Cost Reductions on Returns: an eTailer’s Perspective

Tomás Palhinhas Cruz Vieira Dissertação de Mestrado

Orientador na FEUP: Prof. Pedro Sanches Amorim

Mestrado Integrado em Engenharia Gestão Industrial 2017-06-25

Redução de Custos nas Devoluções: uma Perspetiva de um eTailer

Resumo

As devoluções fazem parte do dia-a-dia de qualquer empresa de retalho. Tipicamente são vistas pelas próprias empresas como um grande custo, contudo, muitas organizações olham agora para as devoluções como uma forma de aumentar a qualidade do serviço, a lealdade dos seus clientes e a sua própria competitividade. Esta tendência de implementação de políticas mais flexíveis está diretamente relacionada com um aumento da taxa das devoluções. Os produtos devolvidos representam então um enorme desafio e uma ótima oportunidade de melhoramento de experiencia de consumo.

A Farfetch não é exceção. O aumento acentuado no volume de encomendas, assim como o modelo de entrega drop shipping que pratica, contribuem para toda a complexidade do processo. Além disso, aliando as altas taxas de devoluções dos negócios de eCommerce e do sector de retalho, as devoluções são um fator essencial para a empresa. A primeira oferta pública de venda é um dos próximos passos da Farfetch, sendo que agora, mais do que nunca, procura rentabilidade para um ótimo início no mercado de ações.

Esta dissertação tem como objetivo analisar e caracterizar os processos atuais, descobrir áreas de oportunidade e propor soluções de forma a reduzir os custos das devoluções. A primeira proposta de solução é a modificação do tipo de serviço de entrega, que conta com a criação de uma regra que define qual serviço usar em que rotas. A flexibilidade deste método permite a gestão da agressividade desejada na redução de custos. A segunda proposta analisa e identifica alternativas para a mudança do país de transbordo de certas devoluções.

Ambas as soluções prevêem reduções de custo significativas, conseguindo minimizar quaisquer impactos negativos. Apesar de não terem sido executadas durante a duração do projeto, a implementação das propostas apresentadas está a ser estudada por parte da empresa.

Abstract

Returns are a part of any retailing company. Typically seen as a cost drain, many firms are now looking at returns as a way to increase service level, customer loyality and competitiveness. This tendency for more lenient policies is also driving return rates to unprecedented levels. Returned items can therefore make up a very challenging and resource consuming procedure. For Farfetch, this is no exception. The exponential growth in terms of volume of orders combined with the drop shipping delivery mode employed, add to the complexity of the process. Moreover, combining the high return rates of eCommerce businesses and of the retailing sector, returns are a key activity for the company. Having an Initial Public Offer as the next financial milestone, Farfetch is looking for profitability in order to lauch a successful stock market start. This dissertation aims to analyse and characterize present procedures, pinpointing areas of opportunity and proposing cost saving solutions for the current returns. The first proposal, a modification in delivery service type, includes a trigger that defines the service to be used. The flexibility of the method allows for controlling the disruptiveness of the change, according to the desired aggressiveness of approach. The second proposal analyses and identifies alternatives for the transhipment country used by Farfetch.

Both approaches predict significant cost reductions, while keeping negative impacts to a minimum. Despite not being executed during the extent of the project, the proposed changes to the current return framework are being examined for implementation.

Acknowledgments

First of all, I would like to thank my parents for supporting me in every situation, encouraging me to always make the best of my education and to push myself to my limits. To my girlfriend, for the endless love, support and motivation that always made me go one step further.

I would also like to thank Farfetch for receiving me so well, for making all of the resources available for me to pursue the goal of my dissertation. In particular to my manager, Pedro Bastos, who supervised me closely and from whom I learned so much. To all of the Delivery Team members, Joana, Inês, Luisa, Ana and Wilson for the patience and for always giving me valuable input and for helping me on a daily basis.

Finally, a very special thank you to Pedro Amorim for the guidance and strategic insights for delivering the best possible end product.

