w w w . j c o l . o r g . b r

Journal

of

Coloproctology

Original

Article

Health

locus

of

control,

spirituality

and

hope

for

healing

in

individuals

with

intestinal

stoma

Carmelita

Naiara

de

Oliveira

Moreira,

Camila

Barbosa

Marques,

Geraldo

Magela

Salomé

∗,

Diequison

Rite

da

Cunha,

Fernanda

Augusta

Marques

Pinheiro

UniversidadedoValedoSapucaí(UNIVÁS),PousoAlegre,MG,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received17July2015 Accepted25April2016 Availableonline30June2016

Keywords:

Intestinalstoma Internal-externalcontrol Spirituality

Religion Hope

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Objective:Toassessthehealthlocusofcontrol,spiritualityandhopeofcureinpatientswith intestinalstoma.

Methods:ThisstudywasconductedatthePoloofOstomizedPeopleinthecityofPouso Ale-gre,MinasGerais.Participantswere52patientswithintestinalstoma.Threequestionnaires wereappliedfordatacollection:aquestionnaireondemographicandstoma-relateddata; theScaleforHealthLocusofControl;theHerthHopeScale,andtheSelf-ratingScalefor Spirituality.

Results:Mostostomizedsubjectswerewomenagedover61years,marriedandretired.Asto thestoma,inthemajorityofcasestheseoperationsweredefinitiveandwerecarriedoutdue toadiagnosisofneoplasia.Mostostomizedsubjectshada20-to40-mmdiametercolostomy, 27showeddermatitisasacomplication,and39(75%)usedatwo-partdevice.Themeantotal scorefortheScaleforHealthLocusofControl,theHerthHopeScale,andtheSelf-rating ScaleforSpiritualitywere62.42,38.27,and23.67,respectively.Regardingthedimensions oftheScaleforHealthLocusofControl,thedimension“completenessofhealth”=22.48, dimension“externality-powerfulothers”=22.48,anddimension“healthexternality”=19.48.

Conclusion:Ostomizedpatients participatingin thestudy believe theycancontrol their healthandthatcaregiversandindividualsinvolvedintheirrehabilitationcancontribute totheirimprovement.Thecureorimprovementhasadivineinfluencethroughreligious practicesorbeliefs.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradeColoproctologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.This isanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/

licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:geraldoreiki@hotmail.com(G.M.Salomé).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcol.2016.04.013

Locus

de

controle

em

saúde,

Espiritualidade

e

Esperanc¸a

de

cura

nos

indivíduos

com

estoma

intestinal

Palavras-chave:

Estomaintestinal Controleinterno-externo Espiritualidade

Religiosidade Esperanc¸a

R

E

S

U

M

O

Objetivo: Verificarolocusdecontroledasaúde,espiritualidadeeesperanc¸adecuraem indivíduosostomizados.

Métodos:EsteestudofoirealizadonoPolodosostomizadosdacidadedePousoAlegre,Minas Gerais.Fizerampartedoestudo52pacientescomestomaintestinal.Foramutilizadospara coletadedadostrêsquestionários:questionáriosobreosdadosdemográficoserelacionados aoestoma;EscalaparaLocusdecontroledasaúde;EscaladeEsperanc¸adeHertheEscalade auto-classificac¸ãoparaEspiritualidade.

Resultados: Amaioriadosostomizadoseradogênerofemininocomidadeacimade61anos, casadoseaposentados.Comrelac¸ãoaoestoma,amaioriadessesdispositivoseradefinitiva eascausasparaasuaconfecc¸ãododispositivoforam,emsuamaioria,umdiagnósticode neoplasia.Amaioriadosostomizadostinhaumacolostomiacomdiâmetrode20a40mm eapresentavamdermatitecomocomplicac¸ão;e39(75%)utilizavamdispositivosdeduas pec¸as.AmédiadoescoretotaldaescalaparaLocusdecontroledasaúde,EscaladeEsperanc¸a deHerth,eEscaladeAuto-classificac¸ãoparaEspiritualidadefoide,respectivamente,62,42, 38,27e23,67.Comrelac¸ãoàsdimensõesdaEscalaparaLocusdeCcontroledaSaúde,foram obtidososseguintesvalores:dimensãointegralidade“saúde”=22,48,dimensão externali-dade“outrospoderosos”=20,48edimensãoexternalidade“saúde”=19,48.

