REVISTA

BRASILEIRA

DE

ANESTESIOLOGIA

PublicaçãoOficialdaSociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologiawww.sba.com.br

SCIENTIFIC

ARTICLE

The

effect

of

two

different

glycemic

management

protocols

on

postoperative

cognitive

dysfunction

in

coronary

artery

bypass

surgery

Pinar

Kurnaz

a,∗,

Zerrin

Sungur

a,

Emre

Camci

a,

Nukhet

Sivrikoz

a,

Gunseli

Orhun

a,

Mert

Senturk

a,

Omer

Sayin

a,

Emin

Tireli

b,

Hakan

Gurvit

caIstanbulUniversityIstanbulMedicalFaculty,DepartmentofAnesthesiology,Istanbul,Turkey bIstanbulUniversityIstanbulMedicalFaculty,DepartmentofCardiacSurgery,Istanbul,Turkey cIstanbulUniversityIstanbulMedicalFaculty,DepartmentofNeurology,Istanbul,Turkey

Received30October2015;accepted7January2016 Availableonline18April2016

KEYWORDS

Glucosecontrol; Cognitive dysfunction; Coronaryartery bypasssurgery

Abstract

Introduction:Postoperativecognitivedysfunction(POCD)isanadverseoutcomeofsurgerythat ismorecommonafteropenheartprocedures.Theaimofthisstudyistoinvestigatetheroleof tightlycontrolledbloodglucoselevelsduringcoronaryarterysurgeryonearlyandlatecognitive decline.

Methods:40patientsolderthan50yearsundergoingelectivecoronarysurgerywererandomized into two groups.In the ‘‘TightControl’’ group (GI),the glycemiawas maintained between 80and120mgdL−1whileinthe‘‘Liberal’’group(GII),itrangedbetween80---180mgdL−1.A neuropsychologicaltestbatterywasperformedthreetimes:baselinebeforesurgeryand follow-upfirstand12thweeks,postoperatively.POCDwasdefinedasadropofonestandarddeviation frombaselineontwoormoretests.

Results:Atthepostoperativefirstweek,neurocognitivetestsshowedthat10patientsinthe GIand11patientsinGIIhadPOCD.TheincidenceofearlyPOCDwassimilarbetweengroups. Howeverthelateassessmentrevealedthatcognitivedysfunctionpersistedinfivepatientsin theGIIwhereasnonewasratedascognitivelyimpairedinGI(p=0.047).

Conclusion:Wesuggestthattightperioperativeglycemiccontrolincoronarysurgerymayplay aroleinpreventingpersistentcognitiveimpairment.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisan openaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:pkurnaz@hotmail.com(P.Kurnaz).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2016.01.001

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Controleglicêmico; Disfunc¸ãocognitiva; Cirurgiade

revascularizac¸ãodo miocárdio

Efeitodedoisprotocolosdecontroleglicêmicodiferentessobreadisfunc¸ãocognitiva apóscirurgiaderevascularizac¸ãodomiocárdio

Resumo

Introduc¸ão: Adisfunc¸ãocognitivapós-operatória(DCPO)éumresultadoadversocirúrgicoque émaiscomumapóscirurgiascardíacasabertas.Oobjetivodesteestudofoiinvestigaropapel dosníveisdeglicosenosanguerigorosamentecontroladosduranteacirurgia coronarianano declíniocognitivoprecoceetardio.

Métodos: Quarentapacientescomidadesacimade50anosesubmetidosàcirurgiacoronariana eletivaforamrandomizadosemdoisgrupos.Nogrupo‘‘controlerigoroso’’(GI),aglicemiafoi mantidaentre80-120mg.dL−1;enquantonogrupo‘‘liberal’’(GII),variouentre80-180mg.dL−1. Abateriadetestesneuropsicológicosfoirealizadatrêsvezes:fasebasal,antesdacirurgiaena primeiraedécimasegundasemanadeacompanhamentonopós-operatório.DCPOfoidefinida comoumaquedadeumdesviopadrãodafasebasalemdoisoumaistestes.

Resultados: Naprimeirasemanadepós-operatório,ostestesneurocognitivosmostraramque 10pacientesnoGIe11pacientesnoGIIapresentaram DCPO.AincidênciadeDCPOprecoce foisemelhanteentreosgrupos.Noentanto,aavaliac¸ãotardiarevelouqueadisfunc¸ão cog-nitiva persistiuem cincopacientesnoGII, enquantonenhum pacientefoi classificadocomo cognitivamenteprejudicadonoGI(p=0,047).

