ISEG

-

L

ISBON

S

CHOOL OF

E

CONOMICS

&

M

ANAGEMENT

Multichannel Consumer Behaviors in the Mobile

Environment: Mapping the Decision Journey and

Understanding Webrooming Motivations

Susana Catarina de Jesus Fernandes dos Santos

Advisor: Professor Helena do Carmo Milagre Martins Gonçalves, Ph.D.

Thesis for obtaining a Doctoral Degree in Management

I

U

NIVERSIDADE DE

L

ISBOA

ISEG

-

L

ISBON

S

CHOOL OF

E

CONOMICS

&

M

ANAGEMENT

Multichannel Consumer Behaviors in the Mobile

Environment: Mapping the Decision Journey and

Understanding Webrooming Motivations

Susana Catarina de Jesus Fernandes dos Santos

Advisor: Professor Helena do Carmo Milagre Martins Gonçalves, Ph.D.

Thesis for obtaining a Doctoral Degree in Management

Jury Chairman:

Professor Nuno João Oliveira Valério, Ph.D. - Professor Catedrático e Presidente do Conselho Científico, Instituto Superior de Economia e Gestão, Universidade de Lisboa Jury Members:

Professor Helena do Carmo Milagre Martins Gonçalves, Ph.D. – Professora Associada com agregação, Instituto Superior de Economia e Gestão, Universidade de Lisboa

Professor Maria Margarida de Melo Coelho Duarte, Ph.D. – Professora Associada, Instituto Superior de Economia e Gestão, Universidade de Lisboa

Professor Pedro Quelhas Brito, Ph.D. – Professor Auxiliar com agregação, Faculdade de Economia, Universidade do Porto

Professor Filipe Jorge Fernandes Coelho, Ph.D. – Professor Auxiliar com agregação, Faculdade de Economia, Universidade de Coimbra

Professor Maria Teresa Pinheiro de Melo Borges Tiago, Ph.D. – Professora Auxiliar com agregação, Faculdade de Economia e Gestão, Universidade dos Açores

Support from the Doctoral Scholarship Program by Universidade de Lisboa and ISEG Support for conference expenses by FCT (through ADVANCE/CSG)

Support for participant compensation by CEGE

2020

III

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author gratefully thanks Universidade de Lisboa and ISEG - Lisbon School of Economics and Management for funding this research under the 2015 Doctoral Scholarship Program.

The author also wishes to acknowledge the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT), under the project name UID/SOC/04521/2013, and Centro de Estudos de Gestão (CEGE) for supporting the research. Financial support from FCT was given through ADVANCE/CSG - Centro de Investigação Avançada em Gestão do ISEG.

IV Agradeço…

À Professora Helena Martins Gonçalves pela orientação, exigência e motivação para o desenvolvimento deste trabalho. Mas mais ainda pelo carinho, amizade e palavras de apoio num período negro durante esta jornada. Nunca me esquecerei.

À Professora Graça Miranda Silva e ao Professor Rui Brites pela tutoria em métodos de análise. Os comentários e sugestões foram valiosos.

Ao meu companheiro e à minha mãe… Para vocês não há sequer palavras para agradecer. Estiveram lá quando soube o diagnóstico. Em cada sessão de quimioterapia, consulta e exame. Quando o cabelo caiu e nos momentos em que achei que o meu corpo que ainda não tinha chegado aos 30 me ia falhar. Em todas as minhas incertezas e angústias. Deram-me força para continuar e acabar o que tinha coDeram-meçado. Nunca teria conseguido sem vocês. Ao meu irmão, sabes que estás incluído. Amo-vos.

Aos meus amigos, que demonstraram total apoio. Muito obrigada.

E, por fim…

Ao meu querido pai. Tu e a Mãe ensinaram-me a resiliência. Sentirei sempre a tua falta, não importa quantos anos passem.

V

Nunca desistas. És mais forte do que pensas.

VII

ABSTRACT

With recent technological developments, understanding how consumers behave in the current mobile environment has gained interest in multichannel research. To narrow knowledge gaps, two main research objectives are proposed: mapping actual and holistic consumer decision journeys and analyzing webrooming-specific motivations.

The decision journey mapping, which relied on qualitative data, was performed for two product categories of different involvements. An adapted sequential incident technique that combines diaries and personal interviews was applied, and the data was analyzed recurring to sequence and contingency analyses. The sequence analysis shows that more and more variable touchpoints and activities exist for the high involvement product, and journey sequences are more complex and dynamic. The contingency analysis indicates that some touchpoints are more appropriate than others for certain activities, varying also by decision stage. Both sequence and contingency analyses are combined to arrive at four decision maps for each product category.

The webrooming analysis, solely done for the high involvement product category, examines how specific motivations derived from information-processing and uncertainty-reduction theories determine three webrooming types: traditional webrooming, webrooming extended to include mobile devices, and multidevice webrooming. The data, obtained from personal and online surveys, was examined using discriminant analysis and fsQCA. The discriminant analysis indicates a significantly positive effect of information attainment on explaining all behaviors, and price comparison orientation and empowerment for mobile-related behaviors. FsQCA findings show various motivational configurations for each webrooming behavior. In nearly all, both information-processing and uncertainty-reduction motivations exist, supporting the importance of the underlying theories in explaining webrooming. Moreover, empowerment is more relevant in behaviors where mobile devices are always used.

This study enriches the theoretical body of consumer multichannel behavior and the webrooming construct particularly. The results can guide multichannel managers in developing differentiated strategies that address various consumer groups and particular webroomer-specific needs.

Keywords: Multichannel consumer behavior, Consumer decision journey mapping,

VIII

RESUMO

Com os recentes desenvolvimentos tecnológicos, compreender como os consumidores se comportam no atual ambiente mobile tem ganho interesse na investigação multicanal. Para encurtar lacunas no conhecimento, dois objetivos principais são propostos: mapear reais e completas jornadas de decisão e analisar motivações específicas do webrooming.

O mapeamento da jornada de decisão, baseado em dados qualitativos, foi realizado para duas categorias de produto com diferentes envolvimentos. Foi aplicada uma técnica sequencial de incidentes adaptada que combina diários e entrevistas pessoais, e os dados foram analisados recorrendo às análises sequencial e contingencial. A análise sequencial mostra que existem mais e mais variados touchpoints e atividades para o produto de alto envolvimento, e as sequências das jornadas são mais complexas e dinâmicas. A análise contingencial indica que alguns touchpoints são mais apropriados para certas atividades do que outros, variando também por etapa de decisão. Da combinação das análises sequencial e contingencial obtêm-se quatro mapas de decisão por produto.

A análise do webrooming, realizada somente para produtos de alto envolvimento, examina como motivações específicas derivadas das teorias de processamento de informação e redução de incerteza determinam três comportamentos webrooming:

webrooming tradicional, webrooming estendido para incluir dispositivos móveis e webrooming multidispositivo. Os dados, obtidos de questionários pessoais e online,

foram examinados usando análise discriminante e fsQCA. A análise discriminante indica um efeito significativamente positivo da obtenção de informações na explicação de todos os comportamentos, e da orientação para a comparação de preços e empowerment para comportamentos incluindo dispositivos móveis. O fsQCA mostra várias configurações motivacionais para cada comportamento webrooming. Em quase todas, existem motivações relacionadas com as teorias de processamento de informação e redução de incerteza, suportando a importância destas em explicar o webrooming. Ademais,

empowerment é mais relevante em comportamentos incluindo sempre dispositivos

móveis.

