LORENZO INNOCENTI

Correlation between obesity and balance

Master in Sports Sciences – Evaluation and Exercise Prescritpion

Supervisors: Gian Pietro Emerenziani Nuno Domingos Garrido

UNIVERSIDADE DE TRÁS-OS-MONTES E ALTO DOURO VILA REAL, 2018

LORENZO INNOCENTI

Correlation between obesity and balance

Master in Sports Sciences – Evaluation and Exercise Prescritpion

Supervisors: Gian Pietro Emerenziani Nuno Domingos Garrido

UTAD Vila Real – 2018

GENERAL INDEX

LIST OF FIGURES ... IV LIST OF TABLES ... V ACKNOLEDGMENTS ... VI ABSTRACT ... VIII RESUMO ... IX INTRODUCTION ... 1CHAPTER 1 – THE OBESITY ... 3

1.1 The obesity: Definition and Incidence ... 3

1.2 Classification of levels in obesity population ... 7

1.3 Health benefits and risks of weight loss ... 9

1.3.1 Problems in evaluating the effects of long-term weight loss ... 10

1.3.2 Weight loss and general health ... 11

1.3.3 Impact of weight loss on chronic disease, and on endocrine and metabolic disturbances ... 13

1.3.4 Weight loss and psychosocial functioning ... 16

1.3.5 Hazards of weight loss ... 17

1.3.6 Weight cycling ... 18

1.3.7 Effects of weight loss in obese children and adolescents ... 19

1.4 Prevention ... 20

1.4.1 Priority interventions ... 23

1.4.2 physical activity patterns ... 23

1.4.3 Impact of physical activity on food ... 27

CHAPTER 2 - THE BALANCE ... 29

2.1 Nervous system and Vestibular system ... 29

2.1.1 Vestibular nervous system and structure ... 29

2.1.2 Neuromuscolar spindles and Golgi tendon organs ... 30

2.2 Control of muscle tone and posture ... 33

2.2.1 Static proprioceptive responses ... 33

2.2.2 Dynamic proprioceptive responses ... 34

2.3 Extra-labyrinthine receptors for gravity perception ... 34

2.3.1 Complex postural reflex ... 34

2.3.2 Visual receptors ... 35

2.4 Global antigravity postural regulation ... 36

2.4.1 Adjustment of the center of gravity ... 36

2.4.2 Central construction of the body scheme ... 37

2.5 Incidence of balance in physical activity in obese population ... 37

2.6 Incidence of balance in physical activity in elderly population ... 41

CHAPTER 3 – METHODS ... 53

3.1 Participants... 53

3.2.1 Anthropometric measurements ... 54

3.2.2 Body impedence assessment by weight-scale ... 55

3.3 Experimental Protocols ... 56

3.3.1 Six-minute walking test ... 56

3.3.2 OMNI Perceived Exertion scale (RPE) ... 58

3.3.3 One-leg standing balance (OLSB) ... 60

3.4 Statistical analysis ... 61

CHAPTER 4 – RESULTS ... 63

CHAPTER 5 – DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION ... 65

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 2.1……….32 Figure 2.2……….51 Figure 2.3……….52 Figure 3.1……….54 Figure 3.2……….56 Figure 3.3……….59 Figure 3.4……….60 Figure 4.1……….64 Figure 4.2……….65

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1.1………...8 Table 1.2………...25 Table 4.1………...64

ACKNOLEDGMENTS

I gratefully acknowledge all who directly or indirectly contributed to the realization and conclusion of this study.

The “Università di Scienze Motorie del Foro Italico - Roma, Italia”, namely its Magnificent Rector, Professor Fabio Pigozzi, for given me the opportunity to set the experimental trials of this research.

Dott. Gianpietro Emerenziani, PhD of “Università di Scienze Motorie del Foro Italico - Department of Health Science – Rome, Italy”, the supervisor of my thesis, for the support throughout the planning and organization of this research, especially for promoting in a responsible way my autonomy of investigation.

Professor Nuno Garrido, PhD of “Sports Sciences, Exercise & Health Department of University of Trás-os-Montes & Alto Douro, Vila Real, Portugal”, the co-supervisor of my thesis, for the support throughout this research, especially for making it easier to live and study at UTAD.

Professor Carlo Baldari, PhD of “Università di Scienze Motorie del Foro Italico - Department of Health Science – Rome, Italy”, for conceding the opportunity to achieve this work and the adventure of University life in Portugal.

The “Universidade de Tras-os-Montes et Alto Douro (UTAD) - Vila Real, Portugal”, namely Victor Reis, Professor and Vice Coordinator of the Doctorat Cours in Sport Sciences at UTAD.

My mother Antonella, my father Alessandro, my brother Tommaso and my aunt Chiara for their love, and their support every time in this study.

My Uncle Gianfranco Lamberti for the great commitment and passion of his profession that he transmitted to me in the last days of writing the thesis.

The sport and the music that have always accompanied me in my life.

What do music and sport have in common? Everything. A great melody, a great race ... they can be reached with training and passion.

