The sport of Open Water swimming is rapidly evolving primarily due to the recent inclusion of a 10-kilometer race to be held in the rowing basin at the 2008 Beijing Olympics. The men’s and women’s 10K race will consist of the top 25 Open Water swimmers selected through pre-Olympic qualification races organized by FINA. This report is meant to help educate and inform interested athletes, coaches, parents, race organizers, media representatives and administrators to more deeply understand the techniques, race strategies, training methodologies and equipment used by the world’s top Open Water swimmers.

THE OPEN WATER REPORT

The following is a condensed/excerpt from an article by USA Swimming Director of Physiology, Genadijus Sokolovas. We would like to acknowledge Dave Thomas, Steve Munatones, Dr. Jim Miller, Charlene Boudreau, Stacy Michael, Jennifer Thomas, Paul Asmuth, Mariejo Pasion, Terry Laughlin and Amy McCullough for their contributions. The complete paper will be posted in the Coaches Section at usaswimming.org.

USA Swimming • Volume 14 • Number 1 • Spring 2008

OPEN WATER ISSUE

2

PUBLISHER Chuck Wielgus

EDITOR Scott Colby

scolby@usaswimming.org

ART DIRECTOR Matt Lupton

GRAPHIC DESIGN Heidi Herboldsheimer

2008 Coaches Quarterly is USA Swimming, Inc., all rights reserved. No portion of this publica-tion may be reproduced in any way without the express consent of USA Swimming.

CQ Disclaimer: The views and opinions pub-lished in CQ are those of the authors and not by the fact of publication necessarily those of USA Swimming or its members. USA Swim-ming is not responsible for the content of any information published in CQ and such publica-tion does not imply approval by USA Swimming of said content or any organization with which the authors are associated.

THE OPEN WATER REPORT

PHYSIOLOGY OF A 10 K RACE ... 3

TRAINING FOR OPEN WATER ...4

SPORTS MEDICINE IN OPEN WATER ... 8

RACE STRATEGIES & PROCEDURES ... 8

NUTRITION FOR OPEN WATER ... 15

extras-• open water equipment ... 6

• two seconds of olympic pressure - on open water coaches ... 10

• websites/articles ... 13

• olympic open water racing history ...14

• spotlight on training ... 16

• usa swimming perspective ... 17

• how to establish open water in your Lsc ...24

PHOTO BY DOUG BENC/GETTY IMAGES

CONTENTS

USA SWIMMING’S

VALUED SPONSERS

PHYSIOLOGY OF A

10

K RACE

3 The 10k Open Water race requires

ap-proximately two hours of vigorous swimming. Depending on the conditions during the race (waves, currents, temperature, course, or competitors) the energy cost is variable. For most of the race, athletes will average just under their lactate threshold.

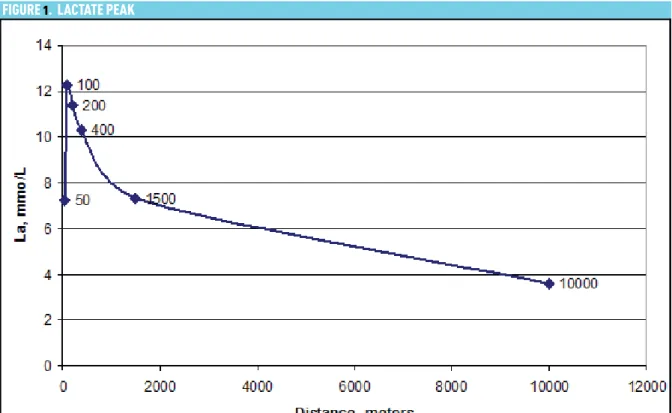

Lactate threshold is considered the upper limit of steady-state aerobic metabolism. If this threshold is crossed there will be rapid accumulation of many metabolites in the mus-cles and blood (Karp 1992). For running, lactate threshold is the best physiological predictor of distance running performance (Bassett 2000). Lactate threshold is responsive to training; even world-class athletes can increase their lactate threshold. Training at lactate threshold is the optimal intensity for improvement in endurance. Training at, or slightly faster than, the athlete’s current lactate threshold appears to be the best way to improve lactate threshold (Mader 1991).

The best Open Water swimmers have lower peak lactates in comparison with elite pool swimmers at the conclusion of their event. The ability to swim fast with low concentration of lactate and other metabolites is an advantage

in prolonged Open Water races. Most likely, Open Water swimmers are able to swim the race under lactate/anaerobic threshold and delay or even avoid the effect of acidosis on swimming performances. The average peak lactate after races of various distances for top men swimmers is presented in Figure 1. Lactate threshold for Open Water swimmers is closer to their maximum swimming velocity than for pool swimmers. The velocity which Open Water swimmers accumulate high lactate levels is greater than pool swimmers. Based on limited studies on Open Water swimmers, their lactate threshold is at 90-95% from the maximum velocity on 200 meters. Pool swimmers, espe-cially spri nters, reach lactate threshold at lower intensities.

In order to be successful in a 10K Open Water swimming race, an athlete must be able to maintain a high velocity at his or her lactate threshold. Therefore, training as indicated above to improve lactate threshold will be a primary focus for improving performance. Another predictor of distance performance is race economy. The less oxygen an athlete consumes to maintain a given pace, the more

economical he or she is. It has been shown that runners tend to be the most economi-cal at the speed at which they train the most (Johnston 1997). Athletes should spend time training at race pace in order to increase their economy at that pace. Running high mileage (>70 miles per week) seems to improve running economy (Jones 2000). These correlations could translate over to swimming. By training race pace as well as high volume, s wimmers could improve their swimming economy, which in turn could improve their pe rformance. Athletes will need to sprint at points of the race such as the start, around turn buoys, to pass, and at the fi nish. This r equires not only endurance, but the ability to burst to higher velocities. An athlete needs to be able to accelerate to a high ve locity quickly when necessary during the race. This physiological com bination of having a high lactate threshold mixed with the ability to reach a high velocity for short bursts makes success in the 10K Open Water Swim a challenge.

FIGURE

1

. LACTATE PEAK

Energy demand for Open Water swimming is different from the pool swimming (see the section on Physiological Parameters of Open Water swimmers). Basically, the longer the swimming event, the more important aerobic conditioning becomes. As mentioned above, there are also periods during the race which demand sprinting ability. Sprinting during the race requires good anaerobic conditioning. Therefore some anaerobic sets should be present in the training of Open Water swimmers. It is important for coaches to know what aerobic training pace is and what anaerobic pace is. One of the markers of anaerobic work is the release of lactic acid (lactate) during the swim. Lactate is a by-product of high-intensity work in anaerobic conditions (oxygen deficit). Athletes swim aerobically when there is enough oxygen delivered to the working muscles. Once swimming pace increases, athletes begin to breathe harder to deliver more oxygen. However, there are limits of the cardio-respiratory system. At higher swimming intensities, the cardio-respiratory system is not able to deliver enough oxygen to the muscles. As a result, muscles release more lactate at higher swimming intensities.

The swimming velocity at the onset of accumulation of lactate is called anaerobic threshold or lactate threshold. From a practical point of view, there are several methods to evaluate swimming velocity at the anaerobic threshold. One of the most precise methods for determining lactate at various swimming velocities is a Step Test or Lactate Heart Rate Profile.

T-30 is another practical test to evaluate swimming velocity at anaerobic threshold. If swimmers maintain their best velocity for about 30 minutes, the pace will be close to their anaerobic threshold. Elite level swimmers may cover up to 3,000 meters in a 30 minute test, while younger swimmers may swim between 2,000 and 2,500 meters during the test. For example, a coach may ask an athlete to swim 2,500 meters on the best average pace. To calculate swimming velocity at anaerobic

ENERGY ZONES Set Distance (m) Set Duration (min) HR (bpm) HR (% max) Work: Rest Sample Set

AEROBIC 500-4000 Variable ≤ 160 ≤ 80 10-30 sec rest 6-10 x 400/ 20 sec

rest or 3-5 x 1000/ 30 sec rest AEROBIC/

ANAEROBIC MIX

600-2000 8-40 160 – Max 80-100 15-60 sec rest 8-12 x 200/ 30 sec

rest or 12-20 x 100/ 30 to 45 sec rest

ANAEROBIC 200-600 2-15 Max 100 2:1 – 1:1 4 x 100/ 2 min rest

or 10 x 50/ 30 sec rest

TABLE

1

. CHARACTERISTICS OF THREE ENERGY SYSTEMS/ZONES

threshold for 100 m, the coach should divide the result by 25 (twenty-five one hundreds):

