´

Relatório Final de Estágio

Mestrado Integrado em Medicina Veterinária

SMALL ANIMAL MEDICINE AND SURGERY Yvette Charlotte Klerx

Orientador

Dr. Miguel Augusto Soucasaux Marques Faria Co-orientador

Dr. Alfred Legendre (John & Ann Tickle Small Animal Teaching Hospital, University of Tennessee)

Relatório Final de Estágio

Mestrado Integrado em Medicina Veterinária

SMALL ANIMAL MEDICINE AND SURGERY Yvette Charlotte Klerx

Orientador

Dr. Miguel Augusto Soucasaux Marques Faria Co-orientador

Dr. Alfred Legendre (John & Ann Tickle Small Animal Teaching Hospital, University of Tennessee)

III

Abstract

This report aims to conclude Integrated Master in Veterinary Medicine. It consists of a brief

description and discussion of five clinical cases that I have followed during my externship at the

John and Ann Tickle Small Animal Hospital of the University of Tennessee, for a total of 16

weeks, with a main focus on the area of Small Animal Medicine and Surgery.

During this period, I had the opportunity to join and participate in specialized areas, going

through different rotations, such as integrative medicine, cardiology, orthopedic rehabilitation,

internal medicine, soft tissue surgery, ophthalmology, oncology and dermatology. My

contribution consisted of performing appointments and physical examinations, presenting

diagnostic and therapeutic plans, assisting or participating in procedures, updating medical

records as well as communicating with clients. Alongside this, I presented clinical cases during

rounds, performed research, discussed recent articles and prepared various presentations.

The realization of this externship was of great relevance to expand and ameliorate my clinical

skills, autonomy as well as self-confidence in execution of duties. The main objectives were

fulfilled by employing maximum focus on all assigned responsibilities, being a team player,

learning how to manage bureaucratic aspect and by interacting with the patient’s owners.

Overall, this externship was an extremely educational and unique experience which has not

only been very significant for my development but will also have a positive impact on my future

IV

Acknowledgements

My sincerest thanks to my mentor, Dr. Miguel Faria, for the availability and useful

suggestions provided through this final stage and entire course. To Dr. Alfred Legendre for

endowing this unique opportunity for many years, for the 24/7 availability and the wonderful

conversations in the Dutch language that made me feel at home. It was a pleasure to meet you.

My mother and father, Anneke and Hans Klerx, to whom this is dedicated. Thank you for

making this possible and supporting me through all my decisions. For believing in me and

encouraging me. For being there and for giving strength when everything seems to be going

wrong. For teaching that hard workers achieve success and that optimism is an important key

for life.

To my one and only sister, Michèle Klerx, for being my role model and best friend. For being

proud of me and matching my level of craziness. For being there even when different countries

separate us from being together. For remaining the same silly sister and for caring about me,

even if we don’t see each other that often. You know I'm proud of you as well.

To the sweetest grandmother, Jet Klerx, my guardian angel.

To Riet Van Riel, my other lovely grandmother for receiving me for one entire month, we had

a fantastic time together.

To Donny and Peer for sharing the same passion for animals, for following me through all

those years and being such a great support.

To Annemiek Van Riel, for the honesty and constructive critic. I appreciate your dedication

and willingness to be involved.

To Joana Portugal for your friendship and all the never-ending conversations we had through

those years. For the adventures and hilarious stories. As I said before, we could write a book!

To Ana Salazar, for the funny emails we exchanged when an Atlantic Ocean was impeding

V

To my Tennessee girls, Daniela Bento, Daniela Martins, Marta Gomes and Sara Dinis. Thank you for being the best roomies in the world. For supporting through ups and downs and for being my lovely American family during those 3 months. To Inês Palhinhas for

understanding that a life without cupcakes and Mexican food is not the same.

To Joana Soares, simply for your enormous support.

To Jessica Miner, the sweetest American girl I met. Thank you for being there for me. And to

all the other amazing people as well as patients, for making this experience unforgettable.

To Franky, for the 14 years of pure happiness. For growing up by my side and teaching me

to appreciate the simple things in life.

VI

List of Abbreviations:

%– Percentage

ACTH – Adrenocorticotropic hormone

ALP– Alkaline Phosphatase

ALT – Alanine aminotransaminase

aPTT – Activated partial thromboplastin time

AT – Adrenocortical tumor

ATH– Adrenocortical tumors causing hyperadrenocoriticism

BAL– Bronchoalveolar lavage

bFGF– Basic fibroblast growth factor

BG– Blood glucose

BID– Twice daily

CBC– Complete Blood Count

CK– Creatine Kinase

Cm– Centimeters

COPD– Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

CO2– Carbon dioxide

cPLI – Canine pancreatic lipase immunoreactivity

CRI – Constant rate infusion

CT– Computerized tomography

cTLI– Canine trypsin-like immunoreactivity

DIC– Disseminated intravascular coagulation

dL– Deciliter

ECG– Electrocardiography

EOD– Every other day

EPI– Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency

FAST– Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma

fL– Femtoliters

flair– Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

Fr – French scale

g– Gram

HDDST– High dose dexamethasone suppression test

HSA– Hemangiosarcoma

ICU– Intensive care unit

IV – Intravenous

IM – Intramuscular

KCS – Keratoconjunctivitis sicca

Kg– Kilogram

VII LDDST– Low dose dexamethasone

suppression test

MAHA– Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia

m2– Square meter

MDR1 – Multidrug resistance protein-1

mEq– Miliequivalents

mg/Kg– Milligram by kilogram

mg/m2– Milligram by meter square

mL– Milliliter

mL/h– Milliliter per hour

mm– Millimeter

mmHg– Millimeter of mercury

mmol– Millimoles

MRI– Magnetic resonance imaging

ng– Nanogram

OS– Left eye

OU– Both eyes

P53– Phosphoprotein p53

PCV– Packed cell volume

PO– Per os

Pg - Picogram

PT– Prothrombin time

QID– Four times daily

Ras– Rat sarcoma

SID– Once daily

T4 - thyroxine

TS– Total solids

Tsc2– Tuberous sclerosis-2

TSH– Thyroid stimulating hormone

UTVMC– University of Tennessee Veterinary medical center

UTI– Urinary tract infection

UV – Ultraviolet light

VEGF– Vascular endothelial growth factor

VPC– Ventricular premature complex

µg– Microgram

µL– Microliter

ºC– Celsius

VIII

Contents

Abstract………..………... III

Acknowledgements………..……….……….... IV

List of Abbreviations……….……… VI

Contents……… VIII

Clinical case Nr. 1: Gastroenterology –Chronic pancreatitis………….………... 1

Clinical case Nr. 2: Pulmonology –Chronic bronchitis ………..… 7

Clinical case Nr. 3: Soft Tissue Surgery –Adrenalectomy ………. 13

Clinical case Nr. 4: Ophthalmology –Descemetocele ………. 19

Clinical case Nr. 5: Oncology –Splenic hemangiosarcoma ………... 25

Appendixes Appendix I ………...… 31

Appendix II ……….. 33

Appendix III ………... 34

Appendix IV ……….... 36

1

Clinical case Nr. 1: Gastroenterology - Chronic pancreatitis

Characterization of patient and reason of appointment: Blackjack is a 9 year old, male castrated, 35 Kg, Labrador Retriever, that was presented to the UTVMC Emergency service

with signs of acute lethargy and vomiting with the duration of one day.

Anamnesis: Blackjack had all vaccines up to date and was dewormed regularly. He lived indoors with private/public outdoor access and had the tendency to go into trash, plants or toxic

agents. The diet was inconstant, ranging from a miscellaneous human diet to a low fat

veterinary prescription diet. According to medical history, three cases of pancreatitis had been

reported within the last year. Although the recurrence, he recovered successfully from all

episodes. During this period, he had three other episodes at home and the owners treated by

withholding food for one day and reintroducing it gradually (Royal Canin GI Low Fat® or a

homemade sweet potato with chicken), and by giving maropitant, tramadol and acepromazine.

