ww w . r e u m a t o l o g i a . c o m . b r

REVISTA

BRASILEIRA

DE

REUMATOLOGIA

Original

article

The

representation

of

getting

ill

in

adolescents

with

systemic

lupus

erythematosus

夽

Ondina

Lúcia

Ceppas

Resende

a,b,∗,

Maria

Tereza

Serrano

Barbosa

c,d,

Bruno

Francisco

Teixeira

Simões

d,e,

Luciane

de

Souza

Velasque

d,faUniversidadeFederaldoEstadodoRiodeJaneiro(UNIRIO),RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil bHospitalFederaldosServidoresdoEstado,RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil

cUniversidadedoEstadodoRiodeJaneiro(UERJ),RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil

dDepartamentodeMatemáticaeEstatística,UniversidadeFederaldoEstadodoRiodeJaneiro(UNIRIO),RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil ePontifíciaUniversidadeCatólicadoRiodeJaneiro(PUC-Rio),RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil

fEscolaNacionaldeSaúdePública(ENSP),Fundac¸ãoOswaldoCruz(Fiocruz),RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory: Received20July2015 Accepted25February2016 Availableonline12April2016

Keywords:

Systemiclupuserythematosus Chronicdisease

Health-diseaseprocess Freeassociation Userembracement

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Introduction:Thisstudy,developedinafederalhospitalinthecityofRiodeJaneiro,hasaimed toanalyzethesocialrepresentationofchronicdiseaseanditstreatment,intheperspective ofadolescentsandtheircaregivers.

Methods:Thesampleconsistedof31 adolescents(11–21years)withsystemiclupus ery-thematosusand19caregivers(32–66years),followedinthepediatricsandintheinternal medicineoutpatientclinicsforaperiodofsixmonths.Datawascollectedfromthefree associationofwordstest,usingchronicdiseaseandtreatmentofchronicdiseaseimpulses,and latersubmittedtotheMultipleCorrespondenceAnalysisusingtheRsoftware.

Results:Thegroupofadolescentsassociatedtheimpulsechronicdiseasewiththewords medication,bad,illness,difficulty,nocure,faithandjoy;andinthegroupofcaregivers,tocare, treatment,nocureandtheword‘no’.Theimpulsetreatmentofchronicdiseasewasassociated, inthegroupofadolescents,withthewordspatience,improvement,help,affection,careand bad;andinthegroupofcaregivers,tocaring,hope,schedule,knowledge,obedience,medication, professionalandimprovement.Caregiversalsoassociatedimpulsesandwordsaccordingto age:chronicdiseasewasassociatedwiththewordcare(over61years),painandimpotence (42–61years),treatment(22–41years);andtreatmentofchronicdisease,withthewordsstrength (over61years),professional,knowledgeandimprovement(42–61years),affectionandschedule (22–41years).

Conclusions:Consideringassubjectiveanddynamictheexperienceofgettingill,knowingthe representationscancontributetotheorientationofconductandtypeofpsychotherapeutic interventionneeded.

©2016ElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

夽

ThisresearchwasdevelopedintheHospitalFederaldosServidoresdoEstado,RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil. ∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:olresende@terra.com.br(O.L.CeppasResende). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbre.2016.03.016

A

representac¸ão

do

adoecer

em

adolescentes

com

lúpus

eritematoso

sistêmico

Palavras-chave:

Lúpuseritematososistêmico Doenc¸acrônica

Processosaúde-doenc¸a Associac¸ãolivre Acolhimento

r

e

s

u

m

o

Introduc¸ão: Esseestudo,feitoem umhospitalfederalnacidadedoRio deJaneiro,teve por objetivoanalisara representac¸ãosocialdadoenc¸acrônicaedeseutratamento,na perspectivadeadolescentesedeseuscuidadores.

Métodos: A amostra consistiu de31 adolescentes(11–21 anos)com lúpuseritematoso sistêmico e 19 cuidadores (32–66 anos),seguidos em servic¸ospediátricos e de clínica médicaduranteseismeses.Foramcoletadosdadoscomaaplicac¸ãodoTestedeAssociac¸ão Livrede Palavras,comousodos impulsosdoenc¸a crônicae tratamentoda doenc¸acrônica, maistardesubmetidosàAnálisedeCorrespondênciaMúltiplacomousodoprogramade computadorR.

Resultados: Ogrupodeadolescentesassociouoimpulsodoenc¸acrônicacomaspalavras remédio,ruim,doenc¸a,dificuldade,semcura,fé,ealegria;eogrupodecuidadorescomaspalavras carinho,tratamento,semcura,ecomapalavra“não”.Oimpulsotratamentodadoenc¸acrônicafoi associado,nogrupodeadolescentes,comaspalavraspaciência,melhoria,ajuda,afeto,carinho eruim;e,nogrupodoscuidadores,comaspalavrascarinho,esperanc¸a,horário,conhecimento, obediência,remédio,profissionalemelhoria.Oscuidadorestambémassociaramosimpulsos epalavrasdeacordocomafaixaetária:doenc¸acrônicafoiassociadoàpalavracarinhoofsti (>61anos),doreimpotência(42–61anos),tratamento(22–41anos);etratamentodadoenc¸acrônica foiassociadoàspalavrasforc¸a(>61anos),profissional,conhecimentoemelhoria(42–61anos), afetoehorário(22–41anos).

Conclusões: Considerandoa experiênciadoadoecer comosubjetivae dinâmica,o con-hecimento dasrepresentac¸ões podecontribuirparaa orientac¸ão da condutae tipode intervenc¸ãopsicoterapêuticanecessária.

