Vol-7, Special Issue3-April, 2016, pp1934-1945 http://www.bipublication.com

Case Report

A case study of employee voice and organizational performance

in the context of residential aged care

Azam Bazooband1*, Abdolvahab Baghbanian2

and Ghazal Torkfar3 1MBA,Department of Management, Babol Branch,Payam Noor University Babol, Iran. 2PhD in Health Policy; Lecturer, Faculty of Health Sciences,

University of Sydney, Australia. 3

PhD in Public Health; Menzies Centre for Health Policy, School of Public Health, University of Sydney *Corresponding author’s Email: azam.bazooband@gmail.com

2abdolvahab.baghbanian@sydney.edu.au 3

gtor2513@uni.sydney.edu.au

ABSTRACT

As the population of old people is on the great increase in countries, the necessity of aged-care centers is not deniable. Likewise the other health care services, the quality of services provided by care givers for old people in residential aged care centers is a significant and vital factor. The main objective of this paper is to conduct a descriptive research of correlation type on the impact of employee voice on organizational performance in four non-for-profit aged care centers, in Shiraz, Iran. Sample size was estimated 156 based on Morgan table. Data collection tool was employee voice standard questionnaire with 12 items at three dimensions and organizational performance questionnaire with 22 items at seven dimensions. Collected data was analyzed by SPSS statistical software version 22 and the correlation coefficient test (p = <0.05). The significance level was set at P < 0.05 and P < 0.001. Findings showed that there are positive and significant correlations between self-efficacy, encouragement and safety with organizational performance. Also there are positive and significant correlations between organizational performance dimensions including (reliability, attitude, job quality, innovation, co-operation, job quantity, personal learning) and employee voice. Indeed, results showed that, when encouragement taken in to consideration employees may perceive a positive voice climate in an organization, and as a result, the other components of voice climate (safety and self-efficacy) would be developed and the organizational performance will be increased.

Key words: aged care, employee voice, organizational performance, voice climate, Non-for profit aged-care centers.

INTRODUCTION

Iran is a large and diverse country with a land area of almost 1.648 million square kilometers (Babakani, 2000). Iran has a moderately good healthcare systems in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region (WHO EMR), reflected in part in the level of its population health. Its ranking for many aspects of health status matches or exceeds that of other EMR countries. For

system, it plays an important part in this achievement. Total health expenditure, as a proportion of Iranian GDP, accounted for 6.7% in 2013, slightly lower than the average of 8.9% in the Eastern Mediterranean countries in 2013 (Rafiei et all., 2014). As is the case with many countries across the world, the Iranian population is becoming increasingly aged, with research showing this situation as being more pronounced in next future. The current trend in the world population distribution is towards an increasing proportion of older people whose needs and willingness to adopt new health and social services differ. Parallel to the high increase in the global ageing population, the number of elderly people is also showing an upward trend in Iran. The latest census results (in 2013) shows that over 5-8% of the Iran’s population (depending on the source) is older adults (65 years and over) (The World Bank, 2016,"World Development Indicators”). Iran is becoming among the countries with a relatively high population growth rate in the region (Yazdani et al., 2015).

The population ageing is the inevitable result of reduced fertility accompanied by increasing life expectancy in different parts of the world including Iran (Nbavi et al., 2015; Collins & Oliver J, 2014; Lutz, Sanderson, & Scherbov, 2008) Population ageing is expected to have significant implications for Iran over the next several decades in many spheres, including healthcare services and well-being. The growth of the ageing population in the country not only causes a major burden of chronic illness and disability across the country but also creates significant socio-economic implications for both patients and providers including healthcare professionals, nursing homes, residential aged care services and hospitals (Lim & Yu, 2015; Rohani et al., 2015).

