ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Land

Use

Policy

j ou rn a l h om ep a ge : w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / l a n d u s e p o l

Public

policies

creating

tensions

in

Montado

management

models:

Insights

from

farmers’

representations

Teresa

Pinto-Correia

∗,

Carla

Azeda

ICAAM–InstitutodeCiênciasAgráriaseAmbientaisMediterrânicas,UniversidadedeÉvora,PólodaMitra,Ap.94,7002-554Évora,Portugal

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received25February2016

Receivedinrevisedform19February2017 Accepted22February2017

Availableonline1March2017 Keywords: Montado Management Decay Representations Farmers Conflicts

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

TheMontadoisthesilvo-pastorallandusesystemdominantinSouthernPortugal,andsimilartothe DehesainSouthernSpain.Thesesystemscombineanopentreecoverofcorkandholmoakswithgrazing intheunder-cover.Despitetheacknowledgedvalueofthesesystemsduetotheiradaptationtothe scarcitybiophysicalconditionsofSouthernIberia,theuniquenessofcorkproduction,thebiodiversity valuesandthesupportofmultiplepublicgoodsandservices,inPortugaltheareaoftheMontadois decliningeveryyear.Ithasbeenshownbeforehowthisdeclineisrelatedtoincreasedgrazingpressure anduseofinadequatesoilmobilizationtechniques.Supportedonsocialsciencestheoreticalinsights, thispaperfocusonthefarmersdecisionprocess,andtherepresentationsthatsupporttheirdecisions. Theanalysisisgroundedonalargescalesurveyfollowedbyin-depthinterviewstoMontadofarmers. TheresultsshowthatthereisanunderlyingconflictbetweenfarmersrepresentationoftheMontado andthepracticestheyareapplyingintheireverydaymanagement.Dominantrepresentationsofthe Montadobyfarmersrelystronglyonthetreecoverandtheforestrycomponentofthesystem.While theirmanagementisstronglyfocusedonthelivestockandgrazingresources.Farmersareabandoninga resilientthinkingoftheirfarmsystemconsideringthefactorsinternaltothesystem,toadaptanexternal, driverorientedrepresentationoftheirfarmsystem.CAPcoupledpaymentsareseenasthemaincause ofthischange.Ifthepolicyconstructionremainsinitspresentstate,theresilienceoftheMontadoasa complexsocio-ecologicalsystemisthreatenedintheveryshortterm.

©2017ElsevierLtd.Allrightsreserved.

1. Introduction

The Montado is the silvo-pastoral system dominant in the landscapeofsouthernPortugal,andequivalenttotheDehesain southernSpain.Theselandusesystemsoccupyapproximately1M hectaresinPortugaland 3MhectaresinSpain,constitutingthe paradigmaticlandusesystemsandlandscapesofsouthernIberia (Aronsonetal.,2009;Ferraz-de-Oliveiraetal.,2016;Pinto-Correia, 1993;Pinto-Correiaetal.,2011).IntheMontado,thereisatree coverdominatedbyevergreenoaks,mostlycorkoak(Quercussuber L.,1753)invaryingdensities,andpasturesintheundercover.These maybenaturalorimprovedpastures,andoftenthereisdispersed shruborpatchesofshrubinthemostnon-accessiblepatches.The livestockfeedonthepasturesandalsoprofitfromthemastsand acorns,aswellastheyoungtreeshoots.Inthedryseason, live-stockfoddermayalsobeproducedinother,moreopenplotsinthe farm.InabalancedMontado,thegrazingpressureissuchthatthe

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:mtpc@uevora.pt(T.Pinto-Correia).

encroachingshrubisavoidedandnaturalregenerationofthetrees ispossible.

Despite its adaptation to the scarce natural resources and variability of theclimate, itsacknowledged qualities as a High NatureValuefarmingsystem,a highlyattractivelandscape,and aregionalidentityfundament,thesesystemsareneverthelessin decay.RecentstudieshaveshownthattheMontado’stotal exten-sionhasreducedinthelast25years,with5000halostonaverage per year (Costa et al., 2011; Godinho et al., 2014, 2016).This decreaseisnotprimarilyduetocutsinthetreecoveror replace-mentofthesilvo-pastoralsystembyanotherlandusesystem.Itis causedbyaprogressivedeclineinthetreecoverandareduction innaturaltreeregeneration,andthusareductionintreedensity, which in turnleads tolargerand larger openings inthe Mon-tadolandcover(Almeidaetal.,2013;Godinhoetal.,2014,2016). Whenthetreesaremissingorintoolowdensity,thereisanopen grazingorshrubarea,butthecomplementaritybetweengrazing activitiesandthetreelayerislost,andtheMontadohasbeen dis-mantledasasilvo-pastoralsystem.Consequently,itisdifficultto maintaintherecoveryofthetreecover,whichtraditionally regen-eratedbynaturalreplacementoftheoldtreesbyyoungshoots http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.02.029

(AcácioandHolmgren,2012).Withoutthetreecoverthereisno Montadoandtheconstraintsimposedbythenaturalenvironment areastronglimitingfactorforotherregenerationactionsorfor otheruses.Asithasbeenprovedinothersituationsthroughout theworld,thedegradationofforestecosystemsduetotreecover lossandfragmentationhaslong-lastingandnegative environmen-talconsequences,suchasspeciesextinction,waterandsoilquality degradation,and invasive species, and istherefore a subject of upmostconcerninterms ofpublicpolicy(HartelandPlieninger 2014;Liuetal.,2016).