ABSTRACT

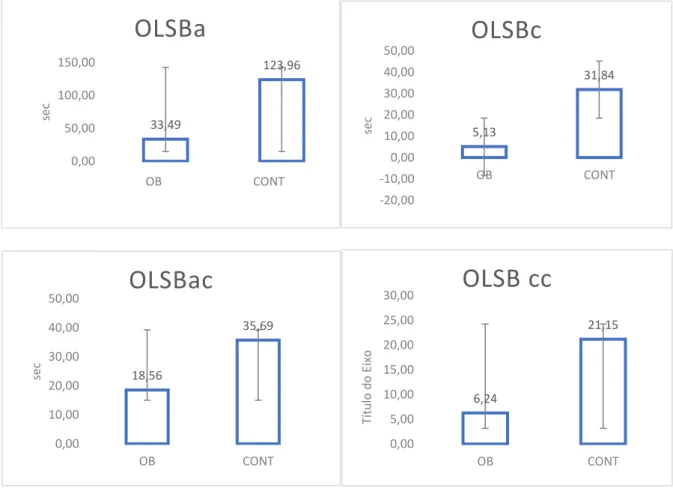

The aim of this study was to understand if there are correlations between static balance and body mass composition, in the female gender. Forty-four participants, which were 23 obese (group OB) and 21 normal-weights (group CONT). The mean ± SD age, height and body mass of subject were between the normal-weight group and the obese group, respectively: 37.5 ± 15.9 and 45.2 ± 13.2 years, 21.2 ± 1.6 and 38.1 ± 4.4 BMI, 24.5 ± 5.2 and 46.7 ± 5.0 %Fat-max. An Independent sample tests immediately yielded interesting results with high significance (p<0.001), and a high statistical power observed (> 0.8), between these two groups. An Independent t-test showed significant differences between group OB and group CONT in BMI (p<0.002), in weight (p<0.001), but not in FFM (p>0.005) and in HRrip (p>0.005). Multivariate tests were used to identify comparisons between the two groups in the different protocols carried out: Six Minutes Walking Test (SMWT) and One-leg static balance (OLSB). In the multivariate test of the OLSB, very significant differences were found between the group CONT and the group OB: in OLSBa ( eyes open) ( p<0.001), in OLSB ac ( eyes open with mathematical task) (p<0.002), in OLSBc ( eyes closed) (p<0.001), in OLSBcc (eyes closed with mathematical task) (p<0.001) and in OLSBccstep ( the steps reached at the end of the test with a mathematical task) (p<0.05). Also, in the multivariate test of the SMWT, very significant differences were found between the two groups: in SMWTdist (distance traveled) (p<0.001), in SMWTvel (velocity traveled) (p<0.001) and in SMWT-RPE (Perceived Exertion scale) (p<0.001). Bio-impedenziometria measurements were analyzed the body mass and composition. This preliminary study shows that physical activity and static balance capacity have significative differences between a normal-weight and an obese population. This study suggests investigating in general populations such as elderly and adolescents/children in both sexes.

RESUMO

O objetivo deste estudo foi compreender se existem correlações entre o equilíbrio estático e a composição da massa corporal, no gênero feminino. Quarenta e quatro participantes, que eram 23 obesos (grupo OB) e 21 pesos normais (grupo CONT). A média ± DP idade, estatura e massa corporal dos sujeitos foram entre o grupo com peso normal e o grupo obeso, respectivamente: 37,5 ± 15,9 e 45,2 ± 13,2 anos, 21,2 ± 1,6 e 38,1 ± 4,4 IMC, 24,5 ± 5,2 e 46,7 ± 5,0% de gordura-max. Um teste de amostra independente imediatamente produziu resultados interessantes com alta significância (p <0,001), e um alto poder estatístico observado (> 0,8), entre esses dois grupos. Um teste t independente mostrou diferenças significativas entre o grupo OB e o grupo CONT no IMC (p <0,002), no peso (p <0,001), mas não no MLG (p> 0,005) e no HRrip (p> 0,005). Testes multivariados foram utilizados para identificar comparações entre os dois grupos nos diferentes protocolos realizados: Teste de Caminhada em Seis Minutos (SMWT) e Equilíbrio estático em uma perna (OLSB). No teste multivariado do OLSB, foram encontradas diferenças muito significativas entre o grupo CONT e o grupo OB: em OLSBa (olhos abertos) (p <0,001), em OLSB ac (olhos abertos com tarefa matemática) (p <0,002), em OLSBc (olhos fechados) (p <0,001), em OLSBcc (olhos fechados com tarefa matemática) (p <0,001) e em OLSBccstep (os passos alcançados no final do teste com uma tarefa matemática) (p <0,05). Também no teste multivariado do SMWT, diferenças muito significativas foram encontradas entre os dois grupos: em SMWTdist (distância percorrida) (p <0,001), em SMWTvel (velocidade percorrida) (p <0,001) e em SMWT-RPE (Esforço Percebido escala) (p <0,001). Medidas de bio-impedenziometria foram analisadas quanto à massa corporal e composição. Este estudo preliminar mostra que a atividade física e a capacidade de equilíbrio estático apresentam diferenças significativas entre uma população com peso normal e uma população obesa. Este estudo sugere investigar populações em geral, como idosos e adolescentes / crianças, em ambos os sexos.

INTRODUCTION

The aim of this study was therefore to understand if there are indeed correlations between static balance and body mass composition, object of study analyzed in the female gender in this case.

In recent years many physiological aspects and behaviors have been discussed in the area of obesity, especially in the medical field.

In the scientific literature, aspects of the obese population have not been thoroughly investigated with respect to body composition.

Another important consideration should be made: the choice of this study was determined by the activity carried out in the laboratory of the supervisor of this thesis study. In particular the scientific activities of dr. Gian Pietro Emerenziani concern studies on the obese population. So the data collected by the obese group had been easily operated thanks to another study called “programma casco” with already more than 450 participants, even by the author of this thesis collected and analyzed many months before the beginning of development of this study; with regard to the normal-weight group other participants were intercepted or internal to the university (teachers, students, employees). The inclusion criteria observed were: physical activity for less than 150 minutes at high / moderate intensity (according to WHO guidelines, 2014), a BMI ratio, which was in the "normal" range as from 18,5 to 24,9.

Given that in the obese group there were many subjects of different ages, due to the data collection of another study conducted in the same laboratory unit, and of a difficult nature to recruit in this particular special population. Therefore also in the Noraml-weight group were recruited subjects who had the same average age (minimum and maximum) as a whole compared to the other survey group.

Then, in terms of presentation, the fundamental concepts about obesity, definition and Incidence, classification of levels, health benefits and risks of weight loss and prevention was considered in Chapter 1. in Chapter 2 was considered the balance: the nervous system and the vestibolar system, the control of muscle tone and posture, the extra-labyrinthine receptors for gravity perception, the global antigravity postural regulation, incidence of balance in physical activity. In Chapter 3 methods, experimental session and statistical analysis of the study, were described. In Chapter 4, 5 and 6 the results, discussion and conclusion will be presented.

CHAPTER 1 – THE OBESITY

1.1 The obesity: Definition and Incidence

The terms overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal/ excessive fat accumulation with Body Mass Index (BMI) 25 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2, respectively. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 1.9 billion adults are overweight worldwide; with 600 million obese adults in 20141. In the U.S., the situation is exacerbated with 78.6 million adults being classified as obese in 2012.2

Gait patterns can also be altered by obesity, and the relevant changes in gait patterns may increase the risks of developing osteoarthritis and falling3-4. Additionally, fall risk is still an issue for patients after interventions such as gastric bypass5.

In 2015, about 110million children and young adults (under 20 years of age) were estimated to be obese, equivalent to an overall prevalence of 5%.6 Epidemiological data show that the number of overweight or obese infants and young children (aged 0–5 years) increased from 32million globally in 1990 to 42million in 2013. If these trends will continue, the number of

1World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight; 2018, Available from:

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/.

2Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States.

2011–2012. J Am Med Assoc 2014;311(February (8)):806–14. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ 24570244 [cited 9.07.14].

3S.C. Wearing, E.M. Hennig, N.M. Byrne, J.R. Steele, A.P. Hills. The biomechanics of restricted movement in

adult obesity. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 7 (2006) 13–24.

4S.V. Gill, A. Narain. Quantifying the effects of body mass index on safety: reliability of a video coding

procedure and utility of a rhythmic walking task. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 93 (2012) 728–730.

5A. Berarducci, K. Haines, M.M. Murr. Incidence of bone loss falls, and fractures after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass

for morbid obesity. Appl. Nurs. Res. 22 (2009) 35–41.

6Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 Countries over

overweight or obese infants and young children is expected to spiral up to 70 million by 2025.1

Although the prevalence of childhood obesity is estimated to be lower than the prevalence of adult obesity (5% against 13%), the rate of increase in childhood obesity in many countries is alarmingly greater than the rate of increase in adult obesity.2

After only 2 years, in 2016, over 650 million adults were obese, and 39% of adults aged 18 years and over (39% of men and 40% of women) were overweight.

Overall, about 13% of the world’s adult population (11% of men and 15% of women) were obese in 2016.

The worldwide prevalence of obesity nearly tripled between 1975 and 2016.

In 2016, an estimated 41 million children under the age of 5 years were overweight or obese. Once considered a high-income country problem, overweight and obesity are now on the rise in low and middle-income countries, particularly in urban settings. In Africa, the number of overweight children under 5 has increased by nearly 50 per cent since 2000. Nearly half of the children under 5 who were overweight or obese in 2016 lived in Asia.

Over 340 million children and adolescents aged 5-19 were overweight or obese in 2016. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents aged 5-19 has risen dramatically from just 4% in 1975 to just over 18% in 2016. The rise has occurred similarly among both boys and girls: in 2016 18% of girls and 19% of boys were overweight.

While just under 1% of children and adolescents aged 5-19 were obese in 1975, more 124 million children and adolescents (6% of girls and 8% of boys) were obese in 2016.

Overweight and obesity are linked to more deaths worldwide than underweight. Globally there are more people who are obese than underweight this occurs in every region except parts of sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.7

Recently, obesity has been linked with memory deficits and cognitive dysfunction in middle-aged and older adults8-9. Increased adiposity, resulting in obesity, may require additional attention for controlling posture10. Cognitive motor interference, defined as decrements in performance that occur when cognitive and motor tasks are performed simultaneously (dual- task conditions), has been linked with falls8.

A study compared the kinematics in adults at two different speeds; obese individuals walked with a more extended knee during early stance and greater pelvic obliquity11. Similar extended knee motion was also observed in obese adolescents12. However, no significant differences were found between the obese group and no obese group in sagittal plane motion in yet another study13.

It is evident that knee motion is critical in maintaining gait stability.

7WHO, link web-page: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/, 2018, rewiewed February.

8Dahl a K, Hassing LB, Fransson EI, Gatz M, Reynolds CA, Pedersen NL. Body mass index across midlife and

cognitive change in late life. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37(February (2)):296–302. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/pubmed/22450854 [cited 11.03.13].

9TeasdaleN, SimoneauM. Attentional demands for postural control: theeffects of aging and sensory reintegration.

Gait Posture 2001;14(December (3)):203– 10. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11600323.

10Mignardot J-B, Olivier I, Promayon E, Nougier V. Obesity impact on the attentional cost for controlling

posture. PLoS ONE 2010;5(January (12)):e14387. Available from:

http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3004786&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract [cit- ed 11.12.12].

11Z.F. Lerner, W.J. Board, R.C. Browning. Effects of obesity on lower extremity muscle function during walking

at two speeds. Gait Posture 39 (2014) 978–984.

12A.G. McMillan, M.E. Pulver, D.N. Collier, D.S.B. Williams. Sagittal and frontal plane joint mechanics

throughout the stance phase of walking in adolescents who are obese. Gait Posture 32 (2010) 263–268.

13P.P.K. Lai, A.K.L. Leung, A.N.M. Li, M. Zhang. Three-dimensional gait analysis of obese adults. Clin.

One major similarity among previous studies on obesity and gait is in using BMI to define obesity. Authors 14 found that body fat percentage has a more clearly correlation with deterioration of postural control as compared to BMI. Although a previous study looked into the effects of obesity classification method on kinematic gait variables, it only focused on the different effects of BMI and fat percentage, and it did not formulate a conclusion on which method is better in assessing gait.15

This study has as primary end-point the observation of differences in gait features among overweight and obese adults compared to normal weight adults. Secondary end-point is the observation of differences of gait respect to body fat percentage (%Fat).

Obesity is associated with serious medical complications that impair quality of life16-17. It also modifies body geometry, increases the fat mass of the different segments18-19. Therefore, Functional limitations pertaining to the biomechanics of activities of daily living, that may predispose the obese to injury.20

14H. Meng, D.P. O’Connor, B.-C. Lee, C.S. Layne, S.L. Gorniak, Effects of adiposity on postural control and

cognition. Gait Posture 43 (2016) 31–37.

15A. Page Glave, R. Brezzo Di, D.K. Applegate, J.M. Olson, The effects of obesity classification method on select

kinematic gait variables in adult female. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fitness 54 (2014) 192–202.

16Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R. Body mass index, waist circumference, and health risk: evidence in support

of current National Institutes of Health guidelines. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:2074–9.

17Bray GA. Medical consequences of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:2583–9.

18Fabris de Souza SA, Faintuch J, Valezi AC, et al. Postural changes in morbidly obese patients. Obest Surg

2005;15:1013–6.

19Rodacki AL, Fowler NE, Provensi CL, Rodacki Cde L, Dezan VH. Body mass as a factor in stature change.

Clin Biomech 2005;20:799– 805.

20Wearing SC, Hennig EM, Byrne NM, Steele JR, Hills AP. The biomechanics of restricted movement in adult

As previously noted by Hill and colleagues, obesity is often considered to be a result of assuming too many calories and not getting enough physical activity21. This debate about the role of physical activity and/or dietary regimens is often emphasized in the literature22 -23; however, it seems clear that this discussion has not yet produced effective or innovative solutions.

1.2 Classification of levels in obesity population The terms of body morphology are defined as:

1) Underweight 2) Normal weight 3) Overweight 4) Obesity class I 5) Obesity class II 6) Obesity class III

21Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Peters JC (2012) Energy balance and obesity. Circulation 126:126–132.

22Donini LM, Cuzzolaro M, Gnessi L et al (2014) Obesity treatment: results after 4 years of a nutritional and

psycho-physical rehabilitation program in an outpatient setting. Eat Weight Disord. doi:10.1007/s40519-014-0107-6.

23Hagan RD, Upon SJ, Wong L et al (1986) The effects of aerobic conditioning and/or calorie restriction in

In table 1.1 is shown the classification of adults according to BMI.

Table 1.1: These BMI values are age-independent and the same for both sexes. However, BMI may not correspond to the same degree of fatness in different population due, in part, to differences in body proportion. The table shows a simplistic relationship between BMI and the risk of comorbidity, which can be affected by a range of factors, including the nature of the diet, ethnic group and activity level. The risk associated with increasing BMI are continuous and graded and begin at a BMI above 25. The interpretation of BMI gradings in relation to risk may differ for different populations. Both BMI and a measure of fat distribution are important in calculating the risk of obesity comorbidities.

