Health education and social representation:

an experience with the control of tegumentary

leishmaniasis in an endemic area

in Minas Gerais, Brazil

Educação em saúde e representações sociais:

uma experiência no controle da leishmaniose

tegumentar em área endêmica de Minas

Gerais, Brasil

1 Escola de Enfermagem, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brasil.

Correspondence

D. C. Reis

Escola de Enfermagem, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Av. Alfredo Balena 190, Belo Horizonte, MG 30130-100, Brasil. dener@enf.ufmg.br

Dener Carlos dos Reis 1 Andréa Gazzinelli 1

Carolina Angélica de Brito Silva 1 Maria Flávia Gazzinelli 1

Abstract

This study was developed in an endemic area of tegumentary leishmaniasis in Minas Gerais, Brazil, with the objective of analyzing a health education process based on the social represen-tations theory. The educational model was de-veloped in two phases with 34 local residents. In the first phase, social representations of leish-maniasis were identified and analyzed. The sec-ond phase was based on the interaction between social representations and scientific knowledge. The results showed that social representations were structured in a central core by the terms “wound” and “mosquito” and in the peripheral system by the terms “mountains”, “standing wa-ter”, and “injection” related respectively to place, transmission, and treatment of the disease. We concluded that tegumentary leishmaniasis is viewed as a wound caused by a mosquito, por-trayed by metaphors. The results of the second phase showed that social representations are systems that favor adherence to scientific knowl-edge, at times more rigidly in the central core, other times more flexibly when linked to the pe-ripheral systems.

Health Education; Educational Models; Leish-maniasis; Endemic Diseases

Introduction

In recent decades health education has shown new conceptual and methodological contours. It has shifted from a more empirical approach, based on the transmission of knowledge, to one with predominantly pedagogical strategies with participation and interaction of knowl-edge related to health and daily reality 1.

Currently, health education is a broad and systematized process with interaction of knowl-edge, aimed at allowing subjects to take a criti-cal and reflexive view that expands their deci-sion-making autonomy vis-à-vis health and dai-ly issues. In the field of health promotion, health education is considered one of the pillars for indi-vidual quality of life. Viewing it from this perspec-tive thus means linking social sciences and health sciences to its specific field of knowledge 2,3,4,5,6.

The current study aims to analyze the rela-tionship between a health education process based on social representations theory and the control of American tegumentary leishmania-sis (ATL) in an endemic area in the hinterlands of the State of Minas Gerais, Brazil. The study was based on the premise that learning occurs through an interaction between social repre-sentations – socially constructed knowledge governing the relationship between the subject and the world 7– and scientific knowledge.

information related to an object or situation. The subjects themselves (with their life history and experience), the social and ideological sys-tem to which they belong, and the nature of their links to this social system determine such representations simultaneously. This socially constructed and shared knowledge aims at pro-ducing answers to daily issues, exerting an in-fluence on the choices of subjects’ attitudes, opinions, and practices 7,8,9,10.

For a more in-depth understanding of so-cial representations, one must understand the theoretical and practical field known as social representations theory 10,11,12,13. To draw on

so-cial representations theory for an understand-ing of educational processes also means un-derstanding ways of thinking constructed dur-ing subjects’ life histories, thus influenced by collective experience, fragments of scientific theories, and schoolroom knowledge, partially expressed in social practice and mobilized and transformed to serve daily life 14,15,16.

Social representations theory has two main watersheds, one prioritizing the content of so-cial representations and the other their struc-ture, i.e., their organization in a central core (more rigid, homogeneous, and stable knowl-edge) and the peripheral system, a more flexi-ble, heterogeneous, unstable knowledge, more adaptive to the immediate context 14,15.

Understanding the organization of the con-tent of a social representation in its structures called the central core and peripheral system is fundamental for understanding how the knowl-edge-building process takes place on the basis of social representations. The theory states that in order to verify learning processes, it is nec-essary to identify at what levels changes in repre-sentations take place, whether they have reached the central core, and thus whether they have been incorporated more definitively into sub-jects’ mental structures, or whether mere desta-bilizations of the contents of representations have taken place at a more superficial level, whose more permanent alteration would thus require the creation of new conflictive situa-tions which would finally result in the modifi-cation or (re)construction of the subjects’ ini-tial representations 15.

