www.bjorl.org

Brazilian

Journal

of

OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Are

people

who

have

a

better

smell

sense,

more

affected

from

satiation?

夽

Seckin

Ulusoy

a,∗,

Mehmet

Emre

Dinc

a,

Abdullah

Dalgic

a,

Murat

Topak

a,

Denizhan

Dizdar

b,

Abdulhalim ˙Is

aaTurkishMinistryofHealth,GaziosmanpasaTaksimEducationandResearchHospital,DepartmentofOtorhinolaryngology,

Istanbul,Turkey

b˙IstanbulKemerburgazUniversity,FacultyofMedicine,Bahc¸elievlerMedicalParkHospital, ˙Istanbul,Turkey

Received16March2016;accepted14August2016 Availableonline12September2016

KEYWORDS

Sniffin’Stickstest; Fastingperiod; Satiatedperiod; Humans; Smellfunction

Abstract

Introduction:Theolfactorysystemisaffectedbythenutritionalbalanceandchemicalstateof

thebody,servingasaninternalsensor.Allbodilyfunctionsareaffectedbyenergyloss,including

olfaction;hungercanalterodourperception.

Objective:Inthisstudy,weinvestigatedtheeffectoffastingonolfactoryperceptioninhumans,

andalsoassessedperceptualchangesduringsatiation.

Methods:The‘‘Sniffin’Sticks’’olfactorytestwasappliedafter16hoffasting,andagainat

least1hafterRamadansupperduringperiodsofsatiation.Allparticipantswereinformedabout

thestudyprocedureandprovidedinformedconsent.Thestudyprotocolwasapprovedbythe

localEthicsCommitteeofGaziosmanpas¸aTaksimEducationandResearchHospital(09/07/2014

no:60).ThestudywasconductedinaccordancewiththebasicprinciplesoftheDeclarationof

Helsinki.

Results:Thisprospectivestudyincluded48subjects(20males,28females)withameanageof

33.6±9.7(range 20---72)years; their mean heightwas 169.1±7.6(range 150.0---185.0)cm,

mean weight was 71.2±17.6(range 50.0---85.0)kg, and average BMIwas 24.8±5.3 (range

19.5---55.9).Scoreswerehigheronallitemspertainingtoolfactoryidentification,thresholds

anddiscriminationduringfastingvs.satiation(p<0.05).Identification(I)results:

Identifica-tion scores were significantly higher during the fasting (median=14.0) vs. satiation period

(median=13.0). Threshold(T)results:Thresholdscores weresignificantly higherduringthe

fasting(median=7.3)vs.satiationperiod (median=6.2).Discrimination(D)results:

Discrimi-nationscoresweresignificantlyhigherduringthefasting(median=14.0)vs.satiationperiod

夽 Pleasecitethisarticleas:UlusoyS,DincME,DalgicA,TopakM,DizdarD, ˙IsA.Arepeoplewhohaveabettersmellsense,moreaffected

fromsatiation?BrazJOtorhinolaryngol.2017;83:640---5. ∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:seckinkbb@gmail.com(S.Ulusoy).

PeerReviewundertheresponsibilityofAssociac¸ãoBrasileiradeOtorrinolaringologiaeCirurgiaCérvico-Facial.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2016.08.011

(median=13.0).ThetotalTDIscoreswere35.2(fasting)vs.32.6(satiation).Whenwecompared

fastingthresholdvalueof>9and≤9,thegapbetweenthefastingandsatietythresholdswas

significantlygreaterin>9(p<0.05).

Conclusion: Olfactoryfunctionimprovedduringfastinganddeclinedduringsatiation.The

olfac-torysystemismoresensitive,andmorereactivetoodours,understarvationconditions,and

ischaracterisedby reducedactivityduringsatiation.Thissituationwasmorepronouncedin

patientswithabettersenseofsmell.Olfaction-relatedneurotransmittersshouldbethetarget

offurtherstudy.

