Knowledge, attitudes and

practices on tuberculosis in

prisons and public health

services

Conhecimento, atitudes e práticas

sobre tuberculose em prisões e no

serviço público de saúde

Sérgio Ferreira Júnior

IHelenice Bosco de Oliveira

IILetícia Marin-Léon

III City of Hortolândia Department of Health, São Paulo, Brazil

II Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, State University of Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil

Corresponding author: Helenice Bosco de Oliveira. Rua Waldyr Aparecido da Silva, 60, Resi-dencial II – Condomínio Barão do Café, Barão Geraldo, Campinas, SP, Brazil, 13085-065. e-mail: helenice@unicamp.br

Abstract

There are few studies about tuberculosis (TB) knowledge among prisoners, peni-tentiary system workers and public health network (PRN). Those carried with other populations, point out that the lack of kno-wledge about the illness is one of the main barriers to the perception of the symptoms, early diagnosis, treatment adherence and cure. Objective: To analyze the knowled-ge, attitudes and practices about TB in a prison and in public health services (PHS). Methods: A cross sectional study was car-ried out and KAP (knowledge, attitudes and practices) questionnaire was applied to 141 prisoners, 115 prison’s employees and 158 PHS workers. Epi-Info version 6.04 was used for comparison of proportions with statistic significance at p < 0.05. Results: Mistaken concepts on TB were observed among the three searched groups. PHS also showed basic errors on TB knowledge thus pointing out imperfections on training. Conclusion: KAP revealed efficient for data collection of general knowledge items but was limited on practices and attitudes and so its use as the only tool for data collection about knowledge, attitudes and practices on TB is not advisable. It is suggested its regular use to aid educational activities and con-sidering the high prevalence of TB among prisoners, it is noted the need to involve the Departments of Health in the supervision of educational activities in the prison system.

Resumo

São poucos os estudos sobre o conhecimen-to da tuberculose (TB) entre os detenconhecimen-tos, trabalhadores do sistema penitenciário e da rede pública de saúde (RPS), e aqueles realizados com outras populações apontam a falta do conhecimento sobre a doença como uma das principais barreiras para a percepção dos sintomas, diagnóstico

preco-ce, adesão ao tratamento e cura. Objetivo:

Analisar o conhecimento, atitudes e práticas sobre a TB em uma unidade prisional e na

rede pública de saúde (RPS). Metodologia:

Foi realizado estudo transversal com

apli-cação do questionário KAP (knowledge,

atittudes and practices) na coleta de dados. Participaram 141 detentos, 115 funcioná-rios do presídio e 158 da RPS. O programa Epi-Info versão 6.04 foi utilizado para com-paração de proporções com significância

estatística para p < 0,05. Resultados: Foram

observados conceitos equivocados sobre a doença entre os três grupos pesquisados. Na RPS foram detectados erros básicos sobre o conhecimento da TB, concluindo-se que há falhas nos treinamentos. O KAP mostrou-se eficaz na coleta de dados gerais sobre co-nhecimento, porém foi limitado e frágil nas informações sobre práticas e atitudes, não sendo aconselhável a sua utilização como instrumento único na coleta de dados sobre conhecimento, práticas e atitudes em TB. É sugerida sua utilização periódica como auxiliar nas atividades educativas e, consi-derando a elevada prevalência de TB entre detentos, aponta-se para a necessidade do envolvimento das Secretarias de Saúde na supervisão destas atividades educativas no sistema prisional

Palavras-chave: Tuberculose. Prisões. KAP. Conhecimento. Atitudes. Práticas. Serviço Público de Saúde.

Introduction

Confined populations, especially those comprised of incarcerated individuals, re-present a serious problem in the control of infectious and contagious diseases, such

as tuberculosis (TB) and AIDS.1 Even when

surrounded by prison walls, these individu-als are never entirely isolated from society. Bonds with the outside world continue through contact with both visitors and prison workers. Inmates also inter-relate with the community in general through releases to work, granted leaves, escapes and return to society when sentences have been served. In addition, prison workers maintain contact with their own families and the community

in general,2 and this represents a double risk

of contamination. In other words, an uncon-trolled epidemic of TB in a prison facility may represent a serious risk to individuals and to society at large. In the opposite direction, TB brought in from the outside community

can trigger off an epidemic among inmates.3

Moreover, rules related to prison envi-ronments influence the relationship of TB patients with this disease. In this regard, TB

can affect the social4 interaction between

individuals with TB and other inmates, thus reducing awareness of the seriousness of its symptoms.

Among both the general population and incarcerated groups, TB is a topic that is not easily discussed nowadays. It is associated with poverty, isolation, social exclusion, irre-gular and immoral behavior, as well as with social depravation. These values are strongly

present in the stigmatization of TB patients.5-8

Currently, treatment is usually conducted in outpatient clinics, where health workers are exposed to infection. For this reason, and due to these individuals’ vulnerability, it is essential that they have considerable

knowledge about the disease.9

early diagnosis, adhesion to treatment, and cure.10,11

The KAP (Knowledge, Attitudes and

Practices) Questionnaire12 has been used

for gathering data on knowledge, attitudes and practices about many different health

problems and diseases13 in terms of what

is known, believed and done about specific topics. This instrument was constructed in the 1950s and it was originally designed to estimate resistance against the idea of family

planning among different populations.13

KAP-TB surveys can be especially desig-ned to gather information on topics related to TB. This may include questions about general health practices and beliefs regarding the disease. The purpose is often to identify knowledge, patterns of gaps, and cultural or behavioral beliefs that facilitate understan-ding and action. They can also detect proble-ms, barriers and obstacles that arise with the

efforts to control TB.14 Data can be analyzed

quantitatively or qualitatively, depending on

the study objectives.12

The use of this instrument has fostered a certain amount of social mobilization as well as investigations of the knowledge, practices and attitudes about TB in the population. Some of these studies have been conducted in the context of control programs in different countries with high rates of occurrence of this disease, aiming to strengthen interventions

for behavioral changes.12 One increasingly

important use of the KAP Questionnaire has been to provide essential data on the impact of activities related to advocacy, communica-tion and social mobilizacommunica-tion (ACSM).

The present study was based on the as-sumption that, due to their access to training programs, public health workers and prison workers would have adequate knowledge about TB. The study was thus specifically designed to compare knowledge, attitudes and practices about TB among three distinct groups, namely, inmates, prison workers, and public health workers.