Recent data suggest some evidence of socio-economic burden of ageing in the country. For example, 51.3% of the graying of Iran have been hospitalized after 60, among those 42.6% experienced it between 2 or 3 times, while 18.1%

of them returned to hospitals more than 3 times. Surgeries were responsible for about 63.1% of total hospitalizations rate; however, 33.4% were hospitalized because of other factors (Bagheri-Nesam & Shorof, 2014). According to a survey conducted in 1999 by WHO in 23 countries with average and low income, total cost of economic damages of three non-communicable diseases (cardio-vascular diseases, brain attacks and diabetes) between 2006 and 2015 was estimated about 83 milliard dollars; which means that, the cost of health care in people aged over 65 is five times more than that of aged less than 65 (Tabrizi & Azizi, 2014). Healthcare providers are the key elements in the process of care (Brokowski, 2015). There is a great body of research to suggest that employees’ involvement in work-related decisions has served increased job satisfaction, productivity and efficiency (Vasudevan, 2014). Employees’ engagement in decision-making is increasingly seen as an indicator of organizational success and appropriate performance management

(Blumenthal & Kilo, 1998). Simply, performance is viewed as a reflection of the organization's ability to achieve its goals through the work of its people (Miller & Broamiley, 1990).

However, the current healthcare system in Iran is not well-designed or equipped for the demands of ageing. The system is stretched by an ageing population with a growing burden of chronic illness, competent workforce shortage in aged care, silent staff, less motivated staff, and the increasingly outmoded care facilities and services (Rahimi, 2016).

The growing number of old people in the society, a decline in the availability of (formal and informal) caregivers, and restrictions in national healthcare budgets all place further pressure on aged-care facilities and the quality of care they can provide.

What we fundamentally need is a reform in health care to address the above and similar structural and institutional challenges on the delivery of long-term care and support for older people with complex needs (Goodwin et al., 2014).

Improving incentives and support for workforce for example have been found to play a significant role in projecting resident satisfaction in aged-care homes, as shown by a reduction in absenteeism rate, lower turnover and better quality of services (Chous et al., 2003; Castle et al., 2006).

If employees are not encouraged to share their attitudes and opinion in clinical or organizational decision-making inaccurate decisions may be made about the person who receives the care (Baghbanian & Torkfar, 2012). Any failure to engage staff in the organizational decisions and behavior change would result in adverse effects on the quality of services delivered and consequently on the health outcomes. There is evidence to suggest that it is often difficult for many Iranian healthcare workers and professionals to speak out particularly in the context of aged care settings where they are unattended or neglected (Mosadegh Rad & Yarmohammadian, 2006). It is crucial for healthcare executives to allow their employees to speak out and express their ideas about any malpractice or when poor qualities are perceived. A paradigm shift is required from classical/authoritative/traditional management to democratic and participative management, where

staff are inspired and empowered to participate in clinical and organizational decision-making (Ellis & Sorensen , 2007). By providing a supportive voice climate and a mechanism through which healthcare staff can safely raise concerns they would be more likely to bring problems to executive’s attention, and patients would be more satisfied particularly with receiving on-time care services (Nembhard et al., 2015).

Employees’ participation in decision-making would help the Management get a better sense of the older patients’ social world, learn the patients they serve and thus reduces implicit bias. Indeed creating a responsive climate through learning systems is a step forward toward keeping patients and employees safe (Mannion & Davis, 2015). Often, healthcare staffs are ignored when they decide to talk about the system’s failures. Research on employee’s voice has produced some interesting insights in social settings including service-oriented entities (Organ, 1988; Organ and Ryan, 1995); however, very few studies have noticed employees’ voice as important characteristics of long-term care provided for older people. The concept of voice has been extensively researched in social science for explaining employees’ effective functioning and performance, and deemed to promote patients’ quality of care. However, while the concepts of voice and silence have imperious implications in social settings (Bettencourt, 1997; DiPaola and Tschannen Moran, 2004; Hanke & Jurewicz, 2004) its fundamental merit has been greatly overlooked, marginalised or simply neglected in health care. It is at this interface that employees may decide or prefer to keep silence despite their willingness and enthusiasm to announce their own views (Zehir & Erdogan, 2011; Zareie Matin et al., 2011; Adler-Milstein et al 2011).

political skills as the main detrimental factors causing silence (Beshtifar et al., 2012).

It has been widely recognised that giving employees the opportunity to have a say in how they experience their work is beneficial for organizational performance including that of aged-care centres (Wilkinson and Fay 2011). Healthcare authorities must demonstrate a willingness to understand the inter-dependencies of care, and be prepared to break the silence and manage employee’s voice wisely. Ignoring or misleading the employees’ voice in an unethically way may cause low satisfaction, turnover and is harmful to employees, organization and old residents (Henriksen and Dayton, 2006).

