THE ROLE OF EDUCATION IN M INI-M ENTAL

STATE EXAM INATION

A study in Northeast Brazil

Paulo Roberto de Brito-M arques

1, José Eulálio Cabral-Filho

2ABSTRACT - Background: There is evidence that schooling can influence performance in cognitive assessement tests. In develop-ing countries, formal education is limited for most people. The use of tests such as Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), could have an adverse effect on the evaluation of illiterate and low education individuals. Objective: To propose a new version of MMSE as a screening test to assess Illiterate and low education people. Method: A study was carried out enrolling 232 individuals, aged 60 or more of low and middle socio-economic classes. Three groups were studied: Illiterate;1-4 schooling years; 5-8 schooling years. The new version (MMSE-mo) consisted of modifications in copy and calculation items of the adapted MMSE (MMSE-ad) to Portuguese language.The maximum possible score was the same in the two versions: total, 30; copy, 1 and calculation, 5. Results: In the total test score ANOVA detected main effects for education and test, as well as an interaction between these factors: high-er schooling individuals phigh-erformed betthigh-er than lowhigh-er schooling ones in both test vhigh-ersions; scores in MMSE-mo whigh-ere highhigh-er than in MMSE-ad in every schooling group. Conclusion. Higher schooling levels improve the perfomance in both test versions, the copy and calculation items contributing to this improvement. This might depend on cultural factors. The use of MMSE-mo in illiterate and low school individuals could prevent false positive and false negative cognitive evaluations.

KEY WORDS: mini-mental state examination, cognition, education, cognitive assessement.

O papel da educação no mini exame do est ado ment al: um est udo no Nordest e do Brasil

RESUMO - Contexto: Existem evidências de que a escolaridade pode influenciar o desempenho em testes de avaliação cognitiva. Já que em paises subdesenvolvidos o nível educacional da maioria da população é baixo, isso poderia prejudicar resultados de avaliação por meio de testes.Assim é oportuno adequar o mini exame do estado mental (MEEM) a populações de baixa escolaridade. Objetivo: Propor nova versão do MEEM como um teste geral para avaliar indivíduos analfabetos e com baixa escolaridade. Método: Foram estudadas 232 pessoas de ambos os gêneros com 60 ou mais anos de idade, de classes socio-econômicas média e baixa. Foram con-siderados 3 grupos: analfabetos; 1-4 anos e 5-8 anos de escolaridade. A nova versão (MEEM-mo) consistiu de modificações nos itens cópia e cálculo do MEEM adaptado para a língua portuguesa (MEEM-ad). O escore máximo possível foi o mesmo nas duas versões: total 30 pontos; cópia, 1; cálculo, 5 pontos. Resultados: No escore total, o teste de ANOVA detectou efeitos principais para teste e escolaridade, assim como interação entre estes fatores: indivíduos com escolaridade mais alta realizaram melhor ambos os testes do que aqueles com mais baixa escolaridade. Os escores do MEEM-mo foram mais elevados do que os do MEEM-ad, em cada grupo de escolaridade. Conclusão: Indivíduos com maior escolaridade apresentam melhor performance em ambas as versões dos testes; os itens cópia e cálculo foram responsáveis por este resultado. Isto pode depender de fatores culturais. O uso do MEEM-mo em indiví-duos analfabetos e com baixa escolaridade pode prevenir resultados tanto falso-positivos como falso-negativos nas avaliações cog-nitivas.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: mini exame do estado mental, cognição, educação, avaliação cognitiva.

