JPediatr(RioJ).2017;93(3):214---222

www.jped.com.br

REVIEW

ARTICLE

Association

between

dietary

pattern

and

cardiometabolic

risk

in

children

and

adolescents:

a

systematic

review

夽

Naruna

Pereira

Rocha

a,∗,

Luana

Cupertino

Milagres

a,

Giana

Zarbato

Longo

b,

Andréia

Queiroz

Ribeiro

b,

Juliana

Farias

de

Novaes

baUniversidadeFederaldeVic¸osa(UFV),ProgramadePós-Graduac¸ãoemCiênciadaNutric¸ão,Vic¸osa,MG,Brazil

bUniversidadeFederaldeVic¸osa(UFV),DepartamentodeNutric¸ãoeSaúde,Vic¸osa,MG,Brazil

Received11October2016;accepted3November2016

KEYWORDS Dietary; Patterns; Cardiovascular; Children; Adolescent

Abstract

Objective: Toevaluatetheassociationbetweendietarypatternsandcardiometabolicrisk fac-torsinchildrenandadolescents.

Datasource: ThisarticlefollowedtherecommendationsofPRISMA,whichaimstoguidereview publicationsinthehealtharea.Thearticlesearchstrategyincludedsearchesintheelectronic databasesMEDLINE viaPubMed,Scopus,andLILACS.Therewasnodatelimitationfor publi-cations.ThedescriptorswereusedinEnglishaccordingtoMeSHandinPortugueseaccording toDeCS. Onlyarticles ondietarypatternsextracted by theaposteriori methodology were included.Thequestion tobeansweredwas:howmuchcanan‘‘unhealthy’’dietarypattern influencebiochemicalandinflammatorymarkersinthispopulation?

Datasynthesis: The studies showed an association between dietary patterns and car-diometabolicalterations. Thepatternswere characterizedasunhealthy when associatedto theconsumptionofultraprocessedproducts,poorinfiberandrichinsodium,fat,andrefined carbohydrates.Despitetheassociations,inseveralstudies,thestrengthofthisassociationfor someriskmarkerswasreducedorlostafteradjustingforconfoundingvariables.

Conclusion: Therewasapositiveassociationbetween‘‘unhealthy’’dietarypatternsand car-diometabolicalterationsinchildrenandadolescents.Someunconfirmedassociationsmaybe relatedtothedifficultyofassessingfoodconsumption.Nevertheless,studiesinvolvingdietary patternsandtheirassociationwithriskfactorsshouldbeperformedinchildrenandadolescents, aimingatinterventionsandearlychangesindietaryhabitsconsideredtobeinadequate. ©2017PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.onbehalfofSociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.Thisis anopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/).

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:RochaNP, MilagresLC,Longo GZ,RibeiroAQ,NovaesJF. Associationbetween dietarypattern and

car-diometabolicriskinchildrenandadolescents:asystematicreview.JPediatr(RioJ).2017;93:214---22.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:narunarocha@hotmail.com(N.P.Rocha). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2017.01.002

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Alimentac¸ão; Padrões; Cardiovascular; Crianc¸as; Adolescente

Associac¸ãoentrepadrãoalimentareriscocardiometabólicoemcrianc¸as eadolescentes:umarevisãosistemática

Resumo

Objetivo: Avaliaraassociac¸ãoencontradanosestudosentrepadrãoalimentarefatoresderisco cardiometabólicosemcrianc¸aseadolescentes.

Fontedosdados: Este artigo seguiuas recomendac¸ões do PRISMA, queobjetiva orientar as publicac¸õesderevisãonaáreadasaúde.Aestratégiadebuscadosartigosincluiupesquisasnas baseseletrônicasMedlineviaPubMed,ScopuseLilacs.Nãohouvedatalimitedepublicac¸ão. OsdescritoresforamusadoseminglêsdeacordocomMeSHeemportuguêssegundoosDeCS. Apenasartigosdepadrãoalimentarextraídospelametodologiaaposterioriforamincluídos.A perguntaaserrespondidafoi:quantoumpadrãoalimentar‘‘nãosaudável’’podeinfluenciar nosmarcadoresbioquímicoseinflamatóriosdessapopulac¸ão.

Síntesedosdados: Osestudos demonstraramhaverassociac¸ãoentreospadrõesalimentares ealterac¸õescardiometabólicas.Ospadrõescaracterizadoscomonão saudáveiseram marca-dospeloconsumo deprodutosultraprocessados,pobresem fibrasericosemsódio, gordura ecarboidratosrefinados.Apesardasassociac¸ões,emváriosestudos,aforc¸adessaassociac¸ão paraalgunsmarcadoresderiscoerareduzidaouperdidaapósosajustesparaasvariáveisde confusão.

Conclusão: Houve associac¸ão positiva entre os padrões alimentares ‘‘não saudáveis’’ e as alterac¸õescardiometabólicasemcrianc¸aseadolescentes.Algumasassociac¸õesnãoconfirmadas podemestarrelacionadasaprópriadificuldadedeavaliaroconsumoalimentar.Apesardisso, estudosenvolvendopadrõesalimentaresesuaassociac¸ãoafatoresderiscodevemser realiza-dosemcrianc¸aseadolescentesobjetivandointervenc¸õesemodificac¸õesprecocesnoshábitos alimentarestidoscomonãoadequados.