Este estudo enriquece o corpo teórico do comportamento multicanal do consumidor e do construto webrooming, em particular. Os resultados podem orientar gestores multicanal a desenvolver estratégias diferenciadas que atendam a vários grupos de consumidores e a necessidades específicas dos webroomers.

Palavras-chave: Comportamento multicanal do consumidor, Mapeamento da jornada de

IX CONTENTS 1. Introduction ... 1 1.1. Background ... 1 1.2. Research gaps ... 4 1.3. Research objectives ... 8 1.4. Research design ... 10 1.5. Main conclusions ... 12 1.6. Research contributions ... 13 1.7. Research outcomes ... 15 1.8. Summary of chapters ... 15 2. Literature Review ... 18 2.1. Introduction ... 18

2.2. Consumer multichannel behavior research ... 19

2.2.1. The discipline of consumer multichannel behavior ... 19

2.2.2. Channels and their roles ... 20

2.2.3. Evolution in multichannel behavior studies ... 21

2.2.3.1. Theoretical perspectives in multichannel behavior studies ... 22

2.2.4. Consumer experience and the consumer decision journey ... 23

2.2.5. Antecedents and consequents of consumer cross-channel behaviors ... 24

2.2.6. Mobile channel usage in multichannel settings ... 25

2.2.7. The focus of the thesis ... 26

2.2.8. Omnichannel retailing ... 27

2.3. The consumer decision journey ... 29

2.3.1. A multichannel perspective on consumer decision journeys ... 29

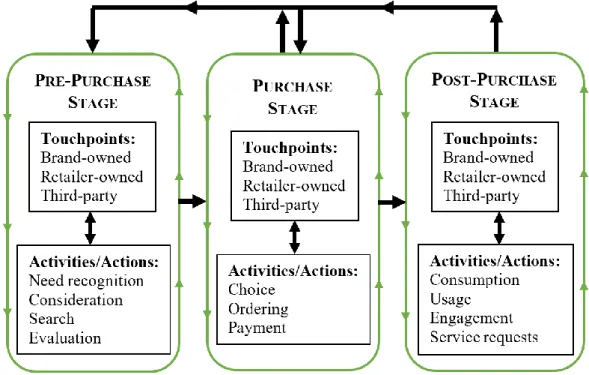

2.3.2. Consumer journey elements ... 30

2.3.3. Consumer decision-making processes ... 31

2.3.3.1. Consumer behavior research ... 32

2.3.3.2. Decision science research... 37

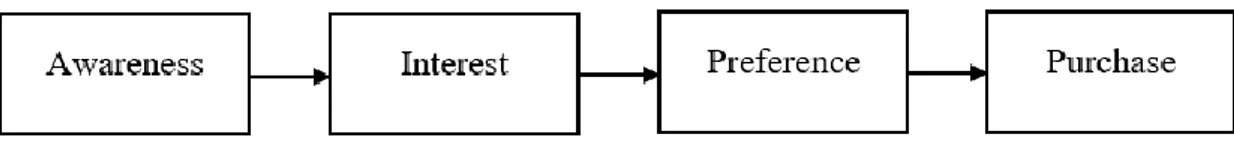

2.3.3.3. Hierarchy of effects research... 40

2.3.3.4. A consumer decision-making shift ... 45

2.3.4. Consumer channels and touchpoints ... 48

2.3.4.1. Touchpoints and their relation to channels ... 48

2.3.4.2. Classification of touchpoints ... 50

X

2.3.4.4. Linking touchpoints and decision-making stages ... 54

2.4. Multichannel motivations and the webrooming phenomena ... 56

2.4.1. Consumer motivations ... 56

2.4.2. Consumer motivations for channel choice ... 57

2.4.2.1. Motivations specific to online and offline usage ... 57

2.4.2.2. Online and offline lock-ins and synergies ... 58

2.4.2.3. Channel attributes ... 60

2.4.2.4. Psychological dimensions and consumer goals ... 61

2.4.2.5. Mobile device usage and multichannel motivations ... 62

2.4.3. Theoretical models and investigative approaches in multichannel motivational research ... 64

2.4.4. Motivational idiosyncrasies in multichannel behaviors ... 65

2.4.5. The importance of studying webrooming ... 66

2.4.6. Webrooming-specific theories and motivations ... 68

2.4.6.1. Mobile device usage and webrooming ... 70

2.5. Factors that impact decision-making and multichannel behavior... 71

2.5.1. Product characteristics and involvement with the product category ... 71

2.5.2. Memory and prior knowledge ... 75

2.5.3. Consumer characteristics ... 77

2.5.4. Other factors influencing consumer decision-making and multichannel behavior ... 78

2.6. New paradigms in consumer multichannel behavior research ... 78

2.6.1. Consumer decision journey mapping ... 79

2.6.2. Exploration of webrooming-specific motivations ... 80

2.7. Chapter summary ... 81

3. Conceptual Model ... 83

3.1. Introduction ... 83

3.2. Consumer decision journey mapping... 84

3.2.1. Proposed conceptual model for mapping the consumer decision journey 86 3.2.2. Touchpoints and channels of the conceptual model ... 89

3.2.3. Stages, activities, and actions of the conceptual model ... 91

3.2.4. Linkage between touchpoints and activities in the conceptual model... 94

3.2.4.1. Dimensions to assess touchpoint and activity linkage ... 96

3.3. Webrooming motivational analysis ... 98

3.3.1. Proposed conceptual model for examining webrooming-specific motivations ... 98

XI

3.3.2. Webrooming behaviors... 101

3.3.3. Webrooming motivations ... 101

3.3.3.1. Information-processing motivations ... 102

3.3.3.2. Uncertainty-reduction motivations ... 104

3.4. Context of the study ... 106

3.4.1. Selected markets for the research ... 106

3.4.2. Product categories for each research objective... 108

3.4.3. Expected variations in consumer decision journey maps for different product involvement levels ... 109

3.5. Chapter summary ... 110

4. Research Methodology ... 112

4.1. Introduction ... 112

4.2. Theoretical paradigms ... 112

4.3. Research approaches ... 115

4.4. Consumer decision journey analysis ... 117

4.4.1. Research design ... 117

4.4.2. Sampling ... 119

4.4.3. Data collection ... 123

4.4.4. Data analysis ... 128

4.4.5. Quality criteria assessment ... 133

4.5. Webrooming motivation analysis ... 139

4.5.1. Research design ... 139

4.5.2. Sampling ... 140

4.5.3. Data collection ... 143

4.5.4. Data analysis ... 147

4.5.4.1. Data preparation ... 147

4.5.4.2. Data analysis strategy ... 149

4.5.5. Quality criteria assessment ... 151

4.6. Chapter summary ... 156

5. Results and Discussion ... 157

5.1. Introduction ... 157

5.2. Consumer decision journey analysis ... 158

5.2.1. Analysis of touchpoints, activities, and sequential interactions ... 158

5.2.1.1. Touchpoints and channels ... 159

5.2.1.2. Activities and tasks... 167

XII

5.2.2. Linkages between touchpoints/channels and activities/stages ... 186

5.2.2.1. Activities and touchpoint frequency ... 186

5.2.2.2. Activities and touchpoint positivity ... 192

5.2.2.3. Activities and touchpoint importance ... 196

5.2.2.4. Touchpoint appropriateness for activities ... 199

5.2.3. Decision journey maps ... 204

5.3. Webrooming motivation analysis ... 213

5.3.1. Discriminant analysis ... 213

5.3.2. Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis ... 215

5.3.2.1. Calibration ... 215

5.3.2.2. Analysis of necessary and sufficient conditions ... 217

5.3.3. Webrooming-specific motivations: comparison of results ... 220

5.4. Chapter summary ... 224 6. Conclusion ... 225 6.1. Research contributions ... 229 6.1.1. Theoretical contributions ... 229 6.1.2. Methodological contributions ... 232 6.1.3. Managerial implications ... 233