This last episode, the vomiting initiated immediately after a walk through a park, and consisted

mainly of bile. In the morning, Blackjack was lethargic, unable to stand, had polydipsia, anorexia

and a mild cough. However, his stools and urination were normal. Physical exam: Blackjack was presented in sternal recumbency, mildly dehydrated (7%) and had tacky mucous

membranes. Femoral pulse was weak but with a normal rate. The respiratory rate was normal.

No crackles or wheezes were ausculted. Additionally, he had occasional non-productive cough

and a rectal temperature of 38.9°C. Gastrointestinal examination: Superficial and deep abdominal palpation did not reveal clear signs of pain or discomfort. Examination of head,

esophagus, abdomen and rectum did not evince significant changes. List of problems: Lethargy, vomiting, cough, anorexia, polydipsia, dehydration, weak pulse. Differential diagnosis: Dietary indiscretion, intolerance or allergy; IBD; lymphangiectasia; gastrointestinal obstruction due foreign body, neoplasia or stricture; pancreatic abscess; EPI; acute/chronic

pancreatitis; aspiration pneumonia; infectious pneumonia (B. bronchiseptica, S. zooepidemicus, P. multocida, P. aeruginosa or K. pneumoniae). Diagnostic tests: FAST (Focused assessment with sonography for trauma) scan - Ascites. Abdominocentesis - Exsudate with moderate

neutrophilic inflammation (Appendix I, table 3). PCV and TS: 56% and 8.0 g/dL. Blood glucose -

114 mg/dL. Lactate - 1.9 mg/dL. Blood pressure - 85 mmHg. Complete blood count - Left shifted

neutrophilia, lymphopenia and mild thrombocytosis (Appendix I, Table 1). Chemistry panel -

Mildly elevated liver enzymes, elevated creatine kinase and hypercholesterolemia (Appendix I,

Table 2). PT / aPTT - 8.2 / 24.9 seconds. Abdominal ultrasound - Moderate abdominal effusion,

hypoechoic pancreas with irregular margins, hyperechoic fat surrounding pancreas and other

organs in cranial abdomen; two hyperechoic splenic nodules. Abdominal and Thoracic

2

inflammation and possible fibrosis; findings consistent with acute pancreatitis. Diagnosis: Chronic pancreatitis with acute flare-up and aspiration pneumonia. Treatment and evolution: Blackjack was hospitalized and remained in the ICU for 6 days. Day 1 - He received a poly-ionic solution (Plasmalyte A®) at 288 mL/h IV, and later a 350 mL IV bolus to correct hypovolemia.

Fentanyl with lidocaine IV at CRI of 1.4-2.8 mL/h was provided as pain management. In order to

control the aspiration pneumonia and prevent from sepsis, 1050 mg of ampicillin/sulbactam

(Unasyn®) IV TID was provided as well. Additionally, 35 mg of maropitant and pantoprazole IV

SID was given to control nausea and hyperacidity, respectively. The primarily given fluid bolus

drastically improved his mentation and blood pressure (120 mmHg), allowing him to stand. He

had no vomiting or diarrhea while hospitalized. Day 2 - A 250 mL fresh frozen plasma transfusion was provided during 4 to 6 hours to correct the hypoalbuminemia. He received 2

mg/kg IM SID of diphenhydramine (Bendadryl®) preceding the plasma transfusion as prevention

for possible anaphylactic reaction. In the afternoon, Blackjack began to have increased

respiratory rate and ptyalism, indicative of severe pain. The pain management was reassessed

and the fentanyl-lidocaine rate increased. Amylopectin (Vetstarch®), a synthetic colloid was

added at 20 mL/h as attempt to reduce fluid retention. Abdominal circumference was

re-evaluated on a daily basis (increased from 83.8 to 88.9 cm). Day 3 and 4 – The abdominal circumference decreased to 61 cm and to 55.9 cm, respectively. At this point, the patient was

kept on the same medication, and an ultrasound guided FNA of the pancreas confirmed the

diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. As anorexia persisted, a nasogastric tube was placed and was

fed with 4 mL/h of a peptide-based nutrition for metabolic stess (Perative®). Day 5 - The nasogastric tube came out after a sneezing episode but the appetite returned gradually. The

fluid therapy was reduced and the pain management adjusted accordingly. Day 6 - Blackjack's blood work showed no abnormalities, so he was sent home with oral omeprazole (40 mg), a

broad spectrum antibiotic (amoxicillin and clavulanic acid 375 mg) and strict instructions for a

consistent low fat diet. Prognosis: Fair if strict low fat diet is followed and recurrences are avoided.

Discussion: Pancreatitis may be classified as acute or chronic and is a condition that consists of pancreatic hyperstimulation caused by premature enzyme activation, leading to

severe inflammation.1,2,3 It’s a very common but under-diagnosed disease, affecting any breed,

age or sex.2,3 The most frequently affected breeds are Miniature Schnauzer, Shetland

Sheepdog, Yorkshire Terrier, Boxer, Spaniels, Terriers and Collie, while the age range is

between 5 to 9 years old.1,2,3 The breed predisposition suggests the existence of a possible

underlying genetic predilection as well as an emerging association in some breeds with

imune-mediated diseases (Cocker Spaniel), especially correlated to keratoconjunctivitis sicca.1

3

50% develop diabetes mellitus, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, or both.1 However, approximately 90% of the cases are idiopathic with no evident cause, others than a possible

hereditary factor.1 A less frequent cause might be duct obstruction or bile reflux to pancreatic

duct.1 The idiopathic form seems to be particularly common in Spaniels, Collies and Boxers.1,2

According to some studies, many dogs with pancreatitis are obese or have subclinical

endocrinopathies associated, such as hyperadrenocorticism, hypothiroidism and diabetes

mellitus.3,8 Other studies propose a mild increased risk in female dogs and with the use of certain medications such as, potassium bromide, phenobarbital, azathioprine, and

L-asparginase, as well as diet indiscretion.3,8 Although severe hypertriglyceridemia has not yet

been proven to be an exact cause in dogs, others than the Miniature Schnauzer, it is presumed

that it might have impact on the disease in dogs of all breeds.3

The main function of the exocrine pancreas is secreting digestive enzymes, bicarbonate and

intrinsic factor into the proximal duodenum.1 The function of those enzymes is to achieve

primary digestion of the larger food molecules which mostly requires an alkaline pH

environment.1 The pancreas itself, secretes several other enzymes, implicating α-amilase and

lipase as active molecules and proteases, phospholipases, ribonucleases and

deoxyribonucleases as inactive precursors, or also known as zymogens.1,2 However, tryspsin, a

serine protease, is the major inactive zymogen that is activated by zymogen trypsinogen

contained by the pancreatic acini.1 Consequently, trypsinogen is activated by the enzyme

enterokinase localized within the duodenum in response to intraluminal fat and amino acids.1,2

This causes peptide cleavage and results in activation of trypsin, which then leads to activation

of other zymogens within the intestinal lumen.1,4 In addition to this, other factors can contribute

to pancreatic secretion.1,2 Those involve the enteric nervous system, the vagus nerve and the

hormones secretin and cholecystokin.1,2 Pancreatitis is often a self-limiting process but may

progress to pancreatic necrosis due to reduced pancreatic blood flow, leukocyte and platelet

migration, leading to electrolyte and acidbase imbalance.4 While in chronic pancreatitis the most

common findings are low cellularity, lymphocytic or neutrophilic infiltration, with irreversible

fibrosis and atrophy, in the accute form of the disease it is more suggestive to find

hypercellularity, neutrophilic infiltration (intact and degenerated), degenerated pancreatic acinar

cells, pancreatic necrosis, peripancreatic fat necrosis and edema.2,3

The clinical signs may vary from anorexia, vomiting and diarrhea, abdominal pain, lethargy or

weakness but no pathognomonic signs exist for canine pancreatitis.3 A study concluded that the

signalment on presentation was similar in acute and chronic pancreatitis, of which the most

frequent were lethargy, inappetence, vomiting and diarrhea.9 However, other recent reports

proved that pancreatitis can be subclinical, occurring with lethargy and weakness as very mild

4

such as icterus, fever or hypothermia, dehydration, hemorrhage, diathesis, ascites or even

cardiovascular shock, DIC and multiorgan failure.3 Blackjack had evidence of anorexia, vomiting

and lethargy but no apparent abdominal pain or diarrhea.

