Objective: To analyze the relationship between habits and attitudes of mothers and the types of milk ofered to their children in their irst two years of life.

Methods: Retrospective study including 773 interviews of mothers from 11 Brazilian cities with children under 2 years of age. Interviews were conducted in 11 cities of Brazil. The following factors were analyzed: breastfeeding method planned during pregnancy and the method actually applied after birth; type(s) of milk(s) used on the day of the interview and earlier; age at which the child was introduced to whole milk; and source of advice used to choose a certain type of milk.

Results: Breast milk was ofered to 81.7% of infants during their irst six months of life, to 52.2% of infants during their second semester (p<0.001) and to 32.9% of infants during their second year of life (p<0.001). In contrast, cow’s milk consumption increased from 31.1 to 83.8% (p<0.001) and 98.7% (p=0.05), respectively, for these three age groups. Infant (15.0%) and follow-on (also known as toddler’s) (2.3%) formulas were used by a much smaller number of infants than whole cow’s milk. Most mothers were not prescribed whole cow’s milk. Pediatricians were the health care professionals who most often recommended infant formulas. Conclusions: Rates of breastfeeding in Brazil remain below recommended levels. Brazilian mothers often decide to feed their infants with whole cow’s milk on their own initiative. The use of infant formulas after weaning is still too low.

Keywords: Breast feeding; Infant formula; Dried whole milk; Infant; Artiicial feeding; Weaning.

Objetivo: Analisar a relação entre hábitos e atitudes de mães com os tipos de leite oferecidos para seus ilhos nos dois primeiros anos de vida.

Métodos: Estudo retrospectivo incluindo 773 entrevistas de mães de 11 cidades brasileiras com filhos com até 2 anos de idade. Foram analisadas as seguintes informações: tipo de aleitamento que planejava enquanto estava na gestação e o efetivamente realizado após o nascimento; tipo(s) de leite(s) utilizado(s) no dia da entrevista e anteriormente; idade de introdução do leite de vaca integral; e origem das recomendações para usar determinado tipo de leite. Resultados: O leite materno era oferecido para 81,7% dos lactentes no primeiro semestre de vida, 52,2% no segundo semestre (p<0,001) e 32,9% no segundo ano de vida (p<0,001). Por sua vez, o consumo de leite de vaca integral aumentou de 31,1 para 83,8% (p<0,001) e 98,7% (p=0,05), respectivamente, nestas três faixas etárias. Fórmula de partida (15,0%) e de seguimento (2,3%) eram utilizadas por um número de lactentes muito menor em relação aos que recebiam leite de vaca integral. A maioria das mães não recebeu prescrição de leite de vaca integral. Os pediatras foram os proissionais da área da saúde que mais frequentemente recomendaram fórmula infantil.

Conclusão: As taxas de aleitamento natural no Brasil continuam abaixo das recomendações. As mães brasileiras, com frequência, decidem oferecer leite de vaca integral por iniciativa própria. É muito baixa a utilização de fórmula infantil quando o aleitamento natural é interrompido. Palavras‑chave: Aleitamento materno;Fórmulas infantis; Leite em pó integral; Lactente; Alimentação artiicial; Desmame.

ABSTRACT

RESUMO

*Corresponding author. E-mail: maurobmorais@gmail.com (M.B. Morais). aUniversidade Federal de São Paulo (Unifesp), São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

bInstitute for Children at the School of Medicine of the Universidade de São Paulo (USP), São Paulo, SP, Brazil. cDanone Early Life, The Netherlands.

dDanone Early Life Nutrition, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

ePediatric Allergy, Immunology and Rheumatology class at the Escola Paulista de Medicina, Unifesp, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF MOTHERS OF

INFANTS IN RELATION TO BREASTFEEDING AND

ARTIFICIAL FEEDING IN 11 BRAZILIAN CITIES

Hábitos e atitudes de mães de lactentes em relação

ao aleitamento natural e artificial em 11 cidades brasileiras

Mauro Batista de Morais

a,*, Ary Lopes Cardoso

b, Tamara Lazarini

c,

40

INTRODUCTION

he irst two years of life represent a critical period of growth and development for children. In the irst six months, exclusive natural breastfeeding is ideal. Natural breastfeeding is recom-mended until two years of age, with complementary feeding starting at the age of six months.1-5

