B

IRDS OFTWOPROTECTED AREASIN THESOUTHERNRANGE OFTHEB

RAZILIANA

RAUCARIAFORESTI

SMAELF

RANZ1,2,5M

ARCELOP

EREIRADEB

ARROS1L

AURAC

APPELATTI3R

ENATOB

OLSOND

ALA-C

ORTE3P

AULOH

ENRIQUEO

TT4ABSTRACT

Over 70% of threatened birds in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, south Brazil, inhabit forest environments. The creation and maintenance of protected areas is one of the most important measures aiming to mitigate these problems. However, the knowledge of the local biodiversity is essential so that these areas can effectively preserve the natural resources. Between 2004 and 2009 we sampled the avifauna in two conservation units in Rio Grande do Sul: Flo-resta Nacional de Canela (FNC) and Parque Natural Municipal da Ronda (PMR), both representative of the Mixed Humid Forest (Araucaria Forest). A total of 224 species was recorded, 116 at FNC and 201 at PMR, ten of which threatened regionally: Pseudastur polionotus, Odontophorus capueira, Patagioenas cayennensis, Amazona pretrei, A. vi-nacea, Triclaria malachitacea, Campephilus robustus, Grallaria varia, Procnias nudicol-lis and Sporophila melanogaster. Richness and species composition seem to be related to different stages of forest conservation, to size and connectivity, as well as to the diversity of environments. The better conservation of PMR compared to FNC, allied to its geographic position, results in a richer avifauna, with a larger amount of rare and endangered species, as well as species sensitive to disturbance and endemic to the Atlantic Rainforest. We suggest management actions aiming the conservation and the long-term recovery of natural environ-ments at these sites.

Key-Words: Atlantic Forest; Avifauna; Conservation units; Floresta Ombrófila Mista; Rio Grande do Sul.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0031-1049.2014.54.10

1. Laboratório de Zoologia, Universidade Feevale. Rodovia RS-239, 2755, Vila Nova, CEP 93352-000, Novo Hamburgo, RS, Brasil. 2. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS).

Avenida Bento Gonçalves, 9500, Agronomia, CEP 91501-970, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. 3. Programa de Pós-graduação em Ecologia, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS).

Avenida Bento Gonçalves, 9500, Agronomia, CEP 91501-970, Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil. 4. Universidade Estadual do Rio Grande do Sul (UERGS) – Unidade do Litoral Norte.

INTRODUCTION

Rio Grande do Sul is one of the states in Bra-zil with the best knowledge of its avian composition, with a record of 661 species (Bencke et al., 2010). About 20% of these species are regionally threatened (Marques et al., 2002); almost 70% (n = 81) of which live in forest environments (Bencke et al., 2003). Hab-itat loss and degradation are the main threats to most of these species. Among the priority actions to mini-mize such conservation concerns are environmental protection and habitat recovery (Fontana et al., 2003).

The designation of legally protected areas is an important measure for the conservation of biodi-versity (Primack, 1998; Balmford et al., 2003; Mc-Donald & Boucher, 2011), considering that human intervention can significantly affect biological com-munities, frequently causing habitat loss or fragmen-tation. Although species list in protected areas is one of the initial and most relevant procedures for the maintenance of natural resources (Wilson, 1997), many Conservation Units (CUs) in Brazil do not have biological surveys. Such is the case of Floresta Nacional de Canela and Parque Natural Municipal da Ronda, both located in São Francisco de Paula, RS. The first one is a national park created in 1946 by the former Instituto Nacional do Pinho (INP) and is historically based on regional forestry (Ferraz, 2003). The latter is a municipal park, founded 50 years later (Municipal Decree No. 1761, February 29th, 1996),

that is still in need of effective actions on land regular-ization and restoration. There are no previous formal studies about its avifauna.

These two CUs are important remnants of the Araucaria forest. This typical forest of southern Brazil had already been reduced to less than 4% of its origi-nal cover by the 1990’s (Leite & Klein, 1990) and it is on the verge of disappearing (Sonego et al., 2007). The forest remnants are distributed discontinually, forming a mosaic of patches in different sizes and forms, generally sparse and disconnected, located in sites with a difficult access. Additionally, several for-ests in this plateau were altered and had their original floristic composition impoverished, mainly by the ex-traction of its main element, the Brazilian Pine A. an-gustifolia.

Despite being focus of a considerable amount of studies, there are very few published bird surveys for the Araucaria plateau in Rio Grande do Sul. When studying the avifauna through an altitude gradient in the Atlantic coast of the state, Bencke & Kindel (1999) sampled an area going from the sea level up to 1000 m, including the region of São Francisco

de Paula. This can be considered the most complete study on bird diversity covering an area from the slope and lowlands to the uplands along the state of Rio Grande do Sul. In addition, the biological invento-ries in three protected areas of the state are impor-tant references, which include the vegetation found in the slopes and lowlands. These studies include a preliminary survey conducted by Parker III & Goerck (1997) at Parque Nacional dos Aparados da Serra and the published management plans of Parque Estadual do Tainhas (SEMA, 2008a), Reserva Biológica Estadual da Serra Geral (SEMA, 2008b) and Centro de Pesquisas e Conservação da Natureza Pró-Mata (PUCRS, 2011). Moreover, Fontana et al. (2008) presented a synthesis of the avifauna at the Campos de Cima da Serra region across the states of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Ca-tarina, southern Brazil.

Aiming to contribute to the knowledge of avian diversity in protected areas of Rio Grande do Sul, bird surveys were carried out in two conservation units in the state: Floresta Nacional de Canela and Parque Natural Municipal da Ronda. The avifaunas were evaluated according to the local geographic and en-vironmental characteristics, as well as to the current conservation status of the protected areas. In addition, we bring information on the poorly known, rare or endangered species in the region and propose a list of management measures.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study sites

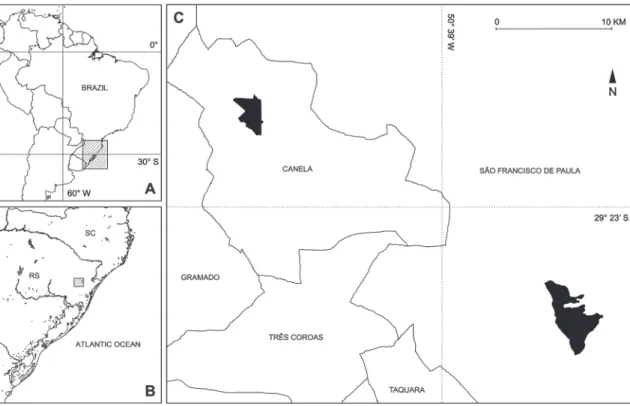

Floresta Nacional de Canela (FNC; 29°19’S, 50°48’W) is located in the city of Canela, 4 km away from the urban area (Fig. 1). With an average altitude of 820 m, the CU has a total area of 517 ha, among na-tive vegetation and Araucaria angustifolia, Pinus spp. and Eucalyptus spp. plantations. There are a few non-forested sites, such as cut stands in regeneration (at different stages of succession), surrounded by recre-ational and inhabited areas, and three artificial lakes, bordered in part by small wetlands. However, natural grasslands and wetlands of large extent are absent. The following tree species are the most representative: A. angustifolia, Casearia decandra, Blefarocalix salici-folius, Zanthoxylum rhoifolium, Podocarpus lambertii and Acca sellowiana.