©2017PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.emnomedeSociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.Este ´

eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Overweightinchildhoodandadolescenceisamajor con-cernworldwide.1,2Littleisknownaboutthecomplications

thatearly-onsetobesitycancauseinthelongterm.3,4Given

the uncertainties, many associations have been made to betterunderstandtheconsequencesofoverweightand obe-sityfortheonsetofcardiometaboliccomplicationsinearly life.1,5

Some established associations between the genesis of obesityandalterationsincardiovascularriskmarkers---such asinflammatory cytokines, C-reactive protein, traditional biochemical parameters (total cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, insulin), diet, and physical activity --- have been evaluatedinstudieswithadultsandmuchisalreadyknown aboutthedirectionoftheserelations.4,6However,itcanbe

observed thatthese studies arenotvery commonin chil-dren and adolescents,andmore consistent informationis stillnecessary about the behavior of cardiometabolicand inflammatoryriskfactorsinthisperiod.3,5

Dietisanimportantmodifiableriskfactorintheetiology of diseases, given the increasing number of epidemiolog-ical studies that address its relation with the onset of chronic diseases.7---9 The methodology of identification of

thedietarypatternofspecificpopulationshasbeenwidely usedinobservationalstudies,andhasbeenusefulto iden-tifytheassociationbetweendietandcardiometabolicrisk factors.8,10,11

Dietary patterns can better inform about diet-disease associations than the assessment of isolated foods or nutrients, because they consider the total dietary intake andtheinterrelationships betweenmany foods and nutri-ents,aswellastheirsynergisticeffects.7,9Theyhavebeen

widely used due to the understanding that nutrients are rarelyconsumedinisolation,andthatnutrient-only inves-tigationsunderestimatethepossible interactionsbetween nutrientsorbetweenfoodsandotherdietcomponents.8

The identification of dietarypatternsconsidered tobe unhealthymay berelatedtochangesinbodycomposition andbiochemicalandinflammatory parametersin children andadolescents.7,10 Consideringthat childhoodis aphase

during which eating habits are formed, the adoption of healthyeatingpracticesin thisperiodcan havefavorable consequencesfortherestoflife.

Inthissense,theaimofthissystematicreviewarticlewas toevaluatetheassociationfoundbetweendietarypatterns andcardiometabolicriskfactorsinstudiesofchildrenand adolescents.Thehypothesiswasthatunhealthydietary pat-ternsareassociatedwithalterations intheseriskmarkers intheassessedgroup.

Methods

216 RochaNPetal.

guidesystematic reviewsandmeta-analyses inthe health area.12Thearticlesearchstrategyincludedsearchesinthe

electronicdatabasesMEDLINE(NationalLibraryofMedicine, USA) via PubMed, Scopus, LILACS (Latin American and CaribbeanLiteratureinHealthSciences),andSciELO (Sci-entificElectronicLibraryOnline),withnopublicationdate limitations.

Articleidentificationandselectioninalldatabaseswere simultaneously performed by two researchers during a three-monthperiodbetweenFebruaryandApril2016.The words used as descriptors were: diet, dietary, patterns, risk,cardiovascular,biomarkers,children,adolescent,and health.ThedescriptorswereusedinEnglishaccordingtothe MedicalSubjectHeadings(MeSH)andinPortuguese accord-ing to the Descriptors in Health Sciences (in Portuguese, DescritoresemCiênciasdaSaúde[DeCS]).

The searches in the databases were performed using the keywords with Boolean operators represented by the connector terms AND, OR, and NOT. Thus, the following combinationswereused:dietarypatternsANDriskAND car-diovascularANDadolescent;dietarypatternsANDriskAND cardiovascularANDchildren;dietarypatternsAND biomark-ers AND cardiovascular AND adolescent; dietary patterns ANDbiomarkersAND cardiovascularAND children;dietary patterns AND health AND cardiovascular AND adolescent; dietarypatternsAND healthAND cardiovascularAND chil-dren;dietANDriskANDcardiovascularANDadolescent;diet ANDriskANDcardiovascularANDchildren.These combina-tionswerealsousedforthetermsORandNOT,respectively, inallsearcheddatabases.

The reviewsearchedfor studiesthat evaluateddietary patternsusingtheaposteriorimethodologyonly,whichuses multivariateanalysistechniquestoextractthepatterns,13

andthatassociatedthepatternfoundwithcardiometabolic riskfactorsinchildrenand/oradolescents.Thearticlesthat consideredonlyfoodpatternidentificationorthatonly asso-ciatedthepatternwithanthropometricmeasurementswere notincluded, astheobjectivewastodetect howmucha foodpatternclassifiedas‘‘unhealthy’’couldinfluencethe biochemicalandinflammatorymarkersinthispopulation.

As non-inclusion criteria, the authors highlight studies conductedwithadults,pregnantwomen,childrenunder2 yearsofage,reviewarticles,experts’comments,andthose publishedinlanguagesotherthanPortugueseandEnglish.

Article selection and identification in the databases wereindependently and systematically performed by two researchers, who carried out the initial identification through the titles of the publications found by the descriptorsand, later, bythe abstracts obtained by elec-tronicsearch.Afterthe selectionof publications bytitles and abstracts, a new assessment was made by the two researchers,whoconsensuallydeterminedthestudiestobe readinfull andincluded inthe review.The referencesof theselectedstudieswereassessed,aimingtoincludeother articlesofpotentialinterest.

Results

Atotalof364articleswereidentifiedonthistopic.Ofthe 50publicationsselectedforreadingoftheabstractandof thefulltext,onlysevenarticlesmettheestablishedcriteria

forthissystematicreview,andtwowerefoundthroughthe referencesofthefirstselectedarticles(Fig.1).

Themaincharacteristicsofthestudies,suchaslocation, yearofpublication,design,ageoftheparticipants, statisti-calanalysisusedforfoodpatternderivation,andtheother assessedvariables,aredescribedinTable1.Thearticles dif-ferregardingthetypeofdesignandintermsofthesample age,withmost(78%)beingcross-sectionalstudies.

