Contents lists available atScienceDirect

Acta Tropica

journal homepage:www.elsevier.com/locate/actatropica

Review

Atypical presentations of cutaneous leishmaniasis: A systematic review

Camilla Barros Meireles

a, Laís Chaves Maia

a, Gustavo Coelho Soares

a,

Ilara Parente Pinheiro Teodoro

b, Maria do Socorro Vieira Gadelha

a,

Cláudio Gleidiston Lima da Silva

a, Marcos Antonio Pereira de Lima

a,⁎aLaboratory of Microbiology and Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of Cariri, UFCA, Barbalha, Ceará, Brazil bCenter for Biological and Health Sciences, Regional University of Cariri, URCA, Crato, Brazil

A R T I C L E I N F O

Keywords:

Cutaneous leishmaniasis Atypical

Clinical presentation

A B S T R A C T

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL) is endemic in 88 countries, showing relevant prevalences. The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review on atypical lesions of CL around the world, addressing clinico-epidemiological, immunological and therapeutic aspects. A search of the literature was conducted via electronic databases Scopus and PubMed for articles published between 2010 and 2015. The search terms browsed were

“cutaneous leishmaniasis”,“atypical”and“unusual”. Based on the eligibility criteria, 34 out of 122 articles were included in thefinal sample. Atypical lesions may include the following forms: erythematous volcanic ulcer, lupoid, eczematous, erysipeloid, verrucous, dry, zosteriform, paronychial, sporotrichoid, chancriform and annular. In any cases, they seem to be another disease like subcutaneous and deep mycosis, cutaneous lymphoma, pseudolymphoma, basal and squamous cell carcinoma. The lesions have been reported in the face, cheeks, ears, nose, eyelid, limbs, trunk, buttocks, as well as in palmoplantar and genital regions; sometimes occurring in more than one area. The reason for clinical cutaneous leishmaniasis pleomorphism is unclear but immunosuppression seems to play an important role in some cases. There are no established guidelines for the treatment of atypical cutaneous leishmaniasis. However, pentavalent antimonials remain asfirst line treatment for all forms of leishmaniasis even for HIV-infected patients and atpical forms. Finally, to diagnose an atypical lesion properly, the focus has to be on the medical history and the origin of the patient, comparing them to the natural history of leishmaniasis and always reminding of possible atypical presentations, to then start searching for the best diagnostic method and treatment, reducing the misdiagnosis rate and, subsequently, controlling the disease progression. Thereby, contributing for breaking the transmission chain of the parasite, due to early correct diagnosis which, in turn, contributes to reduce the prevalence.

1. Introduction

Leishmaniasis collectively refers to various clinical syndromes caused by obligate intracellular protozoa of the genusLeishmania, that is transmitted by the sandfly (Ayatollahi et al., 2015; Karami et al., 2013). It is a vector-borne zoonosis, with dogs, rodents, wolves, and foxes as common reservoir hosts and humans as incidental hosts (Ayatollahi et al., 2015; da Silva et al., 2014). Approximately 1.5 million new cases are documented each year and more than 350 million people live in areas of active parasite transmission (Dassoni et al., 2013).

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is one of the four different forms of the disease and the most common form (Alhumidi, 2013); being a major public health problem in 88 countries with an endemic behavior (Dassoni et al., 2013; Oryan et al., 2013). The other three clinical

forms include: visceral leishmaniasis (or Kala-azar); mucocutaneous leishmaniasis; and diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis (DCL) (Shah et al., 2010; Talat et al., 2014). Diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis is relatively rare and usually associated with mucous membrane involvement (Dassoni et al., 2013).

In an endemic area, it is necessary for the physician to be aware that any atypical lesion, especially chronic form, should be investigated for cutaneous leishmaniasis (Ayatollahi et al., 2015). Be attentive to the clinical examination, investigate if the patient lives in endemic area or traveled to an endemic area can facilitate the diagnosis.

There have been reports of some atypical lesions of CL around the world. These lesions can mimic many other diseases and confound the physicians, which may delay the precise diagnosis, submitting the patients to unnecessary treatments, worsening the picture, and con-tributing to the transmission chain of the parasite. However, there is a

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.05.022

Received 27 March 2017; Received in revised form 14 May 2017; Accepted 14 May 2017

⁎Corresponding author at: Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of Cariri, Rua Divino Salvador, 284, Rosário, Barbalha, Ceará, 63180-000, Brazil. E-mail address:marcos.lima@ufca.edu.br(M.A.P. de Lima).

Acta Tropica 172 (2017) 240–254

Available online 17 May 2017

0001-706X/ © 2017 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

lack of studies addressing specifically this issue. In this scenario, we aimed to perform a systematic review of the literature on atypical lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis, addressing the clinic-epidemiologi-cal, diagnostic and therapeutic features of these uncommon lesions.

2. Material and methods

The present study represents a systematic review of literature. The searches were conducted via the international electronic databases Scopus and PubMed, on March 20th, 2015. The search terms browsed in the databases were “cutaneous leishmaniasis ” (Medical Subject Headings –MeSH), “atypical” and“unusual”, with 5-year time limit (2010–2015).

In order to reduce the risk of bias of individual studies, where a title or abstract seemed to describe a study eligible for inclusion, the articles were entirely examined to assess their relevance based on the inclusion criteria. Three independent researchers (CM, LC, GS) carried out a three-step literature search. Any discrepancies among the three re-viewers who, blind to each other, examined the studies for the possible inclusion were resolved by the senior author (ML).

The article analysis followed previously determined eligibility criteria. The studies must have met all the following criteria for inclusion: (1) manuscripts written in English; (2) articles addressing atypical lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis; and (3) prospective or retrospective observational (analytical or descriptive), experimental or quasi-experimental studies, or case report. Considering the scarce of data about atypical manifestations of CL, and that the cases are publicized in the literature mainly as case reports, we decided to include this type of publication in our search in order to better explore the uncommon lesions. The full text of the selected articles (sample) were obtained directly from the aforementioned databases, when freely available, or through Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) Portal of Journals, a virtual library linked to Brazil’s Ministry of Education and subjected to content subscription. We adopted the following exclusion criteria: (1) repeated articles in different databases; (2) non-original studies, including editorials, re-views, prefaces, brief communications, and letters to the editor; (3) full text not available; (4) author’s name not disclosed; and (5) out of context. Each paper in the sample was read in its entirety, and data elements were then extracted and entered into a spreadsheet that included authors, publication year, description of the study sample, and mainfindings.

Thus, to provide a better analysis, the next phase involved compar-ing the studies and groupcompar-ing, to facilitate our study the results regarding the studied subject were classified into four categories: characteristics of the atypical lesions, epidemiological features, immu-nological aspects, and considerations on treatment of the atypical forms.

To achieve a high standard of reporting we have adopted“Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses”(PRISMA) guidelines (http://www.prisma-statement.org/).

