I nve st iga t ing Chine se M igra nt s’ I nform a t ion-Se e k ing

Pa t t e rns in Ca na da : M e dia Se le c t ion

a nd La ngua ge Pre fe re nc e

Yuping Mao

California State University, Long Beach, United States

Abstract:

Keywords: Chinese Ethnic Media; Chinese Migrants; Information Diffusion; Information-Seeking Behaviours; Intercultural Sensitivity; Language Preference; Media Selection

Résumé:

Adoptant une approche quantitative, cet article recense les migrants chinois au Canada en ce qui concerne les chaînes de communication auxquels ils comptent afin de chercher des informations diverses. Cet article examine aussi la corrélation entre les préférences de chaînes de communication des migrants chinois avec leur niveau de sensibilité interculturelle. Les migrants chinois préfèrent les journaux et les sites Web chinois pour trouver de l’information administrative/politique et les informations de la vie plutôt que les journaux anglais et des sites Web. Cependant, ils utilisent les journaux et les sites Web anglais plus fréquemment pour la recherche d’emplois et le développement de carrière. Dans l’ensemble, la télévision anglaise et la radio sont plus fréquemment utilisés par les migrants chinois que la télévision et de radios chinoises. Les niveaux de sensibilité interculturelle des migrants chinois ont une corrélation positive avec leurs fréquences d’utilisation des ressources d’information en anglais, comprenant entre autres les sites Web du gouvernement, les journaux anglais, les sites Web non-gouvernementales anglais, les fonctionnaires, les réseaux sociaux non-chinois, la télévision anglaise et de la radio. Les résultats de cette recherche suggèrent que les médias ethniques chinois jouent un rôle important dans les comportements et les habitudes de recherche d’information des migrants chinois au Canada. D’une part, le gouvernement et d’autres organisations peuvent atteindre la communauté migrante chinoise à travers la diffusion de l’information dans les médias ethniques chinois. D’autre part, les migrants chinois devraient faire un effort actif pour améliorer leur maîtrise de l’anglais et la communication interculturelle sensible afin de mieux s’intégrer au sein de la société canadienne. Une approche plus équilibrée de la recherche d’informations à partir de sources de médias anglais et chinois pourrait être plus bénéfique pour les migrants chinois.

Introduction

In recent years, Canada’s population has become increasingly diverse with immigrants from different countries migrating to Canada to start their new life. In 1991, approximately 16.1% of Canada’s population was born in a foreign country, while in 2001, the proportion of the foreign-born population increased to 18.4% (Statistics Canada, 2005). According to the 2006 census, there were 1,216,565 Chinese people living in Canada, which made Chinese the largest visible-minority group from a single country in Canada (Statistics Canada, 2006). In 2011, Chinese was the top ethnic origin as reported by the first generation, and Chinese languages were the most common mother tongue used among immigrants whose mother tongue was not English or French (Statistics Canada, 2011). However, due to the great differences in language, culture, socio-economic background, and political ideology between China and Canada, many Chinese migrants have great difficulties in adapting to their new life in Canada. Employment and language facilities are the most frequently cited barriers for Chinese immigrants to integrate into Canadian society (Guo & DeVoretz, 2006), and both are related to migrants’ information-seeking behaviour.

Mass media have traditionally been a main source of information for the general public. However, social networks have become an alternative way for individuals to seek out information. Bishop and colleagues (1999) suggest that information providers should understand social networks among minority groups to design a more effective information system for minority communities. Furthermore, Courtright (2005) emphasizes that future research should examine in detail the usage of face-to-face, paper, telephone, and electronic sources for different types of information in a given population. This research answers the call for analyzing the roles of different resources in information-seeking of migration populations by surveying Chinese migrants in Canada on their use of different media and social networks.

Chinese diaspora’s lives are paradoxical, and they constantly navigate between their lives in the host country and “back home” (Ma, 2002). Therefore, Chinese migrants’ information-seeking behaviours in Canada are likely to involve both English and Chinese media, such as newspapers, television, radio, the Internet, as well as their personal networks in Chinese-speaking and English-Chinese-speaking communities. Taking a quantitative approach, this paper systematically examines how Chinese migrants in Canada seek government and policy information, job and career development information, and life information through different media and social networks in English and Chinese.

Aside from the bilingual characteristics, intercultural communication sensitivity could also be a very important factor influencing Chinese migrants’ information-seeking behaviour. Intercultural sensitivity is defined as the subjects’ “active desire to motivate themselves to understand, appreciate, and accept differences among cultures” (Chen & Starosta, 1998: 231). Individuals’ intercultural sensitivity level could influence their communication behaviour, the way they build and maintain interpersonal relationships, as well as the approaches they take to explore the culture and social structure of their host country. Therefore, this research takes into account Chinese migrants’ intercultural sensitivity level in exploring their information-seeking patterns.

social support to newcomers from other countries, in order for them to settle down and succeed in Canada, among which information diffusion has become an important but challenging task. In order to provide effective social support for Chinese immigrants, it is essential to understand their own ways of information-seeking. Thus, this paper aims to examine the patterns of Chinese migrants’ information-seeking behaviours, and how those patterns relate to their intercultural communication sensitivity levels and some other important demographic characteristics. The results demonstrated in this paper provide meaningful information for governments and NGOs to choose more effective ways to diffuse important and useful information to the Chinese community and provide suitable communication training for Chinese migrants to enhance their information-seeking skills.