Previousstudieshaveshownhowthetrendtowardsan intensi-ficationandspecializationoflivestockproductionintheMontado iscloselyrelatedtothedecayofthetreecanopyinthegrazing areas,andthusthedeclineof thesystem(Godinhoet al.,2014, 2016;Morenoetal.,2014).Evenifotherfactorsalsoplayedarole, theCommonAgriculturalPolicy(CAP)anditsspecificapplication toPortugalhavebeenseenasthemaindriverforthis intensifica-tioninthelasttwodecades:livestockpaymentshaveremained coupledtothetotalnumberofanimalsandcattlepaymentshave progressivelyincreasedwhilesheeppaymentsarekeptratherlow (Almeidaetal.,2013;Guerraetal.,2015;Guerraetal.,2014).There arethusdifferentandsimultaneouschangeswhichcontributeto increasedpressuresonthetreecoverandonthegrazingresources intheMontado:replacementofsheepbycattle,replacementof lightindigenousbreedsofcattlebyheavierbreeds,increaseinthe numberofcattleheads,andshrubcontrolpracticesusingheavy machinery.Whiletheformerleadtoexhaustionofthenatural pas-tures,disappearanceoftheyoungtreeshoots,damagetotheyoung trees,andsoilcompaction,thelatteraffectsthesystemasitleads mainlytosevere damageto thetreeroot system.Thenational discoursewithinthefarmingsector,followingthespecialization paradigm,hascontributedtowardsreinforcingtheintensification effectdrivenbytheCAP(Fragosoetal.,2011;Pinto-Correiaand Godinho,2013).

Nevertheless,analysesoftheprocessesofchangeinlanduse and landscapesciences tell usthat policies and sector orienta-tionsdonotdirectlyaffectthelandscapeorlanduse;theyaffect thefarmers,whotakedecisionsthataffectandaltersaidlanduse andlandscape.Inordertounderstandhowpoliciesaffectthefarm and interplaywith otherfactors,the analysisneedsto empha-sizetheroleofthefarmer(HerzfeldandJongeneel,2012).Farmers takedecisionsaccordingtoacomplexvaluesystemand manage-mentstrategy.Therefore,thefarmsystemsapproachconsidersthe farmas aunit composedofthefarmerand hismentalmodels, preferences,goals,abilities,etc.,andthephysicalfarm,witha vari-etyofsubsystemsthatincludeanimals,crops,buildings,finances, etc.(Darnhoferetal.,2012;Milestadetal.,2012).Thetheoretical backgrounddevelopedbysocialsciencesonfarmsystemshelps ustounderstandthepositioningofthefarmer,orlandmanager, inthecomplex systemof hisorherfarm anddealing withthe institutionalframeworktowhichhe/sheissubject(Cochet,2012; Schermeretal.,2016;HerzfeldandJongeneel,2012;Noeetal., 2008).Thus,understandingprocessesofchangeincomplexland usesystems suchas theMontado,which ultimately alsoaffect thelandscape,requiresanin-depthunderstandingofthefarmer’s decision-makingprocesses(Darnhoferetal.,2012).

Thisiswhatthispaperisabout.Thegoalofthepaperistobring forwardananalysisofthedecision-makingprocesscharacteristics ofMontadolandownerstoday.Thepaperaimstoshedlightonthe differentrepresentationsthatthelandownershaveofthissystem andtheexistingconvergence,butalsoconflict,betweentheirvalue setandactions,ultimatelyconstitutingaframeworkforthe diffi-cultconservationofabalancedMontado.Inordertoaddressthese issues,thepaperisbasedonanempiricalanalysisundertakenin centralAlentejo,inthemunicipalityofMontemor-o-Novo,where

theMontadostillcomprises60%ofthemunicipality’stotalutilized agriculturalarea.

2. Materialandmethods 2.1. Thecase-study

LocatedintheregionofAlentejo(SouthernPortugal),withan areaof1,232.1km2andapopulationdensityof15.1hab/km2,the

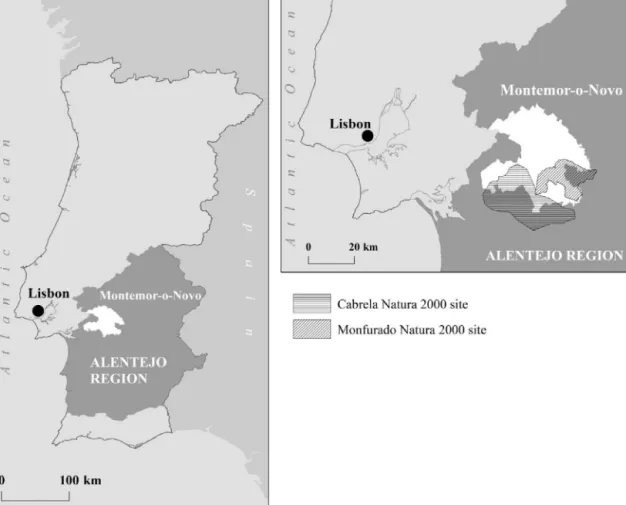

conditionsin themunicipalityof Montemor-o-Novo(Fig.1)are generallyfavourabletosilvo-pastoral production.Theclimateis typicallyMediterranean,withmarkeddifferencesbetweenthedry seasonandtherainyseasontemperatureranges.However,dueto themunicipality’slocation,less than100kmfromthecoastline, thereishighprecipitationandmildtemperaturescomparedwith southernPortugalasawhole.Likewise,thereisapredominance ofgranitemother-rockandrelativelydeepsoilsincomparisonto theaverageinAlentejo.Despitethepresenceofsignificantrugged surfaceareas,thelandscapeisdominatedbyplains.

AsinthewholeofAlentejo,theMontadofarmsaremainly large-scale,family-ownedestatesbetween100and1000ha,andinsome casesbetween50and100ha.TheMontadorarelycoversthetotal areaofthefarm,thoughitusuallycoversthelargestpart−the remainingopenpastures−whicharealsousedforthelivestock production.Usually,thisprimaryactivityiscombinedwithcork andwoodproduction,aswellaswithannualcropsusedforforage. AsatestamenttothehighnaturevalueofmanyoftheMontado areas,themunicipalitylandpartiallyfallsundertwoNature2000 sites:Cabrela(15%ofthemunicipality)andMonfurado(13%ofthe municipality).