3. Results

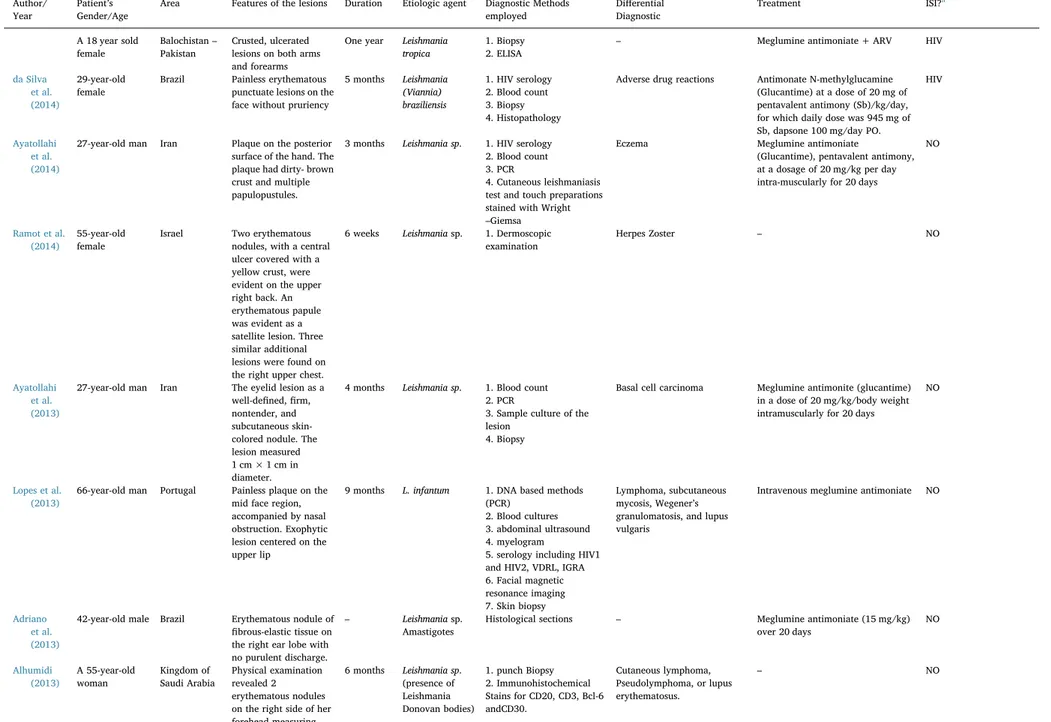

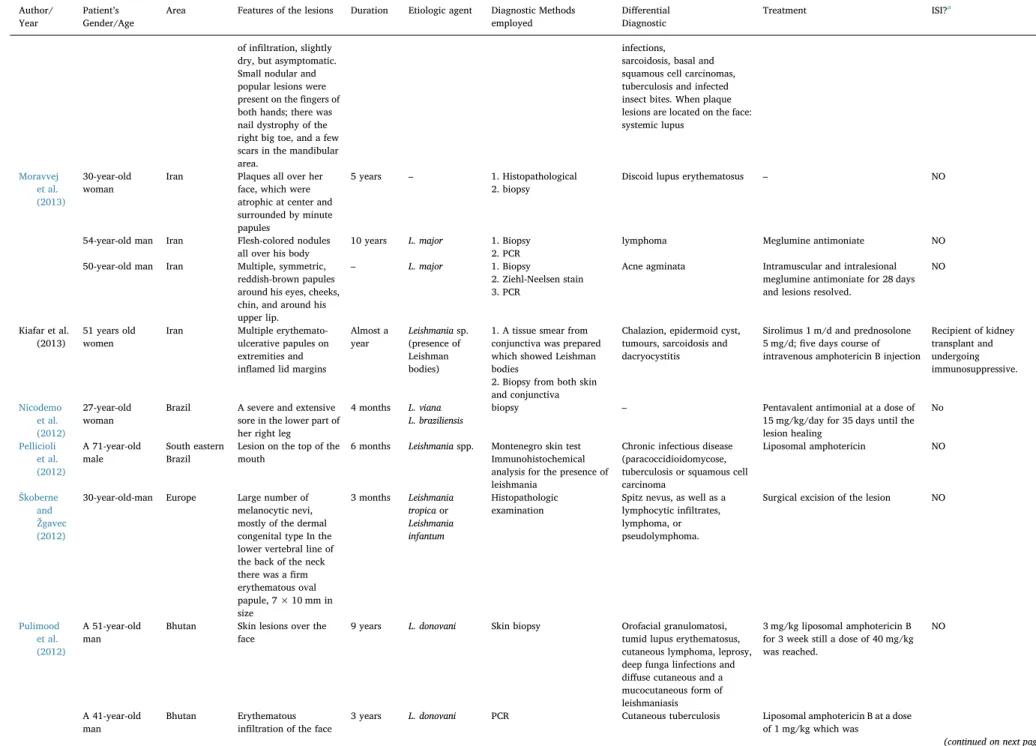

Initially, the aforementioned search strategies resulted in 109 references in Scopus and 57 references in PubMed. Forty-four of them were repeated in the two databases and were counted only once. After this, there were 13 different references counted in PubMed, ending in 122 articles to be analyzed. After analyzing title, abstract and text according to the eligibility criteria, 34 articles were included in thefinal sample (Fig. 1). From this total, 30 (88.23%) are case reports and 4 (11.76%) are case series (Table 1).Table 1shows the mainfindings of the sample, including information such as gender, age, geographic location, aspect and duration of the lesions, etiological agent, diff er-ential diagnostic and treatment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of the atypical lesions of CL

The classic initial clinical sign of the CL is the appearance of small papules and an erythematous nodule, which may be single or multiple, usually located in an exposed region of the tegument where, after a few months, it develops into ulcers, the most common presentation (63%–91% of cases), with indurated raised outer borders, regular contours and a cross-grained background with or without a seropuru-lent exudate (Adriano et al., 2013; Siah et al., 2014). Commonly, CL skin lesions have a wide variety of forms: round or oval; erythematous base, infiltrated and firm in consistency; well-defined, high edges; reddish background and coarse granules (Hepburn, 2003; Neitzke-Abreu et al., 2014).

In general, based on the studies selected, atypical lesions have included the following forms: erythematous volcanic ulcer, diffuse, eczematous, lupoid, verrucous, dry, zosteriform, nodular lesions, erysipeloid, sporotrichoid, annular (resembling a ringworm infection), paronychial, palmoplantar, and psoriasi form (Doudi et al., 2012; Faber et al., 2003; Iftikhar et al., 2003; Kafaie et al., 2010; Momeni and Aminjavaheri, 1994; Oryan et al., 2013; Raja et al., 1998; Ramot et al., 2014). Chancriform and annular were also reported in genital lesions (Faber et al., 2003; Iftikhar et al., 2003; Momeni and Aminjavaheri, 1994; Raja et al., 1998). It has also been reported leishmaniasis recidivans, in which small nodules develop around a healed scar; angiolupoid cutaneous leishmaniasis of the face, resembling lupus erythematosus; vegetating lesions with a papillomatous aspect and a soft moist consistency; and verrucous lesions with a dry rough surface, presence of small scabs and peeling (Hepburn, 2003; Neitzke-Abreu et al., 2014).

Clinically, localized cutaneous lesions may resemble other skin conditions, such as: blastomycosis, sporotrichosis, diverse fungal skin infections, cutaneous anthrax, eczema, lepromatous leprosy, tubercu-losis, Mycobacterium marinum infections, basal and squamous cell carcinomas (SCC), and infected insect bites (Akilov et al., 2007; Bari and Rahman, 2008; Ceyhan et al., 2008; Dassoni et al., 2013; de Brito et al., 2012). Syphilis has been also reported in the differential diagnosis (Neitzke-Abreu et al., 2014; Talat et al., 2014).

When the plaque lesions of CL are located on the face: systemic lupus erythematosus, discoid lupus erythematosus, lupus vulgaris, cutaneous lymphoma and erysipelas are in the differential diagnosis (Akilov et al., 2007; Bari and Rahman, 2008; Ceyhan et al., 2008; Dassoni et al., 2013; de Brito et al., 2012). Although erysipelas-like presentation of CL is rarely reported, its clinical features include erythematous infiltrative ill-defined plaque over the face covering the nose and both cheeks (David and Craft, 2009; Robati et al., 2011). The papulonodular form clinically may resemble sarcoidosis, acne rosacea or acneitis (Douba et al., 2012).

Sometimes, there are multiple erythematous nodules mimicking cutaneous lymphoma or pseudolymphoma. The typical microscopic findings are mixed inflammatory infiltrate with many histiocytes and granuloma formation containing Leishman-Donovan bodies (Alhumidi, 2013; Murray et al., 2005).

Ramot et al. (2014) have reported a case which three similar additional lesions were found on the right upper chest, forming a seemingly dermatomal distribution of lesions, leading to the clinical impression of herpes zoster. Similarly,Kafaie et al. (2010)reported a case with a zosteriform and multidermatomal lesion, around a scar tissue on the left lower part of the back, flank, and abdomen with papules, and pseudovesicular lesions on an erythematous background. These cases demonstrate the importance of including herpes zoster in the differential diagnosis. Furthermore, since dermoscopy can be easily utilized to diagnose this condition, dermatologists in endemic areas should be familiar with its typical dermoscopic features. Regarding differential diagnosis,Kafaie et al. (2010)have also mentioned lupus

C.B. Meireles et al. Acta Tropica 172 (2017) 240–254

vulgaris that tuberculin test is usually positive and there is necrosis in histopathology; subcutaneous and deep mycosis in which smear and histopathology are diagnostic; and other granulomatous disease such as sarcoidosis, granuloma annulare and lymphocytic infiltration have some different clinical and histopathological features and treatment regimens (Fig. 2).

Neitzke-Abreu et al. (2014) reported a case which lymphadenitis was present, as well as three open skin lesions with crusts and exudate, up to 1.5 cm in diameter. According to the authors, this clinical picture, together with the rupture of the vesicles and the appearance of new lesions adjacent to the original lesion, is not typical of CL.

Vasudevan and Bahal (2011)brought an interesting case in which thefirst and main sign was swelling upper lip. Local examination of the face revealed a 4 × 3 cm nodular, indurated, swelling with well-defined edges over the upper lip and extending into the labial mucosa. The center of the nodule was ulcerated and tender, with overlying crusting and pus discharge.

It is also important to remember that is generally accepted that secondary bacterial infection of the CL lesions can influence the size, shape and severity of these skin lesions and may also delay or prevent the healing process (Piscopo and Mallia Azzopardi, 2007). In general, the incidence of secondary bacterial infections in the lesions of CL ranged from 21.8% to 54.2% (Siah et al., 2014; Ziaie and Sadeghian, 2008). However, in a study evaluating the occurrence of secondary infection, among 602 patients with CL and 283 patients with non-CL skin lesions, bacteria were isolated from the skin lesions of 402 (66.8%) and 183 (64.7%), respectively. The secondary bacterial infections were observed in about 70% of volcano-shape, 60% of psoriasi form and 25% of papular forms of CL (Doudi et al., 2012).