The altitude varies between 400 and 930 m, with most of the area at the higher part. The park covers 1,200 ha, with a forest matrix and only about 60 ha of open areas (wetlands and semi-natural grasslands used for cattle grazing). The largest part of the park is situated in the Araucaria forest region and has ele-ments of the Semidecidual Seasonal Forest in the low-est altitudes and steep slopes, where the Brazilian Pine is absent (Teixeira et al., 1986). Some representative species of the local flora are Myrceugenia mesomischa, Ilex microdonta, I. paraguariensis, Piptocarpha angusti-folia, Mimosa scabrella, Matayba elaeagnoides and Sloa-nea monosperma (Cappelatti & Schmitt, 2011).

Both areas are part of the Araucaria plateau and are 27 km apart. According to the most recent climate classification for Rio Grande do Sul (Maluf, 2000), São Francisco de Paula fits in the category of Super-humid Temperate climate (“TE SU”), with an annual mean temperature of 14.4°C and the highest annual precipitation of the state (average 2,162 mm). In the region of Canela, the predominant climate type is the Perhumid Temperate (“TE PU”), with an annual mean temperature of 16°C and an average annual pre-cipitation of 1,821 mm (IPAGRO, 1989). Rainfall is present throughout the year and winter frosts are fre-quent (Moreno, 1961).

Sampling methods

Our thirty-five expeditions took place between March 2004 and May 2009, lasting from one to four days each: 21 (51 days) at FNC and 14 (32 days) at PMR (Table 1), in all seasons. There was a total of 117 hours of fieldwork at FNC and 59 h at PMR, with one or eventually two observers. The bird sur-vey was based on qualitative samples, through visual observations (with 7 × 35 binoculars) and recogni-tion of vocalizarecogni-tions (recorded when necessary with a digital recorder and a directional microphone). Cop-ies of these recordings will be deposited at the Ma-caulay Library (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York). The observations were preferably made in the morning (from dawn to 10 h) and in the evening (from 16 h to sunset), sometimes at night, especially at FNC. There were some occasional captures with a continuous track of three to six mist nets (14 × 3 m, 15 and 36 mm of mesh), arranged in different envi-ronments at the CUs, especially in the forest matrix. The capture effort at FNC was of 308 h/net, during six expeditions, and once at PMR. Records obtained only in the vicinities of the study areas (< 5 km dis-tant from the borders) during the expeditions were not included in the species list, but are discussed when relevant.

Sources and avifaunal descriptors

The threat status of the species was consulted in Marques et al. (2002) at a regional scale (RS), Silveira & Straube (2008) at a national scale and IUCN (2012) at a global scale. The birds were fit-ted in three levels according to sensitivity to habitat disturbance (low, medium or high) following Parker III et al. (1996), when possible. Furthermore, the At-lantic Forest endemics are cited according to Brooks et al. (1999). Scientific and common nomenclatures followed CBRO (2014) and Bencke et al. (2010), re-spectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of the avifaunas

We recorded 226 bird species at both CUs (Ap-pendix), which represents 34% of the regional avi-fauna (Bencke et al., 2010). PMR had more species (n = 201) than FNC (n = 166), although PMR had more exclusive species (n = 60; n = 25). The analysis of the collector’s curve (Fig. 2) reveals an approxima-tion to stabilizaapproxima-tion for both sites. According to Bel-ton (1994), who sampled birds throughout the state of Rio Grande do Sul during the 1970’s, 250 is prob-ably the highest number of species any region can host, due to a variety of short-range species and to the fragmentation and discontinuity of their preferred habitats. The total number of species recorded at FNC and at PMR is similar to that from other stud-ies in medium to large-sized South Brazilian forests, which normally find 150 to 200 species. Bird richness in the previously mentioned CUs from the northeast

Rio Grande do Sul are: Parque Estadual do Tainhas (n = 132) (SEMA, 2008a), Reserva Biológica Estadual da Serra Geral (n = 172) (SEMA, 2008b) and Cen-tro de Pesquisas e Conservação da Natureza Pró-Mata (n = 215) (PUCRS, 2011).

The Passeriformes Suboscines/Oscines ratio was similar between sites (ca. 55/45% or 1.1:0.9 in both CUs). It is known that Suboscines (Tyranni) are mostly forest birds, whereas Oscines (Passeri) prefer open environments and forest edges (Willis, 1979; Haffer, 1985; Sick, 1997). This could explain why the Suboscines species were found primarily in sites with a forest matrix. At FNC, Pinus and Eucalyptus plan-tations cause severe edge effects throughout the park area, which would explain the presence of a higher percentage of Oscines passerines. Forests at PMR are larger, more continuous and better preserved. None-theless, there are also grasslands and wetlands, which are typical habitats for several Oscines species, e.g., Ammodramus humeralis, Emberizoides ypiranganus, Sporophila melanogaster and Pseudoleistes guirahuro. As a result, even though both CUs are notoriously differ-ent in several aspects such as forest conservation status and presence of open sites, these distinct characteris-tics bring a balance of environmental conditions that cause the similar Passeriformes Suboscines/Oscines ratio.

The Araucaria forest province, in which FNC and PMR are inserted, is historically related to the Brazilian Atlantic Forest province, especially in its highest altitudes at the southern and southeastern portions (Morrone, 2001; Straube & Di Giacomo, 2007). Atlantic endemisms are well represented in highland forests. Although notably conspicuous in several aspects, the region that goes northwards the south scarp’s margin is sometimes considered only a TABLE 1: Expedition dates for the bird survey at the Floresta Nacional de Canela (FNC) and at the Parque Natural Municipal da Ronda (PMR), Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

MONTH DATES – FNC DATES – PMR

2004 2005 2006 2007 2007 2008 2009

JAN — — 16, 17, 18 and 19 — 05, 06 and 07 — 23, 24 and 25

FEB — — — — — — 13, 14 and 15

MAR 06, 07 and 08 18 04, 05, 06, 25, 26 and 27 — 16, 17 and 18 04, 05, 15 and 16 28 and 29

APR 21 16 and 17 21, 22, 23 and 24 — — — —

MAY 22, 23 and 24 — 07, 08, 25 and 26 19 and 20 — 17 and 18 —

JUN — — — — — 14 —

JUL 04 and 05 14, 15 and 16 — — — — —

AUG — 26 — — — — —

SEP — 10 and 11 — — 29 and 30 13 and 14 —

OCT — 28, 29 and 30 21 and 22 — — 13 and 14 —

NOV — — 06 and 07 — 10 and 11 — —

“hilly” extension of the coastal Atlantic Forest (Haffer, 1985). In this study we found that 23% of recorded species at FNC and PMR are endemic to the Atlantic Forest, with a few elements from the plateau, such as the species Drymophila malura, Heliobletus contami-natus and Hemitriccus obsoletus. According to Bencke et al. (2009), in some areas of the northeastern Rio Grande do Sul the avifauna may contain up to 41% of endemic species from that zoogeographic region. Bencke & Kindel (1999) found 26.5% of endemic birds in the extreme northeast of the state and con-cluded that this area is the biogeographic limit for those species. In our study, several species are consid-ered typical from the Araucaria forest province, e.g., Amazona pretrei, A. vinacea, Mackenziaena leachii, Leptasthenura setaria, L. striolata, Phyllomyias vires-cens, Emberizoides ypiranganus, Poospiza cabanisi and Saltator maxillosus (Straube & Di Giacomo, 2007). Nonetheless, the limits between these zones ( Araucar-ia forest and lowland Atlantic Forest) do not seem to be very well defined, nor are spatially distinguished.

