www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Circulating

endothelial

progenitor

cells

in

obese

children

and

adolescents

夽

,

夽夽

António

Pires

a,∗,

Paula

Martins

a,

Artur

Paiva

b,

Ana

Margarida

Pereira

c,

Margarida

Marques

d,

Eduardo

Castela

a,

Cristina

Sena

c,

Raquel

Seic

¸a

caServiceofPediatricCardiology,HospitalPediátricodeCoimbra,CentroHospitalareUniversitáriodeCoimbra(CHUC),Coimbra,

Portugal

bInstitutoPortuguêsdoSangueeTransplantac¸ão,Coimbra,Portugal

cLaboratóriodeFisiologia,InstitutodeImagemBiomédicaeCiênciasdaVida,FaculdadedeMedicina,UniversidadedeCoimbra,

Coimbra,Portugal

dLaboratóriodeEstatística,FaculdadedeMedicina,UniversidadedeCoimbra,InstitutodeImagemBiomédicaeCiênciasdaVida,

Coimbra,Portugal

Received1October2014;accepted13January2015 Availableonline29August2015

KEYWORDS

Pediatricobesity; C-reactiveprotein; Monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1; E-selectin; Asymmetric dimethylarginine; Endothelial progenitorcells

Abstract

Objective: Thisstudy aimed toinvestigate therelationship between circulating endothelial

progenitorcellcountandendothelialactivationinapediatricpopulationwithobesity.

Methods: Observational and transversal study, including120 children andadolescents with

primary obesityofbothsexes, aged6---17 years,whowere recruitedatthis Cardiovascular

RiskClinic.Thecontrolgroupwasmadeupof41childrenandadolescentswithnormalbody

massindex.Thevariablesanalyzedwere:age,gender,bodymassindex,systolicanddiastolic

bloodpressure,high-sensitivityC-reactiveprotein,lipidprofile,leptin,adiponectin,

homeo-stasismodelassessment-insulinresistance,monocytechemoattractantprotein-1,E-selectin,

asymmetricdimethylarginineandcirculatingprogenitorendothelialcellcount.

夽 Pleasecitethisarticleas:PiresA,MartinsP,PaivaA,PereiraAM,MarquesM,CastelaE,etal.Circulatingendothelialprogenitorcellsin obesechildrenandadolescents.JPediatr(RioJ).2015;91:560---6.

夽夽StudylinkedtotheHospitalPediátrico,CentroHospitalareUniversitáriodeCoimbra(CHUC);LaboratóriodeFisiologiaandLaboratório deEstatística,InstitutodeImagemBiomédicaeCiênciasdaVida,FaculdadedeMedicina,UniversidadedeCoimbra;andtotheInstituto PortuguêsdoSangueeTransplantac¸ão,Coimbra,Portugal.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:pires1961@gmail.com(A.Pires). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2015.01.011

Results: Insulinresistancewascorrelatedtoasymmetricdimethylarginine(=0.340;p=0.003),

which was directly,but weakly correlated toE-selectin (=0.252;p=0.046).High

sensitiv-ity C-reactiveprotein wasnot foundto becorrelated tomarkersofendothelial activation.

Systolicbloodpressurewasdirectlycorrelated tobody massindex(=0.471;p<0.001)and

thehomeostasismodelassessment-insulinresistance(=0.230;p=0.012),andinversely

corre-latedtoadiponectin(=−0.331;p<0.001)andhigh-densitylipoproteincholesterol(=−0.319;

p<0.001).Circulatingendothelialprogenitorcellcountwasdirectly,butweaklycorrelated,to

bodymassindex(r=0.211;p=0.016),leptin(=0.245;p=0.006),triglyceridelevels(r=0.241;

p=0.031),andE-selectin(=0.297;p=0.004).

Conclusion: Circulatingendothelialprogenitorcellcountiselevatedinobesechildrenand

ado-lescentswithevidenceofendothelialactivation,suggestingthat,duringinfancy,endothelial

repairingmechanismsarepresentinthecontextofendothelialactivation.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Obesidadeinfantil; ProteínaCreativa; Proteínaquimiotática demonócitos-1; E-seleticna; Dimetilarginina assimétrica; Célulasprogenitoras endoteliais

Célulasprogenitorasendoteliaiscirculantesemcrianc¸aseadolescentesobesos

Resumo

Objetivo: Oobjetivodesteestudofoi investigararelac¸ãoentreosnúmerosdecélulas

pro-genitoras endoteliaiscirculantese aativac¸ãoendotelial em uma populac¸ãopediátrica com

obesidade.