Methodology

A cross-sectional study was carried out on

a sample consisting of inmates and workers of P-III Penitentiary which is a closed prison, and public health workers, in the city of Hortolândia, State of São Paulo, Brazil. This penitentiary was selected because it had had no participants in any projects involving educational intervention for TB.

It was not possible to obtain a statistically valid sample of inmates due to the peniten-tiary conditions and security requirements. The inmates were chosen at random, ac-cording to the routine and the institution’s criteria for transferring them to a meeting room. Participants from among the pri-son employees and public health workers were selected on the basis of their own interest.

An adapted semi-structured version of

the KAP Questionnaire12 was designed and

applied. It consisted of closed questions organized into four sections dealing with the socio-demographic situation of respon-dents and the following aspects related to TB: history of the patient’s disease, knowledge, behavior toward the possibility of contracting TB, and attitudes toward patients with TB. The adapted questionnaire was pre-tested in the PI Penitentiary, located in the same complex.

The instrument was applied indivi-dually by an interviewer to both inmates and prison workers. The questionnaire for health workers was distributed to all pro-fessionals working at the selected public health units and each participant filled it out individually.

Ethical Issues

Prior to application, the present rese-arch project was authorized by the State of São Paulo Department of Penitentiary Administration and by the City of Hortolândia Department of Health and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the State University at Campinas, under official expert opinion 942/2009 of the National Board of Health Research Ethics Committee, pursuant to Resolution 196/96. All participants signed an informed consent form and confidentiality of information was guaranteed.

Authors declared there were no conflicts of interest.

Results

At the time of the application of the questionnaire, 233 prison workers were as-signed to the PIII Penitentiary. Of these, 88 were on leaves of absence for medical rea-sons, temporary transferences, vacations or bonus leaves. A total of 115 were interviewed (79.3% of those 145 actively working). According to prison authorities, 1,153 male inmates were under detention at the time, 141 (12.2%) of whom were interviewed. For security reasons, the data collected from inmates had to be discontinued.

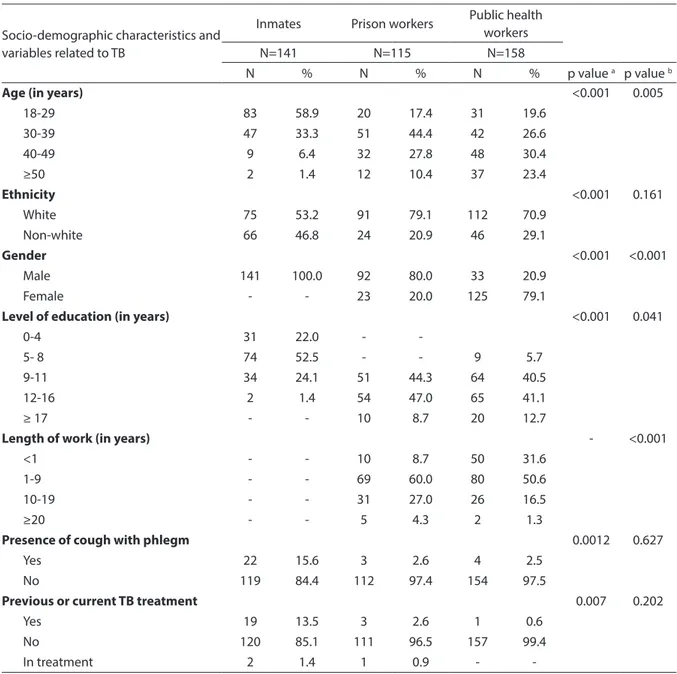

According to the Department of Human Resources, there were 1,216 active workers in the Department of Health at the time of the survey. Of these, 208 were on leaves of absence and 158 of the 508 (31.1%) working in the participating units were interviewed. Emergency units, the municipal hospital, and the adult and child mental health outpa-tient clinics were not included in this study. The respondents in one group of 35 inmates (24.8%) stated that their last arrest had been less than one year before, while 11 (7.8%) reported that it was more than six years before (data not shown). Table 1 shows that inmates and prison workers were different in terms of age, ethnicity, gender and level of education (p<0.001). Among prison workers and public health workers, differences were related to age,

gender, length of work (p<0.001) and level of education (p = 0.041).

In the investigation of respiratory symp-toms, the inmates had cough with phlegm in a higher proportion than prison workers (15.6% vs. 2.6%, p = 0.0012). A greater per-centage of inmates reported having been treated for TB previously (13.5% vs. 2.6% p = 0.007).

Knowledge about Tuberculosis

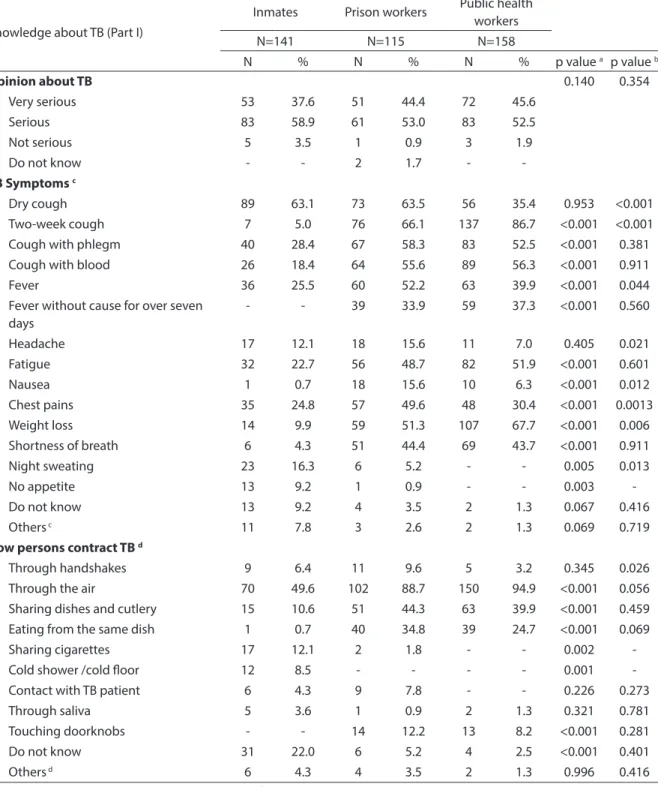

A higher proportion of prison workers than public health workers (63.5% vs. 29.8%, p<0.001) reported they had received information about TB (data not shown). According to Table 2, there were significant differences in knowledge about symptoms between inmates and prison workers, and between prison workers and public health workers. According to the inmates, TB can be transmitted by air (49.6%), by sharing cigarettes (12.1%) and by sharing cutlery (10.6%). Additionally, 22.0% were not awa-re of forms of infection. Prison workers (44.3%) and public health workers (39.9%) mentioned transmission by sharing dishes and cutlery.