© 2016 Associac¸˜ao Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia C´ervico-Facial. Published

by Elsevier Editora Ltda. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

TestedeSniffin’ Sticks;

Períododejejum; Períododesaciedade; Sereshumanos; Func¸ãodoolfato

Aspessoasquetêmmelhorolfatosãomaisafetadaspelasaciedade?

Resumo

Introduc¸ão: Osistemaolfatórioéafetadopeloequilíbrionutricionaleestadoquímicodocorpo,

que serve como um sensor interno.Todasas func¸ões corporais sãoafetadas pela perdade

energia,incluindooolfato;afomepodealterarapercepc¸ãodoodor.

Objetivo: Nesteestudo,investigamosoefeitodojejumsobreapercepc¸ãoolfativaemseres

humanos,etambémavaliamosasmudanc¸asdepercepc¸ãoduranteasaciedade.

Método: OtesteolfatórioSniffinSticksfoiaplicadoapós16horasdejejumenovamentepelo

menos1horaapósaceiadoRamadãduranteosperíodosdesaciedade.Todososparticipantes

foraminformadossobreosprocedimentosdoestudoeforneceramoconsentimentoinformado.

OprotocolodoestudofoiaprovadopeloComitêdeÉticalocaldoGaziosmanpas¸aTaksim

Educa-tioneResearchHospital(2014/09/07n◦60).Oestudofoiconduzidodeacordocomosprincípios

básicosdaDeclarac¸ãodeHelsinki.

Resultados: Foram incluídos 48 pacientes (20 homens, 28 mulheres) com idade média de

33,6±9,7 (variac¸ão 20-72) anos; a altura média deles erade 169,1±7,6 (variac¸ão

150,0-185,0) cm,opeso médioerade71,2±17,6(variac¸ão de50,0-85,0)kgeIMCmédio erade

24,8±5,3(variac¸ãode19,5-55,9).Osescoresforammaioresemtodosositenscorrespondentes

àidentificac¸ãoolfativa,limiaresediscriminac¸ãodurantejejumvs.saciedade(p<0,05).

Result-adosdaidentificac¸ão(I):osescoresdeidentificac¸ãoforamsignificativamentemaioresdurante

ojejum(mediana=14,0)vs.períododesaciedade(mediana=13,0).Resultadoslimiares(T):os

escoreslimiaresforamsignificativamentemaioresduranteojejum(mediana=7,3)vs.período

de saciedade (mediana=6,2). Resultados dediscriminac¸ão (D):os escores dediscriminac¸ão

foramsignificativamentemaioresduranteojejum(mediana=14,0)vs.períododesaciedade

(mediana=13,0).OsescorestotaisdeTDIforamde35,2(jejum)vs.32,6(saciedade).Quando

comparamosovalordolimiardejejumde>9e≤9,adiferenc¸aentreoslimiaresdejejume

desaciedadefoisignificativamentemaiorem>9(p<0,05)

Conclusão:A func¸ãoolfatóriamelhorouduranteojejumediminuiuduranteasaciedade.O

sistemaolfatórioémaissensívelemaisreativoaosodoresemcondic¸õesdefomeeé

carac-terizadoporatividadereduzidaduranteasaciedade.Estasituac¸ãofoimaispronunciadaem

pacientescomum melhorsentidoolfativo.Osneurotransmissoresrelacionadoscomoolfato

devemseralvodeumestudomaisaprofundado.