The article thus proposes to reflect on the applicability of contributions by social repre-sentations theory to health education activities based on an actual experience with the control of tegumentary leishmaniasis in an endemic area in the State of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Methodology

The study adopted a qualitative approach, con-sisting of descriptive research using social rep-resentations theory as the theoretical and methodological reference.

The study was conducted in Brejo do Mu-tambal, an endemic area for tegumentary leish-maniasis, with prevalence rates of some 60%. The location is a district in the municipality (county) of Varzelândia, in northern Minas Ge-rais, Brazil. The entire region has environmen-tal characteristics favorable for endemic ATL, since it is surrounded by mountains with rock formations that serve as shelters for reservoirs of the disease: rodents, marsupials, anteaters, sloth, and other wild animals.

The overall schooling level is low, with a high proportion of the inhabitants either illit-erate or with incomplete primary education. Most of the population lives from subsistence family farming and a minimum government income program known as Bolsa-Família.

Thirty-four residents of Brejo do Mutambal participated, mostly ranging in age from 16 to 36 years, having agreed to participate voluntar-ily and anonymously after being informed of the research. Participant selection used ad-dresses of households with a history of ATL in the family. All participants signed a free in-formed consent form, in accordance with Min-istry of Health Ruling 196. The Institutional Re-view Board of the Federal University in Minas Gerais also approved the study.

Study design

The study was designed to link the health edu-cation process to the research work. It was im-plemented in two phases. The first phase had two purposes: furnish content for subsequent analysis and determination of social represen-tations and immediately create the education-al process by providing a space for reflection on themes related to experience with ATL. This phase was conducted individually with each participant. Three data collection instruments were used: (a) free association of ideas 14based

on the inductive term “leishmaniasis” with the aim of identifying and analyzing words or ex-pressions linked to ATL; (b) a questionnaire 17

human life cycle. This resource of guiding the interview with images has been used as a facil-itator for individuals with greater difficulty in answering the typical questions proposed in the interview 17.

The second phase included collective edu-cational moments approaching the social rep-resentations of ATL that had been identified by the researchers in the first phase.

The focus of this phase was interaction with scientific knowledge on ATL (place/disease rela-tionship, transmission, control, risk factors, pre-vention, and treatment). The technique used was to construct thematic panels containing images (photos) chosen by the participants on the themes related to the disease, which were then discussed with them.

The ambiguous scenarios technique 14,15was

used to evaluate the educational process. In this study, this technique played a double role: to test the centrality of social representations and to evaluate the (re)construction of knowl-edge by participants after the health education intervention. In this technique, the researchers reported that the central and core and periph-eral systems linked to ATL and identified in the first phase were questioned, thus observing whether the participants maintained these same representations.

All the data obtained in both phases were analyzed as proposed by Bardin 18for content,

together with the construction of “idea associ-ation maps” as proposed by Spink 19,20. Abric 11,12and Sá 13,14were our references for

analyz-ing the structure of the social representations in the central core and peripheral system.

Results and discussion

First phase: identifying representations of tegumentary leishmaniasis

The participants’ social representations of ATL were analyzed in three dimensions: cognitive, affective, and daily practice. The cognitive di-mension consists of progressively assimilating and accommodating knowledge within the subjects’ conceptual structure. The affective di-mension refers to the subject’s capacity to as-cribe a value to an object or space. The dimen-sion of daily practice involves habits, customs, and daily routines, linked to the “here” and “now” dictating what is relevant or irrelevant in daily life. Working with social representations assigned to different dimensions was impor-tant for the educational process, since they gave a multidimensional format to the content

approach (social representations). The empha-sis on interaction between different types of knowledge thus focused not only on cognition, but on the other dimensions as well, namely af-fectivity and daily practice.

Approaching the cognitive dimension of social representations

When asked to talk about the disease “leishma-niasis”, the village residents’ narratives revealed a wide range of expressions and adjectives, as shown in Table 1. These data resulted from an-alyzing the content obtained through free as-sociation of ideas based on the inductor “leish-maniasis” and the questionnaire containing as-pects related to ATL transmission, prevention, and treatment.

