BARBÁRA SOUZA FARHAT

SOVEREIGN WEALTH FUNDS:

A comparative analysis

BARBÁRA SOUZA FARHAT

SOVEREIGN WEALTH FUNDS:

A comparative analysis

Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getúlio Vargas, como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Administração Pública e Governo

Campo de conhecimento: Finanças Públicas

Orientador: Prof. Dr. George Avelino Filho

Farhat, Barbara Souza.

Sovereign wealth funds:A comparative analysis / Barbara Souza Farhat. – 2010.

98 f.

Orientador: George Avelino Filho

Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo.

1. Fundos de investimento – Economias emergentes. 2. Relações

econômicas internacionais. 3. Países emergentes – Condições econômicas. I. Avelino Filho, George. II. Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. III. Título.

BARBÁRA SOUZA FARHAT

SOVEREIGN WEALTH FUNDS:

A comparative analysis

Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getúlio Vargas, como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Administração Pública e Governo

Campo de conhecimento: Finanças Públicas

Data da aprovação: 31 / 03 / 2010 Banca Examinadora:

________________________________________ Prof. Dr. George Avelino Filho (orientador) FGV-EAESP

________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Fernando Luiz Abrucio FGV-EAESP

AGRADECIMENTOS

Quero primeiramente agradecer à FGV – EAESP não apenas pelo Mestrado em Administração Pública e Governo, como também pelas oportunidades de intercâmbio e realização do Programa CEMS, sendo esta a grande escola representante do Brasil nesta parceria.

Tenho a satisfação de ter tido minha primeira graduação concluída na própria FGV – EAESP em 2005, em Administração, agora complementando minha formação com o Mestrado.

Especialmente agradeço ao meu orientador e líder da linha de pesquisa Finanças Públicas, hoje Política e Economia do Setor Público, Prof. George Avelino. Ele é responsável pelo progresso que tive no entendimento da dissertação do mestrado e por desenvolver em mim o interesse pela pesquisa, tendo sido meu professor quando da primeira disciplina do Mestrado no início de 2008, Métodos de Pesquisa.

Agradeço aos professores convidados para a banca, Prof. Fernando Abrucio, coordenador do curso de mestrado e doutorado desta escola e também meu professor durante a graduação na FGV; e Prof. Pedro Dallari, meu professor em diversas disciplinas na USP e de quem tive o privilégio de receber orientação durante o trabalho de conclusão de curso da primeira turma de Relações Internacionais da USP em 2005, resultando na publicação de um livro sobre temas contemporâneos de Relações Internacionais.

Também devo registrar o orgulho que foi realizar este Mestrado em conjunto com o título de MSc in International Management do CEMS, cursado na Europa, em reconhecidas escolas como a London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) e a HEC Paris entre 2008 e 2009, experiências fundamentais para o aprofundamento deste estudo comparado. Agradeço então à Professora Ligia Maura Costa, pela coordenação do departamento CRI e pelas parcerias estratégicas da FGV com as escolas e empresas do CEMS.

Agradeço notadamente à empresa L’Oréal, patrocinadora do CEMS, e à Fundação Estudar pela bolsa de estudos com a qual fui contemplada durante meus estudos no exterior.

ABSTRACT

In a context of changes in the world economy, new investment vehicles emerge, molding the role of the State in international relations.

Political actors who once refrained from dabbling in investment activities have started gaining relevance in the world’s financial market.

The ambiguity surrounding the amount of resources and the investment intentions of certain developing countries’ sovereign wealth funds have caused disturbance among financial authorities of developed countries. Such concern with the capital influx and possible transference of power to peripheral economies has raised a wave of “soft nationalism”.

For a better understanding of the concept of Sovereign Wealth Funds, this paper focuses on their definition and main characteristics, since the topic is still media-based and controversial due to the novelty of the theme in academic research.

This study gathers comparative macroeconomic data from a small sample of countries whose governments hold well-established sovereign funds. This information is essential for the comprehension of what justifies the effectiveness of setting up such fund.

Finally the discussion will focus upon the configuration of the Sovereign Fund of Brazil, in light the qualitative analysis of different types of funds.

Key words: investment funds; sovereignty; national wealth; international relations;

RESUMO

Num contexto de mudanças no cenário econômico mundial, novas formas de investimento emergem, delineando o papel do Estado nas relações internacionais.

Atores políticos que não tinham histórico como investidores passam a ganhar relevância no mercado financeiro mundial.

A ambiguidade sobre o volume de recursos e intenções de investimento dos fundos da riqueza soberana de algumas nações, especialmente de países em desenvolvimento, tem causado desconforto junto às autoridades monetárias dos países ricos. Tal preocupação com o fluxo de capital e possível transferência de poder às economias antes periféricas suscitou uma onda de neonacionalismo.

Para se esclarecer o entendimento sobre Fundos Soberanos, este trabalho organiza sua definição e principais características, uma vez que esta discussão é ainda midiática e controversa, dada a novidade do tema no meio acadêmico de pesquisa.

Além disso, este estudo compara dados macroeconômicos de alguns poucos países, cujos governos detêm fundos já bem estabelecidos. Esta informação é essencial para a compreensão sobre o que justifica a efetividade na criação de um fundo deste tipo.

Enfim, quer-se, também, à luz da análise qualitativa de diferentes tipos de fundos, discutir a configuração do Fundo Soberano do Brasil.

Palavras-chave: fundos de investimento; soberania; riqueza nacional; relações internacionais;

TABLE of ABBREVIATIONS and ACRONYMS

AuM Assets under Management BoP Balance of Payments

BoP5 IMF Balance of Payments Manual 5

BPM6 IMF Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual6 BRICs Brazil, Russia, India and China

CalPERS California Public Employees Retirement System

CEPAL Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) CIC China Investment Corporation

CFIUS Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States COFER Currency Composition of Foreign Exchange Reserves FDI Foreign Direct Investment

FSB Fundo Soberano do Brasil

GAPP Generally Accepted Principles and Practices GDP Gross Domestic Product

GFSR Global Financial Stability Report

GIC Government of Singapore Investment Corporation GPF Norway’s Government Pension Fund

IMF International Monetary Fund

IWG International Working Group of Sovereign Wealth Funds KIA Kuwait Investment Authority

KIC Korea Investment Corporation

NBER National Bureau of Economic Research

OECD Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development SWF Sovereign Wealth Fund

SWFs Sovereign Wealth Funds SOEs State-owned enterprises UAE United Arab Emirates U.S. United States

WB World Bank

TABLE of CONTENTS

1 Introduction ... 7

1.1 Preface ... 7

1.2 Research Question ... 10

1.3 Objectives ... 11

1.4 Considerations on the methodology ... 11

2 Literature Review ... 13

2.1 Assessing the literature: the political issue ... 13

2.2 History of the SWFs ... 19

2.3 Definition of SWFs ... 22

2.3.1 Public Ownership... 27

2.3.2 Sources of Funding ... 30

2.3.3 Investment Purpose ... 33

2.4 Learning from the literature review ... 36

3 Current Situation ... 39

3.1 Transparency ... 39

3.2 The Existing Funds ... 44

3.3 Investment Profile ... 49

3.4 Operational Aspects ... 52

3.5 The Debate on Protectionism ... 55

4 Comparative Analysis ... 61

4.1 Remarks on Chosen Countries ... 61

4.2 Framework used for the analysis ... 65

4.2.1 Chile ... 70

4.2.2 China ... 73

4.2.3 Norway ... 75

4.2.4 Brazil ... 78

4.3 Summary of Analyzed Countries ... 81

5 Conclusion ... 83

References ... 84

Appendix 1 ... 91

LIST of GRAPHS

Graph 1: The historical growth of the SWF ... 21

Graph 2: Global Payment Imbalances ... 31

Graph 3: Commodities and Non-commodities funds ... 33

Graph 4: Commodity Boom (then recent bust) ... 35

Graph 5: Primary Source of Funds for SWFs (percent respondents) ... 44

Graph 6: SWFs in comparison with other assets ... 46

Graph 7: SWF and official foreign exchange reserves (USD Bio) ... 46

Graph 8: Relative Size of SWFs (USD tri) ... 47

Graph 9: SWF growth scenarios (USD tri) ... 48

Graph 10: Eligible Asset Classes (percent respondents who answered the question) ... 50

