---UNIVERSIDADE NOVA DE LISBOA F aculdade de Economia

16r~

"A l-iODEL OF THE SOURCES OF BENEFITS IN SRTATEGY"

Jorge Vasconcellos e S§ Working Paper NQ 95/6

/

,/

UNIVERSIDADE NOVA DE LISBOA Faculdade de Economia

Travessa Estevao Pinto

1100 LISBOA Setembro, 1988

..

.

..

. •.

....A MODEL OF THE SOURCES OF BEtlEFITS rtl STRATEGY

.' "" "'" • /'/ ... ~.- O W ' .::4 I .

,

-l I : --~.-_." ..

. l'

AJ3.STRACT

...

" TIlis paper presents a model" \y1dcfi -interprets organizafiohal behaT.jior in terms of iiv€- ~;ources of strategic benefits: environrr!ent; attractiveness (profits.. sales,

.

.

gro~lth); size; tilne; diversity; and relevant strengths,These 'five sources of strategic

benefit are used by organizations in order to pursue botli effectiveness and efficiency.

TIle utility of the model pre~nted in this articl~ lies in. its ('.ap~city to interpret

organizational phenome~o such ~smergers, jOJnt ~1ent~'res and 1i~ensing;.and in its

ability to put different types of organizational behavior into perspective.. including

specialization, opportunity .. innovation and synergy. Based on the m()<iel it is also possible to ~e 'Nhere some major. "opportunIties for tuture research .He.

,

..

. " ' I . .'" \ \ j ..-

I - lI'.:JTRODUCTION

I ' •

. .

Society \\1elfare can be divided fn.to tv'lO basi:: components: quality of life and

standard of life.

Quality of ~ife is a generic term :~Nhich includes .stich desirable variables as ireeUOITl froln pollution in the environnlelnt.. 10\\1 ~rJlne rate.. bigl1life €'k'P€·ctallcy and

good Volorking conditions.Standard of life regards the per capit3. disposable incorlle for

~~ing or cons!J.rnpti'!)~.· (Sarnuelson, 1986; Baumol ap.d Blinder, 1988).

Organizations can contribute to the quality of life by tnlproving the quality of

~'forking conditions. H~.re, techniques and concepts such as Job enrichment.. the styl~

of leader~hip, organizational de"lelopmen~ and decentralization can play an in1portant

role. Organizations can also use ethical con~~aints in tile nlark?til)gmetl1ods ~l11icll

they use to address customers and. in managing the organizational impact on the . environment. Organizations wlli.ch manage their impacts on the various sta.1~eholders

\ (employees .. customers, general public, etc) beyond mere·pro~it:SeetJng are known.as

.\ /:

. ·socially responsible" (Schir~r!l, 1958). /" .

.~.. \"

.A standard ()f life requires high levels .of productivity (Kendric!f, 1959). That is, . that organizations be capable of offering high value t.otal output to the marketplace, \ wisely using the' resources at their disposition: raw materials, energy rlloney

personnel and rnachinery (Shepherd .. 1979).

That is

n

I Pi Qi i= 1n=---

" n .I. Pj Qj )=1Where

-~-- n

=

Productivity Level - i = OUtput . ~ j = Imput.

.. . . "

. - Qi= Quantity

oi

outputi. .

.

- Pi = Cost for ?le firnl of input j

'

.

.

, - Qj =Quantity of ~utput j used in the producti?n process.

In order to ctttain high lev'els of tjroduc~i\TitYI organizations tllust be" effective

and effi,:ient. Effective organizati~tls are able first to identify and then enter into environrnents v·lhich are highly attractive in terms

ot

porfit margin .. mar1::.et size and growtll. Effectiveness allov·ls for large values in the numerator of the productivity'ratio a.l)ove (Pp,..Vi). On the contrary, efficiency is

.the

ability to create high value offers .(PP~i) u~;ing the resources at ones disposal -wisely.- (Hannan at)d Freeman, (l 977). Efficiency is related to the ability to.. create a competitive advantage mthin a given environrnent, as shall be discussed below.

\ \ I I -

Organlzations

pilfsuitof

Effecti'r'l"eness.

In .order to be eff~ctiv~, organizations must opt for attractive Irfch task environnlents ~Nhit:h rate highly in terrns of sales, gro"i/tlth and profit rnargins C,A.liken

and Hage, 196a).

.

. The environment comprises aU of ttl€' world agents and' conditions '\Alhich 'hav~

some effect on the outcome of an organization (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1(78). ¥lithin the enT.,1ironment, one can distinguish bE:t'\Aleen

thCt.3€' factors which -'directly influence,' the organization and those ""'lhich exert their influence in an indirect fashion. Factors which have a direct influence are called specific (Hall et aI, 1968), relevant (Dill, 1958).. or task (Thompson, 1967) environment. Factors \I>..'11ich

have an indirect influence are refered to as the general environment (Hall" 1968). OUr concern here is primarily '!>lith tile task (direct)·environment, since tilis is composed of exte'rnal elernents \A,hleh directly influence an organization (Miles and Snow, 197ts).

Attractive task environrnents can be achieved ill- two basic ways: environr.nent positioning and environn1ent enactJnent (Weick, 1969).

Sometimes 9rganizc..tions POSITION themselves by entry into in.dustries and industries s~ments ~hich are ricb" that is.. attractive in terms of sales.. profits and

grov.lt.h. Frequent1;i products and services in tile early s~.ge? of tlleir "life cycle ha\-Te f '

tht~SO ctlaracteri::Ji(;s (Levitt" 1965).

• I • t l

A't otl1er' tirIl€:s .. by creating a nev'l product or service" organizations ENP~CT ~ significant part of the environrnent (the distributors.. the supplfers, tile technology used" etc.). O~le spealcs then of environlnent enactment (Galbroith.. 1967" Child.. 1972...

Abet:na.tllv# .and Utterback ,1978) .

In the first ease, the organization is a folIo·v/er.

In

the second ease, it is an inn()vator (Nystrol11, 1972). goth organization p.:>sitioning and organization innov-ation seel{ environrnent. high in profits" sales and gro'rlth potential--see figure one.IInsert Figure. One ,Ati~ut Her~1.

I II - Organizations Pursuit of Efficiency

"

Hav~ng ident~fied the task environlnents in -which >lrey "'" ",,'/ish to position

,'themselves" organizations ~tim for efficiency. /

• I

For. such a purpose.. organizations may exploit two types of resources. We sball

.. . \ .

call tl).e first type "\1ALUE OF RESOURCES", and the second type "NATURE OF

RESOURCES".

I I 1.1 -Value of Resouces

Organizational resources are g~nera1ized mea~s, or facilities" that are potentially controll~tble by social organizations and tllat ar(~ potentially usable

-hOV-le"Ver indirectly in relationships betv·leen tlle organization and its environrilent. (Yuchtrnan and Seashore, 1967).

A given resource is more or less valuable for an organization depe~ding upon

hOll'l that.. resource rates cOlnpared to competition in terms of quality (being a

strength" or not) - stevenson, 1976 - and ,...,hether that resource is or is not equal to an environmental key success factor. Key "success factors are" those resources

... -...

(distribution.. image.. service" etc.) \Vhich performance is esp€<ially dependent upon (Andre"-NS.. 1978.. Christensen.. 1986). They change from one task environment to another. (Rocl~artl 19791 Jenster" 1 9(7). .

Therefore} W'he~ an organization has a strength in a resource \'l11ich is also a key success facto( 'one says that that resoufceis of high value or that it is a

relevant

"

..

'"

, . . .

strengtll. P. non -'relevant strength ~t!ould be .a. reso~\rce v.,hich the organization bas a

strengtll in \A,:11€·n conlpar~d to' corflpetitil~n# but ¥lhich is not a key success factor.

(Vasconcell()s.. 19&3) -" see figure one.

..

111.2 - Nature of Resources

..

According to their nature.. resources qtn be divideq into: .

.

.Private resources - TY\mer~ the use of a resource by one person or

departnlent l.Alill necessarily decrease the amount of that resource available ~ another person or department. _- E}:arnples are machinery .. warehouses.. a salesforce .. plants.. a

market research specialist .. etc. - Leontiades .. 1936.

Half public resources - \'Vhere the use of the resource by one departrnent "Yill jmply spin-offs" or e~rnalities to some

" ~

oUler departtuent. P ...n e~pie is irn.age. The ilrlage of one /

divi~on may have a positive 01 negative impact on the sales

Of, anotller divisi0I?-. Another e)mrople is R&D ·'v.Jere a given project can ·be useful to more than., one division.

T~hnological externalities among divisions

can

occur in theareas of manufact(J.fillg.. engineering.. logistics and procurement. -Teece" 1982.

Public resources - ¥!here the resource . can b~ used by one department ~litho:ut effecting the a.mount available to be used by other departments. Examples are brandnames,

copyrights~ trademarks.. institutional advertising ('A1J1icll oonefits several organizational divisions at a time) et.c.

-Singh and lviontgomery.. 1987.

Organizational resources can therefore be divided according to their nature as privat.e.. half-pllbHc or pul')lic. Private rec..,ources are typically the employeefs time and physic.al goods such as machinery.. trucks and buildings, Half ··Public resources are the knovvledge and experience of the organization's management and employees .. and the

image of the division of tl:~e organization. Public goods are pro~rty rights (p.atents..