Most frequently, farmers have inherited the farm as direct successors or through marriage. In some cases the land has been boughtrecently or is leased fromthe traditional owners. Montemor-o-NovoisthemunicipalityinPortugalwiththe high-estproportionoffarmerswithauniversitydegree,andalsoamore favourabledemographicdistributionthanthePortugueseaverage: 40%ofthefarmersareover65yearsold,whileatthenationallevel thisrateis52%.Thisprofileofmoreeducatedandyoungerfarmers thanthenationalaveragecanbeexplainedbyacombinationof fac-tors,buttheproximityofthemetropolitanareaofLisbon(100km) surely contributestothehigher capacityof themunicipalityto attractandmaintainyoungerandwell-educatedfamilies. 2.2. Methods

Theanalysisisbasedonin-depthinterviewswithselected Mon-tadofarmersinthemunicipalityofMontemor-o-Novo.

Priortotheseinterviews,inafirststepoftheanalysis,adetailed surveyofthefarms’andfarmers’ characteristicswasappliedto arepresentativesampleofthefarmsinthemunicipality.Froma totalof865farmunitsinthemunicipality,328havemorethan 50ha,andarethuslikelytobeMontadofarmsorfarmswherethe Montadolandcoverissignificant.Inthefirststep,51oftheselarge farmunits,spatiallydistributedinthewholemunicipalityterritory, weresurveyed.

Thefirststepsurveyconcernedfarmandfarmer characteris-tics,farmermanagement options andhis/her attitudes towards farming,theenvironment,themarketandpublicpolicy.Acluster analysisoftheresultshasledtotheidentificationofthreetypes of Montadofarmers:1)productivist livestockfarmers (58%), 2) entrepreneurcattlefarmers(35%),and3)multifunctional innova-tive(7%)(Almeidaetal.,2013;BarrosoandPinto-Correia,2014). Theproductivist livestockfarmersaremainlyfull-timefarmers, highlyfocusedonincreasingproduction andthereby increasing theirincome,highlydeterminedbytheCAPpaymentsofthe1st

Fig.1.LocationoftheMontemor-o-Novomunicipality.ThemunicipalityislocatedinthecentralAlnetjoregion,100kmfromthemetropolitanareaofLisboa,anditincludes largeareasoftwoNatura2000sites:MonfuradoandCabrela.

Pillar.Theentrepreneurcattlefarmersarealsofull-timefarmers, whointroduceinnovativepracticestothefarm,suchas convert-ingtheextensivecattleproductiontoorganics,forexample;they receiveboth1stand2ndPillarpayments.Themultifunctional inno-vativegroupmayhaveotherjobsbesidesfarmingand,inanycase, haveotherincomesources.Themainincomesourceinthefarmis relatedwithotheractivities,suchashuntingortourism,andcattle productionisnotthemainpriority.Manyofthemreceiveno pay-ments,orwhentheydo,theyare2ndPillarpayments.Onlyinthe lasttype,whichisbyfartheleastfrequent,istheaveragegrazing pressureintheMontadobelowwhatpreviousstudieshaveshown tobeassociatedwiththetreecoverdecline(Godinhoetal.,2014, 2016;Almeidaetal.,2015).

Fromthose51farmers,andfollowingtherelativedistribution inthetypology,15farmerswereselectedfora semi-structured interviewinasecondstep:8oftype1),6oftype2)andoneoftype 3).Twoofthesearewomen,theothersaremen.Theirprofileand thefarmcharacteristicswereknownbeforehandfromthesurvey data.Theinterviewaddressedquestionsaimingtounderstandthe farmers’viewpoints:a)opinionregardingthetypologyproduced anditsaccuracywithrespecttothemselvesandthefarmersthey know;b)representationoftheMontado;c)requirementsforthe sustainablemanagementoftheMontado;d)ownmanagementand futureperspectives;e)theroleoftheCAP,presentorientationsand proposalsforrequiredchanges.

Thefarmershavebeeninterviewedintheirhomes,attheirfarm oralocationtheyhaveselected,allbythesameinterviewer.The interviewslastedbetween1h30and3h,andwererecorded.Afull transcriptionofeachinterviewwasmade.

Theinterview’stranscriptionshavebeenanalyzedfollowinga discourseanalysisapproach(Antaki2008;Hyvarinen2008). Dis-courseanalysisaimstoreveal,andsometimesunmask,thepersonal meaning-makingof thosebeingfocused on, throughthe analy-sis of what is explicitly said but also of what remains unsaid. In the present case, the analysis wasbased on a careful read-ingandinterpretationoftheinterviewtranscriptions,inorderto extractthecentralthemesandrepertoiresinthefarmers’discourse, andthustouncovertheunderlyingdimensionsamongwhichthe intervieweemadesenseofhis/herexperiencesandactions. Dis-courseanalysiscanbeusedindifferentperspectives.Hereweused theperspectiveofconsideringdiscourseasaframeofreference: anorganizedsetofsocialrepresentations,throughwhichpeople understand,explainandarticulatethecomplexsocialandphysical environmentinwhichtheyareimmersed(Hermansetal.,2012).

Insightsfromsocialsciencestheoryhavesupportedthis analy-sis,astheaimwastolookparticularlyintothesocialcomponentof farmmanagementandunderstandfarmers’representations,values andmotivations,aswellastheirinteractionwiththeir manage-mentpractices (Godinhoet al.,2014,2016).Theactor network theory(ATN)hasbeenparticularlysupportive,asitemphasizesand considersallsurroundingfactors—recognizingthatnooneacts alone.ATNprovidestheconceptualframeworkforunderstanding howfarmsareorganizedandhowdecisionsaremade, consider-ingtheextremelyheterogeneouscombinationofnatural,technical, economicandsocialelementsandinteractionsthatcomposeafarm anditssurroundingcontext(EgonandAlroe2012).ATN’sstrength isthatitfocusesonrelationshipsandprovidesageneralandopen understandingof the relationalstructure of farm systems,

tak-ingintoconsiderationbothinternalandexternalfactors(Milestad etal.,2012).In thiscase, lookingatfarmers’representationsas driversoftheirmanagementoptions,ATNhassupportedinsights intothecontextandcomplexinteractions,whichmayinfluence theserepresentations.

