INICIAÇÃO DESPORTIVA, ATIVIDADES PRÉVIAS

E ESPECIALIZAÇÃO NO TREINO DE BASQUETEBOL E FUTSAL EM

PORTUGAL

Dissertação de Mestrado em Ensino da Educação Física nos Ensinos

Básico e Secundário

Sara Diana Leal dos Santos

Orientador: Professor Doutor Nuno Miguel Correia Leite

| i

AGRADECIMENTOS

A concretização deste trabalho foi conseguida com a colaboração, apoio e incentivo de um grande número de pessoas às quais quero expressar o meu agradecimento:

Ao professor Doutor Nuno Leite, pela orientação, disponibilidade e indispensável contributo na elaboração deste trabalho, o meu reconhecido apreço.

Á minha família, em especial aos meus pais, gostaria de agradecer o apoio incondicional, bem como a compreensão e amor transmitido ao longo destes anos.

Ao Victor, porque por trás de algo importante que se realize na vida, existe sempre alguém mais importante que nos apoia, acarinha, compartilha alegrias e tristezas, incentiva, ajuda a prosseguir e sobretudo, a confiar nas nossas capacidades.

Aos meus colegas de curso, juntos percorremos um longo percurso que está prestes a terminar, no entanto, as boas recordações vão perdurar para sempre.

A todos aqueles, que durante a minha vida contribuíram de alguma forma para a minha formação académica e pessoal.

| ii

ÍNDICE GERAL

AGRADECIMENTOS ... i ÍNDICE GERAL ... ii ÍNDICE DE TABELAS ……… iv INTRODUÇÃO GERAL ... 1ARTIGO 1 – THE PATH TO EXPERTISE IN PORTUGUESE AND USA BASKETBALL PLAYERS ………..………3 Abstract ... 5 Resumo ... 6 Extended Abstract ... 7 Introduction ... 9 Method ... 12 Participants ... 12 Procedures ... 12

Consistency of retrospective information ... 13

Statistical Analysis ... 14

Results ... 14

Discussion and Conclusions ... 15

References ... 20

ARTIGO 2 – INICIAÇÃO DESPORTIVA, ATIVIDADES PRÉVIAS E ESPECIALIZAÇÃO NO TREINO DE FUTSAL EM PORTUGAL ... 27

| iii Abstract ………... 30 Introdução ... 31 Método ... 34 Procedimentos ... 34 Análise Estatística ... 36 Participantes (Estudo 1) ... 37 Participantes (Estudo 2) ... 37 Resultados ... 38 Estudo 1 ... 38 Estudo 2 ... 39

Consistência das informações de caráter retrospetivo ... 41

Discussão ... 42

Conclusões e implicações práticas ... 47

| iv

ÍNDICE DE TABELAS ARTIGO 1

Table 1. Descriptive and inferential statistics for long-term development variables. ... 23 Table 2. Descriptive and inferential statistics for the activities performed across the

developmental stages ... 24

Table 3. Inferential statistics for the comparison between Portuguese and USA players. ... 25

ARTIGO 2

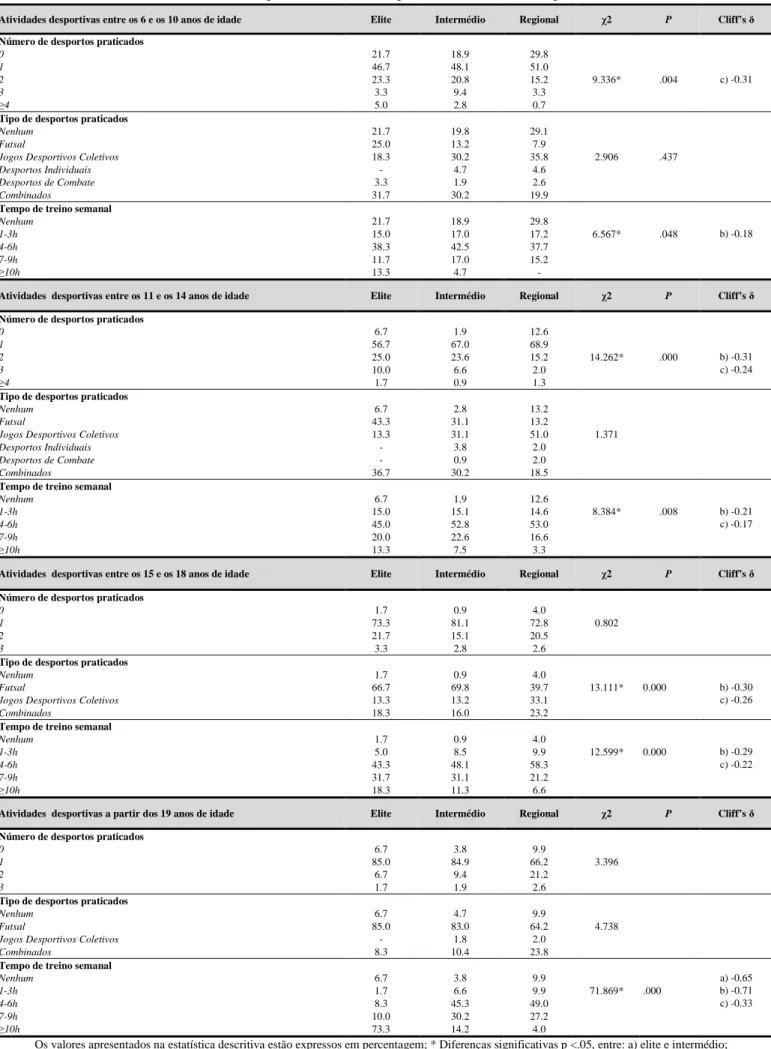

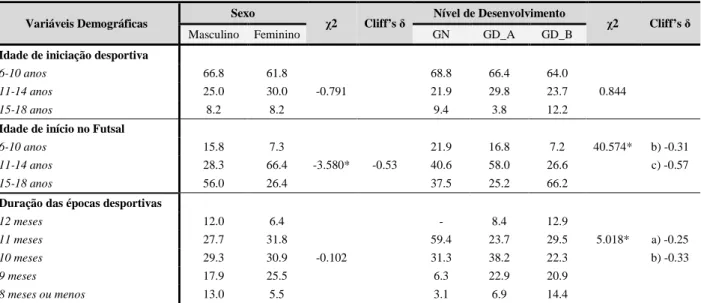

Tabela 1. Estatística descritiva e inferencial para as variáveis demográficas de desenvolvimento

a longo prazo (Estudo 1). ... 52

Tabela 2. Estatística descritiva e inferencial para as atividades desportivas nas diferentes etapas

de desenvolvimento (Estudo 1). ... 53

Tabela 3. Estatística descritiva e inferencial para as variáveis demográficas de desenvolvimento

a longo prazo (Estudo 2). ... 54

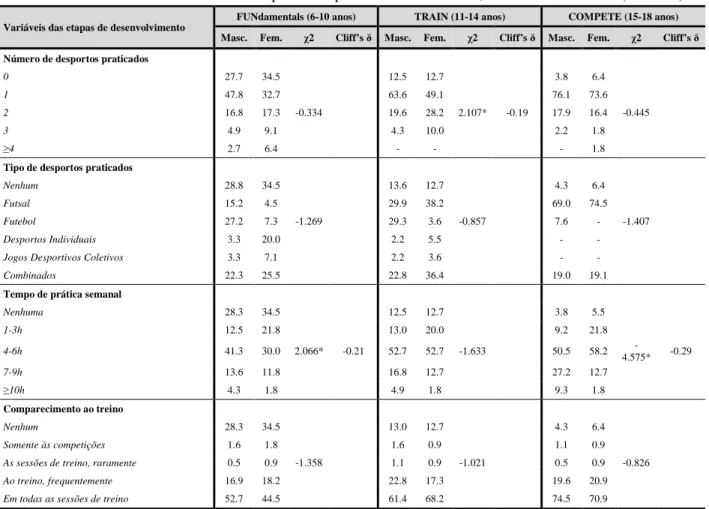

Tabela 4. Estatística descritiva e inferencial para as etapas de desenvolvimento, de acordo com

