RevPaulPediatr.2016;34(4):518---521

REVISTA

PAULISTA

DE

PEDIATRIA

www.rpped.com.br

CASE

REPORT

Bilateral

spontaneous

chylothorax

after

severe

vomiting

in

children

Antonio

Lucas

Lima

Rodrigues

a,∗,

Mariana

Tresoldi

das

Neves

Romaneli

b,

Celso

Dario

Ramos

b,

Andrea

de

Melo

Alexandre

Fraga

b,

Ricardo

Mendes

Pereira

b,

Simone

Appenzeller

b,

Roberto

Marini

b,

Antonia

Teresinha

Tresoldi

baHospitaldeClínicasdaUniversidadeEstadualdeCampinas(Unicamp),Campinas,SP,Brazil

bFaculdadedeCiênciasMédicasdaUniversidadeEstadualdeCampinas(Unicamp),Campinas,SP,Brazil

Received11January2016;accepted24March2016 Availableonline20August2016

KEYWORDS Chylothorax; Vomiting; Thoracicduct; Scintigraphy; Child

Abstract

Objective: Toreportthecaseofachildwithbilateralchylothoraxduetoinfrequentetiology: thoracicductinjuryafterseverevomiting.

Casedescription: Girl,7 years old, with chronic facial swelling started after hyperemesis. During examination, she also presented with bilateral pleural effusion, with chylous fluid obtained duringthoracentesis. After extensive clinical,laboratory,and radiological investi-gationofthechylothoraxetiology,itwasfoundtobesecondarytothoracicductinjurybythe increasedintrathoracicpressurecausedbytheinitialmanifestationofvomiting,supportedby lymphoscintigraphyfindings.

Comments: Except for the neonatalperiod, chylothorax isan infrequent finding ofpleural effusioninchildren.Therearevariouscauses,includingtrauma,malignancy, infection,and inflammatorydiseases;however,theetiologydescribedinthisstudyispoorlyreportedinthe literature.

©2016SociedadedePediatriadeS˜aoPaulo.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Quilotórax;

Vômito; Ductotorácico; Cintilografia; Crianc¸a

Quilotóraxbilateralespontâneoapósvômitosexcessivosemcrianc¸a

Resumo

Objetivo: Relatar ocaso deuma crianc¸a comquilotórax bilateral devidoa etiologiapouco frequente:lesãodoductotorácicoapósquadrodevômitosexcessivos.

Descric¸ãodocaso: Menina,seteanos,apresentavaedemafacialcrônicoiniciadoapósquadro dehiperemese.Àavaliac¸ão,tambémapresentavaderramepleuralbilateral,comlíquidoquiloso

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:antoniollrodrigues@yahoo.com.br(A.L.Rodrigues).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rppede.2016.04.003

Bilateralspontaneouschylothoraxafterseverevomitinginchildren 519

obtidonatoracocentese.Apósextensainvestigac¸ãoclínica,laboratorialeradiológicada etiolo-giadoquilotórax,foidefinidosersecundárioalesãodoductotorácicoporaumentodapressão intratorácicapela manifestac¸ãoinicial devômitos,corroborado porachadosde linfocintilo-grafia.

Comentários: À excec¸ão doperíodo neonatal,o quilotóraxéachado infrequente deefusão pleuralemcrianc¸as.Ascausassãodiversas,incluindotrauma,neoplasia,infecc¸ãoedoenc¸as inflamatórias;contudo,etiologiacomoaaquidescritaépoucorelatadanaliteratura. ©2016SociedadedePediatriadeS˜aoPaulo. PublicadoporElsevier EditoraLtda.Este ´eum artigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Introduction

Chylothoraxisdefinedaslymphaccumulationinthepleural space,caused byinjurytothethoracic ductandis arare causeof pleuraleffusion in children.1,2 Itcan leadto

sig-nificant respiratory morbidityand hasan extensive listof causes,withgreatdiagnosticdifficulty.1,2Thisstudyaimsto

reportthecase of achild withspontaneousbilateral chy-lothorax.

Case

description

Seven-year-oldwhitefemalepatient,referreddue to sus-pecteddiagnosisofsystemiclupuserythematosus.Shehad a five-month history of sudden-onset vomiting and self-limitedabdominalbloatingafteringestionoflargeamounts of chocolate; subsequently, she started to show insidious andpermanentchronicswellingofface.Threemonthsafter symptom onset and extensive evaluation of allergies,she was submitted to a chest and abdomen computed tomo-graphy, which showed abdominal lymphadenomegaly and bilateralpleuraleffusion.Chestdrainagewasperformedin anotherserviceandthepresenceofmilkypleuralfluidwas reported.Shealsounderwentlaboratory evaluationat the original service andmost results werewithin normal val-ues (includingwholeblood count, renalfunction, C3, C4, rheumatoidfactor,anti-Sm,anti-Ro,anti-La,anti-ds-DNA),