©2016ElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCC BY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Theconceptofhealthhasbeendiscussedovertheyearsand, withthecreationoftheUnifiedHealthSystem(SUS),healthis nowconsideredasarightofallcitizensandadutyoftheState (HealthOrganicLawn◦8080/1990,basedonArticle198ofthe FederalConstitutionof1988).Withtheincreaseinthedebates prioritizinghumanization,in2004theMinistryofHealth reg-ulated the National Humanization Policy (NHP),aiming to improverelationsbetweenprofessionals,users,hospitaland community.1

Humanizationappearsasatransversalpolicythatintents toovercometheboundariesofthedifferentknowledgeand powerintheproductionofhealth.2

With the proposal to humanize care and management

practice,the NHPpervades the SUSnetwork from aset of

actions and mechanisms3 – among which we must

high-lighttheattentionthatreferstoamodeofoperationofwork processes,rangingfromtheuser’sreceptioninthehealth sys-tem and full accountof their needs, to the solving ofthe problem.3,4

Regardingthepillarsoftheattention,onecanfindthe qual-ificationofrelationswithextendedlisteningandattentionto userneeds.Thatis,theattentionappearsasanintervention toolthatinvolvesconcernforthequalityandthekindof listen-ingthatisoffered.Beingabletohearandmakeoneselfheard isessentialsothatonecanbringup,onthehealthcarescene,

twosubjectsandamediatorobject(suffering,risks, dysfunc-tion),andnotasubject-professionalandhis/herobject-user.5

Especially inachronic illnesssituation –a conditionin whichthesubjecthastolivewithfortherestofhis/herlife6–

becomesessentialapracticebasedonthedialogical, interac-tiveandcaretakingdimension,wherethesubjectisperceived asanactiveandco-responsibleparticipantintheprocessof healthproduction.7,8

Knowing the meanings ofgetting ill, from the study of socialrepresentations,mayfavorthelisteningabilityofthe professionalsduringthecaringprocess,facilitatesocial com-municationandguideconducts.9

TheconceptofSocialRepresentation(SR)wasdefinedby MoscoviciinhisdoctoralthesisentitledLapsychanalyse,son imageetsonpublic(1961)andsubsequentlyfurtherdeveloped byJodelet(2001).Thus,SRwouldbe“asociallydevelopedand sharedformofknowledgethatcontributestotheconstruction ofacommonrealitytoaparticularsocialgroup”.10,11

Severalauthors statethatthereissuccessive correspon-dencebetweenthemeaningsthateachpersonattributesto the factsintheworldsharedincommon,12,13 andthat the

socialrealityinfluencesthewayeachpersonthinksandacts, includingonthediseasesituation.14–16Thatis,theexperience

ofthediseasedependsonwhatindividualsandsocialgroups understandbydisease,andhowtoplacethemselvesinface

ofit.14,17,18

andperceptionsofthesubjects,inascenarioofgettingilland ofcare.

The chosen disease was systemic lupus

erythemato-sus(SLE)–achronic, multisysteminflammatorydisease of unknowncauseandautoimmunenature,characterizedbythe presenceofautoantibodies,19,20 andthatcanleadto

physi-caland/orfunctionaldisability.21,22Accordingtosomestudies,

24–59%ofSLEpatientsmayhaveneurologicalimpairmentand neuropsychiatricandpsychofunctionalsyndromes.19–21

Theinclusionoftheenvironmentandofsocialfactorsin theunderstandingofSLEpatientswasshowntoberelevant,to theextentthatthereisaconsensusinthescientific commu-nityaboutthemultifactorialetiologyofSLE,suggestingthat thisdiseasehashormonal,genetic,infectious,environmental andpsychologicalcauses.20–23Formanyinvestigators,this

lat-tercausationisassociatedasamajorfactorfortheworsening ofthedisease.20,23–25

From the above, this study aimed to analyze the social representationsofchronicdiseaseanditstreatment,inthe perspectiveofadolescentsand/ortheircaregivers,hopingto bringacontributiontotheattentionofadolescentswithSLE.

Methods

ThisstudywasapprovedbytheResearchEthicsCommittee oftheHospitalFederaldosServidoresdoEstado(HFSE)under theopinionn◦456,572.

Data collectionwas conductedfrom February toAugust 2014,inthepediatricsandinternalmedicineoutpatientclinics andinthedaycarehospital.Allparticipantssignedaconsent form.

Inclusionandexclusioncriteria

Adolescentsaged11–21yearsdiagnosedwithawell-defined SLE,accordingtotheAmericanCollegeofRheumatology crite-ria and their caregivers were defined as participants. The classificationcriteria proposed in1982and revised in1997 arebasedonatleastfourofelevencriteria:malarrash, dis-coidlesion,photosensitivity,oralandnasalulcers,arthritis, serositis,renalimpairment,neurological,hematologicaland immunologicalchanges,andantinuclearantibodies.25–28

Asinclusioncriteria,onlypatientswithdiseasedurationof atleastsixmonthswereconsidered.

Takingintoaccountthatdifferentdiseaseshavedifferent impactsonthequalityoflifeofaffectedindividuals,aswellas intheperceptionofthediseaseandgettingill,theadolescents whohadotherdiseases,inadditiontolupus,wereexcluded, apartfromthefactthatthetypeandtheintensityofSLE mani-festationsimplylargerorsmallerdosesofcorticosteroids,and thatthismedicationcausespsychiatricdisordersintheshort term,inadditiontovariousadverseeffectsinthelongrun, thatmayinterfereinthesearchresults.