Da Silva et al. (2014) reported a case of leishmaniasis/HIV

coin-fection presenting diffuse desquamative rash lesions, which in their opinion could have been easily interpreted as adverse drug reactions.

The reason for clinical cutaneous leishmaniasis pleomorphism is unclear, but variations in parasite virulence and host factors, including abnormal host immune response, malnutrition, and immunosuppres-sion have been postulated to affect the presentation (Murray et al., 2005; Siah et al., 2014).

4.2. Epidemiological features

The disease is endemic in 88 countries, and World Health Organization (WHO) estimates 10 million people suffer cutaneous leishmaniasis (Bailey and Lockwood, 2007; Dassoni et al., 2013; Oryan et al., 2013; Siah et al., 2014). Cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused byL. tropica,L. majorandL. aethiopicain old world, which are present in southern Europe, North Africa, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, and Central Asia (Table 1) (Guddo et al., 2005; Siah et al., 2014). It is endemic in the province of Balochistan in Pakistan (Talat et al., 2014), in central Iran (Ayatollahi et al., 2015), in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Alhumidi, 2013), in Ethiopia–caused mainly byL. aethiopica– and in many other world regions (Dassoni et al., 2013).

In North Africa and the Middle East, the majority of cases are caused byLeishmania majorandL. tropica. Curiously, in southwestern European countries, such as Portugal, Spain, Italy, France, and Malta,L. infantum is the main species that has been identified as a causative agent of autochthonous cutaneous leishmaniasis in humans (del Giudice et al., 1998; Lopes et al., 2013).

In Iran, there have been about 20,000 new cases annually. Leishmania tropicawith about 25% andL. majorwith 75% frequency Fig. 1.Flow chart showing study selection for the review.

C.B. Meireles et al. Acta Tropica 172 (2017) 240–254

Table 1

Mainfindings of the sample on atypical lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis (between 2010 AND 2015).

Author/ Year

Patient’s Gender/Age

Area Features of the lesions Duration Etiologic agent Diagnostic Methods employed

Differential Diagnostic

Treatment ISI?a

Case reports

Ayatollahi et al. (2015)

35-year-old man Iran Large erythematous plaque, 10 cm–20 cm in

size, studded with small nodules,

pseudovesicles, and papules on the back of the neck.

4 months – 1. Blood count,

2. HIV serology, 3. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 4. C-reactive protein 5. Routine biochemical tests,

6. urine analysis, 7. chest radiography, 8. intradermal purified protein

9. derivative skin test 10. Culture of the biopsy specimen

11. Gram smear prepared from the lesion

– He had been treated with many antibiotics, including Cephalexin, cloxacillin, penicillin, andacyclovir, beforetherightdiagnosis. Meglumineantimoniate at adose of 20 mg/kg body weight

intramuscularly daily for 20 days. After 3 months, almost all the lesions had cleared.

NO

Siah et al. (2014)

61-year-old man Ibiza–Spain Erythematous, edematous plaque with central crust and superficial ulceration on the right temple and prominent periorbital edema resembling erysipelas.

3 months Leishmania donovani

1. Incisional biopsy– Giemsa staining 2. Skin biopsy PCR 3. Blood test

Erysipela Intravenous sodium stibogluconate (20 mg/kg) for 20 days.

NO

Neitzke-Abreu et al. (2014)

A 61-year-old female

Maringá– Brazil

Vesicular lesion appeared on her neck, not ulcerated, with prominentfluid accumulation, intense pruritus, and subsequent swelling and redness, without fever.

7 months L.(V.)

braziliensis

1.Culture in blood base agar (BBA)

2. IIF test for

anti-LeishmaniaIgG antibodies 3. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) 4. Montenegro skin test (MST)

5. nodule puncture by direct microscopy

Syphilis, leprosy, tuberculosis, fungal infections, and tumors

N-methylglutamineantimoniate (Glucantime™) 20 mg/kg by intramuscular injection for 20 days.

NO

Talat et al. (2014)

A 40 years old male

Balochistan– Pakistan

Black crusted lesions on his left hand later spreading to the rest of his body appearing erythematous at various places and annular. On his face, he had black raised maculopapular lesions. Deep ulcer on ventral aspect of his tongue with eroded lesions and a few vesicles, with white coating on his palate. His genitals also had maculopapular lesions on the scrotum and corona sulcus.

One year Leishmania tropica

1. Biopsy

2. RPR and TPHA tests

Syphilis Meglumine antimoniate and antiretroviral therapy (ARV)

HIV

(continued on next page)

C.B.

Meireles

et

al.

Act

a Tro

pica 1

72

(2

01

7) 2

40

–2

54

Table 1(continued)

Author/ Year

Patient’s Gender/Age

Area Features of the lesions Duration Etiologic agent Diagnostic Methods employed

Differential Diagnostic

Treatment ISI?a

A 18 year sold female

Balochistan– Pakistan

Crusted, ulcerated lesions on both arms and forearms

One year Leishmania tropica

1. Biopsy 2. ELISA

– Meglumine antimoniate + ARV HIV

da Silva et al. (2014)

29-year-old female

Brazil Painless erythematous punctuate lesions on the face without pruriency

5 months Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis

1. HIV serology 2. Blood count 3. Biopsy 4. Histopathology

Adverse drug reactions Antimonate N-methylglucamine (Glucantime) at a dose of 20 mg of pentavalent antimony (Sb)/kg/day, for which daily dose was 945 mg of Sb, dapsone 100 mg/day PO.

HIV

Ayatollahi et al. (2014)

27-year-old man Iran Plaque on the posterior surface of the hand. The plaque had dirty- brown crust and multiple papulopustules.

3 months Leishmania sp. 1. HIV serology 2. Blood count 3. PCR

4. Cutaneous leishmaniasis test and touch preparations stained with Wright –Giemsa

Eczema Meglumine antimoniate

(Glucantime), pentavalent antimony, at a dosage of 20 mg/kg per day intra-muscularly for 20 days

NO

Ramot et al. (2014)

55-year-old female

Israel Two erythematous nodules, with a central ulcer covered with a yellow crust, were evident on the upper right back. An erythematous papule was evident as a satellite lesion. Three similar additional lesions were found on the right upper chest.

6 weeks Leishmaniasp. 1. Dermoscopic examination

Herpes Zoster – NO

Ayatollahi et al. (2013)

27-year-old man Iran The eyelid lesion as a well-defined,firm, nontender, and subcutaneous skin-colored nodule. The lesion measured 1 cm × 1 cm in diameter.

4 months Leishmania sp. 1. Blood count 2. PCR

3. Sample culture of the lesion

4. Biopsy

Basal cell carcinoma Meglumine antimonite (glucantime) in a dose of 20 mg/kg/body weight intramuscularly for 20 days

NO

Lopes et al. (2013)

66-year-old man Portugal Painless plaque on the mid face region, accompanied by nasal obstruction. Exophytic lesion centered on the upper lip

9 months L. infantum 1. DNA based methods (PCR)

2. Blood cultures 3. abdominal ultrasound 4. myelogram

5. serology including HIV1 and HIV2, VDRL, IGRA 6. Facial magnetic resonance imaging 7. Skin biopsy

Lymphoma, subcutaneous mycosis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and lupus vulgaris

Intravenous meglumine antimoniate NO

Adriano et al. (2013)

42-year-old male Brazil Erythematous nodule of

fibrous-elastic tissue on the right ear lobe with no purulent discharge.

– Leishmaniasp. Amastigotes

Histological sections – Meglumine antimoniate (15 mg/kg) over 20 days

NO

Alhumidi (2013)

A 55-year-old woman

Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Physical examination revealed 2 erythematous nodules on the right side of her forehead measuring

6 months Leishmania sp. (presence of Leishmania Donovan bodies)

1. punch Biopsy 2. Immunohistochemical Stains for CD20, CD3, Bcl-6 andCD30.

Cutaneous lymphoma, Pseudolymphoma, or lupus erythematosus.

– NO

(continued on next page)

C.B.

Meireles

et

al.

Act

a Tro

pica 1

72

(2

01

7) 2

40

–2

54

Table 1(continued)

Author/ Year

Patient’s Gender/Age

Area Features of the lesions Duration Etiologic agent Diagnostic Methods employed

Differential Diagnostic

Treatment ISI?a

1 × 2 cm, and another on her left cheek measuring 0.8 × 1.3 cm.

Hajjaran et al. (2013)

A 41-year-old man

Iran Cutaneous lesions were papulonodular, infiltrated without any typical form. The lesions were painless. The lesions disseminated to entire body, with the exception of the palms

6 months L. major 1. Smears prepared from

fluid materials of some of the skin lesions, stained with Giemsa 10% 2. cultured in special medium such as RPMI 1640 (Gibco) plus 10% FBS (Gibco)

3. PCR-RFLP 4. Electrophoresis.

– – NO

A 59-year-old man

Cutaneous lesions, looks like papulonodular reddish-brown and were infiltrated without any typical form

6–8 months

– Meglumine antimoniate NO

46 year-old man

Lesions expanded all over his hand. The lesions also dominated palms and nails. No favorable responses were observed after 12 years of treatment because the ulcers were active.