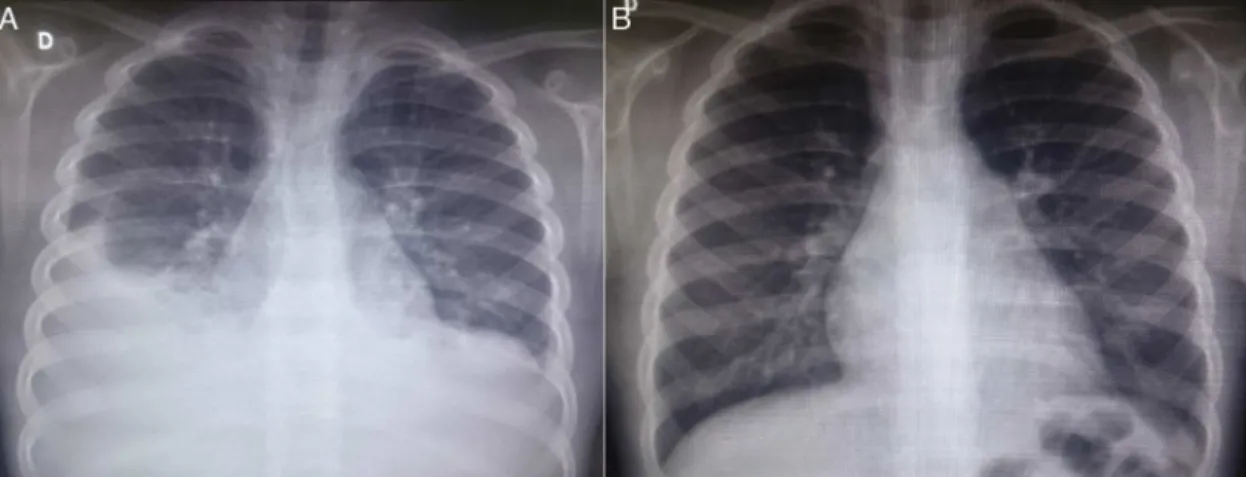

Figure1 Chestradiographyimagesofthepatientintheposteroanteriorview;A---atpatientadmission,costophrenicsinus oblit-erationis observedbilaterally,with pleuropulmonary opacityto theright;B---six months afterdischarge, duringanoutpatient consultation,theradiographyshowsnoalterations.

exceptforapositiveantinuclearantibody,atatitrationof 1:640,nuclearspeckledpattern.

At the firstoutpatient visit in ourservice, thepatient underwentanewchestradiography(Fig.1A),whichshowed recurrenceofbilateralpleuraleffusion.Athoracentesiswas performedontheright,ofwhichmilkywhitefluidshowed thepresenceof1.120mm3ofleukocytes(96%lymphocytes,

3%neutrophils,1%plasmacells);710mm3ofredbloodcells;

3.7g/dL of protein; 87mg/dL of Glucose; 2.855mg/dL of triglycerides. The child was hospitalized, kept in fasting andstartedparenteralnutritiontherapy.After21days with-outreductioninthechylothoraxvolume,bilateralthoracic drainagewasperformedand450mLofchyloussecretionwas removedfromtheright and300mLfromtheleftside.The drainsweremaintainedinwaterseal,withamarked reduc-tionineyelidedema.Threedaysafterthedrainingshewas startedonalow-fatdiet.Thedrainswereremovedafter25 days.

520 RodriguesALetal.

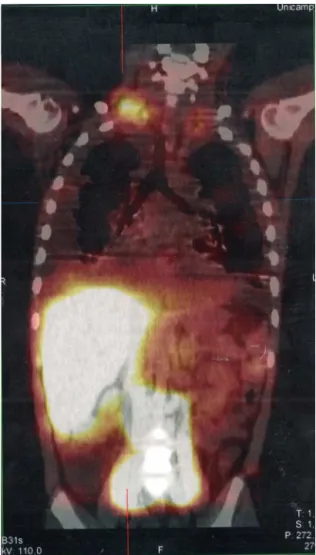

Figure2 SPECT/CTimageofthecervicothoracicand abdom-inalregionsobtainedfromthelymphoscintigraphyassessment withintradermaladministrationofdextran-99mTconthe dor-sumofthefeet;theimagesobtained18hoursafterstartofthe examinationshowfocalareaofradiotracerretention/leakage inthelymphducts locatedinthetopographyofthethoracic introit,bilaterally,moreaccentuatedtotheright.

toincreasedintracavitarypressurecausedbyvomitingthat occurredatthebeginningoftheclinicalpicture.Thepatient wasdischargedafter53 daysofhospitalstay,with outpa-tientfollow-up,duringwhichshewasallowedtoresumea normaldietwithoutlipidrestrictions.Sheremains asymp-tomaticat the follow-up (control chest X-ray in Fig. 1B), withoutalterationsinthelaboratorytests,including evalu-ationbyarheumatologist.

