w w w . r e u m a t o l o g i a . c o m . b r

REVISTA

BRASILEIRA

DE

REUMATOLOGIA

Original

article

Polymorphisms

in

NAT2

(N-acetyltransferase

2)

gene

in

patients

with

systemic

lupus

erythematosus

Elaine

Cristina

Lima

dos

Santos

a,

Amanda

Chaves

Pinto

a,

Evandro

Mendes

Klumb

b,

Jacyara

Maria

Brito

Macedo

a,∗aUniversidadedoEstadodoRiodeJaneiro(UERJ),DepartamentodeBioquímica,RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil

bUniversidadedoEstadodoRiodeJaneiro(UERJ),DisciplinadeReumatologia,RiodeJaneiro,RJ,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory: Received10June2015 Accepted23July2016

Availableonline25October2016

Keywords:

Systemiclupuserythematosus N-acetyltransferase2

Geneticpolymorphism Acetylatorphenotype Clinicalphenotypes

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Objective:ToinvestigatepotentialassociationsoffoursubstitutionsinNAT2geneandof acetylatorphenotypeofNAT2withsystemiclupuserythematosus(SLE)andclinical phen-otypes.

Methods:Molecular analysis of 481C>T, 590G>A, 857G>A, and 191G>A substitutions in theNAT2genewasperformedbypolymerasechainreaction-restrictionfragmentlength polymorphism(PCR-RFLP)technique,fromDNAextractedfromperipheralbloodsamples obtainedfrompatientswithSLE(n=91)andcontrols(n=97).

Results and conclusions:The 857GA genotypewas moreprevalent among nonwhite SLE patients(OR=4.01,95%CI=1.18–13.59).The481Talleleshowedapositiveassociationwith hematologicaldisordersthatinvolveautoimmunemechanisms,specificallyautoimmune hemolyticanemiaorautoimmunethrombocytopenia(OR=1.97;95%CI=1.01–3.81).

©2016ElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Polimorfismos

no

gene

NAT2

(N-acetiltransferase

2)

em

pacientes

com

lúpus

eritematoso

sistêmico

Palavras-chave:

Lúpuseritematososistêmico N-acetiltransferase2 Polimorfismogenético Fenótipoacetilador Fenótiposclínicos

r

e

s

u

m

o

Objetivo:Investigar potenciais associac¸ões de quatro substituic¸ões do gene NAT2 (N-acetiltransferase2)edofenótipoacetiladordeNAT2comolúpuseritematososistêmico (LES)eosfenótiposclínicos.

Métodos:Aanálisemoleculardassubstituic¸ões481C>T,590G>A,857G>Ae191G>Adogene NAT2foifeitacomatécnicadePCR-RFLP,usandoDNAextraídodeamostrasdesangue periféricoobtidasdepacientescomLES(n=91)econtroles(n=97).

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mails:jacyara@uerj.br,jacyarauerj@gmail.com(J.M.Macedo).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbre.2016.09.015

Resultadoseconclusões: Ogenótipo857GAfoimaisprevalenteentrepacientescomLESnão brancas(OR=4,01,IC95%=1,18-13,59).Oalelo481Tapresentouassociac¸ãopositivacomas alterac¸õeshematológicasqueenvolvemmecanismosautoimunes,especificamenteanemia hemolíticaautoimuneoutrombocitopeniaautoimune(OR=1,97;IC95%=1,01-3,81).

©2016ElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCC BY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune, chronicandsystemicsyndrome.Theinvolvementofvarious tissuesandorgansistheresultofchronicinflammatory pro-cesses generatedby the depositionof immunecomplexes, resulting from an increased production of autoantibodies. AlthoughtheetiologyofSLEisnotfullyunderstood,studies pointtoacomplexinterplaybetweengeneticand environ-mentaldeterminants.1Ultravioletradiation,drugs,infectious

agents, smoking, and various chemical agents have been describedaspotentialriskfactorsforthisdisease.2Studiesin

differentpopulationshaveshownthatsmokinghabitshave apositiveassociationwithSLE,withoddsratiosbetween1.6 and6.6.2–7InadditiontoinfluencingthedevelopmentofSLE,

thesmokinghabithasalsobeenlinkedtothemaintenance ofdiseaseactivityandtoalowerresponsetotreatmentwith antimalarialdrugs.4,8

Theassociationbetweengeneticfactorsandlupus, espe-ciallyhydralazine-inducedlupus,wasfirstassessedin1970. ArelationshipbetweenN-acetyltransferase2enzyme(NAT2), capableofacetylatingthedrug,andlupuswasobserved,with a greater proportion of slow acetylator phenotype among patientswiththedisease.9 Alowercumulativedoseof

pro-cainamidewasalsoabletoinducelupusinpatientswithslow acetylatorphenotypewhencomparedtopatients withfast acetylatorphenotype.10Inanotherstudy,inwhichthe

smok-ing habit and the phenotypeofNAT2 enzyme,involved in theacetylationofcigarettesmokecomponents,were consid-ered,thehigherrisk(2.26times)developingofSLEattributed tosmokersversusnonsmokerswasevenhigher(6.44times) whentheslowphenotypeofNAT2enzymewasobserved.2

The N-acetyltransferase enzymes (NATs) participate in the second phase of metabolism of xenobiotics, and the acetylationreactioncanoccurbytwodistinctpathways:by O-acetylation,aftertheactionofthefirst-phaseenzymeP450 (CYP450),andbyN-acetylation,whentheenzymeactsonthe compoundinaprevioussteptothe actionofCYP450.Both pathwaysmayresultintheformationofaDNAadduct.11

There are two isoforms of human N-acetyltransferase enzymes,NAT1and NAT2, which are differently expressed according to the tissue and have specificity for differ-entsubstrates.11–13 Acetylationofaromaticcompoundsand

heterocyclic amines, such as 4-aminobiphenyl, present in cigarettesmoke,14throughthetransferofacetylgroupofa

moleculeofacetyl-CoAtothefree-aminogroupofthe com-pound,ispreferablypromotedbyNAT2.14

