REVISTA

BRASILEIRA

DE

ANESTESIOLOGIA

PublicaçãoOficialdaSociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologiawww.sba.com.br

SCIENTIFIC

ARTICLE

Does

fasting

influence

preload

responsiveness

in

ASA

1

and

2

volunteers?

Daniel

Rodrigues

Alves

∗,

Regina

Ribeiras

CentroHospitalardeLisboaOcidental,Lisboa,Portugal

Received23September2015;accepted9November2015 Availableonline16May2016

KEYWORDS

Fasting;

Echocardiography; Fluidtherapy; Hemodynamics

Abstract

Introduction:Preoperativefastingwaslongregardedasanimportantcauseoffluiddepletion, leadingtohemodynamicinstabilityduringsurgeryshouldreplenishmentisnotpromptly insti-tuted.Lately,thistraditionalpointofviewhasbeenprogressivelychallenged,andagrowing numberofauthors nowproposeamore restrictiveapproach tofluidmanagement, although doubtremainsastothetruehemodynamicinfluenceofpreoperativefasting.

Methods:Wedesignedanobservational,analytic,prospective,longitudinalstudyinwhich31 ASA1andASA2volunteersunderwentanechocardiographicexaminationbothbeforeandafter afastingperiodofatleast6hours(h).Datafrombothstaticanddynamicpreloadindiceswere obtainedonbothperiods,andsubsequentlycompared.

Results:Staticpreloadindicesexhibitedamarkedlyvariablebehaviourwithfasting.Dynamic indices,however,werefarmoreconsistentwithoneanother,allpointinginthesamedirection, i.e.,evidencingnostatisticallysignificantchangewiththefastingperiod.Wealsoanalysedthe reliabilityofdynamicindicestorespondtoknown,intentionalpreloadchanges.Aorticvelocity timeintegral(VTI)variationwiththepassivelegraisemanoeuvrewastheonlyvariablethat provedtobesensitiveenoughtoconsistentlysignalthepresenceofpreloadvariation. Conclusion:Fastingdoesnotappeartocauseachangeinpreloadofconsciousvolunteersnor doesitsignificantlyaltertheirpositionintheFrank---Starlingcurve,evenwithlongerfasting timesthanusuallyrecommended.TransaorticVTIvariationwiththepassivelegraise manoeu-vreisthemostrobustdynamicindex(ofthosestudied)toevaluatepreloadresponsivenessin spontaneouslybreathingpatients.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisan openaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:danielralves@sapo.pt(D.R.Alves). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2015.11.002

0104-0014/©2016SociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCC

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Jejum;

Ecocardiografia; Fluidoterapia; Hemodinâmica

Ojejuminfluenciaaresponsividadeàpré-cargaemvoluntáriosASAIeII?

Resumo

Introduc¸ão: Ojejumnopré-operatórioéhámuitotempoconsideradocomoumaimportante causadedeplec¸ãodelíquidos,levandoàinstabilidadehemodinâmicaduranteacirurgia,caso areposic¸ãonão sejaprontamenteinstituída.Recentemente,esse pontodevistatradicional vemsendoprogressivamentedesafiado,eumnúmerocrescentedeautoresagorapropõeuma abordagemmaisrestritivaparaocontroledelíquidos,emborapermanec¸amdúvidasquantoà verdadeirainfluênciahemodinâmicadojejumnopré-operatório.

Métodos: Estudoobservacional,analítico,prospectivoelongitudinal, noqual 31voluntários ASAIeIIforamsubmetidosaexameecocardiográficoanteseapósum períododejejumde nomínimo6horas.Osdadosdosíndicesdepré-cargatantoestáticosquantodinâmicosforam obtidosemambososperíodose,subsequentemente,comparados.

Resultados: Osíndicesestáticosdepré-cargamostraramumcomportamentoacentuadamente variávelcomojejum.Osíndicesdinâmicos,entretanto,forambemmaisconsistentesentresi, todosapontandonamesmadirec¸ão;istoé,nãoevidenciandonenhumaalterac¸ão estatistica-mentesignificativacomoperíododejejum.Analisamostambémaconfiabilidadedosíndices dinâmicospararesponderaalterac¸õespré-cargaintencionaisconhecidas.Avariac¸ãodaintegral develocidade-tempo(VTI)aórticacomamanobradeelevac¸ãopassivadosmembrosinferiores foiaúnicavariávelquemostrousensibilidadesuficienteparasinalizardeformaconsistentea presenc¸adevariac¸ãonapré-carga.