Literature Review

Chinese Migrants in Canada

With the first group of Chinese immigrants arriving in Victoria in 1858, they were one of the oldest immigration groups in Canada (Li, 1998). Among the 755,698 Chinese immigrants who landed in Canada between 1980 and 2001, over 20% arrived in the 1980s, whereas approximately 70% arrived in the 1990s. There were more female landed immigrants (52.1%) than males (47.9%). The majority of Chinese immigrants (65.4%) were between the ages of 20 and 59; around one-quarter (25.6%) were under 21-years-old, and only 9% were 60 years and above.

According to Guo and DeVoretz (2006), Chinese immigrants in Canada come mainly from three areas: the mainland China (49.7%), Hong Kong (37.5%), and Taiwan (12.4%). Immigrants from these three areas have a different immigration history, and come from various social, cultural, and political backgrounds. There were three major immigration waves from Hong Kong to Canada after the 1950s (Wong, 1992). The first wave was between 1958 and 1961, due to dramatic changes in Hong Kong’s agriculture. The second wave was during the period of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1977) in mainland China. During this period, the political crisis threatened many people in Hong Kong and some decided to immigrate to Canada. The third wave began in the 1980s when Hong Kong was announced to be handed over to mainland China’s government. Many people departed Hong Kong for Canada because of their worries of the uncertain future of Hong Kong. A substantial number of mainland China residents immigrated to Canada in the 1990s as a result of China’s open-door policy, and the opening of a new Canadian immigration office in Beijing to process immigration applications directly from China (Guo & DeVoretz, 2006). Chinese immigrants from Taiwan migrated to Canada due to their concerns of political instability, and their immigration was understood “as a middle-class response to the problems resulting from the burgeoning export-oriented economy” (Tseng, 2001: 34). Although there is heterogeneity within the Chinese immigrant population, they all share the Chinese traditional cultural values and language. This paper includes participants from all the three regions.

Immigrants and Information-Seeking Behaviours

life and effectively using it. Chinese sojourners show lower English language fluency, lower ease of making friendships, lower subjective adaptation, and more adaptation and communication problems than non-Chinese Canadians and Chinese-Canadian students (Zheng & Berry, 1991). In general, minority groups show a negative pattern of information-seeking behaviours, as “outsiders are not usually sought for information and advice” (Chatman, 1996: 205). Based on data from low-skilled workers (Chatman, 1987), janitors (Chatman, 1990), and retired women (Chatman, 1992), Chatman concludes that the vulnerable populations do not actively seek useful information from their social networks and different mass media. This negative information-seeking pattern among migrants might also hold true for Chinese immigrants.

Research has been conducted to examine migrants’ health information-seeking behaviours. Chinese immigrant women in Canada identify linguistic difficulty as an important barrier to effectively seeking health information, thus health information is sought in Chinese through different channels, such as newspapers, television, Internet, workshops, health workers, and pamphlets. Furthermore, Chinese immigrant women prefer receiving health information from printed materials (Ahmad et al., 2004). Besides language difficulties that prevent Chinese immigrant women from clearly comprehending health information in English, time pressures and differences in the healthcare systems between China and Canada are identified as two other major barriers to getting health information effectively (Ibid).

The pervasiveness of mass media and the Internet have significantly improved the quantity and quality of the information that individuals can access. However, information disparity widely exists among various groups in the Canadian society. Tichenor, Donohoe, and Olien (1970) explain the relationship between mass media and information segments in society:

As the infusion of mass media information into a social system increases, segments of the population with higher socio-economic status tend to acquire the information at a faster rate than the lower status segments, so that the gap between those segments tends to increase rather than decrease.

(Tichenor, Donohoe & Olien, 1970: 159-160)

Chinese migrants, as a visible minority in Canada, more likely belong to the information-poor segments of Canadian society, due to their relatively lower socio-economic status.

Social networks, as a resource that many individuals frequently seek information from, play an important role in vulnerable populations’ lives (Liu, 1995; Metoyer-Duran, 1993). For instance, Hispanic farm workers use social networks to get information more frequently than any other type of information source (Fisher et al., 2004). Harris and Dewdney’s research explains individuals’ reliance on social networks for information, stating that individuals “frequently review their own experience first, then turn to people like themselves, including their friends and family” (1994: 24). It is important to further examine how the migration population uses different social networks to seek various types of information as “[w]hom the immigrants see, with whom they interact, and what organizations they join are aspects at least as the jobs they hold, the money they make, and the views they hold about the receiving society” (Portes & Bach, 1985: 299). Social networks are very important for immigrants to seek survival information, but it also has its limitations. Research shows that Latinos in the United States can usually get jobs through social networks, but those jobs tend to be low-paying (Green, Tigges & Diaz, 1999).

(2004) summarize several advantages of using informal social networks for support: (1) greater accessibility; (2) greater congruence with the shared norms of each group regarding needs expression and help seeking; (3) greater stability; (4) greater multiplicity, as one member of the network may provide different kinds of support; (5) greater equity; (6) greater adaptability to individuals’ needs; and (7) greater flexibility to provide support when it is required. They further argue that those advantages of using informal social networks are more relevant to immigrants and ethnic minorities who frequently encounter the following barriers: (1) language and cultural differences; (2) lack of accessibility to formal resources due to physical segregation; (3) lack of confidence; and (4) incompatibility with working hours. With language and cultural barriers in the Canadian society, it is reasonable to expect that Chinese immigrants are more likely to take advantage of the strengths of informal networks for information seeking.

