A Work Project, presented as part of the requirements for the Award of a Masters Degree in Management from the NOVA – School of Business and Economics.

How can sponsoring of sports teams influence healthy eating on children?

Miguel Maria de Noronha Lopes e Silva Marques, 1712

A Project carried out on the Children Consumer Behaviour Field Lab, under the supervision of: Professor Luísa Agante

Table of Contents

Abstract ... 3

Introduction ... 4

Literature Review and Research Questions ... 5

Sponsorship and Sports Sponsoring ... 5

Children Cognitive and Social Development ... 7

Sponsorship and Brands’ influence on children eating habits ... 8

Research Questions ... 10

Methodology ... 11

Legal and Ethical Issues ... 11

Sample ... 11

Research Design ... 12

Procedure ... 14

Measures ... 15

Results ... 17

Knowledge and Attitudes towards the Brand and the Product ... 18

Behaviour ... 20

Attitudes towards Healthy Eating ... 20

Understanding the Persuasive Intent ... 21

Discussion and Implications ... 23

Knowledge and Attitudes towards the Brand and the Product ... 23

Behaviour ... 24

Attitudes towards Healthy Eating ... 25

Understanding the Persuasive Intent ... 26

Limitations and Future Research ... 27

3

How can sponsoring of sports teams influence healthy eating on children?

Abstract

This research aims to evaluate the impact of sports sponsorship of a healthy food brand

(Mimosa) on children’s eating habits and on their consumer behavior. While previous research on sponsorship was mainly focused on measuring its’ effects on middle-aged

adults, our study targeted children between 7 and 11 years old. Through a structured

questionnaire responded by a sample of 136 children, we were able to measure their

knowledge and attitudes towards the brand and the product, their perception about the

persuasive intent of the sponsor and their behavior and attitudes towards healthy eating.

Our results suggest that although children already have some knowledge and attitudes

towards healthy brands as well as indications about caring about their eating behavior, that

does not seem to be triggered by the sponsor. Moreover, they do not appear to understand

yet the persuasive intent of the sponsor at these ages.

4

Introduction

Companies are nowadays using sports sponsorships as an effective marketing strategy to

reach a wide variety of consumers that are passionate about sports events/teams or who

have a particular interest in a specific sport. In the United States, sponsorship expenditures

have registered a significant increase from $8.5 billion in 2002 (Mason, 2005) to $19.8

billion in 2013 (IEG, 2014). The challenge for sponsors is to create emotional bonds with

fans, by understanding their emotions and showing that they are bringing value for their

team or for the sport. Furthermore, it is more and more common for companies in the food market to promote their products to young people. Food brands can influence children’s

choices and, therefore, their eating habits; and unhealthy food brands usually have a greater impact on children’s decisions. In fact, there is a high proportion of sponsors with the

potential for promoting products that may threaten health (Maher et al., 2006). Therefore,

when brands are sponsoring sports events/teams, they are actually inducing children to

consume their unhealthy products and triggering a wrong idea about what is healthier.

While sponsors may argue that they are not intentionally targeting children, it is clear that

they are potentially making children confused about what is a healthy lifestyle. Having in

mind that there are 35 million children playing organized/federated sports1, sports

sponsorship can be an ideal vehicle for health promotion companies to reach a younger

audience, by taking advantage of the high connection between children and sports. Thus,

the purpose of this research is to study if healthy food brands can have the same impact that unhealthy food brands already have in influencing children’s eating habits. This could also

5 help to gain a better understanding of the impact of sport sponsorship over children’s eating

habits. As so, this research aims to answer to the following research question: “How can sponsoring of sports teams influence healthy eating on children?”.

Literature Review and Research Questions

Sponsorship and Sports SponsoringAccording to Cornwell and Maignan (1998), Sponsoring is considered to be a distinct channel that complements a firm’s marketing communication program. In fact, by

comparing the annual growth between advertising, marketing/promotions and sponsorship

in North American countries, we can note that since 2011, sponsorship has been growing

more than both advertising and marketing/promotion (IEG, 2014). The same source also

refers that North American companies are expected to spend approximately $20.6 Billion in

2014, which represents a significant growth compared with the previous year of 2013

($19.8 Billion). That shows us the importance that nowadays sponsorship has to companies.

In a global scale, we can also observe that total global sponsorship spending is increasing in

the past few years and is expected to reach a value of $55.3 Billion in 2014, which

represents a growth of 4.1% over 2013. As a result of sponsorship, Jensen and Hsu (2011)

states that companies who invest significantly in sponsorship usually get better business

results, which are almost always above market averages. Moreover, in comparison with

advertising, sponsorship is viewed as less expensive and is often more accepted by the

public because it is more indirect and builds public goodwill towards the company (Mason,

6 on building a solid partnership2. As so, “sponsorship is a long-term investment, demanding

time and effort from the sponsor to achieve consumer awareness of the sponsorship link

and to convince the target audience of its sincerity and goodwill” (Walraven et al., 2014:

142). However, the link between sponsorship awareness and the affinity for the brand does

not occur instantaneously (Walraven et al., 2014). Wakefield and Bennett (2010) consider

sponsorship awareness as a necessary and important prior step to assess further conclusions

on sponsorship effectiveness. Nevertheless, sponsorship effectiveness (or ineffectiveness) is

preceded by a process that involves an image transfer from the sponsor to the consumers

(Gwinner and Eaton, 1999) and the creation of a positive attitude towards the sponsor

(Gwinner and Swanson, 2003). The effectiveness of a sponsorship will be verified if consumers’ willingness to purchase the sponsor’s products is higher (Tsiotsou and

Alexandris, 2009). Another important topic about sponsorship that usually causes some

discussion between researchers is related with its objectives. Shank (1999) considered that

they are different from those associated to advertising and are divided into direct and

indirect objectives. On one hand, the direct objectives focus on short-term consumer behaviour and on sales’ growth. On the other hand, in spite of latterly leading to an increase

in sales, indirect objectives focus more on creating brand awareness and to develop the reputation and image of the brand. In addition, consumer’s awareness tends to increase over

the years wherein the biggest increase is registered in the second year of sponsorship

(Walraven et al., 2014). Recent studies refer that corporate sponsorship is nowadays the

fastest growing type of marketing in the United States (Khale and Riley, 2004), which

2 http://www.sponsorship.com

7 clearly shows the potential of this strategy. It can have an impact in several dimensions,

such as Entertainment, Causes, Arts and other events. However, the most relevant is sport.

