Escola de Economia e Gestão

Orlanda Cristina Araújo Baptista

The impact of ESG criteria on

portfolio financial performance

Universidade do Minho

Escola de Economia e Gestão

Orlanda Cristina Araújo Baptista

The impact of ESG criteria on portfolio

financial performance

Dissertação de Mestrado

Mestrado em Finanças

Trabalho efetuado sob a orientação do(a)

Professora Doutora Benilde Maria do

Nascimento Oliveira

ii DIREITOS DE AUTOR E CONDIÇÕES DE UTILIZAÇÃO DO TRABALHO POR TERCEIROS

Este é um trabalho académico que pode ser utilizado por terceiros desde que respeitadas as regras e boas práticas internacionalmente aceites, no que concerne aos direitos de autor e direitos conexos.

Assim, o presente trabalho pode ser utilizado nos termos previstos na licença abaixo indicada.

Caso o utilizador necessite de permissão para poder fazer um uso do trabalho em condições não previstas no licenciamento indicado, deverá contactar o autor, através do RepositóriUM da Universidade do Minho.

Licença concedida aos utilizadores deste trabalho

Atribuição-NãoComercial-CompartilhaIgual CC BY-NC-SA

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

Universidade do Minho, ___/___/______

iii

Acknowledgements

I am proud for reaching this moment and grateful to all the people that support me throughout this process.

I would like to sincerely express my gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Doctor Benilde Oliveira, for her guidance, willingness in clarifying my doubts, all her effort and availability to help me.

Additionally, I would like to acknowledge Professor Doctor Gilberto Loureiro’s help and availability, in guiding me through the software used on my dissertation.

I would like to thank all my friends from Madeira, that joined me on this journey in University of Minho. They were like a family to me and made the distance from home feel shorter.

I want to dedicate this dissertation to my parents that have always dreamt this journey for me. I am lucky and truly happy for having you always by my side, your unconditionally support and love.

To the most important person in this journey, my boyfriend Marco Santos, that made me get out of my comfort zone, be more ambitious and dream bigger. For your patient, love, encouragement and especially emotional support, I want to thank you. I will be grateful for the rest of my live for having you during this challenging path.

iv STATEMENT OF INTEGRITY

I hereby declare having conducted this academic work with integrity. I confirm that I have not used plagiarism or any form of undue use of information or falsification of results along the process leading to its elaboration.

I further declare that I have fully acknowledged the Code of Ethical Conduct of the University of Minho.

Universidade do Minho, ___/___/______

v The impact of ESG criteria on portfolio financial performance

Abstract

The increasing demand of investors for SRI, in the last 30 years, has stimulated the scientific community to study the impact of ESG criteria on investment financial performance. Theory suggests that if it was beneficial to invest in SRI, this advantage disappeared as soon as markets participants fully incorporated the information about SRI firms. More recent studies state that investors not only hold SRI because of their ethical beliefs but also because it reduces their downside risk. The aim of this dissertation is to analyse if different ESG dimensions impact SRI financial performance during different market conditions. For this purpose, it is constructed and assessed the performance of two distinct portfolios based on ASSET4 ESG scores. The monthly sample comprises US SRI companies from 2002 to 2017. Portfolio performance is assessed on the basis of the popular Carhart (1997) four-factor model and the recent Fama and French (2015) five-factor model. Several robustness checks, for alternative weighted scheme, screen approach, different cut-offs and the exclusion of financial firms, are implemented. Additionally, a dummy constructed based on NBER business cycles to account for different market conditions, is added to the models. The results suggest that if investors implement a Long-Short strategy based on the GOV or ESG dimensions (and SOC in the case of the five factor-model), they obtain negative abnormal returns. The results for earlier sub-periods show that ESG portfolios have, in fact, a neutral financial performance, however, the tendency seems to have changed in 2012 to a negative financial performance. Moreover, by including a dummy variable in the models it is shown that portfolio performance does not significantly change according to the state of the economy.

Keywords: ESG criteria; Performance of Stock Portfolio; Recession Periods; Socially

vi O impacto das dimensões ESG na performance financeira dos portfólios

Resumo

A crescente procura dos investidores pelos ISR, nos últimos 30 anos, estimulou a comunidade científica a estudar o impacto dos critérios de ESG na performance financeira do investimento. A teoria sugere que era benéfico investir em ISR mas esta vantagem desapareceu assim que os participantes do mercado incorporaram toda a informação sobre as empresas SR. Estudos mais recentes referem que os investidores não só detêm ISR por causa das suas crenças éticas, mas também porque estes investimentos são capazes de reduzir o risco potencial negativo. O objetivo desta dissertação é analisar se diferentes dimensões de ESG impactam a performance financeira dos ISR durante diferentes condições de mercado. Para este propósito, foram construídos e medida a performance de dois portfólios distintos com base nos índices de ESG da ASSET4. A amostra mensal engloba empresas dos EUA entre 2002 e 2017. A performance é medida através do modelo de quatro fatores de Carhart (1997) e do recente modelo de cinco fatores do Fama e French (2015). Foram implementados diversos testes de robustez, como um alternativo esquema de ponderação do portfólio, abordagem de construção do portfólio, diferentes cut-offs e exclusão de empresas financeiras. Além disso, uma dummy construída com base nos ciclos de negócio da NBER, para capturar as condições de mercado, é adicionada aos modelos. Os resultados sugerem que se os investidores implementarem uma estratégia Long-Short baseada nas dimensões de GOV ou ESG (e SOC no caso do modelo de cinco fatores), irão obter retornos negativos. Os resultados para os primeiros subperíodos mostram que, de facto os portfólios ESG apresentam performance financeira neutra, contudo, a tendência parece ter mudado em 2012 para uma performance financeira negativa. Incluindo uma variável dummy nos modelos verifica-se que a performance dos portfólios não se altera significativamente de acordo com os estados da economia.

Keywords: critérios de ESG; Performance de portfólios de ações; Períodos de Recessão;

vii

Table of Content

Acknowledgements ... 3 Abstract ... 5 Resumo ... 6 List of Acronyms ... 8 List of Tables ... 9 List of figures ... 10 List of Appendices ... 11 1.Introduction... 13 2.Literature Review ... 162.1 An overview about SRI ... 16

2.2 The performance of SRI versus the performance of conventional strategies ... 17

2.3 Empirical evidence on the performance of SRI ... 18

2.4 Investing in SRI: “the learning hypothesis” ... 23

2.5 SRI in Recession Periods ... 24

3.Methodology and Dataset ... 27

3.1 ESG Portfolio Construction ... 27

3.2 Performance Measurement ... 28

3.3 Recession Periods ... 29

3.4. Dataset Description ... 31

4. Results ... 34

4.1 Performance Evaluation ... 34

4.2 Robustnes checks: weightning scheme, screen approach, different cut-offs and the exclusion of financial firms ... 37

4.3 Performance in expansion versus recession periods ... 42

5. Conclusion ... 46

References ... 48

viii

List of Acronyms

Acronyms ESG ENV GOV NBER SOC SRI US DescriptionEnvironmental, Social and Governance Environmental

Governance

National Bureau of Economic Research Social

Socially Responsible Investing/Investments United States

ix

List of Tables

Table 1- Descriptive statistics of portfolios’ returns ... 33

Table 2 - Portfolio performance estimates- Carhart (1997) four-factor model ... 35

Table 3- Portfolio performance estimates- Fama and French (2015) five-factor model... 36

Table 4 - Long-short portfolio performance estimates depending on the weighting scheme ... 38

