Mycology

Twelve years of coccidioidomycosis in Ceará State, Northeast Brazil:

epidemiologic and diagnostic aspects

Rossana de Aguiar Cordeiro

a,b,⁎

, Raimunda Sâmia Nogueira Brilhante

a,

Marcos Fábio Gadelha Rocha

a,c, Silviane Praciano Bandeira

a,b,

Maria Auxiliadora Bezerra Fechine

a, Zoilo Pires de Camargo

d, José Júlio Costa Sidrim

a,ba

Specialized Medical Mycology Center, Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, Ceará

b

Department of Biological Science, State University of Ceará, Fortaleza

c

Postgraduate Program in Veterinary Science, State University of Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil

d

Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Parasitology, Federal University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Received 9 June 2008; accepted 29 September 2008

Abstract

Coccidioidomycosis is an endemic infection in the Americas caused by the dimorphic fungi Coccidioides immitisand Coccidioides posadasii. Although the disease occurs in Brazil in sporadic form, little information about these cases is available. In this study, we summarize the most important clinical, epidemiologic, and diagnostic features of coccidioidomycosis in Ceará State (Northeast Brazil) during the past 12 years. In this period, 19 cases of coccidioidomycosis were diagnosed. All the patients were young males and came from semiarid areas of the state. The majority of cases were associated to armadillo hunting, and pulmonary disease was the most common clinical presentation. In our laboratory, coccidioidomycosis was confirmed by culture, serology, and polymerase chain reaction tests, which together were very suitable for the diagnosis of this disease. Based on our local experience, we believe many cases of this disease are misdiagnosed or not diagnosed in our region. Therefore, some strategies for improvement of diagnosis should be encouraged by local authorities.

© 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Coccidioidomycosis; Diagnosis; Epidemiology; Brazil

1. Introduction

Coccidioidomycosis is a respiratory infection caused by the dimorphic fungiCoccidioides immitisandCoccidioides posadasii(Fisher et al., 2002). The disease is found only in the Western Hemisphere, with well-defined endemic areas in the southwestern United States and northern Mexico (Hector

and Laniado-Laborin, 2005), as well as semiarid areas of

Central and South America, mainly Honduras, Guatemala, Venezuela, Argentina, and Brazil (Cox and Magee, 2004;

Hector and Laniado-Laborin, 2005).

Although coccidioidomycosis occurs in many countries in the Americas, Coccidioides spp. has a striking

geo-graphic distribution: C. immitis is limited to the San Joaquin Valley in California, whereas C. posadasiioccurs throughout the United States and Central and South America (Fisher et al., 2002).

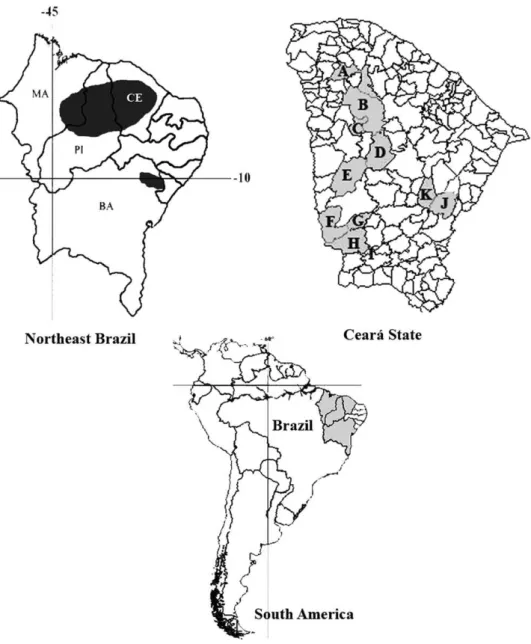

In Brazil, the 1st case of coccidioidomycosis occurred in the late 1970s, and since then, other cases have been registered in 4 states of the semiarid northeast region: Maranhão, Piauí, Ceará, and Bahia (Cordeiro et al.,

2006a, 2006b) (Fig. 1). However, the real incidence of

coccidioidomycosis in Brazil is unknown probably because of 4 main reasons. First, it is not a reportable disease; second, it may be misdiagnosed as tuberculosis, which is very endemic in Brazil (Cordeiro et al., 2006a,

2006b); and third, there is a high percentage of

asymptomatic patients (Saubolle et al., 2007). Finally, the lack of well-structured laboratories in endemic areas may account for its low reporting incidence (Cordeiro et al., 2006a, 2006b) (Fig. 1).

Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 66 (2010) 65–72

www.elsevier.com/locate/diagmicrobio

⁎Corresponding author. Department of Biological Science, State University of Ceará, Campus do Itaperi, Av Paranjana, 1700, Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. Tel.: +55-085-3366-8319; fax: +55-085-3366-8319.

E-mail address:ross@uece.br(R. de Aguiar Cordeiro).

In this article, we summarize the most important clinical– epidemiologic data on coccidioidomycosis cases occurring in Ceará State (Northeast Brazil) from 1995 to 2007 and describe our approach to laboratory diagnosis of the disease.

1.1. The study

From May 1995 to September 2007, clinical samples from 14 patients presenting nonspecific respiratory symp-toms were investigated for coccidioidomycosis at the Specialized Medical Mycology Center (CEMM) of Federal University of Ceará, a reference laboratory for mycological diagnosis in Brazil. After laboratory confirmation, the patients were selected for investigation of the main clinical–epidemiologic data, such as sex, age, origin, and

clinical features. Collected data were compared with other cases of coccidioidomycosis that occurred in Ceará State identified through a search in the Medline, PubMed, and SciELO electronic databases using the keywords“ coccidioi-domycosis”and“Brazil”.

1.2. Mycological diagnosis

Sputum and/or bronchoalveolar lavage (n = 13) and pericardial liquid (n= 1) wet mounts were prepared in 10% KOH and examined under a light microscope (40×). Clinical specimens were also inoculated on Sabouraud glucose agar (SGA) (Difco Laboratories, Detriot, MI), SGA with 0.5% chloramphenicol, and Mycosel agar slants (Sanofi, France) and incubated at 28 °C until visualization of fungal colonies. Fig. 1. Maps showing occurrence of coccidioidomycosis in Brazil. The disease is limited to the Northeast region, with endemic areas in the stats of Maranhão (MA), Piauí (PI), Ceará (CE), and Bahia (BA). In Ceará, cases came from 10 municipalities: Sobral (A), Santa Quitéria (B), Catunda (C), Boa Viagem (D), Independência (E), Parambu (F), Arneiroz (G), Aiuaba (H), Jaguaribe (J), and Solonópole (K). According toSidrim et al. (1997), another case may have occurred in Antonina do Norte (I).

Slides from primary cultures suggestive ofCoccidioidesspp. were prepared in lactophenol cotton blue stain and examined under a light microscope, as described by Cordeiro et al. (2006a, 2006b). The positive cultures were stored in 0.9% saline at 4 °C and on potato agar at −80 °C for further

analysis. All mycological procedures were performed inside a microbiologic safety cabinet in our BL3 laboratory.

1.3. Immunodiagnosis

Sera (n= 12) and pericardial liquid (n= 1) samples were evaluated qualitatively for specific coccidioidal antibodies by immunodiffusion test with Coccidioides IDCF antigen (Immy Immunodiagnostics, EUA), according to the manu-facturer's instructions. Only 2 samples came from con-valescent patient; the remaining was obtained from individuals with acute disease. All reactions were carried out with Coccidioides serum (anti-IDCF, Immy Immuno-diagnostics, Norman, OK) as positive control. To detect false-positive reactions, we also tested all samples by immunodiffusion with Histoplasma ID Antigen H&M (Immy Immunodiagnostics, EUA), according to the manu-facturer's instructions.