Pri'late~ half-public and public resou~-~e~ have- distinct characteristics. Public.

. res()urces are intangible. Due to their int:ingible nature.. pubiic r~~sources can gene-rate

Inargina.1 benefits \'·lithout any increase in cost ·(e.g, nev: div'isions benefitting from patents and ·n'ade rnarks of the- organizf1.tion).

Half public resources can generat.e externalities 'tNllere one division benefits

fronl the tnov-l-hov".. irnage" etc of another di'!ision (Viells, i9a4, Lorangel !vlort()n and

GOSl13.11 19(6). Private resources are t.angible in nature and. do not' possess this

property. HO'rlever.. tl1ey do have several properties vmich also imply tllat the.

average cost do~s not move proportionally to the scale of the use of the resource.

There are seven such properties: (1) the law of two thirds; (2) discontinuities; (3)

lea~ning; (4) heterogeneity; (5) the law of great num~rs; (6) pov-rer and (7)

interiority versus exwriority.

(l)- - THE LPI. ¥l OF T'NO THIRDS states that.. vvithin certain Hnlits, a.s the area of

, a building, -':Narehouse etc. dout)les.. its volume increases threefold·. Since the output is

proportional to volume and the investment to the surface area a benefit occurs here.

- , -'

(Haldi and, VY'hitcomb, 1967, Lau and TOnltl.ra" 1(72). Tllis la\\1. plso applies to certain

.\ 'types of rnachinery' usee in process industries such as steel,/p~troleum refining.. iron ore reduction, chenlical con~er~ion and generation -of· steam (Levin.. 1977; Scherer"

' . - \

1980)., .

. (2) - DISCONTINUITIES arise in physical resources. such as machinery and in

'. \ personnel (Shepherd, 1979). It follo'Vv"S that freq~ently only after a certain lev~l ofsize is it economica!.1y compensatory 'to mechanize some tasl~s or to hire some specialists (in au.diting.. market research .. t.axation" etc). Moreover" larger organizations can use

these resources (ph?Sic.al and personnel) at'afu11er capac.l~1 then slT1aller ones.

(3) - LEP.RNING is a char.acteristic of people. Learning can pertain to the: factory '\o'·lorkers (learning curve - Hisschmann" 1964); to· managers and supervisors

of the nlanufacturlng department (BeG" 1960) ; to engineers of the research

departtnent (process innovation) - Hed<lley., 1976; or to the marketing staff (bet:ter

knoVlledge of hov'l to adapt the product to customer news) -Henderson, 1980.

(4) - Besides learning., people possess anotller '!otery important characteristic.

They are HETEROGENEOUS, rneanin& they are not equally apt to perform all types of tasks. They Can perform son"'!€' tasl{s better than other_They have strengths and

w.ealg1esse~ (Teee?,.. 1<)80). Thlscharacteristics (wbich is also a pro~rty of pl.l.ysico.1 '

, .

",

strength,=; e~n~~t. Ori U?e contra.ry.. in sfnaller organizations, 1N,?r1::*?fs tend to perfor!n a larg·s· nurnber of ta:::1::s regardl~~~s c{ ~l"here tileir stlengttJs He (Robinson, 1950).

.. • 1: • ..

the fact tllat resources are heterogeneous: ca!m also be exploited ~y

organiza.tions 'Nllich have built diversity into their operations~. those which have distinct. divisions operating in distinct tasl~ enV1rO!l1nents. For instance.. diversified orgctnizations. can engage in 11l.ultidiscipliniary R&D projects 'Nhich a specialized organ!zaUoll cannot.. (for lack of teruns ·'I.litll

tile

various reqtured skills). Still.. other· tirnes due to the heterogen€:ity among products, it fllay occur that the clients see theproducts not as products "per se" but as parts of' a greater \v11ole. (equifinality). Indeed.. in SOtlle situationsJor Urne and cOlnpatibi!i~y rea.sons.. the clients prefer to'

make a single purchase of a greater 'N'hole instead of seT/era! jrldividual purchases for each indi'lidual part. _

For exarnple.. in the autornobile and grocery' products industries.. retailers prefer to deal T'Nith suppliers \1>1110 offer a broader product line. Consequently .. this

- ly~ of supplier has a greater access to distribution channels (Porter .. 1880). The sa!ne

. / ""

applies to ·several situations 'V·ll1ere the final custolner perceives the product 11E? or she

\ . . /

purcha.£.es in broaci terms. Ttlis has induced organizations t6 add new itefJ1S to tlleir product line so t11at the t(f~l·o!fering is as broad as the customer's perception of the

product. Tllis is the reason, 'Nhy auditing firms have diversifi~d into taxation,

nlan3.g~!nent. consulting and. lllanagement re<;ruiting. The client s~es him/lH~rse1f as

buying specialized profeSSional services and.not taxation, audi~ng.. etc, per s(~ - IvHles

..

and' Snow" 19aO. .

Another i1l1portant consequence.

of

tbe existence of heterogeneity among \reSOl1fCes.. is ttlat h:eterogeneity can be used to decrease organizational ri.sl::. By pltllingdistinct products· under the same Qrganizational umbrella (v.lith distinct tasl;.

environlnents).. the variance of sales (and consequently of profits) and the level of critical contingencies faced by an organization can decrease.

(5) - Anotller way of achieving lo\AJ' risk is through THE LA¥l OF LARGE NUMBERS, From this law b~~~nefits can fc:llo",., in the areas of inventory, personnel .. finance and R&D.

As the numoor of buy(~rs increases their variance in terms of idiosyncraci€:'S

and special characteristics dir11inishes. tower variance among buyers rnean~ lovler

''lariance of sales. From here fo1101l>1 several consequences, First .. the probabilit.,,, of stockout is lovy"er/.implying that costs of hc,lding inventory v.ri1l increase' less than

".--"'----,~-~-..

. , .

proportionallY'

to

sales (~NhiUn ai1d Peston, 1 g54) .. Larger 'organizations Vvtill therefor:ereap a benefit here.

Second.. the lov.,.ter variance of :ales associated 'Nitll great nUfIlbers can also imply lo¥N:r personnel costs .~"'hen e!npl()y~es are transferr·~d from one division

.to

another, instead of being hired 'and fired as. each division'$. sales go up and do""n . ' (lvlecl1Hn... 1Y()O). Third, 10t;,\l'er capital costs tnay occur since risk averse investorsdelnand lOTv\1er int.erest fro1'11 l(~ss risley organizations (~~Tilli::Hnson, 1975.. Chatt.erjee..

19(6). Fourth.. benefits can arise in R8{D 'vvtiere the failure ahq 'success of projects 'rlill

~nd t.o Qffset each otl1er.. enabling.t1vt organization to engage in higher risk projects .... Terry.. 19~) 1; Pitts, and SnoT'{\T.. 1985. .

(6) - F... llother important characteristic of resources is that tl1ey can be a source ofPO'YVER ~lvllen as~illbled in great nurnoors.. and in sonle ins1:at~ces.. \-\There Ute organization bas built di\Tersity into its operations.(Shepherd, 1970) Large organizations can influence their political environment (lower probability of

ban}:rupt~T -Dooley.. 1969) and their economic environlnent to a greater extent}

. / ~

pushing the final product strongly into the lilarket and clla;rg'i11g higher prices for it

(Cooper.. '1979). La'rger orgarlizatjons can also obtain lovler ippu.t prices due t.(> buying pO'Ner and the feasibility,

of

shopping arqund 'rlhen large quantities are In'tolved.DiT'IT€'t:'sified organizati()ns can also sometimes impose reciprocal pur~hase 'Vvhere one division of the organizatioll l)~lYS from a given supplier if and only if tlH? supplier buys'fron1 a.not.her division of tile sarne organization (Singh ~nd 1·...1ontgornery.. 19(7).

(7) - Finally .. \-~Tl1en tIle resources are INTERIOR (they belong to an organization,

as opposed to being exterior to the organization). ;.avings can occur due to 'lov-ler transport3.tion an~ distribution costs} 1ov.,er coordination cost.<=>., S:::1.v.:ngs ~n energy.. etc .

. T11€-se are benefits usually asso(:iated \\litll vertical} not horizontal diver~jty (vertical . integration) - Teece... 1981; Buzzell.. 1983; Harrigan.. 1985.

The interiorization of resou.rces also increases the ~pacity of part of the

organization t.o ulld(~rstand the needs of other parts. This understanding and tolerance is important both \vhen physical resources (raw materials., etc) are exchanged arnong

difierent parts of organization (vertical integration) and Ty.~en financial resources are

exchanged..

Indeed) \hlhen.cross-subsidizaUon among divisions occurs.the receivinG givision

has

greater fr~€'dom in financing long term market share gro\vth as compared to a situation \-v-here funds are supp1i~d byexternal sot.u·ces.

This means that internal financing enabl(~s tl1e organization tobe

less restrainoo by short ~rrn conSiderationsin the pursuit of its long run \"l'€'lf~t~e (Pitts a~(l Sno\.{. ·198~). Fi·gure t~o sUflui1arize·s

section I I I -2.

.

IV - STR.O\TEGIES FOR ACHIE~.JING EFFICIENCY

J"'o obutin efficiency (a large ratio between' the value of outputs and the value

of inputst organizations 'pursue tT'Io,to broad categories

of

strategy:.