Métodos: Estudoobservacionaletransversal,incluindo120crianc¸aseadolescentescom

obesi-dadeprimáriadeambosdesexos,comidadesentre6e17anos,recrutadosdenossaClínica

deRiscosCardiovasculares.Ogrupodecontrolecontoucom41crianc¸aseadolescentescom

índicedemassacorporalnormal.Asvariáveisanalisadasforam:idade,sexo,índicedemassa

corporal,pressãoarterialsistólicaediastólica,proteínaCreativadealtasensibilidade,perfil

lipídico,leptina,adiponectina,resistênciaàinsulinaparaavaliac¸ãodomodelodehomeostase,

proteínaquimiotáticademonócitos-1,E-seleticna,dimetilargininaassimétricaenúmerosde

célulasendoteliaisprogenitorascirculantes.

Resultados: Aresistênciaàinsulinafoicorrelacionadaadimetilargininaassimétrica(p=0,340;

p=0,003),que foidiretamentecorrelacionada, porém deformamuitaamena àE-seleticna

(=0,252; p=0,046). Nãoconstatamos quea proteína C reativa de alta sensibilidade está

correlacionada amarcadores de ativac¸ãoendotelial. A pressãoarterial sistólicafoi

direta-mentecorrelacionadaaoíndicedemassacorporal=0,471;p<0,001)eàresistênciaàinsulina

paraavaliac¸ãodomodelodehomeostase(=0,230;p=0,012)einversamentecorrelacionada

a adiponectina(=-0,331; p<0,001)e lipoproteína de alta densidade-colesterol =-0,319;

p<0,001).Osnúmerosdecélulasprogenitorasendoteliaiscirculantesforamdiretamente

cor-relacionados,porémdeformamuitoamenaaoíndicedemassacorporal(r=0,211;p=0,016),

àleptina(=0,245;p=0,006),aosníveisdetriglicerídeos(r=0,241;p=0,031)eàE-seleticna

=0,297;p=0,004).

Conclusão: Osnúmerosdecélulasprogenitorasendoteliaiscirculantessãoelevadosemcrianc¸as

eadolescentesobesoscomcomprovac¸ãodeativac¸ãoendotelial,sugerindoque,nainfância,os

mecanismosdereparac¸ãoendotelialestãopresentesnocontextodaativac¸ãoendotelial.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todososdireitos

reservados.

Introduction

Inobesity,variousinflammatoryagents,suchasC-reactive protein1---3andleptin,4disturbtheproductionofnitricoxide

via the inhibition of its rate-limitingenzyme, endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS).5,6 Other endogenous

sub-stances, such as asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), a competitive antagonist of eNOS, also play a role in fur-thercompromisingnitricoxidebioavailability.Itsproduction is stimulated by inflammatory agents, such as C-reactive

protein.7 Unlike nitricoxide,it canbe easilyassayed and

usedasasurrogatefornitricoxidebioavailability.

Inpatientswithcardiovascularriskfactors,suchas arte-rial hypertension and insulin resistance, the count and function of EPCs is reduced. In these, the risk of cardio-vasculareventsisincreased.9,10

Inflammatorymarkersalsoappearstoreducethenumber ofEPCs,implyingapossibleroleinobesity.11,12

The aims of the present study were two fold. Firstly, to demonstrate that endothelial activation is present in childhoodobesity;andsecondly,thatrepairingmechanisms, throughEPCactivation,arenot,atthisearlystage, compro-mised.

Methods

Subjects

The authors conducted an observational and transversal analysis, in a cohort of obese children and adolescents, recruitedrandomly,andfollowed-upataCardiovascularRisk Clinic.Allparentsgavetheirinformedconsentforthe chil-drentoparticipateinthestudy,whichhadbeenapproved bythelocalEthicsCommittee.

Theinclusioncriteriaforthestudy groupwereprimary obesity(bodymassindex[BMI]abovethe95thpercentilefor sexandage)inchildrenandadolescentsaged6---17years, withoutrecent or chronic illnesses.The exclusion criteria included secondary causes of obesity,acute infectious or inflammatorydisorders(within amonth of sampling),and chronicdisorders.

Thecontrolgroupincludedhealthychildrenand adoles-cents,unrelated tothe studygroup, withinthe sameage rangewitha normal BMI(percentil 5---85), recruited from theCardiologyClinicwheretheyweresentforevaluationof murmurs,butprovedtohavenosubjacentcardiac anoma-lies. All had undergone a 12-h fast prior to the clinical evaluationandbloodsampling.

The study group comprised 120 and the control group 41children andadolescents,of both sexes. Basedonthis samplesize,asignificancelevel(p-value)of0.05,apower of 0.80,and an effect size of 0.52were obtained. These valueswerecalculatedusingtheG*Power3.1.5program.