Some of these samples were also tested forC. posadasii antibodies with homemade crude antigens prepared in our laboratory. In brief, for antigen extraction, a strain of C. posadasii from our culture collection (CEMM 01-6-085), maintained in the mycelial phase, was grown in a 2% glucose–1% yeast extract broth for 30 days at 30 °C. After this period, the culture was killed with 0.2 g/L thimerosal (ethylmercurithosalicylic acid sodium salt; Synth, Brazil), and the supernatant was collected following filtration in Whatman 42 paper. For protein precipitation, the filtrate was treated with solid ammonium sulfate (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO), until reaching 90% saturation. The mixture was kept at 4 °C for 24 h and then precipitated proteins were recovered by centrifugation at 10 000 × g for 30 min and dialyzed exhaustively against distilled water in a dialysis membrane with 10-kDa molecular weight cutoff. The dialysate was stored at−20 °C and used for immunodiffusion

tests, which were carried out as described above. To evaluate the specificity of this crude antigen extract, we tested sera from uninfected individuals and from patients infected by Histoplasma capsulatum, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, and Aspergillus fumigatus by immunodiffusion using the same methodology described above.

1.4. Molecular identification/detection

Identification of C. posadasii strains isolated in our laboratory (n= 14) was also confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reactions (Bialek et al., 2004; Umeyama et al., 2006). Genomic fungal DNA from both stored and/or primary cultures were extracted according to Burt et al. (1995). Molecular diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis was also done after a PCR assay to detect the Ag2/PRA sequence directly in 6 sputum and/or bronchoalveolar samples

(Cordeiro et al., 2007). C posadasii strain (CEMM

01-6-085) and Candida krusei (ATCC 6528) were included as positive and negative amplification controls, respectively.

2. Results

From 1995 to 2007, 19 coccidioidomycosis cases occurred in Ceará State (Northeast Brazil). During this period, clinical samples from 14 patients were examined at CEMM for laboratorial diagnosis, and another 5 cases were found after literature review (Costa et al., 2001; Sidrim et al.,

1997; Silva et al., 1999). Diagnosis of 3 of them was

achieved only by way of clinical and epidemiologic data (Sidrim et al., 1997).

Coccidioidomycosis occurred among male patients aged between 13 and 43 years old who lived and/or worked in semiarid areas of the state. The patients presented acute symptoms, such as fever, nonproductive cough, pleuritic pain, and dyspnea after armadillo hunting, except 1 patient with disseminated disease who had never hunted burrowing animals before. In this case, the patient was admitted to a local hospital suffering from fever, chest pains, chills, persistent productive cough, and weight loss, which secondarily progressed to congestive heart failure. Further diagnostic examinations revealed that anti-HIV antibodies were negative in this patient. Information about the date, origin (municipality), main clinical features, treatment, and initial diagnosis of each case are summarized inTable 1.

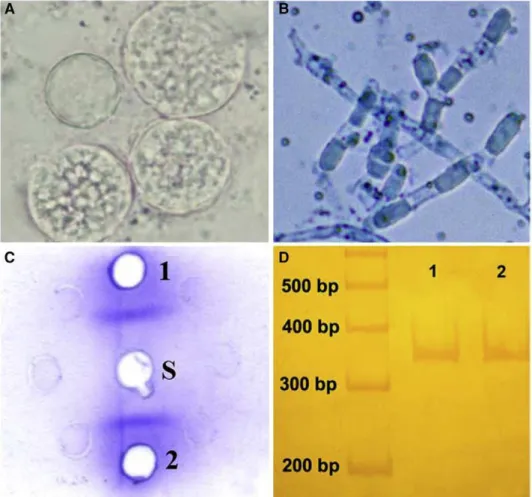

Regarding laboratorial procedures carried out in our laboratory, direct microscopy examination were positive only in samples from those patients with pulmonary coccidioidomycosis (n = 13) (Fig. 2A). The patient with disseminated infection had negative direct examination of his pericardial fluid. At our laboratory, diagnosis of pulmonary and disseminated forms was also confirmed by culture (n= 14), serology (n= 13), and/or PCR reactions (n= 14). Cultures of clinical specimens proved to be positive for all 14 patients. Mycological analysis revealed cottony or velvety colonies, with white, cream, or gray mycelia. Numerous characteristic Coccidioides-like barrel-shaped arthroconidia, alternating with empty disjunctor cells, were observed (Fig. 2B) under microscopic examination.