The lower specific richness at FNC compared to PMR may be related to a few variables. The most important ones are probably the larger area and the more pronounced altitudinal gradient at PMR. Other important characteristics of this CU possibly include the greater habitat heterogeneity, proximity to coastal forests, distinct surroundings and a better conserva-tion status (described below). On the other hand, FNC has less diversity of typical environments, such

as grasslands and wetlands, which house several exclu-sive bird species. For example, Heterospizias meridi-onalis was recorded only nearby FNC, in a managed field (grassland matrix) close to Saiquí stream, 3.5 km away from the CU, whereas it was found at PMR, in dry grasslands. For the same reason, some species con-sidered common in the uplands were not recorded at FNC, e.g., Ammodramus humeralis, Volatinia jacarina, Donacospiza albifrons, Nothura maculosa, Pardirallus sanguinolentus, Pseudoleistes guirahuro, Laterallus mel-anophaius and Emberizoides ypiranganus, all of which species that inhabit grasslands, pastures and wetlands. For having some small areas of grasslands and “grava-tá/eryngos” (Eryngium pandanifolium) wetlands, even when slightly altered, PMR hosts several species that are exclusive to these environments.

Many species that depend on well-preserved for-ests and could occur at FNC based strictly on their geographical distribution were not recorded during this study. Wood extraction, although selective, par-tially suppresses and changes vegetation, causing a negative impact on sensitive species or guilds such as large frugivores (Pizo, 2001) and understory/ground insectivores (Aleixo, 1999). Examples of species from each of these guilds are the Hooded Berryeater ( Car-pornis cucullata) and the Variegated Antpitta ( Gral-laria varia), respectively. Although speculative, the scarcity of large areas with a preserved understory for these species – and others with similar ecological characteristics – to occur at FNC may justify their ab-sence. In this CU, the fragments of native forest alto-gether account for 128 ha, interspersed with patches destined to forestry. In addition, there are 130 ha of Araucaria trees with an understory at several differ-ent successional stages, whereas the remaining area (ca. 145 ha, excluding open and human impacted ar-eas) is characterized by Pinus spp. and Eucalyptus spp. plantations (IBAMA, 1989). The largest continuous forest with the prevalence of Araucaria trees has only 32 ha, with a medium to advanced degree of fragmen-tation. Contrarily, the forest at PMR is mostly con-tinuous throughout the park and connects itself with surrounding forest areas. The latter also has a more homogeneous, late-secondary forest, often resembling a primary forest (e.g., in slopes, where there can be found Variegated Antpittas, Hooded Berryeaters and Bare-throated Bellbirds)

Another possible driver of the bird composition and distinctiveness among these CUs is the distance to the Atlantic slope: FNC is located more to the west than PMR and other CUs such as Floresta Nacional de São Francisco de Paula and Centro de Pesquisas e Conservação da Natureza Pró-Mata. This geographical FIgURE 2: Species accumulation curve for the bird survey at the

position, combined with the fact that its altitude does not vary as much as PMR, makes FNC lack certain Atlantic elements, such as species partly dependent on the forest, which approximate and enter the slopes. On the other hand, PMR reaches almost 400 m above sea level (at the extreme south of the park) and pres-ents distinct vegetation types, with some elempres-ents of the seasonal forest. This characteristic seems to be one of the factors involved in the absence or low frequency of Euphonia pectoralis, Dacnis cayana (Blue Dacnis) and Carpornis cucullata at the FNC, all of which oc-cur at PMR.

Bencke & Kindel (1999) mentioned some cases of an apparent altitudinal substitution of congeners or ecologically similar species. Two examples are Pi-cumnus temminckii (Ochre-collared Piculet) and P. nebulosus (Mottled Piculet), occurring in higher altitudes and in lowlands and slopes, respectively. In this study, we recorded P. temminckii only along the slope at PMR, whereas P. nebulosus was recorded in the highlands at both sites. Further, according to these authors, it seems that the ecotones between the main forest types may play a major role in defining the alti-tudinal limits of the bird distribution at the southern range of the Atlantic forest. However, more studies are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

The low richness of raptors at FNC, especially from the Accipitridae family (two species, as opposed to 10 at PMR), might be associated to the reduced and impoverished forest cover inside and surrounding the CU, as mentioned for other groups. In general, these birds require large areas for feeding and repro-duction (Willis, 1979; Bildstein et al., 1998). Al-though Elanoides forficatus (Swallow-tailed Kite) may cross open areas and small forest patches, it prefers to fly in groups above the forests, especially across steep slopes (Belton, 1994), where it was observed at PMR but not at FNC. Harpagus diodon (Rufous-thighed Kite) was recorded only at PMR in tall, steep for-ests. At Centro de Pesquisas e Conservação da Natureza Pró-Mata, which comprises an area of 4,500 ha, 22 species of Falconiformes occur, including large forest hawks such as Black Hawk-Eagle (Spizaetus tyrannus) (Mähler-Jr. & Fontana, 2000; Joenck, 2006). This species was recorded in 24 May 2009, in the morning, near the river Rolantinho da Areia (M.F.B. dos Santos, in litt.) proximate to PMR, indicating that those for-ests are used by this endangered species.

Strictly aquatic birds, which require water bod-ies to feed on, such as ducks and grebes, occur mostly at FNC. Three water reservoirs with small islands surrounded by vegetation offer the resources that at-tract species such as Podylimbus podiceps (Pied-billed

Grebe), Amazonetta brasiliensis (Brazilian Teal), Den-drocygna viduata (White-faced Whistling-Duck), Megaceryle torquata (Ringed Kingfisher), Chloroceryle amazona (Amazon Kingfisher), C. americana (Green Kingfisher), Gallinula melanops (Spot-flanked Galli-nule) and even Chauna torquata (Southern Screamer), all absent at PMR. These artificial lakes have 0.3, 2.7 and 3.6 ha and were created in 1997, 1997 and 1968, respectively. Large groups of Common Gallinule (Gallinula galeata) breed nearby the largest reservoir. Some individuals of Ciconia maguari (Maguari Stork) and Ardea cocoi (Cocoi Heron) were observed above PMR flying northwards, where there is a 6 ha water reservoir and some large flooded areas.

