Faculdade de Motricidade Humana

Acute and long-term effects of combined exercise training on

vascular and autonomic function in patients with coronary

artery disease

Vitor Giatte Angarten

Orientadora: Doutora Maria Helena Santa-Clara Pombo Rodrigues

Tese especialmente elaborada para obtenção do grau de Doutor em Motricidade Humana na especialidade de Atividade Física e Saúde

Júri:

Presidente

Doutor Francisco José Bessone Ferreira Alves

Vogais

Doutor José Manuel Fernandes de Oliveira Doutora Ana Maria Ferreira das Neves Abreu Doutor Fernando Manuel da Cruz Duarte Pereira Doutora Maria Helena Santa-Clara Pombo Rodrigues Doutora Lucimere Bohn

“Somos o que somos hoje devido a nossas histórias passadas. O sonho se mistura com desejo, objetivo, satisfação, com o inusitado. Por onde andarei? Nada como a curiosidade para nos mover. O mundo progride não pelas respostas, mas sim pelas perguntas. Calar um pensamento é não deixar o vulcão explodir. Dê asas ao inusitado. Lembre-se, temos a chance diária de ser feliz. O dia lindo, a gente faz!”

Autor Desconhecido

Einstein already said:

“Life is like a bicycle. To stay balanced, you got to keep moving forward.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS / AGRADECIMENTOS

Somos o que somos devido às nossas histórias. Momentos, trajetórias, objetivos, sonhos, acaso ou não, seguimos o ritmo da batida dos nossos corações. Alcançar metas traz uma satisfação única, inexplicável muitas vezes, mas é por elas que continuamos a lutar.

Esta luta vem desde sempre, desde os nossos primeiros passos. Nessa época somente imaginávamos o que ser quando crescer. Garanto que não era por esse percurso que os meus pensamentos flutuavam. Com o decorrer da minha vida muitos sonhos vieram à tona, sendo alguns alcançados. Mas com a mão divina de Deus, os sonhos foram afunilando para uma realidade sólida e harmónica. Aos 5 anos comecei no desporto, a bola era maior que as minhas pernas. Até aos 16 anos quando uma sequência de lesões apareceu. Sonho automaticamente trocado. Ser piloto de avião foi o ápice da alma de criança, contudo limitado devido a algumas barreiras. Em seguida, as antigas lesões aproximaram-me do “cuidar”. Amigos e pessoas desconhecidas procuravam-me para torna-los novamente capazes de realizar movimentos e alcançar autonomia. Contudo, ainda estava com foco nas minhas loucuras, desportos radicais. Após um ano intenso de aprendizagem extrema fui novamente procurado para fazer parte de uma equipa interdisciplinar relacionada à saúde do coração. A partir daí, percebi por onde deveria traçar o meu caminho.

Até chegar aí, muitas pessoas marcaram a minha vida. Alguns sempre me empurraram para frente, outros tiraram-me do buraco, outros até me puxaram para o buraco. Mas com a cabeça centrada, consegui ouvir aqueles que realmente valiam a pena. Deus sempre me mostrou que a bela família é formada pelo alto nível de amizade com qualquer pessoa. Carrego comigo amigos pelo mundo. Sou colecionador! Devido a todas estas pessoas que conviveram comigo instantes ou ciclos de 2-3 anos, consegui encontrar esse “dom”.

Agradeço a cada familiar que encontrei ao longo do caminho. O simples fato de acreditar em mim, estabelece uma alta conexão ascendente. Meu querido professor já falecido Sidirley Barreto, e Eduardo Cartier que desde o primeiro dia de aula incentivaram-me a cultivar o conhecimento e respeito. Aqui estou!

Ao entrar para o mundo cientifico percebi que o rigor é usado diariamente na minha vida. O processo de estudar a base, analisar possibilidades, crias estratégias, testar métodos, analisar resultados, concluir e recomeçar, esteve comigo desde sempre. O Mestrado foi marcado por uma

equipa maravilhosa que realmente me transformou. Em seguida, um ano de ampla dedicação à universidade e ao hospital público abriu os meus olhos para novas fronteiras da Educação Física. Juntamente com outros amigos de profissão, estamos a tentar tornar a Educação Física mais saúde. Assim entrou o doutoramento nos planos e graças à Professora Helena Santa-Clara, que agradeço imensamente de coração e ao programa brasileiro “Ciências sem Fronteiras” foi possível concretizar o início de uma nova gestação de 4 anos. A Faculdade de Motricidade Humana abraçou-me de tal maneira que me senti em casa. Exemplos diários das pessoas que lá frequentam davam-me força e conforto para cada vez mais me dedicar ao objetivo principal. Grandes amigos carrego no meu coração, essa família chamada gabinete 8 e 9 e o Hospital Pulido Valente tornaram-me uma melhor pessoa. Todos que ali passaram contribuíram para a minha formação científica e pessoal. Sem palavras para descrever esta gratidão imensa em poder fazer parte desta família que me acolheu. Realmente, a felicidade de verdade profunda somente existe quando compartilhada!

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS / AGRADECIMENTOS ... v

INDEX OF FIGURES ...... xiii

INDEX OF TABLES ... xv

ABBREVIATIONS ... xvi

ABSTRACT ... xix

RESUMO ... xxi

RESUMO EXPANDIDO DA DISSERTAÇÃO...xxiii

SECTION A ... 1

I. DISSERTATION STRUCTURE ... 1

II. INTRODUCTION ... 5

REFERENCES……… 9

III. AIMS OF THE DISSERTATION ... 13

SECTION B ... 17

Chapter 1. Literature Review: HEART RATE VARIABILITY ... 17

1 HEART RATE VARIABILITY ... 19

1.1 ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY AND FUNCTION OF CARDIAC AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM ... 19

1.2 MECHANISMS OF CARDIAC AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM... 20

1.3 FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE THE CARDIAC AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM AND THE STRUCTURAL AND FUNCTIONAL CHANGES …..…. 22

1.3.1 AGING…..………...………… 22

1.3.2 CORONARY ARTERY DISEASES ...………...…….. 23

1.4 HEART RATE VARIABILITY AS A TOOL TO QUANTIFY THE AUTONOMIC SYSTEM ACTIVITY ... 25

1.5 EFFECTS OF EXERCISE ON HEART RATE VARIABILITY ... 30

1.5.1 ACUTE EFFECTS OF MAXIMAL EXERCISE ON HEART RATE VARIABILITY ………... 30

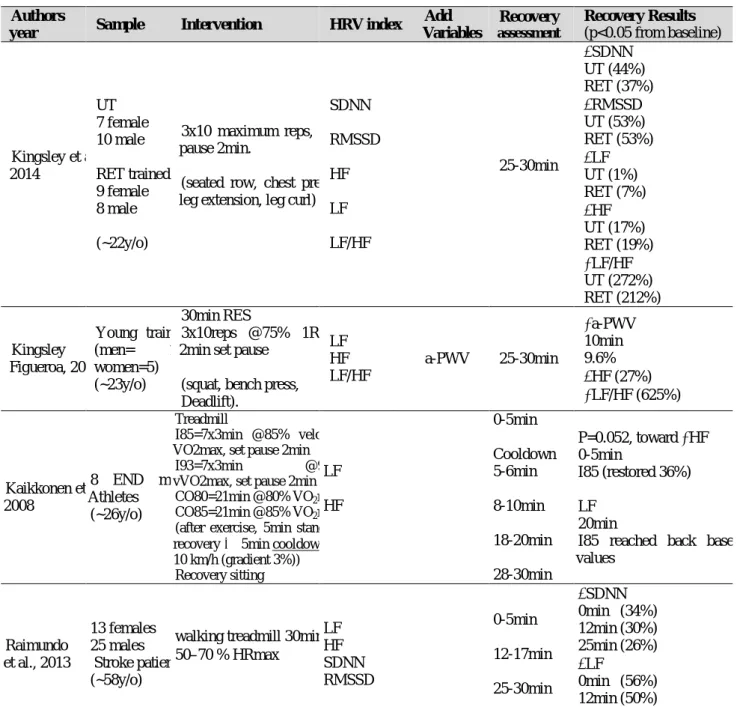

1.5.2 ACUTE EFFECTS OF EXERCISE BOUT ON HEART RATE VARIABILITY…. 34 1.5.3 CHRONIC EFFECTS OF EXERCISE ON HEART RATE VARIABILIT…...…... 40

1.6 REFERENCES ... 46

Chapter 2. Literature Review: ARTERIAL STIFFNESS ... 55

2 ARTERIAL STIFFNESS ... 57

2.1 ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY AND FUNCTION OF ARTERY ... 57