In terms of diagnostics, a complete blood count, biochemical panel and urinalysis are not

specific but might give an indication of the disease and should always be included to rule out

other differentials.1,3 The clinicopathologic findings are often normal in mild cases, however

anemia or hemoconcentration, leukocytosis or leucopenia, as well as thrombocytopenia can be

some of the abnormalities.3,4 Other than this, electrolyte imbalance, elevated hepatic enzyme,

hyperbilirubinemia or azotemia due dehydration may be appreciated.3,4 Measurement of serum

amylase or lipase activity is often reported on routine biochemical panels. Anyway, there are

several typical pancreatic enzyme assays of which serum cPLI concentration is considered the

most sensitive (64-93%) and specific available, comparing to cTLI (36.4-46.7%), serum amylase

activity (18.2-73.3%), serum lipase activity (13.6-69%) and abdominal ultrasound (67-68%).3 For

Blackjack these testing was not essential regarding the obvious history and diagnostic findings.

Regarding the low sensitivity (24%), the diagnosis can not be based on abdominal radiographs

solely.3 Nonetheless, typical radiographic findings such as Blackjack’s, involve an increased soft

tissue opacity with decreased serosal detail, especially in the right cranial abdomen which is

indicative of localized peritonitis.3,4 Occasionally, it is possible to identify punctiform calcification

in longstanding diseases, which is mainly caused due saponification of mesenteric fat around

the pancreas.4 In case of acute disease, gaseous dilation of bowel loops or displacement of the

stomach and duodenum, abdominal effusion, as well as, intestinal obstruction and false

masslike appearance caused by surrounding fat necrosis may be identified.1,3 Ultrasonography

is considered the most sensitive (68%) technique to obtain accurate visualization of the

pancreas.3 Some of the characteristic ultrasonographic findings consist of hypoechoic and

enlarged pancreas, dilated pancreatic duct, swollen hypomotile duodenum, biliary dilation,

peritoneal fluid and cavitary lesions such as abscess or pseudocyst.4 Performing a correct

measurement of the pancreas might help diagnosing abnormal morphological changes in size,

which seems to be more subtle in chronic pancreatitis and EPI, than in acute pancreatitis.6

Other advanced imaging modalities have not been proven worth cost-effective results in

veterinary medicine, and beside that, have a high complexity level associated and limited

availability.3 Given that no single specific modality is totally reliable, abdominal ultrasonography

in combination with histopathology or cytology are vital for a truthful diagnosis.3,4 In any case of

pancreatitis, histology is highly from all, the gold standard and is ultimate to differentiate

inflammation from possible neoplasia.1,5 According to one study, some dogs with chronic

pancreatitis were erroneously diagnosed with chronic hepatitis on basis of increased serum

5

histologically.5 Chronic pancreatitis appears to be associated with reactive hepatitis but not

chronic hepatitis.5 For Blackjack, a biopsy or a fine needle aspirate were both suggested and

after explaining the advantages and disadvantages of both modalities, the last option was

chosen by the owners. The fine needle aspirate is clearly the less risk-associated method but

not the most diagnostic.3,4,5

Therapeutically, canine pancreatitis consists mainly of symptomatic treatment.3,4

Dehydration, hypovolemia and consequent tissue hypoperfusion with diminished pancreatic

microcirculation might have effect on the development of local and systemic complications and

are so, a reason to perform a proper fluid therapy.3 The treatment of choice is the replacement

with isotonic fluid solutions such as 0.9% NaCl or lactated Ringer’s solution, but it is unclear

which shows the best results.3,4 The fluid therapy consists of a 10 mL/kg bolus with 5

mL/kg/hour rate for the first 8 hours.10 According to response, the bolus can be discontinued

and the rate can be decreased to 2.5 mL/kg/h if responded adequately, or the same bolus and

rate can be repeated if the patient is refractory, monitoring carefully for fluid overload.10 More

severely affected animals may require initial shock rates (90 mL/kg/h for 30 to 60 minutes)

followed by synthetic colloids.1 Synthetic colloids and plasma administration may purpose

benefits due the proteinase inhibitors as component, which is responsible for the correction of

hypoalbuminemia, replacement of α-macroglobulins and coagulation factors, as well as

improvement of systemic inflammation.10 Electrolyte imbalance such as hypokalemia, should be

considered since most of the fluid solutions contain only 4 mEq/L of potassium when most

cases require at least 20mEq/L.1 The correction can be achieved with potassium chloride IV at a

rate of 0.15 to 0.5 mEq/kg/h.1

Analgesia is the next step of the treatment approach, as pancreatitis causes severe

abdominal pain and discomfort which should not be underestimated. Buprenorphine can be an

excellent option for mild to moderate pain, while morphine, hydromorphine, methadone or

fentanyl are best for severe pain.3 Blackjack was submitted to a multimodal pain management,

combining fentanyl with lidocaine, allowing not only to lower dosages, but also to diminish side

effects. Other options for combined pain management are ketamine or morphine.3 The

prophylactic use of antibiotics has no proven benefits and ins regarding to this, only

recommended in infectious complications, such as Blackjack’s aspiration pneumonia.3

Blackjack

received a broad spectrum antibiotic (ampicillin/sulbactam), but metronidazole, ciprofloxacin or

chloramphenicol are other alternatives that have the ability to achieve therapeutic levels in the

pancreas.3 As management of emesis and high susceptibility to gastroduodenal ulcers,

Blackjack received maropitant and pantoprazole, respectively. Other antiemetics as

metoclopramide seem to be very effective but not ideal, since it may increase pancreatic

6

Nutrition management is an essential step that has been changing along the years.1,2,3 While

initially food withholding was recommended, now the opposite is accomplished in practice.1,2,3 It

is recognized that patients should not be withhold of enteral nutritional support for longer than

24 hours, and that parenteral and enteral nutritional support are both better alternatives than

providing none.3,4 In case of absence of vomiting signs, the patient should be fed by mouth and

if anoretic, a feeding tube should be placed.3 A jejunostomy tube should only be considered in

animals with refractory vomiting or severe pancreatitis, enduring exploratory or therapeutic

laparotomy.1,3,4,10 The selection between parenteral or enteral is mainly made according to

toleration of the patient, since the application of the latter is more complex.3

Beside this, a continued fat restriction or a strict and balanced low fat diet is currently the

preferred option for dogs.3,4 Surgical intervention is rarely an indication but may be necessary

regarding the sequels that chronic or recurrent inflammation can cause, involving pancreatic

abscess or pseudocysts, necrotic masses and extrahepatic biliary tract obstruction.3,4

The prognosis for dogs with pancreatitis is difficult to foretell in order to the unpredictable

nature of the disease, depending mainly of the severity on presentation and complications

associated.1,3,4 This way, patients such as Blackjack, with acute flare-ups require exactly the

same intense treatment as those who present with the classical acute form, covering the

equivalent risk of mortality.1

References:

1- Nelson R.W, Couto C.G (2009) “The Exocrine Pancreas” in Small Animal Internal Medicine, 4th edition, Mosby Saunders, 579-596.