Conclusão: Ospacientesostomizadosqueparticiparamdoestudoacreditamquepodem controlarsuasaúde,equeaspessoasenvolvidasnocuidadoeemsuareabilitac¸ãopodem contribuirparasuamelhora.Acuraoumelhorateminfluênciadivinapormeiodaspráticas oucrenc¸asreligiosas.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradeColoproctologia.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este esunart´ıculoOpenAccessbajolalicenciaCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/

licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

An ostomy is an artificial communication between organs orvisceraand theexternalenvironmentforobtainingfood andfordrainageanddisposal.Themakingofanintestinal ostomyisamedical-surgicalprocedureinwhichachangein bowelhabitsoccurs,changinganatomicallythepatient,with externalizationofahollowviscus(inthiscase,theintestine) throughhis/herbody,andwhichisinsertedintotheexternal abdominalwall.Takingintoaccounttheoriginofthedisease, theostomymaybetemporaryordefinitive.1,2

The individual, after being submitted to a stoma, not onlylose a segment ofhis/her body but alsoundergoes a changeinphysicalappearance andgoeson livingwiththe lossofcontrolofeliminationoffecesandgases,whichnow occur through the abdomen, and this type of control is a paramountconditionforlifeinsociety.3,4 Patientsarefaced

withachallenge,whichistheself-care,whichincludesthe exchange of the collector device and skin and peristomal hygiene.

Self-careisaprocessthatispartoftheacceptanceprocess, bythe stomauser, ofhis/her newphysicaland physiolog-icalcondition.Thiscondition mustbeseen asanecessary therapeutictreatmentthataimstoimprovethepathological picture,inordertocurethepatient,wherethepurposeisnotto diminishthequalityoflifeofthoseostomized,buttoprioritize theirhealthinallareas.4–9

Thus,somechangesinthedailylivesoftheseindividuals occur,rangingfromphysiological,anatomicaland gastroin-testinalalterationstotheachievementofself-care.Inaddition tothesephysicalchanges,psychological,emotionalandsocial changes also occur; these individuals may feel incompe-tent,uselesstodevelopday-to-dayactivities,andespecially self-care. Often the patient ends up suffering changes in his/herreligiousness, losingfaithand thehopeofrecovery orimprovement,forfearthathe/shewillnotbeableto per-formself-care(whichconsistsofcleaningtheperistomalskin andofexchangingandcleaningthebag).Consequently,this factpromoteschangesinqualityoflife,self-esteem, spiritu-ality,self-image,sexuality,familyandsociallifeandleisure activitiesoftheindividual.

Spiritualitycanbedefinedasabeliefsystemthatincludes intangibleelementsthatconveyvitalityandmeaningtolife events.Suchabeliefcanmobilizeextremelypositiveenergies andinitiatives,withunlimitedpotentialtoimprovethe per-son’squalityoflife.Religiouspeoplearephysicallyhealthier, havemorehealthfullifestyles andrequire lesshealthcare. Thereisanassociationbetweenspiritualityandhealththatis probablyvalidandpossiblycausal.Itisfullyrecognizedthat thehealthofindividualsisdeterminedbytheinteractionof physical,mental,socialandspiritualfactors.10,11

Hope is a state associated with a positive outlook for the future, a way to cope with the situation that one is experiencing,12,13 inwhichthe individualhasfaithand the

individualtoactandgivesstrengthtosolveproblemsand con-frontations,suchasloss,tragedy,lonelinessandsuffering.14

Healthlocusofcontrolisasetofbeliefsthatindividuals layonthesourceofcontrolofusualbehaviorsoreventsthat occur to themselves or to the environment in which they areinserted,indicatingtheexistenceofacontrolof internal-externalreinforcement,withregardtothedegreetowhichthe individualbelievesthatthereinforcementsarecontingenton his/herconduct.15,16

Theconstruct“healthlocusofcontrol”isdesignedas a multidimensional variable. External beliefs can be divided into random expectations (the reinforcement would be determinedbyluck,byfate)andexpectationsthatthe rein-forcements would bedependent onthe actionofpowerful others(suchasfamily,teachersordoctors).Thesubjectswho believethatpowerfulotherscontroltheirlivescanact differ-ently,incomparisonwiththosewhobelievethattheevents oftheirlivesemergechaoticallyandunpredictably.17,18

Theevaluationofthehealthlocusofcontroland spiritu-alityandhopeofcurecanbecomeanessentialinstrumentin guidinghealthactionsforostomizedpeople,consideringthat thisprovidessubsidiesforabetterunderstandingofthe psy-chosocialandemotionalfactorsinvolvedwiththedifficulties oflivingwiththestomaandintheachievementofself-care.

Thestudyofaspectsofspiritualityandhopeofcurewill providerelevantinformationwhichmay influencethe self-carebytheostomizedindividualand his/heracceptanceof beinganostomizedpatientandinlivingwiththestoma.Thus, thisstudyaimstodeterminethehealthlocusofcontrol, spiri-tuality,andhopeofacureinpatientswithanintestinalstoma.