Contents

1 Introduction ... 1 1.1 Farfetch ... 1 1.2 Project ... 2 1.3 Methodology ... 3 1.4 Structure ... 42 State of the Art ... 5

2.1 Reverse Logistics ... 5

2.2 Return Policy ... 7

3 Description of Current Situation ... 10

3.1 Ordering Process at Farfetch ... 10

3.2 Returns Overview ... 12

3.2.1 RTO - “Return to Origin” ... 12

3.2.2 Returned by User ... 13 3.3 Return Policy ... 14 3.3.1 Customer Responsibility ... 14 3.3.2 Farfetch Responsibility ... 15 3.4 Return Process ... 15 3.5 Cost Structure ... 17 3.5.1 Costs ... 17 3.5.2 Revenue ... 17

3.6 Carriers and Shipping Services ... 18

3.7 Return Transhipment ... 19

3.8 Geographic Analysis ... 19

4 Proposed Solutions ... 22

4.1 Delivery Service Change ... 22

4.1.1 Solution Overview ... 22

Return Times ... 22

4.1.2 Express vs Standard Delivery ... 22

Cost ... 23

Speed ... 23

4.1.3 Implications ... 24

Late Return ... 24

Increase in Lead Time ... 25

4.1.4 Returns Intra EU ... 27

Return Time Breakdown ... 27

Breakdown Analysis ... 28

Cost and Time Effects ... 29

4.1.5 Returns Via UK ... 31

Return Time Breakdown ... 31

Breakdown Analysis ... 32

Dependency on Return Request Time and Rule Creation ... 33

Cost and Time Effects ... 35

4.2 Transhipment via Different Country ... 37

4.2.1 Solution Overview ... 37

4.2.2 Cost and Time Effects ... 38

5 Conclusions and Future Work ... 40

Figure 1 - Evolution of Orders and % of Returns Over Time ... 3

Figure 2 - Deming Cycle ... 4

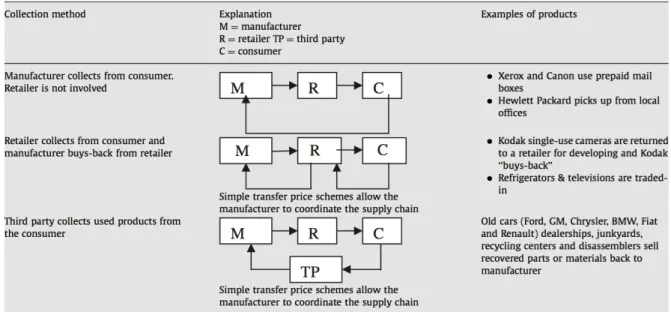

Figure 3 - Collection Methods in Kumar, Cradle to cradle: Reverse logistics strategies and opportunities across three industry sectors, 2008 ... 6