In Brazil, actions aimed at encouraging exclusive nat-ural breastfeeding were improved during the early 1980s. A cross-sectional study conducted during the 2008 mass vac-cination campaign, involving 34,366 infants living in Brazilian state capitals, showed that 41.0% of children were exclusively fed by natural breastfeeding during the irst six months of life and that 59.0% of children were breastfed between 9 and 12 months of age. Another 1999 research study detected an increase in the median duration of exclusive natural breastfeed-ing from 23 to 54 days, as well as an increase in the median total breastfeeding duration from 296 to 342 days.6 In 2005,

the mothers of 179 infants who did not receive exclusive nat-ural breastfeeding reported that the feeding practices adopted were based on the experience of the mother herself and/or her family. Pediatrician recommendations and media information were respectively the second and third most common sources of information about breastfeeding.7 Only 12.0% of infants

under 6 months of age who were not breastfed received infant formula as a substitute to breast milk, while that number was 7.0% for infants over 6 months of age. Most infants were fed whole cow’s milk. he median age at which infants were introduced to artiicial feeding (i.e. bottle feeding) was three months,7 which was often performed inappropriately,7

con-irming other Brazilian studies8-10. In addition to insuicient

breastfeeding time duration, it was found that infant formu-las are not being used as substitutes for breastfeeding often enough, contrary to Brazilian Pediatric Society recomenda-tions.1 he Brazilian Ministry of Health2 warns that whole

cow’s milk should be avoided during the infant’s irst year of life, as it is poor in iron and may lead to overweight and fur-ther complications.

In this context, there is an increasing concern about the relationship between food and early life nutrition and the future development of chronic diseases such as diabe-tes mellitus, hypertension, and others.1,11-14 A systematic

review showed that long-term breastfeeding was associated with lower blood pressure, total cholesterol, prevalence of overweight, type 2 diabetes, and with having better intel-lectual development.11

In 2009, Danone Early Nutrition conducted market research in Brazil on feeding practices during the first years of life, akin to what is practiced in other countries since 2003. Upon the release of the survey results, the authors

of this article argued that a pediatric analysis of its data would be invaluable for providing input that could be used in campaigns to encourage healthier feeding prac-tices during infancy.

Considering that in Brazil there is very limited information on nutrition during the irst two years of life and its impor-tance for present and future health, this study was conducted in order to analyze the relationship between dietary habits, mothers’ attitudes and the types of milk ofered to their chil-dren in their irst two years of life.

METHOD

his retrospective study was carried out using information from a research database which was conducted with 773 moth-ers of children aged under 24 months living in 11 cities of the Northeast, Southeast, and South of Brazil. he research was based on a stratified convenience sample. The field-work occurred between February 2009 and February 2010. Information was collected in interviews conducted in the par-ticipants’ residences. he Synovate Research Institute (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) was responsible for executing the ield research and preparing the database.

As recruitment criteria, we selected mothers propor-tionally to the number of boys and girls and to the number of irst children at each participating city. he 773 moth-ers recruited resided in: São Paulo (n=193), Rio de Janeiro (n=192), Campinas (n=32), Ribeirão Preto (n=37), Santos (n=33), São José dos Campos (n=30), Salvador (n=44), Recife (n=44), Fortaleza (n=44), Curitiba (n=63), and Porto Alegre (n=63). According to deinitions set by the Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa (ABEP),15 53 (6.0%) respondents

belonged to socioeconomic class A, 283 (36.6%) respondents belonged to class B, 356 (46.0%) respondents belonged to class C, 81 (10.5%) respondents belonged to class D, and none belonged to class E.13

Information collected during interviews was compiled into tables, including children’s age, birth order, maternal education, and insertion in the labor market. Interviews lasted approxi-mately 50 minutes each. his study divided interview reports according to children’s age – irst semester, second semester and second year of life.

he following interview questions were used in this study: 1. Before your child was born, what feeding method did

you intend to use during their newborn period? 2. After childbirth, which feeding method did you

actu-ally use?