Graph 11: SWF acquisitions in the financial sector (USD bio) ... 51

Graph 12: Contents of Publicly Disclosed Information (percent respondents) ... 53

Graph 13: Legal Basis (percent respondents) ... 53

Graph 14: Determining investment objectives (percent respondents) ... 54

Graph 15: Restrictiveness on foreign investment ... 58

Graph 16 General Government Fiscal Balance of Brazil and Chile (percent of GDP) ... 62

Graph 17: Reserve Assets of Brazil and China (US$ billions) ... 62

Graph 18: World reserves of foreign exchange and gold (US$ billions)... 63

Graph 19: Macroeconomic indicators for the Norwegian petroleum sector ... 64

Graph 20: Fiscal Saving Rule (percent of the previous year’s GDP) ... 71

Graph 21: China foreign assets (USD billions) ... 74

LIST of TABLES

Table 1: Timeline for creation of some major SWF ... 22

Table 2: Similarities on definitions from different sources ... 25

Table 3: Summary of SWF’s single characteristics ... 27

Table 4: Sovereign Investment Vehicles Characteristics ... 29

Table 5: Recent SWF Market Size (by Quarter) ... 47

Table 6: SWF Significant Acquisitions in financial institutions ... 51

Table 7: Formal control mechanism for FDI in selected countries ... 57

Table 8: Restrictions to Foreign Direct Investment in Brazil ... 59

Table 9: Summary of the SWF of the studied cases ... 65

Table 10: Main indicators used for fiscal policy purposes... 69

Table 11: Economic variables analyzed ... 70

Table 12: Independent variables outcome ... 81

Table 13: Market Estimates of Assets under Management for SWFs ... 91

1

Introduction

This paper is a Master of Science dissertation in Public Administration and Government of the Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV), written during the CEMS MIM Program.

Sovereign Wealth Funds (SWFs) have gained significant notoriety in the past few years. Much has been published on a daily basis in regards to the definition of SWF (its size, growth rate and political implications). Although being a relatively old phenomenon, it was only in this current decade that the term has been coined and its volume of resources has become relevant.

Several new funds have been created in the past few years. The Brazilian SWF is one of them. Its conception has become a highly controversial topic. Many different structures have been cited as possibilities for the fund before its inception. This confusion about the cast of the fund from Brazil justifies the effort on identifying the possible patterns of SWF and comparing the emerging market with other sovereign funds holders.

There has been extensive academic debate about the topic but few articles have been published. Still both political and economical discussions concerning the SWF cannot be disregarded.

1.1

Preface

The dissertation is descriptive and uses investigative data. It is organized in five sections which are outlined in the preface. Besides introducing what the topic is about, the introductory section presents the question to be answered along with the text, as well as its objectives.

countries will also be undertaken. This includes a brief discussion of sovereignty to aid in the demystification of the controversial opinions regarding the SWF’s objectives. Moreover, section two also presents the history of SWFs during its over 50 year existence. This will help to explain the wave of creation of these funds and the reason why it has been underscored for the last three years. Certainly, it is essential to acknowledge the definition of what the SWF are. It helps to categorize existing funds into a typology and to explain the heterogeneity among them. Along with this there is a discussion regarding the macroeconomic variables from official national and multilateral sources to subsidize the composition of the comparative analysis. The research of these figures is crucial for the inferences about the countries, and the innovation of this dissertation is related to this review.

Section three is the most comprehensive one. It brings the panorama of the current situation of the funds. This section also goes into greater detail regarding information on the different sources that bring the current volume estimation of the funds. The main objective of this part is to present the general aspects of the current debate over SWF, including regulation and protectionism issues. The recent attempt to institutionalize the discussion about SWF is also present in this section, as it describes the effort from the IMF to discipline the actuation of the funds. Nonetheless, some aspects of the financial crisis and its relation to the SWF will not be ignored.

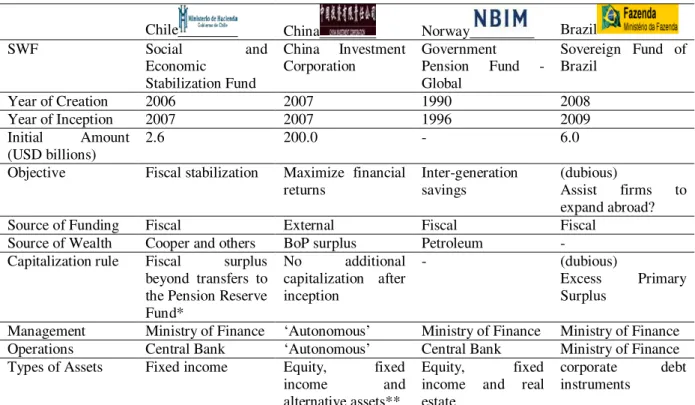

The main contribution of this dissertation is contained in section four, which is characterized by an investigative evaluation of countries that are currently holding SWFs. It comprises a comparative analysis of the funds from Chile, China and Norway, all three of which have deeply diverse economies that present well established sorts of wealth investment funds. The independent variables that make their funds flourishing are found in the macroeconomic exploratory research done for each country.

unfolding of a fund in an emerging market, the Brazilian case is a first-rate example. Brazil has gained territory in the international scenario as a BRIC1 country, a commodity exporter and for having presented sustainable fiscal improvements, despite economic constraints. Additionally, the country has currently discovered the potential for an increase in its exploitation of oil – an issue still to be matured by national authorities. Similar features were experienced by other emerging economies that have since created a sovereign investment fund. Therefore, this section is helpful in order to revive the conversation about the conditions for launching the Brazilian fund.

Chile was selected as one of the best cases of a South American country to hold an SWF with a relevant amount of resources. On top of that, the commodity exporter has a sound fiscal policy practice, one success measure to grasp. The parallels with Brazil are intuitive, since the past and recent histories of both countries are similar making Chile a realistic benchmark for its neighbors.

China, one of the most popular emerging economies today, represents the case of non-commodities funds that raised the issue of sovereignty menace to the developed world. Away from the commodity exporting profile, China has accumulated wealth for hosting a significant influx of foreign capital year over year. Such overall surplus on the Balance of Payments has been achieved by Brazil as well. Nowadays, it is unreasonable to disregard the Chinese economy as a global player.

Contrary to the previous example, Norway represents the most complete and transparent case, as being one of the few Western European countries that holds an SWF, proving that they are not only created by developing countries. The Norwegian example also provides support to wealth coming from the petroleum exploitation showing how nonrenewable commodities help enable wealth accumulation.

To conclude the study, section five summarizes the dissertation.