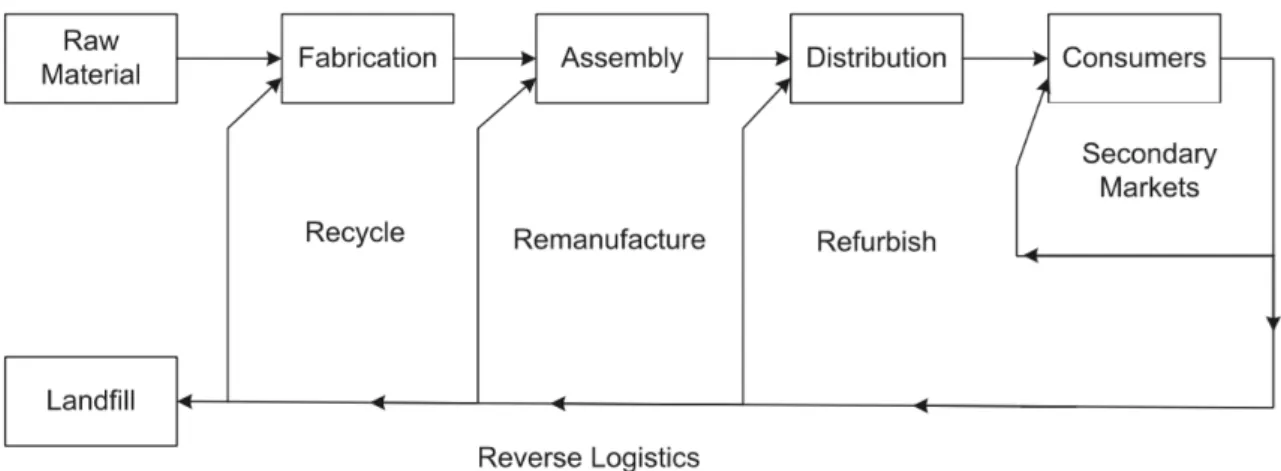

Figure 4 - Reverse Item Flow in Kumar, Cradle to cradle: Reverse logistics strategies and opportunities across three industry sectors, 2008 ... 7

Figure 5 - Impacts of Return Policy in Klas Hjort, Return Policies on eFashion, 2016 ... 7

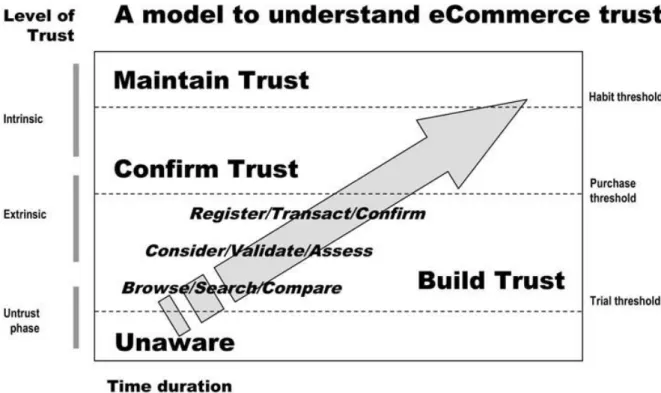

Figure 6 - Relation between Trust and Repurchase in Anton Eremeev, eCommerce Trust Study, 1999... 9