22 years – Glucantime Exposed to

the side-effects of a chemical bomb during the war

40 year-old woman

Multiple lesions on her body including hands, chest, and backs. After treatment, not only the lesions show any healing but also they were extended to new site of her body.

1 year – Glucantime NO

Dassoni et al. (2013)

18-year-old male Northern Ethiopia

Nodular erythematous lesions on his face (nose, ears, cheeks), hands and forearms, causing deformity of the nose, associated with multiple, large hypopigmented patches on the trunk, limbs and buttocks and some dry scaling on the lower limbs. The patches were bilateral,flat, dry and not infiltrated

4 years Leishmania

(amastigotes)

1. Ziehl-Nielsen Stain 2. Giemsa stain 3. Punch biopsy 4. Tested for loss of cutaneous Sensation.

Leprosy Meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime Sanofi) i.m. for 28 days

NO

20-year-old male Multiple, bilateral, hypopigmented patches on his limbs and buttocks. The patches wereflat with no signs

6 years L. aethiopica Blastomycosis, sporotrichosis, cutaneous anthrax, eczema, fungal skin infections, lepromatous leprosy,

Mycobacterium marinum

– NO

(continued on next page)

C.B.

Meireles

et

al.

Act

a Tro

pica 1

72

(2

01

7) 2

40

–2

54

Table 1(continued)

Author/ Year

Patient’s Gender/Age

Area Features of the lesions Duration Etiologic agent Diagnostic Methods employed

Differential Diagnostic

Treatment ISI?a

of infiltration, slightly dry, but asymptomatic. Small nodular and popular lesions were present on thefingers of both hands; there was nail dystrophy of the right big toe, and a few scars in the mandibular area.

infections, sarcoidosis, basal and squamous cell carcinomas, tuberculosis and infected insect bites. When plaque lesions are located on the face: systemic lupus

Moravvej et al. (2013)

30-year-old woman

Iran Plaques all over her face, which were atrophic at center and surrounded by minute papules

5 years – 1. Histopathological 2. biopsy

Discoid lupus erythematosus – NO

54-year-old man Iran Flesh-colored nodules all over his body

10 years L. major 1. Biopsy 2. PCR

lymphoma Meglumine antimoniate NO

50-year-old man Iran Multiple, symmetric, reddish-brown papules around his eyes, cheeks, chin, and around his upper lip.

– L. major 1. Biopsy

2. Ziehl-Neelsen stain 3. PCR

Acne agminata Intramuscular and intralesional meglumine antimoniate for 28 days and lesions resolved.

NO

Kiafar et al. (2013)

51 years old women

Iran Multiple erythemato-ulcerative papules on extremities and inflamed lid margins

Almost a year

Leishmaniasp. (presence of Leishman bodies)

1. A tissue smear from conjunctiva was prepared which showed Leishman bodies

2. Biopsy from both skin and conjunctiva

Chalazion, epidermoid cyst, tumours, sarcoidosis and dacryocystitis

Sirolimus 1 m/d and prednosolone 5 mg/d;five days course of intravenous amphotericin B injection

Recipient of kidney transplant and undergoing immunosuppressive.

Nicodemo et al. (2012)

27-year-old woman

Brazil A severe and extensive sore in the lower part of her right leg

4 months L. viana L. braziliensis

biopsy – Pentavalent antimonial at a dose of 15 mg/kg/day for 35 days until the lesion healing

No

Pellicioli et al. (2012)

A 71-year-old male

South eastern Brazil

Lesion on the top of the mouth

6 months Leishmaniaspp. Montenegro skin test Immunohistochemical analysis for the presence of leishmania

Chronic infectious disease (paracoccidioidomycose, tuberculosis or squamous cell carcinoma

Liposomal amphotericin NO

Škoberne and Žgavec (2012)

30-year-old-man Europe Large number of melanocytic nevi, mostly of the dermal congenital type In the lower vertebral line of the back of the neck there was afirm erythematous oval papule, 7 × 10 mm in size

3 months Leishmania tropicaor

Leishmania infantum

Histopathologic examination

Spitz nevus, as well as a lymphocytic infiltrates, lymphoma, or pseudolymphoma.

Surgical excision of the lesion NO

Pulimood et al. (2012)

A 51-year-old man

Bhutan Skin lesions over the face

9 years L. donovani Skin biopsy Orofacial granulomatosi, tumid lupus erythematosus, cutaneous lymphoma, leprosy, deep funga linfections and diffuse cutaneous and a mucocutaneous form of leishmaniasis

3 mg/kg liposomal amphotericin B for 3 week still a dose of 40 mg/kg was reached.

NO

A 41-year-old man

Bhutan Erythematous infiltration of the face

3 years L. donovani PCR Cutaneous tuberculosis Liposomal amphotericin B at a dose of 1 mg/kg which was

(continued on next page)

C.B.

Meireles

et

al.

Act

a Tro

pica 1

72

(2

01

7) 2

40

–2

54

Table 1(continued)

Author/ Year

Patient’s Gender/Age

Area Features of the lesions Duration Etiologic agent Diagnostic Methods employed

Differential Diagnostic

Treatment ISI?a

and the palate subsequently increased to 3 mg/kg.

He was given a total of 2.6 g of the drug over a period of 3 weeks

Miller et al. (2012)

23-year-old male USA Slowly expanding, painful, ulcerated nodule on the left dorsal

fifth digit Palpable lymphadenopathy of the left ventral forearm, antecubital fossa and axilla. (Two months prior to the visit, he traveled in rural Peru)

1 month L. (Viannia) panamensis

PCR sporotrichosis or other deep fungal infection

Pentavalent antimony for 21 days NO

Sindhu and Ramesh (2012)

49-year-old man Himalaya Erythematous coalescing papules arranged linearly on the radial aspect of the dorsum of his right hand

8 months Leishmania tropica

PCR Sporotrichosis Intralesional sodium stibogluconate 1–2 ml (100 mg/ml) every 2 weeks

NO

60-year-old woman

India Lesions on the abdomen Ulcer on the left foot

1 year 2 months

Histopathological examination

Sarcoidosis and granuloma annular.

1 g (10 ml) of sodium stibogluconate daily by the intravenous route.

Nasiri et al. (2012)

10 years old boy – complaint of painless wound on his lower lip

5 months – Skin smear Cutaneous tuberculosis, Basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma

Intramuscular injection of Glucantim (10 mg/kg) pentavalent

antimonial was started for 10 days. NO

Sharquie and Hameed (2012)

36-year-old male Iraq Large ulcerative plaque on the dorsal aspect of the left foot surrounded by two satellite purple papules. In addition to multiple grouped dusky erythematous nontender ulcerative nodules behind the lateral malleolus of the left leg.

2 months Leishmania tropica

Histological examination – Intralesional sodium stibogluconate (100 mg per 1 ml) for each lesion weekly for 5 successive weeks with excellent gradual resolution of all skin lesions

NO

45-year-old female

Two nontender, nonulcerative, indurated dusky erythematous plaques on her upper anterior chest.

10 weeks 1. chest XR 2. complete bloodfilm 3. liver and renal function test

4. abdominal sonography 5. punchbiopsy

– Topical zincsulphate solution 20% twice daily application combined with oral zincsulphate 200 mg thrice daily for a one-month duration

NO

Robati et al. (2011)

35-year-old man Afghanistan and Iran

Infiltrated cutaneous lesion with progressive, painful, abnormal enlargement of the left auricle

6 months – A direct examination of tissue smears stained with Giemsa

zosteriform, erysiploid, lupoid, sporotrichoid, eczematoid, hyperkeratotic, warty and impetiginized lesions

Intramuscular meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime)

NO

Mnejja et al. (2011)

63-year-old woKman

Sfax−

Tunisia

Erythematous infiltrative plaque covering the center of the face (nose and cheeks) with a grossly symmetrical pattern of 5 cm lesions covered by

1 month Leishmania Amastigotes forms.

1. tissue smears 2. Biopsy

Disseminated or discoid lupus erythematous, lupus vulgaris, sarcoidosis or erysipelas

10 mg/kg per day systemic meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime®)

After an accidental trauma

(continued on next page)

C.B.

Meireles

et

al.

Act

a Tro

pica 1

72

(2

01

7) 2

40

–2

54

Table 1(continued)

Author/ Year

Patient’s Gender/Age

Area Features of the lesions Duration Etiologic agent Diagnostic Methods employed

Differential Diagnostic

Treatment ISI?a

places with crusts.