The Iranian ageing population is growing in size and diversity (Malakouti, et al., 2015).

Ill-health among them will not only Jeopardise the health of the rest of the population by restricting elderly’s participation in economic activities, but will also strain limited public resources that will need to be allocated to medical treatment (Farasat & Sharifi, 2015).

It is important that policies are in place to ensure elderly’s equitable access to quality care and help them maintain good health throughout their lives. Policy interventions and reforms must be initiated based on rigorous research and shared understanding of the ageing of our communities. The current state of knowledge on elderly health in Iran, however, is characterised by large gaps in our understanding of the role of employee voice in the performance of residential aged-care centres towards sustainable health and social care services for the elderly.

Little of this much-needed research has been conducted to date. Yet the evidence is critical to understanding the balance of benefits of employee voice and harms of employee silence applied across a health organization’s lifespan (Persson & Wasieleski, 2015). This paper aims to investigate the relationship between employee voice/silence and organizational performance among healthcare workers in several aged-care centers in Shiraz, Iran. The study is guided by the following specific

hypothesis: Employee voice/silence has influence on organizational performance, in that there is a significant correlation between the components of voice climate (self-efficacy, motivation and safety) and labor’s performance.

METHODOLOGY

This study is a descriptive-correlative research. All residential aged-care centers (n=7) located in Shiraz – with a population of 280 staff – were asked and invited to take part in this study. The residential aged care is delivered to older people in Iran by service providers who are approved by Behzisti (the government welfare organization in Iran). A sample of 162 respondents agreed to participate in the study, and were then recruited. This included a range of health-related workers such as nurses (assistants and registered), medical professionals, physiotherapists, social workers, psychologists and carers.

Three types of questionnaires were used to collect data from these respondents:

Employee voice standard questionnaire with 12 items that covered three dimensions of self-efficacy (Q1-Q4), motivation (Q5-Q8), and safety (Q9-Q12). The questions were totally in the form of (dis)agreement with the items stated. The respondents were asked to answer the question using a five-point Likert Scale, with the values: 1 (completely disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (neither disagree nor agree), 4 (agree), and 5 (completely agree).

23 to 115, in which higher scores represented stronger organizational performance The overall scores represented the overall employee voice and the mean score estimated for this scale was also 36.

In addition, a 13-item questionnaire was employed to explore employees’ attitudes towards organizational silence, measured in Likert scale (1 through 5, where 1 indicates strongly disagree and 5 shows strongly agree with the statement given). Scores ranged from 13 to 65, where higher scores represented negative attitude to silence behavior. Content validity and reliability of the questionnaires were confirmed by experts. The reliability of both research tools was calculated by Cronbach's Alpha coefficient method (0.90, 0.92 and 0.89 respectively).

The overall α results obtained from a preliminary sample of 30 employees of the centers. Collected data were imported into SPSS statistical software (Version 22) for in-depth analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to assess the demographic characteristics of the respondents. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine the normal distribution of the study variables (employee voice and organizational performance) and their components at Sig.>0.05. Pearson correlation coefficient and multivariable regression analyses were conducted to assess the relations and test the hypotheses. Results were considered significant at conventional P<0.05 level.

Ethics approval was granted before the commencement of the study. The aim and scope of the study were explained to all participants and informed consent forms obtained. Anonymity, privacy and confidentiality were considered throughout the study.

Findings

A total of 156 questionnaire were returned for analysis. Respondents were between the ages of 21 and 50 years old. Most respondents (50%) aged 21 to 30 years old, followed by those ranged from 31 to 40 (41%). Only nine percent belonged to age group 41-50 years old. Female respondents formed 79.9% of the sample. Over half of the respondents (54.8%) were married. The majority of them (73.2%) reported work experience between 1 and 10 years. About two-thirds of the respondents (104, 66.7%) had Bachelor degrees, followed by 30 respondents (19.2%) who had higher degrees.