Discussion

The clinical picture of a patient with chylothorax is insidious and develops as fluid accumulates in the pleu-ral cavity; asymptomatic at first, it then progresses with cough and dyspnea1,2; fever and pleuritic pain are

rare findings.2,3 On physical examination, there is

unilat-eral or bilateral dullness and decreased breath sounds.3

Complications of a chylothorax with chronic evolution

include protein-calorie malnutrition, immune deficiency by lymphocyteand immunoglobulin depletion1,4 and

elec-trolytedisorders.5

The diagnosis, based on clinical suspicion in patients with suggestive clinical picture and compatible radiolog-ical findings (pleural effusion in the plain chest X-ray or ultrasound),is attainedthroughthe thoracocentesis.1,3

The fluid removed from the pleural cavity is white, odorless, milky white,2,3 but can be as serosanguinous.3

Laboratoryevaluationshowedtriglyceridelevelsinthe sam-ple above of 110mg/dL and cholesterol ratio of pleural fluid over serum<1.0.1,3 Usually, cellularity is

predomi-nantly comprised of lymphocytes (>50%), with a protein contentbetween2and 3mg/dL5and lowlevelsoflactate

dehydrogenase.3,5Ifthediagnosticdoubtpersists,the

pre-ferredmethodischylomicronanalysisinthebiologicalfluid, withapositiveresult.1,3

Afterdiagnostic confirmation, one can use other tests to help in the investigation, such as computed tomogra-phy and/or magnetic resonance imaging,aswell asmore specificteststoevaluatethelymphaticsystem,suchas lym-phangiographyandlymphoscintigraphy.1,2 Accordingtothe

locationofthethoracicductrupture,whilealsoconsidering theanatomicalvariations,unilateralcollection(most com-monlyontheright)canbedetectedor,morerarely,bilateral (inone-sixthofcases).5

Thecausesofchylothoraxinchildrenarediverse,varying according toage andthethoracicductlesion mechanism. A reviewpublished in2014 reports morethan 35 possible etiologies.1 Among these arecongenital malformations of

the lymphatic system, such as pulmonary lymphangioma, lymphangiectasiaandthoracicductatresia1,2,6;chylothorax

associated with genetic syndromes, such as Down, Noo-nan and Turner syndrome,6 among others1,6; after head

andneck andthoracic surgicalprocedures (inupto6% of cardiac surgeries)1,7; after other iatrogenic events in the

neonatal period, such as birth trauma and superior vena cava thrombosis due to central venous catheterization5,6;

chylothorax after closed thoracic trauma1; and

chylotho-rax associatedwith cancer,such asneurogenic neoplasia, teratomas, sarcomas and especially lymphomas, in which the lymph accumulation in the pleural space may be the initialmanifestation,1,2inadditiontogranulomatous

infec-tionssuchastuberculosis.1Thepatientinthiscasedidnot

havefindingsthatwereconsistentwithcongenital malfor-mations,hadnotsufferedtraumaorsurgery,whereascancer and infections were ruled out. Other possible causes for the development of chylothorax are the rheumatological ones,theinitialreasonwhyourpatientcametotheservice. Possible triggers that have been described are systemic lupuserythematosus,8Behc¸et’sdisease,9Henoch---Schönlein

purpura10 and sarcoidosis.11 Likewise, thepatient showed

no clinical and laboratory criteria for these conditions before or during the follow-up, which were then ruled out.

Anotherconditionruledoutinthiscasewas lymphangi-oleiomyomatosis.Itisararediseasethatcanbeassociated with the tuberous sclerosis complex, is characterized as low-grademetastasizingneoplasm,whichleadstoinsidious cysticchangesinthelungparenchymaandalsoaffectsthe lymphvesselsandlymphnodesandleadstochylothorax.12

diag-Bilateralspontaneouschylothoraxafterseverevomitinginchildren 521

nosis in thiscase, asthemarker is present at high levels in most patients and it is considered reliable for the diagnosis and evaluationof therapeutic response in these cases.12,13

Therefore,afterexcludingallpossibilities,theremaining cause was considered for the onset of chylothorax in a child: increased intrathoracic pressure caused by exces-sivecoughingorvomiting.1Thisconditionisassociatedwith

diseases suchasBoerhaaveandMallory---Weisssyndromes, pneumothorax and subcutaneous emphysema.14 However,

theassociationofthisconditionwiththoracicductrupture israrelydescribed---thereisonereportofanine-year-oldgirl withchylothoraxafterexcessivevomiting14 andtwoadults