Poeppl et al. (2011)

59-year-old woman

Austria Dense, non-tender, subcutaneous pasty swelling involving a 5 × 7 cm area on the right cheek

8 months L. donovani/

infantum

complex

1. Blood count 2. Biochemical parameters 3. Biopsy

4. PCR

cheilitis granulomatous Systemic treatment with miltefosine was started (50 mg

by mouth three times daily for 28 days)

NO

Soni et al. (2011)

40-year-old male India Numerous painless, itchy, discrete, non-tender nodules and plaques of variable size, distributed

asymmetrically over limbs and face

1 year L. tropica 1. skin smear 2. biopsy 3. PCR 4. Blood count 5. ELISA

– HAART (zidovudine, lamivudine, and nevirapine) with intramuscular injection of SSG

HIV

34-year-old male Well-defined, non-tender lesions of different size

6 months 1. skin smear 2. biopsy 3. PCR 4. ELISA

Oral Rifampicin was started at a dose of 1200 mg/day for 6 weeks

28-year-old man With single asymptomatic, non-tender lesion

6 months 1. skin smear 2. biopsy 3. PCR 4. ELISA

Oral Rifampicin 1200 mg/day for 6 weeks

Vasudevan and Bahal (2011)

26-year-old male Rajasthan– India

4 × 3 cm nodular, indurated, swelling with well-defined edges over the upper lip and extending into the labial mucosa. The center of the nodule was ulcerated and tender, with overlying crusting and pus discharge.

6 months Leishman-Donovan (LD)

1. FNAC (fine needle aspiration cytology) 2. ELISA 3. Blood count

Insect bite reaction and cutaneous tuberculosis

Intralesional sodium stibogluconate once a week for 4 weeks and tablet ketoconazole 400 mg once daily for the same duration

NO

Kafaie et al. (2010)

39-year-old man Iran Multiple erythematous plaques studded with papules, pseudovesicles, and small nodules around previous scar tissue on the left lower portion of the back and abdomen.

2 months – 1. skin smear 2. biopsy 3. PCR 4. Blood count

Herpes Zoster Antimoniate in a dose of 20 mg/kg body weight intramuscularly daily for 20 days, and liquid-nitrogen cryotherapy every other week.

NO

Eryilmaz et al. (2010)

49-year-old male Turkey Multiple nodules exhibiting arciform arrangement on the lateral side of the left leg.

3 months Leishmania sp. Amastigotes

1. Biopsy 2. PCR 3. Blood count

4. Liver and renal function tests

5. ECG

Erysipelas Meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) 20 mg/kg/d (b.i.d, deep I.M) for 14 d.

NO

Cases Series

Oryan et al. (2013)

60 men and 40 women; ages ranged from 0.7 to 84 years (average 25 years old).

Iran Out of a total of 100 patients, 34 (34%) had unusual presentations. Most common was erythematous leishmaniasis with 12 patients, followed by volcanic ulcer 6, multi

varied between 15 days AND 4 years (average 2 months).

Leishmania major

andL. tropica

were detected in 97 cases and 1 case, respectively.

1. Histological examination 2. Nested-PCR 3. sequencing

– – –

(continued on next page)

C.B.

Meireles

et

al.

Act

a Tro

pica 1

72

(2

01

7) 2

40

–2

54

Table 1(continued)

Author/ Year

Patient’s Gender/Age

Area Features of the lesions Duration Etiologic agent Diagnostic Methods employed

Differential Diagnostic

Treatment ISI?a

infection 5, lupoid 4, diffuse 3, eczematous 3, verrucous 2, dry 1 and nodular 1. Free Leishman bodies and intracytoplasmic Leishman bodies were observed

microscopically

Saab et al. (2012)

57 cases Lebanon, Syriaand Saudi Arabia (1992–2010)

Of the 145 patients, 125 were reconfirmed as cutaneous leishmaniasis by PCR. Eighteen cases presented with a pre-biopsy clinical diagnosis other than cutaneous leishmaniasis that ranged from dermatitis to neoplasm. Of the 125 cases, 57 showed a major histopathological pattern other than cutaneous leishmaniasis.

18 years L. tropica, L. major, L.braziliensis, L. donovani, L.aethiopica L. infantum

Skin biopsies from untreated patients with histopathological and/or clinical suspicion of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Diagnosis was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) followed by molecular sub-speciation

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC, six cases),

granulomatous inflammation (three cases) sarcoidosis (two cases), lymphoma (two cases), atypical mycobacterial infection (two cases), cutaneous lupus erythematosus (one case), deep fungal infection (one case) and tuberculosis (TB, one case)

– –

Douba et al. (2012)

6000 patients with

leishmaniasis, of which 1750 were of the chronic type

Allepo, Síria The papulonodular form comprised 47% of all cases of chronic CL. Lesions were multiple in 96% of cases, most commonly affecting the face and children (89%)

12 years L. tropica PCR Sarcoidosis, acne rosacea or acneitis, tumours such as eccrine poromas, lymphomas and amelanotic melanomas

1Intra-muscular administration of antimonials at a daily Doseof 20 mg/ kg for 20 consecutive days 2 Cryotherapy using liquid nitrogen was used once weekly for4 weeks

High predilection to occur in pregnant women affecting 47 pregnant women, who represented around 58% of all cases of the tumoral CCL cases

Doudi et al. (2012)

855 patients Rural area north of Isfahan, Iran

Chronic ulcerating skin lesions in the tropics

2–4 weeks Zoonotic Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Bacteria

Two samples were used to prepare methanol-fixed and Giemsa-stained mears for direct microscopy and observation of amastigotes; The third sample was inoculated into sterile screw top tubes containing 10 ml of Novey-Nicol-Mac Neal (NNN) medium and incubated at 20–25 °C. They were examined

microscopically for the development of promastigotes at 2-day intervals for 2 weeks

Bacterial superinfection Ciprofloxacin, cefazolin, and erythromycin are the most effective antibiotics against Gram-positive bacteria, and ciprofloxacin and clindamycin are the most effective antibiotics against Gram-negative bacteria.

NO

aISI, Immunosuppression involvement.

C.B.

Meireles

et

al.

Act

a Tro

pica 1

72

(2

01

7) 2

40

–2

54

Fig. 2.Cases of atypical cutaneous leishmaniasis in regard of form or location: a) erysipeloid form; b) lupoid form; c) annular; d) volcanic ulcer; e) verrucous lesion; f) tumor form; g) psoriasis form; h) impetigo form; i) lesion at eyelid; j) axillary papules. All images were obtained at Tropical diseases ambulatory of the Faculty of medicine, Federal University of Cariri.

C.B. Meireles et al. Acta Tropica 172 (2017) 240–254

are the main etiological agents for both anthroponotic and zoonotic CL that were reported in more than 18 out of 31 provinces of Iran (Hajjaran et al., 2013). Interestingly, some reports have shown thatL. tropica,which is commonly associated with CL in old world, is the main agent of visceral leishmaniasis in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-infected patients in Iran (Hajjaran et al., 2013; Jafari et al., 2010). In this country, according to the articles included, the most documented lesions were nodular, papulonodular, atrophic and ulcer-ating (Ayatollahi et al., 2013, 2015, 2014; Doudi et al., 2012; Hajjaran et al., 2013; Kafaie et al., 2010; Kiafar et al., 2013; Moravvej et al., 2013; Oryan et al., 2013). In Tunisia, it has become a very common disease for several years, with an endemo-epidemic mode of evolution (Robati et al., 2011). The desert of Rajasthan state and Himachal Pradesh in India is another endemic area for CL, where it is caused by Leishmania tropica(Soni et al., 2011). In Spain, as in Pakistan, there was a predominance of crusted lesions. (Siah et al., 2014)

Analyzing other atypical forms, cases of CL in its erysipeloid form have been reported in Iran, Pakistan, Turkey and Tunisia (David and Craft, 2009; Masmoudi et al., 2007; Raja et al., 1998; Salmanpour et al., 1999). In the literature, the incidence rate of erysipeloid form of CL ranges between 0.05 and 3.2% (David and Craft, 2009; Salmanpour et al., 1999).

In the Western hemisphere, the disease is endemic in parts of Central America, including Mexico, and countries of South America, including Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, Colombia, French Guyana, and Brazil (González et al., 2008). So-called New World Leishmania infection most commonly presents as localized cutaneous leishmaniasis, either byL. mexicanaspecies orL. (Viannia) braziliensisorL. guyanensissubspecies (Pulimood et al., 2012).

It is a public health issue in Latin America, with an increase in its incidence, for instance, in several states in Brazil (Nicodemo et al., 2012). In this country, CL cases are mainly due toLeishmania (Viannia) braziliensis, which causes lesions that if left untreated may result in the mucosal form, which is characterized by disfiguring lesions (Hepburn, 2003; Neitzke-Abreu et al., 2014). In Brazil, among the atypical cases reported in the literature, the most evident was the vesicular type (Adriano et al., 2013; Neitzke-Abreu et al., 2014; Nicodemo et al., 2012). In the unique study analyzed from USA, an ulcerating lesion was reported (Miller et al., 2012).

4.3. Immunological aspects

One of the key elements that determine the clinical picture and the course of an infectious disease like CL is the host defense mechanism (Moravvej et al., 2013). The incidence of leishmaniasis as an opportu-nistic disease has increased in recent years because of the growing number of patients with immune depression secondary to chronic illnesses, neoplasms, immunosuppressive treatments, transplants, and HIV infection (Ayatollahi et al., 2014; Sharquie and Najim, 2004).