Conclusão:Ojejumnãopareceucausarumaalterac¸ãonapré-cargadevoluntáriosconscientes nemalterousubstancialmenteasuaposic¸ãonacurvadeFrank-Starling,mesmocomtempos dejejummaisprolongadosqueonormalmenterecomendado.Avariac¸ãodoVTItransaórtico comamanobradeelevac¸ãopassivadosmembrosinferioresfoioíndicedinâmicomaisrobusto (dosestudados)paraavaliaracapacidadederespostaavariac¸õesdapré-cargaempacientes respirandoespontaneamente.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologia.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eum artigo OpenAccess sobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Itiscommonknowledgethatprogrammedsurgical interven-tionsshould bepreceded bya fastingperiod.1---3 However,

even though recent guidelines allow for the ingestion of clearfluidsforupto2hbeforeanoperation,indaily clin-icalpracticesuchis seldomperformed, atleast inadults. Infact, itis notunusual for patientstofastfor consider-ablylongerthanrequested,sometimesevenfor10or12h, despitebeingaskedtofastforonlysix.Duringthisperiod, fluiddepletionfromtheorganismisongoing---beitinthe formofperspiration,breathingorurineproduction,among other mechanisms--- andsome authorshave actually esti-matedthatafastingperiodofapproximately12hcanlead to a fluid depletion of around 1L,4,5 which likely causes

somedegreeofintravascularvolumedepletiononcebalance betweendifferentbodycompartmentsinreached.6

According to the Frank---Starling Law, we know that withincertainlimits,strokevolumeiscloselydependenton preload,7,8whichmeansthatadecreaseinpreload

conse-quenttohypovolemiawilltendtodecreasestrokevolume. Theimportanceofthismechanismissuchthatitwas actu-allyfoundtobethemaincauseofunexplainedhypotension with a fall in cardiac output in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) settings.8

Inthehealthy,consciousindividualdifferentmechanisms come into play to compensate for fluid loss,9,10 with the

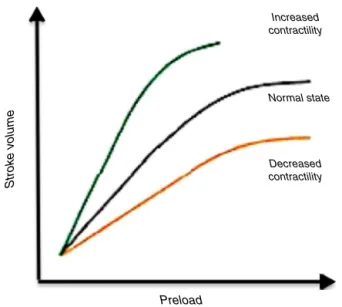

Increased contractility

Normal state

Decreased contractility

Preload

Strok

e v

olume

Figure1 There aredifferentFrank---Starlingcurves for the sameindividual,accordingtohis/herhemodynamicstate.

potentialtoshiftthepatient’sownFrank---Starlingcurveto theleft11---15 (Fig.1)andthusdelay clinicalmanifestations

of intravascular volume depletion.6,16,17 However, when

andafterloadcausedbythedifferentmedicationsused18---26

arelikelyto disrupt thisnewly reached balance and pre-disposeapreviouslystablebutfluiddepletedindividualto hemodynamicdecompensation.

For decades, the traditional reaction of Anaesthesiol-ogists tothis theoretical mechanism was toestimate the fluidlosscausedbyfasting27andsystematicallyreplenishit

withtheintentofrestoringintravascularvolumeandthus the original positionof the patienton the Frank---Starling curve.Allegedly,suchwouldhelpoptimizethepatients’ car-diovascular state and decrease morbidity associated with anaesthesia. Interestingly, though, when real-life studies tried to confirm this, not only were they unable to find evidence for an improved cardiovascular stability profile associated with systematic fluid loading in the intraop-erative period, as there were also indications that this practice might actually be associated with a poorer out-comeincertainofthesettingsstudied.5,10,28---31Infact,some

investigations even found a positive correlation between post-operativeweightgain(duetoexcessivefluidtherapy) andanincreasedmortalityinthesameperiod,32 thus

chal-lengingwhat waspreviouslyconsidered tobean absolute truth.

Severalstudieshaveaddressedtheeffectsoffastingfrom differentperspectives.33---35 Becauseallsufferedfrom

limi-tationsthatadvisedcautionintheinterpretationofresults, however, and given the difficulty in actually measuring intravascularvolumerepeatedlyorfindingasuitable surro-gateforit,thefocusofresearchhasrecentlyshiftedfrom studyingthehemodynamiceffectoffastingitselftofocusing on individual management of any given patient accord-ing to his/her present hemodynamic state, irrespective of fasting time. With this approach, the so-called goal-directed therapy was born.30,36---39 Current goal-directed

therapyprotocols usuallyrely onclassifyingindividuals as either fluid-responsive (thus in the ascending limb of the Frank---Starlingcurve)orfluidnon-responsive(alreadyinthe flat partof the samecurve),29 and haveproduced

signifi-cantlypositiveoutcomes,withsomestudiesactuallyfinding evidenceofimproved survivalsubsequenttoitsuseinthe perioperativeperiod.36,40,41

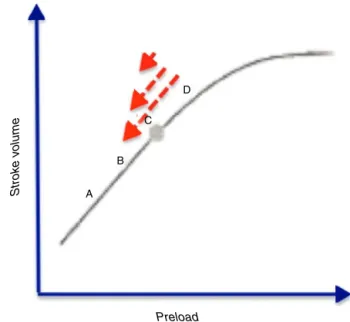

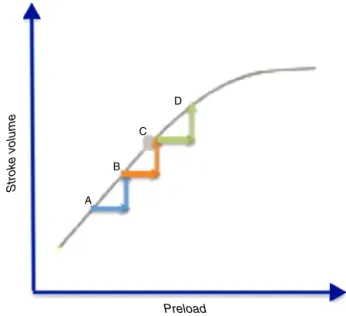

However, goal-directed therapy protocols tend to rely ondataobtained fromspecific monitoring devices,either too invasive and/or too expensive to become universally adopted,whichlimitsitsusetomoreseriouspatientsand/or more aggressive surgeries. As such, what would be the most appropriate course of action when faced with rela-tivelyhealthy(ASA1or2)patientsscheduledfornon-major surgeries?Shouldfastingtimebeconsideredasaguidefor routinefluidreplenishment?Orshoulditsimplybeignored? Adoptingtherationalebehindgoal-directedtherapy,the truequestionbecomes:doesfastingmovethepatienttothe leftontheFrank---Starlingcurve,placinghim/herinan opti-mizablepointthroughanincreaseinpreload(largearrowin

Fig.2),orisitsinfluenceonlyminorinnormalcircumstances (smallarrow)?