TheNAT2isoform is encodedbythe NAT2 gene,which islocatedonchromosome8(8p22),together withtheNAT1 gene and the pseudogene NATP. The NAT2 gene is highly

polymorphicandthediversityofthedescribedallelesresults from thecombination ofpointmutationsofselectedbases (SNPs–singlenucleotidepolymorphisms).15Thephenotype

of the enzymecan bedetermined by existing SNPs in the coding regionofthe gene,whichinfluencestheaffinityfor the substrate, the catalytic activity and/or stability of the resultingprotein.16Amongthenucleotidechangescommonly

used in order to infer the acetylator phenotype of NAT2, 481C>T(rs1799929),590G>A(rs1799930),857G>A(rs1799931), and191G>A(rs1801279)standout.2,17,18

Duetotheimportanceofthetopicinquestionandthelack ofBrazilianresearch,inthisstudyweperformedan evalua-tion ofthepresenceoffoursubstitutionsintheNAT2gene (481C>T,590G>A,857G>Aand191G>A)andthephenotypeof NAT2enzymeinpatientswithsystemiclupuserythematosus residentsinthecityofRiodeJaneiro.Ourstudypopulation wasstratifiedaccordingtosmokingstatusandethnic charac-teristics.Someclinicalfeaturesofthediseasewerealsotaken intoaccountinouranalysis.

Materials

and

methods

Studypopulation

Thestudypopulationwasselectedfromagroupofwomen participatinginapreviousstudy,whichsequentiallyincluded SLEpatients(accordingtotheAmericanCollegeof Rheuma-tology classification criteria), regularly followed in the RheumatologyUnit,UERJ,andwomenwithoutlupuswhohad attendedforroutinegynecologicalcareinthesameuniversity (UERJ).19,20

Clinical and socio-demographicaspects, including infor-mation on race/ethnicity of the female participant and of their parents, by self-declaration, and smoking habits were obtainedbyapplyingasemi-structuredquestionnaire. Patients and controlswere classified aswhite-colored sub-jectswhentheindividualandhisparentswerewhite-colored byself-declaration,andasnonwhite-colorediftheindividual and/oratleastoneofherparentswasbrown-orblack-colored byself-declaration.Specificclinicaldatawereobtainedfrom medicalchartreview.

TheprojectwasapprovedbytheResearchEthics Commit-teeofHUPE/UERJ(HUPE/UERJ#321and#909),andallpatients were includedonlyaftersigninganinformedconsentform previouslyapproved.

MolecularanalysisofpolymorphismsinNAT2

481C>T, 590G>A, 857G>A and 191G>A in the NAT2 gene was carried out with the use of PCR-RFLP (Polymerase ChainReaction-RestrictionFragmentLengthPolymorphism) technique,accordingtoHuangetal.,17withsome

modifica-tions.Amplification ofgenomic DNA was performedusing the following primers: 5′-GGAACAAATTGGACTTGG-3′ and 5′-TCTAGCATGAATCACTCTGC-3′ (Life Technologies®). After

amplification, aliquots ofPCR productwere digested sepa-ratelywiththerestrictionenzymesKpnI(481C>T)andBamHI (590G>A), followed by electrophoretic analysis in agarose gel,and withMspI(857G>A) andTaqI(191G>A), followedby analysis by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. After elec-trophoresis,thegelswerestainedwithethidiumbromideand theproductsofdigestionwerevisualizedunderUVlight.To evaluatethereproducibilityofthetechnique,10%ofsamples wererandomlyselectedandreevaluated.

Phenotypicclassification

In this study, the bimodal classification,17 in which

inter-mediate and fast phenotypes are grouped into a single category,wasused. Thus,thepresenceand absenceofthe WTallele (absenceofthe four NAT2substitutions, 481C>T, 590G>A,857G>A,and191G>A)definethefastandslow phen-otypes,respectively.Inpractice,sampleslackingoneofthe fourchanges,or samplesheterozygousforonlyoneofthe substitutions,wereconsideredashavingfastacetylator phen-otypes.Ontheotherhand,thehomozygoussamplesinonly oneof the substitutions were classified as slow acetylator phenotype.Thedefinitionofphenotypesofsampleshaving twoormorechangeshasbeenmadeconsideringallpossible combinationsofallelesandverifyingtheirfrequencyinour population,accordingtothehaplotypes’estimationanalysis carriedoutbasedonthefrequenciesofindividual substitut-ions,asdescribedlater.Combinationscontainingatleastone rarehaplotypewithanestimatedfrequency<0.01were con-sideredunlikelyandwerediscarded.

Thesampleswithoutaresultforoneofthefour substitut-ionsanalyzedwhosemissinggenotypewouldnotinterferein thephenotypedefinedbytheotherthreesubstitutionswere includedinthestudy.

Statisticalanalysis

Student’st-testwasusedtoanalyzethedifferencesbetween meansandstandarddeviationsandwasperformedusingthe GraphPadPrism software version 6.05 (GraphPadSoftware, Inc.,SanDiego,CA).

The study population was tested for deviations from Hardy–WeinbergusingtheChi-squaredtest(2),assuminga

degreeoffreedom=1,withtheuseofSNPStatssoftware (Insti-tutCatalàd’Oncologia,Barcelona,Spain).22

Thedifferencesbetweengenotypeandallelefrequencies of groups of cases and controls were evaluated by the 2 test or Fisher’s exact test. The odds ratios (OR) and confi-denceintervals(95%CI)weredeterminedinordertoestimate the magnitudeof the association betweenNAT2 substitut-ions with the presence of systemic lupus erythematosus, using,wherepossible,co-dominant,dominant,andrecessive geneticmodels.Themostfrequentalleleandthehomozygous

genotype of this allele were considered as references. These tests were performed using GraphPad Prism ver-sion 6.05 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Theanalysesofinteractionsbetweengenotypesor phen-otypesofNAT2,smoking status,ethnic characteristics,and diagnosisofSLE,potentialassociationsbetweengenotypesor phenotypesofNAT2,andseveralclinicalfeaturesofSLE,as wellastheestimationofhaplotypesfromthefrequenciesof genotypescorrespondingtothefoursubstitutions,were per-formedusingSNPStatssoftware(InstitutCatalàd’Oncologia, Barcelona, Spain).22 p-Values <0.05 were considered

signifi-cant.