The variables analyzed were: age, gender, body mass index,systolicbloodpressure,diastolicbloodpressure,total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglycerides, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), lipid profile, leptin, adiponectin, homeostasis model assessment-insulin resis-tance(HOMA-IR),E-selectin,asymmetricdimethylarginine, andcirculatingEPCcount.

Clinicalandanthropometricevaluation

Weight(inkilogramstothenearest100g)wasdetermined usingaSECA220® digitalweightscale(MedicalScalesand Measuring Systems, Hamburg, Germany) and for standing height(incentimeterstothenearest0.1cm)astadiometer includedinthesameequipmentwasused,withthechildren wearingonly undergarments. Body mass indexwas calcu-lated basedon the formula:BMI=(weight/height2).13 The

WorldHealthOrganization(WHO)BMIpercentilechartswere

usetodefineobesity(ifBMI>percentil95;normalweight: BMIbetweenpercentil5---85).

The criteria for metabolic syndrome in children and adolescentsweredefinedaccordingtotheInternational Dia-betesFederationconcensus.14

Bloodcollectionandbiochemicalanalysis

Fastingvenousbloodsamples(15mL)wereobtainedto esti-matethehematologicalparameters.Bloodspecimenswere collected in vacutainertubes withor without ethylenedi-aminetetraaceticacid(EDTA)asneeded.Serumandplasma were preparedand then frozen (−80◦C)for storage until

analysis. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein was deter-mined by immunonephelometry from serum samples and processedintheBNProSpec® System(SiemensHealthcare DiagnosticsInc,Munich,Germany)analyzer(undetectedif <0.02mg/dL).

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, asymmetric dimethylarginineandE-selectinweredeterminedbyELISA using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosor-bent assaykits OptEIATM (BD BiosciencesPharmingen, CA, USA).

Leptin and adiponectin levels were determined using commerciallyavailableenzyme-linkedimmunosorbentassay kits(eBioscience--- SanDiego,CA,UnitedStatesand BioVen-dor--- Brno,CzechRepublic,respectively).

Insulin levels were determined by chemiluminescence fromserumsamplesandprocessedintheIMMULITE2000® (SiemensHealthcareDiagnosticsInc,Munich,Germany) ana-lyzer and glucose levels were determined from plasma samplesanalyzedintheVITROS5.1FS®(OrthoClinical Diag-nostics,Johnson&Johnson,NY,USA)systembymicroslide technology.

The HOMA-IR was calculated based on the formula; HOMA-IR=insulin(mU/L)×glucose(mmol/L)/22.5, consid-ering 3 as the cut-off value for the diagnosis of insulin resistance.15

Total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C),high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C),and triglyceride (TG) concentrations were measured using an automatedbiochemicalanalyzerVITROS5.1FS®(Ortho

Clin-icalDiagnostics,Johnson&Johnson,NY,USA).

Fordeterminationof circulating EPC count,peripheral blood (PB) was collected in EDTA tubes, stored on ice, and processed within2h. Identification and characteriza-tionofcirculatingEPCwasperformedusingananti-CD146 conjugated withflouresceinisothiocyanate(clone:P1H12, BectonDickinson(BD),CA,USA),anti-KDRconjugatedwith phycoeritrin (clone: 89106, R&D System, Headquarters, Minneapolis, USA), anti-CD34 peridinin chlorophyll pro-tein cyanine 5.5 (clone: 8G12, BD Bioscience, CA, USA), anti-CD133allophycocyanin(clone:293C3,MiltenyiBiotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), and CD45 krome orange (clone: J.33, Immunotech --- Beckman Coulter, Marseille, France)combinationofmonoclonalantibodies(mAb).

Forsamplestaining,adirectimmunofluorescence tech-nique was used. Data acquisition was performed in a FACSCantoII® flowcytometer(BDBiosciencesPharmingen,

CA, USA) using the FACSDiva® software (BD Biosciences

International Society for Hematotherapy and Graft Engi-neering (ISHAGE) sequential gating strategy proposed by Schmidt---Luckewasfollowed.

CirculatingEPCSwereidentifiedaccordingtoaminimal antigenicprofilethatincludesatleastonemarkerof stem-ness/immaturity(CD34andCD133),plusatleastonemarker ofendothelialcommitment(KDRandCD146).CD45staining wasusedtoexcludeleukocytes.

Fordataanalysis,theInfinicytTMsoftware,V.1.5

(Cytog-nosSL,Salamanca,Spain)wasused.