Methods

Withthe objectiveof ascertaining the true hemodynamic influenceoffastingandanswering theprevious questions,

Strok

e v

olume

Preload

A B

C D

Figure2 Frank---Starlingcurve.Doesfastingcausea signifi-cantchangeoftheindividual’spositiontotheleftinthecurve (bigarrow),orisitamoremodestinfluence(mediumandsmall arrows)?

Table1 Characteristicsofthesample.

Parameter Characteristics

Sex 16female/15male

Age 26---67yearsold

Average=Median=37yearsold

ASA 71%ASA1

29%ASA2 ComorbiditiesinASA2

volunteers

Asthma,heavysmoking, obesity;nocardiovascular comorbidities.

wedrewonmuchoftheknowledgeaccumulatedwiththe developmentofgoal-directedtherapytoidentifydifferent variables that could estimate preload and fluid respon-siveness. After ethics clearance and obtaining individual informed consent for every participant, we enrolled in our study 31 volunteers classified as either ASA 1 or 2, withoutcardiovascularcomorbidities,aged26---67yearsold

(Table1).Weperformedanechocardiographicexamination

to screen for any abnormalities in the volunteers (which constituted exclusioncriteria- Table 2) andsubsequently acquireddataonthreetypesofvariablesthatwerestudied bothbeforeandafterafastingperiodofatleast6h.These were:

‘‘Conventional’’ variables:weight,heart rate andblood pressure;

Static echocardiographic preload indices: namely tele-diastolic area of the Left Ventricle (LV) acquired from parasternalshortaxisimages(TDAreaLVPSSAx),

teledias-tolicdiameteroftheLVacquiredfromparasternallongaxis imagesinM-mode(TDDLVPSLAx);expiratorydiameterof

theinferiorvenacava(IVCexp)andFlowtimecorrectedin

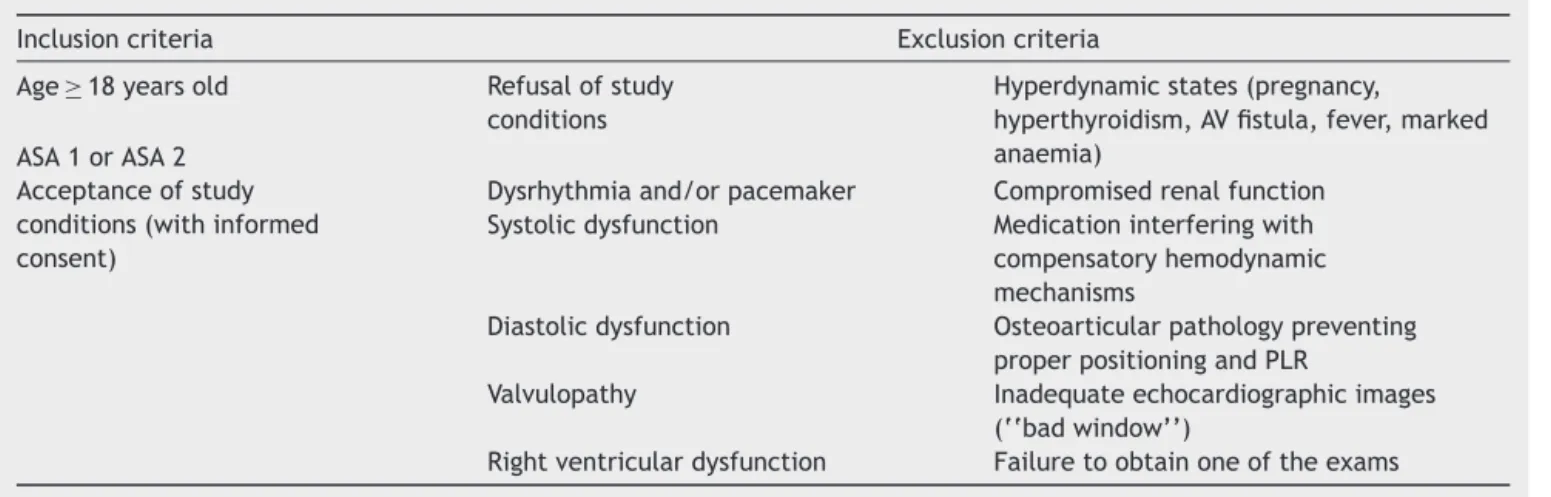

Table2 Inclusionandexclusioncriteria.

