outubro de 2013

Ana Margarida Almeida Brandão Capelo

Processing adjectives in a survival scenario:

Analysis of congruity and comparison with

self-reference effect

Universidade do Minho

Escola de Psicologia

Dissertação de Mestrado

Mestrado Integrado em Psicologia

Área de Especialização em Psicologia Clínica e da Saúde

Trabalho realizado sob orientação do

Professor Doutor Pedro B. Albuquerque

e coorientação da

Professora Doutora Angela Bartolo

outubro de 2013

Ana Margarida Almeida Brandão Capelo

Processing adjectives in a survival scenario:

Analysis of congruity and comparison with

self-reference effect

Universidade do Minho

Escola de Psicologia

DECLARAÇÃO

Nome : Ana Margarida Almeida Brandão Capelo

Endereço electrónico: ana.margarida.capelo@gmail.com Número do Bilhete de Identidade: 137401639ZY

Título dissertação

Processing adjectives in a survival scenario: Analysis of congruity and comparison with self-reference effect

Orientador(es): Pedro B. Albuquerque

Angela Bartolo

Ano de conclusão: 2013

Designação do Mestrado: Mestrado Integrado em Psicologia, área de Especialização em psicologia Clínica e da Saúde

É AUTORIZADA A REPRODUÇÃO INTEGRAL DESTA DISSERTAÇÃO APENAS PARA EFEITOS DE INVESTIGAÇÃO, MEDIANTE DECLARAÇÃO ESCRITA DO INTERESSADO, QUE A TAL SE COMPROMETE;

Universidade do Minho, ___/___/______

II

Index

Introduction ... 7

Beyond the Survival Processing Effect: Congruity effect as a proximate mechanism. 9 The magnitude of Survival Processing effect: a comparison with the Self-Reference Effect (SRE) ... 11

Pilot study ... 12

Methods ... 12

a) Participants ... 12

b) Materials and Design ... 12

c) Procedure... 12

Results ... 13

Study 1 ... 15

Methods ... 15

a) Participants ... 15

b) Materials and Design ... 15

c) Procedure... 16

Results ... 17

a) Rating task ... 17

b) Free recall task ... 18

Discussion ... 21

Study 2 ... 22

Methods ... 23

a) Participants ... 23

b) Materials and Design ... 23

c) Procedure... 23

Results ... 24

III General Discussion ... 27

Conclusion ... 28

IV

Agradecimentos

À Escola de Psicologia e a todos os professores que me acompanharam ao longo deste percurso e pela viagem além fronteiras que me proporcionaram.

Ao Grupo de Investigação em Memória Humana pelo ambiente de extrema cooperação, abertura e envolvente discussão científica. Aos meus participantes pela disponibilidade e tempo “despendido”.

Um especial agradecimento, a si Professor Albuquerque, por todo o apoio, encorajamento, confiança e paciência. Pelo constante desafio e motivação. Por me ter vindo mostrar, durante estes 4 anos de trabalho em colaboração, quais os ingredientes essenciais para se ser um excelente profissional.

Professor Angela, thank you for your support during my stay in Lille, and for the additional motivation to accept challenges and keep my interest in research.

À minha família, por tudo e por mais ainda. Especial agradecimento aos meus pais, pelo suporte incondicional, exemplo de garra e detereminaçao. A ti mano, pela confiança, animação e por teres musicado os meus dias. Mariana, pela força e disponibilidade sem a qual tudo teria sido, sem dúvida, bem mais complicado. A todos, pela minha ausência e por me ouvirem nas mil explicações sobre o que estive, estou e vou fazer.

A ti Lucas, por não me deixares sentir a tua falta, e a ti Morim, por tudo o que foste e me ensinaste a ser durante este anos.

À Mariana, Guida, Marcelo, Ana Júlia e Nuno, por me saberem tão bem. Pelo vosso inquestionavel valor enquanto pessoas, e pelo exemplo de responabilidade, honestidade e suporte. Pelos quentes paninis au chocolat ao som da Verdes Anos.

Tati , Carlos e todos os outros que me acompanharam nesta trabalhosa recta final.

E a voces, Carol, Fu, Ana Maria, Guidinha e Sílvia amigas de sempre, por tudo que em palavras não cabe.

V

Mestrado Integrado em Psicologia da Universidade do Minho

Área de especialização em Psicologia Clínica e da Saúde

Processar adjectivos num cenário de sobrevivencia: Análise da congruência e comparação com o efeito de auto-referência

Ana Capelo

Pedro B. Albuquerque

Angela Bartolo

A Psicologia evolutiva tem sugerido que os sistemas de memória evoluíram ao longo do tempo esculpidos por pressões ambientais. Nairne, Thompson e Pandeirada (2007) forneceram suporte a esta abordagem ao encontrar um benefício mnésico no processamento de estímulos de acordo com a sua relevância para um cenário de sobrevivência ancestral - efeito do processamento baseado na sobrevivência (EPBS).

Apresentamos dois estudos que pretendem explorar, recorrendo a adjetivos como estímulos, um dos possíveis mecanismos explicativos do EPBS – o efeito de congruência; e comparar o EPBS com o efeito de auto-referência.

Globalmente os resultados revelam que o EPBS não é encontrado quando adjectivos são utilizados como estímulos. Não obtante da impossibilidade de descartar o efeito de congruência do debate acerca das bases do EPBS (Estudo 1), mostramos que o benefício mnésico promovido pelo processamento de sobrevivência se equipara ao conseguido pelo processamento auto-referente (Estudo 2). Considerações relevantes acerca do uso de adjectivos neste paradigma são discutidas, bem como possível papel do processamento auto-referente no EPBS.

Palavras-chave: Processamento baseado na sobrevivência; efeito de congruência, efeito de auto-referência

VI

Integrated Master in Psychology of University of Minho

Specialty of Clinical and Health Psychology

Processing adjectives in a survival scenario: Analysis of congruity and comparison with self-reference effect

Ana Capelo

Pedro B. Albuquerque

Angela Bartolo

Evolutionary psychologists have argued that human memory systems evolved throughout time sculpted by environmental pressures. Nairne Thompson & Pandeirada (2007) gave additional support to this approach, finding a mnemonic benefit on the encoding of stimuli regarding its relevance to an ancestral survival scenario – Survival Processing Effect (SPE).

Here we present two studies that aim to explore one of the proximate mechanisms of SPE - congruity effect; and to compare the SPE with the Self-Reference encoding strategy. We also intend to extend the study of the SPE to the use of adjectives.

