--.

:~'~

'FUNDAÇÃO

....

--

-GETUI.IO VARQAS

CIRClJLAR N°88

AsBtUlto: S~minários P~squisa &onômicaIl (2" parte)

Coordenadores: PrOL Fernando de H. Barbosa

e Prof. Gregório Lowe Stukart

Convidamos V.Sa. para participar do Seminário de Pesquisa Econômica LI (2~ parte)

a

- realizar-se na próxima 5~ feira:

-

-DATA: 11111/93

...

HORÁRIO: 1~:30h-

LOCAL:--

TEMA:-

---

-- .Inpr

,.

--

-Auditório EugêDio Gudht

"GERMAN Ur'A.GE AND PRICE /NFLATION A.F7'ER UNIFICA.T/ON" - Pro! GWq7pe TuJlio (Uni",usiJ] ofCagliari)

Rio de Janeiro, 04 de nov~ de 1993.

k(JhlÜdill4l Barbola

~

-' Prol. FCoordenadores de Seminários de PesquisasIEPGE

--

-::mI,IO;",Sti", \( . ~

c (

! . /.,

-

---

--

--

-

--

-.

.,

--

--

--

--

GERMAN WAGE ANO PRICE INFLATION AFTER UNIFICATION

--

8Y

---

GIUSEPPE TULLlO, ALFRED STEINHERR AND HER8ERT 8USCHER*

-

--

-.... * University of Cagliari, European lnvestment Bank and Freie Universitãt - Berlin, resp.

-

-Opinions expressed in this paper are strictly personal

-....

--

-

--

_.

-....

--

---

-L'\"TRODUCTI01\

This paper focuses on the consequences of Gennan econOmIC and monetary UnIon (GEMU) for price and wage inflation in Gennany and the related issue of the DM as the anchor of the EMS. :

In Section 1 we analyse economic developments in East and V/est Germany in the period

1990-92 with the aim of assessing both the consequences for wage and price inflation and the prospects for economic recovery in the Eastern territories in the next decade or

50. Particular anention is devoted to the financiai effon in terms of net transfers which

the federal goverrunent has put in p1ace and to the official and private investment effon in Ea.st Germany. as these variables are key for the assessment of future fmancial performance in Germany.

Comparison of the rapid West German recovery after 1948 with the situation in East

Germany. leads us to an overall guarded but positive assessment of the growth prospects

of the ex-GDR despite the two main policy problems that plague and will continue to

plague for some time the East Gennan economy : the excessive rise in real wage costs.

causing sharply rising transfers. and the legalistic approach to the settlement of propeny rights.

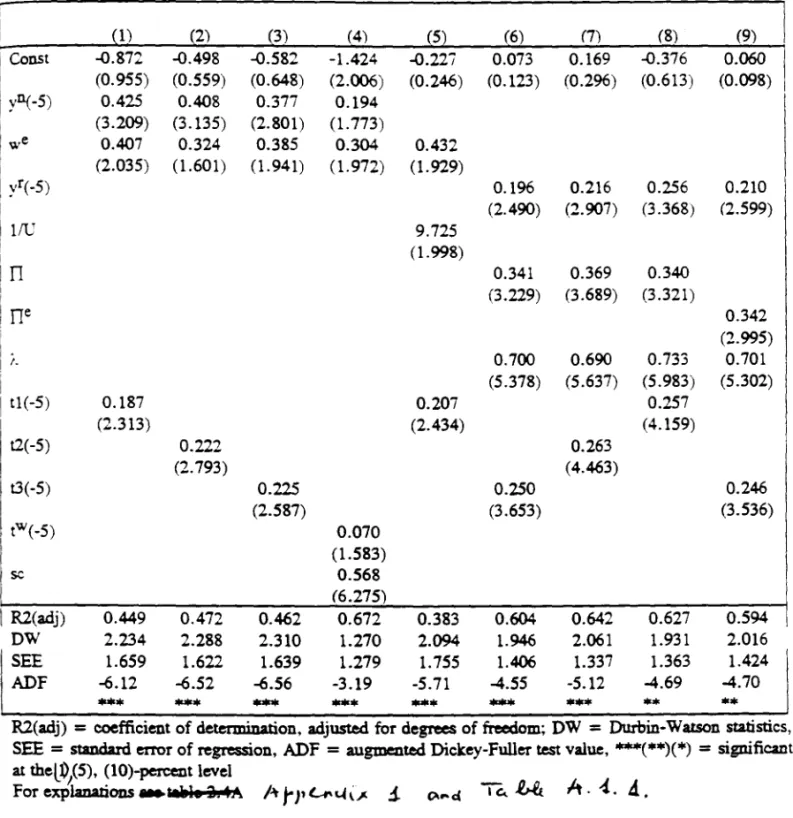

Section 2 analyses wage and price developments in West Germany after reunification.

We present estimates of wage equations for the period 1960-1989 in whi.ch forward shifting of income taxes and social security connibutions is of imponance. Our main hypothesis is that the large wage increa.ses in 1990-91 in the West of Germany were caused by high capacity utilisation, w hile in 1991 and 1992 the 7.5 per cent extraordinary income tax increa.se (SolidaritãtszUschlag) from mid 1991 to mid 1992. the increase in social security connibutions and excise taxes and the announced increase in the VAT from 14 to 15 per cent, effective January 1st 1993 played a crucial role. The estimated equation is used to simulate out-of sample nominal wage increases in 1991-92.

--

-

---

--

-

--

.

-

-

--lncreases in excise taXes and the taX on energy have in rurn contributed directly to price inflation and indirectly to second round wage increases.

Section 3 asks whether GEMU and the acceleration of wage and price inflation lowered the credibility of Gennan monetary authorities and as a result lessened the DM' s role as

anchor of the EMS. The observed rise in Gennan interest rates after unification

can

bedue to (i) higher demand for funds; (ü) an increased risk premium; (li) or expectations

of higher long-term inflation rates.

The first argument is weak. as in the absence of capital controis and with sound initial conditions the increase in demand for funds shouid spill over into world capital markets. In relation to world markets the increased need of capital for German unification appears toO small to produce sizeabie changes in interest rates2. The second and third effects are of potential imponance and would imply that the then existing EMS bands were at stake and possibly the Bundesbank' s credibility in delivering price stability.

For a àirect test of EMS credibility, we use the approach pioneered by S vensson (1991). Exchange rate flucruation margins impose a bound on the domestic currency rerurn on a foreign currency investment as long as the central rate is expected to remain unchanged.

This bound is a function of the time hotizon and decreases for longer terroso If the

domestic rerurn were outside the bound of the foreign rerurn convened into domestic

currency then the ERM: central rates of the DM cannot be credible over the hotizon

concerned. Vv' e use the French franc as the reference foreign currency.

Finally, in Section 4 we look at the consequences of GEMU for the cohesion of the ERM of the EMS. Clearlv unificanon has fostered conven?:ence bv .,

-

., raisin~-

Germanv's ~ inflation rate and interest rate dose to and even above EMS averages. The unprecedented swing in the German current account (representing about 6 percentage points of GDP from 1989 to 1992) has elirninated one of the major "problems" of the EMS. the hugeGerman current account surplus. lt has also led to higher growth of GDP in 1990 and

Collins and Rodrict (1991) estunate savmg:s and invesunent tuDctlons of deveiooed counmes and amve at the conciuslon that. say. an annual a-ansfer of lJSD 55 bn to East Germany would r&lse world tnterest rate by 176 OaslS pomts. This seems to be unreasonabiy higil.

-

-1991 in neighbouring countries. although this positive effect has been reduced by higher

_ interest rates within the system which contributed to the down-rurn in 1992 and 1993.

-

--Countries with weak currem accoum, positions have thus gained more time to adjust. In

this respect. events in Gennany have probably proIonged the stability of nominal

exchange rates within the system. This section presents estimates of impon equations for

West Gennany from 1971 to 1990. separateIy for total impons. consumption and

invesonent goods. We evaluate by means of simulations the effect of reunification on impons of West Germany in 1991-92 and conclude that vinualiy ali the rurn-round in the

- German currem accoum is due to the pent-up demand for western goods by East

-

Germans. and that no real appreciation was necessary to engineer that rurn-around of the--

currem accoum.--

1. An overview of the ÍIrSt vears of unification-

- In the GEMlJ. industrial production and GDP collapsed m the East. as the Eastern-

---

--

..