© 2016 Associac¸˜ao Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia e Cirurgia C´ervico-Facial. Publicado

por Elsevier Editora Ltda. Este ´e um artigo Open Access sob uma licenc¸a CC BY (http://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Allbodilyfunctions areaffected by energyloss,including olfaction; hunger can alter odourperception. Changes in subjective evaluation of an unchanging food stimulus are commensuratewith changesin hunger state1; recent

evi-dencesuggeststhathunger statecansimilarlyaffect food odourpleasantness.2 Althoughthe mechanismsunderlying

alterationsfor foodand odourstimuli (e.g.,frompositive tonegativefollowingsatiation)arenotyetunderstood,loss

ofenergyislinkedtochangesinolfactorybulbactivity3and

olfactorysensitivityinrats.1,4

Theolfactory systemisaffected bythenutritional bal-anceandchemicalstateofthebody,servingasaninternal sensor.1 The endocrine and olfactory systems are linked

Farhadianetal.6studiedtherelationshipbetween

post-fastingbehaviour andchangesinolfactoryresponsiveness, andsuggestedthattheolfactorysystemisaffectedby nutri-tionalstatus:fastedfliesweremorereceptivetoattractive odourscomparedwithsatiatedflies.Thisphenomenonwas demonstrated in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Worms typically react to the smell of octanol by moving backwards,butintheabsenceoffoodthisresponseis sig-nificantlylessrapid.7

In this study,we investigated the effect of fasting on olfactory perception in humans, and also assessed per-ceptual changes during satiation. The ‘‘Sniffin’ Sticks’’ olfactory test was administered during Ramadan fasting andduringsubsequentperiods ofsatiation. Identification, thresholdanddiscriminationscoreswereevaluated.Scores for all of the test items pertaining to these three cate-gorieswere significantlyhigher duringfasting thanduring satiation.

Methods

Forty-eightsubjects(20males,28females)admittedtothe Ear,NoseandThroat(ENT)ClinicoftheGaziosmanpas¸a Tak-simEducationandResearchHospitalbetweenJune28,2014 andAugust27,2014wereenrolled.Allpatientswere partic-ipatinginRamadanfasting.The‘‘Sniffin’Sticks’’olfactory testwasappliedafter16hoffasting,andagainatleast1h afterRamadansupperduringaperiodofsatiation.Themean ageofpatientswas33.5±9.6years.

All participants were informed about the study proce-dure and provided informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee of the Gaziosmanpas¸a Taksim Education and Research Hospital (09/07/2014n◦60).Thestudywasconductedinaccordance

withthebasicprinciplesoftheDeclarationofHelsinki.

Patientselection

The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) partic-ipating in Ramadan fasting; (2) no pre-existing medical, surgicalorpsychiatriccomorbidconditions;(3)nophysical orpsychologicaldisabilitiesthatwouldaffectparticipation; (4)nohistoryofmedicationuseexceptdailysupplemental vitaminsandironpills;(5) noprevious diagnosis ofupper airway disease norprevious nasal surgery; and (6) in the firstperiodofthemenstrualcycle(femalesonly).Smokers andmenopausalfemaleswereexcluded.Allsubjects under-wentanENTexamination,conductedbyENTspecialists,to confirmtheabsenceofupperairwaydisease.

Evaluationofolfactoryfunction

‘‘Sniffin’ Sticks’’ olfactory tests (Burghart, Wedel, Germany)8,9 --- i.e., pen-like odour dispensing devices

---wereusedtoassessolfaction.Odourthreshold, discrim-ination,and identification parameterswere measured. To present each odour, caps were removed from the sticks by the researcher, with the tip then held approximately 2cminfrontofbothnostrilsoftheparticipantfor approx-imately 3s. Subjects were blindfolded to prevent visual

identification of the odour-containing pens. Forthreshold testing, each pen’s tampon was filled with phenyl ethyl alcohol (PEA; characterised by a rose-like odour) diluted in propylene glycol (dilution ratio=1:2, starting at 4%). PEAodourthresholdwasassessedusingasingle-staircase, three-alternative forced-choice (3-AFC) procedure. Three pens were presented to each subject randomly; two contained an odourless solvent (propylene glycol), and the third contained an odourant of a certain dilution. Three newpenswere presentedat 20s intervals, andthe subject was required to indicate the pen containing the odourant. The concentration of the odour-containing pen wasincreasedifthesubjectselectedoneoftheodourless pens, and decreased if the odourant was selected. The mean ofthe previous four,of seven total,reversal points was accepted as the detection threshold (range 1---16).10

For odour discrimination, 16 sets of three pens were presented,twoofwhichcontainedidenticalodourants;the third containedthe targetodourant. Subjectswere asked to identify the unique sample; the number of correctly identified odours wassummed toproduce the test score. Odouridentificationwasassessedusing16commonodours and a multiple forced-choice design; subjects identified odoursbyselectingthemost-appropriateoffourdifferent descriptions.