Results

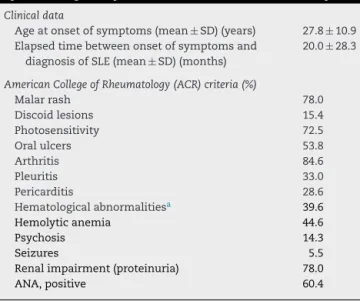

Our study population consistedof188 participants,91 SLE patients (the casegroup) and 97 women without SLE (the controlgroup). Themean age (±standarddeviation)ofSLE patients (40.6±11.1 years; 20–69 years) and of controls (36.9±10.8years;17–66years)atthetimeofinclusioninthe studywassignificantlydifferent(p=0.0214).Althoughthe dis-tributionsbyageinbothgroupsalsohavebeenshowntobe different(p=0.0168),approximately60%ofwomenbelonging tothetwogroupswereagedbetween30and49years.The per-centagesofnon-whitewomenweredifferentbetweenthetwo studygroups,withamarginalp-value(p=0.0539).Themost importantclinicalfeaturesobservedinpatientswithSLEare showninTable1.

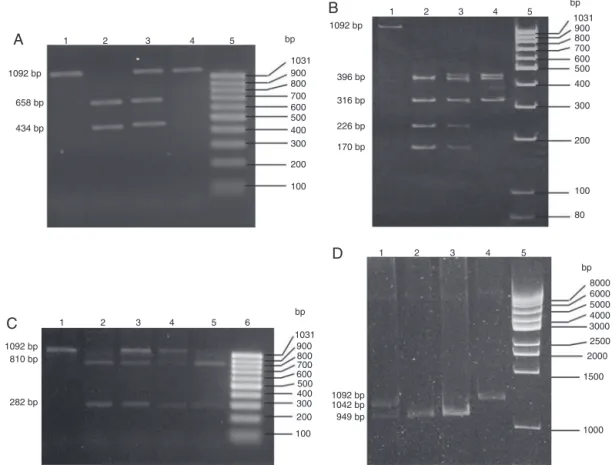

Atotalof188samplesofDNA,correspondingtoourstudy population, were assessed with respect to the four NAT2 substitutions. The digestion profiles representative ofeach analysiscanbeseeninFig.1.

ThecontrolgroupfollowedtheHardy–Weinbergprinciple with respect to the analyzed substitutions (Table 2). The genotype andallele distributionscorrespondingtothe four

Table1–Clinicalcharacteristicsofpatientswith systemiclupuserythematosusincludedinthisstudy.

Clinicaldata

Ageatonsetofsymptoms(mean±SD)(years) 27.8±10.9 Elapsedtimebetweenonsetofsymptomsand

diagnosisofSLE(mean±SD)(months)

20.0±28.3

AmericanCollegeofRheumatology(ACR)criteria(%)

Malarrash 78.0

Discoidlesions 15.4

Photosensitivity 72.5

Oralulcers 53.8

Arthritis 84.6

Pleuritis 33.0

Pericarditis 28.6

Hematologicalabnormalitiesa 39.6

Hemolyticanemia 44.6

Psychosis 14.3

Seizures 5.5

Renalimpairment(proteinuria) 78.0

ANA,positive 60.4

a Reductions of platelets, lymphocytes and leukocytes were

1

A

B

D

C

1092 bp

bp

bp bp

1031

1092 bp

396 bp

316 bp

226 bp

170 bp 900

800 700 600 500 400 300

200

100

bp

1031 900 800 700 600 500 400 300 200

100

8000 6000 5000 4000 3000 2500

2000

1500

1000 1031

900 800 700 600 500 400

300

200

100

80 658 bp

434 bp

1092 bp 1042 bp 949 bp 1092 bp

810 bp

282 bp

2 3 4 5

1 2 3 4 5

1 2 3 4 5

1 2 3 4 5 6

Fig.1–MolecularanalysisoffoursubstitutionsintheNAT2gene.(A)Photographofa2.0%agarosegelstainedwith ethidiumbromideforanalysisofthesubstitution481C>T.Lane1–negativecontrolofthedigestionreaction(intact amplicon);Lane2–representativesampleoftheNAT2genotype481CC(twoalleleswithKpnIrestrictionsite);Lane3– representativesampleoftheNAT2genotype481CT(onlyoneofthealleleswithKpnIrestrictionsite);Lane4–representative sampleoftheNAT2genotype481TT(twoalleleswithoutKpnIrestrictionsite);Lane5–molecularweightpattern

(GeneRulerTM100bpDNALadder,readytouse–Fermentas).(B)Photographofa6.0%polyacrylamidegelstainedwith ethidiumbromideforanalysisofthe590G>Asubstitution.Lane1–negativereactioncontrol(intactamplicon);Lane2– representativesampleoftheNAT2genotype590GG(twoalleleswithanadditionalTaqIrestrictionsite);Lane3–

representativesampleoftheNAT2genotype590GA(onlyoneofthealleleswithanadditionalTaqIrestrictionsite);Lane4– representativesampleoftheNAT2genotype590AA(twoalleleswithoutanadditionalTaqIrestrictionsite);Lane5– molecularweightpattern(GeneRulerTM100bpDNALadder,readytouse–Fermentas).(C)Photographofa1%agarosegel stainedwithethidiumbromideforanalysisofthe857G>Asubstitution.Lane1–negativecontrolofdigestionreaction (intactamplicon);Lanes2and5–representativesamplesoftheNAT2genotype857GG(twoalleleswithanadditionalBamHI restrictionsite);Lanes3and4–representativesamplesoftheNAT2genotype857GA(onlyoneallelewithanadditional

BamHIrestrictionsite);Lane6–molecularweightpattern(GeneRulerTM100bpDNAladder,readytouse–Fermentas).(D) Photographofa5%polyacrylamidegelstainedwithethidiumbromideforanalysisofthe191G>Asubstitution.Lane1– representativesampleoftheNAT2genotype191GA(onlyoneofthealleleswithaMsplrestrictionsite);Lanes2and3– representativesamplesoftheNAT2genotype191GG(twoallelesofanadditionalMspIrestrictionsite);Lane4–negative controlfordigestionreaction(intactamplicon);Lane5–molecularweightpattern(GeneRulerTM1kpDNALadder,readyto use–Fermentas).

