www.rbceonline.org.br

Revista

Brasileira

de

CIÊNCIAS

DO

ESPORTE

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Three

types

of

transnational

players:

differing

women’s

football

mobility

projects

in

core

and

developing

countries

Nina

Clara

Tiesler

a,baInstituteofSociology,LeibnizUniversityofHannover,Hannover,Germany

bInstituteofSocialSciences,UniversityofLisbon,Lisbon,Portugal

Received20October2015;accepted11January2016

Availableonline5March2016

KEYWORDS Soccer; Migration;

Transnationalplayers; Womenathletes

Abstract Mobileplayersinmen’sfootballarehighlyskilledprofessionalswhomovetoa

coun-try other thantheone wherethey grewup andstarted their careers. Theyarecommonly

described asmigrantsorexpatriateplayers. Duetoamuchlessadvancedstageof

profess-ionalismandproductionofthegameinwomen’sfootballmobilityprojectsaredifferent.At

describingthecasesofBrazil,EquatorialGuinea,Mexico,ColombiaandPortugal,theaimof

thispaperistoconceptualiseanumbrellacategoryformobileplayersthatcanincludecurrent

realitiesinthewomen’sgame,namelythetransnationalplayerwhohasgainedanddisplays

transnationalfootballexperienceindifferentcountriesandsocio-culturallycontexts.

Further-more, analyses allow introducingtwonew subcategories besidesthe‘‘expatriate’’,namely

diasporaplayersandnewcitizens.

©2016Col´egioBrasileirodeCiˆenciasdoEsporte.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrights

reserved. PALAVRAS-CHAVE Futebol; Migrac¸ão; Jogadoras Transnacionais; MulheresnoEsporte

Trêstiposdejogadorastransnacionais:diferenciandoprojetosdemobilidade defutebolistasmulheresempaísescentraiseemdesenvolvimento

Resumo Amobilidadeinternacionaldejogadoresdefutebolsecaracteriza,geralmente,pelo

deslocamentodeprofissionaisdealtonívelparapaísesdiferentesdaqueleemquecresceram

einiciaramcarreira.Sãodescritos,comumente,comomigrantesouexpatriados.Emestágio

muitomenosavanc¸adodeprofissionalizac¸ão,amobilidadeentrejogadorasacontece

diferente-mente.AodescrevercasosdoBrasil,naGuinéEquatorial,noMéxico,naColômbiaeemPortugal,

E-mails:ninaclara.tiesler@ics.ulisboa.pt,n.tiesler@ish.uni-hannover.de http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbce.2016.02.015

oartigoprocuradesenvolverumacategoriaconceitualcapazdeabarcarodeslocamentoque

configura uma jogadora transnacional, cuja experiência se dá diferentes países e

contex-tossocioeconômicos.Introduzainda duasnovassubcategorias,para alémda‘‘expatriada’’:

jogadorasemdiásporaenovascidadãs.

©2016Col´egioBrasileirodeCiˆenciasdoEsporte.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todosos

direitosreservados. PALABRASCLAVE Fútbol; Migración; Jugadoras transnacionales; Mujeresdeportistas

Trestiposdejugadorastransnacionales:diferenciarproyectosdemovilidad defutbolistasmujeresenpaísescentralesyendesarrollo

Resumen Lamovilidadinternacionaldejugadoresdefútbolsecaracterizaconfrecuenciapor

eldesplazamientodeprofesionalesdealtonivelapaísesdistintosdeaquellosenquecrecieron

ycomenzaronsuscarreras.Aparecenengeneralcomojugadoresmigrantesoexpatriados.En

ungradomuchomásbajodeprofesionalización,lamovilidaddejugadorassepresentadeotra

manera. AldescribirloscasosdeBrasil,GuineaEcuatorial,México,Colombiay Portugal,el

artículoprocuradesarrollarunacategoríaconceptualquepuedaincluirlasrealidadesactuales

eneljuegofemenino,esdecir,lajugadoratransnacional,quehaalcanzadoydisfrutadeuna

experienciatransnacionalendistintospaísesycontextossocioculturales.Introduce,además,

dosnuevassubcategorías,másalládelasituaciónde«expatriada»:jugadorasdeladiásporay

nuevasciudadanas.

©2016Col´egioBrasileirodeCiˆenciasdoEsporte.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todoslos

derechosreservados.

Aswithyoungmalesallovertheworld,agrowingnumber of young women equally dream of becoming professional footballersandpursuingtheirdreamsbyintensively invest-inginto their skills over years. The number of registered players has, in fact, more than doubled since 2000, with over30millionfemalesplayingthegame(FIFA,2007).That said,however,‘makingaliving’asafootballplayerinthe women’sgameisonlypossibleinaroundtwenty-twooutof 147FIFA-listedcountries.1Thisimpliesthatinmorethan85

1TheFIFAwomen’srankingofSeptember2015listed147active countries.Thisnumbervariesandhasbeenhigher(upto168)or lower(downto123)inpreviousyears.Nationalsquadswhichremain inactiveforanumberofyearsdropout.Basedontheinterviews withplayers and staff,as well as formal statements(UEFA and FIFA)and pressinformation,twelveleaguescouldbedetermined forthe2011/2012seasonwhere50---75percentofplayersreceived asalaryandthuswereenabledtoconcentrateexclusivelyon soc-cer:USA,Germany,Russia,Sweden,Japan,(probablyNorthKorea,), SouthKorea,China,Netherlands(since2007),Mexico(since2009), Cyprus(2009)andEngland(since2011).YettheWPSintheUSAwas theonlyfullyprofessionalleagueuntilitsclosureinJanuary2012, andneitherNorthKoreanorMexicohadexpatriateplayers.Ifwe tracetheplayers’routes,we candetermineanothereleven pos-sibledestinationcountriessofar:France,Canada,Australia(since 2010),Italy,Norway,Denmark,Iceland,Spain,Austria,Switzerland andFinland.Herelocalplayersreceivedonlyasmallsalaryoran allowance,whilesemi-professionalorprofessionalcontractswere mainlyofferedtomigrantsorreturnees.Forpartoftheplayers, theremunerationenabledtheexclusiveconcentrationonsoccer,

percentofthecountrieshighlytalentedwomenfootballers have toleave their home in orderto play professionally. The percentage of top players who leave the peripheral andsemi-peripheralcountriesofwomen’sfootball,among themEuropeanscountriessuchasPortugal,Ireland,andthe Ukraineisattimesat80percent(Tiesler,2010,p.4;Tiesler, 2011).In2013,theTopThreeemigrationcountrieshadbeen Canada(88.9 percent),Mexico(77.8percent)andWales (75per cent)(AgergaardandTiesler, 2014a,p. 38).While the firstprofessionalsoccerleaguefor women inthe USA (WUSA) and itsfollow-up WPS (Women’s Professional Soc-cer League),leagues inthebiggest receivingcountry,had accountedforupto30percentofmigrantplayers,the per-centagesofforeignersinthepreferredcountriesoffurther destinations,whilesuchasSweden,Germany,England, Rus-sia andSpain in2009 (Tiesler, 2010,p. 5),respectively in theorderGermany,Sweden,Russia,EnglandandNorwayin 2013(AgergaardandTiesler,2014a,p.40)makeupon aver-age around19 percent.In singlepremierleagueclubs in theEuropeancorecountries,2suchasGermanyandSweden

sinceitwascombinedwithfreeaccommodation,andinsomecases unlimitedaccesstoacarwasincludedinthepackage---orelsethe contractguaranteedpaidpart-timeemployment(asacoach, phy-siotherapistorinafactory)besides smallsalary,accommodation andvehicleuse.