4. Which type(s) of milk(s) have you already fed your child? 5. At what age did your child began drinking whole cow’s

milk (in liquid or powder form)?

6. Who recommended the feeding method(s) or type(s) of milk(s) that you currently use?

Statistical analysis was carried out in the Stacalc mod-ule of the EpiInfo software (Center of Disease Control and Prevention - CDC, Atlanta, USA) for calculating chi-squared test values.

his project was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo Hospital (CEP 1006/11).

RESULTS

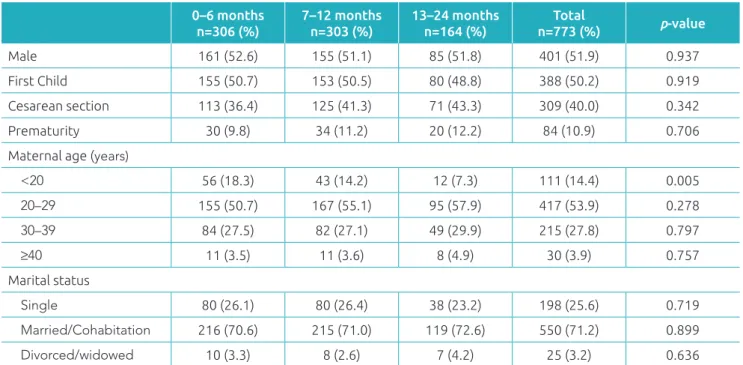

Table 1 presents the sex, birth order, type of delivery, preterm birth, maternal age, and marital status according to age. Statistical analysis showed no statistically signiicant diference for any of these variables, with the exception of mothers under 20 years of age, who breastfed less frequently during their infants’ sec-ond year of life.

Among mothers of infants up to 6 months of age, 94.8% (290/306) had intended to breastfeed their children before birth. hat number was 90.6% (275/303) for mothers of infants aged between 7 and 12 months, and 93.3% (153/164, p=0.152) for mothers of children aged between 13 and 24 months. In reality,

breast milk was used soon after birth by 298 (97.4%) of the 306 mothers of infants under 6 months of age, by 290 (95.7%) of mothers with children aged between 7 and 12 months, and by 158 (96.3%) of those with children aged between 13 and 24 months (p=0.525).

Table 2 shows the types of milk fed to children at the time of the survey and those they had already been fed since birth. A portion of the infants was observed to have received more than one type of milk at the time of the survey. Among the infants, 81.7% of them received natural feeding in the irst six months of life, a percentage that decreased progressively in the next six months and in the second year of life. he chi-squared test showed a statistically signiicant diference between the irst and second semesters of life (p<0.001) and between the second semester and the second year of life (p<0.001). here was a statistically signiicant increase in the consump-tion of whole cow’s milk, which rose from 31.1% in the irst semester of life to 83.8% (p<0.001) in the second semester, and to 98.7% (p=0.05) during the infants’ second year of life. he percentage of infants who received infant formula during their irst six months of life (15.0%) was lower than that of those who received whole cow’s milk (31.1%). In the second semester of life, formula use (12.5%) was much lower than the use of whole cow’s milk (83.8%). Almost all infants (97.1%; or 751/773) had been breastfed at some period since birth. Considering only the children in the second semester and sec-ond year of life, it was determined that 41.9% and 37.8%,

Table 1 Sex, birth order, type of delivery, prematurity, maternal age, and marital status, according to age group.