Conclusão:Sugerimosqueocontroleglicêmicorigorosonoperioperatóriodecirurgia coronar-ianapodedesempenharumpapelnaprevenc¸ãodadeteriorac¸ãocognitivapersistente. ©2016SociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologia.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eum artigo OpenAccess sobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction(POCD) is an intellec-tualdecline relatedtosurgery. Olderpatients undergoing majorsurgeryareat increasedrisk ofPOCD thatcovers a broadclinicalspectrumrangingfrommildconcentration dif-ficultiestoseriousbehavioral problemsthat canbeeasily confoundedwithdelirium.1,2Theproblemcanbetransient but also persist for a longer period. In the early phase, POCDcausesprolongedhospitalizationandcandisrupt qual-ityoflifebycomplicating therehabilitationperiod.POCD alsoaffectsthemortalityratein thelongterm.3,4Finally, althoughthemechanismsarenotclear,POCDisadebatable risk factor for delayed andchronic changesassociated to dementiaandAlzheimer’sdisease.5

Cognitivedeclineaftercardiacsurgeryismorefrequent comparedtonon-cardiacmajorsurgery.Theincidencerate variesbetween25%and80%accordingtovariousstudies.6,7 Recentadvancesin theperioperativemanagement includ-ing surgical techniques, anesthetic choice, and perfusion strategies have decreased the incidence rate of major complications.However,thefrequencyofcognitivedecline afteropenheartsurgeryhasnotimproved.Theetiologyof POCDrelatedtocardiacsurgeryismultifactorial,and vari-ouspreoperativeandintraoperativefactorsareassociated withthedisorder.Cerebralhypoperfusiondueto microem-bolization or systemic hypotension, serious inflammatory responsetoextracorporealcirculationandtosurgical stim-uli, temperature perturbations, and metabolic instability arethemostcommonetiologicfactors.8,9

Hyperglycemiainducedbyopenheartprocedurescauses a seriesof adverse events, includingserious arrhythmias,

low output state, and infections, and results in a pro-longedstayintheintensivecareunitwithdelayinhospital discharge.10,11 The hyperglycemic state triggered by car-diacsurgerymayalsobeharmfultothehypoperfusedbrain andworsentheneurologicstatusanalogous tothatstroke patients.12Cognitivedeteriorationincardiacsurgerycanbe associatedand/or aggravated by this‘‘diabetic state’’ of thosepatientsandberestrainedtosomeextentby control-lingglucoselevelsduringtheoperativeperiod.

The aimof thepresent study istoinvestigate therole of tightly controlled blood glucose levels during coronary arterysurgeryinordertopreventearlyandlate postopera-tivecognitivedysfunction.

Methods

The study wasdesigned and conducted as a prospective, double-blind,randomizedclinicaltrial. Thephysician per-formingtheneuropsychologicaltestsandthepatientswere blindedtotheperioperativeglycemicmanagement.

In addition to these medical conditions, patients with communicationproblems due toserious sightandhearing defects, inadequate use of native language, and lack of readingand writingskills were excluded.Finally, patients who scored less than 23 on the Mini-Mental State Exam-ination (MMSE)at the initial evaluation were excluded in ordertoeliminatethepopulationwhoalreadyhadcognitive impairment.

Anesthesia induction was achieved with 10---15gkg−1

fentanyl, 0.1---0.2mgkg−1 midazolam, and 0.1mgkg−1

vecuroniumbromide.Sevofluranebasedinhalational anes-thesiaandfentanylinfusionwithsupplementalvecuronium bromide doses were used for maintenance including the cardiopulmonary bypass period. Pressure-controlled mechanicalventilationwithFiO2:0.5,inspiratorypressure

leveltoobtainatidalvolumeof8mLkg−1,respiratory

fre-quencytoobtain an ETCO2of 40---45mmHg,and 5cmH2O

PEEP were adjusted. During the cardiopulmonary bypass, thelungswerepassivelydeflated.

Allpatientswereoperatedonbythesamesurgicalteam at 32◦C and a mild level of hemodilution (Hct: 26---28%). Pumpflowrateswereadjustedto2.5Lmin−1perm2forthe

normothermic phase and 2.25---2.5Lmin−1 per m2 for the

hypothermicphaseduringwhich thetargetsystemic arte-rial pressure was 70mmHg. Intermittent antegrade blood cardioplegiawasappliedina20mLkg−1inductiondoseand

10mLkg−1inevery30minasmaintenance.Attheendofthe

intervention,patientsweretransferredtotheintensivecare unitunderpropofolandmidazolamsedationandcontrolled ventilation.The weaningprocessfromsedation, mechani-calventilation,andinotropicsupportwasmanagedbythe intensivecareteamaccordingtotheirroutineclinical pro-cedure.Regardingtostudyprotocolallabnormal(loweror higherthanthelimits)laboratoryresultsofanyparameter duringroutinemeasurementsofanyparameter whichcan possiblyaffecttheglucoselevel,suchasbloodNalevelhas beenobserved.Finallytheneedforpostoperativeinotropic supportandmechanicalventilationtimewererecordedfor everypatient.