Table 5 - Long-short portfolio performance estimates depending on the screen approach ... 39

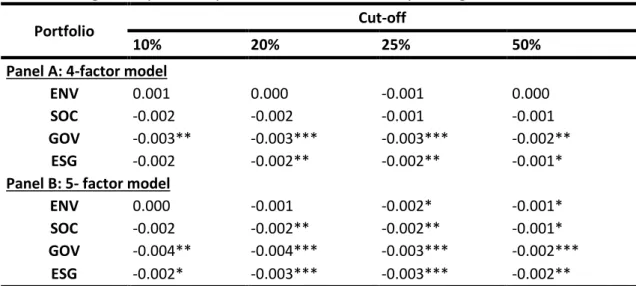

Table 6- Long-short portfolio performance estimates depending on the cut-off ... 40

Table 7- Long-short portfolio performance estimates for different subperiods ... 41

Table 8- Long-short performance estimates of portfolios with and without financial firms ... 42

Table 9- Portfolio performance estimates - Carhart (1997) four-factor model with dummies ... 44

Table 10- Portfolio performance estimates - Fama and French (2015) five-factor model with dummies ... 45

x

List of figures

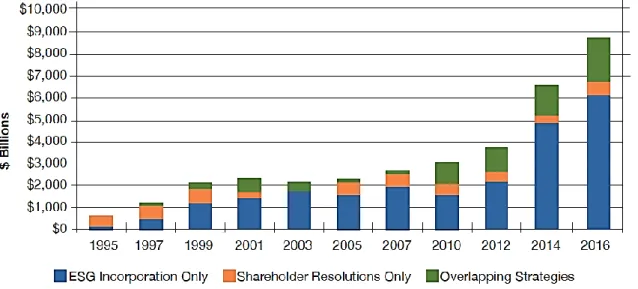

Figure 1- The growth evolution of SRI in the United States (source: USSIF 2016 Trends report) ... 13 Figure 2- Monthly evolution of the US Market Portfolio, available on the Professor Kenneth French

webpage, over the period of January 2002 to September 2017. ... 30

Figure 3- Monthly excess returns of the US Market portfolio, available on the Professor Kenneth

xi

List of Appendices

Appendix A - Definition of Market States according to NBER Business cycles ... 53 Appendix B - Descriptive statistics of value weighted portfolios returns ... 54 Appendix C– Portfolio performance estimates of the value-weighted scheme– Carhart (1997) four-factor model………. ... 54 Appendix D– Portfolio performance estimates of the value-weighted scheme – Fama and French (2015) five-factor model ... 55 Appendix E- Descriptive statistics of Best-in-Class portfolios returns ... 56 Appendix F– Portfolio performance estimates of the Best-in-Class approach- Carhart (1997) four-factor model…………... 56 Appendix G – Portfolio performance estimates of the Best-in-Class approach- Fama and French (2015) five-factor model ... 57 Appendix H– Portfolio performance estimates depending on the cut-off- Carhart (1997) four-factor model……….………57 Appendix I- Portfolio performance estimates depending on the cut-off- Fama and French (2015) five-factor model……….58 Appendix J- Portfolio performance estimates for different subperiods- Carhart (1997) four-factor model………..58 Appendix K- Portfolio performance estimates for different subperiods- Fama and French (2015) five-factor model……….59 Appendix L- Descriptive statistics of portfolio returns without financial firms ... 60 Appendix M- Performance estimates of portfolios without financial firms– Carhart (1997) four-factor model….………60 Appendix N- Performance estimates of portfolios without financial firms– Fama and French (2015) five-factor model ... 61 Appendix O– Portfolio performance estimates of the value weighted scheme – Carhart (1997) four-factor model with dummies ... 62 Appendix P- Portfolio performance estimates of the value weighted scheme – Fama and French (2015) five-factor model with dummies ... 63 Appendix Q- Portfolio performance estimates of the Best-in-Class screen approach – Carhart (1997) four-factor model with dummies ... 64 Appendix R - Portfolio performance estimates of the Best-in-Class screen approach – Fama and French (2015) five-factor model with dummies ... 65 Appendix S- Portfolio performance estimates depending on the cut-off– Carhart (1997) four-factor model with dummies ... 66 Appendix T- Portfolio performance estimates depending on the cut-off – Fama and French (2015) five-factor model with dummies ... 67

xii Appendix U– Performance estimates of portfolios without financial firms– Carhart (1997) four-factor model with dummies ... 68 Appendix V– Performance estimates of portfolios without financial firms– Fama and French (2015) five-factor model with dummies ... 69

13

1.Introduction

Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) is an investment style that considers the incorporation of environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria, with the intent to obtain competitive financial returns while positively impacting the society. Market participants engaging in SRI not only want to have financial products consistent with ethical values, but they also seek to achieve long-term competitive financial returns, manage risk, fulfil fiduciary duties or even contribute to the development of ESG practices (USSIF 20171).

Over the last few decades, SRI has experienced an exponential growth around the world. According to USSIF 2016 Trends report2, the total SRI assets under

management grew 33% between 2014 and 2016 and in the beginning of 2016 represented $8.72 trillion. Moreover, the number of investment funds incorporating ESG criteria grew between 1995 and 2016, from 55 with a total net asset of $12 billion to 1002 with a total net asset of $2597 billion (figure 1).

Along with the growth of interest in SRI there has been an increase in the volume of research studying the impact of ESG criteria on investment financial performance.

1 Based on The Forum US Sustainable, Responsible and Impact Investment website – see

https://www.ussif.org/sribasics and https://www.ussif.org/esg.

2 According to annual USSIF Report on US sustainable, Responsible and Impact Investing Trends 2016.

14 However, the existing literature presents puzzling results about SRI performance. Despite some evidence that SRI delivers positive abnormal returns, there seems not to be a consensus on which ESG dimension or which type of screen approach (positive, negative or Best-in-Class) positively impacts SRI financial performance.

In fact, due to the fast growth experienced by SRI, there was information asymmetries in the 1990s that financially favoured SR investors. Since most events that shaped SRI occurred in 1980 (Renneboog et al., 2008a and Bebchuk et al., 2013), in the 1990s investors and financial analysts did not have enough skills to perceive the performance difference between companies with good and bad CSR practices, so, at that time, SRIs were not yet correctly priced, providing abnormal returns to investors. However, under the Bebchuk et al. (2013) “learning hypothesis”, market participants gradually acknowledged the differences between SR and non-SR firms and once a sufficient number of investors fully incorporated these differences, stocks became correctly priced and the positive association between ESG criteria and financial performance disappeared. Additionally, many researchers have captured the persistence of abnormal returns in the 1990s and the consequent disappearances in the early 2000s (e.g. Derwall et al., 2011; Bebchuk et al., 2013 and Borgers et al., 2013).

Consequently, researchers have been questioning the reason why SRI demand continues to increase if they no longer are able to outperform the market. Even if “values-driven” investors are willing to quit some financial benefits in order to have investments consistent with their believes, the “profit-seeking”3 investors do not.

Additionally, Nofsinger and Varma (2014) suggest that investors can reduce their downside risk because SRIs perform better during recession periods.

The purpose of this dissertation is to analyse the relationship between ESG criteria and portfolio performance, while controlling for market states. In this context, using rankings constructed based on Asset4 ESG scores, two portfolios scoring distinct in ESG criteria are constructed for each ESG dimension. In addition, to analyse the differential impact of the ESG criteria on financial performance between the two

3 Nilsson (2009) identified three types of SRI investors: those who base their investment decision only on risk/return (“profit-seeking”

investor); those who base their investment decision only on Social Responsibility (“values-driven” investor); and finally, those who make their investment decision based simultaneously on return and Social Responsibility.