Chinese migrants also face the general barriers that individuals have in gaining knowledge. Gaziano (1997) summarizes the following external barriers to gaining knowledge: family socialization patterns, community identity, social stratification, ethnic membership, and access to media. The external barriers are the barriers that Chinese migrants encounter at the collective level, and many of them are related to social and cultural differences. Therefore, intercultural communication sensitivity becomes an essential factor for Chinese migrants to effectively seek information and gain necessary knowledge in Canada.

Intercultural Communication Sensitivity

Intercultural communication sensitivity is an important ability for migrants to effectively integrate into the host country. Bhawuk and Brislin point out that a good intercultural communicator “must be interested in other cultures, be sensitive enough to notice cultural differences, and also be willing to modify their behaviour as an indication of respect for people of other cultures” (1992: 416). Intercultural sensitivity is defined as an individual’s “ability to develop a positive emotion towards understanding and appreciating cultural differences that promotes appropriate and effective behavior in intercultural communication” (Chen & Starosta, 1997: 5). Chen and Starosta (1996; 1998) differentiated intercultural sensitivity from intercultural communication competence and intercultural awareness. Intercultural communication competence includes “cognitive, affective, and behavioral ability of interactants in the process of intercultural communication” (Chen & Starosta, 2000). Intercultural awareness represents the cognitive aspect of intercultural communication competence and refers to the understanding of different cultures in which we live (Chen & Starosta, 1998). Intercultural sensitivity represents the affective aspect of intercultural communication competence, and refers to individuals’ “active desire to motivate themselves to understand, appreciate, and accept differences among cultures” (Chen & Starosta, 1998: 231). There are six constructs in the conceptualization of intercultural sensitivity: self-esteem, self-monitoring, open-mindedness, empathy, interaction involvement, and non-judgment (Chen & Starosta, 2000).

Based on the above literature review, this paper aims to extend the understanding of Chinese migrants’ information-seeking behaviours. The following two research questions are proposed to understand the channels that Chinese migrants use to serve their different information needs in Canada, and whether their information-seeking behaviours differ by demographic characteristics.

RQ 1: What are the main channels and methods that Chinese migrants use to seek government and policy information, job and career development information, and life information (e.g., shopping, housing, transportation, and entertainment) in Canada?

RQ 2: Do Chinese migrants’ information-seeking behavioural patterns differ by sex, age, and years of stay in Canada?

Moreover, this research examines how Chinese migrants’ intercultural sensitivity levels relate to their information-seeking behaviours, and the following two questions are proposed:

RQ 3: What is the relationship between Chinese migrants’ information-seeking behavioural pattern and their intercultural communication sensitivity?

RQ 4: Do Chinese migrants’ intercultural communication sensitivity levels differ by sex, age, and years of stay in Canada?

Method

Research Design

Participants

In total, 236 participants filled out the survey─127 online and 109 in written format. Most participants (n=181) filled out the survey in Chinese, and only 55 participants chose to fill the survey out in English. More females (n=131, 55.5%) participated in this study than males (n=97, 41.1%), and eight individuals did not provide gender information. The mean age of the 216 participants who provided information is 37.19 (SD=8.24); the youngest participant was 19-years-old and the oldest was 70-19-years-old. The age and gender distribution of the sample is representative of the landed immigrants in Canada (Li, 1998). Based on the years of stay in Canada provided by 221 participants, participants had stayed in Canada from less than one year to the maximum of 43 years, and the average was 7.17 years (SD=8.52). The majority of the participants were highly educated: 37.7% (n=89) with a Bachelor’s degree, and 36.4% with a Master’s degree or above. The majority of the participants were either permanent residents (n=81, 34.3%) or citizens (n=72, 30.5%) in Canada. Most of the participants could speak Mandarin (n=204, 86.44%), and very few could speak Cantonese (n=42, 17.80%).

Measurements

This research applied Chen and Starosta’s (2000) Intercultural Communication Sensitivity Scale (ISS) to measure Chinese individuals’ intercultural communication sensitivity. The researcher of this study developed scales to measure the frequency with which Chinese individuals seek the following three types of information: (1) government and policy information; (2) job and career development information; and (3) life information (e.g., shopping, housing, transportation, and entertainment). The frequency of using the following channels to seek the three types of information was measured through a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “Never” (0) to “Very Often” (5). The optional categories included: (1) Government websites, (2) English newspaper, (3) Chinese newspaper, (4) English non-government websites, (5) Chinese websites, (6) Chinese employees in NGOs, (7) non-Chinese employees in NGOs, (8) Government officers, (9) personal Chinese social networks (Chinese relatives, friends, workmates, members in the same interests group, etc.), (10) personal non-Chinese social networks (non-Chinese relatives, friends, workmates, members in the same interests group, etc.), (11) English TV and radio, and (12) Chinese TV and radio. Due to the nature of the information, the frequencies of getting information from the following three sources are also measured for job and career development: job fair, job agent, and professional association or union. Some important demographic information such as age, sex, and status in Canada were also collected at the beginning of the survey. There are a total of 74 items in the survey.

Intercultural Communication Sensitivity Scale (ISS)

The ISS (Chen & Starosta, 2000) contains 24 items and is a five-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (5). There are five factors contained in the ISS: Interaction Engagement, Respect for Cultural Differences, Interaction Confidence, Interaction Enjoyment, and Interaction Attentiveness.