According to Shank (1999), Sports sponsorship refers to a marketing strategy of investing

in a sports entity (athlete, league, team or event) to support overall organizational

objectives, marketing goals and/or promotional strategies. Sports sponsorship can actually

link the aspiration and passion of a target audience to specific sports. Additionally, the

concept is one of the best means to build sustainable and livelong bonds with consumers

(Buchan, 2006). And this is crucial for companies who want to hold an effective and

efficient position in the marketplace. Over the past decades, Sports sponsorship is found to

be not only a fundamental part of the marketing mix communication of sponsors, but also

an important source of income for sponsored corporations. Researchers believe that it is an efficient mechanism to increase companies’ brand image and prestige (Amis et al., 1999).

Moreover, it can also help companies to differentiate from competition and create a

competitive advantage. Experts predict that in 2014, sports sponsorship will represent 70%

of the North American Sponsorship market, which is associated to a total spending of

$14.35 Billion (IEG, 2014).

Children Cognitive and Social Development

This study will target children between 7-11 years old, which are already in the concrete

operational stage of the well-known theory of cognitive and social development suggested

by Piaget. John (1999) argues that in this phase, children are able to think more abstractly

and to react to different stimulus in a thoughtful way. Moreover, they can focus on multiple

8 rationally. Selman (1980) states that during this phase children go through two distinct but

important stages. The first one is the social informational role taking stage (between 6-8 years old), in which children begin to recognize others’ different perspectives and opinions,

but do not even consider them. The second one is the self-reflective role taking stages

(between 8-10 years old), that differs from the previous one due to the fact that children are more predisposed to think and analyze others’ points of view. It is also somewhere between

their 7 and 8 years old that children start to understand the persuasive intent of advertising,

by recognizing for example, the explicit purpose of commercials of influencing consumers

to purchase something (Blosser and Roberts, 1985). Some consider advertising for children

as an unfair advantage, once they still have little understanding of the persuasive intent of

advertising, despite developing new information processing abilities (Blatt et al., 1972). Besides that, Children’s brand awareness also begins to be developed in this stage as kids

show much more perception about prices and product categories (John, 1999).

Sponsorship and Brands’ influence on children eating habits

Children’s dietary behaviour is usually influenced in several ways. Through their family,

peers and other social factors, children are induced to eat according to what they use to choose. In fact, through their behaviours, attitudes and choice of home meals’ structure,

parents are considered to be the most powerful influence on children’s nutrition

(Patrick and Nicklas, 2005). Furthermore, peers are also likely to influence eating patterns

during childhood (Salvy et al., 2012), mainly because those are the ones whom they interact

and spend more hours with (Rubin et al., 1998). Nevertheless, experts still agree that brands’ advertising can also have an impact on children’s eating habits, once they can

9 easily associate brands to the food that they eat (Hastings et al., 2006). In fact, previous

studies by Hastings et al. (2006) refer that food promotion is the marketing category that

invests the most in targeting children. In addition, most of the products promoted are considered as “unhealthy”, since they contain high fat, sugar and high salt ingredients that

go against the guidelines suggested by the International Dairy Foods Association (IDFA)3.

Evidences also show that there are little promotion of foods that encourage children to

consume products that offer a healthy eating profile, like fruits, vegetables, grains, dairy

products and low fat meat (Story et al., 2008). Besides that, the evidence that food promotion of “unhealthy” products is able to influence children nutrition knowledge, food

preferences and consumption patterns worsens the situation, especially when allied to the fact that children have enough power to influence their parents’ buying decisions (Hastings

et al., 2006). As seen before, food brands can promote their products through several

marketing tools, such as sports sponsorships. Maher et al. (2006) found out that sports

sponsorships related with unhealthy products are more common than sponsorships related

with healthy products. And this shows a clear dominance of unhealthy food sponsorship

over healthy food, particularly targeting junior players and teams. Another important aspect

is related with the effectiveness of sports sponsorships to influence children. Pettigrew et al.

(2013) refer that there is enough evidence to conclude that through sponsorships, brands

can actually reach younger audiences. Through a research undertaken by Kelly et al. (2013)

in collaboration with the Cancer Council NSW and the Prevention Research Collaboration

of the University of Sydney, experts discovered that usually sponsorship of sports is mainly

10 done by unhealthy food brands that succeed to influence children’s attitudes towards their

unhealthy products. The authors say that it can even induce children to misunderstand that eating unhealthy products after doing sports is good for their health. In the food companies’

point of view, it is very attractive for them to invest in children sports sponsorship, since

kids have a lot of bargaining power with their parents and can influence their spending in a

relatively easy way (Stead et al., 2003). Moreover, kids nowadays have already a

considerable personal spending of their own and have their entire lifetime of spending still

to come. Finally, food companies can take advantage of sponsoring young teams, by

creating a connection with both parents and children in order to induce them to enter in

their establishments and consuming their products (Maher et al., 2006).