The caregivers were not carriers of lupus or any other chronicdisease,buttheirinclusioninthestudywas impor-tant,inordertobeawareofthemeaningsattributedtothe gettingill conceptfortheseindividuals,forthe purposeof comparingtheresultsbetweenthetwogroups(adolescents

and caregivers), considering that the family/cultural back-groundcaninterferewiththesignificanceprocess.12,13

Thesampleconsistedof31adolescentsand19caregivers (mother,father,grandparents),andtheageandlevelof edu-cationwerecategorized.Agegroups:11–21yearsrelativeto adolescents;over 61years,42–61years and22–41yearsfor caregivers.Thelevelofeducation(LE)was: higherlevelsof education(over12years);highschool(10–12years); elemen-taryschoollevelII(6–9years);andilliteracy/elementaryschool levelI(0–5years).

Thegroupofadolescentsaged11–21yearswascomposed of4boysand27girls;andthatofcaregiverswith32–66years old,2menand17women.Thelevelofeducation(LE)varied ineachgroup.TheLEofadolescentswas:higherlevelof edu-cation,12.90%,highschool,64.52%,andelementaryschoolII, 22.58%.TheLEofcaregiverswas:higherlevelofeducation, 15.79%,highschool,31.58%,elementaryschoolII,21.05%,and illiteracy/elementaryschoolI,31.58%.

Our adolescents presented the following SLE classifica-tion criteria:discoidlesion,photosensitivity, arthritis,renal

impairment, hematological changes, and immunological

changes.

Datacollectioninstrument

The toolusedfor datacollection was theFree Association WordsTest(FAWT),designedbyCarlJung(1905)inorderto obtainthepsychologicaldiagnosisonthepersonality struc-tureofindividuals.29In1981,thistestwasadaptedtothefield

ofSocialPsychology byDiGiacomo,becoming widelyused instudiesonSocialRepresentations.Inthesecases,inorder toidentifythelatentdimensionsofrepresentationswithout filteringcensorshipinevocation,bysettinganassociative net-workbetweenaninducingstimulusandevokedcontent.30,31

Thetest isperformedfrom the enunciation ofinducing stimuli, and analyzed subjects must quickly define words associatedwithstimulipresented.FAWTisbasedona con-ceptual repertoire that allowsunifying semantic universes andhighlightinguniversesofcommonwords,inthefaceof inducingstimuliandparticipantsinthestudy.29–33

Applicationmethod

Forabetterdefinitionoftheinducingstimulitobeused,apilot studystagewascarriedout,whereweevaluatedsome stimuli-candidates.Fromthisstage,ourdefinedstimuliwere:chronic disease(stimulus1)andtreatmentofchronicdisease(stimulus2). Withthesestimuli,weconsideredthatitwouldbepossibleto obtainthemeaningsgiventotheexperienceofchronicillness aswellastocare.

Thetestwasadministeredindividuallyinaprivateplace, toavoidinterferenceand ensureprivacy duringoutpatient consultationsinpediatricsandinternalmedicineoutpatient clinic and in the day-care hospital when the adolescents shouldbereceivingintravenousmedication.Theinvestigator, havinginhandpenandpaper,askedthesubjecttoassociate fivewordstoeachoneofthestimulicontainedinthe ques-tions,“WhatcomestoyourmindwhenIsaychronicdisease?”;and then,“WhatcomestoyourmindwhenIsaytreatmentofchronic disease?”.

Statisticalanalysis

Thefiveresponsestoeachstimulusandthe personal char-acteristicsofrespondentsgaverise toa multi-dimensional matrix,whoseexistingassociationscouldgivemeaningtothe feelingsrelatedtochronicillness.

Themostcommonmethodofanalysisusedinthe litera-tureofsocialrepresentationsistheMultipleCorrespondence Analysis (MCA), this being a multivariate technique that makesit possibletodescribetheassociationsfoundinthe dimensionsofafive-dimensionalspaceonatwo-dimensional graphical representation ofthe different existing interrela-tionsbetweenwordsorvariables.Inthiscase,ACMallowed ustoanalyzewhichexpressionsorwordsareassociated,both foradolescentsandcaregivers,aswellasassociationswiththe variables29that,inthisstudy,wereageandlevelofeducation.

Thistechnique,basedonoperations inthe datamatrix, definesproximityandoppositionrelationshipsbetweenthe wordsobtainedforeachstimulus,orwithotheractive vari-ables.Theimportanceofeachwordorvariable,ineachofthe dimensionsorfactors,isdeterminedfromitsweight,called “loadfactor”.TherepresentationintheCartesianaxisofwords andvariablesfromthesefactorloadingsandfromoppositions andvicinitiesallowsasearchforaninterpretationoftheaxes ofeachdimensionrelatedtotheproblem.Withthisanalysis, onecanalsoverifythelevelsofparticipationofthevariables intermsofabsolutecontribution.

StatisticalanalysiswasperformedusingtheFactomineR library,dedicatedtotheExploratoryMultivariateAnalysisof Data34oftheprogramR(freesoftware),atoolwidelyusedin

statistics.

Results

Thewordsevokedbythetestweregroupedtakingintoaccount semanticsimilaritiesandsynonyms(byconsultationofa dic-tionaryofthePortugueselanguage)35inthesingularformof

thenoun,andwiththeverbintheinfinitive.Thewordswould beretainedwhenappearingwithacertainfrequency,29and

inthisstudywordsmentionedthreeormoretimeswere con-sidered.Thiswasdoneforbothgroupsandforeachstimulus, resultinginafinalcompositionoffourwordlists.