10-item Impression Rewarding Scale (Wheeless & Duran, 1982), a 10-item Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965), a 13-item Self-monitoring Scale (Lennox & Wolfe, 1984), and a 14-item Perspective Taking Scale (Davis, 1996). In addition, the ISS has predictive validity, and it is predictive of intercultural effectiveness and attitude toward intercultural communications (Chen & Starosta, 2000). Peng (2006) applied the ISS to investigate the intercultural sensitivity of English major students, non-English major students, and multinational employees in China, and the overall Cronbach’s Alpha of all 24 items in the ISS was .80. The Cronbach’s Alpha for interaction engagement was .55, respect for cultural differences was .54, interaction confidence was .75, interaction enjoyment was .60, and interaction attentiveness was .48.

Data Analysis

The quantitative data from the survey questionnaires administered to Chinese migrants in Canada were subjected to statistical analysis using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Pearson product moment correlations, one-way ANOVA, and independent-samples t-test were conducted to answer Research Questions 3 and 4.

Results

After 236 participants completed the survey, the reliabilities of ISS, Government/policy Information Seeking Scale (GISS), Job/Career Development Information Seeking Scale (JISS), and Life Information Seeking Scale (LISS) were analyzed. The reliability of ISS, GISS, JISS, and LISS could not be improved by eliminating one or more questions. The GISS and LISS had the same 12 items using five-point Likert responses to indicate the frequency of using certain channels to seek information. The JISS had 15 items using five-point Likert responses. The Chronbach’s Alpha reliability estimate showed strong internal consistency for the ISS (α = .84), GISS (α = .78), JISS (α = .87), and LISS (α = .83).

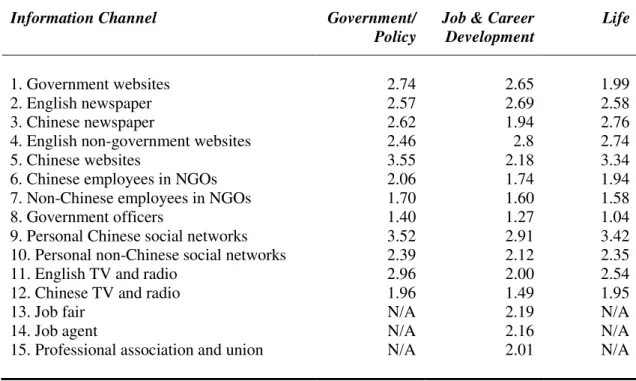

RQ 1: Information-Seeking Channels

The research results show that the top five channels Chinese migrants use to seek government/policy information are: Chinese websites, personal Chinese social networks, English TV and radio, government websites, and Chinese newspapers. For job and career development information, Chinese migrants seek information from the following channels most frequently: personal Chinese social networks, English non-government websites, English newspapers, government websites, and job fairs. The top five channels that Chinese migrants seek life information (e.g., shopping, housing, transportation, and entertainment) from are: personal Chinese social networks, Chinese websites, Chinese newspapers, English non-government websites, and English newspapers.

officers, although they have pertinent information for certain issues, are one of the least sought out sources from Chinese migrants for information. Table 1 below displays the frequencies of Chinese migrants’ use of different channels for various information channels.

Table 1: Means of Frequency of Using Different Information Channels

Information Channel Government/

Policy

Job & Career Development

Life

1. Government websites 2.74 2.65 1.99

2. English newspaper 2.57 2.69 2.58

3. Chinese newspaper 2.62 1.94 2.76

4. English non-government websites 2.46 2.8 2.74

5. Chinese websites 3.55 2.18 3.34

6. Chinese employees in NGOs 2.06 1.74 1.94

7. Non-Chinese employees in NGOs 1.70 1.60 1.58

8. Government officers 1.40 1.27 1.04

9. Personal Chinese social networks 3.52 2.91 3.42

10. Personal non-Chinese social networks 2.39 2.12 2.35

11. English TV and radio 2.96 2.00 2.54

12. Chinese TV and radio 1.96 1.49 1.95

13. Job fair N/A 2.19 N/A

14. Job agent N/A 2.16 N/A

15. Professional association and union N/A 2.01 N/A

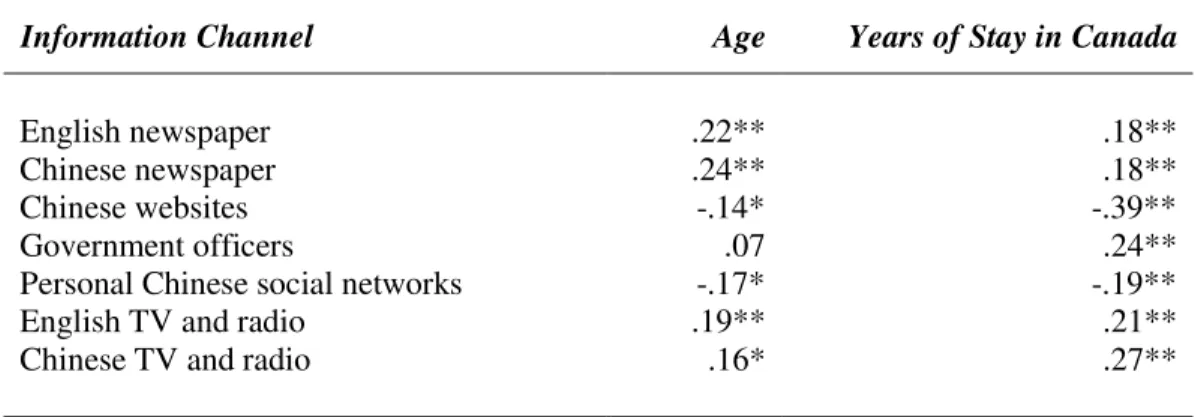

RQ 2: Information-Seeking and Some Demographics

Table 2: Correlation Coefficients of Chinese Migrants’