3. Results:contradictionsinfarmers’statedvaluesand actions

Withregardtothefarmers’typology,theintervieweesgenerally agreedwiththetypesdescribed,andalsowiththetypetheywere includedin.Somesaidtheycorrespondedtothetypeinwhichthey wereincluded,butcombinedwithanotherone.Farmersclassified asproductivist livestockfarmerstendtostatethatallMontado farmerstheyknowareinthesametype,andthatintensification istheonlywaytomaintainaMontadofarm.However,somefound itdifficulttoplaceotherfarmerstheyknowintoonesingle cate-goryandclaimedthatineachfarmer’sstrategythereisanelement ofeachofthethreetypes.

Onehighlyrevealingaspectisthattheperceptionofthe Mon-tadoisverymuchconsensual,withthedeterminingcharacteristic beingthetrees.Formany,thefirstreactionto“Howwouldyou definetheMontado?”was“theMontadoisthetrees”or“the Mon-tadoistrees”,or“aforest”,“aMediterraneanforest”.Somemention thetypeoftrees,corkandholmoaks(QuercussuberandQuercus rotundifolia),aswellascorkproduction.Oneevensays“The Mon-tadoiscork”.Onlyafewtalkhereaboutthegrazinganimals,and whentheydo,theyrefertoaforestsystemwithmultiple associ-atedcomponents,theanimalsbeingtheIberianpigorsheep.Five ofthesefarmersalsorefertotheMontadoasheritage,anidentity landscape,andaniconicvalueofAlentejoandevenofthecountry asawhole.Butbesidesthesefive,othersreferheretothesocietal obligationtomaintaintheMontado:“weneedtokeepit,asmuch aspossible,itisourrole”,or“weallhavetopreserveit”,“wehave theobligationtopreserveit”,“wecannotletitdie”.TheMontadois thusseenasaforest-basedsystem,closelylinkedtothe produc-tionofcorkandthecorrespondingincomegeneration,andalsoas auniqueandvaluableheritage.

Inlinewiththisrepresentation,clearlycentredinthetrees,the sustainablemanagementoftheMontadoisclearlydefinedas man-agementwherethemaintenanceofthetreesisacentralgoal.As oneofthefarmersexpressed, “thecrucialfactoristounderstand the tree”, and another: “thegoal istotake care of andmaintain thetrees”.Manyrefertotheneedtosafeguardthetreecoverby avoidingdeepploughing,plantingnewtreesandprovidingthem withwater duringtheinitialsummers,andalsoavoidingshrub encroachment,whichisseenascompetingforresourceswiththe trees.Thus,acleanMontado,withnoshrubintheundercover,is associatedwithasustainableMontado.Furthermore,thenotionof abalanceduseoftheexistingresources,throughcontinuous adap-tivemanagement,ismuchpresent.Mostofthoseinterviewedrefer totheneedtomaintainabalancebetweentheconditionsofthe Montado,andthusitscarryingcapacity,andtheinterventionsfor pastureimprovement,ontheonehand,andgrazingintensityand breedontheother.Afewfarmersrefertotheneedtofertilizeand improvethepasturessothatmoreplantmaterialisavailablefor livestock,butalsosothatthetreesarefertilized.Othersdefendlow livestockdensities,andgenerallyavoidingcattle,orevenmanaging thetreeswithoutlivestock.Inthislastcase,suchopinionisnotin thesenseoffarmmanagementwithnootheractivitybesidesthe forest;itismoreinthesenseofsettingasidehigh-qualityMontado areasasconservationpatches,preservedasforestsystems,within largerfarmunitswheremostoftheareaisdedicatedtoagricultural production,beitlivestockgrazingorother.

Furthermore,whenaskedaboutthesustainablemanagementof theMontado,therearefrequentreferencestounbalanced manage-mentstrategies,whereseriousmistakeshavebeenmade(excessive grazingpressureorexcessivelydeepploughing),inthepast.Several farmerscitetheformerlackofknowledgeandbeliefin rationaliza-tionandmechanizationasthemaincause.Thesearereferences toaperiod aftertheRevolutionin the‘70sand theconsequent cooperativemanagementofmanylargeestatesforafewyears, fol-lowedbytheintegrationofPortugalintotheEuropeanUnion.The previousperiod,uptothe1970s,isseenasaperiodofwise manage-ment,wherecattlewouldnotbeacceptedintheMontado,shrub controlwasmainlyundertakenmanuallyandsoilploughingwith heavymachinerywasstillaseldompractice.Asforthepresent, manyclaimthereisaneedformuchmoretrainingand informa-tioninordertoachievemoresustainablemanagement,butsome alsoclaimthereisnowgenerallybetterinformationandeducation forfarmers,andthereforewisermanagementtoday.

Then,whenaskedabouttheirpersonalmanagementofthe Mon-tadotoday,thefocusismuchdifferent.Mostrepliesdealwiththe livestock:grazingmanagement,theimprovementofpastures, live-stockcomposition,feedingrequirementsandworryingcostslinked tothepurchaseoffodderoutsidethefarm.Thedominantlivestock iscattle.Onlythreeofthefifteenfarmershaveonlysheepas live-stockintheirMontadofarm.Onehassheepformilk,whiletheother twohavesheepformeat.Alltheremainingfarmshavecattle,of dif-ferentbreeds,oftenmorethanonebreed(pureormixed),andin somecasescombinedwithsheep.Onefarmerhasdairycows,but alsoextensivemeatcattleinthesamefarmunit.