Adatabasewasgeneratedforeachgroupandforeach stim-ulus,composedbyage,gender,levelofeducationandthefive evokedresponses.

In the face of the stimulus chronic disease, adolescents evoked147words,ofwhich 92wereretained(14different), whilecaregiversevoked87words,ofwhich57wereretained(9

Stimulus chronic disease

Adolescents

Adolescents

Caregivers

Caregivers Stimulus treatment of chronic disease

LEARNING DIFFICULTYLIMITATIONDISEASE

MEDICATION FAITH

PAIN

OVERCOMINGCARE

JOY

NO CURE SORROW

BAD

IMPOTENCE

NO

NO CURETREATMENT

HOPE

CARE

PAINSORROW

DOESN’T KNOW

STRENGTH KNOWLEDGE

IMPROVEMENT WARMTH

HOPE

STRENGTHCONSULTATION HOPE

DISCIPLINEMEDICATIONHAPPINESS

RESPONSIBILITY IMPROVEMENT

HEALTH

Fig.1–Cloudofwordsinthefacemuli1and2.

Source:http://www.wordle.net/create.

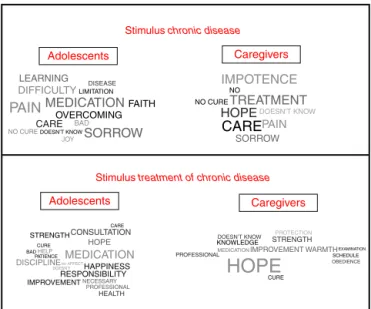

different).Inthefaceofthestimulustreatmentofchronicdisease, adolescentsevoked148words,ofwhich107wereretained(18 different),whilecaregiversevoked94words,ofwhich70were retained(13different).Torepresentthewordfrequency,we usedacloudofwordsproducedbyanapplicationsoftware availableatthesitehttp://www.wordle.net/create.36

Inthecloudofwords,thefontsizeisassociatedwithword frequency. Thelargerthe sizeofthe word,the moreoften thewordwasevokedinassociationwiththestimulus.Inthe clouds,onlythewordsretained(frequencyequalto,orgreater than,threeoccurrences)appear,andthedifferentshadesor colors are emptyofmeaning, servingonlyto facilitatethe visualizationofwordsretained(Fig.1).

Fromthecloudsofwordsproducedbythegroupof adoles-cents,therewasanassociationbetweenthestimuluschronic diseaseandthewords(indescendingorder):sadnessandpain (toagreaterdegree),medication,difficulty,learning,nocure,care, disease, limitation, faith, joy, bad; and some adolescents did notknowhowtonominate.Inthefaceofthestimulus treat-mentofchronicdisease,associationsemergedwiththewords (in descending order): medication and strength (toa greater degree),hope,improvement,consultation,discipline,joy, responsi-bility,health,needed,professional,help,care,cure,theword“no”, patience,bad,andaffection.

Thecloudsofwordsproducedbythegroupofcaregivers illustratedanassociationbetweenthestimuluschronicdisease andthewords(indescendingorder):impotence,treatment,care, pain,hope,sadness,nocure,theword“no”;andsomedidnot knowhowtonominate.Thestimulustreatmentofchronic dis-easeappearedassociatedwiththewords(indescendingorder): hope(highfrequency),care, improvement,strength, medication, knowledge, schedule, professional, cure, examination, obedience, protection(sun);andsomedidnotknowhowtonominate.

2

>12 years

Medication

Limitation

Sorrow Care

Learning

Joy Faith

10-12 years 6-9 years

Bad Disease Doesn’t know

Pain

1

0

Dim 2 (9.47%)

Dim 1 (11.61%) –1

–2

–4 0 2 4 6

Difficulty No cure

Fig.2–MultipleCorrespondenceAnalysis(MCA)–Adolescentgroup:Stimulus“chronicdisease”.

Source:softwareR.

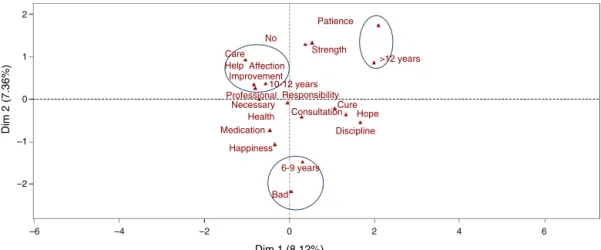

Inthevisualrepresentationofthisresult,itwaspossibleto perceivethattheadolescentswithhigherlevelsofeducation (above12yearsofstudy) associatedchronicdiseasewiththe wordmedication;thosewithhighschoollevel(10–12yearsof schooling)withthewordsdifficulty,nocure,faith,andjoy;and thosewithelementarylevelII(6–9yearsofstudy)withthe wordsbadanddisease(Fig.2).

IntheanalysisofMCAresultsfromthefirststimulusinthe groupofcaregivers,factors1and3,whichtogetherexplained 27.48%ofthevariancestructureofthedata,wereselected.