Figure 7 - Division of Portal Orders into Boutique Orders ... 10

Figure 8 - Illustration of Order Processing ... 10

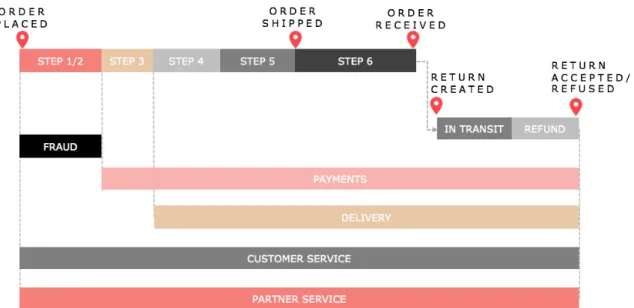

Figure 9 - Departments' Span of Action ... 12

Figure 10 - Reasons for Returns by User ... 14

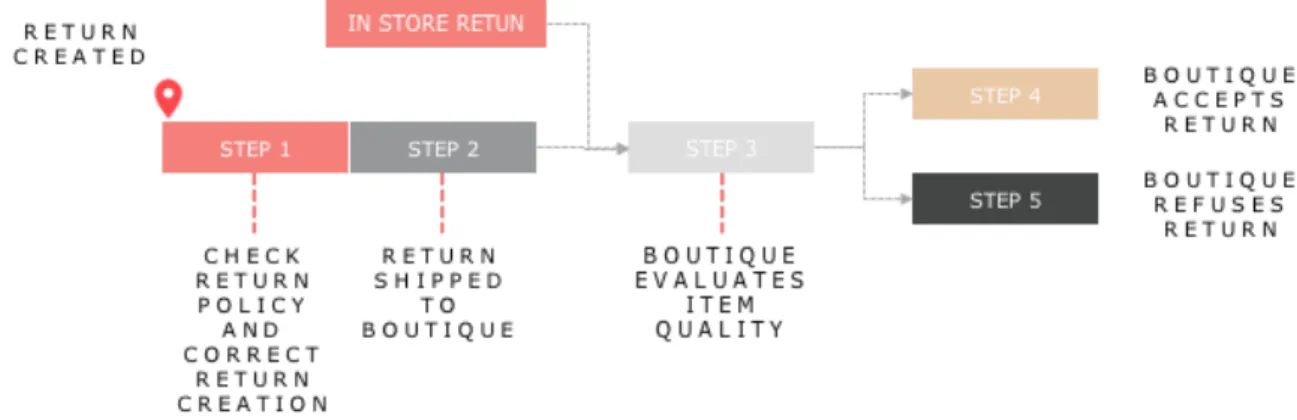

Figure 11 - Return Process Description ... 15

Figure 12 - Return Description Summary ... 16

Figure 13 - Average Charge Type Contribution per Shipment ... 17

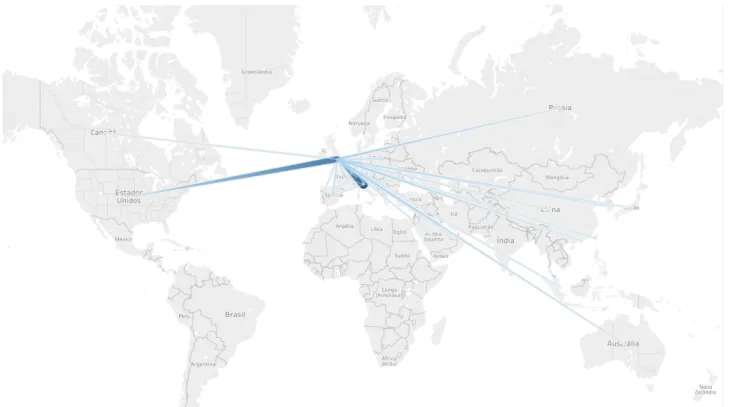

Figure 14 - Main Country to Country Outbound Order Flow ... 20

Figure 15 - Geographic Overview of Return Flow ... 21

Figure 16 - Return Policy Illustration ... 22

Figure 17 - Delivery Time Frequency per Service Type ... 24

Figure 18 - Proportion of Returns that are Contested by Boutiques ... 24

Figure 19 - Cumulative Frequency of Number of Days between SKU Return and Sale ... 26

Figure 20 - Distribution of Number of SKUs ... 26

Figure 21 - Return Delivery Time Frequencies - All Orders vs. Orders with Refund Related Ticket ... 27

Figure 22 - Intra EU Return Breakdown ... 28

Figure 23 - Frequencies of Intra EU Return Breakdown ... 28

Figure 24 - Via UK Return Breakdown ... 32

Figure 25 - Frequencies of Via UK Return Breakdown ... 33

Figure 26 - Time Considered for Via UK Rule ... 34

Figure 27 - Relation between Return Time until Norsk and % of Late Returns ... 34

Table 1 - Average Shipping Costs per Delivery Service Type ... 23

Table 2 - Average Times for Intra EU Returns Breakdown ... 28

Table 3 - Results of Intra EU Solution ... 30

Table 4 - Results of Intra EU Solution (with rule creation) ... 31

Table 5 - Average Times for Via UK Returns Breakdown ... 32

Table 6 - Results of Via UK Solution (with rule creation) ... 36

Table 7 - Results for Alternative Transhipment Country - Express Delivery Service and Transit Time ... 38

Table 8 - Results for Alternative Transhipment Country - Express and Standard Delivery Services and Transit Time ... 39

1 Introduction

“To define it rudely but not ineptly, engineering is the art of doing for 10 shillings what any fool can do for a pound”

– Arthur Wellesley, First Duke of Wellington

Despite not being an engineer, Arthur Wellesley’s peculiar view of engineering is not far from its role in modern-day businesses. Efficiency has never been so decisive in determining a company's fate in any given industry. With the increase in globalized trade, this is especially true in matters of Supply Chain Management and Logistics.