Statisticalanalysis

AnalyseswereperformedusingtheSPSSforWindows soft-warepackage(ver.22.0;SPSS,Chicago,IL,USA).According totheKolmogorov---Smirnovtestresults,whenthep-value is less than 0.05, variables are not distributed normally. Therefore,nonparametricstatisticalmethodswereusedin thestudy.Inthefirststageofbasic statisticaldata analy-sis,themedian andrangevaluesaregiven.Inthesecond stage involving thetesting of groupdifferences, Wilcoxon and McNemar tests, the latter being two-sided, were used.

Results

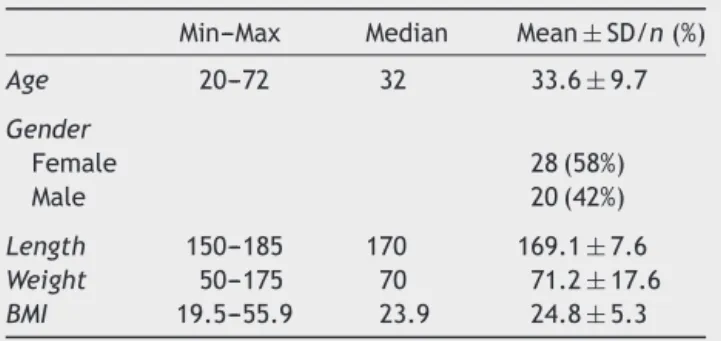

This prospectivestudy included 48subjects (20males, 28 females)withameanageof33.6±9.7(range20---72)years; theirmeanheightwas169.1±7.6(range150.0---185.0)cm, mean weight was 71.2±17.6 (range 50.0---85.0)kg, and averageBMIwas24.8±5.3(range19.5---55.9).Thebaseline characteristicsofthesubjectsaresummarisedinTable1.

Table1 Baselinecharacteristicsofthestudysubjects.

Min---Max Median Mean±SD/n(%)

Age 20---72 32 33.6±9.7

Gender

Female 28(58%)

Male 20(42%)

Length 150---185 170 169.1±7.6

Weight 50---175 70 71.2±17.6

Table2 Overallolfactoryfunctioninfastingandsatiation.

Fasting Satiation p

Mean±SD/n(%) Med(min---max) Mean±SD/n(%) Med(min---max)

Identification 13.7±1.1 14(11---16) 12.8±1.1 13(11---15) 0.000

Thresholds 7.7±1.9 7.3(4.5---13) 6.5±1.4 6.3(2.5---10) 0.000

≤9 39(81%) 46(96%) 0.008

>9 9(19%) 2(4%)

Discrimination 13.8±1.0 14(11---15) 13.2±1.1 13(11---15) 0.000

TDI 35.2(3.5) 35(28---43) 32.6(3.0) 33(26---39) 0.000

Wilcoxontest/MCNemartest.