2Iconsideras corecountriesofwomen’ssoccerthosethat (a) runwell-organised,partly(semi-)professionalleaguesandfeature

(comingfirst),migrantscanconstituteanywherebetween36 and50percentofleagueplayers(teamrosters2010/113;

Pfisteretal.,2014,p.151---153).

Inthegrowingbodyofliteratureonsportsmigration,in general,andonthemobilityoffootballtalentandlabour,in particular,athleteswhoarecrossingbordersforprofessional reasonsandforcareerpurposesarecommonlydescribedas migrants(BaleandMaguire,1994;TieslerandCoelho,2008; MaguireandFalcous,2010;AgergaardandTiesler,2014b)or sojourners(MaguireandStead,1996),asmobilityprojects infootballareoftencirculativeand/orbasedononlyshort termcontractsandstaysabroad(Rial,2008,2014).Inorder tograsptheexperiencesandactivitiesofmigrantswhodo notnecessarilysettlepermanently--- and/orwhere assimila-tiontothehostsocietyisnottheultimateoronlyoutcome ---theconceptoftransnationalismwasdevelopedinmigration studies(Glick-Schilleretal.,1992;Portes,1997;Vertovec, 2004). What wasconsidered asnew and characteristicof these types of migrants is that their networks, activities and patternsof life encompass both home andhost soci-eties(Glick-Schilleretal.,1992,p.l);characteristicswhich matchwiththevastmajorityofmigrantsinthesocialfieldof football(Maguire,1999;LanfranchiandTaylor,2001;Magee andSugden,2002;TrumperandWong,2010).

Sojourners and migrants in men’s football are highly skilledprofessionalswhomove to,settle,liveandwork ---atleastforabriefperiodofresidence---inacountryother thantheonewheretheygrewupandstartedtheircareers.A stepawayfromthedifficultiestodistinguishmigrantsfrom sojournersandviceversa(formainstreammigrationstudies

oneofthetwentybestpercapitaindices(eitherincomparisonto othernationsortothemen’spercapitaindex),(b)whosenational teamshavesucceededinqualifyingforthefinalsofWorldCupsor theOlympicgamesandwhohavekeptamongtheFIFAranking’stop 20foratleastthreeyearsaswellas(c)thosecountriesinaposition to afford the legal and financial prerequisites for the employ-ment of football migrants --- and who then actually implement them.ThisholdstrueforUSA,Sweden,Norway,Germany,Denmark, Japan,China,SouthKorea,Finland,France,Italy,England, Nether-lands,Canada,Australiaand Russia.Assemi-peripheralcountries inwomen’sfootballareconsideredthosewhichrankbetween16th and 30thintheFIFAlistand regularlyattainsuccessesat conti-nentaltournamentssuchastheAsianCuporAfricaCup(Trinidad and Tobago,Nigeria,Mexico) andwhich are eitherable tooffer semi-professionalconditionsinatleastafewclubs(e.g.Iceland, Finland,Spain)and/ortheirmobiletalentsarerecruitedbythetop leagueclubsofthecorecountries(e.g.NewZealand,Switzerland, Scotland,Columbia,tosomedegreeNigeriaandGhana).Atanyrate thecriterionforthosesemi-peripheralclimbersisthattheyprovide sufficientqualitytoplayanyroleatallintheinternational circu-lationand market ofplayers.Allother countriesareconsidered peripheralcountriesofwomen’sfootball,sincetheylacka mini-mumofstructuralconditionssuchasa leaguesystemfor allage groupsofgirls,andhencetheyfeaturearelativelyweak participa-tionofactives.Forendeavourtodeterminecore,semi-peripheral andperipheralcountriesofthegamealongthelinesofstructural, supra-structural(here:gendersystems) andsocio-cultural (here: stigmavs. recognition)conditionsseeTiesler(2012b). Fora dif-ferentapproachonpowerrelationsanddependenciesbetweenthe core,semi-peripheralandperipheralstatesinmalesportsmigration seeMaguire(2004,p.487).

3http://www.zerozero.pt/edicao.php?idedicao=6226&op=dados.

seeReyes,2001andTannenbaum,2007,forathlete migra-tionsee Agergaard et al., 2014) and with regardsto the particularitiesofthefootballlabourmarket,PoliandBesson havecoinedaconceptwhichincludesboth:the‘‘expatriate player’’(PoliandBesson,2010;Bessonetal.,2011).Their definitionreads:

‘‘An expatriate player is a footballer playing outside of the country in which he grew up and from which he departed followingrecruitment bya foreign club’’ (Bessonetal.,2011:1).

The concept certainly grasps biographical and recruit-ment realities behind the dominant mobility pattern in men’sfootball.Duetoamuchlessadvancedstageof pro-fessionalism and production of the game (organisation of leaguesand competition for all agegroups, coachingand trainingfacilities, legal frameworks for recruitment, rea-sonable wagesand health insurance) mobility projects in women’sfootballaredifferent.Notallmobilewomen play-ers,however,aremigrantsorexpatriates,respectively.For example,of the one-quarter of national squad players at the FIFA Women’s World Cup 2011 (WWC 2011) who held contracts in clubs abroad, the concept of the expatriate playercannot beapplied. The percentageof cases which dropoutofthisevenmostinclusiveconceptdevelopedfor men’sfootballmigrationincreaseswhenspecificallylooking attheperipheralandsemi-peripheralcountriesofwomen’s football, such as Equatorial Guinea, Mexico, Colombia or Portugal.

Theaimofthispaperistoconceptualiseanumbrella cat-egoryformobileplayersthatcanincludecurrentrealitiesin thewomen’sgame,namelythetransnationalplayerwhohas gainedanddisplaystransnationalfootballexperiencein(at least)twocountriesandsocio-culturallydifferentcontexts. Due to the integration of what we coin diasporaplayers and new citizens into the national squads of ambitious newcomersinwomen’sfootball,wefindmobilityprojects (aspirations,experiences,andoutcomes)oftransnationally experiencedtopplayerswhich differfromthe expatriate, theidealtypeofthemobilemaleplayer.4

Conceptualisation is based on insights derived from a case study amongst thePortuguese national squad(based on expatriate and diaspora players), analyses of original quantitativedataoninternationalfluxes,andofsecondary qualitativematerial(pressarticles,onlineandFIFAsources) onbiographiesofplayerswhorepresentedBrazil(high num-ber of expatriates), Mexico (diaspora players), Colombia (college players) and EquatorialGuinea (newcitizens) at the WWC2011. Fieldwork hasmainly taken place in Por-tugal from December, 2009 up to March 2013, including researchperiodsduringtheAlgarveCupsof2010,2012and 20135whichallowedinterviewingmobileplayersofdiverse

4Intheirrevisionofcommontypologies ofathletemigrants,in 2014Agergaard, Botelhoand Tieslerproposeddifferenttypesof transnationalplayers,namely‘‘settlers,sojournersandmobiles’’ (Agergaardetal.,2014).