Research Questions

After reviewing previous studies and their main findings, there are four main questions that

this research aims to answer. The first question will test the knowledge and attitudes of kids

towards the sponsor (brand) and the product. The second question will analyze if it is

actually possible that children change their eating behaviour through sponsorship. The third one will measure children’s attitudes towards healthy eating, by trying to understand if they

express their intentions of having better eating habits. Finally, the last question will try to

find out if kids understand the persuasive intent of the brand that is sponsoring their team.

Thereby, this study aims to respond to the following research questions:

RQ1: Can healthy food brands attract and create affinity with children through sports sponsorship?

(Knowledge and Attitudes towards the Brand and the Product)

11

RQ3: Do children express their intent and recognize the importance of having healthy eating habits, through

sports sponsoring? (Attitudes towards Healthy Eating)

RQ4: Do children perceive the intent of the sponsoring brand? Does it affect the way they are influenced by

the sponsoring? (Understanding the Persuasive Intent)

Methodology

Legal and Ethical Issues

This research strictly respected all the legal and ethical directives recommended by

UNICEF (2002) that guarantee the protection of children rights. Therefore, all the

questionnaires conducted were anonymous in order to make children comfortable to answer

without pressure to what was asked. They were also aware about the non-existence of right

or wrong answers and given the possibility of choosing not to respond to the

questionnaires. Moreover, both parents, children and sports teams were clearly informed

about the purpose of the study, methods used and principles of confidentiality followed. As

so, their consent to gather information through this questionnaire was also achieved.

Sample

As previously mentioned, the target of this research are children between 7 and 11 years

old. We choose for this research Rugby teams from the district of Lisbon4, and the study

only targeted boys and no girls. In fact, despite children’s overall food preferences are not

consistent with a healthy dietetic profile, girls are usually more concerned with their food

choices and tend to have better eating habits than boys (Cooke and Wardle, 2005). On one

4Despite being a sport that requires some physical contact for children at these ages (Gabbett, 2002), Rugby

also contributes for the development of psychological skills. Due to its relative degree of complexity, it stimulates intelligence and helps children to expand their knowledge capabilities. In addition, Rugby provides important values and teachings that remain for life, such as self-discipline, fair play, sportsmanship and social interaction http://www.rfu.com/thegame/corevalues

12 side, girls prefer fruit and vegetables more than boys do. On the other side, boys are more

likely to choose over fatty and sugary foods (Robinson and Thomas, 2004). As so, we

found that it could be interesting and more appropriate to apply this research only to boys,

who generally have less healthful food preferences than girls at these ages and need to

change and improve their eating habits (Cooke and Wardle, 2005). A total of 136 boys who

play Rugby at least twice a week and belong to the under-10 and under-12 teams

participated in the research.

Research Design

This study used questionnaires as a method to conduct the research. In order to effectively

reduce method biases, we applied some procedures that could control their effects (Podsakoff et al., 2003). To guarantee children’s honesty, it was explicitly explained that

there were no right or wrong answers. In addition, the questionnaire contained simple questions with easy wording, to facilitate children’s comprehension and avoid ambiguity

(Tourangeau et al., 2000). Finally, in order to make children feel motivated and willing to

respond to questionnaires, the anonymity of their answers was assured.

The research was an experiment, using a fictitious case where a healthy food brand would

sponsor several children Rugby teams. Hence, it was necessary to choose a brand that could

be recognized and known by kids (which is difficult due to the low involvement between

children and food – Alvensleben et al., 1997), and also associated with a healthy dietary

profile. In order to choose the brands, a qualified nutritionist5 gave her opinion about some

familiar examples that could be considered healthy brands. Based on her experience with

13 children at these ages, she preferably advised cereals, dairy products (milk and yogurt) and

fish related products. As so, a sort list of brands was selected: Nestlé, Danone, Vigor,

Mimosa, Pescanova and Iglo. This subset of brands was pre-tested with 7 children to select

the one that would be more familiar to children and considered as healthier by them. The

pre-test procedure was adapted from an experiment conducted by Achenreiner and John

(2003). Firstly, they were requested to choose the brands they knew from those presented,

and afterwards, they should pick the ones they liked the most from those they had chosen

before. Finally, they had to select and rank the three brands that they considered healthier.

The final chosen brand would be the one that was chosen the most in the first two questions

and ranked better in the third question. Thus, the brand selected was Mimosa. Mimosa is a

well-known Portuguese brand that offers a wide variety and range of dairy products that

meet the needs of the different stages of children growth. Furthermore, Mimosa´s products

seek to set a commitment between flavor and nutritional balance6. Some of Mimosa´s

products, like milk and yogurts, are fundamental to protect children’s organism against

diseases and to reinforce their health7. On one hand, milk has an unequaled nutritional wealth since it provides important nutrients for children’s organism such has proteins,

carbohydrates and calcium. On the other hand, yogurts offer the same nutrients as milk, as

well as probiotics and antioxidants that regulate the intestinal flora. In addition, yogurts are

a good alternative to children that are intolerant to lactose and support less concentrated

products better.

6

www.mimosa.com.pt 7 Dra. Ana Mendes de Almeida

14 Afterwards, we focused on developing the stimulus to be shown to kids that would

represent the sponsorship. In other words, to decide about the type of sponsorship that

should be applied. After analyzing some possibilities, it was decided that Mimosa would

sponsor the chosen Rugby teams by fictitiously placing its logo in their shirts. Additionally,

it would also be the main sponsor of the teams, which means it would be placed in the

center and front of the shirts. According to Achenreiner and John (2003), children become

more consciousness and familiar with the brand when the brand name or logo is more

visible and exposed in advertising, clothes and uniforms and among their peers.