Inclusioncriteria Exclusioncriteria

Age≥18yearsold Refusalofstudy

conditions

Hyperdynamicstates(pregnancy,

hyperthyroidism,AVfistula,fever,marked anaemia)

ASA1orASA2 Acceptanceofstudy conditions(withinformed consent)

Dysrhythmiaand/orpacemaker Compromisedrenalfunction

Systolicdysfunction Medicationinterferingwith

compensatoryhemodynamic mechanisms

Diastolicdysfunction Osteoarticularpathologypreventing

properpositioningandPLR

Valvulopathy Inadequateechocardiographicimages

(‘‘badwindow’’)

Rightventriculardysfunction Failuretoobtainoneoftheexams

Dynamicechocardiographic preload indices: obtainedby makinguseof an intentionalvariationofpreload,either through:

• Respiratory variation(heart---lunginteraction): respira-toryvariationofIVCdiameter(respIVC);

• Passive leg raise manoeuvre: more specifically the variation of the transaortic velocity time integral (VTIAo) with the passive leg raise manoeuvre (PLR)

(VTIAoPLR).ThePLRmanoeuvreiscreditedwith

mobi-lizing30042---44---50045mLofbloodintothecirculationand

consistsin movingthe patientfroma semi-recumbent position intoone withthe head of the bed horizontal and the lower limbs raised at a 45◦ angle. In accor-dancewiththeliterature,echocardiographicdatawere acquired between1and 3minafter implementingthis newposition,asithas beenestimated thatafter that time compensatory mechanisms come into play that blunttheeffectsofthemanoeuvre.45

All imageswereacquired bythe sameoperator onthe sameGEVivid 7TMechocardiograph,andlateranalysedby

thesame individualina randomorderthroughtheuseof EchoPACDimensionTMsoftware,inaprocesslaterreviewed

byanindependentobserver.

The data extracted were thenintroduced into an SPSS StatisticsTM database and analysed withthe use of either

parametrictests(Student’sttestforpairedsamples,when there was a normal distribution of the variable in the sample) ornon-parametric tests(Wilcoxon test,when the numberof observationswasunder30and thedistribution ofthevariablewasnotnormal,buttherewasasymmetric distributionofdifferences).

Results

All 31 volunteers underwent a longer fasting period than requested, which varied from 7 to 12.5h (average=10h, standarddeviation=1.4h)---inaccordancewithwhat hap-pensinclinicalpractice.

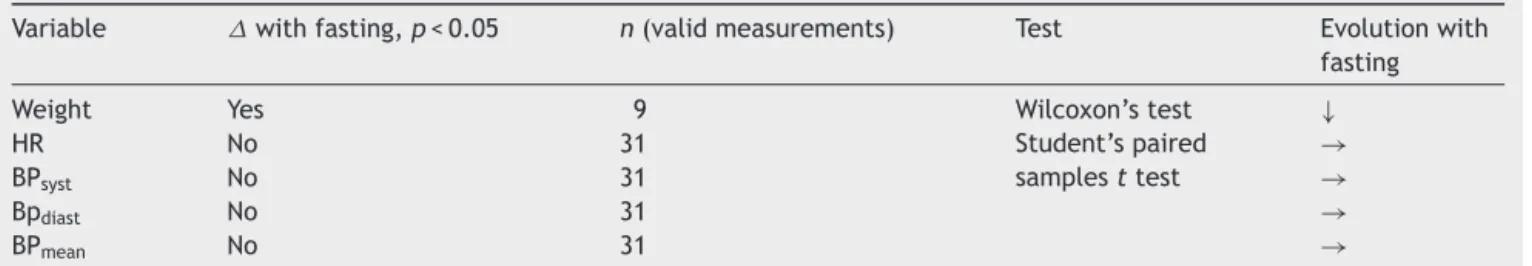

‘‘Conventional’’variables(Table3)

Thevolunteerswereaskedtosupplydataontheevolution ofweightbetweentheirlastmealandaftervoidingonthe pre-fasting day and the following morning (post-fasting), providedthattherewerenobowelmovementsinbetween. Intheseconditions,anydifferencesbetweenmeasurements wouldbeattributabletofluiddepletion. Eventhoughonly 9 of the 31volunteers supplied valid data, there was a statisticallysignificantreductioninthevaluesobtained, cor-respondingto1%ofthebodyweight(approximately700gon average).

Therewerenostatisticallysignificantchangesineither heartrateorbloodpressurebetweenbothmeasurements.

Echocardiographicpreloadvariables

Staticparameters(Table4)

As far as static preload indices are concerned, the behaviourof thedifferentvariablesstudied wasmarkedly dissimilar,with:

• Astatisticallysignificantdecreaseof 6.8%inthe teledi-astolicarea of theleft ventricle(PSSAx) (pointing toa decreasedpreloadafterfasting),

• A statistically significant increase of 9.2% in the Flow time corrected in the descending aorta(pointing to an increaseinpreloadafterfasting,consideringthat periph-eralvascular resistance,which isinversely proportional totheFTcAodandcouldcomplicatetheassessment,also

increasedinthisperiod)

• NochangeintheabsoluteexpiratorydiameteroftheIVC or in the telediastolicdiameter of the LV in PSLAx (M-mode),pointingtotheabsenceofchangeinpreload.