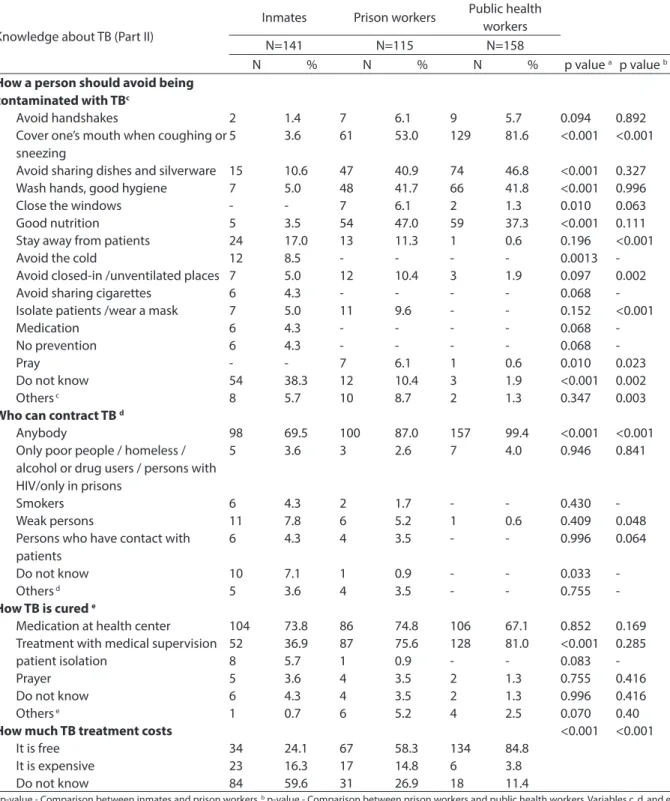

When asked “How can a person avoid

TB?” 38.3% of the inmates did not know the answer. A total of 40.9% of prison workers and 46.8% of public health workers mentio-ned “Do not share dishes or cutlery” as one of their responses (Table 3).

TB was considered a curable disease by all three categories studied. The difference

was found in the item “How to cure TB”,

when the alternative “Treatment with

me-dical supervision” was checked by 36.9% of inmates and 75.6% of prison workers (p<0.001). Only 24.1% of inmates said that the treatment for TB is provided free of char-ge. This same response was given by 58.3% of prison workers and 84.8% (p<0.001) of public health workers (Table 3).

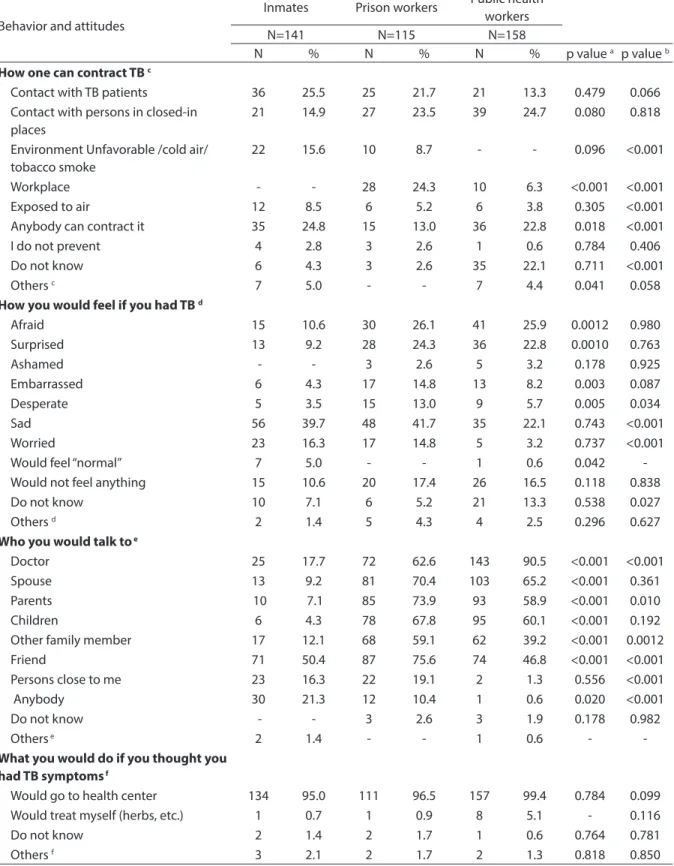

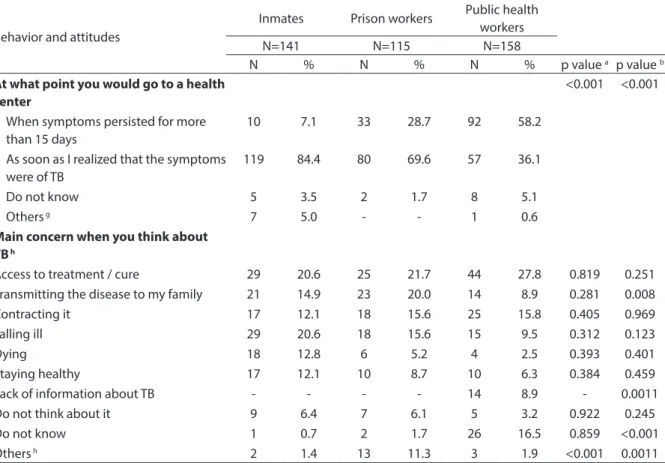

Behavior and attitudes toward the possibility of contracting tuberculosis

to be a factor that increases contamination. In this group, 22.1% could not respond “Because you can catch TB.”

One question in the KAP Questionnaire was “How would you feel if you had TB?” The objective of this question was to investigate feelings aroused by the disease. Many inma-tes answered “sad” (39.7%) and “worried”

(16.3%); while prison workers mentioned “sad” (41.7%) and “afraid” (26%); and health workers, “afraid” (25.9%) and “surprised” (22.8%).

All (100%) inmates and prison workers answered affirmatively when asked if they would talk about the disease, whereas 135 (85.4%) (p<0.001) public health workers

Table 1 - Sociodemographic characteristics and variables related to tuberculosis between prisoners, prisional unit employees and public health workers. Hortolândia, 2010.