--

-indusrry was suddenly exposed to Western competition afier years of isolation. Part of

the coliapse occurred in the flISt half of 1990 in anticipation of the opening up of trade

and the ensuing freedom of Eastern citizens to choose between western and eastern

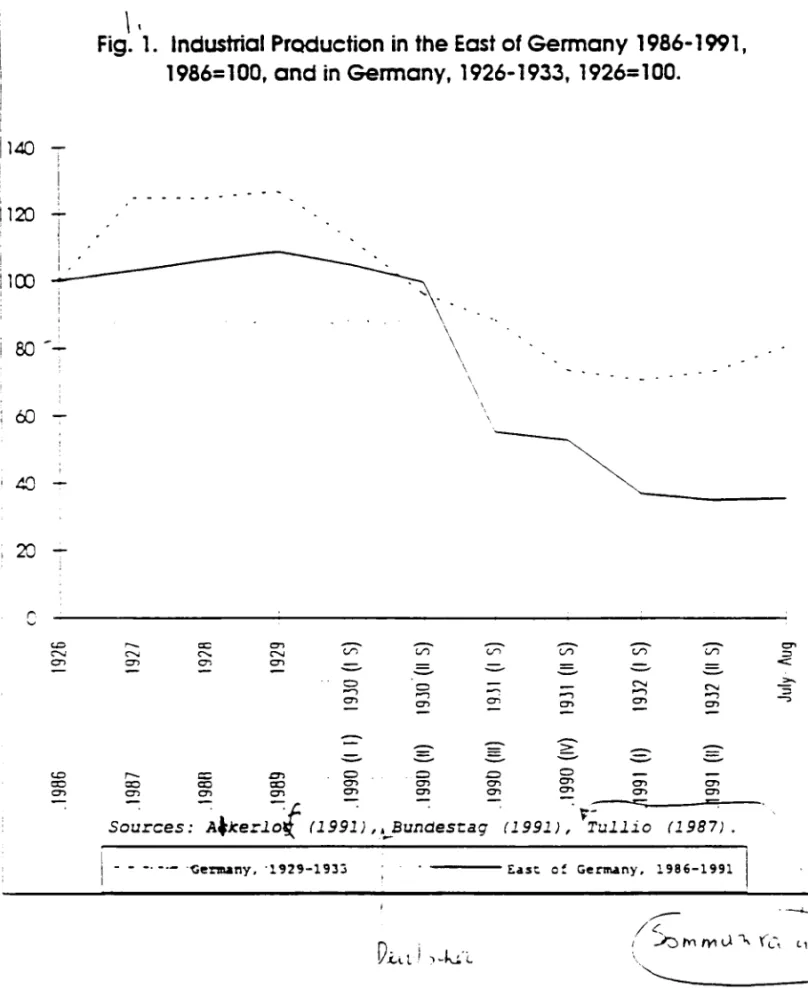

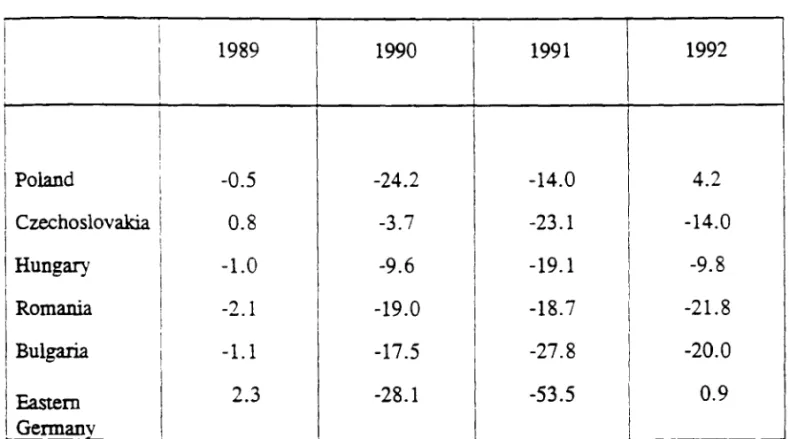

goods. The coliapse was unprecedented both by comparison with deve10pmems in Central and Eastern Europe in the period 1989-92 and with the fali in German industrial production during the great depression of the 19305. Industrial production in the East of Gennany feli by 28 per cent in 1990 and a further 54 per cent in 1991 (Tab1e 1.1).

By comparison the fali of industrial production in Poland. Czechos10vakia and Hungary during the same years was "moderate" despite the fact that these countries suffered even

more than East Germany from the 10ss of expon markets in the former Soviet U nion3 . In

Rumania and Bulgaria industrial production feli in the three years from 1989 to 1991 by

approximately a cumulated 40 per cem. but comraction continued in 1992 whilst it

The fali in East German eXDOrtS to the FS'U "'as .nenuateci .nd del.yeci by export tlnanClog guarantees orovideci Tor some time by lhe German governmen:.

--

--

-stoppeà in Eastern Gennany. Thus. more than anywhere else the collapse in Eastern

Germany was immediate and deep.

For comparison, it is also interesting to note that fram its peak in 1927 to its through in the frrst semester of 1932 industrial producúon feli in the whole of Gennany by 43 per cento substantially less than in the East of Germany. Funhermore the drop occurred then over a period of four and a half years rather than two years (Fig. 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 abollt here

Thus the post-unification depression III East Germany is probably unprecedented in

peace-time history both as far as the size and the speed of the coliapse of producúon is

concerned.

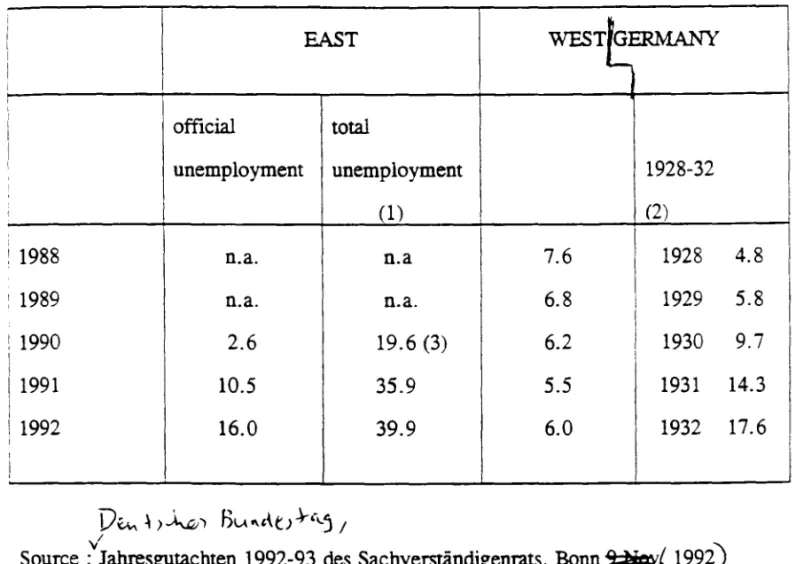

In the course of 1991 the index of industrial production reached its through which was

maintained during 1992. Yet. unemployment cominued to rise in 1992. Official

unemploymem rase fram 10.5 per cem in 1991 to 16 per cent in 1992. These figures

exclude however a large number of part-time workers, workers temporarily subsidised under government programs (Arbeitsbeschaffungsmassnabmen ar ABM). retraining

- schemes. and early reÚIements. Once these workers are taken into accoum. the rate of

-

--

.

-unemploymem rase from 19.6 per cem of the labour force in the last quarter of 1990 to

about 39 per cem in 1992 (Table 1.2). Thus while the official rate of unemployment may

peak at about the same levels as during the Great Depression ~see Table 1.2). the true

unemploymem rate will peak, at best. at about two and a half times the official leveI.

