CONSIGLIO NAZIONALE DELLE RICERCHE

ISTITUTO DI STUDI SUL MEDITERRANEO ANTICO

SUPPLEMENTO ALLA

TRANSFORMATIONS AND CRISIS

IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

“IDENTITY” AND INTERCULTURALITY

IN THE LEVANT AND PHOENICIAN WEST

DURING THE 8TH-5TH CENTURIES BCE

EDITED BY

GIUSEPPE GARBATI AND TATIANA PEDRAZZI

CNR – ISTITUTO DI STUDI SUL MEDITERRANEO ANTICO

CNR EDIZIONI

SUPPLEMENTI ALLA RIVISTA DI STUDI FENICI Direttore responsabile / Editor in Chief

Lorenza Ilia Manfredi Comitato scientifico / Advisory Board

Ana Margarida Arruda, Babette Bechtold, Corinne Bonnet, José Luis López Castro, Francisco Nuñez Calvo, Roald Docter,

Ayelet Gilboa, Imed Ben Jerbania, Antonella Mezzolani, Alessandro Naso, Sergio Ribichini, Hélène Sader, Peter van Dommelen, Nicholas Vella, José Ángel Zamora López.

Redazione scientifica / Editorial Board

Andrea Ercolani, Giuseppe Garbati, Silvia Festuccia, Tatiana Pedrazzi Assistente per la grafica / Graphic Assistant

Laura Attisani

Segretaria di Redazione / Editorial Assistant Giorgia Rubera

Sede della Redazione / Editorial Office CNR – Istituto di Studi sul Mediterraneo Antico

Area della Ricerca di Roma 1 Via Salaria km 29,300, Casella postale 10

00015 Monterotondo Stazione (Roma) e-mail: lorenza.manfredi@isma.cnr.it Sito internet: http://rstfen.isma.cnr.it

© CNR Edizioni Piazzale Aldo Moro, 7 – Roma

www.edizioni.cnr.it

Progetto grafico e impaginazione / Graphic Project and Layout Marcello Bellisario

Autorizzazione del Tribunale di Roma

n. 218 in data 31 maggio 2005 e n. 14468 in data 23 marzo 1972 ISBN 978 88 8080 216 7

Finito di stampare nel mese di novembre 2016 da PRINT COMPANY SRL Via Edison 20, 00015 Monterotondo (Roma)

Table of Contents

Foreword, Lorenza Ilia Manfredi Acknowledgments

The Levant and Beyond

Tatiana Pedrazzi, Transformations and Crisis in the Mediterranean (8th-5th century BCE). The Levant and Beyond: An Introduction

Marina Pucci, Material Identity in Northern Levant during the 8th Century BCE: The Example from Chatal Höyük

Vanessa Boschloos, Phoenician Identity through Retro-Glyptic. Egyptian Pseudo-Inscriptions and the Neo-“Hyksos” Style on Iron Age II-III Phoenician and Hebrew Seals

Fabio Porzia, Acheter la terre promise: les contrats d’achat de la terre et leur rôle dans la définition ethnique de l’ancien Israël

Anja Ulbrich, Multiple Identities in Cyprus from the 8th to the 5th century BCE: The Epigraphic and Iconographic Evidence from Cypriot Sanctuaries

Tatiana Pedrazzi, The Levant as Viewed from the East: How the Achaemenids Represented and Constructed the Identity of the Phoenicians and Other Levantine Peoples

Bärbel Morstadt, Identity and Crisis: Identity in Crisis? A Look into Burial Customs

Towards the Phoenician West

Giuseppe Garbati, Transformations and Crisis in the Mediterranean (8th-5th century BCE). Towards the Phoenician West: An Introduction

Valentina Melchiorri, Identità, identificazione sociale e fatti culturali: osservazioni sul mondo della diaspora fenicia e alcune sue trasformazioni (VIII-VI sec. a.C.)

Iván Fumadó Ortega, Qui êtes-vous? Où habitez-vous? Données sur l’architecture et la morphologie urbaine de la Carthage archaïque: apports et limites pour l’étude des phénomènes identitaires

Rossana De Simone, Identità e scrittura: phoinikazein in Sicilia e nell’Occidente fenicio? Per una metodologia della ricerca

pag. 9 “ 11 “ 15 “ 25 “ 43 “ 61 “ 81 “ 99 “ 123 “ 139 “ 149 “ 173 “ 195

Giuseppe Garbati, “Hidden Identities”: Observations on the “Grinning” Phoenician Masks of Sardinia

Carla Perra, Tradizione e identità nelle comunità miste. Il Sulcis (Sardegna sud-occidentale) fra la fine del VII e la prima metà del VI sec. a.C.

Vincenzo Bellelli, L’interazione culturale etrusco-fenicia nell’area medio-tirrenica: il caso agylleo

Eduardo Ferrer Albelda, Ethnicity and Cultural Identity among Phoenician Communities in Iberia

Elisa Sousa, The Tagus Estuary (Portugal) during the 8th-5th Century BCE: Stage of Transformation and Construction of Identity

pag. 209

“ 229 “ 243 “ 263

THE TAGUS ESTUARY (PORTUGAL) DURING THE 8TH-5TH CENTURY

BCE: STAGE OF TRANSFORMATION AND CONSTRUCTION OF

IDENTITY

Elisa Sousa*

Abstract: The earliest Iron Age phase in the Tagus estuary (late 8th-6th century BCE, in traditional chronology) engaged a highly

diversified range of active agents who took part in the area’s orientalization process: local Late Bronze Age communities, western Phoenician settlers and possibly also native elements from southern Iberia. Each of these groups sustains a heterogeneous formation that derives from differentiated social, economic and cultural status played by their constituents, and that is, unfortunately, very difficult to distinguish in terms of the available archaeological evidence. However, we believe that it is possible, at least to some degree, to trace their different cultural markers, and try to understand the role played by each of these agents in the formation of a unique identity sphere that will characterize the central western Atlantic coast of Iberia during the 1st millennium BCE.

Keywords: Phoenician; Native Communities; Orientalization; Cultural Markers; Iron Age.

1. Introduction

The attempt to identify identity signatures through the archaeological evidence is always a challenging task. The inherent limitations of the available data and our frequent inability to accurately retrieve its original cultural meaning constrains us to develop a series of interpretive frameworks that we can only hope to bring us closer to a past reality.

There are, without a doubt, scenarios where we can observe radical historical changes that certainly entailed the construction of new identifying elements that prevailed during a given period of time. The arrival of Phoenician groups to the Tagus estuary, as well as to other areas in the Iberian Peninsula, is undoubtedly one of those key moments.

In order to analyze and interpret this phenomenon, one has to take into account an intricate range of agents who actively interacted in this process.