Methods

Thisisadescriptive,cross-sectionalanalyticalstudy. ThisstudywasconductedatthePoloofOstomized Peo-pleinthecityofPousoAlegre,MinasGerais.52patientswith intestinalstomawereincluded.

Theinclusion criteriawere age ≥18 years and being an

intestinalstomacarrier,andexclusioncriteriawerepatients withdementia syndromesand other conditionsthat could preventthemfromunderstandingandansweringtothe ques-tionnaires.

DatawerecollectedafterapprovalbytheEthics Commit-teeonResearchoftheFaculdadedeCiênciasdaSaúde“Dr. JoseAntonioGarciaCoutinho”andaftertheFreeandInformed Consent Form was signed by the patient or his/her care-giver(opinionnumber:620462). Data werecollected bythe researchersthemselves. Theinclusion ofthepatientinthe studyfollowedtheorderofarrivalattheoutpatientclinic.The samplewasselectedinanon-probabilistic,byconvenience, way.

Fordatacollection,threequestionnaireswereapplied:first, aquestionnaireondemographicandstoma-relateddata;then theScaleforHealthLocusofControl;thethirdquestionnaire wastheHerthHopeScaleand,finally,theSelf-ratingScalefor Spirituality.Eachinterviewlastedapproximately25min.

TheScaleforHealthLocusofControlhasbeentranslated andvalidated forthePortugueselanguage.Theinstrument validation,afterapplicationinfoursamples,wasverifiedas

to the reliability (internal consistency) through Cronbach’s alpha,andthevaluesfoundforthesubscaleswere: Internal-ityforhealth,0.62–0.71;Externality-chanceforhealth,0.51–0.78; andExternality-powerfulothers,0.62–0.67.Thisscaleconsistsof threesubscales,eachcontainingsixitemsregardingthe fol-lowingdimensions:Internalityforhealth(items1,6,8,12,13 and 17),whereinthescoresreflectthedegreetowhichthe subjectbelievesthathe/shehimselfcontrolshis/herstateof health;externality-powerful othersforhealth(items3,5,7,10, 14 and 18), wherein the scoresreflectthe degree towhich the subjectbelievesthatother persons orentities(doctors, nurses,friends,family,God,etc.)cancontrolhis/herhealth; andExternality-chanceforhealth(items2,4,9,11,15and16), in whichthe scoresindicate thedegree towhicha person believes that his/herhealth iscontrolled atrandom, with-outhis/herinterferenceortheinterferencefromotherpeople The scores for each dimension range from 1to 5; for the alternatives“Itotallyagree,”“Ipartiallyagree,”“Iam unde-cided,” “I partiallydisagree,” and “I strongly disagree,” the followingvaluesarerespectivelyadded:5,4,3,2,and1.The score obtained for the dimensions willbe the sum of the itemsofthesubscaleatissue.Thetotalvalueofitems belong-ingtoeachofthethreesubscalesrepresentsthetotalscores withrespecttothedimensionofthehealthlocusin ques-tion.Thetotalamountobtainedfromeachsubscalemayvary between 6and 30 andindicates that the higherthe value, the strongerthe belief inthisdimension.Thescale is pre-sentedinitsentirety,inwhichtheitemsofthesubscalesare interleaved.12,19

The Escala da Esperanc¸a de Herth (EEH),that is, the Por-tuguese version of the Herth Hope Scale, is a tool which consistsof12itemswithatotalscoreof12–48points,with responsesproducedinaLikert-likescale,withscoresfrom1to 4pointsforeachoneoftheseitems.Thehigherthescore,the greaterthehope.Theitems3and6haveaninvertedscore.18,20

Intheassessmentoftheresults, datawere enteredand analyzedusingthestatisticalprogramSPSS v.8.0.Fordata analysis, the following statistical tests were used: for the distributionofabsolute(n)andrelative(%)frequencies, Pear-son’sChi-squaredtestwasused,whichdeterminedwhether thedistributionwasdifferentfrom5%,thatis,p<0.05.The comparisonbetween two groupswas performed using the Mann–Whitney test; and when there were more than two groups,theKruskal–Wallistestwasused.Forthecorrelationof continuouswithsemi-continuousvariables,theSpearman’s correlationtestwasused.