Procedure

A main study was conducted in order to assess the validity of the proposed research

questions. As so, children from all the Rugby teams were divided into two groups: an

Experimental group, where they were subject to the variable controlled (treatment effect)

and a Control group, where they do not receive any stimulus. The stimulus for this main study was an image where children could see their “new” team shirt, in which was placed

the brand logo in the front and center (Figure 1). Each team had its own colored shirt with their team logo (so that children could easily associate to its team colors), but for all of

them the brand logo was the same. This process was

different for each group. Respondents belonging to the

Experimental group were given the possibility to observe

the image with the “new” shirt and then respond to the

questionnaire, while respondents of the Control group

15 were only able to see the brand logo first and then answer to the questionnaire.

Measures

In order to select the suitable scales to apply, previous studies and surveys that followed

similar procedures as this one were taken into account. Regarding the knowledge and

attitudes towards the brand and the product, we asked five questions to children in the experimental group, using a 5-point semantic scale with five differential items. This scale

was based on the one used by Dixon et al. (2007). The first question asked if children knew the brand that was represented on the shirt (from 1=”Unfamiliar” to 5=”Familiar”). In the

second question, we asked them what they thought about the brand that was on their team shirt (from 1=”I hate it” to 5=”I love it”). The third question asked them about their opinion

regarding the logo of the brand (from 1=”Not Cool at all” to 5=”Very Cool”). The fourth

question asked children if they like the products of the brand (from 1=”I Don’t Like” to 5=”I Like”). Finally, in the fifth question, they were asked about the taste of the products

(from 1=”Tastes Bad” to 5=”Tastes Good”). Questions asked to children in the control

group were mainly the same, but some wording had to be changed since children were

requested to observe only Mimosa logo and did not see the image of the shirt. In order to

measure if children understood the persuasive intent of the brand, only the Experimental

group was used, since their answers had to be answered according to the stimulus given by

the specific brand. Therefore, two questions were asked to children. In the first one, they

were required to identify the source of the brand logo on the team shirt. This question was

adapted from Oates et al. (2003) and also used in Simões and Agante (2014). Within the

16 from their team, the person doing the study and “Other” source. Children had to choose

only one and would be aware of the persuasive intent of the brand if they would select the

brand logo as the source. In the second question, children were asked to try to guess what

the source that placed the brand logo on the shirt wanted them to do. This question was

designed based on previous experiments conducted by Carter et al. (2011), Donohue et al.

(1980) and Macklin (1987). Four labeled pictures were shown and the possibilities of choice were: “Play Rugby better”; “Buy the brand products”; “Buy the new shirt” and

“Other”. Again, they were required to choose only one picture. It is important to make clear

that the right choice would be “Buy the brand products”, once it was supposed to measure

children’s perceptions about the buying intent of the brand. To test possible changes in

consumer behaviour affected by the sponsorship, again both Experimental and Control

Groups were considered. Relying on the procedure used by Goldberg et al. (1978), children

were requested to imagine a situation where their parents went to work and asked the

investigator to take care of them. And, since he did not know what children were supposed

to eat, they could choose what they want. In the first question, six pictures with three

healthy products and three unhealthy products were shown. They were asked to choose

only three of those products. In the second question, six other pictures were shown,

containing three different healthy products and three unhealthy products. Again, children

were asked to imagine the same situation for the next day and shall pick only three products. A new variable was created to measure children’s behaviour regarding healthy

products, which corresponded to the sum of all selected healthy food items. Children’s

choice would be considered as healthier if they chose three or more healthy products. The

17 same procedure was applied for children that belong to the Control Group. Lastly, to

measure children’s attitudes towards healthy eating, both Experimental and Control

Groups were considered. The procedure was adapted from a previous experiment carried

out by Sangperm et al. (2008) and from a report research published by the Foods Standard

Agency (2007). This variable was measured by using a 5-point Likert scale (from 1=”Completely Disagree” to 5=”Completely Agree”) with 5 items: “Eating healthily is very

important to me”; “Fast food and ready-made meals are not that bad for me”; Eating

healthy food will help me grow and become healthier”; “I plan to eat more healthy products (vegetables, fruit, milk and yogurts) from now on” and “I intend to eat more healthy

products (vegetables, fruit, milk and yogurts) from now on”.

Results

This study was conducted with 136 Portuguese boys from five different Rugby clubs

belonging to the district of Lisbon. In order to cover our target ages, we used to age ranges,

the under-10 boys (7-9 years old), and the under-12’s (10-11 years old). All of them were

equally distributed by stimuli (53.7% or 73 boys for the Control Group and 46.3% or 63

boys for the Experimental Group). To analyze the information gathered from the

questionnaires, we used the statistical program SPSS Statistics 22. Moreover, all tests

performed in this experiment were both parametric and non-parametric. On the one hand,

parametric tests (t-tests) are used to explain differences between the means of the variables

non-18 parametric tests (chi-square8) allow us to prove the existence or not of a dependency

relationship between two variables.

Knowledge and Attitudes towards the Brand and the Product

Results show that the great majority of the participants (91.2%) are familiar with the brand,

which confirms our expectations from the pre-test. Children’s attitudes towards the brand,

the logo and the products are mostly positive but distributed between the positive values of

the scale, being the highest value obtained for taste. To analyze the results related with the knowledge about the brand and its’ products, t-tests were performed to compare the means

between Control and Experimental groups. Results indicate that the means calculated were relatively high in both groups but the differences are not significant (p>0.1).

Table 1:Knowledge and Attitudes towards the Brand and the Product: T-Tests by group

8

Due to the small size of the sample, we used the Likelihood Ratio to test the significance of each relation between variables. This ratio measures the strength of association when the sample is too small and there is a need to guarantee a reliable analysis.