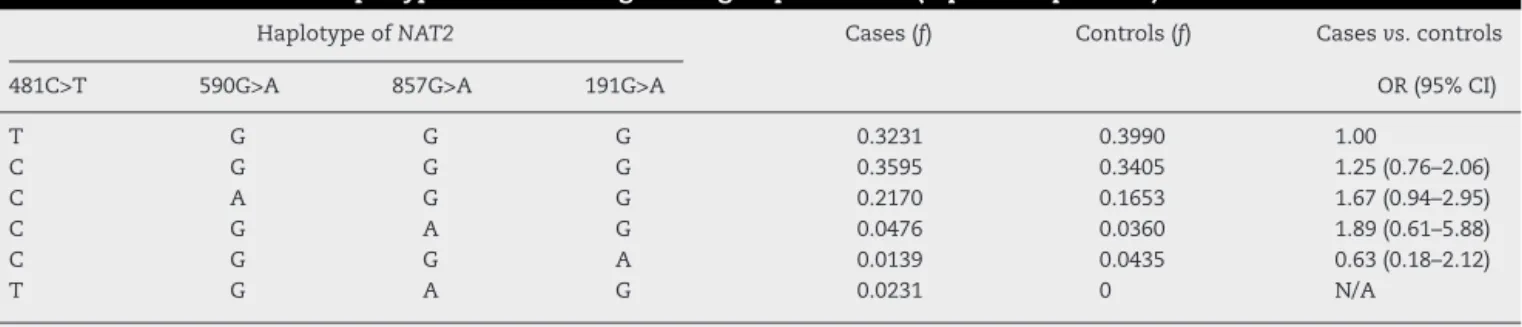

substitutions of the NAT2 gene, as well as the phenotype distributions of NAT2 (Table 2) and haplotype frequencies (Table 3) showed no statistically significant differences betweencasesandcontrols.

Thestudypopulationwasdividedaccordingtoethnic char-acteristicsintwosubgroups, white andnonwhite subjects. Therewasnosignificantdifferenceintheanalysisrelatedto 481C>T,590G>A,and191G>Asubstitutions,ortothe pheno-typeofNAT2.However,withregardtothe857G>Asubstitution, the GA genotype was moreprevalent in patientswith SLE

comparedtocontrols,butonlyamongnon-whiteparticipants (OR=4.01,95%CI=1.18–13.59;p=0.023)(Table4).

Thestudy populationwasfurtherstratifiedaccordingto smokingstatus(smokersorformersmokers,and nonsmok-ers),andnoassociationofthisvariablewasfound,alongwith NAT2genotypesortheacetylatorphenotypeoftheenzyme, withthediagnosisofdisease(datanotshown).

Table2–GenotypeandalleledistributionsforeachofthefoursubstitutionsoftheNAT2geneandacetylatorphenotype incase-(patientswithSLE)andcontrolgroups.

Substitution/acetylatorphenotype Genotype/allele/phenotype Cases(n=91) Controlsa(n=97) Casesvs.controls

n(%)or(f) n(%)or(f) OR(95%CI)

NAT2481C>T CC 40(44) 34(35) 1.00

CT 39(43) 46(48) 0.72(0.39–1.35)

TT 12(13) 16(17) 0.64(0.27–1.53)

CT+TT 51(56) 62(65) 0.70(0.39–1.26)

C 119(0.65) 114(0.59) 1.00

T 63(0.35) 78(0.41) 0.77(0.51–1.18)

NAT2590G>A GG 53(59) 66(68) 1.00

GA 32(36) 27(28) 1.48(0.79–2.76)

AA 5(6) 4(4) 1.56(0.40–6.09)

GA+AA 37(41) 31(32) 1.49(0.82–2.71)

G 138(0.77) 159(0.82) 1.00

A 42(0.23) 35(0.18) 1.38(0.84–2.29)

NAT2857G>A GG 70(84) 88(93) 1.00

GA 13(16) 7(7) 2.34(0.88–6.17)

AA 0 0 N/A

GA+AA 13(16) 7(7) 2.34(0.88–6.17)

G 153(0.92) 183(0.96) 1.00

A 13(0.08) 7(0.04) 2.22(0.86–5.71)

NAT2191G>A GG 87(96) 81(91) 1.00

GA 4(4) 7(8) 0.53(0.15–1.89)

AA 0 1(1) N/A

GA+AA 4(4) 8(9) 0.47(0.14–1.61)

G 178(0.98) 169(0.95) 1.00

A 4(0.02) 9(0.05) 0.42(0.13–1.40)

Phenotype Fast 45(53) 48(53) 1.00

Slow 40(47) 43(47) 1.00(0.56–1.82)

n,numberofpatients;f,allelefrequency;N/A,notapplicable.

ThetotalsampleswithdatarelatingtothefourNAT2polymorphismsandtotheacetylatorphenotypemaydifferfromthetotalofanalyzed samples,duetotheexistenceofunsatisfactoryresults.

a Hardy–Weinbergequilibriumtest:NAT2481C>T(p=1.00);NAT2590G>A(p=0.50);NAT2857G>A(p=1.00);NAT2191G>A(p=0.19)(SNPStats).

Table3–DistributionsofhaplotypesoftheNAT2geneingroupsofcases(lupusSLEpatients)andcontrols.

HaplotypeofNAT2 Cases(f) Controls(f) Casesvs.controls

481C>T 590G>A 857G>A 191G>A OR(95%CI)

T G G G 0.3231 0.3990 1.00

C G G G 0.3595 0.3405 1.25(0.76–2.06)

C A G G 0.2170 0.1653 1.67(0.94–2.95)

C G A G 0.0476 0.0360 1.89(0.61–5.88)

C G G A 0.0139 0.0435 0.63(0.18–2.12)

T G A G 0.0231 0 N/A

f,haplotypefrequency;N/A,notapplicable.