Results

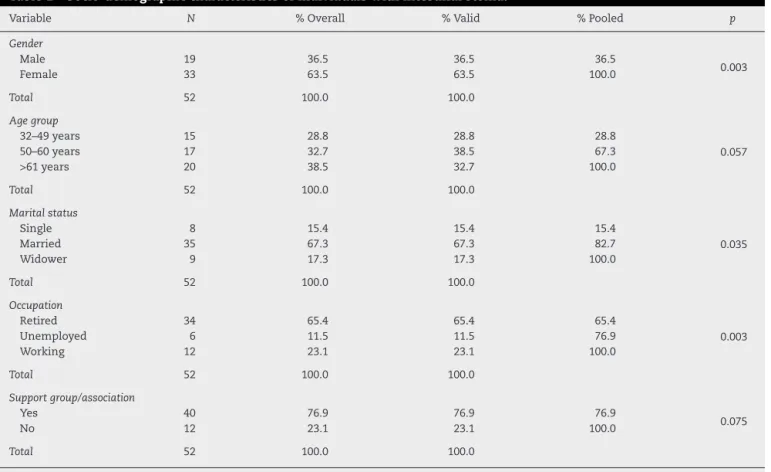

Table1shows that33(63.5%)patientswerefemale, and20

(38.5%)wereagedover61years.36%oftheparticipantsinthis studyweremarried,34(65.4%)wereretired,40(76.9%) partici-patedinasupportgrouporassociation.Thevariablesgender, maritalstatus,andoccupationhadstatisticalsignificance.

Table2showsthatthemaincauseofmakingthestoma

wasthepresenceofaneoplasmin40(76.9%)patients,and40 (76.9%)stomataweredefinitive.44(84.6%)patientsreceiveda colostomy,andin27(51.9%)thestomameasured20–40mm. 31(51.7%)oftheparticipantsshoweddermatitis,and39(75%) usedtwo-piecedevices.Allthesevariableswerestatistically significant.

Table3showsthatthemeantotalscoreoftheScalefor

HealthLocusofControlwas62.42;fortheHerthHopeScale,it was38.27;andfortheSelf-ratingScaleforSpirituality,itwas 23.67.Theseresultswerestatisticallysignificant.

Table4showsthedimensionsoftheScaleforHealthLocus

ofControl:22.48forthedimension“Completenessofhealth”, 20.48 forthe dimension “Externality-powerfulothers”, and 19.48forthedimension“Externality-health”,allwith statis-ticalsignificance.

Discussion

Regardingsociodemographiccharacteristicsofthe52patients withintestinalstomaincludedinthisstudy,mostwereelderly womenagedover 60,retired, married,and participating in asupportorassociation group,whichisinline withother investigationswhosesubjectshadanintestinalstoma.5,9

The gender of the stomized individual can influence his/hersocialadaptation.Womentendtorequirelesstimeto rehabilitationbutshowsignificantdegreesofdespair, depres-sion and fear in the preoperative period. Men, especially thosewhodevelopimpotence,takealongertimetorespond satisfactorilytotheirroutineactivities,andexhibitmore sig-nificantdifficultiesforself-care.23Itisimportanttopointout

that the elderly have unique biological characteristics and thatthisagegroupismorevulnerabletochronicdiseases,for instance,neoplasms.

Theoccurrenceofstomacomplicationsismultifactorial, involvingfromthemakingofthestomatillitslocation, obe-sity,andinfluenceoftheagefactor.Thus,whenthesefactors areassociatedwiththephysiological changesofaging,the expectedoutcomeisagreatervulnerabilityoftheelderlywith respecttotheincidenceofcomplicationsinthestoma.24

Inthisstudy,mostparticipantswereilliterateandretirees. Thisresultrevealsadisturbing profile,whenonethinksin termsofcitizenshipandrespectforindividualrights,taking intoaccountthatitisknownthatthelowertheeducational level,themoreunfavorableisthelinguisticcapitalofthe indi-vidualtothequestioningofprofessionalsand leaderswith respecttohis/herhealthproblems,thecaretobeoffered,and therightsthatareinherenttoeachperson.Itisimportantto notethatthissituationdoesnotaffecttheperformancewith these peoplebecause theinteraction betweenuser, service andhealthprofessionalshavemadepossibletoovercomethe difficultiesimposedbythisvariable.

Datarelatingtothestomaindicatethat,inmostofthe par-ticipants,neoplasiawasthemaincausalfactortothestoma; thetypeofostomyperformedwascolostomy,andtheostomy wasofthedefinitivetype;theuserswereprovidedwitha 2-piecebag,andmosthaddermatitisasacomplication.With respecttothe stomasize, mostaveraged20–40mm. These findingsagreewithseveralstudiespublished.7,25–28

Itisworthnotingthatthetimespentwiththestomawill dependonthecausativefactorandontheclinicaloutcome afterits making.Thus,anoriginallytemporary stomamay becomepermanent,dependingontheimpeditivefactorsto the reconstructionofintestinaltransit,takinginto account thatinmanycasesthediseasesofthegastrointestinaltract lead toaradical surgery,resulting inatemporary, oreven definitive,ostomy.24