o sexo (Estudo 2). ... 55

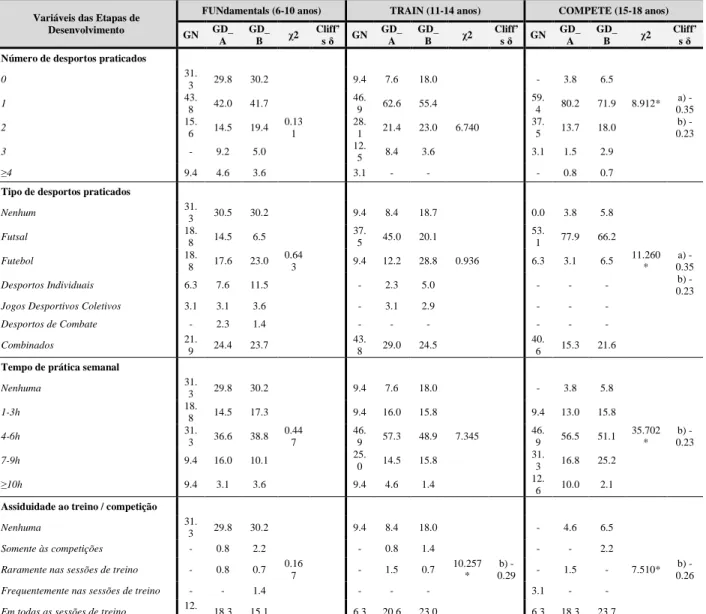

Tabela 5. Estatística descritiva e inferencial para as etapas de desenvolvimento, em função dos

| 1

INTRODUÇÃO GERAL

A respetiva dissertação é apresentada à Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro (UTAD), no DEP – ECHS, para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Ensino de Educação Física nos Ensino Básico e Secundário, cumprindo o estipulado na alínea b) do artigo 6º do regulamento dos Cursos de 2ºs Ciclos de Estudo em Ensino da UTAD, sob a orientação do Professor Doutor Nuno Miguel Correia Leite.

Apesar do seu carácter dissertativo, o seguinte trabalho, é resultado da compilação de dois artigos científicos. O primeiro artigo intitula-se: The path to expertise in portuguese and

USA basketball players, elaborado pelos seguintes autores, Sara Santos; Nuno Leite; Jaime

Sampaio e Miguel Gómez. O artigo foi submetido à revista científica Kinesiology, Indexado Science Citation Index Expanded, JCR Fator de Impacto (2010): 0.525.

O segundo artigo intitula-se: Iniciação desportiva, atividades prévias e especialização

no treino de futsal em Portugal, elaborado pelos seguintes autores, Sara Santos; João Serrano;

Jaime Sampaio e Nuno Leite. Este artigo foi submetido à Motriz Revista de Educação Física, JCR Fator de Impacto (2011): ainda não atribuído.

| 3

ARTIGO 1

THE PATH TO EXPERTISE IN PORTUGUESE

AND USA BASKETBALL PLAYERS

| 5

THE PATH TO EXPERTISE IN PORTUGUESE AND USA BASKETBALL PLAYERS

Sara Santos1; Nuno Leite1; Jaime Sampaio1 e Miguel Gómez2

1

Research Center in Sport Sciences, Health and Human Development (CIDESD), University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro at Vila Real, Portugal

2

Faculty of Physical Activity and Sport Sciences, Polytechnic University of Madrid, Spain

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to analyze the path to expertise of Portuguese and USA basketball players according to their specific playing position (i.e., guards, forwards and centers). The information needed to achieve this purpose was collected through a validated questionnaire applied to 75 Portuguese and 45 USA players playing in Portugal. The goal of this questionnaire was to provide detailed information about the quantity and type of sporting activities performed throughout their careers. The results suggest some variability in the path followed by the players according to the playing position, except for the conformity they displayed regarding an early sport diversification (especially between 6 and 10 years of age). Main findings emerging from this comparison suggest that while Portuguese basketball players specialize in basketball training earlier, the USA players seem to be guided to maintain a more comprehensive and diversified approach until 18 years of age.

| 6

Resumo

O objetivo do presente estudo pretende analisar o percurso desportivo dos jogadores de basquetebol portugueses e dos EUA de acordo com a sua posição específica em campo (bases, extremos e postes). A informação necessária para alcançar este objetivo foi obtida através de um questionário previamente validado, aplicado a 75 jogadores portugueses e a 45 jogadores dos EUA que atuam em Portugal. O prepósito deste questionário é providenciar informação detalhada sobre a quantidade e o tipo de atividades desportivas praticadas durante as carreiras desportivas dos jogadores. Os resultados sugerem alguma variabilidade nos percursos adotados pelos jogadores mediante a posição específica, no entanto, a recorrência à prática diversificada durante as etapas inicias é consensual (especialmente entre os 6 e os 10 anos de idade). Alguns aspetos emergem da comparação entre nacionalidades, sugerindo que enquanto os jogadores de basquetebol portugueses se especializam mais cedo, os jogadores dos EUA parecem estar mais orientados em manter o compromisso com a prática diversificada até aos 18 anos de idade.

KEYWORDS: aquisição de habilidades, etapas de desenvolvimento, talento, nacionalidade,

| 7

Extended Abstract

The path to expertise in team sports is a very complex process demanding the players to perform according to the requirements of their specific position in the court. Several studies have contributed to identify and differentiate the players based on their specific position and/or role in the court (i.e., guards, forwards and centers) in anthropometric, physiological, psychological, and game performance (see Ziv & Lidor, 2009). Therefore, is it possible that the early sport involvement of basketball players may influence their functional specialization? In Portugal, the success of basketball high-performance teams is much dependent on the recruitment of foreign players, whose influence is easily confirmed by their dominance in the variables of efficiency. Thus, a better understanding of the particularities surrounding the exaltation of the skills and abilities of the best foreigners playing in Portuguese professional leagues could be a crucial contribute to improve the national sport policy, especially the talent development and identification programs. Therefore, the objective of this study is to describe the pathway of the Portuguese players according to their specific position and compare these pathways with the ones followed by the USA players playing in Portuguese high-performance teams.

The sample was composed by 75 Portuguese senior male players, divided according to their specific position on the court (guards n = 23, forwards n = 30, centers n = 22) and 45 USA players (guards n = 7, forwards n = 18 and centers n = 20). The data collection was held in three consecutive seasons, between 2006/2007 and 2009/2010. Each participant completed a questionnaire developed specifically to provide a detailed longitudinal profile about the involvement in specific and non-specific sporting activities practiced by team sports. In order to test the hypothesis under study, Kruskal-Walls non parametric test was used to compare the players’ responses considering their playing position in the court (guards vs. forwards; guards vs. centers; and forwards vs. centers). The Mann-Whitney-U test was used to compare Portuguese and USA players, separately for each playing position.

| 8 The results suggest some variability in the path followed by the players according to the playing position, except for the conformity they displayed regarding an early sport diversification (especially between 6 and 10 years of age). Further evidence supported this so-called later commitment to basketball training linked with centers, especially in the basketball starting age (χ2 = 37.3, p< .05, ES = -0.85, see Table 1) and also in the time dedicated to training between 6 and 10 years of age and between 11 and 14 years of age, in which centers were outscored by guards and forwards in the initial stage (χ2 = 819, p< .05, ESguards vs. centers = 0.41, ESforwards vs. centers

= 0.39, see Table 2). The comparison between Portuguese and USA players revealed significant differences in the activities performed between 11 and 14 years of age, especially the number and type of sports. While Portuguese players reduce their sport experiences after 11 years of age and focus in basketball training, USA players kept their involvement in a wide range of combined sports until 15 to 18 years of age (Table 3).

The present study emphasized the heterogeneity of sport path of Portuguese players that seems to lead them to a higher specificity, what probably limited them to a more selective orientation to basketball. The distinct game competences manifested by the USA players in basketball may be the outcome of a strategy that guides the players to later sport specificity. It is also important not to forget that cultural factors contribute and influence sport policies and that in the Portuguese case the structure and demands of the youth competitions may be responsible for a growing specialization.

| 9

Introduction

The limits of human performance are continually challenged in sport, where athletes strive to achieve the highest competitive level throughout a non-linear process of acquisition and manifestation of expertise. Yet, this level is only achievable by a few exceptionally talented athletes, who seem to take advantage of innate and/or acquired skills developed in various forms of practice, such as free play, free practice, and deliberate play and deliberate practice (Côté, Baker & Abernethy, 2007).