6.2. Limitations and suggestions for further research ... 237

7. References ... 240

Appendixes ... 261

Appendix 1 – Most emphasized offline touchpoints and their relation to some classification approaches. ... 261

Appendix 2 – Most emphasized online touchpoints and their relation to some classification approaches. ... 262

Appendix 3 – Email content disclosing the consumer decision journey study for participant recruitment. ... 263

Appendix 4 – Registration form for the recruitment in the consumer decision journey study (from Qualtrics). ... 264

Appendix 5 – Consent form. ... 266

Appendix 6 – Demographic profile of the sample respondents (decision journey analysis). ... 268

Appendix 7 – Example of an iOS and Android Experience Fellow report sheet and indications on how to report. ... 269

Appendix 8 – Coding scheme (only higher-order categories and codes). ... 270

Appendix 9 – Demographic profile of the sample respondents (webrooming analysis). ... 271

XIII

Appendix 10 – Measurement scales for the independent variables (conditions). ... 272 Appendix 11 – Assessment of the assumptions of the discriminant analysis... 273 Appendix 12 – Construct correlations and discriminant validity. ... 275 Appendix 13 – Response/non-response analysis. ... 275 Appendix 14 – Analysis of predictive validity for webext (extended webrooming).

... 276

Appendix 15 – Examples of pictures of retailer touchpoints shared in the smartphone

diary (Participant 21). ... 277

Appendix 16 – Picture of a third-party touchpoint shared in a smartphone diary

(Participant 21). ... 278

Appendix 17 – Picture of a retailer touchpoint shared in a soft drink diary

(Participant 1). ... 279

Appendix 18 – Frequency of touchpoints for pre-purchase-related activities

(smartphone purchase). ... 279

Appendix 19 – Frequency of touchpoints for purchase-related activities (smartphone

purchase). ... 284

Appendix 20 – Frequency of touchpoints for post-purchase-related activities

(smartphone purchase). ... 285

Appendix 21 – Frequency of touchpoints for pre-purchase-related activities (soft

drink purchase). ... 286

Appendix 22 – Frequency of touchpoints for purchase-related activities (soft drink

purchase). ... 287

Appendix 23 – Frequency of touchpoints for post-purchase-related activities (soft

drink purchase). ... 287

Appendix 24 – Positivity of touchpoints for pre-purchase-related activities

(smartphone purchase). ... 288

Appendix 25 – Positivity of touchpoints for purchase-related activities (smartphone

purchase). ... 291

Appendix 26 – Positivity of touchpoints for post-purchase-related activities

(smartphone purchase). ... 293

Appendix 27 – Positivity of touchpoints for pre-purchase-related activities (soft

drink purchase). ... 294

Appendix 28 – Positivity of touchpoints for purchase-related activities (soft drink

purchase). ... 295

Appendix 29 – Positivity of touchpoints for post-purchase-related activities (soft

drink purchase). ... 295

Appendix 30 – Importance of touchpoints for pre-purchase-related activities

(smartphone purchase). ... 296

Appendix 31 – Importance of touchpoints for purchase-related activities (smartphone

XIV

Appendix 32 – Importance of touchpoints for post-purchase-related activities

(smartphone purchase). ... 301

Appendix 33 – Importance of touchpoints for pre-purchase-related activities (soft drink purchase). ... 302

Appendix 34 – Importance of touchpoints for purchase-related activities (soft drink purchase). ... 303

Appendix 35 – Importance of touchpoints for post-purchase-related activities (soft drink purchase). ... 303

Appendix 36 – Necessity analysis. ... 304

Appendix 37 – Truth tables for each webrooming outcome. ... 305

List of Tables Table 1.1 – Research gaps and research objectives……….……...9

Table 2.1 – Multichannel and omnichannel retailing strategies (adapted from Juaneda-Ayensa et al. (2016)) ………...…28

Table 2.2 – Communication outcomes created from various communication options (Batra & Keller, 2016) ……….53

Table 2.3 – Strengths of various communication options throughout the decision journey (Batra & Keller, 2016) ……….55

Table 2.4 – Different consumer purchase behaviors (adapted from Kotler and Armstrong (2012) and Solomon et al. (2006)) ………...73

Table 3.1 – Touchpoints of the conceptual model, based on Baxendale et al. (2015) …..89

Table 4.1 – Sample matrix and quotas ………...123

Table 4.2 – Codification and summary data for dependent variables (outcomes) …...148

Table 4.3 – Comparison between DA and fsQCA (Fiss, 2011; Ragin, 2008; Woodside, 2018) ……….151

Table 5.1 – Brand-owned touchpoints (smartphone purchase) ………...160

Table 5.2 – Retailer-owned touchpoints (smartphone purchase) ………..161

Table 5.3 – Third-party touchpoints (smartphone purchase) ……….162

Table 5.4 – Brand-owned touchpoints (soft drink purchase) ……….165

Table 5.5 – Retailer-owned touchpoints (soft drink purchase) ………..166

Table 5.6 – Third-party touchpoints (soft drink purchase) ………167

Table 5.7 – Pre-purchase activities/tasks (smartphone purchase) ……….168

Table 5.8 – Purchase activities/tasks (smartphone purchase) ………169

XV

Table 5.10 – Pre-purchase activities/tasks (soft drink purchase) ………...171

Table 5.11 – Purchase activities/tasks (soft drink purchase) ……….171

Table 5.12 – Post-purchase activities/tasks (soft drink purchase) ……….172

Table 5.13 – Sequence of each decision journey in terms of touchpoints (events) related to each participant (outcomes) (smartphone purchase) ………..174

Table 5.14 – Motivating forces for the need to purchase not related with touchpoints (smartphone purchase) ………..175

Table 5.15 – Number of retailers contacted per individual (smartphone purchase) …...177

Table 5.16 – Sequence of each decision journey in terms of touchpoints (events) related to each participant (outcomes) (soft drink purchase) ……….182

Table 5.17 – Motivating forces for the need to purchase not related with touchpoints (soft drink purchase) ………..183

Table 5.18 – Touchpoint positivity frequencies (smartphone purchase) ………...192

Table 5.19 – Touchpoint positivity frequencies (soft drink purchase) ………..195

Table 5.20 – Touchpoint importance frequencies (smartphone purchase) ………196

Table 5.21 – Touchpoint importance frequencies (soft drink purchase) ………198

Table 5.22 – Summary of touchpoint appropriateness for activities (smartphone purchase) ………...200