Anotherstudyexaminedtheknowledgeoftheostomized individual regardingthe properself-care afterhospital dis-charge and the incidence of complications related to the stoma. This is a qualitative, exploratory, field study with quantitative data contribution. In our study, we applied a semi-structuredinterviewasatechniquefordatacollection. Tenpatientswithanintestinalstoma(colostomy/ileostomy) participatedinthisstudy,andtheresultsdemonstratedthat mostpatientshaddifficultywithself-care,thankstoalack ofproperguidanceand/orthehelpofprofessionalstrainedto workinthisphaseoftreatment.29

Oneshouldalsoconsiderthatsomecomplicationsincrease with age and alsoin patients without demarcation of the stoma.Consideringthatnostomademarcationwascarried out in the study population (predominantly composed of elderly),itcanbesaidthatthisfactwasoneofthefactorsthat mayhavecontributedtothedevelopmentofcomplications, suchthoseaforementioned,thusconfirmingthefindingsin otherstudies.

Generally, dermatitis in an injury resulting from an improperuseofcollectorequipment,morepreciselyby exces-sivecuttingoftheholeintheprotectivebarrierrelativetothe stoma(thus,theskinisexposedtotheactionoftheeffluent), orbyinadequateindicationofequipmentwithrespecttothe typeofstomaatissue.Collectorsandadjuvantsonthemarket shouldbepresentedindetailtoostomizedpatients.Insome services,theequipmentusedisrecommendedbasedonthe resultsoftheassessmentmadeatthetime;butovertime,the devicecanbereplaced.Thus,acontinuousassessmentisin order.30

Table1–Socio-demographiccharacteristicsofindividualswithintestinalstoma.

Variable N %Overall %Valid %Pooled p

Gender

Male 19 36.5 36.5 36.5

0.003

Female 33 63.5 63.5 100.0

Total 52 100.0 100.0

Agegroup

32–49years 15 28.8 28.8 28.8

0.057

50–60years 17 32.7 38.5 67.3

>61years 20 38.5 32.7 100.0

Total 52 100.0 100.0

Maritalstatus

Single 8 15.4 15.4 15.4

0.035

Married 35 67.3 67.3 82.7

Widower 9 17.3 17.3 100.0

Total 52 100.0 100.0

Occupation

Retired 34 65.4 65.4 65.4

0.003

Unemployed 6 11.5 11.5 76.9

Working 12 23.1 23.1 100.0

Total 52 100.0 100.0

Supportgroup/association

Yes 40 76.9 76.9 76.9

0.075

No 12 23.1 23.1 100.0

Total 52 100.0 100.0

Pearson’sChi-squaredtestandp≤ 0.05.

ostomizedpatient.Thesedifficultiesconcerntheacceptance ofchangesinbodyimage,lifestyle,socialrelationshipsand

sexualperformance– whichcan leadtopsychologicaland

socialdisorders,oftendifficulttoovercome.29

Inrecentyears,the increaseinlifeexpectancyhas con-tributed to the worldwide increase in the incidence and prevalenceofchronicdiseases,especiallydiseasesinwhich peoplereceivestomata.Thus,theneedsofpeoplewhohave toliveinthisconditionaresignificantandaffectmanyaspects oftheirlives,withtheincorporationofnewhabits,aswellas, ofnecessity,areviewandadaptationofsocialroles.

Inthis study,the resultsrelatedto theScaleforHealth LocusofControlrevealedthatostomizedindividuals partic-ipatinginthestudybelievethattheycancontroltheirhealth, andthatthepeopleinvolvedintheircareandrehabilitation cancontributetotheirimprovement.Butthisimprovement andthecurehavenodirectinterferenceinpeopleinvolvedin thetreatment.

Oftentheadaptationofostomizedindividualsoccurswith theadjustmentoflifeinanewcontext,inwhichimportant factorssuchasthewayoflife,sociallifeandfeedinghabits havetobeabandoned,replacedordiminishedinagreat num-berofcases.Thus,thisisanindividualprocessthatdevelops overtimeandthatinvolvesanumberofaspects,rangingfrom the help provided, tothe way the person gets involved in his/herowncare.31

With an intestinal stoma, the patient experiences momentsofconflict,concernsanddifficultiesindealingwith this new situation. This leads the individual to visualize

his/herlimitationsand tofacethe changesinhis/herdaily life.32Thus,itisimportantthatthepatientreceivessupport

fromfamily,friendsandevenfromthoseprofessionalswho arehelping.Withthissupport,thepatientwillfindstrength toovercomethedifficultiesandbarriersrelatedtoself-care andthechangesthatarebeingexperiencedinhis/herdaily live.

The health locus of control is a model that questions whetherthebeliefsoftheindividual,thatis,motivation (inter-nal and external), determine the action to be taken. The individualwhobelievesthattheresults,atleastinpart,are dependentontheactionstaken,isconsideredasinternally oriented;ontheotherhand,thosewithanexternalorientation generallydonotbelieve,orscarcelybelieve,intheexternal relationoftheoutcome,andintheindividualaction.33The

beliefsinfluencetheindividualwithastomaontheperception andexpressionofhopeandfaithinhis/hercureor improve-ment,andonhowtohandlethesevaluesintheinteraction withastomizedhumanbeing.