2.2 MECHANISMS OF ARTERIAL STIFFNESS ... 57

2.2.1 BIOCHEMICAL FACTORS OF VASCULAR TONE …….………...……….… 58

2.2.2 STRUCTURAL EXTRECELLUAR MATRIX OF VASCULAR TONE .……… 59

2.3 CONSEQUENCES OF ARTERIAL STIFFNESS TO THE CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM ……….60

2.4 MAJOR FACTORS THAT STIMULATE FUNCTIONAL CHANGES AND STRUCTURAL ALTERATIONS ... 61

2.4.1 AGING ...……….…..…...62

2.4.2 CORONARY HEART DISEASES……….……….…………....62 2.5 QUANTIFYING ARTERIAL STIFFNESS BY PULSE WAVE VELOCITY METHOD ………65

2.6.1 ACUTE EFFECTS OF MAXIMAL EXERCISE ON ARTERIAL STIFFNESS

... 66

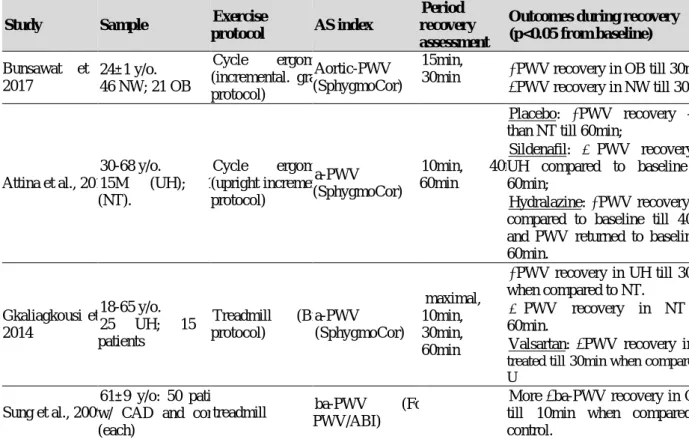

2.6.2 ACUTE EFFECTS OF EXERCISE BOUT ON ARTERIAL STIFFNESS ....... 69

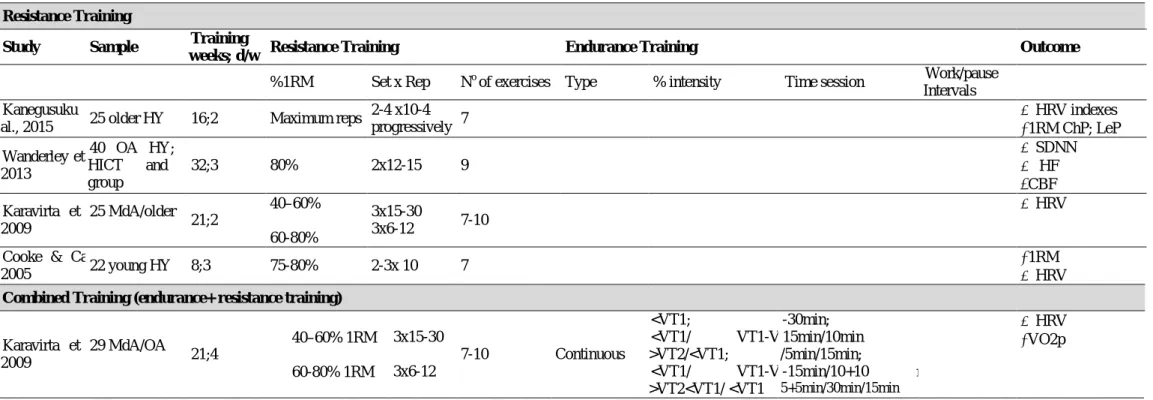

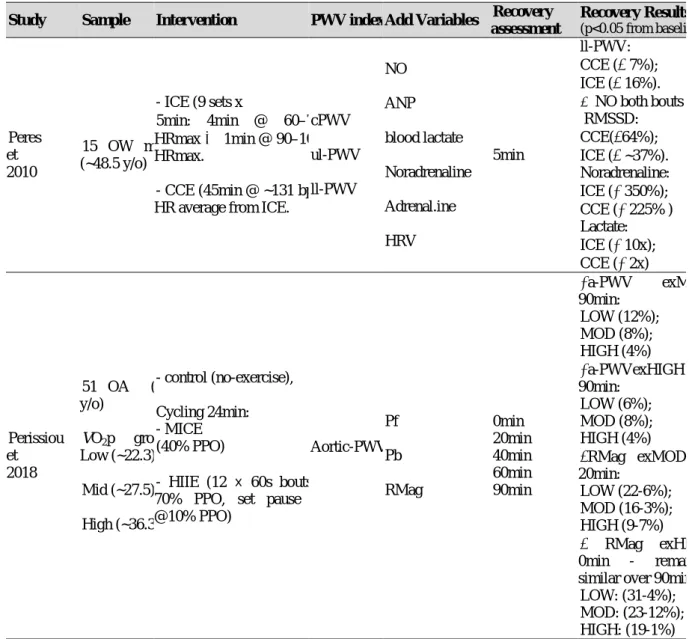

2.6.3 CHRONIC EFFECTS OF EXERCISE ON ARTERIAL STIFFNESS……...…….. 74

2.7 REFERENCES ... 82

SECTION C ... 93

Chapter 3. STUDIES METHODOLOGY ... 93

3 STUDIES METHODOLOGY ... 95

3.1 ETHICAL STATEMENT ... 95

3.2 PARTICIPANTS RECRUITMENT ... 95

3.2.1 INDIVIDUALS WITH CORONARY HEART DISEASES ………..………... 97

3.2.2 HEALTHY INDIVIDUALS ……….………..……... 99

3.3 ASSESSMENTS ... 98

3.3.1 CARDIOPULMONARY EXERCISE TEST ………..……….………. 98

3.3.2 MAXIMAL DYNAMIC STRENGTH ……….………....….… 100

3.3.3 HEART RATE VARIABILITY PARAMETERS ………....…….... 100

3.3.4 ARTERIAL STIFFNESS PARAMETERS ………...……..…. 102

3.4 REFERENCES ... 104

SECTION D ... 105

Chapter 4. Acute Exercise Effects On Vascular and Autonomic Function in Patients With Stable Coronary Artery... 105

4 ACUTE EFFECTS OF EXERCISE ON AUTONOMIC AND VASCULAR FUNCTION IN PATIENTS WITH STABLE CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE ... 107

4.1 ABSTRACT ... 107 4.2 INTRODUCTION ... 108 4.3 METHODS ... 109 4.4 RESULTS ... 113 4.5 DISCUSSION ... 118 4.6 LIMITATIONS... 121 4.7 CONCLUSION ... 121 4.8 REFERENCES ... 122

Chapter 5. High vs Moderate Intensity Combined Exercise Responses On Vascular And Autonomic Systems In Individuals With And Without Stable Coronary Artery Disease ... 127

5 HIGH VS MODERATE INTENSITY COMBINED EXERCISE RESPONSES ON AUTONOMIC AND VASCULAR SYSTEMS IN INDIVIDUALS WITH AND WITHOUT STABLE CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE ... 129

5.1 ABSTRACT ... 129 5.2 INTRODUCTION ... 130 5.3 METHODOLOGY ...,,... 131 5.4 RESULTS ... 136 5.5 DISCUSSION ... 142. 5.6 LIMITATIONS... 144 5.7 CONCLUSION ... 145 5.8 REFERENCES ... 145

Chapter 6. Effects of Periodized Training Regime on Vascular and Autonomic Systems in Trained Patients With Coronary Artery Disease:

A Randomized Controlled Trial. ... 151

6 EFFECTS OF PERIODIZED TRAINING REGIME ON VASCULAR AND AUTONOMIC SYSTEMS IN PATIENTS WITH CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL. ... Error! Bookmark not defined.3 6.1 ABSTRACT ... 151 6.2 INTRODUCTION ... 152 6.3 METHODOLOGY ... 153 6.4 RESULTS ... 160 6.5 DISCUSSION ... 163 6.6 Limitations ... 166 6.7 CONCLUSION ... 166 6.8 REFERENCES ... 166 SECTION E ... 171 Chapter 7. Discussion ... 171 7 DISCUSSION ... 173

7.1 HISTORICAL AND ADVANCES OF AUTONOMIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEMS ... 173

7.2 REFERENCES ... 180

7.3. General Discussion of the studies ... 190

7.4. REFERENCES ... 200

Chapter 8. General Conclusions ... 207

8 GENERAL CONCLUSIONS ... 209

Chapter 9. Future Perspectives ... 211

9 FUTURE PERSPECTIVES ... 213

9.1 REFERENCES ... 217

APPENDIX ... 219

APPENDIX 1- Scientific Ethical Document (chronic study)……… 221

APPENDIX 2 - Scientific Ethical Document (acute studies)……… 223

APPENDIX 3 – Informed Consent for participants classified as “untrained”: acute studies.225 APPENDIX 4 - Informed Consent for participants classified as “trained”: acute studies. ... 233

INDEX OF FIGURES

Figure 1.1. Vascular dysfunction with respective factors interaction ... 25 Figure 3.1. Heart rate variability analysis – Kubios software image. ... 102 Figure 3.2. The image displays the carotid, femoral, radial and distal posterior tibial arteries. ... 103 Figure 4.1. Study Design during symptom-limited ramp incremental cardiopulmonary test

(CPET) o

circle ergometer. ... 110

Figure 4.2. Arterial stiffness responses (aortic, upper and lower limb (A-B-C graphics,

respectively) a

rest and following (10-30min recovery period) a single maximal exercise ... 117

Figure 5.1. Study Design. ... 133 Figure 5.2 Aortic pulse wave velocity and high frequency after moderate and

Figure 6.1. Flow diagram of patients with CAD (screening / randomization / final analysis ... 155 Figure 6.2. Study Design.. ... 156 Figure 6.3. Periodized exercise prescription on the endurance and resistance training for 6 months.160

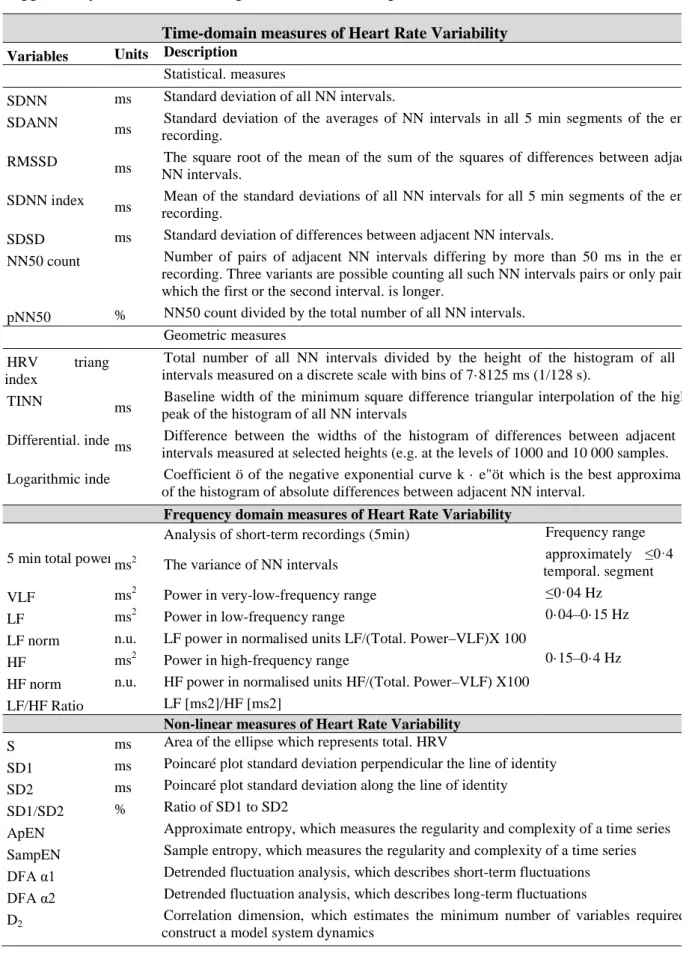

INDEX OF TABLES

Table 1.1. Summary of Heart rate variability (HRV) recordings, time and frequency domain indexes