Currently, several researchers are dedicating their effort in the attempt to provide detailed information about the trainable factors that most contribute to this exceptional performance level. Recognizing the importance of primary factors (Baker & Horton, 2004) such as genetic or psychological, strong evidence are arising in the last years from the retrospective analysis of training factors. Consistent findings with both experts and non-experts on learned capacities and abilities have been providing support for the relationship between training and expertise. However, despite a robust positive relationship between practice and performance has been suggested (Ericsson, Krampe & Tesch-Römer, 1993) consensus about the adequate type of early involvement (Baker, Horton, Robertson-Wilson & Wall, 2003) or training stimulus is still far from being achieved. For instance, specialists in the skill acquisition research have been exchanging arguments in favour or against early specialization and early diversification. On one side, the assumption that aspiring expert athletes need to limit their childhood sport participation to a single sport, with a deliberate focus on training and development in that sport (i.e. early specialization); on the opposite perspective (i.e. early diversification), which indicates the benefits of the involvement in a number of different sports before specializing in later stages of development (Côté, Lidor & Hackford, 2009).

Despite the weight of the evidences successively presented by each side in this dispute, it seems clear that sports are not all equal in terms of their maturational, physiological, psychological, technical or tactical requirements to succeed. While late specialization sports

| 10 including team sports, track and field, combative sports, cycling, and racquet sports, require a generalised approach to early training, on the other hand, early specialization sports, such as diving, gymnastics and swimming require early sport-specific specialization in training (Stafford, 2005). From this proposal for sports categorization follows the idea that long-term athletic development process must respect the existence of key periods where all forms of practice or training must be adjusted to the optimal trainability periods of motor skills (Ford, et al., 2011). Particularly in team sports, the participation in various sporting activities may be essential to the development of intrinsic motivation and enable a selective transfer of skills to the sport of prime interest, including physical (Baker, 2003) and creative behavior (Memmert, Baker & Bertsch, 2010). Moreover, this approach during the early stages of sport involvement helps the youngsters to refine their physical literacy, which is essential in the acquisition and development of more specific and complex skills (Stafford, 2005). Evidence from recent studies with expert players from team sports, did not fully supported this approach based in an early sport diversification. For instance, Leite, Baker and Sampaio (2009) found two different approaches to early sport involvement; while the majority of soccer and roller-hockey players started practicing their sport of prime interest between 6 and 10 years, volleyball and basketball players revealed a more variable in the age at which they began their main sport. The effect of cultural importance could possibly explain some of these results, especially in soccer by the popularity and pressure from media, parents, coaches, directors and even the players.

Taking these facts into consideration, it is imperative to reinforce that the path to expertise in team sports is a very complex process demanding the players to perform according to the requirements of their specific position in the court. Therefore, is it possible that the early sport involvement of basketball players may influence their functional specialization (i.e. if they will play guard, forward or center)? Several studies have contributed to identify and differentiate the players based on their specific position and/or role in the court (i.e., guards, forwards and centers, Dežman, Trninić & Dizdar, 2001; Sampaio, Janeira, Ibáñez & Lorenzo,

| 11 2006; Trninić & Dizdar, 2000; Trninić, Dizdar, & Dežman, 2000). Particularly in basketball, the differences according to the specific position are clear in anthropometric, physiological, psychological, and game performance (see Ziv & Lidor, 2009). Performance analysis research reflected that the players are distinguished according to certain abilities, specific tasks, knowledge or technical and tactical skills (Dežman, et al., 2001). In fact, previous research established a system of criteria to select and recruit basketball players by specific positions using game-related statistics profiles, attempting to help coaches’ decision-making process (Trninić, et al., 2000). Harbili, Harbili, and Yalçin, (2011) analyzed the importance of players’ recruitment in Turkish basketball league and their results showed that international players had higher efficacy ratings than Turkish players, however, no significant effects in efficacy ratings were found when players’ position and nationality factors were considered. According to these studies there is evidence of the importance of position on the court (i.e., guard, forward and center) and the nationality (within a country or international). However, no study has clarified if those variables are discriminating players already in terms of their sport pathway. Is it possible that the sport starting age or the age at which the players specialized in basketball, or even the type of sports experimented in the early involvement may influence the functional specialization? Moreover, it is important to understand if the path followed by the players is eventually restraining their development and not enabling the maximization of their potential.

In Portugal, the success of basketball high-performance teams is much dependent on the recruitment of foreign players, whose influence is easily confirmed by their dominance in the variables of efficiency. Thus, we think that a better understanding of the particularities surrounding the exaltation of the skills and abilities of the best foreigners playing in Portuguese professional leagues could be a crucial contribute to improve the national sport policy, especially the talent development and identification programs. Therefore, the objective of this study is to describe the pathway of the Portuguese players according to their specific position

| 12 and compare these pathways with the ones followed by the USA players playing in Portuguese high-performance teams.

Method Participants

The sample was composed by 75 Portuguese senior male players, divided according to their specific position on the court (guards n = 23, forwards n = 30, centers n = 22) and 45 USA players (guards n = 7, forwards n = 18 and centers n = 20). The data collection was held in three consecutive seasons, between 2006/2007 and 2009/2010. Players with less than 6 years of basketball training experience and/or under-24 years of age were excluded from the sample.

Procedures

Each participant completed a questionnaire developed specifically to provide a detailed longitudinal profile about the involvement in specific and non specific sporting activities practiced by team sports (Baker, Côté & Abernethy, 2003). Extensively reviewed by its authors in previous studies, this procedure allows the gathering of quantitative and qualitative information about the sporting activities in which the participants participated throughout their career. The completion of the questionnaire occurred in a quiet environment with a variable duration, between 30 minutes to 1 hour. Each player completed the questionnaire individually, without any group discussion. The authors exposed the main instructions before the players begin the completion of the same.

The initial part of the questionnaire comprised several sample descriptive variables such as the age the players begun the practice sport and the specific training of basketball, as well as the period of interruption between sporting seasons. The second part of the questionnaire assess the quantity and the type of sporting activities (specific and non-specific sports), as well as the average time spent in training at each developmental stage suggested by Stafford (2005) in its

| 13 proposal for late specialization sports as basketball, specifically: Fundamentals (FUN; between 6 and 10 years of age), Learning & Training to Train (TRAIN; 11 to 14 yr.), Training to Compete (COMPETE; 15 to 18 yr.) and Training to Win (WIN; 19 yr. and beyond).

Based on previous works (Almond, 1986), the sporting activities were categorized in four main categories: basketball, other team sports, individual sports and combat sports. These four sporting activities are mutually exclusive. When subjects refer to have practiced more than one of the four categories they were included in a fifth category labeled combination of several sports. At the same time, the players were questioned about the average time spent per week on these activities on each stage previously mentioned. The players reported the duration of their involvement using an ordinal scale, according to the suggestions of the authors of the questionnaire (Baker et al., 2003b), i.e., (i) no training during the developmental stage under examination; (ii) until 60 minutes; (iii) between 60 and 120 minutes; (iv) between 120 and 180 minutes; (v) between 180 and 240 minutes; (vi) between 240 minutes and 300 minutes; (vii) more than 300 minutes. The players were questioned about their participation on official competitions. This section of the questionnaire is made up of 16 items, 4 specific for each stage of development.

Consistency of retrospective information

Due to the nature of the data collected (based in retrospective information) and given the complexity and depth of the gathered information, the guidelines from the authors of the questionnaire were followed. The consistency and temporal stability of retrospective information were identified by re-testing 17 Portuguese (38%) and 9 USA (20%) players, approximately one month after completing it for the first time. The correspondence between the number of activities reported by the players at both time, points the percent agreement was computed (Bahrick, Hall & Berger, 1996). There was a high level of agreement (87%) between the information given by the players in both moments. To confirm validity, a sample of the

| 14 portuguese players’ parents (N = 9), was asked to describe the number and type of early activities and minutes of practice provided by the players (Baker et al., 2003b). There was also a high level of agreement (91%) between the total number of activities reported by the players and the total reported by their parents. The intraclass correlation coefficient for the number of practice minutes per week estimated by the player and the comparable estimate provided by their parent was r = .81. These results indicate that data validity and reliability is adequate.

Statistical Analysis

In order to test the hypothesis under study, Kruskal-Walls non parametric test was used to compare the players’ responses considering their playing position in the court (guards vs. forwards; guards vs. centers; and forwards vs. centers). The Mann-Whitney-U test was used to compare Portuguese and USA players, separately for each playing position. Bonferroni adjustments were applied to correct for multiple tests. Corresponding Cliff’s Delta effect sizes were also calculated (Macbeth, Razumiejczyk & Ledesma, 2011). All data was analyzed with SPSS for Windows, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and statistical significance was maintained at 5%.

