ACUTE RHEUMATIC

FEVER IN THE SOUTHEASTERN

METROPOLITAN

AREA OF SANTIAGO,

CHILE,

19764981’

Ximena Berries,’ Emilio de1 Campo,3 Carmen Wilson,3 JosC Blhsquez,3

Alejandro Morales,2 and Francisco Quesney2

A study of 230 acute rheumaticfever cases was conducted at Santiago’s Sdtero de1 Rio Hospital in order to help enlarge the fund of information available on rheumatic fever in Chile. This article reports the results of that study.

Introduction

By the beginning of the 197Os, a number of Chilean authors (1,2,3) had provided informa- tion about rheumatic fever in its various forms. The general picture provided by that information was as follows:

The disease prompted a total of 40,000 med- ical consultations per year (4.4 per 1,000 in- habitants), generated 5,000 hospital admissions per year (54.5 per 100,000 inhabitants), and gave rise to 160 disability pensions per year (10.9 per 100,000 eligible persons). It also caused 790 deaths, giving Chile a mortality of 8.4 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants-the highest recorded mortality from this cause in Latin America.

The disease affected mainly younger age groups; 54% of the hospitahzed patients were under 25 years of age, and the average age of those dying from this cause was 43 years.

Some 40% of the hospitalized fatal cases oc- curred in Santiago. In all, the risk of hospitali- zation and death from this cause was 29% higher among women than among men. A definite as-

‘Based on a study financed in part by the American Heart Association, Grant No. 80-981, and by projects 26/76 and 63/78 of the Research Department of the Catholic University of Chile. Also appearing in Spanish in the Boletin de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana, 97(Z): 11% 124, 1984.

‘School of Medicine, Catholic University, Santiago, Chile.

‘Southeastern Health District, S6tero de1 Rio Hospital, Santiago, Chile.

sociation was found between occurrence of the disease and the seasons of the year, but no clear link between disease incidence and geographic areas was detected.

As of the beginning of the 1970s overall mor- tality was considerably lower than it had been in the 1930s and 1940s when the average re- corded mortality was 12.3 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. However, rates of hospital admis- sion for this cause were about the same in the two periods.

Regarding the streptococcal infection pre- sumed to give rise to the disease, it was estab- lished (2) that the rate of pharyngeal carriers was 19% among children two to 15 years old, and that the monthly incidence of clinical infection was 3%. However, when this infection was inves- tigated by determining serum antibody titers in a second control visit,” an incidence of recent infec- tion on the order of 15% was detected (2). Within this context, it should be mentioned that four-fifths of those manifesting symptoms had not consulted a physician, and of those who did so only half had received proper treatment.

0 l l

The study reported here was undertaken for the purpose of learning more about the prevailing rheumatic fever situation in Chile. It was designed as an exploratory study directed at defining the

4An anti-streptolysin 0 titer of 200 or more was considered positive.

390 PAHOBULLETIN l vol. 18, no. 4, 1984

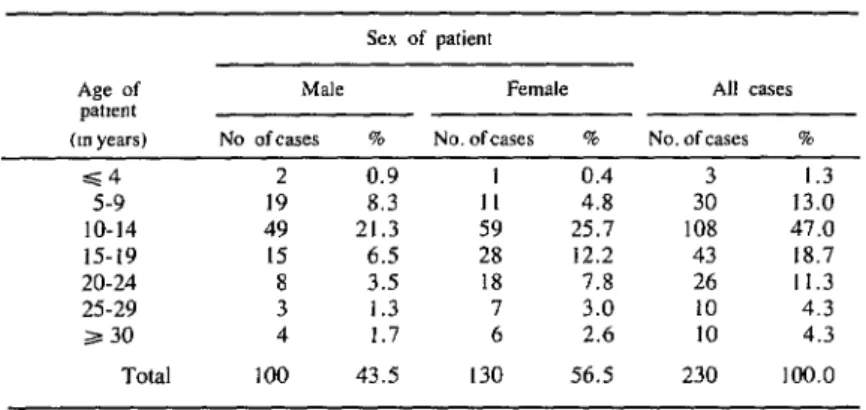

Table 1. The distribution of the 230 acute rheumatic fever cases studied according to the patient’s age group and sex.

epidemiologic characteristics of the disease within Santiago’s Southeastern Metropolitan Health Ser- vice Area during the period 1976- 1981.