Overall, results showed that SPE is not found when adjectives are used as to-be-remembered stimuli. Notwithstanding the inability to discard of congruity effect as a basis for SPE (Study 1), we found that the mnemonic consequences of survival processing are equivalent to self-reference processing (Study 2). Important considerations about the use of adjectives in this paradigm are discussed, as well the role of self in SPE.

7

Introduction

A recent line of research in the adaptive memory field arose with Nairne, Thompson, and Pandeirada (2007) who, challenged by ambitious theoretical questions - such as “Why did our memory systems evolve? Do the functional properties of memory mirror selection pressures from our ancestral past?” - developed a set of studies, which explored the mnemonic consequences of processing information in terms of its ultimate survival value.

Evolutionary psychologists argue humans are endowed with specific cognitive modules which emerged as a consequence of adaptive pressures faced by your ancestral to guarantee survival (e.g.: detecting predators - Barrett, 2005) and to reproduction (e.g.: identifying prospective mating partners - Schmitt, 2005). Empirical evidence supports the conception that ancestral remnants can be found in human cognitive performance. For example, threat superiority effect studies reveal that fear or danger related stimuli are extremely powerful at capturing human attention (e.g.:Öhman, Flykt, & Esteves, 2001 but for a discussion of phylogenetic stimuli' origin see Blanchette, 2006) . Also, studies in learning domain, revealed a “preparedness” for associate ancestrally-relevant stimuli (e.g., snakes or spiders) with aversive stimuli (Öhman & Mineka, 2003). Furthermore, in psychopathological field, evolutionary roots can be found in contents of most obsessions and the compulsive rituals (De Silva, Rachman, & Seligman, 1977).

Notwithstanding the current evidence that, over the course of evolution, memory evolved to increase its functional operation (Sherry & Schacter, 1987) and was tuned to specially process and retain fitness-relevant information, the experimental approach to this topic was not fully addressed until the studies of Nairne et al. (2007). Rather than being interested in the mnemic impact of the type of to-be-processed stimuli (high survival relevant stimuli x neutral stimuli) and following the tradition of levels of processing approach (Craik & Tulving, 1975), these authors designed a procedure, in which the mnemic benefits possibly found should not be assigned to the inherent characteristics of the stimuli, but to the processing stimuli in a survival scenario.

In the original study, participants were invited to rate the relevance of a random set of words (nouns) according to one of three orienting tasks. In the survival processing condition, participants were instructed to imagine themselves stranded in the grasslands

8 of a foreign land, alone, without any basic survival supplies, and they were asked to rate the relevance of each word to that specific scenario. The second condition was a pleasantness-rating task, in which participants were invited to judge the pleasantness of each word (known as a deep processing task with retention benefits- Einstein, McDaniel, Owen, & Coté, 1990). A third condition was designed to promote a level of schematic processing similar to the one promoted by survival scenario, highly self-relevant but not particularly survival self-relevant. Here participants were required to rate the relevance of each word in moving to a city in a foreign land. Following a short distraction task, participants were surprised by an incidental free recall task. Thereby, memory performance promoted by the processing of words in a ‘survival-related’ scenario was contrasted with proportion of retention promoted in the other conditions. Results demonstrate that participants who encoded information in the survival scenario show a clear memory advantage, setting up what has been called a survival processing effect (SPE).

Since the original study, several replications were conducted, revealing that retention benefits of survival processing are generalized across different control conditions (e.g.: Kang, McDermott, & Cohen, 2008- burglary scenario; Nairne, Pandeirada, & Thompson, 2008- vacation scenario), stimuli (e.g.: pictures- Otgaar, Smeets, & Bergen, 2010), experimental design (within vs. between-participants design- Nairne et al., 2007; Weinstein, Bugg, & Roediger, 2008) or memory task (free-recall vs. recognition Kang et al., 2008; Nairne et al., 2007). Although the interpretation of the results under the evolutionary umbrella has been strengthened by studies that show that survival processing appear when ancient grasslands (vs. modern city) are the encoding scenarios (Nairne & Pandeirada, 2010 ; Weinstein et al., 2008 but see Soderstrom & McCabe, 2011 for a different result), alternative proximate mechanisms for this phenomenon have been explored.

In the proximate mechanism’s debate, researchers explored specific characteristics of survival scenario that could be underlying the SPE. Hypothesis as arousal, novelty and media exposure of the survival scenario (Kang et al., 2008; Nairne & Pandeirada, 2010), stress elicited by the scenario (Smeets, Otgaar, Raymaekers, Peters, & Merckelbach, 2012) are been progressively rejected. Notwithstanding, it have been suggested that survival processing involves more planning (e.g.: Klein, Robertson, & Delton, 2011), is more self-relevant (e.g.:Burns, Burns, & Hwang, 2011; Cunningham, Brady-Van den Bos, Gill, & Turk, 2013; Klein, 2012), promotes more

9 elaborative processing (Kroneisen & Erdfelder, 2011; Nouchi, 2013), enhances item-specific processing relative to a moving scenario (Burns, Hart, Griffith, & Burns, 2012; Kroneisen & Erdfelder, 2011).

In that sense, efforts are being made to answer broad questions, as: What make survival processing a privileged type of information processing? In which extent this effect is resistant to procedure manipulations? And how comparable are the survival-based encoding memory benefits with the ones promoted by other encoding techniques? And despite being frequently replicated, some experimental manipulations reveal vulnerabilities of SPE that cannot be ignored (e.g.:Tse & Altarriba, 2010). For the establishment of a processing strategy in the literature, it is crucial to conduct studies that explore the impact of using different methods and stimuli, to understand the magnitude and robustness of it. Here it lies one of three main objectives of this dissertation project: a) to investigate the impact of the use of adjectives as stimuli (since, as far as we know, this paradigm was never tested with adjectives); b) to analyze one of the most pertinent explanations for the survival processing advantage – the role of congruity between stimuli and scenario; c) and, our last purpose is to establish a comparison between survival processing and a well know encoding strategy – self- reference.

Beyond the Survival Processing Effect: Congruity effect as a proximate mechanism

Butler, Kang, and Roediger III (2009) driven by Nairne et al. (2007) reports about the superior retention of items that were rated highly relevant to the survival scenario, started to investigate what was according to the authors, “briefly discussed but largely dismissed as unimportant” (p.1477), the role of congruity in the survival processing paradigm. The interpretation of SPE as a privileged encoding strategy that reflects an ancestral memory tuning would be challenged if the retention benefits appear to be dependent on inherent characteristics of the stimuli (its relevance to the scenario).