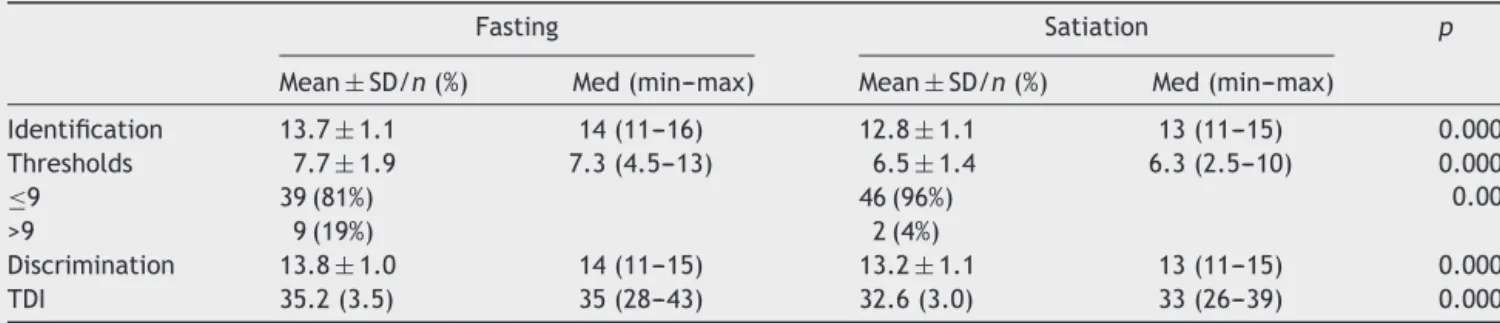

Fastingandsatiationperiodtestresultsaredisplayedin

Table2andFig.1.

Identification (I)results: Identificationscores were sig-nificantly higher during the fasting (median=14.0) vs. satiationperiod(median=13.0).

Threshold(T)results:Thresholdscoresweresignificantly higherduringthefasting(median=7.3)vs.satiationperiod (median=6.2).

Discrimination (D) results: Discrimination scores were significantly higher during the fasting (median=14.0) vs. satiationperiod(median=13.0).

ThetotalTDIscoreswere35.2(fasting)vs.32.6 (satia-tion).

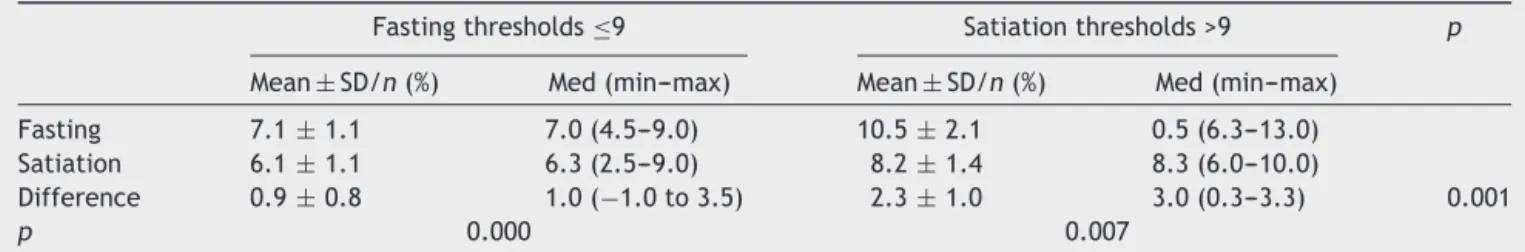

Afastingthresholdvalueof>9wasusedtodefineGroup A;thefastingperiodthresholdvaluewassignificantlyhigher comparedtothesatietyperiod(p<0.05).

Afastingthresholdvalueof≤9wasusedtodefineGroup B;thefastingperiodthresholdvaluewassignificantlyhigher comparedtothesatietyperiod(p<0.05)(Table3).

When we compared GroupsA and B,the gap between thefastingandsatietythresholdswassignificantlygreater inGroupA(p<0.05).

16

15

14

13

12

11 15

14

Identification

Discr

imination TDI

Theresholds

13

12

11

Fasting satiation Fasting satiation

Fasting satiation Fasting satiation

12.5

10.0

7.5

5.0

2.5

45

40

35

30

25

Table3 Comparefastingthresholdvalueof≤9and>9withsatiation.