Tabela 1 - Características sociodemográicas e variáveis relacionadas à tuberculose entre detentos, funcionários de unidade prisional e rede pública de saúde. Hortolândia, 2010.

Socio-demographic characteristics and variables related to TB

Inmates Prison workers Public health

workers

N=141 N=115 N=158

N % N % N % p value a p value b

Age (in years) <0.001 0.005

18-29 83 58.9 20 17.4 31 19.6

30-39 47 33.3 51 44.4 42 26.6

40-49 9 6.4 32 27.8 48 30.4

≥50 2 1.4 12 10.4 37 23.4

Ethnicity <0.001 0.161

White 75 53.2 91 79.1 112 70.9

Non-white 66 46.8 24 20.9 46 29.1

Gender <0.001 <0.001

Male 141 100.0 92 80.0 33 20.9

Female - - 23 20.0 125 79.1

Level of education (in years) <0.001 0.041

0-4 31 22.0 -

-5- 8 74 52.5 - - 9 5.7

9-11 34 24.1 51 44.3 64 40.5

12-16 2 1.4 54 47.0 65 41.1

≥ 17 - - 10 8.7 20 12.7

Length of work (in years) - <0.001

<1 - - 10 8.7 50 31.6

1-9 - - 69 60.0 80 50.6

10-19 - - 31 27.0 26 16.5

≥20 - - 5 4.3 2 1.3

Presence of cough with phlegm 0.0012 0.627

Yes 22 15.6 3 2.6 4 2.5

No 119 84.4 112 97.4 154 97.5

Previous or current TB treatment 0.007 0.202

Yes 19 13.5 3 2.6 1 0.6

No 120 85.1 111 96.5 157 99.4

In treatment 2 1.4 1 0.9 -

-ap-value - Comparison between inmates and prison workers. bp-value - Comparison between prison workers and public health workers

Table 2 - Knowlwdge about tuberculosis (Part I) between prisoners, prisional unit employees and public health workers. Hortolândia, 2010.

Tabela 2 - Conhecimento sobre a tuberculose (Parte I) entre detentos, funcionários de unidade prisional e rede pública de saúde. Hortolândia, 2010.

Knowledge about TB (Part I)

Inmates Prison workers Public health

workers

N=141 N=115 N=158

N % N % N % p value a p value b

Opinion about TB 0.140 0.354

Very serious 53 37.6 51 44.4 72 45.6

Serious 83 58.9 61 53.0 83 52.5

Not serious 5 3.5 1 0.9 3 1.9

Do not know - - 2 1.7 -

-TB Symptoms c

Dry cough 89 63.1 73 63.5 56 35.4 0.953 <0.001

Two-week cough 7 5.0 76 66.1 137 86.7 <0.001 <0.001

Cough with phlegm 40 28.4 67 58.3 83 52.5 <0.001 0.381

Cough with blood 26 18.4 64 55.6 89 56.3 <0.001 0.911

Fever 36 25.5 60 52.2 63 39.9 <0.001 0.044

Fever without cause for over seven days

- - 39 33.9 59 37.3 <0.001 0.560

Headache 17 12.1 18 15.6 11 7.0 0.405 0.021

Fatigue 32 22.7 56 48.7 82 51.9 <0.001 0.601

Nausea 1 0.7 18 15.6 10 6.3 <0.001 0.012

Chest pains 35 24.8 57 49.6 48 30.4 <0.001 0.0013

Weight loss 14 9.9 59 51.3 107 67.7 <0.001 0.006

Shortness of breath 6 4.3 51 44.4 69 43.7 <0.001 0.911

Night sweating 23 16.3 6 5.2 - - 0.005 0.013

No appetite 13 9.2 1 0.9 - - 0.003

-Do not know 13 9.2 4 3.5 2 1.3 0.067 0.416

Others c 11 7.8 3 2.6 2 1.3 0.069 0.719

How persons contract TB d

Through handshakes 9 6.4 11 9.6 5 3.2 0.345 0.026

Through the air 70 49.6 102 88.7 150 94.9 <0.001 0.056

Sharing dishes and cutlery 15 10.6 51 44.3 63 39.9 <0.001 0.459

Eating from the same dish 1 0.7 40 34.8 39 24.7 <0.001 0.069

Sharing cigarettes 17 12.1 2 1.8 - - 0.002

-Cold shower /cold loor 12 8.5 - - - - 0.001

-Contact with TB patient 6 4.3 9 7.8 - - 0.226 0.273

Through saliva 5 3.6 1 0.9 2 1.3 0.321 0.781

Touching doorknobs - - 14 12.2 13 8.2 <0.001 0.281

Do not know 31 22.0 6 5.2 4 2.5 <0.001 0.401

Others d 6 4.3 4 3.5 2 1.3 0.996 0.416

a p-value - Comparison between inmates and prison workers. b p-value - Comparison between prison workers and public health workers. Variables c and

d allowed for more than one response. Others (c) Diarrhea, abdominal pains, vomiting, flu, dizziness, ganglia, impotence, depression. Others (d) Drug use, kissing, contaminated food

a valor de p - Comparação entre detentos e funcionários do presídio. b valor de p - Comparação entre funcionários do presídio e rede pública de saúde. As variáveis

Table 3 - Knowledge about tuberculosis (Part II) between prisoners, prisional unit employees and public health workers. Hortolândia, 2010.

Tabela 3 - Conhecimento sobre a tuberculose (Parte II) entre detentos, funcionários de unidade prisional e rede pública de saúde. Hortolândia, 2010.