Thecapacity ofthepasturestofeedtheanimalsis acentral concern.Theperiodthelivestockremainsonthepasturesandthe needtoprovideextrafodderattheendofthedryseasonisthe mainissue.Thecapacitytoproducethisextrafodderinotherareas insidethefarm,andthereforetobeindependentfromimported fodder,isageneralgoal.Thosewhodonothavethiscapacityare concernedabouttheirexternaldependencyand,hence,their vul-nerabilityinthedryyears.Therefore,theyaimtoincreasetheir fodderproductioncapacity,forexamplebyincreasingirrigation areas(throughpivots).Someofthefarmersrefertopracticesfor improvingthepastures.Having different paddocksand moving theanimalsfrequentlyinordertomakeabetteruseofthe pas-turesisalsomentioned.Yetonceagainthecentralconcernisthe mostrationalandeconomicalwayoffeedingtheanimals,andnot treecoversurvival.Severalfarmersmentionedeconomic rational-ityandeconomicsustainabilityastheirmanagementgoal,oreven astheonlypossiblegoal:“environmentalsustainabilityisreally won-derfulbutifthereisnoeconomicsustainabilitythenthereisnofuture”, or“onlywhenyouhaveanotherincomesourceandtheMontadois managedasanamenitycanthebalanceofthewholesystembethe priority”.Inthisway,theyjustifytheneedtomaintaincattleinthe Montado:withthepresentCAPconstructionandthehighcoupled paymentsforcattle,maintainingintensivecattleproductionisseen astheobviouseconomicrationality.

Generally,inresponsetoquestionsabouttheircurrent manage-ment,thereisnoreferencetothetreecover.Thisdiscrepancyin relationtothepreviousstatementsabouttheMontado’sdefinition andsustainablemanagementishighlysignificant.Onefarmer,who statedthatthesustainablemanagementoftheMontadorelieson thecarefulunderstandingoftreebehaviouranddetailedattention tocorkproductionovertime,saysofhisownmanagement:“cattle istheabsolutepriority;corkandforestryproductsaresub-productsof theMontado”.Sheepproducersmentionthattheychoosethistype ofanimalbecausetheylikeitmostorbecauseofexpectationsof highincome(inthecaseofdairysheep),butalsobecauseoftheir betteradaptationtothemaintenanceofthetreecover.

Amongthosewhohavecattle,onlytwofarmersrefertotree covermaintenanceasacentralissue.Theycorrespondtothe

minor-itywithinthetypologyproducedinthefirststepoftheanalysis: multifunctionalfarmers.Theyaretheoneclassifiedasa multifunc-tionalmanagerand anotherclassifiedasanentrepreneurcattle farmerwhoseeshimselfmoreasamultifunctionalmanager.They promotemanagementpracticeswherethebalanceandrenewalof thetreecoverisonerequirement,boththroughlowgrazing densi-ties,theproductionoffodderinsidethefarm,andthepreservation ofMontadoareasfromcattlegrazing.

Infact,thesetwofarmerstendtoseparatecattleproduction fromtheMontado,focusingonothergrazingspecies−sheepand Iberianpigs−intheMontadoandkeepingthecattlemostlyoutside orinselectedareas,withverylowdensity.Amongtheremaining cattleproducers,somealsomentionthattheykeepcertain Mon-tadoareasclearfromgrazingorhaveevenplantednewtreesto increasedensity.However,thesearefarfromthecentral manage-mentconcernsandsomehowrevealatrendforconsideringthe Montadotobeingoodstandandhavehightreedensity,asa resid-ualpartofthefarm.Onefarmer,forinstance,referstohisplantation ofnewtreesasanexpressionofhiscarefortheMontado;yethe hasplanted40outofatotalof700ha.

Thisreducedreferencetothetreesismoststrikingconsidering thatcorkproduction,whosequantityandqualitydependsdirectly onthegoodconditionofthetreecover,isinmanycasesconsidered asanimportantincomeandpartofthelong-termmanagement strategyofthefarm,asexpressedinthefirststepinquirytothese farmers.Corkisonlyextractedeverynineyearsfromeachsingle treeandnormallyalltreesinafarmunitareharvestedinoneortwo differentyearssothattherequiredworkinvestmentandincome aregathered.Therefore,theincomefromcorkissignificantbut notonaregularyearbasis,andwasmentionedintheinterviews ascoveringtheneededlargeinvestmentstocontinuethefarm’s livestockproduction,aswellasmaintainirrigationinfrastructures, buildingsandfences.

InrelationtotheCAP,thejudgementisverysimilaramongall farmers:theCAPpaymentsdrivetheintensificationofthe Mon-tadoandexcessivecattledensityintheundercover,andaresolely responsibleforthistrend.ThoseinterviewedrefertotheCAP influ-enceasakindoffatality:“theincentiveforcattleproductionisclearly damagingtheMontadoandalotofwhatwearedoingisnonsense, butthereisnootherpossibility;aslongascowsareprofitable,wewill continuetohavecows”;“ifwedonotconsiderwhatgivesusaregular yearlyincome,thenwecannotsurvive”.AndtheCAPmechanisms areseenasleadingthefarmerstofocusonlyonincome:“alotof farmersonlyaimtotakethehighestincomeoutoftheMontado,and thereforetheyhavecows;theydonotevenlikecowsortreatthem well,theyjustwanttoearnmoney”;“Montadoownersknowtoolittle anddonotknowwhatisbest;theylivetoofas,andneedtoobtaina lotofmoneyfromtheirfarms”.

Only a few of the interviewed farmers mention the agri-environmental schemes as relevant payments for them. For instance,concerningthesupportforautochthonouscattlebreeds, whicharelighterandlessdemandingandthereforeless impact-ingontheMontado,theagri-environmentalpaymentisconsidered “ridiculous”inrelationto thelowerincome generated bythese breedsinthemarket.Themajorityoffarmersrefersolelytothefirst pillarpayments.Askedabouthowtheirpracticeswouldchangeif theCAPpaymentstheyreceiveweremaintainedbutnotcoupled tothecattleheads,thereactionisalsoquitehomogeneous:the cattledensitywouldbesubstantiallyreducedandcattlewouldbe progressivelyreplacedbysheep,atleastpartially.Afewfarmers defendtheircurrentpracticebystatingtheywouldnotchange any-thingintheirmanagement.Butwhenaskedaboutwhattheythink wouldshouldbechangedintheCAP,theyclearlyrefertoa replace-mentofthepresentpaymentmechanismsbyothersthataremore respectfulofthewholeMontadosystemandthebalancebetween grazingactivitiesandthetreecover.