Parasite control in CL is known to be associated with the develop-ment of a Th1 response characterized by the production of the cytokines interleukin-12 (IL-12), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and interferon gamma (IFN-γ). Th2 response pattern usually involves the production of IL-4, IL-10 and probably other regulatory cytokines, but it fails to control theLeishmaniainfection. However, this dichotomy is not so clear in human infection (Castellano et al., 2009; Nicodemo et al., 2012).

A very important cofactor for reactivation of the disease is a co-infection with HIV, which along with malnutrition is a very important cause of worsening of leishmaniasis with atypical clinical presentation and occurrence of reactivated lesions of CL. Such presentations respond poorly to the standard treatment and frequent relapses are noted (Talat et al., 2014). HIV-infection increases the risk of developing leishma-niasis between 100 and 1000 times (Vasudevan and Bahal, 2011). In such patients, leishmaniasis appears with a decrease in immunity as HIV advances, with most of the patients having a CD4+ count of less

than 200 cells/mm3(Talat et al., 2014).

Both agents (Leishmaniaand HIV) infect and multiply in monocytes, and in the case of a co-infection, there is a mutual replication of both in host cells. In fact, a leishmaniasis infecting myeloid cells promotes HIV replication while HIV, in turn, promotes an uptake of leishmanias by macrophages and amplifies parasitic replication in monocytes (Habibzadeh et al., 2005; Talat et al., 2014). Thus, patients presenting with leishmaniasis and sudden onset of weight loss, with or without systemic symptoms, should be considered for HIV with leishmaniasis (Talat et al., 2014).

Soni et al. (2011)reported three cases of localized and disseminated CL due to Leishmania tropica associated with HIV which failed to respond to conventional intralesional/intramuscular sodium stiboglu-conate (SSG) injections. Unusual lesions and ones which respond poorly to the standard treatment and causes frequent relapses may be attributed to an altered host response, like in HIV patients, or owing to an atypical strain of parasites in these lesions (Kafaie et al., 2010; Soni et al., 2011).

In addition,Chiheb et al. (2012)elucidated three atypical cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis by L. major in diabetic patients. Diabetes mellitus can compromise T-cell response and contribute to the exten-sion and atypical presentation of the infection and predisposition to superinfections seen in leishmaniasis patients (Alvar et al., 2008; Lopes et al., 2013).

Other patient conditions that can interfere in immunity and favor CL are altered host immune response due to senility, and hormonal changes at menopause (Chiheb et al., 2012; Masmoudi et al., 2007; Salmanpour et al., 1999). Skin quality alteration due to aging were evoked to explain the erysipeloid form in the study of Mnejja et al. (2011). It was also elucidated by them that post-traumatic cutaneous lesions can facilitate the occurrence of this type of disease (Ceyhan et al., 2008; Robati et al., 2011).

Other situations like a patient recipient of kidney transplant under-going immunosuppressive treatment (Kiafar et al., 2013), inflammation of the upper respiratory tract, associated with smoke (Benítez et al., 2001; Bodet et al., 2002; Ozdemir et al., 2007; Tiseo et al., 2008), or chronic respiratory diseases (Bodet et al., 2002; Teemul et al., 2013), could also play an important role in atypical tegumentary leishmaniasis in different places (Ayatollahi et al., 2013).

Once infected with CL the chances of re-infection by the same species ofLeishmaniaare very unlikely, due to lifelong immunity. This scenario can happen in the presence of immunosuppressive diseases such as AIDS (Talat et al., 2014).

Multiple scattered lesions over different areas of the body are usually associated to an underlying deficiency in cellular immunity, however, in an immunocompetent person, it may be due to multiple bites of sandfly (Talat et al., 2014). Such immune condition can favor the development of diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis, this form is not common and usually presents with widespread nodules and plaques that do not ulcerate and the lesions contain high amount of organisms (Dassoni et al., 2013).

Ayatollahi et al. (2015)have proposed basal cell carcinoma as a differential diagnosis for their patient. Early detection of the infection is necessary in order to start effective treatment and prevention from inappropriate prescribing of drugs. In this scenario, it is important to elucidate that prednisolone- and methotrexate(MTX)-induced immuno-suppression may cause the extension of CL lesions, like was observed in Moravvej et al. (2013) in which the patient, a 54-year-old man presented with a 10-year-history offlesh-colored nodules all over his body, had been treated with MTX and chemotherapeutic drugs for lymphoma. Based on this experience, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is recommended to be used to determine the presence ofLeishmaniain endemic area when immunosuppression is used in treatment of the primary diagnosed disease and no improvement is seen (Moravvej et al., 2013). Anyway, the reliable identification of the causative agent of CL, either in typical or atypical lesions, using the molecular methods

C.B. Meireles et al. Acta Tropica 172 (2017) 240–254

is essential for treatment, control and prevention of the disease (Hajjaran et al., 2013). However, its use is often limited by the availability of laboratory infrastructure and cost (Siah et al., 2014).

4.4. Considerations on treatment of the atypical forms

There are no established guidelines for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis. The treatment depends on the immune status of the host, the area of the body involved, and the different susceptibility of the Leishmaniaspecies. The majority of lesions are self-healing, leading to flat atrophic scars. However, it is currently accepted that lesions should be treated in order to reduce both the residual scar and recovery time, and to avoid the transmission of the parasite (Rassi et al., 2008; Talat et al., 2014).

Pentavalent antimonials remain asfirst line treatment for all forms of leishmaniasis even for HIV-infected patients and atypical forms. In these cases, a closer follow up is needed (Aguado et al., 2013; Ayatollahi et al., 2013; Faucher et al., 2011; González-Anglada et al., 1994; Neves et al., 2009; Rosatelli et al., 1998; Talat et al., 2014). The recommended dose for cutaneous leishmaniasis is 20 mg of pentavalent antimonial per kg/day for 20–28 days, which can be given intrave-nously or intramuscularly (Lopes et al., 2013). The intra-lesional administration of pentavalent antimony is reported as a therapeutic option in some forms of cutaneous leishmaniasis, depending on the number, localization, and extension of the lesions. With this approach, it is possible to increase drug concentration in the lesions, reduce systemic side effects and costs, and obtain good esthetic results (Lopes et al., 2013). Although pentavalent antimonial drugs accelerate cure and reduce scarring, they can potentially cause serious side effects such as cardiotoxicity (Soares-Bezerra et al., 2004; Kiafar et al., 2013).

Liposomal amphotericin B is another option. Its mechanism of action is attributed to ergosterol binding, leading to membrane perme-ability and modification of the osmotic balance of the parasite (Lopes et al., 2013; Ziaie and Sadeghian, 2008). Some authors consider that pentavalent antimonials should be replaced by this treatment, which has fewer side effects. Liposomal amphotericin B is administered intravenously at a dose of 1–1.5 mg/kg/day for 21 days or 3 mg/kg/ day for 10 days (Lopes et al., 2013; Rassi et al., 2008). In some countries, it is the first line treatment reserved for severe forms of leishmaniasis, such as mucosal and visceral leishmaniasis and HIV co-infected patients. Pentamidine is also a second line treatment option. The recommended dose is 2–3 mg/kg on alternate days; 4–7 injections in total (Lopes et al., 2013; Sundar and Chakravarty, 2010).

Most of analyzed studies used intralesional or systemic antimony compounds as first choice. Amphotericin B was the choice when antimonials were not available and when the patient did not respond to the first choice of treatment (Kiafar et al., 2013; Nicodemo et al., 2012; Pulimood et al., 2012).

InDouba et al. (2012), cryotherapy was selected when the lesions were single or few in number, small in size and usually of the papulonodular type. This option was also the treatment of choice in pregnant women. Cryotherapy using liquid nitrogen was used once weekly for 4 weeks. In Škoberne and Žgavec (2012), treatment was limited to surgical excision of the lesion.

Poeppl et al. (2011)have reported a case of imported CL that was successfully treated with miltefosine, and which revealed a hitherto undescribed strain of the L. donovani/infantum complex during the follow-up investigation. Miltefosine is a new oral anti-leishmanial drug that interacts withLeishmaniaphospholipid synthesis. It is successfully used for the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis and is characterized by a favorable side-effect profile (García-Almagro, 2005).

InVasudevan and Bahal (2011), the patient responded to treatment with a combination of oral ketoconazole and intralesional sodium stibogluconate. The patient was treated with intralesional sodium stibogluconate once a week for 4 weeks, and tablet ketoconazole 400 mg once daily for the same duration.

Finally, to elucidate possible side effects of the treatment,Eryilmaz et al. (2010)reported thefirst case of pericarditis occurring as a result of the treatment with meglumine antimoniate. Pericarditis developed 3 days after the end of therapy. It was thought to be related to meglumine antimoniate therapy because history, physical examination, and ECG changes of the patient were compatible with acute pericardi-tis. Based on this, patients who have taken antimony compounds should be followed up for ECG changes after the end of treatment.