- TO INCRE~';SE THE \1F.LLUE Of THEIR RESOURCES e.g. by matching organization

strengths to the l:ey success factors and long range programming - i\nsoff..

- " ; .

. 1967; Andrews .. 1978; Christensen et a1 1986.

- TO EXPLOIT THE, INTRINSIC CH.';RP.~CTERISTICS associat.€'..d mth the nature of the resources, narnely; the intangibility of the public resources; tile externalities of the half public resources;.and the charag~istlCs of the private

.\ , resources: the t

T

v'!0 thirds rule .. discontinuities.. learni,pg, heterogen~it~{.. laT,,A,r of great nurnbers~ pO~\le:r ~ttJ.d interiority (Rll1nel... 1977; Porter 1985; Singh and

.MontgOlTlery.. 1987). \

'.

...

.'YVa shall next analyze the implications of each ~f these t~,'\lO main types of strategies.

IV-1 - p ...chleving Efficiency by InCf(\asing the Value of ttle Resourc(tS

~ ..

.

As 'VVaS fIlentionoo in .figure one, two basic avenues are available to organizations to increase the value of their resou~rces: TO .MATCH STRENGTHS yVITH KEY SUCCESS FP.~CTORS and LONG RANGE PROGRMvll'v1ING.

IV-1.1 - Matchin?- Stren~?ths 'vlith Key SucceS2 Factors

Since 'tile value of 3. r(~sourCi? depends on its b€ing a relevant strengtll.. tllat is.. M'ing of superior quality to the competitions' and matching th€, environmenl.:.t1

ke"

success factors; and since cornpetition and key success factors change [ronl one tasl~environnlent

to (Rocl:art) 1979; Yasconc€'l1os, 193&); by cllariging frorn one w.sk ..'other 'No,rds, ·in order to increase the 'value of th~ir resources and consequ€'ntl}' achieve great.er levels of efficienc;l" organizations should' sel9ct enviror)n1ents v.711t:~rJ:)

tlle or£tanlzational ::.tr~nQths Inatch the 1(€''';l success factJ)rs. This· is the model first enunciated in the si}...iies at Harvard by E. P. Learned et a1 ~l9(5).

. Flo neces::;ary consequence of organizations rnatching their strengths to t.ey . success factors .. (changing irrelev·ant. str(~ngtl1s into l!elevant strengtlls), is that v·lllen

they do S0" they also cha.nge tl1eir rel(;?vant ~Ne3j{neSSes into irr~:-levant 'v"E~al{l1eSSeS (in

, the ne-.:,\! environnlent their 'Nealcnesses are not critical success factors).

. .

This r.neans that erclironlnent selection allo"y·.Js organizations to lnO'le frofn cell

P,.' to cell loA,. I I and frOlT! cell I.~iv to cell A"" in f4gure 3plo. These movements are

represented by arro,lVs n1..unber one and tV·lO in n~ure 3A:

IV·. 1.2 . Long: Range Programming

An~ther avel~ue open to 'organizations to increase tile ~~l1.re of their resour(:~:s

\ ,'is tllE~ developrf1fJnt of prograrl1s, that is.. long range activities/~!hich vlill i1rlprove their

vleak.nesses and change th'$'fn I into strengths (o.g. developing a better sales force"

. irnpro.ving the diE;tribution ;'yskm reorganizing l the R&D departme~t.. etc.)-' Steiner .. 1985; Anthony and Dearden .. 1988.

. These acti'':lities typically take considerable time in achieving U~eir aims and require signifk:ant amounts of

the

organization·s budget and Inanagernent's tinle.Arrow n2 3 in figure 3A illustrat.es the ailn of lo!'g ran!2'e planning": to change .,rele\lant v"eaknes~es into relevant strengths.

IV.1.3. Efficiency Through High Value of Resources

Be

it t.l1rough matching strengths ¥Villi key success factors or througb long range progralnrlling.. the efficient organization is the one wb.ich has relevant strengths and irrelevant'VvYealmesses (Salter and Weinhold.. 1979). It has few .. if any.. relevantvleaknesses (¥l(~al{nesses in resources \\Jhich are critical success factors) and few, if any.. irrelevant strengt.hs, since th~~ existence of irrelevant strengtlls mea!!s that . n10ney.. timE~ and effort \AlaS~h"'3.sted in irl1proving resourCE'S 'Nl1ich are not critical for

performance in the organization's task environrnent. The existance of irrelevant

. .

high l~vels of organizational 0f~iciency, sin(:e tile organization h~.s not searched for an environrnent ~/"here its strengtlls Dlat.c:h the critical succe~s factors (Falley and Noreyanall.. 1906).

.

. Figures 3B , 3C and 3D show q high .efficiency mediurn efficiency and a low efficiency organization.

. In figu.re 3:E> ti1€:' organization has only t'l;NO types of resource. Relevant

strengths and irrelt2.T,lant TY\leal:nesses. This efficiency optimum situation .. ,,·,:ras achiev.z~d

by the ~rganization's lnatching of its ~;tre!lgtlls to l::.ey success factors or land long

range pf9grarnrning. In figu.re 3C the organization is not in an efficiency optirnal situation since it has both relevant 1Nea1::.ness~s and irrelevant strengtlls. Because S01Tle of its resources ar~\ in c€'l1 C', the organization experiences \\:reaknesses in critical areas. Because it bas strengtils in noncritic3:1 areas (cell CPl).. either the investrl1ent of titTle and~ frl0tlBY in these areas can be decreased or alternatively, tile organization . could enter into a lle~l environment Tv'lilere these strengths are sour~es of increased 'efficiency (they nlatch the key success factors) :'

/

,~

• .. /.t'

Figure 3D S110¥lS the V'olorst of all possible scenar ivs v-l11ere an organization has only tv,,? types of resource~: .rel~~Yant V"e3.1::~esses (D') apd ifrelevant strengths (DP1).

In re~1.lity.. rnost organizati()n~ '¥lill not be at either extrerfle of tl!e continuUfl1 of

irnproved efficiency but in~etween the situations represented by tables 3B and 3D. '.

IV.2. ACHIEVING HFFICIlItlCY BY EXPLOITIliG THE NATlJRE ArID RELATED CHARACTERISTICS OF THE RESOURCES

Besides fOCtlsing on improving thJ~ value of their resources, another tnain 'strategy open to organizations in order to achieve efficiency is TO EXPLOIT THE

INTHINSIC CHft.JU\CTERISTICS OF RESOURCES (their discontinuities, the lavv of 2/3,

etc.).

For such a purpose, organizations rD:anage three of their dimensions: their SIZE..

DIVERSITY AND TI'JE.

By incr(~asing th~ir SIZE (sales per year, market share), organizations are able

to exploit the fact til-at tileir public resources (in1age of the firm as a ",,1;016'.. i2atents..

brand t~alnes, etc) are intangible and therefore are invariable to tile l!evel of the organizations operations. That lSI their ~arginal cost is zero.

"""

---.-_._,,-_

.•.-.._--_._

...- . .

Larger size also u enables ofQ'anizatlons to v profit Irorn . several characteristic.;s of privat€, resources: their discontinuities; the la'....' ~f 2/3 in '~13_r€'hou~;es and bUi1(Hngs; the ability of people to learn; the b?v'l;H~fiti of specializing.. their resources (machin~rYI personnel.. etc) in 'Ntlat they

do

best (\Alhere tlleir .strengths are); anci the pO"vver andlo,,,,er risk 'A1llich may come fronl assembling high volurne resources.- Singh and 1'.,fontgomerYI 19~7.

P4.S TIlvlE goes by, erIlployees (in fnanufacturing engineering) J rI1~1.rl{,eting.. etc) learn, thereby increa~;ing the efficiency level of -the organization. FJ.l1 organiza.tion

. .

cannot contl-ol the passage of tilne. It can.. hov·levefl position itself ',qith low di~?er::;ity

alnong its product lin~s and increa~;~ its size per _'luiit of thne (tneasured by ~;al~s or market. share). By narrov\ling t.he fie1d of its operations (less diversity) and by

increasing til€' amountof learning per unit of time (higher size

t

an organizat.ion canaffect its 9verall learning rate - Hirschn1ann.. 1964; BeG, 1968.

P...s a consequence, the efficie.ncy lev~l of its wort.ers (learning curve

J,

.of,1l1anagers and supervisors (in managing the department alld in the use of

- /

equipl11ent).. of engineers (in tlle Rc-cD departnlent) and of. rnarketers {in how to adapt

\ . .. .(

.

. \ the product to customer v"an~s), \\lill increase - Heddley, 197,6; Hend.ersofil 19aO.

- <... ,

.Altll0ugh high levels of \DIVERSITY in the product. Une of an organization decreases the capabHit~T of the organization to. collect size and t.irrle (experiencE?)

benefits.. diversity canl in its turn, exploit some resource characteristi(:s and therefore bring son"!€' benefits. Tlle fact that half public resources generate externalities can rnake one divisi.on l)enefit from tile activities and resources of another division (its

irnage, its technical kno\\T-how.. its knowledge of the psychology of the Client.. etc.)

piversity rnay also. decrease the oVf'rall risk level exp€'ri~nce by the organization in

lernls of variance of sales and profits) or in terms of critical contingencies tho organization faces.. if distinct products (with disti,nct tasl:;. environnlents) are pulled together under the sam(~ organizational urnbrella - Wi11ifu~son.. 1979; Teeco.. 19&2; Thereforel size~ time and diversity are three dimensions t.hat organization's manage to achieve high levels of efficiency.