1 BRIC: acronym stands for four emerging markets: Brazil, Russia, India and China, coined in 2001 by Goldman

1.2

Research Question

The question that the present dissertation intends to answer is: Are there specific economic elements that favor the creation of an SWF?

To start the discussion on SWF, it is necessary to describe the funds and their context, especially because the concept of SWF is non consensual. This dissertation is relevant not only for the clear understanding of the funds, their typology and current institutional situation, but also for the accurate analysis of comparable cases. Setting up a comparative framework for the analysis allows increased insights regarding the environment under which the funds are created.

The pertinence of the topic can be illustrated by the phrase “SWFs sit at the intersection of high finance and high politics” (DREZNER, 2008, p.3). The reason for that is related to the fact the State-owned sovereign funds invest abroad, raising antagonist reactions. At the same time these investments are feared for the generally unclear political purposes the investor country has, they are welcome for financing diverse types of assets.

The emergence of such funds is claimed as the most striking financial development in recent years (COHEN, 2008, p.3). In addition, they are already sizeable, the latest volume estimation of these assets under management is roughly $ 3.8 trillion dollars (SWF Institute, October 2009) and there are mounting forms of investments (IMF, 2008a, p.6), meaning there are incoming funds to be created by some eligible countries as there is asset volume to accrue.

1.3

Objectives

The objectives of this dissertation are:

i. Clarify the literature about the SWF phenomenon. It is done by summarizing the main ideas brought by each applicable publication on SWF, especially regarding the designation of the funds, its origins and destinations;

ii. Evaluate parallels in the economic scenario of some countries that composed the sovereign funds through the gathering of internal capital (fiscal surplus) or those that did it through external accumulation (trade balance surplus and positive balances of international reserves). Those are independent variables that characterize ways for national wealth accumulation. The economic variables are taken into consideration for the classification of the fund into clusters. Besides that, the reasonable management of the fiscal policy is decisive for the authorities to evaluate whether the fund is feasible or not.

1.4

Considerations on the methodology

The reference for the methodology applied in this dissertation is the LSE Professor Hancké’s review of the book Designing Social Inquiry, by King, Keohane and Verba (1994), and the

latter volume itself.

The method to be deployed in this dissertation is comparative research, which, according to Hancké (2008), requires an active intervention by the researcher to select the cases in such a way that they allow for a conclusive answer of the question asked (HANCKÉ, 2008, p. 65).

The case studies are rather examples; after a broad explanation of what the funds are, three cases of countries with consolidated funds are chosen as benchmark to draw a parallel with the Brazilian newly created SWF. The inference of what are the exploratory variables necessary for the dependent variable to be explained is qualitative.

About the availability of data, SWF is somewhat a recent study topic. Books with an academic perspective on the topic are rare. On the other hand, secondary sources such as media and bank research publications are issued on a daily basis.

The public managers themselves hardly ever demonstrate the figures of the sovereign funds. The lack of transparency is indeed a common subject raised by the available literature. Therefore, there has been an effort from multilateral organizations to institutionalize the SWF actuation. This is the case of the IMF, fostered by the U.S. government, what resulted on the Santiago Principles or GAPP – Generally Accepted Principles and Practices. The GAPP can bring better data quality for the market to measure the SWF, as it consists on a group of country members that hold SWFs themselves drawing them into greater transparency regarding their financial transactions compelled to open room for transparency.

The IWG – International Working Group of Sovereign Wealth Funds – comprises 26 IMF member countries with SWF (IMF, 2008, p.1). Most of the existing literature considers that there are between 20 to 40 SWFs around the world, each of them with unequal particularities. In this sense, approaching the problem with a pure quantitative structure may not be confirmed as very efficient, especially considering the great amount of differences between the countries.

The result of a research with these characteristics mentioned above will not achieve an objective conclusion, but may well provide insights on the studied topic. On the subject of the nature of the variables, this dissertation is qualitative. The dependent variable of the proposed dissertation is the establishment of an SWF in a few countries. The independent variables are a collection of macroeconomic arguments of these countries related to the accumulation of wealth.

desired purpose. In fact, social science authors go even further: “Because the social world changes rapidly, analyses that help us understand those changes require that we describe them and seek to understand them contemporaneously, even when uncertainty about our conclusions is high” (KING, KEOHANE & VERBA, 1994, p. 6).

2

Literature Review

This section consists of excerpts from existing analysis designed to assist the non-specialist in gaining a better understanding of the topic. The starting point is done by posing the dichotomy concerning politics and economics raised through the acquisitions of the funds.

To better develop this point the definition of sovereignty needs to be assured. The debate regarding SWFs is primarily based on who holds the investment capital; more specifically, sovereign governments have the ownership of the funds, what is detailed on section 2.3.1.

Beyond this introduction, a deeper understanding of SWF can be gained through reviewing their history. All of which are important elements for gaining a better comprehension of the research, along with the development of the discussion on the existence of a favorable macroeconomic environment for the establishment of an SWF.

2.1

Assessing the literature: the political issue

The OECD members, the newly appointed recipient markets of the foreign investments, are the ones with more reliable and available findings on SWF actuation, supporting the reason why most of the chosen literature is from them. Still, the majority of the knowledge comes from secondary sources such as the media.

Furthermore, SWF interpretations are controversial. Whether SWF are political players or purely rational finance investors is a point of disagreement with scholars. To add value to this debate, this introduction presents the antagonist viewpoint as well.

First of all, the name of the fund says much about its nature. Being sovereign leads the reader to deduce the actuations of a government-owned vehicle and its implications on international relations (or cross-border investments) that are managed by a national authority. If the defense of strategic sectors of a national economy against foreign control is on the agenda, this awareness of the concept of sovereignty is crucial.

Paraphrasing Benjamin Cohen (2008) there is a “Great Tradeoff” between the interest in sustaining the openness of capital markets and the legitimate national security concerns of individual recipient countries. As the SWF regards a state financial investor, the funds effectively make of their home government the major player in world capital markets (COHEN, 2008, p.3).

Some authors claim these funds put the sovereignty of the developed world at stake, since the emerging economies, owning the majority of them, have proceeded with acquisitions throughout more affluent economies in strategic segments.

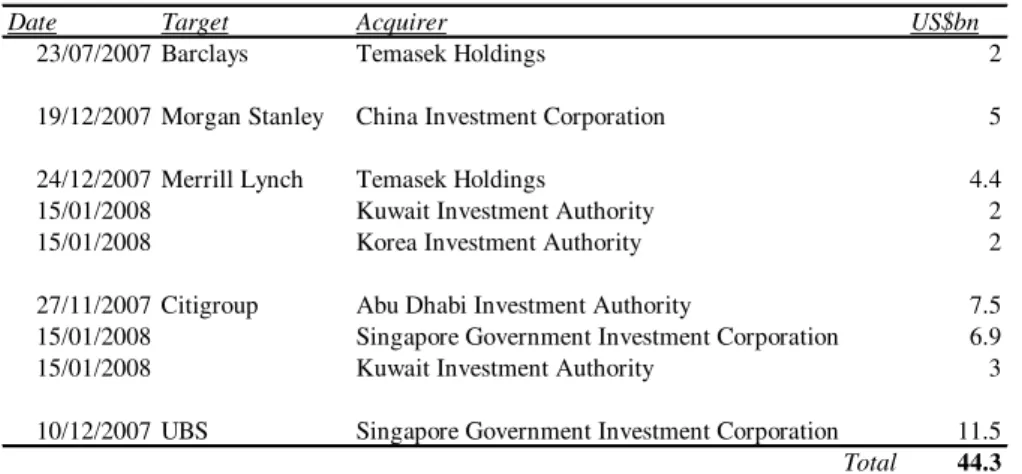

Exemplifying that, when the recently created fund China Investment Corporation (CIC) acquired ten percent of the shares of the North-American Bank Merrill Lynch in 20072, the realist interpretation would justify a wary response from the United States, as the Western country would fear that foreign control such as the presented one holds an underlying meaning of a sovereign intimidation from the Asian giant.