Serologic diagnosis of 13 patients was done by immunodiffusion tests with commercial Coccidioides IDCF antigen and, in some cases, also with a homemade antigen. Each sera sample gave a single precipitin band on agarose gel with coccidioidal antigens (Fig. 2C) and did not react withHistoplasmaID antigen. BothCoccidioidesIDCF and experimental coccidioidal antigens gave positive reac-tions with control serum.

Molecular identification of primary and/or stored cultures obtained from 14 patients was achieved by PCR reactions. Polymerase chain reaction assays for partial Ag2/PRA sequence revealed amplicon of 342 bp, whereas confirma-tory PCR reactions showed a 634-bp sequence indicative of C. posadasii for all samples. Direct detection of Ag2/PRA

Table 1

Summary of general characteristics of all coccidioidomycosis cases occurring in Ceará State (Northeast Brazil) from 1995 to 2007

Case Date Origin Age Clinical features Initial clinical diagnosis Treatment Clinical specimen Primary laboratory diagnostic method Additional laboratory diagnostic method

1a May 1995 Aiuaba 6°34′S 40°07′W

27 Fever, productive cough, headache

Not informed None None Not performed Not performed

2a May 1995 Aiuaba 6°34′S 40°07′W

22 Fever, pleuritic pain, adinamy, nonproductive cough

Not informed None None Not performed Not performed

3a May 1995 Aiuaba

6°34′S 40°07′W

13 Fever, productive cough, pleuritic pain, adinamy

Not informed None None Not performed Not performed

4a May 1995 Aiuaba

6°34′S 40°07′W

19 Fever, nonproductive cough, dyspnea

Pneumonia ITR, AMB Sputum Microscopy,

culture, animal inoculation

PCR (stored culture)

5b February

1999

Independência 5° 23′S 40° 18′W

21 Fever, productive cough, pleuritic pain, dyspnea, headache

Coccidioidomycosis AMB Sputum Microscopy,

animal inoculation

Not performed

6c September 2001

Boa Viagem 5° 07′S 39° 43′W

19 Fever, nonproductive cough, pleuritic pain, dyspnea

Pneumonia AMB Sputum,

lung biopsy Microscopy, histopathology Not performed 7 November 2001 Solonópoles 5°44′S 39°09′W

29 Fever, productive cough, pleuritic pain, joint pain, cutaneous lesions

Not informed AMB, FLU BL Microscopy,

culture, commercial immunodiffusion PCR (stored culture) 8 November 2002 Catunda 4°38′S 40°12′W

24 Fever, chills, nonproductive cough, dyspnea, pleuritic pain Wegener's granulomatosis, septic embolia

AMB, FLU BL Microscopy,

culture, commercial immunodiffusion PCR (stored culture) 9 November 2002 Santa Quitéria 4°19′S 40°09′W

27 Fever, nonproductive cough, dyspnea, anorexia, weigh Paracoccidioidomycosis sarcoidosis, aspergillosis, neoplasia, septic embolia

AMB, FLU Sputum Microscopy, culture, commercial immunodiffusion PCR (stored culture) 10 December 2003 Santa Quitéria 4°19′S 40°09′W

43 Nonproductive cough, joint pain, pleuritic pain Pneumonia, Wegener's granulomatosis

ATB, FLU BL Microscopy,

culture, commercial immunodiffusion PCR (stored culture) 11 December 2003 Solonópoles 5°44′S 39°09′W