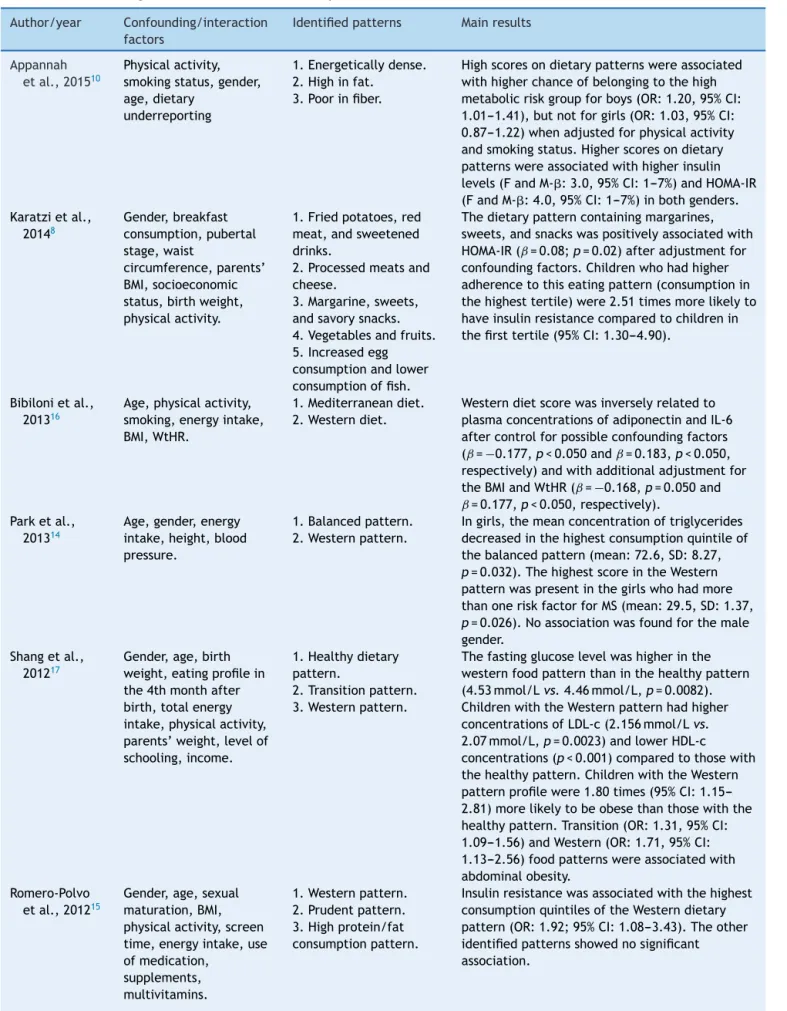

Table 2 shows the identified confounding factors that wereincludedintheregressionmodels,theidentifiedfood patternsnamedaccordingtothedefinitionofeachauthor, and the main results of the articles. Confounding fac-tors were described because they are important for the necessary adjustments in statistical analyses to increase the accuracy of the association strength. In most publi-cations, the authors performed the analyses divided into models adjusted first for gender and age and then for other variables thatcouldinfluence the characteristics of thefoodpatternandtheassociationwithcardiometabolic risk markers, suchasparental level ofschooling, level of physicalactivity,income,pubertalstage,andtotalenergy intake.10,14,15

Duringthereadingofthearticles,theauthorsdescribed the difficulty of approaching the association between dietary patterns and cardiometabolic risk factors in the group of children and adolescents, since there is little information available on the effects of dietary patterns oncardiometabolicalterationsinthepediatricgroup.9,10,16

However,itisimportanttoevaluatetheassociationbetween dietarypatternsandchronicnoncommunicablediseases in childhood and adolescence, since cardiometabolic alter-ations caninfluence the current andfuturehealth of this group.17

Theidentificationofthefoodpatternvariedlittlein rela-tion to the statistical analysis used. Principal component analysis(PCA)wasthemostpredominant(78%),which rep-resents analternativeapproachfortheevaluationoffood andnutrientintake,beingusefultoassessthediet-disease association.7 Unhealthy eating patterns were defined as

‘‘Western’’bymoststudies(55%),alsousingtheterms‘‘fast food,’’9‘‘highconsumptionofproteinandfat,’’15and‘‘high

infat.’’10 Onlyonestudy didnotnametheidentified

pat-terns,maintainingonlythenamesofthefoodsthatbelonged toeachgroup.8

In the methodology of four studies, parents or guardians assisted in the evaluation of children’s food consumption.10,14,15,18 In2013, Parketal.14 performed the

dietaryassessmentinasubgroupoftheirsample(503 par-ticipants); the authors explained that this practice was adoptedduetopracticaldifficultiesincollectingthedata.

In general, a positive association was observed in the studies between an ‘‘unhealthy’’ eating pattern and increasedcardiometabolicrisk.7---10,14---18

AccordingtoApannahetal.,in2015,10thepattern

iden-tifiedasenergetically dense,high infat, and lowin fiber was associated with cardiometabolic alterations, such as highinsulinconcentrationandinsulinresistanceinboth gen-ders.Incontrast,Karatzietal.,in20148foundthat,ofthe

pattern

and

cardiometabolic

risk

217

Table1 Characteristicsoftheevaluatedstudies.

Author/year Country Design Age(n) Referencemethod Statisticalanalysisa Anthropometry Tests

Appannahetal., 201510

Australia Cohort 14(n=1611)and 17years(n=1009)

Semi-quantitativeFFQ relatedtoprevious12 months

Reducedrank regressionb

Height,weight, BMI,WC

Insulin,glucose,TG, HDL-c,LDL-c,HOMA-ir

Karatzietal., 20148

Greece Cross-sectional

9---13years (n=1912)

24-hfoodrecord(two daysaweekandone weekend)

Principalcomponent analysisc

Weight,height, WC

Insulin,glucose, HOMA-ir

Biblionietal., 201316

Spain Cross-sectional

12---17years (n=219)

Validated

semi-quantitativeFFQ relatedtoprevious12 months

Principalcomponent analysis

Weight,height, WC,WtHR

Adiponectin,leptin, TNF-␣,PAI-1,IL-6

Parketal.,201314 Korea

Cross-sectional

8---9years (n=1008)

24-hfoodrecord (performedinthree days)

Principalcomponent analysis

WC,BMI,blood pressure

Glucose,TC,TG, HDL-c,ALT,ASTand CT/HDL-c,TG/HDL-c Shangetal.,

201217

China Cross-sectional

6---13years (n=5267)

24-hfoodrecord(two daysaweekandone weekend)

Groupinganalysis Weight,height, BMI,blood pressure,WC

Glucose,TC,TG, HDL-c,LDL-c

Romero-Polvo etal.,201215

Mexico Cross-sectional.