One of the most notorious cases, according to Cohen (2008) happened in 2005, again in the United States, when there was an unsuccessful attempt by the government-controlled China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) to purchase Unocal, a medium-sized U.S. oil producer. Another commented event was the frustrated bid from Dubai Ports World, state-owned company in the U.A.E., to purchase Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company (P&O), a British firm that controls U.S. ports facilities (ZIEMBA, 2007, p.5; GRIFFITH-JONES & OCAMPO, 2008, p. 30).

Lawrence Summers has noticed that the cross-border activities of SWFs, among others, have reversed the trend toward privatization (GILSON & MILHAUPT, 2008, p.3). “Public hostility to SWF investment could lead to a protectionist overreaction in the OECD economies” (DREZNER, 2008, p. 9). According to the IMF Work Agenda (2008), as related to foreign nationalization of private companies, “countries with SWFs are concerned about protectionist restrictions on their investments, which could hamper the international flow of capital” (p. 4).

In particular, 2007 publications – like Summers on “Funds that shake capitalist logic” – rely on this neorealist conception, that were realized through the creation of the Chinese government-directed investment vehicle, CIC, in that same year. The doubt on the essential purpose of investment of a fund from China may somehow have resulted on rumors of a new protectionist wave. Cohen (2008) agrees that, if unaddressed, the fears about security and sovereignty that the funds cause could provoke a growing wave of “financial protectionism” in host economies.

2 Table 6, “SWF capital injections in financial institutions” on section 3, is a summary of recent financial

Yet, in 2008, Edwin M. Truman, a senior fellow of the think tank Peterson Institute for International Economics, and frequently cited with reference to international financial institutions studies, especially about the IMF and SWF, defends the political side of the funds. In line with his responsive call (“Do Pick on Sovereign Wealth”, 2008b), he states “SWFs are political because they are owned and ultimately controlled by governments. It is naïve to think that they can or should be treated as apolitical.” He is categorically affirming that governments are political institutions, and as being so, may build and change alliances from time to time, depending on politics.

On the other hand, several authors have converse opinions. The interpretations of the spokespeople of the main developed countries are more SWF friendly than the radical opposite. Mainly demonstrated in their official declarations, not discouraging the investments is more valuable than incurring the risk of doing so by a protectionist covenant.

To illustrate this stream, the opinion of some proponents of the government in rich countries that have received the investments, the U.S. and the U.K., are particularly important. The British authorities represented by Sir John Gieve (2008), as Deputy Governor of the Bank of England – in his presentation to the Sovereign Wealth Management Conference3 – and Lord Peter Mandelson – at the OECD Conference (March, 2008) – rationally argue in their public speeches that the developed world welcomes those resources rather than feel threatened by emerging markets, especially in times of illiquidity. Their outlook is considerable because they represent what OECD countries think about the SWFs. Therefore, the market as a whole can have a better picture of the position of recipient countries.

Still on the European opinion, Stefan Schoenberg, former Bundesbank official, mentions the worries about the funds and recent measures: “German Chancellor Angela Merkel called such funds […] a ‘new element’ on international capital markets to which appropriate responses were needed” (SCHOENBERG, 2008, p. 57). However, having protectionism been brought back to the present arena, he fears the impetuous backlash against the financial liberalization.

On the North American side, Robert Kimmitt, Deputy Secretary of the U.S. Department of the Treasury (USTREAS), when advising the recipient countries about SWF, calms down the markets by saying SWFs do no harm. “SWFs have not caused significant financial-market disruption and that the overwhelming majority of SWF investments do not involve partial or complete control of firms” (KIMMITT, 2008).

Nonetheless, the United States are intransigent on defending that bigger disclosure of these instruments is mandatory. Clay Lowery, Acting Undersecretary of the U.S. Treasury for International Affairs (June, 2007), publicly “called for the IMF and World Bank to draft best practices to address these issues” (DREZNER, 2008, p. 11).

Along with the Western European apprehension, the opinions presented above do not mean that the U.S. and the U.K. are welcoming the funds regardless of further motivational reasons. In fact, the U.S. seems to be inherently motivated to settle a regulatory agenda. They seem to be open for foreign investments, as long as they know the intentions of the incumbent capital.

Bringing the discussion to other authors apart from government representatives, more moderate researchers advise not to exaggerate on fear and consequently follow into a protectionist reaction. “Such investments have a vital role in providing liquidity to global markets and in generating wealth both for their home countries and receiving markets” (EIZENSTAT & LARSON, 2007, at A19).

Several papers examined in this dissertation make allusion to the Research Analysis of the Deutsche Bank, International Topics – Current Issues, by Steffen Kern (2007), and its update in 2008. It is comprised of a thorough study of causes and consequences of the emergence of the SWF. Referring to the political aspect of the funds, he brings an explanation on countries restrictions on FDI, as the concerns are legitimate, albeit a bit exaggerated. According to Kern, despite no significant case has been reported so far “it is theoretically conceivable that a state uses its SWF as a vehicle to buy into a strategically important company – e.g. in the arms, high-tech or infrastructure industries – and thereby acquires the ability to influence corporate strategies and operations, or control over that company’s assets and know-how” (KERN, 2007, p.14).

sentiment that is carried out when considering the foreign capital influx that is not regulated is suspiciousness. In the context of anarchism of the International Relations, there is no coercion if any player trespasses the jurisprudence that was established.

The bibliography on actions towards regulation is extensive. It is worth mentioning Edwin M. Truman, who finds the funds are “the latest topic de jour in international finance” (2007). In

this first assignment he tackles the lack of transparency of the funds and benefits of accountability. At his forthcoming publication, of April 2008, to be explored in section 3, his concern about disclosure becomes a proposal of a score board to classify the funds, in an attempt to diminish the lack of information.

Apart from Truman’s “Blueprint for SWF best practices”, there have been several efforts to concentrate the information and provide a sort of standardization to the queries raised due to the growth and already remarkable volume of the funds. In 2008, the SWF Institute website was launched on the Internet, bringing a collection of data on funds and a transparency index elaborated by its administrators.

The Group of Seven (2007) called on the IMF and OECD to engage in the issue. “The process would operate on two parallel tracks. The IMF would develop principles to guide the behavior of SWFs. The OECD would focus on the recipient side” (COHEN, 2008, p.10).

The practical outcome was the fact that the IMF sponsored the International Working Group (IWG), aiming to turn the discussion group into a standing one. The creation of the IWG Generally Accepted Principles and Practices (GAPP), the Santiago Principles (2008) has been mentioned in nearly all the documents that show concern on the political influence of the funds. As this reference is central for the development of the topic, it is explained in this early part.

Representatives of SWFs had a summit at IMF headquarters in Washington, D.C. The IWG4

4 IWG member countries are: Australia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Botswana, Canada, Chile, China, Equatorial

Guinea, Iran, Ireland, South Korea, Kuwait, Libya, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Qatar, Russia, Singapore, Timor-Leste, Trinidad & Tobago, the United Arab Emirates, the United States, and Vietnam. Saudi Arabia, the OECD, and the World Bank will participate as permanent observers (IMF GAPP, 2008).

before, are dubbed the Santiago Principles5. The IWG definition and principles will become a basic reference for the classification of the SWF, as being accepted as the institutionalization of the issue.