Due to the low sampling effort, mist net cap-tures did not contribute directly to the bird survey, since no species was recorded exclusively through this method. Nonetheless, at FNC this type of sam-pling was an important tool in the identification of cryptic species (e.g., young Turdus, Elaenia spp.) and to better characterize the occurrence and seasonal-ity patterns of some species. Two capture events are noteworthy: 15 individuals of T. subalaris (Easter Slaty Thrush) in only three mist nets during three days in December 2005 and six Haplospiza unicolor (Uniform Finch) in two days, in January and Feb-ruary 2006 (dozens of birds were heard at the same point), although only when the bamboo Merostachys aff. skvortzovii was fruiting. This species fruits every 31-33 years, and the most recent event was observed in Rio Grande do Sul in 2005 and 2006 (Sendulsky, 1995; Schmidt & Longhi-Wagner, 2009). At PMR, Uniform Finches were recorded only in January 2007, when two individuals were unexpectedly seen flying among shrubby grasslands, possibly searching for fruiting bamboos (see Vasconcelos et al., 2005). Belton (1994) called attention to the ringing of eight individuals in Gramado, a neighboring city of Cane-la, more than thirty years ago (10 December 1975) and considered this an expressive number comparing to the usual capture frequency during his ringing ses-sions.

both with constant release records from the CETAS. However, in the case of these species, the birds were displaying a rather friendly behavior during some of the observations.

There were other bird releases at the FNC that almost certainly resulted in death. That was probably the fate for the species that do not use the habitats at FNC or have their distribution far from that re-gion (e.g., Paroaria coronata, Sporophila nigricollis and S. angolensis). The practice of releasing birds from captivity, which is usual in some Brazilian CUs, is not recommended, except in specific study cases. The Bra-zilian Ornithological Society (SBO) does not support this activity (more information on Efe et al., 2006).

Species sensitivity to habitat disturbance and endemism

We were able to fit 220 species into some level of sensitivity to disturbance, according to Parker III et al. (1996): 162 at FNC and 196 at PMR (Appen-dix). Among these, 117 (53%), 88 (40%) and 15 (7%) were classified in the categories of low, medi-um and high sensitivity, respectively. At FNC, these numbers were 88 (54%), 67 (42%) and seven (4%). Thus, FNC appears to have fewer ecological require-ments to maintain highly sensitive species than PMR (7 vs. 4%). For example, sensitive forest species such as Spot-winged Wood-Quail (Odontophorus capueira), Mantled Hawk (Pseudastur polionotus) and Variegated Antpitta (Grallaria varia) were recorded exclusively at PMR.

Fifty-one species (23%) are endemic to the At-lantic Forest (sensu Brooks et al. 1999), 50 at PMR and 37 at FNC (Appendix).

Noteworthy records

Turdus leucomelas was seen and photographed foraging in a recreational area at FNC in May 24, 2004. This species has been expanding its distribu-tion in Rio Grande do Sul since the 1990’s (Bencke & Grillo, 1995) and today it occupies several regions in the state (Accordi & Barcelos, 2006; Bencke et al., 2007, Franz & Bencke, in prep.). This is its first record for the highlands of Rio Grande do Sul.

The Striped Owl (Asio clamator) was observed at FNC on December 20, 2005. This was an unexpected record, considering the distribution of this species is mostly along the coast and east of the central low-lands, only in the base of the scarp (Belton, 1994).

Ten species recorded in the CUs are under some threat of extinction at a local level (RS, sensu Bencke et al., 2003). Three of them (Amazona pretrei, A. vina-cea and Procnias nudicollis) are also cited in the official Brazilian List of Threatened Fauna Species (BR, sensu Silveira & Straube, 2008) or mentioned in the global IUCN Red List (2012, GL). In addition, ten species are also considered near threatened (NT) worldwide (IUCN, 2012) (Appendix). The codes in parenthesis are also labeled on the Appendix.

Pseudastur polionotus (EN-RS, NT-GL) – In Septem-ber 14, 2008 an individual, possibly male due to its size (the first author has experienced observations of this species in several occasions elsewhere), was ob-served from a long distance during 20 s. It flew from the ground up to a tall tree, in a trail near the west border of the PMR, nearby the Oito Cachoeiras pri-vate park.

Odontophorus capueira (VU-RS) – On March 16, 2007, in a forest dense with Araucaria angustifolia at PMR, by nightfall, it was possible to hear at least four distinct individuals of the Spot-winged Wood Quails vocalizing. This species is seen throughout the plateau scarp, although only in large forest remnants (Bencke et al., 2003).

Amazona pretrei (VU-RS, VU-BR, VU-GL) – Scarce records at both FNC and PMR. Typically flying in pairs or groups of up to 10 individuals. In March 07, 2004, a juvenile and an adult were seen feeding on Podocarpus lambertii in an open area at FNC. In May 23, 2004, a pair flew by FNC. Although Varty et al. (1994) have highlighted FNC as a potentially impor-tant site for this species, nesting and roosting sites of Red-spectacled Parrots were not observed in the pres-ent study. Thus, it is possible that the species only uses FNC as a “stepping stone” or as an occasional feed-ing site. At PMR, in the evenfeed-ing of September 29, 2007, 10 individuals were seen crossing the grassland towards the Eucalyptus forest located north outside the park, where they passed the night. Today A. pre-trei is found throughout most of the Araucaria plateau (Bencke et al., 2003).

groups (Amazona spp., Pionus maximiliani [Scaly-headed Parrot] and Pyrrhura frontalis [Maroon-bel-lied Parakeet]). On January 18, 2006, an individual of A. vinacea was heard and later seen at the canopy of an Araucaria, in an open site nearby the buildings at FNC. At PMR, on January 06, 2007, three of them were observed flying over the Araucaria forest and on 15 March 2008 the vocalization of four individuals was recorded. In the Araucaria plateau this species is found at the top of the northeast slope as well as throughout the Campos de Cima da Serra physiogno-my (Bencke et al., 2003).

Triclaria malachitacea (VU-RS, NT-GL) – Record-ed only at PMR, where it seems to be abundant in well-preserved forests. On September 13, 2008, a fe-male was observed resting on a Mimosa scabrella tree, which later vocalized its characteristic whistles while entering the forest. On September 14, 2008, a couple was seen feeding on Myrceugenia mesomischa fruits during ca. 8 min. A recording was obtained on 28 March 2009. This species occurs mostly throughout the slopes, from 100 to 1000 m above sea level, and breeds in primary forests (Bencke et al., 2003). The forests at PMR apparently have conditions suitable to the maintenance of these populations, which in sev-eral occasions were recorded throughout the day.

Campephilus robustus (EN-RS) – Robust Woodpeck-er is usually associated with large forest remnants or areas with a significant forest cover (Belton, 1994; Bencke et al., 2003). It is mainly distributed across the northern and northeastern plateau, with records in the northwestern and medium plateau and in south-ern regions (Bencke et al., 2003, Agne et al., 2007). On November 07, 2006, a female was observed forag-ing the area ‘1’ (18 ha), on top of Araucaria angustifo-lia and other dead trees, at FNC. On May 17, 2008 two strong thumps, characteristic of this species, were heard in the interior of the Dense Humid Forest at PMR. Furthermore, there are records of this species at the following protected areas in the state: Turvo, Es-pigão Alto and Rondinha state parks, Centro de Pesqui-sas e Conservação da Natureza Pró-Mata, as well as at the national forests of São Francisco de Paula (Bencke et al., 2003) and Passo Fundo (Agne, 2005).

Grallaria varia (VU-RS) – On May 28, 2009, dur-ing nightfall, Variegated Antpittas began vocalizdur-ing in the hills of the Mixed Humid Forest, at PMR. From the same observation point, four vocalizing individu-als were identified. In the state, this species is found throughout the plateau (Bencke et al., 2003).