Dynamicparameters(Table5)

As farasthe dynamic preloadindicesstudied are con-cerned,their behaviourwasmarkedlyconsistent between different indices, with nostatistically significant changes oneither the respiratory variations of IVCdiameter or in thevariationofVTIAowiththePLRmanoeuvre.Therefore,

Table3 ‘‘Conventional’’variablesandtheirevolutionwithfasting.

Variable withfasting,p<0.05 n(validmeasurements) Test Evolutionwith

fasting

Weight Yes 9 Wilcoxon’stest ↓

HR No 31 Student’spaired

samplesttest

→

BPsyst No 31 →

Bpdiast No 31 →

BPmean No 31 →

HR,heartrate;BP,bloodpressure;syst,systolic;diast,diastolic.

Table4 Staticpreloadvariablesandtheirevolutionwithfasting.

Variable withfasting,

p<0.05

n Test Evolutionwith

fasting

Degreeofchange

ALVPSSAx Yes(withno

changeindiastolic function)

26 Wilcoxon’stest ↓ −6.8%

TDDLVMMPSLAx No 31 Pairedsamplest

test

→

IVC(Dexp) No 31 →

FTcAod Yes 31 ↑ +9.2%

ALVPSSAx,areaoftheleftventriclemeasuredintheparasternalshortaxiswindow;TDDLVMMPSLAx,telediastolicdiameteroftheleft ventricleusingM-modeintheparasternallongaxiswindow;IVC,InferiorVenaCava;Dexp,Diameterinexpiration;FTcAod,Flowtime correctedinthedescendingaorta.

Table5 Dynamicpreloadvariablesandtheirevolutionwithfasting.

Variable withfasting,

p<0.05

n Test Evolutionwith

fasting

respIVC(CIIVC) No 31 Pairedsamplest

test

→

VTIAoPLR No 31 →

respIVC(CIIVC),respiratoryvariationoftheinferiorvenacava;CIIVC,collapsabilityindex oftheIVC;VTIAoPLR, variationofthe transaorticvelocitytimeintegralwiththepassivelegraisemanoeuvre.

Discussion

As far as vital signs are concerned (namely heart rate andblood pressure),it wasalready mentioned that their change is not a sensitive indicator of volaemic state or fluiddepletion,6,16,17 andthus it came asnosurprise that

there was no significant change in the values obtained betweenbothperiodsinourstudy.Regardingweight assess-ments,eventhoughthenumberofvaliddataobtainedwas small,therewasastatisticallysignificant decreaseinthis parameter,reachingaround1%oftotalbodyweight,which translatedintoanaveragelossof700g.Itisawell known factthatdifferentbodycompartmentsareinconstant bal-ancewithoneanother,andthatmeanswecancalculatehow muchthelossofthismassmeansintermsofintravascular plasmavolumealsolost.Consideringthatonly1/3oftotal bodyfluidisextracellularandthatonlyabout20%ofthese constituteplasmavolume,46,47thena700mLfluidlossina

70kgindividualwouldequateto700×1/3×1/5=46.67mL plasmavolume.Consideringthereducedexpressionofthis value, itseems unlikely that therewould bea significant preloadvariationconsequenttofasting.

Let us move on to the analysis of echocardiographic indices.

andafterload at thatmoment(Fig.1), becausethe same individual hasdifferent Frank---Starlingcurves in different moments.48,49 Given all of theabove,then, it seemsonly

naturalthatourresultsfromdifferentstaticpreload varia-blespointedinmarkedlydifferentdirectionswhenusedin isolationtoassessthecardiovasculareffectsoffasting.

Consequently,itisimportanttoanalyseinsteadthe evo-lutionindynamicpreloadvariablesandfluidresponsiveness. These indices focus onthe behaviour of a given variable in a small timeframe making use of intentional changes in preload, which are usually provoked by either heart-lunginteractions(breathingpattern)orthePLRmanoeuvre. The quick,intentional, reversiblenatureof thesepreload variationsallowsfor themaintenanceofother potentially interfering parameters of cardiovascular state to remain constantbetweenmeasurements,thus makingpreloadthe onlytrulyindependentvariableandlendingincreased reli-ability to the data obtained. It should be emphasized, however,thatintheliteratureonlyIVCinspiratorycollapse and variationof VTIAo with PLR have been validated as a

token of fluid responsiveness in spontaneously breathing patients.50

In ourstudy,theresultsobtainedwithdynamic indices were all coincident: there was no statistically significant changeineitherofthembetweenbeforeandafterafasting period,evenwhenweconsideredthesubgroupofvolunteers whofastedforlonger.

Thoughthesedatastronglysuggestthatfastingdoesnot haveasignificantinfluenceonthehemodynamicstateofthe patient,weconsidereditimportanttoprovethatthe meth-odsusedweresensitiveenoughtodetectpreloadchanges, andthatanegativeresultwouldthus reflectnotalackof sensitivitybutratheratruelackofeffect.Therefore,weput thesevariablesthemselvestothetestbyanalysingtheir evo-lutionafteraPLRmanoeuvre.Knowingthatthismobilizes 300---500mLof blood fromthelower limbsintothe circu-lation, aspreviously mentioned, if the variableused was sensitiveenoughtodetectachangeofthismagnitude,then itshouldshowchangeswiththistest.