32 Fever, nonproductive cough, pleuritic pain, dyspnea

Fungal pneumonia ITR BL Microscopy,

culture, commercial immunodiffusion PCR (stored culture) 12 February 2004 Arneiroz 6°19′S 40°09′W

13 Fever, nonproductive cough

Tuberculosis FLU, AMB,

ITR BL Microscopy, culture, commercial and experimental immunodiffusion tests PCR (primary culture) 13 February 2005 Ibiapina 3°55`S 40°53`W 35 Fever, chest pain, chills, productive cough, weight loss

Miopericarditis FLU PF Culture,

coccidioidal sequence in clinical specimens by PCR was positive in all 6 samples tested (Fig. 2D).

Literature review showed that diagnosis of coccidioido-mycosis in Ceará State has also been performed by way of animal inoculation of clinical specimens (Clemons et al.,

2007; Sidrim et al., 1997; Silva et al., 1999) and

histopathology of lung biopsy (Costa et al., 2001).

3. Discussion

The present study summarizes the clinical–epidemiologic information about 19 coccidioidomycosis cases occurring in Ceará State (Northeast Brazil) from 1995 to 2007. The patients were young males (average age, 24.26 years), living in rural areas, who shared the hobby of hunting armadillos. The single case of disseminated coccidioidomycosis detected in our retrospective study occurred in a

35-year-old man who worked as a seller in endemic areas for coccidioidomycosis situated in the semiarid region of Brazil. The recognition of this case has a great epidemiologic importance because, in our country, coccidioidomycosis has been associated only with hunting armadillos due to the exposure of large amounts of infected aerosols during this activity (Cordeiro et al., 2006a, 2006b; Wanke et al., 1999). We suppose that human migrations across high-risk areas in semiarid regions or frequent exposure to domestic/ambient dust may also be an important factor for catching coccidioidomycosis in Northeast Brazil.

Surprisingly, 5 cases of coccidioidomycosis occurred during the rainy season (from February to April). It is well known that climate conditions have an important impact on coccidioidomycosis incidence (Comrie, 2005), with dry periods being more suitable for infection. Therefore, we suppose that a long incubation period of the disease could Table 1 (continued)

Case Date Origin Age Clinical features Initial clinical diagnosis Treatment Clinical specimen Primary laboratory diagnostic method Additional laboratory diagnostic method 14 December 2006 Sobral 3°41′S 40°29′W

19 Fever, pleuritic pain, nonproductive cough

Coccidioidomycosis FLU BL Microscopy,

culture, commercial and experimental immunodiffusion tests

PCR (BL and primary culture)

15 December

2006

Sobral 3°41′S 40°29′W

33 Fever, pleuritic pain, nonproductive cough, cutaneous lesions

Coccidioidomycosis FLU BL Microscopy,

culture, commercial and experimental immunodiffusion tests

PCR (BL and primary culture)

16 December

2006

Sobral 3°41′S 40°29′W

22 Fever, pleuritic pain, nonproductive cough, dyspnea

Coccidioidomycosis AMB, FLU BL Microscopy,

culture, commercial and experimental immunodiffusion tests

PCR (BL and primary culture)

17 March

2007

Jaguaribe 5°53′S 38°37′W

18 Fever, nonproductive cough, dyspnea, pleuritic pain Pneumonia, coccidioidomycosis

AMB, FLU BL Microscopy,

culture, commercial and experimental immunodiffusion tests

PCR (BL and primary culture)

18 March

2007

Jaguaribe 5°53′S 38°37′W

29 Fever, pleuritic pain,

dyspnea, cough

Coccidioidomycosis AMB, FLU BL Microscopy,

culture, commercial and experimental immunodiffusion tests

PCR (BL and primary culture)

19 September 2007

Parambu 6°12′S 40°41′W

26 Fever, pleuritic pain, nonproductive cough, dyspnea, headache Pneumonia tuberculosis

AMB Sputum Microscopy,

culture, commercial and experimental immunodiffusion tests PCR (sputum and primary culture)

BL = bronchoalveolar lavage; PF = pericardial fluid; AMB = amphotericin B; ITR = itraconazole; FLU = fluconazole.

a

Sidrim et al. (1997).

b

Silva et al. (1999).

c

Costa et al. (2001).

explain the occurrence of coccidioidomycosis during the rainy season in Brazil.