First of all, the indigenous population that inhabited the Tagus estuary prior to the arrival of Phoenician groups, and whose everyday life was dramatically transformed by the subsequent orientalization process. Secondly, the Phoenicians settlers that arrived at the Tagus estuary during the late 8th century BCE. In this case, we should consider not only the intrinsic heterogenic constitution of these “Phoenicians groups”, but also the fact that we are probably dealing with later generations, or, more specifically, descendants of the first colonial waves that settled in the south coast of the Iberian Peninsula. In this point, we must be open to the possibility that the interaction with other Iberian native groups might have already resulted in specific and significant changes in the social-cultural fabric of these “western Phoenicians”. Finally, we must also consider other foreign indigenous communities. As it has been documented in several Phoenician colonial

* Uniarq – Centro de Arqueologia da Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa; e.sousa@

environments located in the Iberian coast (for example in Cadiz,1 Cerro del Villar2 and La Fonteta3), native groups were an integral part of these settlements. Therefore, we must also consider the possibility that these agents could have played an active role in ulterior colonization processes. Such an interpretation could, in fact, explain some remarkable similarities that have been established between the Portuguese Atlantic coast and south Iberia that have, until recently, been interpreted as evidence of a “Tartessic colonization”.4

The interaction and active role-playing of all these distinct agents in the Tagus estuary during the 1st half of the 1st millennium BCE resulted in a unique merge of social and cultural values, which were translated in the development of a new cultural identity. This horizon may even share some common characteristics with other orientalizing spheres, but most of all, it must be comprehended as a unique and individuating juncture and as the result of the combination of specific factors. The formative phase of this process occurs mainly between the late 8th and the 6th century, reaching its higher peak during the 5th century BCE, as a result of yet another historical shift (the so-called “6th century crisis”) that will implicate profound changes in the commercial, cultural and economic background of the western Atlantic Portuguese coast.

The aim of this article is, therefore, to attempt to characterize and differentiate these identity spheres, resorting, inevitably, to the available archaeological record (different economic strategies in terms of the territory’s exploitation and its resources; tendencies and changes in settlement patterns; distinctive characteristics of the material culture such as the preference for certain morphological types and decorative features), while trying to pinpoint different origins to the cultural markers that comprise a constant signature of the Tagus estuary inhabitants between the 8th and the 5th century BCE.

2. The Phoenician Colonization of the Tagus Estuary

With the arrival and settlement of the first Phoenician groups in the Tagus estuary we observe a series of changes that will sweep the entire area and that are clearly visible across the settlement patterns, economic strategies and material culture.

The most obvious transformation is reflected through the apparent collapse of the previous regional infrastructures.

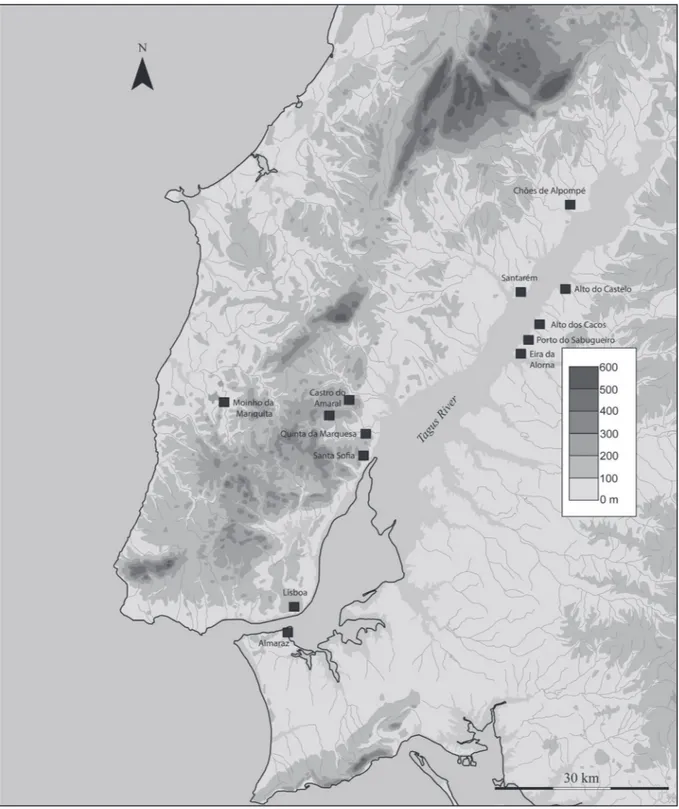

In the Tagus lower area, the Late Bronze Age (LBA) occupation was dominated by apparently small low altitude settlements, with no defensibility whatsoever and focused in agriculture and animal husbandry.5 None of these sites show evidences of contact with the Phoenician groups, which may indicate that they were abandoned during this moment or immediately before, with the exception of Lisbon’s downtown area,6 a situation that we will analyze with more detail further on (Fig. 1). A similar scenario takes place in the interior, where the LBA occupation favored high altitude sites, with an almost absolute visual domain across the surrounding territory and whose natural inaccessibility may have been strengthened with the

1 Zamora López et alii 2010; López Rosendo et alii in press; oral presentation that took place in the 8th Internacional Congress

of Phoenician and Punic Studies (2013), intitled Materiales cerâmicos del trânsito entre los siglos VII y VI a. C. hallados en las intervenciones arqueológicas realizadas en el Teatro Cómico (Gadir/Cádiz).

2 Aubet et alii 1999; Delgado – Ferrer 2007.

3 Rouillard – Gailledrat – Sala Sellés 2007; Azuar et alii 1998; González Prats 1998. 4 Torres Ortiz 2005; Almagro Gorbea – Torres Ortiz 2009; Torres Ortiz 2013. 5 Cardoso 2004, pp. 177-178.

construction of defensive structures.7 This LBA settlement pattern seems to have been focused specifically on territorial dominion, possibly in order to control commercial routes that circulated across the inlands during the LBA8 (Fig. 1).So far, none of these high altitude sites revealed evidence of a continuity during the 8th, 7th and 6th century BCE, even if some occupation in the area seems to have survived through this phase, as it is stated not only through the recent identification of an Iron Age habitat site (Moinho das Mariquitas9), but also by the extraordinary findings of bronze artifacts (oinochoe and two brazier handles) associated with funerary contexts.10 A clear continuity between the LBA and early Iron Age is verifiable only in the Tagus basin (Figs. 1-2), where important settlements such as Alcáçova de Santarém,11 Alto do Castelo12 and probably Castro do Amaral13 seem to have overpassed this critical transition towards the Iron Age, perhaps due to their proximity to the river. In fact, the geography of the early Iron Age settlement pattern (8th-6th century BCE) focuses the Tagus riverbanks,14 which is probably linked to one of the key factors that have led to the Phoenician central Atlantic colonization: the interest in metallic resources. The Tagus not only provides a considerable potential in terms of gold exploration, celebrated even during Roman times,15 but is also a privileged route for access to inner territories, rich in tin.16 This primary economic and commercial interest has probably shaped the settlement pattern of the central Atlantic area during the Iron Age and radically transformed the preexisting infrastructures (Fig. 2).