Materials and Methods

The study population included all patients hospitalized during the years 1976-1981 in the medical and pediatric departments of the Sdtero de1 Rio Hospital who had been clinically diag- nosed, using Jones’ modified criteria (4) for gui- dance, as having acute rheumatic fever. This group consisted of 217 patients who had suffered 230 episodes of acute rheumatic fever during the study period. (The data to be presented refer to these specific episodes rather than to indi- vidual patients.)

All of the patients underwent a standardized examination procedure consisting of (a) procure- ment of a detailed medical history by a physi- cian; (b) study of the patient’s socioeconomic status and of home contacts by a field nurse; (c) general laboratory tests including a hemogram, sedimentation (ESR), and specific tests such as an electrocardiogram (ECG), a chest X-ray, a pharyngeal smear culture, and tests for determin- ing levels of anti-streptolysin 0 (ASO), anti- DNase-B (ADB), and anti-streptozyme (ASTZ); (d) development of an ad hoc treatment plan; and (e) collection of data on the clinical and laboratory evolution of the episode.

The criteria used to identify major and minor

Jones manifestations were in accord with the recommendations of the American Heart Associ- ation (41, the World Health Organization (5), and Markowitz (6).

Isolation and identification of beta-hemolytic streptococcus (BHS) was accomplished by means of the technique recommended by Facklam (7). Streptococcal antibody titers were determined using the Rantz and Randall tech- nique for AS0 (S), the technique recommended by Wampole Laboratories, USA, for ADB (9), and the technique recommended by Bisno and Ofek for STZ (IO). An AS0 titer of 333 or more Todd units, an ADB titer of 480 or more ADB units, an ASTZ titer of 200 or more STZ units, and any positive response involving a change of more than two tube-dilutions in consecutive samples were all regarded as significant.

Results

General Characteristics of the Study Population

Tables 1 through 5 show basic data (patient age, sex, residence area, and socioeconomic status; and year and season of occurrence) about the 230 acute rheumatic fever episodes involving hospitalization during the study period. The socioeconomic classification of the patients (see Table 5) was based on the observable situation, the percentage of family-group members under

Sex of patient

Age of Male Female All cases

pE3tWlt

(Ill years) No ofcases % No. ofcases % No. of cases %

=S4 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24 25-29 2 30

Total

2 0.9 1 0.4 3 1.3

19 8.3 II 4.8 30 13.0

49 21.3 59 25.7 108 47.0

15 6.5 28 12.2 43 18.7

8 3.5 18 7.8 26 Il.3

3 1.3 7 3.0 10 4.3

4 1.7 6 2.4 10 4.3

Berrios et al. 0 ACUTE RHEUMATIC FEVER IN CHILE 391

n

Table 2. The years of occurrence of the 230 acute rheumatic fever cases studied, showing the case rate for

residents of southeastern Santiago served by the SBtero del Rio Hospital.

YeFiI

1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 Total

No. of Rate per 100.000

cases inhabitants

54 9.15

72 12.20

29 4.91

24 4.06

22 3.73

29 4.91

230 650peryear

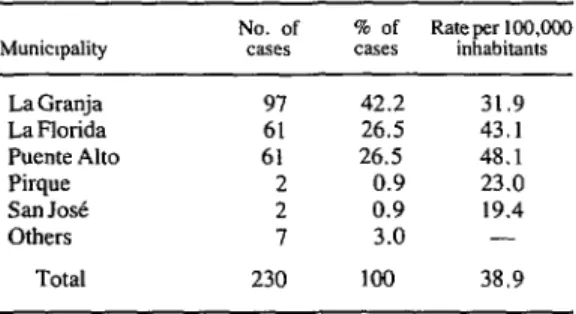

Table 3. Distribution of the 230 study cases among the municipalities of the Southeastern Santiago Health Area

served by the S6tero del Rio Hospital.