Inthevisualrepresentationofthisresult,anassociation betweencertainwords,ageandlevelofeducationwasnoted. Oldercaregiversassociatedchronicdiseasewiththewordcare, whiletheyoungeroneswiththewordtreatment.Astothe asso-ciationsaccordingtothelevelofeducation,itwasobserved thatcaregiverswithhighschoollevel(10–12yearsof school-ing)associatedchronicdiseasewiththewordstreatmentandno cure;thosewithelementaryschoolII(6–9yearsofstudy),tothe word“no”;andthosewithilliteracy/elementaryschoollevelI (0–5yearsofstudy)caregivers,withthewordcare(Fig.3).

In the analysis of MCA results obtained from the sec-ondstimulus,thefactors1and2wereselectedtoreportin bothgroups;thesefactorsexplained15.48%ofthevariability

1.0 No cure

Treatment

10-12 years

22-41 anos

42-61 years

>61 years

Pain

6-9 years

Impotence

No

Sorrow

Care 0-5 years

Doesn’t know >12 years

0.5

0.0

–0.5

–1.0

–1.5

–2.0

–1

–2 0 1

Dim 1 (14.47%)

Dim 3 (13.01%)

2 3 4

Hope

Fig.3–MultipleCorrespondenceAnalysis(MCA)– Caregivergroup:Stimulus“chronicdisease”.

Source:softwareR.

structureofthedataobtainedinthegroupofadolescents,and 20.04%inthegroupofcaregivers.

InthevisualrepresentationoftheresultofMCAobtained fromthesecondstimulusinthegroupofadolescents,a cor-relation was noted between wordsand level ofeducation.

2

1 Care

Help Affection Improvement

Professional Necessary Health Medication

Happiness

6-9 years No

Bad

Cure Consultation Responsibility 10-12 years

Strength Patience

>12 years

Hope

Discipline

0

–1

–2

–2 –4

–6

Dim 1 (8.12%)

Dim 2 (7.36%)

0 2 4 6

Fig.4–MultipleCorrespondenceAnalysis(MCA)–Adolescentgroup:Stimulus“treatmentofchronicdisease”.

>12 years

Warmth

22-41 years

>61 years 42-61 anos

Schedule

10-12 years Hope

6-9 years Profissional Knowledge Obedience Improvement

Doesn’t know 0-5 years

Examination

Strength Protection

Cure

Medication 2

1

0

–1

–1

–2 0

Dim 1 (10.30%)

Dim 2 (9.74%)

1 2

Fig.5–MultipleCorrespondenceAnalysis(MCA)– Caregivergroup:Stimulus“treatmentofchronicdisease”.

Source:softwareR.

Adolescentswithhigherlevelsofeducation(above12years ofstudy)associatedtreatmentofchronicdiseasewiththeword patience; those with high school education (10–12 years of schooling)withthewordsimprovement,help,affectionandcare; andthosewithelementaryschoollevelII(6–9yearsofstudy) withthewordbad(Fig.4).

InthevisualrepresentationoftheresultofMCAobtained

from the second stimulus in the group of caregivers, we

noticedanassociationbetweenwords,ageandlevelof educa-tion.Oldercaregivers(above61years)associatedtreatmentof chronicdiseasewiththewordstrength;thoseaged42–61years, withthe wordsprofessional, knowledgeand improvement;and thoseyoungerones(22–41years),withthewordschedule. Care-giverswithhigherlevelsofeducation(above12yearsofstudy) associatedtreatmentwiththewordcare;thosewithhighschool level(10–12yearsofschooling)withthewordhope;thosewith elementaryschoollevelII(6–9yearsofstudy)withthewords knowledgeandobedience;andthosewithilliteracy/elementary schoollevelI(0–5yearsofstudy)withthewordsmedicationand “Don’tknow”(Fig.5).

Discussion

and

conclusion

Thebirthofachildisalwaysfullofdesires,dreams, expecta-tionsandmeanings–basichallmarksofitssubjectivity,based ontheinitialmother–babybond.37 Althoughtheactualson

nevermatchestheimaginarychildbecausethisisalways ide-alized,thebirthofachildwithadisabilityorillnesscanaffect themother–childrelationship,confirmingthemother’s fan-tasiesinherabilitytobegetornotbegeta“perfectchild”.37–39

Having a child with a chronic health condition causes

changes in family routine and can reflect on family

dynamics13andalsocausesanimpactoneverydaylife.15 A

studyofmaternalrepresentationsaboutthebirthofachild withsevereorganicdiseaseshowsthatthespeechof moth-ersabouttheirchildrenbeginswiththehealthproblemofthe child,asiftheydidnotfindanotherpossibilityof symboliza-tionabouttheirchildthanthedisease.37Forallthesereasons,

webelievethattheinclusionofcaregivers–thoseresponsible forthetreatmentoftheadolescent–inthisstudyisimportant,

andtheknowledgeoftheirperceptionofthediseaseandofthe careoffered,andifthereissimilaritybetweenthemeanings assignedbythetwogroups.

Chronic disease, especially when it occurs in children or adolescents, affects all parties involved(patient, family, professionals)throughmultiplefactors:difficultiesand lim-itations arising from the disease itself, treatment for life, sufferinginthe faceofthesocialstigma,13 the narcissistic

woundstemmingfrom nothavingaperfectchild,40,41

eco-nomicissues(fromthecostoftreatmenttotheeducationand integrationinthelabormarket),42amongothers.