Haplotypeswithfrequency<0.01werenotconsidered.

lesions, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, arthritis, pleuritis, pericarditis, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, autoimmune thrombocytopenia,psychosis,seizures,proteinuria,and pos-itive ANA. The481T allele was more prevalent inpatients withhematological disorders (autoimmunehemolytic ane-mia or autoimmune thrombocytopenia), when compared to those who did not show this feature (OR=1.97; 95% CI=1.02–3.82;p=0.0477).Therewasnoassociation between the other NAT2 substitutions, or NAT2 phenotype, and clinical characteristics of the patients (data not shown).

Table4–AnalysisofinteractionbetweengenotypesrelatedtosubstitutionsintheNAT2geneorNAT2phenotype andethnicorigin,incase-(SLEpatients)andcontrolgroups.

Substitution/acetylator phenotype

Skincolor/ethnicity Genotype/phenotype Casesn(%) Controlsn(%) Casesvs.controls

OR(95%CI)

NAT2481C>T White C/C 12(36) 6(27) 1.00

C/T 19(58) 11(50) 0.86(0.25–2.95)

T/T 2(6) 5(23) 0.20(0.03–1.35)

Nonwhite C/C 28(48) 28(38) 1.00

C/T 20(35) 35(47) 0.57(0.27–1.22)

T/T 10(17) 11(15) 0.91(0.33–2.48)

NAT2590G>A White G/G 18(55) 17(77) 1.00

G/A 14(42) 4(18) 3.31(0.91–12.06)

A/A 1(3) 1(5) 0.94(0.05–16.34)

Nonwhite G/G 35(61) 49(65) 1.00

G/A 18(32) 23(31) 1.10(0.52–2.33)

A/A 4(7) 3(4) 1.87(0.39–8.87)

NAT2857G>A White G/G 27(90) 19(86) 1.00

G/A 3(10) 3(14) 0.70(0.13–3.87)

A/A 0 0 N/A

Nonwhite G/G 43(81) 69(95) 1.00

G/A 10(19) 4(5) 4.01(1.18–13.59)a

A/A 0 0 N/A

NAT2191G>A White G/G 32(97) 20(95) 1.00

G/A 1(3) 1(5) 0.62(0.04–10.57)

A/A 0 0 NA

Nonwhite G/G 55(95) 61(90) 1.00

G/A 3(5) 6(9) 0.55(0.13–2.32)

A/A 0 1(1) N/A

Phenotype White Fast 17(55) 11(52) 1.00

Slow 14(45) 11(48) 1.21(0.41–3.63)

Nonwhite Fast 28(52) 37(54) 1.00

Slow 26(48) 32(46) 0.93(0.46–1.90)

White,individualandtheparentswhite-coloredbyself-declaration;Nonwhite,anindividualand/oratleastoneoftheparentsbrownor black-coloredbyself-declaration;n,numberofpatients;N/A,notapplicable.

Significantresultisinboldletters. a Fisher’stest:p=0.0230.

Discussion

and

conclusion

N-acetyltransferase2(NAT2)variantshavebeenwidely stud-iedinordertoassessitsdistributionamongdifferentethnic groups,whichcanalsoberelatedtotheexposuretodifferent environmentalfactors;anditsassociationwithawiderangeof diseases,includingthoseofautoimmuneorigin.Inthispaper, weevaluatethepossibleexistenceofanassociationbetween the481C>T,590G>A,857G>Aand191G>Apolymorphismsin theNAT2geneandsystemiclupuserythematosus.

The studies of an association between NAT2 and SLE describedintheliterature,ingeneral,considertheacetylator phenotypeand notNAT2 polymorphisms inisolation. Tak-inginto accountthatthesubstitutionshere discussedmay interfere withthe levels of gene expressionthrough post-transcriptionalregulationmechanisms(481C>T),changethe stabilityoftheenzyme(590G>Aand191G>A),ormodifythe selectivityand catalytic activity (857G>A),16 an association

analysiswasalsoperformedwitheach ofthesubstitutions inisolation.However,ourresultsshowedanabsenceofan associationbetweenthefourNAT2substitutions,ortheNAT2 acetylatorphenotypeandthedisease(Table1).Theestimateof

haplotypesalsoshowednoassociationwithSLE(Table2),even thoughaidinginthephenotypicclassificationofthesamples, asmentionedabove.Recentstudieshavealsousedthisfeature toinferNAT2phenotypesbasedongenotypingdata.23,24

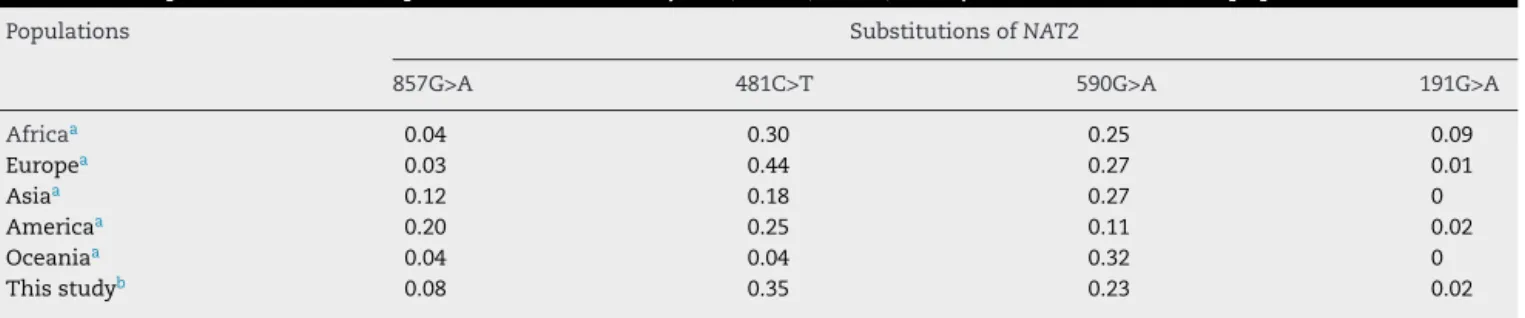

ThepolymorphismsanalyzedinNAT2genehavedistinct allelic distributions among different populations. Sabbagh etal.conductedaworldwidesurveyofthefrequencyof sev-eralNAT2polymorphismsandalsooftheirphenotype.25The

Table5–FrequenciesoflessfrequentallelesofNAT2(481T,590A,857A,191A)observedinvariouspopulations.