Agriculture, animal husbandry and seafood recollection, which were the main resources during the LBA, where naturally still important in terms of self-sufficiency, but no longer dictated the molds in which the territory was occupied. Sites that seem specifically dedicated to these activities no longer occupy the fertile “Lisbon’s basaltic complex”, as they did during the LBA,17 but the Tagus basin. An interesting example of the re-adaptation of native communities to these new geographical and economic settings was recently discovered in Santa Sofia (Vila Franca de Xira).18 Here, a low altitude habitat similar to those from the LBA was founded close to the Tagus shores during the early Iron Age (late 8th-early 7th century BCE). Its architectural features (ellipsoidal shaped huts) and majority of the material culture (handmade carinated cups, bowls and different types of pots) are indisputably related with the Lisbon’s Peninsula LBA horizon, although they are already associated with some orientalizing artifacts (red slip and grey ware, pithoi, and amphorae Ramon Torres type 10.1.1.1)19 (Fig. 3).

The terminal course of the Tagus estuary is, indeed, the preferential occupation area during the early Iron Age. The main habitat sites, specifically Alcáçova de Santarém, Lisbon and Quinta do Almaraz are all located on its shores, as well as others20 whose functions are yet difficult to assess, due to their premature destruction derived from recent agriculture activities, but revealed significant amounts of orientalizing materials.

7 Although most of these sites seem to have defensive structures, so far it is impossible to accurately determine their chronology. 8 The importance of these routes and commercial transactions is demonstrated by the recovery of a series bronze weights in Abrigo

Grande das Bocas, Penha Verde, Pragança and Castro da Ota: Vilaça 2003.

9 Personal information of Dr. Mário Monteiro.

10 Trindade – Ferreira 1965; Arruda 1999-2000, pp. 221-222; Cardoso 2004, p. 292. 11 Arruda 1999-2000, pp. 217-221; Arruda – Sousa in press.

12 Arruda et alii in press a.

13 Pimenta – Mendes 2010-2011, pp. 610-613.

14 Sousa 2013, pp. 103-104; Sousa 2014, p. 306; Arruda et alii in press b. 15 Strab. III 3,4.

16 Arruda 1999-2000, p. 102; Arruda 2005a, pp. 294-298. 17 Cardoso 2004, pp. 177-178.

18 Pimenta – Mendes 2010-2011, pp. 592-599.

19 Pimenta – Mendes 2010-2011, pp. 592-599; Pimenta – Soares – Mendes 2013, p. 187.

20 Alto do Castelo: Arruda et alii in press a; Porto do Sabugueiro: Pimenta – Mendes 2008, pp. 178-179; Eira da Alorna: Arruda et alii in press b; Alto dos Cacos: Pimenta – Henriques – Mendes 2012, pp. 36-38.

Fig. 2. Tagus estuary’s Orientalizing occupation; late 8th-mid 6th century BCE (cartographic base: Boaventura – Pimenta – Valles 2013, modified by the author).

In the Tagus estuary upper course, the main habitats, Alcáçova de Santarém21 and Alto do Castelo,22 have undoubtedly a previous LBA occupation, seeming that the Phoenician strategy has, in fact, used the local indigenous infrastructures in order to gain access to inner territories and important resources. However, in the terminal area of the estuary, a different situation seems to have taken place.

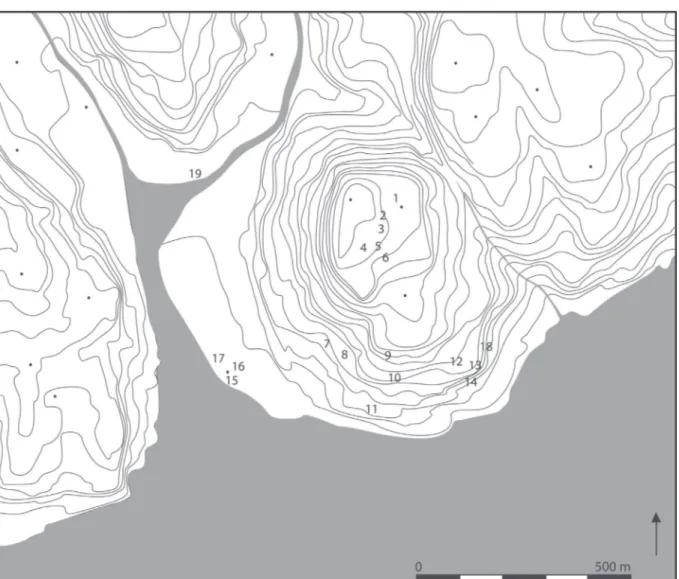

When we analyze the archaeological evidence of Lisbon during the beginning of the 1st millennium BCE, it becomes clear that a series of structural transformations occurred in the area. Its LBA occupation favored the lower areas of Praça da Figueira and Encosta de Sant´Ana (Fig. 4, n. 19), exhibiting features that allow its integration in the network of low altitude agricultural sites of the late 2nd-early 1st millennium BCE. However, with the arrival of Phoenician groups, the geographical setting of the habitat changes drastically.23 Lisbon’s Iron Age site will now occupy the hill of Castelo de São Jorge, particularly its southern slope (Fig. 4, nn. 1-18), a position that enables a strong visual domain and a direct control of the surrounding area, predominantly towards the Tagus riverbanks, clearly serving new economic strategies. This transformation occurs during the late 8th-early 7th century BCE, according to the oldest archaeological contexts found in the area, where a significant percentage of traditional LBA vessels were found in association with orientalizing materials (red-slip ware, amphorae Ramon Torres type 10.1.1.1, an urn type Cruz del Negro, a fragment of

21 Arruda – Sousa in press. 22 Arruda et alii in press a. 23 Sousa in press.

grey ware and a fibula fragment, possibly of the double-spring type)24 (Fig. 5).It seems, therefore, that the relocation of Lisbon’s habitat was a direct consequence of the Phoenician settlement in the area. Considering not only the features of this new location, but also other elements, such as the fast incorporation of new technologies, particularly the wheel-made pottery (in which were produced orientalizing amphorae, painted

pottery, red-slip and grey ware), that will quickly replace the local handmade productions,25 and the presence of an inscription in Phoenician characters,26 it seems possible to suggest that Lisbon’s Iron Age habitat

24 Pimenta – Silva – Calado 2014, pp. 727-730. 25 Sousa in press.

26 Arruda 2013, p. 216, p. 222; Zamora López 2013, p. 363.

Fig. 4. Lisbon’s Late Bronze (19 Praça da Figueira) and Iron age occupation (1 to 6: Castelo de São Jorge; 7: Rua das Pedras Negras; 8: Rua de São Mamede ao Caldas; 9: Roman Theater; 10: Cathedral; 11: Casa dos Bicos; 12: Pátio da Senhora da Murça; 13: Rua de São João da Praça; 14: Travessa do Chafariz d´El Rei; 15: Rua dos Correeiros; 16: Rua dos Douradores; 17 Rua Augusta; 18 Rua da

Fig. 5. Iron Age artifacts recovered in Rua de São Mamede ao Caldas (according to Pimenta – Silva – Calado 2014, modified by the author).

was indeed founded by western Phoenician settlers,27 and that it may have been their primary “base of operations” in the Tagus estuary.