7---18years (n=916)

Semi-quantitativeFFQ relatedtoprevious12 months

Principalcomponent analysis

Weight,height, BMI,WC,body fat%(DXA)

Glucose,insulin, HOMA-ir

Dishchekenian etal.,20119

Brazil Cross-sectional

14---19years (n=76)

Four-dayfoodrecord (threedaysaweekand oneweekend)

Principalcomponent analysis

Weight,height, bloodpressure

TC,LDL-c,HDL-c,TG, glycemia,insulin

Ambrosinietal., 20107

Australia Cohort cross-sectional

14years(n=1139) Semi-quantitativeFFQ relatedtoprevious12 months

Principalcomponent analysis

Weight,height, WC,blood pressure

TC,LDL-c,HDL-cTG, glycemiaandinsulin, HOMA-ir

Mikkiläetal., 200718

Finland Cohort 3---39years (n=1200)

48-hfoodrecord Principalcomponent analysis

Height,weight, BMI,blood pressure

CRP,TC,LDL-c,HDL-c, VLDL-c,ApoA1s,Apo B,triacylglycerol, insulin,homocysteine

FFQ,foodfrequencyquestionnaire;BMI,bodymassindex;WC,waistcircumference;TG,triglycerides;HDL-c,high-densitylipoproteincholesterol;LDL-c,low-densitylipoprotein

choles-terol;HOMA-IR,homeostasismodelassessment---insulinresistance;PAI-1,plasminogenactivatorinhibitor-1;IL-6,interleukin6;WtHR,waisttoheightratio;TC,totalcholesterol;ALT,

alanineaminotransferase;AST,aspartateaminotransferase;CRP,C-reactiveprotein;ApoA1,apolipoproteinA1;ApoB,apolipoproteinB;DXA,dual-energyX-rayabsorptiometry.

a Statisticalanalysisusedtodeterminethedietarypattern.

b Reducedrankregression(RRR).

218 RochaNPetal.

Publications identified in databases with descriptors: diet, patterns, risk, cardiovascular, health, children, adolescent, “dietary

patterns” from February to April, 2016 (n=364).

Excluded articles:

Repeated articles: 7; Articles with adults: 5; determination of the dietary pattern only: 9; diet assessment by FFQ, record or 24-hr food

record only: 12; use of the a priori methodology: 10 1st stage of refinement:

Search by title and eligibility criteria.

Selected articles: 7 articles plus 2 articles selected

by reverse search.

Pre-selected publications: 50 articles for abstract/full text

reading.

Final articles: 9 articles

Figure1 Studyselection,evaluation,andinclusionprocess.

Bibiloni et al.,16 in a 2013 study with 219 girls aged

12---19, identified that the Western dietary pattern was associatedwithahigherconcentrationofadiponectinand interleukin-6 (IL-6). However, the authors observed that inflammationwasmoreinfluencedbybodymassindex(BMI) andwaist-to-heightratio(WtHR)thanbytheidentifiedfood pattern.

Park et al.,14 in a 2013 study with Korean

prepuber-tal children, identified two eating patterns (‘‘balanced’’ and‘‘Western’’), andfoundnoassociation withmetabolic alterations in boys. In girls, the mean concentration of triglyceridesdecreased at the highest quintile ofthe bal-anced pattern of consumption (mean: 72.6, SD: 8.27,

p=0.032).The ‘‘Western’’pattern showeda higherscore inthecategorywithmorethanoneriskfactorformetabolic syndrome(MS)inthegroupofgirls(mean:29.5,SD:1.37,

p=0.026).

In 2013, Shangetal.,17 when evaluating5267 children

and adolescents aged 6---13 years of age, found that the ‘‘Westernpattern’’wasassociatedwithahigherchanceof obesityandthatchildrenandadolescentswithhigherscores inthe‘‘Western’’and‘‘transition’’patternshadahigher chance of abdominal obesity. There was no association betweentheidentifieddietarypatternsandhypertension, hypertriglyceridemia,hypercholesterolemia, dyslipidemia, andMS.However,the‘‘Western’’patternhadhighermean values of weight, BMI, waist circumference, and systolic and diastolic pressure, and higher concentrations of glu-cose,LDL-c,andtriglycerides,andwasinverselyassociated withHDL-cconcentrationwhencomparedtothe‘‘healthy’’ pattern.

In 2012,Romero-Polvo etal.15 found that childrenand

adolescentswith‘‘Western’’foodpatternshada1.92-fold higher chance of insulin resistance. In 2011, Dishcheke-nian et al.9 found a positive association between the

‘‘transition’’ pattern, based predominantly on the con-sumptionof rice, pasta, beans,oil, red meats, processed

meats,andsweets,andincreasedconcentrationsofinsulin, glucose,triglycerides,anddiastolicbloodpressurelevels.In the‘‘fastfood’’pattern,theauthorsfoundapositive asso-ciation with the concentration of LDL-c, and systolic and diastolicblood pressurelevels,andanegativeassociation withHDL-c.