ünemployment would have been still higher in the absence of a large net emigraúon to

West Germany (110 000 in 1991 and 50 000 in 1992) and a large number of early retirements (530 000 in 1991 and 810 000 in 1992), emphasizing the unprecedented

narure of the East German 1989-92 depression4.

Comparing the producúon and employmem cutbacks in the ex-GDR after unificaúon

with those of any other historic period is. of course, to be qualified. The Great

..:. Toe nUrnDer of wor~ers re.51clUlg In East Germany DUt wor~ng in West Germany (·Pendler") rose trem 80.000 in 1990 to :90.000 in 1991 and 375.000 in 199:.

-

---

---

-

-..

--

--

--

-

-

--

-1140 I 1120

-I

I i I , i ; 1100 , 80 --'40 ,20 r v \ IFig. 1. Industrial PrQduction in the East of Germany 1986-1991, 1986= 1 00, and in Germany, 1926-1933, 1926= 1 00.

" - ex: O"l Vi'

""

<"-""

O'> c:n O"l-

o ...-, O"l -r-- c:: r:t"l o::o cx:l ::o O"l

O"l c:n O'> O"l

-

-Vi'-

o .-, O"l--

o O'> O'> -\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ ,'----

~---Vi' Vi' Vi' =

V"l =o <::

-

-

-

=-""

""

>.. ...-, ,...., ...-, "5 c:n c:n O"l O'> ~ ~-

--

=

o-

-c:n O"l O"l c:n O'> c:n O"l c:n-

. - . : : : ; =Sources:

~.Jcerlot

(1991) ,,~Bundes~ag (1991), t-Tullio (1987).1- - -,-,-

'~enuny. '1929-1933 - - - - Easc of Germany. 1986-1991/~ -~

I ./::) M m lJ "(L'"\ tl-.l

-"---

--

--

-

---

--

-

---

--

-.

---

-

--Depression was mainly caused by a collapse of demand whereas the problem in the

ex-GDR is one of fundamental strucrural change. In this respect comparison with

reconstIUction after World War TI is closer to the mark. but also not directly comparable

(see below). After W orld War TI the economy had 10 rebuild its capital stock but did not

need 10 catch-up to a 20-30 year technological advance. and did not need to adapt 10 an

entire1y new instirutional and motivational set-up. On the positive side. Marshall aid for

West Germanv arnounted to much less than current West Gerrnan transfers 10 East

Gerrnany.

Because the problem in East Germany is one of complete restrucruring of the economy.

the oruy policy choice is about timing. It can be done fast or s10w 1y. The fast approach ("big-bang") is like1y to cause more unemployment but will generate more rapid.ly a

reforrned strucrure. A. complete welfare analysis will have to compare the arnount of

resources (and other welfare costs such as the disutility from being unemployed) lost due

to unemployment and to sustained inefficiencies over time. Although such a complete

analysis is theoretically perfectly feasible. there is little hope for a meaningful empírical

application. It remains therefore an open question whether a "big-bang" approach is

costly or beneficial in net welfare terrns. At any rate. Gerrnany had no choice. Once GEMU was created. competitive conditions changed over night for the ex-GDR and a big-bang approach became unavoidable.

In Germany several parties pleaded strongly for a big-bang solution. West Germany was

ready to back up this approach with its financiaI resources and to put the economy of the ex-GDR on the successful marked-based West Gerrnan model. Whilst other sovereign reforming nations had to design their new instirutions. appropriate laws. a financial system. a currency - ali these became available to the ex-GDR over night.

Of course. some of the instirutional fearures of the FRG are characteristics for a marure. rich western economy and totally inappropriate for the developing East. It is very

--

-

-

---.

--

.--

-unlikely that some Asian countries would have become tigers if they had adopted

German labour laws and regulations and were operated by the Gennan bureaucracy.

In one respect. however, the approach already has paid off. In most former socialist

countries restructuring and price liberalisation has resulted in high inflationary bouts due to a lack of monetary control. This has not happened in Gennany.

The unemployment rate in West Gennany moved in the opposite direction to East

Germany both in 1989 and 1991. despite the large increase in the West Gennan labour

force, most1y stemming from immigration from the East. Unemployment feli from 6.8 per cent in 1989 to 5.5 per cent in 1991 (Table 1.2). but rose again above 6 per cent in

19925 .

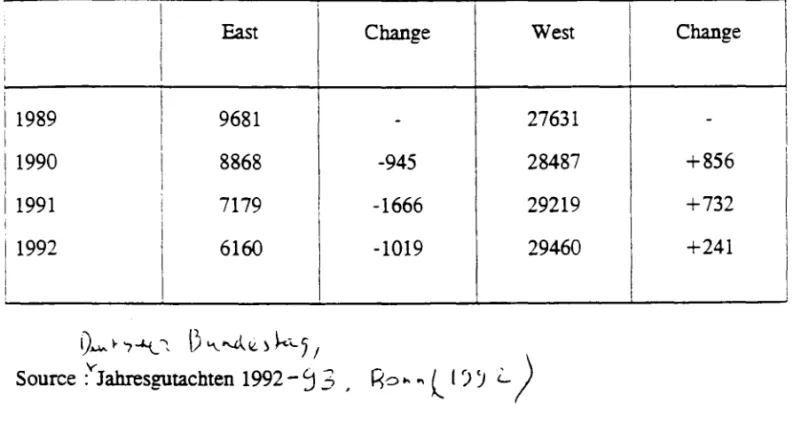

The opposite development of the labour markets in the two parts of the country is even

more pronounced when we look at the changes in employment. This is done in Table

1.3. which shows that employment feli in the East from 9.5 million in 1989 to an

estimated 6.2 million in 1992, or by a cumulated 3.6 million in only three years. During

the same period employment in the West increased from 27.6 rnillion in 1989 to an

estimated 29.5 million in 1992, or by a cumulated 2 million people (Table 1.3).

The shaIp rise in real wages in the East contributed significant1y to the development in

the Eastem labour market. Gross nominal wages in industry rose from 35 per cent of the

West German leveI in July 1990 to about 70 per cent of the West German leveI by mid-1993.

Akerlof et alo (1991) calcula te that immediately after the economic and monetary union only 14 conglomerates employing 8.2 per cent of the East German industriallabour force were viable. With a 50 per cent labour cost subsidy, 37 per cent of the industrial labour force would have remained employed (Table 9 in Akerlof et alo 1991).

In order to understand the damaging and unfortunate development of real wages in the

East for employment and industrial production, severa! factors ought to be kept in mind.

Firstly, in post war West Germany the govemment genera1ly had an attitude of no

5 Ifhidden unemployme01 is taken into &CÇ()\l01. then West German uoemployment rises to 7.6 per cent in 1992.

--

-

-

--

--

-,

-

.--

-interference into wage bargaining which it largely considers to be a private matter

between workers and representatives of firms6 Secondly, wage negotiations in the East

even afier the fali of the wali are still not comparable to wage negotiations in a market economy, where the owners of the fums have an interest in defending profits and the

value of the frrm. Thirdly. labour unions from West Germany provided SUppOIt to

"inexperienced" labour unions in the East and their representatives were also sitting in

the board of the still state owned enterprises. Thus they were "bargaining" to some extent with themselves. Fourthly, labour unions in the West had and still have a vested interest in a rapid increase in wages in the East in order to protect real wages and employment in the West.

The same vested interest can be attributed to West German industry whose prime

objective is and was the conquest of maximum market sbares in the East. The Federal govemment' s benign neglect in East German wage matters can in rum be explained by the political pressure for convergence in the East and its desire to protect the interests of

West German industry. This attitude seems to us totally unjustified given the fact that the

Federal Govemment is formaliy the owner of the enterprises to be sold and thus should also be trying to keep its value as high as possible. And since no true wage bargaining could take place in a non-market economy, the government should have intervened directly under such circumstances. By announcing the goal of income convergence to be

realised as soon as possible the government, in fact, raised expectations and provided

strong signalling for convergence.