suggested by Task Force HRV... 29

Table 1.2. Heart Rate Variability index and its correlation to sympathetic and/or parasympathetic

modulation. ... 30

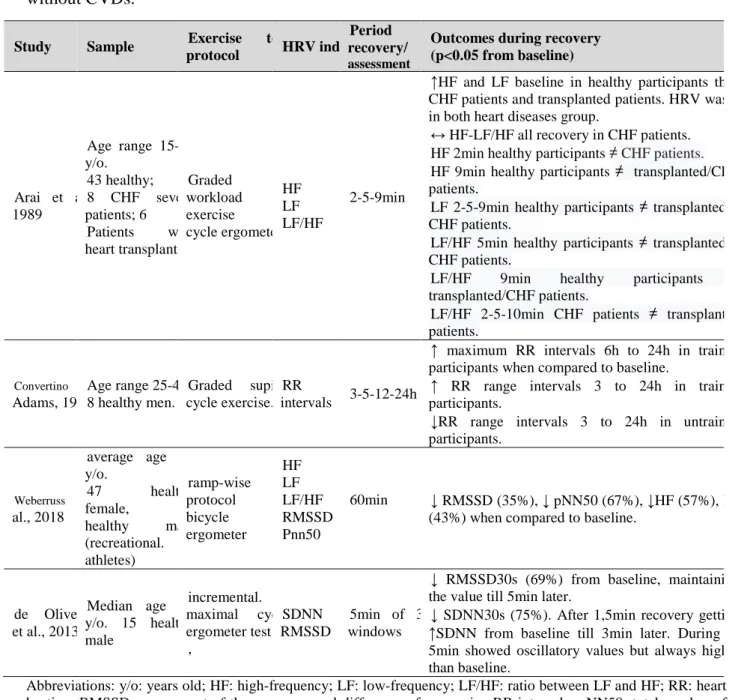

Table 1.3. Review about Maximal exercise Effort and Autonomic Nervous System with and without

CVDs. ... 32

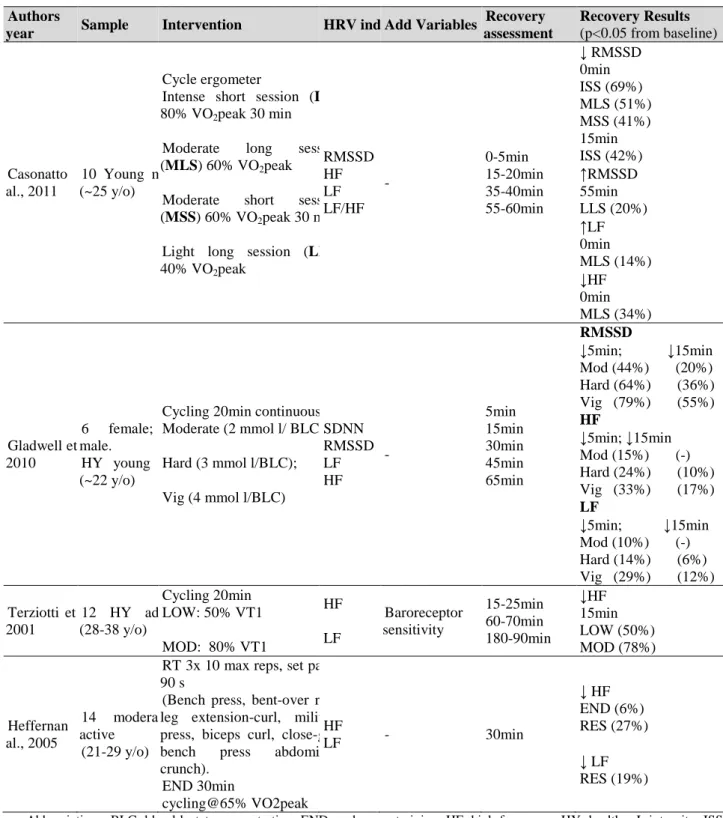

Table 1.4. Studies involving effects of a single exercise bout on pulse wave velocity. ... 35 Table 1.5. Effects of exercise training on the autonomic nervous system in healthy, athletes and

cardiovascular diseases. ... 42

Table 2.1. Study review about Maximal exercise Effort and Arterial stiffness in the elderly with and

without cardiovascular disease... 67

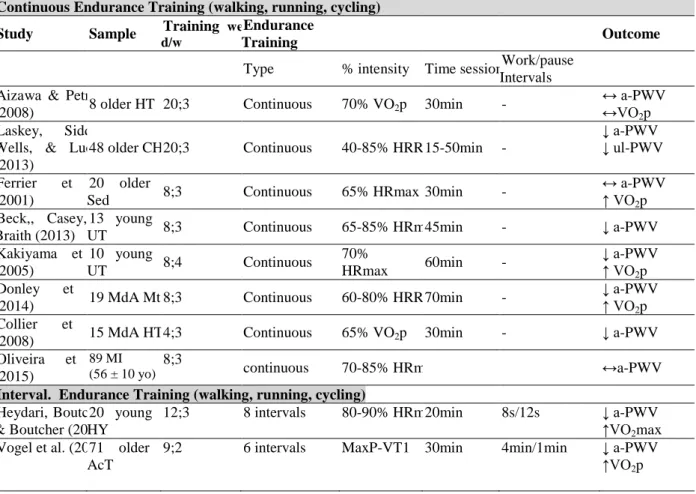

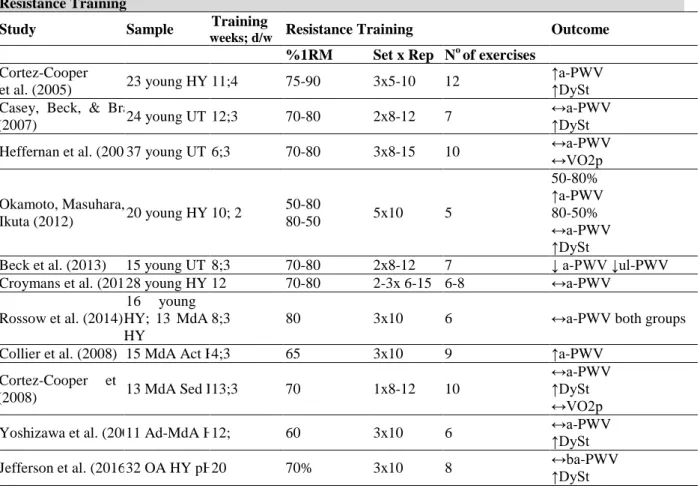

Table 2.2. Studies involving effects of a single exercise bout on pulse wave velocity. ... 71 Table 2.3. Effects of exercise training in arterial stiffness – Pulse Wave Velocity (Endurance). ... 75 Table 2.4. Effects of exercise training in arterial stiffness – Pulse Wave Velocity (Resistance Training).

... 76

Table 2.5. Effects of exercise training in arterial stiffness – Pulse Wave Velocity (Combined). ... 77 Table 4.1. Clinical characteristics of the participants among selected ranges of functional levels. ... 114 Table 4.2. Oxygen consumption and hemodynamic response to a maximal exercise effort... 115 Table 4.3. Arterial stiffness and Autonomic control responses to a maximal progressive exercise (ramp

protocol). ... 116

Table 5.1. Rest characteristics of the participants. ... 137 Table 5.2. Hemodynamics variables from Cardiopulmonary Exercise Maximal test. ... 138 Table 5.3. One-repetition maximum (6 machines) in absolute and relative values and bike load in each

bout. ... 138

Table 5.4. Dynamics responses of Vascular-Autonomic system through exercise bouts in patients with

and without CAD. ... 141

Table 5.5. Pearson´s correlation by group. Deltas (Δ) between moments from Moderate intensity

combined exercise bout. ... 142

Table 6.1. Baseline participant’s characteristics. ... 161 Table 6.2. Follow-up of Hemodynamics and fitness index performance of training in 24 weeks. .... 162 Table 6.3. Follow-up of Arterial stiffness and Autonomic system index of training in 24 weeks. .... 163

ABBREVIATIONS

Ach Acetylcholine

ACEi Angiotensin-converting enzyme Inhibition

a-PWV Aortic PWV

ANS Autonomic nervous system

ARBs Angiotensin receptor blockers

AS Arterial stiffness

ba-PWV Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity

BMI Body mass index

CABG Coronary artery bypass grafting

CAD Coronary artery disease

CAD-t Trained patients with CAD

CPET Cardiopulmonary exercise test

CO2 Carbon dioxide

COX Cyclooxygenase enzymes

CR Cardiac rehabilitation

CRE Circuit resistance exercise

CVD Cardiovascular diseases

CVS Cardiovascular system

DBP Diastolic blood pressure

ECG Electrocardiogram

eNOS Endothelial nitric oxide synthase

ET Endothelin

FCL Functional capacity level

FEV1 Forced expiratory volume in 1 second

FFIT-HY Fair-Fit healthy individuals

HF High-frequency

HICEB High intensity combined exercise bout

HR Heart rate

HRmax Maximal HR

HRR Heart rate recovery

HRV Heart rate variability

LF Low-frequency

ll-PWV Lower-limb PWV

LPCET Linear periodized combined exercise training

ln Natural log

LVET Left ventricle ejection time

NPCET Non-periodized combined exercise training

MDA Plasma malonyldialdehyde

MET Metabolic equivalent

MMPs Matrix metalloproteinases

MOCEB Moderate intensity combined exercise bout

NADPH Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

NE Norepinephrine

NO Nitric oxide

NW Normal weight

O2 Oxygen

O2−· Anion superoxide

OW Overweight

Pb Reflected pressure waves

PCI Percutaneous coronary intervention

Pf Forward pressure wave

PFIT-CAD Poor-Fit patients with CAD

PGI2 Prostacyclin

PPO Peak power output

PWV Pulse wave velocity

RAAS Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

RM Repetition maximum

RNS Reactive nitrogen species

ROS Reactive oxygen species

rpm Revolutions per minute

RR Intervals between each heart rate from R wave.