Table 1 shows that for each thematic cate-gory, specific terms and expressions emerged. To express the meaning of leishmaniasis, the interviewees referred to the term wound; when thinking about ATL transmission they men-tioned the word mosquito;they associated pre-vention of the disease with standing water; they mentioned injectionsas the way of treating the disease; for environmental conditions favoring the endemic they cited mountainsand pools of water. This signals that in general the intervie-wees were familiar with some aspects of the ATL transmission cycle, although they highlight “standing water”, which is not related to this disease’s mode of transmission.

As perceived by local residents, the terms “garbage”, “mountain range”, “water”, “ani-mals”, and “mosquito” are directly related to the disease’s transmission. When asked about ATL transmission, 39 different answers associ-ated it with the “mosquito”, in the local resi-dents’ own words. The fact that dengue is also mosquito-borne may have facilitated the in-corporation of knowledge that serves as an an-chor for new knowledge, but in this case linked to ATL.

schis-tosomiasis, and others and has been a highly recurrent theme in health education practices since the mid-20thcentury. By explaining the

disease by means of water accumulated in var-ious environments, the accent no longer falls on the true modes of transmission of disease, namely the mountain range, cited as harboring the vector insect and other animals.

In relation to the theme ATL treatment, res-idents used 38 expressions in the answers. Of these, 16 citations referred to the treatment as an injection (glucantime) as the only way of curing the wound caused by ATL, which is con-firmed by medical discourse. We observed that the fact that leishmaniasis treatment involves injections generates discomfort, concern, and

fear in the population. Knowing individuals with the disease and its implications is rarely limited to the immediate family. Intertwining networks of kinship and friendship unavoid-ably lead to the involvement of neighbors and relatives in the patient’s experience, either by providing support or transmitting stigma and information. Local residents thus always have a case of the disease in the village to tell about.

In relation to control and prevention, par-ticipants in the educational project represent-ed them in terms of “environmental practices”, quantitatively the most significant term, with 59 citations, followed by “measures related to the mosquito”, with 35 citations, and “immune [vaccine] prevention”, with seven citations. Table 1

Terms and expressions cited in the categories analyzed concerning interviewees’ level of knowledge about American tegumentary leishmaniasis (ATL).

Thematic category Terms and expressions most frequently cited by n interviewees according to thematic category

Meanings ascribed to tegumentary Wound 50

leishmaniasis Disease 22

Leishmaniasis 5

Transmission of tegumentary Mosquito 39

leishmaniasis Water 22

Animals 13

Do not know transmission mode 8

Mountains 6

Garbage 6

Treatment of tegumentary Injections 10

leishmaniasis Ointments 2

Pills 2

Herbal teas and medicinal plants 1

Vaccine 1

Benzathine penicillin 1

Measures for prevention and control Precautions with pooled or standing water 37 of tegumentary leishmaniasis Use poison [insecticide] to combat the mosquito 18

Use incineration and fumigation 13

Avoid proximity with the mountains 13

Precautions with garbage 9

Immunization against ATL in humans 5

Immunization of dogs against ATL 2

Use of mosquito nets 4

Not familiar with preventive measures 3

Local characteristics favoring Pooled or standing water 36

the endemic Mountains 34

Mosquitoes 17

Environmental practices associated with precautions with water, garbage, and the sur-rounding mountains were cited as the most important aspects for controlling the disease. Application of “poison [insecticide]” was cited as an important measure for reducing the in-sect population. Interestingly, other measures such as use of mosquito nets and long clothing to cover the body were rarely mentioned.

Many residents focused their representa-tions concerning control of the insect vector precisely on eliminating the mosquito through various household measures such as produc-ing smoke by burnproduc-ing various materials (ani-mal dung, eucalyptus leaves, rubber, etc.).

The residents spoke about the relationship between the place and the disease based on the coexistence of numerous surrounding moun-tains, inadequate storage of standing water, and mosquito populations. Far from being knowl-edge that provokes preventive responses, this notion of the mountains as the disease vector’s “habitat” leads to a feeling of powerlessness vis-à-vis control of the endemic, clearly seen in the following report: “I think it’s going to be dif-ficult to wipe out this disease here, because of the mountains, which is where the mosquitoes live. People will have to learn to live with the problem, cause there’s no way to wipe out the mountains”.