Four points are worth noting here:

A - -Not all dirnensions (S1ZO. time/exper:ience and diversity) exPloit tJle resource characteristics equally ,,-'lell (learning, increase the organization's

po~..,er.. decrease fist, etc). Somt') dimensions are better suited to exploit

.. # . ..

Size can be used by ()rganizatiqns ·to profit fr?rn discontinuties lJut 'n()t

I I

fronl externalitit&s. Diversit.y can e}spl"it" ext.ernalities but not learning. . Tirnele~~}Jerience can benefit from tile resources ability to learn but: not fronl tne- 1a':", of g'reat fllunbers.. and. so on "-:-Hedd1ey.. 1<)76, Sherllerd,

1979;

B - The t.yp~ of resources required to manufacture 3.' product Of offer 3. service

differs fron1 one t:lsl~. environment to another. In sorne tasl( environrnents.. the use of machinery is more (~;ttensive than. in others. Distribution

organizations use rnore ~ '¥larehouses than service organizations. Some

industries are more labor intensive .. others are 1e~~ labor intensive.

fJoreover., due to differences in technology .. the rrlacl1iriery -required to

manufacture one type of product. may have more discontinuities than the 1l1achinery used to lY1anufacture<i an6ther type of product. The slop~~ "(in

ab~:oluoo tertT1s) of the learning curve. can be greatJ&~

of

srnall~?r, and so on.. . /"

.\ , - C3.ff110n antI Langeard., 1980.

I

j

' ..~ \

... \

C - The benefits ¥lhich. can be extracted' from increasing in size.. time and diversity are SUbject to the 1aVtl of dirninishirig returns, This means that.,

'. after a certain level -of e}.-perience.. the- learning curve flattens. P.Jter a

certain level of size.. the s~cta1izatlon benefits decrease. After a certain level of diversity., e}:ternalities b~ome rarer since divisional image and

knOv.l-h.o~~l becornes less transferable to other .diviSions., and so on

(RobinSon.. 1954; Bain.. 1956; Scl1er€:r., 1980) .

D - FinallyI very high levels of· size., diversity fUld experiencefUme can bring not only decreasing returns but also negative returns. The reasons are

four: organizational cornpl1xity.. organizational aging lo\h.1er proxi.ulity of

the resources.and lO'rler motivation.

Very high levels of size or land diversity malce organizations tomW~~ botl) . in t-ernls of internal politidng and in terms of int:;rrelations among the tasks to be perfornled. From cornplexity ernerge two consequences: the need for fll0re sopllistlcauJd m.anagerrlent syste~~)S (information systerns}

control· s1steras, structure, etc.); and problerns \vith d·~cision m::1.l:ing.

• I

B(;>cause de(:i~jon rnat0fs are farth<:.~r aT,Nay froril the tasl:~ environn1t:nt,

.

' dt:-cision Inhking becot:fles slov·Ter and of }?Oorer quali.t;i ('-'Villiamson" 1967;Honnan and Freernan" 1977).

Secondj over tin1e" organizations age, T,,'lllich decreases the capacity of

organizations to adapt to n(~\\T conditi()lls and ificr~ases the organization's tendency to·

d~:velop stricter routi~H~S and be rnore attaclied to. hierarchical relations (Blair.. 1972; ~A..Jbernathy and ',~layne} 1974). As a consequence., efficiency suffers.

. .

Organizations feed upon the environrnent to obtain tl?-e resources (personnel,

ra"" rnaterials., etc.) tlley need. P... fter a certain lever of organizational size ... the

capacity.of the neighboring environment to supply th~ organization ~Nith resources is

eyjlaustad.. requiring the organization to go farther aV·!aY to obtain elnployees, fav·!

l11at.erials etc. T11is increases transportation costs and the price (~r13.ge.. etc.) tllat ttl?)}"'

, rnust pay for thos€' resources,.' As a consequence, large SiZ~can haver a negative

\ impact on the 12foxirnitv ()f the sources of resources and U1E;refore.. increas~ the (:ost

\ I'

of obtainning tl1em.(Schere~... et~. 1975). /'

. . . , . ' \ \ .

.Finally., there is ernpirtcal evidence .that p(-?ople are less mo!ivated 111 larger

'~rganizations. .. than in smaller ones. Since tile t.11reat of bankruptcy is . 10\Aler and

people identify less '....Titll larger units than. with snla11er ones.- Porter and La~,·~ller..

1965.

E - The fact that

A - some dimensions (size.. diversity" tirne/experienc€:) are better suiteQ to

exploit sorne resources characteristics (discontinuities .. law of 2/3.. etc.)

Ulan others;

B - tlle type and characteristics of. resources ch~ froln one task environment to another;

C - the bE..~nefits vihich can be obtained by exploiting the resource charac1:$ristics are SUbject to the la'¥, of diminishj~tllrt}£ and

D - (after a certain level)" size.. diversity and tin1e/G~.:p~rience can - bring

implies that the optilnal ·positionhig.in ternlS o.f siz€~~ diversity and ~.irne·

I j •

for an organization to l:na:itirnize effi(:iency dep;3Jids upon the t3.sk

.

.

environment (s) it is in.

In other ""ords~ 'Amen trying to eii-ploit the nature and related characteristics of

i~"resourcesl any organization can be seen in the t11ree dirnensional axis ShOV,ffi in

figure four. The"optirnal position for an organization in ternlS ~f the tilree axes is

contingent upon tl).e t.as1{ environment.

. Iii sorne task environnlentsl it pays off to rate high on tile size axis; in others

(because discontinuities are slnall, etc) the optirnal position for an organization in

terlns of efficiency ~Nill be lower on the size axis. Some task environrnents have a

• 4 •

great potential f(>r generating externalities based on (e.g.) technical l=-no~/"ledge.Other

task environnlents are-lnore technologically specific. In the iOrlYH~rl it may payoff t:>

increase organizational diversitYI in the latt.er~ not. 'lV-hen experience benefits are

high" organizations tend t.olo1."ler diversit.y in their operatiop.s since diversity has a

negative effect on the possibility .of reaping eA--perience benefits.

..

"'"

.

.

/ .. \ In short" the organization \vhich first of all analyzes

Yle

characteristics of itstask environment (s); and. tp€'f,l opts for a certain level"'of size, eA"Perience and

diver~itYI will1naxilnize efficieli~y.

"'~ ...

V. - UTILITY OF THE oLtLBOVE PRESENTED ~·AODEL .

The n10del presented above can be t1.s(xi to relate different types of

organizational strat~gies and rese2':ch streams" as "'y\,T€'ll as to interpret the rationale

-lfof organizational phenomena su(:h as mergers" joint ventures" licensing} etc.

V.1 - P,. Frame~,Alork of Organizational ~trat-~gies

The model developed in this article perrnits us to distinguish three ~1.sic types

of strategies: (1) strategies \-"hich focus on effecti.veness; (2) strategies airrIing at

efficiency by increasing., the value of the resources; (3) strategies aiming at

efficiency by e~~loiting the resourc<...~s· characteristlcs.

Strategi0s focused 011 effectivene;3s can be of two types: environment

organization in- highly attractive environrnents, iIi. terms of sales voitune, sales

grOTyQt.tl and profit ma.rgin_

Efficiency'st.rategies seek

ro

obt3.in: high h:ve.ls· of efft<:jency and thereforecompetitive advantage for the organization. (Pfeffer and Satancik,

.

197a). They diffe"f,' .

hOv.l€-ver, on hOT"" tlley do it. Efficiency (.an. be obtainned .by €,xploiting resources characteristics (suell as tlleir intangibility; the la,,{ of 2/3, discontinuities).. tlirough S1Z$., diversity and titne/experience; or by incre~.sing the v;~lue of the resour(:E~s, that 'is-,to have, in the critical resources (key succ-ess factors), superiority over tl1e' competition. . This rneans having a better. sales forCEr, a bett.er distribution syst.eln,

.

more s()pl1istieat.ed and t.t'?chnologically up-to-date lnachinery, and so on.

Thereforel in spite of being of high value' (a relevant strength), a resow·ce can

be hnpossible to U50- in tern1S of size, tilne and diversity in obtaining greater

efficien~y. That is the case if it cannot generate externalities., if it has lovY' .

discontinuities.. almost no learning capability.. etc.. ConverselYI one can have a resource characterized by large discontinuities (for e1."ample) and therefore able of

generating great benefits when "tlle organi~ation increases its sjze: but which is not. a

" relevant strengthl ' either because it is not a key the succ~ss ~a~tor.,or becausf;.' it is not

of bt~tter quality than the. same, (esource of cor.apetitioli. , .;

. I " , ... ...

'Depending upo~ the organization's use of one or another type,'of strat.egy, it is

possible to divi·je ~t.heir behavior into four broad categories: INNOV..A.TIVE BEH?~V!OR

\ OPPORTUNISTIC BEH1\VIOR; SPECIALIZED BEHPJ:vioR; l\ND SYNERGISTIC BEHp..VIOR.