RT Resistance training

SANS Sympathetic autonomic nervous system

SBP Systolic blood pressure

SMC Smooth Muscle cells

TRIMP Training Impulses

ul-PWV Upper limb-PWV

VPFIT-CAD Very Poor-Fit patients with CAD

VO2 Oxygen consumption VT Ventilatory threshold

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Exercise training is potentially recommended to improve heart rate variability

(HRV) and arterial stiffness (AS) in coronary artery disease patients (CADp). Purposes: To analyse the acute and chronic effects of exercise stimuli (acute: A- maximal, B- bouts; chronic:

C- training) on cardiac-ANS and AS in CADp. Methods: Participants: A- participants classified

according to cardiorespiratory fitness: Untrained CADp as Very Poor-Fit (VPFIT-CAD; n=18); Trained CADp as Poor-Fit (PFIT-CAD; n=18); Trained healthy match individuals as Fair-Fit (FFIT-HY; n=18); B- trained CADp (CAD-t, n=18) and trained healthy individuals (HY-t, n=18); C- trained CADp divided in periodized (n=12) and non-periodized (n=12) groups. Exercise protocol: A- maximal ramp protocol; B- moderate (MOCEB) and high intensity (HICEB) combined exercise bouts; C-. periodized and non-periodized training. Results: A- CADp and healthy peers had similar HRV decrease, and AS increase during recovery. B- HICEB increased aortic- pulse wave velocity (PWV) and decrease high-frequency parameters during recovery in CAD-t; group-effect was found after HICEB on upper limb-PWV; both groups had similar responses after MOCEB on HRV and AS parameters; C- Non-periodized training was more effective to improve peripheral AS; no changes in HRV parameters in both protocols, as well as VO2peak. Conclusion: AS and HRV parameters after maximal effort is not

functional level-dependent on either health status-dependent in stable patients; exercise intensity is the major factor for exercise prescription in individuals with and without CAD, determining the thin frontier between acute exercise adaptation and imbalance; non-periodized is superior to periodized training to improve peripheral AS in trained CADp.

Key-words: coronary artery diseases; acute exercise; chronic exercise; heart rate variability;

arterial stiffness; periodized training.

RESUMO

Introdução: O treino físico é potencialmente recomendado para aprimorar a variabilidade da

frequência cardíaca (VFC) e a rigidez arterial (RA) em pacientes com doença arterial coronariana (DACp). Objetivos: Analisar os efeitos agudos e crônicos dos estímulos ao exercício (agudos: A- máximo, B- sessões; C- crônico: treinamento) na VFC e RA no DACp. Métodos: Participantes: A- participantes classificados de acordo com a aptidão cardiorrespiratória: DACp não-treinados como muito baixa (MB-DAC; n=18); DACp treinados como baixa (B-DAC; n=18); Indivíduos saudáveis treinados como razoável (R-SAU; n=18); B- DACp treinados (DAC-t, n=18) e indivíduos saudáveis treinados (SAU-t, n=18); C- DACp treinados dividido em grupos periodizado (n=12) e não-periodizado (n=12). Protocolos de exercício: A- protocolo de rampa máximo; B- sessões de exercícios combinados de moderada (SECMO) e alta intensidade (SECAL); C-. treinamento periódico e não periodizado. Resultados: A- DACp e pares saudáveis apresentaram semelhante diminuição da VFC e aumento da RA durante a recuperação.

B- SECAL aumentou a velocidade da onda de pulso (VOP) aórtico e diminuiu os parâmetros de

alta-frequência durante a recuperação em DAC-t; o efeito do grupo foi encontrado após SECAL na VOP do membro superior; ambos os grupos tiveram respostas semelhantes após o SECMO nos parâmetros de VFC e RA; C- Treinamento não-periodizado foi mais eficaz para aprimorar a RA periférica; nenhuma alteração encontrada nos parâmetros da VFC em ambos os protocolos, bem como no VO2pico. Conclusão: Os parâmetros RA e VFC após o esforço máximo não

dependem do nível funcional e do estado de saúde em pacientes estáveis; a intensidade do exercício é o principal fator para a prescrição do exercício em indivíduos com e sem DAC, o que determina a fina fronteira entre adaptação e desequilíbrio agudo ao exercício; treino não-periodizado é superior ao não-periodizado para aprimorar a RA periférica em DACp treinados.

Palvras-chave: doença das artérias coronárias, exercícios agudos, exercício crónico,

RESUMO EXPANDIDO DA DISSERTAÇÃO

Para contemplar todo o conhecimento necessário para esta dissertação, a estrutura da mesma foi dividida em: seção A apresenta a estrutura, introdução e objetivos da dissertação; seção B inclui 2 capítulos sobre revisão da literatura a respeito da variabilidade da frequéncia (1) cardíaca e rigidez arterial (2); seção C descreve detalhamente metodologias utilizadas nos estudos da dissertação (capítulo 3); secção D é composto por 3 capítulos (4-5-6), os quais são compostos pelos 3 estudos desenvolvidos; secção E, por fim, inclui discussão, conclusão geral e futuras perspectivas da dissertação (7-8-9 capítulos, respectivamente).

Uma extensa consulta de evidências científicas foram necessárias para construir a justificativa e objetivos dessa dissertação como é demonstrado a seguir.

A doença cardiovascular (DCV) é um grupo de enfermidades que se caracteriza pela disfunção do coração como bomba e dos vasos como condutores. Dentre as DCV, a doença arterial coronária (DAC) distingue-se por apresentar o processo de aterosclerose nas artérias coronárias, sintomas como angina instável, associada ao enfarte do miocárdio e elevada mortalidade. Os pacientes com DAC apresentam geralmente intolerância ao exercício a qual varia, em parte, com a gravidade da doença. O mecanismo determinante dessa intolerância pode relacionar-se com disfunções do sistema nervoso autónomo (SNA) cardíaco e rigidez arterial (RA). Populações com fatores de risco para DCV, com destaque para o envelhecimento, podem apresentar desequilíbrio SNA baseado em baixa ativação vagal e alta ativação simpática que pode influenciar direta ou indiretamente a velocidade da onda de pulso (VOP, marcador da RA). Mecanismos da função endotelial que envolvem oxido nítrico, espécies reativas de oxigénio e azoto, sistema renina-angiotensina, tónus celular liso e outros, podem vir a substituir o módulo de elastina por fibras de colagéneo. Assim, baixa variabilidade da frequência cardíaca (VFC, marcador do SNA) é relacionada com elevada VOP.

A diminuição das limitações originadas pela DAC e melhoria do prognóstico dos pacientes são significativamente influênciados pelo treino físico. Os benefícios do exercício físico nos sistemas vascular e autónomo, em indivíduos com e sem DAC, estão já bem comprovadas pela extensa literatura. Para esses indivíduos, a prescrição de exercício baseia-se em manutenção do volume e intensidade durante toda intervenção. No entanto, outras metodologias de treino como a “periodizada”, oriunda do desporto, estão a migrar para o campo da reabilitação cardiovascular.

Quanto aos efeitos do treino físico, ainda são discutíveis as respostas dos mecanismos agudos da VFC e RA, e sua relação após o esforço. Nesse contexto, revisões de literatura

recentes sobre o efeito do exercício agudo/crónico na VFC e RA foram desenvolvidas. Contudo, tais revisões sobre exercícios agudos (máximo e sessão de exercício) e crónicos envolvem, de forma geral, individíduos saudáveis, sugerindo assim novos estudos a respeito de indivíduos com DCV. Não obstante, existem ainda lacunas científicas sobre exercícios e sistemas vasculares e autonómicos, apesar da variada evidência disponível. Dessa forma, esta dissertação foi elaborada com o objetivo de disponibilizar novas evidências que vão contribuir para minimizar as lacunas existentes, nomeadamente: respostas agudas e crónicas da variabilidade da frequência cardíaca e rigidez arterial após exercício físico, relacionadas com a patologia arterial coronariana. Para abordar de forma breve os estudos desenvolvidos, nesse resumo expandido são apresentados os 3 invetigações abaixo:

Capítulo 4: Efeitos do exercício agudo nas funções vascular e autónoma em pacientes com

doença arterial coronária

Objetivo: Examinar o efeito agudo de um esforço máximo nos índices da RA e a VFC em

pacientes com DAC com diferentes níveis de capacidade funcional e a relação entre esses parâmetros.

Métodos: Foram criados três grupos distintos com idades compreendidas entre 55 e 80 anos:

Dezoito pacientes com DAC, não treinados; dezoito pacientes com DAC, treinados, e dezoito indivíduos saudáveis emparelhados por sexo-idade-índice de massa corporal tiveram sua VFC, VOP aórtica e periférica avaliadas em repouso, 10 e 30 minutos após um teste de esforço cardiopulmonar máximo em cicloergómetro.

Resultados: Os grupos foram classificados e nomeados, respectivamente, de acordo com a

aptidão cardiorrespiratória (VO2pico): Muito baixa (MBFIT-DAC; 5,2 ± 0,8METs), baixa

(BFIT-DAC; 6,5 ± 1,4METs) e razoável (RFIT-SAU; 8,5 ± 1,8METs). Não foram observados efeitos significativos da interação “Grupo * Tempo”. Observou-se que, resultante do esforço máximo ocorreu um aumento significativo da VOP aórtica (MBFIT-DAC: 9,3%; BFIT-DAC: 12,5%; RFIT-SAU: 7%), imediatamente após o termino mas que se manteve durante 30 min, apenas para a BFIT-DAC (11%); uma diminuição da VOP-membro inferior (MBFIT-DAC: 5%; RFIT-SAU: 4%) 10 minutos após o termino. A análise no domínio do tempo da VFC mostrou que o RMSSD (Root Mean Square of Sucessive Differences) diminuiu significativamente logo após o exercício em MBFIT-DAC (11%) e BFIT-DAC (18%), enquanto a análise no domínio da frequência mostrou que a razão entre low frequency/high frequency (LF/HF) esteve aumentada aos 30 min (MBFIT-DAC = 208 %; RFIT-SAU = 108%).