15 portfolios, a Long-Short strategy is followed. This methodology not only allows the independent analysis of the impact of each ESG dimension on portfolio performance, but it also overcomes the limitations related to SR funds’ performance. The labelled SR funds sometimes do not maintain their SR status over time or invest in stocks with lower ESG scores than their conventional counterparts (Auer, 2016; Wimmer, 2013 and Henke, 2016).

In order to assess the SR portfolios’ performance, the popular Carhart (1997) four-factor model and the recent Fama and French (2015) five-factor model are used. However, these models do not allow risk and return to vary over time, which can provide biased results. Some recent studies (e.g. Silva and Cortez, 2016; Henke, 2016 and Nofsinger and Varma, 2014) argue that the performance of SRI may be state dependent, and these studies therefore advocate the use of models that allow for risk and return to vary according to different market states. Consequently, in this study a dummy variable is added to the four and five-factor models to allow for risk and return to vary according to the NBER business cycles of recession and expansion.

To the best of my knowledge, this dissertation contributes to the existing literature in the extent that it assesses synthetic portfolio performance during different market conditions and also offers the perception of how each ESG dimension impacts portfolio performance. Additionally, this study gives more recent insight about US SRI performance. The sample is comprised of 2357 US companies from January 2002 to September 2017. This sample is larger than the one used by Halbritter and Dorfleitner (2015) (concerning Asset4 data) and allows a sight to whether or not SRI financial performance has persisted over the last years.

The remainder of this dissertation is developed into 4 additional sections. The following section (section 2) summarizes and discusses the most relevant studies concerning SRI and portfolio performance. In section 3, the dataset is described, the definition of market states is presented, and also the methodology implemented to assess portfolio performance is described. Section 4 reports and discusses the results. Finally, section 5 concludes and presents some limitations of this dissertation.

16

2.Literature Review

This section reviews, summarizes and discusses the most relevant studies on SRI. Firstly, it gives an overview about SRI and its popularity, and afterwards, a discussion on the performance of SRI as well as on the methodologies used to assess it, is presented. The last part of this section is dedicated to the review of empirical studies that control for different market states when assessing financial performance.

2.1 An overview about SRI

Since the beginnings of the 90s the industry of SRI has been rising considerably worldwide. The origins of SRI come from religious traditions and developed due to the growing demand of products that were consistent with the consumers’ ethical values. Due to a series of environmental disasters, social campaigns and posteriorly corporate scandals, factors like Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) turn out to be important to investors when screening their investments (Renneboog et al., 2008a).

Commonly, SRI is seen as an investment in which decisions are based on ethical and personal values instead of financial wealth (Derwall et al., 2011). But, according to more recent studies, SR investors not only base their investment decision on the ethical and personal factors, but also on risk-reward optimization to derive their utility function from owning the securities. For instance, Nilsson (2009) identified three types of SRI investors: those who base their investment decisions only on risk/return (“profit-seeking” investor); those who base their investment decisions only on Social Responsibility (“values-driven” investor); and finally, those who make their investment decision simultaneously based on return and Social Responsibility.

According to USSIF (2018) one of the strategies that investors can follow to engage in SRI, is to encourage firms to adopt Corporate Social Responsibility practices through shareholders proposals. The other strategy, with more expression in the market, is to incorporate ESG criteria to select a portfolio across a variety of asset classes. An important segment of this strategy is to finance projects with the intent to develop and help underserved communities.

17 SRI investors following ESG incorporation strategy can choose to invest in SRI funds or construct themselves a portfolio consistent with their ideals. In order to fulfil investors’ standards, different screen approaches can be implemented when building a SR portfolio. The negative approach is the most basic and the oldest, which excludes specific stocks or industries that do not rely on SRI ideologies (e.g. gambling, tobacco, alcohol). The positive approach consists in selecting stocks that meet superior SRI standards. Finally, is the Best-in-Class approach, where portfolios are constructed selecting high rated SRI stocks from each industry. This last approach emerged with the intent to overcome problems of sector biases and loss of diversification.

2.2 The performance of SRI versus the performance of conventional strategies

Since the pioneering study of Moskowitz’s (1972), SRI has been widely studied by empirical researchers in the last few years. Most studies on SRI seek to investigate whether or not adding ESG criteria to the investment selection process has a positive impact on portfolio returns. However, the conclusions of these studies are puzzling because the expected performance of SR portfolios can be either lower, higher or equal to the performance of conventional investments. Hence, different theoretical arguments appeared in the literature in order to explain the impact of ESG criteria on portfolio performance (see Hamilton and Statman, 1993; Bauer et al., 2005; Mollet and Ziegler, 2014).

Following Markowitz’s (1952) portfolio theory, SRI portfolios have problems of diversification and optimization, since they are constructed from a restricted universe of investments, thus leading to lower performance. Traditionally, investors are assumed to make investment decisions considering only the risk and return. This does not happen with SRI investors (values-driven investor) since they shun controversial stocks that are proved to present higher returns (Statman and Glushkov, 2009; Derwall et al., 2011; Salaber, 2013). Derwall et al. (2011) discusses the shunned-stock hypothesis, which states that relaxing the assumption of symmetrical information of the CAPM (Merton, 1987), the markets will segment due to different investors’ bases, which will affect stock prices. Investors tend to invest more on certain stocks (SRI stocks) and neglect other

18 stocks (controversial stocks) that will be traded at a discount due to a low demand. On the contrary, the increased demand for SRI stocks turns them overpriced generating lower expected returns. Additionally, SRI investors incur in higher costs due to extra informational needs, screening and monitoring processes (Bauer et al., 2005).

A more contemporary view, states that aligning all stakeholder’s interests, including dimensions like social responsibility, creates more value for shareholders, and improves financial performance (Waddock and Graves, 1997; Freeman et al., 2010). If investors do not recognize it, the SRI stocks will be underpriced and, consequently, will generate higher expected returns than conventional stocks. Furthermore, social screens provide tools to select companies with higher management skills, and thus, SRI stock portfolios will experience higher financial performance in the long run (Bollen, 2007).

The third argument is in line with an adaptation of the efficient capital market theory made by Daniel and Titman (1999). It suggests that if it is possible to earn abnormal returns using public information, this ability will disappear over time as soon as this information is perceived by the market’s participants. Studies made by Bebchuk et al. (2013) and Borgers et al. (2013) report positive abnormal returns for SRI in the 1990s. However, these abnormal returns became insignificant in subsequent years. Their empirical results demonstrate that the mispricing of SRI gradually disappeared as investors learned the advantages of ESG criteria. Therefore, SRI stocks should not be mispriced and should not perform differently from their conventional counterparts.

2.3 Empirical evidence on the performance of SRI

Several researchers have been investigating the relationship between SR criteria and financial performance. These studies have been developed in different lines (Cortez et al., 2009). One body of the literature compares the financial performance of companies that score good and bad in CSR. For instance, Orlitzy et al. (2003) and Margolis and Walsh (2003) argue that financial performance is positively linked with CSR. A second strand compares the performance of SR indices with conventional indices and find that they do not perform differently (e.g. Sauer, 1997; Statman, 2006). The following reviewed papers cover the third and the fourth strand of the literature that

19 analyses the performance of SR versus non-SR funds and the performance of portfolios that scoring high versus low in ESG criteria, respectively.