Fastingthresholds≤9 Satiationthresholds>9 p

Mean±SD/n(%) Med(min---max) Mean±SD/n(%) Med(min---max)

Fasting 7.1±1.1 7.0(4.5---9.0) 10.5±2.1 0.5(6.3---13.0)

Satiation 6.1±1.1 6.3(2.5---9.0) 8.2±1.4 8.3(6.0---10.0)

Difference 0.9±0.8 1.0(−1.0to3.5) 2.3±1.0 3.0(0.3---3.3) 0.001

p 0.000 0.007

Wilcoxontest/Mann---WhitneyUtest.

Discussion

Inmammals,thesenseofsmellismodulatedbythestatusof satiety,whichismainlysignalledbyblood-circulating pep-tidehormones.However,theunderlyingmechanismslinking olfactionandfoodintakearepoorlyunderstood.Olfaction isamajorfactorinthedecisiontoeatafooditemorrefuse it.Appetite-stimulatingandappetite-suppressinghormones alsohaveeffectsonolfactory-drivenbehaviour.

Orexigenic molecules (stimulatory) include ghrelin, neuropeptide Y, orexins, endocannabinoids,11

endoge-nousopioids.11 Anorexigenicmolecules (inhibitory)include

insulin,12 leptin,13 cholecystokinin,14 andnutrientglucose7

have been studied by numerous authors. When hungry or satiated, the stomach, intestines, pancreas and other organsregulatevariousperipheral molecules.14 The

olfac-tory mucosa and bulb, as well as the hypothalamus, are targeted through blood containing these molecules. In response,metabolicfactorsarereleasedbythe hypothala-mustocontrolnutritionalhomeostasis.Theolfactorysystem isalsoaffectedbythesechanges,adaptingtothenutritional needsofthebody.

Serotonin may mediate hunger signals, because its administrationprecipitates feeding in olfactory behaviour trials7;furthermore,infliesantennallobeprojection

neu-ronsareenhancedbyserotoninundercertainconditions.15

Serotonin, or a similar, secreted molecule, might also regulate 3-methyl-thio-1-propanol sensitivityin flies post-starvation.

Themodulationofolfactoryperformancehasbeen stud-iedin metabolic disorders such as obesity, diabetes, and anorexia nervosa. Changing levels of olfactory-modifying molecules alterbrainactivation andthe responsetofood odours.Metabolicdisordersdisruptolfactoryperformance, therebydisrupting energy balance.16 Changes in hormone

andglucoselevelsaredetectedbyreceptorsandpeptides related to feeding. The hypothalamus and olfactory sys-temcommunicate throughtheolfactory bulb, and caloric intakeandmetabolismspeedareinfluencedbytheolfactory system.16

Aimeetal.4suggestedthatolfactionplaysafundamental

rolein feedingbehaviour.The relationshipbetween olfac-tory acuity and feeding status has not been determined preciselyinanimal models;however,theseauthors evalu-atedolfactorydetectioninfastedandsatiatedratsplaced under a rigorously controlled food-intake regimen, and obtainedoriginal dataverifyingthehypothesis that olfac-tory sensitivityis increased in fastedanimals. Sincetheir results were obtained using a neutral odour, the authors

suggest that olfactory acuity increases that occur during fastingenable animalstomore-easily detect salient envi-ronmentalodours,includingfooditemsandpredators.Aime etal.4concludedthatolfactionisrelevanttofood-seeking,

andpossessesaneco-ethologicalfunctioninrats;ourdata areinagreementwiththeirstudy.