Statisticalanalysis

ThedatawasanalyzedusingtheIBMSPSS20software(IBM Corp.Released 2011.IBM SPSSStatisticsfor Windows,NY, USA).The descriptiveanalysisof theparametric variables wasdone bycalculating themean±standard error of the mean.Student’st-testandMann---WhitneyUtestwereused tocalculate thedifferences in the demographic,clinical, andhematologicalparametersbetweentheobeseand con-trolgroups,dependingonthenormalityofdistribution.For categoricalresponsevariables,differencesbetweenthetwo groups were assessed using the chi-squared test. Logistic regression was used when clinical variables were con-trolledbetweenthetwogroups.Toestablishthecorrelation betweentheparametersintheobesegroup,Spearman’sand Pearsons’scorrelationswereused.Theresultswere consid-eredstatisticallysignificantatp<0.05.

Results

Comparativeanalysisbetweentheobeseand controlgroups

Onehundredandtwentyobesechildrenandadolescents,61 boysand59girls,withagesbetween6and17years(mean age11.65years±2.96)wereincludedinthestudy.The con-trolgroup wasmade upof41 healthy,non-obesechildren andadolescents,29boysand12girls,withinthesameage group(meanage12.73years±2.77).

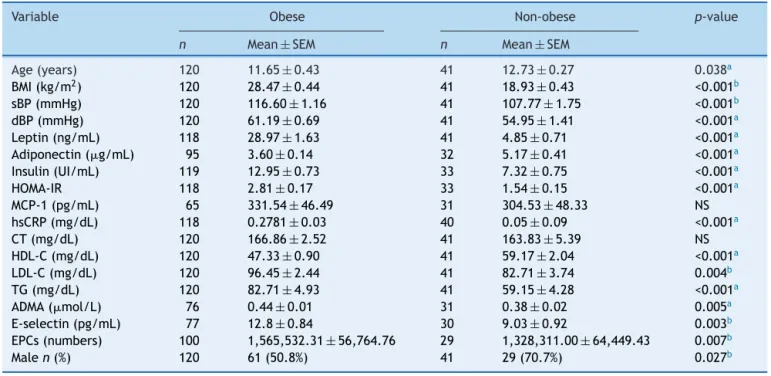

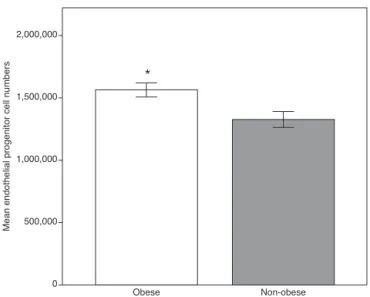

We firstly compared the two group’s anthropometric, clinical and analytical parameters. As demonstrated in

Table1,allthemeansoftheanalyzedparameterswere sig-nificantlyhigher in the obese group,including E-selectin, ADMAandcirculatingEPCS,exceptforadiponectinand HDL-C(Fig.1).Totalcholesterolandmonocytechemoattractant protein-1showednosignificantstatisticaldifferences.

As age (p=0.038) and gender (p=0.027) were signif-icantly different between the two groups, the analysis wasrepeatedusinglogisticregression,andtheresultsdid not differ significantly, namely, MCP-1 (p=0.334), ADMA (p=0.005),E-selectin(p=0.008),andEPCs(p=0.043).Total cholesterolandMCP-1continuedtoshownosignificant dif-ferences.

Circulating EPCcount were directly,but weakly corre-lated,toBMI(r=0.21;p=0.016),leptin(=0.25;p=0.006),

triglyceride levels (r=0.24; p=0.031), and E-selectin (=0.30;p=0.004).

Table1 Anthropometric,clinical,andanalyticalparametersoftheobeseandnon-obesegroups.