This IMF effort to institutionalize the conversation on SWF has created periodical documents about the funds actuation, as this dissertation will show through the Work Agenda (2008a), the Santiago Principles (2008b) and the Kuwait Declaration (2009), to mention a few.

This regulatory initiative is incentivized by the ones who pointed out concern on lack of transparency of the SWF. On February 24th 2009, the SWF Forum took place in London, with

prominent thinkers of SWFs. According to Edwin M. Truman’s presentation “Beyond the Santiago Principles” (2009), the establishment of a permanent group of the IWG participants is essential and they should continue to interact with recipient countries to help ameliorate their concerns.

On the same day, during the Forum, Udaibir S. Das, Chief of the Sovereign Asset and Liability Management Division, Monetary and Capital Markets Department, IMF, presented the results and perspectives of research developed by his team. This research counted with 20 respondent countries. This is one more meaningful source of information as it was raised from the investing countries. Their discoveries are presented in section 3.

Thus, the transparency question that has been exposed through the discussed literature is brought to this dissertation in greater detail through the next section.

2.2

History of the SWFs

Following on the understanding of the issues raised by the SWF, its brief history is presented here. It clarifies one more dubious aspect of the SWF.

Several authors start by saying that SWFs are not new. That is because the funds have existed since the 1950s, but it was only in 2005 that the SWF term was first coined, by Andrew Rozanov6

.

In the words of the Managing Director of the Morgan Stanley Research, SWFs were formerly established three or so decades ago as oil price (or commodity price) stabilization funds to help block out turmoil from volatile oil prices on the budget, monetary policy and economy of oil exporting countries (JEN, 2007, p. 3).

According to the Deutsche Bank Research (KERN, 2007, p.4), the first so-called SWF was the Kuwait Investment Board. Set up in 1953, eight years before Kuwait’s independence from the United Kingdom, its aim was to invest surplus oil revenues to reduce the country’s reliance on its finite resources. This governmental institution was replaced in 1965 by the Kuwait Investment Office (KIO)7, a subsidiary of today’s SWF Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA).

The Pacific island State Republic of Kiribati had the second established SWF, in 1956, 23 years before the British colonial independence. The so-called Gilbert Islands, in order to hold royalties from Phosphate mining, settled the Revenue Equalization Reserve Fund (RERF). Its assets under management (AuM) correspond today to nine times Kiribati’s GDP and returning investment income of around 33 percent of GDP (KERN, 2007, p.4).

After this early establishment of fund from these two small countries, the number of SWFs has soared. The reasons for that are as much related to the rising commodities price as they are to international reserves accumulation, the independent variables used to build the argument on the propitious ambience for the creation of these funds. A graph on the rise of the SWF is illustrated as follows.

6 Rozanov, Andrew. “Who Holds the Wealth of Nations?” Central Banking Journal 15, November/2005. He is

head of Sovereign Advisory and managing director at State Street Global Markets. For him, SWF are neither traditional public pension funds nor reserve assets supporting currencies, but a different type of entity altogether (ROZANOV, 2005, p. 52).

7 The Kuwait Investment Office was established by Sheikh Abdullah Al-Salem Al-Sabah on 23rd February 1953

Graph 1: The historical growth of the SWF

Sources: GIEVE, 2008; BIS Review 31, p.7.

Despite the gradual characteristic of the rise of the SWFs and after this first step on the creation of the SWFs from the 1950s, two other waves in the creation in these funds can be identified8.

i. The longest one started in the 1970s, resulting from a spike in energy prices and the advent of the Asian tiger economies. Large funds were established in these decades in Abu Dhabi (the first of several in the U.A.E.), Norway (to be analyzed in case studies), and Singapore (Temasek Holdings [1974] and Government Investment Corporation [GIC, 1981]) (MONITOR, 2008). As a result on the excess of revenues, some oil exporters increased spending to match higher incomes and faced a painful adjustment when prices fell back again (GIEVE, 2008, p.2). In order to cushion that, these countries found out the ingenious SWF structure.

By the end of this wave, in the 1990s, smaller funds were created in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, caused by manufacture exportation excess revenues, as table 1 below shows.

ii. The current wave, of the beginning in 2000, has led to the formation of nearly 20 funds, most of which are funded by capital inflows based either on high energy prices (especially in the Middle East but also in Russia) or continued substantial capital inflows or balance of payments (BoP) surpluses (e.g., in China). There has been a marked increase in the number of SWFs, with China and Russia joining the fray to form what has been dubbed the “Super

8 The definition of dates does not follow any strict parameter. This division into waves is merely for a matter of

Seven9” biggest funds (NORTON ROSE LLP, 2008a). Thus the most recent group includes not only funds originating in small, wealthy nations but also in major geopolitical powers (MONITOR, 2008).

In line with Monitor Group report (2008), similar reasons have motivated the creation of funds in different decades, and with multiple configurations.

Today, the SWF industry comprises more than 40 institutions. This includes a number of vast volume funds with assets under management in excess of 100 billion dollars each (KERN, 2007, p. 4). The biggest concentrations of SWFs by dollar volume are in the Middle East and East Asia. Many of the newer funds are inspired by the examples of KIA, ADIA, Temasek, and GIC and resemble university endowments in their investment behavior (MONITOR, 2008, p. 16-18).

As other sovereign governments have announced, there are more SWF to follow suit in the years to come.

The timeline below shows the creation of some SWF for the last half century:

Table 1: Timeline for creation of some major SWF

Year 1953 1967/90 1974/81 1976 1998 2006 2007 2007

SWF Kuwait Norway Singapore Abu Dhabi Venezuela Chile Russia China

Source: Adapted from Monitor and IWG IMF, 2008.

2.3

Definition of SWFs

This subsection aims to clarify precisely, through knowledgeable literature, what an SWF is. Such a definition is a challenging task mainly because a common consensus is lacking. However, there are three main aspects that are agreed upon that are common to the SWF:

9 This group consists of the two new entrants along with Abu Dhabi, Norway, Kuwait and Singapore’s two

ownership, the source of funding and the purpose of investment. All of which will be explained, as well as the choice for one specific source for the official definition.

The lack of consensus about the SWF definition can be exemplified by the following piece of news of June 2008:

The Treasury Secretary of the U.S. Henry Paulson told the Prime Minister in Moscow Vladimir Putin that he had had a productive discussion with Russian Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin about the Russian SWF10. Putin responded by saying: “Since we do not have a sovereign wealth fund yet, you are confusing us with someone else.” To which Paulson replied, “we can discuss what you have called the various funds but we very much welcome your investment” (REUTERS, 2008).

In fact, as stated by Monk (2009, p.7), both opinions are justifiable. Depending on the definition attributed to the SWF, that have been pretty much elusive, some funds are excluded from this categorization.

Actually, as reported by the U.S. Treasury Department (2007, p.1) there is no single universally adopted definition for the SWF.

Yet, it is hard to differentiate between “proper” SWFs and other forms of public funds. For instance, the reason why Norway’s Government Pension Fund and Australia’s Future Fund are usually classified as SWFs, while the Stichting Pension Fund (ABP) in the Netherlands and the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) are viewed as conventional pension funds is controversial (FERNANDEZ & ESCHWEILER, 2008, p.4). For the latter specific qualification, see Ashby H. B. Monk, 2008.