• • • Time on 2,500– 27:55.0

• • • Anaerobic Threshold Pace for 100 = 27:55.0 / 25 = 1:07.0

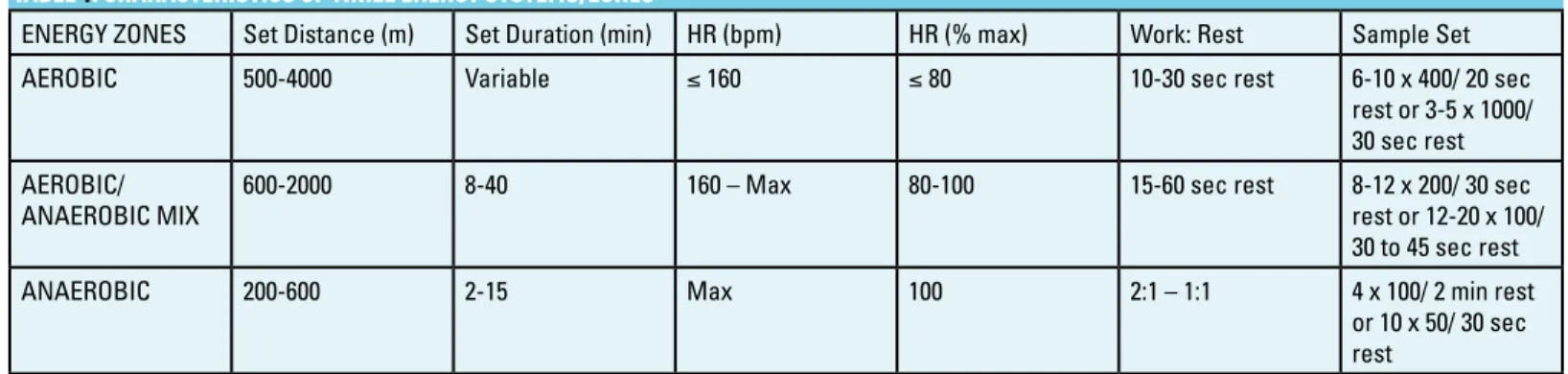

Swimming under anaerobic threshold velocity will not accumulate a large amount of lactate. This swimming velocity is called the aerobic energy system or zone (REC and EN1). Aerobic swimming sets will include longer distances at easy and moderate pace with heart rate (HR) up to 80% of maximum. Once the heart rate reaches 85% to 90%, the muscles begin working in an oxygen deficit condition and lactate begins accumulating. This energy system/zone is called aerobic-anaerobic mix (EN 2 and EN3). When athletes swim at intensities of maximum HR and higher, release of lactate increases significantly and reaches individual peak. This energy system/zone is called anaerobic (SP1 and SP2).

The training of Open Water swimmers may include up to three energy systems/zones. Details of each energy system/zone are presented in Table 1.

SEASON PLAN

Continuous improvement in

swimming performances throughout a season depends on the swimming and dryland workload volume in the various energy zones and the adaptation of athletes to this workload. Although there are many ways to develop faster swimmers, to attain the maximal effect of training, workload volume should be distributed during the season in an optimal manner. Ideally, daily and weekly workload volumes should correspond to the training condition of the individual swimmers.

When planning training sequences, coaches should first determine the number of training seasons within the current training year. Since there is a paucity of scientific investigation into the number seasons a coach should conduct in one year, coaches have traditionally divided this period into 2-4 seasons or training sequences per year, and have based their

decisions on personal experience or anecdotal evidence gained from information provided by other coaches. It is also traditional to use a “major meet” as the focus of each season, and to p repare for a peak performance at the end of each training sequence.

Duration and number of seasons depends on the athletes’ adaptation. Individual rate of adaptation is highly variable. Athletes will even adapt differently to the same training plan. Our studies show that individual rate of adaptation is related to athlete’s age, gender, performances, phase of season, training history and some other parameters. In analyzing the progression of athletes’ working capacity, we found that there are two main training strategies:

• • • Strategy 1 – Increasing the workload volume in various energy zones. This strategy is typical during the first phase of the season (aerobic endurance development), when it’s the coaches aim to increase workload volume and the duration of workouts with constant intensities in various energy zones.

• • • Strategy 2 – Increasing intensity with the same workload volume. This strategy is typical for the second phase of the sea son (Taper phase), when athletes aim to swim faster and increase intensities in various energy zones with constant or even lower workload volumes. Over a period of 25 years, programs that employed this system of athlete development were tracked, and the records from

thousands of athletes were collected to develop a comprehensive understanding of athlete adaptation. The data has enabled Dr. Genadijus Sokolovas to develop a computer program that focused on training design. You can read more about the Seasonal Plan Designer software at the Coaches Section of USA Swimming web site:

http://www.usaswimming.org/USASWeb/ EcommerceUI/ProductDetail.aspx?TabId=7 &Alias=Rainbow&Lang=en&catId=35&Item Id=91

4

# OF WEEK DATE #OF WORKOUTS Total Aerobic REC, EN1

Mix EN2-3

Anaerobic SP1-2-3

1 9/4/2006 6 21,450 11,600 8,900 950

2 9/11/2006 7 30,350 20,400 9,000 950

3 9/18/2006 8 38,200 28,000 9,200 1,000

4 9/25/2006 8 45,000 34,500 9,500 1,000

5 10/2/2006 9 51,150 40,200 9,900 1,050

6 10/9/2006 10 56,300 44,900 10,300 1,100

7 10/16/2006 10 60,950 48,900 10,900 1,150

8 10/23/2006 11 64,950 52,100 11,600 1,250

9 10/29/2006 11 68,500 54,700 12,500 1,300

10 11/5/2006 12 71,600 56,600 13,600 1,400

11 11/12/2006 12 74,250 57,900 14,800 1,550

12 11/19/2006 12 76,650 58,800 16,200 1,650

13 11/26/2006 12 78,800 59,300 17,700 1,800

14 12/3/2006 12 80,650 59,500 19,200 1,950

15 12/10/2006 10 64,100 46,400 16,100 1,600

16 12/17/2006 12 83,600 59,400 22,000 2,200

17 12/24/2006 12 84,800 59,300 23,200 2,300

18 12/31/2006 10 67,000 46,200 18,900 1,900

19 1/7/2007 12 86,800 59,200 25,100 2,500

20 1/14/2007 12 87,650 59,300 25,800 2,550

21 1/21/2007 10 68,950 46,300 20,600 2,050

22 1/28/2007 12 88,950 59,500 26,800 2,650

23 2/4/2007 10 68,400 46,600 19,800 2,000

24 2/11/2007 8 53,300 36,200 15,500 1,600

25 2/18/2007 7 42,200 28,750 12,200 1,250

SWIMMING VOLUMES (m)

TABLE

2

. TWENTY-FIVE WEEK SEASON PLAN FOR ADULT OPEN WATER SWIMMER (FALL-WINTER)

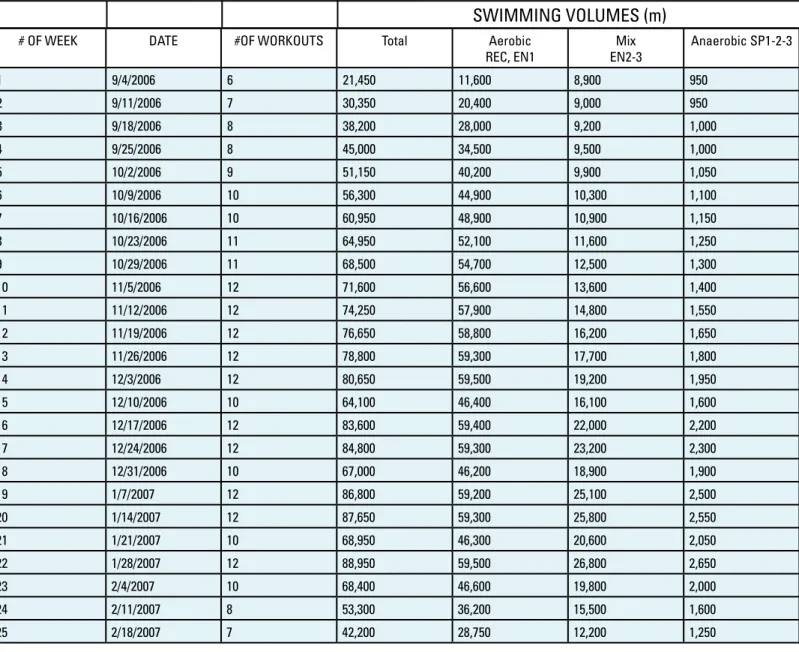

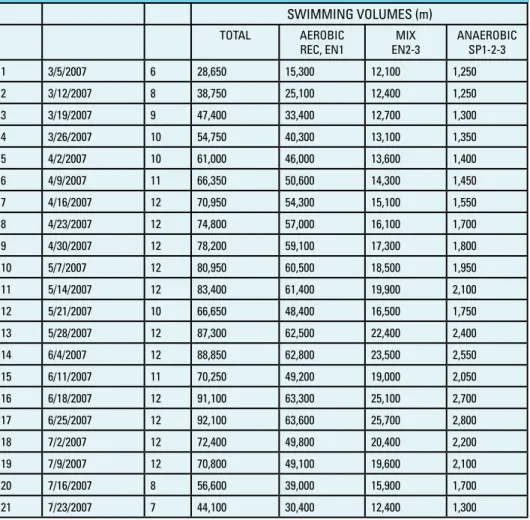

Table 2 and table 3 provide examples of two seasonal plans for adult Open Water swimmers generated using the Seasonal Plan Designer. TAPER

For this article, taper is considered a training period with reduced training volume prior to a major competition. Based on this definition, taper begins as soon as workload volumes d ecrease before the competition. The last three weeks of the season in tables 2 and 3 fall into taper. Pool swimmers, especially sprinters, may maintain a fairly high intensity at the beginning of the taper. However, their taper is longer than for distance swimmers or Open Water swimmers. The purpose of the taper is to rest athletes after a long training season and to maximize performances or supercompensate for their training. If taper is too long, detraining may occur. Studies indicate that endurance is more sensitive to detraining than strength and speed. With low training volumes, detraining occurs rather fast in endurance events.