The analysis of the results obtained led to interesting conclusions.

Firstly,therespiratoryvariationoftheIVC(andits col-lapsibility index), a preload index that is widely used in theliterature,didnotpassthistest,failingtoconsistently changewiththeuseofthePLR.Suchraisessensitivityissues fortheuseofthisindexinclinicalpractice.

VTIAo,however, consistentlychangedwithPLR, making

VTIAo with PLR the preferred variable to evaluate fluid

responsiveness(andthusevaluatethepositionofthe indi-vidual in theFrank---Starling curve)in our study.Realizing thatitdidnotchangeafterfastingpointstoatrueabsence ofeffectfromthisentityinthehemodynamicstateofthe individual.

We canalsousethis variabletoclassifyourvolunteers in terms of fluid-responsiveness, considering that fluid responders are those in which PLR leads to a significant (10---15%)51 increasein stroke volume(Fig.3)[and thusin

VTIAo, given that stroke volume (SV)=VTIAo×CSA

(cross-sectionalarea−whichisconsideredtobeconstant)].Inthe pre-fastingperiod 10 individuals (roughly one third) were in the ascending limb of the Frank---Starling curve (i.e., werefluidresponders). Ifthe fastingperiodhadcaused a

Strok

e v

olume

Preload

A B

C D

Figure3 Whenanindividualisintheascendinglimbofthe Frank---Starlingcurveanadequateincreaseinpreload(suchas thatobtainedwiththePLRmanoeuvre)leadstoanincreaseof 10---15%instrokevolume.

reduction in preload, then we would expect the average position of the volunteers to be displaced to the left of the curve, and at least some of those 21 non-responsive individualsbeforefastingwouldmigrateintotheascending limbof thecurve.Suchan event,however,didnotoccur, andafterfastingthenumberoffluidresponsiveindividuals waspreciselythe sameas beforefasting:10, which once again confirms the finding that fasting did not alter the volunteers’positionontheFrank---Starlingcurve,nordidit makethemmoreoptimizablebyfluidloading---atleastin thenormal,unanaesthetizedsetting.

Limitationstothestudy

There are some limitations to the present study, which shouldbeconsidered.

Firstly,itis well recognizedthat echocardiographyisa highly user dependent technology, which might skew the results if different operators obtained results that would thenbeanalysedtogether.Toreducethispotentialforbias, allscans wereperformed by thesame operator andlater reviewedbyanindependentobserver.

We must also acknowledge that this was not a blind study.Inordertopreventunintendedpreconceptionsfrom interferingwiththeanalysis,allmeasurementsweremade off-lineinarandomorderasopposedtosequentially,with individualidentificationencodedsoastopreventan imme-diateassociationofresults.

We should also consider the possibility that circadian rhythmmighthaveinterferedwithresults,consideringthat onemeasurementwasmadelateintheafternoonwhereas theotherwasperformedearlyinthemorning.However,the preferentialuse ofdynamicpreloadvariables allowsfora greaterconfidenceintheresultsobtained,decreasingthis interference.

Finally,itwouldbeinterestingtoseehowthese preoper-ativeresultswouldrelatetointraoperativemeasurements, butsuchwasnotpossibleinthisstudybecauseitwasmade withvolunteers,notpatientsundergoingsurgery.

Conclusions

The present studyshowed thatin volunteerswithout car-diovascularcomorbiditiesaperiodoffastingdoesnotseem toaltertheir position in theFrank---Starling curve, mean-ingthereis probablynobenefitfromroutinefluidloading incomparablepatientspresentingforsurgery.Thefactthat thefastingperiodsactuallyfollowedbyvolunteerswasfarin excesstotheonesrequestedlendsfurtherstrengthtothese results,althoughfurtherstudiesrelatingintraoperative to preoperativedatawouldbewelcome.

Finally,we shouldmentionthatthe velocitytime inte-gralvariationoftrans-aorticflowwiththePLRmanoeuvre emergedasthemostreliablevariabletoestimatethe indi-vidual’spositionintheFrank---Starlingcurve.Suchmakesit appropriatenotonlyforinvestigationalpurposes,aswasthe case,butalsotoguidefluidtherapyclinically.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

Theauthors wouldlike toexpresstheirgratitudetowards alltheprofessionalsoftheEchocardiographyLaboratoryof SantaCruzHospitalinLisbon,wheretheinvestigationtook place,totheAnaesthesiologyServiceofCentro Hospitalar deLisboaOcidental(Lisbon,Portugal)formaking it possi-ble,and toall the volunteers whowillingly and selflessly participatedinthestudy,fortheirunwaveringsupport.

References

1.Parameter ASOACOSAP. Practice guidelines for preoperative fastingandtheuseofpharmacologicagentstoreducetherisk ofpulmonaryaspiration:applicationtohealthypatients under-goingelectiveprocedures.Anesthesiology.2011;114:495---511. 2.VermaR,WeeMYK,HartleA,etal.AAGBIsafetyguideline:

pre-operativeassessmentandpatientpreparation---theroleofthe anaesthetist.AAGBI.2010:1---35.