In the cognitive dimension, when asked to express what they think or feel when they hear about leishmaniasis, more than half of the resi-dents mentioned the term “wound”. The fact that a clinical manifestation of ATL is the de-velopment of skin or mucosal ulcers which are generally difficult to heal means that the dis-ease is recognized by its most obvious clinical manifestation, namely the “wound”. The objec-tification of the disease ATL is thus expressed in an image personified in a “wound” which possesses its own characteristics.

Thus, based on the narratives, the popula-tion used language to externalize the wound and the disease, full of meanings: “It started with a little lump, and that little lump grew, that hard lump, and then a wound broke out on my leg”. “The wounds are like little eyelets”. “It’s a wound that heals on the outside and gets worse on the inside”. “The wound goes deep and looks like a muzzle”. Local residents create such metaphors to express their perceptions and feelings. They engage others with the force of such evoked im-ages. Local residents thus use such metaphors to call on others to share their experience.

Since residents individually and collective-ly construct notions on the wound and share reactions, stories, and feelings, the disease gains

identity and is considered anomalous. This as-pect of identification and qualification of leish-maniasis confers a practicality to this knowl-edge, as proposed by Jodelet 7,

instrumentaliz-ing the community to identify new cases of leishmaniasis in the village.

Approaching the dimension of daily practice in social representations

The data presented in this dimension were ob-tained in the interview guided with images that approached the relationship between the dis-ease and local residents’ daily reality. Of the 34 participants in the study, 50% (17) stated that there was a risk of acquiring leishmaniasis while carrying out routine daily activities, including work in the fields, with 14 citations. Household activities were also identified as related to the disease, but with only three citations. Seven of the 34 participants claimed that there is no risk of acquiring the disease during routine daily activities.

More than half of the residents viewed the disease as something predictable for those who work in the fields, due to the proximity to the surrounding mountains, the habitat of the “mos-quito”. On the other hand, although to a lesser degree, some residents felt that work in the fields was not a risk factor for the disease, as at-tested by one resident: “That’s kind of hard [to catch the disease out in the fields], except if the person’s already sick, cause then there’s nothing better than working in the fields. No, the disease isn’t out there in the field, you have to be sick al-ready”.This discourse is elucidative and ap-pears to derive from a phenomenon of ratio-nalization. It contains an implicit attempt to attenuate the strong relationship between work environments and risk of acquiring the disease. The inference is supported by the fact that un-der various circumstances and when asked about the conditions responsible for transmis-sion of the disease, local residents pointed to the surrounding mountains and forests, as de-scribed above in this educational work.

Denial of the real possibility of acquiring the disease in daily practice appears to be linked to the fact that the place identified as entailing the greatest risk, “work in the fields”, is simultaneously a source of satisfaction for many of the local residents.

in-strumental function linked only to the pressing need for survival. It is not viewed only as a means, i.e., within a primarily utilitarian per-spective.

In our understanding health education pro-posals aimed at controlling endemic diseases should consider the dimensions of life linked to daily practice and human subjectivity, guar-anteeing the discussion of two important cate-gories, namely the notion of the disease’s risk and visibility.

Approaching the affective dimension of social representations

The data obtained from the interviews guided by images on the relationship between the dis-ease and the health/disdis-ease process and the re-lated stories about them in the local communi-ty (Brejo do Mutambal) provide the affective di-mension of this study. When the 34 participants were asked to talk about the place, 17 (50%) as-cribed a positive image to it, while the other 17 viewed it in a negative light.

The relationship between residents and the place is measured by value-based representa-tions and the construction of positive or nega-tive images about it, which in this particular study appear in an ambivalent way. The nega-tive images were related to adverse living con-ditions, lack of opportunities for social mobili-ty, lack of prospects for the children, and the precarious local infrastructure: “You know how hard our life is. I started working in the fields when I was ten and have been working there ever since. When I’m not working in the fields, I’m gathering kindling. Hauling all that kin-dling [pointing to a woodpile]on my head is nothing. I’ve been a widow for eleven years, just gathering the crumbs. Life is suffering”.