0–6 months n=306 (%)

7–12 months n=303 (%)

13–24 months n=164 (%)

Total

n=773 (%) p‑value

Male 161 (52.6) 155 (51.1) 85 (51.8) 401 (51.9) 0.937

First Child 155 (50.7) 153 (50.5) 80 (48.8) 388 (50.2) 0.919

Cesarean section 113 (36.4) 125 (41.3) 71 (43.3) 309 (40.0) 0.342

Prematurity 30 (9.8) 34 (11.2) 20 (12.2) 84 (10.9) 0.706

Maternal age (years)

<20 56 (18.3) 43 (14.2) 12 (7.3) 111 (14.4) 0.005

20–29 155 (50.7) 167 (55.1) 95 (57.9) 417 (53.9) 0.278

30–39 84 (27.5) 82 (27.1) 49 (29.9) 215 (27.8) 0.797

≥40 11 (3.5) 11 (3.6) 8 (4.9) 30 (3.9) 0.757

Marital status

Single 80 (26.1) 80 (26.4) 38 (23.2) 198 (25.6) 0.719

Married/Cohabitation 216 (70.6) 215 (71.0) 119 (72.6) 550 (71.2) 0.899

Divorced/widowed 10 (3.3) 8 (2.6) 7 (4.2) 25 (3.2) 0.636

42

respectively, received infant formula. In contrast, whole cow’s milk consumption had already been administered to 34.6% of infants under 6 months of age and to more than 94.0% of infants over 6 months of age.

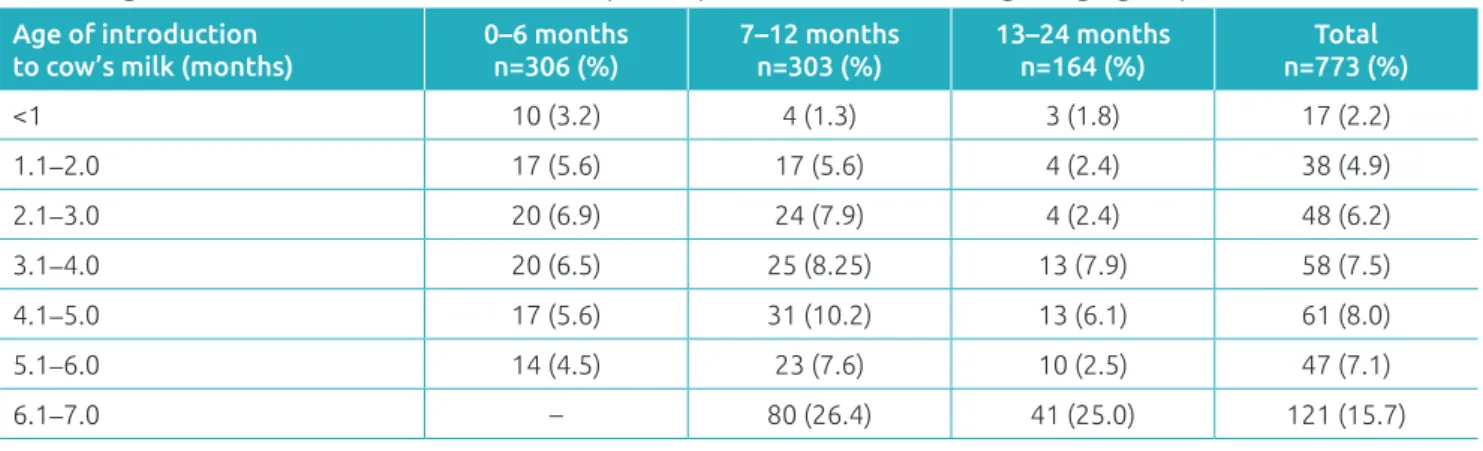

Table 3 shows the age at which infants were introduced to whole cow’s milk among the three age groups. Considering the total of those groups, a monthly progressive increase in the number of infants that began a diet of whole cow’s milk during the irst and ifth months of life was observed. However, it was also determined that in the sixth month there

is a major increase in introducing whole cow’s milk in the diet – approximately a quarter of all infants. Introduction to cow’s milk between 5.1 and 6.0 months (for children between 6 and 24 months of age, 5.4%; 33/609) was lower than introduction between 6.1 and 7.0 months (25.9%, 121/467), which represents a statistically signiicant difer-ence (p<0.001).