Knowledge about TB (Part II)

Inmates Prison workers Public health

workers

N=141 N=115 N=158

N % N % N % p value a p value b

How a person should avoid being contaminated with TBc

Avoid handshakes 2 1.4 7 6.1 9 5.7 0.094 0.892

Cover one’s mouth when coughing or sneezing

5 3.6 61 53.0 129 81.6 <0.001 <0.001

Avoid sharing dishes and silverware 15 10.6 47 40.9 74 46.8 <0.001 0.327

Wash hands, good hygiene 7 5.0 48 41.7 66 41.8 <0.001 0.996

Close the windows - - 7 6.1 2 1.3 0.010 0.063

Good nutrition 5 3.5 54 47.0 59 37.3 <0.001 0.111

Stay away from patients 24 17.0 13 11.3 1 0.6 0.196 <0.001

Avoid the cold 12 8.5 - - - - 0.0013

-Avoid closed-in /unventilated places 7 5.0 12 10.4 3 1.9 0.097 0.002

Avoid sharing cigarettes 6 4.3 - - - - 0.068

-Isolate patients /wear a mask 7 5.0 11 9.6 - - 0.152 <0.001

Medication 6 4.3 - - - - 0.068

-No prevention 6 4.3 - - - - 0.068

-Pray - - 7 6.1 1 0.6 0.010 0.023

Do not know 54 38.3 12 10.4 3 1.9 <0.001 0.002

Others c 8 5.7 10 8.7 2 1.3 0.347 0.003

Who can contract TB d

Anybody 98 69.5 100 87.0 157 99.4 <0.001 <0.001

Only poor people / homeless / alcohol or drug users / persons with HIV/only in prisons

5 3.6 3 2.6 7 4.0 0.946 0.841

Smokers 6 4.3 2 1.7 - - 0.430

-Weak persons 11 7.8 6 5.2 1 0.6 0.409 0.048

Persons who have contact with patients

6 4.3 4 3.5 - - 0.996 0.064

Do not know 10 7.1 1 0.9 - - 0.033

-Others d 5 3.6 4 3.5 - - 0.755

-How TB is cured e

Medication at health center 104 73.8 86 74.8 106 67.1 0.852 0.169

Treatment with medical supervision 52 36.9 87 75.6 128 81.0 <0.001 0.285

patient isolation 8 5.7 1 0.9 - - 0.083

-Prayer 5 3.6 4 3.5 2 1.3 0.755 0.416

Do not know 6 4.3 4 3.5 2 1.3 0.996 0.416

Others e 1 0.7 6 5.2 4 2.5 0.070 0.40

How much TB treatment costs <0.001 <0.001

It is free 34 24.1 67 58.3 134 84.8

It is expensive 23 16.3 17 14.8 6 3.8

Do not know 84 59.6 31 26.9 18 11.4

a p-value - Comparison between inmates and prison workers. b p-value - Comparison between prison workers and public health workers. Variables c, d, and e

allowed more than one response. Others (c) Avoid alcoholic drinks and cigarettes, avoid dust, be vaccinated, have routine exams /physical activity. Others (d) Who do not need to prevent, seniors, children. Others (e) There is no cure, medicinal herbs, rest, ventilation

a valor de p - Comparação entre detentos e funcionários do presídio. b valor de p - Comparação entre funcionários do presídio e rede pública de saúde. As variáveis c,

Table 4 - Behavior and attitudes between prisoners, prisional unit employees and public health workers in front of the possibility to catch tuberculosis. Hortolândia, 2010.

Tabela 4 - Comportamento e atitudes, diante da possibilidade de contrair a tuberculose, entre detentos e funcionários de unidade prisional e rede pública de saúde. Hortolândia, 2010.

Behavior and attitudes

Inmates Prison workers Public health

workers

N=141 N=115 N=158

N % N % N % p value a p value b

How one can contract TB c

Contact with TB patients 36 25.5 25 21.7 21 13.3 0.479 0.066

Contact with persons in closed-in places

21 14.9 27 23.5 39 24.7 0.080 0.818

Environment Unfavorable /cold air/ tobacco smoke

22 15.6 10 8.7 - - 0.096 <0.001

Workplace - - 28 24.3 10 6.3 <0.001 <0.001

Exposed to air 12 8.5 6 5.2 6 3.8 0.305 <0.001

Anybody can contract it 35 24.8 15 13.0 36 22.8 0.018 <0.001

I do not prevent 4 2.8 3 2.6 1 0.6 0.784 0.406

Do not know 6 4.3 3 2.6 35 22.1 0.711 <0.001

Others c 7 5.0 - - 7 4.4 0.041 0.058

How you would feel if you had TB d

Afraid 15 10.6 30 26.1 41 25.9 0.0012 0.980

Surprised 13 9.2 28 24.3 36 22.8 0.0010 0.763

Ashamed - - 3 2.6 5 3.2 0.178 0.925

Embarrassed 6 4.3 17 14.8 13 8.2 0.003 0.087

Desperate 5 3.5 15 13.0 9 5.7 0.005 0.034

Sad 56 39.7 48 41.7 35 22.1 0.743 <0.001

Worried 23 16.3 17 14.8 5 3.2 0.737 <0.001

Would feel “normal” 7 5.0 - - 1 0.6 0.042

-Would not feel anything 15 10.6 20 17.4 26 16.5 0.118 0.838

Do not know 10 7.1 6 5.2 21 13.3 0.538 0.027

Others d 2 1.4 5 4.3 4 2.5 0.296 0.627

Who you would talk to e

Doctor 25 17.7 72 62.6 143 90.5 <0.001 <0.001

Spouse 13 9.2 81 70.4 103 65.2 <0.001 0.361

Parents 10 7.1 85 73.9 93 58.9 <0.001 0.010

Children 6 4.3 78 67.8 95 60.1 <0.001 0.192

Other family member 17 12.1 68 59.1 62 39.2 <0.001 0.0012

Friend 71 50.4 87 75.6 74 46.8 <0.001 <0.001

Persons close to me 23 16.3 22 19.1 2 1.3 0.556 <0.001

Anybody 30 21.3 12 10.4 1 0.6 0.020 <0.001

Do not know - - 3 2.6 3 1.9 0.178 0.982

Others e 2 1.4 - - 1 0.6 -

-What you would do if you thought you had TB symptoms f

Would go to health center 134 95.0 111 96.5 157 99.4 0.784 0.099

Would treat myself (herbs, etc.) 1 0.7 1 0.9 8 5.1 - 0.116

Do not know 2 1.4 2 1.7 1 0.6 0.764 0.781

gave the same answer (data not shown). The greatest concern about TB among inmates is contracting it and how to obtain treatment and be cured. Death was mentio-ned by 12.8% of respondents in this group.