Municxpality

La Granja La Florida Puente Alto Pirque salt Jo3 Others

Total

No. of % of Rate per 100,000 cases cases inhabitants

97 42.2 31.9

61 26.5 43.1

61 26.5 48.1

2 0.9 23.0

2 0.9 19.4

7 3.0 -

230 100 38.9

Table 4. Seasonal distribution of the 230 study cases.

SWOll No. %

Summer 36 15.7

Fall 67 29.1

Winter 65 28.3

Spring 62 27.0

Total 230 100

Table 5. Distribution of the 230 study cases by the patient’s socioeconomic status.

Patient’s

socmeconomic status

Class I Class II Class III Class IV No data Total

C&SEX

NO. %

53 23.0

62 27.0

75 32.6

19 8.3

21 9.1

230 100

15 years of age, and the degree of crowding in the home (the number of residents per bedroom and per bed). Each episode involving the same patient was considered separately.

Overall, the study population was found to have a slight predominance of women and a marked predominance of people in relatively young age groups. The number of admissions tended to decline during the study period. Most of the cases came from the more urban com- munities in the study area (the highest rate occur- ring in Puente Alto); and the rate of illness epi- sodes was found to be comparable in the fall, winter, and spring, and to decline significantly in the summer. Regarding the subjects’ socio- economic status, most were found to fall into the next to the lowest category (III); the most commonly determined levels of room and bed occupancy were in the ranges of 2.1-4.0 people per bedroom and 1.1-2.0 people per bed. No clear associations were found between any of these variables.

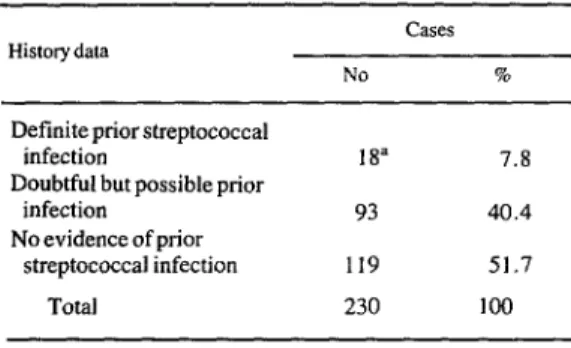

Medical Histories

Table 6 shows the number of cases studied that had a definite or positive prior history of streptococcal infection. The diagnosis was re- garded as definite if the patient had experienced scarlet fever or odynophagia accompanied by fever. Of the 18 patients with definite case his- tories of previous streptococcal infection, 14 had consulted a physician and 10 of these had re- ceived treatment appropriate for eliminating the infection (11).

392 PAHO BULLETIN . vol. 18, no. 4, 1984

Table 6. Distribution of the 230 study cases according to whether the patient’s history indicated that the case

in question involved previous streptococcal infection.

History data

Definite prior streptococcal infection

Doubtful but possible prior infection

No evidence of prior streptococcal infection

Total

CZWS

NO 90

18” 7.8

93 40.4

119 51.7

230 100

‘Includes one case of scarlet fever and 17 cases of febrile odynophagia.

Table 7. Distribution of the 230 study cases according to whether the patient’s history indicated one or more

previous episodes of acute rheumatic fever.

History data CZiSfX.

NO. 9%

Definite previous episode(s): 48 20.9

I previous episode 32 13.9

Zprevious episodes 5 2.2

3 previous episodes 7 3.0

4 or more previous episodes 4 1.7

Doubtful previousepisode 6 2.6

No previous episode 176 76.5

Total 230 loo

30% of the patients were hospitalized within seven days of the appearance of symptoms, 43% between seven and 2 1 days after the appearance of symptoms, and the remaining 27% over 28 days after the appearance of symptoms.

Table 8. Prophylaxis provided during previous episodes in the 48 instances where the patient’s history indicated

that one or more previous episodes occurred.