T-Tests

Item Group N Mean Std. Deviation P-Value

Brand Recognition Control 73 4,781 0,7312 0,414

Experimental 63 4,873 0,5533

Brand Attitude (Hate-Love) Control 73 3,863 1,0842 0,500

Experimental 63 3,984 0,9918

Attitudes towards Logo (Not Cool-Cool) Control 73 3,575 1,2351 0,660

Experimental 63 3,667 1,1640

Attitudes towards Products Control 73 4,055 1,1413 0,823

Experimental 63 4,095 0,9283

Taste Control 73 4,356 1,0849 0,899

Experimental 63 4,333 0,9837 Knowledge and Attitudes Average

Control 73 4,126 0,6852

0,540

19 However, the chi-square tests provided some significant results (Table 2). First of all, by

comparing the brand recognition and the group of analysis, we can say that children who

see the brand on the shirt tend to be more familiar with it (p=0.07). Secondly, and

unexpectedly, regarding the attitude towards the product, children who did not see the shirt

with the logo seem to be more engaged with the products of that brand (p=0.10). In fact, children’s answers in the Experimental group are also positive but much more distributed

than those in the Control Group.

Table 2:Brand Recognition and Attitudes towards Products by group: Chi-Square Analysis

Brand Recognition Attitudes towards Products

Group Group

Control Experimental Control Experimental

Scale 1 Frequency 1 1 3 1 % of Group 1,4% 1,6% 4,1% 1,6% 2 Frequency 1 0 2 0 % of Group 1,4% 0,0% 2,7% 0,0% 3 Frequency 4 0 21 18 % of Group 5,5% 0,0% 28,8% 28,6% 4 Frequency 1 4 9 17 % of Group 1,4% 6,3% 12,3% 27,0% 5 Frequency 66 58 38 27 % of Group 90,4% 92,1% 52,1% 42,9% P-Value 0,071 0,104

Overall, the results suggest that sponsorship affects positively the knowledge about the

brand and negatively the attitudes towards the product. However, it does not have an impact

in attitudes towards the shirt and logo as well as in the opinion about the taste of the

products. As so, there is no statistical evidence to confirm that sponsorship of healthy food

20

Behaviour

As previously referred, participants had to choose six products from a total of twelve (six

healthy and six unhealthy). The idea was then to compare the answers between the two

different groups (Experimental and Control) and confirm that children who saw the shirt

with the logo would pick more healthy products than those who did not see it. And that

would tell us if they would be more willing to change their eating behaviour or not., Results

show that from those who saw the shirt (experimental group), only 57.1% chose three or

more healthy products, while 67.1% of the participants who did not see the shirt (control

group) chose three or more healthy products. This apparent difference was not significant

(p=0.136) and therefore, there is not sufficient evidence to support RQ3.

Attitudes towards Healthy Eating

The last research question was designed to try to understand if children recognize the

importance of healthy eating and are willing to improve their eating habits. Results show

that 92.6% agree that eating healthily is very important and 94.9% think that eating

healthily will help them grow. In addition, 79.4% plans to eat more healthily and 80.9%

intend to eat more healthily, in the near future. Yet, only 34.6% of the participants see fast

food as bad for them. To test attitudes towards healthy eating and compare the results

obtained from Control and Experimental Groups, we performed t-tests and chi-square tests

on the overall variable and on each item, but none of the differences was statistically

significant (p>0.1). Overall, we can conclude that although sponsorship seems to have an

impact on attitudes towards healthy eating, there is no statistical evidence to ensure that

children who receive the shirt stimulus will be more aware about the importance of having

21

Table 3: Tests on Attitudes towards Healthy Eating by group

Understanding the Persuasive Intent

Regarding the analysis of understanding the persuasive intent of the brand, only the

Experimental group was considered. Results show that the great majority of the participants weren’t able to identify the source of the placement on the shirt or to recognize the

persuasive intent of the brand. Indeed, only 20.6% identified the source of the placement as

being Mimosa, and only 31.7% understood the persuasive intent to buy the brand. To test for a potential association between sponsor’s influence and recognition of the persuasive

intent, a chi-square analysis was performed. We crossed the variables related with the

identification of the source of placement and recognition of the persuasive intent with the

variable associated to changes in behaviour (measured by the total number of healthy

products picked by the participants). Results show that very few participants were able to

identify the source and understand the persuasive intent while picking more than three

healthy products. However, there is statistical evidence that understanding the persuasive

Item Group Mean

T-test (P-Value)

Qui-square test (P-Value)

Healthy eating is important

Control 4,521

0,398 0,637

Experimental 4,619

Fast food is not bad Control 2,986 0,403 0,193

Experimental 3,159 Healthy eating helps growth

Control 4,575

0,655 0,740

Experimental 4,635

Planning to eat healthily Control 4,123 0,982 0,918

Experimental 4,127 Intention to eat healthily

Control 4,055

0,689 0,867

Experimental 4,127

Attitudes towards healthy eating Average Control 4,052 0,431

22 intent is related with picking healthy products (p=0.09). Therefore, we only accept RQ2

partially, in the sense that only children who understand the intent of the brand are induced

to change their eating habits, which means, the understanding of the persuasive intent

generated a response to cope with that intent and thus choose more healthy items.

Table 4:Understanding Persuasive Intent by Total Healthy products picked: Chi-Square Analysis

Identify source of placement of the logo Understand persuasive intent Total Healthy products

picked (%) Wrong Right Wrong Right

Less than three 40% 53,9% 53,5% 20%

Three or more 60% 46,1% 46,5% 80%

P-Value 0,375 0,090

We also continued this analysis to see to what extent the persuasion knowledge of the child

significantly affected other attitudes. Firstly, we crossed the same variables with those

related with attitudes towards healthy eating. The results showing the association (p-values)

between variables are presented in table 5. Secondly, we proceeded to the crosstab between

the same variables and those related with knowledge and attitudes towards the brand and

the product (table 6).