Nos pacientes com DAC, as alterações na diferença (entre repouso e 10 min) da VOP aórtica foram associadas a alterações da LF/HF em BFIT-DAC, bem como para a diferença entre o repouso e 30 min da LF/HF em MBFIT-SAU, e RMSSD em BFIT-DAC.

Capítulo 5: Alta vs Moderada intensidade de exercícios combinados em respostas dos sistemas

vascular e autónomo em indivíduos com e sem doença arterial coronária

Objetivo: Analisar as respostas agudas do exercícios combinados de diferentes intensidades na

RA e VFC em indivíduos com e sem DAC e a associação entre elas.

Métodos: Dezoito indivíduos treinados (62 ± 10 anos) com DAC (DAC-t), e dezoito treinados

saudáveis (SAU-t), emparelhados de acordo com a idade-sexo-índice de massa corporal, realizaram duas sessões combinadas de exercícios: (i) intensidade moderada (18 min de ciclismo na frequência cardíaca (FC) equivalente ao limiar ventilatório (LV) 1 mais 2 séries 60%1RM de treino em circuito (TC) (SECMO), e (ii) alta intensidade (5 intervalos de 2min em LV2 intercalados com 4 intervalos em LV1, mais 2 séries, 80%1RM em TC) (SECAL). A RA e a VFC foram avaliadas em repouso e recuperação (0-15-30 min).

Resultados: Os grupos foram heterogéneos quanto ao estado de saúde e aptidão

cardiorrespiratória (DAC-t; 23,9 ± 1,2; SAU-t; 29,4 ± 1,2 ml/kg/min). No grupo DAC-t: a VOP aórtica aumentou (7,5%) e observou-se uma diminuição significativa dos parâmetros da VFC (SDNN-standard deviation of normal sinus beats, 12,5%; RMSSD 18%; HF 26%) imediatamente após o SECAL; o SECMO diminuiu 12% do SDNN logo após a interrupção do exercício; O tempo de ejeção do ventrículo esquerdo (TEVE) permaneceu significativamente menor (aproximadamente 10%) durante 30 min após o SECAL em comparação com o valor de repouso. No SAU-t não se observou nenhum efeito de ambas as sessões nos parâmetros VOP; O TEVE diminuiu significativamente logo após a interrupção do SECAL (14%); apenas o RMSSD diminuiu significativamente 0 min após as duas sessões (SECMO 12%; SECAL: 17%). Observou-se uma diferença significativa na VOP-membro superior 15 a 30 min após o SECAL, devido ao grupo. A associação RA e VFC foi mais evidente após o SECAl do que o SECMO no grupo saudável.

Capítulo 6: Efeito do treino periodizado e não periodizado em pacientes treinados com doença

arterial coronária

Objetivos: Comparar os efeitos do treino periodizado e não-periodizado nos parâmetros da VFC,

VOP e VO2.

Métodos: Vinte e quatro pacientes, treinados, com DAC estável (64 ± 10 anos) que realizaram

60 sessões (3 vezes/semana; 1 h/dia) foram distribuídos aleatoriamente por 2 grupos: treino periodizado de exercício combinado (TPEC) e não periodizado (TNPEC) de treino. Todos os

participantes foram submetidos, nos momentos pré e pós intervenção, a avaliação do (i) esforço cardiopulmonar máximo em rampa em cicloergometro; (ii) 1 repetição máxima, (iii) VOP e (iv) VFC em repouso.

Resultados: Não se detetaram diferenças entre as características dos grupos. Ambos os grupos

não demonstraram alterações no VO2pico e na força máxima. No grupo TPEC, a VOP do

membro superior, a pressão diastólica central e a TEVE diminuíram significativamente (16%, 7% e 11%, respetivamente) e a pressão de pulso central aumentou significativamente (22%). No grupo TNPEC, a VOP do membro superior, a VOP do membro inferior e o TEVE diminuíram significativamente (10%, 9% e 16%, respetivamente). Não se observaram diferenças significativas entre o treino pré e pós nos índices da VFC em ambos os grupos. Observaram-se, no TPEC, correlações de Pearson moderadas na VO2pico Aórtica VOP e na SDNN-Aórtica

VOP.

Conclusão geral

- As respostas vasculares e autonómicas ao exercício máximo foram semelhantes entre os participantes com e sem DAC com distintos níveis de capacidade funcional; Alterações induzidas pelo exercício na VOP aórtica foram associadas a alterações da VFC em pacientes com DAC, mas não em indivúdos aparentemente saudáveis;

- Após sessões de exercício combinado, os pacientes com DAC apresentam respostas agudas semelhantes à VOP e à VFC para ambos os exercícios, em comparação com indivíduos saudáveis. A associação entre sistemas é mais evidente no grupo saudável;

- A prescrição não-periodizada padrão de longa duração para pacientes com DAC estável, treinados, foi mais eficaz em na melhoria da rigidez arterial periférica. Não foram observadas alterações nos dois grupos nos índices de VFC de curta duração e VO2. O nosso estudo

pressupõe que o exercício pode contribuir na melhoria da rigidez arterial, mas não o equilíbrio autonómico, independentemente do método de treino.

Palvras-chave: doença das artérias coronárias; exercício máximo; sessões de exercício

Presentations and posters

Angarten V, Pinto R, Santos V, Melo X, Rodrigues J, Santa-Clara M. Exercise Effects on

Autonomic/Vascular Systems in Coronary Trained Patients: a Pilot Study. In: Congresso Português de Cardiologia - CPC 2018. Albufeira: Socidade Portuguesa de Cardiologia; 2018 (Angarten, Pinto, Santos, Melo, Rodrigues, et al., 2018).

Angarten V, Pinto R, Santos V, Melo X, Sousa P, Rodrigues J, et al. Acute Exercise Effects on

Vascular and Autonomic Function in Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease. In: Cruickshank J, editor. ARTERY 18 Congress. Guimarães: ARTERY; 2018. p. 42 (Angarten, Pinto, Santos, Melo, Sousa, et al., 2018).

SECTION A

I. DISSERTATION

STRUCTURE

The present dissertation follows the modern style which is both a compilation of chapters that show the knowledge review around the theme and the original data produced during the experimental process compiled in papers.

The dissertation is divided into five main sections, comprising several chapters.

Section 1 includes the I. Dissertation structure; II. Introduction, the III. Aims of the

dissertation and this sub-section.

Section 2, includes an extensive literature review, a complete step by step understanding

of specific physiology, measurements, and effects of exercise on the Heart Rate Variability (HRV) in Chapter 1 and on the Arterial Stiffness (AS) in Chapter 2.

Section 3 describes in detail the participant's recruitment and the assessments that were

performed. The exercise prescription and statistical analysis were described in each study: Chapter 3. Studies Methodology

Section 4 consists of 3 chapters whose aims were previously described in the Aims

chapter. These aims were designed to follow an order of knowledge that has a starting point - the maximum effort test - which is used both for diagnosis and prognosis of chronic pathologies as well as for prescription of exercise training: Chapter 4: Acute Exercise Effects On Vascular And Autonomic Function In Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease.

Secondly, the analysis of the exercise bout based on the American College of Sports and Medicine prescription and worldwide guidelines for cardiovascular rehabilitation - Chapter 5: High vs Moderate Intensity Combined Exercise Responses On Vascular And Autonomic Systems In Individuals With Or Without Stable Coronary Artery Disease.

Finally, the analysis of the achievement of the set of exercise sessions distributed in the periodized and non-periodized methods - Chapter 6: Effects Of Periodized And Non-Periodized Combined Training On Vascular And Autonomic Systems In Patients With Coronary Artery Disease.

Section 5 includes 3 chapters. Chapter 7: Discussion brought information that implicates with

the scientific progress of HRV and AS during recovery and how our research results may contribute to the scientific field. Chapter 8: General conclusions, draw the overall conclusions based on the several studies performed during the experimental work, described in the present dissertation. Finally, Chapter 9: Future perspectives, addresses critically the limitations found in published studies, cited previously in the literature review, as well as in the design and assessment of the ones performed during this experimental work. As a result of the critical analysis, future directions are proposed and discussed.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) is a group of diseases, including both the heart and vessels, characterizing cardiovascular system (CVS) imbalance (Mendis, Puska, & Norrving, 2011). Among the CVD, coronary artery disease (CAD) is distinguished by presenting atherosclerosis in coronary arteries and possibly symptoms such as unstable angina. CAD is frequently associated with myocardial infarction, which results in high mortality level (Timmis et al, 2017; Lippi, Sanchis-Gomar, & Cervellin, 2016).