Thepsycho-emotionalaspectisalwayspresentatdifferent levelsandtimes,notjustin“psychosomatic”diseaseswhere theemotionalaspectcomesasatriggeringfactor,butinthe veryconditionofbeingill.AlthoughSLEdisplayanevolution typicallymarked byperiodsofremissionand exacerbation, sufferingtheimpactofseveralfactors,someauthorsidentify theonsetofthediseaseaftersituationsof“stress”and worsen-ingofclinicalactivity,precededbyeverydaystressorsrelated tointerpersonalrelationships.43,44Othersnotetheinfluence

ofemotions and ofthe environment inthe immunity and

physicalconditionofthepatients.45

Sincethe experienceofgettingill dependsonwhat the

person means by disease,18 and given that the meanings

attributed tothe facts are influenced bythe socio-cultural environment,14,16,18wehavetriedtoanalyzethesocial

rep-resentationsofadolescentswithlupusandoftheircaregivers inrelationtochronicillnessandtotreatment,bymeansofan associativenetworkofwords.

Fromthelistsofwordsproduced,weobserved antagonis-ticfeelingsandperceptions,althoughsomeevocationswere similarbetweenthetwogroups.

Theassociations madebytheadolescents inthisstudy, whenfacedwiththetwostimuli,illustratedevocationsofpain and,atthesametime,oftheneedtofight:sadness,difficulty, overcoming,faith,joy,strength,hope,patience–pointingto theimportanceofsupport(family,friends,professionals)in fightingthedisease.Intheirevocations,theadolescents rec-ognizedtheimportanceoftreatmentfortheimprovementof thedisease(medication,consultation,discipline,responsibility, nec-essary,patience),emphasizingthefigureoftheprofessionaland ofcare.

Theassociationsperceivedinthecloudsofwordsevoked bycaregiversshowedthesameantagonism:ontheonehand, wordssuchaspain,impotence,sadness,nocure;andontheother, wordslikehope,care,strength.Thewordsmedication,schedule, knowledge,obedience,andthefigureoftheprofessionalwere alsoevoked,pointingtotheimportanceoftreatment

adher-enceandcommitment.

Words common to both groups emerged, corroborating

the findings of some authors about the influence of the

environment in the process of signification in a disease situation14,16,18: the stimuluschronicdiseaseassociatedwith

thewordscare/treatment,pain,sorrow,limitation/impotence;and the stimulustreatment ofchronicdiseaseassociatedwiththe wordsstrength,medication,improvement.

with the words care (over 61 years), pain and impotence (42–61years),andtreatment(22–41years).Theentailmentof chronicdiseasetocare/treatmentpointstotheperceptionofa situationthatrequiresacontinuousmonitoring.6

Thestimulus chronicdisease treatment was associatedby caregiverswiththewords:strength(over61years);professional, knowledge and improvement (42–61 years); and affection and schedule(22–41years).Thatistosay,thecaregiversnotonly entailedthedisease tocare,but broughtinto this scenario thefigureoftheprofessionalandaffections–affectionand strength.

Itwasobservedthatinthefaceofthetwostimuli, differ-entassociationsemergedfromthelevelofeducationinboth groups,adolescentsassociatedchronicdiseasewiththewords: medication(over12years);difficulty,nocure,faith,andjoy(10–12 years);badanddisease(6–9years),whilecaregiversassociated chronicdiseasewiththewords:treatment,nocure,andtheword “no”(10–12yearsofschooling);andcare(0–5yearsof school-ing).

AlthoughsomestudiesshowthatpatientswithSLEhave asignificantrateindicativeofpsychiatricdisorder (anxiety, irritability, depression),25 the results of our study showed

ambivalentfeelingsandperceptionsofadolescentswithSLE, relativetothestimuluschronicdisease:evocationsexpressing negativeandpositivefeelings, enhancementoftherapeutic possibilities,andexaltationoffaithinthisconfrontation.If, ontheonehand,thesefindingsbroughtapoorprognosisfor thedisease(difficulty-bad-nocure),thefactthatthediseaseis treatable(joy-medication)prevailed.

Caregivers,despiteunderscoringtheimportanceof treat-ment andcare, associatedchronicdiseasetopain, impotence, andnocure, perhapsthankstotheburdenofresponsibility ontheseindividuals,fortheirresponsibilityforthetreatment ofthechild,inadditiontotheconcernaboutthefutureofthe teenagerwhooftenhavehis/herschoollifedisrupteddueto constantcomingsandgoingstothehospital.42

In general, treatment was seen positively (improvement, hope,help),withactiveparticipationofthepatient(knowledge, obedience,schedule,medication).And participantswithhigher levelsofeducationbrought,incommon,thevaluationofthe diseasebeingtreatable,theperceptionoftreatmentoutcome, andfeelingsofhopeandaffectioninthisconfrontation.That is,thelevelofeducationseemstointerferewiththeprocess ofsignification,inpromotingtheexpansionoftheworldview, theperceptionofthelimitsandpossibilities–aresultthat corroboratesthefindingsofotherauthorsaboutthe experi-ences,whichareindividual;butthemeaningsareinfluenced byfamilyandsocioculturalenvironment.14,16–18,46

Theinclusionofthefigureoftheprofessionalsinthe ther-apeutic scene calls for a reflection on the messages they transmitintheconsultations:Howcantheyinterfereby offer-ing,ornotofferingsupport,strength,careandtransmission ofinformation?