Table 5:Understanding Persuasive Intent and Attitudes towards Healthy Eating: Chi-Square Analysis Healthy eating is

important

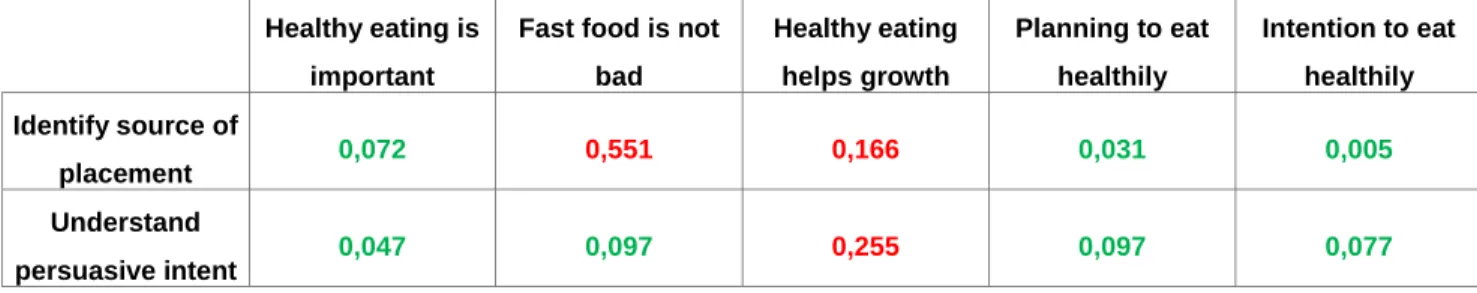

Fast food is not bad Healthy eating helps growth Planning to eat healthily Intention to eat healthily Identify source of placement 0,072 0,551 0,166 0,031 0,005 Understand persuasive intent 0,047 0,097 0,255 0,097 0,077

23

Table 6: Understanding Persuasive Intent and Knowledge and Attitudes towards the Brand/Product: Chi-Square Analysis Brand Recognition Brand attitude (Hate-Love) Attitude towards the logo

(Cool-Not Cool)

Attitudes

towards products Taste Identify source of

placement 0,072 0,860 0,095 0,582 0,052

Understand

persuasive intent 0,644 0,219 0,017 0,571 0,626

Discussion and Implications

The aim of this study was to analyze if children were affected by sponsorship and able to

understand the intent of sponsors. Furthermore, this study also aimed to test if sports

sponsorship were a good way to influence children consumer behaviour towards healthy

food brands and to promote a better diet among them. The results indicate that this specific case of sponsoring children’s Rugby teams is not an effective strategy to influence their

attitudes towards healthy eating. In fact, there are almost no differences between

participants who received the stimulus and those who did not. However, there are obviously

other possible alternatives that could turn over children sports sponsorship into an effective

communication tool. Therefore, it is crucial for companies focused on promoting healthy

food brands to find a way to take advantage of this marketing strategy and drive children

attention towards the importance of making healthy food choices on every stages of their

childhood.

Knowledge and Attitudes towards the Brand and the Product

Since the great majority of children are already familiar with the brand, seeing it or not in

the shirt does not seem to alter their perceptions regarding knowledge and attitudes towards the brand and its’ products. Furthermore, we could not find any clear association between

24 the groups of observation and the items related with the liking for the brand, its’ logo and

taste. However, there is an association between knowledge and the group observed,

showing that sponsoring could be a good driver for children to get familiar with new

healthy food brands. Besides that, the group is also associated with the participants’ opinion

regarding the products of the brand. But surprisingly, these results suggest that children

who see only the brand logo like the products more. And this leads us to believe that maybe

children like the products but not when they see them associated with their favorite sport.

Hence, brands who want to create a relationship with sports should be cautious when

building their strategy and analyzing its effectiveness. Besides, kids could also give much

importance to what is familiar to them. In fact, they could be used to play with the current

shirt and do not go along with a new shirt, which seems unfamiliar or different.

Behaviour

As previously referred, there is no association between the products selection and the group

observed. Results show that children who did not see the shirt tend to choose more healthy

products. This could mean that the logo, only by itself, drives their attention to the need of

choosing healthy food in the questionnaire. Maybe they think the questionnaires were

assessing their eating choices and want to look as healthier as possible to the evaluator. On

the opposite, children who see the brand logo on the shirt could be less focused on it and do

not realize the evaluator is assessing their healthy behaviour. As so, their recall rate towards

the logo during the questionnaire might be lower. It is also interesting to see what healthy

and unhealthy products were chosen the most. On one side, the top three unhealthy

25 fries (52.2%). Indeed, children express their preferences for fatty and sugary foods, which

are consistent with previous findings (Cooke and Wardle, 2005). On the other side, the

most chosen healthy products were banana (69.1%), milk (57.4%) and mixed fruits

(57.4%). It is particularly importance to enhance the inclusion of fruit items as it already

happened before (Cooke and Wardle, 2005). The choice of milk over yogurt is also

unexpected since usually children tend to support better yogurts, which are less

concentrated and more tasteful.

Attitudes towards Healthy Eating

Regarding the analysis of children’s attitudes towards healthy eating, despite children who

see the shirt give higher scores to the scale items, there is no statistical evidence to

conclude that seeing the shirt will encourage them to give more importance to eating

healthily. In general, results show that regardless of being subject to the treatment effect,

children already demonstrate to have good attitudes towards healthy eating. The exception

is their opinion about fast food. In fact, although fast-food is not a daily habit and people

take it for reasons such as convenience and busy lifestyle (Paeratakul et al., 2003), it is very

popular among kids and it is believed that contributes to a poor diet. An interesting

assumption to think of is that maybe children see this example as a real sponsoring

possibility for their team and give lower marks because they are hopeful about that chance.