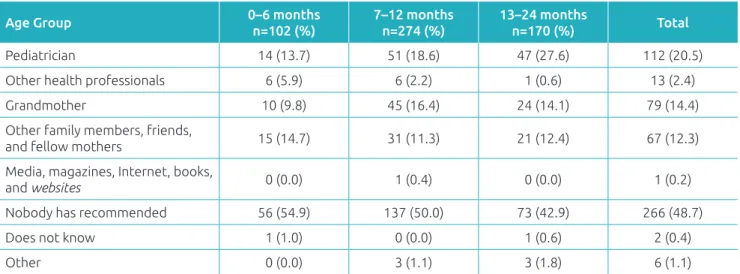

In Table 4, 54.9% of mothers of infants fewer than 6 months of age reported that they had not been instructed to use whole cow’s milk. 9.8% and 14.7% of the respondents

Table 3 Age of introduction to cow’s milk in liquid or powder form, according to age group.

Age of introduction to cow’s milk (months)

0–6 months n=306 (%)

7–12 months n=303 (%)

13–24 months n=164 (%)

Total n=773 (%)

<1 10 (3.2) 4 (1.3) 3 (1.8) 17 (2.2)

1.1–2.0 17 (5.6) 17 (5.6) 4 (2.4) 38 (4.9)

2.1–3.0 20 (6.9) 24 (7.9) 4 (2.4) 48 (6.2)

3.1–4.0 20 (6.5) 25 (8.25) 13 (7.9) 58 (7.5)

4.1–5.0 17 (5.6) 31 (10.2) 13 (6.1) 61 (8.0)

5.1–6.0 14 (4.5) 23 (7.6) 10 (2.5) 47 (7.1)

6.1–7.0 – 80 (26.4) 41 (25.0) 121 (15.7)

Table 2 Types of milk used at the time of the survey* and types of milk used since the birth**.

Age Group 0–6 months

n=306 (%)

7–12 months n=303 (%)

13–24 months n=164 (%)

Total n=773 (%)

What type of milk is your child currently receiving?

Breast Milk 250 (81.7) 158 (52.2) 54 (32.9) 462 (60.0)

Infant formula 46 (15.0) 7 (2.3) 0 (0.0) 53 (6.9)

Follow-on formula 5 (1.6) 38 (12.5) 2 (1.2) 45 (5.8)

Milk for growth*** 1 (0.3) 7 (2.3) 18 (10.9) 26 (3.4)

Whole cow’s milk 95 (31.1) 254 (83.8) 162 (98.7) 511 (66.1)

Soy Formula 1 (0.3) 7 (2.3) 5 (3.1) 13 (1.7)

Other 1 (0.3) 1 (0.3) 1 (0.3) 3 (0.4)

What types of milk has your child taken since birth?

Breast Milk 299 (97.7) 292 (96.7) 160 (97.6) 751 (97.1)

Infant formula 91 (29.7) 127 (41.9) 62 (37.8) 280 (36.2)

Follow-on formula 6 (2.0) 62 (20.5) 20 (12.2) 88 (11.4)

Milk for growth*** 1 (0.3) 11 (3.6) 25 (15,2) 37 (15.2)

Whole cow’s milk 106 (34.6) 285 (94.1) 162 (98.8) 553 (71.5)

Soy Formula 3 (1.0) 10 (3.3) 11 (6.7) 24 (3.1)

Other 1 (0.3) 4 (1.3) 1 (0.6) 6 (0.8)

mentioned advice from grandmothers and other family members, respectively. Pediatrician advice was mentioned in 13.7% of cases of children under 6 months, 18.6% for those in their second semester, and 27.6% for children over one year of age.

According to the mothers interviewed, infant formula had been recommended only in the irst and second semesters of life – 48% and 9% of respondents reported this, respectively. Out of the 48 nutritional types of advice in the irst six months of life, 32 came from pediatricians, 2 from other health pro-fessionals, 3 from grandmothers, 4 from other family mem-bers/friends/fellow mothers, and 7 mothers received no type of advice whatsoever.