Table 5.23 – Summary of touchpoint appropriateness for activities (soft drink purchase) ………...202

Table 5.24 – Discriminant analysis results ………214

Table 5.25 – Summary data for independent variables (conditions) ………..216

Table 5.26 – Sufficiency analysis ……….218

Table 5.27 – Summary of DA and fsQCA results and corresponding propositions …223 List of Figures Figure 2.1 – Research areas of the thesis ………...27

Figure 2.2 – Underlying research elements of the consumer decision journey …………31

Figure 2.3 – Traditional decision-making process model (adapted from Butler and Peppard (1998)) ………...37

Figure 2.4 – Main stages of decision-making models in decision science research (adapted from Karimi et al. (2015) and Hall (2008)) ………....40

Figure 2.5 – Stages of hierarchy of effects models (adapted from De Bruyn and Lilien (2008) and Lavidge and Steiner (1961)) ………...…...44

XVI

Figure 2.6 – Consumer decision-making journey (Court et al., 2009) ……….46 Figure 2.7 – Types of purchase behaviors (Solomon et al., 2006) ………...72 Figure 3.1 – Conceptual model of the consumer decision journey (based on Baxendale et

al. (2015) and Lemon and Verhoef (2016)) ……….87

Figure 3.2 – Conceptual model of motivations explaining different webrooming

behaviors ……….99

Figure 4.1 – Comparison of paradigms on the ontological and epistemological continuum

(Järvensivu and Törnroos, 2010) ………...113

Figure 4.2 – Sequential incident technique (adapted from Jüttner et al., 2013) ……….118 Figure 4.3 – Analytical process of the consumer decision journey analysis (based on

Bardin (2013) and Krippendorff (2004)) ………...133

Figure 5.1 – Decision map of the online-prone shopper (smartphone purchase) ..…….205 Figure 5.2 – Decision journey map of the multichannel enthusiastic research shopper

(smartphone purchase) ………..206

Figure 5.3 – Decision journey map of the offline-focused shopper (smartphone purchase)

………...207

Figure 5.4 – Decision journey map of the third-party dependent shopper (smartphone

purchase) ………...208

Figure 5.5 – Decision journey map of the restaurant purchaser (soft drink purchase) ...211 Figure 5.6 – Decision journey map of the pre-store decider (soft drink purchase) ……211 Figure 5.7 – Decision journey map of the in-store price sensitive buyer (soft drink

purchase) ………...211

Figure 5.8 – Decision journey map of the multichannel price sensitive buyer (soft drink

1

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background

Consumers search for information, purchase products, and connect with organizations through an ever-increasing number of channels and touchpoints. With the recent diffusion of digital technologies, the usage of mobile Internet devices, social media, and online review websites is now commonly added to more traditional but still very important touchpoints and channels, such as brick-and-mortar stores, call centers, emails, and online retailer websites. Mobile device usage, in particular, has expanded rapidly (Park & Lee, 2017). While smartphone and tablet worldwide penetration rates have reached 17.8% and 41.5% in 2019, respectively, in 2021 the forecast is near 20% and 50% for the corresponding devices (Statista, 2020a; 2020b). According to Zenith (2017), most of Internet access will be made through these devices, including information and purchase-related activities. Currently in Europe, although 74% of consumers continue to use computers, 71% use smartphones, 36% tablets, and 71% admit being multidevice users (Google Consumer Barometer, 2017).

Taking advantage of channel-specific attributes, consumers prefer and utilize different information and distribution channels at different stages of their purchase process to better satisfy their shopping needs (Verhoef, Neslin, & Vroomen, 2007). As a consequence, those using multiple channels during the decision-making process are defined as multichannel consumers (Frasquet, Mollá, & Ruiz, 2015). Although brick-and-mortar stores serve consumers’ need for instant gratification and physical touch through immediate evaluation and purchase (Brynjolfsson, Hu, & Rahman, 2013), location issues may undermine efficient product information gathering (Alba et al., 1997). The Internet, on the other hand, has unique characteristics that allow large quantities of detailed information and recommendations to be accessed from a number of online sources rapidly

2

at any time, entailing lower search costs (Kaufman-Scarborough & Lindquist, 2002). Information of different and unknown retailers can be gathered and evaluated simultaneously, and subsequent purchase of products conveniently made. The Internet also enables easy engagement in post-purchase advocacy, review and rating of products, consumer-consumer interaction, and spreading of electronic word-of-mouth (Batra & Keller, 2016). Moreover, specific technological decision aids, such as comparison engines, recommender systems, and social networks, assist consumers throughout their decision process and help reduce information overload, constituting crucial Internet tools (Kannan & Li, 2017).

Recently, the technical features of mobile devices have offered additional value to Internet access for consumers, which has profoundly impacted consumer purchase behavior (Park & Lee, 2017). By having wireless connection, ultra-portability, location sensitivity, and real-time interaction as key properties (Shankar & Balasubramanian, 2009), consumers can receive, search, share, and manage product, retailer, and competitor information on their mobile devices everywhere, even while evaluating products and services firsthand in-store (Rapp, Baker, Bachrach, Ogilvie, & Beitelspacher, 2015). In additional, mobile devices cover entertainment needs and are already considered an extension of the self (Shankar, Venkatesh, Hofacker, & Naik, 2010). An essential part of the mobile usage experience are mobile apps, specifically those related to social media, which lead the rank of downloaded apps (Fulgoni, 2015) and are an essential source of electronic word-of-mouth (Shankar et al., 2010). Thus, although privacy issues may arise (Verhoef et al., 2017), mobile services provide consumers several benefits during their purchase process, including utilitarian, emotional, and social values (Ström, Vendel, & Bredican, 2014). Although the effect of mobile device usage in current touchpoint and channel decisions is still an under-studied domain (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016), in the new

3

era of the Internet of Things, where connectivity with and between people, smart objects, and physical environments becomes central (Verhoef et al., 2017), it is undeniable that mobile devices have a crucial role in influencing consumer purchase decisions. With the introduction of more mediums, consumers’ channel choice patterns also tend to evolve, with consumers integrating touchpoints and channels in ways that allow seamless and interchangeable shopping experiences (Verhoef, Kannan, & Inman, 2015).

From the firm’s perspective, studies indicate that retailers providing new search, purchase, and contact channels for their customers entail considerable benefits. In addition to staying ahead of competition (Pozza, 2014), employing multiple channels increases customer satisfaction and loyalty (Wallace, Giese, & Johnson, 2004), and provides superior customer value (Kumar & Venkatesan, 2005). However, due to the increasing presence and use of online touchpoints and channels in today’s shopping environment, purchase decisions processes, and consequent consumer decision journeys, are believed to be more dynamic, complex, unstructured, and intrinsically different from those of traditional purchase behavior literature (Court, Elzinga, Mulder, & Vetvik, 2009; Edelman, 2010). Not only are there shifts in multichannel behaviors, but benefits and cost between channels that determine channel usage motivations are also believed to weight differently for consumers with the technological diffusion (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). Furthermore, consumers’ seamless and interchangeable use of channels, specifically in a mobile-mediated retail environment, is difficult or even impossible to control by retailers (Verhoef et al., 2015). More than ever, consumers can effortlessly switch and combine channels from different competitors in their decision process, leading to cross-channel free-riding (i.e., searching products through the channel of Firm A and purchasing through another channel of Firm B), which can erode profits and negatively influence consumer loyalty (Chou, Shen, Chiu, & Chou, 2016).