5. Conclusions

Atypical lesions of tegumentary leishmaniasis have been reported in the majority of endemic countries. Patients’age and gender seem to have no relation with the course or type of the lesions. Atypical lesions demonstrated aspects such as lupoid, eczematous, erysipeloid, verru-cous, dry, zosteriform, paronychial, sporotrichoid, chancriform, annu-lar and erythematous volcanic ulcer. Some cases have shown features similar to subcutaneous and deep mycosis, and malignancies such as lymphoma, pseudolymphoma, basal and squamous cell carcinomas. The lesions were found in the face, cheeks, ears, nose, eyelid, limbs, trunk, buttocks, as well as in palmoplantar and genital regions; some-times occurring in more than one area. The clinical presentation of these lesions can mimic several other disorders confounding the physicians, which may delay or hinder the precise diagnosis, submitting the patients to unnecessary treatments, worsening the picture, and contributing to the transmission chain of agent. The reason for clinical cutaneous leishmaniasis pleomorphism is still unclear, but variations in parasite virulence and host factors, including abnormal host immune response, malnutrition, immunosuppression, and aging have been postulated to affect the presentation. It has also been stated that co-infection with HIV, which along with malnutrition, is a very important cause of worsening of leishmaniasis with atypical clinical presentation and occurrence of reactivated lesions of CL. Pentavalent antimonials remain asfirst line treatment for all forms of leishmaniasis even for HIV-patients and atypical forms. Besides the common agents, L. infantumwas also implicated in some CL cases in the old world, notably in Europe.

In summary, to diagnose an atypical lesion properly, the focus has to be on the medical history and the origin of the patient, comparing them to the natural history of leishmaniasis and always remembering of possible atypical presentations, to then start searching for the best diagnostic method and the best treatment, decreasing the misdiagnosis rate and controlling the disease progress. Therefore, contributing for breaking the chain of transmission due to early correct diagnosis which, in turn, contributes to reduce the prevalence.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel, Ministry of Education of Brazil (CAPES/ MEC).

References

Škoberne, A.,Žgavec, B., 2012. An unusual manifestation of a neglected disease. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 21, 43–44.

Adriano, A.L., Leal, P.A., Breckenfeld, M.P., Costa, I.o.S., Almeida, C., Sousa, A.R., 2013. American tegumentary leishmaniasis: an uncommon clinical and histopathological presentation. An. Bras. Dermatol. 88, 260–262.

Aguado, M., Espinosa, P., Romero-Maté, A., Tardío, J.C., Córdoba, S., Borbujo, J., 2013. Outbreak of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Fuenlabrada, Madrid. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 104, 334–342.

Akilov, O.E., Khachemoune, A., Hasan, T., 2007. Clinical manifestations and classification of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int. J. Dermatol. 46, 132–142.

Alhumidi, A.A., 2013. Skin pseudolymphoma caused by cutaneous leismaniasia. Saudi Med. J. 34, 537–538.

Alvar, J., Aparicio, P., Aseffa, A., Den Boer, M., Cañavate, C., Dedet, J.P., Gradoni, L., Ter Horst, R., López-Vélez, R., Moreno, J., 2008. The relationship between leishmaniasis and AIDS: the second 10 years. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 21, 334–359 table of contents.

C.B. Meireles et al. Acta Tropica 172 (2017) 240–254

Ayatollahi, J., Ayatollahi, A., Shahcheraghi, S.H., 2013. Cutaneous leishmaniasis of the eyelid: a case report. Case Rep. Infect. Dis. 2013, 214297.

Ayatollahi, J., Fattahi Bafghi, A., Shahcheraghi, S.H., 2014. Rare variants of cutaneous leishmaniasis presenting as eczematous lesions. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 28, 71. Ayatollahi, J., Bafghi, A.F., Shahcheraghi, S.H., 2015. Chronic zoster-form: a rare variant

of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Rev. Med. Microbiol. 26, 114–115.

Bailey, M.S., Lockwood, D.N., 2007. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Clin. Dermatol. 25, 203–211.

Bari, A.U., Rahman, S.B., 2008. Many faces of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 74, 23–27.

Benítez, M.D., Miranda, C., Navarro, J.M., Morillas, F., Martín, J., de la Rosa, M., 2001. Thirty-six year old male patient with dysphonia refractory to conventional medical treatment. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 19, 233–234.

Bodet, E., Andreu, L., Giner, A.R., Fortuny, J.C., Palomar, V., 2002. Laryngeal leishmaniasis: report of two cases. ORL-DIPS 29, 131–134.

Castellano, L.R., Filho, D.C., Argiro, L., Dessein, H., Prata, A., Dessein, A., Rodrigues, V., 2009. Th1/Th2 immune responses are associated with active cutaneous leishmaniasis and clinical cure is associated with strong interferon-gamma production. Hum. Immunol. 70, 383–390.

Ceyhan, A.M., Yildirim, M., Basak, P.Y., Akkaya, V.B., Erturan, I., 2008. A case of erysipeloid cutaneous leishmaniasis: atypical and unusual clinical variant. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 78, 406–408.

Chiheb, S., Oudrhiri, L., Zouhair, K., Soussi Abdallaoui, M., Riyad, M., Benchikhi, H., 2012. Unusual clinical presentation of cutaneous leishmaniasis in three diabetic patients. Ann. Dermatol. Venereol. 139, 542–545.

Dassoni, F., Abebe, Z., Naafs, B., Morrone, A., 2013. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis resembling borderline-tuberculoid leprosy: a new clinical presentation? Acta Derm. Venereol. 93, 74–77.

David, C.V., Craft, N., 2009. Cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Dermatol. Ther. 22, 491–502.

Douba, M.D., Abbas, O., Wali, A., Nassany, J., Aouf, A., Tibbi, M.S., Kibbi, A.G., Kurban, M., 2012. Chronic cutaneous leishmaniasis, a great mimicker with various clinical presentations: 12 years experience from Aleppo. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 26, 1224–1229.

Doudi, M., Setorki, M., Narimani, M., 2012. Bacterial superinfection in zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis. Med. Sci. Monit. 18, BR356–361.

Eryilmaz, A., Durdu, M., Baba, M., Bal, N., Yiğit, F., 2010. A case with two unusual findings: cutaneous leishmaniasis presenting as panniculitis and pericarditis after antimony therapy. Int. J. Dermatol. 49, 295–297.

Faber, W.R., Oskam, L., van Gool, T., Kroon, N.C., Knegt-Junk, K.J., Hofwegen, H., van der Wal, A.C., Kager, P.A., 2003. Value of diagnostic techniques for cutaneous leishmaniasis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 49, 70–74.

Faucher, B., Pomares, C., Fourcade, S., Benyamine, A., Marty, P., Pratlong, L., Faraut, F., Mary, C., Piarroux, R., Dedet, J.P., Pratlong, F., 2011. Mucosal Leishmania infantum leishmaniasis: specific pattern in a multicentre survey and historical cases. J. Infect. 63, 76–82.

García-Almagro, D., 2005. Cutaneous leishmaniasis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 96, 1–24. González, U., Pinart, M., Reveiz, L., Alvar, J., 2008. Interventions for old world cutaneous

leishmaniasis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. C D005067.

González-Anglada, M.I., Peña, J.M., Barbado, F.J., González, J.J., Redondo, C., Galera, C., Nistal, M., Vázquez, J.J., 1994. Two cases of laryngeal leishmaniasis in patients infected with HIV. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 13, 509–511.

Guddo, F., Gallo, E., Cillari, E., La Rocca, A.M., Moceo, P., Leslie, K., Colby, T., Rizzo, A.G., 2005. Detection of Leishmania infantum kinetoplast DNA in laryngeal tissue from an immunocompetent patient. Hum. Pathol. 36, 1140–1142.

Habibzadeh, F., Sajedianfard, J., Yadollahie, M., 2005. Isolated lingual leishmaniasis. J. Postgrad. Med. 51, 218–219.

Hajjaran, H., Mohebali, M., Akhavan, A.A., Taheri, A., Barikbin, B., Soheila Nassiri, S., 2013. Unusual presentation of disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania major: case reports of four Iranian patients. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 6, 333–336.

Hepburn, N.C., 2003. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: an overview. J. Postgrad. Med. 49, 50–54. Iftikhar, N., Bari, I., Ejaz, A., 2003. Rare variants of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: whitlow,

paronychia, and sporotrichoid. Int. J. Dermatol. 42, 807–809.

Jafari, S., Hajiabdolbaghi, M., Mohebali, M., Hajjaran, H., Hashemian, H., 2010. Disseminated leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania tropica in HIV-positive patients in the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr. Health J. 16, 340–343.

Kafaie, P., Akaberi, A.A., Amini, S., Noorbala, M.T., Moghimi, M., 2010. Multidermatomal zosteriform lupoid cutaneous leishmaniasis: a case report. J. Pak. Assoc. Dermatol. 20, 243–245.

Karami, M., Doudi, M., Setorki, M., 2013. Assessing epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Isfahan, Iran. J. Vector Borne Dis. 50, 30–37.