Results

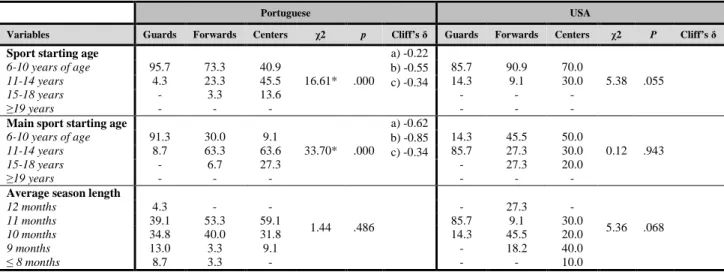

Table 1 describes the Portuguese and USA players sport starting ages, main sports starting ages and average season length. While most of the Portuguese guards and forwards started practicing sport between 6 and 10 years of age, centers revealed a close distribution between 6 and 10 years (40.9%) and between 11 and 14 years of age (45.5%). Significant

differences were found particularly between guards and centers (χ2 = 16.61, p< .05, ES = -0.55).

Further evidence supported this so-called later commitment to basketball training linked with centers, especially in the basketball starting age (χ2 = 37.3, p< .05, ES = -0.85).

| 15 The results of the sport activities experimented across the developmental stages are presented in Table 2. Main findings are focused in differences between centers and the other playing positions, especially in the time dedicated to training in the initial developmental stages. Inferential analyses revealed significant differences in both between 6 and 10 years of age and between 11 and 14 years of age, in which centers were outscored by guards and forwards. Higher effect sizes were detected in the initial stage (χ2 = 819, p< .05, ESguards vs. centers = 0.41,

ESforwards vs. centers = 0.39). No differences were found in the activities performed after 18 years of

age ( p> .05).

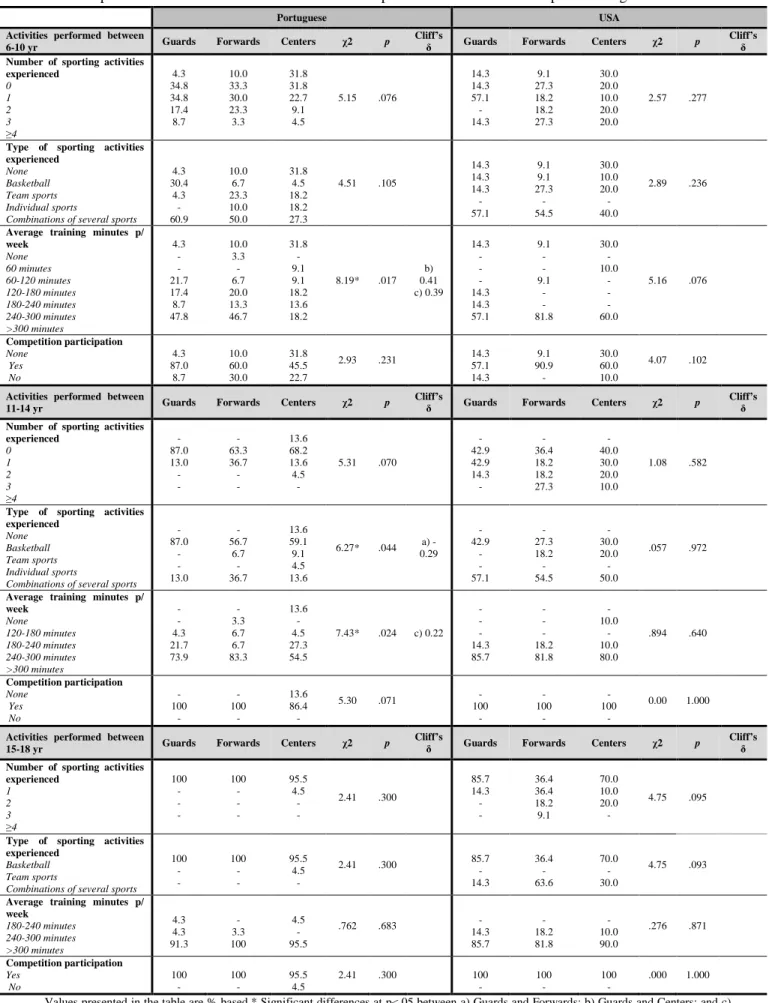

***Table 2 near here***

The summary of the results obtained in the comparison between Portuguese and USA players considering the playing position are presented in Table 3. Differences in the sport pathway are more evident in the activities performed between 11 and 14 years of age, especially the number and type of sports. While Portuguese players reduce their sport experiences after 11 years of age and focus in basketball training, USA players kept their involvement in a wide range of combined sports until 15 to 18 years of age. This differences of paths result in significant differences in all positions concerning the number of sporting activities experienced between 11 and 14 years of age; guards (z = -2.46, p< .05, ES = -0.46), forwards (z = -2.38, p< .05, ES = -0.38) and centers (z = -2.55, p< .05, ES = -0.53). This pattern of involvement in a range of sports (i.e., type of sporting activities) remains for USA players playing forward (z = -4.74, p< .01, ES = -0.44) and center (z = -2.09, p< .05, ES = -0.32) between 15 and 18 years.

***Table 3 near here***

Discussion and Conclusions

The objective of this study was two-folded: (i) on one hand, we aimed to describe the pathway of the Portuguese players according to their specific position; and on the other hand,

| 16 (ii) compare these pathways with the ones followed by the USA players playing in Portuguese high-performance teams.

Our results confirmed previous studies regarding the age of active start in sport as most of the players under examination (whether they are Portuguese or USA) engaged in sport between 6 and 10 years of age. These results are in accordance with previous research made with Portuguese team sports players (Leite et al., 2009). The guards seem to focus on basketball training earlier than the forwards, and especially, earlier than the centers. In fact, the guards and the forwards practiced more time than the centers in the early sport involvement, especially until 14 years of age. The results suggest that the players who handle the ball in elite basketball may play that specific role because they accumulated large quantities of training and for this reason they developed the skills needed to succeed. As mentioned by Sampaio et al. (2006), guards play a more demanding role from a cognitive standpoint, since they are responsible for coordinating the offensive set plays and tempo and, in certain cases, they also take decisions about the type of defense used play-by-play. Along these lines, Sidink (2011) studied the personality traits by players positions in Croatian top basketball league and showed that the guards have more diverse personalities that need individualized approach, in particular due to the more creative role in a team compared to forwards and centers. This argument can be related to more time of practice during early stages allow the guards to improve their decision-making and creative tasks.

The choice of playing in a given position can also be related with anthropometric advantages or body weight (Dežman, et al., 2001), however, there are several reported cases internationally were the guards overcome the centers in height and/or wingspan, and the taller players have better ball handling skills than guards or forwards. This argument is in accordance with Trninić, Papić, Trninić, and Vukičević (2008), when stating that the process to players’ quality needs to consider what and how many tasks they can perform and not only their player position demands. Besides, Trninić, et al., (2000, p.464) pointed out that “the expert experience

| 17 suggests that successful specialized players satisfy the most important criteria for a position, while universal, versatile players satisfy greater number of criteria for more positions”.