Congruity effect comes from traditional levels-of-processing experiments, in which recall is conceived as a positive function of the match between the stimuli and encoding context (e.g.:Moscovitch & Craik, 1976; Schulman, 1974). For example, if the encoding question is “Is chair an object ?”, a congruent unit between encoding question

10 and the target word is made. That fact leads to richer or more elaborate encoding, enhancing the retention probability.

Butler et al. (2009) found that controlling the congruity between stimuli– processing scenario, SPE disappear. Congruity manipulation was attained with the creation of 3 lists, with words high relevant to processing scenarios (survival list and

robbery list), and an irrelevant list to both scenarios. Results revealed that even when

the presentation of the words was blocked by list (Exp. 2) or intermixed items (Exp. 3), a congruity effect was observed within each group (i.e. participants in the robbery condition recall significantly more items of the robbery list), but surprisingly, survival processing did not promoted an overall recall advantage (which was expected in the

irrelevant list).

Challenged by this possible boundary condition of the SPE, Nairne and Pandeirada (2011) conducted an extensive study, in which SPE appear under different manipulations, for example: when a new random set of words was presented to participants (no stimuli was repeated across conditions or participants; exp.1), when only incongruent word (Exp. 2) and congruent words (Exp. 3) or both are presented (Exp. 4). Discussing the results, the authors emphasized some methodological differences between their study and Butler et al.’s experiments (e.g., proportions of congruent/incongruent stimuli processed-2/3 of Butler’s stimuli were incongruent, and the use of shorter lists).

Palmore, Garcia, Bacon, Johnson, and Kelemen (2012) using shorter (as Butler et al., 2009) balanced lists (following the argument of Nairne & Pandeirada, 2011), also found that SPE can be eliminated when congruity is manipulated. However, for the interpretation of Palmore et al.’s results methodological concerns have to be considered, since it was added a Judgment of Learning (JOLs) in the rating task, and the accidental nature of the procedure was compromised.

The incoherence found concerning the hypothesis of congruity effect as a proximate mechanism of SPE is noteworthy, and offer further avenue for research (Study 1).

11

The magnitude of Survival Processing effect: a comparison with the Self-Reference Effect (SRE)

Self-reference processing (processing information in relation to the self) is one of the most widely studied and robust encoding techniques (see Symons & Johnson, 1997 for a meta-analysis review).The SRE was firstly reported by Rogers, Kuiper, and Kirker (1977), who extended the traditional levels of processing framework to the domain of self.

Studies developed for more than three decades, contributed for establishment of SRE as an effective mnemonic strategy and endowed us understand the mechanisms through which effect is elicited. The interpretation of SRE on memory lies on the conception of self as a kind of superordinate schema that promote encoding and retrieval (Markus, 1977). More specifically, self-referencing promotes better organization in memory and elaboration, promoting relational and item-specific processing, and so a rich representation in memory (Klein & Loftus, 1988).

Nairne et al. (2007), with an autobiographical self-reference task (e.g., how easily the word brings to mind an important personal experience”), found supremacy of SPE over SRE.

However, Klein (2012), based on previous studies that investigate the role of self-reference task on SRE’s magnitude (e.g. Klein & Loftus, 1988), showed that when instructions of SR condition explicitly request episodic retrieval (“Please bring to mind an important personal experience involving each of the items presented on the next page, and then rate how easy it was to bring an experience to mind”), self-referential processing promotes recall equivalent to the one promoted in survival processing tasks.

Reviewing SRE literature, Symons and Johnson (1997) emphasized that SRE’s magnitude is influenced by self-reference task (e.g., self-descriptiveness, autobiographical retrieval,...) and stimuli (e.g., nouns, adjectives...). As trait dimensions are the most common attributes along which people judge themselves (Maki & McCaul, 1985) and a self-reference judgment (how this word describes yourself as a person?) falls into self-schema, a more elaborative processing is promoted when adjectives are used, enchancing the retention.

To fully address the comparison between SRE and SPE, the use of adjectives (and a self-descriptiveness task) seems imperative. By doing this, we will be comparing the SPE with the best privileged methodology to access SRE, which could enable us to

12 reach some empirical fundaments about the magnitude of the effect. If a supremacy of SPE over SRE is not found, a contribution to the current hypothesis about the role of self-referential processing in the survival condition could be achieved (later explored).

Pilot study

In the first study we aimed to test congruity effect as a proximate mechanism for SPE using, for the first time, adjectives as stimuli. A pilot study was conducted in order create ad-hoc adjectives lists (with different levels of congruency between stimuli and scenario).

Methods a) Participants

A total of 171 students from University of Minho (127 females; Mage = 23.32 years; SDage = .31) voluntarily took part in the experiment.

b) Materials and Design

Two sets of 96 adjectives from (Pereira, Fernandes, Soares, Comesaña, & Pereira, 2008) were submitted to a between-participants evaluation of its relevance for a survival scenario or a moving scenario. The first set was evaluated by 88 participants (N= 46 moving scenario; N= 42 survival scenario; randomly assigned), and the second set was evaluated by 83 participants (N= 41 moving scenario; N=42 survival scenario, randomly assigned).

c) Procedure

Participants received a Portuguese translation of the instructions presented by Nairne et al. (2007; see below), in which they were invited to evaluate the relevance of items to the processing scenario according a 5 points likert scale (1 - “totally irrelevant” to 5 - “totally relevant”). An individually sheet containing the to-be-rated adjectives, was given to each participant. The task had no time limit.

13

Results

Comparing the mean rating assigned by each condition to each adjective, the results of this study allowed the production of lists with controlled congruency to the scenario. To integrate the congruent list (survival list and moving list), adjectives had to be relevant to one scenario (with a mean rating higher than 3) and simultaneously not relevant to the other scenario (with a mean rating equal or lower than 3). Submitting the evaluation of 192 adjectives on this criterion, only 8 adjectives fulfilled the requirements to integrate survival list –which constrained the number of items that could compose the remaining lists. To integrate the moving list were then selected 8 items were rated with a rating greater than or equal to 3 in this condition and simultaneously evaluated with a rating of less than 3 in the survival condition. Finally for neutral list, items that were equally rated in the two conditions were selected (which the difference in the ratings assigned by the two conditions was closest to zero). Table 1 show the mean rate assigned in each scenario to the selected stimuli, and further characteristics of them.

14

Table 1. Mean Rating assigned by each condition and characteristics of each of the

15

Study 1

The aim of the study was to test the impact of congruity manipulation (between stimuli and processing scenario) on a typical survival processing paradigm using ad-hoc lists of adjectives.

As it was observed in previous studies in this domain, congruity effect was expected within processing conditions (evidenced by a significant higher recall of items from the congruent lists). Also, based on the strong empirical evidence provided by Nairne and Pandeirada (2011) against Butler et al. (2009) and Palmore et al. (2012) suggestions, we predicted an overall recall advantage in survival processing condition.