Glucosecontrol

Afteranesthesiainduction,patientswererandomizedinto twogroups according tothesealedenvelopesystem. Dia-betic patients were included to the same randomization processregardlessofthetypeofthedisease.TheGIK solu-tion, which is our routine application for intraoperative managementof diabetic patients duringcardiac and non-cardiac surgery, is used for all diabetic patients in both groups beforetheinitiation of additiveinsulin infusion to achievetargetedglucoselevels.

Inthetightglucosecontrolgroup(GI),thebloodglucose levelwasmaintainedbetween80and120mgdL−1whilein

thesecondgroup,namedtheliberalglucosecontrol(GII), thebloodglucoselevelrangedbetween80and180mgdL−1.

Thisisasimilarwayofgroupingtopreviousstudyto exam-ining‘‘tightglucosecontrol’’strategy.13

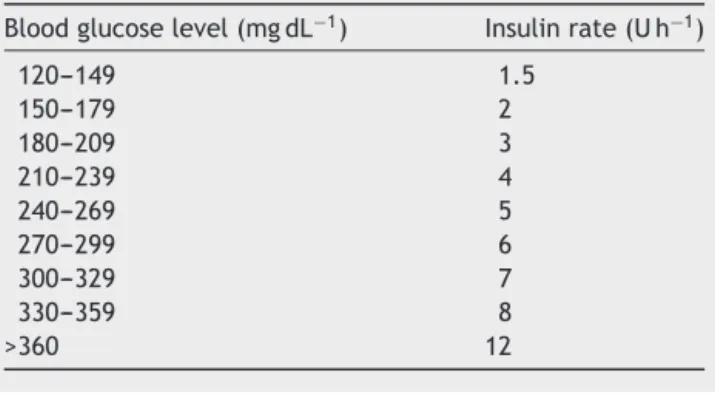

In order to achieve this target, Group I patients received an insulin infusion when their blood glucose level exceeded 120mgdL−1. The rate was adjusted in

response to their actual blood glucose level (Table 1). A

Table1 Insulininfusionratesforthetightglucosecontrol

group(GI).

Bloodglucoselevel(mgdL−1) Insulinrate(Uh−1)

120---149 1.5

150---179 2

180---209 3

210---239 4

240---269 5

270---299 6

300---329 7

330---359 8

>360 12

Table2 Insulininfusionratesfortheliberalglucosecontrol

group(GII).

Bloodglucoselevel(mgdL−1) Insulinrate(Uh−1)

180---239 2

240---299 3

300---359 5

>360 6

glucose---insulin---potassium (GIK) solution(10U insulin and 10mEq KCl added to 500mL; 5% dextrose in water) was appliedtotheGIpatientswithdiabetesmellitus.The infu-sionratewassetto40mLh−1whenthebloodglucoselevel wasbetween 80 and100mgdL−1.The rate wasincreased to60mLh−1whenthebloodglucoselevelwasbetween100 and120mgdL−1.When thebloodglucoselevelwashigher than120mgdL−1,additionalinsulininfusionwasstartedas showninTable1.

Liberal glucose regimen was maintained in the GII by starting the insulin infusion when blood glucose level wasgreaterthan180mgdL−1.Insulininfusionwasapplied

accordingtotheratesshowninTable2.Diabeticpatientsin theliberalgroupweremanagedwithaninfusionoftheGIK solutionatarateadjustedtotheirglucoselevel.The infu-sionrate was40mLh−1 whenthe bloodglucose levelwas

between80and100mgdL−1,60mLh−1whentheblood

glu-coselevelwasbetween100and120mgdL−1,80mLh−1when

thebloodglucoselevelwasbetween120and150mgdL−1,

and100mLh−1whenthebloodglucoselevelwasbetween

150and180mgdL−1.Additionalinsulininfusionwasstarted

whenthe bloodglucoselevelwashigherthan 180mgdL−1

asshowninTable2.

Followingsurgery, patientsreceived aninsulin regimen applied as shown in Table 3. Blood glucose levels were measured inevery30min duringthestudyperiodfroman arterialbloodsamplewhichwasobtainedfromthepatient’s arterialline.Thesamplewasanalyzedinastandardblood gasanalyzer(ABL707,Radiometer,Copenhagen,Denmark). Intraoperatively, whenever the blood glucose level was below 60mgdL−1, 50mL bolus of 50% dextrose in water

wasused.Postoperatively,whenthebloodglucoselevelwas <80mgdL−1,50mLbolusof30%dextroseinwaterwasused

Table 3 Postoperative glucose control infusion for all patients.