2- Steiner J. M (2010) “Canine Pancreatic Disease” in Ettinger S.J, Feldman E.C Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 7th edition, Saunders Elsevier, vol 2, 1296-1315.

3- Washabau R.J (2012) “Diseases of Gastrointestinal Tract” in Washabau R.J, Day M.J Canine and Feline Gastroenterology, 1st edition, Saunders Elsevier, 799-811.

4- Simpon K. W (2003) “Diseases of the Pancreas” inTams T.R Handbook of Small Animal Gastroenterology, 2nd edition, Saunders Elsevier, 353-365.

5- Watson P.J, Roulois A.J, Scase T.J, Irvine R, Herrtage M.E (2010) “Prevalence of hepatic lesions at post-mortem examination in dogs and association with pancreatitis” in Journal of Small Animal Practice, 51, 566-572.

6- Penninck D.G, Zeyen U, Taeymans O.N, Webster C.R (2012) “Ultrasonographic measurement of the pancreas and pancreatic duct in clinically normal dogs” in American Journal Veterinary Research, Vol 74, No.3, 74, 433-437.

7- Watson P.J, Roulois A.J, Scase T.J, Holloway A, Herrtage M.E (2011) “Characterization of Chronic Pancreatitis in English Cocker Spaniel” in Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 25, 797-804.

8- Watson P.J, Roulois A.J, Scase T.J, Johnston E.J, Thompson H, Herrtage M.E (2007) “Prevalence and breed distribution of chronic pancreatitis at post-mortem examination in first-opinion dogs” in Journal of Small Animal Practice, 48, 609-618. 9- Bostrom B.M, Xenoulis P.G, Newman S.J, Pool R.R, Fosgate G.T, Steiner J.M (2012) “Chronic pancreatitis in dogs: A

retrospective study of clinical, clinicopathological, and histopathological findings in 61 cases” in The Veterinary Journal, 195, 73-79

7

Clinical case Nr. 2: Pulmonology - Chronic bronchitis

Characterization of patient and reason of appointment: Maximus was a 6 year old, male castrated, 25 Kg, English Bulldog, that was presented to the UTVMC Emergency service with a

history of chronic coughing which initiated approximately one month ago.

Anamnesis: Maximus was an indoors dog that was walked in a public environment several times a day. The diet was based on dry food (Purina Light & Healthy®

)

. Recently, Maximus wasvaccinated for distemper, parvovirus, adenovirus type 1, parainfluenza, leptospirosis and rabies,

and was dewormed regularly. The cough initiated approximately one month ago and had

progressively worsened. One month prior to this, he was treated by the referring veterinarian

with trimetoprim/sulphadiazine (Tribrissen®) but did not seem to improve. After this first

treatment attempt, he boarded twice regarding the cough. Concerning to medication, he was

receiving prednisone 20 mg EOD, doxycycline 100 mg BID and milbemycinoxime with lufenuron

(Sentinel®) for heart worm prevention. Physical exam: The lung sounds were mildly decreased on the left thorax. Thorough cardiovascular examination did not reveal any signs of cardiac

dysfunction and rectal temperature was 39.2 ºC. Respiratory exam: Decreased lung sounds, more intense on the left side of the thorax with very mild crackles. Both nares were slightly

stenotic, frontal sinuses sounded normal on percussion, larynx and trachea were normal on

palpation. List of problems: Cough, decreased lung sounds, mild crackles. Differential diagnosis: Brachycephalic airway syndrome, chronic or allergic bronchitis, aspiration pneumonia, dirofiloriasis, carcinoma, lymphoma, granuloma, blastomycosis, histoplasmosis,

bacterial pneumonia or bronchitis caused by B. bronchiseptica, S. zooepidemicus, P. multocida, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia, Mycoplasma spp. Diagnostic tests: Complete blood count - No significant changes. Chemistry panel - Mild hyperglobulinemia (3.8 g/dL) and mild elevation in

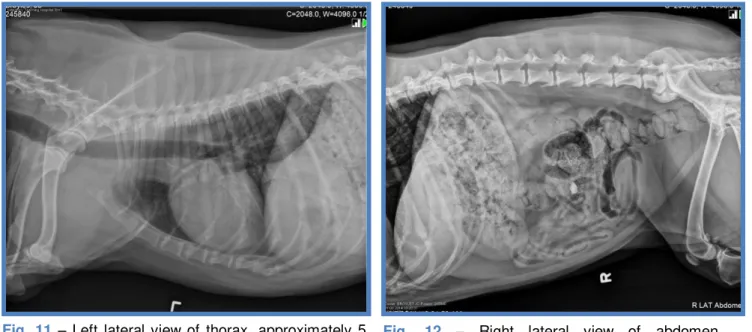

bicarbonate (26mmol/L). Thoracic radiographs - Mild bronchial pattern and bronchial wall

mineralization (Appendix II, Fig. 4, 5 and 6).

Maximus remained in ICU for respiratory watch during the first hours and was released in the

afternoon. Maximus' state was not critical and so, he was discharged in the condition of

returning in the morning fasted. In order to perform a flexible bronchoscopy with

bronchoalveolar lavage for cytology and culture, which is considered the gold standard to

diagnose chronic bronchitis. An elongated soft palate, as well as, mildly thickened bronchial

mucosa, slightly thickened mucus accumulation in bronchioles and hyperemic trachea were

appreciated. During the bronchoscopy, coupage was used to release mucus and promote coughing in contemplation of obtaining samples from the deeper airways. Bronchoalveolar

lavage - Low grade neutrophilic to mixed (few lymphocytes) inflammation and goblet cell

8

Diagnosis: Maximus was diagnosed with sterile chronic bronchitis. Treatment and evolution: He was discharged the same day of the bronchoscopy, but no medication was prescribed.

However, an antihistamine, such as cetirizine hydrochloride (Zyrtec®) at 5 to 10 mg, was

suggested as trial in pursuance of evaluating, whether or not existed an allergic or seasonal

component to the disease. Any irritants within the household or environment were suggested to

be removed or minimized as prevention. Other recommendations were to continue the

prednisone but on a dose of 25 mg for 2 weeks, then decreasing it to the lowest effective dose,

with a 25 to 30% decrease every 2 weeks until reaching an effective maintenance dose.

Alternatively, inhaled corticosteroids were indicated, such as fluticasone at 125 µg BID

associated with a special inhaler for dogs. In addition, theophylline at 10mg/kg PO BID was also

suggested. For the worsening periods of the cough during night time, a cough suppressant was

indicated, as long as the cough continued to be non-productive (hydrocodone 5.5 mg QID-BID

as needed or diphenoxylate 5 to 12.5 mg BID until the cough was under control, and then, as

needed). Prognosis: Good to fair.