Inlinewithsomeauthors,ourstudyshowsthatthe anal-ysisofrepresentationscancontributeto extendthe ability of listening and the interpretation of the statements and demandsofpatients,47byprovidingaccesstothelatent

mean-ingsofchronicillness.Thismethodologynotonlyfavorsthe occurrenceofaqualifiedlistening tothe needsofpatients and caregivers, but brings subsidies to actions that offer

psychological support,in order tohelp the patient’s adap-tation to SLE, reducing his/herpain and worsening of the

disease, improving depression and anxiety, and also the

patient’sself-esteemandqualityoflife.48,49

Somelimitationsofthestudy occurredbylackof socio-demographic characteristics, considering that the patient’s housing location produce interesting social and economic data, and the lackofdataon the administrationand dose ofmedicationsused,whichcouldperhapsinterferewiththe representation of illness by the adolescents, as these are

patients with heterogeneous treatments and with adverse

events,especiallyinchildrenandadolescents.

However,themeaningsthatthepersonusestoexplainthe diseaseprovidepartialandunfinishedpictures,becausethe realityisdynamicandtheexperiencerathercomplex.15

Fur-ther studiesarerequiredtoelucidatevarious issues,tothe extentthatthereisarangeoffactorsthatmayinterferewith theprocessofsignification.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1.Brasil.HumanizaSUS:PolíticaNacionaldeHumanizac¸ão:a humanizac¸ãocomoeixonorteadordaspráticasdeatenc¸ãoe gestãoemtodasasinstânciasdoSUS.Brasília:Secretaria Executiva,MinistériodaSaúde;2004.

2.SouzaWS,MoreiraMCN.Atemáticadahumanizac¸ãona saúde:algunsapontamentosparadebate.Interface– Comunicac¸ão,Saúde,Educac¸ão.2008;12:327–38. 3.BrehmerLCF,VerdiM.Acolhimentonaatenc¸ãobásica:

reflexõeséticassobreaatenc¸ãoàsaúdedosusuários.Ciência SaúdeColetiva.2010;15:3569–78.

4.AyresJRCM.Cuidadoehumanizac¸ãodaspráticasdesaúde. In:DeslandesSF,editor.Humanizac¸ãodoscuidadosem saúde:conceitos,dilemasepráticas.RiodeJaneiro:Fiocruz; 2006.p.49–83.

5.FrancoTB,BuenoW,MerhyEE.Oacolhimentoeosprocessos detrabalhoemsaúde:ocasodeBetim,MinasGerais,Brasil. CadSaudePubl.1999;15:345–53.

6.CanesquiAM.Olharessocioantropológicossobreos adoecidoscrônicos.SãoPaulo:Hucitec/Fapesp;2007. 7.KleinmamA.Theillnessnarratives:suffering,healingand

thehumancondition.NewYork:BasicBooksInc.;1988. 8.BuryM.Illnessnarrative:factorfiction?SociolHealthIlln.

2001;23:263–85.

9.MinayoMCS,AssisSG,SouzaER,NjaineK,DeslandesSF,Silva CMFP,etal.Falagalera:juventude,violênciaecidadaniana cidadedoRiodeJaneiro.RiodeJaneiro:Garamond;1999. 10.MoscovicS.Arepresentac¸ãosocialdapsicanálise.Riode

Janeiro:Zahar;1978.

11.JodeletD.Representac¸õessociais:umdomínioemexpansão. In:JodeletD,editor.Asrepresentac¸õessociais.RiodeJaneiro: Eduerj;2001.p.17–44.

12.BergerP,LuckmannT.Aconstruc¸ãosocialdarealidade: tratadodesociologiadoconhecimento.Petrópolis:Vozes; 2006.

14.AtkinsonS.Anthropologyinresearchonthequalityofhealth services.CadSaúdePúbl.1993;9:283–99.

15.LiraGV,NationsMK,CatribAMF.Cronicidadeecuidadosem saúde:oqueaantropologiadasaúdetemnosensinar?Texto ContextoEnferm.2004;13:147–55.

16.EstevamID,CoutinhoMPL,AraújoLF.Osdesafiosdaprática socioeducativadeprivac¸ãodeliberdadeemadolescentesem conflitocomalei:ressocializac¸ãoouexclusãosocial?Rev PsicoPortoAlegre.2009;40:64–72.

17.OliveiraFA.Antropologianosservic¸osdesaúde: integralidade,culturaecomunicac¸ão.Interface–Comun, Saúde,Educ.2002;6:63–74.

18.GomesR,Mendonc¸aEA.Arepresentac¸ãoeaexperiênciada doenc¸a:princípiosparaapesquisaqualitativaemsaúde.In: MinayoMCS,DeslandesSF,editors.Caminhosdo

pensamento:epistemologiaemétodo.RiodeJaneiro:Fiocruz; 2008.p.109–32.

19.SatoEL,BonfáED,CostallatLTL,SilvaNA,BrenolJCT, SantiagoMB,etal.Consensobrasileiroparaotratamentodo lúpuseritematososistêmico.RevBrasReumatol.2002;42: 362–70.

20.AyacheDCG,CostaIP.Alterac¸õesdapersonalidadenolúpus eritematososistêmico.RevBrasReumatol.2005;45:313–8. 21.AppenzellerS,CostallatLTL.Comprometimentoprimáriodo

sistemanervosocentralnolúpuseritematososistêmico.Rev BrasReumatol.2003;43:20–5.

22.BorbaEF,LatorreLC,BrenolJCT,KayserC,SilvaNA, ZimmermannAF,etal.Consensodelúpuseritematoso sistêmico.RevBrasReumatol.2008;48:196–207.

23.FreireEAM,SoutoLM,CiconelliRM.Medidasdeavaliac¸ãoem lúpuseritematososistêmico.RevBrasReumatol.

2011;51:70–80.