5TheAlgarveCupisaglobalinvitationaltournamentfornational teams,organisedbythePortugueseFootballFederation,recognised byFIFA,andheldannuallyintheAlgarveregionsince1994.Called the‘Women’sMiniWorldCup’(MundialitodoFutebolFeminino).It

nationalities.6 Thedatamaterialallowspointingoutsome

main trends and features which shape Women’s Football Migration (WFM),and consequentimpact onthe develop-ment of the game. Whogoes where and why in women’s footballmigration?Howfardothemobilityprojectsof expa-triates,diasporaplayersandnewcitizensdifferfromeach other?

Encompassing

both

home

and

host

societies:

expatriates

as

transnational

players

Over the past years, Brazilian expatriate players were presentinnearlyallofthe22receivingleagues,fromthe highest ranking such as the USA, Sweden and Japan over SouthKorea, Italy,Spain, in thefinanciallystrong Russian league,andeveninlowrankingcountriessuchasAustria, Cyprus,PolandandSerbia whereonlysingleclubsprovide rathermodestallowancestomigrantplayers.7Manyofthem

are/werenational squad players and some of them regu-larly spent partsof the (off-) seasonon loan in Brazilian clubs.BeforeleavingtoAustriain2004 RosanadosSantos AugustohadalreadybeenonthemoveinsideBrazilandhas meanwhilelived infourdifferentcountries.Aswithother expatriateplayers,herfootballmobilityprojectsinvolvean

isoneofthemostprestigiouswomen’sfootballevents,alongside theWomen’sWorldCupandWomen’sOlympicFootball.

6Basedon long-termcontact (since2009 viaSkype, Facebook andemail)tocoachesandplayers,31one-on-oneinterviewswith mobile women footballers, eight brief interviews with players withoutintentionsofmigration(controlgroup),aswellasten back-groundtalkswithcoaches,staffandparents.The31mobileplayers whovolunteeredforsemi-structuredinterviews,whowerebornand grewupinPortugal(14),Norway(5),Sweden(5),USA(2),Japan(2), Brazil(2)andGermany(1).Theyspokeoftheirexperienceas pro-fessionalsandsemi-professionals‘abroad´leadingfirstdivisionclubs inthefollowingcountries:Germany,Spain,France,Iceland,Italy, Sweden,Russia,China,Canada,andtheUSA.Thestaffandcoaches originatedfrom Norway,Sweden,Portugal andtheUSA,the par-entsfromPortugalandtheUSAandtheplayerswithoutintention orexperienceofmigrationfromPortugalandGermany.

7Accordinglytoconversationsamongmigrantplayersduringthe year2012,exceptionaltopwagesinBrazilfornationalsquad play-ersnormallydonotexceedsome800Euro(2000Real)permonth.In theGermanFrauenbundesliga,whichappearstobethewealthiest women’sleaguesworldwidethewagesofonly threetopplayers wereestimatedasnumberingover100.000Europeryear.Another eight bestpaid German players receive at average 62.500Euro peryear.FortheEnglishsemi-professionalWomen’sSuperLeague (WSL),setupinsummer2011,theclubshaveallsigneduptoasalary cap,stipulatingthatnoclubcanpaymorethanfourofitsplayers over£20.000(24.000EuroinJanuary2012).Whilewelackreliable updatedinformationonwagesinSweden,sourcesfrom2006and 2008indicatedverylowaveragewagesforlocalplayers(5.500Euro peryear in2006,6.228 in2008),whilemigrantplayersreceived more(bloggersassumedthatMartaearned11timesmorethanthe averagewageoflocalplayers).Sources:TheGuardian2008:http:// www.guardian.co.uk/football/2008/oct/05/womensfoot-ball.ussp-ort. Spiegel Online 2011: http://www.spiegel.de/sport/0,1518,-770013,00.html. Stockholm News 2008: http://www. stockholmnews.com/-more.aspx?NID=1055. The Guardian 2011: http://www.guardian.co.uk/football/blog/2011/apr/07/womens-super-league-launch.

offerbyaclubabroad,migrationdecisionmaking,settling in aforeigncountryandliving awayfromhome,adapting todifferentculturalcodesonandbeyondthepitch, identi-fyingwithherteaminthehostsociety,keepingcontactto peopleandplacesleftbehindviainformationtechnologies, afewvisits,aswellasduringtrainingcampsandmatchesof her nationalsquad.As is alsothe case withother women migrant players from Latin America, African and Eastern Europeancountries,thewagessheearnsinEuropean (Cham-pionsLeague)andwiththeUSAmericanWPSclubsallowher tosupportherfamilyathome.

Byswitchingclubsandcrossingbordersshehasenlarged and diversified her football experience provided both to theclublevel(currentlyplayingatHoustonDash,USA)and withtheBraziliannationalsquad.Hernetworks,activities andpatternsoflifeencompassbothhomeandhostsociety’ (Glick-Schilleretal.,1992,p.1),asdoesherfootball expe-riencewhichonecancoinasbeingtransnationalinnature (compare:Agergaardetal.,2014).

A transnational player gains maturity and enlarges her/his football experience by having been trained and embedded in different societies and football systems. Sporting ambitions such as developing football experi-ence were highlighted elsewhere as key motives among womenfootballmigrantsfromdiversecountries(Agergaard and Botelho, 2010; Botelho and Agergaard, 2011; Tiesler, 2012a,b; Agergaard etal., 2014). Playing football abroad is seen as a means of transforming yourself into a more mature playerand hasbeen described asrites ofpassage (SteadandMaguire,2000;BotelhoandAgergaard,2011,p. 814).Whatturnsthis(atleast)bi-societalfootball experi-ence intoa transnationalone is the players’ engagement inboththeclub(anddomestic league)ofonecountryand in the national squad of another. In playing for her/his nationalsquadandaclub abroad,s/hedisplaysthis expe-rience‘acrossnationalboundariesandbrings(atleast;nct) twosocietiesintoasinglesocialfield’(Glick-Schilleretal., 1992, p. 1) which, in this case, is that of football. This holdstrueforthemajorityofexpatriateplayersinwomen’s football as most of them areusually seeking contracts in morecompetitivechampionshipswhichalsoprovidebetter trainingfacilities andthe desiredopportunity todedicate themselvesexclusivelytofootball.