It is likely that this settlement had a heterogeneous cultural composition, in which were integrated not only western Phoenician newcomers but also a significant part of the native population of Encosta de Sant´Ana/Praça da Figueira, as indicated by the mixed features of the archaeological materials found in the earliest occupation contexts of the Castelo de São Jorge’s hill.28 This type of situation seems, in fact, to be relatively frequent in Phoenician colonial enviorments, such as La Fonteta/La Rábita,29 Cerro del Villar30 and in Cádiz (Teatro Cómico).31

Another aspect that should be taken under consideration is the existence of an equally important site in the Tagus opposite shore, Quinta do Almaraz, located only 5 km away and that shares the same geographical features. There is some (scarce) evidence that the site had a previous LBA occupation, although, once more, not in the area that will be occupied by the Iron Age settlement.32 It has a smaller extension when compared to Lisbon, although it shows some defensive care, namely with the construction of two lines of defensive walls associated with a ditch.33 The artifactual data shows a clear connection between both shores, and the strategic position of these settlements seem to function symbiotically in order to control the terminal course of the Tagus river. As we have already argued,34 there is a strong possibility that both sites (Lisbon and Quinta do Almaraz) may have been, during the Iron Age, a single urban political-administrative cell. An interesting aspect to highlight is the recovery of several exceptional artifacts (alabaster vases, ivory plaque, Egyptian scarab, Middle Corinthian vessels, cubic bronze weights, etc.) at Quinta do Almaraz35 (Fig. 6) which, along with the defensive concerns previously mentioned, could suggest the residence of a social-political elite of this cell in the area, at least until the 6th century BCE.

Between the 8th and 6th century BCE the situation in the Tagus estuary seems to remain considerably stable, featuring the exploitation of the river’s shores and an intense contact network that linked the respective settlements.

3. The 6th Century Crisis and the Development of a New Regional Framework

It is during the late 6th century BCE that we witness, once again, the emergence of radical transformations that will, once again, sweep through the Tagus estuary infrastructures. It is undoubtedly tempting to associate this phenomena with the so-called “6th century crisis”,36 which encompassed a whole new series of drastic transformations that changed the main Phoenician colonial spheres in the Iberian Peninsula and that appear to have lead to the emergence of different regional settings that shared a common orientalizing background. Such a scenario is clearly visible both in the southern Iberian coast, in the post-orientalizing interior and, it seems, also in the central western Atlantic area. In this case, the consequences of the “6th

27 Sousa in press.

28 Pimenta – Silva – Calado 2014, pp. 727-730.

29 Rouillard – Gailledrat – Sala Sellés 2007; Azuar et alii 1998; González Prats 1998. 30 Aubet et alii 1999; Delgado – Ferrer 2007.

31 Cfr. note 1.

32 Barros – Sabrosa – Santos 1994. 33 Barros 1998, p. 36.

34 Sousa 2014, p. 309.

35 Barros 1998, p. 40; Barros – Soares 2004, p. 340. 36 Martín Ruiz 2007; Ordóñez Fernández 2011.

century crisis” seems to have resulted in some decrease of commercial contacts with other geographical

Fig. 6. Alabaster vases, fragments of Middle Corinthian vessels (nn. 1, 2), Egyptian scarab (n. 3) and ivory plaque (n. 4) from Almaraz (according to Cardoso 2004, modified by the author).

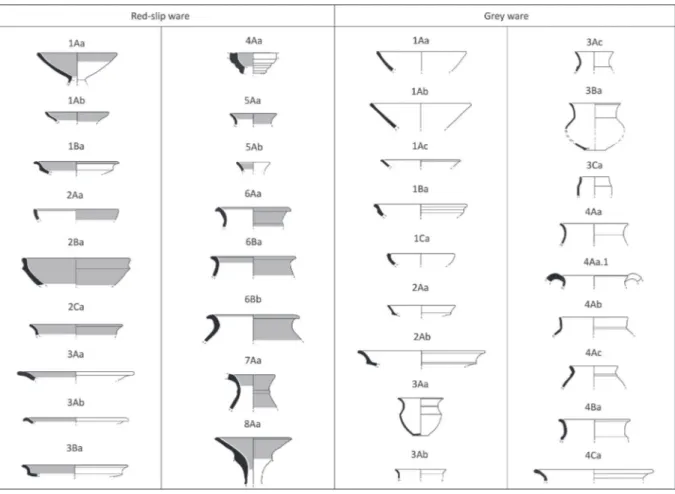

areas,37 which is stated by the rare presence of ceramic imports, particularly Greek pottery38 and amphorae.39 At the same time, and partially as a consequence of this progressive isolation, we observe the emergency and consolidation of a diversified ceramic repertoire that presents unique regional features40 (Figs. 7-8).It is also important to specify that this regional repertoire included a significant amphorae production (Fig.

9) that encompasses several hundred vessels, a reality that implies, according to Guerrero, the existence of a complex social structure capable of generating and control agricultural surplus and a developed commercial network.41 Simultaneously, the settlement pattern suffers, yet again, structural changes that, coincidently or not, recover the strategies used during the LBA. As a matter of fact, during the late 6th-5th century BCE we observe the foundation of a series of small low altitude settlements42 in the “Lisbon’s basaltic complex” (Fig. 10), quite probably focused in agricultural and husbandry activities, that seem to depend upon Lisbon/

37 This commercial marginalization may be explained by the devaluation of metallic resources, which would no longer compensate

the investment and maintenance of such long distance networks: Arruda 2005b, p. 83; Sousa 2014, p. 308

38 So far, the sum of Greek pottery findings in Lisbon, Almaraz and Alcáçova de Santarém does not exceed 29 fragments. 39 Sousa 2014, pp. 109, 308.