DISCUSSION

he interviews showed that nearly all mothers during preg-nancy had planned to breastfeed and indeed ofered breast milk immediately after delivery. However, over the irst six months of life, some infants began receiving other types of milk, especially whole cow’s milk. During the irst year of life, infant formula was fed to approximately 15.0% of infants who were not being breastfed. From the sixth month onwards, an increase in the probability of introduction to cow’s milk was detected. he choice of the type of milk was frequently made by the mother and the pediatrician was the health care professional that most often made recommenda-tions for formula use.

According to the Brazilian Pediatric Society, the Brazilian Ministry of Health, and the World Health Organization (WHO), exclusive natural breastfeeding should occur for

at least six months.1-3 In this study, 81.7% of infants in the

irst semester of life received their mother’s milk. However, the information on the percentage of infants who exclusively were breastfed was not available. In order to calculate an esti-mate of the percentage of exclusively breastfed infants under 6 months of age, it was considered that if an infant receives two types of milk in this age group, it is most likely a case of mixed feeding. As shown in Table 2, 250 infants under six months of age were breastfed and 149 received other types of milk. herefore, 93 infants received more than one type of milk (presumably breast milk and another type of milk, according to the current premise). herefore, 157 (250 minus 93) were exclusively breastfed, yielding an estimated rate of exclusive breastfeeding of 51.3% (157/306). According to a 2008 vac-cination campaign survey conducted in Brazilian state capi-tals and in the Federal District, 41.0% of infants were exclu-sively breastfed in the irst 6 months of life,6 a number lower

than the 51.3% estimate observed in this article. However, breastfeeding rates (81.7%) were similar to data obtained in a 2004 epidemiological survey conducted in the state of São Paulo (80.3%).16 In this study, 52.2% of infants in the

second semester of life received both breast milk and other types of milk or food. his value can be considered similar to the 50.0% observed in São Paulo in 200416 and the 58.7%

detected for children between 9 and 12 months of age during the 2008 vaccination campaign.6 his data, related to the irst

year of infancy, unambiguously shows that breastfeeding rates in Brazil are still far below recommendations despite being on the rise since the 1980s.17

Considering this scenario, it is very important to encour-age increased breastfeeding. It is essential to consider the

Table 4 Person responsible for recommending* introduction to cow’s milk according to mothers of children of

each of the age groups studied.

Age Group 0–6 months

n=102 (%)

7–12 months n=274 (%)

13–24 months

n=170 (%) Total

Pediatrician 14 (13.7) 51 (18.6) 47 (27.6) 112 (20.5)

Other health professionals 6 (5.9) 6 (2.2) 1 (0.6) 13 (2.4)

Grandmother 10 (9.8) 45 (16.4) 24 (14.1) 79 (14.4)

Other family members, friends,

and fellow mothers 15 (14.7) 31 (11.3) 21 (12.4) 67 (12.3)

Media, magazines, Internet, books,

and websites 0 (0.0) 1 (0.4) 0 (0.0) 1 (0.2)

Nobody has recommended 56 (54.9) 137 (50.0) 73 (42.9) 266 (48.7)

Does not know 1 (1.0) 0 (0.0) 1 (0.6) 2 (0.4)

Other 0 (0.0) 3 (1.1) 3 (1.8) 6 (1.1)

44

determining factors for weaning in Brazil when developing campaigns and actions encouraging breastfeeding. he main factors associated with early weaning are: inadequate knowl-edge about the advantages and ideal duration of breast-feeding,18 the lack of participation of pregnant women and

nursing mothers in programs encouraging breastfeeding,19

mothers with low levels of education,20 primiparity and

lack of experience with breastfeeding,21-23 diiculty to

ini-tiate breastfeeding immediately after birth,21 cleft nipple,24

mother’s conditions requiring use of medications,20 paciier

use,19,20,23-25 and work.22,24,25 herefore, educational measures

must be targeted at speciic audiences to increase the rate and duration of breastfeeding.