Assessment of cognitive function is essential for accurate diagnosis and management in general neurological practice. Detailed assessment by the neurologist and psychologist requires a high degree of specialist training and is time-con-suming. It is desirable to have a standardized simple and quick test of cognitive function which could be routinely used by the

admiting physician1.Among the cognitive tests there is the

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) which was proposed to dif-ferentiate non specified organic brain syndrome and depres-sion from normal patients. It is useful in quantitatively estimat-ing the severety of cognitive impairment and in documentestimat-ing serially cognitive changes2. It can be also used in

communi-1Behavioral Neurology Unit, Department of Neurology, Faculty of M edical Sciences University of Pernambuco, Recife PE, Brazil;2Instituto M aterno Infantil de

Pernambuco - (IM IP), Recife PE, Brazil.

Received 6 June 2003, received in final form 1 October 2003. Accepted 18 November 2003.

ty-based epidemiologic studies to evaluate the current men-tal functioning of participants. Assessing MMSE in research protocols is particularly important for establishing the inci-dence or prevalence of cognitive impairment and for examin-ing correlates of mental status3. Since the general

practition-ers are usually the prime mover in ensuring that medical and social needs of their patients must be recognized and met, it seems w orth determining how w ell informed they are about the health and welfare of their older patients4. However, there

is evidence that clinicians have often difficulty in recognizing disturbances of cognition among their patients5. Williamson

et al.4, surveying an elderly population, found that only 13%

of demented subjects w ere recognized as such by the physi-cians in charge of their care. Another study showed that 37% of cognitively impaired general medical ward patients were unidentified by physicians, while nurses failed to identify 55% and medical students, 46% 6. Other authors, studying 33 patients with cognitive impairment on a neurologic in-patient service, found that 30% of them w ere not recognized by the attending neurologists, and 87% by general practitioners as well7.Therefore, is low for neurologists, the capacity to

recogni-ze and diagnose these disorders. Evidence that psychiatric disorders are common among neurological patients and that they are frequently unrecognized w ould support the need for further psychiatric training of neurologists. Potencially such fai-lure to recognize cognitive impairments has considerable impli-cations for patient care, as such changes are often the first indi-cation of many underlying neuropathologic conditions7.

Considering psychiatrist’s standardized clinical diagnosis as a criterion, the M M SE is 87% sensitive and 82% specific in de-tecting dementia and delirium among hospital patients on a general medical ward5. The false positive ratio is 39% and the

false negative ratio is 5%. All false positive people had less than 9 years of formal education. So, the M M SE has been show n to lack specificity in poorly educated persons, partic-ularly those who did not attend high school5. Conversely, it has

been observed a number of highly educated dement patients whose MMSE scored the conventional normal range8. It is

pos-sible that performance on specific MMSE items could be relat-ed to relat-education. In fact, several studies have show n that low M M SE scores are correlated w ith low instructional level and poorly educated subjects score below 26 even w ithout de-mentia. On the other hand equations have been developped at adjusting M M SE scores for educated people, because spe-cific items of the M M SE are influenced by education10. So the

use of tests w hich include problems beyond the comprehen-sion capacity of an individual could mask the evaluation of this individual´s insight for the same test. Items measuring recall of three w ords, pentagon copy, and orientation in time seem to be most sensitive to both normal aging and dementing ill-nesses11. According to Fratiglioni et al.12, the performance on

the MMSE is variable among countries. This may be due to

dif-ferent degrees of education in the population, or to difdif-ferent curricula structures of the same schooling level in different coun-tries.Thus,“ norms” or “ adjustment techniques” derived from one country can not be considered universally applicable. In order to prevent the possibility of education to mask the result of this test and, as a consequence, to represent a potential risk factor for the cognitive assessment, it is opportune to reassess the validity of the M M SE w henever it is going to be used in a new population. In developping countries, such as Brazil, most of people have a schooling level lower than eight years13.

The main aim of the present study was to propose a MMSE modified version as a screening test to assess low schooling old people in Brazil.