In the absence of previous research into the use of adjectives, we did not make specific predictions about the effects of this variable, but as some replications of the SRE had been made with other stimuli, we expected that it does not constrain the effect.

Methods a) Participants

A total of 60 students (46 females, Mage = 20.78 years , SDage= 3.97) from the University of Minho participated voluntarily in this study, for course credits (N=31) or without any compensation (N=29).

b) Materials and Design

The stimuli consisted of three lists of eight adjectives (24 total), with controller congruity to the scenario (cf. pilot study).

A mixed design was used, with processing scenario (survival vs. moving) manipulated between subjects (30 participants randomly assigned to each condition) and type of list (survival vs. moving vs. neutral) as a within-subject variable. The dependent variable of this study was the proportion of presented words recalled (correct recall).

16

c) Procedure

On arrival in the laboratory, participants were randomly assigned to one of the two processing conditions with the following instructions (Portuguese translation of Nairne et al., 2007):

Survival scenario. In this task we would like you to imagine that you are

stranded in the grasslands of a foreign land, without any basic survival resources. Over the next few months, you will need to find steady supplies of food and water and protect yourself from predators. We are going to show you a list of adjectives, and we would like you to rate how relevant each of these adjectives would be for you in this survival situation. Some of the personal characteristics may be relevant and others may not—it’s up to you to decide.

Moving scenario. In this task, we would like you to imagine that you are

planning to move to a new home in a foreign land. Over the next few months, you’ll need to locate and purchase a new home and transport your belongings. We are going to show you a list of adjectives, and we would like you to rate how relevant each of these adjectives would be for you in this moving scenario. Some of the personal characteristics may be relevant and others may not—it’s up to you to decide.

Data collection was performed in individual sound-proof boxes, and SuperLab 4.0.5. (Cedrus Inc., San Diego, USA) was used for the experimental design. As in the original study, the stimuli appeared one at a time, centered on the computer screen, with a limit of time of five seconds. The presentation order of stimuli was randomized for each participant.

To perform the rating task, participants were instructed to press the keyboard key that corresponded to the rating of their choice (likert 5 point-scale: 1 - “totally irrelevant” to 5 - “totally relevant”; which was displayed below each word). Response times were recorded, but if participants took more than 5000ms, the next trial started automatically, and the data of that trial was excluded. Nevertheless, such trials were rare (only 49 missing trials of 1440). To ensure that participants understood the task, five practicing trials preceded the main rating session, with a reminder of the purpose of the study at the end.

17 After the rating task, participants were involved in a short distractor task (2 minutes approximately), in which they had to memorize a sequence of 9 numbers (range between 1 and 9) that appear individually with a rate of 1 second per item. Finally, the participants were surprised with a 10 minutes free recall task and they were instructed to recall the earlier rated adjectives, in any order, on a response sheet.

Results a) Rating task

Figure 1 shows the mean rating as a function of type of list and type of processing. A within-group ANOVA revealed that participants from survival processing condition rated higher survival list than the remain lists, F(2, 58) = 37.63, p < .001, η2 = .57, moving list x survival list, p < .001; survival list x neutral list, p < .001. As well, participants from moving condition rated higher the moving list than the remains, F(2, 58) = 85.19, p < .001, η2 = .746, moving list x neutral list, p < .001, moving list x

survival list, p < .001. A 2 (processing condition) x 3 (type of list) ANOVA confirmed

these observations. There was main effect of list, F(2, 116)=25.37, p <. 001, η2=.304, in which adjectives from the moving and survival list were rated higher than adjectives from neutral list. Also, a significant interaction effect, F(2, 116) = 88.72, p <. 001, η2 =. 61, revealed that each scenario assigned higher relevance to its congruent list and similar relevance to neutral list. However, an unexpected main effect of type of processing was also found, F(1, 58)= 8.367, p = .005, η2=.126, MSurvival = 2.76 vs. MMoving = 3.04.

Figure 1. Mean rating assigned to each list in each group condition (error bars represent

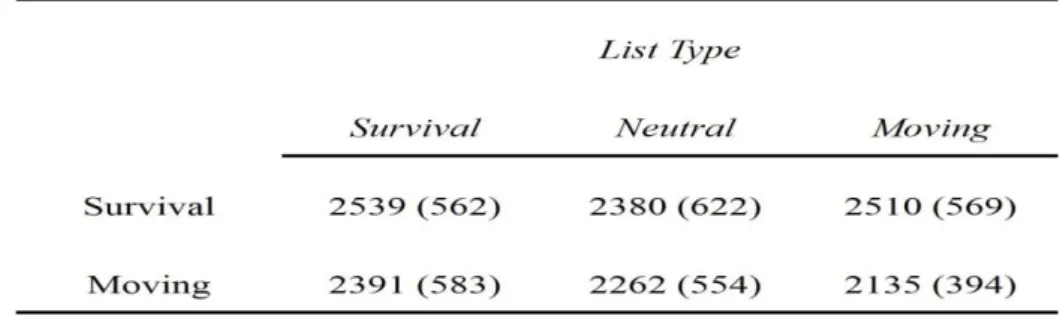

18 Table 2 shows the mean response time in each condition as function of list type. Response time analyses within each condition, revealed no differences in survival processing scenario, F(2, 58) = 2.11, p = .13, η2 = .07, however in moving scenario participants took longer time to rate items from survival list than from the moving list,

F(2, 58) = 4.14, p = .021, η2 =.13. A 2(processing condition) x 3(type of list) ANOVA, showed a main effect of list, F(2, 116) = 3.70, p = .03, η2 = .06, in which participants took significantly more time to rate items from survival list then from the moving list. Also a marginal interaction effect was found, F(2,116) = 2.705, p =.071, η2 = .045, revealing a tendency, in survival condition to take more time to rate items from moving

list than moving condition.