Bloodglucose level(mgdL−1)

Insulinrate (Uh−1)

Insulinbolus (U)

80---99 0.5

---100---124 1

---125---159 2

---160---199 4

---200---234 6

---235---274 8 3

>274 8 5

Neuropsychologicalassessment

Cognitivefunctionwasassessedbyan investigatorblinded totheperioperativeglycemicapproach.AninitialMMSEwas performed,andpatienteligibilitywasdeterminedaccording tothescoreobtainedonthisfirstassessment.TheMMSEisa quantitativeandpracticaltestingusedtodetectapatient’s cognitivestatussuchasorientation,memory,attention, lan-guage,andvisuo-spatialfunctioning.Ifpatientsscoredmore than23ontheMMSE,theywereconsideredeligibleforthe study and wereassessed with acomprehensive neuropsy-chologicaltestbatterythatincludedtheWeschlerMemory Scale(WMS) ---LogicalMemorysubtest(detectsshort-term andlong-termmemory, withtwodifferentstoriespre-and postoperatively),theClockDrawing Test(detectsplanning ability), the WordList Generation Test (detects sustained attentionalsocalledperseverance),theDigitSpansubtest (detects global attention, concentration) and the Visuo-SpatialSkillsTest(detectsperceptualfunctions).

ExceptfortheMMSE,allpatientswereexaminedtheday beforesurgery(baseline),postoperativelyatthefirstweek (early), and at 12thweek (late). All evaluation was con-ducted by the same anesthesiologist who was blinded to perioperative glycemic managementand whowastrained and supervisedby the faculty’s Neurology Clinic’s consul-tantsduringtheentirestudyperiod.Theneuropsychological test battery lasted approximately 45min. All tests were administeredinsametimeofdayandsamelocation,a pri-vateroomatsurgicalservice.

Postoperative cognitive dysfunction(early or late)was defined as a drop of 1 standard deviation from baseline on twoor more neuropsychological tests as described by Höckeretal.intheirrecentstudy.14 Becauseofthelackof anon-surgicalcontrolgroup,thecognitivefunction evalu-ationwasperformedonlyasabetween-groupcomparison. Thestandard deviation(SD)ofeachpreoperative testwas calculated,andthenumberofpatientswhodeterioratedor improvedpostoperativelywasdetermined.14

The primaryoutcomewasdeterminedastheincidence ofearlyandlatePOCDandsecondarywasthefrequencyof hypoglycemicepisodesseenduringstudyperiod.Datawere analyzed withthe Prisma5.0 statistic package(Graphpad SoftwareIncorp,Layola,CA,USA).Allvaluesarepresented as the mean±standard deviation. Categorical data were analyzed with Fisher’s exact test and the Mann---Whitney UtestandrepeatedmeasuresofANOVAtest wasusedfor

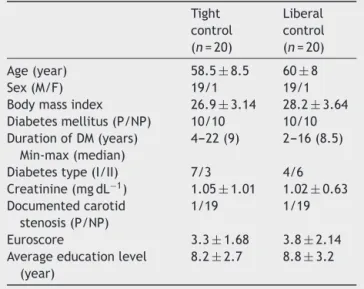

Table4 Demographicandpreoperativedata.

Tight control (n=20)

Liberal control (n=20)

Age(year) 58.5±8.5 60±8

Sex(M/F) 19/1 19/1

Bodymassindex 26.9±3.14 28.2±3.64 Diabetesmellitus(P/NP) 10/10 10/10 DurationofDM(years)

Min-max(median)

4---22(9) 2---16(8.5)

Diabetestype(I/II) 7/3 4/6 Creatinine(mgdL−1) 1.05±1.01 1.02±0.63 Documentedcarotid

stenosis(P/NP)

1/19 1/19

Euroscore 3.3±1.68 3.8±2.14 Averageeducationlevel

(year)

8.2±2.7 8.8±3.2

P,present;NP,notpresent.

Table5 Operativedata.

Tight control (n=20)

Liberal control (n=20)

Operationtime(min) 304.7±53.4 280±51 CPBtime(min) 119±17.6 110±9.7 Crossclamptime(min) 59.75±10.6 56.8±7.9 Minimumtemperature

duringCPB(◦C)

29.05±0.97 28.95±1.2

Minimumhematocrit duringCPB(%)

29.29±1.72 29.46±1.65

Proximalanastomosis number

2.7±0.73 3.05±0.75

Needfordefibrillationat theendofCPB(P/NP)

5/15 4/16

Inotropeuse(patients) 17 18 Fluidbalanceattheend

ofsurgery(mL)

1758±580 1424±414

Mechanicalventilation timeinICU(h)

6.85±1.42 6.95±1.6

P,present;NP,notpresent;CPB,cardiopulmonarybypass.

comparingcontinuous data. A p-value less than 0.05 was acceptedassignificant.

Results

Table 6 Blood glucose levels (mgdL−1) during study period.