Both INNOVF;,.TIVE and OPPORTUNI STIC organizatIons focus on the environrnent as tll€'ir pritnary source of strategiC benefits. Th-ey differ t!ov,lever in the fact that _\ while innovative .of'ganizations enact - and tl1erefore to a certain extent creatJ~

. their 0\\111 task environrnent (s)(Child.. 1972)., opportunistic organizatioris are

followers 'vlhich seek to position themselves in highly attractive environments (in

terrns of rare of marlcet grov-Ttb and profit potential), OpportunIstic organizations are also called congloll1erate or holdings lvIiles and Snc:w (197 8) ~esignate(l bOtl1 innovative and opportuflistc organizations as ""Prospoctors".

SPECIALIZED organizations are organizations which opt for grovving in only one or insilnilar task E!nVirOnlnents in order to reap size and experience benefits: The selected environrne~t should also allOVl for a rnatch betvY'een its 1(ey success Jactors and tlH: organizaHon's strengths. Miles and Sno~..v· (197a) called this t>"7pe of organization -detell'jers".

SYl'fERGrSTIC' b?l1avior is th~ fourth .typ€' of behavior that. organizations .tnay

I '

foll'~'/>l. One speaks of synergy 'Hllen t¥lO divisions' operating in different industries

..

perforrn. differently under the sa~e organization than if they ·'Vv"ere independent businesses - Salter and ,Veinlloldl 1979; Hilland

ex'

Hoskissonl 19(7). Synergisti~ organizations base their behavior to a large exte~t on the diversity dirnensiofl. Tl1ey . use'~his dinlensi()f1 tD l1arvest technological externaliUes} image externalities, etc. PI.S long as tIle industries ~vllich the organiz3:ti'~n is .in are siIllilar, it ~vTill also be. possibletostJare sorne physical and hluna.n resources alnong divisions; and by using thenl in

greater scale, collect sonH.~ size and experience benefits .(discontinuities} la'll of 2/31

learning.. etJ~.).- IvIontg01l1ery.. 1979; Bettis.. 1981; Rlunelt" 1982.Sirnilar industries' also tend to have silnilar key success factors facilitatinK the r:nakh of the organizations st.!engtl1s 'NittI thenl1 cotnpared to a situation -Volhere tll€' Qrganization faces very distinc.t tast environrnentsl each with itS O'Vvrrl

set

of su~ccess factors. (Vasconcf.?l1os"1988).

In short an organization achieves synergy when" by tliversifying into related , task environlnents .. it is able to. share sorne resources (r{lachiner!l', plant, s;:t1es force"

/

\ etc.) and therefore collect size and experience benefits .. or /tile task environnlents exchange extornalities arnong thE-tnl or at least some of

the

1

key success factors are cornrnon alYlong environme11ts J~ciHt9.ting the match of the organization's strengths

with tllern (enabling the. organization

to

have relevant strengtll~.). This typ~ of porga.1~ization V·laS referred as "analyzer" by J\.Hl€-5 and Sno~V' (197{) ..

In figure four.. organizations PI. and C are both specializ(Ki organizzl.tions,. _although organization C is considerably more experienced (old~r) than organization .A.

Organization B ShO~lS synergh~tic behavior since it has built SOBle di1;lersity (but

. •l not very great) inio its operations. Organization D has so much df1lersity a!l10ng its

divisions' task environments that very fe~\l resources can be shared arnong thenl

(and consequently few size and e}::perience benefits can be collected). fJoreoverl becaUS0 the divisions' task environments are very distinctje\A.T e}:iernalities can be exchanged" and tileir l~ey success factors tend' to be very distinct} increasing the

difficulty for the organization in obtaining relevant strengths.

As a consequ€'ncel the sole rationale for a strategic positionning such ~s that of organization D, is the attractivoness of tlle environlnents ti1e organization is in. Organization D is a conglolnerate or a hoiding.

In order to irnplement spl?cia1izatiofl.. synergistic and opportunistic behavior, organizations recur to PHEN'OlviEN/\ SUCH P~S IvlERGERS, AQUISITIONS~ JOINT

•

.

VENTURES.. LICENSING AND l'/lARKETING· p~GREtI'./IEN:rS (Dl..tA.lL IvlARKETING)

agreements (dual lnarli.eting). - p.l.llen, ~1iver ~nd SCI1v·J3.1lie/.1 981; Harrigan" 1~h36;

Lubatkin. 1907.

Mergers, aquisitions and jOint ventures can 'aim at acquiring relevant strengths..

itlcrease tll€' scale of the operations and tllerefore reap size and experience benefits

~r access to highly attractive environluentS v?hie11' otll(~i\.\lise (for leg.a! or cultural

reasons) vlou.1d relnain closed. ' .

lvlaxl~etlng agret:fflents usually involve tll~ host organizaUon tal{.jng the sales lnanagernent of products or services from a cornpany v...'liich i.s neV·l to a given rnarl(et.

It ~iffers frorn a license agreernent .since the host organization is not given rigths to

potential l::.novl-hoT.,h,T. Both licensing and marteting agreern~~lts are nll~allS by v·lhich

organizations exploit -U}e attractiveness of tasl~ environrnentsl th?t is., of specific

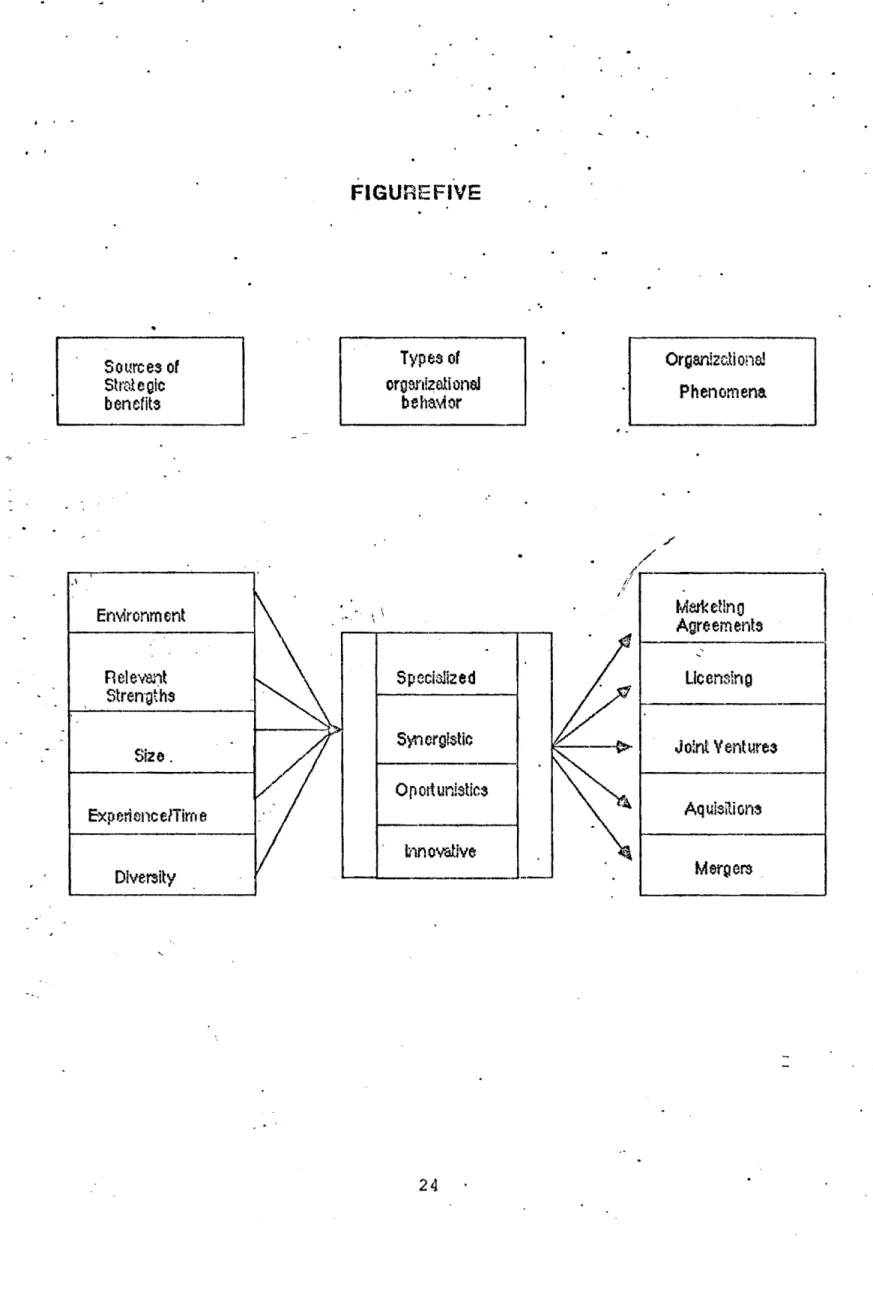

lnarkets of specific countries. Figure five surnrnarizes sections 5.1. and 5.2 .

.'

\ ....1. 2 - The' Relationship Among Different Rese~.rcb StrearflS .\ ,

Using the lnodel d,~v,~10p~d in this articlel it is possible to put into perspective

DIFFERENT RESE"'!.l.RCH STREf.... hfS in the literature .