40 Sousa 2014, pp. 105-106, 129, 144, 182-184; Sousa 2013; Sousa – Pimenta 2014. 41 Guerrero 1991, p. 73.

42 As well as others with more prominent geographical characteristics that seem to locally structure this settlement network, such

as Santa Eufémia, Castelo dos Mouros and Baútas: Sousa 2014, p. 255, 273.

Almaraz, judging by the characteristics of their material culture.43 In spite of the marginalization from long distance commercial networks the Tagus estuary communities show not only a remarkable resilience but also the capacity of re-adaptation to new economic settings, being able to rebuild a complex and self-sufficient regional framework whose cultural and identity markers enable its individualization among other spheres in the Iberian Peninsula.44

4. Searching Identity Markers

among the Archaeological Record of the Tagus Estuary

Once provided the general framework of the Tagus estuary human occupation during the 1st half of the 1st millennium BCE, we are left with the difficult task of trying to identify the active agents involved in the Tagus estuary orientalization process and to trace the respective identity markers through the archaeological data.

The most prominent active agents are, without a doubt, the Phoenician newcomers that reached the

43 The material culture of these small low altitude sites is mainly constituted by imports from the Lisbon/Almaraz area: Sousa 2014,

p. 284.

44 Sousa 2014, pp. 306-310.

center Atlantic area during the late 8th century BCE. One cannot forget that we are probably dealing with descendants of the first colonial waves that settled in southern Andalusia during the early 1st millennium BCE.

Fig. 10. Tagus estuary’s mid 1st millennium BCE occupation

Fig. 11. Burnished decorations on handmade (nn. 1-2: Alcáçova de Santarém; Arruda 1999-2000, p. 177, fig. 112), common (n. 3: Alcáçova de Santarém; Arruda 1999-2000, p. 203, fig. 140) and grey ware (n. 4: Sé de Lisboa; Arruda – Freitas – Vallejo Sanchez 2000, p. 40, fig. 13, n. 10); painted reticle motives in red-slip (n. 10: Alcáçova de Santarém; Arruda 1999-2000, p. 189,

fig. 121; n. 11: Teatro Romano de Lisboa; Calado et al. 2013b, p. 649, fig. 5, n. 27) and painted ware (nn. 5-7: Sé de Lisboa; Arruda 1999-2000, p. 122, fig. 75; n. 8: Sé de Lisboa; Arruda 1999-2000, p. 118, fig. 69; n. 9: Chafariz d’El Rei;

Their adaptation to a new environment and the necessary entanglement with local indigenous communities has certainly promoted drastic alterations in the social-cultural fabric of these “western Phoenicians”. They cannot be seen as a homogenous group, considering that they surely encompassed different social elements and specific expertise,45 which are, however, difficult to differentiate through the available data.46 What we can in fact perceive is the success of technological innovations that they brought, namely the wheel made pottery and decoration technics, metallurgical, agricultural and architectonic advances and the introduction of writing.

In the lower area of the Tagus estuary, the wheel made pottery was easily apprehended and actually dominates the archeological record after the 7th century BCE,47 including not only foreign products (especially amphorae from southern Andalusia) but mainly local productions of amphorae, red-slip and grey

ware (bowls and plates) as well as common (cooking pots) and painted ware (pithoi, type Cruz del Negro urns,

“chardon” vases), that spread through the entire region during the Iron Age. Metallurgic transformations were also an important element directly linked to the arrival of these orientalizing groups. The introduction of iron metallurgy is well documented in Almaraz,48 as well as other innovations in terms of bronze and gold work and especially in the silver cupellation process.49 In terms of agricultural innovations, and although we still lack specific data from most Iron Age sites, pollen analysis from the upper Tagus estuary show that the domestication of olive trees and vineyard occurred after the mid 7th century BCE,50 and therefore can be directly associated with the Phoenician presence in the area. The study of faunal remains recovered in Alcáçova de Santarém show also the incorporation of chicken and donkey during the Iron Age,51 species which were previously unknown in the area. Architectural innovations deriving from the arrival of these “western Phoenician” groups are also clearly translated in the building of rectangular plant constructions that are common in the Tagus territory during the 1st millennium BCE. Last but not the least, the evidence related with the introduction of writing. So far, a single inscription in Phoenician characters52 was recovered in this area, specifically in the Castelo de São Jorge’s hill, in Lisbon. It is important to stress out the fact that this inscription was made on what seems to be a local amphorae fragment and, therefore, demonstrates the

existence of literate individuals among this population.

There is no doubt that the Phoenician cultural markers are dominant during the early Iron Age (late 8th-6th century BCE) in the Tagus estuary and have, particularly in a historiographical point of view, somehow obscured the native agents and their traditions. However, some local customs have, in fact, survived these radical changes and are observable across the archaeological record.

However, a preliminary reflection concerning the nature of these native influences is in order. On one hand, we have the local Tagus estuary LBA communities that interacted with the Phoenician groups. On the other, we cannot disregard the possibility of a third set of active agents, namely groups of Andalusian indigenous communities that could have travelled or be an actual part of these “western Phoenicians” settlers. As it was already stated, studies conducted in southern Iberia have revealed an effective integration of local

45 Leaders, priests, traders, potters, seafarers, etc.

46 The absence of knowledge concerning funerary or religious contexts in the area poses a serious obstacle in trying to discern this

presumed heterogeneity.

47 Sousa in press.

48 Melo et alii 2013, p. 700.

49 Melo et alii 2013, pp. 702-706; Valério et alii 2012, p. 77. 50 Leeuwaarden – Jansen 1985; Arruda 1999-2000, p. 21. 51 Davis 2003, pp. 26, 38.

groups in several Phoenician colonial environments such as Cadiz,53 Cerro del Villar54 and La Fonteta.55 Therefore, we believe that it is highly probable that some of these elements could have actually integrated the colonial wave that reached the Tagus estuary during the late 8th century BCE. The cultural markers left by these agents is somewhat more complex to identify, particularly in terms of its individualization concerning the native Tagus estuary communities. Let us take as an example the use of burnished decorations, a technic that was fairly common across most of the Iberian LBA. In the Tagus estuary, this type of decoration was primarily used in the vessels external surface (type “Lapa do Fumo”)56 while in Andalusia vases with internal burnished decorations prevailed. The use of this technic did not disappear in the Tagus estuary Iron Age, and was applied not only in hand-made pottery,57 but also in wheel-made vases,58 a situation that allows foreseeing a strong entanglement between the range of active agents. It is, however, curious that, instead of prolonging the regional tendency for the external application of this type of decoration, the burnished decorations that appear in Iron Age Tagus contexts are mostly located in the vases interior surface, which might suggest an influence by native Andalusian groups59 (Fig. 11).It is also interesting to observe that the tradition of reticle motives was successfully incorporated among the regional orientalizing pottery tradition, being, in this case, applied with painted decoration in the surfaces of red-slip ware,60pithoi,61 and type Cruz del Negro urns,62 revealing, once again, the dynamic interactions between different cultural elements in the Tagus estuary Iron Age.63 Another element than can be associated with the Andalusian world is translated in Lisbon’s ancient toponym, Olisipo. Although it is known only through literary data dating from the

Roman period, the origin of this toponym probably goes back to a much earliest phase. The suffix –ipo is

well documented in the Guadalquivir area,64 and its presence in the western Atlantic coast of Iberia has been systematically interpreted as evidence of its Tartessic colonization.65 It is our belief that a different scenario could have taken place, and that the frequency of this linguistic element can be justified either by the presence of groups from the southern Andalusia area that arrived with the western Phoenician settlers, or by the nature of this latter community, that, as it was already stated, was fixated for at least a century in southern Iberia before reaching the Tagus shores, and it may have adopted certain southern local linguistic elements.