Variable Obese Non-obese p-value

n Mean±SEM n Mean±SEM

Age(years) 120 11.65±0.43 41 12.73±0.27 0.038a

BMI(kg/m2) 120 28.47±0.44 41 18.93±0.43 <0.001b

sBP(mmHg) 120 116.60±1.16 41 107.77±1.75 <0.001b

dBP(mmHg) 120 61.19±0.69 41 54.95±1.41 <0.001a

Leptin(ng/mL) 118 28.97±1.63 41 4.85±0.71 <0.001a

Adiponectin(g/mL) 95 3.60±0.14 32 5.17±0.41 <0.001a

Insulin(UI/mL) 119 12.95±0.73 33 7.32±0.75 <0.001a

HOMA-IR 118 2.81±0.17 33 1.54±0.15 <0.001a

MCP-1(pg/mL) 65 331.54±46.49 31 304.53±48.33 NS

hsCRP(mg/dL) 118 0.2781±0.03 40 0.05±0.09 <0.001a

CT(mg/dL) 120 166.86±2.52 41 163.83±5.39 NS

HDL-C(mg/dL) 120 47.33±0.90 41 59.17±2.04 <0.001a

LDL-C(mg/dL) 120 96.45±2.44 41 82.71±3.74 0.004b

TG(mg/dL) 120 82.71±4.93 41 59.15±4.28 <0.001a

ADMA(mol/L) 76 0.44±0.01 31 0.38±0.02 0.005a

E-selectin(pg/mL) 77 12.8±0.84 30 9.03±0.92 0.003b

EPCs(numbers) 100 1,565,532.31±56,764.76 29 1,328,311.00±64,449.43 0.007b

Malen(%) 120 61(50.8%) 41 29(70.7%) 0.027b

BMI, bodymassindex; sBP, systolicbloodpressure; dBP,diastolic blood pressure;HOMA-IR, homeostasismodel assessment-insulin resistance;MCP-1,monocytechemoattractantprotein-1;hsCRP,high-sensitivityC-reactiveprotein;CT,totalcholesterol;HDL-C,high densitylipoproteincholesterol;LDL-C,lowdensitylipoproteincholesterol;TG,triglycerides;ADMA,asymmetricdimethylarginine;EPCs, circulatingendothelialprogenitorcellcount;NS,non-significantp-value;n,samplenumber;SEM,standarderrorofthemean.

Obese 0

500,000 1,000,000

Mean endothelial progenitor cell numbers

1,500,000 2,000,000

*

Non-obese

Figure1 Endothelialprogenitorcellcountintheobeseand

thenon-obesegroups.Thehigherlevelsintheobesegroupmay

reflecttheresponsebyrepairingmechanismssecondarytoearly

endothelial activation. Data expressed as means±standard

error of the mean. Obese group, n=100; non-obese group,

n=29.*Student’st-test,p<0.01vs.nonobesegroup.

Analysisoftheobesegroup

Bodymassindexwasdirectlyandmoderatelycorrelatedto MCP-1(=0.51;p<0.001),systolicbloodpressure(=0.47;

p<0.001),leptin(=0.40;p<0.001),andHOMA-IR(=0.35;

p<0.001);weaklycorrelatedtohsCRP(=0.22;p=0.018); and inversely but weakly correlated to adiponectin (=−0.28;p=0.007)andHDL-C(=−0.26;p=0.004).

Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 was directly cor-related tosystolic blood pressure (=0.34; p=0.005), as shown in Fig. 2. High sensitivity C-reactive protein was

90.00 .000 500,000 1,000,000 1,500,000 2,000,000

R2 linear=0.099

100.00 110.00 120.00

sBP

MCP-1

130.00 140.00 150.00

Figure 2 Correlation between monocyte chemoattractant

protein-1andsystolicbloodpressure.Inobesity,cardiovascular

riskfactorsclusterandcontributetotheinflammatoryprocess,

asobservedinthecorrelationbetweensystolicbloodpressure

andMCP-1inthe presentstudy.sBP,systolic bloodpressure;

MCP-1,monocytechemoattractantprotein-1.

weaklycorrelatedtoleptin (=0.32;p<0.001) andLDL-C (=0.23;p=0.011).

Systolic blood pressure was inversely correlated to adiponectin (=−0.33; p=0.001) and directly correlated toHOMA-IR (=0.23;p=0.012) and,asexpected, moder-atelycorrelatedtoage(=0.50;p<0.001).Diastolicblood pressurehadlesspronouncedcorrelations.

TheHOMA-IRwascorrelatedtoADMA(=0.34;p=0.003) providing the most direct link to a marker of endothe-lial activation. This was evident particularly at HOMA-IR values above 3 (p=0.003), the cut-off value we used to define insulin resistance. It was also directly cor-related to leptin (=0.39; p<0.001), systolic blood pressure (=0.23;p<0.012), anddiastolic blood pressure (=0.20;p<0.033),andinverselycorrelatedtoadiponectin (r=−0.21;p=0.040).

Metabolic syndrome was observed in 11.7% (n=14) of the obese patients. As expected, being part of the definition,systolic(p=0.005),butnotdiastolicblood pres-sure (p=0.728), waselevated, aswere triglyceridelevels (p<0.001),HDL-Cwaslower(p=0.007),andnosignificant differenceswereobservedinglucoselevels.Regardingthe markers of endothelial activation andrepair mechanisms, ADMA was directly, but weakly correlated to E-selectin (=0.25; p=0.046),and thelatter wasweaklycorrelated tocirculatingEPCcount(=0.22;p=0.047).

Discussion

The present study clearly demonstrates that, unlike their lean counterparts, obese children and adolescents with evidence of ongoing low-grade inflammation and endothelialactivation haveraised EPCcount.Correlations between adiposity, inflammatory markers, and obesity-related comorbidities such as arterial hypertension and insulinresistancewerealsoobserved.