Another finding that stands out in the comparison between playing positions is the difference in type of sports practiced across the initial stages. The guards reported that involvement in other team sports besides basketball was more common, while centers mentioned a more diversified practice including participation in individual sports. These results are in accordance with Memmert, et al., (2010), when they state that more creative players accumulated more time of practice during their careers than the less creative. In fact, the guards are the more creative role in a team (Sidink, 2011). Probably, the results found may explain that the guards spent more practice in different across the initial stages than the other playing positions. On the other hand, Trninić, et al. (2008) suggested four procedures that coaches should be use to players’ recruitment and for a high expert approach for each specific position: detection (during young age), recognition (identification of players during formative stages), and orientation and selection procedures related to assessment of player’ potential and their actual quality in a particular formative stage. These authors pointed out, that during the first stages the coaches should aim to identify the relevant abilities, tasks and characteristics due to their nature of being the crucial precondition for the recognition and orientation of players into team sports, as well as for training plans that were focused on players proficiency enhancement for specific tasks and roles during the game. However, the present results do not clarify whether this type of experiences (in sports that share functional structure, like the team sports in which occurs an invasion of the opposite territory) influenced the players pathway or even the option for a given playing position. Recent studies are bringing light about this hypothetical transfer of skills between sports, mainly cognitive aspects (Abernethy, Baker & Côté, 2005; Memmert et al., 2010) but numerous questions remain unanswered, such as that the transfer of pattern recall skills needs to be studied with large samples of both, expert and novice players, and the studies must include a more precisely matched control groups.

| 18 The limited vacancies for foreign nationality players force coaches and managers to select players with high-level technical and/or tactical skills or morphological traits above the team’s average. One particular study (Harbili et al., 2011) analyzed the importance of players’ recruitment in Turkish basketball league and showed that international players had higher efficacy ratings than Turkish players. However, no significant effects in efficacy ratings were found when players’ position and nationality factors were studied. Thus, the process that leads to the final selection acquires special importance where every detail could be critical, including aspects that are often not as valued as career stats or milestones like the sport pathway followed by the players. Additionally, patterns of early involvement may provide valuable information that should help establishing a more comprehensive view of the path to expertise in basketball players and also to reinforce the importance of a longitudinal follow-up to the youngsters. The sport starting age, basketball starting age and average season length did not to differentiate between Portuguese and USA players. Unsurprisingly, no significant differences were found in the activities performed after the access to the senior age (i.e., 18 years of age), especially considering the requirements at this level competitive are maximal and require a high volume of training to prepare for competitions. Still, we are aware that the ordinal scale used in our study (from 60 to 300 minutes per week) may not be sensitive enough to make differences emerge between players. However, the number and type of sports practiced in all stages prior to the senior age - between 6 and 10 years, 11 and 14 and 15 and 18 years of age presented significant differences between Portuguese and USA players. Indeed, USA players reported a higher number of sports practiced, essentially combinations of different types of sports. Among these results, differences in forwards and centers found between 15 and 18 years of age (even with a medium effect size) were considerable. This may suggest that the Portuguese expert policies favor a more premature specialization, while the USA players are encouraged to maintain a diversification approach until older ages. In particular, Powers, Conway, McKenzie, Sallis, and Marshall (2002) studied 24 middle schools in San Diego (California, United States), and their

| 19 results showed that all schools offered multiple extracurricular sport activities, but the activities in which more students were commonly involved were traditional competitive sports that attracted more those students with advanced motor skills (i.e., basketball, track and field, soccer, tennis, and football). Then, the USA players’ practice presents a participation in a wide variety of sports during early stages that may continue with those sports that better fit with their physical and motor characteristics.

According to the results of this study, Portuguese players tend to experience a progressive specificity of training basketball at an early age and maybe limit the youngsters’ development and lead them to a monotonic development of specific characteristics of a given playing position. One of the most interesting findings of this study is the confirmation that a strategy based in diversification approach until older ages does not limit access to higher competitive levels. On the contrary, it apparently contributed to develop the training repertoire required to succeed at that level.

In sum, the results suggest that the initial approach should be direct towards a more comprehensive development of the physical literacy. Several authors suggest that this approach may allow a better acquisition and consolidation fundamental techniques and cognitive skills (Stafford, 2005; Elferink-Gemser, Visscher, Lemmink, & Mulder, 2007; Leite & Sampaio, 2010). Memmert et al. (2010) reinforce this long-term strategy with benefits in creative thinking in players, by passing the mechanical and stereotypical side that is sometimes provided in the training structure.

The present study emphasized the heterogeneity of sport path of Portuguese players, which seems to lead them to a higher specificity, what probably limited them to a more selective orientation to basketball. The distinct game competences manifested by the USA players in basketball may be the outcome of a strategy that guides the players to later sport specificity. It is also important not to forget that cultural factors contribute and influence sport policies and that

| 20 in the Portuguese case the structure and demands of the youth competitions may be responsible for a growing specialization.

References

Abernethy, B., Baker, J., & Côté, J. (2005). Transfer of pattern recall skills may contribute to the development of sport expertise. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 19, 705-718.

Almond, L. (1986). Reflection on themes: A games classification. In: Thorpe, R., Bunker, D. & Almond, L. (Eds.), Rethinking games teaching (pp.71-72). University of Technology, Loughborough.

Bahrick, H., Hall, L., & Berger, S. (1996). Accuracy and distortion in memory for high school grades. Psychological Science, 7, 265-271.

Baker, J. (2003). Early Specialization in youth sport: a requirement for adult expertise?. High Ability Studies, 14 (1), 85-94.

Baker, J., Côté, J., & Abernethy, B. (2003). Learning from the experts: Practice activities of expert decision-makers in sport. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 74, 342-347.

Baker, J. & Horton, S. (2004). A review of primary and secondary influence on sport expertise. High Abilities Studies, 15(2), 211-226.

Baker, J., Horton S., Robertson-Wilson J., & Wall M. (2003). Nurturing sport expertise: factors influencing the development of elite athlete. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 2, 1-9.

Côté, J., Baker J., & Abernethy B. (2007). Practice and play in the development of sport expertise. In: Eklund R. & Tenenbaum G., (Ed.), Handbook of Sport Psychology, Hoboken (pp. 184-202). NJ: Wiley.

| 21 Côté, J., Lidor, R., & Hackfort D. (2009). ISSP Position Stand: To sample or to specialize?

Seven Postulates about youth sport activities that lead to continued participation and elite performance. USEP, 9, 7-17.

Dežman, B. Trninić, S., & Dizdar, D. (2001). Expert Model of decision-making system for efficient orientation of basketball players to positions and roles in the game-empirical verification. Collegium Antropologicum, 25, 141-152.

Elferink-Gemser M., Visscher C., Lemmink K., & Mulder T. (2007). Multidimensional performance characteristics and standard of performance in talented youth field hockey players: A longitudinal study. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(4), 481-489. Ericsson, K., Krampe, R., & Tesch-Römer C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the

acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100, 363-406.

Ford, P., De Ste Croix, M., Lloyd, R., Meyers, R., Moosavi, M., Oliver, J., et al. (2011). The Long-Term Athlete Development model: Physiological evidence and application. Journal of Sports Science, 29(4), 389-402.

Harbili, E., Harbili, S., & Yalçin, C. (2011). Comparison of efficiency ratings of Turkish and International basketball players playing in the Turkish basketball league according to their positions. World Applied Science Journal, 14, 745-749.

Leite, N., Baker, J., & Sampaio, J. (2009). Paths to expertise in Portuguese national team players. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 8, 560-566.

Leite, N. & Sampaio, J. (2010). Early Sport involvement in young Portuguese basketball players. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 111 (3), 669-680.

Macbeth, G., Razumiejczyk, E., & Ledesma, D. (2011). Cliff’s Delta Calculator: A non-parametric effect size program for two groups of observations. Universitas Psychologica, 10 (2), 545-555.

Memmert, D., Baker, J., & Bertsch, C. (2010). Play and Practice in the development of sport-specific creativity in team ball sports. High Ability Studies, 2, 3-18.

| 22 Powers, S., Conway, L., McKenzie, L., Sallis, F., & Marshall, J. (2002). Participation in

extracurricular physical activity programs at middle schools. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 73 (2), 187-192.

Sampaio, J., Janeira, M., Ibáñez, S. & Lorenzo, A. (2006). Discriminant analysis of game-related statistics between basketball guards, forwards and centres in three Professional leagues. European Journal of Sport Science, 6 (3), 173-178.

Sindik, J. (2011). Differences between top senior basketball players from different team positions in big five personality traits. Acta Kinesiologica, 2, 31-35.

Stafford, I. (2005). Coaching for long-term athlete development: to improve participation and performance in sport. The National Coaching Foundation. Leeds, UK.

Trninić, S. & Dizdar, D. (2000). System of the performance evaluation criteria weighted per positions in the basketball game. Collegium Antropologicum, 24, 217-234.

Trninić, S., Dizdar, D., & Dežman, B. (2000). Empirical verification of the weighted system of criteria for the elite basketball players quality evaluation. Collegium Antropologicum, 24, 443-455.

Trninić, S., Papić, V., Trninić,V., & Vukičević, D. (2008). Player selection procedures in team sports games. Acta Kinesiologica, 2, 24-28.

Ziv, G. & Lidor, R. (2009). Physical attributes, physiological characteristics, on-court performances and nutritional strategies of female and male basketball players. Sports Medicine, 9 (7), 547-568.

| 23

Table 1. Descriptive and inferential statistics for long-term development variables.