BMI can be considered to provide the most useful, albeit crude, population level measure of obesity. The robust nature of the measurements and the widespread routine inclusion of weights and heights in clinical and population health surveys mean that a more selective measure of adiposity. BMI can be used to estimate the prevalence of obesity within a population and the risks associated with it, but does not, however, account for the wide variation in the nature of obesity between different individuals and populations

In addition, the percentage of body fat mass increases with age up to 60-65 years in both sexes,24 and is higher in women than in men of equivalent BMI.25

24Rolland-Cachera MF et al. Body mass index variations - centiles from birth to 87 years. European Journal of

Clinical Nutrition, 1991, 45:13-21.

25Ross R et al. Sex differences in lean and adipose tissue distribution by magnetic resonance imaging:

1.3 Health benefits and risks of weight loss

While the effects of obesity on the functioning, health, and quality of life of obese subjects have been studied in great detail, the impact of weight loss is less well documented. Short-term studies have demonstrated clear benefits from modest weight loss on most of the associated consequences of obesity but there are very few well designed studies on the benefits of long-term weight loss. The health benefits and risks of weight loss and of maintaining the new lower weight in the long term are considered here with particular reference to mortality, general health, and obesity related comorbidities including chronic diseases, endocrine and metabolic disturbances, and poor psychosocial functioning.26 Two distinct hazards of weight loss, namely gallstones and reduced bone density, are also considered, as is weight cycling. Finally, a brief account is given of the effects of weight loss in obese children and adolescents. The following should be noted:

1) Well designed studies of the effects of long-term (>2 years) weight loss are few in number. Difficulties associated with such studies include that of maintaining long-term weight loss, and the need to distinguish intentional from unintentional weight loss.

2) Intentional weight loss results in marked improvements in NIDDM, dyslipidaemia, hypertension, cardiovascular risk and ovarian function. There are also improvements in breathlessness, sleep quality, sleep apnea, back and joint pain, and osteoarthritis.

26Forbes GB, Reina JC. Adult lean body mass decline with age: some longitudinal observations. Metabolism:

3) The only distinct hazards of weight loss are an increased incidence of gallstones (when weight loss is rapid) and possibly a reduction in bone density.27

1.3.1 Problems in evaluating the effects of long-term weight loss

Problems in evaluating the benefits of long-term weight loss include:

- the difficulty of maintaining weight loss in adults over a long period;

- whether weight cycling is taken into account, and how it is defined when the outcome of a study is assessed;

- distinguishing "unintentional" weight loss, which may reflect underlying disease, from "intentional" weight loss;

- distinguishing the beneficial effects of weight loss per se from those of the changes in diet and physical activity necessary to achieve it.

The refinement amongst deliberate and accidental weight reduction is of significant importance in investigations of the connections between weight reduction and grimness or mortality. On the off chance that weight reduction happens inadvertently because of hidden aliment or genuine sickness, the relationship between weight reduction and dismalness or mortality will be misleadingly expanded. A predisposition coming about because of misclassification may likewise happen if just two weight estimations are made, particularly if weight reduction is transitory and because of a minor intense disease. Thus it is prescribed

27Goldstein DJ. Beneficial health effects of modest weight loss. International Journal of Obesity, 1992,

that at least three and ideally more weight estimations ought to be made all through the examination time frame.

1.3.2 Weight loss and general health

Modest weight loss

Data from a number of studies have shown that modest weight loss (defined as a weight loss of up to 10%) improves glycemic control, and reduces both blood pressure and cholesterol levels.28 Modest weight loss also improves lung function and breathlessness, reduces the frequency of sleep apnea, improves sleep quality, and reduces daytime somnolence. However, the degree of improvement often depends on the length of time that the condition has been present. Modest weight loss will also alleviate osteoarthritis, depending on the degree of structural damage, as well as back and joint pain.

Extensive weight loss

Following vertical banded gastroplasty, severely obese patients who lose 20-30kg in weight, at a rate of 4.5kg per month for the first 6 months, gain substantial health benefits. They show a marked fall in blood lipids within the first 2 years of follow up, and the condition of 43% of hypertensive patients and 69% of NIDDM patients is improved. Furthermore, at the

28Goldstein DJ. Beneficial health effects of modest weight loss. International Journal of Obesity, 1992,

population level, the incidences of hypertension, hyperlipidemia and NIDDM are reduced to about one-sixth of those seen in obese patients who maintain their excess weight.29-30

Weight loss and mortality

Unfortunately, Unfortunately, most studies on weight loss and mortality have not controlled for unintentional weight loss or for cigarette smoking. In one large study of overweight white women in the USA in which these variables were evaluated, intentional weight loss consistently reduced mortality in women with obesity-related comorbidities such as NIDDM or CVD. However, the effects in women without comorbidities were not consistent with an association between intentional weight loss and reduction in mortality. Thus the benefit of intentional weight loss was best seen in those of poorer health status31.

In a randomized controlled dietary intervention trial of post infarct patients, the effect of dietary intervention on cardiac mortality was greatest among patients who had also lost around 10% of their body weight.32

29Pories WJK et al. Surgical treatment of obesity and its effect on diabetes: 10 year follow-up. American Journal

of Clinical Nutrition, 1992, 55(2 Supp1.):582S-585S.

30Sj6str6m L, personal communication, 1995. Quoted in Bray GA, Coherent preventative and management

strategies for obesity. In Chadwick DJ, Cardew GC, eds. The origins and consequences of obesity. Chichester, Wiley, 1996:228-254 (Ciba Foundation Symposium 201).

31Williamson DF et al. Prospective study of intentional weight loss and mortality in never-smoking overweight

US white women aged 40-64 years. American Journal of Epidemiology, 1995, 141 :1128-1141.

32Singh RB et al. Effect on mortality and reinfarction of adding fruits and vegetables to a prudent diet in the

1.3.3 Impact of weight loss on chronic disease, and on endocrine and metabolic disturbances

Cardiovascular disease and hypertension

A number of cardiovascular risk factors related to blood clotting (haemostatic, rheological and fibrinolytic) have been associated with overweight.33 In particular, coagulation factors VII and X, which are directly associated with BMI, are involved in thrombosis34 and increased risk of myocardial infarction.35

Weight loss induces a fall in blood pressure. Short trials lasting a few weeks show that each 1% reduction in body weight leads, on average, to a fall of 1mmHg (0.133kPa) systolic and 2mmHg (0.267kPa) diastolic pressure.36 Marked falls in blood pressure can occur with very

low energy diets, although modest dietary restrictions are also beneficial.37 Antihypertensive drug therapy, reducing a high alcohol intake, and lowering both dietary salt intake, and saturated fat intake all contribute to further blood pressure reduction independently of weight

33Normalisation of hemorrheologic abnormalities during weight reduction in obese patients. Nutrition, 1987,

3:337-339.

34Effects of changes in smoking and other characteristics on clotting factors and the risk of ischaemic heart

disease. Lancet, 1987, ii:986-988.

35Bettiger LE, Carlson LA. Risk factors for death for males and females. A study of the death pattern in the

Stockholm prospective study. Acta Medica Scandinavica, 1982, 211:437-442.

36Reisin E et al. Effect of weight loss without salt restriction on the reduction in blood pressure in overweight

hypertensive patients. New England Journal of Medicine, 1978, 298:1-6.