The result of all this is a feeling of discour-agement expressed by residents towards the community’s lack of prospects. Thus, experienc-ing and narratexperienc-ing their pain, the local residents rule out any possibility of making forecasts about their lives, as shown in the following tes-timony: “The drought, the lack of rain. The little rain that did fall all came at the wrong time. So with all the hardship, the dry years, things got out of hand and it was all dry here and people sold most of the land. The crops fell off and the time came when the drought got even worse. So the crops dried up all together. Like this year, when 60 to 70% of the crops were lost”.

While residents of Brejo do Mutambal iden-tify reasons for distress and suffering linked to living in a rural community, they also express several reasons for feeling fondness for the

place. Enjoying farm work is a point of attach-ment, as are the “kinship” they feel for the place and the roots they develop which further nour-ish this fondness.

A positive presence in the village is a net-work of friends. What apparently matters less is the residents’ social and economic condition, and what matters more is their affective be-longing to the community: “I can’t even explain it. I was born and raised here, and we get used to our own place. I think if we moved, we’d miss the place”.The feelings fostered by the place can certainly help define the residents’ behav-ior patterns towards their daily life. Thus, their fondness for the place can favor attitudes of re-fusal and denial towards anomalous phenome-na, such as diseases whose risk factors are spread around the various local environments. In the eyes of local residents, tegumentary leish-maniasis is both normal and abnormal, inte-grated and rejected. When residents were urged to talk about their hardships and main health problems, leishmaniasis appeared in metaphor-ical form when the residents made free, de-tailed, and extremely fertile associations be-tween the disease and various structures and animate and inanimate objects, to manifest their feelings of suffering, affliction, discom-fort, shame, and fear towards the disease.

In response to the way they related to the place and the disease, the trend could thus be to link determination, knowledge, and discern-ment in deliberate action towards the place. When implementing studies and proposals for intervention, to assume this as truth means recognizing the importance not only of reality, but the way it acquires new configurations in the subjective imaginary. We believe that to the extent that the disease is verbalized, told, and narrated, it gains identity within a specific con-text where the subjects establish relations. It is important to recall that with endemic diseases, the majority of control and prevention mea-sures depend on environmental interventions, i.e., depending heavily on collective attitudes that guarantee the restructuring of the envi-ronment and reflection on space.

Demarcating the central core and peripheral systems of social representations

cog-nitions in the subjects’ discourse, strong indi-cators of the centrality of this knowledge. Added to this approach were other analytical tech-niques such as symbolic value and connexity

11,12,14,15. Associative idea maps were also used,

as proposed by Spink 19.

Thus, when we analyze these terms, con-sidering the qualitative aspects or their sym-bolic value and associative power, “wound” and “mosquito” are again the ones that most serve this function, as compared to the terms “stand-ing water”, “mountains”, and “injection”, since it is through the terms “wound” and “mosqui-to” that all the others make sense, i.e., they guarantee a connection and an associative pow-er with the othpow-er tpow-erms, in addition to bearing a meaningful and symbolic value that best spec-ifies the meaning of leishmaniasis for the local residents.

We analyzed the potential of the term “wa-ter” to link and associate with other terms and observed that the same was not true for the terms “wound” and “mosquito”. However, al-though it is not part of the disease cycle, water proved to be important in the sense of anchor-ing information on other diseases and was per-sistent in the conceptual structure of many lo-cal residents, leading us to view this expression as possibly belonging to the peripheral system of social representations. Other less frequent terms like “mountains” and “injections” also failed to show the characteristics of centrality in the representation.

Second phase: interaction between social representations and scientific knowledge

This phase took place during collective mo-ments in a local public school. The distinguish-ing reference in this phase was to foster a dia-logue between the subjects’ social representa-tions and scientific knowledge on leishmaniasis. In this process, the subjects’ knowledge gaps, cognitive conflicts, and contradictory and/or equivocal notions were approached carefully, considering the premise that although social representations are sometimes ambiguous, in-coherent, and impregnated with common sense, they represent important mechanisms, cultur-ally developed by the members of a given social group to deal with diseases with which they are forced to live for a major portion of their lives.