In the competitive global market, logistics plays an important role when striving to achieve advantage. The complex networks and frameworks of globalized trade rely heavily on logistic solutions to obtain raw materials and supply goods, services and information in the most effective ways. Often viewed as the means to deliver goods and services to the final consumer, logistics also provides the means for the reverse flow of items.

As it will be analysed later in this project, the return policy of fashion retailers plays a major role in determining customer repurchase and customer service level. This flow of returned items has a direct impact in the logistic frameworks of such companies and consequently on their cost structures. As such, the thorough analysis of the current state of item flow, as well as the study of solutions to further improve the return process is of crucial importance.

Return flow is often costlier than the forward distribution of goods, due its added complexity. Not only do returned items typically need to be shipped from location to location until they reach the return hub destination, they often require refurbishing or other activity in order to be resold. Adding to the cost of shipping and of processing returned items, retailers are unable to sell items during the processing time. This implies not being able to capitalize on a great number of assets for a considerable period of time and can lead to item depreciation. Furthermore, online fashion is the retailing sector that experiences most returned items, reaching in some cases 50% of total orders.

1.1 Farfetch

As one of the world’s most important industries, fashion plays a major role in the global economy. In 2016 the fashion industry is expected to reach 2.4 trillion dollars in total value (McKinsey&Company, 2017), meaning its weight would equal the seventh largest country if ranked alongside individual countries’ GDPs (International Monetary Fund, 2017). This colossal value becomes even more relevant when taking into consideration that 2016 was a slower year, marked by volatility and uncertainty. For 2017, the prospects look even better and every player looks at the potential market recovery as an opportunity for growth.

Farfetch is a fashion e-commerce platform that acts as a marketplace for curated fashion Boutiques and brands all over the world. Launched in 2008 by founder and CEO José Neves, Farfetch now connects over 500 Boutiques with customers from more than 190 different countries. Its momentum and increasing importance in the fashion industry have valued the company at almost 1.5 billion dollars in May of 2016, raising 110 million dollars in its Series E funding round and giving it the “unicorn” status in the start-up scene. The fast growth rate - 550% revenue growth between 2012 and 2015 - placed the company in the 224th position in the Financial Times FT1000 report (Stabe et al., 2017), where Europe’s companies are ranked by growth rate. In terms of dimension, Farfetch has certainly surpassed the start-up norm, with workforce reaching over 1000 employees and with offices in Porto, Guimarães, London, Los Angeles, New York, Tokyo, São Paulo, Hong Kong, Moscow, Shanghai and Lisbon.

Fashion Boutiques typically focus on offline trade, offering clients a carefully selected assortment of items and a personalized purchase experience. Farfetch brings these local and unique Boutiques together and combines their items into a single platform for worldwide availability. The exclusive customer experience is also replicated, as Farfetch tries to offer the best possible service to consumers. Acting as key partners for Farfetch, the Boutiques use the platform to offer the world’s best and most exclusive items to a worldwide audience, regardless of location. Farfetch rigorously selects Boutiques for partnership purposes, ensuring the compliance with the platform’s procedures and alignment with the company’s mission and values.

What distinguishes Farfetch from most of its etailer competition is its business model. Unlike most online fashion retailers, instead of purchasing items and selling them to the final consumer, Farfetch uses a drop shipping model. This means that goods are transported directly from Boutique to customer using third party logistics (3PL) partners, without ever being kept in stock. Farfetch therefore acts as an intermediary between Boutiques and consumers, holding no inventory. The inexistence of stock imposes challenges but also opportunities for Farfetch’s framework: it decreases the stock depth when compared to the competitors’ business models (meaning an increased risk of stockout due to the small number of SKUs), but allows for a broader assortment of clothing (a key competitive advantage over other fashion eTailers). This model eliminates the necessity of having high holding costs, nevertheless imposing great pressure and expectations on the logistic process. Farfetch must assure the smooth operation of a complex delivery network: where the pick-up locations are not directly managed or owned by Farfetch, and are spread all over the globe.