37Law MR, Frost CD, Wald NJ. By how much does dietary salt reduction lower blood pressure? Ill- Analysis of

loss.38 It is estimated that a 10kg weight loss can produce a fall of 10mmHg (1.33kPa) in systolic blood pressure and of 20mmHg (2.67kPa) in diastolic pressure.39

Longer trials, with a 10 year follow up of patients identified originally as mildly hypertensive, show that positive dietary change, together with smoking cessation and an increase in isotonic exercise (ex. running), reduces both body weight and blood pressure. These levels can be sustained for 10 years and the need for drug therapy is significantly reduced 40.

Diabetes mellitus and insulin resistance

Studies of weight loss in Non Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus (NIDDM )patients have consistently shown that a weight reduction of 10-20% in obese individuals with NIDDM results in marked improvements in glycemic control and insulin sensitivity. These

improvements can last from 1 to 3 years even if the weight is subsequently regained. In the 75% of newly diagnosed NIDDM patients who are overweight, a 15-20% weight loss in the first year after diagnosis seems to reverse the elevated mortality risk of NIDDM.

However, not all NIDDM patients respond to weight loss with metabolic improvements: the loss of abdominal adipose tissue may be more important in improvements in diabetic control than loss of weight per se.41

Hyperglycemia frequently decreases as soon as a low energy diet is initiated, suggesting that dietary energy restriction has a beneficial effect independently of weight loss. Exercise

38Ferro-Luzzi A et al. Changing the Mediterranean diet: effects on blood lipids. American Journal of Clinical

Nutrition, 1984, 40:1027-1 037.

39Obesity in Scotland. Integrating prevention with weight management. A national clinical guideline

recommended for use in Scotland. Edinburgh, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 1996.

40Stamler J et al. Prevention and control of hypertension by nutritional- hygienic means. Long-term experience of

the Chicago Coronary Prevention Evaluation Program. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1980, 243:1819-1823.

training also improves glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity independently of weight loss. The American Diabetes Association recommends that aerobic exercise should be performed at moderate intensity for 20-45 minutes, 3 days per week42. However, although epidemiological studies have emphasized the value of vigorous activity, mainly because it is easy to assess, total energy expenditure may be the important factor in limiting NIDDM rather than periods of intense physical activity.43

Dyslipidaemia

The levels of blood lipids associated with obesity, namely high triacylglycerides, high cholesterol and low HDL cholesterol, can also be expected to return to normal after modest weight loss. For every 1kg lost, LDL cholesterol has been estimated to decrease by 1%.44

A 10-kg weight loss can produce a fall of 10% in total cholesterol levels, a 15% decrease in LDL levels, a 30% decrease in triacylglycerides and an 8% increase in HDL cholesterol.45

Ovarian function

A weight loss of 5% or more during dietary treatment can improve insulin sensitivity and ovarian function in overweight and obese women with hirsutism and polycystic ovaries.46 In

42American Diabetes Association Position Statement. Diabetes mellitus and exercise. Diabetes Care, 1995,

7:416-420.

43Wareham NJ et al. Glucose tolerance has a continuous relationship with total energy expenditure.

Diabetologia, 1996, 39(Suppl. 1):A8.

44Dattilo AM, Kris-Etherton PM. Effects of weight reduction on blood lipids and lipoproteins: a meta-analysis.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1992, 56:320-328.

45Obesity in Scotland. Integrating prevention with weight management. A national clinical guideline

recommended for use in Scotland. Edinburgh, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 1996.

46Kiddy DS et al. Improvement in endocrine and ovarian function during dietary treatment of obese women with

some obese women with amenorrhoea, normal menstrual function may be restored after weight loss.47

1.3.4 Weight loss and psychosocial functioning

Most studies on the quality of life of obese patients before and after weight loss have been conducted on patients following surgery for obesity, and all show dramatic improvements in the overall quality of life. The SOS study in Sweden48, for example, showed significant improvements in social interaction, anxiety, depression and mental well being that were sustained for 2 years after surgery for obesity. Although it is unclear whether these improvements will be seen with modest weight loss following no surgical intervention, Klem et al.49 recently reported that formerly obese subjects who had lost weight through diet and/or exercise modification found their quality of life to be substantially improved. While this is based on self-reporting by individuals who were maintaining weight losses of at least 13.6kg for periods of over 1 year, it provides additional evidence of the benefits of weight loss.

Dieting is often perceived to have untoward psychological effects, including depression, nervousness and irritability. However, studies have shown that weight loss is associated

47Pasquali R et al. Clinical and hormonal characteristics of obese amenhorrheic hyperandrogenic women before

and after weight loss. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 1989, 68:173-179.

48Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom D. Costs and benefits when treating obesity. International Journal of Obesity

and Related Metabolic Disorders, 1995, 19(Suppl. 6):S9-S12.

49Klem ML et al. A descriptive study of individuals successful at long-term weight maintenance of substantial

with a decrease in depression score, particularly when it is achieved by behaviour modification.50

A dramatic example of how extremely overweight individuals perceive their disorder has been provided by studies of a group of severely obese patients before and after losing weight as a result of gastric surgery.51 Before surgery, all the patients felt unattractive and

the great majority felt that people talked about them behind their backs at work. They also felt that they had been discriminated against when applying for jobs and treated disrespectfully by the medical profession. After having achieved a weight loss of 50kg, all the patients said that they would prefer to be deaf, dyslexic or diabetic or to suffer from severe heart disease or acne than to return to their previous weight. Given a hypothetical choice, they all preferred to be of normal weight than have "a couple of million dollars" a choice that they made in less than a second.

1.3.5 Hazards of weight loss

Weight loss from "crash" dieting may result in acute attacks of gout. However, for intentional and controlled weight loss resulting from medical intervention, only two distinct hazards have emerged from a variety of prospective studies:

• Gallbladder disease. Women who lose 4-1Okg have a 44% increased risk of clinically relevant gallstone disease, and greater weight loss increases this risk. Mobilization of cholesterol from adipose tissue stores is increased during weight loss, so that the risk of

50Smoller JW, Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ. Dieting and depression: a critical review. Journal of Psychosomatic

Research, 1987, 31:429-440.

51Rand CSW, MacGregor AMC. Successful weight loss following obesity surgery and the perceived liability of

supersaturation of bile with cholesterol is greater than when weight is stable. Premenopausal women are at particular risk because of an estrogen induced enhanced biliary secretion of cholesterol.

• Reduced bone density. Bone density is typically increased in obese patients and reduced after weight loss. In white women, weight loss beginning at age 50 was found to increase the risk of hip fracture.52 Whether there is restitution of bone mass with weight regain

following slimming, however, is uncertain; Compston et al.53 found this to be the case whereas Avenell et al.54 did not. There is little information on the impact of weight cycling on bone density.

It should also be noted that, in societies in which overweight and obesity are seen as a sign of affluence, weight loss may be interpreted as an indication of financial disaster.