Tight control:GI (n=20)

Liberal control:GII (n=20)

T0---baseline 124.65±26.09a 125.08±24.50 T1---30min 110.95±19.69a,c 156.75±22.08b T2---60min 108.15±22.86a,c 167.25±25.63b T3---120min 108.20±29.21a,c 153

±25.29b T4--- 180min 118.6±27.17a,c 169.83±28.93b T5--- 240min 117.2±22.87a,c 164.33

±29.50b T6--- Endofsurgery 115.45±12.74a,c 163.08±25.63b T7---ICU1sthour 108.75±12.36a,c 169.5±28.55b T8---ICU12thhour 121.20±15.81a,c 164.16±25.49b T9---ICU24thhour 142.90±17.90d 160.41±26.83b

ap<0.001comparedtoT9. b p<0.01comparedtoT0. c p<0.0001comparedtoGII. d p=0.03comparedtoGII.

neuropsychologicalprognosisduringcoronaryarterysurgery didnotshow anysignificant differencebetween the tight (GI)andliberalglucosecontrol(GII) groups.Therewasno majorcardiac (newmyocardial ischemia, serious arrhyth-mias, refractory low output state) or neurologic (stroke) complicationsobservedduring perioperativeperiodinany patients.

Blood glucose values obtained during study period is showninTable6.Hypoglycemicepisodes(<60mgdL−1

intra-operatively,<80mgdL−1inthepostoperativeperiod)were

recordedin4patientsinthetightcontrolgroupduringthe studyperiodandappropriatelytreatedaccordingtothe pro-tocol.None oftheliberalgroupexperiencedhypoglycemic attack. All 4 hypoglycemia cases were observed during surgery,andnohypoglycemiaoccurredinthepostoperative period.Thestatisticalcomparisonoftheincidenceof peri-operativehypoglycemicattacksbetweengroupsshowedno difference(p=0.104).Althoughstatisticallywithout signif-icance,thedifferenceinhypoglycemiafrequencybetween thegroupsseemsnotable.

Atthepostoperativefirstweek,neuropsychological test-ingrevealed that 10 patients (50%) in GIand 11 patients (55%)inGIIhadacognitivedeclineaccordingtopre-defined criteriadescribed.12TheincidenceofearlyPOCDatthefirst postoperativeweekwassimilarandindependentofglycemic management.

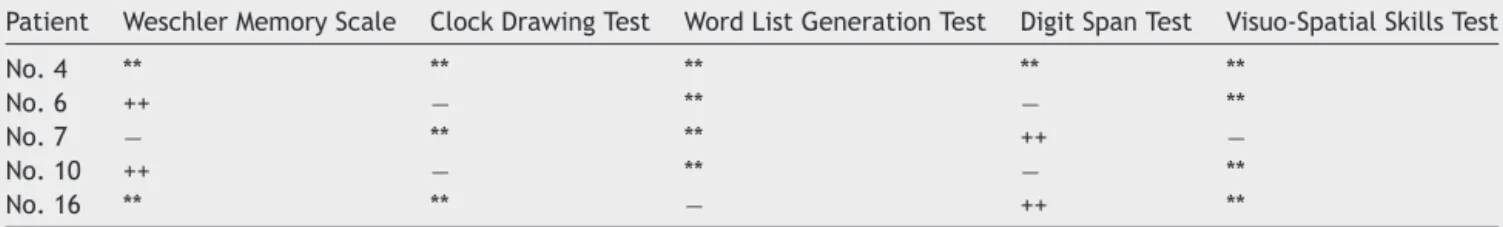

Late neuropsychological evaluation 3 months after surgery revealed that the cognitive dysfunction persisted in 5 patients (25%) in GII while all patients in GI had returnedtonormalcognition(p=0.047).Twoofthese sta-blePOCDpatientshadahistoryofdiabetestypeII.Scrutiny oftheneuropsychologicaltestsfor thisstablePOCDofGII showedthatonepatientwasimpairedinallof5tests, fol-lowedby onein3of 5,andtheremainingthreein2of 5 (Table7).

Discussion

In this pilot study examining the effect of perioperative glycemicmanagementonpostoperativecognitive dysfunc-tion(POCD)inpatientsundergoingcoronaryarterysurgery, no difference in the incidence of early POCD was found between the tight and liberal control groups. However, assessmentsat 3monthsaftersurgeryshowedareturnto preoperativelevelsinallpatientsinthetightcontrolgroup. Conversely5oftheliberalgrouphadpersistentPOCDatlate assessment.Asexpected,hypoglycemicepisodesweremore frequentinthetightglucosecontrolgroupduringthestudy period,althoughthedifferencedidnotreachstatistical sig-nificance.