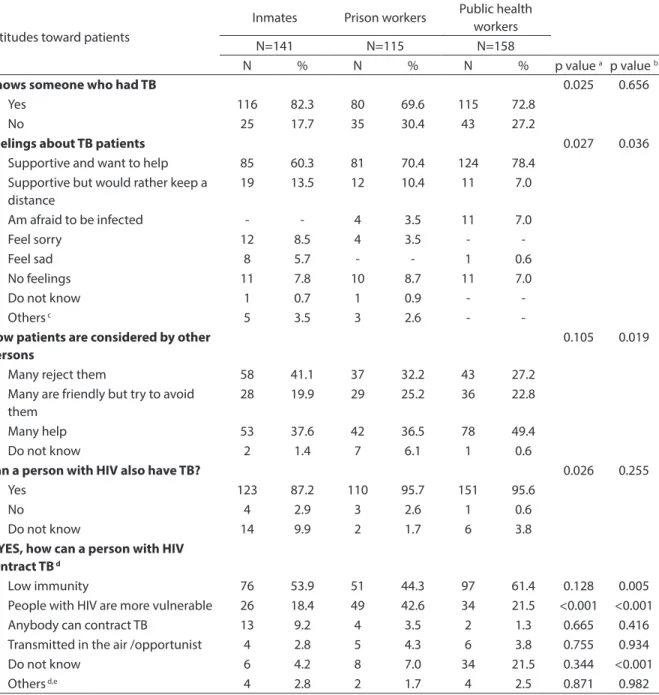

Attitudes regarding tuberculosis patients Regarding the question “How is a TB pa-tient regarded by other persons?” (see Table 5), 41.1% of inmates said that “Many people reject them.” The answer “Many people are friendly but they try to avoid patients,” was given by 25.2% of prison workers and 22.8% of public health workers.

When asked why a person who has HIV may also have tuberculosis, 44.3% of prison workers mentioned low immunity, but this same answer was given by a much greater number of public health workers (61.4%) (p = 0.005). It should be noted that 21.5% of pu-blic health workers said they “Do not know.”

Discussion

Increased drug use is one of the factors that has contributed to the increase in violence in Brazil and, consequently, to the

greater number of incarcerated persons.15

Behavior and attitudes

Inmates Prison workers Public health

workers

N=141 N=115 N=158

N % N % N % p value a p value b

At what point you would go to a health center

<0.001 <0.001

When symptoms persisted for more than 15 days

10 7.1 33 28.7 92 58.2

As soon as I realized that the symptoms were of TB

119 84.4 80 69.6 57 36.1

Do not know 5 3.5 2 1.7 8 5.1

Others g 7 5.0 - - 1 0.6

Main concern when you think about TB h

Access to treatment / cure 29 20.6 25 21.7 44 27.8 0.819 0.251

Transmitting the disease to my family 21 14.9 23 20.0 14 8.9 0.281 0.008

Contracting it 17 12.1 18 15.6 25 15.8 0.405 0.969

Falling ill 29 20.6 18 15.6 15 9.5 0.312 0.123

Dying 18 12.8 6 5.2 4 2.5 0.393 0.401

Staying healthy 17 12.1 10 8.7 10 6.3 0.384 0.459

Lack of information about TB - - - - 14 8.9 - 0.0011

Do not think about it 9 6.4 7 6.1 5 3.2 0.922 0.245

Do not know 1 0.7 2 1.7 26 16.5 0.859 <0.001

Others h 2 1.4 13 11.3 3 1.9 <0.001 0.0011

a p-value - Comparison between inmates and prison workers. b p-value - Comparison between prison workers and public health workers. Variables c, d, f and

h allowed for more than one response. Other (c) I already had TB, took drugs, God might want this. Other (d) I am predestined, I would face it, find treatment. Other (e) I would talk to God, talk with somebody I trust, would not talk to anybody. Other (f ) Would stop smoking, obtain more information, go to a drugsto-re, go to God. Other (g) When self-treatment did not work, when you are weak, would not go to a health center. Other (h) TB-MDR, to be sick and not to know it, isolation, epidemic

a valor de p - Comparação entre detentos e funcionários do presídio. b valor de p - Comparação entre funcionários do presídio e rede pública de saúde. As variáveis c, d, f, h

permitiram mais de uma resposta. Outro (c) Já tive TB, usei drogas, Deus pode querer. Outro (d) Estou predestinado, enfrentaria, procuraria tratamento. Outro (e) Falaria com Deus, falaria com quem confio, não falaria para ninguém. Outro (f) Pararia de fumar, procuraria mais informações, procuraria farmácia, procuraria Deus. Outro (g) Quando tratamento por conta não funcionasse, quando estivesse fraco, não iria ao posto. Outro (h) TB-MDR, estar doente e não saber, isolamento, epidemia.

Table 4 - Behavior and attitudes between prisoners, prisional unit employees and public health workers in front of the possibility to catch tuberculosis. Hortolândia, 2010. (continuation)

Table 5 - Attitudes from prisoners, prisional unit employees and public health workers related to sick people with TB. Hortolândia, 2010.

Tabela 5 - Atitudes em relação a doentes com TB, de detentos e funcionários de unidade prisional e da rede pública de saúde. Hortolândia, 2010.

Attitudes toward patients

Inmates Prison workers Public health

workers

N=141 N=115 N=158

N % N % N % p value a p value b

Knows someone who had TB 0.025 0.656

Yes 116 82.3 80 69.6 115 72.8

No 25 17.7 35 30.4 43 27.2

Feelings about TB patients 0.027 0.036

Supportive and want to help 85 60.3 81 70.4 124 78.4

Supportive but would rather keep a distance

19 13.5 12 10.4 11 7.0

Am afraid to be infected - - 4 3.5 11 7.0

Feel sorry 12 8.5 4 3.5 -

-Feel sad 8 5.7 - - 1 0.6

No feelings 11 7.8 10 8.7 11 7.0

Do not know 1 0.7 1 0.9 -

-Others c 5 3.5 3 2.6 -

-How patients are considered by other persons

0.105 0.019

Many reject them 58 41.1 37 32.2 43 27.2

Many are friendly but try to avoid them

28 19.9 29 25.2 36 22.8

Many help 53 37.6 42 36.5 78 49.4

Do not know 2 1.4 7 6.1 1 0.6

Can a person with HIV also have TB? 0.026 0.255

Yes 123 87.2 110 95.7 151 95.6

No 4 2.9 3 2.6 1 0.6

Do not know 14 9.9 2 1.7 6 3.8

If YES, how can a person with HIV contract TB d

Low immunity 76 53.9 51 44.3 97 61.4 0.128 0.005

People with HIV are more vulnerable 26 18.4 49 42.6 34 21.5 <0.001 <0.001

Anybody can contract TB 13 9.2 4 3.5 2 1.3 0.665 0.416

Transmitted in the air /opportunist 4 2.8 5 4.3 6 3.8 0.755 0.934

Do not know 6 4.2 8 7.0 34 21.5 0.344 <0.001

Others d,e 4 2.8 2 1.7 4 2.5 0.871 0.982

a p-value - Comparison between inmates and prison workers. b p-value - Comparison between prison workers and public health workers. Variable d allowed

for more than one response. Other (c) It is their problem, loss, discrimination, anger. Other (d) I already take the medicine, do nothing to prevent, risk of HIV

a valor de p - Comparação entre detentos e funcionários do presídio. b valor de p - Comparação entre funcionários do presídio e rede pública de saúde. A variá vel d

permitiu mais de uma resposta. Outro (c) É problema deles, perda, discriminação, raiva. Outro (d) Já toma medicamentos, não se previne, risco para HIV.