4

Since this technological and mobile revolution is a recent issue, as well as its influence on consumer behaviors, empirical knowledge regarding current consumer multichannel behavior is limited (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). The scarcity of studies focused on understanding the new consumer multimedia and multichannel behaviors in today’s mobile-mediated environment, and the need to develop better multichannel and consumer decision journey models, is explicitly recognized by the Marketing Science Institute (2014-2016; 2016-2018; 2018-2020), which has included, and is expected to continue to emphasis, these domains as important research priorities in current and nearby future Marketing investigation. Only by investigating and understanding today’s consumer decision journeys, and the motivations of specific multichannel behaviors, can we have an enhanced, extended, and profound theoretical and empirical knowledge regarding the multichannel consumer. This aids marketing and multichannel managers to develop effective multichannel customers management strategies that retain consumers throughout their decision process. According to Neslin et al. (2006), multichannel customer management is the “design, deployment, coordination, and evaluation of channels to enhance customer value through effective customer acquisition, retention, and development” (p. 96).

1.2. Research gaps

The development of the present study is driven by challenges and limitations in current multichannel literature that emerge from mobile device characteristics, which are believed to affect consumer multichannel behaviors. The study focuses on understanding consumer multichannel behavior in two domains, from which the exploration of the corresponding research gaps will follow.

5

Insufficient knowledge on how consumers integrate touchpoints and channels throughout current decision journeys

The consumer decision journey has been conceptualized as a process model in current literature (e.g., Batra & Keller, 2016; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016), built on consumer behavior process models from the 1960s and 1970s (e.g., Howard & Sheth, 1969; Lavidge & Steiner, 1961; Mintzberg, Raisinghani, & Théorêt, 1976). It is defined as the purchase process consumers go through that comprise both the stages of their decision-making process and the corresponding touchpoints at each stage (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). However, existing decision journey models either analyze the impact of multiple touchpoints on only one stage of the decision process (e.g., Baxendale, Macdonald, & Wilson, 2015), or, due to the availability of clickstream data, focus on online attribution modeling (e.g., Anderl, Becker, von Wangenheim, & Schumann, 2016; Anderl, Schumann, & Kunz, 2016) which neither considers uncontrolled touchpoints from firms nor does it distinguish between traditional online and mobile usage, to infer about consumer’s online decision-making processes. This provides both an incomplete view of the consumer decision journey and limited knowledge on how different channels individually influence the decision journey. According to McColl-Kennedy et al. (2015), for example, little is known regarding how consumer interactions with the firm’s contact points constitute a process, which is attributed to a lack of research considering and investigating the consumer decision journey in a holistic and dynamic manner. As such, extending the scope of consumer decision journey analysis, by mapping the entire decision journey, deserves more attention from researchers.

Moreover, research regarding recent consumer decision journey models has mainly suggested conceptual models (e.g., Batra & Keller, 2016; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016), offering little empirical evidence. When more than clickstream data exists for those

6

offering empirical evidence, it tends to be collected using internally-oriented methodologies, such as blueprinting (e.g., Bitner, Ostrom, & Morgan, 2008), that does not sufficiently focus on the consumer’s own view. Thus, empirically-oriented behavioral academic research, from the consumer’s perspective, is needed to understand the consumer decision journey (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). The present research pretends to address these limitations. As such:

− The research aims to fill these gaps in current multichannel literature and extend knowledge regarding consumer multichannel behavior by mapping the consumer decision journey in today’s mobile-mediated environment. This mapping will allow the (a) description of the whole decision journey, (b) from the consumer’s view, (c) using empirical data.

Lack of studies on motivations specific to particular consumer multichannel behaviors

Whether consumers use one or multiple channels throughout their decision process, the literature indicates that channel choice behavior is determined by various factors (e.g., channel experience, communication efforts, or sociodemographic characteristics (Ansari, Mela, & Neslin, 2008; Gensler, Verhoef, & Böhm, 2012)). Consumer motivations are one of the most important (Park & Lee, 2017) and thus the focus of the research.

Within a multiple channel context, channel choice behavior has many forms for multichannel consumers. In current literature, cross-channel behaviors are the most common, where consumers’ switch and combine different channels at different stages of the decision process (Flavián, Gurrea, & Orús, 2016). Of these behaviors, showrooming (i.e., search for product information offline and purchase online) (Rejón-Guardia & Luna-Nevarez, 2017) and webrooming (i.e., search for product information online and purchase offline) (Flavián et al., 2016) have been the most evidenced (Verhoef et al., 2015).

7

Recently, the popularity of showrooming has led some authors to develop a systematic understanding of the showrooming construct, which includes investigating specific underlying drives (e.g., Gensler, Neslin, & Verhoef, 2017). However, webrooming is the most widespread cross-channel behavior. For example, within the electronic product category (e.g., laptops/mobile phones/televisions), 44% of European consumers confirm the practice of webrooming against 9% of individual showroomers (Google Consumer Barometer, 2015). Also in Europe, sales in physical stores based on Internet information account for four times the amount of online sales, and are expected to continue to dominate by 2020 (Forrester, 2015).

Although it is the most important cross-channel behavior, webrooming lacks a theoretically structured treatment in multichannel literature. To the best of researcher’s knowledge, no study has focused on investigating the specific motivations that determine this particular behavior. With the exception of the studies of Gensler et al. (2017) and Rejón-Guardia and Luna-Nevarez (2017), that analyze motivational drivers specific to showrooming, previous motivational studies have mainly taken an exploratory focus, first identifying various multichannel behaviors and posteriorly characterizing them based on the same, generic set of channel usage motivations (e.g., Frasquet et al., 2015; Schröder & Zaharia, 2008). However, Flavián et al. (2016) recently argued that, since webrooming is a specific multichannel behavior, it is better understood recurring to more directed theories that may have a potentially higher explanatory influence. Additionally, Park and Lee (2017) noted that, although extremely important nowadays, “the mobile channel is not incorporated into the research” regarding multichannel motivations (p. 1400). Singh and Swait (2017) also draw attention to this research gap, and further indicate the need to differentiate motivational factors for the growing group of multidevice uses. As such, developing structured theoretical knowledge regarding what specifically motivates the

8

webrooming behavior and how it varies in today’s mobile-mediated environment has become increasingly important. The research intends to narrow these limitations. As such:

− The research aims to fill these gaps in current multichannel literature by building a systematic knowledge regarding the motivational factors that influence the most prevalent consumer multichannel behavior (i.e., webrooming). Based on directed theories, specific motivations that may influence webrooming will be proposed and empirically tested in a traditional, mobile, and multidevice context.

1.3. Research objectives

The current research aims to develop an enhanced understanding of consumer multichannel behaviors in today’s mobile-mediated retail environment. Although it starts with a consumer decision journey analysis, it subsequently focuses on the webrooming phenomena. As such, the research development focuses on two investigative levels:

− The consumer decision journey: consumer decision journey analysis detailly explores how consumers use and integrate touchpoints and channels during their decision-making process. The analysis, which takes a broader perspective, identifies and connects the usage of multiple touchpoints and channel at each stage of the decision process, and captures the complexity and dynamism in constructing consumer decision journeys. Since it involves multiple touchpoint and channel combinations, various types of multichannel, multimedia behaviors are observed. − The webrooming behavior: webrooming, on the other hand, is a specific

multichannel behavior identified within consumer decision journeys. Exploring the webrooming phenomena involves understanding antecedents of online search and offline purchase in the current mobile-mediated retail environment, namely the examination of webrooming-specific motivations.