As such few leagues can provide at least semi-professional conditions, playing abroad means improving yourskills.Consequently,itisperceivedasoverwhelmingly positivebytheplayersthemselves,aswellasbycoachesand staffresponsibleforthenationalsquadsofsemi-peripheral andperipheralcountries.Themajorityofinterviewed play-ers from such countries pointed out the aimsof ‘playing professionally’, ‘improving my skills’, and ‘improving my performance for the national squad’ asthe main motiva-tiontopursueacareerabroad(Tiesler,2012a,b:235).Head coaches and staff from the core countries, on the con-trary, do not necessarily supporttheir players emigration aspirations,8 unlessthe destinationleagueis clearlymore

8Themoveofa Scandinaviannationalteamplayertothe Rus-sianfirstdivision,forexample,washotlydebatednotonlyamongst responsiblestaffbutalsointhepress.Theplayerherselfreported tomethatherteammates,friendsandfamilywerecriticalabout

competitiveand/ortheclubcompetesintheUEFA Champi-onsLeague;thelatter havingbeenthe impulsefor aturn inthe ‘migrationpolicy’e.g.of theJapanese head coach (Takahashi,2014).

All migrant (or expatriate) players who, at the same time,arepartofthenationalsquadoftheirhomecountry can be considered transnational players. But this experi-enceisnotanexclusivefeatureofexpatriateplayersonly. Not all transnationalplayers are actual migrants, respec-tivelyexpatriates,astheirfootballmobilityprojectsdiffer fromtheexemplaryonerepresentedinRosana’scase.This becomesapparentwhenlookingatandbehindthefollowing figure,andespeciallyinthecaseofEquatorialGuinea, Mex-ico and Colombia as sendingcountries, as well as Brazil, which here suddenly appears as a major receiving coun-trywhile duringallyearspriortheWWC2011ithadbeen amongtheTopTenemigrationcountries.The ‘production’ ofthegameinBrazilandconsequentlytheconditionsinthe domestic leaguedidnotimprovenoteworthybetween the timeoftheOlympics2008(whenBrazilwasamongthemain exporters)andtheWWC2011. Soit comesasquite a sur-prisetofindplayersfromEquatorialGuineawithaffiliations toBrazilianclubsinthefollowingoverview.

Increased

international

mobility

and

diverse

mobility

projects

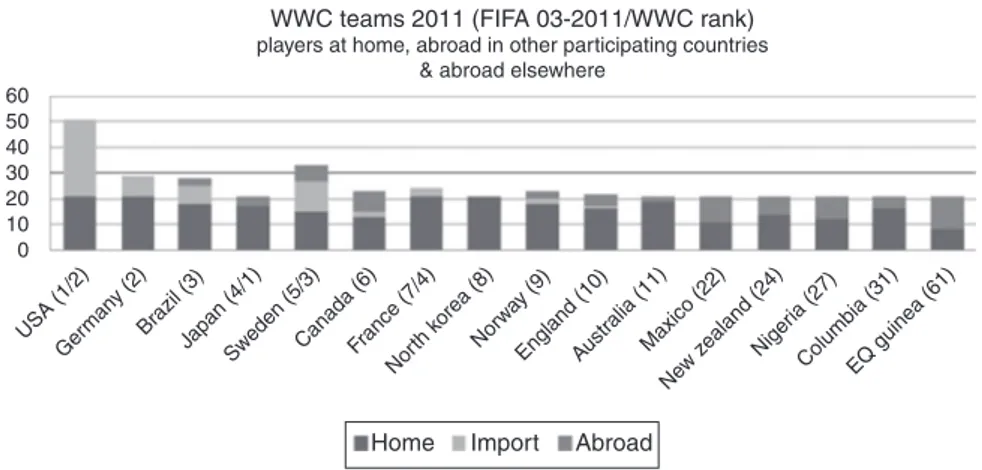

TheFigure1isbasedonanoverviewoftheclubaffiliationof 336playerswhowerecappedforthesixteennationalsquads competingattheWWC2011.72ofthem,whichis21.4per cent,held contracts incountriesother than the onethey representedattheWorldCup.

As usual, the People’sRepublic of NorthKorea neither attractedany foreignplayer, nordid anyof itsown play-ersleave the country.All theother competing teams had been involved, in one way or another, in what has been introducedasakeyfeatureoftheglobalisationprocessof women’sfootball, namely in theinternational mobility of players.Wehavefoundthreemerereceivingcountries,five thatwerebothimportingandexportingplayers,andseven mereemigrationcountries.Asimilaritytothesurveyof play-ers’ circulation amongthe (only 12)Olympic countriesof 2008isthatthenumberofmeresendingcountriesisalways thehighest(Tiesler,2011,p.7of16;Tiesler,2010,p.6of 12).Thisis becauseonlysuchfewdomestic leagues,even amongcountries,whichqualifyforthehighestinternational tournaments,canprovideatleastsemi-professional condi-tions.

Incontrastto2008,whereonlyonecountrywasat the sametimesenderandreceiverofwomen’sfootballlabour,in 2011thisnumberevenexceededtheoneofmerereceiving countries.Thisisinterestingbecausein2011alreadymore countriesthanin 2008providedat leastsemi-professional

itaswell.AnothertopplayerfromaScandinaviancountrytoldme aboutherrathercareerharmingexperienceinaChampionsLeague club.Herdifficultiestoadapttoadifferentplayingandcoaching styleleadtoherspendingmoretimeontheplayersbenchduring theseasonsothatherprominentpositioninthestartingelevenof hernationalsquadwasputatstakeduetolackofpractice.

conditions (with England and Mexico having started run-ning professional leagues), and still the number of mere receiversdecreased.Itpointstothetendencythatplayers arenotonly migratingoutofpure necessity.Moreplayers fromthecore countriesandotherswhofindgoodathletic (partlyprofessional)conditionsintheirdomesticleagueare seeking contracts abroad before retiring from their own national squad and prominent positions at home; either because financial conditions are more attractive abroad, togaintransnationalfootball experience,or both. This is shownbythecasesofSwedenandJapanwhichstill,in2008, hadbeenmerereceivingcountries.WhiletheWorld Cham-pioninJapandidnothostanyforeignWorldCupplayerin itsdomesticleagueatthatmomentintime(June2011),it wasabletocountonfourtransnationallyexperienced play-erswhogotpreparedfor theinternationaltournamentby playingforhigh rankingclubsintheUSA(1),Germany(2) andFrance(1).

College

players

as

migrants

Atotalof51WorldCupplayersgotpreparedforthe tour-namentintheUSAduringtheseason,byplayinginWPSor collegeteams:the21Americanplayersaswellas30whoare nationalsquadplayersofothercountries:sevenplayersof theMexicannationalsquad,Canada,EnglandandColombia withfiveeach, NewZealand,SwedenandBrazil withtwo each, andJapan and Australia withone each. Only 18 of thembecamemigrantsfollowingtherecruitmentofa (pro-fessionalWPS)cluband,assuch,matchwiththeconceptof theexpatriateplayer.FiveplayersfromColombiaandone fromNewZealand had movedtothe USA onthe basis of soccerscholarshipswhichallowthemcombininganintense football activity witheducationalpurposes.9 Theycan be

considered migrants, as their mobility projects involve basicallythesamefeaturesasexemplifiedbyRosana’s expe-rience(migrationdecisionmaking,settlingawayfromhome, phasesofadaptationonandbeyondthepitch,etc.).They alsomovetoa higherranking country,but have not(yet) enteredanationalleaguenoraretheysignedasprofessional orsemi-professionalplayers.Therefore,theyarenot expa-triatesbutcollegeplayers,andstilltheyembodyanddisplay transnationalfootballexperiencewhenjoiningthenational squadoftheirhomecountry.