Prophylaxis provided Ci3XS

NO %

Regularprophylaxls (penicillin)a Irregular prophylaxis

(penicillin)b Sulfa drug prophylaxiC No prophylaxis

Total

6 12.5

29 60.4

I 2.0

12 25.0

48 100

“Prophylaxis with benzathine penicillin at regular 28-day intervals.

bProphylaxls with benzathine penicillin that was deemed irregular because the patient came one or more days late or missed clinic appointments altogether.

‘Prophylaxis with daily doses of sulfadiazine.

in four cases any prophylactic treatment that would have been indicated in accordance with Health Ministry standards (12) would have been completed before the latest attack occurred.

Data on prior prophylaxis indicated by patient histories are shown in Table 8. It is noteworthy that six patients had their present illness episode despite receiving regular prophylactic treatment up to the month preceding that attack; four of these patients had cases of chorea and two had rheumatic carditis.

Regarding the interval between the appear- ance of symptoms and hospitalization, some

Clinical and Laboratory Findings

Berries et al. . ACUTE RHEUMATIC FEVER IN CHILE 393

Table 9. Numbers of the 230 study cases exhibiting major Jones manifestations, minor Jones manifestations, and

clinical or laboratory evidence of streptococcal infection.

Cases

NO. %

Cases with thefollowing major Jones manifestations:

Carditis Polyarthritis Chorea

Erythema marginatum Subcutaneous nodules

Cases with thefollowing minor Jones manifestattons:

Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate

Fever Polyarthralgia Prolonged PR interval Leukocytosis

History of acute rheumatic fever Presence of rheumatic

heart disease

Cases with clinical or laboratory evidence of streptococcal infection:

Clinicalevidence Bacteriologic evidence Serologic evidencea

lOU230 44.3

1621230 70.4

351230 15.2

31230 1.3

9/230 3.9

2011228 88.2

1601230 69.6

1591230 69.1

491217 22.6

841228 36.8

481230 20.9

451230 19.6

11230 0.4

161218 7.3

2151217 99.0

‘Positive serologic evidence of streptococcal infection was considered to be elevation or a significant change in the titers obtained in response to at least one of the following tests: anti-streptolysin O(AS0). antt-DNase B (ADB), and anti-streptozyme (ASTZ).

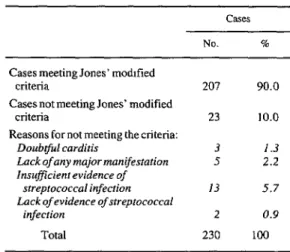

Table 10. Study cases meeting or failing to meet Jones’ modified criteria, together with reasons

why 23 cases did not meet these criteria.

Cases

NO. %

Cases meeting Jones’ modttied

criteria 207 90.0

Cases not meeting Jones’ modified

criteria 23 10.0

Reasons for not meeting thecriteria:

Doubtful carditis 3 1.3

Luck of any major manifestation 5 2.2

Insufficient evidence of

streptococcal infection 13 5.7

Lack of evidence of streptococcal

infection 2 0.9

Total 230 100

Discussion and Conclusions

The distribution by age and sex of the study subjects agrees fairly well with that indicated in classical descriptions (13, 14). The significant decline observed in the annual rate of hospitali- zation for acute rheumatic fever is consistent with Ministry of Health data for the rest of the Santiago Metropolitan Region (15).

The authors have no explanation to offer for the differences observed between the rate of ad- mission of patients from Puente Alto and the rate of admission of patients from other com- munities .

It is considered noteworthy that no significant seasonal variations were observed except for the sharp decline of cases in the summer.

In the absence of information about the socio- economic status of the general population in the region from which the study subjects came, no meaningful epidemiologic conclusions about the study subjects’ socioeconomic status can be drawn.

So far as the patients’ medical histories are concerned, few of these provided firm evidence of prior streptococcal infection. However, this is not altogether surprising in view of the strin- gency of the criteria applied (prior scarlet fever or odynophagia accompanied by fever). This stringency seems justified, especially since the prior history data were generally provided by a member of the patient’s family-a circumstance that led Jones to accept only a prior history of scarlet fever as definite evidence of previous streptococcal infection (4).