Populations SubstitutionsofNAT2

857G>A 481C>T 590G>A 191G>A

Africaa 0.04 0.30 0.25 0.09

Europea 0.03 0.44 0.27 0.01

Asiaa 0.12 0.18 0.27 0

Americaa 0.20 0.25 0.11 0.02

Oceaniaa 0.04 0.04 0.32 0

Thisstudyb 0.08 0.35 0.23 0.02

a Sabbaghetal.,2011.Controldataspecificforeachofdiseasemodelsincludedinthecasegroup.

b Patientsfromcontrolgroup.

thissamepopulation,itwasobservedthatwhiteindividuals, throughself-declaration,had86%ofEuropeanancestryand 13%ofAfricanorAmerindianancestry.Ontheotherhand,the patientsself-declaredasnonwhites,ofbrownorblackcolor, had24%and49%ofAfricanancestryand67%and43%of Euro-peanancestry, respectively.27 These datarevealthe greater

degreeofmiscegenationpresentinthoseself-declaredasof brownandblackcolor.Thehighdegreeofethnic heterogene-ityofourstudypopulationcouldexplaintheclose,but not identical,valuestothoseobservedinotherpopulations.

Inthe literature,thereare reportson theassociation of NAT2 polymorphisms with various diseases, such as dif-ferent types of cancer,28 periodontitis,29 and autoimmune

diseases,3,30,31 whoadoptthesmokinghabitasan

environ-mentalriskfactor.29,32Anassociationbetweentheacetylator

phenotypeofNAT2,smokingandSLEwasalreadyobserved.2

However,in the Brazilianpopulation, there isno study on the association of polymorphisms in NAT2 gene and/or of acetylatorphenotypewiththisdisease,especiallyin smok-ers.Althoughseveralauthorsconsiderthattheexposureto tobaccocomponentsmayconstitutea“trigger”forthe devel-opmentofSLE,2–7 wehadaccesstoinformationonsmoking

habitduringthecollectionofbiologicalsamples,andnotat thetimeofdiseaseonset.Therefore,ourstudypopulationwas subdividedintotwogroups,accordingtothesmokinghabit,as smokersorex-smokersandnonsmokers.Ourresultsshowed noassociationbetweenthesevariablesandthedisease(data notshown).Itisworthnotingthat,atthetimeapatientis diag-nosed,shereceivesguidancetoabstainfromsmoking,which mayhavecreatedabiasintheanalysis.Infact,fewersmokers andformersmokerswereobservedinthegroupofcases,a factthatwasnotrelatedtoaprotectionofsmokinghabitsin relationtodiseasedevelopment.Itshouldbenotedthat addi-tionalsmokingdata,includingexposuretimeandthenumber ofpacks ofcigarettes/day,atthefirst indicationofdisease manifestation,couldcontribute totheanalysiscarried out, takingintoaccountthepossibilityofthedifferential metabo-lizationofvariouscomponentsofcigarettesmoke,depending ontheacetylatorphenotype.However,thetimeofonsetofthe diseaseisacomplexaspecttobeestablished.Itisfrequentthe occurrenceofaperiodofseveralmonthsbetweentheonset ofsymptomsanddiseasediagnosis.

BesidesthedifferenceinthefrequencyofNAT2 polymor-phismsindifferentpopulations,theincidenceofSLEishigher inethnicallymixedpatients.5Thus,inthisstudy,weevaluated

whethertherewasanassociationbetweenthedistributionof

NAT2polymorphismsandSLEpatientswiththisethnic fea-ture.Withthisinmind,self-declarationsandinformationon theparent(fatherandmother)skincolorwereusedtodefine theethnicoriginofthepatients,asreportedintheliterature,21

butweacknowledgethatothermethodscouldbemore appro-priatetothis end.Significantresultswereobservedonlyin relationtotheNAT2857G>Apolymorphism,withthegenotype 857GA representingapotentialriskforthe diseasein non-whitewomen(Table4).TheNAT2857G>Asubstitutionhasas aconsequence,intheprotein,thechangeoftheaminoacid glycinebyglutamate(G286E).Thischangemodifiestheaccess totheactivesiteoftheenzyme,whichresultsinreduced selec-tivity and catalyticcapacity.16 Therefore, the NAT2857G>A

polymorphismisrelatedtothereductioninthemetabolismof aromaticandheterocyclicamines.16Thesubstitution857G>A

ispresentin11NAT2alleles,twoofwhichhaveaslow acety-lator phenotype,and theotheroneshavenotyethadtheir phenotypesdefined.33 Theslowacetylatorphenotypecould

conferanincreasedriskforSLE,sincethebodywouldremain exposed fora longer time, forexample, tocomponents of cigarette smoke. It is worth noting that the variables eth-nicoriginandNAT2857G>Agenotypeswerenotindividually associatedwithSLE.Nevertheless,theliteraturepointstoa higherincidenceofSLEinethnicallymixedindividuals,1and,

inapopulationofthecityofIlheus(Bahia/Brazil),the857GA genotype wasmoreprevalent inAfrican-Brazilian subjects, comparedtowhitesandAmerindians.34Theancestryofthe

RiodeJaneiropopulationissimilartothoseestimatedvalues forthepopulationofBrazilianNortheast.26,35However,ithas

beensuggestedthatlargeurbancenters,likeRiodeJaneiro, presentmorediversepatternsofethnicmixture.26