Discussion: Canine chronic bronchitis is a longstanding inflammation of the lower airways that can present different etiologies. Those can enclose an infectious, toxic or alergic cause and

it usually emerges with evident signs of coughing of at least two months of duration in one

consecutive year.1,2,3,4 The etiology is often unknown, but the disease itself is a reflection of

repeated inflammatory sequences that leads to mucosal damage, mucus hypersecretion,

obstruction of the airways and thus, disturbed mucociliary clearance.2,4 Consequently,

predisposition to infections can occur due to reduced defense mechanisms.1,4 Other potential

etiologies for increased secretion in the bronchi are atmospheric pollution, such as chronic

exposure to sulfur dioxide, passive smoking in poorly ventilated and confined spaces,

respiratory tract infections, hypersensitivity to certain allergens and genetic or acquired defects

such as α1-antitrypsin deficiency, immunodeficiency and mucociliary defects.1 The breeds

affected are generally middle-aged to older small breed dogs, which can be related to the high

susceptibility to mitral valve insufficiency and tracheal collapse.1,3,4 However, Cocker Spaniels,

Poodles and Terriers appear to be the principal breeds involved.3,4 Several other diseases can

lead to coughing, giving especial emphasis to the cardiac diseases that arise isolated or

simultaneously with a coadjuvant pulmonary condition, such as bronchitis.3,4 The major heart

diseases that can accompany coughing are left atrial dilation due to valvular insufficiency or

generalized cardiomegaly, pulmonary hypertension and congestive heart failure.4 Nonetheless,

in presence of a heart murmur, the chronic cough is more likely to have pulmonary than cardiac

origin.3 Whereas in younger dogs it is important to search for an infectious disease, in older

dogs a neoplasic cause should be considered as well. The most common neoplasias that may

9

sterile chronic bronchitis is mainly made by exclusion.2,3 It is of great relevance to obtain a

detailed history in order to determine a possible environmental or infectious cause, evaluating

the frequency, pattern and development of the cough and differentiating it from another possible

underlying or primary disease.1,2,3,4 Physical examination may reveal normal to increased lung

sounds, with occasional expiratory wheezes or pan-inspiratory crackles.2 Other signs are

expiratory dyspnea and if more severe, exercise intolerance and collapse.2,3 However, most of

the dogs with chronic bronchitis are geriatric and seem to be systemically healthy, presenting

with only one exclusive chief complaint, which is persistent and productive cough.3 This is

similar to Maximus, that was presented with one main clinical sign, chronic coughing, although,

non-productive. Additionally he had diminished lung sounds on the left side of the thorax which

could be due to thickening of the bronchial walls that causes mild obstruction of the airways.4 It

is recognized that longstanding inflammation can lead to bronchiectasy, which is usually

irreversible in this stage of the disease.1,4 Other complications that may occur are COPD

(chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), pulmonary hypertension, tracheobronchomalacia, and

mycoplasmal or other bacterial infections.4 In some way, the canine lower airways appear to

have extensive interconnections between alveoli and bronchioles, which permits collateral

ventilation.1 This means that the disease must be highly developed before the clinical signs and

COPD are evidenced.1

In case the patient is systemically affected, it is important to evaluate the blood parameters

by performing a CBC (complete blood count), a chemistry panel and possibly a urinalysis.1,4 On

Maximus a blood work was performed since he was a middle-aged dog that had no recent

references of testing available. The results were mostly unremarkable, evincing a very mild

hyperglobulinemia with elevated bicarbonate. The hyperglobulinemia was explained by the

chronic inflammation, while the elevation in bicarbonate could be due metabolic alkalosis

comparing to the slight decrease in chloride (107mEq/L). No obvious signs of allergy or parasitic

infection were detected, however, the latter could had been confirmed by performing fecal

examination, even though he was dewormed.

Whereas pulmonary function testing is common to perform in humans due to high specificity

for bronchitis, in veterinary medicine it has added difficulties to execute on a routinely basis

concerning the inaccessible equipment.3 These testing consist of analyzing arterial blood gas,

endtidal CO2, or pulse oximetry to evaluate gas exchange and breathing effort.3 More practical

tests, consist of collecting blood for arterial blood gas analysis which can detect hypoxemia or

increased alveolar-arterial gradient to confirm pulmonary dysfunction.3 Additionally, a 6-minute

walk test is based on measuring the distance a dog is capable to walk within 6 minutes.3 If the

result is less than 400 meter, the patient is considered to have respiratory disease.3 One study

10

pharmacological stimulation, could help characterizing pulmonary function and ventilatory

deficits in dogs with restrictive pulmonary disease, such as obesity.6 However, thoracic

radiography may also be supportive. To accomplish this appropriately, at least three views

should be obtained: left lateral, right lateral and ventrodorsal. This is applicable not only to

identify the lung affected but also to detect possible masses, cardiac disease or foreign bodies,

which is impracticable without a tridimensional view. Radiographs usually reveal bronchial or

interstitial infiltrates, even though they might be subtle.2 Controversially, a study showed that

dogs with bronchitis shared many radiographic findings with healthy dogs, linking interstitial

bronchial calcification or dilatation and interstitial infiltrates.2 The major divergence found was

thickening of the airway walls, revealing that radiography has low sensitivity (~50-65%) and

might as well be unreliable to detect pulmonary dysfunction, particularly in very obese

patients.2,4 Maximus’ radiographs were consistent with mild bronchial pattern and bronchial wall

mineralization which is indicative of chronic bronchitis. No signs of pneumonia were seen,

however, two accidental findings were evidenced: 1) a presumptive herniated and mineralized

intervertebral disc at T13-L1, as well as a 2) mild degenerative joint disease of right

scapulohumeral joint, both appeared to be asymptomatic, and were for this reason, no further

investigated (Appendix II, Fig. 6).

CT scanning seems to be promising since the airway detail is superior comparing to

radiographs, but it is expensive and requires general anesthesia and is so, not commonly

employed.3 Beside this, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is convenient to obtain samples for

cytology and microbiology.3 Cytology typically discloses neutrophilic or mixed inflammation,

mucus, hyperplastic bronchial epithelial cells, ciliated cells, macrophages and goblet cells.1,4

The presence of degenerative neutrophils may indicate bacterial infection, while eosinophilia is

suggestive of allergic component or parasitic disease.1,4 Isolation of Bordetella bronchiseptica, Streptococcus spp., Pasteurella spp., Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas spp., Klebsiella spp., or Mycoplasma spp. are strongly recommended and even aerobic bacteria can be isolated, since the respiratory tract is not totally sterile.1,2 A significant growth and a positive bacterial infection

is considered when greater than 1.7 x 103 colony-forming units/mL is achieved in combination

with a suppurative inflammation on cytology.2 Bronchoscopy combined with BAL is the ideal and

preferred procedure to evaluate the severity of the disease and exclude other differentials.1,2,3,4

This technique has the potential to observe minutely within the deepest airways, and obtaining

this way, representative samples.1 Characteristically, the airways evidence excessive mucus,

irregular and thickened mucosa with hyperemia, fibrosis, epithelial hyperplasia, glandular

hypertrophy, and inflammatory infiltrates.1,2,3,4 According to one study, older dogs (>8 years),

seem to have more irregular bronchial mucosa, prominent mucosal vessels and bronchiectasis,

11

as a higher percentage of lymphocytes comparatively to middle-aged dogs (5-8 years).7

Patients that during this procedure experience bronchial collapse as regards to passive

expiration seem to have a worse prognosis.1,3

The treatment is generally managed symptomatically, starting by eliminating possible

environmental factors, such as tobacco, cleaning products, humidity and by replacing air filters,

as well as controlling obesity or anything that is recognized to have influence on the disease.3,4

However, obesity is the most significant factor and should be adequately managed, promoting

exercise according to the ability of the patient and by increasing it gradually.1,3,4 Due the

increased tracheal sensitivity for cough, it is recommended to use a harness instead of the

regular collars.1,3 As soon as bronchopulmonary infection is excluded, a treatment with

glucocorticoids should be initiated in order to reduce inflammation and secretion of mucus,

improving the cough.1,2 More specifically, prednisone (0.5 to 1 mg/kg) as oral medication is very

effective.2,3 It should be tapered as soon as improvement is seen (~10-14 days), reducing 25%

every 2 to 3 weeks until the lowest dose effective is achieved.2,3 According to a study, patients

that experience excessive side effects from glucocorticoids or those with coexisting medical

conditions, seem to respond positively to inhalation therapy with fluticasone proprionate (125 µg