Inmates come from social classes characte-rized by poverty and difficulties in accessing health services, education and information. Consequently, this population usually has a low level of education, a characteristic also

In this study, 53.2% of the population of inmates was white, similar to the ethnic

proportion found in the city of São Paulo,16

22% having fewer than five years of educa-tion. According to the National Health Plan

for the Penitentiary System,17 the Brazilian

prison population is usually comprised of single white men under the age of 30 years. Few are literate and many had no definite profession before their arrest by the police. This means that the majority were in a si-tuation of social exclusion prior to prison. Therefore, one might consider that the pri-son population studied in Hortolândia has a higher level of formal education than the national Brazilian average, since 78% had at least five years of education.

It is a well-known fact that knowledge can influence people’s practices regarding

prevention.18 Many inmates and prison

workers had not received information about TB and several responses regarding its prevention given in the questionnaire were incorrect, as observed in studies by other

authors.19 This suggests that the forms of

communication and the strategies used to transfer knowledge in prisons fail to attain their objectives. Additionally, it indicates the absence of health education programs in general, particularly those aimed at TB

control, in prison institutions.20

In one study21 on the knowledge of the

Brazilian population about TB, 34% of the respondents reported that they were ac-quainted with someone who had the dise-ase or had previously had it. In the present study, 82.3% of inmates and 69.6% of prison workers also responded affirmatively to this same question. This result suggests that many persons in all three groups are familiar with the disease, at least to some degree. Even so, their knowledge is permeated with un-founded beliefs and mistaken information. Even many public health workers, despite their greater knowledge about TB, made basic conceptual mistakes when asked about vulnerability when sharing objects. Similar results appeared in studies on workers in

the area of nursing9 involved in family health

teams,22 although this information can easily

be found in manuals and guidelines on the Internet and in departments of

epidemio-logic surveillance.23 This fact is indicative of

deficiencies in instructions about TB provi-ded to public health workers. It also shows the serious need to disseminate informa-tion about TB among other professionals, using an interdisciplinary and intersectoral

approach.9,10 Training programs are

impor-tant strategies to increase knowledge and

practices of employees in TB tracking24 and

supervised treatment.25

Many studies that use the KAP Questionnaire fail to present the results obtained about attitudes, due to the risk of falsely generalizing the opinions and feelin-gs of a given population sector. The attempt to measure attitudes and feelings through studies has been criticized for a number of different reasons. One reason is that res-pondents tend to give answers they believe to be correct, acceptable or otherwise con-sidered relevant. More delicate questions are especially vulnerable to this tendency, and the context of an interview can strongly

influence the results.26 This situation was

present during the application of the ques-tionnaire in this study. A vague discomfort could be felt in some participants when asked certain sensitive questions, and they tended to simply respond something they thought to be correct, accepted or apprecia-ted. This behavior, for example, was noted among the inmates and prison workers for the two following questions: “How do you feel about people with TB?” and “How is a person with TB considered by others?” For the first question, the high number of inter-viewees who answered “I feel supportive and want to help,” led researchers to suspect that this was an assertion that the participants believed to be meaningful for the context of the interview, although it might not be reflecting their true attitude. To the second question, inmates answered that “Many are rejected,” while prison workers stated

that “Many people help others.” But some

the questions strange, answered them with what they felt was an appropriate answer at the moment of the interview, even if it did not reflect the truth.

With regard to how they would feel if they were infected with TB, inmates repor-ted they would feel “sad,” but this feeling could be simply associated with their condition of imprisonment and with safety- and survival-related problems, factors that would negatively affect their relationships

with other inmates.4 Prison workers and

public health workers mentioned sadness, surprise and fear. Once again, responses might not have reflected reality, but rather shown the fragility of the instrument for gathering information about attitudes. The feeling of fear is the most common cause of stigma in regard to TB.27 For Ascuntar et al.,28

this feeling is closely related to a complex set of attitudes that could interfere with the interpersonal relationships and increase risky behavior. This, in turn, might suggest the generation of stigma and discrimina-tion, thus limiting access to treatment and reducing adhesion.

Most of the inmates and prison workers expressed confidence in questionable preventive practices regarding TB, such as having good habits of cleanliness, good nutrition, washing one’s hands, avoiding the cold and not sharing dishes and cutlery. Better results from public health workers were expected in terms of their knowledge of forms of prevention, but some mentioned danger of infection from sharing dishes and cutlery. These findings are not clear in terms of what logic should be present in deciding ways to prevent infection, but they do indi-cate deficiencies in the knowledge of these individuals about the clinical and epidemio-logical management of this disease among

the studied groups.13

In regard to attitudes, the act of talking about TB and who they could talk to if they had TB, inmates mentioned the need to notify their cell mates or any other indivi-duals who might listen to them about the possibility of falling ill. This behavior can be explained in view of the fragility that TB

represents in the context of prisons.4 Patients

can put their cell mates at risk, and talking about the disease could lead these cell mates to pressure to have the patients transferred in order to lower the chances of infecting others and speed up access to the prison health service. Prison workers reported that they would talk about the disease to a friend or family member, while public health workers would talk to a doctor and relatives. This difference in findings reflects a relationship between knowledge about TB and access to

health services.18

Another source of uncertainty is that the data obtained from KAP studies are often used to plan activities focused on behavio-ral changes related to certain health issues, based on the false premise that there is a direct relationship between knowledge and behavior. A number of studies have shown that knowledge is only one of the factors that influence practice. Therefore, for there to be changes in behavior, health programs must join socioeconomic, environmental and structural factors with practices when

planning prevention programs.18

Conclusion

In the present study, the use of the KAP questionnaire presented a number of pro-blems, difficulties and drawbacks. It proved to be weak to interpret the data gathered on attitudes, thus hindering the understanding of the information obtained. Therefore, if the objective is to study behavior, practice and attitudes in regard to a given context, combinations of qualitative and quantitative methods would be more indicated.