Most researchers compare the performance of SR mutual funds with the performance of conventional ones. There is little evidence that SR and conventional funds perform differently. Studying worldwide SRI funds, Renneboog et al. (2008b) find that SR funds underperform in the market; and specifically in France, Ireland, Sweden and Japan, SR funds underperform their conventional counterparts. Additionally, in Bauer et al. (2005), the results show that US international ethical funds underperform their conventional counterparts for the period of 1990-1993, though US and UK domestic SR funds outperform conventional funds for the period of 1994-1997 and 1998-2001, respectively.

However, in general, these types of studies show that the performance of SRI funds are not statistically different from the performance of conventional funds. This evidence is found in studies based on the US market (e.g. Hamilton et al., 1993; Reyes and Grieb, 1998; Statman, 2000; Shank et al., 2005), the European market (e.g. Leite and Cortez, 2014), on other, more specific markets (e.g. Bauer et al. 2007), as well as on multi-country analyses (e.g. Bauer et al. 2005; Kreander et al. 2005; Cortez et al., 2009).

Nevertheless, this methodology presents some drawbacks as referenced by Auer (2016). In fact, a labelled SRI fund does not always maintain a social responsibility status as it is initially advertised. These changes are made by the manager due to other criteria that do not rely on the level of Social Responsibility (Wimmer, 2013). A recent study (Henke, 2016) revealed that one-third of the labelled SR bond funds, invest in bonds with lower ESG ratings than conventional funds. Contrary to the “real” SR funds that outperform the conventional ones, these “disguised” funds reveal no difference financial performance when compared with conventional funds. This might explain the fact that a significant number of studies, using this particular approach, have concluded that SR funds’ performance is not different from the performance of conventional funds. Moreover, Kempf and Osthoff (2007) point out that the financial performance of mutual funds cannot be only attributed to the SRI returns, but it must also consider the fund manager’s skills.

20 The other strand of literature that studies the performance of SRI uses synthetic portfolios. Contrary to SR funds, these portfolios have the particularity to display the effect of a particular ESG dimension on portfolio performance in isolation. This methodology has two approaches regarding the ranking source. The portfolios can be built using public lists or rankings of companies provided by rating agencies; or alternatively, they can be built using rankings of firms constructed based on public ESG scores of rating agencies. These types of studies have been presenting mixed results. Even though there is evidence that SR portfolios deliver superior abnormal performance, there is a lack of consensus in which public list, ESG dimension or screen approach investors should rely on to build SR portfolios with good financial performance.

Anderson and Smith (2006) find that constituent firms from the “America's Most Admired Companies” list perform better than the market. Moreover, Statman et al. (2008) and Angier and Statman (2010) find that the top companies underperform the bottom companies of this list. Similar results were found by Preece and Filbeck (1999) that analysed a portfolio composed by “100 Best Companies for Working Mothers”. This portfolio, composed by firms on this list, outperforms the market, but underperforms their matched sample. Although Filbeck et al. (2009) reached the same conclusion using “The Best Corporate Citizens”, additionally, they also find that rebalancing the portfolio each year, excluding the consecutive listed firms and including the new listed firms, enables the portfolio to outperform the market and its matched sample.

Other studies demonstrate that a portfolio composed by “100 Best Companies to Work for in America’’ outperform the market (Edmans, 2011) and its matched sample portfolio (Filbeck and Preece, 2003; Filbeck et al., 2009). Using the same public list, Carvalho and Areal (2016) find that some studies overestimated the performance of these companies because they did not consider time-varying models. In their study, a portfolio including all companies from the list, do not outperform the market while a portfolio with the top half of companies do.

A study conducted by Filbeck et al. (2013) explores the four public lists mentioned above. They state that using certain public rankings, (e.g. the “Best Corporate Citizens” and the “Most Admired Companies to work for in America”), to form

21 SR portfolios yield higher returns. Companies that are listed in two or three rankings in the same year produces incremental value. Moreover, only in the “Most Admired Companies”, a company reselected in the subsequent year produces incremental value. However, firms listed in “100 Best Companies to Work for in America” and “100 Best Companies for Working Mothers” do not outperform their matched sample.

Following a different approach and focusing on the concept of “eco-efficiency”, Derwall et al. (2005) measured the performance between two distinct SR stock portfolios constructed based on corporate eco-efficiency scores over the period 1995-2003. Their findings reveal that environmental criteria can substantially enhance the performance of stock portfolios. The high-ranked portfolio outperforms the low-ranked portfolio, and the positive difference between them cannot be explained by changes in market sensitivity, investment style or industry bias even in the presence of transaction costs. Likewise, Eccles et al. (2014) and Mollet et al. (2013) sustain that a portfolio constructed with “High Sustainability” outperforms the market and “Innovators” firms, outperform their matched non-SRI sample4.

Further studies account for multi SRI dimensions and strongly support that the impact of each SRI dimension should be examined separately, since not all dimensions deliver positive abnormal performance. Even so, there is no consensus on which dimension or screen approach delivers a higher performance. That is the case of Brammer (2006) who uses indicators from Ethical Investment Research Service and three other studies that have used KLD’s SR indicators for different periods of time (Kempf and Osthoff, 2007; Statman and Glushkov, 2009 and Galema et al., 2008).

Analysing employment, environment and community indicators for UK firms, Brammer (2006) find that high scoring firms perform worse than non-scoring firms. Also, positive returns are weakly associated with firms that scoring high in employment

4 Eccles et al. (2014) cautiously selected a portfolio from US “High Sustainability” firms from Asset4 and a matched sample of “Low Sustainability” firms and compared their performance. They constructed an equally-weighted index of all Sustainability Policies using Asset4 scores for 675 companies. For the top quartile firms, they investigated the historical origins of the policies conducting interviews, reading published reports and visiting firms’ websites. In the end, their “High Sustainability” portfolio was composed of 90 firms, which historical evidence had proved that these firms adopted a substantial number of these policies in the beginning of 1990s. Between 1993-2010, both portfolios outperform the markets but “High Sustainability” portfolio significantly outperforms the “Low Sustainability” ones. Mollet et al. (2013) studied the European “innovators” firms from Zurich Cantonal Bank(ZKB) and this firms also outperformed the market.

22 dimension, while negative returns are associated with environmental and community responsible firms.

Kempf and Osthoff (2007) test multi SRI dimensions as well, but they also test different screening approaches and cut-offs for the 1995-2003 period. Contrary to negative screening, the positive and the Best-in-Class screening produces abnormal returns following a Long-Short strategy for both equally and value-weighted portfolios. They concluded that the highest abnormal returns can be achieved by adopting Best-in-Class screening, when combining different ESG dimensions simultaneously and restricting the portfolios to stocks with the highest scores. The evidence of abnormal returns holds even after accounting for transaction costs.

The study of Statman and Glushkov (2009) analysed portfolios based on different SR characteristics from 1992 to 2007. Their dataset distinguishes them from the study conducted by Kempf and Osthoff (2007), because they excluded firms with no strength or weakness indicators. They sustain that a Best-in-Class equally weighted high-ranked portfolio can outperform a low-ranked portfolio when incorporating characteristics such as community involvement, employee relations or overall performance. The value-weighted portfolios also display positive abnormal returns in relation to employee relations and overall performance. It is important to point out that the overall outperformance appears to occur during the subperiod 1992-1999. Moreover, they found evidence that the exclusion of shunned companies might generate disadvantages that can offset the advantages of investing in companies with high ESG scores.