BID).2,3 The medication should be inhaled approximately 6 to 8 times, however the ideal dosage

is uncertain because of undefined quantity that achieves the lungs.2,3 An adequate starting dose

is approximately 10 to 20 µg/kg twice daily.3 Controversially, endocrine effects evaluated by a

study, revealed cortisol suppression particularly by oral prednisolone and inhaled fluticasone,

considering inhaled budesonide a safer choice.5 Other medications that can contribute to the

treatment plan are bronchodilators, of which theophylline, a methylxanthine, is the most

commonly used. Theophylline has unproved and unspecific potential to decrease diaphragmatic

fatigue and increase mucociliary clearance, making this a preferred option.3,4 A long-acting form

of theophyline at a dose of 10 mg/kg BID or 15mg/kg SID, might also improve the expiratory

airflow and enclose synergic effects with glucocorticoids.3,4 However, most of the dogs with

chronic bronchitis don’t cover reversible bronchodilation which makes the use of this medication

controversial or unideal.1 Other bronchodilators used are aminophyline and oxtriphyline.4

Comparatively, sympathomimetics such as terbutaline or albuterol, do not achieve the same

efficiency and may cause anxiety and restlessness.3,4 Antibiotherapy is limited to patients with a

positive culture.3 In high suspicion of a non-confirmed bacterial infection, doxycycline or

azithromycin may be initiated since both have satisfying anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial

effects.3 On presentation, Maximus was on doxycycline and did not improve. Afterwards, the

results of cytology and culture confirmed the absence of an infectious cause. Other antibiotics

as fluorquinolones have elevated risk of bacterial resistance as well as theophylline toxicity, and

12

In association with the treatment, nebulization followed by coupage should be recommended to fluidize the secretions and to promote clearance of the airways.2 Chronic bronchitis is

generally an irreversible condition that is managed by reducing inflammation and ameliorating

quality of life, not only because the disease itself attends to be incurable, but also due to the

uncertain outcome.3 Concerning to this, before a therapeutic plan is stipulated, it is best to

initiate one medication at a time, in order to determine the ideal pharmacological combination

and adapting it over time, because relapse of the coughing may occur.3,4

References:

1- Kuehn N. F (2003) “Chronic Bronchitis in dogs” in King L.G Textbook of Respiratory Diseases in Cats and Dogs, Saunders Elsevier, 1st edition, 379-387.

2- Johnson L. R, Mckiernan B. C (2010) “Canine tracheobronchial disease” in Fuentes V.L, Johnson L.R, Dennis S Bsava Canine and Feline Cardiorespiratory Medicine, BSAVA British Small Animal Veterinary Association, 2nd edition, 274-279.

3- Rozanski E (2014) “Canine Chronic Bronchitis” in Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, 44, 107-116. 4- Nelson R.W, Couto C.G (2009) “Disorder of the Trachea and Bronchi” in Small Animal Internal Medicine, 4th edition, Mosby

Saunders, 285-291.

5- Melamies M, et al. (2012) “Endocrine effect of inhaled budosenide compared with inhaled fluticasone propionate and oral prednisolone in healthy Beagle dogs” in The Veterinary Journal, 194, 349-353.

6- Manens J, et al. (2011) “Effects of obesity on lung function and airway reactivity in healthy dogs” in The Veterinary Journal, 193, 217-221.

13

Clinical case Nr.3: Soft Tissue Surgery – Adrenalectomy

Characterization of patient and reason of appointment: Katie was a 7 to 9 year old, female spayed, 21 Kg, Australian Shepherd, that was presented to the UTVMC Soft Tissue

Surgery service for a right adrenalectomy.

Anamnesis: Katie was adopted one year ago, had vaccinations as well as deworming up to date, and was fed with a dry Premium quality diet. She had a history of controlled discoid lupus erythematosus, however, Katie's main problem was the recurrent UTI that she had been

experiencing every month, for 11 consecutive months. Ultrasound confirmed the diagnosis of

emphysematous cystitis as well as right adrenomegaly (0.90 cm). Amoxicillin was added to

enrofloxacin, which was extended to 4-6 weeks. Due to the slow hair growth and marked

lethargy, hypothyroidism was suspected which was confirmed later with a TSH/T4 level test.

Physical exam: The skin changes (alopecia, seborrhea, crustae and erythema) were related to the previous diagnosis of calcinosis cutis. No murmurs or crackles were ausculted and the rate was normal. Abdominal palpation revealed a mild hepatomegaly and the rectal temperature was

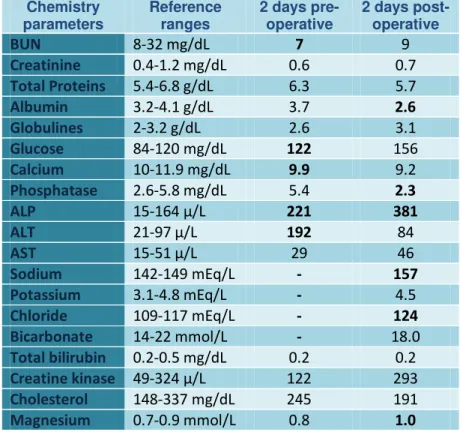

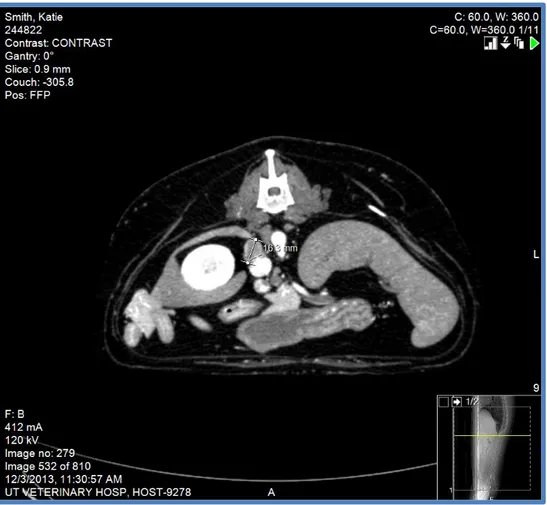

38.8ºC. Diagnostic tests: Crossmatch test- receptive to all blood donors. Chemistry panel - mild decrease in BUN, moderate elevation in ALP and ALT (Appendix III, table 5). CT scan -

confirmed increased size of right adrenal mass of 1.63 cm (Appendix III, Fig. 7). PCV/TS – 57%

/ 8.0 mg/L. On re-evaluation, an ultrasound revealed an increase in size of the right adrenal

gland with invasion of the vena cava. Beside this, thrombus formation in caudal vena cava with

mineralization and a mild hepatomegaly were also appreciated, while a skin biopsy returned as

calcinosis cutis. Katie was experiencing exacerbated lethargy, polyphagia as well as polyuria and polydipsia. An ACTH stimulation test was inconclusive, nonetheless, a LDDS (Low Dose

Dexamethasone Suppression) test, as well as a HDDS (High Dose Dexamethasone

Suppression) test made it possible to confirm the presence of adrenal-dependent Cushing's

disease. Pre-operative treatment: Prednisone 1 mg/kg PO SID, administered one day previous to surgery and received last dose on the morning of surgery. Fluid therapy with

lactated Ringer’s solution at 100 mL/h. Anesthesia: Pre-medication – Fentanyl 5 µg/kg IV and lidocaine 2mg/kg IV; Induction – Ketamine 5 mg/kg IV, midazolam 0.5 mg/kg IV, propofol 2

mg/kg IV; Maintenance – Propofol 2 mg/kg IV given twice, ephedrine sulfate 0.1 mg/kg after

induction due hypotension, dopamine 1 mL/h at CRI, ketamine 2 mg/kg IV, sevoflurane 2% with

oxygen, fentanyl-lidocaine at CRI; dexamethasone diluted at CRI during surgery; synthetic

colloid 120 mL IV and fluid bolus of isotonic solution 10 mg/kg during surgery; Antibiotic –