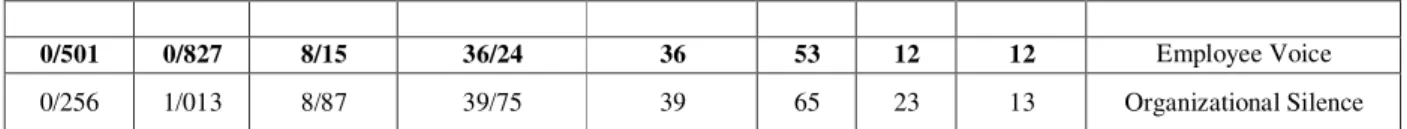

Table 1 shows employee voice in terms of the three components of safety, encouragement and self-efficacy. According to this table, respondents’ score for employee voice ranged from 12 to 53, with a mean score of 36.24 ± 8.15, slightly higher than the spectrum mean score (36). Using the Voice Scale, the three components were also measured and scored for each employee. The mean score of each domain was (12.14 ± 3.02), (12.07 ± 3.32), (12.02 ± 2.94), respectively. The mean scores for each components was higher than the spectrum mean score. The dimension of the ‘self-efficacy’ was reported to be the most important component in measuring employee voice in aged care.

The table also depicts mean score and standard deviation for employees’ attitude towards organizational silence, ranged from 23 to 65, with a mean score of 39.75 ± 8.87, just above spectrum mean score (39).

The distribution of data was normal for employee voice and its components and organizational silence (P-value >0.05).

Table 1: Mean score and standard deviation for different indicators of employee voice and silence

Indicator

Number

Min Max Spectrum Mean Score Respondents’

Mean Score

Standard Deviation Z

Score Sig.

Self-Efficacy

4 4

18 12

12/14 3/02

1/20 0/107

Motivation

4 4

19 12

12/07 3/32

1/18 0/12

Safety

4 4

17 12

12/02 2/94

Employee Voice 12 12 53 36 36/24 8/15 0/827 0/501 Organizational Silence 13 23 65 39 75 / 39 87 / 8 013 / 1 256 / 0

Table 2 shows mean scores and standard deviation of organizational performance in terms of the seven components of reliability, attitude, job quality, innovation, co-operation, job quantity and personal learning. According to this table, respondents’ score for organizational performance ranged from 18 to 105, with a mean score of 75.83 ± 20.19, fairly lower than the spectrum mean score (84). Using the Performance Scale, the seven components were also measured and scored for each employee. The mean score of each domain was (13.96 ± 4.25), (12.76 ± 4.02), (13.85 ± 4.30), (9.61 ± 2.35), (12.89 ± 4.02), (6.35 ± 1.72) and (6.37 ± 1.64), respectively. The mean scores for each components was higher than the spectrum mean score. The dimensions of the reliability and job quality were reported to be the most important components in measuring organizational performance in aged care. The distribution of data was normal for organizational performance and its components (P-value >0.05).

Table 2: Mean score and standard deviation for different indicators of organizational performance

Indicator Number Min Max Spectrum mean Score Respondents’ Mean Score Standard Deviation Z Score Sig. Reliability 4 1 20 12 13/96 4/25 1/13 0/16 Attitude 4 1 20 12 12/76 4/02 0/88 0/42 Job Quality 4 2 20 12 13/85 4/30 1/16 0/14 Innovation 3 3 13 9 9/61 2/35 1/19 0/12 Co-operation 4 2 20 12 12/89 4/02 1/26 0/08 Job Quantity 2 1 10 6 6/35 1/72 1/17 0/09 Learning 2 2 10 6 6/37 1/64 1/27 0/07 Performance 23 18 105 84 75/83 20/19 10/22 0/1

Table 3 indicates the Pearson Correlation Coefficient between organizational performance (dependent variable) and employee voice including its components. According to this table, a positive and significant correlation (direct relationship) exists between self-efficacy and organizational performance (r = 0.567, p-value < 0.001); meaning that employees’ perceived self-efficacy directly contributes to their organizational performance. There is a positive and significant correlation between motivation and organizational performance (r = 0.564, p-value < 0.001), meaning that when employees are welcomed and encouraged by their superiors to express their views about work related issues, they are more likely to make progress towards improving organizational health and performance. A positive and significant correlation was also found between safety and organizational performance (r = 0.491, p-value < 0.001), reflecting that the organizational performance will improve when employees feel safe in the work environment

Table 3: Correlation Coefficient between organizational performance and the components of employee voice

Variable Employee voice

Self-efficacy Motivation Safety

Organisational performance score

Pearson

Correlation (r) 0.567 0.564 0.491 Sig. (2-tailed) 0.00 0.00 0.00

N 156 156 156

Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed).

organizational performance including reliability, attitude, job quality, innovation, co-operation, job quantity and organizational learning correlate with employee voice (positive) and silence (negative).