Among the archaeological evidence from the earliest Iron Age contexts of the Tagus estuary, the maintenance of local elements is also clear. The most tangible data is observable through the native pottery traditions that endure during the first Iron Age centuries. In what we presume to be colonial environments, these productions are significant during the earliest phase of occupation (late 8th-early 7th century), and

53 Cfr. note 1.

54 Aubet et alii 1999; Delgado – Ferrer 2007.

55 Rouillard – Gailledrat – Sala Sellés 2007; Azuar et alii 1998; González Prats 1998. 56 Serrão 1958.

57 Arruda 1999-2000, p. 177.

58 Arruda 1999-2000, p. 203; Arruda – Freitas – Vallejo Sanchez 2000, pp. 40, 44.

59 This influence is, in a smaller degree, already visible previous to the Iron Age, as is testified by the presence of internal burnished

decorations in two LBA fragments from Alcaçova de Santarém and in a carinated bowl recovered in Quinta do Marcelo: Arruda – Sousa in press; Barros 1998, p. 31; Arruda 1999-2000, pp. 183-184.

60 Arruda 1999-2000, p. 118, fig. 69; p. 189, fig. 121.

61 Arruda 1999-2000, p. 122, fig. 75; Calado et alii 2013a, p. 127, fig. 8; Filipe – Calado – Leitão 2014, p. 741, fig. 7. 62 Pimenta – Sousa – Amaro in press.

63 These decorative features, both burnished and painted, remain in the local archaeological record throughout the entire Iron Age:

Sousa 2014, p. 180; Pimenta – Calado – Leitão 2014, pp. 720-721.

64 Torres Ortiz 2005, pp. 195-196; Almagro Gorbea – Torres Ortiz 2009, pp. 119-122. 65 Torres Ortiz 2005; Almagro Gorbea – Torres Ortiz 2009; Torres Ortiz 2013.

indicate that a significant part of the native population instated the process of foundation of the Iron Age settlements,66 even if, in later times, orientalizing products and technics replaced such traditions. However, in LBA sites that transited into the Iron Age, such as Alcáçova de Santarém, the local handmade pottery traditions dominate the archaeological record, with percentages superior to 80%,67 retaining typical morphological and decorative features from the previous phase (carinated bowls and other types, incised decorations over the rim, the previously referred burnished patterns). The endurance of native traditions can also be traced in certain practices such as the continuous use of natural caves68 that probably embedded strong ritual significance, considering the features and quality of the associated artifacts. The origin of this type of practice is traceable, at least, to the LBA and is wide spread across the Portuguese territory69 although there is sufficient data to sustain that this traditions were not abandoned in the central Atlantic western coast during the following period, as it is perceivable in Gruta do Correio Mor (Oeiras),70 Poço Velho (Cascais)71 or in Lapa do Fumo (Sesimbra).72 Also, one cannot help wondering if the shifting in terms of settlement patterns and economic strategies that took place in the area during the late 6th century BCE, with the retrieval of the LBA territorial occupation models, was influenced by an ancient collective memory that endured throughout the early Iron Age, being now applied by a strongly entangled cultural population in which it was no longer possible to differentiate distinct origins.

The different values, traditions and practices that were originally carried out by the different sets of active agents involved in the Tagus estuary orientalization process were integrated in a complex cultural “melting pot” in which certain specific elements were valued, while others were depreciated, transformed, reinterpreted or adapted in different ways by different social and individual segments. Even if it is impossible to trace and identify the entire intricacy of cultural influences, the Tagus estuary archaeological record enables us to recognize the existence of different markers that, after the mid 1st millennium BCE, melted into a unique identity sphere that stands out across other contemporary Iberian Iron Age scenarios.

5. Conclusion

The construction of this article is based on the premise that the material culture is somehow able to reflect alterations that took place both in the ancient communities everyday habits and in their broader economic, commercial and cultural circuits. We are not naïve enough to think we are able to recover the full extension and diversity of the past, but we are optimist that some cultural traditions are in fact fossilized in the archaeological data and that we are able to at least come close to their significance, even if aware that we cannot encompass all its original meaning. Besides these inherent limitations, the study of the evolution of the Tagus estuary during the 1st millennium BCE also collides with the shortage of specific contextual data, which could enable more accurate interpretations based on everyday habits (cooking techniques, trends in food consumption, internal habitat structures) and ritual practices (specifically in terms of funerary and religious contexts) and therefore allow a more substantiated appraisal of the range of different agents that

66 Sousa in press. 67 Arruda 1999-2000, p. 173. 68 Gomes – Calado 2007, p. 150. 69 Gomes – Calado 2007, pp. 150-154. 70 Cardoso 2003, pp. 260-261. 71 Gonçalves 2008. 72 Arruda – Cardoso 2013, pp. 736-749.

interacted and took part in the construction of the area’s cultural identity scenarios. We must hope that in the future this data may be available in order to develop the study of identity markers in all its degrees (from personal and individual spheres to wider communitarian awareness).

Nonetheless, we believed that a complex range of reciprocal influences took place during the early Iron Age in Iberia’s central western Atlantic coast, involving different active agents, ultimately resulting in the adaptation, transformation and merging of both local and foreign cultural values, practices and traditions. Across this article, we have tried to distinguish these elements through the available archaeological evidence, as well as the cultural markers they might have left behind, which we believe to have been crystallized in different alterations that took place in scenarios such as the strategies of territorial exploration and occupation and in the production of material culture. We know that this issue is far from being depleted and that new data can either confirm, deny or enable further interpretations upon subjects previously developed.73

References

Almagro-Gorbea – Torres Ortiz 2009 = M. Almagro-Gorbea – M. Torres Ortiz, La colonización de

la costa atlântica de Portugal: Fenícios o tartesios?, in «Paleohispánica» 9, 2009, pp. 113-142.