Cefazolin 20 mg/kg IV at anesthetic induction. Surgery: After trichotomy and antisepsis, Katie was placed in dorsal recumbency. The midline incision was made from the xyphoid to just

14

subcutaneous tissues were cut with Metzenbaum scissors and thebodywall was cut a with

curved Mayo scissor. The falciform fat was broken down digitally and tied off with 2-0

Monocryl®, and was then removed. A Balfour retractor was placed in the cranial abdomen and

the abdominal cavity was explored. After this, the mesoduodenum was retracted carefully,

without damaging the pancreas, to allow visualization of the right adrenal gland. During the

exploratory laparotomy, it was noticed that the right kidney's surface looked irregular. A red

rubber catheter (18 Fr) was cut in four pieces to create a Rumel tourniquet. The retroperitoneum

was bluntly dissected using curved hemostats for placement of the umbilical tape with the

Rumel tourniquets. The caudal torniquet was placed around the caudal vena cava and renal

vein (the left phrenicoabdominal vein was not included to allow blood flow). Cranial Rumel

tourniquet was placed over the vena cava cranial to the right adrenal gland. The tourniquets

were just placed but not actually tightened down. The right adrenal gland was dissected from

right kidney using curved hemostats and hemostasis was maintained with bipolar. The right

adrenal gland had a round egg shaped tumor with a stalk. Two malleable retractors were placed

to allow more visualization of the abdomen. A third malleable retractor was placed, as blunt

dissection of the fascia of the vena cava from the tumor continued. Medium hemoclips were

placed across the phrenicoabdominal vein and the vessel was transected with Metzenbaum

scissors. Fat was stripped next to the tumor using cotton tipped applications. A lymphatic

branch was transected in dissection. Dissection from vena cava continued carefully and

thrombus was manipulated out of the vena cava and into the phrenicoabdominal vein. Three

large hemoclips were placed across the stalk of the tumor. The tumor stalk (phrenicoabdominal

vein) was transected using curved Metzenbaum scissors. No hemorrhage was seen. Finally the

body wall was closed using 0 PDS® in a simple continuous pattern, 2-0 Monocryl® in

subcutaneous tissue in a simple continuous pattern and 3-0 in skin with a ford interlocking

suture. Post-operative complementary tests:PCV/TS – 45% / 5.1 mg/L. Blood Glucose – 137 mg/dL. Histopathology – confirmed adrenocortical carcinoma with vena cava and multifocal

vascular invasion. Complete blood count – moderate neutrophilia, monocytosis (Appendix III,

table 4). Chemistry panel – mild hypoalbuminemia, mild hyperglycemia, mild hypocalcemia, mild

hypophosphatemia, moderate elevation of ALP, mild hypernatremia and mild hyperchloremia

(Appendix III, table 5). Post-operative treatment: Katie recovered from surgery in the ICU, where she remained during the night having received a poly-ionic and isotonic solution

(Plasmalyte A®) at 54 mL/h IV, and fentanyl + lidocaine IV at CRI of 1.6-6.5 mL/h. The

temperature, pulse and respiratory rate were re-evaluated every 6 hours. PCV, TS and blood

pressure were repeated twice daily. Katie was also on Soloxine® 0.3 mg PO daily and

amoxicillin 400 mg every 8 hours. During surgery Katie received 1.1 mg of dexamethasone IV

15

prednisone on a dose of 10mg PO BID, and 50 mg of tramadol and 200 mg of gabapentin were

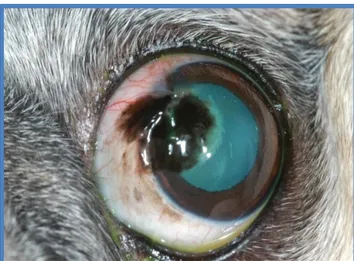

administered orally, every 8 hours. During physical examination, a corneal ulcer was noted on

the right eye so adequate treatment was provided. The following day, she was transferred to the

regular wards since her medical condition was not considered critical anymore. At this point,

blood work was repeated, as well as an ACTH stimulation test, in order to obtain a baseline of

cortisol levels posterior to surgery (even while on exogenous steroids). Previously to the ACTH

stimulation, cortisol levels were 31.5 ng/L and post stimulation, cortisol levels decreased to 29.6

ng/L (Appendix III, table 6). Katie stayed stable and was sent home the next day with 50 mg of

tramadol, 100 mg of gabapentin, 20 mg of prednisone, 0.2 mg of Soloxine®. Prognosis: Fair regarding metastatic disease.

Discussion: Adrenocortical tumors (AT) occur in approximately 15 to 20% of dogs with hyperadrenocorticism, which corresponds to less than 1% of all canine neoplasms.4,5 The most

commonly affected patients are middle-aged to older dogs without evident sex predilection,

although, a slight greater risk in females has been reported.3 The adrenal tumors that are most

frequently seen are mainly adenoma and carcinoma that account with equal incidence.4

Concerning to localization, the medullary tumors secrete catecholamines that tend to origin

severe hypertension, the adrenocortical secrete excessive glucocorticoids causing Cushing’s

syndrome. Nevertheless, in carcinomas, multiple hormone secretions, such as glucocorticoids,

mineralocorticoids and sex hormones, have been reported, even if very unusual.3,5 One study

reported that, approximately 50% of the dogs with adrenocortical tumors causing

hyperadrenocortisim (ATH), weigh more than 20 kg.4

Histopathology seems to be the only modality to distinguish the type of AT, however, it is

acknowledged that carcinomas tend to be larger in size, are more likely to invade other

structures and metastasize specially to liver, spleen, lungs and tricuspid valve.4,5 Thus, imaging

modalities likewise to abdominal ultrasound, radiography and CT scan might support

differentiation of ATs, and according to presence or absence of metastatic disease, the

malignancy might be predicted as well.3 Even though metastatic lesions represent no more than

26.7% of the canine adrenal tumors, it should always be considered.5 The exact pathogenesis

remains uncertain, but in humans, it is recognized that abnormal biosynthetic pathways result in

lack of adrenal steroidogenic enzymes (21β-hydroxilase and 11β-hydroxilase), leading to

hypersecretion of precursor steroids.3 Another factor for increased steroid precursors might be

invasion of the adrenal cortex by malignant cells that could possibly interfere with the normal

enzymatic trial.3 Some steroid intermediates, such as progestins, might disconnect cortisol from

its serum-binding protein, achieving increased concentrations of cortisol in the active form,

which will enhance the typical hyperadrenocorticism signs.3 Those progestins might as well act

16

cortisol is produced by the adrenal tumor which causes pituitary suppression, with consequent

decrease in ACTH concentration and atrophy of contralateral adrenal gland.4

The characteristic clinical signs consist of polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, panting,

pendulous abdomen, skin atrophy, symmetric alopecia, bruising, muscle atrophy and lethargy.3

Diagnostic wise, increased serum alkaline phosphatase activity, hypercholesterolemia and

hyposthenuric urine might suggest hyperadrenocorticism, making clinical pathology as well as

urianalysis with culture of enormous relevance.4 Approximately 85% of dogs with

hyperadrenocorticism have ALP activity higher than 150 IU/L.4

Katie’s recurrent UTI’s were explained by the endogenous glucocorticoid-induced immunosuppression, as well as polydipsia, that turned not only the urine diluted, but made Katie

more predisposed to infection, causing interference with the identification of the infection.4