To be sure many in the government and outside thought that a high wage differential

between the East and West of Germany would have caused a massive outflow of workers from the East. However, the survey conducted by Akerlof et alo (1991) suggests that unemployment is. at least as important a factor causing emigration as a Iarge wage

6 The Bundesbank has at times during the post war history indíreçt)y influenced incomes policies by threatening intere.st

rate inc:reases if wage rounds would tIlm out unfavourably for inflation or by poaponing intere.st rate reductions until after the outcome of the negotiations

-

-

--

--

_.

--

.--

-differentiaF. Funhennore it is not the actual wage differential which causes emigratioo, but rather the expected wage differential (over a number of yea.rs) conected for the

expected capital gains that workers in the East could have cashed in, if a different

privatisation policy had been pursued. This different policy could have entailed some distribution of shares to ali residents in the East: some, not ali. because the contraI of privatised finos is better left to westem enterprises with the necessary know how. The free distribution ar the sale at a low price of the stock of housing and land could also have induced large expected capital gains and nullified the effect on emigration of even

very substantial wage differentials. These two criticisms to the policy pursued by the

Federal Govemment in the East - too rapid wage increases and a privatisation policy non favouring the formation of wealth on the part of the eastem residents - have been made by several authors8 .

lt is clear that the faster the adjustment of real wages in the East to those prevailing in the West of Germany, the larger is the total investment that is required to bring the productivity of labour of East German workers to the higher real wage. The criticism

that wages were increased too fast in the East has to be judged against the planned

official and private investment effort in the years to come. We shali see that the planned investment effort is substantial, so substantial that the chosen path of rapidly increasing

wages-high investment may tum out to lead to a rapid adjustment of real GDP per capita

in the East, despite its high short-run unemployment costs.

It is unlikely that high real wage growth has major effects on investment as convergence

of real wages to westem levels is at any rate expected in the medium run. By the time a

new project is implemented convergence will already be substantial. If investments are

motivated by low labour costs they will chose Asian location not East Germany. The attraction of East Germany is totally different : availability of a disciplined and skilled

7 This view is backed up by tIle empiricaJ work of Pissarides and McMaster (1990). estimating migration as a func:tion of ",age differeDces or ,.,age growtb differences and unemployment.

8 See for instance Sino and Sino (1991) and Gros and Steinberr (1990). They proposed a participation of East Germans in

fums to be privatized by tIle Trellb,nclanstalt to 510'" do"'n ,.,age increases.

---

--

-

-

-

--

_.

-labour force, a known and tested West Gennan instirutional framework (with ali its

faults). an experienced administration. and fonnation of a rich consumer market.

The major effect of real wage adjusnnent in the East is not on invesnnent, but it

depresses of course profitability of existing frrms and therefore increases the transfer

needs from West Germany. High real wages generate high transfers through various

channels. One in the increased losses of frrms fmanced by the Treuhand: another channel is increasing unemployment that results from more frnns being closed down or

from increasing lay-offs : ando fmally. as unemployment benefits are geared to wages.

they increase automatically with wages.

We look frrst at total transfers to the East of Gennany made by the federal govemment

in 1991 and 1992. before we try to assess the volume of real invesnnent, both public and

private, that sofar has been flowing to the East, Then we compare the figures with net

transfers and invesnnent in the ltalian Mezzogiorno, the locus classicus of transfer waste.

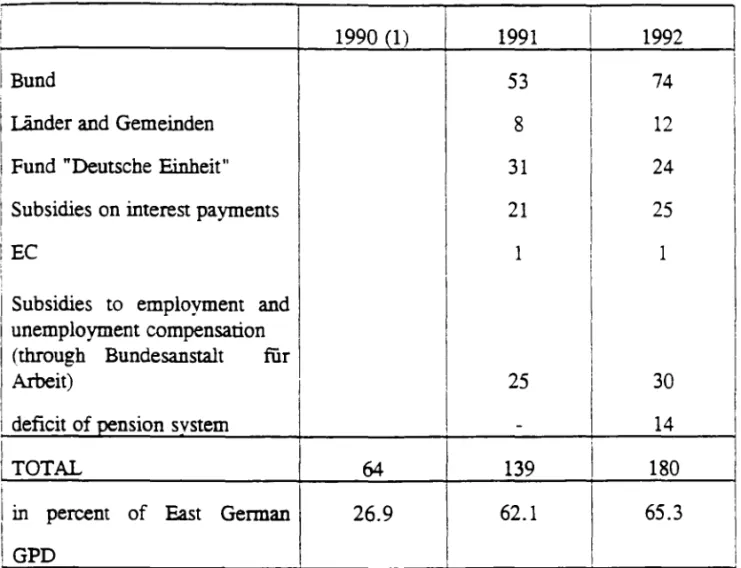

Table 1.4 contains net official transfers from the West to the East of Gennany in the

years 1991 and 1992. Net transfers amounted in 1991 to DM 139 billion and in 1992 to

DM 180 billion. In relation to Eastem GDP these transfers represent 62 per cent in 1991

and about 65 per cent in 1992. Even taking into account that GDP in the East is

depressed, these figures are astonishing. By way of comparison net official uansfers frorn the Center-North to the South of lta1y excluding interest payment on the public

debt amounted to about 31 per cent of Mezzogiomo GDP in 19889 . Table 1.4 also

shows that the largest part of the net traDsfers from the West to the East of Germany comes from the Federal Govemment .

For evaluation of the chances to raise the productivity of labour in the East to Westem

standards and the prospect for economic growth in the furure, one should try to split the

- . figures reported above into current transfers and investment expenditures. Expenditures

--

9 19 per cent However lhe net imports of goo<is and serviees was substantially less: it averaged 20.8 per emt of GDP from 1975 to 1987. This means lhat lhe Mezzogiomo used part of lhe proceeds from Govemment transfers to export in 1970-74 and capital to lhe Center-North or to lhe rest of lhe world. In 1988 lhis export of capital from lhe proc:eecls of government traDSÍers amounted to about 12 per cent in Mezzogiomo GDP. The analysis below sIlows lhat lhis perverse effea is not likely to occur in the East of Gennan)" .---

-

--

-

---

-

-

---.

--

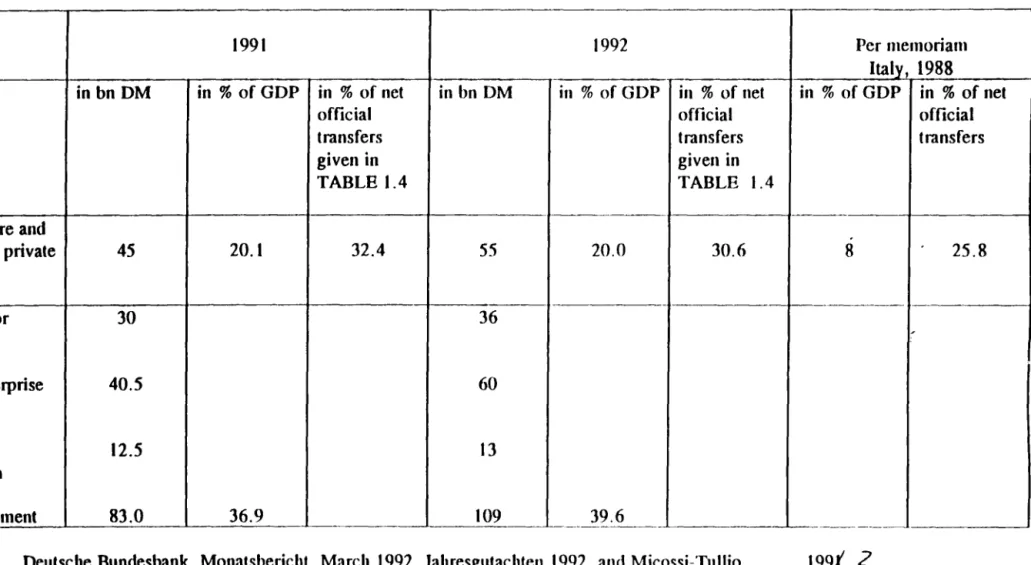

-.