Table 2. Mean and standard deviations (in parentheses) response time (ms) as function

of type of list and processing condition

b) Free recall task

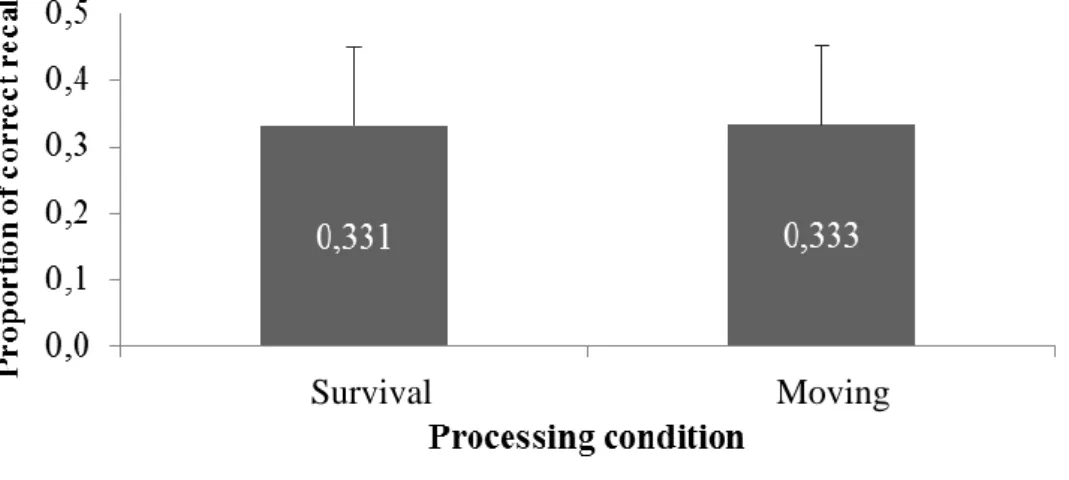

Figure 2 shows the proportion of items correctly recalled in each condition. The results showed no mnemonic advantage to the processing of adjectives in the survival scenario, t(58) = .044, p = .97, d’ = .02.

19

Figure 2. Average proportions of correct recall as a function of condition (error bars

represent the SD for each condition)

Analyses of free recall task, revealed that approximately 40% of the recalled items were intrusions - mainly words semantically related to ones presented or from the practice list. Nevertheless no difference was found in between conditions regarding the proportion of intrusions recalled, t(58) = .13, p = .90, d’ = .03, MSurvival = .41, MMoving = .40.

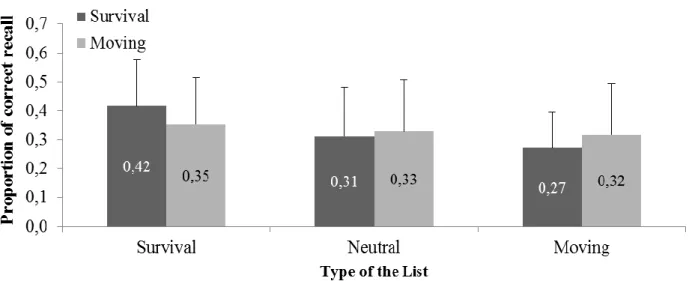

Figure 3 presented the proportion of words correctly recalled as a function of type of list and type of processing. In survival condition, a within-group ANOVA revealed tendency to recall items from the congruent list, in which 42% of the recalled items were from survival list, F(2, 58) = 4.95, p = .010, η2 = .15; moving list x survival

list, p = .01. In moving condition no difference was found in the proportion of recall per

list, F(2, 58) = .24, p = .79, η2= .01.

Additionally, the ANOVA 3 (type of list) x 2 (processing conditions), only revealed a main effect of type of list, F(2, 116) = 3.39, p = .04, η2 = .06 , moving list <

survival list, p = .02.

20 Data was further analyzed to investigate whether items that were rated as highly relevant to the scenario were better recalled. Table 3 shows the proportion recalled words as a function of rating attributed and processing scenario. Within-subjects analyzes reveal that, participants in survival scenario tend to recall more items from each a highest rating value was assigned, F(4,116)= 4.34 , p = .003, η2= .13, rating 1 < rating5, p = .04, rating3 < rating5, p = .05. In moving scenario no differences were found in the proportion of items recalled as a function of the initial rating assigned (F (4,116) = 1.35, p = .23, η2 = .04).

Table 3. Proportion of presented words recalled as a function of initial rating and type

of processing.

Figure 3. Proportion of presented words recalled as a function of processing scenario and type of

21

Discussion

In Study 1, we failed to find the SPE (characterized by the higher retention promoted by survival processing superior relative to moving processing).

The absence of a clear congruity effect within each processing scenario was unexpected. Previous studies that explore the role of congruity between stimuli and processing condition as a proximate mechanism of SPE, consistently found a congruity effect within each condition (higher proportion of recall of items from the congruent list). Nevertheless, Nairne et al.’s (2011) findings concerning the widespread memory benefits of the survival scenario, even for items with low relevance, were not supported by Butler et al. (2009) and Palmore et al. (2012).In the present study, the failure to find the mnemonic advantage in the survival processing condition could not be interpreted as consequence of congruity manipulation, since non congruity effect were found in moving scenario.

One reasonable explanation for the absence of congruity effect could be related to what we defined as congruent/incongruent lists. Unfortunately, and contrarily to Butler’s lists (Mean rating of robbery list –MRobbery scenario = 4.4; MSurvival Scenario = 1.4;

survival list– MRobbery scenario = 1.3; M Survival Scenario = 4.1), our stimuli were not rated with extreme values on each condition, constraining distinctiveness promoted in its processing. Additionally the main effect of survival list in recall and in RT, suggested that this list could have some features that increased its storable probability (see General Discussion). Aware of that as possible limitation to explore the role of congruency in this paradigm, analysis of proportion of words correctly recalled as a function of initial rating were conducted. However, only in Survival condition words given a higher rating during the processing task were better recalled on free recall task (fitting with congruity effect´s predictions).

One possible interpretation for the similar recall proportion in the two conditions could be that the use of adjectives affected the type of processing promoted in the control condition- moving condition. Familiarity or previous experience with the scenario described in the moving condition, are factors that along with the use of adjectives could have acted in the promotion of an unexpected self-reference encoding (as autobiographical task). If it was the case, we may have decreased the self-relevance difference that some authors have claimed to exist between the scenario of survival and

22 control scenarios. That approach for SPE interpretation, began with Burns et al. (2011) who speculated that survival scenario could promote more self-referential, and consequently a more elaborative processing than control conditions. Klein (2012) and Cunningham et al. (2013) also provided some evidence in favor of this explanation, emphasizing the role of self in SPE (but see Kang et al., 2008; Weinstein et al., 2008).

Considering the empirical evidence that self-relevant stimuli easily attract one's attention (Bargh, 1982) and the impact of personality schemas on memory performance (e.g.:Cantor & Mischel, 1977) we are unable provide a definitive interpretation concerning the influence of adjectives in this paradigm, and more specifically, on the strategy used by participants in the recall task.

Study 2

The main purpose of Study 2 was to compare two encoding processes that are known in the literature as boosters of mnemic benefits, either as a consequence of processing of stimuli in a survival scenario (SPE), or in relation to self (SRE).