All research indicates that whole cow’s milk is the most common replacement for breast milk. In this study, cow’s milk was used by 31.1% of infants in the irst six months of life, by 83.8% of infants in the second semester of life and by 98.7% of infants in the second year of life (Table 2). Approximately half of the mothers interviewed in all three age groups stated that no one had recommended whole cow’s milk for their children, that is, choice was made based on their own judge-ment. In 26.7% of cases, grandmothers, other family members, and friends were mentioned as sources of advice. According to 16.7% of mothers with children under 6 months, a pedi-atrician had recommended whole cow’s milk. hat number rose to 18.6% for mothers of children in their second semes-ter and 27.6% in the second year of life. he irst six months were observed as the period during which whole milk usage increased the most. hese indings indicate that an educa-tional campaign should be organized to instruct mothers on the negative impact of feeding infants with whole cow’s milk and on the importance of breastfeeding until children com-plete 24 months of age, with complementary feeding after the irst 6 months of life. It should be noted that, out of the 149 infants who in their irst 6 months were not fed breast milk, only 46 (30.8%) were fed infant formulas, whereas 63.8% (95/149) were fed whole milk. For children in their second semester of life, these values were 12.1% (38/314) and 80.1% (254/314), respectively. hese results clearly demonstrate that whole milk is used in lieu of infant formulas as a replacement for breast milk, contrary to recommendations by pediatric societies in Brazil1 and worldwide4,5 as well as the Ministry of

Health,2 all of which claim whole – unmodiied – cow’s milk

should be avoided in the irst year of infancy.

The results of this study confirm what was previously observed in São Paulo, Curitiba, and Recife,7 that is, infant

formulas are used by a small number of infants, who cease to be naturally fed. Inadequate preparation of bottles by dilution or addition of sugar, cereals and chocolate milk powder7 was

also observed. his creates negative repercussions on nutritional composition.8-10 here are many disadvantages of whole cow’s

milk in comparison with infant formulas, including the for-mer’s low essential fatty acid content; lower lactose content, which often motivates the addition of sucrose with its high car-iogenic potential; excessive amount of proteins, which cause renal overload and increased risk of obesity in the future; and insuicient amount of iron with low bioavailability, an import-ant risk factor for iron deiciency and iron deiciency anemia.1

he use of infant formula has been associated with a lower risk of iron deiciency anemia in infants between 7 and 12 months of age, even in comparison with those who received breast milk and other foods.26

In this retrospective study, a limiting factor could be the lack of sample size estimation. However, the number of inter-views was suicient to provide statistically signiicant difer-ences in almost all analyses performed, indicating that the number of interviews was suicient for characterizing correla-tions among variables. Another relevant aspect refers to the proportion of individuals in the sample studied belonging to upper socioeconomic classes, which is slightly higher than the overall Brazilian population. his factor must be taken into account when comparing this study’s results to the Brazilian population as a whole.

In conclusion, breastfeeding rates in Brazil remain below national and international recommendations. Brazilian moth-ers often decide on their own initiative to ofer whole cow’s milk to their children in either the irst or the second semes-ters of life. Despite their proven beneits, infant formulas are used by a small number of infants. A greater number of educational and incentive measures should be implemented to reverse such an unfavorable scenario for Brazilian infants.

Funding

he survey that led to the database upon which this article was based was funded by Danone Early Life Nutrition.

Conflict of interests

REFERENCES

1. Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria; Departamento de Nutrologia. Manual de orientação para a alimentação do lactente, do pré-escolar, do adolescente e na escola. 3rd ed. Rio de Janeiro: SBP; 2012.

2. Brasil - Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção Primária - Departamento de Atenção Básica. Saúde da Criança: nutrição infantil, aleitamento materno e alimentação complementar. Normas e Manuais Técnicos [cadernos de atenção básica n° 23]. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2009.

3. World Health Organization. Infant and young child feeding: model chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals. Geneva: WHO; 2009.

4. Kleinman RE; American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatric Nutrition Handbook. Policy of the Amercican Academy of Pediatrics. 6th ed. Elk Grove Village: AAP; 2009.

5. Agostoni C, Decsi T, Fewtrell M, Goulet O, Kolacek B; ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition, et al. Complementary feeding: a commentary by the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:99-110.

6. Venancio SI, Escuder MM, Saldiva SR, Giugliani ER. Breastfeeding pratice in the Brazilian capital cities and the Federal District: current status and advances. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2010;86:317-32.