9

Built on the research gaps identified in current multichannel literature, and classified in these two levels of analysis, the research objectives are the following:

1. Map the consumer decision journey in the multichannel, multimedia environment. This includes:

a. Describing consumer’s actual shopping experiences in terms of (1) touchpoint and channel contacts and interactions at each moment, and (2) tasks, activities, and stages they go through during their decision-making processes; and

b. Determining the existence of possible linkages between the tasks/stages of the decision process and the touchpoint interactions.

2. Determine the motivations leading to webrooming, namely:

a. Propose a structured webrooming-specific motivational model;

b. Examine how the specific proposed motivations explain different webrooming behaviors (i.e., traditional webrooming, extended webrooming with mobile channel usage, and multidevice webrooming).

Table 1.1 summarizes the link between research gaps, analysis level, and research objectives. The general objectives will guide the research design and analysis of findings.

Table 1.1

Research gaps and research objectives

Research Gap Level of Analysis Research Objective

Scarcity of knowledge on touchpoint and channel usage throughout current

consumer decision journeys

Consumer decision journey analysis

Mapping the consumer decision journey Scarcity of studies on

multichannel-specific motivations in the mobile

environment, particularly for webrooming

Webrooming behavior analysis

Proposing and examining motivations leading to various webrooming behaviors

10

1.4. Research design

To achieve the proposed objectives, the research plan and design recurs to various methods. Since the thesis aims to respond to two structurally different research objectives, with distinct research perspectives and paradigms, two methodologies are assumed, one for each objective. The research methods were selected based on their appropriateness to fulfill each research objective and allow a comprehensive vision of multichannel behaviors in the mobile-mediated retail environment.

As in previous studies on multichannel behavior (e.g., Frasquet et al., 2015), the thesis development considers two product categories. The choice of product category was based on the level of product involvement, one of the most recognized factors differentiating consumer decision and channel choice behaviors (Kotler & Armstrong, 2012). In line with the dimensions of product involvement (Zaichkowsky, 1985), electronic and grocery products have been chosen as high and low involvement product categories, respectively, similarly to previous research (e.g., Baxendale et al., 2015; Voorveld, Smit, Neijens, & Bronner, 2016). As high involvement products, the perceived risk associated with electronic products positively influences the extent of information search and the number of information sources compared to low involvement, grocery products (Kotler & Armstrong, 2012). However, recent mobile channel usage creates more opportunities to influence remote product evaluation (Rapp et al., 2015), which can have implications in multichannel behaviors for different product categories. As such, analyzing differences in current consumer decision journeys for the high and low involvement product categories is believed to be worth exploring. To analyze the webrooming behavior, however, only the high involvement category (i.e., electronic products) is considered, whose sector is highly dominated by webrooming behaviors (Google Consumer Barometer, 2015). Low involvement or routine purchase products

11

tend to involve single channel usage (Balasubramanian, Raghunathan, & Mahajan, 2005). Thus, the effects of dual, cross-channel employment, inherent to webrooming, is less observed for groceries.

The analysis of decision journeys is made through consumer decision journey mapping. With the aim of understanding the consumer’s actual, holistic, and dynamic decision journey, an exploratory qualitative research approach is adopted. Qualitative techniques are considered best suit to understand non-linear consumer experiences from their own perspective (Palmer, 2010). For each selected product within the respective product category (i.e., smartphone and soft drink), an adapted sequential incident technique was used to examine touchpoint and channel usage at each stage of the decision process. Based on the critical incident technique, sequential incident technique allows an in-depth and holistic understanding of incidents or events, while capturing the “dynamic, procedural nature of the customer experience” (Stein & Ramaseshan, 2016, p. 9). Sequential incident technique relies on a thorough analysis of recalled experiences from consumers (Stauss & Weinlich, 1997). However, diaries were added prior to personal semi-structured interviews to obtain detailed, real-time, and more reliable descriptions of the consumer’s own decision journey. Specific content analysis techniques were then used to analyze the data. The identification and description of touchpoints and corresponding activities, as well as touchpoint sequencing, was made recurring to sequence analysis. On the other hand, contingency analysis was applied to determine if possible linkages could be established between specific touchpoints and activities.

At the webrooming analysis level, which focuses only on the high involvement product category, the study builds on information-processing and uncertainty-reduction theories, suggested by Flavián et al. (2016), to propose and test specific motivations that may help explain webrooming: information attainment, price comparison orientation, and

12

empowerment, based on information-processing theory, and need for touch, risk aversion, and choice confidence, based on uncertainty-reduction theory. Quantitatively related methods are considered to examine these webrooming motivations. Due to limitations in symmetric theory (Woodside, 2013), two methodological approaches were introduced to achieve the research objective: discriminant analysis (DA) and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). While the DA is a regression-based approach (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1995), fsQCA allows complex configurational analyses that can assess causal asymmetry, equifinality, multifinality, and conjunctural causation (Ragin, 2008; Woodside, 2018). The complementary of statistical methods with fsQCA allowed the research objective to be achieved in a more comprehensive manner. Data were collected using a pre-tested questionnaire. The lack of some variable measurements in current literature led to the adaptation of measures for this specific work.

1.5. Main conclusions

The consumer decision journey analysis found that consumers engage with more brand-owned, retailer-owned, and third-party touchpoints during the smartphone purchase compared to the soft-drink purchase. Activities also tend to be in a higher number and more variable, especially during the pre-purchase and post-purchase stages. Although the sequence analysis identified four smartphone and four soft drink general sequence types, the smartphone decision journeys are inherently more complex, dynamic, and non-linear. The contingency analysis, on the other hand, which was based on the examination of touchpoint frequency, positivity, and importance, found that specific touchpoints and their respective channels are more appropriate for certain activities in the decision journey. The major variations exist among decision journey stages, with a same touchpoint being contacted at various moments in the decision journey for different purposes. The combination of the sequence and contingency analyses result in four

13

different decision journey maps for each product category. Word-of-mouth has particular importance and is transversal to all journey maps for the smartphone purchase. The retailer’s physical store is the channel most preferred by all types of soft drink purchasers. Regarding the examination of webrooming-specific motivations, the findings show that fsQCA allows a more nuanced and comprehensive view of the motivations leading to each webrooming behavior. The discriminant analysis indicates that information attainment determines all types of webrooming behaviors while price comparison and empowerment are related with behaviors that include mobile devices. FsQCA, on the other hand, indicates various motivational configurations for each behavior. Both information-processing motivations (information attainment, price comparison, and empowerment) and uncertainty-reduction motivations (perceived risk and need for confidence) are present in almost all configurations. In both methods, empowerment is important in the behaviors that include mobile devices. This is accentuated for multidevice webrooming with fsQCA.