During the educational moments, we ob-served that the expression “water” or “standing water” as a purported breeding site for the leish-maniasis vector persisted in numerous cita-tions, as occurred during the first phase of the process and was thus identified as responsible

for the endemic. The educator informed the group more than once that “standing water” is not a breeding site for the leishmaniasis insect vector, although it does serve as the habitat for various disease-causing microorganisms.

In relation to the animal reservoirs for the disease, the data from the second phase dif-fered very little from those in the first phase.

In relation to local characteristics favoring the endemic, during the second phase the resi-dents identified the “mountains” and “forests”. In their view these places pose the greatest risk of infection, followed by working in the fields and in the home. The result was the same as in the first phase. A discussion thus ensued with residents concerning ways to reduce the risk of acquiring ATL in these places, such as wearing long-sleeved clothing and trousers and using insect repellents on the face, hands, and feet. Again, it was not common for local participants to adopt such measures. It was thus necessary to evaluate them in terms of the possibility of incorporating them into daily habits, since they involved costs for the local population.

At the end of the educational work, the re-sults concerning the participants’ knowledge about measures for ATL control and prevention showed that in their view spraying insecticide and using mosquito nets were the more impor-tant measures for preventing the disease, thus appearing with most citations in their dis-course, unlike the first phase of the study, in which the participants identified environmen-tal measures as the most important, specifical-ly in relation to “standing water”. We attribute this change in representation to the fact that the residents participating in the educational process learned the knowledge that “water” is not a breeding site for ATL sand flies.

Evaluation of the educational activity based on social representations: changes in the central core and peripheral system

In order to verify whether there had been inter-action and reconstruction of knowledge relat-ed to leishmaniasis basrelat-ed on health relat-education grounded in social representations, it was nec-essary to define which evaluative instrument to use. The researchers considered the “am-biguous scenario” described by Sá 13an

and argue coherently, even when the cogni-tions linked to the central core are challenged. The researchers chose to discuss both the prob-able content of the central core, “wound” and “mosquito”, and that of the peripheral system, “water”, “injection”, and “mountains”.

This process was a collective activity during which each participant received a green card, which they raised when they agreed with the content of the scenario narrated by the educa-tor, and a red card when they disagreed with the reported scenario. They were then asked to justify their choices. The following illustrates an ambiguous scenario aimed at questioning mosquitoes as the vectors for ATL: “Here we are, with photos of people with ‘wounds’, but studies were done in this given place and they observed that none of them had been bitten by mosqui-toes. Do these people, who have wounds but weren’t bitten by mosquitoes, have ATL?”.

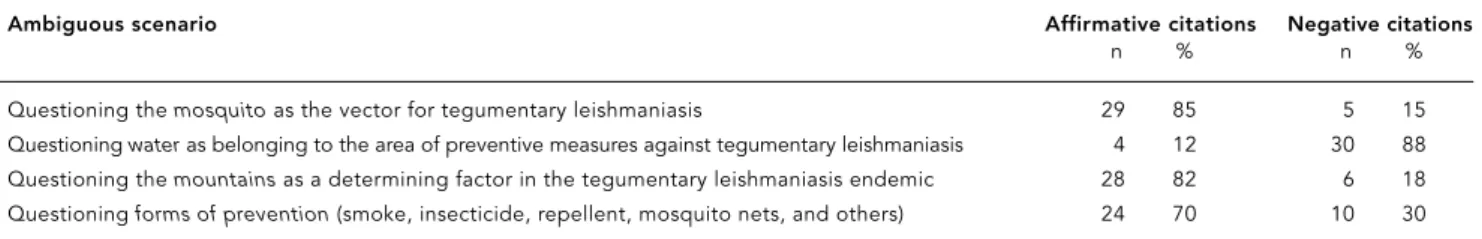

Table 2 shows the results of applying am-biguous scenarios to evaluate this educational activity based on representations of leishmani-asis. The most productive ambiguous scenario questioned standing water as a site for the mos-quito, showing once again that this knowledge was replaced after the interaction of knowledge. In other words, before the educational activity it was viewed as an integral part of the ATL transmission cycle, but this changed after the educational activity, confirming our inference that “standing water” belongs to the peripheral system of social representation, with flexibility as a characteristic.

