York. Academic Press, 2000.

VANDEVELDE, M; ZURBRIGGEN A. Demyelination in canine distemper virus infection: a review. Neuropathology, 109. p.56–68. 2005.

VANDEVELDE, M; ZURBRIGGEN, A; HIGGINS, R.J; PALMER, D. Spread and

distribution of viral antigen in nervous canine distemper. Acta Neuropathology, v. 67. p.211–218. 1985.

WEST, A.P.; SHADEL. G.S.; GHOSH, S. Mitochondria in innate immume responses.

34

CANINE PERIPHERAL BLOOD MONONUCLEAR CELLS INFECTED WITH DISTEMPER VIRUS INDUCE MITOCHONDRIAL DYSFUNCTION

Sabrina D. Agostinho, Flavio T. L. B. Roncatti, Talita F. Antello, Natielle W. Rodrigues, Jessica K. L. Rossi, Tereza C. Cardoso

35

Abstract

Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with the manifestation and origin of diseases and disorders. The new paradigm complements the current mitochondrial dogma, whereby molecules present on or inside the mitochondria may act as immune regulators in response to stress or pathogens. Canine distemper virus infection (CDV) is responsible to immunosuppressive stage when the virus replicates among immune cells. For this purpose, canine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) collected from healthy dogs were cultured and infected by CDV vaccine strain (Onderstepoort) and after 24 h post-infection (p.i.) superoxide dismutase (SOD1), antioxidant like protein 1 (AOP-1) and heat shock protein 70 (Hsp-70) enzymes were search in PBMC by immunofluorescence. The expression of mRNA of respective genes was performed in infected and uninfected PBMC at 24 h post-infection by real time polymerase chain reaction. Mitochondrial dysfunction was evaluated by the use

of MitoTracker™Green and JC-1 probes at the same post-infection time. The

vaccine strain induced loss of PBMC viability in more than 80% of infected cells in comparison to control group (p<0.001) at 24h post-infection. The mitochondrial membrane permeability (Δψ) searched by MitoTracker™Green

and JC-1 probes revealed an increase of Δψ in the CDV + group (p<0.0012) in

comparison to uninfected PBMC. In contrast, the expression of mRNA of AOP-1 and SOD1 were considered higher, whereas the Hsp-70 has no difference in its expression between CDV+ and CDV- groups. PBMC infected by CDV increased AOP-1 and SOD1 gene transcription, an antioxidant cell defense, concomitant to a reduce level of PBMC viability. The viral replication also seems to regulate mitochondrial function by modify the membrane potential. However, at this point, host cells have developed a defense producing mediators related to protect against oxidative insult. This is the first description of mitochondria bioenergetics alteration induced by CDV infection on in vitro cultured PBMC.

Keywords: canine distemper virus, oxidative stress, mitochondria, Morbillivirus,

36

Introduction

Canine distemper virus (CDV), a negative stranded RNA Morbillivirus,

causes a multisystemic disease in dogs, which is associated with severe immune suppression. In this respect, several studies have been done in order to find evidences of CDV main role in induction of this immune suppression stage, but the direct involvement of CDV infection on immune depletion is not well characterized. In vivo studies have demonstrated that CDV infection induced a severe CD3+T cell and CD21+B cell depletion in dogs at 3 days post-infection.

Oxidative stress triggers a cascade that leads to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), accumulation of lipid peroxidation products that leads to severe systemic inflammatory responses. The antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), antioxidant like protein 1 (AOP-1) and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), play important roles in cell defense against oxidative stress. Viral infection typically results in the perturbation of cellular processes that can serve to trigger cell death via the mitochondrial pathway. Successful replication of many viruses, therefore, depends on the ability of the virus to prevent apoptosis induced by the mitochondrial pathway. The maintenance of mitochondrial respiration during viral infection is essential for ensuring that sufficient ATP is available for viral replication to proceed, while concomitantly inhibiting apoptosis induced by oxidative stress. Determining how CDV interferes with cell-death pathways will not only improve our understanding of viral pathogenesis but also has the potential to advance our understanding of the processes that normally control of cellular death pathways. For example, oxidative stress is essential for apoptotic induction to proceed in response to many stimuli; however, the mechanisms by which viruses induce mitochondrial dysfunction are unknown.