Table 4: Correlation coefficients between components of organizational performance and employee voice

Variable Organisational performance

Reliability Attitude Job Quality Innovation Co-operation Job Quantity Learning

Employee voice score

R 0.511 0.702 0.527 0.590 0.554 0.413 0.566

P 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

N 156 156 156 156 156 156 156

Employee Silence

score

R -0.392 -0.492 -0.411 -0.435 -0.460 -0.38 -0.472

P 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

N 156 156 156 156 156 156 156

Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed).

Table 5 indicates the overall correlation between organizational performance, employee voice and employee silence. According to this table organizational performance correlates positively with employee voice (r = 0.617, P < 0.001) and negatively (r = -0.479, P < 0.001), reflecting that the more employees’ voice is heard and acted upon, the stronger organizational performance they would have.

Table 5: Correlation Coefficient between organizational performance, employee voice and employee silence

Variable Employee voice Employee silence

Organisational performance score

R 0.617 -0.479

Sig. 0.00 0.00

N 156 156

Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed).

DISCUSSION

The main objective of the current study was to explore whether employees’ voice and/or silence behavior is related to their performance towards improvement in organizational performance. We carried out this research in an aged care context in Iran, a very different cultural setting from many developed countries where to best of our knowledge most of the previous, similar studies have been conducted irrelevant to health( Detert & Burris, 2007; Tucker & Edmondson, 2003)

Our main theoretical argument was that employee’s attitudes about their voice or silence contributes significantly to organizational performance.

Our findings showed that employees’ voice and silence demonstrated statistically significant relationships, positively and negatively, respectively, with employees’ organizational performance within the aged care facilities. Employee voice and/or silence is often debated in organizational and management literature. For many researchers and policy-makers, voice is

considered to be a powerful force which usually results in improving the employees’ job performance and thus the enhancement of organization’s health and life (Bowen & Blackmon, 2003; Nikolaou et al., 2008; Morrison & Miliken, 2000).

In this study, we found that all dimensions of employee voice (i.e. self-efficacy, motivation and safety) have a positive and significant correlation with organizational performance. It makes sense that an individual with enhanced self-efficacy will be more likely and willing to put more effort in persisting longer and performing better compared to individuals with low self-efficacy (Delery & Doty, 1996).

A ‘motivated’ person is also more likely to work more actively and puts more dedication than a less motivated one towards achieving organizational goals (Simon, 1991).

It is at this interface that goal-directed motivation, as a human need, can produce goal-directed behaviour. Likewise, healthy employees who feel safe, secure and cared in their workplace will be more likely to express ideas, opinions, or concerns more freely and thus will work more productively than employees who feel unsettled and uncomfortable or feel their life at risk (Marien et al., 2015).

These findings are consistent with those of previous research; however, it should be noted that despite the availability of a great body of literature on the predictive role of employee voice and silence in organizational performance very little has been conducted in a health environment. Previous research has largely focused on social sciences or isolated single factors but this research is mainly focused on employee voice and organizational performance within an aged care environment. To best of our knowledge, this study constituted one of the first attempts to investigate this issue in an Iranian health and disability context. It is therefore not possible to draw any proper comparison between our findings and those of previous research.

We also found that a positive relationship exists between dimensions of organizational performance (reliability, attitude, job quality, innovation, co-operation, job quantity and learning) and employee voice. While these findings are not new in the Iranian healthcare context, our research highlights their persistent nature and strengthens the knowledge that the health and wellbeing of the elderly residents in aged care centers is affected by multiple factors beyond the prevention, treatment and management of disease, for instance employees’ engagement in clinical or organizational decision-making. Indeed, the organizational performance would enhance within an organization that supports voice climate and that encourages employees to comment on work-related issues (Frazier & Bowler, 2015).