. pJ. first pro~lp of Hteratur~ streams can be seen as focusing on environn~lt:~nt

enactment. that is.. on hov·, to enact. attractive enVir01l1nents and hO'Vl to manage t11e

process. They· are: Innovation Hterature; literature on environnlental scanning

t?chniqu.es such as environrnent oriented fllanagenlent information SYSW1l1S and

organi.zationa1 systems to analyze clients/consumers; entrepeneursllip literature;

L •

. segmentation literature; and organization sociology literature v.lhicll focus on the

cliaracteristics of environmentS (such as ricbness.. turqulence and compleyjty)

pJ.bernathy and Utrort)ttck} 1'978; Tushnlan} 1979; Bur~t.jl!nan} 1983; \~lind and

(.ardozol 1974; Daniel) 1961; Rocl:art} 1979; I..a'\"l!€'l1ce and Lorsch, 1967; Emery and

Trist, 1965; PJdr ich, 1979. .

The Hterature arou1}d BCY.L..shell and other rnatrices; and the stLuctural anc~lysis

of industries. ~Nhich has its roots at industrial economics and predicts the degree of

conlfJ€tition' (and therefore of 1YlonopoIistic pOV\:rer) based on entry and exit barriersl

etct can bo- seen as concentrating on the c~laraC~?rtstics and n.9}\l tJ) select atti~3ctivtt .

environrI1€:nts in t9rrns of gro"\!-i'1:.h; profit POt01ltia1; and sales volurne - Henderson..

1979; Rotschild} 1960.. Strategic Planning f\ssociates} 19&4; Sheph0rdl 1979; Porter..

.

.

PI1vIS and rn3.r~~et. share liti?r~itllre· enh~Hlce s1ze and· exp~~rien(:t? b~nefits. :..

I j •

Heddley.. 1976; Hend,:;-!"soB.. 1900; Bu.zzel and ~ViE:rs-enlia.. 1981; DOY and Ivlont.goBlerYI

1933. A strealn of sociological literat.ure epirornized by' the "-I'IOrk5 - Stinchicor:nbe..

Iv1coi11. and' Vlalker~ 196&; IvrcNei and ThotliPSOll.. 1971; Pfeffer.. 1931 - has also

fo~used on the consequenc?s of organizational aging.

Diversit'/T benefits hcf'·le tleen studied by industrial ec~no!n~sts as \hlell as by the

strateQ'h:: rese;::tr<tl strea!ns \....' ~Nhi(:h bave stressed svnerg, ~., 11 , r dive-rsifk:ation (rnar1::.et or •

t.echfl~logy based) and tlle relationship betv·t~en relatedness and perfornlance

(BaUflloll Panzer and "0lilligJ 1952; Bettis, 1901; Rum-ell.. 1977 and 1982; Chatterjee,

1987; Port.er 1905 and 1907; Y"i11ig~ 19(7).

The concept of relevant stren~rth \~laS first introduced,. ~n the sixties by a group

of authors fronl Harvard: E. P. Learned.. C.R. Cllristt?l1sefl.. KJr.A. Andre\ys and TyV.D. GuUl

(1965).-Fr01Yl this f£1odel evolT,led a research strearn vtI1icl1 tried to ernpiric3.11y assess

the validity of the rnodel .. elaborated on tile-concept of strengthS aild success fact.ors

. .

_ ,and dev€-loped techniques to. find key success factors in ..-different types of environrn.ents. - Daniel (1961); Rocl::.art (1979); Stevenson (19,76); Bullen and Rockart

\ . . . j •

. \ (1 go 1) Jenster (1987); \lasconcellos (1988). /

,

'.. 1\

The lnodel pr(-?sent.(~d in 'this article suggests some opportunities for FUTURE

RESEARCH. TV-IO are especially nOVyv.lorthy. First.there is the need f01' bettE:-r models

to d~toct the critical success factors in different types of- t3.StS environrnents. These

\ models should start v.Jith the ctlaracteristics of the tasl{ enT·liroHlnc·nt ancl t.hen extract

itnplications r<?6arding ~\lhat the key success factors are. Second, tlle r()l~ of the environin€·nt as a !110derator of size} experience and div~rsity benefits should also l)e investigated. It can 1)0 hypothesized that d0pendillg upon tile charaf:teristics of the

.~ environrnent (con1.plexity} l1etA~rogl.;.n€·it}:TI turbulence, .etc.) the potential of size}

exp.s-rience and diversity dir[l~nsions in gerleratin~ positive and negative

consequen.ces \\1111 vary. This is also a task. for future research.

VI. - CONCLUSION

This article presented a nl0del \\Thich states t.~at ulthnately all org3.111zational

behavior must. be int€·rpret.e·d in terms of organizations trying to exploit five §ources

of strategiC benefits: the environnlenl attractiveness (prOfits.. sales} gro\\1t.tr)I size., .

. '.

Depending upon \",liic:h sources of strat€'gic b;1!~lefit:s organizations choose

to

I I

COl1(:ent.rat(J on" it. is possible to distin~uish b:et:<A7e-en effect.iv(:ness and offk:iency'

strategies. Effectiven€'ss strategies focus on the environment dimension. Efficit?'nc~l

strategies focus on .tile oUier four· sources o.f strategic benefits and air11 for

cC!mp(~t.iUve adv::1.11tage.

To achievt? efficiency {(:ornpetitive advant3.g.e) tVlO "main ,avenue,s are open to

. .

org::1.nizaJions: to Gxpl1")it tlle naturc- and clu.1.ra(:teristics of t.heir re~;ources by correctlit •

poslti':)f1ing , th(~ organization in torrns of size, e}~erience. /time and diversity; or to

increase tlle valu(~ of their resources .. that is., to aquire relevant strengtlls.

The utility of the model pr~ented in this article -lies in its capacity for

interpreting organizational phenornena sucll as mergers .. joi~.t ventures and licenSing; for its· ability to put-different types of organizational bebavior ~nto perspective:

(s;luergislic, sp0ci;;1.1iz€:d; opportunistic and innovathl 0) and for its ability to relate various research streanls (rnartet sh~re literatun:, it:ldustrial analy~~is literature, et~.).

Based 011 ttl€' fllodel developed in this article it is also possible to identify· sonle major

opportunities for future researcll. . / '

.\ ,:1 /

.. .. ~ i I \

\

t"lgure une

..'

-I

....

I

11 -Pollution I ,

... Ethics ir. I ' .. EXTERNAL

m~.!'keting \. ---+- CONSTITUENCIE"1 . . (OOrISUfl"lerism,eto.) (

\.

I III

I I \ \I

Que.!ity ot .I

12-JOb enriohment

I

.

'>

I Life II

I INlERNAL I

I -

DeoerltralizeJ:ion tf \' " C ' " Ot,stlt.uenCles I

I -

St'yie 0,' le~.det·shipI

II - Org:;cnlz81lonaJ I

-e:,

org~,.t'!iz$.t.ion---1>-

( I II I Developrrlent

l

ri'terflb~f'S) r II

i I I I t t (J') I I I II

"I

z

II 3. EnvirorlmentI

Sc..~ht':l 0 I ! " Selectiorl 'Nt.:If,~ r-I I\ EN\" IRONt'lENTAL Organizatior.sl

.>

I0 I I.>~ ATTRACilVENESS ~ffeot.ivene5S: - + J

,

)-«

l

4. Envirol'lri'lent ,..- ,I . (f) l Ene.otrnent rI,

tI

Iz

.I'

(Innovation)\

I ! r 0I

I I i- ~~\ I I I <1.: " ~ I I t::l i I..

I---

.••.•.. 5. M.l0h of orgMiz:a-I .

.

.

I

I I, I L_ t~ ... ~iorl~ strengths I, . Developrr.erlt high

1\

\ .,.

I

I

r

•

I

0 " with keysuocess ~VALUEresouroes - . . .

.

'. SteYtd:Etl'd0: " fMtC1rs ( .,.. ldevelopl'I... ~r.t of re!eV"'#'It r I 0

I

I " st.l"erl!::jths1 .'7

. of I - . \ • I " lI

o.

Long Range ?rogrwtming I . \ . . f LifeI " \ Orgs.t)Jz$.l:lor.sJ I ·1 I I '".~ · I

I.

r I-,>

.

- + I ' I I i \ \ Efflolenoy. I

I17, :os}ti"nnirlg t~e organi::::~,..

I

E>q::loit&.tkm o~...th;.,r·~.,J..1lIFiE -'&,ND/I

I.

I;

tIO~' In te:1'I1S of, II CH...RACTER loJT,'.... S of I

A -Size \.~'es:~I..lt'ce$ (int:~.~)glbj.. I

I

B -Experienoeliiri"~e ( !itYJ e>aet't'I:Aiti~s --\'lI--

I

C - Di'y'et'Sity

l

discol'lt.ir.l~itjes:; eto.)I

I '

~,lOTE: .. rrleans implies.

.. .

FIGU~ETVJO

Naturo °rG3nl:mUonal Dimensions

.

...

and Size· Expor1oncal DlvGrslty

charactarisUcs Time of too rooourC09 .

.

.

. Pubt!c roroUrcG9V

(lr,tang5:>ia) ..