As so, the main suggestions that should be given are related with promoting actions that

could combat or hold back fast food sponsorships to children sports teams. As sports

sponsoring is increasing as an important source of funding for sports teams and as a

26 should be watchful for the threats that may arise from sponsorship agreements with fast

food brands.

Understanding the Persuasive Intent

By analyzing the results related with the understanding of the persuasive intent of the

brand, we rejected the hypothesis that assumed that children were able to identify the main

responsible for a sponsorship agreement in sports. A possible explanation for this inability

could be the fact that children think that there are many parts involved in the process

(which in some way is true) and are not entirely sure about the one that plays the bigger

role. Besides that, most of the participants had chosen their team as the responsible for the

placement of the logo on the shirt, which shows that many children are not nearly aware of

the correct source of sponsorship. Regarding the recognition of the persuasive intent of the

brand, few participants were able to understand that the brand wants them to buy its

products. However, from all the alternatives available, this was the one that has been picked

the most (31.7%). Even so, the difference is not significant at all, with the rest of the

participants choosing the options “Play Rugby better” (30.2%) or “By the new shirt” (27%)

as the right intention. These results can be explained by the fact that sponsorship is still

seen by children as a confusing marketing tool and it can be more complicated for them to understand its’ persuasive intent than it is with television advertising (Oates et al., 2002).

Moreover, it is generally easier for children to understand the informational intent of

advertising rather than the persuasion or selling intent, which is more complex and requires

an upper level of comprehension (Martin, 1997). By looking to the chi-square test between

27 products chosen, we can see that, from those participants who understood the persuasive

intent of the brand, the great majority of them picked more than three healthy products.

These results lead us to believe that when children have more persuasion knowledge, they

tend to cope with the intended behavior, and to choose wisely. However, we also found that

the majority of children that identified the source of placement and understood the

persuasive intent tended to be less influenced regarding attitudes towards planning and

intending to eat healthily. This is very interesting since they understand the role of the

brand but do not let themselves be influenced by it in a conscious way (by agreeing with

the attitude statements) but cope with it in an unconscious way (by choosing more healthy

items). Finally, we discovered that children who guess the source of the placement and

understand the persuasion intent find the logo of the brand cooler. In addition, there was a

significant percentage of participants who identified the source of placement and rated the

products taste with higher marks. These results indicate that generally children are still a

little bit confused about the sponsoring process and do not understand it completely,

making it hard for them to filter what is good or not for their health, and also making

different decisions whether to cope or not with the desired behavior (Friestad and Wright,

1994).

Limitations and Future Research

This research presents several limitations that should be taken into account as an example

to improve in future research. Firstly, it is only applied to one type of sport, which is

Rugby, and to boys. It would be interesting to perform it to other team sports like Soccer or

28 the same background and education and their opinions tend to be similar, but mixing

different sports and gender could lead to a greater diversity and thus enhance some results

that were not evident here. Beyond that, only Rugby teams belonging to the district of

Lisbon were considered. There could be differences in terms of social background and

habits between children from Lisbon and from other points of the country, like the North or

South. Furthermore, it is also interesting to take this research abroad of Portugal and

perform it in other countries with different cultures. Another limitation is related with the

familiarity of the brand to the great majority of the participants. Therefore, we suggest to

take the same study but with unfamiliar brands. Finally, this study was based on a fictitious case of a brand logo placement on Rugby teams’ shirts. Further research could look upon

studying the impact of a real case of sponsorship during a significant period of time, so that

children could really experience it. It might be more difficult to perform but it would

certainly allow taking more reliable conclusions.

References

Achenreiner, G. B., & John, D. R. (2003). The meaning of brand names to children: A developmental

investigation. Journal of Consumer Psychology,13(3), 205-219.

Alvensleben, R. V., Padberg, D. I., Ritson, C., & Albisu, L. M. (1997). Consumer behaviour. Agro-food

marketing., 209-224.

Amis, J., Slack, T., & Berrett, T. (1999). Sport sponsorship as distinctive competence. European journal of

marketing, 33(3/4), 250-272.

Blatt, J., Spencer, L., & Ward, S. (1972). A cognitive development study of children’s reactions to

television advertising. Television and social behavior, 4, 452-67.

Blosser, B. J., & Roberts, D. F. (1985). Age differences in children's perceptions of message intent:

Responses to TV News, Commercials, Educational Spots, and Public Service Announcements. Communication Research, 12(4), 455-484.

Buchan, Nick (2006). Sports Sponsorship – Still Giving Enough bang for the Buck?. B&T Weekly, 56 (2567),

5.

Carter, O. B., Patterson, L. J., Donovan, R. J., Ewing, M. T., & Roberts, C. M. (2011). Children’s

understanding of the selling versus persuasive intent of junk food advertising: Implications for regulation. Social Science & Medicine, 72(6), 962-968.

29

Cooke, L. J., & Wardle, J. (2005). Age and gender differences in children's food preferences. British

Journal of Nutrition, 93(05), 741-746.

Cornwell, T. B., & Maignan, I. (1998). An international review of sponsorship research. Journal of

Advertising, 27(1), 1-21.

Dixon, H. G., Scully, M. L., Wakefield, M. A., White, V. M., & Crawford, D. A. (2007). The effects of

television advertisements for junk food versus nutritious food on children's food attitudes and preferences. Social science & medicine,65(7), 1311-1323.

Donohue, T. R., Henke, L. L., & Donohue, W. A. (1980). Do kids know what TV commercials

intend. Journal of Advertising Research, 20(5), 51-57.

Friestad, M., Wright, P. (1994). The Persuasion Knowledge Model: how People Cope with Persuasion

Attempts. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(1), 1-31

Gabbett, T. J. (2002). Physiological characteristics of junior and senior rugby league players. British Journal

of Sports Medicine, 36(5), 334-339.