The third study using KLD data is Galema et al. (2008). Over the 1992-2006 period, they analysed SRI portfolios testing them in a General Methods of Moments system, a system that allows the errors of equations to be correlated. In this context only the equally-weighted community portfolio outperforms the market at a 10% significant level. On the other hand, using value-weighted portfolios but at the same significance level, only the employee relations dimension recorded positive abnormal returns.

However, neither Mollet and Ziegler (2014) who analysed three portfolios composed of European and US “sustainability leaders” firms from Morgan Stanley

23 Capital International (MSCI) and ZKB databases, nor Halbritter and Dorfleitner (2015) who study SRI dimensions independently using three different sources of data, find that high and low scoring portfolios perform differently even using a Best-in-Class approach.

It is important to notice that all the studies mentioned above agree that the Carhart (1997) four-factor model is the most appropriate model to assess portfolio performance. In fact, because they control for common investment styles, multifactor models play an important role when assessing performance.

2.4 Investing in SRI: “the learning hypothesis”

Kempf and Osthoff (2007) try to understand whether the positive relationship between ESG criteria and abnormal returns result from a temporary mispricing in the market or not. However due to problems in the sample size, their outputs were not significant.

From the 1990s until the beginning of the 2000s, we are able to find several studies that give support to the benefit of investing in SRI portfolios. Although, more recent studies report a decline in the positive abnormal returns of SRI portfolios (Derwall et al., 2011; Bebchuk et al., 2013; Borgers et al., 2013 and Halbritter and Dorfleitner, 2015). These findings are consistent with “the learning hypothesis” presented by Bebchuk et al. (2013), which states that investors gradually acknowledge the differences between SR firms and non-SR firms. Once they fully incorporate that information, stocks are correctly priced and the advantage of earning abnormal returns for SRI disappears.

Derwall et al. (2011) found that opportunities for different types of SR investors coexist in the short-term, but for those that seek profit the opportunities fade in the long-term. Analysing two distinct portfolios between 1992 to 2008 using KLD data, one scoring high in employee relations and the other in controversial activities, only the controversial portfolio maintains a stable positive and significant performance during all subperiods. The portfolio rated high in employee relation showed, during the subperiod 1992-2006 and 1992-2008, a much lower and insignificant alpha.

As mentioned above, an increasing ESG awareness among investors, over time, may result in a decreasing abnormal positive performance for SRI due to learning effects

24 in capital markets. With the purpose of testing this learning hypothesis, Borgers et al. (2013) built a stakeholder-relation index and used three complementary methods: a portfolio approach, an event study around earnings announcements and an analysis of errors in analysts’ forecasts. All the methods confirmed that errors in expectations due to lack of awareness existed during 1992-2004 but did not persisted during 2004-2009. The positive abnormal performance and its statistical significance decreased in most of the high-rated portfolios after 2004. Similarly, Bebchuk et al. (2013) reach the same conclusions using Governance indices based on Investor Responsibility Research Center data. They reported positive abnormal returns between 1990 and 1999 but these positive abnormal performances became neutral in the subperiod of 2000-2008. Nevertheless, both studies revealed that these indices are important tools for investors, researchers and governance policymakers, since their relationship with firm value, operating performance, and profit continued to persist overtime.

Studies mentioned above used different datasets and, therefore, the event of “learning” was able to be captured, albeit with small variations, in different subperiods. The comparison between different data sources of ESG scores carried out by Halbritter and Dorfleitner (2015), does not find significant differences in the performance of high and low-ranked US SRI portfolios. These results hold even when the Best-in-Class strategy is used. However, when the dataset is divided into subperiods their results are similar to those reported by the three previously mentioned studies. The positive abnormal returns of equally weighted portfolios from KLD database prevailed during 1991-2001 but declined in the following years. The alphas based on the other data sources revealed similar results, after the 2002-2006 period, they converge to zero.

2.5 SRI in Recession Periods

So, why does SRI demand continue to increase if they no longer generate more positive returns? Although “values-driven” investors are willing to quit financial wealth in order to have investments that reflect their convictions, “profit-seeking” investors do not. Nofsinger and Varma (2014) suggest that the reason why SRI is in high demand is possibly because investors want to minimize their downside risk and companies with good Corporate Social Responsibility have characteristics that makes them less risky in

25 recession periods. In fact, the literature provides evidence that firms with strong Corporate Social Responsibility activities reduce their litigation (Koh et al., 2014), idiosyncratic (Godfrey et al., 2009; Ghoul et al., 2011; Bouslah et al., 2013) and stock-price crash risks (Kim et al., 2014). Moreover, Bollen (2007) and Benson and Humphrey (2007) found that SR funds’ flows are less sensitive to past negative returns than flows of conventional funds. Thus, SR funds volatility is lower than conventional funds volatility which might explain the fact that they perform better in bad times.

To understand this issue better, it is important to study the performance accounting for different market conditions. The majority of literature that investigates the performance of SR synthetic portfolios uses unconditional models to assess performance, assuming that risk and return are constant over time. However, it is a well-known fact that risk and return are not linear over time. In this regard, there are several studies that evaluate performance, controlling for different market conditions. Moskowitz (2000), Kosowski (2011) and Glode(2011), suggest that assessing performance through unconditional models, may understate active managers’ abilities. They assess financial performance during periods of recession and the results show conventional equity mutual funds performing better in recession periods.

In respect to SRI, researchers have been reporting a positive relationship between fund financial performance and recession periods. Although Nofsinger and Varma (2014) found that, in general, conventional funds outperform the SRI funds, in periods of crisis SRI funds outperform the conventional ones. They also conclude that the positive alphas during the periods of crisis are associated with the positive screening and ESG criteria. On the contrary, negative screening and criteria that focus on religion or controversial activities lead funds to perform poorly during crisis periods. Similar results are reported by Henke (2016) in relation to SRI bond funds. However, in this case, the most successful strategy during the period of crisis is the exclusion of bond issuers with low ESG scores from the bond mutual funds, instead of the inclusion of bonds with higher ESG scores.

Additionally, Silva and Cortez (2016) analyse and compare the performance of certified green funds, uncertified green funds and other SR funds. Although they find that all US funds perform equally, green funds outperform the SRI funds in periods of

26 crises. Muñoz et al. (2014) evidences also shows that SR funds perform better in crisis periods, outperforming their conventional peers.

To the best of my knowledge, Carvalho and Areal (2016) are the only ones studying synthetic portfolio performance during different market states. They found that companies from the “100 Best Companies to Work for in America” list, during a market crisis, sustain their performance and, systematic risk and value, and the top companies continue to outperform the market.

It is important to point out that when we are evaluating the performance of SRI across different market conditions, the choice of the methodology used to define the alternative market conditions may be critical, and the results of Areal et al. (2013) support this. On the one hand, when defining market regimes based on market volatility, the authors find that SRI mutual funds underperform during expansion periods and slightly outperform during recession periods. On the other hand, when using NBER business cycles, the financial performance of SRI does not change across different market conditions.

27

3.Methodology and Dataset

This section describes the methodology implemented and the dataset used in the empirical tests. Firstly, how ESG portfolios are constructed is explained. Following, the unconditional models implemented to assess portfolio performance is described. Then, market states are defined according to NBER business cycles and time-varying models are presented. The final part of this section describes the ESG scores used to construct the portfolios and the required data to assess the financial performance of ESG portfolios.