Cognitiveimpairmentoccurringaftercardiacsurgery is thought to result from a combination of factors such as global hypoperfusion, cerebral microembolism, imbalance betweencerebral oxygendemandandconsumption during rewarming,andpossibleblood-brainbarrierdysfunction.8,15 ItisestimatedthatPOCDoccursin7---28%ofpatients7---10 daysaftergeneralsurgery.16 Inpatientsundergoingcardiac surgery, muchhigherincidencerates suchas20---70%have been observed.17 Concordant withthesereports,52.5% of our patients (21/40) in the overall study population had POCDduringtheearlypostoperativeperiodwithoutany dif-ferencebetweengroups.Thisfindingappearstosuggestat first glance the absence of an association between early postoperativecognitivedeclineandperioperativeglycemic control; this is probably due tothe major role of hypop-erfusion and microembolism in the development of early POCD.

This study was based on the hypothesis that glycemic control could influence the subsequent course of early POCD, which occurs in nearly half of the cases, either assuming a course toward recovery or persistence at 3 months after the surgical procedure. Intermediate and long-term assessments of cognitive functions generally spanaperiodof3---12months,andthereportedlong-term incidence rates for POCD are aslow as 24% at 6 months

Table7 TestresultsforpatientswithlatePOCDintheliberalcontrolgroup.

Patient WeschlerMemoryScale ClockDrawingTest WordListGenerationTest DigitSpanTest Visuo-SpatialSkillsTest

No.4 ** ** ** ** **

No.6 ++ − ** − **

No.7 − ** ** ++ −

No.10 ++ − ** − **

No.16 ** ** − ++ **

compared to early postoperative results.18 In our study, cognitive dysfunction was present in 25% of the patients (5/20) in the liberal control group, while no patients in the tight glucose control group had identifiable cognitive dysfunction at 3 months after surgery. We believe that this,i.e., significantly bettercognitive status inthe tight glucosecontrolgroup,isthemostimportantfindingofour study.

Lactate accumulation and intracellular acidosis due to hyperglycemiahavebeenshowntoexertdirecttoxiceffects on the ischemic brain in stroke cases which is further complicated by the neurotoxic effects of increased cir-culatory free fatty acid concentration due to inadequate insulin secretion.19 Although the mechanisms responsible forcerebralischemiaduringcardiacsurgeryaredifferent, avoidance of hyperglycemia in a hypoperfused brain dur-ingcardiopulmonarybypassmaybeexpectedtoattenuate some of the undesired effects of hyperglycemia. Clinical or experimental studies examining the adverse effects of hyperglycemia on ischemic and/or inflammatory cerebral injury have suggested that the principal mechanisms of hyperglycemia-inducedneurotoxicityincludethedisruption of the blood-brain barrier20 and increased concentration ofexcitatoryaminoacids.21 Althoughdebatable, cognitive decline persisting at third months postoperatively could easilyacceptedaspermanent,andduetoaforementioned mechanisms tightglucose control lookslike improve neu-rocognitiverecovery.

In a retrospective study by Puskas et al. that exam-inedtheassociationbetweenintraoperativehyperglycemia and cognitive dysfunction, intraoperative hyperglycemia was shown to correlate with late (6 weeks) cognitive dysfunction in patients without diabetes.22 The untoward effectsofhyperglycemiaonfocalandglobalcerebralinjury, whichoccurscommonly duringcardiacsurgery, havebeen proposed as a possible explanatory mechanism for their results. Interestingly, non-diabetic patients experienced more severe cognitive dysfunction comparedto diabetics inthatstudy.The latterfindingwasattributedtothelow thresholdvalue(200mgdL−1)ofhyperglycemiafordiabetic

patientsforwhomthecentralnervoussystemmayberather accustomedtoglycemiaofthislevel.22 Inourstudy,there washomogeneousdistributionofdiabeticandnon-diabetic patients across the groups, and early POCD occurred at a similar frequency in both subjects. However, of the 5 patientswithlatePOCDintheliberalgroup3werediabetic, and2werenon-diabetic.

In anotherstudy byButterworth etal.23 involving non-diabeticpatientsundergoingcardiacsurgery,insulininfusion or placebo was given for blood glucose levels exceed-ing 100mgdL−1 during the cardiopulmonarybypass (CPB),

andnewoccurrenceofneurological,neuro-ophtalmological, and neurobehavioral disorders were assessed at weeks 1 and 6 and at month 6 post-surgically. The authors con-cludedthattheglucosecontrolstrategyusedforpreventing hyperglycemia during CPB had no effect on the neuro-logic prognosis. The disagreement between these results with ours and Puskas et al.’s may arise from differences in defining POCD and methodological differences such as the restriction of the blood sugar control strategy to the durationofCPB.