1.2 Project

Farfetch, as most fashion companies, highly values its customer base and wants to deliver the best possible service. As such, in an industry where pervasive uncertainty and change are at the root of its existence, Farfetch strives to rethink the fashion experience it offers. From investing in the internet of things (IoT) and in initiatives such as Store of the Future (Kansara, 2017), to trying to reach and overwhelm customer expectations, the need to excel is engraved in the company’s nature. In fact, one of the six values Farfetch so proudly promotes is called “Amaze Customers”.

Upon the introduction of this most recent company value, Farfetch’s return policy was reviewed. It was determined, in an attempt to “Amaze Customers”, that Farfetch would accept all returns, free of charge. Despite some obvious constraints regarding usage and item quality, customers are free to return items for whichever reason it may be. The Farfetch platform allows for a pickup to be booked, free of charge, and the item is returned to the Boutique in a seamless manner. As previously stated, the drop shipping model imposes significant logistic challenges for Farfetch. In regard to return processing, the same challenges are verified for the reverse supply chain, where the number of origins, destinations, carriers, customs regulations and variability of quality of returned items, all weigh in to form the complex framework that Farfetch uses.

This lenient approach to product returns, combined with the fast growth of the company has made returns a very cost intensive process. The rise in the number of orders in Farfetch’s history has been accompanied by a rise in the return rate, as shown in Figure 1. At present time, returns cost around £7M yearly. Furthermore, there is discussion as to the Initial Public Offering (IPO) of Farfetch (Team, 2017). In order to prepare for a stock market launch, companies usually look

(Young, 2014). Return costs amount to around £7M yearly, and as such, there is a lot to gain in cost savings.

This project aims to find and plan solutions for the cost reduction of returns. The proposed objective was to focus not on the number of returns, but on the cost per return. The return rate itself is a matter of study at Farfetch, developed by other departments, where elaborated size guides are created in order to decrease the number of returns. This project assumes that a return rate will always exist and should represent the least possible cost. The paper aims to offer a full view of the return framework and to devise solutions that decrease costs with the minimum negative impacts.

A return is essentially the reverse delivery of any given item. As such, the logistic management of returns is performed by the Delivery Team. In Farfetch, the Delivery Team is ramified into two different teams: Support and Development. The Delivery Support Team handles operational and daily issues such as the generation of manual airway bills, tracking of parcels etc. The Development team on the other hand focuses on more strategic solutions for the delivery framework. As such, this project was developed inside the Delivery Development Team and benefited greatly from other team members’ aid and knowledge.

1.3 Methodology

Despite the objective of the project being quite straightforward, reducing cost on such a complex and worldwide operation becomes a challenging task. In an attempt to breakdown the intricacy of the problem, a series of steps were followed.

1. Understand the ordering process. Fully analyse Farfetch’s modus operandi for order processing and grasp the entire scope of the business;

2. Understand the delivery outbound and reverse framework. Map the several types of returns, methods, carriers, service types used by Farfetch, defining the “as is” framework of returns. Measure, quantify and identify major return clusters;

3. Identify areas of opportunity. After the mapping of the current state of affairs, the major potential areas for cost saving were pinpointed. This allowed to identify the main return types to be broken down and studied;

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 0 50 K 100 K 150 K 200 K 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Year % of R et ur ns Nu m be r of O rd er s

Evolution of Total Number of Orders and Return Rate

Total Number of Orders % of Returns4. Estimate solution impacts. For any given proposed solution the impacts of such change had to be measured. The cost saving rationale was taken into consideration alongside other negative impacts that could arise from the proposed solutions;

5. Mitigate negative outcomes. Make changes in order to reduce negative effects from the proposed solutions while still maintaining relevant cost savings;

6. Re-estimate solution outcomes. Analyse and predict outcomes of proposed changes to the initial solutions.

The methodology used was very similar to the PDCA frequently used in continuous improvement. Despite the Deming Cycle, depicted in Figure 2, not being continually repeated, the methodology outline used was similar (Arveson, 1998).