The clinical manifestations of all of the cases presented here were very similar. The most common symptoms were fever, nonproductive cough, pleuritic pain, and dyspnea. These nonspecific symptoms pose a significant challenge to physicians. Depending on the evolution time of the disease, there could be many different diagnoses: acute presentations could resemble bacterial pneumonia or thromboembolism and subacute or chronic evolution could be mistaken for tuberculosis, which is one of the main public health problems in Brazil (Cordeiro et al., 2006a, 2006b). In addition, some other subacute/chronic diseases, such as pulmonary neopla-sia, could be regarded in differential diagnosis. Based on these facts, we suggest that special attention to epidemiolo-gic information during anamnesis, place of residence, main occupation, and leisure activities should be carried out. Cases of disseminated coccidioidomycosis present a more difficult situation for physicians because the range of diagnoses is even wider. Commonly, no specific sign is found, and as in the case we describe here, no epidemiologic data were clear. For these reasons, generally, these cases take

a long time to establish the final diagnosis and cause high morbidity to patients.

In the 1st outbreak of coccidioidomycosis in Ceará State, a group of 4 young men presented respiratory symptoms, fever, and headache after armadillo hunting. Sputum samples of only one of them were investigated for coccidioidomy-cosis in our laboratory by direct examination and culture, being positive in both examinations. Although diagnosis of this disease depends on laboratory support (Saubolle et al., 2007; Sutton, 2007), diagnosis of the remaining 3 patients was achieved by way of clinical and epidemiologic data (Comrie, 2005).

According to the guidelines of the Brazilian Ministry of Health, laboratory diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis should be performed by direct microscopic examination or culture of clinical specimens in mycological agar (Brasil, 2006). Although the presence of endospore-containing spherules is unquestionably diagnostic of the disease, immature spher-ules may often be mistaken for phagocytic cells or microscopic artifacts (Sutton, 2007). Free endospores may be confused with H. capsulatum, Cryptococcus spp., or Candida spp. (Saubolle et al., 2007; Sutton, 2007). In Fig. 2. Laboratory diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis. (A) Direct microscopy of sputum sample with spherules filled with endospores. (B) Characteristic

Coccidioides-like barrel-shaped arthroconidia alternating with empty disjunctor cells prepared in lactophenol cotton blue stain. (C) Positive immunodiffusion test performed with a patient serum sample (S) against commercial (1) and experimental (2) antigens. (D) Nested PCR amplification of Ag2/PRA gene from sputum sample (1) andC. posadasiicontrol (2).

addition, false-negative direct microscopy results may be related to poor quality of respiratory specimens, which frequently are contaminated with saliva and contain many squamous epithelial cells.

In Brazil, coccidioidomycosis occurs in rural areas, which are lacking in BL3 laboratories and trained personnel. However, since the 1st coccidioidomycosis outbreak in Ceará State in 1995 (Sidrim et al., 1997), laboratory diagnosis of the disease has been performed at the Specialized Medical Mycology Center—the 1st laboratory in this state whose personnel are trained in handling BL3 fungal pathogens. Our experience has shown that culture is a very sensitive diagnostic method, because the clinical specimens of all 14 patients investigated proved positive.