References

1. Dara M, Grzemska M, Kimerling ME, Reyes H, Zagorskiy A. Guidelines for control of tuberculosis in prisons. Tuberculosis Coalition for Technical Assistance and International Committee of the Red Cross. 2009. Disponível em: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/

PNADP462.pdf. [Accessed in August 18th 2011]

2. Bick JA. Infection control in jail and prisons. Clin Infect

Dis 2007; 45(8): 1047-55.

3. Hanau-Berçot B, Grémy I, Raskine L, Bizet J, Gutierrez MC, Boyer-Mariotte S et al. A one-year prospective study (1994-1995) for a first evaluation of tuberculosis

transmission in French prisons. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis

2000; 4(9): 853-9.

4. Diuana V, Lhullier D, Sánchez AR, Amado G, Araújo L, Duarte AM, et al. Saúde em prisões: representações e práticas dos agentes de segurança penitenciária no Rio

de Janeiro, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública 2008; 24: 1887-96.

5. Jittimanee XS, Nateniyon S, Kittikraisak W, Burapat C, Akksilp S, Chumpathat N et al. Social stigma and knowledge of tuberculosis and HIV among patients

with both diseases in Thailand. PLoS One 2009; 23: 4(7):

e6360.

6. Baral SC, Karki DK, Newell JN. Causes of stigma and discrimination associated with tuberculosis in Nepal: a

qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2007; 7: 211.

7. Pôrto A. Representações sociais da tuberculose: estigma

e preconceito. Rev Saúde Pública 2007; 41(1): 43-9.

8. Goffman E. Estigma. Notas sobre a manipulação da

identidade deteriorada. 2ªed. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar

Editores; 1978.

9. Souza NJ, Bertolozzi MR. A vulnerabilidade à tuberculose em trabalhadores de enfermagem em um

hospital universitário. Rev Latino-am Enfermagem 2007;

15(2): 259-66.

10. Alvarez-Gordilho GC, Alvarez-Gordilho FJ, Dorantes-Jiménez JE, Halperin-Frish D. Percepciones y prácticas relacionadas com la tuberculosis y la aderência al

tratamiento em Chiapas, México. Salud Pública Méx

2000; 42(6): 520-8.

11. Savicevic AJ, Popovic-Grle S, Milovac S, Ivcevic I, Vukasovic M, Viali V et al. Tuberculosis knowledge among patients in out-patient settings in Split, Croatia.

Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008; 12(7): 780-5.

12. World Health Organization. Advocacy, communication

and social mobilization for TB Control. A guide to developing knowledge, attitude and practice surveys. WHO/HTM/STB/2008.46.

13. Launiala A. How much can a KAP survey tell us about people’s knowledge, attitudes and practices? Some observations from medical anthropology research on

malaria in pregnancy in Malawi. Anthropology Matters

2009; 11(1): 1-13.

14. Roy A, Abubakar I, Yates S, Chapman A, Lipman M, Monk P et al. Evaluating knowledge gain from TB leaflets for prison and homeless sector staff: the National

Knowledge Service TB pilot. Eur J Public Health 2008:

18(6): 600-3

15. Brasil. Ministério da Justiça – Execução Penal. Sistema Prisional. Infopen - Estatística. Available in: http://portal.mj.gov.br/data/Pages/ MJD574E9CEITEMIDC37B2AE94C6840068B1624

D28407509CPTBRIE.htm. [Accessed in August 20th 2011].

16. Abrahão RMCM. Diagnóstico da tuberculose na

população carcerária dos Distritos Policiais da zona oeste

da cidade de São Paulo [tese de doutorado]. São Paulo:

Faculdade de Saúde Pública da USP; 2003.

17. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Plano Nacional de Saúde no Sistema Penitenciário. Available in: http://bvsms. saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/plano_nacional_saude_

sistema_penitenciario_2ed.pdf. [Accessed in August 20th

2011]

18. Launiala A, Honkasalo ML. Ethnographic study of factors influencing compliance to intermittent preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy

among Yao women in rural Malawi. Trans R Soc Trop

Med Hyg 2007; 101(10): 980-9.

19. Abebe DS, Biffa D, Bjune G, Ameni G, Abebe F. Assessment of knowledge and practice about

tuberculosis among eastern Ethiopian prisoners. Int J

Tuberc Lung Dis 2011; 15(2): 228-33.

20. Waisbord S. Participatory communication for

tuberculosis control in prisons in Bolivia, Ecuador, and

Paraguay. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2010; 27(3): 168-74.

21. Boaretto MC, Guimarães MTC, Natal S, Castelo Branco AC, Mondarto P, Fernandes MJ et al. The knowledge of

the Brazilian population on tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc

Lung Dis 2010; 14(11): S196.

22. Maciel ELN, Vieira RCA, Milani EC, Brasil M, Fregona G, Dietze R. O agente comunitário de saúde no controle da

tuberculose: conhecimentos e percepções. Cad Saude

Publica 2008; 24(6): 1377-86.

23. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Tuberculose - Guia de vigilância epidemiológica, 2005. Available in: http:// www.prosaude.org/publicacoes/guia/Guia_Vig_Epid_

novo2.pdf. [Accessed in April 24th 2011].

Acknowledgements: Project ICOHRTA AIDS/TB-Brazil, for the course held at Johns

24. Naugthon MP, Posey DL, Willacy EA, Comans TW. Tuberculosis training on physicians who perform

immigration medical examination. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis

2010; 14(11): S154.

25. Rao N, Arain I. Knowledge regarding tuberculosis among

TN course participants in Karachi. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis

2010; 14(11): S160.

26. Hausmann-Muela S, Ribera JM, Nyamongo I. Health seeking behavior and the health system response. DCPP Working Paper 2003. Available in: http://www.dcp2.org/

main/Home.html. [Accessed in April 24th 2010].

27. Courtwright A, Turner AN. Tuberculosis and

stigmatization: pathways and interventions. Public

Health Rep 2010; 125(4): 34-42.

28. Ascuntar JM, Gaviria MB, Uribe L, Ochoa J. Fear, infection and compassion: social representations of

tuberculosis in Medellin, Colombia, 2007. Int J Tuberc

Lung Dis 2010; 14(10): 1323-29.