-on infrastructure and subsidies to private investment amounted to DM 45 billi-on in 1991 and to DM 55 billion in 1992 (about 20 per cent of Eastern GDP). The sum of subsidies and of infrastrucrure investment is a measure of the Govemment' s support of the investment process in the East. These figures are summarised in Table 1.5 where it is also shown that public investment expendirures in the ltalian Mezzogiorno were only 8 per cent of GDP in 1988. (This figure excludes, however, the large investments by govemment controlled enterprises).

Table 1.5 also provides data on total investment and its decomposiúon. Total investment

is equal to 40 per cent of Ea.st German GDP. In this connecúon it is important to note

that tax breaks and investments subsidies reduce the cost of a private investment in the

East by about 50 per cento That the expected investment-GDP raúos in the East of Germany are substantially higher than they have been in the ltalian Mezzogiorno is

evident from Figure 1.2, where we report GDP per capita in the South in percent of

GDP per capita in the Center-North, along with the raúos of gross fixed investment to GDP in the South and in the Centre-North.

FIGURE 1.2 about here

We see first that the ratio of gross fixed capital formation to GDP has been always

higher in the South than in the Center-North (but much lower than the one in the East of

Germany) and second that despite the higher investment raúo in the South per capita

GDP in the South has been falling behind since 1975 rather than catching up (from just

over 60 per cent in 1975 to about 52 per cent in 1988). There is obviously a major

problem with the quality of investment expenditures and investment done by government controlled enterprises in the South (the non-decisiveness of economic criteria in project

evaluation), and private investment is also distorted by too generous investment

subsidies. In addition it may be that official investment figures contain a component

which Ms nothing to do with real productive investment as they are blown up by

payments to corrupt govemment and party officials and organized crime.

10

t' . . -'"

-·

~.

.

.

)~

• • • • • • • • • • • 4 • • • • • • •e f . f • • • • • • • • • • •

,.

70.00 60.00 50.00 40.00 30.00 20.00 10.00,

2-o ,Flg.~: Real gap

0'

GOP per caplta between Soulh and North-Cenlral IIaly and share o, gross flxed InvesfmentIn GOP o 1970-1988; - -. .. .. . ...

-

.. .. ...----r~---

-

---

--

-----

-----

---0.00 :-1 -~~-~~~~-~~:_-+---+---+--+---t----+--t-~f---+---+----I R ~ r- r-Ol 00 r-Ol f6...

r-Ol Ol r-Ol...

00 Ol N r-Ol.,..,

r-Ol tO r-Ol N 00 Ol.,..,

00 Ol r-00 Ol :ri tO 00 Ol 18 - r-Ol Ol Ol Ol 00 Ol Ol Ol f • • •,..

Relatlve GOP per caplta -- -- - Gross flxed Investmentl GOP. SQwI.A. . . . .. Gross flxed Investmentl GOP. NaftA

I

S--,'.!J,

~~t:rt

-Io,,-H

t

-"

i-

! i-

--

--.

-_.

-~The ltalian exampIe is cIearIy the one not to follow. We feel, however, that the much larger size of the invesonent effort which is planned for the East of Germany, the

presence of a dull but reliabIe administration, more attention to the economic rather than

the political return on investment, (as shown also by the d.ifferent privatisation policy pursued by the two countries) and little evidence in Germany of investment expenditures being used as a channel to finance parties and organized crime, allow us to look at the

East German experiment with a relatively higher degree of confidence in its success. 10

The privatisation of Eastern firms by the Treuhandanstalt (TIlA) is ahead of schedule

and it is planned to end TIiA operations by 1994. In its selling policy THA has favoured

job guarantees and invesonent commionents by the purchasers rather than selling to the

highest bidder. THA has also favoured quick privatisation to restructuring of the owned

enterprises. Table 1.6 summarizes the achievements of the Treuhandanstalt up to

May 1993. TIiA inherited 270 kombinate with 8.500 enterprises. These were broken up

into 12.672 firms and reca.st as joint-stock companies owned by the THA. After two years of operation, the THA has fully privatised 4.680 of these and partly privatised

5.400 ; 2.350 have been liquidated ; and 2.442 remam. The number of workers in THA

frrms has fallen from 4.2 million to 500.000. In addition, some 15.000 small retail

outlets have been sold off, and 7.000 property units (including 1.085 enterprises) remrned to their former owners.

The THA Ms produced a revenue of 40.6 billion DM from sales of fums, 173 billion

DM of promised future investment, and guaranteed 1.5 million jobs. 11

The

mA

is a technocratic agency enjoying the freedom of action of a privatecorporation, but with the comfort of knowing that its losses will be absorbed into the

govemment budget deficit. With independent legal status, it is free from the political

10 Some other feanues of me "Mezzogiomo syndrome" might onIy emerge at a later suge and invalidate such • ramer positive ._smem. In particular. me _ LãDder rcpraeut a formidable coalition of imerest groups campaigning for redistribution.

This is me preva1ent cause of me Mezzogiomo problem : me more ÚlIn proponional po1iticaJ .,eight of me South UDited in me claims for redistribution and conzrolling me po1itieal sysrem and me admiDistration. lbe uansfer of me capital to Beriin in me bear! of me former GOR. may create me ame problem as me uansfer of me ltalian capital from Turin to R.ome (via FlareDCC).

11 lbe recent economic dowmum bis raised doubts about me enforceability of mese inveaunenu and employment

commitmenu. At times enforcement .,ould simply banlaupt me promocer.

-

-

----

--

--

-.

--.

--

-

--controls required of other quasi-governmental agencies in Germany. Decision-making by the mA's 4.400 employees is centralised and secretive - even exempt from review under administrative law. The TIrA may be challenged under civil law on grounds of

discrimination or monopoly behaviour, but no such suits have yet come to court. 1t is

thus in a unique position : it is accountable neither to the market, nor to polítical or legal authorities.

Up to June 1992, only 366 firms or less than 5 per ceot had been sold to non West German enterprises. The most active foreign countries have beeo the UK, Switzerland and France. The number of East German fmns sold by the Treuhandanstalt by country of origin of the purchasing fino is reported in the lower half of Table 1.6. In terms of jobs guaranteed and invesonent commitments the cootributioo of non German finns is close to 5 per cent.

The invesonent figures reponed above and the speed at which the privatisation is

proceeding induce us to see the future growth prospect of the East of Germany with

some guarded optimism, provided infrastructure investment and privatisation continue at

the same speed for some more years and the 1talian mistakes are avoided. This is despite

the excessive rise in wages and the initial legal mistake to favour restitution to old

owners rather than monetary compensation 12.

Turning to the consequences of the financing effort 00 the West German economic

situation, we look first at govemment finances. Table 1.7 shows the enlarged public

sector deficit, including the borrowing by the special reunification funds (Fund

" Deutsche Einheit" , "Kreditabwicklungsfond" , "EPR Sondervermõgen" ,

"Lastenausgleichsfond"), the borrowing by the post offices, railways and of the

Treuhandanstalt. The overall borrowing is DM 152 billion for 1991 (5.8 per cent of

GDP) and DM 215 billion for 1992 (7.9 per cent). Thus the worsening in govemment

finances is substantial with respect to 1989, when the West German general govemment

12 This error Das been later partially corrected witb tbe so-calIed °Hemmnisbeseitigu.ngsgesetz" (see SiM and SiM) of

Marc:b 15 1991

--

-

-budget deticit was less than one per cent of GDP. The 1991 borrowing needs of the

German govemment were approximately equal in absolute value to the general

govemment budget deticit of ltaly. Undoubtedly, the high budget deticit to be sustained for the years to come, and the Bundesbank' s determination to control inflation have led

to a substantial increase in real interest Iates, particularly of short-term rates. This

increase has crowded-out private investments both in West and East Germany. Due to

the rather low interest elasticity of investment demand this effect is, however, marginal

in relation to the fact that on1y one-third of transfer payments is targeted for

investment13 .

- The direct contribution of East German demand to West German growth stemming first

-

--

-

---

--

--

_.

-

_.