Monocytechemoattractantprotein-1regulatesmigration and infiltration of monocytes andmacrophages16 into the

vascularwallandplaysanimportantrolein inflammation-mediateddiseases,suchasobesity.17 Asscanttranslational

researchhasbeendoneinthisfield,theauthorswere inter-ested in evaluating the relationship of MCP-1 to obesity relatedcomorbidities.UnlikethefindingsbyBreslinetal.,18

nodifferenceswereobservedinMCP-1levelsbetweenthe obeseandcontrolgroupsnorwhatanassociationwith dys-lipidemia retrieved (data not shown), possibly due to a different sample size(39 obesechildren andadolescents) and ethnicity (American-Mexican). However, in the obese group, MCP-1,unlike hsCRP, hada directcorrelation with systolic blood pressure. This trend was not found in the controlgroup.Itis,thustemptingtopostulatethatin child-hood obesity,MCP-1 contributes to arterial hypertension, andimplicitlyisimplicatedinthepathophysiological mech-anismsleadingtocardiovasculardiseaselaterinlife.Based onthepresentevidence,MCP-1,comparedtohsCRP,would appeartobeamorerobustcardiovascularriskmarker. How-ever,duetothesamplesize,furtherresearchneedstobe done in thisfield.To thebestof theauthors’ knowledge, theseassociationshavenotbeenpreviouslydescribed.

highersystolicanddiastolicbloodpressurevalues(p<0.001) than thecontrol group.The prevalence of arterial hyper-tension in the obese group was9.2%, and almost a third had pre-hypertension (26.7%). Apart from MCP-1, and in agreementwiththefindingsbyMoseretal.,20systolicblood

pressurewasdirectlycorrelatedtoBMIandinverselyrelated to adiponectin and HDL-C. This cluster of mediators cor-relatesvisceraladiposity,inflammation,insulinresistance, andhypertension,someofthecomponentsofthemetabolic syndrome, found in 11.7% of the obese group. A particu-larinterestingfindingwastheinversecorrelationbetween adiponectin and arterial hypertension, thus corroborating the findings of the study by Brambilla et al.,21 in which

adiponectinwasproposedasoneofthemechanismsrelated tohypertensioninchildhoodobesity.This impliesthatthe lossofitsantiatherogenicandanti-inflammatoryproperties contributetotheunderlyingmechanismsofobesity-related hypertension.

Furthermore,thelossofadiponectin’sinsulinsensitizing properties that occurs in obesity has also been impli-cated in insulin resistance.22 Unlike the findings by Lee

etal.,23 whereadiponectinwasfoundtobeastrong

inde-pendent predictor of insulin sensitivity in obese children and adolescents of different racial backgrounds, in the present study adiponectinwas shown to becorrelated to hyperinsulinaemia(r=−0.23; p=0.033),butnot toinsulin resistance (n=38%; p=0.277), despite strikingdifferences inadiponectinlevelsbetweentheobeseandcontrolgroups (p<0.001).

The present study included only whitesubjectsfrom a differentgeographicalarea,which,togetherwiththe sam-ple size (n=45 with HOMA-IR >3), might account for the observeddifferences,although adiponectingene polymor-phisms might also play a role. This hypothesis is merely speculative,asitwasnottestedinthepresentstudy. How-ever, this rationale could not beapplied toleptin, which had a stronger correlation to hyperinsulinaemia (r=0.35;

p<0.001) and insulin resistance (p<0.001), findings in accordancewithpreviouslypublishedworks.24Aconnection

between MCP-1 (p=0.168), hsCRP (p=0.375), and insulin resistancewasnotobserved.

The authors further attempted to relate ADMA and E-selectin,bothmarkersofendothelialactivation,toinsulin resistance.Inadults,raisedlevelsofasymmetric dimethy-larginineareconsideredacardiovascularriskmarker,andas asurrogateofnitricoxidebioavailability,reflects endothe-lial integrity. A direct correlation between HOMA-IR and ADMA (r=0.35; p=0.003) was observed, particularly evi-dent intheinsulin-resistant group(p=0.003),findings not previously reported. Some reports have suggested that ADMAcontributestoinsulinresistance asdecreasednitric oxide bioavailability reduces blood flow to insulin sensi-tive tissues compromising glucose uptake in response to insulin.25Conversely,insulinresistanceitselfhasbeenfound

tocontributetowardendothelial dysfunction.Underthese circumstances, itis temptingtospeculate onADMA’s per-missive role on the interplay between insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction, through its actions onnitric oxide bioavailability. A direct correlation between leptin andADMAwasalsoobserved,butonly ingirls. Thisis not surprising,asleptinlevelsweresignificantlyhigherinobese girls (p<0.001). Nevertheless, this finding, not previously

reported,potentially links leptin, and henceadiposity, to endothelialactivation.Comparatively,linearregressionby logarithmic transformation showed that insulin resistance hadagreaterinfluenceonADMA.