The results appear to confirm the aspects comprising the central core of subjects’ repre-sentations, namely “wound” and “mosquito”. When questioned during the ambiguous sce-nario, they were reaffirmed as “unquestionable” information and always viewed as part of knowl-edge related to ATL.

When the term “mosquito” was questioned, 85% of the participants considered its presence

directly linked to the fact that the village had an ATL endemic. This knowledge is important since the majority of the individual and collec-tive measures focus on reduction of exposure to vector bites and combating the vector by ap-plying insecticide, among others aimed at re-duction of exposure to the vector and reduc-tion of the insect populareduc-tion.

During the ambiguous scenario question-ing the efficacy of individual and collective con-trol measures like use of mosquito nets, the par-ticipants confirmed (in 70% of the responses) that such measures are effective for the preven-tion and control of ATL. This observapreven-tion is in-teresting from the point of view of adopting measures for prevention and control, since it confirms that when control measures are well-based, their credibility increases and people accept them more readily.

Final remarks

Social representations are structured in a cen-tral core and peripheral system. Knowing this structure favors the health education process, identification of spaces for inflection, and the resistance of social representations. In other words, considering social representations for educational purposes in terms of content and structure creates the possibility of identifying not only the networks of meanings surround-ing an object, but also the visibility of possible spaces for its transformation.

In this case, health education allowed ques-tioning the peripheral system of representa-tions, opening room for new knowledge to be incorporated into the participants’ conceptual structure. Thus, based on the process, the rep-resentation that leishmaniasis is transmitted by standing water was replaced by the idea that the surrounding mountains and forests and ar-eas where animals are raised and where garbage

Table 2

Results of the evaluation of the educational activity and verification of the central core of social representation of tegumentary leishmaniasis by study participants.

Ambiguous scenario Affirmative citations Negative citations

n % n %

Questioning the mosquitoas the vector for tegumentary leishmaniasis 29 85 5 15

accumulates constitute the habitat for sand flies. In this teaching situation, the peripheral system proved to be receptive to scientific knowledge.

Health education based on social represen-tations allowed externalizing the central core of the representations, facilitating an under-standing by educators of the ways the residents view the disease and moments of reflection, (re)cognition, and recreation of relevant im-ages and representations by the residents. For the residents, leishmaniasis was not viewed as important, losing in order of priority to a series of other common diseases. It was described cognitively, affectively, and metaphorically, thereby revealing the place it occupies in indi-viduals’ lives by awakening emotions, fear of death, and feelings of affliction, concern, and shame.

In this educational activity, the content identified as belonging to the central core proved to be rigid and less receptive to scientif-ic knowledge; however, we observed that scien-tific knowledge impacted the network of mean-ings comprising the central core of representa-tions. Thus, after the development of health education, the representation of “mosquito” as the vector of ATL remained as part of the cen-tral nucleus. However, while it was previously

confused with the dengue mosquito vector, the sand fly gained its own characteristics, distin-guishing it from the initial representation.

The evaluation process in this study was limited in time, and more effective conclusions concerning the interaction between subjects’ social representations and scientific knowledge would require a more long-term process evalu-ation aimed at verifying whether the conceptual alterations persisted over time. The researchers are thus developing other studies to evaluate whether these alterations are consistent or merely reflect the results of sporadic exposure to the educational discourse.

In operational terms, an educational process based on social representations requires greater time, since it involves two phases and demands substantial investment in the production of ed-ucational materials. In addition, its applicabili-ty should not be generalized; thus, a particular health education proposal should be devel-oped for each specific group of people.

Finally, educational work based on social representations of the disease can be repro-duced for other endemic diseases and social-interest themes to verify the possibility of in-creasingly incorporating and integrating the referential framework of social representations into the health education field.

Contributors

D. C. Reis participated in the study design and imple-mentation, conducted the data analysis, and pro-duced the main draft of the article. M. F. Gazzinelli supervised the study and participated in its imple-mentation, the data analysis, and drafting of the arti-cle. A. Gazzinelli participated in the data collection and reviewed the manuscript. C. A. B. Silva partici-pated in the study implementation.