In 2010, Ambrosini et al.,7 when studying the

com-ponents of the metabolic syndrome (MS) in adolescents, divided their sample intotwo groups: high metabolic risk andlowmetabolicrisk,aimingtoinvestigatetheassociation betweendietarypatternandriskmarkersforMSand cardio-vasculardisease.Theauthorsobservedthatthe‘‘Western’’ patternwasassociatedwithincreasedriskofmetabolic syn-drome andits increasedcomponents, suchastotalserum cholesterol, BMI, and waist circumference among female adolescents.The‘‘healthy’’dietarypatternwasassociated withlowerglucoseconcentrationsinmaleandfemale ado-lescents.

In2007,Mikkiläetal.,18whenevaluatingthefoodintake

of children and adolescents in a cohort study, identified the‘‘traditional’’and‘‘health-conscious’’dietarypatterns. The second dietary pattern wasinversely associatedwith cardiovascularriskfactors;however,theresultssuggestthat this dietary pattern is more of an indicator of an overall healthylifestylethanjustadequatedietarychoices.

Discussion

The results of the studies showed a positive association between unhealthy eating patterns and cardiometabolic alterations.7---10,14---18However,itisimportanttounderstand

Table2 Confounding/interactionfactors,identifiedpatterns,andmainresultsoftheevaluatedarticles. Author/year Confounding/interaction

factors

Identifiedpatterns Mainresults

Appannah etal.,201510

Physicalactivity, smokingstatus,gender, age,dietary

underreporting

1.Energeticallydense. 2.Highinfat.

3.Poorinfiber.

Highscoresondietarypatternswereassociated withhigherchanceofbelongingtothehigh metabolicriskgroupforboys(OR:1.20,95%CI: 1.01---1.41),butnotforgirls(OR:1.03,95%CI: 0.87---1.22)whenadjustedforphysicalactivity andsmokingstatus.Higherscoresondietary patternswereassociatedwithhigherinsulin levels(FandM-:3.0,95%CI:1---7%)andHOMA-IR (FandM-:4.0,95%CI:1---7%)inbothgenders. Karatzietal.,

20148

Gender,breakfast consumption,pubertal stage,waist

circumference,parents’ BMI,socioeconomic status,birthweight, physicalactivity.

1.Friedpotatoes,red meat,andsweetened drinks.

2.Processedmeatsand cheese.

3.Margarine,sweets, andsavorysnacks. 4.Vegetablesandfruits. 5.Increasedegg consumptionandlower consumptionoffish.

Thedietarypatterncontainingmargarines, sweets,andsnackswaspositivelyassociatedwith HOMA-IR(ˇ=0.08;p=0.02)afteradjustmentfor confoundingfactors.Childrenwhohadhigher adherencetothiseatingpattern(consumptionin thehighesttertile)were2.51timesmorelikelyto haveinsulinresistancecomparedtochildrenin thefirsttertile(95%CI:1.30---4.90).

Bibilonietal., 201316

Age,physicalactivity, smoking,energyintake, BMI,WtHR.

1.Mediterraneandiet. 2.Westerndiet.

Westerndietscorewasinverselyrelatedto plasmaconcentrationsofadiponectinandIL-6 aftercontrolforpossibleconfoundingfactors (ˇ=−0.177,p<0.050andˇ=0.183,p<0.050, respectively)andwithadditionaladjustmentfor theBMIandWtHR(ˇ=−0.168,p=0.050and

ˇ=0.177,p<0.050,respectively). Parketal.,

201314

Age,gender,energy intake,height,blood pressure.

1.Balancedpattern. 2.Westernpattern.

Ingirls,themeanconcentrationoftriglycerides decreasedinthehighestconsumptionquintileof thebalancedpattern(mean:72.6,SD:8.27,

p=0.032).ThehighestscoreintheWestern patternwaspresentinthegirlswhohadmore thanoneriskfactorforMS(mean:29.5,SD:1.37,

p=0.026).Noassociationwasfoundforthemale gender.

Shangetal., 201217

Gender,age,birth weight,eatingprofilein the4thmonthafter birth,totalenergy intake,physicalactivity, parents’weight,levelof schooling,income.

1.Healthydietary pattern.

2.Transitionpattern. 3.Westernpattern.

Thefastingglucoselevelwashigherinthe westernfoodpatternthaninthehealthypattern (4.53mmol/Lvs.4.46mmol/L,p=0.0082). ChildrenwiththeWesternpatternhadhigher concentrationsofLDL-c(2.156mmol/Lvs.

2.07mmol/L,p=0.0023)andlowerHDL-c concentrations(p<0.001)comparedtothosewith thehealthypattern.ChildrenwiththeWestern patternprofilewere1.80times(95%CI: 1.15---2.81)morelikelytobeobesethanthosewiththe healthypattern.Transition(OR:1.31,95%CI: 1.09---1.56)andWestern(OR:1.71,95%CI: 1.13---2.56)foodpatternswereassociatedwith abdominalobesity.

Romero-Polvo etal.,201215

Gender,age,sexual maturation,BMI, physicalactivity,screen time,energyintake,use ofmedication,

supplements, multivitamins.

1.Westernpattern. 2.Prudentpattern. 3.Highprotein/fat consumptionpattern.

220 RochaNPetal.

Table2 (Continued)

Author/year Confounding/interaction factors

Identifiedpatterns Mainresults

Dishchekenian etal.,20119

Gender,age,ethnicity, income,maternal schooling,BMI.

1.Traditionalpattern. 2.Transitionpattern 3.Fastfoodpattern.