7. Caetano MC, Ortiz TT, Silva SG, Souza FI, Sarni RO. Complementary feeding: inappropriate practices in infants. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2010;86:196-201.

8. Morais TB, Sigulem DM. Determination of macronutrients, by chemical analysis, of home-prepared milk feeding bottles and their contribution to the energy and protein requirements of infants from high and low socioeconomic classes. J Am Coll Nutr. 2002;21:284-8.

9. Morais TB, Sigulem DM, de Sousa Maranhão H, de Morais MB. Bacterial contamination and nutrient content of home-prepared milk feeding bottles of infants attending a public outpatient clinic. J Trop Pediatr. 2005;51:87-92. 10. Penna de Carvalho MF, Morais TB, Batista de Morais M.

Home-made feeding bottles have inadequacies in their nutritional composition regardless of socioeconomic class. J Trop Pediatr. 2013;59:286-91.

11. Horta BL, Bahl R, Martines JC, Victora CG. Evidence on the long-term efects of breastfeeding: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Geneva: WHO; 2007.

12. Waterland RA, Garza C. Potential mechanisms of metabolic imprinting that lead to chronic disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:179-97.

13. Geleijnse JM, Hofman A, Witteman JC, Hazebroek AA, Valkenburg HA, Grobbee DE. Long-term efects of neonatal

sodium restriction on blood pressure. Hypertension. 1997;29:913-7.

14. Singhal A, Cole TJ, Lucas A. Early nutrition in preterm infants and later blood pressure: two cohorts after randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;357:413-9.

15. Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa [homepage on the Internet]. Critério Padrão de Classiicação Econômica Brasil - 2008. 2007 [cited 05.04.16]. Available from: http:// www.abep.org/codigosguias/ Criterio_Brasil_2008.pdf 16. Venancio SI, Saldiva SR, Mondini L, Levy RB, Escuder MM.

Early interruption of exclusive breastfeeding and associated factors, state of São Paulo, Brazil. J Hum Lact. 2008;24:168-74. 17. Pan American Health Organization. World Breastfeeding

Week 2012 - understanding the past – planning the future celebrating 10 years of WHO/UNICEF’s global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Washington: PAHO; 2012. 18. Alves CR, Goulart EM, Colosimo EA, Goulart LM. Risk factors

for weaning among users of a primary health care unit in Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais State, Brazil, from 1980 to 2004. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24:1355-67.

19. Brasileiro AA, Ambrosano GM, Marba ST, Possobon RF. Breastfeeding among children of women workers. Rev Saude Publica. 2012;46:642-8.

20. Nascimento MB, Reis MA, Franco SC, Issler H, Ferraro AA, Grisi SJ. Exclusive breastfeeding in southern Brazil: prevalence and associated factors. Breastfeed Med. 2010;5:79-85. 21. Araújo OD, Cunha AL, Lustosa LR, Nery IS, Mendonça RC,

Campelo SM. Brastfeeding: factors tha cause early weaning. Rev Bras Enferm. 2008;61:488-92.

22. Baptista GH, Andrade AH, Giolo SR. Factors associated with duration of breastfeeding for children of low-income families from southern Curitiba, Paraná State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25:596-604.

23. Vieira GO, Almeida JA, Silva LR, Cabral VA, Santana Netto PV. Breast feeding and weaning associated factors, Feira de Santana, Bahia. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant. 2004;4:143-50. 24. Zapana PM, Oliveira MN, Taddei JA. Factors determining the

breastfeeding in children attending public and not-for-proit daycare centers in São Paulo, Brazil. Arch Latinoam Nutr. 2010;60:360-7.

25. Leone CR, Sadeck LS, Programa Rede de Prevenção à Mãe Paulistana. Fatores de risco associados ao desmame em crianças até seis meses de idade no município de São Paulo. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2012;30:21-6.

26. Neves MB, Silva EM, Morais MB. Prevalence and factors associated with iron deiciency in infants treated at a primary care center in Belém, Pará, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2005;21:1911-8.