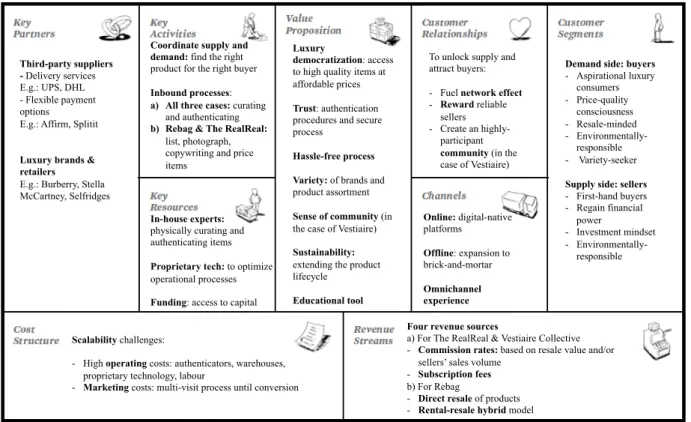

A first-hand experience for a second-hand product : the success of online luxury resellers

Texto

Imagem

Documentos relacionados

Leaves, branches and berries of coffee plants with symptoms of blister spot, anthracnose and dieback were collected, in different cities in the southern of Minas Gerais state

ESTUDO DO RETIFICADOR HÍBRIDO MULTIPULSOS DE ELEVADO FATOR DE POTÊNCIA E REDUZIDA DISTORÇÃO HARMÔNICA DE CORRENTE NO CONTEXTO DA QUALIDADE DA ENERGIA ELÉTRICA.. ELCIO PARREIRA

Por outro lado, importa relembrar que a aposta no reforço e extensão da escolarização das populações não pode fazer esquecer a inutilidade e mesmo prejuízo que decorrem

Quando foram comparados os adolescentes do sexo mas- culino com os do sexo feminino, por idade, de acordo com os pontos de corte internacionais definidos para o IMC, foram

development mechanism can be a learning process for mobilizing the local population, and increasing community problem-solving capacities, volunteerism, governance and

Na terceira bateria de testes, realizados em dezembro de 2015, foi feita a secagem de sementes de mamão (Caricapapaya L.), objetivando-se comparar o tempo de secagem

After a theoretical incursion on the practice of discourse borrowing in advertising, we will concentrate on the analysis of advertising strategies which draw on (a) medicine

Tabela 3-9: Número de observações, valores máximos, mínimos, média ± desvio padrão e coeficiente de variação para as provas de mobilidade individual, coloração