However, the definitive diagnosis can only be made by combining abdominal ultrasound with

respective measurement of the adrenal glands and a LDDS/ HDDS/ Endogenous ACTH tests.4

Radiographs are not efficient to identify adrenal glands or adrenal tumors, but might identify

calcification, hepatomegaly, distension of the urinary bladder and create suspicion of Cushing’s

disease.3,4 Approximately 50% of ATH are calcified, which is equally distributed between

adenoma and carcinoma.4 On ultrasound, adrenomegaly is considered when the maximum

width is greater than 0.8 cm, and adrenal atrophy at maximum width less than 0.3 cm.4

Nevertheless, AT can occur bilaterally and even if uncommon, it should not be confused with

bilateral macronodular hyperplasia, which consist of multiple nodules of different sizes within the

adrenal cortex and is mainly thought to be a variant of pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism

(PDH).4 CT or MRI should be considered to evaluate size and extension of the tumor prior to

adrenalectomy.2,4

Therapeutically, ATH’s treatment of choice is adrenalectomy, as long as no severe

metastatic disease is appreciated.1 To minimize the high risks associated post-operatively,

especially during the following 72 hours, it is vital to manage a preoperatively plan to guarantee

the patient is stabilized. It is recognized that the larger the size of the tumor, the greater the

complications which makes the diagnostic testing previous to surgery crucial as well.4 Despite

other underlying diseases, Katie was considered a good candidate for surgery, given that the

right adrenal mass presented a size of approximately 1.63 cm. Many times those tumors can

extend from 6 to 8 cm of diameter which escalates the surgery complexity.4

The removal of the adrenal gland leads to abrupt decrease of glucocorticoids and to

signalment such as depression, inappetence, lethargy and collapse.1,2 Along mineralocorticoid

suppression, other electrolyte and acidbase imbalance may be induced, involving

hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, acidosis and azotemia.1 As prevention, essentially in surgery,

17

Katie initiated the supplementation prior and during surgery regarding the fact that some

animals seem to have a delayed response to exogenous steroids.1 The healing process of the

suture line might be slower due catabolism and often protein depletion, requiring special care.1,2

The most worrying complications are hypertension with consequent cardiovascular disease and

pulmonary thromboembolism.1,2,4 To anticipate it, measurement of blood pressure is necessary

and a low-dose of aspirin can be provided along suspected hypercoabulability.1,4 For patients

that experience respiratory distress, oxygen as well as anticoagulant and thrombolytic agents

should be considered.1 Regarding to this Katie was maintained in cage rest, constant

respiratory watch and her position was changed every 4 hours, post-operatively.

The surgical approach can be performed by a ventral midline, as Katie, or paracostal

incision.1,2 The ventral midline incision allowed to execute a complete exploration of the

abdomen to detect possible metastasis and could had been a more useful choice in cases with

bilateral adrenalectomy.1,2 The second surgical approach gives better access to the adrenal

gland, although just unilaterally and does not cover the benefit to able a complete evaluation of

the abdomen.1,2 However, on ventral midline approach it is possible to extend the incision

paracostally on the side of the affected adrenal gland in case additional exposure is necessary.1

For Katie this was not required since the use of a Balfour retractor and three self-retaining

malleable retractors were efficient to obtain accurate visualization of the operating field.

Moistened sponges could had been used to cover the retractors, minimizing trauma to

surrounding organs and absorbing possible bleeding, although, its adequate removal from the

abdominal cavity must be certified.1 After dissection, an exploratory laparotomy was performed,

revealing irregular kidney surface of the right kidney and very mild hepatomegaly. Renal

damage could be consequence of chronic and recurrent UTI while hepatomegaly is explained

by hyperadrenocorticism. For temporary occlusion of the vena cava, a Rumel tourniquet was

created cutting a red rubber catheter and by using two parts of it for introduction of the umbilical

tape. In Katie, a double ligation was required due to invasion of the tumor within the vena

cava.1,2 The creation of a temporary occlusion of the major vein was crucial and critical at the

same time, since it avoids severe blood loss but also compromises blood supply, encourages

clotting and increases the risk of potential thromboembolism. However, the methodology with

these materials creates a better control on clamping since it tightens and unfastens easily, and

causes as well, a milder trauma to the vessels. The methods of hemostasis were achieved with

bipolar electrocautery for smaller vessels and hemoclips for phrenicoabdominal vein and tumor

stalk. Hand ligatures are difficult to perform around this area because vessels are small and

space area is limited.1,2 The hemoclips were used in larger vessels due to the rich blood supply

to the adrenal gland, as well as to assist with the removal of the tumor, for the reason that it

18

cavity. Adequate dissection can be challenging since the adrenal capsule must remain intact.1,2

In aggressive invasions, vascular surgery might be required.1,2 Around 25% of adrenal

neoplasms seem to invade the vena cava, phrenicoabdominal veins or renal veins,

nevertheless, it appears more frequently in pheochromocytomas.1

Regarding the delayed healing process, those patients require a tough suture with adequate

tensile strength.1,2 For Katie, polydioxanone was used, a slowly absorbable suture for the body

wall and Monocryl®, absorbable as well, for subcutaneous tissue and skin.

Postoperatively, the patient requires monitoring for dehydration, electrolyte imbalance,

thromboembolism, hemorrhage, infection and hypoadrenocortical collapse.1 An unilateral

adrenalectomy causes temporary adrenal insufficiency which means the patient requires

temporary glucocorticoid supplementation until the remaining adrenal gland responds, produces

sufficient endogenous steroids and homeostasis is achieved.1,2,4 This occurs progressively,

particularly because the function of the contralateral adrenal gland was suppressed by the AT.1

The main difficulty is prognosticating the exact moment when homeostasis is achieved to

perform ACTH stimulation test and decrease glucocorticoid supplementation. Along bilateral

adrenalectomy, a life-long glucocorticoid and/or mineralocorticoid replacement is imperative.1

Katie’s treatment plan consisted of initiating dexamethasone post and operatively, and by changing it for prednisolone the following day. This dose was continued for one week and then

tapered down gradually in 10 weeks. However, the medication adjustment could had been

made the same day, following surgery.1

According to one study, dogs with an adrenal gland tumor with maximum width of 5 cm, that

reported metastatic disease or vasculature invasion had poorer prognosis.6 Metastatic disease

seemed to be more frequent in dogs with adenocarcinoma and vein thrombosis.6 The median

survival time was 492 days as reported by a different study, which makes the prognosis for

Katie fair.7

References:

1- Fossum T.W (2012) “Adrenalectomy” in Small Animal Surgery, 4th edition, Mosby Elsevier, 633-646.

2- Adin C. A, Nelson R. W (2011) “Adrenal Glands”in Tobias K, Johnston S. Veterinary surgery Small Animal, 1st edition, Elsevier Saunders, 2033-2041.

3- Hill K. (2013) “Primary Functioning Adrenal Tumors Producing Signs Similar to Hyperadrenocorticism Including Atypical Syndromes in Dogs” in Rand J, Behrend E, Gunn-Moore D, Campbell-Ward M. Clinical Endocrinology of Companion Animals, 1st edition, Wiley-Blackwell, 65-69.

4- Nelson R.W, Couto C.G (2009) “Disorders of the Adrenal Gland” in Small Animal Internal Medicine, 4th edition, Mosby Saunders, 810-846.

5- Frankot J. L, Behrend E. N, Sebestyen P, Powers B. E (2012) “Adrenocortical Carcinoma in a Dog with Incomplete Excision Managed Long-term with Metastasectomy Alone” in Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 48, 417-423. 6- Massari F, Nicoli S, Romanelli G, Buracco P, Zini E (2011) “Adrenalectomy in dogs with adrenal gland tumors: 52 cases

(2002–2008)” in Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 239, 216-221.