The supremacy of SPE over SRE found by Nairne et al. (2007) was no observed in Klein (2012). Using a more privileged Self-Referent task but same stimuli (nouns), Klein (2012) found no difference between SRE and SPE

This experiment was pioneer in the establishment of the comparison between SRE and SPE with adjectives as stimuli (privileged manipulation for SRE magnitude, according to Symons & Johnson, 1997) . We predicted, as in Klein (2012), at least an attenuation of the difference found by Nairne et al. (2007) in the proportion of recall promoted by the two conditions.

As a tentative approach to hypotheses raised in study 1 concerning the impact of adjectives as to-be-processed stimuli, two additional tasks (described below) were added to the typical survival processing paradigm.

23

Methods a) Participants

A group of 82 (73 females, Mage= 21.94, SDage= 6.07) undergraduate students voluntarily participated in the experiment in exchange for course credits (N = 70) or without any compensation.

b) Materials and Design

The stimuli were the same 24 adjectives of study 1. A between-subject design was used, in which participants were randomly assigned to the processing conditions (self-reference processing, N = 41 vs. survival processing, N = 41). The dependent variable was the proportion of presented words recalled (correct recall).

c) Procedure

On arrival in the laboratory, participants were randomly assigned to one of the two processing conditions. Participants assigned to the survival condition were instructed as in Study 1, and participants from self-reference condition received the following instructions:

Self–reference condition. We are going to show you a list of adjectives, and we

would like you to rate how well each adjective describes you as a person.

Data collection was conducted individually in soundproof cabins or in the Human Cognition Lab UMinho computers’ room (4 participants maximum).

Procedure was the same of Study1 but at the end of the free recall all the participants were asked to perform two simple tasks (randomized order). Participants from self-reference condition had to remember the rating given to each recalled word (retrospective rating task), and evaluate how relevant those items could be to the survival scenario. Participants from survival condition were also invited to performed a retrospective rating task, and had to evaluated how well each recalled adjective describe themselves (with the same 5 points likert scale).

24

Results

Response time analysis of the rating task show no difference between the two groups, t(80) = 1.78, p = .079, d’ = . 39, MSelf-Reference = 1912 ms, MSurvival = 2082 ms.

A significant difference was found between the two processing conditions regarding the mean rating assigned to the overall stimuli, t(80) = 2.45, p = .016, d’ = .54, MSelf-Reference = 3.01, MSurvival = 2.80. However, no difference was found between conditions concerning the mean rating assigned to the recalled stimuli, t(41) = 1.47, p = .145, MSelf-Reference = 3.09, MSurvival = 2.92.

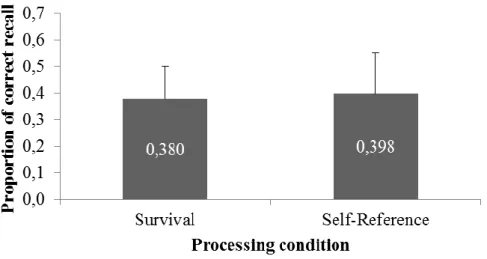

Figure 4 shows the mean correct recall for the two processing conditions. As it was predicted, the between the two processing conditions regarding the proportion of correct recall– t (80) = .60, p = .57, d’ = .13.

The proportion of intrusions recalled was noteworthy in both conditions but higher in Survival condition, t(80) = 2.01, p = .05, d’ = .44, MSelf Reference = .32, MSurvival = . 40.

Figure 4. Proportion of presented words recalled as a function of processing condition

(error bars represent the SD for each condition)

In the performance of “retrospective recall rating task”, no difference was found between conditions concerning the proportion of hits (ratings correctly remembered;

t(80) = .968, p = .336, d’ = .21, MSelf-Reference = .60, MSurvival = .65).

The performance in “retrospective rating task” was compared to the second additional task (in which participants from survival processing had to evaluate

self-25 relevance of the recalled items, and participants from self-reference processing had to evaluate the survival relevance of it). In Survival processing, no difference was found between recalled rating and the self-referent evaluation of those items, t(40) = .43, p =.67, d’ = .06. In addition, we found a significant positive correlation between those variables, r = .56, p <. 001. In self-reference condition a difference was found between the recalled rating and the survival relevance assigned that same items, t(40) = 3.73, p <. 001, d’ = .52, Mrecalled rating = 3.20, Msurvival relevance-posterior task =2.62.

Discussion

The present study compared the magnitude of two encoding strategies on a free recall task (self-reference and survival processing). The mnemonic benefits promoted by survival processing proved to be higher (Nairne et al., 2007) or equivalent (Klein et al., 2012) of the promoted by self-reference processing, in respect to the encoding of nouns. Taking into account the enhanced effect of self–reference when adjectives are the to-be-processed stimuli (Symons & Johnson, 1989), a higher proportion of recall in self-reference condition was hypothesized. That prediction did not found support in this study.

Unexpectedly, the proportion of correct recall promoted by the two encoding conditions (approximately .40), were equivalent or even less then proportion of recall promoted by other control tasks reported in other studies (e.g., .55 - Vacation scenario, Nairne & Pandeirada, 2008; .46 -Moving scenario, Nairne et al., 2007; and .41 - Burglary scenario, Kang et al., 2008). Taking that into consideration, along with the huge amount of intrusions recalled, we speculated that some inherent features of the stimuli or methodological factors could be affecting the results, constraining the comparison between the two encoding strategy.

The failure to find recall advantage of self-reference condition over survival processing condition seems to be in favor of recent approaches to SPE, which suggested that survival processing enhances the processing of both item-specific and relational information (Burns et al., 2011) and promoted more elaboration (Kroneisen & Erdfelder, 2011; Nouchi, 2013). Nouchi (2013), based on the elaboration hypothesis, suggested that the beneficial effect of the survival processing would only occur when

26 participants produce a higher level of elaboration. As the mnemic effect achieved by survival processing was here equivalent to the one promoted by an encoding strategy known for increase both item-specific and relational processing (Klein & Loftus, 1988; Symons & Johnson, 1997), this study could give an indirect contribution to this debate. Notwithstanding, the procedure was not designed to direct addressed this issue and, unfortunately, the higher proportions of intrusions prevented the application of measures such as Ajusted Ratio of Clustering (ARC; measure the degree of categorical clustering, Burns, 2006), that would allowed us to directly compare the type of processing promoted in condition.