Procnias nudicollis (EN-RS, VU-GL) – At FNC only one record was obtained, at site ‘7H’ (15 ha), on No-vember 06, 2006. At PMR, this species is abundant during the spring and summer, when numerous indi-viduals were heard. According to Bencke et al. (2003), this species is today confined to the top of Serra Geral, where the largest continuum forests are found in the state.

Sporophila melanogaster (VU-RS, VU-BR, NT-GL) – A pair of Black-bellied Seedeaters was seen on January 24, 2009 at PMR. The male was displaying a territo-rial behavior (aggressively replying the playback) and had its vocalization recorded. The female was phographed. Although they seemed paired – moving to-gether and not abandoning that half-hectare area – no direct indication of nesting was seen during this and the following day. The environment in which they were found was a humid grassland area with patches of turf and a dense cover of Asteraceae species, Eryngi-um spp. and Eupatorium grandiflorum. The small and altered surrounding fields of São Francisco de Paula constitute the southern edge of Campos de Cima da Serra (upland grasslands). Therefore this might be considered the southernmost record for this species.

Conservation and management

The history of land use at FNC, including the selective logging (in plantations), especially before the establishment of the protected area, allied to the prox-imity to the suburbs are considered the two major drivers of diversity loss during the past 60 years (Fer-raz, 2003). Illegal activities such as logging, hunting and fishing (IBAMA, 1989) may, direct or indirectly, be serious threats to the local fauna and flora. Hunt-ing, for instance, possibly caused the local extinction of the Solitary Tinamou (Tinamus solitarius), recorded in Canela by Belton (1994). The fragmentation itself, aggravated by habitat change, must have contributed to the decline or extinction of species sensitive to dis-turbance, such as large frugivores, ground insectivores and raptors (the latter affected by hunting or indirect-ly by prey scarcity). These are the bird groups that are the most disturbed by habitat change (Renjifo, 1999) and that were recorded almost exclusively at PMR, due to its better conservation situation.

A. angus-tifolia on 1948 and 1957, represent relevant areas for birds and other organisms. At these sites, we recorded Campephilus robustus and Procnias nudicollis, and oth-er sensitive and endangoth-ered animals, such as native canids, felids, cervids and rodents.

The local habit of burning grasslands annually to renew the pastures has significantly altered the natural habitat at PMR, where the grass is short and impov-erished. This activity is a possible driver of the local extinction of grassland birds that require dense and extended areas such as the species Gallinago undulata (humid grasslands and wetlands), Rhynchotus rufes-cens and Anthus nattereri (dry grasslands). However, other related species such as G. paraguaiae, Nothura maculosa and Anthus helmayri, with a wider ecological plasticity, were common at the site.

A few measures are suggested aiming to bring benefits to the bird assembly and biota as well: (a) the use of Araucaria angustifolia as a primary species in fu-ture plantations, reducing the use of exotic species at FNC; (b) a more moderate use of the forest resources such as Araucaria seeds (“pinhões”), restricting its ex-traction; (c) surveillance reinforcement as a means of eliminate illegal hunting; (d) keeping the large dead trees at the site of the fall, in order to maintain an adequate number of nesting cavities for parrots and other birds; (e) removal and control of domestic ani-mals such as cats and dogs; (f) extinction of grassland burning (illegal activity in the state of Rio Grande do Sul); and (g) end of the release of captive animals at the CUs. Moreover, land regularization at PMR and its surroundings is an urgent step for the elaboration of its management plan.

Further, it should be emphasized the importance of preserving the forests in northeast Rio Grande do Sul. This is one of the few regions in the state where it is possible to establish connectivity among patches and where the largest forests are found (together with the north and northwest). The areas in the plateau where the matrix is the forest have numerous endan-gered, rare and endemic species, granting them the priority for conservation efforts, as well as the adja-cent grasslands and wetlands. These areas are home of the threatened parrots Amazona pretrei and A. vina-cea. The city of São Francisco de Paula is situated in a transition between the forests from the south to the grasslands of the northeast plateau (Campos de Cima da Serra). Toward the southeast the landscape is char-acterized by the forested hills and slopes and, toward the west, by the plateau. Thus these protected areas are located in a key-region for the conservation of the rich forest environments in the plateau and its transi-tions, because it connects the forests from the slopes

and lowlands to those of the plateau, at its extremities. However this region has been suffering an accelerated process of habitat loss and fragmentation, mainly in open areas (natural grasslands), marked by the ad-vance of agriculture and forestry. With a goal to pre-serve the high biological diversity that still remains in this region, the creation and maintenance of conserva-tion units are imperative acconserva-tions. Equally relevant is the effectiveness of these protected areas that will be reached through adequate management actions.

RESUMO

Mais de 70% das aves ameaçadas de extinção no Rio Grande do Sul habitam ambientes florestais. A criação e manutenção de áreas protegidas é uma das principais me-didas apontadas para mitigar esses problemas. Contudo, para que estas áreas possam ser efetivas na conservação dos recursos naturais, o conhecimento sobre a diversidade biológicas nelas contida se faz necessário. Entre 2004 e 2009, foi realizado o levantamento de aves em duas áreas protegidas no Rio Grande do Sul: a Floresta Nacional de Canela (FNC) e o Parque Natural Municipal da Ronda (PMR), áreas representativas da Floresta Ombrófila Mis-ta (floresMis-tas com araucárias). Um toMis-tal de 224 espécies foi registrado, sendo 166 na FNC e 201 no PMR. Dez espécies ameaçadas de extinção no RS foram registradas: Pseudastur polionotus, Odontophorus capueira, Pata-gioenas cayennensis, Amazona pretrei, A. vinacea, Tri-claria malachitacea, Campephilus robustus, Grallaria varia, Procnias nudicollis e Sporophila melanogaster. A riqueza e composição de espécies parecem estar relacio-nadas aos diferentes graus de conservação das florestas, às suas dimensões e conectividade, bem como à disponibi-lidade de variados tipos de ambientes. As melhores con-dições ambientais do PMR, quando comparadas às da FNC, aliadas a sua posição geográfica, resultam em uma avifauna mais rica e composta em maior número por es-pécies ameaçadas, raras, endêmicas da Mata Atlântica e de alta sensibilidade à perturbação nos habitats. Medidas de manejo são sugeridas visando à conservação e recupe-ração das condições naturais das áreas a longo prazo.

Palavras-Chave: Mata Atlântica; Avifauna; Unida-des de conservação; Floresta Ombrófila Mista; Rio Grande do Sul.

ACKNOWLEDgMENTS

pos-Bencke, G.A.; Jardim, M.; Borges-Martins, M. & Zank, C. 2009. Composição e padrões de distribuição da fauna de tetrápodes recentes do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. In: Ribeiro, A.M.; Bauermann, S.G. & Schere, C.S. (Orgs.). Quaternário do Rio Grande do Sul: integrando conhecimentos. Porto Alegre, Sociedade Brasileira de Paleontologia. p. 123-142.

Bildstein, K.L.; Schelsky, W. & Zalles, J. 1998. Conservation status of tropical raptors. Journal of Raptors Research, 32: 3-18. Brooks, T.; Tobias, J. & Balmford, A. 1999. Deforestation and

bird extinctions in the Atlantic forest. Animal Conservation, 2: 211-222.