A simplistic notional definition would be “SWFs are large pools of capital controlled by a government and invested in private markets abroad” (KIMMITT, 2008, p.2).

10 “As of Feb 2008, the Oil Stabilisation (sic) Fund will be split into two funds, one section managing official

The IMF Work Agenda, on page 37, brings several definitions of SWFs from different sources, selected below:

1. U.S. Treasury (June 2007) “SWF means a government investment vehicle which is funded by foreign exchange assets, and which manages those assets separately from the official reserves of the monetary authorities11”. The conditions for the SWF assets not to be classified as official reserves12 depends on whether they are invested in less liquid instruments and/or the monetary authorities may not have a clear legal right to meet a balance of payments need with them (USTreas, 2007, p.2).

This aspect of being managed apart from the central bank is common in other definitions, such as the one found in the paper by Roland Beck and Michael Fidora, 2008. On the one hand, the U.S. Department of the Treasury definition is meant to differentiate SWFs, funded from the start by net foreign assets (through commodity exports or exchange rate intervention) from, for example, ordinary domestic pension funds which are initially funded in domestic currency but which may then diversify internationally (USTreas, 2007, p.1). On the other hand, limiting the SWF definition (as the U.S. Treasury does) to those funds that receive their capital from foreign exchange reserves would eliminate well-established funds, such as Singapore’s Temasek, that early in its inception had basically direct stakes in local industries, and only recently diversified to other countries (NUGÉE, 2008, in MONK, 2009, p.8).

2. Deutsche Bank, by Steffen Kern (September 2007): “SWFs – or state investment funds – are financial vehicles owned by states which hold, manage, or administer public funds and invest them in a wider range of assets of various kinds. Their funds are mainly derived from excess liquidity in the public sector stemming from government fiscal surpluses or from official reserves at central banks.” Steffen Kern also adds “SWFs essentially differ from the other types of funds as they are not privately owned, raising important questions in terms of financial market policy and corporate governance” (KERN, 2007, p.2). In October, 2008, the same author had launched an update to the SWF discussion, adopting the IMF definition and

11 According to the U.S. Treasury, “this definition is meant to differentiate SWFs […] from, for example,

ordinary domestic pension funds which are initially funded in domestic currency but which may then diversify internationally.” However, in the same document the U.S. Treasury admits the two types of funds do share common characteristics and may not be distinguished.

differentiating SWFs functions as complementary to other state-operated entities (KERN, 2008, p.2).

3. McKinsey Global Institute (October 2007): “SWFs are usually funded by the nation’s central bank reserves and have the objective of maximizing financial returns within certain risk boundaries.” McKinsey contrasts these funds with government holding corporations such as Temasek (Singapore) and Khazanah (Malaysia).

4. Morgan Stanley, by Stephen Jen (October 2007): “An SWF needs to have five ingredients: sovereign (sic); high foreign currency exposure; no explicit liabilities; high-risk tolerance; and long-term investment horizon.”

5. OECD’s (November 2007) definition is similar to the one from Robert Kimmitt (2008): “Government-owned investment vehicles that are funded by foreign exchange assets.”

6. Edwin M. Truman – before the U.S. House Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs (November 2007) defines SWFs as: “Separate pools of international assets owned and managed by governments to achieve a variety of economic and financial objectives. They sometimes hold domestic assets as well.” According to later studies on the portfolio management of the funds, they may indeed invest domestically; however, “most sovereign wealth funds appear to have substantial exposure to foreign investments or are even entirely invested in foreign assets” (BECK and FIDORA, 2008, p.6).

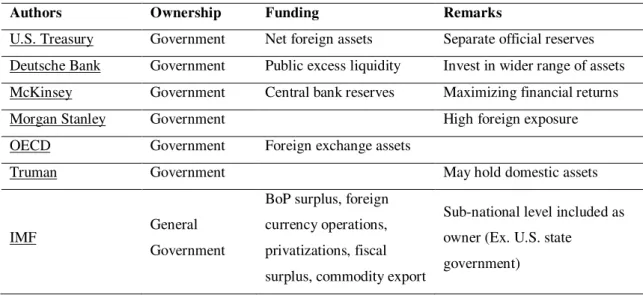

Table 2: Similarities on definitions from different sources

Authors Ownership Funding Remarks

Government

U.S. Treasury Net foreign assets Separate official reserves

Government

Deutsche Bank Public excess liquidity Invest in wider range of assets

Government

McKinsey Central bank reserves Maximizing financial returns

Government

Morgan Stanley High foreign exposure

Government

OECD Foreign exchange assets

Government

Truman May hold domestic assets

General Government IMF

BoP surplus, foreign currency operations, privatizations, fiscal surplus, commodity export

Sub-national level included as owner (Ex. U.S. state

government)

Trying to aggregate the dispersed opinions about SWFs, we can sum it up by saying they are basically large publicly owned investment vehicles. This reason is enough for assuming sovereignty is a proper characteristic used to name the funds.

Although there is no commonly accepted definition of SWFs, one can rely on the assumption that most observers agree on three common elements. SWFs are:

1. State-owned;

2. Have no or only very limited explicit liabilities; and

3. Managed separately from official foreign exchange reserves.

Having the context of what the topic relates to, this dissertation adopts an official definition, which is the one developed by the IMF IWG for the Santiago Principles13, document explained in detail in section 3. Since this standing working group is a multilateral effort to institutionalize the study of the SWF, having taken into consideration the opinion of the SWF holders themselves, this definition is assumed as reliable and efficient:

“SWF excludes [...] foreign currency reserve assets held by monetary authorities only for the traditional balance of payments (BoP) or monetary policy purposes, operations of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the traditional sense, government-employee pension funds, or assets managed for the benefit of individuals” (IMF, 2009, p.5).

The IMF nomenclature also distinguishes both private investors and other forms of public investments. It defines SWFs as special purpose investment funds or arrangements, owned by the general government; both central and sub-national government (including the state level government as the reason why the North-American funds are considered SWF and the U.S. and Canada are member countries of the IWG14). Likewise, “SWFs hold, manage, or administer assets to achieve financial objectives, and employ a set of investment strategies which include investing in foreign financial assets” (SWF GAPP, p.27).

13 Available

been made, as it has been common sense to consider the IMF initiative as the official one.

14 Not occasionally the United States is on the most interested countries on regulating SWF policies, being one of

Their resources come out of balance of payments surpluses, official foreign currency operations, the proceeds of privatizations, fiscal surpluses, and/or receipts resulting from commodity exports (IMF, 2008, in DAS et al., 2009).

This definition, rescuing the common aspects observed by the majority of authors described earlier in this section, implies the three elements that make SWF unique: public ownership; capital source; and the underlying purpose, as the following table summarizes.

Table 3: Summary of SWF’s single characteristics

Definition Ownership Source Purpose

SWF Public (State owned) Commodity exports; non-commodity exports, like fiscal surpluses

responseto the

accumulation of wealth Source: Author, 2009.

2.3.1 Public Ownership

Primarily, ownership is a fundamental criterion in the definition of these funds. SWFs are investment funds that are owned by a state (KERN, 2007). This means they are public actors who invest in private markets. Whereas the IMF includes sub-national level funds as well, Lyons (2007, p.6) argues that the owner has to be a sovereign government, excluding sub-national entities (sub-national state rather than a regional or local state, p.23). Lyons concept is more linked to the realist school of thought of the theory of the international relations, based on the sovereign State as a single player in the global scenario. Hitherto, the sub-national funds do not occupy a major stake of the argumentation in this discussion.