Overall, the number of patients found to have a history of definite or possible prior episodes of acute rheumatic fever (54) agrees fairly well with the number deemed to have had a confirmed recurrence on the basis of other evidence (57). This therefore appears to be a more reliable datum than that related to prior streptococcal infections.

394 PAHO BULLETIN l vol. 18, no. 4, 1984

rules, when the later attack occurred they would have been unprotected.

In addition, there were many cases in which the indicated prophylaxis was not properly com- pleted, and other cases in which it was properly carried out but failed. For one reason or another, prophylaxis failed in 36 of the recurrent cases. In most of these cases, the failure may be explained partly by the fact that no prophylactic control program concerned with overseeing pro- phylaxis was operating in the area at the time prophylaxis was prescribed. Also, in four out of six instances of “true’ ’ failure of a prophylac- tic regimen5 the patient had chorea, a circum- stance that is not surprising (16).

The most frequent major Jones manifestation observed was polyarthritis (in 70.4% of the cases), followed by carditis (44.3%). There was also a high incidence of chorea (15.2%). The most frequent minor Jones manifestation was an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Among the other minor manifestations, the low percent- age of cases with fever (69.6%) seems notewor- thy; and even if all cases with chorea are elimi- nated, the percentage of cases with fever still remains relatively low (at 82%). No association was found between cases without fever and pre- hospitalization latency of the illness, a develop- ment that could otherwise have offered an expla- nation for the lack of fever.

Evidence of streptococcal infection, as a sup- plemental finding needed for compliance with the modified Jones criteria (4), was based essen- tially on serologic findings. These findings were 99% positive in 217 cases where at least one of the three tests employed showed a response accepted as evidence of streptococcal infection.

The bacteriologic evidence obtained was very sparse. There are three possible explanations for this: the inherent difficulty of the technique used; pre-hospitalization latency (especially since 70% of the subjects were admitted a week or more after the appearance of symptoms); and a possibly indiscriminate use of antibiotics during the latency period.

Clinical evidence of prior streptococcal infec- tion, as accepted by Jones, was obtained in only one case-from a patient with a history of scarlet fever. The other 17 cases (where the patient had a history of febrile odynophagia) did not provide sufficient clinical evidence of prior streptococcal infection to meet the Jones criteria (see Table 6).

In sum, the modified Jones criteria were met in 207 (90%) of the 230 cases studied. The major element lacking in most cases where the criteria were not met (see Table 10) was inadequate information about streptococcal infection, be- cause in 13 cases a complete set of serologic tests was not available or no pharyngeal smear had been taken.

Regarding the age of patients with recurrent episodes, 23 of the 57 cases involving recurrent episodes occurred among patients under 15 years of age and 34 occurred among older patients. This means that 16.3% of the 141 cases in pa- tients under 15 were recurrent cases and 38.2% of the 89 cases in patients 15 years of age or older were recurrent cases. Our data, which in- dicate a significant association between the re- currences and cases of carditis (p<O.Ol), agree with published data (6, 13, 14). Similarly, our data relating age to the frequency of recurrences agree with published data (6. 13, 14).

‘Patients undergoing prophylaxis are required to attend a special prophylactic clinic every 28 days, where they receive

Some patients carry out this procedure very rigorously.

an injection of benzathine penicillin G. This procedure lasts

If despite this rigor they relapse, these relapses are consid-

for a long time (anywhere from five years to life). Punctuality

ered true failures (In our case this happened with six pa-

in keeping the appointments is essential, since prophylacti-

tients. The other failures occurred in patients whose prophv-

tally adequate serum levels of the drug last about 28 days

laxis was irregular, largely due to lack of appropriate moni- toring and supervision.