1. Plan: Establish objectives necessary to deliver the proposed goals and objectives; 2. Do: Implement and execute the proposed plan;

3. Check: Study and assess the measurements in order to perform the next step with the best possible information;

4. Act: Decide on changes to improve the process.

1.4 Structure

The remainder of this dissertation is structured in order to offer the most complete scope of the return process as possible. Chapter 2 encompasses a literature review on the organizational perspective for managing reverse logistics and on the behavioural side of return policies. Chapter 3 focuses on showcasing the current state of processes at Farfetch. It provides insight on the order processing, aiming for a global understanding of the outbound item flow. As the focus of the report is on item returns, most of the following subchapters focus on matters inside the return scope. Return policy is described, along with the return process and return cost structure. A list of used carriers and delivery services is also presented. At the end of the chapter a geographical overview is provided so that the main flow of items is described. In Chapter 4 two main modifications are studied. These are the delivery service change for two major groups of returns, and the change of transhipment country. Chapter 5 concludes this dissertation reviewing the proposed changes and suggesting changes for future work to be developed.

2 State of the Art

In this chapter, some of the most relevant topics on reverse logistics, and the reason for the existence of this field of study will be discussed. It is intended to first introduce the notion of reverse logistics linking it to the important concept of returned products. Both the retailer and customer side will be approached through the analysis of different papers and previous work done on these matters.

2.1 Reverse Logistics

Reverse logistics involves planning, implementing, and controlling an efficient, cost effective flow of raw materials, in-process inventory, finished goods, and pertinent information from consumption to retrieval of the product value or proper disposal (Tibben-Lembke et al., 2002). This backward flow of material is usually viewed as being the opposite of forward logistics, however was proven not to be necessarily a symmetric view of forward distribution (Fleischmann, 1997). Earlier definitions of Reverse Logistics often refer to recycling and disposing of waste as the main activity of this concept (Stock, 1992), while later interpretations define the inbound flow more broadly, not specifying the main objective of this logistics field of study. In fact, the reasons for managing the reverse flow of material, or Reverse Supply Chain Management (RSCM) (Prahinski et al., 2006), depend essentially on the rationale behind the product return.

Products enter the scope of RL due to two main impetuses. The first is that customers return the products to the sale point (retailer, or other) because the product failed to function as desired or due to any reason the customer deems fit, as long as the return policy allows for it. These are usually denominated as consumer returns. Depending on the state of the returned item, it may immediately be placed for sale or sold on a secondary market as a refurbished or repaired item (Cheng et al., 2010). The second impetus is referent to products that are collected by retailers from customers for the purpose of recovery once they have reached their end of life (EOL) (Agrawal et al., 2015).

The reasons why products enter this reverse supply stream can be easily correlated to the drivers for the efficient management of RSC (Srivastava et al., 2006). Srivastava suggests that, alongside with fierce global competitiveness, there are three main drivers that lead brands and retailers to give such a heightened importance to this topic. The first is the economic driver. Due to the increasing number of returns in most sectors (Ram, 2016), the value that can be obtained from these items, either in secondary markets or even sold as scrap, amounts to considerable values in absolute terms (James Stock, 2002). Moreover, landfill and incineration capacities are diminishing, leading to the increased cost for these activities and to the necessity to explore alternatives (Martijn Thierry et al., 1995). The second reason stated by Srivastava deals with regulatory pressures. In fact, end-of-life take-back laws have brought an environmental responsibility to effectively manage end-of-life products (Fishbein, 1994). The last driver, but certainly not the least important, is due to the pressure the consumer imposes in the return process. Either with social and environmental motivations or because of demanding money-back policies, consumers certainly influence the entire return process.