Itisobviousthat,asinmostotherfarmsystemsinEurope,a sig-nificantpartofthefarms’incomeisdependentonCAPpayments andthesystemisbuiltwiththesepaymentsasastructuringfactor. Thisisnotunique.Butwhatisparticularinthecaseofthe Mon-tadoisthatallfarmersinterviewedacknowledgemainlynegative impactsresultingfromthemannerinwhichtheCAPfunctionsand wouldoptforotherpracticesandproductsiftheschemeswere structureddifferently.

4. Discussion:farmersinadifficultquandary

Thereis a fundamental conflict emerging fromthe analysis, betweentherepresentationthefarmershaveoftheMontado,and theirrepresentationofwhattheirownMontadomanagementis about.TherepresentationoftheMontadoisstronglyfocusedon thetreecomponent,ontheMontadosystemasaforestrysystem withwhichcattlegrazingisassociated.Alltheintervieweesclearly feelthatthesustainabilityoftheMontadoiscentredonthe preser-vationofthetrees.Nevertheless,currentmanagementispresented astotallycentredonlivestockmanagementandtheeconomic ratio-nalebehindthebalancebetweenlivestockintensityand fodder availability.Thetreesseemtohavedisappearedfromthefarmers thoughtsamidthesemanagementconcerns.Thisisthecaseeven though,inthefirststepenquiry,manymentionedthecorkincome asasignificantpartoftheeconomicrationalityofthefarm.In live-stockgrazingsystems,efficientstockfeedmanagementisalways criticaltoafarm’ssuccess(Nuthall2012).Inthecaseofthe Mon-tado,withthelimitedproductivecapacityofAlentejosoils,together withthecharacteristicinter-annualfluctuationsofthe Mediter-raneanclimate,adaptiveandefficientlivestockmanagementisa crucialfactorinavoidingpotentialovergrazingrisks(Sales-Baptista etal.,2015).Suchmanagementiscomplex,naturallyraising con-cernswithrespecttofarmers’strategymaking.Butwhatisstriking inthediscourseofthefarmersinterviewedisthatthemaintenance ofthetreesisabsentfromthemanagementdescription,whenit isclearlyknownbyallofthemthatgrazingpressureisaffecting bothpastureproductivityandthetrees’standandregeneration, andwhenatthesametimemanyofthemconsidercorktobea significantincomesourcefortheirfarm.

Itseemsthatthereisalong-termview,whichincludesthetrees andtheoverallbalanceofthesystemasaforestrysystemanda producerofcork,oftenconnectedwiththesenseofheritageand identity−theMontadoassomethingvaluablethathasbeenpassed downandwhichthefarmershavearesponsibilitytomaintainfor thefuture.Thenthereisashort-termview,whichisconveniently separatedfromthefirstandinwhichthecentralissueisthe eco-nomicrationalityandtheneedtoobtainasmuchincomefromthe livestockaspossible,takingintoconsideration theconstrainsof thefarm.Thesetwooutlooksareindirectconflictwitheachother. Thisconflictishardlyacknowledgedbythefarmers−theyreflect onthecontradictionsandthetensionscreatedyetpresentthem asinevitabilitieswhicharecurrentlyoutoftheircontrol,thereby keepingpossibleconflictoutsidetheirdecision-makingsphere.In thisway,theyrationalizetheshort-termstrategytheyare follow-ing−whichisonlyaneconomicrationalityandonlyshortterm,on ayearlybasis.Theseparatereferencesandrepresentationsarising fromthetwosetsofquestionsleadsustoformulatethehypothesis that,byseparatingthetwocontradictoryviewsontheMontado inthisway,thefarmersprotectthemselvesfromaconstantinner conflictthatwouldbedifficulttodealwithonadailybasis.

Asdescribedinliterature(Schiereetal.,2012;Milestadetal., 2012;NoeandAlroe2010),thestrategyofthefarmerisnormally toachievecoherenceandclosureinhis/herfarm,inthefaceofthe existingcontextandconsideringthefarmsystemandthenetworks he/sheispartof.Withoutbeingformulatedthisway,thestrategy

offarmersisoftenguidedbyresiliencethinking,whichisgrounded inknowledgeandintuitionandsupportsfarmssurvival(Darnhofer 2014;Nuthall2012).Butthecentralissueshereseemtoberemoved fromthefarmsystemandplacedonthenetworks,asifthe manage-mentstrategiesweredefinedbyfactorswhicharetotallyoutside thefarm.Thus,whatourempiricalevidenceshowsisthatthefocus offarmmanagementgoalsintheMontadoatpresentisgradually movingfrommaintainingcoherencebetweeninternalprocesses onthefarmandreproduction,thussecuringlong-termresilience, tomanagingrelationswithexternalactors,systems,inputs, rev-enuesandfinancial partners.In this way,knowledgeaboutthe Montado’ssensitivebalance,passeddownfromonegenerationto thenextwithinfamiliesandnetworksoffarmers,and establish-inggroundsformanagementintuition(Nuthall2012;Pinto-Correia andGodinho2013),issetaside.Itisnotonlythepresent manage-mentoptionswhicharebiasedbythestrengthofexternalfactors, itisalsothefarmers’comprehensiveknowledgefoundationwhich iseroded.Theresiliencethinkingwhichhasmadethemaintenance oftheMontadopossibleuntilrecently,andwhichisexpressedin farmers’representationoftheMontadoanditssustainability,is keptmerelyasakindofutopia,uselessinpractice.

Anincreasinglydramaticresultofthis processrelatestothe system’sresiliencelimits:beyondacriticalthreshold,treecover regeneration and recovery of the soil becomes impossible and thelong-termdegradationofthebiophysicalconditionsbecomes unavoidable(Schermeretal.,2016;Godinhoetal.,2014,2016).As aresult,thefuturepossibleuseoftheseformerMontadoareasis highlyuncertain.