37

considered chaperones responsible for defensive maneuvers, including generation of fever, immunological defense, interferon production, and reduction of protein synthesis, including reducing of Hsp synthesis, which set hosts up for adverse symptoms. Canine distemper virus (CDV) is a member of

Paramyxoviridae, genus Morbillivirus. In parallel, Newcastle disease virus

(NDV) belonging to the same family, has been described to manipulate the Hsp production among different infected cells. For example, infection with avirulent B1-Hitchner and NJ-LaSota markedly raised Hsp proteins levels, while the virulent strain AV severely reduced Hsp70 and Hsp23 levels. However, this mechanism was not addressed for CDV infections.

For this purpose, canine peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) collected from healthy dogs were cultured and infected by CDV vaccine strain (Onderstepoort) and after 24 h post-infection (p.i.) superoxide dismutase (SOD1), antioxidant like protein 1 (AOP-1) and heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) enzymes were search in PBMC by immunofluorescence. The expression of mRNA of respective genes was performed in infected and uninfected canine PBMC at 24 h post-infection by real time polymerase chain reaction. Mitochondrial dysfunction was evaluated by the use of MitoTracker™ Green

and JC-1 probes at the same post-infection time

Material and methods

Isolation of canine PBMC and virus infection

38

interface were aspirated by pipette and washed twice by suspension in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution and centrifuged at 300 x g for 30 min.

The resulting cell pellet was ressuspended in a small volume of PBS and viable cell concentration was determined by microscopic examination using trypan blue exclusion method. Viability was > 90% in all samples. The cells were ressuspended with 2 mM glutamine, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 100 UI penicillin and 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich®) at approximately 1 x 106 PBMC/ml. PBMC (1 x 106 ml-1) were cultured in 6 well polystyrene plaques (Nunc, 142489, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Rochester, NY) at 37 °C, 5% CO2.

Modified live canine distemper virus (Onderstepoort strain) vaccine (Galaxy® D, Schering-Plough, Animal Health Corporation, NE, USA) was reconstituted with 0,5 ml of RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) and was added to PBMC culture immediately upon reconstitution at a 1:10 dilution. The culture infection were performed in triplicate wells and the entire content of one well from each group (CDV + and CDV -) was aspirated after 24 h of incubation and frozen at – 86 °C until needed.

Indirect immunofluorescence to assay SOD1, AOP-1, Hsp70

PBMC from both groups CDV+ and CDV- were washed three times in PBS and fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 24 h at 4 °C. The samples were then rinsed with PBS and permeabilized with proteinase K (10 μg/mL, Invitrogen) for

15 min at room temperature. After pre-treatment with proteinase K (10 μg/mL)

at 4 °C, the slides were incubated overnight with primary antibodies against mitochondrial superoxide dismutase, anti-oxidative protein 1 and stress response heat shock protein 7 (mouse anti-SOD1; anti-AOP-1 and anti-Hsp70.1, respectively) diluted 1:50 in antibody diluent (PBS plus 0.1 % of

(4`-6-39

diamino-2-phenylindole; Sigma-Aldrich®) for 15 min at room temperature before mounting the slides in the dark. stained slides were observed under an AxioImager A.1 light and ultraviolet microscope connected to an AxioCam MRc camera (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), and micrographs were processed with AxioVision 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss).

MitoTracker™Green FM and JC-1 staining

To evaluate the mitochondrial function, infected and uninfected PBMC were washed in PBS and then fixed with 4% (w/v) formaldehyde and were search for

intensity label of MitoTracker™Green FM and JC-1 probes. The MitoTracker™

Green FM was diluted in DMSO at 10 nM per slide direct applied on fixed PBMC and incubated for 10 min at 38.5 °C. The mitochondrial distribution in the cytoplasm of PBMC appeared as increased areas of fluorescence intensity or aggregates detected by fluorescence. Mitochondrial activity was qualified based on JC-1 (5,5´, 6,6´-tetrachloro-1,1´, 3,3´-tetraethyl-benzimidazoyl-carbocyanine iodide) staining. JC-1 monomers were detected with a green filter. JC-1 dimers that formed on mitochondrial membranes with high potential were detected via

a red filter. To measure the fluorescence intensity (MitoTracker™ Green FM

emission 500 nm, JC-1 red filter 515 nm and green filter 488 nm stained slides were observed under an AxioImager A.1 light and ultraviolet microscope connected to an AxioCam MRc camera (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), and micrographs were processed with AxioVision 4.8 software (Carl Zeiss).