Lopes, L., Vasconcelos, P., Borges-Costa, J., Soares-Almeida, L., Campino, L., Filipe, P., 2013. An atypical case of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum in Portugal. Dermatol. Online J. 19, 20407.

Masmoudi, A., Ayadi, N., Boudaya, S., Meziou, T.J., Mseddi, M., Marrekchi, S., Bouassida, S., Turki, H., Zahaf, A., 2007. Clinical polymorphysm of cutaneous leishmaniasis in centre and south of Tunisia. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 100, 36–40.

Miller, D.D., Gilchrest, B.A., Garg, A., Goldberg, L.J., Bhawan, J., 2012. Acute New World cutaneous leishmaniasis presenting as tuberculoid granulomatous dermatitis. J. Cutan. Pathol. 39, 361–365.

Mnejja, M., Hammami, B., Chakroun, A., Achour, I., Charfeddine, I., Turki, H., Ghorbel, A., 2011. Unusual form of cutaneous leishmaniasis: erysipeloid form. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 128, 95–97.

Momeni, A.Z., Aminjavaheri, M., 1994. Clinical picture of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Isfahan, Iran. Int. J. Dermatol. 33, 260–265.

Moravvej, H., Barzegar, M., Nasiri, S., Abolhasani, E., Mohebali, M., 2013. Cutaneous leishmaniasis with unusual clinical and histological presentation: report of four cases. Acta Med. Iran. 51, 274–278.

Murray, H.W., Berman, J.D., Davies, C.R., Saravia, N.G., 2005. Advances in leishmaniasis. Lancet 366, 1561–1577.

Nasiri, S., Mozafari, N., Abdollahimajd, F., 2012. Unusual presentation of cutaneous leishmaniasis: lower lip ulcer. Arch. Clin. Infect. Dis. 7, 66–68.

Neitzke-Abreu, H.C., Venazzi, M.S., de Lima Scodro, R.B., Zanzarini, P.D., da Silva Fernandes, A.C., Aristides, S.M., Silveira, T.G., Lonardoni, M.V., 2014. Cutaneous leishmaniasis with atypical clinical manifestations: case report. IDCases 1, 60–62. Neves, D.B., Caldas, E.D., Sampaio, R.N., 2009. Antimony in plasma and skin of patients

with cutaneous leishmaniasis–relationship with side effects after treatment with meglumine antimoniate. Trop. Med. Int. Health 14, 1515–1522.

Nicodemo, A.C., Amato, V.S., Miranda, A.M., Floeter-Winter, L.M., Zampieri, R.A., Fernades, E.R., Duarte, M.I., 2012. Are the severe injuries of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by an exacerbated Th1 response? Parasite Immunol. 34, 440–443. Oryan, A., Shirian, S., Tabandeh, M.R., Hatam, G.R., Randau, G., Daneshbod, Y., 2013.

Genetic diversity of Leishmania major strains isolated from different clinical forms of cutaneous leishmaniasis in southern Iran based on minicircle kDNA. Infect. Genet. Evol. 19, 226–231.

Ozdemir, M., Cimen, K., Mevlitoğlu, I., 2007. Post-traumatic erysipeloid cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int. J. Dermatol. 46, 1292–1293.

Pellicioli, A.C., Martins, M.A., Sant'ana Filho, M., Rados, P.V., Martins, M.D., 2012. Leishmaniasis with oral mucosa involvement. Gerodontology 29, e1168–1171. Piscopo, T.V., Mallia Azzopardi, C., 2007. Leishmaniasis. Postgrad. Med. J. 83, 649–657. Poeppl, W., Walochnik, J., Pustelnik, T., Auer, H., Mooseder, G., 2011. Cutaneous

leishmaniasis after travel to Cyprus and successful treatment with miltefosine. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 84, 562–565.

Pulimood, S.A., Rupali, P., Ajjampur, S.S., Thomas, M., Mehrotra, S., Sundar, S., 2012. Atypical mucocutaneous involvement with Leishmania donovani. Natl. Med. J. India 25, 148–150.

Raja, K.M., Khan, A.A., Hameed, A., Rahman, S.B., 1998. Unusual clinical variants of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Pakistan. Br. J. Dermatol. 139, 111–113.

Ramot, Y., Nanova, K., Alper-Pinus, R., Zlotogorski, A., 2014. Zosteriform cutaneous leishmaniasis diagnosed with the help of dermoscopy. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 4, 55–57.

Rassi, Y., Abai, M.R., Javadian, E., Rafizadeh, S., Imamian, H., Mohebali, M., Fateh, M., Hajjaran, H., Ismaili, K., 2008. Molecular data on vectors and reservoir hosts of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in central Iran. Bull. Soc. Pathol. Exot. 101, 425–428.

Robati, R.M., Qeisari, M., Saeedi, M., Karimi, M., 2011. Auricular enlargement: an atypical presentation of old world cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J. Dermatol. 56, 428–429.

Rosatelli, J.B., Souza, C.S., Soares, F.A., Foss, N.T., Roselino, A.M., 1998. Generalized cutaneous leishmaniasis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 10, 229–232.

Saab, J., Fedda, F., Khattab, R., Yahya, L., Loya, A., Satti, M., Kibbi, A.G., Houreih, M.A., Raslan, W., El-Sabban, M., Khalifeh, I., 2012. Cutaneous leishmaniasis mimicking inflammatory and neoplastic processes: a clinical, histopathological and molecular study of 57 cases. J. Cutan. Pathol. 39, 251–262.

Salmanpour, R., Handjani, F., Zerehsaz, F., Ardehali, S., Panjehshahin, M.R., 1999. Erysipeloid leishmaniasis: an unusual clinical presentation. Eur. J. Dermatol. 9, 458–459.

Shah, S., Shah, A., Prajapati, S., Bilimoria, F., 2010. Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in HIV-positive patients: a study of two cases. Indian J. Sex. Transm. Dis. 31, 42–44. Sharquie, K.E., Hameed, A.F., 2012. Panniculitis is an important feature of cutaneous

leishmaniasis pathology. Case Rep. Dermatol. Med. 2012, 612434.

Sharquie, K.E., Najim, R.A., 2004. Disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis. Saudi Med. J. 25, 951–954.

Siah, T.W., Lavender, T., Charlton, F., Wahie, S., Schwab, U., 2014. An unusual erysipelas-like presentation. Dermatol. Online J. 20, 21255.

Sindhu, P.S., Ramesh, V., 2012. Unusual presentation of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J. Dermatol. 57, 55–57.

Soares-Bezerra, R.J., Leon, L., Genestra, M., 2004. Recent advances on leishmaniasis chemotherapy: intracelular molecules as a drug target. Revista Brasileira de Ciencias Farmaceuticas/Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 40, 139–149.

Soni, P., Prasad, N., Khandelwal, K., Ghiya, B.C., Mehta, R.D., Bumb, R.A., Salotra, P., 2011. Unresponsive cutaneous leishmaniasis and HIV co-infection: report of three cases. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 77.

Sundar, S., Chakravarty, J., 2010. Antimony toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 7, 4267–4277.

Talat, H., Attarwala, S., Saleem, M., 2014. Cutaneous leishmaniasis with HIV. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 24 (Suppl 2), S93–95.

Teemul, T.A., Giles-Lima, M., Williams, J., Lester, S.E., 2013. Laryngeal leishmaniasis: case report of a rare infection. Head Neck 35, E277–279.

Tiseo, D., Tosone, G., Conte, M.C., Scordino, F., Mansueto, G., Mesolella, M., Parrella, G., Pennone, R., Orlando, R., 2008. Isolated laryngeal leishmaniasis in an

immunocompetent patient: a case report. Infez. Med. 16, 233–235. Vasudevan, B., Bahal, A., 2011. Leishmaniasis of the lip diagnosed by lymph node

aspiration and treated with a combination of oral ketaconazole and intralesional sodium stibogluconate. Indian J. Dermatol. 56, 214–216.

Ziaie, H., Sadeghian, G., 2008. Isolation of bacteria causing secondary bacterial infection in the lesions of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Indian J. Dermatol. 53, 129–131. da Silva, G.A., Sugui, D., Nunes, R.F., de Azevedo, K., de Azevedo, M., Marques, A.,

Martins, C., Ferry, F.R., 2014. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis/HIV coinfection presented as a diffuse desquamative rash. Case Rep. Infect. Dis. 2014, 293761.

C.B. Meireles et al. Acta Tropica 172 (2017) 240–254

de Brito, M.E., Andrade, M.S., Dantas-Torres, F., Rodrigues, E.H., Cavalcanti, M.e.P., de Almeida, A.M., Brandão-Filho, S.P., 2012. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in northeastern Brazil: a critical appraisal of studies conducted in State of Pernambuco. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 45, 425–429.

del Giudice, P., Marty, P., Lacour, J.P., Perrin, C., Pratlong, F., Haas, H., Dellamonica, P., Le Fichoux, Y., 1998. Cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania infantum: case reports and literature review. Arch. Dermatol. 134, 193–198.

C.B. Meireles et al. Acta Tropica 172 (2017) 240–254