Arruda 1999-2000 = A.M. Arruda, Los Fenicios en Portugal. Fenicios y mundo indígena en el centro y sur de

Portugal (siglos VIII–VI a. C.), Barcelona 1999-2000.

Arruda 2005a = A.M. Arruda, Orientalizante e pós-orientalizante no Sudoeste peninsular: geografías e

cronologías, in S. Celestino Pérez – J. Jiménez Ávila (edd.), El Periodo Orientalizante. Actas del III Simposio Internacional de Arqueología de Mérida: Protohistoria del Mediterráneo Occidental, Mérida

2005, pp. 277-304.

Arruda 2005b = A.M. Arruda, O 1º milénio a.n.e. no Centro e no Sul de Portugal: leituras possíveis no início

de um novo século, in «APort» sér. 4, 23, 2005, pp. 9-156.

Arruda 2013 = A.M. Arruda, Do que falamos quando falamos de Tartesso, in J. Campos – J. Alvar (edd.),

Tarteso. El emporio del metal, Madrid 2013, pp. 211-222.

Arruda – Cardoso 2013 = A.M. Arruda – J.L. Cardoso, A ocupação da Idade do Ferro da Lapa do Fumo

(Sesimbra), in «Estudos Arqueológicos de Oeiras» 20, 2013, pp. 731-654.

Arruda – Freitas – Vallejo Sanchéz 2000 = A.M. Arruda – V. Freitas – J. Vallejo Sánchez, As

cerámicas cinzentas da Sé de Lisboa, in «RPortA» 3, 2000, pp. 25-59.

Arruda – Sousa in press = A.M. Arruda – E. Sousa, Late Bronze Age in Alcáçova de Santarém (Portugal), in press.

Arruda et alii in press a = A.M. Arruda – E. Sousa – J. Pimenta – H. Mendes – R. Soares, Alto do

Castelo’s Iron Age occupation (Alpiarça, Portugal), in press.

Arruda et alii in press b = A.M. Arruda – E. Sousa – J. Pimenta – R. Soares – H. Mendes, Phéniciens et

indigènes en contact à l´embouchure du Tage, Portugal, in press.

Aubet et alii 1999 = M.E. Aubet – P. Carmona – E. Curià – A. Delgado – A. Fernández Cantos – M. Párraga, Cerro del Villar. 1. El asentamiento fenício en la desembocadura del rio Guadalhorce y su

73 After the submission of this paper, a second Phoenician inscription was discovered in Lisbon (N. Neto – P. Rebelo – R. Ribeiro

– M. Rocha – J.Á. Zamora LÓpez, Uma inscrição lapidar fenícia em Lisboa, in «RPortA» 19, 2016, pp. 123-128), apparently of funerary nature, which is yet another element that highlights the importance of the “Orientalizing” cultural markers in this settlement.

interacción com el hinterland, Sevilla 1999.

Azuar et alii 1998 = R. Azuar – P. Rouillard – E. Gailledrat – F. Sala Sellés – A. Badie, El asentamiento

orientalizante e ibérico antiguo de “La Rabita” (Guardamar del Segura, Alicante). Avance de las excavaciones 1996-1998, in «TrabPrehist» 55, 1998, pp. 111-126.

Barros 1998 = L. Barros, Introdução à Pré e Proto-História de Almada, Almada 1998.

Barros – Sabrosa – Santos 1994 = L. Barros – A. Sabrosa – V. Santos, Almada, in «Informação

Arqueológica» 9, 1994, pp. 135-136.

Barros – Soares 2004 = L. Barros – A.M. Soares, Cronologia absoluta para a ocupação orientalizante da Quinta do Almaraz, no estuário do Tejo (Almada, Portugal), in «APort» sér. 4, 22, 2004, pp. 333-352.

Boaventura – Pimenta – Valles 2013 = R. Boaventura – J. Pimenta – E. Valles, O povoado do Bronze Final do Castelo da Amoreira, in «Estudos Arqueológicos de Oeiras» 20, 2013, pp. 389-406.

Calado et alii 2013a = M. Calado – L. Almeida – V. Leitão – M. Leitão, Cronologias absolutas para a Iª Idade do Ferro em Olisipo – o exemplo de uma ocupação em ambiente cársico na actual Rua da Judearia em Alfama, in «Cira» 2, 2013, pp. 118-132.

Calado et alii 2013b = M. Calado – J. Pimenta – L. Fernandes – V. Filipe, Conjuntos cerâmicos da Idade do Ferro do Teatro Romano de Lisboa: as cerâmicas de engobe vermelho, in J. Arnaud – A. Martins – C.

Neves (edd.), Arqueologia em Portugal. 150 anos, Lisboa 2013, pp. 641-649.

Cardoso 2003 = J.L. Cardoso, A gruta do Correio-Mor, in «Estudos Arqueológicos de Oeiras» 11, 2003,

pp. 229-321.

Cardoso 2004 = J.L. Cardoso, A Baixa Estremadura dos Finais do IV milénio a. C. até à chegada dos romanos. Um ensaio de história regional, Oeiras 2004.

Davis 2005 = S. Davis, Faunal remains from Alcáçova de Santarém, Portugal, Lisboa 2005.

Delgado – Ferrer 2007 = A. Delgado – M. Ferrer, Cultural Contacts in Colonial Settings. The Construction of New Identities in Phoenician Settlements of the Western Mediterranean, in «Stanford Journal of

Archaeology» 5, 2007, pp. 18-42.

Filipe – Calado – Leitão 2014 = V. Filipe – M. Calado – M. Leitão, Evidências orientalizantes na área urbana de Lisboa. O caso dos edifícios na envolvente da Mãe de Água do Chafariz d’El Rei, in A.M.

Arruda (ed.), Fenícios e Púnicos, por terra e mar. Actas do VI Congresso Internacional de Estudos Fenícios e Púnicos (Lisboa, 25 de Setembro a 1 de Outubro de 2005), Lisboa 2014, vol. 2, pp. 736-747.

Gomes – Calado 2007 = M.V. Gomes – D. Calado, Conjunto de cerâmicas da gruta da Ladroeira Grande (Moncarapacho, Olhão, Algarve) e os santuários subterrâneos, da Idade do Bronze Final, no sul de Portugal,

in «RPortA» 10, 2007, pp. 141-158.

Gonçalves 2008 = V.S. Gonçalves, As ocupações pré-históricas das Furnas do Poço Velho (Cascais), Cascais

2008.

González Prats 1998 = A. González Prats, La Fonteta. El asentamiento fenicio de la desembocadura del río Segura (Guardamar, Alicante, España). Resultados de las excavaciones de 1996/1997, in «RStFen» 26,

1998, pp. 191-228.