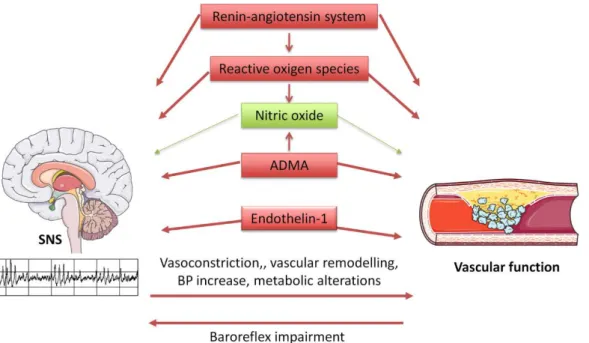

Patients with CAD have higher exercise intolerance compared with their healthy peers and the magnitude of this limitation varies in part with the severity of disease (Clausen, 1976). The determinant mechanism of this exercise intolerance may be explained by the relationship between the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and arterial stiffness (AS) (Enko & et al., 2008; Lu et al., 2016). The CVS is under the direct control of the ANS. Going deeper in this relationship, it has been demonstrated in diversified CVD risk factors populations (Chorepsima et al., 2017; Palatini et al., 2011; Skrapari et al., 2007), emphasizing the aging process factor (Fajemiroye et al., 2018), as well as chronic heart diseases (Fajemiroye et al., 2018; Huikuri et al., 1999). Moreover, ANS imbalance is associated with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in people with or without CVD (Hillebrand et al., 2013; Huikuri et al., 1999; Lu et al., 2016). Low heart rate variability (HRV) represents decreased parasympathetic cardiac control and has been associated with various chronic diseases (Malpas, 2010; Shaffer, McCraty, & Zerr, 2014; Simula et al., 2014; Thayer, Yamamoto, & Brosschot, 2010). Sympathetic regulation of vascular function is specially related to decreased nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability in endothelial cells due to ANS pathways (Carthy, 2014). AS may be directly or indirectly influenced by both sympathetic tonus and arterial wall mechanisms (NO; reactive oxygen and nitrogen species; renin-angiotensin system; smooth muscle cells-SMC tone) and, at the same time, NO may interact with the central nervous system by sympathetic discharge without reflex responses (Carthy, 2014). All those dysfunctional factors may interfere with the passive structures of the artery wall and cause the stiffness process where the elastic elastin modulus of the wall are dominated by the collagen fibres (Wagenseil & Mecham, 2009). In this context, Kotecha et al (2012) evaluated 470 patients with ≥50% stenosis and developed short-term HRV as a marker of autonomic control of the vasculature to correlate with angiogram and determine it as a cardiovascular risk factor.

To overcome health limitations due to CAD, exercise training composed by combined or single training of endurance and resistance correlates to a good prognosis (Abell, Glasziou, & Hoffmann, 2017; Kachur et al., 2017; Sumner, Harrison, & Doherty, 2017). Some reviews have also demonstrated that resistance exercises have benefits on vascular and autonomic systems in

individuals with and without CVDs (Ashor et al., 2014; Boutcher, 2016; Nolan, Jong, Barry-Bianchi, Tanaka, & Floras, 2008; Oliveira et al., 2014; Oliveira et al., 2013; Routledge et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2018). All the interventions had positive feedback on both systems, with some specific benefits according to the type of training (endurance or high intensity interval training; resistance training; combined training). As described previously, individuals with CAD have been associated with abnormal cardiac autonomic activity and heightened arterial stiffness (Bruno et al., 2012; Huikuri et al., 1999). Oliveira et al have two important reviews about both themes, concluding: exercise training is a useful treatment to improve ANS balance (Oliveira et al., 2013) and it is able to reduce AS and related measures even with short-term training (Oliveira et al., 2014). Analyzing the studies prescription, independent of the method (continuous or interval training, and resistance training), the stimuli is the same during the intervention, with no variance of volume and intensity. However, new insight is coming through, the “periodized” method of prescription has been applied initially in sport from the beginning of the previous century (Bompa & Buzzichelli, 2015) and recently it was applied in the cardiovascular rehabilitation (CR) field with great prospective results (Boggenpoel, Nel, & Hanekom, 2018; de Macedo et al., 2018, 2012).

Regarding the effects of exercise training, the acute response of HRV and AS, and their relationship is still debatable. Some recent reviews were found regarding acute exercise plus HRV and AS. Summarizing: in young/adult healthy sample, the acute endurance exercise didn´t change aortic PWV (a-PWV) significantly and acute resistance training, on the other hand, increased significantly this central AS parameter (Pierce et al., 2018); aortic and ul-PWVis increased significantly soon after exercise cessation (0-5min recovery) and the lower segment PWV is decreased post exercise longer than 5min in healthy adults (Mutter et al., 2017); resistance training is able to decrease vagal activity regardless of age (Kingsley & Figueroa, 2014); the intensity of exercise is the major factor influencing HRV but the duration follows the same responses, exerting an inverse relationship (higher intensity leads to lower HRV soon after exercise ends and it can cause a “delay” on the vagal reactivation (Michael et al., 2017).

Even though several reviews have been made about exercise and both vascular and autonomic systems, there is still room for improvement and scientific gaps to fill. Hence, this dissertation was designed to complete some scientific lacunas around the connection among coronary artery pathology, HRV and arterial stiffness after acute-chronic exercise training.

REFERENCES

Abell, B., Glasziou, P., & Hoffmann, T. (2017). The Contribution of Individual Exercise Training Components to Clinical Outcomes in Randomised Controlled Trials of Cardiac Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review and Meta-regression. Sports Medicine - Open, 3(1), 19.

Angarten, V., Pinto, M., Santos, V., Melo, X., Sousa, P., Rodrigues, J., & Santa-Clara, M. (2018). Acute Exercise Effects on Vascular and Autonomic Function in Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease. In J. Cruickshank (Ed.), ARTERY 18 Congress (p. 42). Guimarães: ARTERY.

Angarten, V., Pinto, R., Santos, V., Melo, X., Rodrigues, J., & Santa-Clara, M. (2018). Exercise Effects on Autonomic/Vascular Systems in Coronary Trained Patients: a Pilot Study. Congresso Português de Cardiologia - CPC 2018. Albufeira: Socidade Portuguesa de Cardiologia.

Ashor, A. W., Lara, J., Siervo, M., Celis-Morales, C., & Mathers, J. C. (2014). Effects of Exercise Modalities on Arterial Stiffness and Wave Reflection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e110034.

Boggenpoel, B. Y., Nel, S., & Hanekom, S. (2018). The use of periodized exercise prescription in rehabilitation: a systematic scoping review of literature. Clinical Rehabilitation, 32(9), 1235–1248. Bompa, T. O., & Buzzichelli, C. (n.d.). Periodization : theory and methodology of training (6th ed.; R. W.

Earle, Ed.). Champaign, IL.: Human Kinetics.

Boutcher, Y. N. (2016). Autonomic and Vascular Adaptations to Exercise: Implications for Cardiovascular Health. In Sport Medicine (pp. 1–15). SMGEbooks.

Bruno, R. M., Ghiadoni, L., Seravalle, G., Dell’oro, R., Taddei, S., & Grassi, G. (2012). Sympathetic regulation of vascular function in health and disease. Frontiers in Physiology, 3, 284.

Carthy, E. R. (2014). Autonomic dysfunction in essential hypertension: A systematic review. Annals of Medicine and Surgery (2012), 3(1), 2–7.

Chorepsima, S., Eleftheriadou, I., Tentolouris, A., Moyssakis, I., Protogerou, A., Kokkinos, A., … Tentolouris, N. (2017). Pulse wave velocity and cardiac autonomic function in type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Endocrine Disorders, 17(1), 27.

Clausen, J. P. (1976). Circulatory adjustments to dynamic exercise and effect of physical training in normal subjects and in patients with coronary artery disease. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 18(6), 459–495.

de Macedo, R. M., Carolina Brandt de Macedo, A., Faria-Neto, J. R., Costantini, C. R., Costantini, C. O., Olandoski, M., … Cesar Guarita-Souza, L. (2018). Superior Cardiovascular Effect of the Periodized Model for Prescribed Exercises as Compared to the Conventional one in Coronary Diseases. International Journal of Cardiovascular Sciences, 31(4), 393–404.

de Macedo, R. M., Neto, J. R. F., Costantini, C. O., Olandoski, M., Casali, D., de Macedo, A. C. B., … Guarita-Souza, L. C. (2012). A periodized model for exercise improves the intra-hospital evolution of patients after myocardial revascularization: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation, 26(11), 982–989.

EHN - Europan Heart Netwotk. (n.d.). European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2017 - EHN - European Heart Network. Retrieved from 2017 website: http://www.ehnheart.org/cvd-statistics.html Enko, K., & et al. (2008). Arterial Stiffening is Associated with Exercise Intolerance and

Hyperventilatory Response in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. Clinical Medicine: Cardiology, 2, 41–48.

Fajemiroye, J. O., Cunha, L. C. da, Saavedra-Rodríguez, R., Rodrigues, K. L., Naves, L. M., Mourão, A. A., … Pedrino, G. R. (2018). Aging-Induced Biological Changes and Cardiovascular Diseases. BioMed Research International, 2018, 1–14.

Hillebrand, S., Gast, K. B., de Mutsert, R., Swenne, C. A., Jukema, J. W., Middeldorp, S., … Dekkers, O. M. (2013). Heart rate variability and first cardiovascular event in populations without known cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis and dose–response meta-regression. EP Europace, 15(5), 742– 749.

Huikuri, H V, Jokinen, V., Syvänne, M., Nieminen, M. S., Airaksinen, K. E., Ikäheimo, M. J., … Frick, M. H. (1999). Heart rate variability and progression of coronary atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 19(8), 1979–1985.

Huikuri, Heikki V, Jokinen, V., Syvänne, M., Nieminen, M. S., Airaksinen, K. E. J., Ikäheimo, M. J., … Frick, M. H. (1999). Heart Rate Variability and Progression of Coronary Atherosclerosis. In Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol (Vol. 19).

Kachur, S., Chongthammakun, V., De Schutter, A., Arena, R., Milani, R. V., & Franklin, B. A. (2017). Impact of cardiac rehabilitation and exercise training programs in coronary heart disease. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 60(1), 103–114.

Kingsley, J. D., & Figueroa, A. (2014). Acute and training effects of resistance exercise on heart rate variability. Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging, 36(3), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpf.12223

Kotecha, D., New, G., Flather, M. D., Eccleston, D., Pepper, J., & Krum, H. (2012). Five-minute heart rate variability can predict obstructive angiographic coronary disease. Heart, 98(5), 395–401.

Lippi, G., Sanchis-Gomar, F., & Cervellin, G. (2016). Chest pain, dyspnea and other symptoms in patients with type 1 and 2 myocardial infarction. A literature review. International Journal of Cardiology, 215, 20–22.

Lu, D.-Y., Yang, A. C., Cheng, H.-M., Lu, T.-M., Yu, W.-C., Chen, C.-H., & Sung, S.-H. (2016). Heart Rate Variability Is Associated with Exercise Capacity in Patients with Cardiac Syndrome X. PLOS ONE, 11(1), e0144935.

Malpas, S. C. (2010). Sympathetic nervous system overactivity and its role in the development of cardiovascular disease. Physiological Reviews, 90(2), 513–557.