ThestructureoftheCAP’s1stPillarpaymentsschemes, com-binedwiththeweaknessofthe2ndPillar,arecentraltothisprocess. CAPhasaccumulatedanumberofinternalcontradictionsinrecent years(Beaufoy2014),andalthoughthediscoursehaschanged,the practiceofpolicyimplementationremains focusedonintensive farmingsystems.Previousliteraturehasshowedhowthestructure ofCAPpaymentsappliedtolivestockproductionintheMontado iscreatinginstabilityforfarmers’incomeandaffecting manage-mentstrategies(Godinhoetal.,2014,2016;Fragosoetal.,2011). Thefundamental roleofinstitutionsand policiesinsecuringor erodingfarmsystemsandtheirvaluableoutcomes,besides pro-duction,iswellknownanddescribedinliterature(Schermeretal., 2016).Andinthiscasethereisaclearimpactonthemanagement optionstakenbyfarmers,eveniftheseleadtoadecreaseinthe Montado’sresiliencecapacityandadeclineinwhatthesame farm-ersconsidertobeimportantvalues(heritage,foreststability,cork production).Whatourempiricalmaterialalsoshowsisthatthere isanunderlyingtensiondrivenbythepresentpolicytoolsaffecting theMontado,whichiskeptnon-explicitinfarmers’everyday man-agementpractices.Inordertocopewiththistension,farmersare envisagingtheiroptionsasexternaltothefarmsystemand reduc-ingtheresiliencethinkingwhichwasinherenttotheinternalfarm systemrationale.

5. Concludingremarks

Themostpowerfulpublicpolicyasregardsfarmmanagement inEuropeistheCAP.Initscurrentformatandthewayithasbeen appliedinPortugal,itisdrivingthemanagementoftheMontado systemintospecializedmeatcattleproduction−thuserodingthe complexsustainabilityfoundationswhichtheMontadohas main-taineduntilrecentlyandseverelyaffectingitslong-termresilience. The decay of theMontado area, recorded every yearsince the beginningofthenineties,atteststothisprocess.Itisalso demon-stratingthatthecriticalthreshold,beyondwhichradicalchanges inthissystemtakeplaceandregenerationoftheMontadoismade impossible,hasbeenexceededinmanyplaces.Farmersretaintheir

knowledgeandintuitiononthesensitivityofthesystem,aswell asasenseofheritage,whichcouldformthebasisforthe contin-uedbalancedmanagementofthissystem.Nevertheless,atpresent theyareexternalizingtheMontadomanagementdriversand pur-suingoptionstheydefendwithshort-termeconomicreasoning. Theyarenotacknowledgingtheirresponsibilityforthetrends reg-isteredandthedecayoftheMontadoasasystem.Theyholdup theMontadoasanimageofthepast,orofadesirablefuture−to bemaintainedinlimitedconservationareas,asakindofnature andculturalreserve.Consequently,theydonotsearchfor alterna-tiveandadaptiveoptions.ThemaintenanceoftheMontadoasa forestrysystemisbeingreducedtothepreservationofsmalland well-limitedpatchesoneachfarm.Ifpolicypracticeanddiscourse does not move towards a specific approach for Mediterranean silvo-pastoralsystems,thepreservationoftheMontadoaswestill observeittodayisalreadyseverelythreatenedintheshortterm. Acknowledgments

Thisworkwaspartiallyfunded bytheproject FCT-PTDC/CS-GEO/110944/2009. Carla Azeda holds an FCT doctoral grant (SFRH/BD/94966/2013). Thisworkwas alsofunded by National FundsthroughtheFCT−FoundationforScienceandTechnology undertheProjectUID/AGR/00115/2013.

References

Acácio,V.,Holmgren,M.,2012.PathwaysforresilienceinMediterraneancorkoak landuse.systems.Ann.For.Sci.71,5–13.

Almeida,M.,Guerra,C.,Pinto-Correia,T.,2013.Unfoldingrelationsbetweenland coverandfarmmanagement:highnaturevalueassessmentincomplex silvo-Pastoralsystems.GeografiskTidsskrift-DanishJ.Geogr.113(2),97–108,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00167223.2013.848611,Routledge.

Almeida,M.,Azeda,C.,Guiomar,N.,Pinto-Correi,T.,2015.Theeffectsofgrazing managementinmontadofragmentationandheterogeneity.Agrofor.Syst.,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10457-014-9778-2.

Antaki,C.,2008.Discourseanalysisandconversationanalysis.In:Alasuutari,P., Bickman,L.,Brannen,J.(Eds.),TheSAGEHandbookofSocialResearchMethods. Sage,pp.431–446.

Aronson,J.,Santos-Pereira,J.,Pausas,J.G.,2009.Generalintroduction.In:Aronson, J.,Santos-Pereira,J.,Pausas,J.G.(Eds.),CorkOakWoodlandsontheEdge: Ecology,AdaptiveManagement,andRestoration.IslandPress,Washington,DC, pp.1–10.

Barroso,F.,Pinto-Correia,T.,2014.Landmanagers’heterogeneityin mediterraneanlandscapes−consistenciesandcontradictionsbetween attitudesandbehaviors.J.LandscapeEcol.7(1),45–74http://mendelu. vedeckecasopisy.cz/publicFiles/00671.pdf.

Beaufoy,G.,2014.Woodpasturesandthecommonagriculturalpolicy.In:Hartel, T.,Plieninger,T.(Eds.),EuropeanWoodPasturesinTransition.A

Socio-EcologicalAproach.Routledge,Oxon,pp.273–281.

Cochet,Hubert,2012.ThesystemeAgraireconceptinfrancophonepeasant studies.Geoforum43(1),128–136,http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011. 04.002(ElsevierLtd).

Costa,A.,Madeira,M.,LimaSantos,J.,Oliveira,A.,2011.Changeanddynamicsin mediterraneanevergreenoakWoodlandslandscapesofSouthwesternIberian Peninsula.LandscapeUrbanPlann.102(3),164–176,http://dx.doi.org/10. 1016/j.landurbplan.2011.04.002(ElsevierB.V.).

Darnhofer,I.,Gibbon,D.,Dedieu,B.,2012.In:Sringer(Ed.),FarmingSystems Researchintothe21StCentury:TheNewDynamic.