1.6. Research contributions

This research offers new contributions to multichannel literature in two domains. First, is extends research on consumer decision journeys by empirically and holistically examining touchpoint consumption behavior throughout the decision process, from the consumer’s own perspective. Focusing on the analysis of firm-oriented data or subgroups of touchpoints and channels may lead to underestimations and erroneous conclusions regarding actual multichannel behaviors. By exploring the linkage between decision stages and touchpoints, which are elements that constitute consumer decision maps, an in-depth view of consumer multichannel behaviors is offered, especially necessary to develop new consumer decision journey models (Batra & Keller, 2016). The comparison

14

of high and low involvement decision journeys provides additional value to current decision journey research, as it accounts for the diversity in multichannel behaviors.

Second, the research is the first to develop a systematic theoretical understanding of the webrooming construct in terms of its motivational antecedents, which constitutes a major contribution to the literature regarding webrooming. It complements and advances the theoretical foundation of Flavián et al. (2016) by proposing and testing specific motivations that may explain webrooming in several settings, including mobile and multidevice usage. Examining mobile usage in multichannel behaviors remains an underexamined area in motivational multichannel literature (Park & Lee, 2017).

The research provides several methodological contributions beyond the theoretical and empirical advancements. The development of an adapted sequential incident technique which includes real-time consumer experiences, the use of new forms of assessing touchpoint appropriateness by combining touchpoint frequency, positivity, and importance, and the employment of a modeling technique based on sequence and contingency analysis to map the consumer decision journey are among the contributions made at a methodological level with the adopted decision journey analysis. The webrooming analysis, on the other hand, applies a dual methodological approach (i.e., DA and fsQCA), not yet employed in studies of multichannel behavior.

Managerially, the findings of the research supply substantial value for marketing and multichannel managers. In order to develop efficient multichannel strategies that avoid cross-channel free-riding, managers need to understand consumer behaviors in the multichannel environment, which includes comprehending “how consumers choose channels and what impact that choice has on their overall buying patterns” (Neslin et al., 2006, p. 97). The consumer decision journey maps provide frameworks that structure and assist how managers perceive touchpoints and channels throughout the consumer’s

15

decision process, which allows a more efficient targeting at the most crucial moments in consumer decision journeys. Since channel selection has inherently different drivers (Verhoef et al., 2007; Frasquet et al., 2015), exploring and understanding different webrooming motivations in the current mobile-mediated retail environment allows managers to more effectively tailor strategies that address webrooming-specific needs.

1.7. Research outcomes

The research has been presented at the 2nd CSG Research Forum in 2017 and at the 3rd CSG Research Forum in 2018. It has also been presented at the Global Innovation and Knowledge Conference (GIKA) in Valencia in 2018. A conference poster was also presented at the Lisbon Congress Center during the event “Science 2017 - Meeting with Science and Technology”.

The webrooming study was published in the Journal of Business Research:

Santos, S. & Gonçalves, H. M. (2019). Multichannel consumer behaviors in the mobile environment: Using fsQCA and discriminant analysis to understand webrooming motivations. Journal of Business Research, 101, 757-766.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.12.069

1.8. Summary of chapters

Apart from this first chapter (the introduction), the organization of the remaining thesis is as follows:

Chapter 2: In this chapter, a literature review of current knowledge in each research area is presented, including substantive theoretical and empirical findings. Fundamental concepts in consumer multichannel behavior are defined, and those related to channel selection, consumer decision-making processes, and motivational theory provide the research foundation. The research problems are contextualized against studies within the

16

key topics of the research. Limitations in current knowledge are discussed, as well as the need for the development of the present research.

Chapter 3: In this chapter, the conceptual framework for the research is presented. Two investigation models are developed based on the exploration of related literature in each of the two research objective areas. A dynamic consumer decision journey model is introduced, grounded on consumer process decision models and touchpoint and channel usage literature. To analyze the webrooming behavior, a backward-looking model is developed. The model proposes a set of motivations that have the potential do explain webrooming behaviors based on information-processing and uncertainty-reduction theories. The expected impact of each motivation on the various webrooming behaviors is discussed and propositions derived. The chapter terminates with the description of the context for the development of the study, namely of the product categories selected. Chapter 4: In this chapter, the theoretical paradigm underlying the thesis is discussed and the research design presented. Since there are two research objectives that are to certain extent independent, data collection instruments, methodological procedures, and analytical approaches for each research objective are detailly discussed.

Chapter 5: In this chapter, results are presented, explored, and discussed for the consumer decision journey analysis and webrooming behavior analysis. The consumer decision journey analysis starts with the description of touchpoints and corresponding activities for each product category, as well as the sequential analysis of touchpoints. Then, the results concerning touchpoint frequency, positivity, and importance are presented and serve as input to discuss the appropriateness of touchpoints for specific activities. Finally, data is combined to formulate decision journey maps for each product category. The webrooming behavior analysis, which is only done for the electronic product market, begins with presenting the findings of the discriminant analysis. The analytical process

17

of fsQCA is then described and the results examined. Data is finally compared and discussed to evaluate webrooming-specific motivations.

Chapter 6: This last chapter is the concluding chapter of the thesis. Here, a short conclusion of the research is provided where an overview of current multichannel behaviors is made. Theoretical, methodological, and managerial contributions are also discussed. Finally, limitations of the present research are examined and suggestions for future research proposed.

18

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Introduction

In this chapter, the research problems are put into perspective through the review of related literature and examination of current knowledge regarding multichannel consumers, their multichannel behaviors, and the multichannel context. The first section of the chapter starts by introducing fundamental concepts of consumer multichannel behavior, examining the evolution in multichannel studies and the perspectives assumed, and discussing general limitations in current literature. The research areas that constitute the basis of the thesis are then presented, namely research regarding the consumer decision journey and webrooming behavior.

The subsequent section examines the literature in the first research area: consumer decision journey. The elements that constitute the consumer decision journey are explored, which lead to a detailed discussion of process models in consumer behavior literature and touchpoint and channel preference behavior. The recent shift in consumer decision models and multichannel behaviors is emphasized, as well as limitations in current knowledge in these areas.

Literature in the second research area is then reviewed. The section starts by defining motivations and presenting major research findings in studies concerning channel choice motivations. Limitations in current literature are explored, and the focus on webrooming behaviors in today’s mobile-mediated environment is discussed, as well as possible explanatory theories.

Since consumer purchase decisions and multichannel behaviors are influenced by various factors, the second-last section presents and examines some of the most import factors. However, the focus of the study will be only on product category characteristics and involvement, and only for the consumer decision journey analysis.

19

The last section identifies gaps in current literature regarding the analysis of consumer decision journeys and webrooming behaviors and discusses the need for new investigative lines and approaches in the study of consumer multichannel behaviors.

2.2. Consumer multichannel behavior research

With the current proliferation and consequent impact of channels in consumer purchase behaviors (Neslin et al., 2014), the relevance of understanding multichannel consumers has become greater than ever. The present thesis is a study of consumer multichannel behavior. This first section starts by introducing the multichannel research discipline and defining the channel construct. Then, how consumer multichannel literature has evolved over time is examined and different perspectives on consumer multichannel behavior discussed. Based on the limitations in current literature and importance of studying this research area, the focus of the study is presented. Finally, the notion of omnichannel retailing is discussed to help understand the delimitation of the research.