Endurance decrease coincides with decline in many physiological parameters (VO2 max, heart stroke volume, cardiac output, delivery of O2 to the muscles, anaerobic threshold, etc.). Based on USA Swimming’s and other scientists’ studies, here are recommendations for taper of Open Water swimmers:

• • • Duration of taper should be between 2 and 3 weeks

• • • Decrease of swimming volumes during the taper should coincide with decrease of intensity

• • • More Open Water sessions (lake, rowing base, etc) should be done during the taper

• • • More Open Water drills (starting, drafting, and finishing techniques, sighting, turns around buoys, feeding

techniques, etc) should be done during the taper

NUMBER OF RACES PER SEASON Choose Open Water races during the year by mimicking a pool season. Open Water swimming depends upon weather conditions and water temperature, so the summer and warmer seasons (depending on the regional climate) will dictate when most races are offered. If an athlete is swimming Open Water events in c onjunction with pool events at the same competition, determining how many races the swimmer participates in will be dependent upon what the focus is: pool vs. Open Water. If the primary focus is Open Water, the swimmer can race more often. Even though races are longer, it’s usually just one or two events as opposed to multiple events over many days. Gaining experience may be most valuable. SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES

WITH POOL TRAINING

Proper technique is important for both pool and Open Water training, but Open water conditions are much more volatile than in

TOTAL AEROBIC REC, EN1

MIX EN2-3

ANAEROBIC SP1-2-3

1 3/5/2007 6 28,650 15,300 12,100 1,250

2 3/12/2007 8 38,750 25,100 12,400 1,250

3 3/19/2007 9 47,400 33,400 12,700 1,300

4 3/26/2007 10 54,750 40,300 13,100 1,350

5 4/2/2007 10 61,000 46,000 13,600 1,400

6 4/9/2007 11 66,350 50,600 14,300 1,450 7 4/16/2007 12 70,950 54,300 15,100 1,550 8 4/23/2007 12 74,800 57,000 16,100 1,700 9 4/30/2007 12 78,200 59,100 17,300 1,800

10 5/7/2007 12 80,950 60,500 18,500 1,950

11 5/14/2007 12 83,400 61,400 19,900 2,100

12 5/21/2007 10 66,650 48,400 16,500 1,750

13 5/28/2007 12 87,300 62,500 22,400 2,400

14 6/4/2007 12 88,850 62,800 23,500 2,550

15 6/11/2007 11 70,250 49,200 19,000 2,050

16 6/18/2007 12 91,100 63,300 25,100 2,700

17 6/25/2007 12 92,100 63,600 25,700 2,800

18 7/2/2007 12 72,400 49,800 20,400 2,200

19 7/9/2007 12 70,800 49,100 19,600 2,100

20 7/16/2007 8 56,600 39,000 15,900 1,700

21 7/23/2007 7 44,100 30,400 12,400 1,300

SWIMMING VOLUMES (m)

Workload volumes are reduced during the recovery weeks: #12, #15, and #18.

6

OPEN WATER EQUIPMENT

GENADIJUS SOKOLOVAS AND STEVE MUNATONES

Other than a swim suit and goggles, the mandatory equipment of Open Water swimmers in international races includes a swim cap and transponders.

All swimmers must start the race with swim caps, but do not have to finish the race with their swim caps. If the water is warm, some swimmers quickly remove their swim caps due to the heat.

In international races, each swimmer will receive two transponders by FINA for timing and placing purposes. The transponders are generally the weight and size of a black plastic waterproof wristwatch. Each swimmer will receive 2 transponders at the start and they

are required to finish with both transponders. The swimmer will be disqualified if either transponder is lost during the race. In order for the transponders to stay on the wrists, it is advisable that the transponders are taped snugly to the wrists with waterproof tape. The tape will also help prevent the wrist strap from fl apping while swimming, which may cause frustration during the race.

If the water is cold, it is advisable that you use silicon ear plugs. Use of ear plugs will help make the water feel warmer and is a trick that many channel swimmers and surfers use. Depending on the rules of the competition, 2 swim caps will also help the swimmer feel a bit warmer.

In general, the water temperature at most major national and international competitions will be comfortably warm, although there are always exceptions. As such, most elite international swimmers do not wear a full bodyskin suit. Most male swimmers wear knee length “jammers”, full leg skin suits or regular briefs. Female swimmers generally wear full leg skin suits, suits that cover only to the knee or regular/traditional racing suits.

Chafing around friction points (e.g., necks, underarms, inside of thighs) can be prevented by applying Vaseline or lanolin before the race. Lanolin can be purchased at medical supply stores. It is advisable for a coach, parent or and the longer it is maintained the better

the performance. Tempo training and race technique should be incorporated into training. Mimic the actual race conditions, tempos and technique as much as possible. While both pool swimming and Open Water training occur primarily in the pool, racing Open Water is

a completely different sport with an entirely different set of things to consider.

INCORPORATION OF OPEN WATER AND POOL TRAINING

• • •When it comes to Open Water, pool training is primarily used for endurance and the raw

speed necessary for sprinting at the end of Open Water skills into the training.

• • •Practice Open Water starts by treading water in between sets and at the start of each workout.

• • •Mimic race strategy and conditions as much as possible.

• • •Practice getting a fast start.

• • •Do an entire pool workout without touching or pushing off the walls.

• • •Change tempo and pace periodically ANTHROPOMETRIC PARAMETERS FOR OPEN WATER SWIMMERS

In general, elite level Open Water swimmers are shorter and lighter than pool swimmers. That is especially true if compared to the swimmers over shorter distances (sprinters and middle distance swimmers). In comparison with pool swimmers, Open Water swimmers have lower parameters of muscle and skeletal mass. Lower muscle mass may be due to different type of t raining for longer distances. Studies on Open Water swimmers indicate that women have body fat between 17% and 23%, while men’s body fat is between 9% and 13%. A short summary on anthropometric parameters for Open Water swimmers is presented in Table 4.

OPEN WATER REPORT: TRAINING FOR OPEN WATER

TABLE

4

. ANTHROPOMETRIC PARAMETERS FOR OPEN WATER SWIMMERS *

STUDY HEIGHT, CM WEIGHT, KG PERCENT

MUSCLE MASS

PERCENT SKELETAL MASS

BODY FAT, %

FEMALES:

US 168.3 ± 2.8 63.5 ± 5.8 30.7 ± 3.8 8.4 ± 0.7 22.8 ± 2.3

RUSSIA 169.0 ± 4.6 59.7 ± 4.2 N/A N/A 17.1 ± 2.7

POOL SWIMMERS

171.5 ± 7.0 63.1 ± 5.9 42.6 ± 19.6 12.5 ± 1.0 N/A

MALES:

US 177.3 ± 7.1 71.2 ± 8.1 39.9 ± 8.4 10.2 ± 0.9 9.8 ± 2.0

RUSSIA 180.1 ± 6.5 70.4 ± 11.1 N/A N/A 12.7 ± 2.4

POOL SWIMMERS

183.8 ± 7.1 78.4 ± 7.1 45.8 ± 9.2 13.1 ± 0.9 N/A

* Data from Carter, L. & Ackland, T. (1994), Karaseva, I. etc. (2003), and Vanheest, J, etc. (2004).

7 a teammate to apply the Vaseline to lanolin

to the swimmer’s body. The coach, parent or teammate should apply the Vaseline or lanolin with a rubber glove or have a small towel readily available. The last thing a swimmer wants is for Vaseline or lanolin to get on the goggles right before the start.

Some swimmers also apply Vaseline on their ankles for defensive purposes. That is, if a competitor hits the legs or ankles, they will quickly learn not to repeat that if their hands get smeared with a small amount of Vaseline.

It is also advisable to have 2 sets of goggles at the start of the race – just in case there is some kind of goggle malfunction or Vaseline accident.