24.MiguelFilhoEC[TesedeDoutorado]Alterac¸ões

psicopatológicasnoLúpusEritematosoSistêmico.SãoPaulo: UniversidadedeSãoPaulo;1992.

25.MeloLF,Da-SilvaSL.Análiseneuropsicológicadedistúrbios cognitivosempacientescomfibromialgia,artritereumatoide elúpuseritematososistêmico.RevBrasReumatol.

2012;52:175–88.

26.TanEM,CohenAS,FriesJF,MasiAT,McShaneDJ,RothfieldNF, etal.The1982revisedcriteriafortheclassificationof systemiclupuserythemathosus.ArthritisRheum. 1982;25:1271–7.

27.HochbergMC.UpdatingtheAmericanCollegeof Rheumatologyrevisedcriteriafortheclassificationof systemiclupuserythemathosus.ArthritisRheum. 1997;40:1725.

28.CostallatLTL,AppenzellerS,BértoloMB.Lúpus

neuropsiquiátricodeacordocomanovanomenclaturae definic¸ãodecasosdocolégioAmericanodeReumatologia (ACR):análisede527pacientes.RevBrasReumatol. 2001;41:133–41.

29.GuerreiroMR,CuradoMA.Picar...fazdoer!Representac¸ões

dedornacrianc¸a,emidadeescolar,submetidaapunc¸ão venosa.RevEnfermeiraGlobalEnero.2012;25:75–91. 30.NóbregaSM,CoutinhoMPL.Otestedeassociac¸ãolivrede

palavras.In:CoutinhoMPL,editor.Representac¸õessociais: abordageminterdisciplinar.JoãoPessoa:UniversitáriaUFPB; 2003.p.67–77.

31.DeRosaAS.Aredeassociativa:umatécnicaparacaptara estrutura,osconteúdoseosíndicesdepolaridade, neutralidadeeestereotipiadoscampossemânticos relacionadoscomasrepresentac¸õessociais.In:MoreiraASP, JesuinoBVCJC,NóbregaSM,editors.Perspectivas

teórico-metodológicasemrepresentac¸õessociais.João Pessoa:UniversitáriaUFPB;2005.p.61–128.

32.CoutinhoMPL.Depressãoinfantil:umaabordagem psicossocial.JoãoPessoa:UniversitáriaUFPB;2005. 33.BotêlhoSM,BoeryRNSO,VilelaABA,SantosWS,PintoLS,

RibeiroVM,etal.Ocuidarmaternodiantedofilhoprematuro: umestudodasrepresentac¸õessociais.RevEscEnfermUSP. 2012;46:929–34.

34.LêS,JosseJ,HussonF.FactoMineR:anRpackagefor multivariateanalysis.JStatSoftw.2008;25:1–18.

35.DicionárioEditoradaLínguaPortuguesa.Colec¸ãoDicionários Editora,PortoEditora,Edic¸ão2014,ISBN978-972-0-01866-3. 36.NuvensdePalavras.Availablein:

http://www.wordle.net/create.

37.BattikhaEC,FariaMCC,KopelmanBI.Asrepresentac¸ões maternasacercadobebêquenascecomdoenc¸asorgânicas graves.Psicol:TeoriaePesquisa.2007;23:17–24.

38.Cullere-CrespinG.Aclínicaprecoce:onascimentodo humano.SãoPaulo:CasadoPsicólogo;2004.

39.BeliniAEG,FernandesFDM.Olharecontatoocular:

desenvolvimentotípicoecomparac¸ãonaSíndromedeDown. RevSocBrasFonoaudiol.2008;13:52–9.

40.FreudS.Sobreonarcisismo:umaintroduc¸ão.Edic¸ãoStandard BrasileiradasObrasPsicológicasCompletasdeSigmund Freud,xiv.RiodeJaneiro:Imago;1976.p.103–8.

41.MartinsBSO.Ocorpo-sujeitonasrepresentac¸õesculturaisda cegueira.RevPsicol.2009;21:5–22.

42.ResendeOLC[Dissertac¸ãodeMestrado]Omédicoeadíade comdoenc¸aoculargrave.RiodeJaneiro:Fundac¸ãoOswaldo Cruz;2010.

43.PetriM.Systemiclupuserythematosus:clinicalaspects.In: KoopmanWJ,editor.Arthritisandalliedconditions:a textbookofRheumatology,26,14thed.LippincottWilliams; 2000.p.377–88.

44.NeryFG,BorbaEF,NetoFL.Influênciadoestressepsicossocial nolúpuseritematososistêmico.RevBrasReumatol.

2004;44:355–61.

45.SolomonGF,MoosRH.Emotions,immunity,anddisease;a speculativetheoreticalintegration.ArchGenPsychiatry. 1964;11:657–74.

46.GeertzC.Ainterpretac¸ãodasculturas.RiodeJaneiro:Livros TécnicoseCientíficosEditora;1989.

47.FavoretoCAO,CabralCC.Narrativassobreoprocesso saúde-doenc¸a:experiênciasemgruposoperativosde educac¸ãoemsaúde.Interface–Comunicac¸ão,Saúde, Educac¸ão.2009;13:7–18.

48.CalSF,BorgesAP,SantiagoMB.Prevalênciaeclassificac¸ãoda depressãoempacientescomlúpuseritematososistêmico atendidosemumservic¸odereferênciadacidadedeSalvador. JLIRNNE.2006;2:36–42.

49.CalSFLM.RevisãodaLiteraturasobreaeficáciada