Thetraditionalpatternhadapositiveassociation withinsulin(ˇ=0.156,p<0.001),glycemia (ˇ=0.329,p=0.027),andTG(ˇ=0.513,

p<0.001),andnegativeassociationwith HDL-=−0.297;p=0.020)afteradjustingfor confoundingfactors.Thefastfoodpatternwas associatedwithinsulin(ˇ=0.176;p<0.001)when adjustedonlybygenderandethnicity.When adjustedbyincome,maternaleducation,and BMI,thispatternshowedapositiveassociation withLDL-c(ˇ=0.334,p<0.001),SBP(ˇ=0.469,

p<0.001),andDBP(ˇ=0.615,p<0.001),anda negativeonewithHDL-c(ˇ:−0.250,p<0.001). Ambrosini

etal.,20107

Gender,energyintake, physicalactivity,screen time,maternal schooling,parents’ maritalstatus,BMI,WC.

1.Westernpattern. 2.Healthypattern.

ThemeanBMIandWCdidnotvaryaccordingto thequartilesforeachdietarypattern.Forgirls, thechancesofmetabolicriskwereapproximately 2.5timeshigher(p<0.05;95%CI:1.05---5.98)in thehighestquartileofthe‘‘Western’’food patternwhencomparedtothelowest. Mikkiläetal.,

200718

Age,smokingstatus, totalenergy

consumption,smoking, physicalactivity,years offollow-upinthestudy.

1.Traditionalpattern. 2.Health-conscious pattern.

Thehealth-consciouspatternwasassociatedwith lowerriskfactors,butmainlyamongfemales.The levelsofTC(ˇ:−0.06,p=0.02),LDL-c(ˇ:−0.07,

p=0.01),ApoB(ˇ:−0.07,p=0.03),andCRP(ˇ: −0.09;=0.04)showedanegativeassociationwith thescoreofthehealth-consciouspatternin females,allaffectedbytheBMIinsertioninthe finalmodel.Additionally,thescoreofthe health-consciouspatternshowedanindependent inverseassociationwithhomocysteinelevels(F-ˇ: −0.11,p=0.03andM-ˇ:−0.14;p<0.01)inboth genders.

OR,oddsratio;ˇ,regression coefficientˇ; 95%CI,95%confidenceinterval;F,female;M,male;BMI,bodymassindex; WC,waist

circumference;HOMA-IR,homeostasismodelassessment---insulinresistance;WtHR,waisttoheightratio;TC,totalcholesterol;LDL-c,

low-densitylipoproteincholesterol;ApoB,apolipoproteinB;CRP,C-reactiveprotein;TG,triglycerides;HDL-c,high-densitylipoprotein

cholesterol;SBP,systolicbloodpressure;DBP,diastolicbloodpressure.

Theseresultsarenoteworthy,asseveralfactors associ-atedwithdietaryintakeandcardiometabolicalterations ---suchasincome, gender, age,birth weight, parentallevel ofschooling,physicalactivitylevel,andfoodavailabilityat home---mayaltertheassociationbetweendietanddisease, beingoftheutmostimportancetoevaluatethem.

The inability to identify positive associations between some risk factors and unhealthy foods in cross-sectional studiesmaybepartlyexplainedbychangesineatinghabits or dietary restrictions when body composition alterations alreadyexist in children/adolescents, such asoverweight andobesity,knownasreversecausality.11,19Anotherinability

toidentifypositiveassociationsisthefactthatestimating truedietaryintakeisoftencomplicated,asunderreporting mayoccur in records, whenthe information is forgotten. This inaccuracy makes it difficult to analyze energy and macro-andmicronutrient intake,aswell astheir associa-tionswithcardiometabolicalterations.20

Most of the studies identified the pattern charac-terized as unhealthy, consisting of the consumption of

ultraprocessedfoods,poorinfiberandrichinsodium,fat, andrefinedcarbohydrates.7---10,14---18

Itis observed thatthe high consumption offoods with higher energetic density, rich in fats and refined sugars, is directly associated to the increase of lipogenesis, the secretionofverylowdensitylipoproteins,andthereduced oxidationandgreateraccumulationoffattyacidsinthe tis-suesandblood.21Thesubstitutionoftraditionalandhealthy

foodconsumptionbyultraprocessedandready-to-eatfoods andbeveragesisassociatedwiththeincreaseinthe preva-lenceofoverweightandchronicdiseasesalreadypresentin pediatric patients.22,23 In contrast,adequate consumption

ofhealthyfoodshelpstoreducenutritionaldeficienciesand contributestothemaintenanceofbodyweightandthe pre-ventionofchronicdiseases,24thusitisessentialtostimulate

childrenandadolescentsnotonlyregardingthedaily con-sumptionofadequate foods,butalsothereductioninthe consumptionofultraprocessedfoods.

turn, consists in an exploratory method that uses multi-variate analysistechniques toextractdietary patterns. In thisapproach, the mostrelevant patternsofthe assessed populationareidentifiedfromcorrelationsbetweenthe col-lecteddatainthefoodsurveys.13,25Thisfoodconsumption

assessmentmethodologyallowsaddressingtheinteractions betweennutrients,food,andotherdietcomponents.

Dietary patterns offer a new approach in nutritional epidemiology,with results that can bemore easily trans-latedintoadviceforthepopulation,sincefood-orientated guidelinesaremoreeasilyinterpretedandpracticedbythe populationthannutrient-relatedones.18

Despitetheimportanceofstudieswithdietarypatterns, few studies were performed with children and adoles-cents. Some difficulties are reported, such as the need to evaluate food intake in the presence of parents and the fact that the diseases arenot yet established at this stage,whichdecreasestheinterestininvestigatinghealthy populations.5,10,25 Additionally, many cardiometabolic risk

factorsthatcanbeusedtoverifyassociationsbetweendiet anddiseasedonothaveestablishedcutoffsforchildrenand adolescents.5,6,26This iswhatoccurswiththedefinitionof

metabolicsyndrome,whichdoesnothavewell-established criteriatodate and, therefore,it is difficult toassess its realprevalenceinthepediatricpopulation.14,27