M ETHOD

A randomized cross-sectional study was performed w ith 232 individuals of both genders, aged 60 or more years old (69.4 ± 6.8 years), belonging to low and middle socio-economic classes, residents in Olinda city, Pernambuco, Brazil. Previously to applying the test peo-ple w ere inquired about their normal daily routine. Peopeo-ple able to conduct theirselves and recognize the primary and secondary colors, the time in a clock, cash money, and capable to use a tin opener were admitted to the study. A clinical interview was proceeded in order to investigate neurological and psychiatric diseases. People with low visu-al or auditory acuity, motor or rheumatic disturbance, chronic visu- alco-holism, cardiovascular disease, recent head trauma (last 12 months) or not motivated, w ere excluded. Three groups w ere formed accord-ing to the schoolaccord-ing level, as follows: group illiterate (n= 28) - individ-uals w ithout any formal schooling instruction; group 1-4 degree (n= 119) - individuals from 1 to 4 years of formal instruction; and group 5-8 degree (n= 85) - individuals from 5 to 8 years of formal instruc-tion.

The original M M SE2, adapted to the Portuguese language14

(thereafter called M M SE-ad) was compared to a modified version of it (thereafter called M M SE-mo) (see appendix). The modification consisted of: first, the copy of intersecting apendice pentagons (M M SE-ad) was changed to the copy of an intersecting equilateral triangles (M M SE-mo); second, the subtraction 7 from 100, and then 7 from the result, repeated 5 times (M M SE-ad) was changed to the serial 1 subtracted from 25 backward, and then 1 from the result, repeat-ed 25 times (M M SE-mo). Each subject of the sample was submittrepeat-ed consecutively to the two versions, first ad, and second MMSE-mo. Concerning to the copy and calculation items the MMSE-mo ver-sion was applied immediately after the same items of the M M SE-ad version. Both test versions had the maximum possible score equiva-lent to 30 points, copy and calculation items having maximum score equivalent to1 and 5, respectively.

Aggreement betw een M M SE-ad and M M SE-mo tests concern-ing the scores obtained in copy item was determined by Cohen´s Kappa aggreement coeficient.Aggreement between the tests concerning the scores obtained in calculation item was determined by Kappa weight-ed aggreement coeficient15. The chi square test was used to compare

com-parisons of means. Comcom-parisons of mean values not fulfilling para-metric requirements w ere made by Kruskal-Wallis analysis of vari-ance follow ed by Dunn test. The null hypothesis was rejected w hen p ≤0.05. The statistic software Sigma Stat 2.0 was used for calcula-tion.

RESULTS

In the copy item (Table 1) a poor agreement betw een M M SE-ad and M M SE-mo was observed in 1-4 years degree (K= 0.14) and in 5-8 years degree (K= 0.18) groups.The agree-ment for the illiterate group was fair ( K= 0.35).

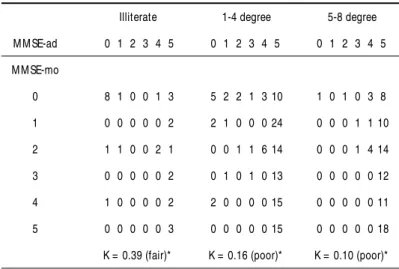

Like in copy item the agreements between the tests in cal-culation scores (Table 2) w ere poor in 1-4 and 5-8 schooling degree (K= 0.16 and K= 0.10, respectively) and fair for illit-erates (K= 0.39).

From the results expressed in Table 1, we can observe also that global aggreement (g.a) for the copy item - defined as the addition of WW plus CC answ ers of the same individual -between MMSE-ad and MMSE-mo tests, presented the follow-ing proportions: illiterate 21/28 (75%), 1-4 degree 59/119

(49% ), and 5-8 degree 42/85 (49% ) (Chi-square= 6.41, p= 0.040). For the calculus item (Table 2) g.a show ed the fol-low ing proportions: illiterate 11/28 (39%), 1-4 degree 23/119 (19% ), and 5-8 degree 19/85 (22% ) (Chi-square= 7.09, p= 0.029). The g.a for copy and calculation betw een 1-4 and 5-8 degree did not differ significantly. How ever, each one of these groups differ from illiterate (p< 0.01) and (p< 0.01), respectively.