Besides Colombia which debuted with the youngest amongofallWWCteamsin2011,anumberofothernational teamsregularlycountontheenforcementofcollege play-erswhoreceivetheirfootballsocialisationinthestrongUS Americansystemwhichcountedon18millionactiveplayers in2011,amongthemCanada,Portugal,Ghana,Trinidadand TobagoandMexico.But notallcollege playersin theUSA whoholdforeignnationalitiesarefootballmigrants.

9OnthegravitationalpulloftheUSAmericancollegesoccer sys-tem,seeBooth and Liston (2014). Regardingtheways how this pullimpactsonnationalpoliciesintherealmofwomen’sfootball in(semi-)peripheralcountries,see theexampleofTrinidad and TobagobyMcCree(2014).

60 50 40

Home

WWC teams 2011 (FIFA 03-2011/WWC rank)

players at home, abroad in other participating countries

& abroad elsewhere

Import Abroad

30 20 10 0 USA (1/2) Ger man y (2) Brazil (3) Japan (4/1) Sw eden (5/3)Canada (6) France (7/4) Nor th korea (8) Norw ay (9) England (10)Austr alia (11) Maxico (22) New z ealand (24)Niger ia (27) Columbia (31)EQ guinea (61)

Figure1 MobilityofFIFAWomen’sWorldCupPlayers2011.Originalfigure(bytheauthor),basedonFIFAplayerslists.

Non-migrants

who

gain

and

display

transnational

football

experience:

diaspora

players

AmongthesixMexicannationalsquadplayerswhoare affili-atedtouniversitiesinCaliforniaandTexas,onlyoneactually movedtotheUSA afterhavingbeen granteda respective scholarship.One had movedthere withher familyat the ageofthreeandanotherfourwerebornintheUSto Mex-icanparents.TheygrewupintheUSA,haveneverlivedin Mexico,didnot leavetheircountry ofbirth and socialisa-tion,nordidtheysettleabroadforfootballreasons.Their mobilityprojectsdonotinvolvemigrationdecision-making andtheydonot follow therecruitment ofa club abroad. Theyfollowtheinvitationofanationalfootballassociation tojointhenationalteamoftheirparents’homecountryof whichtheyusuallypossesscitizenshiporareabletoobtain itduetoancestry.Theirmobilityprojectsarenotalikethose ofexpatriateplayersormigrantcollegeplayers,astheyare onlytravelling(butnotsettling)abroadtojointheirnational squadfortrainingcampsandmatches.Isuggest,following theconcept introduced bythe journalistand author Tim-othyGrainey(2008),coiningthemdiasporaplayers.Other nationalteamswhoareknownforintegratingasignificant numberofdiasporaplayersfromcountriesthatprovidemore advancedinfrastructuresfor thewomen’sgame arelower rankingperipheralcountriessuchasGreece,Turkey,Israel andPortugal.Sincetheyearof2005,thelattercountedon thedaughtersof Portuguesemigrantswhoweresocialised in theUSA, Canada, Brazil, France, Switzerland and Ger-many,someofthemmakingthesquadforanumberofyears. Whilecontinuingtoplayinthedomestic championshipsof theircountryof births,theyexpandtheir football experi-encebyintegratingintothenationalsquadofthecountry thattheir parents hadleft,and at international competi-tionswheretheycompetewithothernationalteams.They aresupposedtoimprovetheperformanceoftheteamand expectedtoadapt toaprobable differentfootballsystem andculturalcodes(includinglanguage,interaction)onthe pitchbuthardlybeyond.

Albeit,beingpartofafootball team,which represents a given nation, in reality they are not embedded in this

society-at-large.Thespaceofsocio-culturalexperienceof the country they represent is fairly limited to the social fieldof football --- whichseems tobethe reality of many fullyprofessionalwomenexpatriateplayersaswell,whodo notsomuchentercountriesbutclubs,clusteringwithteam matesandothermigrantplayersandoftenlivingmore vir-tualcontactsbeyondthebordersthandailylifeinteractions in theirimmediateenvironment beyondtheclub (Botelho andAgergaard,2011;Tiesler,2012b).Andstill,the mobil-ityexperienceof diasporaplayersis different,for itdoes notinvolve migration,housingand dailylife but,instead, travel, hotelsand the interruption of daily routine. They traveltotheirparents’countryoforiginataveragebetween threeandsixtimesperyearforafewweeksormeettheir squad for preparationcampsand matches at thelocation of international competitions. For some of them, joining thenational teamhadbeen thefirstoccasion tovisitthis country,which,untilthen,wasmainlyintroducedtothem by thenarratives andmemoriesof their parents whohad leftdecadesago.Still, othersknew theirancestral home-landfrommoreor lessfrequentholidayvisits. Notallare fluent speakers oftheir parents’ native languagewhich is (supposed to be) the lingua franca in the national team environment. AMexican playerwrites allkindsof Spanish footballexpressionsonherhandsandarmsbeforematches, while Portuguese playersmotivatetheir parentstoswitch the house languageto Portuguese during the daysbefore joiningtheirteam.

Diaspora players develop a greater interest for their parents’ homecountry,e.g.byaccessingmediamore fre-quently,andtheygenerallystartkeepingclosecontactwith theirnationalteamcolleaguesviaFacebookandSkype.As far as they or their parents are embedded in local eth-nic communities,their participation in the national team ofthe‘homecountry’naturallybringsattentionandpride within the community. A few diaspora players had even been cappedfor theU-17or U-19national teamsof their countriesofbirth,andstilltheytookthe(irreversible) deci-sion to accept the invitation to the senior or A national team of a lowerranking country. Some preferthe coach-ing or playing styles of the other country, many stressed the more family-like atmosphere amongthe squad or ‘to fulfilmyfathers/parents’dream’asamotive.Alldiaspora

players I spoke with mentioned that the participation in the team, which often also includes giving interviews to the press at the locale (where their connection to the countryisapopularquestion),motivatedorenabledthem ‘to connect with my roots’. Alike expatriate players and migrant college players, their ‘networks, activities and patterns of life encompass two societies’ (Glick-Schiller et al.,1992, p. 1);they create linkagesbetween institu-tions and subjectivities by being simultaneously engaged in two or more countries (Mazzucato, 2009), or, in other words,‘theirlivescutacrossnationalboundariesandbring twosocietiesintoasinglesocialfield’(Glick-Schilleretal., 1992).