-

--

-

--from the DM -endorsement of the monetary reform and later --from wage increases was

very substantial especially in the 2nd half of 1990 and the first half of 1991. Table 1.8A

summarizes the positive net contribution of East German demand and the negative rest

of the world net contribution, as estimated by the Bundesbank.. The two net

contributions have been to a large extent offsetting each other, as Germany was running

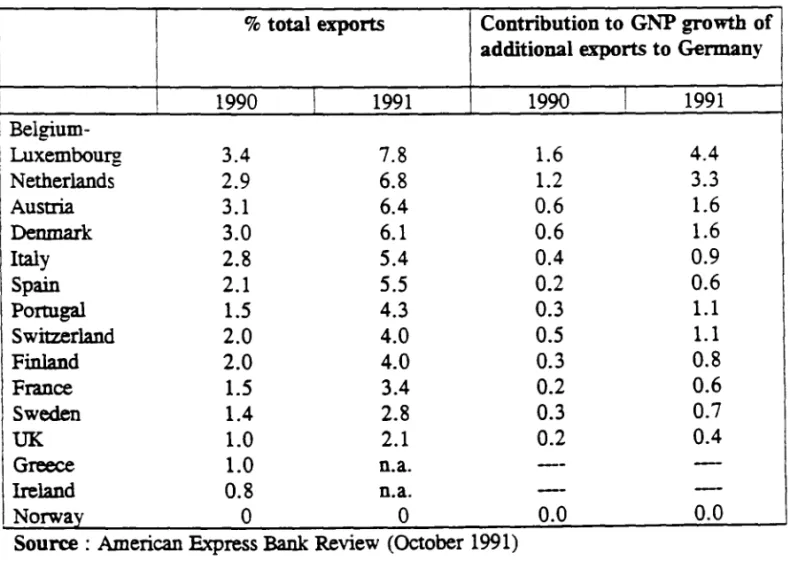

down its huge current account surplus. Table 1.8B shows that Germany's closest

neighbours have benefited from higher demand in East Germany as much, or even more,

than West Germany.

This rather long but still incomplete overview was felt necessary not on1y to give an idea of the financiaI, investment and privatisation effort in Germany but above ali to lay

the ground for an educated guess conceming the growth prospects of the Eastem part of

Germany in the next ten years or so. Before we do this, it may be instructive to look at

the recovery of GDP per capita in West Germany after world war

n.

In Figure 1.3 thedotted tine represents the trend GDP per capita in West Germany calculated by applying

to the 1938 real GDP per capita of the whole of Germany the average annual geometric

13 DespiU lhe 'Solidarpakt' lhe eieficit of lhe federal govemmem is comiDuosly revised upwarci, whilst StaDciplatz Germany becomes ooe of lhe most heavily taxecl among eievelopecl coum:ries. Reccnt 10$$ of compeátivity of German iDcIIIstry is a clirec:t

conseqUeDCe of uniíication. i.e. high taxes anei high real rates of imerest. lnvatment in East Germany alreaeiy lias cIeclinecI in 1993

and prolongecl recesslon combinecl wilh coDStraints to be faceci by budgeury policies may )eopardize transfers anci investment

tlows to East Germany .

13

-growth

rate recorded from 1880 to 1938 (1. 742 per cent per year). The actual real GDPper capita from 1948 to 1969 is represented by the solid line. The gap between actual - real GDP per capita and trend GDP was 40.9 per cent in 1948. The causes of this gap

-

-

-

-

-

-were war destructions, losses of territories with higher GDP per capita, the disorganization of production in the aftermath of the war and the monetary disorders of 1945-48. The figure tells us that actual GDP per capita exceeds trend GDP for the first

time in 1965 and for the second time in 1968. Afier that year it always stays above

trend. Not considering the very disorderly years from 1945 to 1947, this simple

simulation tells us that it took almost 20 years for West German real GDP per capita to

recover from the effect of the war14 .

(Fig. 1.3 about here).

In the case of East Germany after the fali of the wali, using the labour force rather than

population as the denominator (because for 1992 we could find only official forecast for the labour force), the gap with respect to West German GDP was 73 per cent in 1991 and an expected 68 per cent in 1992. Thus the gap was much larger than in West Germany in 1948. Catching up theories of economic growth suggest that the larger the gap with respect to the technologically advanced country, the faster the catching up

should be. Barro and Sala-i-Martin (1991) have made a systematic attempt to analyse

convergence. They conclude that growth differentials are genera.lly smali and diminish

on the convergence path. According to their estimates, if East Germany behaved on

average it would grow initially at close to 3.5 per cent a year and then gradually

converge to the West German growth rate of 2 per cent a year. Of course, East Germany

is expected not to behave according to cross-section average for reasons already enumerated.

Dombusch and Wolf (1992) examined those economies that have known the best growth

performance. They conclude that even if one took the average of the best decades of the

14 For a similar analysis _ Boràlardt (1982. 1985) and for a very similar C:ODClusion reached by using a 16 equation models oftbe German economy and simulating it from 1936. _ Sommariva and Tullio

-

--

-

---

--

--

_.

-_.

-

-25CDI

115CDI

lCXl) 5CD1,3

Figo.ft. . Real GDP per capita and ~rend GDP per

capita in West Ger.many, in eM of 1913, 1948-1969

...

--

-

.-

-o

+--+~--+-~~--~~-+~--+-~~--~~-+~--+-~-+~~51

cn

·Sourc:e: Sommariva and Tullio (1987) - - - ACTUAL GOP - - - TREND GOP

-

-iastest-growing countries (Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan) when

they closed 15.6 per cent of the gap. Bastem Germany still wou1d need almost three

- decades to achieve 80 per cent of Westem productivity, starting from ao initial gap of 70

per cent. However there are reasons for supposing that the catching up cou1d be faster in

--

_.

-

-East Germany than in West Germany after the war or in other countries. First, the

investment effon which is underway and was described above is much more substantial

than in the West of Germany in the years following 1948.15 Of considerab1e imponance

is also the fact that the East of Germany is relative1y small in relation to the West of the

country, whose federal govemment is fumly com.mitted to its fast recovery. Otherwise the observed ratios of investment to GDP cou1d not have been reached.

Second now there is a greater abundance of capital in the world than in the 1950s. West

Germany, by running down its huge current account surp1us has staned to use the net foreign assets accumulated in previous years.

Third, savings of househo1ds in the East is increasing rapidly after the initial spending

spree in 1990. By 1992 it reached West German levels (Table 1.9) and it is not to be excluded that it will continue to rise above the West German level as the stock of wealth of East German residents is quite low and as uncertainty concerning furure employment prospects will remain high for several years.

Fourth, the human capital in the East is very high as education was one of the primary

objectives of the socialist govemment. Although up-to-date technical skills may be

lacking, they can be learned fast if the basic education is good. Before world war

n

theEast bad a solid industrial base; although some areas were relatively depressed, the area

of the later Soviet zone had in 1936 a higher GDP per capita than the areas

corresponding to the American and the French zones16 •

Finally, emigration from the East to the West of the country which has so far been

substantial will he1p speeding up the process of catching up of GDP per capita. This

lS In West Gennany the ratio of gTOSS private invesunem to NNP averagec! 23_6 per cem in the 1950s and 24.7 in the

1960s. The ratios to GDP wouJd of course be smaller. 16 See Abe1shaueT (1983) for the data.

•

T

T

.,.

í

--

--

-

-

--

_.

-"safety" valve was not available on a large scale for Germans after world war

n

as thewhole of Europe was in shambles and unemployment was everywhere very high.

For all these reasons we do expect the catching up to last as much as 15-20 years, and

not a generation or more. This assumes that the investment effon on the pan of the govemment continues at about the same scale for at least 5-10 more years, that private investment will pick up when the propeny rights questions are settled and that wages do

not continue to dose the gap. lt would not be inappropriate if the federal govemment

intervened d.irectly from now on in the wage bargaining process in the East.

Extrapolating to 2005 the annual average geometric growth rate of GDP per person in

the labour force recorded in the West in the period 1985-1992 (1.6 per cent), Eastem

GDP per person in the labour force would have to grow at an average geometric growth

rate of 10.5 per cent per year for 13 years to catch up with the Westem leveI. This does

not appear unthinkable in view of the

special

factors identified above and barring majoroil shocks, the maintained uncenainty about propeny rights in the East and a too restrictive monetary policy during the adjustment process on the pan of the Bundesbank.

lt is however unlikely as too many ideal conditions would need to be fulfilled. A more

sober scenario would produce convergence in 15-20 years rather than in 15 years.