The higher amount of intrusions elicited by survival processing, could suggest that survival processing task lead to a type of processing that was less efficient on the monitoring of the presented items. This interpretation, is supported by Otgaar and Smeets (2010) results with DRM-lists, which revealed that survival processing not only enriches true recall but simultaneously increase false memories. However, no difference was found between the two conditions on the “prospective recall rating task” (participants could accurately recall the rating value assigned to 60% of the recalled items). This suggested that memory accuracy for specific features (rating) of the processed items were equivalent in the two conditions.

The results concerning the performance of Survival Processing condition in the final tasks which reveal:(a) no difference in the rating assigned to the survival relevance of the items correctly recalled and its self-relevance evaluation; and (b) significant positive correlation between those variables, give support to recent studies that argue for the role of self in survival condition (Burns et al. 2012; Klein 2012; Cunningham et al 2012). In other words, these data suggest that participants took into consideration not only the relevance to the survival processing scenario, but maybe they also adopt a self-reference strategy to retrieve items. This fits nicely on the argument supported by those authors, that self-referential thoughts appear during performance of survival scenarios, and self play a crucial role in survival processing.

27

General Discussion

The present research represents a pioneer attempt to spread the survival processing paradigm to the use of adjectives as to-be-processed stimuli, aiming to explore the role of congruity as proximate mechanism of survival processing paradigm (Study 1), and to assess the mnemonic benefits of survival processing against the well-known self-reference encoding strategy (Study 2).

Surprisingly in Study 1 the standard SPE was not observed and neither congruity effect within the processing condition. Although the ad-hoc lists (pilot study) were rated as it was expected, the proportion of recall per list only revealed a tendency to recall the items from the congruent list in the survival condition. This fact did not allow to discard the congruity effect as a proximate mechanism of SPE.

Study 2 sought to investigate the mnemonic advantage of SPE over the SRE. As Klein (2012), no difference was found between the recall promoted by the two encoding tasks.

Together these studies, give important insights concerning the impact of the stimuli’ nature manipulation on this procedure. Considering previous studies, two unexpected findings were observed in both studies: a relatively low proportion of correct recall and a large proportion of intrusions. In that vein, we hypothesized that the use of adjectives instead of nouns (most used stimuli) could have increased the memory task difficulty. Pursuing that possibility, we conducted a subsequent experiment in which participants were instructed to memorize 24 nouns (from Nairne et al., 2007; N = 25) or 24 adjectives (N = 30), that appear one at a time for 1500ms. Results from a free recall task (3min.) revealed that nouns are more easily retrievable, (t(53) = 2.69, p = .01, d’ = .73; Mnouns = .44, Madjectives = .34). The proportion of intrusions promoted by the processing of adjectives was higher, but not significantly different from the one promoted by nouns (t(53) = 1.53, p = 0.18, d = .36; Madjectives = .11, Mnouns = .07). Moreover, based on a later protocol analysis conducted in both studies, we speculated that not only the stimuli could have had an adverse impact on our results, as also the paradigm applied – characterized for a 10 min free recall task. The hypothesis that participants, unable to retrieve items that were presented started to use wider criterion for the recall, was supported by the clear increase on the number of intrusions recalled in the last quartiles of recall.

28 Some benefits could be highlighted from the use of the same stimuli across the two experiments. On the one hand it gave us additional evidence that the ad-hoc lists were not able to elicit the congruity effect (later analyses of Study 2, revealed that survival condition did not produce more recall from the congruent list). On the other hand, it allowed us to rule out the hypothesis raised in study 1 that the survival list were endowed with some features that increase its storable probability (since later analyses in Study 2 revealed no difference in recall of neutral list and survival list). This data give empirical support to the methodological considerations (regarding the list contents) emphasized in Study’s 1 discussion.

The similarities in the performance between moving condition and self-reference across the studies reinforce the hypothesis raised regarding stimuli and encoding task promoted in moving scenario. It was suggested that those factors could have acted together, resulting in a self-referent encoding of information in moving condition. In this sense, the absence of SPE in both studies is not surprising, and found support in previous studies that suggested that survival relevance judgment task could be interpreted as a self-referential processing (Burns et al., 2012; Klein, 2012; Cunningham et al., 2012). In that approach, mnemonic benefits of survival processing are, at least in part, see as consequence of a higher self-referential processing in survival scenario, in comparison to the control conditions. Cunningham et al. (2012) go beyond on this proposal, and showed that self is a critical ingredient of SPE, since the encoding information in the context of survival by other people do not to elicit the standard memory advantage. In that sense, Klein’s (2012) comment that “elimination of self-referential processing from consideration of potential survival-relevant mechanisms may be premature” (pp. 1241) found support in the present study.

Conclusion

The two main questions asked in the current studies (is congruency between stimuli-scenario an underlying proximate mechanism of the SPE?; and are the mnemonic effects of SPE comparable to those promoted by SRE?) proved to be difficult to answer.

29 Despite the impossibility to fully addressed congruity effects as a proximal mechanism for SPE, an interesting discussion concerning the role of adjectives in the type of processing promoted in each condition was raised.

Along with previous research (e.g.: Tse & Altarriba, 2010), the overall results rise some constraints for the definition of SPE as an effect independent of experimental manipulations. Notwithstanding, we showed that survival processing of adjectives could be as mnemic efficient as one of the highest encoding strategies found in memory research (self-reference processing).

Additional research is required, either for investigation of the role of to-be-processed stimuli’ nature, either for the achievement of a thorough comparison with Self-Reference effect (with the use of different adjectives).

References

Bargh, J. A. (1982). Attention and automaticity in the processing of self-relevant information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 425-436. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.43.3.425

Barrett, H. C. (2005). Adaptations to predators and prey. In D. M. Buss (Ed.), The

handbook of evolutionary psychology (pp. 200-223). New Jersey: John Wiley &

Sons, Inc., Hoboken.

Blanchette, I. (2006). Snakes, spiders, guns, and syringes: How specific are evolutionary constraints on the detection of threatening stimuli? The Quarterly

Journal of Experimental Psychology, 59(8), 1484-1504. doi: 10.1080/02724980543000204

Burns, D. J. (2006). ssessing distinctiveness: measures of item-specific and relational processing. In R. R. H. J. B. Worthen (Ed.), Distinctiveness and memory (pp. 109 - 130). New York: Oxford University Press.