OPEN WATER REPORT: TRAINING FOR OPEN WATER

USA SWIMMING NATIONAL OPEN

WATER SELECT CAMP

DAVE THOMAS, CAMP DIRECTOR

dthomas@usaswimming.org

RACE STRATEGIES AND PROCEDURES

Open Water is a very different setting for mostathletes. Pool swimming involves comfortable water temperatures for specific competitions as well as water clarity, depth, and calm conditions. None of this applies in the Open Water setting, and the norms that we have come to codify and expect are gone. Open Water is a completely new venue and not everyone can make the transition. A discussion of medical concerns follows. These medical issues should be discussed openly between coaches, athletes, parents and medical support staff. Recognize that each body of freely flowing water has its own unique risks and challenges. These bodies of water may be alive in more ways than one. Considering all the variables, many of them uncontrollable, flexibility and adaptability are critical traits for becoming a successful Open Water athlete, coach or staff member. DEHYDRATION AND HYPERTHERMIA

The 10K swimming event carries the potential for dehydration, which is loss of fluid in the body, and for hyperthermia, which is unusually high body temperature. Warm water and high intensity swimming are contributing factors. Studies have shown that these two factors may seriously impair athletes’ performances. Many physiological changes occur with dehydration and/or hyperthermia, such as reduction in stroke volume, increase in heart rate, decline in anaerobic and lactate threshold, electrolyte imbalance, headache, and even fainting. All these changes in conjunction with fatigue and depletion of energy (muscles’ glycogen) will affect swimming performances. To avoid dehydration and hyperthermia, swimmers must have the right fluid/ energy replenishment plan (see more details in the nutrition part of this report).

HYPOTHERMIA

Hypothermia is another condition which may occur during the Open Water race. The factors

that contribute to hypothermia include low water temperature, long duration of Open Water race, chilly wind, pronounced fatigue, and low percent of body fat. According to the FINA regulation, a recommended minimum temperature of Open Water races is 14ºC (57.2ºF). Hypothermia is considered when the core body temperature drops below 35ºC (95ºF).

Mild hypothermia may be identified based on number physiologic signs, such as increased shivering, subjective cold and vasoconstriction. Severe hypothermia includes altered cognition, unusual behavior, weakness, apathy, reduced cardiac output, and even coma. Swimmers must stop swimming if there are signs of severe hypothermia. To treat severe hypothermia, swimmers must first be removed from the water. To treat hypothermia, dry warm clothes, warm drinks and baths, external heat devices (lamps, etc.) and other techniques may be used. In severe cases, advanced warming techniques and medical assistance is required.

The issues surrounding hyperthermia and hypothermia are complex and potentially dangerous. Prevention is the best option and it can be addressed by several methods.

• • • Acclimatization: Athletes vary considerably in their ability to tolerate cold or heat. The process of getting an athlete ready for the challenge ahead takes days, weeks, or months based upon the individual’s innate characteristics. Some never can tolerate extremes. Ways to achieve this include gradual exposure to increasingly cold (or warm) water over time, once again determined by the athlete’s ability to take the next challenge.

• • • Layered swim caps help in cold conditions but their use may be limited by the rules of the competition.

• • • Ear plugs decrease the middle and inner ear exposure to cold and thus lessen the dizziness and pain that can accompany

this exposure.

• • • While lanolin and other coating agents will lessen the impact of the cold, they do not actually decrease heat loss.

CHAFING

The combination of prolonged exposure, repeated rubbing with a variable stroke dictated by wave action, and salt can create a nasty skin wound. Common rubbing sites include suit lines, particularly straps, the shoulder area caused by the chin rubbing with breathing, the arm pit, inner thighs, and the back of neck caused by sighting. Various lubricants are effective, from lanolin which stays in place better than most, to Vaseline, Body Glide, bag balm, PAM, Channel grease, Cramer Skin Lube and other new and old products. These must be applied by a staff member since the athletes cannot easily remove the product from their hands, thereby affecting their feel for the water. To properly treat chafing, it must be treated as a laceration. Begin treating chafing with topical agents with anti-bacterial , anti-staph and anti-strep properties.

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

• • • Currents, eddies, rip tides, undertow

• • • The higher the salt content the greater the problem of swelling of the exposed membranes of the eye and mouth. Periodic washing out of the mouth with fresh water feedings will help.

• • • Excessive ingestion of salt water may result in vomiting, which quickly can cause electrolyte disturbances and dehydration.

• • • Buoyancy as a result of salinity

• • • Rapid changes in all of the factors as influenced by wind

Athletes should check with the USADA Drug Reference Line (800-233-0393) or Drug Reference Online (www.usantidoping.org/dro) before utilizing any medication including eye drops.

THE START

If there is an in-the-water start, a rope will be on the surface. Every swimmer must be touching the rope before the referee will start the race. Swimmers are free to position themselves at any spot along the starting rope. Jostling among swimmers will occur near the most advantageous spots.

If the start is from a dock or floating pontoon, the swimmers are assigned a starting position which is drawn at random. To avoid false starts, there is usually a “fast” or quick gun.

SPORTS MEDICINE IN OPEN WATER

8

PHOTO BY JIM MILLER MD

holding on a rope to start

starting from a pier

PHOTO BY JIM MILLER MD

Be ready for a quick start.

Most athletes start fast for positioning.

The pace is usually fast from the start. Distinct packs form immediately. The fastest swimmers quickly position themselves in the lead pack. They sprint in the beginning in order to avoid a huge traffic jam around the first few turn buoys. SWIMMING STRAIGHT IN FLAT WATER Swimming straight in flat water is largely dependent on balanced stroke technique. The ability to consistently pull evenly throughout all phases of the catch, anchor, and follow through are key factors to being able to swim straight. The ability to breathe on each side (bilateral breathing) while sighting at appropriate i ntervals, will help keep the swimmer on course. Swimmers will sight less often on straight-a-ways and more often approaching turns. Another significant advantage of bilateral breathing is the fact that the swimmer can more easily see the competitors who may be swimming on either side. Because swimmers need to “protect” their position going into the turn buoys and feeding stations, they need to know where the competitors are swimming or if they are being veered off-course. Being comfortable with bilateral breathing is especially important as swimmers may have to choose breathing to a single side to avoid swells, current, chop, or sun.

SWIMMING IN CHOPPY WATER

Swimming in choppy water requires more skill and experience. Moment to moment adjustments based on the water current, wind, “surface waves”, weather conditions and tide patterns are necessary.

Knowing how to take advantage of ocean swells is also an important skill. If the swells are coming up behind the swimmers, it is advantageous to “surf down” the waves or kick harder as the wave is passing over in order to build additional momentum. If the swells are coming at the swimmers, it is advantageous to swim hard “up” the wave and through the crest of the wave in order to minimize the deceleration that the waves are causing. If the swells are hitting the swimmers from either the right or left side, the swimmer need to adjust the course because they may be naturally pushed off the straightest line. Breathing and sighting at the top of the swells will help them navigate better and will allow them to take cleaner breaths. Sighting more often in choppy water is sometimes necessary. The bottom line with swimming in choppy water is that the swimmers have to be flexible and have to be able to adjust stroke technique, breathing, sighting, and kick from moment to moment. Another strategy is provided by Terry L aughlin of Total Immersion. In rough water, most swimmers stroke more aggressively and swing their recovery higher to “get over” swells. Laughlin advocates making one’s stroke calmer

as the water gets rougher. He advocates “piercing” the waves and swell. And, rather than swinging the recovery arm higher, relax it as much as possible so when waves or swell hit, the swimmer isn’t buffeted. Laughlin’s focus is on “ cooperating” with forces not fighting them.

LANDMARKS

During warm-up, swimmers should choose landmarks to study before entering the water. It is advisable to swim to both the first and last turn buoys during warm-up to try and see the most optimal landmarks. The best and obvious choice would be to sight for the buoy if it’s easy to spot. If the swimmer needs a se condary landmark, choose large, stationary objects that are easy to see with quick sighting.

These landmarks can be anything from buildings, to piers, light poles or anchored boats in the distance.

Sometimes being able to sight objects to either side of the swimmer can help keep him or her stay on track as well. Finally, have a few landmarks in mind if the weather conditions that day look questionable. For example, if fog rolls in during the swim and blocks the object the swimmer was using to sight, make sure to have another landmark to use for keeping on course. Again, if the buoy is in sight, always go with that.

SIGHTING

Lift the head out of the water just enough for the eyes to clear the water. The swimmer can

still see the target this way with minimal loss to body position. Learn to sight as infrequently as possible. Depending on various conditions, sighting frequency can range from every 20 strokes to not sighting for several hundred strokes. Learn to sight with as little disruption to balance and rhythm as possible.

TEMPO AND DISTANCE PER CYCLE

Tempo is highly adaptable. Tempo choices are guided by stage in the race, distance of race, and water conditions. Efficiency of stroke needs to be practiced at a range of tempos. Most world class Open Water swimmers swim a tempo ranging 40-49 cycles per minute with tempo generally faster toward the end of the race. Distance per Cycle (DPC) is generally greater in the beginning of an Open Water race

as the swimmers stretch out during the first part 9

OPEN WATER REPORT: RACE STRATEGIES AND PROCEDURES

of the race. The pace starts to pick up at the halfway point and again at In the last quarter of the race. Then it is generally an all-out sprint to the finish.