3.1 ESG Portfolio Construction

One of the most common approaches in literature to analyse the effects of ESG criteria on portfolio performance, is the construction of synthetic ESG portfolios. As described by Halbritter and Dorfleitner (2015), this approach enables the aggregation of a considerable amount of panel data in a single time-series dimension. This allows the application of basic asset pricing models and it provides a straightforward trading strategy for investors to exploit the relationship between ESG scores and the financial performance. Also, as was previously stated, construction of synthetic portfolios based on ESG scores to investigate the performance of SRI overcomes some limitations associated with assessment of SRI performance based on SRI mutual funds. Therefore, this section follows Kempf and Osthoff (2007), Statman and Glushkov (2009) and Halbritter and Dorfleitner (2015).

Each month t from 2002 to 2017, two distinct equally-weighted portfolios for each ESG dimension are constructed: High portfolios and Low portfolios. In month t-1 firms are ranked by their ESG scores. The portfolios are formed at the beginning of month t and held until the end of month t. The 20% highest (lowest) scoring firms are assigned accordingly to each dimension to the high (low) portfolio. Portfolios are adjusted in a monthly basis.

The main focus is to analyse the impact of the ESG criteria on the financial performance, and to accomplish that, a Long-Short strategy, which consists of holding

28 the High portfolio in a long position and the low portfolio in a short position, is followed. Then, its performance is evaluated.

3.2 Performance Measurement

The simplest performance measure used in the literature is the Jensen’s (1968) alpha in the context of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), a one-factor model that only accounts for the excess return of the market portfolio. However, this model has some limitations related to the CAPM inefficiencies (e.g. Roll, 1977). To overcome such limitations, Fama and French (1993) proposed the three-factor model, adding value and size factors to the one-factor model. Later, Carhart (1997) made some improvements adding the momentum factor of Jegadeesh and Titman’s (1993) suggesting that a four-factor model displays more explanatory power than its predecessors. The Carhart (1997) four-factor model is probably the most commonly used model in finance literature to assess portfolio performance, including the performance of synthetic SRI portfolios (e.g. Kempf and Osthoff, 2007; Derwall et al., 2005; Borgers et al., 2013). Therefore, the performance of the ESG portfolios is initially assessed using the Carhart (1997) four-factor model:

𝑅𝑖,𝑡− 𝑅𝑓,𝑡 = 𝛼𝑖 + 𝛽1,𝑖(𝑅𝑚,𝑡− 𝑅𝑓,𝑡) + 𝛽2,𝑖𝑆𝑀𝐵𝑡+ 𝛽3,𝑖𝐻𝑀𝐿𝑡+ 𝛽4,𝑖𝑀𝑂𝑀𝑡 + 𝜀𝑖,𝑡

(1)

where 𝑅𝑖,𝑡 is the return on the portfolio 𝑖 in period 𝑡; 𝑅𝑓,𝑡 is the risk-free rate; 𝑅𝑚,𝑡 is

the return of the market portfolio; 𝑆𝑀𝐵𝑡 is the return difference between a small and a

large capitalisation portfolio in month t; 𝐻𝑀𝐿𝑡 the return difference between a

portfolio of high book-to-market stocks and a portfolio of low book-to-market stocks and 𝑀𝑂𝑀𝑡 is the return difference between the portfolio of the past 12-month return

winners and losers. The 𝛽𝑠 measure the risk in respect to each factor and the Jensen’s alpha, 𝛼𝑖 , measures the average abnormal return of an ESG portfolio in excess of the

return on the market portfolio.

Recently, Fama and French (2015) suggested an improved version of the Fama and French (1993) three-factor model that adds profitability and investment factors: the

29 five-factor model. These authors claim that investors should choose the five-factor model if they are interested in portfolios that tilt towards value, size, profitability and investment premium. Since this is a quite recent model, it is of interest to test it to assess the performance of ESG portfolios. The model is summarized by the following equation:

𝑅𝑖,𝑡− 𝑅𝑓,𝑡 = 𝛼𝑖 + 𝛽1,𝑖(𝑅𝑚,𝑡− 𝑅𝑓,𝑡) + 𝛽2,𝑖𝑆𝑀𝐵𝑡+ 𝛽3,𝑖𝐻𝑀𝐿𝑡+ 𝛽4,𝑖𝑅𝑀𝑊𝑡

+ 𝛽5,𝑖𝐶𝑀𝐴𝑡+ 𝜀𝑖,𝑡

(2)

where 𝑅𝑀𝑊𝑡 is the difference between the returns on diversified portfolios of stocks

with robust and weak profitability and 𝐶𝑀𝐴𝑡 is the difference between the returns on

diversified portfolios of the stocks of low and high investment firms.

3.3 Recession Periods

Both models presented above assume that portfolio performance and risk are constant across different market conditions and may understate the ESG portfolio performance. Some authors define market states based on the identification of periods of high/low volatility in the stock market (e.g. Areal et al., 2013; Nofsinger and Varma, 2014). Other authors (Moskowitz, 2000; Kosowski, 2011; Areal et al., 2013 and Henke, 2016) distinguish between market states, using US National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) business cycles. NBER defines a recession when there is a significant fall in the economic activity spread across the economy, that lasts for more than few months5.

In this dissertation, the ESG portfolios performance is assessed across the different NBER business cycles of recession and expansion. Figure 2 shows the monthly evolution of the market portfolio from January 2002 to June 2017. The grey area in the graphs identify the period of recession, and white areas correspond to the periods of expansion according to NBER classification of business cycles. The only period of recession identified in the graph begins in January 2008 and ends in June 2009,

5According to the last announcement from the NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee from September 20 of 2010, the significant

fall in the economic activity is visible not only in the GDP, but also in real income, employment, industrial production and wholesale-retail sales.

30 corresponding to the latest global financial crisis and an accentuated decrease in the stock market.

Figure 3, presented next, shows the monthly excess returns of the market portfolio across the different NBER business cycles of recession and expansion. As expected, the recession period represented in the graph is associated with high volatility. -18 -14 -10 -6 -2 2 6 10 14 Jan -02 Oct -02 Ju l-03 Apr -04 Jan -05 Oct -05 Ju l-06 Apr -07 Jan -08 Oct -08 Ju l-09 Apr -10 Jan -11 Oct -11 Ju l-12 Apr -13 Jan -14 Oct -14 Ju l-15 Apr -16 Jan -17 EXCE SS R ET URN S DATE -40 -20 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 Jan -02 O ct -02 Ju l-03 A p r-04 Jan -05 O ct -05 Ju l-06 A p r-07 Jan -08 O ct -08 Ju l-09 A p r-10 Jan -11 O ct -11 Ju l-12 A p r-13 Jan -14 O ct -14 Ju l-15 A p r-16 Jan -17 K.R.F. Ma rk et Po rtfolio DATE

Figure 3- Monthly excess returns of the US Market portfolio, available on the Professor Kenneth French webpage, over the period of January 2002 to September 2017.

Figure 2- Monthly evolution of the US Market Portfolio, available on the Professor Kenneth French webpage, over the period of January 2002 to September 2017.