Mendis, S., Puska, P., & Norrving, B. (2011). Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control.

Michael, S., Graham, K. S., Davis, G. M., & OAM. (2017). Cardiac Autonomic Responses during Exercise and Post-exercise Recovery Using Heart Rate Variability and Systolic Time Intervals-A Review. Frontiers in Physiology, 8, 301.

Mutter, A. F., Cooke, A. B., Saleh, O., Gomez, Y.-H., & Daskalopoulou, S. S. (2017). A systematic review on the effect of acute aerobic exercise on arterial stiffness reveals a differential response in the upper and lower arterial segments. Hypertension Research, 40(2), 146–172.

Nolan, R. P., Jong, P., Barry-Bianchi, S. M., Tanaka, T. H., & Floras, J. S. (2008). Effects of drug, biobehavioral and exercise therapies on heart rate variability in coronary artery disease: a systematic review. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation, 15(4), 386–396.

Oliveira, Norton Luis, Ribeiro, F., Alves, A. J., Campos, L., & Oliveira, J. (2014). The effects of exercise training on arterial stiffness in coronary artery disease patients: a state-of-the-art review. Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging, 34(4), 254–262.

Oliveira, Nórton Luís, Ribeiro, F., Alves, A. J., Teixeira, M., Miranda, F., & Oliveira, J. (2013). Heart rate variability in myocardial infarction patients: Effects of exercise training. Revista Portuguesa de Cardiologia (English Edition), 32(9), 687–700.

Palatini, P., Casiglia, E., Gąsowski, J., Głuszek, J., Jankowski, P., Narkiewicz, K., … Kawecka-Jaszcz, K. (2011). Arterial stiffness, central hemodynamics, and cardiovascular risk in hypertension. Vascular Health and Risk Management, 7, 725–739.

Pierce, D. R., Doma, K., & Leicht, A. S. (2018). Acute Effects of Exercise Mode on Arterial Stiffness and Wave Reflection in Healthy Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 73.

Pinto, R., Angarten, V., Santos, V., Melo, X., & Santa-Clara, H. (2019). The effect of an expanded long-term periodization exercise training on physical fitness in patients with coronary artery disease: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 20(1), 208.

Routledge, F. S., Campbell, T. S., McFetridge-Durdle, J. A., & Bacon, S. L. (2010). Improvements in heart rate variability with exercise therapy. The Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 26(6), 303–312. Shaffer, F., McCraty, R., & Zerr, C. L. (2014). A healthy heart is not a metronome: an integrative review

of the heart’s anatomy and heart rate variability. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1040.

Simula, S., Vanninen, E., Lehto, S., Hedman, A., Pajunen, P., Syvänne, M., & Hartikainen, J. (2014). Heart rate variability associates with asymptomatic coronary atherosclerosis. Clinical Autonomic Research, 24(1), 31–37.

Skrapari, I., Tentolouris, N., Perrea, D., Bakoyiannis, C., Papazafiropoulou, A., & Katsilambros, N. (2007). Baroreflex Sensitivity in Obesity: Relationship With Cardiac Autonomic Nervous System Activity*. Obesity, 15(7), 1685–1693.

Sumner, J., Harrison, A., & Doherty, P. (2017). The effectiveness of modern cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review of recent observational studies in non-attenders versus attenders. PLOS ONE, 12(5), e0177658.

Thayer, J. F., Yamamoto, S. S., & Brosschot, J. F. (2010). The relationship of autonomic imbalance, heart rate variability and cardiovascular disease risk factors. International Journal of Cardiology, 141(2), 122–131.

Wagenseil, J. E., & Mecham, R. P. (2009). Vascular Extracellular Matrix and Arterial Mechanics. Physiological Reviews, 89(3), 957–989.

Zhang, Y., Qi, L., Xu, L., Sun, X., Liu, W., Zhou, S., … Greenwald, S. E. (2018). Effects of exercise modalities on central hemodynamics, arterial stiffness and cardiac function in cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLOS ONE, 13(7), e0200829.

III. AIMS OF THE

DISSERTATION

This dissertation intends to contribute to the scientific knowledge of the CAD pathology/diagnose/exercise prescription by applying noninvasive techniques for assessing the acute and chronic responses to exercise effort in autonomic and vascular systems exploring their connections with health in patients with CAD. In addition, new insights on how responses to exercise can help the prognostic status of those individuals are also pursued.

In our review, the acute responses of exercise may unmask the resting values of heart rate variability (HRV) and arterial stiffness (AS) but those parameters were not yet simultaneously studied and analyzed, which could contribute to a better understanding of this disease.

Furthermore, long-term exercise training potentiates several benefits to these subjects, however, the effect of exercise-based cardiovascular rehabilitation on the HRV and AS in patients with CAD is still unclear.

As such, and taking into consideration the known gaps in the scientific knowledge and understanding of the impact of the acute and chronic exercise on these variables, this dissertation will try to bring some light into this issue and uncover some of the underlying relationships, by designing suitable studies, collecting and analyzing the data with regard to:

a) The acute responses of maximal exercise test on heart rate variability and arterial stiffness in trained and untrained patients with coronary artery disease;

b) The acute responses of heart rate variability and arterial stiffness after high and moderate intensities of combined exercise bouts in trained individuals with and without coronary artery disease;

c) The effects of long-term periodized method versus non-periodized method on heart rate variability and arterial stiffness in trained patients with coronary artery disease.

SECTION B

Chapter 1.

Literature Review:

HEART RATE VARIABILITY

1

HEART RATE VARIABILITY

1.1

ANATOMY, PHYSIOLOGY AND FUNCTION OF CARDIAC

AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

Before going through the cardiac ANS, some major features about the CVS have to be pointed. The CVS is considered as a closed system, the heart (as “pump”) moves the blood through the vessels (as “pipes”) to provide nutrients and oxygen to the organs and, due to the closed system, the deoxygenated blood with lower concentrations of glucose and other nutrients, returns to the heart. The cardiac cycle happens such as: the right atrium receives deoxygenated blood from the systemic veins -> cross to the right ventricle and is pumped out through the pulmonary arteries to the lungs where the blood becomes oxygenated -> after that blood improvement, the left atrium receives via the pulmonary veins the rich blood -> which moves to the left ventricle -> and to finish the cycle, the oxygenated blood is pumped out across the semilunar valve to the systemic arteries and to body tissues to achieve the non-stop synchronization of the heart chambers, autorhythmic cardiac cells trigger and distribute action potentials as electric impulses throughout the heart muscle tissue. This cycle is controlled by the ANS, specifically by the intrinsic conduction system which creates the rhythmic pacing from a sinoatrial node located in the right atrium. This node works like a pacemaker, the depolarization of it starts the contractions of atrial muscle fibers. Soon after, the atrioventricular node works at the same way (depolarization and contraction) with the bundle of His and lastly the Purkinje fibers installed in the ventricles (Mann, Zipes, Libby, & Bonow, 2014).

Going a little deeper into the cardiac ANS, extrinsic and intrinsic cardiac ANS dates back to studies in the early 30s, as cited by Kuntz, 1958 and Van Stee, 1978. when specific receptors were discovered and plexuses which were placed on specific places along the vessels and cardiac chambers.

The recognized relationship between the nervous system and the heart is still debatable, the limitations and complexity of the cardiac-autonomic interface remains, stimulating several studies involving electrophysiology and pathology (Kapa et al., 2010). In general, the cardiac nervous system is composed of extrinsic and intrinsic components modulated by several physiologic transducers located in all the arterial heart tree (mechanical stress receptors, baroreceptors, and chemoreceptors) (Kapa & Somers, 2008). The extrinsic cardiac ANS is divided into 2 components, sympathetic and parasympathetic (vagal), largely originate in the cervical spinal cord and later in the stellate ganglion, and vagus nerve in the dorsal motor

nucleus of the medulla, respectively (Randall, et al., 1972; Smith, 1970). Sympathetic stimulation input into the heart involves pre and postganglionic fibres exactly in the sinoatrial node, atrioventricular node, and contractile tissue with some individualized heterogeneity between innervations (Randall et al., 1972; Van Stee, 1978).

Regarding intrinsic cardiac ANS, the postganglionic function of the sympathetic fibres act directly on the innervation of the myocardium and preganglionic during synapses on intrinsic cardiac ganglia (plexuses in the atria and ventricles). Atrial and ventricular plexuses are located on different points, while atrial is scattered around the atrial chamber walls, the ventricular choose the origins of major cardiac blood vessels. Cardiac ganglia may range between 700-1500 neurons, however, the neurons are not constant as ganglia and it can vary around 50% during the aging process (Armour, 1999; Hopkins et al., 2000; Pauza et al., 2000).

There is evidence showing that the activation of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves may affect the heart cells. The shortening refractoriness by sympathetic activity causes an increasing of the early potential and a delay after depolarizations, while the parasympathetic activity makes longer the refractoriness period, leading to an enhancing of the potential. (Kapa et al., 2010).

Interestingly, action potentials in cardiac muscle are 15 times longer compared to that of skeletal muscle. It is attributed to fast sodium channels that allow a quick influx of positive sodium ions, depolarizing the cells membrane. However, the heart is also composed of slow calcium channels, which are opened for long periods causing a plateau in the action potential. of cardiac muscle and a diminished outflux of potassium (Mann et al., 2014).