Goetzland Stone17 were the firsttodiscussthe acuity

ofolfactionandfoodintakeinarticlespublishedin194717

and1948.18 When satiated,theprimate orbitofrontal

cor-tex decreases its responsiveness to an odour.19 Although

olfactory-driven behaviour in humans has not yet been demonstratedinclinicalstudies,ithasbeenwellestablished inexperimentalstudies.Beforethecurrentstudy,Cameron etal.1werethefirsttopublishareportofolfactory-driven

behaviourinhumans.Theystatedthatchangesinolfactory functioncanmodifyfeedingbehaviour,butthewayinwhich acutenegativeenergybalanceimpactsolfactionand palat-abilityremainsunclear.Intheirstudy,15subjects(9males,6 females)withameanageof28.6±4.5years,ameaninitial bodyweightof74.7±4.9kgandaBodyMassIndex(BMI)of 25.3±1.4kg/m2,wereassessedatbaseline(FED)and

post-deprivation(FASTED) for nasalchemosensory performance using the ‘‘Sniffin’Sticks’’ olfactory test. Food palatabil-ityratingswerealsomeasuredusingvisualanaloguescales. Significantimprovementsinodourthreshold,odour discrim-ination,andtotalodourscores(TDI),andhigherpalatability ratings, were observed during fasting. The authors con-cludedthatfastingfor24himprovesolfactoryfunction;this effectwasassociatedwithincreasedpalatabilityratingsand initialbodyweight.Furtherstudiesarerequiredtoconfirm therolesofbodyweightandsexinolfactionand palatabil-ity.SimilartoCameronetal.,1wealsoobservedimproved

olfactory function during fasting,which decreased during satiation. Compared with their study, our results at 16h wereidenticaltotheirsat24h,andourgroupwasthreefold larger(48vs.15).1 Recently, Hanciand Altun20 conducted

anotherstudy that included 123subjects ina prospective design; their results were similarto ours in terms of TDI scores,buttherewerealsodifferencesbetweenthestudies. ThesubjectsinHanciandAltunwerescheduledforroutine check-upsandfastedfor8hversusour16hfastingperiod. We suggest that, in the morning, humans exhibit certain physiologicalchangesdependentontherecencyofwaking, suchasincreasedsteroidlevelscomparedtobefore dinner-time, asper ourstudy. Therefore, our test schedule was optimisedcomparedtothatofHanciandAltun.20Ourstudy

fastingthresholdof≤9h(GroupA)affected(i.e.,reduced) foodintakeatdinnertoagreaterdegree,i.e.,thesatiation periodhadmoreeffectonindividualswithasuperiorsense ofsmell(GroupA).

Thereareseverallimitationstothisstudy.Thenumberof subjectswaslowandamore-objectivemethod (olfactome-try)couldhavebeenused;furthermore,wecouldalsohave measuredtheeffectsofdifferentfastingdurations(e.g.,8, 16and24h)inourpatientgroup.

Wesuggestthat,inlightofourresultspertainingtothe medicalmeasurementofolfactionusingbotholfactometry andsnifftests,evaluationsshouldbeperformedconsistently duringperiodsofeitherhungerorfullnesstoachievemore accurateresults.Futureworkcouldextendour understand-ingby exploringthe relationship betweenthe taste sense andfasting, andby searchingfor additionalhotspots that mightimproveourknowledgeofobesityandassociated dis-eases.Thiscouldalsoaidthediscoveryofnewanti-obesity drugsandtherapies.

Conclusion

Asaresult,notonlydoexternalchemicalstimulantsaffect theolfactorysystem,butinternal chemicalandmetabolic stimulants are also detected by this system. Increasesin olfactorysensitivityduringfastingmightberelatedtothis pathway, the neurotransmitters and receptors of which shouldbethesubjectoffurtherstudy.Futureworkshould aimtoextendthisunderstandingandseektoidentify addi-tionalhotspotsinthebrain.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.CameronJD,GoldfieldGS,DoucetÉ.Fastingfor24himproves nasal chemosensory performance and food palatability in a relatedmanner.Appetite.2012;58:978---81.

2.PlaillyJ,LuangrajN,NicklausS,IssanchouS,RoyetJP, Sulmont-RosséC.Alliesthesiaisgreaterforodorsoffattyfoodsthanof non-fatfoods.Appetite.2011;57:615---22.

3.ApelbaumAF,PerrutA,ChaputM.OrexinAeffectsonthe olfac-torybulbspontaneousactivityandodorresponsivenessinfreely breathingrats.RegulPept.2005;129:4961.