Comparing the total scored values between the tests (Table 3) ANOVA indicated a significant main effect for test (p < 0.001) and for schooling degree (p < 0.001) as w ell as an interac-tion betw een these tw o factors (p = 0.007). The values w ere significantly higher for M M SE-mo than for M M SE-ad, in every schooling degree. Moreover, in both tests illiterates scored low-er than litlow-erates ones (p< 0.01).

In Table 4, w e can observe that in every schooling degree MMSE-mo produced higher proportions of individuals answer-ing correctly to copy than M M SE-ad: illiterate, (p< 0.034); 1-4 years, (p< 0.001); and 5-8 years, (p< 0.001). In both test ver-sions, a significant difference was also observed among

schoo-Appendix

Patient. . . Examiner . . . Date. . .

M INI-M ENTAL STATE EXAM INATION IN NORTHEAST BRAZIL M aximum Score

Score

ORIENTATION

5 ( ) What is the (day) (date) (month) (year) (hour) ? 1 point for each correct.

5 ( ) Where are w e:* (place) (bulding) (district) (city or tow n) (state) ? 1 point for each correct. * Ask the name of this place and point out your finger dow n simultaneously.

REGISTRATION

3 ( ) Name 3 objects: 1 second to say each. Then ask the patient all after you have said them. Give 1 point for each correct answ er. Count trials and record.

ATTENTION AND CALCULATION

5 ( ) Serial 7´s. 1 point for each correct. Stop after 5 answ ers, and serial 1 subtracted from 25 ( ) backward, and then 1 from the result, repeated 25 times. 1 point for each 5 itens correct.

RECALL

3 ( ) Ask for the 3 objects repeated above. Give 1 point for each correct. LANGUAGE

9 ( ) Name a pen, and wacth (2 points)

Repeat the follow ing “ No ifs, ands or buts,” (1 point)

Follow a 3-stage command: “ Take a paper in your right hand, fold it in half, and give me it” (3 points) Read and obey the follow ing: close your eyes (1 point)

Write a sentence (1 point)

Copy of a pair of intersecting pentagons and copy of a pair of intersecting equilateral triangles (1 point for each correct copy).

ling groups: M M SE-ad (Chi-square= 6.095; p= 0.047) and M M SE-mo (Chi-square= 12.178; p= 0.002). In both test ver-sions the illiterate groups presented low er proportions of cor-rect answ ers than the literate ones.

Mean scores for calculation (Table 5) indicate that, in MMSE-mo, individuals performed better than in M M SE-ad, for all schooling degrees: Illiterate (p= 0.011), 1-4 years (p< 0.001) and, 5-8 years (p< 0.001). For each test in particular, significant dif-ference among schooling degrees was detected: (M M SE-ad,

p< 0.018); (M M SE-mo, p< 0.001). By comparing schooling groups w e can verify that, in M M SE-ad, the first group (illit-erate) is similar to the second one, and differ of the third schooling group (p< 0.05). How ever, the second group does not differ from the third group, the higher score having been verified in this last group. In the M M SE-mo, w e observe that the illiterate scored low er than 1-4 and 5-8 degrees (p< 0.05), but these tw o last groups did not differ betw een them.

Table 1. Distribution, of the individuals according to agreement of their scores for copy in M M ad and M M SE-mo tests.

M M SE-ad

Illiterate 1-4 degree 5-8 degree

W C W C W C

W 18 7 37 56 15 43

C 0 3 4 22 0 27

K= 0.35 (fair)* K= 0.14 (poor)* K= 0.18 (poor)*

* according to Altmam15; W = w rong; C = correct.