Portuguese USA

Variables Guards Forwards Centers χ2 p Cliff’s δ Guards Forwards Centers χ2 P Cliff’s δ

Sport starting age 6-10 years of age 11-14 years 15-18 years ≥19 years 95.7 4.3 - - 73.3 23.3 3.3 - 40.9 45.5 13.6 - 16.61* .000 a) -0.22 85.7 14.3 - - 90.9 9.1 - - 70.0 30.0 - - 5.38 .055 b) -0.55 c) -0.34

Main sport starting age 6-10 years of age 11-14 years 15-18 years ≥19 years 91.3 8.7 - - 30.0 63.3 6.7 - 9.1 63.6 27.3 - 33.70* .000 a) -0.62 14.3 85.7 - - 45.5 27.3 27.3 - 50.0 30.0 20.0 - 0.12 .943 b) -0.85 c) -0.34

Average season length 12 months 11 months 10 months 9 months ≤ 8 months 4.3 39.1 34.8 13.0 8.7 - 53.3 40.0 3.3 3.3 - 59.1 31.8 9.1 - 1.44 .486 - 85.7 14.3 - - 27.3 9.1 45.5 18.2 - - 30.0 20.0 40.0 10.0 5.36 .068 Values presented in the table are % based.

| 24

Table 2. Descriptive and inferential statistics for the activities performed across the developmental stages.

Portuguese USA

Activities performed between

6-10 yr Guards Forwards Centers χ2 p

Cliff’s

δ Guards Forwards Centers χ2 p

Cliff’s

δ

Number of sporting activities experienced 0 1 2 3 ≥4 4.3 34.8 34.8 17.4 8.7 10.0 33.3 30.0 23.3 3.3 31.8 31.8 22.7 9.1 4.5 5.15 .076 14.3 14.3 57.1 - 14.3 9.1 27.3 18.2 18.2 27.3 30.0 20.0 10.0 20.0 20.0 2.57 .277

Type of sporting activities experienced

None Basketball Team sports Individual sports

Combinations of several sports 4.3 30.4 4.3 - 60.9 10.0 6.7 23.3 10.0 50.0 31.8 4.5 18.2 18.2 27.3 4.51 .105 14.3 14.3 14.3 - 57.1 9.1 9.1 27.3 - 54.5 30.0 10.0 20.0 - 40.0 2.89 .236

Average training minutes p/ week None 60 minutes 60-120 minutes 120-180 minutes 180-240 minutes 240-300 minutes >300 minutes 4.3 - - 21.7 17.4 8.7 47.8 10.0 3.3 - 6.7 20.0 13.3 46.7 31.8 - 9.1 9.1 18.2 13.6 18.2 8.19* .017 b) 0.41 c) 0.39 14.3 - - - 14.3 14.3 57.1 9.1 - - 9.1 - - 81.8 30.0 - 10.0 - - - 60.0 5.16 .076 Competition participation None Yes No 4.3 87.0 8.7 10.0 60.0 30.0 31.8 45.5 22.7 2.93 .231 14.3 57.1 14.3 9.1 90.9 - 30.0 60.0 10.0 4.07 .102

Activities performed between

11-14 yr Guards Forwards Centers χ2 p

Cliff’s

δ Guards Forwards Centers χ2 p

Cliff’s

δ

Number of sporting activities experienced 0 1 2 3 ≥4 - 87.0 13.0 - - - 63.3 36.7 - - 13.6 68.2 13.6 4.5 - 5.31 .070 - 42.9 42.9 14.3 - - 36.4 18.2 18.2 27.3 - 40.0 30.0 20.0 10.0 1.08 .582

Type of sporting activities experienced

None Basketball Team sports Individual sports

Combinations of several sports - 87.0 - - 13.0 - 56.7 6.7 - 36.7 13.6 59.1 9.1 4.5 13.6 6.27* .044 a) -0.29 - 42.9 - - 57.1 - 27.3 18.2 - 54.5 - 30.0 20.0 - 50.0 .057 .972

Average training minutes p/ week None 120-180 minutes 180-240 minutes 240-300 minutes >300 minutes - - 4.3 21.7 73.9 - 3.3 6.7 6.7 83.3 13.6 - 4.5 27.3 54.5 7.43* .024 c) 0.22 - - - 14.3 85.7 - - - 18.2 81.8 - 10.0 - 10.0 80.0 .894 .640 Competition participation None Yes No - 100 - - 100 - 13.6 86.4 - 5.30 .071 100 - - - 100 - - 100 - 0.00 1.000

Activities performed between

15-18 yr Guards Forwards Centers χ2 p

Cliff’s

δ Guards Forwards Centers χ2 p

Cliff’s

δ

Number of sporting activities experienced 1 2 3 ≥4 100 - - - 100 - - - 95.5 4.5 - - 2.41 .300 85.7 14.3 - - 36.4 36.4 18.2 9.1 70.0 10.0 20.0 - 4.75 .095

Type of sporting activities experienced

Basketball Team sports

Combinations of several sports 100 - - 100 - - 95.5 4.5 - 2.41 .300 85.7 - 14.3 36.4 - 63.6 70.0 - 30.0 4.75 .093

Average training minutes p/ week 180-240 minutes 240-300 minutes >300 minutes 4.3 4.3 91.3 - 3.3 100 4.5 - 95.5 .762 .683 - 14.3 85.7 - 18.2 81.8 - 10.0 90.0 .276 .871 Competition participation Yes No 100 - 100 - 95.5 4.5 2.41 .300 100 - 100 - 100 - .000 1.000

Values presented in the table are % based.* Significant differences at p<.05 between a) Guards and Forwards; b) Guards and Centers; and c) Forwards and Centers

| 25

Table 3. Inferential statistics for the comparison between Portuguese and USA players.

GuardsPOR vs. GuardsUSA ForwardsPOR vs. ForwardsUSA CentersPOR vs. CentersUSA

Variables z p Cliff’s δ Z p Cliff’s δ z P Cliff’s δ

Sport starting age -1.06 .081 -1.21 .228 -1.65 .099

Main sport starting age -1.38 .101 0.00 1.00 -1.79 .073

Average season length -1.78 .074 -0.32 .751 -2.14 .032 -0.25

Activities performed between 6-10 yr

Type of sporting activities

experienced -2.04 .041 0.47 -0.03 .975 -0.17 .866

Competition participation -3.02 .003 0.56 -1.56 .118 -0.36 .722

Activities performed between 11-14 yr

Number of sporting activities

experienced -2.46 .014 -0.46 -2.38 .017 -0.38 -2.55 .011 -0.53

Type of sporting activities

experienced -2.38 .018 -0.44 -1.42 .156 -2.42 .016 -0.53

Activities performed between 15-18 yr

Number of sporting activities

experienced -1.81 .070 -4.72 .000 -0.44 -2.05 .040 -0.32

Type of sporting activities

experienced -1.81 .070 -4.74 .000 -0.44 -2.09 .037 -0.32

| 27

ARTIGO 2

INICIAÇÃO DESPORTIVA, ATIVIDADES PRÉVIAS E

ESPECIALIZAÇÃO NO TREINO DE FUTSAL EM PORTUGAL

| 29

INICIAÇÃO DESPORTIVA, ATIVIDADES PRÉVIAS E

ESPECIALIZAÇÃO NO TREINO DE FUTSAL EM PORTUGAL

Sara Santos1; João Serrano2; Jaime Sampaio1 e Nuno Leite11

Centro de Investigação em Desporto, Saúde e Desenvolvimento Humano (CIDESD), Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro: Vila Real, Portugal.

2

Universidade de Évora, Escola de Ciência e Tecnologia: Évora, Portugal.