Travelling

new

citizens

as

transnational

players

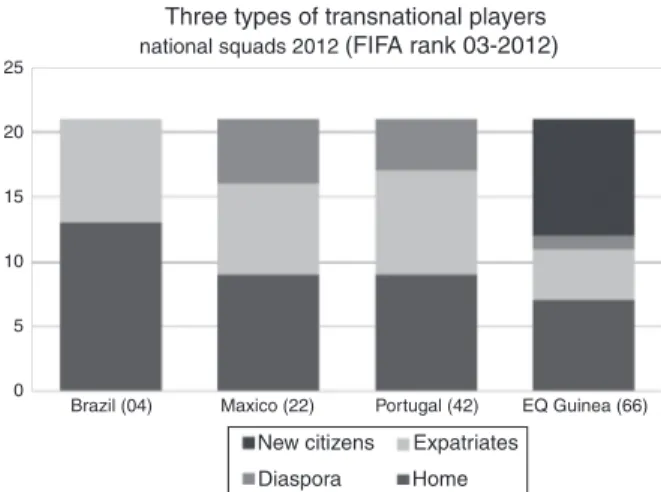

Two questionsremain whenlooking at figureswhich illus-tratethecirculationofplayerswhowereapartofboththe 2008Olympicandthe2011WWCteams.AmongtheOlympic teamsof2008,mainreceivershadbeentheUSA,Sweden, andGermany.Firstofall,in2011,Brazil,theformermere emigrationcountry,appearsasthefourthstrongestreceiver ofWWCplayers.WhogoestoBrazilandwhycanitattract foreignplayersdespitecriticalinfrastructures(Rial,2014), issuesinitschampionshipandanalreadyhugepoolofhighly skilledlocaltalenttheclubscanhardlyaccommodate? Sec-ondly,EquatorialGuineaappearsasthemainsender,albeit itonlyqualifiedtobeontheglobalstageattheWWCforthe veryfirsttimein2011.Globalstages(includingcontinental cups)areknownaskeyhubsofplayertransfers,especially inthewomen’sgamewhichstilllacksfinancialandhuman resources which would allow more systematic scoutingat theinternationallevel.Afterthe2008Olympics,six Brazil-iansmadethejumptotheUSA,joiningWPSteams.Inthe aftermathoftheWWC2011,whenboththeWPSandoneof thefewBrazilianclubsthatwasabletoprovidereasonable conditionstowomenplayers (FCSantos),folded,fourkey BraziliannationalteamplayerswenttoRussia,whileothers dispersedelsewhere.

The only Guinean-born player, who actually left her country,afterbeingrecruitedbyaforeignclub,isthe inter-nationalstarstrikerGenovevaAnonma.Shehadmovedto Germanyin2008,playingforasmallfirstdivisionwomen’s clubfortwoseasonsandwassignedbythehabitual Cham-pions League participant TurbinePotsdam after the WWC 2011.HernationalteamcountedonaEuropean-born dias-pora player for a couple of years, while another fifteen mobileplayerswhorepresentedEquatorialGuineaat inter-national matches, since it debuted in 2002, were born inCameroon,Nigeria,BurkinaFasoand,most representa-tively,inBrazil.Theywere‘scouted’andinvitedtojointhe Guinean national team and naturalised. I suggest coining this type of mobile player as new citizens. Unlike dias-pora players, they do not have ancestors in the country where they obtain citizenshipand, generally, noprevious connection to it. There are cases of naturalisation to be found regularlyin men’s football. But here, theseformer foreign players had normally lived for a certain period, sometimesforyears,inthecountrywheretheystart repre-senting the national team after naturalisation. Thus they

departed as migrants, settled as expatriate players, and then turned into citizens. This pattern requires a stable andwellorganiseddomesticleaguewhichprovidesthelegal andfinancialconditionstoattractandcontractforeign play-ers,whichisnotthecaseofEquatorialGuineainwomen’s football.

On the official FIFA List of Players at the WWC 2011, fiveoftheeightBrazilianbornplayerswerelistedwith‘no club affiliation’, two with Guinean clubs and one held a contractin SouthKorea. Anonma played in Germany;the diasporaplayerplayedinherhomecountry,thatofSpain; oneGuinean-basedplayerborn inCameroon;andanother originally from Nigeria playing in Nigeria, etc. Indeed it appearsasif the newcitizens usuallycontinue playing in the domestic league of the country were they grew up, astheirclub affiliations ---at least asdocumentedshortly beforeandagainafteraninternationalmatch---for exam-ple,there were seven Brazilian born players affiliated to Brazilianclubs.Someventurefurtherafterhavinggarnished scouts’ attention at international matches. Following Poli andBesson’s (2010) definitionof the expatriateplayer, it appearsthatonlyAnonma’smobility projectmatcheswith this concept. Players who first became new citizens and thenexpatriates in athird countrycanbe conceptualised asmobilenewcitizens.

FIFAeligibilityrulesdescribethecriteriathatareusedto determinewhetheranassociationfootballplayerisallowed to represent a particular country in officially recognised internationalcompetitionsandfriendlymatches.Inthe20th century, FIFA allowed a player to represent any national team,aslongastheplayerheldcitizenshipofthatcountry. In2004,inreactiontothegrowingtrendtowards naturalisa-tionofforeignplayersinsomecountries,FIFAimplemented asignificantnewrulingthatrequiresaplayertodemonstrate a’clearconnection’toanycountrytheywishtorepresent. InJanuary 2004, a new ruling came into effectthat per-mittedaplayertorepresentonecountryinternationallyat youthlevelandanotherattheseniorlevel,providedthatthe playerappliedtodosobeforehis/her21stbirthday(FIFA, 2009).Thatwasthe caseof anumberof diasporaplayers mentionedalongthetext,whohadplayedforU-17and U-19nationalsquadsintheirhomecountriesbeforeswitching theirFIFAnationalityinfavouroftheirparent’scountryof origin.InMarch2004,FIFAamendeditswiderpolicyon inter-nationaleligibility.Thiswasreportedtobeinresponsetoa growingtrendinmen’sfootballinsomecountries,suchas QatarandTogo,tonaturaliseplayersborninBrazil(and else-where)thathavenoapparentancestrallinks totheirnew countryofcitizenship.AnemergencyFIFAcommitteeruling judgedthatplayersmust beabletodemonstratea‘‘clear connection’’toa countrythat theyhad notbeen born in butwishedtorepresent.Thisruling explicitlystatedthat, insuchscenarios,theplayermusthaveatleastoneparentor grandparentwhowasborninthatcountryortheplayermust havebeen resident inthat countryfor at leasttwoyears (BBC Sport,2004;FIFA,2008).As notalloftheEquatorial Guineannewcitizensfulfilledthelattercondition,the orig-inallysuggested line-upof thesquadneededamendments atthelastminute.Andstill,thesquadwasabletocounton morethanonetransnationallyexperiencedplayer(Anonma) byhavingintegratedplayerswhoweresocialisedinatleast fivedifferentcountries.

25 20 15 10 5 0 Brazil (04) Maxico (22) New citizens

Three types of transnational players

national squads 2012 (FIFA rank 03-2012)

Expatriates

Home

Diaspora

Portugal (42) EQ Guinea (66)

Figure2 Differingmobilitytypesofnationalsquadplayers.

Originalfigure(bytheauthor)basedonFIFAplayerslists.