Table 2. Distribution of individuals according to agreement between ad and MMSE-mo tests

Illiterate 1-4 degree 5-8 degree M M SE-ad 0 1 2 3 4 5 0 1 2 3 4 5 0 1 2 3 4 5 M M SE-mo

0 8 1 0 0 1 3 5 2 2 1 3 10 1 0 1 0 3 8

1 0 0 0 0 0 2 2 1 0 0 0 24 0 0 0 1 1 10

2 1 1 0 0 2 1 0 0 1 1 6 14 0 0 0 1 4 14

3 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 0 1 0 13 0 0 0 0 0 12

4 1 0 0 0 0 2 2 0 0 0 0 15 0 0 0 0 0 11

5 0 0 0 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 15 0 0 0 0 0 18

K = 0.39 (fair)* K = 0.16 (poor)* K = 0.10 (poor)*

* according to Altmam15 .

Table 3. M ean scores for M M SE-ad and M M SE-mo of 232 individuals according to the schooling degree.

Schooling degree N M M SE-ad M M SE-mo pvalue

X ± sd X ± sd

Illiterate 28 18.68 ± 4.59a 20.07 ± 5.28d 0.003

1-4 years 119 22.98 ± 3.47b 25.58 ± 3.48e 0.001

5-8 years 85 23.98 ± 3.39b 26.65 ± 2.67e 0.001

Table 5. M ean scores of calculation item according to schooling.

Schooling M M SE-ad M M SE-mo p value*

degrees (Wilcoxon)

Illiterate X ± dp 1.5 ± 1.8a 2.6 ± 2.4c 0.011

M d (mini-max) 0.5 (0-5) 4.0 (0-5)

1-4 years X ± dp 2.1 ± 1.7ab 4.3 ± 1.5d 0.001

M d (mini-max) 2.0 (0-5) 5.0 (0-5)

5-8 years X ± dp 2.6 ± 1.7b 4.8 ± 0.7d 0.001

` M d (mini-max) 2.0 (0-5) 5.0 (0-5)

Comparisons among schooling: H= 8.05 (p= 0.018) H= 72.74 (p< 0.001)

Kruskal-Wallis test. M ultiple comparisons betw een schooling degrees (Dunn test): Values sharing different over script letter are significant (p < 0,05).

DISCUSSION

The very low (poor) or low (fair) agreements according to Kappa coefficients15verified betw een the scores of M M SE-ad

and M M SE-mo in the copy and calculation items, here report-ed, indicates that the test modification induced changes in the ability of the individuals to solve the proposed tasks. However, the higher agreement for illiterate group compared to school-ing instructed (both in Kappa coefficient and in observed per-cent agreement) suggest that the influence of the test modifi-cation is lesser in illiterate individuals. In addition, the com-parisons between mean values of the total score obtained in the two test versions reveal that these changes correspond to an improved performance w hen the individuals are submit-ted to M M SE-mo. Of course, the total M M SE-mo score refle-ted the alterations introduced in the copy and calculation items, because the other items were not modified. Indeed, the higher proportion of subjects correctly designing the triangles, as well their better performance in calculus in M M SE-mo sup-ports this point. Since this improvement was observed in every schooling degree, including in illiterate individuals, it is likely the highest M M SE-mo copy achievement to be associated w ith basic know ledge of culture features in w hich they have lived.

In Northeastern Brazil some of these features, such as

rec-ognizing a triangle, is easier than recrec-ognizing a pentagon. In their daily activity the people routinely deal with triangle shapes (popular musical instruments, objects for playing behavior), but not with pentagon shapes16.This recognition might be even more

difficult when the overlapping design of the figures in the test is required. So the cultural background acquired out the school can improve their capacity to solve the problem, because a familiar figure is included in MMSE-mo but no in MMSE-ad.These findings indicate that informal knwoledge about geometric shape is an important way to face the test challenge. On the other hand, the association of calculation and praxia with edu-cation suggest that the improved performance of the highest schooling groups in both test versions is accounted for by edu-cation-dependent skills.