1.3.6 Weight cycling

Weight cycling refers to the repeated loss and regain of weight that can occur as a result of recurrent dieting. However, there is no standard definition of weight cycling so that comparison between different studies is difficult.55

52Langlois JA et al. Weight change between age 50 years and old age is associated with risk of hip fracture in

white women aged 67 years and older. Archives of Internal Medicine, 1996, 156:989-994.

53Compston JE et al. Effect of diet-induced weight loss on total body bone mass. Clinical Science, 1992,

82:429-432.

54Avenell A et al. Bone loss associated with a high fibre weight reduction diet in postmenopausal women.

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1994, 48:561-566.

55Jeffery RW. Does weight cycling present a health risk? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1996, 63(3

It has been suggested that weight cycling is associated with negative health outcomes, makes future weight loss more difficult and results in a decrease in lean to fat tissue ratio.56

However, the evidence is conflicting; weight variability was associated with increased risk of CVD and all causes mortality in men, particularly in those who continued to smoke, but the association between weight change and death was not seen in the heaviest men.57 Recently

in the USA, the “National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity”58 concluded that the evidence available at the time was that the increased risk was not sufficient to outweigh the potential benefits of moderate weight loss in obese patients.

1.3.7 Effects of weight loss in obese children and adolescents

Weight loss of only 3% significantly decreased blood pressure in obese adolescents, and blood pressure was further improved if exercise was added to the weight loss program59. A weight loss of nearly 16% in obese children resulted in a parallel decrease in serum triacylglycerides and plasma insulin in the first year, with an increase in HDL cholesterol. These changes remained stable in the second year of the study; after 5 years, body weight was still 13% below the initial value, peripheral hyperinsulinemia was reduced and HDL cholesterol remained higher.60

56Lissner L et al. Body weight variability in men: metabolic rate, health and longevity. International Journal of

Obesity, 1990, 14:373-383.

57Blair SN et al. Body weight change, all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality in the Multiple Risk

Factor Intervention Trial. Annals of Internal Medicine, 1993, 119:749-757.

58Weight cycling. National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity. Journal of the American

Medical Association, 1994, 272:1196- 1202.

59Rocchini AP et al. Blood pressure in obese adolescents: effect of weight loss. Pediatrics, 1988, 82:16-23. 60Knip M, Nuutinen 0. Long-term effects of weight reduction on serum lipids and plasma insulin in obese

The symptoms of hepatic steatosis in obese children eventually disappear when excess weight is lost.61

The symptoms of hepatic steatosis in obese children eventually disappear when excess weight is lost.62

1.4 Prevention

Obesity is a public health problem and must therefore be seen from a population or community perspective. Health problems that affect the wellbeing of a major proportion of the population are unlikely to be effectively controlled by strategies in which the emphasis is on individuals. Public health action is based on the principle that promoting and protecting the health of the population requires an integrated approach encompassing environmental, educational, economic, technical and legislative measures, together with a health care system oriented towards the early detection and management of disease.

A public health approach to obesity concentrates on the weight status of the population as a whole, in contrast to interventions that deal exclusively with factors influencing the body fatness of individuals. In many developed and developing countries, underprivileged minority groups have to bear a disproportionally heavy burden of higher than average levels of obesity. Thus, in efforts to remove inequalities in health status as one of the main aims of public health, it is necessary to consider the causes that make particular groups more vulnerable to weight gain.

61Vajro P et al. Persistent hyperaminotransferasemia resolving after weight loss in obese children. Journal of

Pediatrics, 1994, 125:239-241.

62Vajro P et al. Persistent hyperaminotransferasemia resolving after weight loss in obese children. Journal of

This section deals with the need to develop population-based strategies that tackle the environmental and societal factors identified in section 7 as being implicated in the development of obesity.

This is a major area for action in the effective prevention of the global epidemic of obesity. The key issues include the following:

- Obesity is a major global public health problem, and must therefore be approached from a public health standpoint.

- As already mentioned, a public health approach to obesity concentrates on the weight status of the population as a whole in contrast to other interventions that deal exclusively with factors influencing body fatness.

- As the average BMI of a population increases above 23, the prevalence of obesity in that population increases at an even faster rate. A population median BMI range of 21-23 is thought to be the optimum from the point of view of minimizing the level of obesity; adult populations in developing countries are likely to gain greater benefit from a median BMI of 23, whereas those in affluent societies with more sedentary lifestyles are likely to gain greater benefit from a median BMI of 21.

- Appropriate public health strategies to deal with obesity should be aimed both at improving the population's knowledge about obesity and its management and at reducing the exposure of the community to an obesity-promoting environment.

- The two priorities in public health interventions aimed at preventing the development of obesity should be:

• increasing levels of physical activity.

The approaches adopted will depend on the population, and especially its economic circumstances.

- In the past, public health intervention programs have had limited success in dealing with rising obesity rates, although the results of some countrywide "lifestyle programs" are encouraging. However, few programs have concentrated on obesity as a major outcome or have attempted to address environmental influences.

- Current obesity prevention initiatives need to be evaluated, their limitations recognized, and their designs improved. Lessons learned from public health campaigns on other issues can be used to improve public health campaigns on obesity.

- The prevention and management of obesity are not solely the responsibility of individuals, their families, health professionals or health service organizations; a commitment by all sectors of society is required.

- Public health strategies intended to improve the prevention and management of obesity should aim to produce an environment that supports improved and appropriate eating habits and greater physical activity throughout the entire community. Appropriate action needs to be taken to change urban design, transportation policies, laws and regulations, and school curricula accordingly, provide the necessary economic incentives, introduce catering standards, provide health promotion and education, and promote family food production. Priority should be given to public health action in developing and newly industrialized countries to improve the living conditions of all sectors of society, especially within often neglected aboriginal or native populations.

1.4.1 Priority interventions

Regardless of the type of intervention strategy employed to tackle obesity at the population level, two priority interventions important in preventing the development of obesity have been identified in this report, namely increasing levels of physical activity and improving the quality of the diet. The approaches adopted to achieve these aims will depend on the circumstances of the population, and in particular the economic situation. Thus, in developing countries, the main aim of intervention to promote physical activity should be to prevent the reduction in such activity that usually accompanies economic development. In affluent countries, however, the main aim will be to discourage already existing patterns of sedentary behaviour. Likewise, where dietary improvement is concerned, the introduction of new energy dense foods as a replacement for nutritionally adequate traditional diets should be discouraged in developing countries, whereas the already high consumption of high fat/energy dense diets should be reduced in developed ones. Evaluation of interventions is crucial.