Table2–Characteristicsofintestinalstoma.

Variable N %Overall %Valid %Pooled p

Causeofostomy

Neoplasia 40 76.9 17.3 76.9

0.003

Inflammatoryboweldisease 9 17.3 17.3 94.2

Trauma 2 3.8 3.8 98.1

Other 1 1.9 1.9 100.0

Total 52 100.0 100.0

Stomatype

Colostomy 44 84.6 84.6 84.6

0.007

Ileostomy 8 15.4 15.4 100.0

Total 52 100.0 100.0

Stomadiameter

0–20mm 12 23.1 23.1 23.1

0.056

20–40mm 27 51.9 51.9 75

40–60mm 10 19.2 19.2 94.2

60–80mm 3 5.8 5.8 100.0

Total 52 100.0 100.0

Complicationtype

Dermatitis 31 51.7 51.7 51.7

0.0023

Fistula 2 3.3 3.3 55

Granuloma 2 3.3 3.3 58.3

Bleeding 2 3.3 3.3 61.7

Peristomalhernia 6 10.0 10.0 71.7

Pseudo-verrucouslesions 5 8.3 8.3 80.0

Allergicreaction 9 15.0 15.0 95.0

Allergy 3 5.0 5.0 100.0

Total 60 100.0 100.0

Typeofdevice

One-piecesystem 13 25 25 25

0.043

Two-piecesystem 39 75 75 100.0

Total 52 100.0 100.0

Stomacharacter

Temporary 12 23.1 23.1 23.1

0.003

Definitive 40 76.9 76.9 100.0

Total 52 100.0 100.0

Pearson’sChi-squaredtestandp≤0.05.

Table3–ResultsobtainedinthemeanscorefortheScaleforHealthLocusofControl,HerthHopeScaleandSelf-rating ScaleforSpiritualityinpatientswithintestinalstoma.

Descriptivelevel ScaleforHealthLocusofControl HerthHopeScale Self-ratingScaleforSpirituality

Mean 62.42 38.27 23.67

Median 63 38 24.5

Standarddeviation 7.944 3.515 5.279

Minimum 45 32 11

Maximum 81 47 30

P-Value 0.023

Mann–Whitneytest,Kruskal–Wallistestandp≤ 0.05.

Inthese studies related to the dimensionsof the Scale

forHealthLocusofControl, thepatients respondedas fol-lows:(22.48)relatedtothedimension“Completeness-health,” (20.48) related to the dimension“Externality-powerful oth-ers,” and (19.48) related to the dimension “Externality to health,”withstatisticalsignificance,thuscharacterizingthat theostomizedindividualsparticipatinginthestudybelieve

that they can control their health and that the people

involvedintheircareandrehabilitationcancontributetotheir improvement.However,thisimprovementandthecuredonot interferedirectlyinthepeopleinvolvedintheirtreatment.

Table4–ResultsobtainedinthemeanscorefortheScaleforHealthLocusofControl,HerthHopeScaleandSelf-rating ScaleforSpiritualityinpatientswithintestinalstoma.

Descriptive level

Dimensions

Internalityforhealth Externality–“powerfulothers” Externalityforhealth

Mean 22.48 20.48 19.48

Median 22.5 20 20

Standarddeviation 2.646 4.444 4.881

Minimum 16 12 10

Maximum 28 19 30

p-Value 0.031

Mann–Whitneytest,Kruskal–Wallistestandp<0.05.

caredependsmoreonothersthanonhimself.Itwasfound

thatthedimension“Internality”andthatoftheindex“Total internality”influencetheadherencetotreatmentandto self-careandrehabilitationofostomizedpeople,thatis,ostomized individualswithmore“Internality”adheredlesstotheir treat-ment.Theseresultsdemonstratetheimportanceofbeliefsin

thetherapeuticmanagement,andintherehabilitationand

self-care;andthatspecificinterventions,aimedatincreasing theadherence,shouldbetested.

Thediseasedpersoncanexperiencesituationsof

power-lessnessstemmedfromseveralfactors,rangingfromchanges relatedtothediseasetotheinteractionwiththehealthteam. Thelocusofcontrolinfluencesthepatient’sbehaviorinthe faceofthehealthproblem,bydirectingtheawarenessto fac-torsdependenton him/herselfor onother externalforces. Knowingtheorientationofthepatient’s locusofcontrolis important,inordertoforeseethe changesthatthepatient willneedtopromote,withaviewtoabettercontrolofhis/her treatment.35

Inthis study,assessed ostomizedpatients showedtotal meansof38.27and23.67forSelf-RatingScalefor Spiritual-ityandHerthHopeScale,respectively.Thesefindingsshow thattheseindividualshavehopeandfaithinGodthatthey willimproveandthattheypraytoGodforobtaininghelpto facethedifficultsituationstheyareexperiencing.