Public pension funds15 ensure the future pension benefits of a state’s citizens. These funds are generally denominated in local currency and have low exposure to foreign assets (KIMMITT, 2008, p.1). However, the main underlying criterion is how these funds are financed. If a pension fund is financed through foreign exchange assets coming from commodity exports, then this fund can be counted as an SWF (LYONS, 2007, p.23). The related example is the Norwegian Government Pension Fund – Global, financed through fiscal revenues, to be described further in section 4.3.

On the liabilities of the SWFs, if they have any, they are part of the broader national balance sheet, i.e., there is no outside (non-governmental) liability (MONK, 2009, p.9). According to Beck and Fidora (2008), the shortage of liabilities make the SWFs differ from sovereign pension funds that operate subject to explicit liability and a continuous stream of fixed payments, making sovereign wealth funds more similar to private mutual funds (BECK and FIDORA, 2008, p.6). The focus of this dissertation is on the no or low-liability funds.

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) are companies over which the state has significant control. This category includes a wide variety of entities, from manufacturing to financial firms (KIMMITT, 2008). These companies are liable to the general government of each country.

The confusion happens if the SOE is a sovereign wealth enterprise – a sovereign investment vehicle that is owned and controlled by a sovereign wealth fund in order to intermediate the SWFs investments, seeking, for instance, taxation gains16. Then, it is directly under the control of an SWF (SWF Institute, URL access September, 2009).

Finally, international reserves, as defined by the IMF (Glossary of Statistical terms), are “external assets controlled by a country’s authorities for direct financing of international payments imbalances or for indirect regulation of such imbalances through intervention in foreign exchange markets to affect the exchange rate”. Kimmitt (2008, p.1) states that the

15 For complete study about SWF and Pension Fund Issues, see the OECD publication by Blundell-Wignal, Hu,

and Yermo (2008). According to them, Sovereign Pension Reserve Funds (SPRFs), a type of Public Pension Reserve Fund (PPRF), may be considered a type of SWF with an exclusive mandate to finance future public pension expenditures (OECD, 2008, p. 118). This is not the definition of pension fund this dissertation will employ. Refer to the table below for illustration of differences between the funds adopted in this dissertation.

16 This is akin to SPE, “special purpose entity” or SPC, “special purpose company”, common in the Real Estate

purpose of holding such reserves is to help in case of an export shortfall or to defend the currency in a financial crisis. In most cases, these reserves are managed by the country’s Central Bank (KERN, p. 2). However, transfers from international reserves can be an important source for SWF, especially in Asian growing economies.

Table 4: Sovereign Investment Vehicles Characteristics

SWFs SOEs Public Pension

Funds

International Reserves Asset

ownership Government

Primarily

government Pension member

Central Bank or Government

Primary

purpose Varies Varies

Fund defined benefits obligations Monetary policy management Funding source Commodity / Non-commodity Government / Corporate earnings Pension

contributions BoP surplus

Government

control Total Significant Insignificant Total

Disclosure Varies Varies Transparent Varies

Investor class

growth High Steady Steady

Steady in developed countries

Examples ADIA, CIC,

KIC, KIA Chinalco, Banco da Amazônia, Rosneft, EDF CalPERS, CalSTRS, NYSTRS, Teacher Retirement System of TX Usually not separate institutions. SAFE (China), NBM (Norway)

Source: Adapted from swfinstitute.org

2.3.2 Sources of Funding

A common definition of SWF based on sources supposes funding through state owned foreign exchange assets (see Adrian Blundell-Wignall, Yu-Wei Hu & Juan Yermo, OECD, 2008). However, the definition of the IMF also includes “fiscal surpluses” and “proceeds of privatizations”. The classification assumed in this dissertation is that these funds can steam from basically two sources of wealth accumulation, as the section 4 clarifies. Nonetheless,

there could be stressed sources of funding, which are distinct from the source of wealth, as it

is related to the mechanism of internalization of the extra resources. Generally, the literature classification is intimately related to the wealth accumulation, defined as an outcome of commodity exportation resources, international reserves accumulation or fiscal surplus. This dissertation analyses the mechanism of usage of the wealth – source of the fund itself, in a more comprehensive manner in the selected cases.

The sources of wealth accumulation by the countries are: commodity exports and non-commodity exports, as the majority of sources point out.

1. Commodity funds are financed through commodities owned or taxed by the government (KIMMITT, 2008, p.1). To be more precise, the export of these commodities leads to accumulation of foreign exchange assets. Thus, these funds actually are based on the endowment of a country with natural resources. Most SWF are financed by the sale of commodities, especially oil (GILSON & MILHAUPT, 2008, p.13).

2. Non-commodity funds are funded through a transfer from official foreign exchange reserves17

17 “To be considered reserves, foreign currency generally must be invested in liquid and marketable instruments

that are readily available to the monetary authorities to meet a balance of payments need” (LOWERY, 2007, in DEVLIN and BRUMMITT, 2008).

than enough reserves for preventive motives are, thus, transferring these foreign assets into SWF18 (GRIFFITH-JONES & OCAMPO, 2008, p. 8).

As the paper by Griffith-Jones and Ocampo states, “the large accumulation of foreign exchange assets by developing countries has become a characteristic feature of the 2000s” (2008, p.31). Not surprisingly, as a consequence of this fact, most non-commodity funds are of this decade, as the history of the SWFs demonstrated, hosted basically in Asia, as it is the case of China (2007), South Korea (2005) and Taiwan (2001) (LYONS, 2007, p. 27).

Graph 2: Global Payment Imbalances

Observation: Foreign reserves of selected East Asian economies.

Data for 2007 are calculated as an average over the eight months to August. Source: IMF International Financial Statistics, in Devlin and Brummitt (2008)

Reserve managers of East Asia are increasingly channeling the ‘excess’ reserves into dedicated investment vehicles (SWFs) with explicit mandates to earn higher returns on their invested funds, although the majority still prefers purchasing highly liquid foreign government securities (DEVLIN & BRUMMITT, 2008, p. 122).

Joshua Aizenman and Reuven Glick (both in 2007 and 2008) state that, since the global sum of all current accounts adds up to zero by definition, SWF based on reserves have ultimately

18 This is the case of East Asian countries, which have combined SWFs in excess of $740 billion dollars, to be

come into existence through an international wealth transfer from debtors in one country to creditors in others19.

Some authors would classify the sources from a different perspective, identifying a third category. When a government unexpectedly receives a bulky sum of money whatsoever, that is not persistent, this special situation can be called ‘windfall’. The source can be, for instance, either through privatization of companies or unexpected tax revenues. J.P. Morgan Bank (FERNANDEZ & ESCHWEILER, 2008, p.5), in a similar categorization, labels this “fiscal sources”, with sources specified as “property sales and privatizations or transfers from the government’s main budget to a special purpose vehicle”. The example given is China, mostly simply known as non-commodity. This case will be analyzed in section 4.2.

Kimmitt (2008) notes that commodity-based funds are prone to multiple and changing objectives, including fiscal revenue stabilization and sterilization of foreign currency inflows. “They (commodity funds) serve different purposes, including stabilization of fiscal revenues, inter-generational saving, and balance of payments sterilization” (USTreas, 2007, p.1).

On the other hand, “non-commodity-based funds are more commonly used to make stand-alone investments when a country has accumulated reserves in excess of the ‘optimal’ level” (GRIFFITH-JONES & OCAMPO, 2008, p. 9).