There is mounting evidence that education has an effect on testing cognitive state in different culture groups5,8-12. So

in our population- based sample, education and culture back-ground could also influence responses to the calculation ques-tion w hen changing subtracting serial sevens to subtracting serial one. Further our data show that differences observed betw een M M SE-ad and M M SE-mo are related not only to the test structure or to the schooling degree w orking as indepen-dent factors (indicated by their main effects), but also to an active association of them (indicated by the interaction effect). Therefore w e can admit these factors influencing each other

Table 4. Distribution of individuals according to correct copy scores.

Schooling M M SE-ad M M SE-mo χ2 p value

degree N n % N % Yates*

Illiterate 28 4 14.2 11 39.2 3.278 0.034

1-4 years 119 30 25.2 76 63.8 35.99 < 0.001

5-8 years 85 31 36.4 64 75.3 25.98 < 0.001

* *χ2

2df = 6.095 * *χ 2

2df= 12.178

by inducing a better performance in M M SE-mo. In conclusion, the present data suggest that social and psychological factors contribute substantially to cognitive test scores and empha-size the importance of detailed assessment procedures for apli-cation of M M SE-ad and M M SE-mo tests as clinical instru-ments. In this way an individual belonging to a non afluent population could be adequately assessed in its insight capac-ity w ithout damaging its abilcapac-ity at solving the problems pre-sented in the test.

Therefore the M M SE new version here developed sup-ports the view that the criterious use of both test versions (apply-ing them accord(apply-ing to social and educational groups) could prevent false-positive and false-negative evaluations.

REFERENCES

1. Dick JPR, Guiloff RJ, Stewart A, et. al. Mini-mental state examination in neurological patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psycchiatry 1984;47:496-499. 2. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiat Res 1975;12:189-98.

3. Magaziner J, Bassett SS, Hebel JR. Predicting performance on the mini-mental state examination. J Am Geriatr Soc 1987;35:996-1000. 4. Williamson J, Stokoe IH, Gray S, et al. Old people at home: their

unre-ported needs. Lancet 1964;1117-1120.

5. Anthony JC, LeResche L, Niaz U, VonKorff MR, Fosltein MF. Limits of the “mini-mental state” as a screening test for dementia and delirium among hospital patients. Psychol Med 1982;12:397-408.

6. Knights EB, Folstein MF. Unsuspected emotional and cognitive distur-bance in medical patients. Ann Intern Med1977;87:723-724. 7. De Paulo JR, Folstein MF. Psychiatric disturbances in neurological

patients: detection, recognition, and hospital course. Ann Neurol 1978;4:225-228.

8. Uhlmann RF, Larson EBL. Effect of education on the mini-mental state examination as a screening test for dementia. J Am Geriatr Assoc 1991;39:876-880.

9. Fillenbaum GG, Hughes DC, Heyman A, et al. Relationship of healht and demographic caracteristics to mini-mental state examination score among community residents. Psychol Med 1988;18:719.

10. Escobar JI, Burnam A, Karno M, et al. Use of the mini-mental state exam-ination (MMSE) in a community population of mixed ethnicity. J Nerv Ment Dis 1986;174:607-614.

11. Tombaugh TN, McIntyre NJ. The mini-mental state examination: a comprehensive review. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992;40:922-935.

12. Fratiglioni L, JormAF, Grut M, et al. Predicting dementia from the mini-mental state examination in an elderly population: the role of edu-cation. J Clin Epidmiol 1993;46:281-287.

13. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Anuário estatístico do Brasil - contagem. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE: 1997 Tabela 2.98,p.2-165. 14. Bertolucci PHF, Brucki SMD, Campacci SR, et al. O mini-exame do

esta-do mental em uma população geral: Impacto da escolaridade. Arq Neuro-Psiquiatr 1994;52:1-7.

15. Altman DG. Practical statistic for medical research. London:Chapman & Hall, 1991:611.