Spirituality and religion are related to each other, but althoughtheseconceptsareoftenusedinterchangeably,they donotshare thesame characteristics.Spiritualityis some-thingbroaderandmorepersonal,andisrelatedtoasetof innervalues,innerwholeness,harmony,andconnectionwith others;itstimulatesaninterestinothersandinourselvesand looksforaunitywithlife,nature,andtheuniverse.Spirituality iswhatgivesmeaningtolife,regardlessofone’sreligion,and thus,generatesthe capacitytoendure debilitating feelings ofguilt,angerandanxiety;furthermore,spiritualistaspects can mobilize positive energies and improve the quality of life.10Whenitcomestoostomizedpeople,spiritualitycanbe

contemplatedasoneofthecopingresourcesinperforming self-careandrehabilitation.

Inonestudy,theauthorsreportthatoneofthewaysof copingwiththediseaseandwithdeathisdirectlylinkedto theintensityoffaithandreligious beliefs-thatis,waysof expressingspirituality.Theauthorsconcludedthatoneofthe waysofcopingwithadverseandfavorablesituationsisinthe feelingoffaithinGod.FaithinGodisadeep-seatedfeelingin ourcultureandisasnecessaryastheotherwaysofcoping;

thediscourseshowsthatthespiritualdimensionoccupiesa prominentplaceinpeople’slivesandalsoshowsthatitisthat itessentialtobeawareofthespiritualityoftheuserstoplan anursingcare.35

Spiritualitycontributestothewell-beingofostomized peo-ple,favoring theirresilienceinthesuccessofself-care and rehabilitation. Certainreligious andspiritualbehaviors and beliefsaredirectlyrelatedtooverallhappinessandphysical health, consideringthattheydiscourageanengagementin unhealthy behaviors.Through thisstudy,weconclude that ostomizedpatientsbelievethatcancontroltheirhealthand that those people involvedin their careand rehabilitation cancontributetotheirimprovement.Theybelieveinadivine influenceonthecureorimprovement,throughreligious prac-ticesorbeliefs.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1.PittmanJ,RawlSM,SchmidtCM,GrantM,KoCY,WendelC,

etal.Demographicandclinicalfactorsrelatedtoostomy

complicationsandqualityoflifeinveteranswithanostomy.J

WoundOstomyContNurs.2008;35:493–503.

2.SampaioFAA,AquinoOS,AraújoTL,GalvãoMTG.Nursing

caretoanostomypatient:applicationoftheOrem’stheory.

ActaPaulEnferm.2008;21:94–100.

3.GomesIC,BrandãoGMON.Permanentintestinalostomes:

changesinthedailyuser.EnfermUFPE.2012;6:1331–7.

4.MauricioVC,OliveiraNVD,LisboaMTLO.enfermeiroesua

participac¸ãonoprocessodereabilitac¸ãodapessoacom

estoma.EscAannaNery.2013;17:416–22.

5.SaloméGM,AlmeidaSA,SilveiraMM.Qualityoflifeand

self-esteemofpatientswithintestinalstoma.JColoproctol.

2014;34:231–9.

6.SaloméGM,CarvalhoMRF,MassahudMR,MendesB.Profileof

ostomypatientsresidinginpousoalegrecityperfildos

pacientesostomizadosresidentesnomunicípiodepouso

alegre.JColoproctol.2015;35:106–12.

7.SalomeGM,AlmeidaSA.Associationofsociodemographic

andclinicalfactorswiththeself-imageandself-esteemof

individualswithintestinalstoma.JColoproctol.

2014;34:159–66.

8.SaloméGM,SantosLF,CabeceiraHS,PanzaAMM,PaulaMAB.

Knowledgeofundergraduatenursingcourseteachersonthe

preventionandcareofperistomalskin.JColoproctol.

9. CostaVF,AlvesSG,EufrásioC,SalomeGM,FerreiraLM.Body

imageandsubjectivewell-beinginostomistsinBrazil.

GastrointestNurs.2014;12:37–47.

10.AaadM,MasieroD,BattistellaLR.Espiritualidadebaseadaem

evidências.ActaFisiátr.2001;8:107–12.

11.SaloméGM,AlmeidaAS,FerreiraLM.Associationof

sociodemographicfactorswithhopeforcure,religiosity,and

spiritualityinpatientswithvenousulcers.AdvSkinWound

Care.2015;28:76–82.