The picture below, cited in several papers, illustrates the upper echelon of SWFs as regards the source of funding and transparency.

19 In this view the excess saving and accumulation of foreign assets by surplus countries is the counterpart to the

Graph 3: Commodities and Non-commodities funds

Source: Adapted from the SWF Institute. Last update: March, 2008.

The non-commodity group of countries, especially in Eastern Asia, has established SWFs because reserves are being accumulated in a level higher than of what may be needed for intervention or BoP purposes. “The source of reserve accumulation for these countries is mostly not linked to primary commodities but rather related to the management of inflexible exchange rate regimes” (BECK & FIDORA, 2008, p. 6).

Whereas there is the non-commodity category for the funds, as the graph shows, the main group of countries that have established SWFs are resource-rich economies, that have relied on the high prices of oil and commodity. The creation of the Funds makes sense since the commodities exploited are non-renewable, what justifies the saving of resources in case of a certain future shortage. The next section, on purpose of investment, is detailing this idea.

2.3.3 Investment Purpose

Lastly, SWF differ also from private investor in their raison d’être. While private funds are

set up in order to accumulate wealth, SWF are set up in response to the accumulation of wealth (MONK, 2009, p.11). As a result, the funds usually have definite core objectives and therefore a specific investment strategy.

(ii) savings funds, (iii) reserve investment corporations, (iv) development funds, and (v) contingent pension reserve funds.

(i) Stabilization funds:20 created by resource-rich states in order to cushion the effect of volatile commodity prices – i.e. to build up resources in successful years in order to intervene in leaner years when commodity prices decline. As Beck and Fidora (2008, p. 6) argue, “in these countries, SWFs partly serve the purpose of stabilizing government and export revenues which would otherwise mirror the volatility of oil and commodity prices”. Truman (2007, p. 4) states that the aim of such funds is to achieve medium-term macroeconomic stability, including sterilization of the domestic economic and financial effects of surges in export earnings.

(ii) Saving funds: are also based on commodity funds that have counter-cyclical fiscal policies, which deliberation is to share wealth across generations. A proportion of non-renewable natural resources earning is invested, aiming to preserve the wealth of the country for future generations. Besides that, many authors say these funds attempt to alleviate the effects of the so-called “Dutch disease”21. It refers to the fact that a boom in one sector of the

economy leads to a loss of competitiveness in the other (IMF GAPP, 2008, p.13).

Continuing Beck and Fidora (2008, p. 6) argument, another purpose of such funds in resource-rich countries is the accumulation of savings for future generations as natural resources are non-renewable and are hence anticipated to be exhausted after some time. “This is the case for many oil producers who, in order to avoid sharp adjustments of fiscal policy once oil reserves are depleted, accumulate financial assets during the period in which they produce oil” (BECK & FIDORA, 2008, note 6). Consequently, resource-based revenues are gradually transformed into financial wealth, provided unchanged wealth for the country and preserving it for next generations. Along with the rise in commodity prices, the number of saving funds has increased.

20 The IMF has an Occasional Paper published in April 2001 about Stabilization and Savings Funds for

Nonrenewable Resources.Available at

21 According to Professor Bresser-Pereira from Fundação Getulio Vargas (2008), “the Dutch disease is a major

In accordance with Griffith-Jones and Ocampo (2008, p.25), the distinction between savings funds and stabilization funds is that the former can invest with longer term criteria, whereas the later – given their cyclical role – would seem to need higher proportions of relatively more liquid assets. Thus, the liquidity needs of stabilization funds can be considered as intermediate between normal foreign reserves and savings funds (GRIFFITH-JONES & OCAMPO, 2008, p.25).

The following chart illustrates the high in prices for commodities during the current decade, what has been associated to the creation of saving funds in recent years.

Graph 4: Commodity Boom (then recent bust)

Observation: Data of December/2008. Scale: 2000 =100. Source: IMF IFS database

(iii) Reserve investment corporations: the assets of this type of funds are established as a separate entity next to the official reserve management, seeking to attain higher returns than with usual reserve investments. The latter generally prefers lower risk assets and higher liquidity, which usually implies lower returns.

“strategic or political objectives”22. Recently, Chile government has announced that the new sovereign fund (BF) might finance higher education for Chileans abroad. Once established, this fund may be considered a development fund.

(v) Pension reserve funds: have identified pension and/or contingent-type liabilities on the government’s balance sheet, whose sources are other than individual pension contributions. Hence, they include the Norwegian SWF – Global, which is non-contingent, but exclude the CalPERS fund, which does carry possible future liabilities that will become certain on the occurrence of some future event.

Certainly SWF have multiple and/or evolving objectives (IMF Work Agenda, 2008, p.5). Overall, the objective and the related investment strategy do confine SWF from private investors aiming solely the maximization of risk-adjusted financial returns.

However, understanding the purposes of the investment of different SWF is necessary to ensure confidence for the recipient countries, as the section 3 will show.

2.4

Learning from the literature review

All the texts referred so far will be used to build the descriptive study. The principal message of this section is the elucidation of the concept, as well as its classification.

However, they generally slack on describing thoroughly the mechanism of accumulation of wealth. Hardly ever one can find detail of the majority of commodity funds internalization of the external capital. Most of them seem to be satisfied with the fact the missing transparency of sovereign funds obstacles the comprehension of the modus operandi of the investments.

22 According to the OECD publication (Blundell-Wignall, Hu and Yermo, 2008, p.118), the objectives of SWF

For example, the Chilean case, unanimously classified as commodity fund due to the copper exportation, could be actually labeled as fiscal surplus fund if the classification is related to the source of funding. Of course the excess revenues from the metal trade across Chile boundaries are the source of glut capital. This is actually the source of wealth. However, the real fund is only possible because of the austerity of the finance ministry in the management of the wealth. Such interpretation is provided at the case studies this dissertation launches.

The best contribution of this dissertation is the comparative analysis of three different funds from Chile, China and Norway, aiming to discuss the feasibility of the fund held by Brazil.

Apart from the official countries’ websites and the IMF database and the OECD country profile statistics, there will be presented other references about each country.

For the Chilean case, the OECD publication of 2007 by Rodriguez, Tokman and Vega, inter alia, is a considered reference. Another paper, based on studies of the CEPAL/ECLAC23, “Sovereign Wealth Funds: A Developing Country Perspective” by Griffith-Jones and

Ocampo (2008) is relevant not only for the Chilean situation, but also for the Brazilian debate, as the Latin American economies are central for their approach.

For the Chinese case, the dissertation uses, among other sources, “China’s Sovereign Wealth Fund”, by Michael F. Martin for the Congressional Research Service of the U.S., January, 2008. The CIC case is also studied by Ashby Monk, research fellow of the University of Oxford, in his 2009 text “Recasting the Sovereign Wealth Fund Debate: Trust, Legitimacy, and Governance” (p.18-22) and by Brad Setser (2008), having both a survey about the

concerns of the North-Americans toward the CIC. Steffen Kern, once again, for the Deutsche Bank Research, has an update of his study about SWFs released in 2008, focusing attention on China.

For the Norwegian case, the Norges Bank website provides most of the information about the fund, even publicizing the portfolio of assets held by both funds. Still, the 2006 report from the Secretary General of the Ministry of Finance of Norway, Tore Eriksen, “The Norwegian

Petroleum Sector and the Government Pension Fund – Global” is a relevant reference, since it starts by comparing the Chilean case too.