Halfl-plbllc r;)SOUfCeS (gonomlors of oxtor-V

reUl!$s) . Law of 213V/

Di~nllnuHIe,.

V

LeamJng-V

V

Rosourco$ haVG dln(~ront

V

V

$1rongths anctwoakMs$$s >t- .. '" EqufflnaUty v "'" W /i (f) Z (WJt.'\ln propgrty as~ambJsd I W w .I0

8

too rr~$OUf'CGS compleMent Il /

0:: 0: each other makin:g a.total

:J w whola whk:h 1ha cllQnt \

-0

tu

prnf9r~ to buy for oomp~fbl- "(f) -:r.: lity and time reaSQns vl:l -- ...

W n vi, tho t&Pa~.t~ puretase

C( of th3 h~dlv!dU'2l-1 P~:tf1') W ---' t

«

law RI!k dagAia$a1>

ofV

l /

ex: great (L ~m-o.f3 - ex: PoUt!ca1V

W 1-----I

3=

tJart<atV

0 0. RGclpr~1V

Purch:~i~ c_ InteriorityV

-V -

Indicates which_ diniensi~'1s exploit tht~ vBjiousresources characteristics .FIGURE TH.HEE; .

'RB-tin 9 in t enns ot

lmport;;rtce for Peffonn enc e

• 3·A 7 (critical success A' FieleYBnt 'l~eBlm8ises A'"

~A-,,,~--_1~1~---~~~~~~--~~2---T

In-elevBi"lt ltreley~:r.nt '/'IesJmesses . S~t'ef)gths .-.

tactors) 6 5 4 3 Ratin 9 in tenns of value cOt"np;3Jed to cornpetition 2 3 4 5 6 7(Wet\kn ess1 . . (Sfrength}

R;3tin g in tenn::: of Ratit19in tenrr:; of

1m portance tor 38 1m portance tor ./{c

- Pelforrn ence Petf onn enc e 1.7'

High efficienc':/ org~l,niz8.uon 7 7 B'" _ Fiele\i':9nt

~

. . ReleVBnt . V'/e~.kt,.~sses 6 Strengths . 5 ltl"E!f>:!VBnt IrreleV81'lt. 3 3Il'"e:?J::n€!sses Stt-en!~ths

~ ~---~~----2 3 4 5 6 7 . Rating in terms of volue compared to cornpetition 3D lo\o/ eftici ency

r t\4edlum efficiency organization

c

Relev~;'tlt ReJew.t Wes.knesses Strengths trrele~t In-elevsflt We~jm~sse$ StrBngt.hs 3 5 6 7 Ratin gin t errns or v·a1ue compered to competiti onRalh 9 in tem1~ of org~·lization

1m portanc e (or 7 --~---r-~r-~---, Pertotmence 6 5 Relevant Weaknesses Rele'r'at Strengths 4 D" ItYelevsnt dv Irrelew.nt 3 Wesknesses. _ _ _ _ _ _ u ~trengths

J

2 4 5 7 Rsting in tenl1S or \WUf: c(lrnpB.red toI I

...

".

• <

. Tim e ( exp eti ence) Dim ensi on

FitmC ....

---_

...

---.--

.;

.---.--.~...

:.'~

Size .. ' ~ :.~' " . Dimensicln FirmA ....;•••..

---. ----;..-...:---t;7'-.---....'--...

FInn 0 . --••...•••...•~--

•...• - / f" . Bj

•. , ~~•• _••• :-....----.-.-.-. m'O • ....:-.----~.---.-.--:,.:;;:~.:.-. ... :"'''''''''''... i : "~.... _ ~ ".E • .,;I '~.' ," : ,.. ,.. : ,.; ..,.,..r "x... < : . . . • / j.I' < I ' ... : ... " • " ...._ • I " •• ~ .: " " ;. ~ "", -..; ' , l ! :'. _~' , ' t '""

... I , r . . . ' .'-.. ,.' . .: / ~ .:..

.... .... -.~ Diversity DImensionNote: - firrn C has the sanle degreee of specialization as firm A but is considerabl~J rnore experienced.

- FinTl 8 t-Ias U-Ie sarne experience as fitTn A but opted for more diversity (it is rnore diversified).

- Film 0 rates hi9f1est in th'~ diversity dirnension.

.

'. .

FIGURE FIVE

"0

Types of Organ!zc.ti Oriel

organ!zationaJ Phenomena behavior " , / / ,/' ;/ .l,/ I I I , \ Sources of Str01egic benefits .\ En\tironm ent Rele"Rlnt Strengths Size. ExperiencelTim e Diversity Specialized Syn erglstic

o

fJ Ott unistic3 Innovative tiflarn etin (1 Agre ements ," licensing~

-

Joint Venture3

AquisiUon3

Mergers

REFEEENCES

.

'p"U:en.. }'1i. and

J.

Hase.. (196t» Organizational In~rdependence 'andIntraorganizational structure .. Arnerican Sociolo!7J ical Revie'N. 33..

.

Alb~rnathy.. '.'ftl. and K. ''''layne/' (1974) - Lilnits of th€' Learning Curve.. , Ha.rvard

.

Business HE~1liev.l. Sept. - Octob'l 109 - 119.Albernatlr,T..'IV. and

J.

Utterbacl{ - Patterns of Industrial Innovation, TechnoloQY.Revie\hl. June.. July.. 41 - 47.

,Allen.. Iv1.G ... A.R. Oliver and ER. Schwal1ie - The Key to Successful Acquisitions..

Journal

of Business strategy. Fall pp. 15.Andre,,?s~ X.R.o {197

en -

The Concept of Corporate Strat.eey. Ne",V' :(ork.. lrwl.n Co., l·.lldrich~ ·A ..l~. (197'9) -Qrgailizations and Environments. Ne~:iYOrk, Prentice Hall. Ansoff.. H.I. (1967) - Corporate Strat.egy.. New York.. ~cGraw-Hill.

Anthony.. R.N. and

J.

Dearden, (1988) - lvianagement Control . . SYst.erns, HOIY1e~"oodIllinois.. Richard D. Ir'Y\lin.

Bainl

J

.S. (1956) - Barri(~rs to N~'..\, COlnp~tition. Carnbridge.. I'.Aass: Harvard University PrE?ss.BaUlnol;

'N.J ...

J.C.

Panzer and R.D. Willig, (1982) - Contestable lnarkets and the theoryof industry Structure. New York.. Harcourt Brace Jovaf.Lovi(:h~

Baumo1..

'N.J.

and A.S. Blinder.. (1988) ~ Economi(s: Principles and POli.fY., New York"Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Inc.

Bettis.. R.i\.. (1981) - Performance Difference in Relawd and Unrelated Diversified Firins.. Strat~gic Iviana~f~n1ent Iot1rna.1. 2.. 379 - 394.

Blair}

J

l.·tV'1 (1972) -. EconolnicConcentration,

N~w York" Harcourt Bra.ce Jovanovich, Inc.. .

Boston Consulting Group J (1968) - Persp0(:tiv~~ on E~merience~ Boston" BeG Inc.

Bullen" C.'l. and

J.F.

Rocltart" (1981) - A Prirner on Ctitica1 Success Factors" "vVortin...~Paper.lvIIT. .

Burgellnan.. ~.A'J (19&3) - Corp?rate Entrepeneurship and Strategic l'lIanagement: Insights for a Process St.udy.. I·...·!ariagerneilt Science.

?9..

Buzzell" R.D. and F .D.· 'iNiersema" (19a I) - Successful Share BuH<iin{:( . 0 Strat~!'Yc-.ies..

Bu.zzell" RIL, Jan.- February" (1983) - Is vertical Integration Profitables, Farvard

BusinE$S Revie~l. 92 - 102.

.

Carrnan.. J.hi. and E. Langeard" (1980) - Grov.,1:h Strategies for Service Firlns" Strategic

:f....JanaQ'~r{lerit TournaI. 1, 11. / ;

/ . /

/ / I I

Chatterjee.. S'I (19&6) Tipe~ of Synergy and Econornic Value: The I~pact of A.cquisitions on Ivlerging and Rival Finns.. Strategic 111an~gement Journal. vol.

. 711119-139.

Cllil~"

J.

January,,· (1972) - Organization Structurel Environment and P~rformanceThe Role of Strategic Cll0ice, Sociology. 6" 1-22.

Chriften~;I~n" CR~" K. Pl.ndre\\lS" and G.L: BO\hl(;·f., (1986)

Cases, Ne\hrYork.. Irwin / Co..

Cooper.. P....C,,, (1979) - Strawgic l ....ianagenlent: New "'ventures and Small Business, in

Stt~ic Ivlana[en"10nt" edt. by D.E. Schendel C.¥l. Hofer, Boston" Little Brown

and Co.., 316 - 32.

Daniel" R." Sept. - Oct., (1961) - I....IanagelYlent .Information Costs" Harvard Business ReT·lieVl.

Day, G.S. and DB. I'viontgomery" (Spring (J 9(3) Daignosing the Experience -~Curve,

Dill.. vIr... 1·...·1arc11.. (1

9So) -

EnvironlIlent asan.

Influence on Iv~anageria1 .L';utonorny, .Adrninistrati'lf: Science Ouart~~rlY.I •

.