Neuropsychological tests are an essential part of the assessmentofcognitivefunctions.However,learnabilityof cognitivetests,particularlyofthoseassessingthememory, isawell-knownphenomenon.Notsurprisingly,inourstudy, participants scored higher when they were exposed to memoryanddigit tests againlater in thestudy.Research hassuggestedthatpreoperativeanxietyordepressionmay alsoexplainlowerinitialscores.24Despitethedivergenceof theconclusionsinstudiesexaminingwhetherthediagnosis ofPOCDrepresentsareal‘‘disorder’’ orit isadiagnostic categoryderivedfromtheinvalidityofthetests,noother methodsproducingmore objectiveand/or validdatathan thosecurrentlyavailablehavebeendevelopeddespitetheir limitations.Inourstudy testsarepredisposedtoevaluate allintellectual domainssuch asmemory,vigilance, math-ematicalthinking,andpsychomotorabilities.Althoughthe improvement in subsequent test results compared to the baselinecanbeexplainedbasedona‘‘learningeffect’’,25 thisimprovementwaslimitedtopatients inthetight glu-cosegroupinour study,suggesting that theperioperative glycemic control strategy might have contributed to the improvement.

Educational level is an important preoperative factor forPOCDbut conflictingdata existsinthis area.Newman etal.indicated that higher levelof education canplay a protective role against late POCD as seen in Alzheimer’s disease18 althoughhigher levelofeducationwasfound an independentriskfactorforPOCDinlowriskCABGpatients in Boodhwani et al.’s study.26 Our study population, with anaverageofeducationalperiodconsisting8yearsinboth groups represents well the typical profile of the country whichisstatedas7.6yearsinarecentreport.27

Otherconsiderationsin studiesexamining theglycemic management are target glucose levels, the treatment approachtoreachormaintainthesetargets,and monitor-ingmethods.Previously,targetbloodglucoselevelsbetween 80and110mgdL−1wereused,andasignificantreductionin

mortalitywasobservedinintensivecareunitpatientswhen thesetargets are adopted.28 However, since more recent studiessuggested that suchtight controlnot only fails to provideaprognosticadvantagebutalsoisassociatedwith anincreasedriskofhypoglycemia,newtargetvalues,i.e., between 140 and 180mgdL−1, have been defined.13 Gen-erally, the current definition of ‘‘tight glucose control’’ involvesbloodglucosevaluesbetween110and200mgdL−1

incardiacsurgeryandin intensivecare unitpatients.29 In ourstudy,blood glucosetargets similartothoseproposed byOuattaraetal.wereused.30ThePortlandinsulininfusion protocol31wasadoptedforbloodglucoseregulationinwhich monitoringwasperformedevery30min.Morepatientsinthe tightglucosecontrol groupexperiencedepisodesof hypo-glycemiawiththisprotocol,althoughthedifferencewasnot significant.

POCDmadeat thirdpostoperativemonthdueto organiza-tionaldifficultiescanbeconsideredrelativelyshort.Onthe other hand,a recentsystematic review revealed thatthe rangefor latePOCDassessment aftercardiacsurgeryvary between6weeksto1year.32

In conclusion, regardless of the methodused for peri-operative blood glucose control, almost half of patients undergoing coronary artery surgery, showed a significant declinein cognitive performance one week after surgery, meeting the diagnostic criteria for POCD. However, 3 monthsafter theprocedure, patients in thetight glucose control group were more likely to return to their base-line cognitive function compared to those in the liberal control group. These results suggest that intraoperative blood glucose control with established positive effects on neurological functions and wound healing in patients undergoingcoronary artery surgery may also play a simi-larroleinthepreservationandquickrecoveryofcognitive functions.

Funding

This researchreceivednospecific grantfrom anyfunding agencyinthepublic,commercial,ornot-for-profitsectors.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.Rasmussen LS, Johnson T, Kuipers HM, et al. ISPOCD2 (International Study of Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction) Investigators:Doesanaesthesiacausepostoperativecognitive dysfunction? A randomised study of regional versus general anaesthesiain438elderlypatients.ActaAnaesthesiolScand. 2003;47:260---6.

2.Krenk L, Rasmussen LS, Kehlet H. New insights into the pathophysiology ofpostoperativecognitive dysfunction.Acta AnaesthesiolScand.2010;54:951---6.

3.Phillips-ButeB,Mathew JP,BlumenthalJA,etal.Association of neurocognitive function and quality of life 1 year after coronaryarterybypassgraftsurgery.PsychosomMed.2006;68: 369---75.

4.MonkTG,WeldonBC,GarvanCW,etal.Predictorsofcognitive dysfunction after major noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:18---30.

5.Vanderweyde T, Bednar MM, Forman AS, et al. Iatrogenic riskfactorsforAlzheimer’sdisease:surgeryandanesthesia.J AlzheimersDis.2010;22Suppl.3:91---104.