Conclusion:

three

types

of

players

who

embody

and

display

transnational

football

experience

Theopportunitytodevelopfootballexperienceina differ-ent(andusuallymoreadvancedfootball)contextisoneof the main motives of expatriate players in women’s foot-ball,besidesplayingprofessionally.AsstatedbySteadand Maguire(2000,p.36f),inrelationtomen’ssportmigration, andbyBotelhoandAgergaard(2011,p.814)inrelationto women’sfootball migration, playing football abroad ‘car-ries elements of rites of passage as it is perceived as a meanstotransformyourselfintoamorematurefootballer’ andopens up further mobility options. It is the (more or lesssuccessful)adaptationandembeddednessina cultur-allydifferent context which distinguishes this experience fromtheratherephemeralinternationalfootballexperience alsogainedby ‘‘immobile’’players viatherepresentation oftheirclubornationalsquadatinternationaltournaments. Isuggestcoiningittransnationalfootballexperience.What turnsthis(at least) bi-national football experienceintoa transnationalone is the players’ engagement in both the clubanddomesticleagueofonecountryandinthenational squadofanother.

In women’s football, this experience is perceived as overwhelminglypositiveandrewardingbytheplayers them-selvesandmostsocialagentsinvolvedintheprocess.Asover 80percentofthecountrieswhichsendtheirnationalsquads intointernational competitions donot(yet) provide well-organised,sufficientlycompetitivedomesticleagueswhich canpreparetheirplayerstoconfronttheleadingladysoccer nations,itcomesasnosurprisethatinmostlowerranking countriestheirexpatriatesarethekeyplayersofthesquad. Becausetheyareplayingabroad,theyareinbetter physi-calshape,haveimprovedtechnicalskills,andhavegained broaderknowledge and embodiedexperience ofdifferent tacticsandsystemsofthegameassuch.Transnational foot-ballexperience,however,is notonlycomprisedofgaining bodilycapital‘‘abroad’’,suchasimprovedtechnicalskills andphysical shape derived fromthe rareprivilege in the women’sgameofanexclusivededicationtofootball,from dailypracticeandregularhighlevelcompetitioninabetter

organisedleague.Decisivearetwomoreaspects:agreater maturityasaplayerandabroaderknowledgeofthegame derivedexperienceinasocio-culturallydistinctcontext.

Therecognitionoftheselatteraspectsandconsequent requestfortransnationalfootballexperienceispointedout bythefactthatevenhigherrankingcorecountries,which had competed at the 2008 Olympics, support the mobil-ity of their key national squad players. The same holds true for the World Cup Champion of 2011, Japan. Albeit running a semi-professional league (the L. League) since 1989, where allactual and potentialnational squad play-ersarecontractedasprofessionals,theJapaneseFederation has in recent years switched to a pro-emigration policy (Labbert,2011;Takahashi,2014).Consequently,itwasable tocompriseitsWWCsquadwithtransnationallyexperienced players who held contracts with premier league clubs in othercorecountries,suchastheUSA,GermanyandSweden. Once amobile playergets cappedfor her/his national squad,s/heisactinginatleasttwoculturally andsocially differentfootball contexts, atthe sametime,andis con-fronted with different types of expectations, behavioural codesandcustoms.Theconceptofthetransnationalplayer referstoher/hisembodiedknowledgeofthegamederived fromgeographicalmobilityandrespectivesubjective expe-rience.Atleastinwomen’sfootball,andaccordingtoour interviewswithplayersandcoaches,itisregardedasatype ofsocio-sportingcapitalresourcethattheplayerbringsinto herteam(clubandnationalsquad).

Transnationallyexperiencedplayersinmen’sfootballare firstand foremostexpatriateplayerswholeave the coun-trywheretheygrewupfollowingtherecruitmentofaclub abroad(PoliandBesson,2010).Duetothefarlessadvanced developmental stage, this is different in the women’s game.Ambitiousnewcomersamongthesemi-peripheraland peripheralcountriesintegratemigrantcollegeplayers,new citizensanddiasporaplayersinordertoimprovethe perfor-manceoftheirnationalwomen’steams.Ifonecomparesthe mobilityprojectsoftheseplayerswhoarecrossingborders it becomesclearthat notall ofthem areactual migrants liketheexpatriateplayer(Fig.2).

College players who gain a soccer scholarship in the USAdosharetheexperienceofmigrationwithexpatriates by moving and settling away fromhome and facing chal-lengesofadaptationalsobeyondthesocialfieldoffootball. Unlikeexpatriateplayerstheydonotfollowtherecruitment of a club. They might become professionals, or not, just like young male players wholeave home in ordertojoin afootballacademyabroad---albeitthelatterarefacinga prematureprofessionalismatan earlyagewhich is gener-ally not the case of young women footballers in college. Amongsttransnationallyexperienced footballers,Isuggest thegathering ofexpatriate,migrantcollegeandacademy playersintoonegroup,namelytheonewithactualmigration experience.

AsthetypeofmobileplayerthatIcoinnewcitizen nat-uralises her/himself following the invitation of a federal footballassociationabroadtojoinitsnationalsquad,s/he can hardly beregarded as an expatriate.As we stilllack sufficientqualitativedata,thequestionof whetherornot theythemselvesconsidertheirmobilityprojectasincluding theexperienceofmigrationorrathertheoneofatraveller, remainsopen.

The question of ifthe migration experience is part of their football mobility project was clearly answered by intervieweesfromdiverse countrieswhich matchwiththe conceptofthediasporaplayer.Theseplayerswhowereborn andsocialisedinadvancedgirlsandwomensoccersystems, andprovidetheirskills tothenationalsquadofthe coun-tryoforiginoftheirparentscannotbeconsideredmigrants. Apartfromvisitingtheirancestors’homelandinordertojoin theirsquad fortrainingcamps andinternationalmatches, theycontinuelivingandplayingfootballintheircountryof birth.Theirmobilityprojectsdonotinvolvemigration, hous-inganddailylifebuttravel,hotelsandtheinterruptionof dailyroutine.

Whatallthesetypesofmobilewomenfootballershavein commonisthattheygainanddisplaytransnationalfootball experienceinatleasttwodifferingsocialculturalcontexts. As an umbrella category of mobile footballers which, in contrary tothe maleideal typeof expatriate player, can includecurrentrealitiesofthewomen’sgame,theconcept ofthe transnationalplayerappears useful.Itgrasps three subcategories: Firstly, because theyare numericallymost significant,indeedthat oftheexpatriateplayer,including pre-professionalyouth,suchasmigrant academyand col-legeplayers.Newcitizensanddiasporaplayersthenpresent the second and third subcategory. These might vanish in the futureoncethe productionof the women’sgame has furtherdeveloped throughcommercialisationand thestill youngprofessionalisationprocess.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthordeclaresnoconflictsofinterest.

References

AgergaardS, BotelhoV.‘Femalefootball migration.Motivational factorsforearlymigratoryprocesses’.In:MaguireJ,FalcousM, editors.Sportandmigration.Borders,boundariesandcrossings. London:Routledge;2010.p.157---72.

AgergaardS,TieslerNC.Currentfluxesinwomen’ssoccermigration: towardsanunderstandingofcircularityofathletemobilityand skills-exchange.In:AgergaardS,TislerNC,editors.Women, soc-cerandtransnationalmigration.London,NewYork:Routledge; 2014a.p.33---49.

AgergaardS,TieslerNC.Women,soccerandtransnational migra-tion.London,NewYork:Routledge;2014b.