Guerra 1998 = A. Guerra, Nomes pré-romanos de povos e lugares do Ocidente Peninsular (Dissertação de

doutoramento), Lisboa 1998.

Guerrero 1991 = V. Guerrero, El palacio-santuario de Cancho Roano (Badajoz) y la comercialización de ánforas fenícias indígenas, in «RStFen» 19, 1991, pp. 49-81.

Leeuwaarden – Jansen 1985 = W. Leeuwaarden – C. Janssen, A Preliminar Palynological Study of Peat Deposit Near an Oppidum in the Lower Tagus Valley, in Actas da I reunião do Quaternário Ibérico, Lisboa

1985, pp. 225-235.

Martín Ruiz 2007 = J.A. Martín Ruiz, La crisis del siglo VI a. C. en los asentamientos fenícios de Andalucía, Málaga 2007.

Melo et alii 2014 = A. Melo – P. Valério – L. Barros – M. Araújo, Práticas metalúrgicas na Quinta do Almaraz (Cacilhas, Portugal): vestigios orientalizantes, in A.M. Arruda (ed.), Fenícios e Púnicos, por terra e mar. Actas do VI Congresso Internacional de Estudos Fenícios e Púnicos (Lisboa, 25 de Setembro a 1 de

Outubro de 2005), Lisboa 2014, vol. 2, pp. 724-735.

Ordóñez Fernández 2011 = R. Ordóñez Fernández, La Crisis del siglo VI a. C. en las colonias fenicias del Occidente Mediterráneo. Contracción económica, concentración poblacional y cambio cultural (Dissertação

de doutoramento), Oviedo 2011.

Pimenta – Mendes 2008 = J. Pimenta – H. Mendes, Descoberta do povoado pré-romano de Porto do Sabugueiro (Muge), in «RPortA» 11, 2008, pp. 171-194.

Pimenta – Mendes 2010-2011 = J. Pimenta – H. Mendes, Novos dados sobre a presença fenícia no vale do Tejo. As recentes descobertas na área de Vila Franca de Xira, in «Estudos Arqueológicos de Oeiras» 18,

2010-2011, pp. 591-618.

Pimenta – Henriques – Mendes 2012 = J. Pimenta – E. Henriques – H. Mendes, O Acampamento romano do Alto dos Cacos (Almeirim), Almeirim 2012.

Pimenta – Soares – Mendes 2013 = J. Pimenta – A.M. Soares – H. Mendes, Cronologia absoluta para o povoado pré-romano de Santa Sofia (Vila Franca de Xira), in «Cira» 2, 2013, pp. 181-195.

Pimenta – Silva – Calado 2014 = J. Pimenta – R. Silva – M. Calado, Sobre a ocupação pré-romana de Olisipo. A intervenção arqueológica urbana da Rua de São Mamede ao Caldas n. 15, in A.M. Arruda

(ed.), Fenícios e Púnicos, por terra e mar. Actas do VI Congresso Internacional de Estudos Fenícios e Púnicos

(Lisboa, 25 de Setembro a 1 de Outubro de 2005), Lisboa 2014, vol. 2, pp. 712-723.

Pimenta – Sousa – Amaro in press = J. Pimenta – E. Sousa – C. Amaro, Sobre as mais antigas ocupações da Casa dos Bicos – Lisboa, in press.

Rouillard – Gailledrat – Sala Sellés 2007 = P. Rouillard – E. Gailledrat – F. Sala Sellés,

L´établissement protohistorique de La Fonteta (fin VIIIe – fin VIe siècle av. J.C.), Madrid 2007.

Serrão 1958 = E. Serrão, Cerâmica proto-histórica da Lapa do fumo (Sesimbra), com ornatos coloridos e brunidos, in «Zephyrus» 9, 1958, pp. 177-186.

Silva 2013 = R. Silva, A ocupação da Idade do Bronze Final da Praça da Figueira (Lisboa). Novos e velhos dados sobre os antecedents da cidade de Lisboa, in «Cira» 2, 2013, pp. 40-62.

Sousa 2013 = E. Sousa, A ocupação da foz do Estuário do Tejo em meados do 1º milenio a.C., in «Cira» 2,

2013, pp. 103-117.

Sousa 2014 = E. Sousa, A ocupação pré-romana da foz do Estuário do Tejo, Lisboa 2014.

Sousa – Pimenta 2014 = E. Sousa – J. Pimenta, A produção de ânforas no Estuário do Tejo durante a Idade do Ferro, in R. Morais – A. Fernández – M.J. Sousa (edd.), As Produções Cerâmicas de Imitação na Hispânia, Porto 2014 («Monografias Ex Officina Hispana», 2), pp. 303-316.

Sousa in press = E. Sousa, The Iron Age Occupation of Lisbon, in press.

Torres Ortíz 2005 = M. Torres Ortíz, Una colonización tartésica en el interfluvio Tajo-Sado durante la Primera Edad del Hierro?, in «RPortA» 8, 2005, pp. 193-213.

Torres Ortíz 2013 = M. Torres Ortíz, Fenicios y Tartesios en el Interfluvio Tajo-Sado durante la I Edad del Hierro, in A.M. Arruda (ed.), Fenícios e Púnicos, por terra e mar. Actas do VI Congresso Internacional de Estudos Fenícios e Púnicos (Lisboa, 25 de Setembro a 1 de Outubro de 2005), Lisboa 2013, vol. 1, pp.

448-460.

Valério et alii 2012 = P. Valério – R. Silva – M. Araújo – A. Soares – L. Barros, A Multianalytical

Approach to Study the Phoenician Bronze Technology in the Iberian Peninsula. A View from Quinta do Almaraz, in «Material Characterization» 67, 2012, pp. 74-82.

Vilaça 2003 = R. Vilaça, Acerca da existência de ponderais em contextos do Bronze Final/Ferro Inicial no

território português, in «APort» sér. 4, 21, 2003, pp. 245-288.

Trindade – Ferreira 1965 = L. Trindade – O.V. Ferreira, Acerca do vaso “piriforme” tartéssico de bronze

do Museu de Torres Vedras, in «Boletim Cultural da Junta Distrital de Lisboa» 63-64, 1965, pp. 175-183.

Zamora López et alii 2010 = J.Á. Zamora López – J.M. Gener Basallote – M.A. Navarro García – J.M. Pajuelo Sáez – M. Torres Ortiz, Epígrafes Fenicios arcaicos en la excavación del Teatro Cómico de

Cádiz (2006–2010), in «RStFen» 38, 2010, pp. 203-236.

Zamora López 2013 = J.Á. Zamora López, Novedades de Epigrafía Fenicio-Púnica en la Península Ibérica y