There is strong evidence that suggests consideration of employee voice and their

involvement in both clinical decisions and organizational operation not only motivates them but also enables them to contribute more effectively and efficiently to overall performance of the organization

(Vilane, 2015).

According to a survey by the American Psychological Association (APA), employees who felt valued reported higher levels of engagement, satisfaction and motivation, with almost 93% reported being motivated to do their best work (Albert et al., 2015).

This issue is of particular importance within the aged care services, where there is an increased likelihood that an elderly person won’t be able to live independently, will become a victim of social isolation, or won’t understand when and how to seek care.

The elderly are the most rapidly growing and vulnerable segment of the population and the most costly healthcare consumers that are required to be well taken care of to maintain or sustain their health status, and employee voice play a key role in in bringing the vision and values to the elderly life in way that employees not only understand, but engage emotionally and then act on. The employee choice and voice should be seen as a meaningful part of formulating and implementing health policy decisions particularly when healthcare workforce is facing a critical shortfall of health professionals. Quality aged care and services in health sectors necessitates an encouraging and safe voice climate where employees can freely express their views towards building a high-performance organization.

explain the relationships identified. Use of empirical quantitative and/or qualitative research that includes well-developed measures with sound psychometric properties is recommended for future research.

CONCLUSION

At the time of rapid changes in population demography due to changes in environmental transformation, economic crisis, globalization forces, information technology, workforce distribution, patterns of diseases and so on, healthcare delivery and funding is becoming increasingly complex and inter-dependent for service users and providers (Baghbanian & Torkfar, 2012; Khammarnia, 2013). Adaptive and innovative healthcare delivery systems are required that can accommodate the healthcare needs of older people with disability, and/or chronic or multiple conditions (Maglio et al., 2015). With safe and flexible workplaces that can also accommodate the needs of healthcare workers in order to enable them to fulfill the inherent requirements of their job (Sanford, 2016). Consideration of employee voice is crucial to their performance and to the positive organizational performance. The present study revealed that components of employee voice and silence namely self-efficacy, motivation and safety contribute to organizational performance. It was found that a positive voice climate acts as an important mediator of organizational and job performance. The study has potential implications for healthcare behaviours mediated by employees’ engagement in decision-making. Healthcare authorities and professionals are encouraged to consider the importance of employee voice and silence while making clinical and organizational decisions related to aged care. The initial findings of this research could be also used as a guide for future studies exploring the antecedents of employees’ voice behavior at work.

ACKNOWLEDGE: We would like to

acknowledge the individuals who kindly donated

their time and energy to participate in this study. We also thank the colleagues who provided insight and expertise towards implementation of this research even though they may not agree with all of the interpretations/conclusions of this paper. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Azam Bazooband,

No 203, 66 St, 66/4 Alley, Pasdaran Blvd., Shiraz, Iran.

P.O. Box 7184958975 +98 9303306158

REFERENCE:

1. Babakani, F. (2000). Country Presentation Iran. Retrieved February 15, 2016, http://users.ugent.be/~aremautd/iran.html. 2. World Health Organization. (2015). Global

Health Observatory Data Repository. 2014. 3. Baghbanian, A. (2012). Health scope in iran:

the way forward. Health Scope,1(2), 50-51. 4. Rafiei, M., Ezzatian, R., Farshad, A., Sokooti,

M., Tabibi, R., & Colosio, C. (2014). Occupational Health Services Integrated in Primary Health Care in Iran. Annals of global health, 81(4), 561-567.

5. The World Bank. 2016. "World Development

Indicators." URL:

http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.aspx 6. Yazdani, A., Fekrazad, H., Sajadi, H., &

Salehi, M. (2015). Relationship between social participation and general health among the elderly. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci),18(10), 599-606.

7. Nabavi, S. H., Aslani, T., Ghorbani, S., Mortazavi, S. H., Taherpour, M., & Sajadi, S. (2015). The prevalence of malnutrition and its related factors among the elderly of Bojnourd, 2014. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci), 19(1), 32-36.

8. Collins, J., & Oliver J, R. (2014). Evolution, Fertility and the Ageing Population SSRN:

9. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2208886.