Cappelatti, A. & Schmitt, J.L. 2011. Flora arbórea de área de Floresta Ombrófila Mista em São Francisco de Paula, RS, Brasil. Pesquisas, Botânica, 62: 253-261.

CBRO – Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos. 2014. Listas das Aves do Brasil. 11. ed. 01/01/2014. Available at: www.cbro.org.br. Access in: 05/02/2014.

Efe, M.A.; Martins-Ferreira, C.; Olmos, F.; Mohr, L.V. & Silveira, L.F. 2006. Diretrizes da Sociedade Brasileira de Ornitologia para a destinação de aves silvestres provenientes do tráfico e cativeiro. Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 14(1): 67-72.

Ferraz, E.A.R. 2003. Floresta Nacional IBAMA Canela. In:

Oliveira, P. & Barroso, V.L.M. (Orgs.). Raízes de Canela. Porto Alegre, Edições Est. p. 423-432.

Fontana, C.S.; Bencke, G.A. & Reis, R.E. 2003. Livro vermelho da fauna ameaçada de extinção no Rio Grande do Sul. Porto Alegre, EDIPUCRS.

Fontana, C.S.; Rovedder, C.E.; Repenning, M. & Gonçalves, M.L. 2008. Estado atual do conhecimento e conservação da avifauna dos Campos de Cima da Serra do sul do Brasil, Rio Grande do Sul e Santa Catarina. Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 16(4): 281-307.

Franz, I. & Bencke, G.A. [inprep.]. Spatiotemporal dynamics of the range expansion and current distribution of the Pale-breasted Thrush (turdusleucomelas) in the state of

Rio Grande do Sul, southern Brazil.

Haffer, J. 1985. Avian zoogeography of the Neotropical lowlands.

Ornithological Monographs, 36: 113-146.

IBAMA – Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis. 1989. Plano de manejo para a Floresta Nacional de Canela, RS. Santa Maria, RS, FATEC/ UFSM. 388p.

IPAGRO – Instituto de Pesquisas Agronômicas. 1989. Atlas agroclimático do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. Porto Alegre, IPAGRO.

IUCN – International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2012. Red list of threatened species. Version 2012.2. Available at: www.iucnredlist.org. Access in: 07/10/2012.

Joenck, C.M. 2006. Observações de Spizaetus tyrannus (Acciptridae) no Centro de Pesquisa e Conservação da Natureza Pró-Mata (CPCN Pró-Mata) no nordeste do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil.

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 14(4): 427-428.

Leite, P.F. & Klein, R.M. 1990. Vegetação. In: IBGE. Geografia do Brasil: Região Sul. Rio de Janeiro, Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. v. 2. p. 113-150.

Mähler Jr., J.K.F. & Fontana, C.S. 2000. Os Falconiformes no Centro de Pesquisas e Conservação da Natureza Pró-Mata: riqueza, status e considerações para a conservação das espécies no nordeste do Rio Grande do Sul. Divulgações do Museu de Ciências e Tecnologia Ubea PUCRS, 5: 129-141.

Maluf, J.R.T. 2000. Nova classificação climática do estado do Rio Grande do Sul. Revista Brasileira de Agrometeorologia, 8(1): 141-150.

Marques, A.A.B.; Fontana, C.S.; Vélez, E.; Bencke, G.A.; Schneider, M. & Reis, R.E. 2002. Lista das espécies da fauna

sible, especially to Éwerton Ferraz, Raul P. Coelho and Paulo Rossi. To São Francisco de Paula city hall, for the logistic support and permission to conduct research at Parque Natural Municipal da Ronda and to Sogipa administrators for granting accomodation. To the colleagues and professors at the zoology and botany laboratories at Feevale, for all the help during the research years. To Glayson A. Bencke for the as-sistance given during the study and for the important contributions to the work that lead to the manuscript. To Marcelo F.B. dos Santos for informing about a re-cord of Black Hawk-Eagle. To CEMAVE/ICMBio for authorizing the ringing, as well as supplying the rings. To Universidade Feevale, for financing the proj-ects, the logistic support and the studentship. To Luís Fábio Silveira for textual suggestions.

REFERENCES

Accordi, I.A. & Barcelos, A. 2006. Composição da avifauna em oito áreas úmidas da Bacia Hidrográfica do Lago Guaíba, Rio Grande do Sul. Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 14(2): 101-115.

Agne, C.E. 2005. Novos registros de aves ameaçadas de extinção no estado do Rio Grande do Sul. Atualidades Ornitológicas,

126: 8.

Agne, C.E.; Rupp, A.E. & Accordi, I.A. 2007. Presença do pica-pau-rei (Campephilus robustus) no Planalto Médio do Rio Grande do Sul. In: Congresso Brasileiro de Ornitologia, 15º.

Livro de Resumos. Porto Alegre, EDIPUCRS. p. 217-218. Aleixo, A. 1999. Effects of selective logging on a bird community

in the brazilian Atlantic forest. The Condor, 101: 537-548. Balmford, A.; Gaston, K.J.; Blyth, S.; James, A. & Kapos,

V. 2003. Global variation in terrestrial conservation costs, conservation benefits and unmet conservation needs.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America, 100: 1046-1050.

Belton, W. 1994. Aves do Rio Grande do Sul: distribuição e biologia.

São Leopoldo, Editora Unisinos.

Bencke, G.A. & Grillo, H. 1995. Range expansion of the pale-breasted thrush Turdus leucomelas (Aves, Turdidae) in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Iheringia. Série Zoologia, 79: 175-176. Bencke, G.A. & Kindel, A. 1999. Bird counts along an altitudinal

gradient of Atlantic forest in northeastern Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Ararajuba, 7: 91-107.

Bencke, G.A.; Burger, M.I.; Dotto, J.C.P.; Guadagnin, D.L.; Leite, T.O. & Menegheti, J.O. 2007. Aves. In: Becker, F.G.; Ramos, R.A. & Moura, L.A. (Orgs.). Biodiversidade. Regiões da Lagoa do Casamento e dos Butiazais de Tapes, planície costeira do Rio Grande do Sul. Brasília, Ministério do Meio Ambiente. p. 316-355.

Bencke, G.A.; Dias, R.A.; Bugoni, L.; Agne, C.E.; Fontana, C.S.; Maurício, G.N. & Machado, D.B. 2010. Revisão e atualização da lista das aves do Rio Grande do Sul. Iheringia, Série Zoologia, 100(4): 519-556.

ameaçadas de extinção no Rio Grande do Sul. Decreto nº 41.672, de 11 de Junho de 2002. Porto Alegre, FZB/MCT-PUCRS/ PANGEA.

McDonald, R.I. & Boucher, T.M. 2011. Global development and the future of the protected area strategy. Biological Conservation, 144(1): 383-392.

Moreno, J.A. 1961. Clima do Rio Grande do Sul. Porto Alegre, Secretaria da Agricultura.

Morrone, J.J. 2001. Biogeografia de América Latina y el Caribe. Zaragoza, Sociedade Entomologica Aragonesa.

Parker III, T.A. & Goerck, J.M. 1997. The importance of national parks and biological reserves to bird conservation in the Atlantic forest region of Brazil. Ornithological Monographs,

48: 527-541.