Age, Years of Stay in Canada, and Chinese Migrants’ Information Seeking

Information Channel Age Years of Stay in Canada

English newspaper .22** .18**

Chinese newspaper .24** .18**

Chinese websites -.14* -.39**

Government officers .07 .24**

Personal Chinese social networks -.17* -.19**

English TV and radio .19** .21**

Chinese TV and radio .16* .27**

* Correlation significant at .05 level (2-tailed). ** Correlation significant at .01 level (2-tailed).

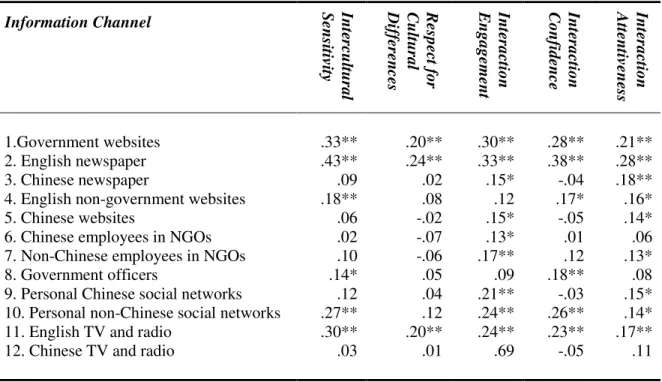

RQ 3: Information-Seeking and Intercultural Communication Sensitivity

Pearson product moment correlations were calculated to analyze the relationship between Chinese migrants’ intercultural sensitivity level and their use of different channels for information. As indicated by the correlation coefficients shown in Table 3 below, the intercultural sensitivity levels of Chinese migrants positively correlate with their frequencies of using English information resources including government websites, English newspapers, English non-government websites, government officers, personal non-Chinese social networks, and English TV and radio.

Table 3: Correlation Coefficients for Intercultural Sensitivity Variables and Chinese Migrants’ Information Seeking

Information Channel In te rcu ltu ra l S en sit iv it y R esp ec t f o r C u ltu ra l D if feren ces In te ra ctio n E n gage m en t In te ra ctio n C o nf id enc e In te ra ctio n A tten tiven ess

1.Government websites .33** .20** .30** .28** .21**

2. English newspaper .43** .24** .33** .38** .28**

3. Chinese newspaper .09 .02 .15* -.04 .18**

4. English non-government websites .18** .08 .12 .17* .16*

5. Chinese websites .06 -.02 .15* -.05 .14*

6. Chinese employees in NGOs .02 -.07 .13* .01 .06

7. Non-Chinese employees in NGOs .10 -.06 .17** .12 .13*

8. Government officers .14* .05 .09 .18** .08

9. Personal Chinese social networks .12 .04 .21** -.03 .15* 10. Personal non-Chinese social networks .27** .12 .24** .26** .14* 11. English TV and radio .30** .20** .24** .23** .17**

12. Chinese TV and radio .03 .01 .69 -.05 .11

* Correlation significant at .05 level (2-tailed). ** Correlation significant at .01 level (2-tailed).