12.HerthK.Therelationshipbetweenlevelofhopeandlevelof

copingresponseandothervariablesinpatientswithcancer.

OncolNursForum.1989;16:67–72.

13.JakobssonA,SegestenK,NordholmL,OreslandS.

EstablishingaSwedishinstrumentmeasuringhope.ScandJ

CaringSCI.1993;7:135–9.

14.HerthK.Abbreviatedinstrumenttomeasurehope:

developmentandpsychometricevaluation.JAdvNurs.

1992;17:1251–9.

15.HaslamSA,ReicherS.Stressingthegroup:socialidentityand

theunfoldingdynamicsofresponsestostress.JApplPsychol.

2006;91:1037–52.

16.RotterJB.Internalversusexternalcontrolofreinforcement:a

casehistoryofvariable.AmPsycholAssoc.1990;45:489–93.

17.LevensonH.Activismandpowerfulothers:distinctions

withintheconceptofinternal-externalcontrol.JPersAssess.

1974;38:377–83.

18.SartoreAC,GrossiSAA.Herthhopeindex:instrument

adaptedandvalidatedtoPortuguese.EscEnfermUsp.

2008;42:227–32.

19.Rodríguez-RoseroJE,FerrianiMGC,DelaCMF.Escaladelocus

decontroledasaúde–MHLC:estudosdevalidac¸ão.

Latino-AmEnferm.2002;10:179–84.

20.BalsanelliACS,GrossiSAA,HerthK.Assessmentofhopein

patientswithchronicillnessandtheirfamilyorcaregivers.

ActaPaulEnferm.2011;24:354–8.

21.GalanterM,DermatisH,BuntG,WilliamsC,TrujilloS.

Assessmentofspiritualityanditsrelevancetoaddiction

treatment.JSubstAbuseTreat.2007;33:257–64.

22.Gonc¸alvesMAS,PillonSC.Adaptac¸ãotransculturale

avaliac¸ãodaconsistênciainternadaversãoemportuguêsda

SpiritualityRatingScale.PsiquiatrClín.2009;36:10–5.

23.MacedoMS,NogueiraLT,LuzMHBA.Perfildosestomizados

atendidosemhospitaldereferênciaemteresina.Estima.

2005;3:25–8.

24.AguiarESS,SantosAAR,SoaresMGO,AncelmoMNS,Santos

RS.Complicac¸õesdoestomaepeleperiestomaempacientes

comestomasintestinais.Estima.2011;9:22–30.

25.BatistaMRFF,RochaFCV,SilvadMG,JúniorFJGS.Self-imageof

clientswithcolostomyrelatedtothecollectingbag.Bras

Enferm.2011;64:1043–7.

26.FortesRC,MonteiroTMRC,KimuraCA.qualityoflifefrom

oncologicalpatientswithdefinitiveandtemporary

colostomy.JColoproctol.2012;32:253–9.

27.NakagawaH,MisaoH.Effectofstomalocationonthe

incidenceofsurgicalsiteinfectionsincolorectalsurgery

patients.JWoundOstomyContNurs.2013;40:287–96.

28.CunhaRR,FerreiraAB,BackesVMS.Caractyeristica

sócio-demograficoeclínicodepessoasestomizados:revisão

deliteratura.Estima.2013;11:29–35.

29.TosatoSR,ZimmermannMH.Conhecimentodoindivíduo

ostomizadoemrelac¸ãoaoautocuidado.UEPG.2006;1:34–7.

30.FernandesRM,MiguirELB,DonosoTV.Perfildaclientela

estomizadaresidentenomunicípiodePonteNova,Minas

Gerais.BrasColoproct.2011;30:385–92.

31.NascimentoCMS,TrindadeGLB,LuzMHBA,SantiagRF.

Vivênciadopacienteestomizado:umacontribuic¸ãoparaa

assistênciadeenfermagem.TextoContexto–Enferm.

2011;20:557–64.

32.VieiraLM,RibeiroBNM,GattiMAN,SimeãoSFAP,ContiMHS,

VittaA.Câncercolorretal:entreosofrimentoeorepensarna

vida.Saúdedebate.2013;37:267–9.

33.SaloméGM,deAlmeidaAS,deJesusPMT,MassahudMR,de

OliveiraMCN,deBritoMJA,etal.Theimpactofvenousleg

ulcersonbodyimageandself-esteem.AdvSkinWoundCare.

2016;29:316–21.

34.CarvalhoSRM,BudóMLD,SilvaMM,AlbertiGF,SimonBS.

comumpoucodecuidadoagentevaiemfrente:vivênciasde

pessoascomestomia.TextoContextoEnferm.2015;24:

279–87.

35.KuritaGP,PimentaCAM.Adesãoaotratamentodador

crônicaeolocusdecontroledasaúde.EscEnfermUSP.