6.Funder KS, Steinmetz J, Rasmussen LS. Cognitive dys-function after cardiovascular surgery. Minerva Anestesiol. 2009;75:329---32.

7.Newman MF, Mathew JP, Grocott HP, et al. Central ner-vous system injury associated with cardiac surgery. Lancet. 2006;19:694---703.

8.Grocott HP, Homi HM,Puskas F.Cognitive dysfunction after cardiac surgery: revisiting etiology.Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth.2005;9:123---9.

9.OrhanG,Bic¸erY,Tas¸demirM,etal.Comparisonof neurocog-nitivefunctionsinpatientsundergoingcoronaryarterybypass

surgeryundercardiopulmonarybypassorbeatingheart.Turk GogusKalpDama.2007;15:24---8.

10.AkhtarS,BarashPG,InzucchiSE.Scientificprinciplesand clini-calimplicationsofperioperativeglucoseregulationandcontrol. AnesthAnalg.2010;110:478---97.

11.ShineTS,UchikadoM,CrawfordC,etal.Importanceof periop-erativebloodglucosemanagementincardiacsurgicalpatients. AsianCardivascThoracAnn.2007;15:534---8.

12.SchrikerT,CarvalhoG.Pro:Tightperioperativeglycemic con-trol.JCardiothoracVascAnesth.2005;19:684---8.

13.FinferS, ChittockDR,Su SY, etal. Intensive versus conven-tionalglucosecontrol incriticallyill patients.NEngl JMed. 2009;26:1283---97.

14.Höcker J, Stapelfeldt C, Leiendecker J, et al. Postopera-tiveneurocognitivedysfunctioninelderlypatientsafterxenon versus propofol anesthesia for major non cardiac surgery: a double-blindedrandomizedcontrolledpilotstudy. Anesthesi-ology.2009;110:1068---76.

15.GaoL,TahaR,GauvinD,etal.Postoperativecognitive dysfunc-tionaftercardiacsurgery.Chest.2005;128:3664---70.

16.HanningCD.Postoperativecognitivedysfunction.BrJAnaesth. 2005;95:82---7.

17.Bruce K, Smith JA, Yelland G, et al. The impact of cardiac surgeryoncognition.StressandHealth.2008;24:249---66.

18.NewmanMF,Kirchner JL,Phillips-Bute B,et al. Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function aftercoronary artery bypassessurgery.NEnglJMed.2001;344:395---401.

19.Choi DW, Rothman SM. The role of glutamate neurotoxic-ity in hypoxic ischemic neuronal death. Ann Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:171---82.

20.DietrichWD,AlonsoO,BustoR.Moderatehyperglycemia wors-ensacuteblood-brainbarrierinjuryafterforebrainischemiain rats.Stroke.1993;24:111---6.

21.Li PA,ShuaibA, MiyashitaH, etal. Hyperglycemiaenhances extracellularglutamateaccumulationinratssubjectedto fore-brainischemia.Stroke.2000;31:183---92.

22.PuskasF,GrocottHP,White WD,etal.Intraoperative hyper-glycemiaandcognitivedeclineafterCABG.AnnThoracSurg. 2007;84:1467---73.

23.ButterworthJ,WagenknechtLE,LegaultC,etal.Attempted control of hyperglycemia during cardiopulmonary bypass fails to improve neurologic or neurobehavioral outcomes in patients without diabetes mellitus undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130: 1319---28.

24.FunderSK,SteinmetzJ,RasmussenLS.Methodologicalissues ofpostoperativecognitivedysfunctionresearch. Sem Cardio-thoracVascAnesth.2010;14:119---22.

25.RasmussenLS, Siersma VD,TheISPOCD group.Postoperative cognitivedysfunction:truedeteriorationversusrandom varia-tion.ActaAnaesthesiolScand.2004;48:1137---43.

26.BoodhwaniM,RubensFD,WoznyD,etal.Predictorsofearly neurocognitivedeficitsinlowriskpatientsundergoingonpump coronaryarterybypasssurgery.Circulation.2006;114Suppl. I:I-461---6.

27.http://www.tr.undp.org/content/turkey/tr/home/ countryinfo.html

28.Van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, et al. Inten-sive insulin therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1359---67.

29.Van den Berghe G, Schetz M, Vlasselaers D, et al. Inten-sive insulin therapy in critically ill patients: NICE-SUGAR or Leuven blood glucose target? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3163---70.

outcomeaftercardiacsurgeryindiabeticpatients. Anesthesi-ology.2005;103:687---94.

31.FurnaryAP,ZerrKJ,GrunkemeierGL,etal.Continuous intra-venousinsulininfusionreducestheincidenceofdeep sternal woundinfectionindiabeticpatientsaftercardiacsurgical pro-cedures.AnnThoracSurg.1999;67:352---60.