Goldberg, M. E., Gorn, G. J., & Gibson, W. (1978). TV messages for snack and breakfast foods: do they

influence children's preferences?. Journal of Consumer Research, 73-81.

Gwinner, K. P., & Eaton, J. (1999). Building brand image through event sponsorship: the role of image

transfer. Journal of advertising, 28(4), 47-57

Gwinner, K., & Swanson, S. R. (2003). A model of fan identification: antecedents and sponsorship

outcomes. Journal of services marketing, 17(3), 275-294.

Hastings, G., McDermott, L., Angus, K., Stead, M., & Thomson, S. (2006). The extent, nature and effects

of food promotion to children: a review of the evidence. Geneva: World Health Organisation.

International Events Group (IEG). (2014). Sponsorship Spending Growth Slows In North America As

Marketers Eye Newer Media And Marketing Options.

http://www.sponsorship.com/IEGSR/2014/01/07/Sponsorship-Spending-Growth-Slows-In-North-America.aspx (accessed September 24, 2014)

Jensen, J. A., & Hsu, A. (2011). Does sponsorship pay off? An examination of the relationship between

investment in sponsorship and business performance. International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, 12(4).

John, D. R. (1999). Consumer socialization of children: A retrospective look at twenty-five years of

research. Journal of consumer research, 26(3), 183-213.

Kahle, L. R., & Riley, C. (Eds.). (2004). Sports marketing and the psychology of marketing communication.

Psychology Press.

Kelly, B., Chapman, K., Baur, L., Bauman, A., King, L., & Smith, B. (2013). Building Solutions to

Protect Children from Unhealthy Food and Drink Sport Sponsorship.

Macklin, M. C. (1987). Preschoolers' understanding of the informational function of television

advertising. Journal of Consumer research, 229-239.

Maher, A., Wilson, N., Signal, L., & Thomson, G. (2006). Patterns of sports sponsorship by gambling,

alcohol and food companies: an Internet survey. BMC Public Health, 6(1), 95.

Martin, M. C. (1997). Children's understanding of the intent of advertising: a meta-analysis. Journal of

Public Policy & Marketing, 205-216.

Mason, K. (2005). How corporate sport sponsorship impacts consumer behavior. Journal of American

Academy of Business, 7(1), 32-35.

Oates, C., Blades, M., & Gunter, B. (2002). Children and television advertising: When do they understand

persuasive intent?. Journal of Consumer Behaviour,1(3), 238-245.

Oates, C., Blades, M., Gunter, B., & Don, J. (2003). Children's understanding of television advertising: a

qualitative approach. Journal of Marketing Communications, 9(2), 59-71.

Omnibus Research Report. (2007). Children’s attitudes towards food - Prepared for the Food Standards

30

Paeratakul, S., Ferdinand, D. P., Champagne, C. M., Ryan, D. H., & Bray, G. A. (2003). Fast-food

consumption among US adults and children: dietary and nutrient intake profile. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 103(10), 1332-1338.

Patrick, H., & Nicklas, T. A. (2005). A review of family and social determinants of children’s eating

patterns and diet quality. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 24(2), 83-92.

Pettigrew, S., Rosenberg, M., Ferguson, R., Houghton, S., & Wood, L. (2013). Game on: do children

absorb sports sponsorship messages?. Public health nutrition, 16(12), 2197-2204.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in

behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of applied psychology, 88(5), 879.

Robinson, C. H., & Thomas, S. P. (2004). The interaction model of client health behavior as a conceptual

guide in the explanation of children's health behaviors. Public Health Nursing, 21(1), 73-84.

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Parker, J. G. (1998). Peer interactions, relationships, and

groups. Handbook of child psychology.

Salvy, S. J., De La Haye, K., Bowker, J. C., & Hermans, R. C. (2012). Influence of peers and friends on

children's and adolescents' eating and activity behaviors. Physiology & behavior, 106(3), 369-378.

Sangperm, P., Tilokskulchai, F., Phuphaibul, R., Vorapongsathon, T., & Stein, K. (2008). Predicting

adolescent healthy eating behavior using subjective norms, intention and self-schema. Mahidol University.

Selman, R. L. (1980). The growth of interpersonal understanding (p. 24). New York: Academic Press. Shank, M. D. (1999). Sports marketing: A strategic perspective. Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Simoes, I., & Agante, L. (2014). The impact of event sponsorship on Portuguese children's brand image and

purchase intentions: The moderator effects of product involvement and brand familiarity. International Journal of Advertising, 33(3), 533-556.

Stead, M., McDermott, L., Forsyth, A., MacKintosh, A. M., Rayner, M., Godfrey, Caraher, M. & Angus, K. (2003). Review of research on the effects of food promotion to children (pp. 1-218). Glasgow:

Centre for Social Marketing, University of Strathclyde.

Story, M., Kaphingst, K. M., Robinson-O'Brien, R., & Glanz, K. (2008). Creating healthy food and eating

environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu. Rev. Public Health, 29, 253-272.

Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge

University Press.

Tsiotsou, R., & Alexandris, K. (2009). Delineating the outcomes of sponsorship: sponsor image, word of

mouth, and purchase intentions. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 37(4), 358-369.

UNICEF. (2002). Children Participating in Research, Monitoring, and Evaluation (M&E)–Ethics and Your

Responsibilities as a Manager. Evaluation Technical Notes, (1), 1-11.

Wakefield, K. L., & Bennett, G. (2010). Affective intensity and sponsor identification. Journal of

Advertising, 39(3), 99-111.

Walraven, M., Bijmolt, T. H., & Koning, R. H. (2014). Dynamic Effects of Sponsoring: How Sponsorship