Resumo

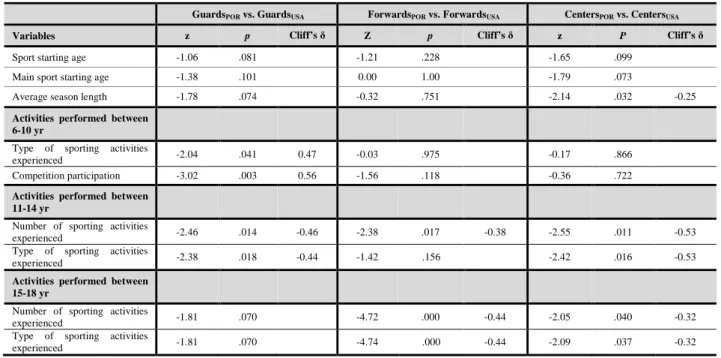

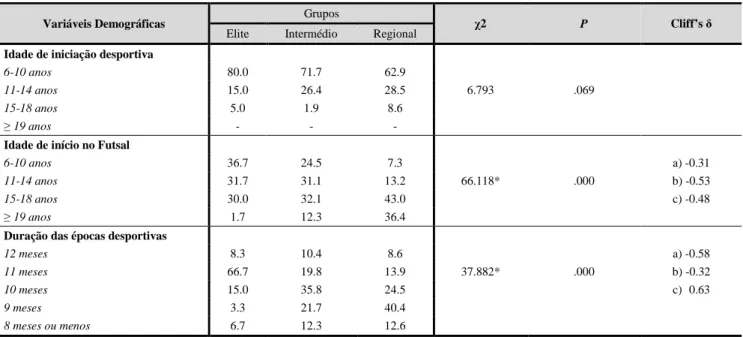

O presente estudo pretende analisar e caracterizar a preparação desportiva a longo prazo dos melhores jogadores de futsal portugueses. Para alcançar este objetivo, foram realizados dois estudos distintos. O estudo 1, permitiu averiguar o percurso desportivo de jogadores séniores provenientes de diferentes níveis competitivos, elite (n=60), intermédio (n=160) e regional (n=151). Por sua vez, o estudo 2, comparou o envolvimento desportivo inicial dos melhores jogadores portugueses (n=24), com aquele desenvolvido por jogadores mais jovens, selecionados para representar as equipas distritais (n=270) e contemplou adicionalmente, uma análise entre sexos. Todos os participantes preencheram um questionário previamente validado, que fornece informações de carácter retrospetivo sobre as atividades desportivas experienciadas ao longo da sua carreira.

Os resultados demonstraram, que os melhores jogadores se distinguem dos jogadores de níveis competitivos inferiores, pela dedicação mais precoce ao treino desportivo e especificamente ao futsal, facto que é reforçado, tanto pelo acréscimo progressivo do volume de treino semanal como na duração das épocas desportivas. Estes aspetos emergem como fatores discriminantes neste processo, e não deixando de referenciar, o contributo da prática diversificada no percurso dos melhores jogadores portugueses de futsal.

| 30

Abstract

The present study aimed to analyze and characterize the long-term athlete development in the elite Portuguese futsal players. There were performed two different studies to achieve this goal. The first one allowed to ascertain the route of seniors sports players from different competitive levels, elite (n=60), medium (N=160) and regional (n=151). The second study has compared the early involvement of the elite senior Portuguese players (n=24), with the study developed with young players, selected to represent the district teams (n=270) and also included a comparison between genders. All the participants completed a previous validated questionnaire, which provides retrospective information about the sport activities experienced throughout his career.

The results showed that the elite players are distinguished from lower level competitive players for their earlier dedication to the sports training and specifically to futsal, which is reinforced by the progressive increase in volume of weekly training as in the durations of seasons. These aspects emerge as discriminating factors in this process, whilst the early practice diversifications contribution to the course of the elite Portuguese futsal players.

| 31

Introdução

Uma análise retrospetiva do percurso percorrido pelos jogadores de elite durantes as diferentes etapas desportivas, poderia ajudar os especialistas da área de ciências do desporto e treinadores, a identificar os mecanismos subjacentes à aquisição da excelência desportiva. Este tipo de procedimento permite uma compreensão mais abrangente de padrões e indicadores

preditivos que podem facilitar e tornar exequível o desenvolvimento do expertise.

Consequentemente, a relevância do presente estudo, é especialmente justificada, porque ao nosso conhecimento não existem publicações que detalhem o percurso adotado pelos jogadores experts de futsal, e que assegurem uma informação qualitativa e quantitativa sobre este processo.

Nos últimos anos, numerosos estudos têm procurado identificar os fatores que mais

contribuem para a manifestação do expertise no desporto (WILLIAMS; HODGES, 2005).

Tradicionalmente, o termo expert é associado aos jogadores que já manifestam uma performance de alto nível, como resultado, de um processo longitudinal de aquisição e

desenvolvimento de habilidades diferenciadas no desporto específico e não específico (BAKER

et al., 2006).

Baker e Horton (2004) constataram a existência de influências primárias e secundárias que condicionam a obtenção do expertise, no primeiro grupo, são incluídos os fatores genéticos, treináveis e psicológicos, no entanto, as influências secundárias, abrangem os fatores

socioculturais e contextuais. Investigadores como Côté et al. (2005), acrescentam a existência de

períodos chave no desenvolvimento desportivo, e enfatizam que a participação numa ampla variedade de atividades desportivas, providencia o enriquecimento do reportório motor.

No seguimento desta abordagem, um modelo denominado por Long Term Athlete Development (LTAD), sustenta a importância de providenciar estímulos adequados durante os períodos sensíveis do desenvolvimento físico, comummente designados por “windows of opportunity”, que variam mediante a maturação biológica dos jovens jogadores (FORD et al.,

| 32 2011). Autores como Philippaerts et al. (2006), alertam para a importância de individualizar a carga de treino durante estes períodos críticos.

A caracterização da história desportiva ou do percurso adotado pelos jogadores experts, permite também, reformular e atualizar o processo de identificação de talentos, que deve possibilitar um acompanhamento longitudinal do desenvolvimento desportivo dos jogadores,

por este motivo, é que se constitui um processo dinâmico (ABBOT; COLLINS, 2004).

A seleção e identificação de talentos no futebol, futsal ou outros desportos, é um processo em constante evolução, cuja dinâmica tem despertado a atenção de vários autores (WILLIAMS; REILLY, 2000).De acordo com Reilly et al. (2000), a identificação de talentos é um processo mais complexo nos desportos coletivos, e particularmente no futebol, é percetível a importância dos fatores externos, como a oportunidade para a prática, a ausência de lesões, a qualidade da supervisão técnica providenciada por treinadores durante as etapas de desenvolvimento, mas também, devem ser considerados os fatores pessoais, sociais e culturais.

A revisão da literatura disponível sobre a história de desportistas de alto rendimento, revela basicamente duas linhas de orientação, a teoria da prática deliberada (i.e., estudos

realizados por ERICSSON et al., 1993; ERICSSON, 2004, ERICSSON, 2007), que enaltece a

importância do número de horas de prática desportiva específica, e quando associada a elevados níveis de motivação, resulta na aquisição de uma elevada performance. Uma abordagem distinta

e mais recente, denomina-se por prática diversificada (i.e., estudos realizados por BAKER,

2003; BAKER; HORTON, 2004; BAKER et al., 2003; BAKER et al., 2006), que salienta a

importância da prática complementar de diversas atividades desportivas durante as etapas iniciais, no entanto, devem possuir uma dinâmica semelhante à solicitada no desporto principal.

A prática diversificada, permite fomentar as habilidades fundamentais necessárias para a prática do desporto específico, providenciando, um contributo ativo, no que diz respeito ao desenvolvimento psicomotor e multilateral dos jovens jogadores. Vários estudos têm sido publicados, com o intuito de ajudar a esclarecer esta problemática (para refs. ver Leite et al.,

| 33

2009). Autores como Ward et al. (2007) analisaram o desenvolvimento a longo prazo dos

jogadores de alto rendimento de futsal, e os resultados não foram sustentados pela teoria da prática deliberada. O mesmo se constatou no estudo realizado por Leite et al. (2009), quando analisado o percurso de desportistas com uma elevada performance (hóquei em patins, futebol, basquetebol e voleibol), e verificaram uma tendência para a prática diversificada e não para uma

especialização, sugerindo a primeira como um caminho mais viável. Côté (1999), examinou as

etapas iniciais de desenvolvimento dos desportistas experts, e também constatou que a especialização precoce não parece ser essencial para obter elevadas performances durante as etapas de desenvolvimento subsequentes, ou seja, nos escalões posteriores já em adultos.

Investigadores como Memmert et al. (2010) possuem diversas reservas em relação à

teoria da prática deliberada, questionando a transferência que pode resultar do treino específico na criatividade tática dos jogos desportivos coletivos. De acordo, com Leite et al., (2009), as características comuns entre modalidades, estão relacionadas com a dinâmica repetitiva da tomada de decisão durante o jogo, dentro de um contexto com um espaço confinado que requer o desenvolvimento de habilidades de reconhecimento de padrões espaciais e um elevado grau de aptidão física. A participação em diferentes atividades aeróbias, pode providenciar efeitos cardiovasculares benéficos, melhorando a performance nos desportos que solicitam predominantemente, o sistema aeróbio.