Distance per cycle tends to be longer than in a pool race. The longer the race, the more likely the DPC will also be long, especially during the first half of the race. However, the intensity of the kick dramatically increases in the last quarter of a race.

CONTACT

If a swimmer gets pulled or bumped by a competitor, it is important to stay calm and resist the immediate and natural feeling to retaliate. Understand that most bumping is done inadvertently and not purposefully. If a competitor continues to bump, pull or hit, the swimmer can either sprint ahead, or swim slightly diagonally toward the other swimmer swimming into the competitor’s “space” in order to protect or re-establish position, or yell loudly in order to draw attention from the referee. If someone is continuously pulling on a swimmer’s ankles, the swimmer can kick very strongly, perform a quick scissors kick, or do a quick 360° spin when their hands grab the ankles.

NEGOTIATING TURN BUOYS

Depending on where the swimmer is in the pack or whether he or she is in the lead breaking clear water, there are different techniques to try. When approaching the buoy, being in the lead or in front of a pack allows the swimmer to be more flexible in the turn technique.

If not surrounded by a lot of swimmers, the swimmer may want to try the corkscrew technique. Take the last freestyle stroke with the arm closest to the buoy, roll onto the back using one backstroke stroke, then back on the front with a freestyle stroke. For example, if the buoy is on the right and the swimmer needs to make a right turn, take the last freestyle stroke with the right arm, the backstroke with the left arm and back onto the front with the right arm to continue swimming seamlessly.

ROUNDING A TURN

If there are a lot of swimmers in the pack , the swimmer may want to try another technique. Using the smallest angle or shortest distance to

sighting

PHOTO FROM WWW.ERICAROSE.COM

PHOTO BY JIM MILLER MD

get around the buoy is important to saving time while turning and to protect position in the race. DRAFTING

Multiple scientific studies have shown the benefits of drafting behind another swimmer. In a study by Bassett et al. in 1991 it was shown that at 95% of a maximal 600-m swim, drafting reduced oxygen consumption by 10%, blood lactate by 31%, and the rate of perceived exertion by 21%. All of these measurements were made in submaximal conditions, which show that drafting allows a swimmer to keep the same pace at a lower energy cost. Chatard et al in 1998 showed that in a drafting position,

triathletes swim 3.2% faster over a 400-m swim than in a non-drafting position. They showed that blood lactate and stroke rate were significantly lower. In this study stroke length was higher in the drafting position. They also showed that performance gains from drafting were related to 400-m time and skinfold thickness. Faster and leaner swimmers showed greater gains in performance. Overall research has shown that drafting while swimming reduces the energy cost of s wimming and allows the swimmer to improve performance.

Proper drafting technique was explored by Chatard et al in 2003. They found that the optimal drafting distance is 0 and 20 inches behind the leader. They showed an 11% reduction in oxygen uptake, 6% reduction in heart rate, 38% reduction in blood lactate, 20% reduction in rating of perceived exertion, and 6% increase in stroke length. Although it was optimal to be as close to the lead swimmer as possible, significant drafting effects were seen at 3 and 5 ft behind the leader. Even at 5 ft from the leader, swimmers can still benefit from a 10% reduction in metabolic cost. Lateral drafting was also shown to be beneficial. Drag was significantly reduced by 7% when the swimmer was 3 ft back from the lead swimmer’s hands and 3 ft to their side. Optimal lateral drafting position was found to be when the drafter’s head was approximately at hip level of the leader.

The above studies demonstrated the benefit of drafting behind a leader in a variety of situations. Any form of drafting has been

In the 10K marathon swimming race, each athlete will be assisted by one coach of their choice. What is it that the coaches do? Why is it so important? And, why is there so much pressure?

The history and responsibilities of Open Water swimming coaches goes back as far as the escort crew of Captain Webb, who was the first person to swim across the English Channel in 1875. Open water swimming coaches not only guide their athletes’ training and nutrition on a daily basis, but also formulate race strategy, serve as their eyes and ears and, very importantly, serve them fluids during the 10K. Open water coaches, like their pool counterparts, typically spend hours walking up and down the deck of a pool training their swimmers and oversee their training in a gym for dryland exercises. Additionally, they spend hours walking up and down shorelines or sitting in kayaks, paddleboards or motorized escort boats following their athletes in Open Water.

During the 2-hour race, the swimmers will pass their coaches, standing on a floating feeding station, four times. The coaches will yell, whistle and cheer for their swimmers on every loop. Each time the swimmers pass the floating feeding station, the coaches will arm themselves with a feeding stick and the athlete’s favorite drink. These drinks include Gatorade, fortified water and as many concoctions as there are swimmers.

During the first 2.5K loop, the swimmers generally do not stop. However, during the next 3 loops, the swimmers and coaches must synchronize their timing perfectly. Any error in timing and the swimmer’s chance of medaling drops considerably.

As the coaches lean, kneel and stretch out as far on the race course as possible, the swimmers swing wide of the straight-line course to cruise pass the feeding station. The swimmers have just one shot at grabbing their cups that are delicately cradled on the coaches’ feeding stick. Observers have equated the frantic swimmers to hungry sharks leaping for one last bloody piece of a sea lion carcass.

Unlike NASCAR drivers who know where their pit crews are located, the swimmers do not know exactly where their coaches are positioned until they see them on the first loop. As the swimmers fight for position coming into their first feeding, they expect the end of their feeding sticks to be slightly above the water’s surface, facing just at their preferred angle, so they can quickly reach up and grab their own cup without breaking their stroke rhythm. A missed stroke means losing valuable ground to their competitors where the difference between gold and bronze is often less than 2 seconds. If the coach-swimmer teamwork is successful, the swimmers reach up for their cup, roll on their backs, gulp their drink and resume swimming - all without losing momentum - within 2 seconds. Meanwhile, the coaches themselves are being pushed and jostled by other coaches trying to reach their own athletes at the optimal position. Like a Tokyo subway train, there is only so much space and too many people. In other words, the coaches have no more than 2 seconds to position their feeding stick at the water’s surface, hold and release the swimmer’s cup at the optimal position, and then retrieve their feeding stick without hitting any competitors. So, unlike the running marathons, where there are frequent water stops along the race course and all kinds of volunteers and cups of water to aid the runner, the swimming marathoners have just three chances to get fluid during

a warm 2-hour race. Despite the coach’s best efforts and years of experience, when a large pack of swimmers comes flying into the feeding station together, the coaches face additional problems. Sometimes, swimmers may grab or inadvertently hit other swimmer’s feeding sticks or spill their competitor’s cups. In these cases, no apologies are made...both swimmers and coaches simply chalk it up to bad luck and poor timing. Second, if a pack 3, 4 or 5 swimmers wide come into the feeding station together, the feeding stick simply cannot reach the swimmer who is positioned

STEVE MUNATONES

TWO SECONDS OF OLYMPIC PRESSURE

ON OPEN WATER COACHES

10

PHOTO BY STEVE MUNATONES

OPEN WATER REPORT: RACE STRATEGIES AND PROCEDURES

PHOTO BY JIM MILLER MD

shown to be beneficial to energy cost and performance. The optimal position is to be directly behind the lead swimmer following as close as possible without hitting his or her feet. If this position is not possible, lateral drafting or drafting further behind will still be advantageous. It is a clear benefit for a swimmer to draft off of a lead swimmer. Drafting in the pool (i.e. swimming 2 to 3 sec apart in circle-swimming) does little to prepare you to draft in an Open Water race. Pool water is clear and the swimmer doesn’t have to navigate nor contend with other swimmers for that drafting position. Also, a good amount of drafting in Open Water will be on s omeone’s hip or knee, rather than on their toes. When drafting, it is easier to keep track of the swimmer being drafted from his or her side when the water isn’t clear. Etiquette dictates that if a swimmer is going to accept a free ride from another swimmer, avoid irritating them by tapping their feet.

If drafting behind a swimmer, be inches behind the feet. If on the hips of the competitor, the swimmer should be swimming close enough to touch the other swimmer on every stroke. If the other swimmer being drafted off of slows down or speeds up, the competitor should too – unless It’s time to pass or lose the drafting effect. It’s usually best to draft and save energy during the beginning and middle stages of the race. Most swimmers do not want to lead during the first half of an Open Water race among elite competition. Allowing others to draft off may cause the lead to have to sight more often to avoid wasting any time going off track. LEADING THE PACK

Leading the pack vs. drafting off of the leaders until the end is dependent on the competition and personal race strategy. In a very rare circumstance a far stronger swimmer than anyone in the pack, may be able to lead the entire way without having to pull someone in a draft. GETTING BOXED-IN

AND PACK SWIMMING

As mentioned previously in Open Water training there must be a focus on anaerobic training and swimming sets at threshold in order to be able to change pace, break away and return to aerobic swimming depending on how the race is unfolding.

furthest from the feeding station. In those cases, the swimmer usually turns up the course and accepts the unfortunate situation.