11.population ageing. published online. doi: 10.1038/nature06516

12.Rohani, H., Eslami, A. A., Jafari-Koshki, T., Raei, M., Abrishamkarzadeh, H., Mirshahi, R., & Ghaderi, A. (2015). The factors affecting the burden of care of informal caregivers of the elderly in Tehran. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences (J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci), 18(12), 726-733.

13.Lim, K., & Yu, R. (2015). Aging and wisdom: age-related changes in economic and social decision making. US national librery of

medicine (PubMed). doi:

10.3389/fnagi.2015.00120

14.Bagheri-Nesam, M., & Shorof, S. A. (2014). Cultural and Socio-Economic Factors on Changes in Aging among

15.Tabrizi, J. S., & Azizi, A. (2014). Aging.

Journal of Halth Department (Tabriz Medical University), 8-9.

16.Borkowski, N. (2015). Organizational behavior in health care. Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

17.Vasudevan, H. (2014). Examining the Relationship of Training on Job Satisfaction and Organizational Effectiveness. International

Journal of Management and Business

Research, 4(3), 185-202.

18.Blumenthal, D., & Kilo, C. M. (1998). A report card on continuous quality improvement. Milbank quarterly, 76(4), 625-648.

19.Miller, K., & Bromiley, P., (1990). Strategic Risk and Corporate Performance: An Analysis of Alternative Risk Measure, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 33, No.4. PP.756-779.

20.Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states (Vol. 25). Harvard university press.

21.Travis, D. J., Gomez, R. J., & Barak, M. E. M. (2011). Speaking up and stepping back: Examining the link between employee voice

and job neglect.Children and Youth Services Review, 33(10), 1831-1841.

22.Markos, S., & Sridevi, M. S. (2010). Employee engagement: The key to improving performance. International Journal of Business and Management,5(12), 89.

23.Ellis, C. M., & Sorensen, A. (2007). Assessing employee engagement: the key to improving productivity. Perspectives, 15(1), 1-9.

24.Rahimi, A. (2016). Exploring the nature of elderly people life style: A grounded theory. Iranian Journal of Ageing, 10(4), 0-0. 25.Goodwin, N., Dixon, A., Anderson, G., &

Wodchis, W. (2014). Providing integrated care for older people with complex needs: lessons from seven international case )studies. London: The King’s Fund.

26.Chou, S. C., Boldy, D. P., & Lee, A. H. (2003). Factors influencing residents' satisfaction in residential aged care. The Gerontologist, 43(4), 459-472.

27.Castle, N. G., Degenholtz, H., & Rosen, J. (2006). Determinants of staff job satisfaction of caregivers in two nursing homes in Pennsylvania. BMC Health Services Research, 6(1), 1.)

28.Abdolvahab, B., Ghazal, T., & Yaser, B. (2012). Decision-making in Australia’s healthcare system and insights from complex adaptive systems theory. Health

Scope, 2012(1, May), 29-38.

Ali Mohammad Mosadegh Rad, Mohammad Hossein Yarmohammadian, (2006) "A study of relationship between managers' leadership

style and employees' job

satisfaction", Leadership in Health Services, Vol. 19 Iss: 2, pp.11 - 28).

29.Ellis, C. M., & Sorensen, A. (2007). Assessing employee engagement: the key to improving productivity. Perspectives, 15(1), 1-9.

31.Mannion, R., & Davies, H. T. (2015). Cultures of silence and cultures of voice: the role of whistleblowing in healthcare organisations. International journal of health policy and management, 4(8), 503.

32.Organ, D. W. 1988. Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome . Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

33.Organ, D. W., & Ryan, K. 1995. A meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior. Personnel Psychology, 48: 775–802. 34.(Bettencourt, 1997; Cantrell et al., 2001;

DiPaola and TschannenMoran, 2001; DiPaola et al., 2007; Jurewicz, 2004)

35.DiPaola, M., Tschannen-Moran, M., & Walther-Thomas, C. (2004). School principals and special education: Creating the context for academic success.Focus on Exceptional Children, 37(1), 1.