3.SmithI,KrankeP,MuratI,etal.Perioperativefastinginadults andchildren:guidelinesfromtheEuropeanSocietyof Anaes-thesiology.EurJAnaesthesiol.2011;28:556---69.

4.Holte K, Kehlet H. Compensatory fluid administration for preoperative dehydration --- does it improve outcome? Acta AnaesthesiolScand.2002;46:1089---93.

5.Nygren J, Thorell A, Ljungqvist O. Are there any benefits fromminimizingfastingandoptimizationofnutritionandfluid

management for patientsundergoing daysurgery? CurrOpin Anaesthesiol.2007;20:540---4.

6.MorganGEJ,MikhailMS,MurrayMJ.Chapter29---fluid man-agement & transfusion.In: Morgan GEJ, Mikhail MS,Murray MJ,editors.Clinicalanesthesiology.NewYork:LangeMedical Books/McGraw-Hill,MedicalPub.Division;2006.p.690---707. 7.MagderS.Fluidstatusandfluidresponsiveness.CurrOpinCrit

Care.2010;16:289---96.

8.SchmidtC,HinderF,VanAkenH,etal.Chapter3---globalleft ventricularsystolicfunction.In:PoelaertJ,SkarvanK,editors. Transoesophagealechocardiographyinanaesthesiaand inten-sivecaremedicine.London:BMJBooks---BMJPublishingGroup; 2004.p.47---79.

9.Eaton DC,PoolerJP. Chapter44--- basicrenal processes for sodium,chlorideandwater;chapter45---regulationofsodium andwaterexcretion.In:RaffH,LevitzkyM,editors.Medical physiology:asystemsapproach.NewYork:McGraw-Hill;2011. p.437---48,449.

10.KayeAD.Chapter23---fluidmanagement.In:MillerRD,Pardo MCJ,editors.Basicsofanesthesia.Philadelphia:Elsevier Saun-ders;2011.p.364---71.

11.Faber JE, Stouffer GA. Chapter 1 --- introduction to basic hemodynamicprinciples.In:StoufferGA,editor.Cardiovascular hemodynamicsfortheclinician.Oxford:BlackwellPublishing; 2008.p.3---15.

12.SunLS,SchwarzenbergerJC.Chapter16---cardiacphysiology. In:MillerRD,ErikssonLI,FleisherLA,Wiener-KronishJP,Young WL,editors.Miller’sanesthesia.Philadelphia:Churchill Living-stone---Elsevier;2010.p.393---410.

13.MonnetX,TeboulJL.Passivelegraising.In:HedenstiernaG, ManceboJ,BrochardL,PinskyMR,editors.Appliedphysiology inintensivecaremedicine.Berlin,Heidelberg:SpringerBerlin Heidelberg;2009.p.185---9.

14.Monnet X,Teboul JL. Volume responsiveness. Curr OpinCrit Care.2007;13:549---53.

15.SabatierC, MongeI,Maynar J,OchagaviaA. [Assessment of cardiovascularpreloadandresponsetovolumeexpansion].Med Intensiva.2012;36:45---55.

16.NolanJP.Chapter9---majortrauma.In:SmithT,PinnockC,Lin T,Jones R,editors.Fundamentalsofanaesthesia. NewYork: CambridgeUniversityPress;2009.p.156---72.

17.EnglishWA,EnglishRE,WilsonIH.Perioperativefluidbalance. UpdateAnaesth.2005;20:11---20.

18.RevesJG,GlassPSA,LubarskyDA,etal.Chapter26--- intra-venous anesthetics. In: Miller RD, Eriksson LI, Fleisher LA, Wiener-Kronish JP, Young WL, editors. Miller’s anesthesia. Philadelphia:ChurchillLivingstone---Elsevier;2010.p.719---68. 19.White PF, Eng MR. Chapter 18 --- intravenous anesthet-ics. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, Cahalan MK, Stock MC, editors.Clinical anesthesia. Philadelphia:Wolters Kluwer/LippincottWilliams&Wilkins;2009.p.444---64. 20.RosowC,DershwitzM.Chapter42---pharmacology ofopioid

analgesics.In: LongneckerDE, BrownDL,NewmanMF,Zapol WM,editors.Anesthesiology.NewYork:McGraw-Hill;2012.p. 703---24.

21.PowerI,PaleologosM.Chapter7---analgesicdrugs.In:SmithT, PinncockC,LinT,editors.Fundamentalsofanaesthesia.New York:CambridgeUniversityPress;2009.p.584---608.

22.Fukuda K. Chapter 27 --- opioids. In: Miller RD, Eriksson LI, FleisherLA,Wiener-KronishJP,YoungWL,editors.Miller’s anes-thesia.Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2010. p. 769---824.

23.SmithTC.Chapter6---hypnoticsand intravenousanaesthetic agents.In:SmithT,PinncockC,LinT,JonesR,editors. Funda-mentalsofanaesthesia.NewYork:CambridgeUniversityPress; 2009.p.569---83.

MF,ZapolWM,editors.Anesthesiology.NewYork:McGraw-Hill; 2012.p.687---702.

25.EilersH. Chapter9 ---intravenous anesthetics. In:Miller RD, PardoMCJ,editors.Basicsofanesthesia.Philadelphia:Elsevier Saunders;2011.p.99---114.