The recovery of Coccidioides spp. by culture is still performed as a definitive diagnostic method by several laboratories (Sutton, 2007). Identification of Coccidioides spp. may be achieved by visualization of barrel-shaped arthroconidia alternated with empty cells from mature colonies (Saubolle et al., 2007). Despite the fact that other fungi species, such asMalbrancheaspp., may also produce arthroconidia, onlyCoccidioides spp. have been recovered from human pulmonary disease (De Hoog et al., 2001). However, the hazardous potential of C. posadasii cultures discourages this practice in many Brazilian clinical labora-tories. In our country, current culture-based diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis is performed by only 2 reference centers: CEMM and Fiocruz (Fundação Oswaldo Cruz), lead by Dr Júlio Sidrim and Dr Bodo Wanke, respectively.

A safer approach to laboratory diagnosis of coccidioido-mycosis is based on serologic assays such as immunodiffu-sion, enzyme immunoassay, latex agglutination, and complement fixation (Saubolle et al., 2007). Among these procedures, immunodiffusion testing seems to be the most suitable for smaller laboratories because it is inexpensive and easy to perform. However, false-positive reactions have been detected by commercial ID antigen with sera samples from individuals without clinical and laboratorial diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis (data not shown). Based on these facts, we decided to produce a crude antigen extract to be used in immunodiffusion tests for diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis in South America.

Our antigen protocol preparation requires equipment and techniques available in ordinary NB3 laboratories. The ID test does not exclude the culture-based diagnosis, but it seems very useful for presumptive diagnosis of coccidioi-domycosis. Nevertheless, it is important to state that negative results on serologic investigations do not rule out the presence of coccidioidomycosis infection (Papagianis, 2001), mainly on early phase on infectious diseases or in immunocompromised patients. Antibody titration in quanti-tative ID with our antigen should be standardized to follow patient recovery.

Molecular detection ofC. posadasiiby PCR is likely to become an important approach for coccidioidomycosis diagnosis in Brazil. Although it requires a well-structured

laboratory and trained technicians, it provides faster results and can be performed in BL2 containment. An additional advantage of this approach is the possibility to perform tests even with contaminated sputum samples (Cordeiro et al., 2007). Our results showed that PCR reactions are suitable for identification ofC. posadasiifrom both primary and stored cultures. Other molecular approaches based on DNA hybridization methods, chiefly the Gen-Probe test, have been performed for laboratory diagnosis of coccidioidomy-cosis (Valesco, 2008). Although the AccuProbe identifica-tion test provides rapid, sensitive, and specific confirmaidentifica-tion of the pathogen (Gromadzki and Chaturvedi, 2000), direct molecular probes are not yet available for routine laboratory diagnostic of coccidioidomycosis (Saubolle et al., 2007).

Based on our experience, we suggest the following procedures to optimize the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis: (1) sending suspect clinical samples for mycological examination in a reference laboratory, (2) performing qualitative or semiquantitative immunodiffusion tests with standard and experimental antigens in smaller laboratories, and (3) performing direct PCR reaction with clinical samples and/or suspicious cultures in BL2 laboratories. We believe that improved laboratory diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis will bring a new perspective to epidemiology of this disease in South America.

As explained, in our country, coccidioidomycosis is an underdiagnosed disease, although it may occur even in hosts with no specific risk factors. Nineteen cases were observed during this study, and probably many others had been misdiagnosed or not diagnosed. We believe that strategies for improvement of our diagnostic methods should be empha-sized and applied by local authorities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CNPq Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (process: 620161/2006-0) and FAPESP Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (process: 04/14270-0).

References

Bialek R, Kern J, Herrmann T, Tijerina R, Ceceñas L, Reischl U, González GM (2004) PCR assays for identification of Coccidioides posadasii

based on nucleotide sequence of the antigen 2/proline-rich antigen.

J Clin Microbiol42:778–783.

Brasil, Ministério da Saúde (2006) Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde, Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica. Doenças infecciosas e parasitárias: guia de bolso, Vol. I. Ministério da Saúde; Brasília, pp. 320. Available at http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/ guia_bolso_6ed.pdf.

Burt A, Carter DA, Koenig GL, White TJ (1995) A safe method of extracting DNA fromCoccidioides immitis.Fungal Genet Newsl42:11. Clemons KV, Capilla J, Stevens DA (2007) Experimental animal models of

coccidioidomycosis.Ann N Y Acad Sci1111:208–224.