Third, when a very large group of swimmers heads towards the feeding station, all splashing and swimming very close to one another, the only thing that can be positively identified is a...very large group of swimmers splashing and thrashing close to one another. This is especially true with the men, who often remove their swim caps during races in warm water. Occasionally, as coaches stretch the feeding stick out to the thrashing pod of athletes, they no tice their swimmers are in a different position and swimming away from the feeding station. Occasionally, tempers flare and expletives in numerous languages can be heard; sometimes directed at others, sometimes direct at themselves.

Yet, an unwritten gentlemen’s code of conduct is strictly followed at the feeding stations because every Open Water coach knows that if he or she were to fall in the water and disturb another swimmer, his or her own swimmer would be immediately disqualified.

The coach’s formula is pretty simple. 3 feeds x 2 seconds each x 100% accuracy = potential Olympic gold. In other words, 4 years of standing on pool decks, 4 years of walking along shorelines, 4 years of plotting strategy, 4 years of traveling the world to competitions - and the coach’s best efforts can go up in smoke within 2 seconds.

So the pressure is on - the coaches.

11

PHOTO BY STEVE MUNATONES

OPEN WATER REPORT: RACE STRATEGIES AND PROCEDURES

PHOTO BY JIM MILLER MD

getting boxed-in

Picking positioning at the start and within the pack is very important since the swimmer doesn’t want to find him or herself boxed into the pack and unable to break free. If swimmers find themselves in the middle of a pack and want to make their way to the front, side or back of the pack, they must be somewhat aggressive. Making their way to the outside will take the least amount of energy while still drafting and holding position without losing too much ground.

It is better to have only one swimmer on the side. That is, if a swimmer is in the middle of two swimmers with one on the left and one on the right side, there will be a lot

of needless energy exerted because the swimmer will be hit and jostled on both sides by competitors.

If acompetitor is frequently hitting a swimmer’s feet, ankles or calves, the swimmer can kick extremely hard without being malicious in order to inform the competitor that “space” should not be invaded. By protecting his or her space, the swimmer will be able to conserve energy for the important last part of the race. WORKING WITH A TEAMMATE

Working with a teammate can involve starting side-by-side at the start where there is significant bumping and jostling among all the swimmers. Having an ally on at least one side can minimize the jostling. Working with a teammate can also involve taking turns drafting off one another. Prior to the race, swimmers and their coaches can discuss drafting over a certain distance so both swimmers can take advantage of the other (a la cycling). Because it is difficult to communicate during a race, where things generally do not go exactly to plan, the swimmers should be very clear and fair about when to take and relinquish the lead (e.g., every 1K or every other turn buoy). The swimmer in the rear should be responsible for informing the lead swimmer when he or she will take over the lead. The rear swimmer can tap the lead swimmer’s feet or calves so the lead swimmer can know to slow down or move to the side.

MAKING A BREAK

As mentioned above, anaerobic training is really important because of how quickly the conditions and pace of the race can change from moment to moment. Being able to break away, change up the pace, speed up or slow down is highly dependent on this anaerobic training. A swimmer can make a break in many ways. Usually a good time to break is during the second half of the race when the pace tends to pick up.

The world’s best Open Water swimmers have great techniques and strategies going into and around the turn buoys. If a swimmer sprints in and out of a turn buoy, he can put a lot of a distance you can place between himself and his competitors. In flat water, it is nearly impossible for swimmers of equal ability to pass one another. However, great turns in, around and out of the buoys can dramatically change the relative positions of the swimmers. Care must be taken to make a move early enough to get to the ideal position. It is vital to stay within striking distance of the leader. A swimmer must know exactly when the leader or leaders put on a spurt of speed to break from the lead pack. It is extremely difficult to catch up even 5 meters in the Open Water among an elite field, especially in the last 1K.

FINISH

At the finish, the swimmer should swim the straightest line between the final turn buoy and the finish. Just like in a pool race, it’s important to finish hard, keep the tempo up and to utilize the kick. The last 100 meters will be an all-out sprint with the elite swimmers doing all they can to win. Slapping and bumping arms, elbows, legs and bodies, jostling positions, and purposefully or unintentionally veering a competitor off-course are the norm in elite Open Water competitions. Swimmers cannot and should not shy from this physical

interaction with their competitors and must realize that they will be swimming in extraordinarily close proximity to their competitors.

SWIMMERS SLAP THE TOUCHPAD In most national or international championship Open Water races, the end time is determined by touching a pad at the end of the race. The touch pad is elevated above the water’s edge, so the swimmer has to reach up and out to touch the pad. Touching the pad is best done with the palm of the hand. The swimmers must be sure to “slap” the touch pad hard, especially in a close race. Even if a swimmer’s head or body has passed the plane of the finish line, the swimmer is not officially finished until he has properly hit the touch pad with the hands. The touch pads will have up to 6 black crosses and be up to 20 feet across. It is acceptable to touch anywhere on the touch pad.

FEEDING

Making use of the designated feed stations during the 10K race is important, but knowing how to feed efficiently and correctly is critical to a successful finish. To make the most of a feed station visit, remember these important rules and tips:

• • • Swimmers may not hang on to the feed station, feed pole, or a person in the feed station, so a method of feeding must be determined.

• • • Use a cup when the swimmer can get close enough to the feeder to be handed a cup of feed.

• • • When the swimmer can’t get close enough to the feeder, take the feed from the feeding stick or pole. It will have a basket or cup holder on the end (something that the cup can be securely placed in).

• • • Stay horizontal.

• • • Work out a plan with the feeder so that the swimmer will be able to identify him/her quickly upon approaching the feed station. GRASP THE CUP FROM ON TOP

• • • If the swimmer is drinking out of a cup that is placed at the end of a feeding

stick provided by the feeder, the swimmer should grab the cup from the top as he rolls over on his back. This will help prevent the contents from spilling. The swimmer should keep kicking as

he rolls over on his back and drink the contents in the cup. This entire pro cess should take 3 seconds or less! Expect significant confusion and jostling at the feeding stations during a close race.

• • • If a gel pack is used, the gel pack should be opened slightly BEFORE the race and tucked inside the swim suit. A slight tear will enable the swimmer to quickly open the gel pack during the race and minimize time loss. A swimmer should place 2 gel packs in the swim suit, just in case one of the gel packs is lost during the race. Swimmers put the gel packs between their skin and their swim suits near the shoulders, hips or waist. It is not necessary to “chew” the contents of a gel pack. The swimmer can stick the entire gel pack in the mouth, close the mouth around the opening and squeeze the entire gel content into the mouth.

PRACTICE FEEDING

Feeding during long pool practices helps the body learn to accept food and fluids on race day AND is critical to maximizing the quality of those long workouts themselves and enhancing the training effect in preparation for a race that will require feeding. We tend to focus so much on the importance of race day feeding, that we overlook the HUGE important effects of feeding during daily workouts.

TRAIN TO MISS A FEEDING

Athletes should anticipate variations in the number of feeding opportunities for races. They may not always be the same. They may miss one. Preparing them for this psychologically will help prevent them from relying too much on a feed. If they miss one, it will not be devastating provided they have practiced good feeding strategies to support their training up to this point.

FEEDING DURING THE RACE

Performance gained by feeding during an event longer than 90 minutes is probably greater than time saved by not feeding during the same event. However, the optimal feeding strategy for any Open Water race is highly individual and involves the application of sound physiology and nutrition principles combined with r ace-specific characteristics, such as distance, location, venue/water type, feeding opportunity and swimmer tolerances/ preferences. Therefore, the decision to feed or not to feed during a 10K Open Water race may vary from one race to the next. The feeding recommendations provided in this d ocument are specific to a fresh-water 10K course with feeding stations set up at the 5K mark (approximately :55 into the race) and the 7.5K mark (approximately 1:25 in to the race). Ideally, a swimmer would hydrate every 15 minutes and refuel every 45 minutes. However, given the feeding station layout on this course, 12

OPEN WATER REPORT: RACE STRATEGIES AND PROCEDURES

swimmers are directed

toward the finish

PHOTO BY STEVE MUNATONES

grasp the cup from the top

PHOTO BY JIM MILLER MD

swimmers slap the touchpad

a choice must be made between fuel and fluid at the first feeding station. In this case, the need for fuel outweighs the need for fluid at the 5K mark. Swimmers have more to gain by taking in calories at this point than by taking in fluid. Carbohydrate that will digest and absorb readily is key. All other products, such as bars, jelly beans and gummies require chewing which is too time-consuming and labor-intensive for the 10K swim. Therefore, the most optimal fuel source for this 10K event is carbohydrate in liquid form. Liquids are easy to ingest and digest during this type of event, and neither protein nor fat will enhance this race performance. While carbohydrate in liquid form is optimal for the 5K feeding station, a single gel pack can offer a decent alternative since it also offers similar amounts of carbohydrate, sodium and potassium. However, gels are most effective (and tolerable) when followed by 4-6 oz of water, so the gel pack should be mixed with 4-6oz of water for the feed. Another alternative is to ingest the gel at the 45iminute mark, followed by the 4 oz of water at the 55-minute feeding station. However, this does mean the athlete takes time for two feedings, a risky move in the 10K event when the pack with probably be tight during the first hour and jockeying for position will be important. Even with the first choice established, the swimmer should carry at least one gel pack in his/her suit for back-up in the event that the first feeding station is missed. Fuel is important at this stage of the race, and waiting until the second feed station is not a good idea. Even without the 4-6oz water chase, the gel will be effective in providing fuel that the swimmer needs at this stage of the race.