Burns, D. J., Burns, S. A., & Hwang, A. J. (2011). Adaptive memory: Determining the proximate mechanisms responsible for the memorial advantages of survival processing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and

30 Burns, D. J., Hart, J., Griffith, S. E., & Burns, A. D. (2012). Adaptive memory: The survival scenario enhances item-specific processing relative to a moving scenario. Memory, 21(6), 695-706. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2012.752506

Butler, A. C., Kang, S. H. K., & Roediger III, H. L. (2009). Congruity effects between materials and processing tasks in the survival processing paradigm. Journal of

Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35(6), 1477-1486.

doi: 10.1037/a0017024

Cantor, N., & Mischel, W. (1977). Traits as prototypes: Effects on recognition memory.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(1), 38-48. doi:

10.1037/0022-3514.35.1.38

Craik, F. I. M., & Tulving, E. (1975). Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 104(3), 268-294. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.104.3.268

Cunningham, S. J., Brady-Van den Bos, M., Gill, L., & Turk, D. J. (2013). Survival of the selfish: Contrasting self-referential and survival-based encoding.

Consciousness and Cognition, 22(1), 237-244. doi:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2012.12.005

De Silva, P., Rachman, S., & Seligman, M. E. P. (1977). Prepared phobias and obsessions: Therapeutic outcome. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 15(1), 65-77. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(77)90089-4

Einstein, G. O., McDaniel, M. A., Owen, P. D., & Coté, N. C. (1990). Encoding and recall of texts: The importance of material appropriate processing. Journal of

Memory and Language, 29(5), 566-581. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0749-596X(90)90052-2

Kang, S. K., McDermott, K., & Cohen, S. (2008). The mnemonic advantage of processing fitness-relevant information. Memory & Cognition, 36(6), 1151-1156. doi: 10.3758/MC.36.6.1151

Klein, S. B. (2012). A role for self-referential processing in tasks requiring participants to imagine survival on the savannah. Journal of Experimental Psychology:

Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 38(5), 1234-1242. doi: 10.1037/a0027636

Klein, S. B., & Loftus, J. (1988). The nature of self-referent encoding: The contributions of elaborative and organizational processes. Journal of Personality

31 Klein, S. B., Robertson, T. E., & Delton, A. W. (2011). The future-orientation of memory: Planning as a key component mediating the high levels of recall found with survival processing. Memory, 19(2), 121-139. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2010.537827

Kroneisen, M., & Erdfelder, E. (2011). On the plasticity of the survival processing effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 37(6), 1553-1562. doi: 10.1037/a0024493

Maki, R. H., & McCaul, K. D. (1985). The effects of self-reference versus other reference on the recall of traits and nouns. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 23(3), 169-172.

Markus, H. (1977). Self-schemata and processing information about the self. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 35(2), 63-78. doi:

10.1037/0022-3514.35.2.63

Moscovitch, M., & Craik, F. I. M. (1976). Depth of processing, retrieval cues, and uniqueness of encoding as factors in recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and

Verbal Behavior, 15(4), 447-458. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(76)90040-2

Nairne, J. S., & Pandeirada, J. N. S. (2010). Adaptive memory: Ancestral priorities and the mnemonic value of survival processing. Cognitive Psychology, 61(1), 1-22. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cogpsych.2010.01.005

Nairne, J. S., & Pandeirada, J. N. S. (2011). Congruity effects in the survival processing paradigm. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and

Cognition, 37(2), 539-549. doi: 10.1037/a0021960

Nairne, J. S., Pandeirada, J. N. S., & Thompson, S. R. (2008). Adaptive Memory: The Comparative Value of Survival Processing. Psychological Science, 19(2), 176-180. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02064.x

Nairne, J. S., Thompson, S. R., & Pandeirada, J. N. S. (2007). Adaptive memory: Survival processing enhances retention. Journal of Experimental Psychology:

Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 33(2), 263-273. doi:

10.1037/0278-7393.33.2.263

Nouchi, R. U. I. (2013). Can the memory enhancement of the survival judgment task be explained by the elaboration hypothesis?: Evidence from a memory load paradigm1. Japanese Psychological Research, 55(1), 58-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5884.2012.00531.x

32 Öhman, A., Flykt, A., & Esteves, F. (2001). Emotion drives attention: Detecting the snake in the grass. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(3), 466-478. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.130.3.466

Öhman, A., & Mineka, S. (2003). The Malicious Serpent: Snakes as a Prototypical Stimulus for an Evolved Module of Fear. Current Directions in Psychological

Science, 12(1), 5-9. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.01211

Otgaar, H., & Smeets, T. (2010). Adaptive memory: Survival processing increases both true and false memory in adults and children. Journal of Experimental

Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 36(4), 1010-1016. doi:

10.1037/a0019402

Otgaar, H., Smeets, T., & Bergen, S. (2010). Picturing survival memories: Enhanced memory after fitness-relevant processing occurs for verbal and visual stimuli.

Memory & Cognition, 38(1), 23-28. doi: 10.3758/MC.38.1.23

Palmore, C., Garcia, A., Bacon, L. P., Johnson, C., & Kelemen, W. (2012). Congruity influences memory and judgments of learning during survival processing.

Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19(1), 119-125. doi:

10.3758/s13423-011-0186-6

Pereira, A., Fernandes, E., Soares, A. P., Comesaña, M., & Pereira, E. (2008, 02-04 October). Normas Afectivas para Palavras Portuguesas: Resultados do estudo

piloto de adaptação da Affective Norms for English Words (ANEW) para o Português Europeu (PE). Paper presented at the XIII Congresso Internacional

Avaliação Psicológica: Formas e Contextos Braga, Portugal.

Rogers, T. B., Kuiper, N. A., & Kirker, W. S. (1977). Self-reference and the encoding of personal information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(9), 677-688. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.35.9.677

Schmitt, D. P. (2005). Fundamentals of human mating strategies. In D. M. Buss (Ed.),

The handbook of evolutionary psychology (pp. 258-291). New Jersey: John

Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken.

Schulman, A. (1974). Memory for words recently classified. Memory & Cognition, 2(1), 47-52. doi: 10.3758/BF03197491

Sherry, D. F., & Schacter, D. L. (1987). The evolution of multiple memory systems.

33 Smeets, T., Otgaar, H., Raymaekers, L., Peters, M. V., & Merckelbach, H. (2012). Survival processing in times of stress. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 19(1), 113-118. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-0180-z

Soderstrom, N., & McCabe, D. (2011). Are survival processing memory advantages based on ancestral priorities? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18(3), 564-569. doi: 10.3758/s13423-011-0060-6

Symons, C. S., & Johnson, B. T. (1997). The self-reference effect in memory: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 371-394. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.371

Tse, C.-S., & Altarriba, J. (2010). Does survival processing enhance implicit memory?

Memory & Cognition, 38(8), 1110-1121. doi: 10.3758/MC.38.8.1110

Weinstein, Y., Bugg, J., & Roediger, H. (2008). Can the survival recall advantage be explained by basic memory processes? Memory & Cognition, 36(5), 913-919. doi: 10.3758/MC.36.5.913