1.4.2 physical activity patterns

Cross-sectional data often reveal an inverse relationship between BMI and physical activity63, indicating that obese and overweight subjects are less active than their lean counterparts. However, such correlations do not demonstrate cause and effect relationships, and it is difficult to be certain whether obese individuals are less active because of their obesity or whether a low level of activity caused the obesity. Results of other types of study, however, suggest that low and decreasing levels of activity are primarily responsible; for instance, obesity is absent among elite athletes while those athletes who

63Rising R et al. Determinants of total daily energy expenditure: variability in physical activity. American

give up sports frequently experience an increase in body weight and fatness.64 Furthermore,

the secular trend in the increased prevalence of obesity seems to parallel a reduction in physical activity and a rise in sedentary behaviour. One of the best examples of this is provided by Prentice & Jebb65, who used crude proxies for inactivity, such as the amount of time spent viewing television or the number of cars per household. These studies all suggest that decreased physical activity and/or increased sedentary behaviour plays an important role in weight gain and the development of obesity. This conclusion is further supported by prospective data. Dietz & Gortmaker66, for example, have shown that the amount of television watching by young children is predictive of BMI some years later, while Rissanen et al.67 have shown that a low level of physical activity during periods of leisure in adults is predictive of substantial weight gain (5kg) in 5 years' time. More prospective data will help to clarify this relationship, but it seems reasonable to link physical inactivity with future weight gain.

Physical activity patterns have an important influence on the physiological regulation of body weight. In particular, they affect total energy expenditure, fat balance and food intakes. A Table 1.2 of “Physical activity levels” introduces the concept of physical activity levels (PALs).

64Dietary intake and physical activity as "predictors" of weight gain in observational, prospective studies of

adults. Nutrition Reviews, 1996, 54(4 Pt 2):S101-S109.

65Prentice AM, Jebb SA. Obesity in Britain: gluttony or sloth? British Medical Journal, 1995, 311:437-439. 66Dietz WH, Gortmaker SL. Do we fatten our children at the television set? Obesity and television viewing in

children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 1985, 75:807-812.

67Rissanen AM et al. Determinants of weight gain and overweight in adult Finns. European Journal of Clinical

Table 1.2: Physical activity levels

One of the most important adaptations to regular exercise is the increased capacity to use fat rather than carbohydrate during moderate physical activity. These differences become considerable when the exercise is maintained over a longer period; physically trained individuals metabolize more fat at given levels of energy expenditure than the untrained. It

has been shown, for example, that the rate of fat oxidation in a group of unfit individuals increased by approximately 20% after a 12-week fitness training programme.68

The combination of exercise and diet is more effective than either method alone in promoting fat loss.69 Exercise also limits the proportion of lean tissue lost in slimming regimens70 and limits weight regain71, while physical activity may favourably affect body fat distribution.72

Evidence now suggests that the activity required to maintain and lose weight, and to gain physiological and psychological health benefits, may not have to be as vigorous as was previously believed.73 Indeed, the US Surgeon General's report74 stressed that low intensity, prolonged physical activity, such as purposeful walking for 30-60 minutes almost every day, can substantially increase energy expenditure, thus reducing body weight and fat.

Physical activity strategies should aim at encouraging higher levels of low-intensity activity and reducing the amount of leisure time spent in sedentary pursuits. The main goal is to

68Hurley BF et al. Muscle triglyceride utilization during exercise: effect of training. Journal of Applied

Physiology, 1986, 60: 562-567.

69Skender ML et al. Comparison of 2-year weight loss trends in behavioral treatments of obesity: diet, exercise,

and combination interventions. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 1996, 96:342-346.

70Garrow JS, Summerbell CD. Meta-analysis: effect of exercise, with or without dieting, on the body composition

of overweight subjects. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1995, 49:1-10.

71Wing RR. Behavioral treatment of severe obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 1992, 55(2

Supp1.):545S-555S.

72Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and

Human Services, 1996.

73Despres JP, Lamarche B. Low-intensity endurance exercise training, plasma lipoproteins and the risk of

coronary heart disease. Journal of Internal Medicine, 1994, 236:7-22.

74Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and

convert inactive children and adults to a pattern of "active living". Two general schemes can be envisaged for promoting physical activity:

. Measures to increase modest daily exercise, as in walking or cycling, where the energy expended amounts to about an extra 60- 200kcal1h/h (125.5-251 kJ/h) depending on the intensity of the exercise. In sedentary overweight and obese patients, an extra 3 hours daily of any activity involving standing rather than sitting increases the 24-hour energy expenditure from 40% to more than 75% above the BMR.75

. Physiological fitness training with moderate/vigorous exercise, usually involving group supervised exercise sessions of 45-60 minutes each three times a week. Extensive studies show that these regimens have very substantial benefits but are difficult to sustain in obese patients.

1.4.3 Impact of physical activity on food

There is a common perception that exercise stimulates appetite, leading to an increased food intake that even exceeds the energy cost of the preceding activities. In fact, there is little supporting evidence for this from human studies; if a compensatory rise in intake does occur, this tends to be accurately matched to expenditure in lean subjects so that energy balance is restablished in the long term.76 However, Woo et al.77 showed that obese women

75James WPT, Schofield EC. Human energy requirements. A manual for planners and nutritionists. Oxford,

Oxford University Press, 1990.

76Wilson GT. Behavioral treatment of childhood obesity: theoretical and practical implications. Health

Psychology, 1994, 13:371-372.

77Wilson GT. Behavioral approaches to the treatment of obesity. In: Brownell KO, Fairburn CG, eds. Eating

did not compensate for the higher energy expenditure induced by exercise by increased intake, and thereby obtained a significant negative energy balance on exercise. This suggests that those who have stored an excess amount of energy may particularly benefit from exercise.

In the short term, hunger can be suppressed by intense exercise, and possibly by low intensity exercise of long duration78. The effect is short-lived, however, so that the temporal aspects of exercise induced anorexia may best be measured by the delay in eating rather than the amount of food consumed.79

Whether exercise influences the type of food and the mix of macronutrients chosen by free-living subjects remains uncertain. In a small number of longitudinal studies, a higher intake of carbohydrate rich foods has been observed with an increase in PAL80, and a significant positive relation was recently found between the level of PAL and carbohydrate intake in a diet intervention study.81 However, it is not known whether dietary advice on optimum sport

nutrition or physiological needs helps to initiate such dietary changes.82

More information is needed in order to assess the value of a higher intake of carbohydrate-rich foods in the general population in whom changes in the level of physical activity are relatively small.

78Wilson GT. Behavioral treatment of childhood obesity: theoretical and practical implications. Health Psychology, 1994, 13:371-372.

79Guy-Grand B. A new approach to the treatment of obesity. A discussion. Annals of the New York Academy of

Sciences, 1987, 499:313-317.

80Working Party on Obesity Management. Overweight and obese patients: principles of management with

particular reference to the use of drugs. London, Royal College of Physicians, 1997.

81Bray GA. Use and abuse of appetite-suppressant drugs in the treatment of obesity. Annals of Internal

Medicine, 1993, 119:707-713.

82Wilson GT. Behavioral treatment of childhood obesity: theoretical and practical implications. Health Psychology, 1994, 13:371-372.