Theorgansaffectedandtheintensityofclinical manifes-tationsinSLEpatientscharacterizetheseverityofthedisease and somehowguidethe therapeuticschemeselection.The only significant resultin the analysis ofthe interaction of theNAT2polymorphismsoroftheacetylatorphenotypewith clinical features of SLE was the greater prevalence of the allele481Tinpatientswithhematologicdiseases,specifically autoimmunehemolyticanemiaorautoimmune thrombocy-topenia(datanotshown).Thereductionofthesecelltypes may beassociatedwiththe immunosuppressioncausedby theseverityofthediseaseorbytheuseof immunomodula-torydrugs.36 Sofar,thereisnoevidenceastothewaythe

However,when consideringonlythe smoking habit, we found a correlation with the presence of discoid lupus (OR=8.62, 95% CI 2.40–30.96; p=0.0011) and proteinuria (OR=0.17, 95% CI 0.05–0.59; p=0.0056). In several studies, dermatologic alterationspresent inpatients withSLEwere associatedwithsmokingand,aspreviouslymentioned,the treatmentoftheselesionsinsmokersseemstorequirehigher dosesofantimalarials,comparedtononsmokers.37–39Inour

study,thesmall numberofpatientswithSLEand smokers (n=7)didnotallowustoinferifsmokinghabitreallyhadan impactonthepharmacologicalapproach.Thesmokinghabit isalsoassociatedwithrenaldisorders,suchas proteinuria andnephropathy40;however,inthisstudy,from71patients

withproteinuria,only7are currentsmokers,13areformer smokers,andmostwerelifetimenonsmokers.

IntheBrazilianpopulation,therearefewstudieson geno-typeandalleledistributionsofNAT2,andtherearenoreports abouttheassociation ofNAT2polymorphisms andSLE.We believethatourworkhasaleadingroleinthisarea,andwe understandit asaformulatorofthehypothesisofa poten-tialroleofNAT2polymorphismsasafactorassociatedwith thediseaseinourcountry,andofapossibleassociationwith specificclinicalphenotypes.However,furtherstudies involv-inglargerpopulationsareneeded,toconfirmtheassociation betweentheNAT2857G>Apolymorphismandsystemiclupus erythematosusinself-declarednon-whiteBrazilianwomen, ideally including ethnic profiling with the use ofancestry markers.

Funding

ThisstudyreceivedfinancialsupportfromCNPq–National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (476116/2009-0), FAPERJ – Research Support Foundation of the State of Rio de Janeiro (E-26/170.922/2004 and E-26/111.334/2011),UERJ–StateUniversityofRiodeJaneiro,and CERPE–CentreofStudiesinRheumatologyPedroErnesto,Rio deJaneiro.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1. SatoEI.Lúpuseritematososistêmico;2008.Availableat:

http://www.fmrp.usp.br/cg/novo/images/pdf/conteudo disciplinas/lupuseritematoso[accessed11.09.13]. 2. KiyoharaC,WashioM,HonuchiT,TadaY,AsamiT,IdeS,

etal.Cigarettesmoking,N-acetyltransferase2

polymorphismsandsystemiclupuserythematosusina Japanesepopulation.Lupus.2009;18:630–8.

3. KiyoharaC,WashioM,HoriuchiT,AsamiT,IdeS,AtsumiT, etal.Cigarettesmoking,alcoholconsumption,andriskof systemiclupuserythematosus:acase–controlstudyina Japanesepopulation.JRheumatol.2012;39:1363–70.

4. WallaceDJ.Principlesoftherapyandlocalmeasures.In: WallaceDJ,HahnBH,editors.Dubois’lupuserythematosus.

7thed.Philadelphia:LippincottWilliams&Wilkins;2007.p. 1132–44.

5.CostenbaderKH,KimDJ,PeerzadaJ,LockmanSL,

Nobles-KnightD,PetriM,etal.Cigarettesmokingandtherisk ofsystemiclupuserythematosus:ameta-analysis.Arthritis Rheum.2004;50:849–57.

6.FreemerMM,KingTEJr,CriswellLA.Associationofsmoking withdsDNAautoantibodyproductioninsystemiclupus erythematosus.AnnRheumDis.2006;65:581–4.

7.WashioM,HoriuchiT,KiyoharaC,KodamaH,TadaY,Asami T,etal.Smoking,drinking,sleepinghabits,andotherlifestyle factorsandtheriskofsystemiclupuserythematosusin Japanesefemales:findingsfromtheKYSSstudy.Mod Rheumatol.2006;16:143–50.

8.EzraN,JorizzoJ.Hydroxychloroquineandsmokinginpatients withcutaneouslupuserythematosus.ClinExpDermatol. 2012;37:327–34.

9.PerryHMJr,TanEM,CarmodyS,SakamotoA.Relationshipof acetyltransferaseactivitytoantinuclearantibodiesandtoxic symptomsinhypertensivepatientstreatedwithhydralazine. JLabClinMed.1970;76:114–25.

10.WoosleyRL,DrayerDE,ReidenbergMM,NiesAS,CarrK, OatesJA.Effectofacetylatorphenotypeontherateatwhich procainamideinducesantinuclearantibodiesandthelupus syndrome.NEnglJMed.1978;298:1157–9.

11.WindmillKF,GaedigkA,HallPM,SamaratungaH,GrantDM, McManusME.LocalizationofN-acetyltransferasesNAT1and NAT2inhumantissues.ToxicolSci.2000;54:19–29.

12.MeiselP,GiebelJ,PetersM,FoersterK,CascorbiI,WulffK, etal.ExpressionofN-acetyltransferasesinperiodontal granulationtissue.JDentRes.2002;81:349–53.

13.MitchellKR,WarshawskyD.Xenobioticinducibleregionsof thehumanarylamineN-acetyltransferase1and2genes. ToxicolLett.2003;139:11–23.

14.WuH,DombrovskyL,TempelW,MartinF,LoppnauP, GoodfellowGH,etal.Structuralbasisofsubstrate-binding specificityofhumanarylamineN-acetyltransferases.JBiol Chem.2007;282:30189–97.

15.García-MartinE.Interethnicandintraethnicvariabilityof

NAT2singlenucleotidepolymorphisms.CurrDrugMetab. 2008;9:487–97.