E-selectin is a specific endothelial adhesion molecule whoselevelsareraisedinendothelialdysfunction, promot-ingthemigrationofinflammatorycellstotheintima.Inthis analysis,obese children andadolescents had significantly higherlevelsthanhealthycontrols, implyingthepresence ofendothelialactivation,whichindicatesanearlystageof atherosclerosis.Consideringtheentirecohort,adirect,but weakcorrelation tohsCRP (=0.21;p=0.033) wasfound,

reinforcing the role of inflammation in endothelial dys-functionandinagreementwithpublishedliterature,26 but

asimilar pattern wasnot demonstrated withinthe obese group,possiblydue toitshomogeneity.Wealsoobserved, withintheobesegroup,adirectcorrelationbetweenADMA and circulating EPC count. We found these correlations particularly interesting as they highlight various patho-physiological pathways related to endothelial activation, namely,inflammatorycelladhesiontriggeredbyE-selectin, increasedexpression of ADMA, whocompetitively inhibits eNOS,reducingnitricoxidebioavailabilityand,ultimately, repairofinjuredtissueby EPCS.The authorsbelievethat therelationshipbetweenE-selectinandADMA,inchildhood obesity,hasnotbeenpreviouslypublished.

Theterm EPCsshouldbereservedforaprogenitorcell restrictedspecifically totheendothelial lineage.In 1997, Asahara et al.27 reported for the first time on the

exist-enceof EPCs.To date,nospecific markerhasbeen found toclearlyidentifythesecells,whichmakestheirisolation controversial,astheiridentificationisbasedoncellsurface markersshared byother hematological celllines.As such variousmethodshavebeen usedtoidentifyEPCs.Inorder tominimizefalsepositivesvariouscellsurfacemarkershave beenintegratedtoidentifythesecells,namelythoselinked toimmaturecelllines(e.g.CD34)withendothelial commit-ment(e.g.kinaseinsertdomainreceptor).

Asreportedby variousauthors,thecountandfunction ofcirculatingEPCSnotonlycorrelateinverselywith cardio-vascularriskfactors,butalsomaypredicttheoccurrenceof cardiovascularevents,particularlyintheadultpopulation.28

Data regarding EPCs and childhood obesity is scarce. A reportbyJungetal.29observedadirectcorrelationto

E-selectin.Contrarytothepresentstudy,thiscorrelationonly appliedtoobeseadolescents.Inthepresentstudy,EPCsand E-selectin were directly correlated in the pre-adolescent obesegroup,afindingnotpreviouslyreportedandthat rein-forcesthefactthatendothelialdysfunctionispresentinvery youngindividuals.

Inthisanalysis,theobesegrouphadasignificantlyhigher numberofEPCs,implyingthatelevatedEPCsinobese chil-dren and adolescents represent an attempt at repairing underlyingvascular damage. Thus,at this stage,it would bepossibletoreversetheunderlyingendothelialdamageif stepsaretakentocontrolweight.

damage. The inference is that therapeutic interventions aimedatweightlossoughttobeaggressivelyinstitutedin order to reverse endothelial damage and obesity-related comorbidities, such as arterial hypertension and insulin resistance.

Thisstudyhasseverallimitations.Firstlyitssamplesize, particularlyitscontrolgroup.Italsoonlyincludeda white-onlypopulation,limitedtoaparticulargeographicalarea, theformerduetolocalracedistribution.Thestudyincluded bothgenders,aswellas,differentagegroups.Intheresults, these differences were adjusted for, and therefore their interferencewasnullified.

Conflict

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.Kapiotis S, Holzer G, Schaller G, Haumer M, Widhalm H, WeghuberD,et al.A proinflammatorystateis detectablein obese children and is accompanied by functional and mor-phological vascular changes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2541---6.

2.PasceriV,WillersonJT,YehET.Directproinflammatoryeffect ofC-reactiveproteinonhumanendothelialcells.Circulation. 2000;102:2165---8.

3.Soriano-Guilén L, Hernández-Garcia B, Pita J, Dominguez-Garrido N, Del Rio-Camacho G, Rovira A. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein is a good marker of cardiovascular risk in obese children and adolescents. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159:R1---4.

4.Braunersreuther V, Mach F, Steffens S. The specific role of chemokines in atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:714---21.

5.Montero D, Walther G, Perez-Martin A, Roche E, Vinet A. Endothelialdysfunction,inflammation,andoxidativestressin obesechildrenandadolescents:markersandeffectoflifestyle intervention.ObesRev.2012;13:441---55.

6.AvogaroA,deKreutzenbergSV.Mechanismsofendothelial dys-functioninobesity.ClinChimActa.2005;360:9---26.