26.NetoGFD.Capítulo35---Anestésicosvenosos.In:ManicaJ, edi-tor.Anestesiologia:princípiosetécnicas.PortoAlegre:Artmed; 2004.p.560---97.

27.CooperN,CrampP.Chapter5---fluidbalanceandvolume resus-citation.Essentialguidetoacutecare.London:BMJBooks ---BMJPublishingGroup;2003.p.74---102.

28.Chappell D, Jacob M, Hofmann-Kiefer K, et al. A rational approachtoperioperativefluidmanagement.Anesthesiology. 2008;109:723---40.

29.RaghunathanK,McGeeWT,HigginsT.Importanceofintravenous fluiddoseandcompositioninsurgicalICUpatients.CurrOpin CritCare.2012;18:350---7.

30.KirovMY, KuzkovVV, MolnarZ. Perioperativehaemodynamic therapy.CurrOpinCritCare.2010;16:384---92.

31.BamboatZM,Bordeianou L.Perioperativefluidmanagement. ClinColonRectalSurg.2009;22:28---33.

32.Lowell JA, Schifferdecker C, Driscoll DF, et al. Postopera-tive fluid overload: not a benign problem. Crit Care Med. 1990;18:728---33.

33.JacobM,ChappellD,ConzenP,etal.Bloodvolumeisnormal afterpre-operativeovernightfasting.ActaAnaesthesiolScand. 2008;52:522---9.

34.Morley AP, Nalla BP, Vamadevan S, et al. The influence of duration of fluid abstinence on hypotension duringpropofol induction.AnesthAnalg.2010;111:1373---7.

35.OsugiT,TataraT,YadaS,etal.Hydrationstatusafterovernight fastingasmeasuredbyurineosmolalitydoesnotalterthe mag-nitude of hypotension during general anesthesia in low risk patients.AnesthAnalg.2011;112:1307---13.

36.GeisenM,RhodesA, CecconiM. Less-invasiveapproachesto perioperativehaemodynamicoptimization.CurrOpinCritCare. 2012;18:377---84.

37.PinskyMR.Goal-directedtherapy:optimizingfluidmanagement inyourpatient.InitiatSafePatientCare.2010:1---12.

38.Bar-YosefS,SchroederRA,MarkJB.Chapter30---hemodynamic monitoring. In: Miller RD, Eriksson LI, Fleisher LA, Wiener-KronishJP,YoungWL,editors.Miller’sanesthesia.Philadelphia: ChurchillLivingstone---Elsevier;2010.p.406---29.

39.MillerTE,Gan TJ.Chapter11--- goal-directedfluidtherapy. In:HahnRG,editor.Clinicalfluidtherapyintheperioperative

setting. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press; 2011.p.91---102.

40.RhodesA, CecconiM,HamiltonM,etal. Goal-directed ther-apyin high-risksurgical patients: a15-year follow-up study. IntensiveCareMed.2010;36:1327---32.

41.GilCano A, MongeGarciaMI, BaigorriGonzalezF.[Evidence on theutility ofhemodynamic monitorizationin thecritical patient].MedIntensiva.2012;36:650---5.

42.Benington S, Ferris P, Nirmalan M. Emerging trends in mini-mallyinvasivehaemodynamicmonitoringandoptimizationof fluidtherapy.EurJAnaesthesiol.2009;26:893---905.

43.SlamaM,MaizelJ,MayoPH.Chapter10---echocardiographic evaluationofpreloadresponsiveness.In:LevitovA,MayoPH, SlonimAD,editors.Criticalcareultrasonography.USA: McGraw-Hill;2009.p.115---24.

44.KitakuleMM,MayoP.Useofultrasoundtoassessfluid respon-siveness in the intensive care unit. Open Crit Care Med J. 2010;3:33---7.

45.LevitovA,MarikPE.Echocardiographicassessmentofpreload responsiveness in critically ill patients. Cardiol Res Pract. 2012;2012:819696.

46.SkoylesJ.Section2,Chapter2---bodyfluids.In:SmithT, Pin-ncockC,LinT,JonesR,editors.Fundamentalsofanaesthesia. NewYork:CambridgeUniversityPress;2009.p.221---31. 47.Woodcock TE, Woodcock TM. Revised Starling equation and

the glycocalyx model of transvascular fluid exchange: an improved paradigmfor prescribingintravenous fluidtherapy. BrJAnaesth.2012;108:384---94.

48.Slama M, Maizel J. Chapter 6 --- assessment of fluid requirements: fluid responsiveness. In: Backer D, Cholley BP, Slama M, Vieillard-Baron A, Vignon P, editors. Hemo-dynamic monitoring using echocardiography in the critically ill. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg; 2011. p.61---9.

49.Teboul JL,Monnet X.Prediction ofvolumeresponsivenessin criticallyillpatientswithspontaneousbreathingactivity.Curr OpinCritCare.2008;14:334---9.

50.DiptiA,SoucyZ,Surana A,et al.Roleofinferiorvena cava diameterinassessmentofvolumestatus:ameta-analysis.Am JEmergMed.2012;30,1414---9.e1.