It canbeobserved thatsome risk markerswidely used in adultsare stillnot frequently assessed in children and adolescents,asisthecase ofC-reactiveprotein,thusitis necessary todefinecutoffs andtheir associationwith car-diometabolicalterationsintheearlystagesoflife.5

Therearealsolimitationsrelatedtotheinvestigationof foodconsumptioninrelationtothemethodsused,thelack oftoolvalidation,foodcompositiontablesthatfrequently donotincludetheanalyzedfoods,diversityinthe composi-tionofindustrializedproducts,theinterviewees’difficulty inmeasuringfoodandbeverageportions,aswellas under-reportingofthedata.9,28

Irrespectiveofthecomplexityofthisassociation, assess-ments of dietary patterns and other cardiometabolicrisk factors in children and adolescents shouldbe performed, sincethispopulationiseasilyinfluencedbytheenvironment inwhichtheylive,byfoodadvertisers,bypeers,family,and bytheadoptedsocioculturalvalues.9,17,29 Recognizingthat

the prevalence of overweight and obesity is increasingin developedanddevelopingcountries,andthatthisincrease in overweight has raised the economic costs of countries andthe familiesaffected bythe problem,informationon foodconsumptionandchangesincardiometabolicrisk fac-torsshouldalwaysbeevaluated.2,17,30

Somestudieshavedescribedthatchildhoodobesitycan induceearlychangesinmetabolism,leadingtodyslipidemia and glucose intolerance, in parallel with changes in the oxidative and inflammatory system, as well as the early onsetofobesity,whichmaydetermineamoresevere pro-inflammatoryphenotypethantheadultobesity.4,27,31

In2013,Bibilonietal.16 reportedthattheinflammatory

processexistsintheadiposetissueofobesechildren, repre-sentinganearlyalterationinhumans.Fromthisperspective, theidentificationandprevention,preferablyinchildhood, ofrisk factorsassociatedwithcardiometabolicalterations may be the best strategy toprevent the progression and involvementofotherundesirablehealtheffects.2

Becausedietisoneofthemodifiableandimportantrisk factorsin theetiology of chronic diseases, the identifica-tion of eating patterns characterized by consumption of ‘‘unhealthy’’ foods in childhood and adolescence can be usefulforthedevelopmentofstrategiesthatimprove eat-inghabitsand,consequently,reducetheprevalenceofthese riskfactorsthroughoutlife.7

The authors report that dietary patterns are specific to particular populations, since they may vary with gen-der,age,culture,ethnicity,socioeconomicstatus,andfood availability,anditisimportanttoanalyzethemindifferent groupstoverifytheiractualapplicability.9,11

The specificityof the population regardingthe typeof consumed dietary pattern, related to sociocultural char-acteristics,causesdifficultiesincomparisons,eventhough somesimilarities can beobserved.11,18 Therefore,caution

shouldbeexercisedwhencomparingthestudies,sincemany ofthemdiffer interms ofsample size,numberof follow-ups,statisticalmethods,andfoodconsumptionassessment methods.32

Conclusion

There was a positive association between ‘‘unhealthy’’ dietary patternsand cardiometabolicalterations by most studies with children and adolescents. Some associations that could not be confirmed may be related to the spe-cificdifficultyofevaluatingfoodconsumption.Somepoints shouldbe considered in assessing the diet-disease associ-ation, such as limitations of the selected dietary survey, incompletefoodcompositiontables,under-notificationsdue toomissionsorforgetfulness,andeventheneedforparental orcaregiverassistancetoprovidetheinformation.

Giventhecomplexityofthisassociation,itisimportant to evaluate the dietary patterns in different populations ofinterest,sincetheymayvaryaccordingtogender,age, availabilityoffoodathome,andsocioculturaldifferences, amongothers.Assimilarastheresultsmayseem,the com-parisonsandextrapolationsofthedatatootherpopulations areuncertain.

Studieswithdietarypatternsandtheirassociationswith cardiometabolicrisk factors should be performed in chil-drenandadolescents,sincetheprevalenceofobesityand associatedcomorbiditiesisincreasinginthispopulation,so thatearly interventionscanbeperformedwiththe objec-tiveofreducingshort-and-longtermhealthdamage,aswell as the reduction of costs involved in the care of health complications.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

222 RochaNPetal.

2.Funtikova AN, Navarro E, Bawaked RA, Fíto M, Schröder H. Impactofdietoncardiometabolichealthinchildrenand ado-lescents.NutrJ.2015;14:118.

3.Carolan E, Hogan AE, Corrigan M, Gaotswe G, O’Connell J, FoleyM,etal.Theimpactofchildhoodobesityon inflamma-tion,innateimmunecellfrequency,andmetabolicmicroRNA expression.JClinEndocrinolMetab.2014;99:474---8.

4.Oliver SR, Rosa JS, Milne GL, Pontello AM, Borntrager HL, Heydari S,et al. Increasedoxidative stress and altered sub-strate metabolism in obese children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5:436---44.

5.Tam CS, Clément K, Baur LA, Tordjman J. Obesity and low-grade inflammation: a pediatric perspective. Obes Rev. 2010;11:118---26.

6.Balagopal P, Ferranti SD, Cook S, Daniels SR, Gidding SS, HaymanLL, et al.Nontraditional riskfactorsand biomarkers forcardiovasculardisease:mechanistic,research,andclinical considerationsforyouth.Circulation.2011;123:2749---69.

7.AmbrosiniGL,HuangRC,MoriTA,HandsBP,O’SullivanTA,Klerk NH,etal.Dietarypatternsandmarkersforthemetabolic syn-drome inAustralian adolescents.NutrMetabCardiovasc Dis. 2010;20:274---83.