Given the set-up of this particular 10K course,

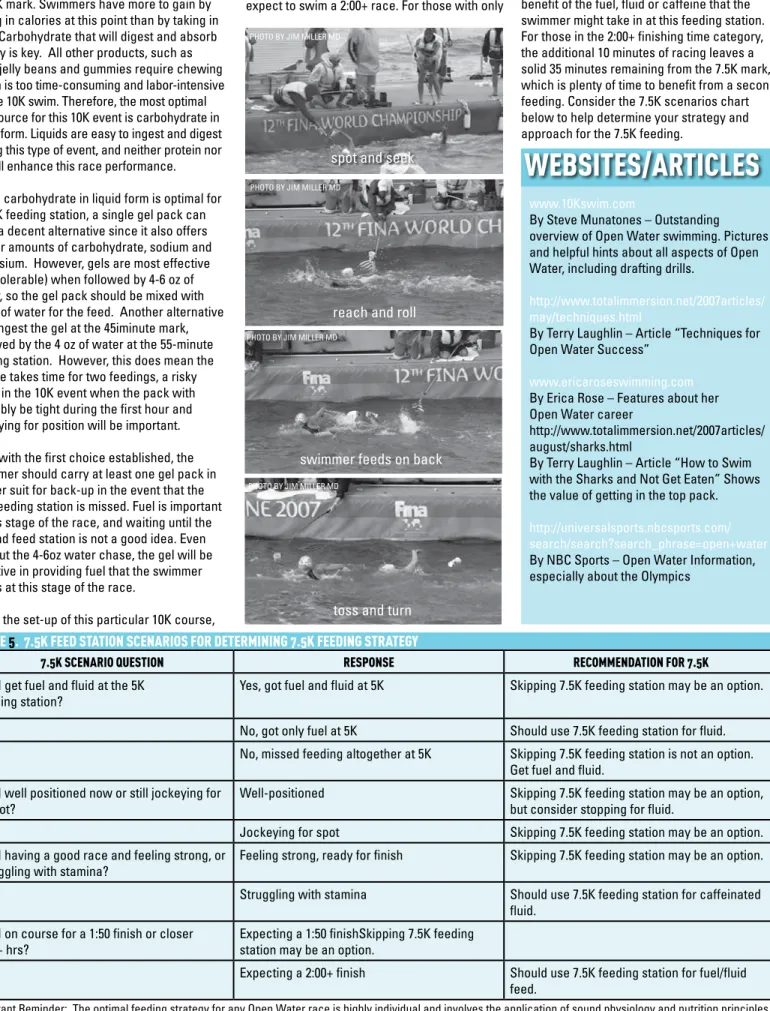

7.5K SCENARIO QUESTION RESPONSE RECOMMENDATION FOR 7.5K

Did I get fuel and fluid at the 5K feeding station?

Yes, got fuel and fluid at 5K Skipping 7.5K feeding station may be an option.

No, got only fuel at 5K Should use 7.5K feeding station for fluid. No, missed feeding altogether at 5K Skipping 7.5K feeding station is not an option.

Get fuel and fluid. Am I well positioned now or still jockeying for

a spot?

Well-positioned Skipping 7.5K feeding station may be an option,

but consider stopping for fluid.

Jockeying for spot Skipping 7.5K feeding station may be an option. Am I having a good race and feeling strong, or

struggling with stamina?

Feeling strong, ready for finish Skipping 7.5K feeding station may be an option.

Struggling with stamina Should use 7.5K feeding station for caffeinated fluid.

Am I on course for a 1:50 finish or closer to 2+ hrs?

Expecting a 1:50 finishSkipping 7.5K feeding station may be an option.

Expecting a 2:00+ finish Should use 7.5K feeding station for fuel/fluid feed.

TABLE

5

. 7.5K FEED STATION SCENARIOS FOR DETERMINING 7.5K FEEDING STRATEGY

Important Reminder: The optimal feeding strategy for any Open Water race is highly individual and involves the application of sound physiology and nutrition principles combined with race-specific characteristics, such as distance, location, venue/water type, feeding opportunity and swimmer tolerances/preferences. These recommendations are specific to a fresh-water 10K course with feeding stations set up at the 5K and 7.5K marks.

13

OPEN WATER REPORT: RACE STRATEGIES AND PROCEDURES

PHOTO BY JIM MILLER MD

spot and seek

PHOTO BY JIM MILLER MD

reach and roll

PHOTO BY JIM MILLER MD

swimmer feeds on back

PHOTO BY JIM MILLER MD

toss and turn

WEBSITES/ARTICLES

www.10Kswim.com

By Steve Munatones – Outstanding overview of Open Water swimming. Pictures and helpful hints about all aspects of Open Water, including drafting drills.

http://www.totalimmersion.net/2007articles/ may/techniques.html

By Terry Laughlin – Article “Techniques for Open Water Success”

www.ericaroseswimming.com By Erica Rose – Features about her Open Water career

http://www.totalimmersion.net/2007articles/ august/sharks.html

By Terry Laughlin – Article “How to Swim with the Sharks and Not Get Eaten” Shows the value of getting in the top pack. http://universalsports.nbcsports.com/ search/search?search_phrase=open+water By NBC Sports – Open Water Information, especially about the Olympics

the 7.5K feeding station can be considered optional for most of those who expect to finish the race in 1:50 or faster, but not for those who expect to swim a 2:00+ race. For those with only

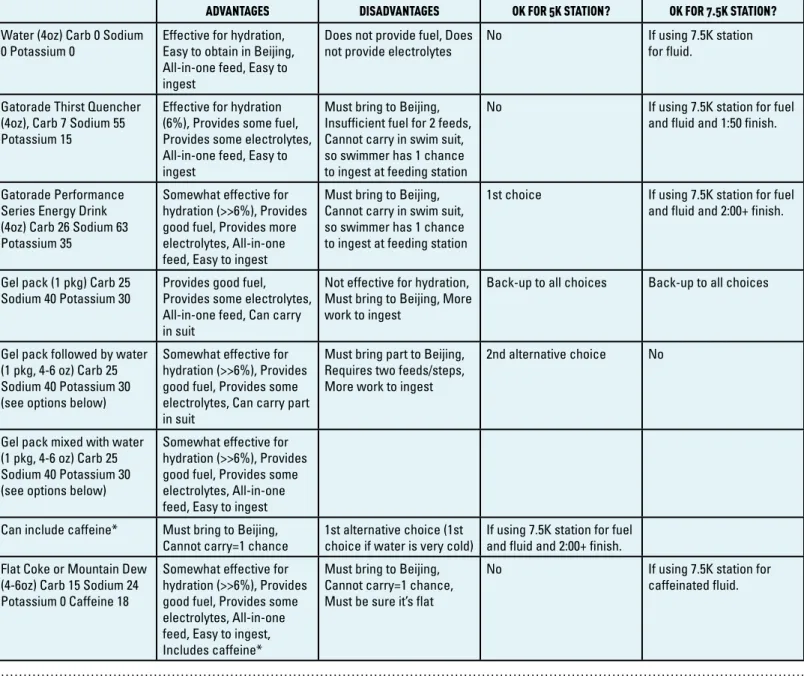

ADVANTAGES DISADVANTAGES OK FOR 5K STATION? OK FOR 7.5K STATION?

Water (4oz) Carb 0 Sodium 0 Potassium 0

Effective for hydration, Easy to obtain in Beijing, All-in-one feed, Easy to ingest

Does not provide fuel, Does not provide electrolytes

No If using 7.5K station

for fluid.

Gatorade Thirst Quencher (4oz), Carb 7 Sodium 55 Potassium 15

Effective for hydration (6%), Provides some fuel, Provides some electrolytes, All-in-one feed, Easy to ingest

Must bring to Beijing, Insufficient fuel for 2 feeds, Cannot carry in swim suit, so swimmer has 1 chance to ingest at feeding station

No If using 7.5K station for fuel

and fluid and 1:50 finish.