(33and65)withtheonsetoflymphaticpleuraleffusionafter coughingepisodes.15,16Consideringthehistoryofexcessive

vomiting and abrupt symptom onset, this cause could be inferredinthepresentcase.However,contrarytoreportsin theliterature,thelymphaticlesioninthepatientdescribed hereoccurredatthethoracicintroitlevelandnotnearthe diaphragm.2,15

The treatment of chylothorax after thoracentesis and eventualchest drainageis initiallyconservative,basedon afat-freedietwithadditionofmedium-chaintriglycerides, whichareabsorbeddirectlyintotheportalcirculation.1,2,7

Ifthe enteraldiet fails or as afirst optional choice, par-enteralnutritioncan beused.2,7 Adjuvanttherapies, such

asuseofoctreotide,5,7stillneedmoresupportinthe

litera-turefortreatmentinchildren.1Duetoothercomplications,

suchashypogammaglobulinemiaand theincreasedriskof thrombosis(duetothelossofantithrombin),someauthors have recommended the use of intravenous immunoglob-ulin and anticoagulation, according to each case.7 The

listofoptionsforthesurgicaltreatment includesthoracic ductligation bythoracoscopy,pleurodesis and pleuroperi-toneal shunts; however, these approaches, as a rule, are reserved for patients who do not respond to the initial medicaltreatment (noimprovement after2---4 weeks and maintenanceof high drainageoutput).1,2,5,7 In additionto

thesespecifictherapies,eventual basalconditionssuchas malignancyorinfectionshouldbeassessed,forbettercase resolution.5

Although it is a rare cause of pleural effusion in chil-dren (except for the neonatal period),1,6 chylothorax can

resultin significant morbidity inthese patients.This case illustrates the difficulty of clarifying the diagnosis of the chylothoraxcause and serves asa reminder that,despite a number of other diseases that are more often associ-atedwiththisentity,thoracicductinjuryduetoincreased intrathoracicpressurecausedbysignificantcoughingand/or vomitingshouldalsobeincludedinthedifferential diagno-sis.

Funding

Thisstudydidnotreceivefunding.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.Tutor JD. Chylothorax in infants and children. Pediatrics. 2014;133:722---33.

2.Soto-MartinezM,MassieJ.Chylothorax:diagnosisand manage-mentinchildren.PaediatrRespirRev.2009;10:199---207.

3.Skouras V, Kalomenidis I. Chylothorax: diagnostic approach. CurrOpinPulmMed.2010;16:387---93.

4.KovacikovaL,LakomyM,SkrakP,CingelovaD.Immunologic sta-tusinpediatriccardiosurgicalpatientswithchylothorax.Bratisl LekListy.2007;108:3---6.

5.McGrath EE, Blades Z,Anderson PB. Chylothorax:aetiology, diagnosisandtherapeuticoptions.RespirMed.2010;104:1---8.

6.RochaG.Pleuraleffusionsintheneonate.CurrOpinPulmMed. 2007;13:305---11.

7.Panthongviriyakul C,Bines JE. Post-operativechylothorax in children:anevidence-basedmanagementalgorithm.JPaediatr ChildHealth.2008;44:716---21.

8.LinYJ,ChenDY,LanJL,HsiehTY. Chylothoraxastheinitial presentationofsystemiclupuserythematosus:acasereport. ClinRheumatol.2007;26:1373---4.

9.ZhangL,ZuN,LinB,WangG.Chylothoraxandchylopericardium in Behc¸et’s diseases: casereportand literaturereview. Clin Rheumatol.2013;32:1107---11.

10.CogarBD, GroshongTD,TurpinBK,GuajardoJR.Chylothorax inHenoch---Schonleinpurpura:acasereportandreviewofthe literature.PediatrPulmonol.2005;39:563---7.

11.SoskelNT,SharmaOP.Pleuralinvolvementinsarcoidosis.Curr OpinPulmMed.2000;6:455---68.

12.Xu KF, Lo BH. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis: differential diag-nosis and optimal management. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014;10:691---700.

13.Young L, Lee HS, Inoue Y, Moss J, Singer LG, Strange C, etal. SerumVEGF-D aconcentrationasa biomarkerof lym-phangioleiomyomatosis severity and treatment response: a prospectiveanalysisoftheMulticenterInternational Lymphan-gioleiomyomatosis Efficacy of Sirolimus (MILES) trial. Lancet RespirMed.2013;1:445---52.

14.YekelerE,UlutasH.Bilateralchylothoraxafterseverevomiting inachild.AnnThoracSurg.2012;94:e21---3.

15.AdasG,KaratepeO, BattalM,DoganY, KaryagarS,KutluA. Coughing may lead to spontaneous chylothorax and chylous ascites.CaseRepGastroenterol.2007;1:178---83.