1.2

MECHANISMS OF CARDIAC AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

The sympathetic autonomic nervous system (SANS) differentiates from the vagal system through actuation in the body. SANS prepares the body to stressful situations, while the vagal system is permanently activated on restful and calm conditions. To complete the cascades of the ANS, some neurotransmitters are in charge to connect the neurons to the target cell across a synapse. Neurotransmitters are released into the synaptic cleft in response to action potentials. Sympathetic nervous releases norepinephrine (NE) and parasympathetic nervous releases acetylcholine (Ach) (pre and post-ganglionic neurons). Moreover, sympathetic nerves utilize long postganglionic neuron and short preganglionic neuron, on the other hand, parasympathetic nerves is inverse. The neurotransmitter needs specific receptors, two types of adrenergic

receptors are already known, β and α (1 and 2). The β1 receptors can be found in the sinoatrial and atrioventricular node and in ventricular cardiomyocytes, responsible to increase the intracellular calcium concentration and release, which causes an increase in the heart contractility and atrioventricular node conduction velocity. Notwithstanding, β2 are mainly found in vascular smooth muscle, skeletal muscle and coronary circulation, achieving vasodilation and blood perfusion. The α1 and α2 receptors (proximal and distal from sympathetic nerve terminals, respectively) are also expressed in vascular smooth muscle cells (SMC) (with low expression in cardiomyocytes) with an opposing function when compared to β2, vasoconstriction. The parasympathetic receptors (cholinergic receptors) of ACh can bind to nicotinic (located at synapses between pre- and post-ganglionic neurons of the sympathetic and parasympathetic pathways) and muscarinic (located at the end of postganglionic parasympathetic nerves and at the ends of cholinergic sympathetic fibers) receptors, with excitatory relatively slow and rapid responses, respectively. The M2 muscarinic receptors are abundant in the nodal and atrial tissue but spread out in the ventricles, its function is to slow the heart rate (HR) until sinus rhythm, diminishing the contractility of atrial cardiomyocytes and velocity of conduction similar to the atrioventricular node, resulting in reduced cardiac output. M3 muscarinic receptors are in vascular endothelium to improve the dilatation function, stimulating NO bioavailability. Thus, the receptors are responsible to control the chronotropic (heart rate), inotropic (contractility) and dromotropic (conduction velocity) functions of the CVS (Westfall & Westfall, 2006).

In addition, the sympathetic fibres also stimulate special hormones, epinephrine, and dopamine, a neurotransmitter that can stimulate the vasopressin, and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone, another hormone to control the blood pressure. Thus, neurotransmitters can activate or deactivate sympathetic activity to ask for some “help” to the hormones to balance the complex CVS. Interestingly, dopamine is mutable, can be converted into norepinephrine when is necessary to increase ino-chrono-dromotropic functions. Chromaffin cells in the adrenal medulla are responsible to produce norepinephrine and epinephrine summed to stimulate all the adrenergic receptors. When epinephrine is in low concentration, attracts more β2 receptors, leading to vasodilatation, and when its concentration is high, α1 - α2 - β1 are stimulated to achieve vasoconstriction, higher cardiac rhythm, and contractility (Hall et al., 2000).

Thus, ANS plays a major function in physiological regulation. In parts, ANS accomplishes the CVS regulation by afferent/efferent nerves that are connected directly to the heart (sympathetic terminations: myocardium; parasympathetic: sinus node, atrial myocardium, and atrioventricular node) and artery tree (Aubert, Seps, & Beckers, 2003). This ANS-heart

relationship mainly depends on baroreceptors, chemoreceptors, atrial/ventricular receptors, changes on the respiratory system, vasomotor system, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), and thermoregulatory system (Cooke et al., 1998). Sympathetic and parasympathetic pathways are responsible to determine/modify/adapt the HR according to the moment requirement (e.g. environment, breathing, physical. exercise, mental. stress, hemodynamic and metabolic changes, sleep, and posture) (Aubert, Steps, & Beckers, 2003; Cooke et al., 1998; ESC-NASPE, 1996; Rajendra Acharya et al., 2006). One of the mechanisms that increase the HR depends on the increase/maintain sympathetic activity and reduce/maintain parasympathetic activity (vagal inhibition) (Aubert et al., 2003; Rajendra Acharya et al., 2006).

1.3

FACTORS THAT INFLUENCE THE CARDIAC AUTONOMIC

NERVOUS SYSTEM AND THE STRUCTURAL AND FUNCTIONAL

CHANGES

There are several physiological evidences of acute and chronic factors that can interfere positively or negatively on the cardiac ANS structure and function. Postural changes (Klijn et al., 2015), day time (Ueno et al., 2011), sleep disorders (Palma, 2018), drug therapies (Becker, 2012), lifestyle factors (sedentary, alcohol intake, smoking, and others) are considered as risk factors to maintain the integrity of the cardiac ANS (Hu et al., 2017). All of them have been associated with unfavourable effects, achieving the same outcome, increasing sympathetic and/or decreasing parasympathetic activity (Boschloo et al., 2011; Haass & Kübler, 1997; Melo et al., 2005; Soares-Miranda et al., 2012). Regarding cardiovascular risk factors, such as aging, they are accompanied by the autonomic dysfunction, at rest, the system is relatively maintained, and however, the ability to adapt becomes weakened (Lipsitz & Novak, 2012; Parashar, Amir, Pakhare, Rathi, & Chaudhary, 2016). In this review, the focus is to show the connection between the aging process and coronary artery diseases with heart rate dysfunction, which is described in the followed topics.

1.3.1 AGING

Moreover, this long period of increased sympathetic activity contributes to high blood pressure due the unbalance of neurotransmitters which can lead to a reduction of elasticity in the vessel walls (Esler et al., 2001). Over the years, noradrenaline concentration is getting higher (Rowe & Troen, 1980), for that reason the aging and the sympathetic activity have a strong and

positive correlation (Iwase et al., 1991) This increase may be a consequence of the reduction of sensitivity of arterial baroreceptor, which is responsible to inhibit the sympathetic stimuli (Rowe & Troen, 1980). Thus, aging improves the sympathetic activity and influence inversely the vagal tone, but in contrast, the sensitivity of adrenergic receptors is lost (Korkushko et al., 1991; Lakatta, 1993). However some evidence showed that baroreceptor reflex responses during transient hypertension and hypotension are not affected by the aging process in humans (Ebert et al., 1992) and rats (Kurosawa et al., 1988). Contributing to the degenerative process, some authors bring closer the obesity factor during the aging as an associated factor which may increase sympathetic activity (Seals & Bell, 2004). The main factor that visceral fat contributes to the autonomic dysfunction may be from leptin which is sympatho-excitatory action (Haynes et al., 1997; Niijima, 1999).

1.3.2 CORONARY ARTERY DISEASES

The lifestyle and some cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity and aging are accompanied by cardiac ANS dysfunction. The chronic cardiovascular risk factor can lead to CVD and probably some emergencies with them as myocardial infarction (Hajar, 2016). Although, associations between endothelial system and other body systems have not been completely clear. Based on HRV and its relationship with CAD patients, Huikuri et al. (1999) evaluated 265 qualified patients (coronary by-pass and low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) concentrations - <1.1mmol/L) to verify the progression of this disease over a 32 months follow-up. Patients that showed a significant improvement of atherosclerosis had also a higher HRV measured by SDNN index (SDNN 97 ± 26 ms versus 116 ± 33 ms, p < 0.001).

Collaborating to the HRV-atherosclerosis relationship, a study (Li et al., 2016) with 514 CAD patients (~66yo) underwent Holter 24h, to assess the HRV, before catheterization and angiographic. Almost half of the patients had CAD confirmed by angiography (39,6%), which showed higher Framingham risk score (age; total. cholesterol; smoker; HDL; systolic blood pressure) and lower HRV according to time and frequency domain. Concluding that HRV may contribute to predict CAD.

The mechanism that involves this relationship could involve cardiac deregulation with superior sympathetic activity and reduced parasympathetic activity, leading to abnormal baroreflex-mediated HR oscillations and reduced HRV (Bergel et al., 1978; Kukreja, Datta, & Chakravarti, 1981; Palatini, 1999; Vasquez, Peotta, & Meyrelles, 2012). The high level of catecholamine from the sympathetic activity may affect vascular SMC and disturb the

lipoprotein metabolism (Dzau & Sacks, 1987; Yu et al., 1996), however further investigations need to elucidate specific biochemical cascade mechanisms.

Both systems that compose ANS, sympathetic and vagal, innervate blood vessel walls and regulate how it dilates and contracts (Sheng & Zhu, 2018). Adrenergic nerves included in sympathetic nerve fibres are installed in the muscular vessel layer. Cholinergic nerve endings are found in both endothelial and muscular layers. As already mentioned above, the M3 receptors on endothelium are connected to the formation of NO, responsible for vasodilation. To block NO bioavailability, acetylcholine is released to achieve M3 and M2 receptors, causing smooth muscle contraction (Gericke et al., 2014). Therefore, ANS imbalance may lead to an important neural risk factor for CVD. Activation of the sympathetic nervous system may generate harmful and dysfunctional structural of vascular integrity. Regardless of it, the sympathetic nervous system also interferes on blood pressure, maintaining it elevated due to peripheral vasoconstriction and kidney dysfunction (sodium and water imbalance) (Sata et al., 2018). Other chronic diseases conducted by ANS dysfunction which have atherosclerosis progression included on their trajectory are diabetes (Schroeder et al., 2005), hypertension (Fyfe-Johnson et al., 2016) and anxiety disorders (Olafiranye et al., 2011).

Scientific experimental evidence suggests that the sympathetic nervous system is extremely dangerous for all body systems, central and peripheral (Bruno et al., 2012). According to Bruno et al. (2012), some of the most relevant factors that regulate the vascular function are NO, reactive oxygen species (ROS), endothelin (ET) and the renin-angiotensin system. However, direct cause-effect information is insufficient. Angiotensin-II is capable of stimulated sympathetic activity (Grassi, 2001) and posteriorly causes hypertension linked to vasoconstriction and baroreflex imbalance (Reid, 1992). The same molecule can also stimulate vascular smooth muscle nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, increasing vascular ROS levels (Griendling, Minieri, Ollerenshaw, & Alexander, 1994). Expressive quantity of ROS, especially superoxide and superoxide hydrogen peroxide, can react to NO and transform it into peroxynitrite. This mutation has multiple negative consequences such as reduced NO bioavailability limiting the prostacyclin (PGI2) synthase and endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) activities. The eNOS inhibition is also affected by an endogenous aminoacid Asymmetricdimethylarginine which is stimulated by sympathetic nerve activity (Hirooka et al., 2011; Nishiyama et al., 2010). Another vasoconstrictor that is associated with endothelial dysfunction from the high activity of sympathetic tone, endothelin-1 (ET-1) is a mitogenic peptide which may be a result of limited NO bioavailability (Taddei et al., 1999). Thus, reduced