Gatorade Performance Series Energy Drink (4oz) Carb 26 Sodium 63 Potassium 35

Somewhat effective for hydration (>>6%), Provides good fuel, Provides more electrolytes, All-in-one feed, Easy to ingest

Must bring to Beijing, Cannot carry in swim suit, so swimmer has 1 chance to ingest at feeding station

1st choice If using 7.5K station for fuel and fluid and 2:00+ finish.

Gel pack (1 pkg) Carb 25

Sodium 40 Potassium 30 Provides good fuel, Provides some electrolytes, All-in-one feed, Can carry in suit

Not effective for hydration, Must bring to Beijing, More work to ingest

Back-up to all choices Back-up to all choices

Gel pack followed by water (1 pkg, 4-6 oz) Carb 25 Sodium 40 Potassium 30 (see options below)

Somewhat effective for hydration (>>6%), Provides good fuel, Provides some electrolytes, Can carry part in suit

Must bring part to Beijing, Requires two feeds/steps, More work to ingest

2nd alternative choice No

Gel pack mixed with water (1 pkg, 4-6 oz) Carb 25 Sodium 40 Potassium 30 (see options below)

Somewhat effective for hydration (>>6%), Provides good fuel, Provides some electrolytes, All-in-one feed, Easy to ingest Can include caffeine* Must bring to Beijing,

Cannot carry=1 chance

1st alternative choice (1st choice if water is very cold)

If using 7.5K station for fuel and fluid and 2:00+ finish. Flat Coke or Mountain Dew

(4-6oz) Carb 15 Sodium 24 Potassium 0 Caffeine 18

Somewhat effective for hydration (>>6%), Provides good fuel, Provides some electrolytes, All-in-one feed, Easy to ingest, Includes caffeine*

Must bring to Beijing, Cannot carry=1 chance, Must be sure it’s flat

No If using 7.5K station for

caffeinated fluid.

TABLE

6

. OPTIONS FOR FEEDING AT 5K AND 7.5K DURING 2008 OLYMPIC OPEN WATER EVENT

14

OPEN WATER REPORT: OLYMPIC OPEN WATER RACING HISTORY

On August 20-21, 2008, 25 men and 25 women will compete in the first Olympic 10K Open Water swim race. But, the history of Open Water swimming at the Olympics goes back a long, long way.

At the Athens Olympics, on April 11th 1896, four swim races were held in the Bay of Zea in the Aegean Sea: a 100-meter race, a 500-meter race, a 1200-meter race and a special race only for Greek sailors. Reportedly, 20,000 spectators were said to have watched the four events off the Piraeus coast.

According to Allen Guttmann in his book The Olympics: A History of the Modern Games, Alfred Hajós of Hungary, the gold medalist in the 100 and 1200, described his races as, “I won ahead of the others with a big lead, but

STEVE MUNATONES

my greatest struggle was against the towering twelve-foot waves and the terribly cold water.” In April, the ocean water was 50°F (or 10C°). Due to the cold water, Hajós covered his body with a thick half-inch layer of grease. The swimmers were taken to the starting point in a boat and told to head towards shore. Upon winning the 1200, Hajós said, “My will to live completely overcame my desire to win.” At the 1900 Paris Olympics, seven swimming events (men only) were held in the Seine River, including the 200-meter freestyle, 200-meter backstroke, 400-meter freestyle, 4000-meter race, 60-meter underwater, 200-meter team and 200-meter obstacle (where the athletes climbed a pole and then swim over and under a row of boats). On the positive side, the swimmers

15

OPEN WATER REPORT: NUTRITION FOR OPEN WATER

TABLE

7

. GEL PACK REPORT AND SUMMARY

CAFFEINE-FREE WITH CAFFEINE* (SEE * NOTES BELOW)

CAFFEINE SOURCE** (SEE ** NOTES BELOW)

CarbBoom All other flavors Choc Cherry (50mg), Vanilla Orange

(50mg)

Kola nut extract

Clif Shot Mango, Vanilla, Razz, Chocolate,

Orange Cream

Mocha (50mg), Strawb/Cream (25mg), Cola (50mg)

Green tea extract

GU Banana Blitz All other flavors (20mg) GU Herbal Blend (chamomile, cola

nut, ginger)

PowerGel All other flavors Double Latte (50mg), Chocolate

(25mg), Green Apple (25mg), Strawb/Banana (25mg)

PowerBar Booster Blend (caffeine, ginseng, kola nut extract)

*The Caffeine Factor

There are two mechanisms whereby caffeine can enhance endurance performance. The first involves an increased use of fat as a fuel source, which spares glycogen, and the second involves

its stimulant effect. For the first mechanism to take effect the caffeine must be ingested 3-4 hours prior to the performance AND there must be a deficit in energy stores (i.e. glycogen stores not

topped off). In other words, the energy-related performance effects of caffeine are not significant in athletes whose fuel stores are good. So if a swimmer has been fueling and re-fueling well on a daily basis during training, there is little advantage from an energy standpoint to taking caffeine before or during a 10K race. Assuming the athlete is well fed on the day of the race, there is little advantage (if any) to including caffeine in the first feeding.

However, the second mechanism (the stimulant effect), is a “during exercise” effect that may or may not enhance performance when taken during the final leg of a race. The effect depends on the athlete’s response and tolerance to caffeine at that point in time. If the swimmer is having a good race, took his/her first feeding on time and is in a good position, chances are that the adrenalin rush of the final 30 minutes of the race is enough, and adding caffeine to the feed will offer no advantage. However, if the swimmer is struggling with stamina and/or missed the first feeding, a caffeinated feed may enhance that final leg of the race. This will be a game day decision and agreement between the athlete and his/her feeder.

**Caffeine Sources

Even though these four brands of gels carry a Nutrition Facts label on their packaging, athletes must be aware of and sensitive to the specific ingredients of each gel. While the caffeine-free gels by Clif, PowerBar and CarbBoom contain the most basic of ingredients, all of the GU gels and all of the caffeinated gels include ingredients that if sold separately would be classed by the FDA as dietary supplements. Be particularly cautious with proprietary blends, such as the GU Herbal Blend and the PowerBar Booster Blend.

Athletes should check with the USADA Drug Reference Line (800-233-0393) or Drug Reference Online (www.usantidoping.org/dro) before utilizing any item marked ‘Supplement’.

NUTRITION FOR OPEN WATER

RECOVERY

There should be a heavy emphasis on recovery from daily training bouts. Eating and rehydrating immediately after every workout to minimize muscle tissue breakdown and to keep the body in a more anabolic (protein building) and glycogen-repleting state after exercise is crucial. Also, on Open Water training days practice feedings quickly, at the same rate feeding would occur in a race (less than 3 seconds). Train with the feeding supplies that will be used in the big swim, and at the rate of speed the feeding will occur in a race. Experiment early on with the actual foods and time intervals. Determine what works and what doesn’t work. A swimmer may react differently to certain foods in salt water versus fresh or chlorine– it’s important to test it! Be sure the drink chosen is to the swimmer’s liking. If the swimmer doesn’t like the taste of the feed, chances are he or she won’t want to feed. Experiment with different products to determine preferences, what works best and what is easily digestible.

USE GATORADE DURING TRAINING

It is true that Gatorade contains sugar, salt, flavoring and dyes, but this sugar and salt are part of its benefits in terms of maintaining blood sugar levels and electrolytes during workouts lasting longer than 90 minutes. Gatorade is also an excellent source of fluid, with a concentration that allows the body to absorb the fluid without much gastrointestinal distress.

Stronger drinks (drinks with more fuel) tend to cause more problems than they solve when taken frequently during training or racing. Most (not all) athletes prefer the taste of flavored drinks to water and will drink them more readily that water. Gatorade is not recommended outside of workout, unless it is the only food available for the immediate post-workout snack. DO NOT DEPEND ON DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS Experts agree that athletes achieve better results by paying attention to food and drink intake than by following any other courses of action such as taking supplements or ergogenic aids. Athletes should check with the USADA Drug Reference Line (800-233-0393) or Drug Reference Online (www.usantidoping.org/dro) before utilizing any item marked ‘Supplement’. MAXIMIZE THE TAPER

Characterized by decreasing volume and relatively high intensity, the taper period is a golden opportunity for endurance swimmers to load and top off fuel stores. To maximize this effect, gradually increase carbohydrate and fluid intake for a one week period leading up to race day. Avoid loading strategies that involve a glycogen depletion phase.

DISCUSS YOUR STRATEGY

Coaches and managers must discuss race feeding strategy and preferences with athletes. Be sure everyone is on the same page regarding not only what food will be given at

the feeding stations, but how that food will be delivered, how the swimmer will recognize his/ her feeder, where the feeder will be located, how the swimmer should approach the feeding station, how long he/she has to feed, and any other details that are relevant to making the process both efficient and effective. BRING YOUR OWN PRODUCTS

Plan ahead to bring Gatorade products and gel packs, especially if travelling and competing in a foreign country.