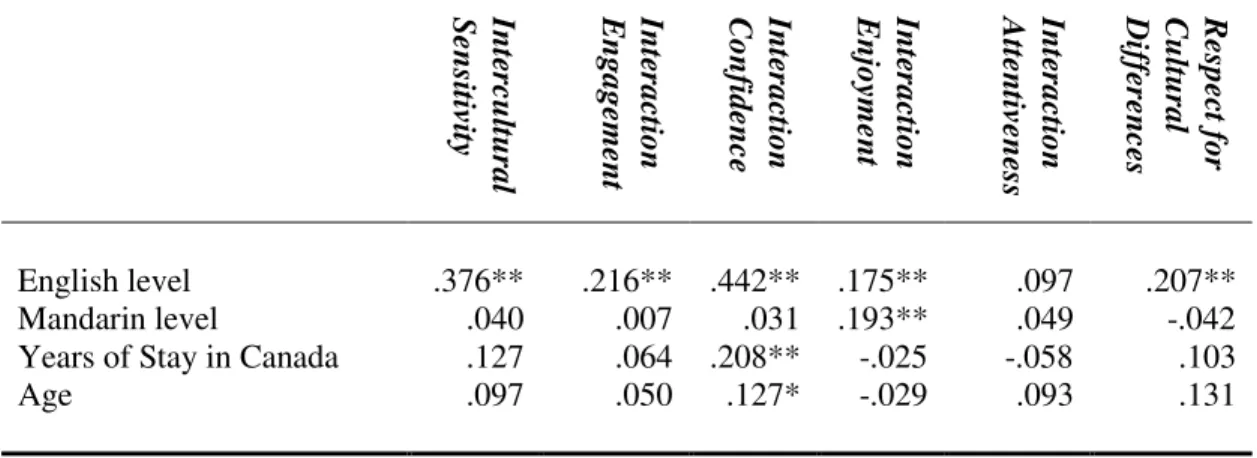

RQ 4: Intercultural Communication Sensitivity and Some Demographics

An independent-sample two-tailed t-test was performed to compare whether Chinese migrants’ intercultural communication sensitivity levels differ by sex. Although the female Chinese migrants’ sample size (N=131) is not equal to male Chinese migrants’ sample size (N=91), the Levene’s test for equality of variance indicates the significant level of .32 for the overall intercultural sensitivity scale, .12 for interaction engagement, .88 for interaction confidence, .22 for interaction enjoyment, and .06 for respect for cultural differences. All of the significance levels are larger than .05, therefore the equal variances are assumed. Overall, female and male migrants show similar levels of intercultural communication sensitivity. However, male Chinese migrants show a significantly higher level of interaction engagement (M= 26.89, SD= 2.72) than female Chinese migrants (M= 25.97, SD= 3.02): t=2.35, p < .05. Furthermore, one-way ANOVA test results showed that Chinese migrants’ intercultural communication sensitivity levels do not differ by their education levels and their status (i.e., permanent resident, citizen) in Canada.

of stay in Canada are positively correlated with their interaction confidence. Interestingly, Chinese migrants’ ability of communication in Mandarin has a significant positive correlation with intercultural interaction enjoyment.

Table 4: Correlation Coefficients for Intercultural Sensitivity Variables and Chinese Migrants’ Language Ability, Years of Stay in Canada and Age

In te rcu ltu ra l S en sit iv it y In te ra ctio n E n gage m en t In te ra ctio n C o nf id enc e In te ra ctio n E nj o ym ent In te ra ctio n A tten tiven ess R esp ec t f o r C u ltu ra l D if feren ces

English level .376** .216** .442** .175** .097 .207**

Mandarin level .040 .007 .031 .193** .049 -.042

Years of Stay in Canada .127 .064 .208** -.025 -.058 .103

Age .097 .050 .127* -.029 .093 .131

* Correlation significant at .05 level (2-tailed). ** Correlation significant at .01 level (2-tailed).

Discussion and Conclusion

The research results for question one on Chinese migrants’ use of various information channels indicate that Chinese migrants rely heavily on Chinese resources for Canadian government/policy information. It is surprising that Chinese websites and personal Chinese social networks are the top two resources that Chinese migrants seek for government information when they have lived in the Canadian society for an average of seven years. The significant role that Chinese personal social networks play in Chinese migrants’ information-seeking behaviours suggest the close connections among members of their Chinese community, which can be greatly helpful for new migrants to settle down in a new environment. However, the sole reliance on the Chinese community can create a certain degree of self-isolation as a minority group in Canada. For government and NGOs who want to diffuse important information, Chinese ethnic media such as websites and social media could be an effective outlet to reach this community.

play in the Chinese migrants’ life in Canada. NGOs and the government should continuously make efforts to improve Chinese migrants’ language proficiency, and also try to provide information and services in Chinese as transitional support. Interestingly, the results show that Chinese migrants use English newspapers and websites more frequently than Chinese ones for job and career development information. This might indicate that Chinese migrants are aware of the limitation of relying heavily on the Chinese language and community, and do make an effort to establish their career in dominantly English-speaking work environments.

Overall, Chinese migrants prefer Chinese media and networks than the mainstream English information channels in Canada. It is hard to draw a concrete conclusion of whether the Chinese media can really serve Chinese migrants’ needs in Canada without content analysis of the information provided. Zhou and Cai (2002) found that Chinese language media in the United States can connect immigrants to their host society, and the promotion of home ownership, entrepreneurship, and educational achievement provide important information for the first-generation immigrants to integrate into the American society. If Chinese media in Canada can also play such a positive role in Chinese immigrants’ life and adaptation into Canadian society, more collaboration between Chinese media and English media could strengthen this positive impact. To better reach Chinese migrant populations, the government and NGOs should try to disseminate important information in Chinese ethnic media and through Chinese social networks. Meanwhile, it is important that Chinese migrants realize their limitation of relying heavily on Chinese sources. To broaden the scope of information, Chinese migrants could benefit from a more balanced bilingual approach of searching information from both Chinese and English media and networks. Some training programs that introduce English information sources can be very helpful for Chinese migrants to better take advantage of information provided in English media channels.

In addition, Chinese migrants rarely seek information from government officers directly. Besides language barriers, Chinese migrants’ reluctance to interact with government officials might be influenced by their previous perceptions of government officials as powerful and inaccessible in China. The power distance in Chinese society is much larger than that in Canada (Hofstede, n.d.), whereas China scored 80 and Canada scored 39 in power distance. Research has shown recent Chinese immigrants tend to maintain close ties with their native land and are subject to the strong influences of Chinese culture as they attempt to adapt to Western cultures (Liu, 2005). Therefore, it is not surprising to find the communication behaviours of Chinese migrants in this study reflect some key characteristics of Chinese culture. In the acculturation process, Chinese migrants in Canada constantly balance and adjust their communication behaviours based on their changing perceptions of the host country and their remaining Chinese beliefs. Overall, some cultural and language training could be good strategies to increase Chinese immigrants’ frequency of searching information from English sources, such as government officials and websites in addition to Chinese sources.