Berrt’os et al. 0 ACUTE RHEUMATIC FEVER IN CHILE 395

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank the members of the streptococcal team of the Catholic University Medical School’s Public Health Unit (Beatriz Guz- m&in, Cecilia Rodriguez, Ingrid Riedel, and Ver&rica Salgado) for their technical assistance; and to thank Luz Maria Ulloa for her secretarial assistance. We are also very grateful to Rosita Bustos of the Public Health Institute of Chile for grouping some of the BHS strains isolated, and to Dr. A. L. Bisno of the University of Tennessee College of Medicine for his cooperation and assistance in the performance of this study.

SUMMARY

To help enlarge the fund of information available on rheumatic fever in Chile, 230 cases of acute rheu- matic fever were investigated. All of these cases afflicted patients who were admitted to the Sdtero de1 Rio Hospital serving Santiago’s Southeastern Metro- politan Health Service Area during the period 1976-

1981.

Most of the patients were admitted during the initial years of the study, suggesting a marked decline in acute rheumatic fever cases over time. There was also a slight predominance of female over male patients. No significant seasonal variations were observed ex- cept for a marked drop in admissions during the sum- mer months.

Very few of the patients had any definite previous diagnosis of streptococcal infection, although roughly 20% were found to have previously experienced acute

rheumatic fever. In general, few of these earlier cases had received adequate prophylactic treatment; but there were also a number of cases where adequate prophylaxis (based on Health Ministry standards) ap- peared to have failed to prevent recurrence of the disease.

Many of the patients were admitted to the hospital over a week after their symptoms had appeared. A relatively high percentage of the study patients had chorea and a relatively low percentage had fever at the time of admission. However, no association was found between pre-admission latency of the illness and lack of fever. Overall, 90% of the cases studied met the modified Jones criteria for diagnosis of rheumatic fever. Most of those that failed to meet these criteria did so for lack of sufficient evidence of streptococcal infection.

REFERENCES

(1) Medina, E., and A. M. Kaempffer. Epidemio- logia de la enfermedad reumatica en Chile. Rev Med Chil98546, 1970.

(2) Medina, E., and A. M. Kaempffer. Elementus de salud priblica. Andres Bello, Santiago, 1979.

(3) Guash, J., and B. Vaisman. Fiebre reumdtica. Andres Bello, Santiago, 1979.

(4) American Heart Association. Jones Criteria (Revised) for Guidance in the Diagnosis of Rheumatic Fever. New York, 1967.

(5) World Health Organization. Prevention

of

Rheumatic Fever. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 342. Geneva, 1966.(6) Markowitz, M., and L. Gordis. Rheumatic Fever. Saunders, Philadelphia, 1972.

(7) Facklam, R. R. isolation and Identification of Streptococci. Center for Disease Control, U.S. Public Health Service, Washington, D.C., 1976.

(8) Rantz, L. A., and E. Randall. A modification of technic for determination of antistreptolysin titer. Proc Sot Exp Biol Med 59:22, 1945.

(9) Wampole Laboratories, Division of Carter- Wallace, USA. Streptonase-B: Determination of Antideoqribonuclease-B. Cranbury, New Jersey,

1981.

396 PAHO BULLETlN . vol. 18, no. 4, 1984

nosis of streptococcal infection: Comparison of a rapid hemagglutination technique with conventional antibody tests. Am J Dis Child 127:676, 1974.

(11) Wannamaker, L. W., C. H. Rammelkamp, Jr., F. W. Denny, W. R. Brink, H. B. Houser, E. 0. Hahn, and J. H. Dingle. Prophylaxis of acute rheu- matic fever by treatment of preceding streptococcal infection with various amounts of depot penicillin. Am J Med 10:673, 1951.

(12) Ministerio de Salud, Departamento de Apoyo a 10s Programas. Normas de control de la jiebre reumcitica. Santiago, 1980.

(13) Mutioz, S. Fiebre reumdtica y enfermedad

reumdtica de1 corazbn. Fondo Editorial Comiin, Caracas, Venezuela, 1977.

(14) Stollemran, G. H. Rheumatic Fever and Streptococcal Infection. Grune and Stratton, New

York, 1975.

(15) Ministerio de Salud, Departamento de Plani- ficacion. Anuario de enfermedades de notificacidn obligatoria. Santiago, 1977-1981.