16.RajasekaranM,AbiramiS,ChenC.Effectsofsinglenucleotide polymorphismsonhumanN-acetyltransferase2structure anddynamicsbymoleculardynamicssimulation.PLoSONE. 2011;6:e25801.

17.HuangC,ChernH,ShenC,HsuS,ChangK.Association betweenN-acetyltransferase2(NAT2)geneticpolymorphism anddevelopmentofbreastcancerinpost-menopausal ChinesewomenTaiwan,anareaofgreatincreaseinbreast cancerincidence.IntJCancer.1999;82:175–9.

18.HeinDW,DollM,FretlandAJ,LeffMA,WebbSJ,XiaoGH,etal. MoleculargeneticsandepidemiologyoftheNAT1andNAT2

acetylationpolymorphisms.CancerEpidemiolBiomarkers Prev.2000;9:29–42.

19.KlumbEM,AraújoMLJr,JesusGR,SantosDB,OliveiraAV, AlbuquerqueEM,etal.Ishigherprevalenceofcervical intraepithelialneoplasiainwomenwithlupusdueto immunosuppression?JClinRheumatol.2010;16:153–7.

20.KlumbEM,PintoAC,JesusGR,AraujoMJr,JasconeL,Gayer CR,etal.ArewomenwithlupusathigherriskofHPV infection.Lupus.2010;19:1485–91.

21.Vargas-TorresSL,PortariEA,KlumbEM,GuillobelHCR, CamargoMJ,RussomanoFB,etal.AssociationofCDKN2A polymorphismswiththeseverityofcervicalneoplasiaina Brazilianpopulation.Biomarkers.2014;19:121–7.

22.SoléX,GuinóE,VallsJ,IniestaR.,MorenoV.SNPStats:your webtoolforSNPanalysis.Availableat:

23.SinglaN,GuptaD,BirbianN,SinghJ.AssociationofNAT2,

GSTandCYP2E1polymorphismsandanti-tuberculosis drug-inducedhepatotoxicity.Tuberculosis.2014;94:293–8.

24.SelinskiS,BlaszkewiczM,IckstadtK,HengstlerJG,GolkaK. RefinementofthepredictionofN-acetyltransferase2(NAT2) phenotypeswithrespecttoenzymeactivityandurinary bladdercancerrisk.ArchToxicol.2013;87:2129–39.

25.SabbaghA,DarluP,Crouau-RoyB,PoloniES.Arylamine N-acetyltransferase2(NAT2)geneticdiversityandtraditional subsistence:aworldwidepopulationsurvey.PLoSONE. 2011;6:e18507.

26.MantaFSN,PereiraR,ViannaR,deAraújoARB,GitaíDLG, SilvaDA,etal.RevisitingthegeneticancestryofBrazilians usingautosomalAIM-Indels.PLoSONE.2013;8:e75145.

27.PenaSDJ,DiPietroG,Fuchshuber-MoraesM,GenroJP,Hutz MH,KehdyFSG,etal.Thegenomicancestryofindividuals fromdifferentgeographicalregionsofBrazilismoreuniform thanexpected.PLoSONE.2011;6:e17063.

28.HeinDW.N-acetyltransferase2geneticpolymorphism: effectsofcarcinogenandhaplotypeonurinarybladder cancerrisk.Oncogene.2006;25:1649–58.

29.MeiselP,TimmR,SawafH,FanghãnelJ,SiegmundW,Kocher T.PolymorphismoftheN-acetyltransferase(NAT2),smoking andthepotentialriskofperiodontaldisease.ArchToxicol. 2000;74:343–8.

30.KlareskogL,PadyukovL,AlfredssonL.Smokingasatrigger forinflammatoryrheumaticdiseases.CurrOpinRheumatol. 2007;19:49–54.

31.MikulsTR,LevanT,GouldKA,YuF,ThieleGM,BynoteKK, etal.ImpactofinteractionsofcigarettesmokingwithNAT2

polymorphismsonrheumatoidarthritisriskinAfrican Americans.ArthritisRheum.2012;64:655–64.

32.RouissiK,OuerhaniS,MarrakchiR,BenSlamaMR,SfaxiM, AyedM,etal.Combinedeffectofsmokingandinherited

polymorphismsinarylamineN-acetyltransferase2, glutathioneS-transferasesM1andT1onbladdercancerina Tunisianpopulation.CancerGenetCytogenet.2009;190:101–7.

33.BoukouvalaS,HeinDW,GrantDM,SimE,MinchinRF, AgúndezJAG,etal.ThearylamineN-acetyltransferasegene nomenclaturecommittee.DemocritusUniversityofThrace. Availableat:

http://nat.mbg.duth.gr/Human%20NAT2%20alleles2013.htm

[accessed26.11.14].

34.TalbotJ,MagnoLAV,SantanaCVN,SousaSMB,MeloPR, CorreaRX,etal.InterethnicdiversityofNAT2polymorphisms inBrazilianadmixedpopulations.BMCGenet.2010;11:87.

35.MagalhãesdaSilvaT,SandhyaRaniMR,deOliveiraCostaGN, FigueiredoMA,MeloPS,NascimentoJF,etal.Thecorrelation betweenancestryandcolorintwocitiesofNortheastBrazil withcontrastingethniccompositions.EurJHumGenet. 2015;23:984–9.

36.BashalF.Hematologicaldisordersinpatientswithsystemic lupuserythematosus.OpenRheumatolJ.2013;7:87–95.

37.DutzJ,WerthVP.Cigarettesmokingandresponseto antimalarialsincutaneouslupuserythematosuspatients: evolutionofadogma.JInvestDermatol.2011;131:1968–70.

38.PietteEW,FoeringKP,ChangAY,OkawaJ,TenHaveTR,Feng R,etal.Impactofsmokingincutaneouslupus

erythematosus.ArchDermatol.2011;148:317–22.

39.Bourré-TessierJ,PeschkenCA,BernatskyS,JosephL,Clarke AE,FortinPR,etal.Associationofsmokingwithcutaneous manifestationsinsystemiclupuserythematosus.Arthritis CareRes(Hoboken).2013;65:1275–80.