Chinese identity and is a virtual space for Chinese immigrants to negotiate their identity in the host country. Findings in this study echo the findings of Yin’s research. After staying in Canada for a longer time, Chinese immigrants gradually start to rely less on their Chinese social networks, which might be a reflection of their changing social networks over a long time— having stronger social networks in Canada, but weaker social networks in China. After negotiating and reconstructing their identities over years, the “being Chinese” part might become less when the “being Canadian” part keeps growing. When providing information to Chinese migrants at different ages, it is important to take into account the age difference in their preferences of media.

Research question three investigated the relationship between Chinese migrants’ intercultural communication sensitivity and their information-seeking behaviour. The research results show that Chinese migrants with higher levels of intercultural communication sensitivity tend to seek information from English channels, such as English newspapers and websites, more frequently. Living in an English-speaking country like Canada, it is essential for Chinese migrants to use English sources frequently to get firsthand, accurate, and more updated Canadian information than the translated information in Chinese sources. Findings of this research indicate that incorporating intercultural communication sensitivity training in English training programs could be an effective way to increase Chinese migrants’ frequency of seeking information from English channels.

The research results of the fourth research question show that there is no gender difference in Chinese migrants’ intercultural communication sensitivity. Importantly, Chinese migrants with better English language skills show higher levels of intercultural communication sensitivity, tend to have more respect for cultural differences, are more confident and more engaged in interactions with people from other cultures, and enjoy intercultural interactions more than those with relatively lower levels of English proficiency. Therefore, English language level is an important indicator of Chinese migrants’ intercultural communication sensitivity.

However, there is no evidence that the longer Chinese migrants stay in Canada, the better their English skills are and the more culturally sensitive they are. This addresses the issue that many Chinese migrants do not improve their English much during their stay in Canada. This may be due to their lack of efforts to practice English, or limited access to English training programs provided by the government and other institutions. Findings of this study also show that Chinese migrants tend to rely on Chinese media for information, which also limits their opportunities of learning the English language in daily life. Therefore, it is important for Chinese migrants to make more active efforts to improve their English proficiency, get more information in English, and better adapt themselves into Canadian society.

Interestingly, although Chinese migrants’ age and years of stay in Canada do not relate to their intercultural communication sensitivity, older Chinese migrants and those who have stayed longer in Canada show more confidence in communicating with people from other cultures. As the length of stay in Canada is not correlated with English language ability, Chinese migrants may gain their intercultural communication confidence from communication skills other than language ability.

Edmonton, one of the major metropolitan areas in Canada. Chinese migrants’ behaviours and experiences in Edmonton may be different than Chinese migrants from other areas of Canada, especially those from rural areas and economically depressed areas. Future research should analyze the information-seeking behaviours and intercultural communication sensitivity of Chinese migrants from more diverse geographic locations. In addition, participants in this study are primarily recruited through Chinese social and media networks, so they might be more exposed to Chinese information sources. Future research could use a more systematic approach to recruit a random sample of Chinese migrants in Canada to validate findings of this study.

This research used a quantitative survey to investigate the information-seeking patterns of Chinese migrants in Canada, but does not provide in-depth information on why Chinese migrants have those information-seeking behaviours, the challenges for them to use certain information channels, nor the effectiveness of using those information channels. Qualitative research should be conducted to further analyze the above questions to provide new solutions for some of the challenges that Chinese migrants have in their information-seeking behaviours and patterns. Furthermore, future comparative content analysis of media information targeted at Chinese migrants in English and Chinese platforms can identify the information disparities between media sources. Results of the content analysis can provide important explanatory background information of Chinese migrants’ media preference.

References

Ahmad, Farah, Shik, Angela, Vanza, Reena, Cheung, Angela, George, Usha & Stewart, Donna E. (2004). Popular health promotion strategies among Chinese and East Indian immigrant women. Women & Health, 40(1), 21-40.

Bhawuk, Dharm P. S. & Brislin, Richard. (1992). The measurement of intercultural sensitivity using the concepts of individualism and collectivism. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 16(4), 413-436.

Bishop, Ann P., Shoemaker, Susan, Tidline, Tonyia J. & Salela, Pamela. (1999). Information exchange networks in low-income neighbourhoods: Implications for community networking. Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Information Science, 36, 443-449.

Cegala, Donald J. (1981). Interaction involvement: A cognitive dimension of communicative competence. Communication Education, 30(2), 109-121.

Chatman, Elfreda A. (1987). The information world of low-skilled workers. Library and Information Science Research, 9(4), 265-283.

Chatman, Elfreda A. (1990). Alienation theory: Application of a conceptual framework to a study of information among janitors. Reference Quarterly, 29(3), 355-368.

Chatman, Elfreda A. (1996). The impoverished life-world of outsiders. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 47(2), 193-206.

Chen, Guo-Ming & Starosta, William J. (1996). Intercultural communication competence: A synthesis. In Brant R. Burleson (Ed.), Communication yearbook, 19 (pp. 353-384). New York: Routledge.

Chen, Guo-Ming & Starosta, William J. (1997). A review of the concept of intercultural sensitivity. Human Communication, 1(16), 1-16.

Chen, Guo-Ming & Starosta, William J. (1998). Foundations of intercultural communication. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Chen, Guo-Ming & Starosta, William J. (2000). The development and validation of the intercultural communication sensitivity scale. Human Communication, 3(1), 1-15.