Parker III, T.A.; Stotz, D.F. & Fitzpatrick, J.W. 1996. Ecological and distributional databases. In: Stotz, D.F.; Fitzpatrick, J.W.; Parker III, T.A. & Moskovits, D.K. Neotropical birds: ecology and conservation. Chicago,The University of Chicago Press. p. 113-436.

Pizo, M.A. 2001. A conservação das aves frugívoras. In:

Albuquerque, J.L.B.; Cândido-Jr., J.F.; Straube, F.C. & Roos, A.L. (Eds.). Ornitologia e conservação: da ciência às estratégias.

Tubarão, Editora Unisul. p. 49-59.

Primack, R.B. 1998. Essentials of conservation biology. Sunderland, Sunauer Associates.

PUCRS – Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul. 2011. Plano de manejo do Centro de Pesquisas e Conservação da Natureza Pró-Mata. Porto Alegre, PUCRS. Renjifo, L.M. 1999. Composition changes in a subandean

avifauna after long-term forest fragmentation. Conservation Biology, 13(5): 1124-1139.

Schmidt, R. & Longhi-Wagner, H.M. 2009. A tribo Bambusae (Poaceae, Bambusoideae) no Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Biociências, 7(1): 71-128.

SEMA – Secretaria do Meio Ambiente. 2008a. Plano de manejo do Parque Estadual do Tainhas. Porto Alegre, Secretaria Estadual do Meio Ambiente.

SEMA – Secretaria do Meio Ambiente. 2008b. Plano de manejo Reserva Biológica Estadual da Serra Geral. Porto Alegre, Secretaria Estadual do Meio Ambiente.

Sendulsky, T. 1995. Merostachys multiramea (Poaceae: Bambusoideae: Bambuseae) and similar species from Brazil.

Novon, 5: 76-96.

Sick, H. 1997. Ornitologia brasileira, uma introdução. Rio de Janeiro, Ed. Nova Fronteira.

Silveira, L.F. & Straube, F.C. 2008. Aves. In: Machado, A.B.M., Drummond, G.M. & Paglia, A.P. (Eds.). Livro vermelho da fauna brasileira ameaçada de extinção. Brasília, MMA. v. 2, p. 378-678.

Sonego, R.C.; Backes, A. & Souza, A.F. 2007. Descrição da estrutura de uma Floresta Ombrófila Mista, RS, Brasil, utilizando estimadores não-paramétricos de riqueza e rarefação de amostras. Acta Botanica Brasilica, 21(4): 943-955.

Straube, F.C. & Di Giacomo, A. 2007. A avifauna das regiões subtropical e temperada do Neotrópico: desafios biogeográficos. Ciência & Ambiente, 35: 137-166.

Teixeira, M.B.; Coura-Neto, A.B.; Pastore, U. & Rangel-Filho, A.L.R. 1986. Vegetação. In: IBGE. Levantamento de recursos naturais. Rio de Janeiro, IBGE. v. 33, p. 541-620. Varty, N.; Bencke, G.A.; Bernardini, L.M.; Cunha, A.S.;

Dias, E.V.; Fontana, C.S.; Guadagnin, A.; Kindel, E.; Raymundo, M.M.; Richter, A.; Rosa, O. & Tostes, C.S. 1994. Conservação do papagaio-charão Amazona pretrei no sul do Brasil: um plano de ação preliminar. Divulgações do Museu de Ciências e Tecnologia Ubea PUCRS, 1: 1-70.

Vasconcelos, M.F.; Vasconcelos, A.P.; Viana, P.L.; Palú, L. & Silva, J.F. 2005. Observações sobre aves granívoras (Columbidae e Emberizidae) associadas à frutificação de taquaras (Poaceae, Bambusoideae) na porção meridional da Cadeia do Espinhaço, Minas Gerais, Brasil. Lundiana, 6(1): 75-77.

Willis, E.O. 1979. The composition of avian communities in remanescent woodlots in southern Brazil. Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia, 33(1): 1-25.

Wilson, E.O. 1997. A situação atual da diversidade biológica. In:

Wilson, E.O. (Ed.). Biodiversidade. Ed. Nova Fronteira, Rio de Janeiro, 3-24.

APPENDIX

List of birds recorded at the Floresta Nacional de Canela (FNC) and at the Parque Natural Municipal da Ronda (PMR), Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, between 2004 and 2009. Sensitivity to disturbance (SD): H = high, M = medium, L = low. Conservation status and endemism: RS = threatened in Rio Grande do Sul, BR = threatened in Brazil, GL = globally threatened. EN = “endangered”, VU = “vulnerable”, NT = “near threatened”. AFE = endemic to the Atlantic Forest. References in the text.