31 Similarly, to Areal et al. (2013) and Carvalho and Areal (2016), to assess portfolio performance across periods of expansion and recession a dummy variable, 𝐷𝑡, is added

to the four (equation 3) and five-factor (equation 4) models, based on the NBER business cycle information:

𝑅𝑖,𝑡− 𝑅𝑓,𝑡 = 𝛼𝑖 + 𝛼𝑟𝑒𝑐,𝑖𝐷𝑡+ 𝛽1,𝑖(𝑅𝑚,𝑡− 𝑅𝑓,𝑡) + 𝛽1𝑟𝑒𝑐,𝑖(𝑅𝑚,𝑡− 𝑅𝑓,𝑡)𝐷𝑡

+ 𝛽2,𝑖𝑆𝑀𝐵𝑡+ 𝛽2𝑟𝑒𝑐,𝑖𝑆𝑀𝐵𝑡𝐷𝑡+ 𝛽3,𝑖𝐻𝑀𝐿𝑡+ 𝛽3𝑟𝑒𝑐,𝑖𝐻𝑀𝐿𝑡𝐷𝑡

+ 𝛽4,𝑖𝑀𝑂𝑀𝑡+ 𝛽4𝑟𝑒𝑐,𝑖𝑀𝑂𝑀𝑡𝐷𝑡+ 𝜀𝑖,𝑡

(3)

For both models, the dummy variable assumes a value of 0 in periods of expansion, and a value of 1 in periods of recession. It allows us to analyse differences across market conditions, not only with respect to the alphas but also to the risk factors.

3.4. Dataset Description

ESG database, from Thomson Reuters DataStream is used to construct the ESG portfolios. Its total universe comprises more than 3800 public firms worldwide with a minimum of 4 years of history since 2002. Firms are scoring using more than 250 performance indicators calculated from more than 750 data points, which covers 4 different performance dimensions: Environmental, Social, Corporate Governance and Economic. All firms are benchmarked against the rest of the firms in the database.

From ASSET4, the aggregated scores for the ENV, SOC and GOV dimensions are extracted. The ENV score measures the impact of a firm’s activities in the ecosystems and how well a company uses its management practices to avoid environmental risks and use environmental opportunities to generate long-term shareholder value. The SOC score measures the capacity of a company to generate trust and loyalty with

𝑅𝑖,𝑡 − 𝑅𝑓,𝑡 = 𝛼𝑖+ 𝛼𝑟𝑒𝑐,𝑖𝐷𝑡+ 𝛽1,𝑖(𝑅𝑚,𝑡 − 𝑅𝑓,𝑡) + 𝛽1𝑟𝑒𝑐,𝑖(𝑅𝑚,𝑡− 𝑅𝑓,𝑡)𝐷𝑡

+ 𝛽2,𝑖𝑆𝑀𝐵𝑡+ 𝛽2𝑟𝑒𝑐,𝑖𝑆𝑀𝐵𝑡𝐷𝑡+ 𝛽3,𝑖𝐻𝑀𝐿𝑡+ 𝛽3𝑟𝑒𝑐,𝑖𝐻𝑀𝐿𝑡𝐷𝑡

+ 𝛽4,𝑖𝑅𝑀𝑊𝑡+ 𝛽4𝑟𝑒𝑐,𝑖𝑅𝑀𝑊𝑡𝐷𝑡+ 𝛽5,𝑖𝐶𝑀𝐴𝑡

+ 𝛽5𝑟𝑒𝑐,𝑖𝐶𝑀𝐴𝑡𝐷𝑡+𝜀𝑖,𝑡

32 stakeholders through its management practices to create shareholder value. The GOV score evaluates how well a company manages its mechanism of incentives, which allies its rights and responsibilities with those of the board members and CEOs, ensuring that they act in the best interest to create long term shareholders’ value. The Economic dimension has not been considered since its score reflects the company’s overall financial health, which does not fit in the purpose of this dissertation.

Additionally, with the main purpose of analysing the performance of a SRI portfolio constructed based on a score that reflects simultaneously the three dimensions, an overall ESG score6 is computed by taking the average of the

Environmental, Social and Governance score.

As the focus of this study is the financial performance of ESG portfolios, the ESG data from ASSET4 was merged with the Thomson Reuters DataStream financial data. For every company, the monthly total return index was obtained to calculate monthly discrete returns. As a result, the monthly sample from January 2002 to September 20177, is comprised of 2355 US public firms, where scores and total return indexes were

available.

In the contexts of the Carhart (1997) four-factor and the Fama and French (2015) five-factor models, all the factors were collected from the data library of Professor Kenneth R. French’s website8, including the excess market return. Consequently, the

market portfolio is the value-weighted return of all CRSP firms incorporated in the US and listed in the NYSE, AMEX and NASDAQ.

Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics for the returns of the ESG portfolios and the market portfolio for a period of 188 months. All portfolios present mean returns higher than the market portfolio, but the Low rated portfolios present higher values than the High rated portfolios. As expected in the financial series of returns, the portfolio returns present a negative skewness and excess kurtosis, thus none of the portfolios present the normal distribution of the returns. The Jarque-Bera test, that confirms the non-normality of the portfolio returns distribution was also performed.

6 ASSET4 provides an overall ESG score but it is based on the four dimensions which is inappropriate for this study.

7 The last time data were extracted (November 2017), the ASSET4 database was not updated and some months from 2017 didn’t

have enough data to construct portfolios. To avoid biased estimations, the existing data from October 2017 forward, was excluded from the empirical procedures.

33 Table 1- Descriptive statistics of portfolios’ returns

Portfolio Max. Min. Mean Median Std.

Dev. Skewness Kurtosis JB Prob. ENV High 0.137 -0.170 0.009 0.014 0.045 -0.454 4.365 0.000 Low 0.135 -0.167 0.010 0.016 0.048 -0.416 3.680 0.011 SOC High 0.123 -0.174 0.009 0.013 0.042 -0.545 4.761 0.000 Low 0.144 -0.180 0.012 0.018 0.049 -0.485 4.002 0.000 GOV High 0.132 -0.177 0.009 0.013 0.046 -0.553 4.480 0.000 Low 0.162 -0.187 0.013 0.020 0.049 -0.468 4.245 0.000 ESG High 0.123 -0.175 0.009 0.013 0.043 -0.503 4.614 0.000 Low 0.142 -0.182 0.013 0.018 0.048 -0.515 4.077 0.000 MKT 0.114 -0.172 0.007 0.012 0.041 -0.693 4.628 0.000

This table presents the descriptive statistics of portfolios returns constructed based on the positive screen approach. The high (low) portfolios are formed with the 20% highest (lowest) rated companies according to each ESG score. The maximum, minimum, mean, median, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, and the Jarque-Bera probability test of portfolios’ returns for each dimension are presented.

34

4. Results

In this section, the obtained results concerning the performance of SR portfolios are reported and discussed9. First, the performance of High, Low and Long-Short

portfolios assessed using the four-factor and five-factor models are displayed. Next, several robustness checks are implemented with respect to the weighted scheme, screen approach, different cut-offs and the exclusion of financial firms. Finally, the performance results of all portfolios assessed with models that allow performance and risk to vary according to expansion versus recession periods is presented.

4.1 Performance Evaluation

Table 2 presents the performance estimates of the Carhart (1997) four-factor model for High, Low and Long-Short equally weighted portfolios for each ESG dimension. In terms of financial performance, the results show that Low and High rated portfolios outperform the market with a significance level of 1% and 5%, except for the Low rated portfolio of ENV dimension. However, Low rated portfolios display higher alphas than High rated portfolios. Consequently, alphas of Long-Short portfolios are negative and statistically significant at 1% and 5% level for GOV and ESG dimension. Moreover, High and Low rated portfolios constructed in the basis of ENV and SOC dimensions do not perform differently from each other. Overall, it is possible to conclude, that there is no advantage to investing in a portfolio composed by High rated companies instead of a Low rated one as the Long-Short strategy based on ESG scores, does not provide positive abnormal returns.