Darnhofer,I.,2014.Resilienceandwhyitmattersforfarmmanagement.Eur.Rev. Agric.Econ.41(3),461–484,http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/erae/jbu012. Ferraz-de-Oliveira,MariaIsabel,Azeda,Carla,Pinto-Correia,Teresa,2016.

Managementofmontadosanddehesasforhighnaturevalue:an

interdisciplinarypathway.Agrofor.Syst.90(1),1–6,http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ s10457-016-9900-8(SpringerNetherlands).

Fragoso,R.,Marques,C.,Lucas,M.R.,Martins,M.B.,Jorge,R.,2011.Theeconomic effectsofcommonagriculturalpolicyonmediterraneanmontado/dehesa ecosystem.J.PolicyModel.33(2),311–327,http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. jpolmod.2010.12.007(TheSocietyforPolicyModeling).

Godinho,S.,Gil,A.,Guiomar,N.,Neves,N.,Pinto-Correia,T.,2014.Aremote sensing-BasedapproachtoestimatingmontadocanopydensityusingtheFCD model:acontributiontoidentifyingHNVfarmlandsinsouthernPortugal. Agrofor.Syst.,http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10457-014-9769-3.

Godinho,S.,Guiomar,N.,Machado,R.,Santos,P.,Sá-Sousa,P.,Fernandes,J.P., Neves,N.,Pinto-Correia,T.,2016.Assessmentofenvironment,land

management,andspatialvariablesonrecentchangesinmontadolandcoverin southernPortugal.Agrofor.Syst.90(1),177–192,http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ s10457-014-9757-7.

Guerra,C.,Pinto-Correia,T.,Metzger,M.J.,2014.Mappingsoilerosionprevention usinganecosystemservicemodelingframeworkforintegratedland managementandpolicy.Ecosystems17(5),878–889,http://dx.doi.org/10. 1007/s10021-014-9766-4.

Guerra,C.A.,Metzger,MarcJ.,Maes,J.,Pinto-Correia,T.,2015.Policyimpactson regulatingecosystemservices:lookingattheimplicationsof60yearsof landscapechangeonsoilerosionpreventioninamediterraneansilvo-Pastoral system.LandscapeEcol.,http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10980-015-0241-1

(SpringerNetherlands).

Hermans,F.,Kok,K.,Beers,P.J.,Veldkamp,T.,2012.Assessingsustainability perspectivesinruralinnovationprojectsusingQ-methodology.Soc.Ruralis52 (1),70–91,http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2011.00554.x.

Herzfeld,T.,Jongeneel,R.,2012.Whydofarmersbehaveastheydo? understandingcompliancewithrural,agricultural,andfoodattribute standards.LandUsePolicy29(1),250–260,http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. landusepol.2011.06.014(ElsevierLtd.).

Hyvarinen,M.,2008.Analysingnarrativesandstorytelling.In:Alasuutari,P., Bickman,L.,Brannen,J.(Eds.),TheSAGEHandbookofSocialResearchMethods. Sage,pp.447–460.

Liu,Yaolin,Feng,Yuhao,Zhao,Zhe,Zhang,Qianwen,Su,Shiliang,2016. SocioeconomicDriversofForestLossandFragmentation:AComparison betweenDifferentLandUsePlanningSchemesandPolicyImplications.Land UsePolicy,58–68,http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.01.016

(ElsevierLtd.).

Milestad,R.,Dedieu,B.,Darnhofer,I.,Bellon,S.,2012.FarmsandFarmersFacing change:TheAdaptiveApproach.In:Springer(Ed.),FarmingSystemsResearch intothe21stCentury:TheNewDynamic.,pp.365–385,http://dx.doi.org/10. 1007/978-94-007-4503-216.

Moreno,G.,Franca,A.,Pinto-Correia,T.,Godinho,S.,2014.Multifunctionalityand dynamicsofsilvopastoralsystems.OptionsMediterr.A109,421–436.

Noe,E.,Alrøe,H.F.,Langvad,A.M.S.,2008.Apolyocularframeworkforresearchon multifunctionalfarmingandruraldevelopment.Soc.Ruralis48(1),1–15,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.2008.00451.x.

Nuthall,P.L.,2012.Theintuitiveworldoffarmers−thecaseofgrazing managementsystemsandexperts.Agric.Syst.107,65–73,http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.agsy.2011.11.006(ElsevierLtd.).

Pinto-Correia,T.,Godinho,S.,2013.Agricultureinmediterraneaneurope:between oldandnewparadigms.In:AgricultureinMediterraneanEurope:BetweenOld andNewParadigms,19:75–90.ResearchinRuralSociologyandDevelopment. EmeraldGroupPublishing,Bingley, http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/S1057-1922(2013)0000019006.

Pinto-Correia,T.,Ribeiro,N.,Sá-Sousa,P.,2011.Introducingthemontado,thecork andholmoakagroforestrysystemofsouthernPortugal.Agrofor.Syst.82(2), 99–104,http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10457-011-9388-1.

Pinto-Correia,T.,1993.Threatenedlandscapeinalentejo:Portugal:the‘Montado’ andother‘Agro-Silvo-Pastoral’systems.LandscapeUrbanPlann.24,43–48.

Sales-Baptista,Elvira,D’Abreu,ManuelCancela,Ferraz-de-Oliveira,MariaIsabel, 2015.Overgrazinginthemontado?theneedformonitoringgrazingpressure atpaddockscale.AgroforestrySystems,57–68,http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ s10457-014-9785-3,SpringerNetherlands.

Schermer,Markus,Darnhofer,Ika,Daugstad,Karoline,Gabillet,Marine,Lavorel, Sandra,Steinbacher,Melanie,2016.Institutionalimpactsontheresilienceof mountaingrasslands:ananalysisbasedonthreeeuropeancasestudies.Land UsePolicy52,382–391,http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.12.009

(ElsevierLtd.).

Schiere,J.B.,Darnhofer,I.,Darnhofer,M.,2012.DynamicsinFarmingSystems:Of ChangesandChoices.pdf.In:Springer(Ed.),FarmingSystemsResearchinto 21thCentury:TheNewDynamic.,pp.337–363,http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/ 978-94-007-4503-215.