8.Karatzi K, Moschonis G, Barouti AA, Lionis C, Chrousos GP, ManiosY.Dietarypatternsandbreakfastconsumptionin rela-tiontoinsulinresistanceinchildren.TheHealthyGrowthStudy. PublicHealthNutr.2014;17:2790---7.

9.Dishchekenian VR, Escrivão MA, Palma D, Ancona-Lopez F, Araújo EA, Taddei JA. Padrões alimentares de adolescents obesos e diferentes repercussões metabólicas. Rev Nutr. 2011;24:17---29.

10.AppannahG,PotGK,HuangRC,OddyWH,BeilinLJ,MoriTA, etal.Identificationofadietarypatternassociatedwithgreater cardiometabolicriskinadolescence.NutrMetabCardiovascDis. 2015;25:643---50.

11.OellingrathIM, Svendsen MV,Brantsæter AL. Eatingpatterns and overweight in 9- to 10-year-old children in Telemark County, Norway: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:1272---9.

12.UrrútiaG,BonfillX.PRISMAdeclaration:aproposaltoimprove thepublicationofsystematicreviewsandmeta-analyses.Med Clin.2010;135:507---11.

13.CarvalhoCA,FonsêcaPC,NobreLN,PrioreSE,FranceschiniSC. Metodologiasdeidentificac¸ãodepadrõesalimentaresa poste-rioriemcrianc¸asbrasileiras: revisãosistemática.CienSaude Colet.2016;21:143---54.

14.ParkSJ,LeeSM,KimSM,LeeM.Genderspecificeffectofmajor dietarypatternsonthemetabolicsyndromeriskinKorean pre-pubertalchildren.NutrResPract.2013;7:139---45.

15.Romero-Polvo A, Denova-Gutiérrez E, Rivera-Paredez B, Casta˜nónS,Gallegos-CarrilloK,Halley-CastilloE,etal. Asso-ciation between dietary patterns and insulin resistance in mexicanchildrenand adolescents.AnnNutrMetab.2012;61: 142---50.

16.BibiloniMM,MaffeisC,LlompartI,PonsA,TurJA.Dietary fac-torsassociatedwithsubclinicalinflammationamonggirls.EurJ ClinNutr.2013;67:1264---70.

17.ShangX,LiY,LiuA,ZhangQ,HuX,DuS,etal.Dietarypattern anditsassociationwiththeprevalenceofobesityandrelated cardiometabolicriskfactorsamongChinesechildren.PLoSONE. 2012;7:e43183.

18.MikkiläV,RäsänenL,RaitakariOT,PietinenJMP,RönnemmaaT, ViikariJ.Majordietarypatternsandcardiovascularriskfactors fromchildhoodtoadulthood.TheCardiovascularRiskinYoung FinnsStudy.BrJNutr.2007;98:218---25.

19.BielemannRM,MottaJVS,MintemGC,HortaBL,GiganteDP. Consumodealimentosultraprocessadoseimpactonadietade adultosjovens.RevSaudePublica.2015;49:28.

20.Ambrosini GL, Emmett PM, Northstone K, Howe LD, Tilling K, JebbSA.Identification of a dietarypattern prospectively associatedwithincreasedadiposityduringchildhoodand ado-lescence.IntJObes.2012;36:1299---305.

21.RauberF,CampagnoloPD,HoffmanDJ,VitoloMR.Consumption ofultra-processedfoodproductsanditseffectsonchildren’s lipidprofiles:alongitudinalstudy.NutrMetabCardiovascDis. 2015;25:116---22.

22.Aranceta-BartrinaJ,Pérez-Rodrigo C.Determinantsof child-hoodobesity:ANIBESstudy.NutrHosp.2016;33:17---20.

23.SparrenbergerK,FriedrichRR,SchiffnerMD,SchuchI,Wagner MB.Ultra-processedfoodconsumptioninchildrenfromaBasic HealthUnit.JPediatr.2015;91:535---42.

24.Souza RL, Madruga SW, Gigante DP, Santos IS, Barros AJ, Assunc¸ãoMC.Padrões alimentaresefatoresassociadosentre crianc¸asdeumaseisanosdeummunicípiodoSuldoBrasil. CadSaudePublica.2013;29:2416---26.

25.Hoffmann K, Schulze MB, Schienkiewitz A, Nöthlings U, BoeingH. Application ofa new statisticalmethod to derive dietarypatternsinnutritionalepidemiology.AmJEpidemiol. 2004;159:935---44.

26.Cook DG, Mendall MA, Whincup PH, Carey IM, Ballam L, MorrisJE,etal.C-reactiveproteinconcentrationinchildren: relationshiptoadiposityandothercardiovascularriskfactors. Atherosclerosis.2000;149:139---50.

27.BarracoGM,LucianoR,SemeraroM,Prieto-HontoriaPL,Manco M.Recentlydiscoveredadipokinesandcardio-metabolic comor-biditiesinchildhoodobesity.IntJMolSci.2014;15:19760---76.

28.PierreLA,ZagoJN,MendesRC.Eficáciadosinquéritos alimenta-resnaavaliac¸ãodoconsumoalimentar.RevistaBrasileira de CienciadaSaúde.2015;19:91---100.

29.TeixeiraRC,CostaSP,OliveiraGV,CandidoFN,RafaelLM,Filho ML.Influênciadamídiaedasrelac¸õessociaisnaobesidadede escolares.Cinergis.2016;17:162---7.

30.CanelaDS,NovaesHM,LevyRB.Influênciadoexcessodepeso eobesidadenosgastosemsaúdenosdomicíliosbrasileiros.Cad SaudePublica.2015;31:2331---41.

31.Landgraf K, Rockstroh D, Wagner IV, Weise S, Tauscher R, SchwartzeJT,etal.Evidenceofearlyalterationsinadipose tis-suebiologyandfunctionanditsassociationwithobesity-related inflammation and insulin resistance in children. Diabetes. 2015;64:1249---61.