Agergaard S, Botelho VL, Tiesler NC. The typology of ath-leticmigrantsrevisited:transnationalsettlers,sojournersand mobiles.In:AgergaardS,TislerNC,editors.Women,soccerand transnationalmigration.London,NewYork:Routledge;2014.p. 191---215.

BaleJ,MaguireJ.Theglobalsportsarena:athletictalentmigration inaninterdependentworld.London:Cass;1994.

BBCSport.‘Fifarulesoneligibility’,BBCSport[materialda inter-net] 18 March 2004. Disponível em: http://news.bbc.co.uk/ sport1/hi/football/africa/3523266.stm,retrievedon27January 2012.

BessonR,Poli R,Ravenel L.Demographicstudyoffootballersin Europe2011.Lausanne:PFPO;2011.

Booth S, Liston K. The continental drift to a zone of prestige: women’ssoccermigrationtotheUSNCAADivisionI2000---2010. In:AgergaardS,TislerNC,editors.Women,soccerand transna-tionalmigration.London,NewYork:Routledge;2014.p.53---72.

BotelhoVL,AgergaardS.Movingfor theloveofthegame? Inter-national migration of female footballers into Scandinavian countries.SoccerSoc2011;12(6):806---19.

FIFA4th. FIFAWomen’s Football Symposium [material da inter-net];2007[retrived on13July2009].Disponível em:http:// www.fifa.com/aboutfifa/developing/women/symposium/index. html

FIFA. FIFAStatutes, Section VII, Article 16: Nationality entitling players torepresentmorethanone Association.[materialda internet];2008[retrievedon27January2012]Disponívelem: http://www.fifa.com/mm/document/affederation/generic/ 01/09/75/14/fifa statutes072008en.pdfeditionMay2008. FIFA. ‘Protect the game, protect the players, strengthen

global football governance # Change of association’, FIFA [material da internet]; 3 June 2009 [retrieved on 27 January 2012]. Disponível em: http://www.fifa.com/ aboutfifa/organisation/bodies/news/newsid=1065926

Glick-SchillerN,BaschL,Blanc-SzantonG.Towardsatransnational perspectiveonmigration:Race,class,ethnicityandnationalism reconsidered.NewYorkAcademyofScience:NewYork;1992. Grainey T. ‘Women’s football: North Americans on a

mis-sion as ‘new Portuguese’’ [material da internet]; 2008 [retrievedon29December2009].Disponívelem:http://www. theglobalgame.com/blog/category/womens-football

LabbertA. Japan:Signale an dieHeimat. In: Elf Freundinnen ---MagazinfürFrauenfußball;2011.p.62---3,june.

LanfranchiP,TaylorM.Movingwiththeball:themigrationof pro-fessionalfootballers.Oxford:Berg;2001.

MageeJ,Sugden J.Theworld attheir feet--- professional foot-ball and international labor migration. J Sport Soc Issues 2002;26(4):421---37.

Maguire J. Global sport: identities, societies civilizations. Cambridge:PolityPress;1999.

MaguireJ.Sportlabourmigration researchrevisited.JSportSoc Issues2004;28(4):477---82.

MaguireJ,FalcousM.Sportandmigration:borders,boundariesand crossings.London:Routledge;2010.

Maguire J, Stead D. Far pavilions?: cricket migrants, foreign sojournsandcontestedidentities.IntRevSocSport1996;31(1): 1---23.

Mazzucato V. Informal insurance arrangements in Ghana-ian migrants’ transnational networks: the role of reverse remittances and geographic proximity. World Dev 2009;37(6):1105---15.

McCreeR. Student athleticmigration from Trinidad and Tobago: thecaseofwomen’ssoccer.In:AgergaardS,TislerNC,editors. Women,soccerandtransnationalmigration.London,NewYork: Routledge;2014.p.73---85.

PfisterG,KleinML,TieslerNC.‘Momentoussparkorenduring enthu-siasm? The 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup and its impact on players’mobility andon thepopularityofwomen’ssoccerin Germany.In:AgergaardS,TislerNC,editors.Women,soccerand transnationalmigration.London,NewYork:Routledge;2014.p. 140---58.

PoliR,BessonR.‘FromtheSouthtoEurope:acomparativeanalysis ofAfricanandLatinAmericanfootballmigration’.In:Maguire J,FalcousM,editors.Sportandmigration.Borders,boundaries andcrossings.LondonandNewYork:Routledge;2010.p.15---30. PortesA.Immigrationtheoryforanewcentury:someproblemsand

opportunities.IntMigrRev1997;31(4):799---825.

Reyes BI. Immigrant trip duration:the caseof immigrants from WesternMexico.IntMigrRev2001;35(4):1185---94.

RialC.Rodar:acirculac¸ãodosjogadoresdefutebolbrasileirosno exterior.HorizontesAntropológicos2008;14(30):21---65. Rial C. New frontiers: the transnational circulation of Brazil’s

women socer players. In: Agergaard S, Tisler NC, editors. Women,soccerandtransnationalmigration.London,NewYork: Routledge;2014.p.86---101.

SteadD,MaguireJ.Ritedepassageorpassagetoriches?The moti-vationandobjectivesofnordic/scandinavianplayersinEnglish LeagueSoccer.JSportSocIssues2000;24(1):36---60.

TakahashiY.Nadeshiko:InternationalmigrationofJapanesewomen inworldsoccer.In:AgergaardS,TislerNC,editors.Women, soc-cerandtransnationalmigration.London,NewYork:Routledge; 2014.p.102---16.

TannenbaumM.Backand forth:immigrants’stories ofmigration andreturn.IntMigr2007;45:147---75.

Tiesler NC. Selected data: two types of women football migrants: diaspora player and emigrants. Foomi-net Online Sources; 2010. Disponível em: http://diasbola.com/ PDF/report/TIESLER Selected%20DataTwo%20Types%20of%20 Women%20Football%20Migrants.pdf

Tiesler NC. Main trends and patterns in women’s football migration. Foomi-net Online Sources; 2011. Disponível em: http://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/6139/1/ICSNCTieler

MainTrendsSITEN.pdf

Tiesler NC. Um grande salto para um país pequeno: O êxito das jogadorasportuguesas na migrac¸ão futebolística interna-cional.In:TieslerNC,DomingosN,editors.OFutebolPortuguês. Política,GéneroeMovimento.Porto:Afrontamento;2012a.p. 221---46.

Tiesler NC. Mobile Spielerinnen als Akteurinnen im Global-isierungsprozessdesFrauenfußballs.In:SobiechG,OchsnerA, editors.SpielenFraueneinanderesSpiel?Geschichte, Organisa-tion,RepräsentationenundkulturellePraxenimFrauenfußball. Berlin:VS-Verlag;2012b.

TieslerNC,CoelhoJN.Globalisedfootball.Nationsandmigrations, thecityandthedream.London,NewYork:Routledge;2008. Trumper R, Wong LL. ‘Transnational athletes: celebrities and

migrantplayersinfútbolandhockey’.In:MaguireJ,FalcousM, editors.Sportandmigration.Borders,boundariesandcrossings. London,NewYork:Routledge;2010.p.230---44.

VertovecS.Migranttransnationalismandmodesoftransformation. IntMigrRev2004;38(3):970---1.