Courtright, Christina. (2005). Health information-seeking among Latino newcomers: An exploratory study. Information Research, 10(2). Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://InformationR.net/ir/10-2/paper224.html.

Davis, Mark H. (1996). Empathy: A social psychological approach. Boulder, CO: Westview. Fisher, Karen E., Marcoux, Elizabeth, Miller, Lupine S., Sánchez, Agueda & Cunningham, Eva

Ramirez. (2004). Information behaviour of migrant Hispanic farm workers and their families in the Pacific Northwest. Information Research, 10(1). Retrieved November 18, 2015, from http://informationr.net/ir/10-1/paper199.html.

Gaziano, Cecilie. (1997). Forecast 2000: Widening knowledge gaps. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 74(2), 237-264.

Government of Canada. (n.d.). Canadian multiculturalism: An inclusive citizenship. Retrieved November 18, 2015, from http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/multiculturalism/citizenship.asp.

Green, Gary P., Tigges, Leann M. & Diaz, Daniel. (1999). Racial and ethnic differences in job-search strategies in Atlanta, Boston, and Los Angeles. Social Science Quarterly, 80(2), 263-278.

Guo, Shibao & DeVoretz, Don J. (2006). The changing face of Chinese immigrants in Canada.

Journal of International Migration and Integration, 7(3), 275-300.

Harris, Roma M. & Dewdney, Patricia. (1994). Barriers to information: How formal help systems fail battered women. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Hernandez-Plaza, Sonia, Pozo, Carmen P. & Alonso-Morillejo, Enrique. (2004). The role of informal social support in needs assessment: Proposal and application of a model to assess immigrants’ needs in the South of Spain. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 14(4), 284-298.

Hofstede, Geert. (n.d.). What about China? Helsinki, Finland: The Hofstede Centre. Retrieved November 18, 2015, from http://geert-hofstede.com/china.html.

Lennox, Richard D. & Wolfe, Raymond N. (1984). Revision of the self-monitoring scale.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(6), 1349-1364.

Litwak, Eugene. (1985). Helping the elderly: The complementary roles of informal networks and formal systems. New York: Guildford Press.

Liu, Hong. (2005). New migrants and the revival of overseas Chinese nationalism. Journal of Contemporary China, 14(43), 291-316.

Liu, Mengxiong. (1995). Ethnicity and information seeking. Reference Library, 49(50), 123-134. Ma, Laurence J. C. (2002). Space, place and transnationalism in Chinese diaspora. In Laurence J.

C. Ma and Carolyn Cartier (Eds.), The Chinese diaspora: Space, place, mobility, and identity (pp. 1-49). New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Metoyer-Duran, Cheryl. (1993). The information and referral process in culturally diverse communities, Reference Quarterly, 32(3), 359-371.

Peng, Shi-Yong. (2006). A comparative perspective of intercultural sensitivity between college students and multinational employees in China. Multicultural Perspectives, 8(3), 38-45. Portes, Alejandro & Bach, Robert L. (1985). Latin journey: Cuban and Mexican immigrants in

the United States. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Rosenberg, Morris. (1965). Society and adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Shi, Yu. (2005). Identity construction of the Chinese diaspora, ethnic media use, community formation, and the possibility of social activism. Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, 19(1), 55-72.

Statistics Canada. (2005). Proportion of foreign-born population, by province and territory (1991 to 2001 censuses). Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/demo46a-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada. (2006). Visible minority population, by province and territory (2006 Census). Retrieved November 18, 2015, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/demo52a-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada. (2011). Immigration and ethnocultural diversity in Canada. Retrieved November 18, 2015, from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.cfm#a3.

Tichenor, Philip J., Donohoe, George A. & Olien, Clarice N. (1970). Mass media flow and differential growth in knowledge. Public Opinion Quarterly, 34(2), 159-170.

Tseng, Yen-Fen. (2001). New patterns of Taiwanese emigration: Capital-linked migration and its importance for economic development. In Christian Aspalter (Ed.), Understanding modern Taiwan: Essays in economics, politics and social policy (pp. 33-52). Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate.

Wheeless, Virginia E. & Duran, Robert L. (1982). Gender orientation as a correlate of communicative competence. Southern Speech Communication Journal, 48(1), 51-64. Wong, Siu-Lun. (1992). Emigration and stability in Hong Kong. China: University of Hong

Kong.

Zheng, Xue & Berry, John W. (1991). Psychological adaptation of Chinese sojourners in Canada. International Journal of Psychology, 26(4), 451-470.

Zhou, Min & Cai, Guoxuan. (2002). Chinese language media in the United States: Immigration and assimilation in American life. Qualitative Sociology, 25(3), 419-441.

About the Author

Yuping Mao is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Communication Studies at California State University, Long Beach, United States. Dr. Mao’s research focuses on intercultural, organizational, and health communication. Yuping has taught undergraduate and graduate courses on intercultural communication, research methods, health communication, media campaigns, culture, new media, and international business. Her work has appeared in several peer-reviewed journals and edited books, including: Journal of Intercultural Communication Research, Communication Research, Canadian Journal of Communication, China Media Research, International Journal of Health Planning and Management, and Journal of Substance Use.

Citing this paper:

Mao, Yuping. (2015). Investigating Chinese migrants’ information-seeking patterns in Canada: Media selection and language preference. Global Media Journal -- Canadian Edition,