CHAPTER 2 - THE BALANCE

2.1 Nervous system and Vestibular system

2.1.1 Vestibular nervous system and structure

The center of the vestibular pathway is contained in the vestibular ganglion, located in the cavity of the vestibule. The peripheral extensions of these opposite-polar neurons lead to the macules of the utriculus and saccule and the ampullary crests. The ampullary ridges act as acceleration sensors; the macules of the utricle and saccule from gravity sense organ. The centripetal extensions of the opposite-polar cells of the vestibular ganglion of the Scarpa, cross the bottom of the internal acoustic meatus, are associated with those cochlear, forming the nerve vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII pair of cranial nerves). Then, they reach the pons Varolii, where they partially end, contracting synapses with the deutoneurons of this nerve path, located in the vestibular nuclei of the bridge.

The vestibular nuclei of the pons Varolii are four and precisely: the upper vestibular nucleus or of Bechterew, lateral or of Deiters, medial or of Shwalbe, inferior or spinal. The fibers that come from the ampoules of the semicircular canals, mainly, are distributed to the upper vestibular nucleus and to the upper portion of the medial nucleus, sending only some fibers to the lower nucleus. The utricular fibers reach the lower and medial nuclei; those that derive from the saccule macules go to the inferior vestibular nucleus.

Some fibers coming from the vestibular receptors do not stop in the vestibular nuclei, but cross the inferior cerebellar peduncle directly reaching the cerebellum. Efferent fibers from different centers spread from the vestibular nuclei. The lateral vestibular nucleus gives rise to a nerves of the lateral-vestibular-spinal tract. These fibers reach the spinal cord at various levels and connect with the motoneurons (A & Y) contained in the grey matter of the anterior horn that control the contraction of muscles. In addition, the Dal nucleo mediale vestibolare prende origine il fascio vestibolo spinale mediale. The medial spinal vestibular beam

originates from the vestibular medial nucleus. It partly constitutes the medial longitudinal fasciculus and partly takes synapse with the motoneurons in the front horns.

Some fibers, deriving above all from the medial vestibular nucleus, go back to the encephalic trunk on the opposite side and reach the lower quadrigemial tubercle and, therefore, the geniculate body. From here, the terminal connection or integration neuron starts, between the medial geniculate body and the cerebral cortex of the temporal lobe, where the perception of the vestibular sense is located. Other fibers, mainly coming from the medial vestibular nucleus, reach the nuclei of the motor nerves of the extraocular muscles, for the regulation of the reflex movements of the eyeball. All the stimuli that come, through the vestibular nerve pathway, to the relative cortical area, determine the possibility of a conscious perception of the orientation and the spatial balance of the human body.83

2.1.2 Neuromuscular spindles and Golgi tendon organs

Neuromuscular spindles. The spindle is disposed between the normal fibers of the skeletal

muscle, called extrafusal fibers. A muscle spindle contains from 4 to 20 small specialized muscle fibers, called intrafusal fibers, and the sensory and motor nerve endings associated with these fibers. a connective tissue covers the neuromuscular spindle and is fixed to the endomysium of the extrafusal fibers. The intrafusal fibers are controlled by specialized motor neurons, called gamma motor neurons, while the extrafusal fibers are controlled by alpha motoneurons.

Figure 2.1: shows how the various fibers are arranged.

The central region of an intrafusal fiber cannot contract itself, because the filaments of actin and myosin are absent or in any case not very numerous. Therefore, the central region can only be lengthened. since the muscular spindle is connected to the extrafusal fibers, when these fibers lengthen, the central region of the muscular spindle is also lengthened.

The proprioceptive fibers transmit the signal that changes the length of the central region of the muscle spindle to the subcortical centers through the spinal cord.

In the spinal cord, the sensory neuron joins synaptically with an alpha motoneuron which causes the reflex muscle contraction (in the extrafusal fibers), to oppose a further lengthening.

gamma motoneurons stimulate the intrafusal fibers, inducing a slight pre-elongation. Even

if the central area of the intrafusal fibers cannot contract, the extremities can do it. Therefore, the gamma motor neurons produce a slight contraction of the ends of these fibers, producing

a live elongation of the central region. This pre-elongation makes the muscle spindle highly sensitive even to a minimal stretch. As a response, the antagonist muscle of the stressed one in elongation contracts.

It is also important to say that the reflex synapse in the spinal cord does not stop there completely. The impulses are also sent to the upper areas of the central nervous system, to provide information on the exact length and the contractile situation of the muscle. These are essential data for maintaining muscle tone and posture and for performing movements. The brain cannot tell a muscle what to do next, without knowing exactly what it is doing at that time.

Golgi tendon organs. The Golgi tendon organs are encapsulated sensory receptors and

traversed by a small bundle of tendon muscle fibers. These organs are located near the insertion of the tendon fibers on the muscle fibers. Generally, there are 5 to 25 muscle fibers connected with each tendon organ of the Golgi. Muscular spindles collect information about the length of a muscle, while the Golgi tendon organs are sensitive to the tension to which the muscle-tendon complex is subjected and function as a "strain gauge", a system that senses changes in tension.

Their sensitivity is such that they can react to the contraction of a single muscle fiber. These sensory receptors are of an inhibitory nature and play a protective function, reducing the risk of injury. When stimulated, these receptors inhibit muscle contraction of the agonists and excite the antagonist muscles.

Some researchers claim that, by reducing the influence of the Golgi tendon organs, a disinhibition of the muscles in activity is obtained and, therefore, a more vigorous muscular action. This mechanism could explain, in part, the increase in muscle strength that follows the specific training for strength.84

2.2 Control of muscle tone and posture

The posture is the position that the body takes at rest or in movement in opposition to the force of gravity. The difficulty of maintaining the upright position depends on the ratio between the width of the support base and the height of the center of gravity. In humans, which is bipedal, the maintenance of balance is particularly complex because the center of gravity is rather high, at the level of the lumbar spine, and the support base is constituted by the relatively small contact surface of the feet.

The information necessary for the control of posture is provided by proprioceptive, vestibular and visual sensory systems and is realized through the tonic contraction of the reflex origin of the anti-gravity muscles. Muscle response is not only the immediate result of the action of different sensory systems, but also depends on the central elaboration of these signals that allows reconstructing spatial coordinates and an internal model of body position. The postural motor responses are in fact the result of the comparison between a global body schema and individual sensory information.

2.2.1 Static proprioceptive responses

The action of gravity in the joints causes the articular angle to open and then the antigravity muscles to stretch. The muscular lengthening extends the neuromuscular spindles which, placed in parallel with the extra-fusal fibers, increase their afferent discharge. The impulses of the spinal cord reach the motor neurons of the same muscles and determine their contraction in such a way as to bring the joint angle back to its initial position.

The action of this reflex, called tonic myotatic reflex, is constant over time and ensures the presence of a muscle tone in the antigravity muscles that in man are the extensors of the lower limb and the flexors of the upper limbs.