Resumo

Desenvolvido em uma área endêmica em leishmanio-se tegumentar, zona rural de Minas Gerais, Brasil, este estudo pretendeu analisar um processo educacional em saúde fundamentado na Teoria das Representa-ções Sociais. Este modelo educativo foi desenvolvido em duas fases e destinado a 34 moradores da locali-dade. Na primeira fase, foram identificadas e analisa-das as representações sociais vinculaanalisa-das à doença. A segunda fase consistiu na interação entre as represen-tações sociais e o conhecimento científico. Os resulta-dos da primeira fase identificaram que as represen-tações sociais estavam estruturadas no núcleo central pelos termos “ferida” e “mosquito”, e no sistema peri-férico pelos termos “serra”, “água parada” e “injeção” relacionados, respectivamente, a lugar, transmissão e tratamento da doença. Para os pesquisados, a leish-maniose tegumentar se personifica em uma ferida do mosquito permeada de metáforas. Os resultados da se-gunda fase mostraram que as representações sociais são sistemas favoráveis ao “acolhimento” do conheci-mento científico, ora mais resistente, quando ligado ao núcleo central, e ora mais flexível, quando ligado ao sistema periférico.

References

1. Gazzinelli MFA, Gazzinelli RV, Santos LAO, Gon-çalves R. A interdição da doença: uma construção cultural da esquistossomose em área endêmica de Minas Gerais, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública 2002; 18:1629-38.

2. Buss PM. Promoção da saúde e qualidade de vi-da. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva 2000; 5:163-77. 3. Buss PM, organizador. Promoção da saúde e a

saúde pública. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Oswaldo Cruz; 1998.

4. Struchiner M, Schall V. Educação em saúde: no-vas perspectino-vas. Cad Saúde Pública 1999; 15:4-5. 5. Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health be-havior and health education: theory, research and practice. 3rdEd. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. 6. Gazzinelli MF, Gazzinelli A, Reis DC, Penna CMM. Educação em saúde: conhecimentos, representa-ções sociais e experiência com a doença. Cad Saúde Pública 2005; 21:200-6.

7. Jodelet D, organizador. As representações sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Eduerj; 2001.

8. Moscovci S. A representação social da psicaná-lise. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Editor; 1978. 9. Moscovici S. Das representações coletivas às

re-presentações sociais: elementos para uma histó-ria. In: Jodelet D, organizador. As representações sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Eduerj; 2001. p. 45-66. 10. Moscovici S. Representações sociais:

investiga-ções em psicologia social. Petrópolis: Editora Vo-zes; 2003.

11. Abric JC. Abordagem estrutural das representa-ções sociais. In: Moreira ASP, Oliveira DC, organi-zadores. Estudos interdisciplinares de represen-tação social. Goiânia: Editora AB; 1998. p. 27-37.

12. Abric JC. O estudo experimental das represen-tações sociais. In: Jodelet D, organizador. As re-presentações sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Eduerj; 2001. p. 155-72.

13. Sá CP. A construção do objeto de pesquisa em representações sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Eduerj; 1998.

14. Sá CP. Núcleo central das representações sociais. 2aEd. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes; 2002.

15. Campos PHF, Loureiro MCS, organizadores. Re-presentações sociais e práticas educativas. Goiâ-nia: Editora UCG; 2003. (Série Didática, 8). 16. Madeira M. Representações sociais e educação:

importância teórico-metodológico de uma rela-ção. In: Moreira MSP, organizador. Representa-ções sociais: teoria e prática. João Pessoa: Editora Universitária; 2001. p. 123-46.

17. Anadon M, Machado PB. Reflexões teórico-meto-dológicas sobre as representações sociais. Sal-vador: Editora UNEB; 2001.

18. Bardin L. Análise de conteúdo. Lisboa: Edições 70; 1991.

19. Spink MJ. Desvendando as teorias implícitas: uma metodologia de análises das representações soci-ais. In: Guareschi P, Jovchelovitch S, organiza-dores. Textos em representações sociais. 4aEd. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes; 1998. p. 117-45. 20. Spink MJ, organizadora. Práticas discursivas e

produção de sentido no cotidiano: aproximações teóricas e metodológicas. 2aEd. São Paulo: Cortez Editora; 2000.

Submitted on 18/Nov/2004