2.2.1. The discipline of consumer multichannel behavior

Consumer multichannel behavior addresses the consumer behavior in the context of multiple information and distribution channels. It is the consumer’s use and combination of various channels to complete a purchase decision process, where this consumer is defined as the multichannel consumer (Frasquet et al., 2015). From the firm’s side, multichannel retailing is the “retail operation practice where a single retailer manages multiple retail channels” (Kim & Lee, 2014, p. 19).

The field of consumer multichannel behavior had its first developments in the 90’s and boomed with the appearance of the Internet, a channel that has deeply influenced purchase behaviors. It has emerged essentially from consumer behavior and service

20

management areas (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). As such, consumer multichannel behavior literature has borrowed theoretical constructs from scientific disciplines such as marketing, economics, operations, and behavioral science. The involvement of digital and technological usage in multichannel behaviors has made contributions steaming from information systems literature also important to its growth.

2.2.2. Channels and their roles

At the center of consumer multichannel behaviors are channels themselves. From a distribution perspective, Kotler and Armstrong (2012) define channels as “a set of interdependent organizations that help make a product or service available for use or consumption” (p. 365). At a more global level, Neslin et al. (2006) define the term “channel” as a “contact point, or a medium through which the firm and the customer interact” (p. 96). In service design literature, it is adopted in a similar manner. For example, Halvorsrud, Kvale, and Følstad (2016) define channels as “mediums used to convey communication and interaction between a customer and a service provider” (p. 846). For these authors, SMS, email, chat, call centers, and face-to-face interactions are customer channels. Shankar et al. (2016), on the other hand, conceptually distinguish between mediums and channels. According to the authors, a medium is a “means of communication such as app, email, and print”, and a channel is a “mode of transaction such as mobile, desktop, telephone, and physical store” (p. 38).

According to the definitions, channels may serve various purposes and thus have associated distinct roles. For example, according to Keller (2010), channels are important in persuading and incenting consumers. They allow consumers to learn about brands by providing a great deal of information, which evidences a strong communication or informational role. Also, channels allow firms to sell their products through a vast array of direct (i.e., personal contact and exchange between brands and consumers) and indirect

21

(i.e., exchange through third-party intermediaries) means (Kotler & Armstrong, 2012), demonstrating their relevant role as transaction platforms. After purchases, channels are also important, as they provide options for post-service activities, such as warranties and returning products (Frasquet et al., 2015). Based on Neslin et al. (2006) and the different roles channels may assume, channels are defined for this study from a consumer-centric perspective as mediums through which consumers can search and evaluate information, purchase, and develop post-purchase activities. Examples of channels include physical stores, personal computers/laptops (traditional online channel), and mobile devices.

2.2.3. Evolution in multichannel behavior studies

The studies in multichannel literature mainly consider consumer channel choice behavior. The first studies focused on the consumer’s choice for a specific channel, such as catalogues (e.g., Eastlick & Feinberg, 1999) and the traditional online channel (e.g., Teo, Lim, & Lai, 1999). With the widespread of e-commerce, a significant amount of studies have addressed the drivers underlying online channel usage, including perceived costs/benefits and Internet experience (e.g., Frambach, Roest, & Krishnan, 2007), functional and non-functional motivations (e.g., Parsons, 2002), social influence (e.g., Keen, Wetzels, de Ruyter, & Feinberg, 2004), frequency and amount of online shopping (e.g., Kaufman-Scarborough & Lindquist, 2002), product characteristics (e.g., Chiang & Dholakia, 2003), and demographics (e.g., Brashear, Kashyap, Musante, & Donthu, 2009). More recently, channel choice started to be analyzed for the mobile channel as well (e.g., Ko, Kim, & Lee, 2009).

The increasing awareness that consumer shopping activities are encompassed by a sequence of decisions that include the selection of various channels led many studies to start to take a more multichannel focus. These studies mainly consider consumer channel choice across the different stages of their decision process, identifying and characterizing

22

specific multichannel usage behavior patterns and multichannel segments (e.g., De Keyser, Schepers, & Konuş, 2015; Frasquet et al., 2015; Konuş, Verhoef, & Neslin, 2008). The mechanisms underlying channel choices have also received attention, with studies focusing on the effect of channel synergies, lack of channel lock-in, and attributes of search and purchase channels (e.g., Verhoef et al., 2007), as well as channel inertia over different decision-making stages (e.g., Gensler, Verhoef, et al., 2012). The effect of multichannel choices on consumer loyalty has lately gained interest (e.g., Larivière et al., 2011; Pantano & Viassone, 2015). More recently, a consumer experience focus has emerged in multichannel literature, where the emphasis is in exploring and understanding consumer touchpoint and channel consumption throughout the decision journey (e.g., Court et al., 2009; Rosenbaum, Otalora, & Ramírez, 2017).

2.2.3.1. Theoretical perspectives in multichannel behavior studies

Marsden and Littler (1998) have classified theories of consumer behavior in five general perspectives. Multichannel studies have mainly been based on three of them. The first is the cognitive perspective. Here, multichannel consumers are viewed as information-processing decision-makers that base their channel choice on utility and benefit/cost analysis derived from using a particular channel, whether it is at an economic, social, or symbolic level (e.g., Balasubramanian et al., 2005; Frambach et al., 2007; Gensler, Verhoef, et al., 2012). The second is the behavioral perspective. From this perspective, consumer multichannel behaviors are explained through stimulus-organism-response models, where external environmental influences (e.g., store atmosphere, website features, social norm, etc.) influence the consumer’s attitudes and internal state, which ultimately affects behavior (e.g., Keen et al., 2004; Verhoef et al., 2007; Zhang, Ren, Wang, & He, 2018). The third is the trait perspective. Here, the focus is on understanding differences in consumer multichannel usage patterns or segments based on

23

enduring personality characteristics, such as psychographic variables (e.g., De Keyser et al., 2015; Konuş et al., 2008; Sands, Ferraro, Campbell, & Pallant, 2016).

Although not widely applied in multichannel literature, the fourth perspective of Marsden and Littler (1998) has recently gained attention with the emphasis on consumer experiences. This is the interpretative perspective. This approach is concerned with understanding consumer experiences throughout the decision journey at the individual level, focusing on the meaning systems and subjective consciousness of consumers regarding their consumption behaviors (e.g., Spaid & Flint, 2014). The interpretative approach uses qualitative methodologies derived from, for example, phenomenological movements (e.g., Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982). As with the previous perspectives, the interpretative perspective considers consumers as somewhat rational agents since they are conscious individuals with a natural pre-given essence but construct their decision-making in accordance to the environment and context (Marsden & Littler, 1998).

2.2.4. Consumer experience and the consumer decision journey

Consumer experience is a multidimensional construct that focuses on the cognitive, behavioral, emotional, social, and sensorial response of the consumer to the offerings of a firm during all stages of the decision-making process (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). It is an internal and subjective response of consumers (Meyer & Schwager, 2007) that results from consumer interactions with products, firms, or part of firms (Gentile, Spiller, & Noci, 2007). Consumer-firm contacts can be direct or indirect (Meyer & Schwager, 2007) and may be within or without the firm’s control (Verhoef et al., 2009). Since consumer experiences are dynamic and complex, it has been considered relevant its analysis and conceptualization through consumer decision journeys (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016).

Studies addressing the analysis of consumer decision journeys have focused on how consumers interact with touchpoints and channels as they move from consideration,