7.vanderZwanLP,SchefferPG,DekkerJM,StehouwerCD,Heine RJ,TeerlinkT.Systemicinflammationislinkedtolowarginine andhighADMAplasmalevelsresultinginanunfavourableNOS substrate-to-inhibitor ratio:theHoornStudy. ClinSci(Lond). 2011;121:71---8.

8.YoderMC.Humanendothelialprogenitorcells.ColdSpringHarb PerspectMed.2012;2:a006692.

9.Müller-EhmsenJ,BraunD,SchneiderT,PfisterR,WormN, Wiel-ckensK,etal.Decreasednumberofcirculatingprogenitorcells inobesity:beneficialeffectsofweightreduction.EurHeartJ. 2008;29:1560---8.

10.Hill JM, Zalos G, Halcox JP, Schenke WH, Waclawiw MA, Quyyumi AA, et al. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:593---600.

11.TsaiTH,ChaiHT,SunCK,YenCH,LeuS,ChenYL,etal.Obesity suppressescirculatinglevelandfunctionofendothelial progen-itorcellsandheartfunction.JTranslMed.2012;10:137.

12.VermaS,KuliszewskiMA,LiSH,SzmitkoPE,ZuccoL,WangCH, etal.C-reactiveproteinattenuatesendothelialprogenitorcell survival,differentiation, and function:furtherevidenceof a mechanisticlinkbetweenC-reactiveproteinandcardiovascular disease.Circulation.2004;109:2058---67.

13.ButteNF,GarzaC,deOnisM.Evaluationofthefeasibilityof internationalgrowth standards for school-aged children and adolescents.JNutr.2007;137:153---7.

14.ZimmetP,AlbertiG,KaufmanF,TajimaN,SilinkM,Arslanian S,etal.Themetabolicsyndromeinchildrenandadolescents. Lancet.2007;369:2059---61.

15.Romualdo MC, de Nóbrega FJ, Escrivão MA. Insulin resis-tance in obese children and adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2014;90:600---7.

16.Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractantprotein-1(MCP-1):anoverview.JInterferon CytokineRes.2009;29:313---26.

17.RullA,CampsJ,Alonso-VillaverdeC,JovenJ.Insulinresistance, inflammation,andobesity:roleofmonocytechemoattractant protein-1(orCCL2)intheregulationofmetabolism.Mediators Inflamm.2010;2010,pii:326580.

18.BreslinWL,JohnstonCA,StrohackerK,CarpenterKC,Davidson TR,MorenoJP,et al.ObeseMexican Americanchildrenhave elevatedMCP-1,TNF-␣,monocyteconcentration,and dyslipid-emia.Pediatrics.2012;129:e1180---6.

19.Kotchen TA. Obesity-related hypertension: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and clinicalmanagement. Am JHypertens. 2010;23:1170---8.

20.MoserDC,GiulianoIdeC,TitskiAC,GayaAR,Coelho-e-SilvaMJ, LeiteN.Anthropometricmeasuresandbloodpressureinschool children.JPediatr(RioJ).2013;89:243---9.

21.Brambilla P, Antolini L, Street ME, Giussani M, Galbiati S, Valsecchi MG, et al. Adiponectin and hypertension in normal-weightandobesechildren.AmJHypertens.2013;26: 257---64.

22.ChiarelliF,MarcovecchioML.Insulinresistanceandobesityin childhood.EurJEndocrinol.2008;159:S67---74.

23.LeeS,BachaF,GungorN,ArslanianSA.Racial differencesin adiponectinin youth: relationship to visceralfat and insulin sensitivity.DiabetesCare.2006;29:51---6.

24.SteinbergerJ,SteffenL,JacobsDRJr,MoranA,HongCP,Sinaiko AR.Relationofleptintoinsulinresistancesyndromeinchildren. ObesRes.2003;11:1124---30.

25.SydowK,MondonCE,CookeJP.Insulinresistance:potentialrole oftheendogenousnitricoxidesynthaseinhibitorADMA.Vasc Med.2005;10:S35---43.

26.BruyndonckxL,HoymansVY,VanCraenenbroeckAH,VissersDK, VrintsCJ,RametJ,etal.Assessmentofendothelial dysfunc-tioninchildhoodobesityandclinicaluse.OxidMedCellLongev. 2013;2013:174782.

27.AsaharaT,MuroharaT,SullivanA,SilverM,vanderZeeR,Li T,etal.Isolation ofputativeprogenitorendothelialcellsfor angiogenesis.Science.1997;275:964---7.

28.WernerN,KosiolS,SchieglT,AhlersP,WalentaK,LinkA,etal. Circulatingendothelialprogenitorcellsandcardiovascular out-comes.NEnglJMed.2005;353:999---1007.