.Ernergy.. F.G. and E.L. Trist.. February.. (1965) - T11e causal TeA1.ure of Organizational Envirinrnents.. Htu:nan RE?latiol~ 18.

F~they.. L. and V]{. Narayanan.. (1906) -.l.~ia"croenvironm~·ntal i\na1ysls for Strate~ic },"Ianagernent.

st.

Paul.. vVest Publishing Co. ..

Galbraith, John K." (1967) - The Ne~", Industrial St.3.te. carnbridge.. Ivlass: Houghton J\.Ufflin Co.

Haldi..,,]ohn and David _.Whitcomb.. August.. (1967) - Econornles of Scale in Industrial

Plants, Journal of Political Econoroy. 75, pp. - 373 - 85.

"

-. Hft11.. R., ]. Eugene Haas and Norrnan Johnson.. Feb... (1 (56) Profession and Bureau(:ratization.. l\.ln(-?rican Sociological Revie\Al.

33.

/

/

f

.\ . Hannan .. ~v'i. and Y.P. Fr€leman.. (1977) The popu1a~on Ecology' of Organizations" Arilerican Journal of· Sc;clology.. 82.

... ...

Arigan.. ,K.R... (1906) -}·Aanf!gingJor Joint Vanture Succe~ Lexingtonl lvlass." Lexington

. Books.

Harrigan". K.R." <"19(5) Vertical Integration and.Corporate Strategy.. Plcaderny of lvla.nagement Journal. 20 .. 397 - 425..

.

He1ddey.. B. December.. (1976) - A Fundatl1enta1 Approach to Strategy Development" Long Range Planning. vol. 9.. pp. I 2 - 9.

Henderson" B.D... (1 9aO) - The Experience Curve Revisited" The Boston ConpulU!]g.

Qroup Per§pectives, n. 229.

Hill, C.\V.L. and R.E. HoslcissonJ (1987) - Academy of Ivranagem.ent ReVle\·\1. vol. 12.. nQ

2,

331 -

342.HirsctIIYHUln" 'YV.B., Jan.-Feb,.. (1964) - Profit [rorn tile Learning Curv~, H~vC\.r(t

Business RevieY'.:[. 42.. nQ 1.. 125.

..

. Jenst.er.. ~)eri. ,V ... "(19'07) - Using'Critic~1J Success Factors in Planning .. Lont;~ F~angE:'

Plannin!;.f, vol: 20.. nQ 4.

Kendrict.. j.'I'vY. - Productivity 'Trends: Capital and Labor.. 'Nati01l3.l-Bureau of E(:(in~)lr1ic

Research. Series of Occasional Papers. nQ

53..

1959.. Lau.. "LaT ..qrenc~

J..

and Shuji Tar[lU~a.. Nov?n1ber ~'Decen1ber, (t 972) ECOn()lT1ief: of Scale .. Technical Progress and the Nonl1or.notl1~tic Leoutief Production Function.. ' lou.rnal of Political Econorny. 00, 1167 - 87.Lav.1fence.. P.R. and G.'tV. Lorsch.. (1 (67) - Organizatio~s and Environment. Cambridge..

l'viass: Harvard University Press.

Learned, ~"P" CR. Christensen.. K.R. Andre~tVs.. and 'f1.D. Guth.. (1 965t Business PolicY""

NeVI Yor1,-.. Richard D ... IrT'/\lin.

.

, Levitt .. T" (1965) - Exploit the Product Life Cycle.. Har~lard Busin~.sg' ~ ReTyTie'rl. 8-94.

I/O

. . i

!

Le";lin.. Richard C'I O(~tober.. , . . (1977) -\ Technical Change and 0pUlnal Scale~ Some

~vidG'nce and I1nplicitions.. Soutl1ern Econonlic JQ.11rnal, 44.. 208 - 21.

Leontiades..

J

,C'I (1984) - Ivlultinational Corporate Strategy., Planning Revie\~ 14 - 41..1'/1ay.

Lorange.. P... IvLF. t·Aorton and S. Gosh~1.11 (1 9a6) - Strab9gic COl1trol Systems.. St. Paul..

vVest Pub1ish~ng Co.

Lubatkin.. lvl ... (1957) - Ivlerger Strategies and Stockolder Value.. Su-ategic_lvlanagernent Jour.n& 81 39 - 53.

, I'IIcHeil.. K: and J.D. Tllomps()n.. (1971) - The Regeneration of Social Organizations.. Anler iean SO(.iQlQgfcal R.e'liev.!. 36.. 6~4 - 637.

Miles.. R.E. and C.E. Snowl (197a).. Organizational S1rat.e!7Y, Structure and Proce~

Montgonler)1.. C. (1979), Diversifi(::3.tE:n1 t,,!artet. StrnctJJ.fe and Econornic Perforrflance:

An E~rt.ension of RUfnelt's hfo(1&1, unpublished doctoral dissertation.. Purdue

tJ,niversity.

Nystrorn.. H... (1979).. Cn?3.tivity and InnoT'f"atioH. Ne;y'.rYork.. J01111. "vViley and Sons.

PItts.. R.pJ.. and C.C. SnoTY\l, $trat.egJQs for COll1petitive Suc:cess~' Jolln 'Hiley and Sons, Nev·,

' .

Yorl{.. 1986.

'

Porter..

~

L.VI. and E..A. La'vlIer, (1965)" Properties of O~ganizatlona1 Structure in Relation

to Job P.~ttitudes and Job Behavior.. Psychological Bulle~in& n2 1... 23 - 51.

Porter.. loJ." (1985) - Cornpetitive p"dvantage. Nev? York.. The Free Press.

Porter.. ~':t.. (1950) - CC1rnpetitive Strategy. l'~e"y'« York.. The Free Press ..

,Pfeffer,

J.

and GR. Salancik.. (1978) - Th~ External. Control of Or~arrf2ations, NeTy\>T York..Harper and. Row. . /fl

,. , ~."'I

Pfeffer,

J.

(1981) - SOlne·cons~quences

of Organizatiqnal DetIlography: Potential - Impacts of an Aging' Vfork Force on Formal Organizations, pJ.C3.den1Y ofJJfan_?£5~lnent Revie·vv. 291 - 327 .

.

. - Robinson .. EpJ.:G ". (1950).. The Structure of Competitive Industry, The University of

alice.go Press.

RotscllHd, W.E., (1 gaO) - HO":N to Ensure the continued Grov·lth of StrategiC Planning...

Journal of Business Strategz vo1.1. StrategiC. Plannit~g As-sociatesl Inc., (1 98l)"

commentaries: Beyond the Portfolio, Washington. D.C.# Strategic Planning

l~ssociates.

Rockart.. 'G.P. llIarcll/pJ.pril" (1979) - Chief ~ecutive D~fi!J_e their Data fiews1 H?fVard .

Business Revie~ pp., - 23.·

Rumelt, R.P... (1982) - Diversification Strategy and Profitability .. Stratej;ic h~anag'~!llent

lQ.Qfnal.

3.. 335 -

369.RUllle-It.. R.P "

(i

<)77) - Diversity and p4rofit:1.bilitvt Annuhf l'Y'le~ting Proo?edings of the'I '

¥lestern Region, P",cadc·rny of l·Aanagetnent, Sun Valley, Idaho.

SatnUelSOll, PA... (1936) - ECol1otnics: An, Ifltrodu.ctorv Analysis. New Yorlf.. IvlcGravyT

Hill.

Salter, f·/LS. and' vVA. '1Neinholdl (1 <)79) - Diversification t.hrough ....~.\cql.lisition:

Strategies fe)t" CreatiDg Econofnic ':lalue, Nev-l York, The Free Press.

'

.

. Scherer" Flit, (1900) -' Industrial Jv!arl:et. Stru.ct,ure

.

and Economic P·?rformance,Chicago.. Rand f'/icNolly College P~blishing.. Co.

Scherer.. ~.l'v'I., A. Beckenstein, E. Kaufer and R.D. Ivlurphy, (1975) - The Economics of Iv1:Ultiplant Operation: An Inwrnational COl:nparaison Study" Cambridge,

, Massachussets. .'

Schimrn, M.G'I Spring, (1958) -' The New Look. in Corporayon La't/·ll La,,,, and

Conten1pora

rt

Pro!)1e2.1ns. vol. 231 175· • /1'.!,"

,'.

.

~ \I

Shepherd~ 'V.G. - The Econoniics\ of Industrial Organization.. Englewood Cliffs, New

Jersey.. Prentice-Hall, 1979. .."

.. - '. Shepherd .. '''''.G., (1970) - I·Aarket PO~Ner and Economic \~e1farel New York... Random

House.

. .

Singh., H. and C.FJ.. Iylontgo[nery" (1987) - Corporate F.Lcquisition Strategies and

.' Economic Perfoftnance" Strategtc l'y'lanaQement Journal. vol. 8" 377 - 386.

Stevenson" H..H... Spring (1976) - Defining Corporate Strengttls and Vveaknessesl Sloan

Managelnent Revie'i/'. 51 - 68.

Steiner1 G.A ... (1985) - StrategiC Planning, Ne:r' York" The Free Press.

Stinchcombe" ~i,L'1 M.S. }.AcDill and D.R. '~lalker" (1 <)68) - Demography of Organizations,

Alnerican Journal of Sociology. 741 221 - 229.