SPECIES FNC PMR SD STATUS OF CONSERVATION AND ENDEMISM

RS BR gL AFE

TINAMIFORMES Tinamidae

Crypturellus obsoletus X X L

Crypturellus tataupa X L

Nothura maculosa X L

ANSERIFORMES Anhimidae

Chauna torquata X L

Anatidae

Dendrocygna viduata X L

Amazonetta brasiliensis X L

Anas flavirostris X X M

Anas georgica X L

gALLIFORMES Cracidae

Ortalis guttata X L

Penelope obscura X M

Odontophoridae

Odontophorus capueira X H VU X

PODICIPEDIFORMES Podicipedidae

Podilymbus podiceps X M

CICONIIFORMES Ciconiidae

Ciconia maguari X

PELECANIFORMES Ardeidae

Nycticorax nycticorax X L

Butorides striata X X L

Bulbulcus ibis X X L

Ardea cocoi X L

Ardea alba X X L

Syrigma sibilatrix X X M

Egretta thula X L

Threskiornithidae

Theristicus caudatus X X

CATHARTIFORMES Cathartidae

Cathartes aura X X L

Coragyps atratus X X L

ACCIPITRIFORMES Accipitridae

Elanoides forficatus X M

Elanus leucurus X L

SPECIES FNC PMR SD STATUS OF CONSERVATION AND ENDEMISM

RS BR gL AFE

Ictinia plumbea X M

Accipiter striatus X L

Pseudastur polionotus X H EN NT X

Heterospizias meridionalis X L

Rupornis magnirostris X X L

Geranoaetus albicaudatus X L

Buteo brachyurus X X M

gRUIFORMES Rallidae

Aramides cajaneus X H

Aramides saracura X X M X

Laterallus melanophaius X L

Pardirallus sanguinolentus X M

Gallinula galeata X X L

Gallinula melanops X M

CHARADRIIFORMES Charadriidae

Vanellus chilensis X X

Scolopacidae

Gallinago paraguaiae X

Jacanidae

Jacana jacana X X L

COLUMBIFORMES Columbidae

Columbina talpacoti X L

Columbina picui X X L

Patagioenas picazuro X X M

Patagioenas cayennensis X X M VU

Zenaida auriculata X L

Leptotila verreauxi X X L

Leptotila rufaxilla X X M

Geotrygon montana X M

CUCULIFORMES Cuculidae

Piaya cayana X X L

Crotophaga ani X X L

Guira guira X X L

Tapera naevia X L

STRIgIFORMES Tytonidae

Tyto furcata X X L

Strigidae

Megascops choliba X L

Megascops sanctaecatarinae X X

Strix hylophila X X H NT X

Asio clamator X L

CAPRIMULgIFORMES Caprimulgidae

Lurocalis semitorquatus X X M

Hydropsalis torquata X L

APODIFORMES Apodidae

SPECIES FNC PMR SD STATUS OF CONSERVATION AND ENDEMISM

RS BR gL AFE

Streptoprocne zonaris X L

Chaetura meridionalis X X L

Trochilidae

Stephanoxis lalandi X X M X

Chlorostilbon lucidus X X L

Thalurania glaucopis X M X

Leucochloris albicollis X X L X

TROgONIFORMES Trogonidae

Trogon surrucura X X M X

CORACIIFORMES Alcedinidae

Megaceryle torquata X L

Chloroceryle amazona X L

Chloroceryle americana X L

PICIFORMES Ramphastidae

Ramphastos dicolorus X X M X

Picidae

Picumnus temminckii X M X

Picumnus nebulosus X X M NT

Veniliornis spilogaster X X M X

Piculus aurulentus X X M NT X

Colaptes melanochloros X X L

Colaptes campestris X X L

Celeus flavescens X X M

Campephilus robustus X X M EN X

FALCONIFORMES Falconidae

Caracara plancus X X L

Milvago chimachima X X L

Milvago chimango X X L

Micrastur ruficollis X X M

Falco sparverius X L

PSITTACIFORMES Psittacidae

Pyrrhura frontalis X X M X

Myiopsitta monachus X L

Pionopsitta pileata X X M X

Pionus maximiliani X X M

Amazona pretrei X X M VU VU VU X

Amazona vinacea X X M EN VU EN X

Triclaria malachitacea X M VU NT X

PASSERIFORMES Thamnophilidae

Batara cinerea X M

Mackenziaena leachii X X M X

Thamnophilus ruficapillus X X L

Thamnophilus caerulescens X X L

Dysithamnus mentalis X X M

Drymophila malura X X M X

Conopophagidae

SPECIES FNC PMR SD STATUS OF CONSERVATION AND ENDEMISM

RS BR gL AFE

grallariidae

Grallaria varia X H VU

Hylopezus nattereri X X H X

Rhinocryptidae

Scytalopus speluncae X X M X

Formicariidae

Chamaeza campanisona X H

Chamaeza ruficauda X H X

Scleruridae

Sclerurus scansor X X H X

Dendrocolaptidae

Sittasomus griseicapillus X X M

Xiphocolaptes albicollis X X M

Dendrocolaptes platyrostris X X M

Xiphorhynchus fuscus X X H X

Lepidocolaptes falcinellus X X H X

Furnariidae

Furnarius rufus X X L

Leptasthenura striolata X X L X

Leptasthenura setaria X X L NT X

Synallaxis ruficapilla X X M X

Synallaxis cinerascens X X M

Synallaxis spixi X X L

Cranioleuca obsoleta X X M X

Anumbius annumbi X M

Syndactyla rufosuperciliata X X M

Philydor rufum X X M

Lochmias nematura X X M

Heliobletus contaminatus X X H X

Pipridae

Chiroxiphia caudata X X L X

Tityridae

Schiffornis virescens X X M X

Tityra cayana X X M

Pachyramphus castaneus X M

Pachyramphus polychopterus X X L

Pachyramphus validus X X M

Cotingidae

Carpornis cucullata X H NT X

Procnias nudicollis X X M EN VU X

Platyrinchidae

Platyrinchus mystaceus X X M

Rhynchocyclidae

Mionectes rufiventris X M X

Hemitriccus obsoletus X M X

Poecilotriccus plumbeiceps X X M

Phylloscartes ventralis X X M

Tolmomyias sulphurescens X X M

Tyrannidae

Tyranniscus burmeisteri X X M

Phyllomyias virescens X X M X

Phyllomyias fasciatus X X M

SPECIES FNC PMR SD STATUS OF CONSERVATION AND ENDEMISM

RS BR gL AFE

Elaenia mesoleuca X X L

Elaenia obscura X M

Camptostoma obsoletum X X L

Serpophaga nigricans X L

Serpophaga subcristata X X L

Lathrotriccus euleri X X M

Pyrocephalus rubinus X L

Satrapa icterophrys X X L

Xolmis cinereus X L

Xolmis irupero X X L

Muscipipra vetula X M X

Arundinicola leucocephala X M

Machetornis rixosa X X L

Legatus leucophaius X L

Pitangus sulphuratus X X L

Myiodynastes maculatus X X L

Megarynchus pitangua X X L

Empidonomus varius X X L

Tyrannus melancholicus X X L

Tyrannus savana X X L

Myiarchus swainsoni X X L

Attila phoenicurus X H

Vireonidae

Cyclarhis gujanensis X X L

Vireo olivaceus X X L

Hylophilus poicilotis X M X

Corvidae

Cyanocorax caeruleus X X M NT X

Cyanocorax chrysops X L

Hirundinidae

Pygochelidon cyanoleuca X X L

Stelgidopteryx ruficollis X L

Progne tapera X X L

Progne chalybea X X L

Tachycineta leucorrhoa X X L

Troglodytidae

Troglodytes musculus X X L

Turdidae

Turdus flavipes X M

Turdus rufiventris X X L

Turdus leucomelas X L

Turdus amaurochalinus X X L

Turdus subalaris X X L X

Turdus albicollis X X M

Mimidae

Mimus saturninus X L

Motacillidae

Anthus helmayri X L

Passerellidae

Zonotrichia capensis X X L

Ammodramus humeralis X L

Parulidae

SPECIES FNC PMR SD STATUS OF CONSERVATION AND ENDEMISM

RS BR gL AFE

Geothlypis aequinoctialis X X L

Basileuterus culicivorus X X M

Myiothlypis leucoblephara X X M X

Icteridae

Cacicus chrysopterus X X M

Icterus pyrrhopterus X M

Gnorimopsar chopi X L

Pseudoleistes guirahuro X L

Agelaioides badius X X L

Molothrus bonariensis X L

Thraupidae

Coereba flaveola X X L

Saltator similis X X L

Saltator maxillosus X X M X

Pyrrhocoma ruficeps X X M X

Tachyphonus coronatus X X L X

Tangara sayaca X X L

Tangara preciosa X X L

Stephanophorus diadematus X X L

Pipraeidea bonariensis X X L

Pipraeidea melanonota X X M

Tersina viridis X L

Dacnis cayana X L

Hemithraupis guira X L

Haplospiza unicolor X X M X

Donacospiza albifrons X L

Poospiza cabanisi X X M

Sicalis flaveola X X L

Sicalis luteola X X L

Emberizoides ypiranganus X M

Embernagra platensis X X L

Volatinia jacarina X L

Sporophila caerulescens X X L

Sporophila melanogaster X M VU VU NT X

Cardinalidae

Habia rubica X H

Cyanoloxia brissonii X M

Cyanoloxia glaucocaerulea X X L

Fringillidae

Sporagra magellanica X X L

Euphonia chlorotica X X L

Euphonia chalybea X M NT X

Euphonia pectoralis X M X

Chlorophonia cyanea X X M

Estrildidae