--

-i

-

-

-

--

--

-Table 1.1 - Industrial Production in Central and Eastern Europe, 1989-92,

percentage changes

i

1989 1990 1991I

1992 II

I

Poland -0.5 -24.2 -14.0 4.2 Czechoslovakia 0.8 -3.7 -23.1 -14.0 Hungary -1.0 -9.6 -19.1 -9.8 Romania -2.1 I -19.0 -18.7 -21.8 I Bulgaria -1.1 -17.5 -27.8 -20.0 Bastem 2.3 -28.1 -53.5 0.9 GermanvSource : Plan Econ., Review and Outlook, December 1992 and Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Repons

--

-

-

-

-

-

-

-_.

--

-I I I I I I I I I ! I

Table 1.2 - Unemployment rate in the East and West of Germany 1988-92, and

in Germany 1928-32 ; annual averages

EAST I WEST GERMANY I official total unemployment unemployment 1928-32 (1) (2) i 1988 n.a. n.a 7.6 1928 4.8 : 1989 n.a. n.a. 6.8 1929 5.8 ! 1990 2.6 19.6 (3) 6.2 1930 9.7 1991 10.5 35.9 5.5 1931 14.3 1992 16.0 39.9 6.0 1932 17.6 I ! D~ ~ )~)

Bu

"'\tr~""'l..j / ,,/Source : Jahresgutachten 1992-93 des Sachverstãndigenrats, Bonn

~l199y

(1) Includes short time workers (appropriately weighted), workers temporarily

subsidized by the Govemment (Arbeitsbeschaffungs-massnahmen), workers

involved in retraining programmes and early retirements.

(2) Source : lnstitut fiir Konjunkturforschung, Konjunkturstatistisches Handbuch,

(3)

1933 and Sommariva and Tullio (1987), (p. 168)

Unemployment during 4th quarter of the year

I

18

L

I

-=t

ITable 1.3 - Employment in the East and West of Gennany 1989-92 (in thousands)

--

East Change West Change-

i-

i I1989

9681

-

27631

--

I-

1990

8868

-945

28487

+856

-

1991

7179

-1666

29219

+732

-

i-

1992

6160

-1019

29460

+241

--

Source

0-,-" .. .,

:YJahresgutachten 4...~

\) "'-~" ~

1992-j

h.-...

5 /

3,

KOk",l (')

J

i... )--

19

--

--

-

--

--

-

---

-

---

--

...

-

-Table 1.4 - Net official transfers from West to East of Germany, 1991-92 (in

billions of DM)

I

BundLãnder and Gemeinden Fund "Deutsche Einheit" Subsidies on interest payments

EC

Subsidies to employment and unemployment compensation

(through Bundesanstalt für

I

Arbeit)

deficit of pension svstem TOTAL

m percent of East German GPD 1990 (1) 64 26.9 1991 53 8 31 21 1

25

139 62.1 199274

1224

25

1 30 14 180 65.3(1) for comparison, net official transfers from the Center North to the South of ltaly

were in 198831.0% ofMezzogiorno GPD.

2-Source : Deutsche Bundesbank, Monthly Reports and Micossi and Tullio (199/), Table 5

20

-r-'~:

..

-f ~ f f • f f f f .4 f

I

.

f f f f • f f f f f f • f f f f f f f • f f f f • f ~ f f • f • --f .... -f ... • , :1 N ... • ••

..

Table 1.5 - Investment expenditures in the East of Germany : 1991-92

1991 1992 Per memoriam

ltaly, 1988

in bn DM in % of GDP in % of net in bn DM in % of GDP in % of net in % of GDP in % of Ilet offieial offieial offieial trallsfers transfers transfers givell in given in TABLE 1.4 TABLE 1.4 Infraslructure alld subsidies to private 45 20.1 32.4 55 20.0 30.6 8 25.8 investmelll Public sector 30 36 investments , Private enterprise 40.5 60 investments Private 12.5 13 construction Total investment - - - 83.0 36.9 109 _. - - 39.6 - - -

-Sources: Deutsche Bundesbank, MOll3tsbericht, March 1992, Jahresglltachten 1992, and Micossi-Tullio, 190/

2...

' - - - '

Per memoriam : total sums pledged by private purchasers for investments in firms purchased from the

Treuhandanstalt betweell June 1990 alld end of May 1992 : 138.5 bn DM (total finlls sold 7.613)

- Table 1.6 - Fmns privatized by the Treuhandanstalt (1)

-

i No of fums privatizedI

J obs guaranteed Investtnents No. of fums still to-

commitments in be privatized-

I billions DM-

: I...

I Sept. 30 1991 3788 719,763 55.2 10537 I I-

, I I Mid June 1992 7613 1,170,000 138.5 4637-

, ,--

I Mid I May 1993 10080 1,500,000 173.0 2442 i I i--

(1) By end may 1992 foreigners had purchased 366 fums, subdivided as follows :--

NO.offums Jobs guaranteed in Investtnent-

purchased thousands commitments in bn-

DM--

UK 68 14.2 1.6-

S witzerland 68 14.1 0.7-

France 48 14.7 2.3--

Austria 43 8.6 0.5-

HoIland 29 5.7 0.9--

V.S.A. 20 4.8 1.5-

Sweden 19 3.5 n.a.--

ltaly 17 4.6 0.4-

_.

Others 54 n.a. n.a.-_.

366-

-

Sources: Jahresgutachten (1991 p. 70, Table 11, La Repubblica, June 20 1992-

andn

Sole 24 ore, June 2--

22-

-

-

-_.

-

_.

--

~-:.-.-_. -I"" - • . . • Table 1.7Tbe consequences of reu~cation on German government fmances

1989-93, billion DM

1989

I

1990 I 1991 1992Financing requirements I

1)

German

budget balance -22.2 -91.1 -123.1 -120.0of which: - Federal govemment -15.0 -45.2 -53.2 -41.0 - Wesrem Lãnder -7.6 -19.5 -19.0 -14.0 - Easrem Lãnder ---

---

-10.8 -15.5 - Wesrem local +1.7 -4.0 -5.5 -8.0 communities - Easrern local---

---

-1.4 -6.5 communities-

German Unification---

-20.0 -30.5 -24.0 Fund - Orher--

-1.3 -5.5 -11.0 2) Social securiry 13.5 16.5 13.0 -28.0 Total (1)+

(2) -8.7 -74.6 -110.1 -148.0 3) Treuhand, Postal---

--

-41.1 -66.5 Services, Railways,Public Sector, Housing

(Total (1)

+

(2)+

(3) -8.7 -74.6 -152.2 -214.5 as a percentage of GNP 0.4 3.1 5.8 7.9 Public Debt Total (1)+

(2) 928.9 1,053 1,170 1,318 as a percentage of GNP 41.4 43.4 44.7 48.6 Total (1)+

(2)+

(3) 1,039.2 1,225 1,377 1,589 as a percentage of GNP 46.2 50.2 52.3 58.8Source: DlW, OECD, Buruiesbank, Ministry ofFinance

- '

--

-Table 1.8A - Net contribution (1) of East German and rest of the world demand

for West German goods and services to West German economic

growth, in per cent or West German GDP.

i

! East German demand Rest of World Sum of (1) and Per memoriam

,

I

i Demand (2) West

German

I

I

(1) (2)I

real 2TOwth I 11990 IS 0.8 -1.9 -1.1 +3.8 i i I 2S +4.6 -4.3 +0.3 +5.2 ! I I -5.8 +0.4 +4.5 1 1991 IS +6.2 ,- Source : Deutsche Bundesbank , M :, F\{A b

-

'7 O"llhr

_ (1) in relation to the same period of previous year

-

-_.

-_.