Apesar dos avanços na última década no que concerne à preparação desportiva a longo prazo, a revisão da literatura mais recente apoia as constatações realizadas por Leite et al. (2009), quando referem que o desenvolvimento do expertise e a identificação de talentos no desporto continua a ser um importante tópico de debate. Sendo o futsal, um desporto coletivo relativamente recente na América do Sul (especialmente no Brasil), no Sul da Europa (enfatizando a Espanha, Itália e Portugal) e em alguns Países da Europa de Leste. Estes factos, podem justificar a reduzida referência a este desporto, em estudos de pesquisa Anglo-Saxônica ou da literatura Americana, onde são mais frequentes as referências ao futebol ou a outros tipos

| 34 de desportos indoor com elevada popularidade, como é o caso do basquetebol, voleibol ou andebol.

Em concordância com os aspetos salientados anteriormente, o estudo em questão, pretende analisar e caracterizar a preparação desportiva a longo prazo dos melhores jogadores de futsal portugueses. Para alcançar este objetivo, foram realizados dois estudos distintos: o primeiro, permitiu averiguar o percurso desportivo de jogadores séniores, provenientes de diferentes níveis competitivos (elite, intermédio e regional), e o segundo estudo, comparou o envolvimento desportivo inicial dos melhores jogadores portugueses (reconhecidos pela comissão técnica nacional) com o de jogadores mais jovens, selecionados para representar as equipas distritais.

Método

Considerando a definição de objetivos do presente trabalho optámos por iniciar este capítulo com as secções que são comuns a ambos os estudos e apresentar separadamente os participantes em cada um deles.

Procedimentos

A Comissão de Ética do Centro de Pesquisa em Ciências do Desporto, Saúde e Desenvolvimento Humano da Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro, providenciou a aprovação institucional para este estudo. Os participantes completaram um questionário previamente validado por Leite e colaboradores, utilizado em alguns estudos recentes dedicados a analisar o processo de aquisição de habilidades a longo prazo (LEITE et al., 2009; LEITE; SAMPAIO, 2010). Este instrumento visa obter informações detalhadas sobre a carreira desportiva dos jogadores, fornecendo um perfil longitudinal detalhado relativamente ao envolvimento em atividades desportivas específicas e não específicas realizadas pelos jogadores de jogos desportivos coletivos ao longo do seu trajeto desportivo.

| 35 A primeira parte do questionário foi dedicada a reunir informações que permitem uma caracterização demográfica da amostra em termos desportivos, contemplando a idade em que iniciaram a prática desportiva (idade de iniciação desportiva), a idade em que iniciaram a prática de futsal (idade de iniciação do futsal) e o número de meses aproximado de prática deliberada em cada época desportiva (duração da época).

A segunda parte do questionário avaliou o número e o tipo de atividades desportivas em que os jogadores participaram durante todo o seu envolvimento no desporto (número e tipo de desportos praticados), assim como a média de tempo despendido no treino semanalmente (média de tempo de treino semanal), variáveis estas, que foram analisadas em cada etapa de desenvolvimento. A divisão foi sugerida pelo modelo de Preparação Desportiva a Longo Prazo, proposto para os desportos de especialização tardia, como se verifica no futsal (STAFFORD, 2005), que especifica as seguintes etapas: Fundamentals (FUN; entre os 6 e os 10 anos de idade), Learning & Training to Train (TRAIN; dos 11 aos 14 anos), Training to Compete (COMPETE; dos 15 aos 18 anos) e Training to Win (WIN; com 19 ou mais anos).

No Estudo 2 foi adicionada uma questão com o intuito de averiguar o grau de compromisso dos jogadores com o treino:

“Para cada uma das três etapas de desenvolvimento da carreira desportiva (Fundamentals, Learning & Training to Train e Training to Compete), especifique se esteve presente: a) somente em competições; b) raramente comparecia às sessões de treino; c) apenas comparecia

a metade das sessões de treino; d) presente nas sessões de treino frequentemente; e) presente em todas as sessões de treino”.

Com base em trabalhos anteriores (ALMOND, 1986) que classificam as atividades

desportivas em quatro categorias principais: futsal, outros Desportos Coletivos, Desportos Individuais e Desportos de Combate, sendo que, estas quatro atividades desportivas são mutuamente exclusivas e quando os indivíduos relataram praticar mais do que uma destas quatro

| 36 categorias originais, foram incluídos numa quinta categoria denominada de Desportos Combinados.

Relativamente ao tempo semanal de treino, as respostas dos jogadores foram agrupadas utilizando a seguinte escala ordinal: 0, corresponde a nenhuma prática dentro da etapa de desenvolvimento em questão, 1 corresponde entre 1 a 3 horas; 2, corresponde entre 3 a 6 horas; 3, corresponde entre 6 a 9 horas; 4, corresponde a 10 ou mais horas. Esta escala ordinal foi escolhida porque é mais fácil para os jogadores recordarem a informação (por exemplo, se treinam entre 1 e 2 horas) do que saber exatamente quantos minutos foram treinados em cada etapa da sua preparação desportiva a longo prazo (LEITE et al., 2009). O preenchimento do questionário foi devidamente monitorado pelo investigador principal e foi realizado num ambiente tranquilo, antes ou após o treino, mas sempre depois de uma breve explicação.

Análise Estatística

Para testar as diferenças estatísticas entre as variáveis demográficas e de desenvolvimento a longo prazo, foi utilizado o teste não paramétrico Kruskall-Wallis. No entanto, para clarificar quais as diferenças que mais contribuíram para as diferenças significativas identificadas no teste anterior, foi utilizado o teste de Mann-Whitney U. Foram aplicados ajustamentos de Bonferroni para corrigir os ensaios múltiplos e também foi calculado

o efeito do tamanho através dos Cliff´s Delta (MACBETH, et al. 2011).

Para validar o tempo de prática por semana reportada pelos jogadores, foi utilizada uma correlação intraclasse, calculada através de uma estimativa do número de minutos referidos pelos jogadores e pelos seus pais (WEIR, 2005). Todos os dados foram analisados pelo SPSS para Windows, versão 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) e a significância estatística foi mantida em 5%.

| 37

Participantes (Estudo 1)

Trezentos e setenta e um jogadores séniores de futsal Portugueses participaram no estudo. Os jogadores foram agrupados de acordo com o nível competitivo em que estavam envolvidos quando foram contactados pela equipa de pesquisa: i) elite, representada por jogadores de equipas que nas últimas três temporadas (ou seja, entre 2007 e 2010), ficaram classificadas nos três primeiros lugares da primeira divisão nacional do campeonato português (n=60); ii) intermédio, composto por jogadores que competem na 2ª e 3ª divisão nacional (n=160); e iii) regional, representada por jogadores que participam nos campeonatos regionais de futsal (n=151).

Participantes (Estudo 2)

Duzentos e noventa e quatro jogadores portugueses de futsal participaram no estudo: foram recrutados 24 jogadores portugueses das equipas nacionais, reconhecidos pela comissão técnica nacional como os melhores jogadores na época de 2009-2010 (designados como grupo nacional e considerados jogadores de elite, idade 26.0 ± 3.6, experiência 14.3 ± 2.44), e 270 jovens jogadores que representam o distrito (grupo distrital). Até ao momento da pesquisa, os participantes incluídos neste grupo, composto por 169 rapazes e 101 raparigas, estavam a competir no campeonato Anual Inter-Associação na época de 2009-2010. Considerando o desenvolvimento heterogéneo deste desporto em todo o País e atendendo à respetiva estrutura social, económica e demográfica, decidimos dividir os 270 jogadores em dois grupos.

Os jogadores que representam os distritos que possuem uma maior representatividade em termos de número de equipas, que participam no campeonato nacional de futsal e possuem um elevado nível de desenvolvimento nesta modalidade (Lisboa, Porto, Braga, Leiria, Aveiro, Coimbra e Algarve) foram categorizados como grupo distrital A, eventualmente mais habilidosos (idade 18.3 ± 1.5, experiência 4.1 ± 2.6, n = 131). Os jogadores que representam os restantes distritos (Vila Real, Castelo Branco, Bragança, Setúbal, Guarda, Ponta Delgada,