Determination of gene transcripts of mitochondrial activity (SOD1),

antioxidant protection (AOP-1) and stress response (Hsp70) by real time

polymerase chain reaction

The abundance of mRNA transcripts for genes related to mitochondrial activity antioxidant protection (AOP-1), manganese-superoxide dismutase (SOD1) and

40

reaction (PCR), and these primers and probes were purchased (Applied Biosystem™).Total RNA was isolated from CDV+ and CDV

– groups using the

PureLink® viral RNA/DNA extraction kit, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). The total RNA was eluted in 20 μL of ultra-pure water and

treated with 0.5 IU DNAse. The reverse transcriptase reaction (RT) was immediately performed using 0.5 μg oligo (dT) primers (Invitrogen®). The

reaction mix consisted of 200 μM of each dNTP, 1 x RT buffer, 2 μL DTT 0.1 M,

40 IU RNase inhibitor and 200 IU SuperScript II (Invitrogen®). The RT reaction was performed at 42 °C for 52 min, with a final incubation at 70 °C for 15 min. The qPCR was carried out and analyzed by the software on a StepOnePlus® real time instrument (Applied Biosystems™). The real time PCR mixtures (50 µl)

contained 1.2 µg of cDNA, 400 nM primers and 200 nM probes FAM-labeled customized for dog sequences (Applied Biosystems™) were used. The PCR

was initiated by sequential amplification of 40 cycles at 95°C (15s) and 60°C (60s). The results were obtained from three replicates of each sample to ensure representative and accuracy pipetting. The expression of canine GADH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) gene was also quantified in a similar way for normalization. The comparative delta-delta Ct method was used

to analyze the results with the expression level of the respective target genes (mRNA relative quantification) at the corresponding time point in infected and uninfected PBMC in comparison to GADH Ct values.

Statistical analysis

All of the experiments were performed at least in triplicate. Results of representative experiments are presented. Descriptive statistics include the mean ± standard deviation (s.d). A p-values < 0.005 was considered significant.

Results and Discussion

41

proteins were detected in both groups (CDV+ and -), however more intense fluorescence could be detected CDV + PBMC. These results suggested that at early stage of virus exposure, PBMC activate the anti-oxidative defense. These observations have been described for other Morbilliviruses (9), also incriminated

the virus infection on mitochondria respiration performance (10). This

hypothesis, could sustain loss of mitochondrial membrane permeability (Δψ)

observed in the present study. In addition, the mitochondrial viability was

searched by MitoTracker™Green and JC-1 probes revealed an increase of Δψ

in the CDV + group (p<0.0012) in comparison to uninfected PBMC, results also reported by others studies (5, 9). Moreover, the expression of mRNA of AOP-1 and SOD1 were considered higher in CDV + group, whereas the Hsp70 revealed no difference in its expression between CDV+ and CDV- groups. PBMC infected by CDV increased AOP-1 and SOD1 gene transcription, an antioxidant cell defense (7), concomitant to a reduce level of PBMC viability. These results showed for the first time, an important issue of host-virus defense based on cellular metabolism which can provide important keys to drug development.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank FAPESP for financial support. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

CORRESPONDENCE TO

42

References

CLOONAN, S.M.; CHOI, A.M.K. Mitochondria commanders of innate immunity and disease? Current Opinion in Immunology, v.24, p. 32-40, 2012.

DEL PUERTO, HL.; MARTINS, A.S.; BRAZ, G.F.; ALVES, F.; HEINEMANN, M.B.; RAJÃO, D.S.; ARAÚJO, E.C.; MARTINS, S.F.; NASCIMENTO, D.R.; LEITE, R.C.; VASCONCELOS, A.C. Vero cells infected with Lederle strain of canine distemper virus have increased Fas receptor signaling expression at 15 h post-infection. Genetics and Molecular Research, v. 10, p. 2527-2533, 2011b.

DEL PUERTO, H.L.; MARTINS, A.S.; MILSTED, A.; FAGUNDES, E.M.S.; BRAZ, G.F.; HISSA, B.; ANDRADE, L.O.; ALVES, F.; RAJÃO, D.S.; LEITE, R.C.; VASCONCELOS, A.C. canine distemper virus induces apoptosis in cervical derived cell lines. Virology Journal, v. 8, e334, 2011a.

43

FIGURE 1- Immunofluorescence assay to detect AOP-1 (antioxidant protein like 1), SOD-1

(superoxide dismutase 1) and HsP-70 (heat shock protein 70) antigens in PBMC corresponding to CDV + (A, C and E, respectively) and CDV – (B, D and F,

44

FIGURE 2- MitoTrackerTMGreen FM labeling under fluorescence (500 nm) demonstrates an

45

FIGURE 3 - Expression of GADPH, AOP-1, SOD-1, and HsP-70 mRNA in infected (CDV +) and uninfected (CDV-) PBMC groups. * p < 0.005.

*