-Table 1.8B - Tbe direct benefit of German integration on the outside world :

I I I

Belgium-I

Luxembourg Netherlands Austria Denmark ltaly Spain Portugal Switzerland Finland France Sweden UK Greece Ireland NorwayAdditional exports to Germany due to unification and their contribution to GNP (in percentages)

% total exports Contribution to GNP growth or

additional exports to Germany

1990 \ 1991 1990

I

1991 3.4 7.8 1.6 4.4 2.9 6.8 1.2 3.3 3.1 6.4 0.6 1.6 3.0 6.1 0.6 1.6 2.8 5.4 0.4 0.9 2.1 5.5 0.2 0.6 1.5 4.3 0.3 1.1 2.0 4.0 0.5 1.1 2.0 4.0 0.3 0.8 1.5 3.4 0.2 0.6 1.4 2.8 0.3 0.7 1.0 2.1 0.2 0.4 1.0 n.a.--

-0.8 n.a.-

-O O 0.0 0.0- Source: American Express Bank Review (October 1991)

-

-I I 24-f

-

-

--

---.

-

_.

--

--

-

--'I'able 1.9 - Savings rate of bousebolds, 1990-92

i

1990i

1991 I 1992 East 1.9 7.2 12.0 West 13.9 13.6 13.0Sources : Jahresgutachten (1991) and Mondo Economico May 30, 1992

"C .. ",-_E •.

Ei:::'\üTECA

fUNDAC~O GEleUO VARGAS

-~

~

~

-!

!

- 2. Wage and price developments in the West or Germanv

---

--

-

--

--

-

-

--.

--.

-It is often argued that unificaúon represented a major demand shock for Westem

Germany. This is not obvious a priori as increased demand in Ea.stem Germany did not

fali like manna from heaven. It is the result of West German transfers as argued in

Secúon 1 and hence the quesúon whether it resulted in a posiúve demand shock depends

on the magnitudes of two effects. First, given that transfers are either financed through

taXes, increa.sed borrowing or inflaúon. cet. par., disposable real income in Westem

Germany actually feli by an amount up to the transfer. Second, in the integrated markets of the Community higher East German demand should benefit ali Community (and oon-Community) countries. Table 1.8 in secúon 1 showed indeed that the Benelux countries

benefited from integraúon possibly more than West German producers, without carrying

the burden of fmancing the transfers.

Unificaúoo, if it had any effect on prices via increased demand, shou1d have had as great

an impact on Benelux inflation as 00 West German inflation. The increasing inflaúon

differential moving Germany from the fioor of the Community inflaúon league to the upper úer, must therefore be explained by other factors.

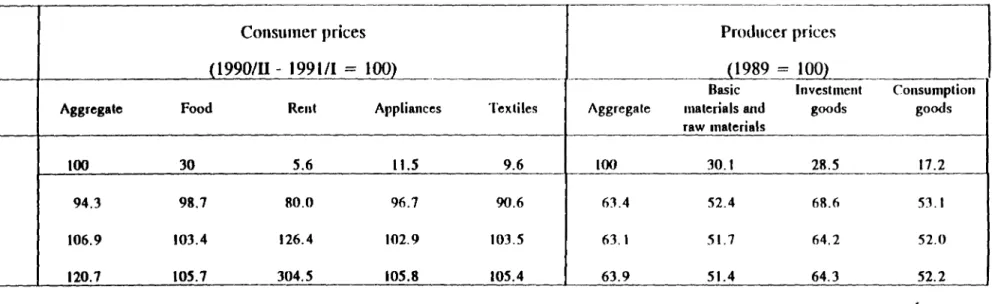

Before we develop our thesis that increased inflation was caused by a structural change

in wage behaviour, reinforced by the pass-through of higher wage taxes, we wish to put

aside another potential candidate for explanation, namely the initial impact of the price

reform in the East after unification. Table 2.1 shows that since 1989 producer prices in

East German manufacturing have fallen by about one third. Consumer prices have riseo

by about 20 per cent since 1990/91 mainly due to higher prices of imported goods in relation to domestic goods and due to the increase of non-traded goods prices such as

rents from their abnormal low leveis. Not counting the adjustment of non-traded goods

prices, the contribution of East Germany's price freedom to overall German inflation, if

anything, has been negative (barring any possible demand effects on West Germany).

-.

!-

-

-

--

---.

-

_.

-

-These remarks concem inflation in the whole of Germany. lt is to be noted, however,

that what is generally called "the Gennan inflation rate" is only the West German inflation rate.17 At any rate what we wish to explain is the West Gennan inflation rate.

Obviously, this is not the right focus for monetary policy as we shali argue in Section 3. Then, where does the increase in the West German inflation rate come from ? We argue from the wage side.

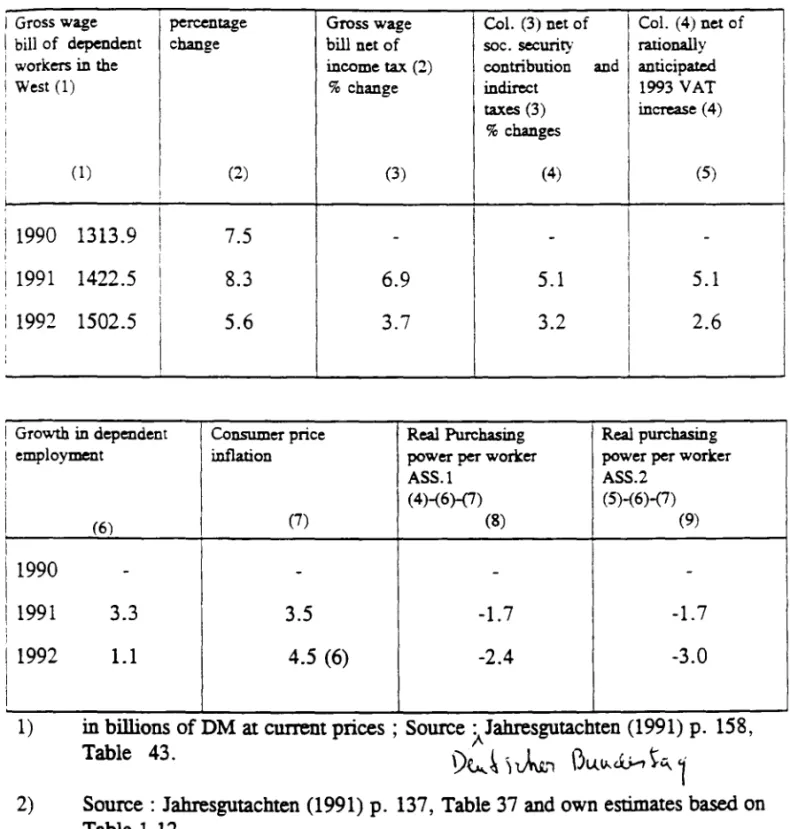

A strong influence on wage inflation arose from a rather tight West German labour market (despite massive immigration from the East) and above ali from the attempt by workers and labour unions to benefit from the expected unification boom and to shift forward the increased income and excise taxes which had been passed through Parliament in 1991 to help fmance the cost of reunification. The increase in indirect taxes contributed in rum in a significant way to the acceleration of price inflation which fed on wage demands. Table 2.2 summarizes the main tax increases which hit dependent labour in one way or another.

The high wage growth in 1991 can be explained by the tight labour market, and the

attempt to offset actual and anticipated tax increases (see Table 2.2). To illustrate the amplirude of anticipated tax increa.ses, Table 2.3 computes the effect of the above tax

1

increa.ses on the after-tax real wage of workers. A "I.:~. ~ ...

""-"-.1'-According to our calculations in 1991, despite the

larg;~~~

wage~creasé·

--

of over. .

10% , the real afier tax wage feU by 1.7 per cent and in 1992 by even more. The

"aggressive" policy of the labour unions in the West has cenainly not succeeded in

preventing a further drop in the after tax real wage of workers. It is interesting to note

that German policy-makers were faced in 1991 with a major dilemma : by announcing

large tax increa.ses for 1992 and 1993 so much in advance they contributed to the

stabilisation of financiai markets but significant1y destabilised thereby labour markets.

17 For example. sec lhe statistical pages ofThe Economist. Th_ lhe German inflation rate for May 1992 to May 1993 say.

is indic.ated as 4.2 %.