4.AiméP,Duchamp-ViretP,ChaputMA,SavignerA,MahfouzM, Julliard AK. Fasting increases and satiationdecreases olfac-torydetection for a neutral odor in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2007;179:258---64.

5.WilliamsKW, ScottMM,Elmquist JK.Modulation ofthe cen-tral melanocortin system by leptin, insulin, and serotonin:

coordinated actions in a dispersed neuronal network. EurJ Pharmacol.2011;660:2---12.

6.Farhadian SF, Suárez-Fari˜nas M, Cho CE, Pellegrino M, VosshallLB.Post-fastingolfactory,transcriptional,andfeeding responsesinDrosophila.PhysiolBehav.2012;105:544---53. 7.Chao MY,Komatsu H,FukutoHS,DionneHM,Hart AC.

Feed-ing status and serotonin rapidly and reversibly modulate a

Caenorhabditiselegans chemosensorycircuit.ProcNatlAcad SciUSA.2004;101:15512---7.

8.HummelT,SekingerB,WolfSR,PauliE,KobalG.Sniffin’Sticks olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odoridentification,odordiscriminationandolfactorythreshold. ChemSenses.1997;22:39---52.

9.Kobal G, Klimek L, Wolfensberger M, Gudziol H, Temmel A, Owen CM, et al. Multicenterinvestigation of1,036 subjects using astandardizedmethodfor theassessmentofolfactory functioncombiningtestsofodoridentification,odor discrim-ination,and olfactory thresholds.EurArchOtorhinolaryngol. 2000;257:205---11.

10.TekeliH,Altunda˘gA,Saliho˘gluM,CayönüM,KendirliMT.The applicability of theSniffin’ Sticksolfactory testin a Turkish population.MedSciMonit.2013;19:1221---6.

11.Laux A, Muller AH, Miehe M, Dirrig-Grosch S, Deloulme JC, DelalandeF,etal.Mappingofendogenousmorphine-like com-poundsintheadultmousebrain:evidenceoftheirlocalization inastrocytesand GABAergiccells.JCompNeurol.2011;519: 2390---416.

12.LacroixMC,BadonnelK,MeunierN,TanF,Schlegel-LePoupon C,DurieuxD,etal.Expressionofinsulinsysteminthe olfac-toryepithelium:firstapproachestoitsroleandregulation.J Neuroendocrinol.2008;20:1176---90.

13.Julliard AK, Chaput MA, Apelbaum A, Aimé P, Mahfouz M, Duchamp-Viret P.Changes in rat olfactory detection perfor-mance induced by orexin and leptin mimicking fasting and satiation.BehavBrainRes.2007;183:123---9.

14.JanowitzHD,HollanderF,MarsharRH.Theeffectoftween-65 and tween-80 on gastrointestinal motilityin man. Gastroen-terology.1953;24:510---6.

15.ColbertHA,BargmannCI.Environmentalsignalsmodulate olfac-tory acuity, discrimination, and memory in Caenorhabditis elegans.LearnMem.1997;4:179---91.

16.CaillolM,AiounJ,BalyC,PersuyMA,SalesseR.Localizationof orexinsandtheirreceptorsintheratolfactorysystem:possible modulationofolfactoryperceptionbyaneuropeptide synthe-sizedcentrallyorlocally.BrainRes.2003;960:48---61.

17.GoetzlFR,StoneF.Diurnalvariationsinacuityofolfactionand foodintake.Gastroenterology.1947;9:444---53.

18.Goetzl FR, Stone F. The influence of amphetamine sul-fate upon olfactory acuity and appetite. Gastroenterology. 1948;10:708---13.

19.CritchleyHD,RollsET.Hungerandsatietymodifytheresponses ofolfactoryandvisualneuronsintheprimateorbitofrontal cor-tex.JNeurophysiol.1996;75:1673---86.