Comrie AC (2005) Climate factors influencing coccidioidomycosis seasonality and outbreaks.Environ Health Perspect13:688–692. Cordeiro RA, Brilhante RSN, Rocha MFG, Fechine MAB, Camara LM,

Camargo ZP, Sidrim JJC (2006) Phenotypic characterization and

ecological features ofCoccidioides spp. from Northeast Brazil.Med Mycol44:631–639.

Cordeiro RA, Brilhante RSN, Rocha MFG, Fechine MAB, Camargo ZP, Sidrim JJC (2006)In vitroinhibitory effect of antituberculosis drugs on clinical and environmental strains of Coccidioides posadasii.

J Antimicrob Chemother58:575–579.

Cordeiro RA, Brilhante RSN, Rocha MFG, Moura FEA, Camargo ZP, Sidrim JJC (2007) Rapid diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis by nested PCR assay of sputum.Clin Microbiol Infect13:449–451.

Costa FAM, Reis RC, Benevides F, Tomé GS, Holanda MA (2001) Coccidioidomicose pulmonar em caçador de tatus. J Pneumol 27: 275–278.

Cox R, Magee DM (2004) Coccidioidomycosis: host response and vaccine development.Clin Microbiol Rev17:804–839.

De Hoog GS, et al. (2001) Atlas of clinical fungi (2nd ed.).Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures/Universitat Rovira i Virgili; Reus, pp. 1160. Fisher MG, Koenig GI, White TJ, Taylor JW (2002) Molecular and

phenotypic description ofCoccidioides posadasiisp. nov., previously recognized as the non-California population ofCoccidioides immitis.

Mycologia94:73–84.

Gromadzki SG, Chaturvedi V (2000) Limitation of the AccuProbe Cocci-dioides immitis culture identification test: false-negative results with formaldehyde-killed cultures.J Clin Microbiol38:2427–2428. Hector RF, Laniado-Laborin R (2005) Coccidioidomycosis-a fungal disease

of the Americas.PLoS Med2:e2.

Papagianis D (2001) Serologic studies in coccidioidomycosis.Semin Respir Infect16:242–250.

Saubolle MA, McKellar PP, Sussland D (2007) Laboratory aspects in the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1111: 301–314.

Sidrim JJC, Silva LCI, Nunes JMA, Rocha MFG, Paixão GC (1997) Le Nord-Est Brésilien; Région d'endémie de coccidioidomycose? A propos d'une micro-épidémie.J Mycol Méd7:37–39.

Silva TMJ, Brito M, Almeida ERB (1999) Coccidioidomicose pulmonar fatal no semi-árido cearense.XXXV Congresso da sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical, 1999 Guarapari-ES.Rev Soc Bras Med Trop32: 483.

Sutton DA (2007) Diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis by culture: safety considerations, traditional methods, and susceptibility testing.Ann N Y Acad Sci1111:315–325.

Umeyama T, Sano A, Kamei K, Niimi M, Nishimura K, Uehara Y (2006) Novel approach to designing primers for identification and distinction of the human pathogenic fungi Coccidioides immitisand

Coccidioides posadasiiby PCR amplification.J Clin Microbiol 44: 1959–1962.

Valesco M (2008) Stability of frozen, heat-killed cultures ofCoccidioides immitis as positive- control material in the gen-probe AccuProbe

Coccidioides immitisculture identification test. J Clin Microbiol46: 1565.

Wanke B, Lazera MS, Monteiro PCF, Lima FC, Leal MJS, Ferreira Filho PL, Kaufman L, Pinner RW, Ajello L (1999) Investigation of an outbreak of endemic coccidioidomycosis in Brazil's northeastern state of Piauí with a review of the occurrence and distribution ofCoccidioides immitisin three other Brazilian states.Mycopathologia148:57–67.