The risk factors seem to explain well the excess returns of all equally weighted portfolios, since its loadings are, in general, statistically significant at a 5% level with the exception of the momentum factor for Low rated portfolios. Nevertheless, ENV and ESG High rated portfolios are more exposed to market risk than Low rated portfolios while the contrary is true for SOC and GOV dimensions. In every dimension, portfolios with

9Tests are performed to analyse the presence of heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation. The White (1980) adjustment for the

presence of heteroscedasticity and the Newey West (1987) adjustment for the simultaneous presence of heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation are used.

35 high scoring firms are less exposed to size and book-to-market risk, which means that High rated portfolios are less exposed to small capitalization stocks and to value firms than Low rated portfolios.

Moreover, the momentum factor presents negative and statistically significant coefficients at 1% and 5% significance level, indicating that portfolios are composed on average by firms with poor past performance. These results are supported by the results of Derwall et al. (2005), in which his portfolio composed by companies ranking high in eco-efficiency also presents a negative momentum coefficient.

Table 2 - Portfolio performance estimates- Carhart (1997) four-factor model

Portfolio α Market SMB HML MOM R2

ENV High 0.002*** 0.995*** 0.119*** 0.102*** -0.045*** 0.960 Low 0.002* 0.941*** 0.401*** 0.260*** -0.041 0.908 Long-Short -0.000 0.054 -0.282*** -0.158*** -0.004 0.186 SOC High 0.002*** 0.962*** 0.081*** 0.052** -0.035** 0.961 Low 0.004*** 0.993*** 0.457*** 0.172*** 0.006 0.928 Long-Short -0.002 -0.030 -0.377*** -0.120*** -0.041 0.353 GOV High 0.002** 0.998*** 0.187*** 0.089*** -0.058*** 0.957 Low 0.005*** 1.000*** 0.425*** 0.156*** -0.039* 0.941 Long-Short -0.003*** -0.002 -0.239*** -0.066 -0.019 0.186 ESG High 0.002*** 0.967*** 0.100*** 0.075*** -0.050*** 0.963 Low 0.004*** 0.962*** 0.462*** 0.188*** -0.011 0.926 Long-Short -0.002** 0.004 -0.362*** -0.113** -0.038 0.308

This table presents the results of the Carhart (1997) four-factor model (Equation 1) from January 2002 to September 2017 on a monthly basis. The R2s, alphas, and factor loadings concerning market, size,

value and momentum are reported. The high (low) portfolios are formed with the 20% highest (lowest) rated companies according to each ESG score. The Long-Short portfolio trades the High portfolio long while the Low portfolio is traded short. The portfolios are equally weighted. Standard errors were estimated using White (1980) or Newey-West (1987) adjustment. ∗∗∗, ∗∗, and ∗ indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level.

Table 3 reports alphas and risk factors concerning the five-factor model for all portfolios. Although the R2s have slightly increased, it can be said that the four and the

five-factor model have a very similar explanatory power. The main difference between the results of the two models is the fact that alphas of High rated portfolios are not

36 statistically significant at a 5% level. A possible explanation for that might be the absence of the MOM factor control, since High rated portfolios show significant exposure to this factor. Comparatively to the four-factor model, the five-factor model, also displays a negative and statistically significant Long-Short alpha for the SOC dimension, in addition to GOV and ESG dimensions.

Table 3- Portfolio performance estimates- Fama and French (2015) five-factor model

Portfolio α Market SMB HML RMW CMA R2

ENV High 0.001 1.042*** 0.128*** 0.080** 0.104** 0.061 0.960 Low 0.002* 0.935*** 0.384*** 0.233*** -0.088 -0.028 0.909 Long-Short -0.001 0.107*** -0.257*** -0.152*** 0.192*** 0.089 0.220 SOC High 0.001* 1.014*** 0.090*** 0.019 0.134*** 0.103** 0.964 Low 0.004*** 0.988*** 0.474*** 0.128*** 0.020 -0.107 0.931 Long-Short -0.002** 0.026 -0.384*** -0.109** 0.114* 0.210*** 0.385 GOV High 0.001 1.040*** 0.185*** 0.065 0.063 0.064 0.996 Low 0.005*** 1.012*** 0.433*** 0.138*** 0.007 -0.114* 0.943 Long-Short -0.004*** 0.028 -0.248*** -0.073* 0.056 0.178*** 0.217 ESG High 0.001* 1.018*** 0.100*** 0.043 0.102*** 0.121*** 0.963 Low 0.004*** 0.967*** 0.483*** 0.149*** 0.032 -0.109 0.930 Long-Short -0.003*** 0.050* -0.383*** -0.106** 0.070 0.229*** 0.348

This table presents the results of the Fama and French (2015) five-factor model (Equation 2) from January 2002 to September 2017 on a monthly basis. The R2s, alphas, and factor loadings concerning market,

size, value, investment and profitability are reported. The high (low) portfolios are formed with the 20% high (low) rated companies according to each ESG score. The Long-Short portfolio trades the High portfolio long while the Low portfolio is traded short. The portfolios are equally weighted. Standard errors were estimated using White (1980) or Newey-West(1987) adjustment. ∗∗∗, ∗∗, and ∗ indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% level.

With respect to the risk factors, High rated portfolios show more exposure to the market risk and less exposure to the size factor than Low rated portfolios, which indicates that High rated portfolios are less exposed to small capitalization stocks than Low rated portfolios. The book-to-market factor loadings have become not statistically significant in most of the High rated portfolios. In fact, Fama and French (2015) explains that “HML is redundant for describing average returns, because average HML return is captured by exposures of HML to other factors” (p.12). Moreover, High rated portfolios in the ENV, SOC and ESG dimension present positive and statistically significant

37 coefficients (at 1% and 5% level) for profitability factor. This indicates that these portfolios are composed by profitable firms. The investment factor coefficients of SOC and ESG Long-Short portfolios are positive at a 1% and 5% level, which means that these portfolios are composed by firms that invest conservatively.

In a first approach, these results are in contrast with authors who argue that the Long-Short strategy, based on ESG criteria, delivers positive returns (Derwall et al., 2005; Kempf and Osthoff, 2007; Statman and Glushkov, 2009; Eccles et al., 2014). Moreover, it is somehow in contrast with those authors who state that no significant return difference exits between firms that scoring High and Low on ESG criteria (Brammer et al., 2006; Halbritter and Dorfleitner, 2015). Although, Halbritter and Dornfleitner (2015) conclude in their study that, between High and Low scoring ESG firms there is no significant return difference, when analysing Asset4 equally-weighted portfolios, they also find the GOV Long-Short portfolio to be delivering negative abnormal returns at a 5% significance level.

4.2 Robustnes checks: weightning scheme, screen approach, different cut-offs and the exclusion of financial firms

Next some robustness checks are implemented to investigate if results still hold. First, to investigate whether the results are dependent on the portfolio weighting scheme, the financial performance of value weighted portfolios constructed based on their Market Value is also measured. The alphas of the value weighted portfolios, measured with the four-factor and five-factor model, are presented in table 4. The performance estimates concerning High and Low rated portfolios can be found in Appendix C and D. To enhance comparison, the alphas of equally weighted portfolios are also displayed. The results are similar for both models. In general, the alphas of High and Low rated value weighted portfolios are economically higher and statistically significant at the 1% level. Also, differences between High and Low rated portfolios increased, and, consequently, value-weighted Long-Short portfolios show more negative and significant alphas at the 1% level, except for ENV dimension. The results of value-weighted scheme strongly support that following a Long-Short strategy does not deliver positive abnormal returns.