36.Hanke, W. O. J. C. I. E. C. H., & Jurewicz, J. O. A. N. N. A. (2004). The risk of adverse reproductive and developmental disorders due to occupational pesticide exposure: an overview of current epidemiological evidence.International journal of occupational medicine and environmental health,17(2), 223-243.

37.Zehir, C., & Erdogan, E. (2011). The association between organizational silence and ethical leadership through employee performance. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 1389-1404.

38.Zarei Matin, H., Taheri, F., & Sayar, A. (2011). Organizational silence: concepts, causes, and outcomes. Iranian journal of management sciences,6(21), 77-104.

39.Adler Milstein, J. J.singer, S. W.Toffel, M. Mnagerial Practices that promote voice and takingcharge among front-line workers. Working Paper of Harvard Business School. September 2012, 11-005.

40.Beheshtifar, M., Borhani, H., & Moghadam, M. N. (2012). Destructive role of employee silence in organizational Success. International

journal of academic research in business and social sciences, 2(11), 275.

41.Wilkinson, A. and Fay, C. (2011), New times for employee voice?. Hum. Resour. Manage., 50: 65–74. doi: 10.1002/hrm.20411

43.Henriksen, K., & Dayton, E. (2006). Organizational silence and hidden threats to patient safety. Health services research, 41(4p2), 1539-1554.

44.Malakouti, S. K., Pachana, N. A., Naji, B., Kahani, S., & Saeedkhani, M. (2015). Reliability, validity and factor structure of the CES-D in Iranian elderly. Asian journal of psychiatry, 18, 86-90.

45.Farasat, H., & Sharifi, M. (2015). Ageing and growth of the endangered Kaiser's Mountain Newt, Neurergus kaiseri (Caudata: Salamandridae), in the Southern Zagros Range, Iran. Journal of Herpetology.

46.Persson, S., & Wasieleski, D. (2015). The seasons of the psychological contract: Overcoming the silent transformations of the employer–employee relationship. Human Resource Management Review, 25(4), 368-383.

47.Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open?. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869-884

48.Tucker, A. L., & Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Why hospitals don't learn from failures: Organizational and psychological dynamics that inhibit system change. California Management Review, 45(2), 55-72.

49.Bowen, F., & Blackmon, K. (2003). Spirals of Silence: The Dynamic Effects of Diversity on Organizational Voice*. Journal of management Studies, 40(6), 1393-1417. 50.Nikolaou, I., Vakola, M., & Bourantas, D.

(2008). Who speaks up at work? Dispositional influences on employees' voice behavior. Personnel Review,37(6), 666-679. 51.Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000).

development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management review, 25(4), 706-725.

52.(Delery, J. E., & Doty, D. H. (1996). Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Academy of management Journal,39(4), 802-835.).

53.Simon, H. A. (1991). Organizations and markets. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(2), 25-44.

54.Agyapong, V. I., Osei, A., Farren, C. K., & McAuliffe, E. (2015). Factors influencing the career choice and retention of community mental health workers in Ghana. Human resources for health, 13(1), 56.

55.Marien, H., Aarts, H., & Custers, R. (2015). The interactive role of action-outcome learning and positive affective information in motivating human goal-directed behavior. Motivation Science, 1(3), 165. 56.Frazier, M. L., & Bowler, W. M. (2015). Voice

Climate, Supervisor Undermining, and Work

Outcomes A Group-Level

Examination. Journal of Management, 41(3), 841-863.

57.Vilane, N. P. (2015). Leadership and compliance in the residential care facilities for older persons in Ekurhuleni (Doctoral dissertation.

58.Albrecht, S. L., Bakker, A. B., Gruman, J. A., Macey, W. H., & Saks, A. M. (2015). Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage: an integrated approach. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 2(1), 7-35.

59.Khammarnia, M., Baghbanian, A., Mohammadi, R., Barati, A., & Safari, H. (2013). The relationship between organizational health and performance indicators of Iran University hospitals. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, 63(8), 1021-1026.

60.Maglio, P. P., Kwan, S. K., & Spohrer, J. (2015). Commentary—Toward a research agenda for human-centered service system innovation. Service Science, 7(1), 1-10.

61.Sanford, J. A. (2016). Universal design as a human factors approach to return to work interventions for people with a variety of diagnoses. InHandbook of Return to Work (pp. 403-419). Springer US.