Regarding the frameworks involved in terms of reverse logistics management, two main themes are studied in previous research: network optimization (Srivastava et al., 2006) and process management (Stock, 2009).

Despite depending on the type of industry and products retailers deal with, there are generic steps for reverse supply chain management.

Sourcing

Sourcing constitutes the first stage of the process, defined by the activity in which a firm gains the possession of the products. The collection location of the items is usually geographically spread, sometimes causing difficulties with sourcing (Bloemhof-Ruwaard et al., 1999). There are three main types of collection methods, that depend on where the collection occurs: via customers, via retailers or via third party logistics partners, depicted in Figure 3 (Kumar et al., 2008).

Inspection and Sorting

After collection, the returned items are normally brought to a single location where inspection occurs. In this stage, the item’s quality is assessed according to degree of use. The state of returned items may range from unused/unworn to being end-of-products. Due to the significant quality variability, it is essential to determine the state of the returned items. The correct inspection is a paramount step in the reverse logistics stage, as it leads to sorting the items in order to properly define their future use (de Brito et al., 2002). A pre-processing stage may occur, and is especially common when goods need to be refurbished, disassembled or repaired. Disposition

Finally, according to the latter stages, the returned products can be distributed according to their use (Srivastava et al., 2006). Depending on the quality of the items, different revenue streams, and therefore different destinations can be considered: returning to vendor, selling as new, repackaging and selling as new, selling via outlet, remanufacturing or refurbishing, selling to broker, donating to charity, recycling and disposing to a landfill (Martijn Thierry et al., 1995, Norek, 2003). Item flow according to destination is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 3 - Collection Methods in Kumar, Cradle to cradle: Reverse logistics strategies and opportunities across three industry sectors, 2008

In order to efficiently manage all of the stages involved in managing reverse logistics, many companies outsource these activities to third-party logistics partners that specialize in such services. Past studies have analysed whether or not the outsourcing decision is best, trying to understand what variables should influence the decision. These focus on two main areas: competences and barriers to entry. If there is no common ground between companies’ core competences and the RL activities, and thus the potential for gaining competitive advantages is low, then a firm should not consider outsourcing (Serrato et al., 2007, Wu et al., 2005, Arnold, 2000). Barriers to entry are common when considering any type of vertical integration. When referring to reverse supply chain management, barriers can include complex information systems, equipment, warehousing facilities among others (Ko et al., 2007, Govindan et al., 2012). These high overhead costs have to be balanced with profitable outcomes of return processing in case returns are to be managed in-house.

2.2 Return Policy

Returns policy is a very controversial issue among researchers, yet most point out that it is a critical aspect in the planning and implementation of supply chain and marketing strategies, with the relations between each shown in Figure 5. It is important to first understand the possible alternatives of a return policy. A store or retailer may decide to offer different levels of return that include: full return (unconditional, full money back policy), partial return (offering a percentage of the item’s value or store credit for future purchases) or no return (not accepting returns) (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2004). Restrictions can also be imposed by retailers in an attempt to control the quality of the returns they receive. These restrictions can include impositions on the state of the items, original packaging, time limits for returning items or others. These restrictions can indicate the measure of difficulty in returning products (Yu et al., 2008).

Figure 4 - Reverse Item Flow in Kumar, Cradle to cradle: Reverse logistics strategies and opportunities across three industry sectors, 2008

Figure 5 - Impacts of Return Policy in Klas Hjort, Return Policies on eFashion, 2016

The acceptance of consumer product returns is considered to be a necessary aspect of retailing and has proven to be an important marketing and strategic tool, able to considerably increase customer satisfaction and sales (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2004). In fact, there are substantial studies on the impact a return policy has on customer behaviour. Many point out that consumers view a loose return policy as a purchase motivator (Trager, 2000, Wood, 2001) and others describe how a tight policy can make for an aborted transaction (Cho, 2004). For online consumers, this factor can pose even a higher importance. Firstly, when buying online there isn’t the ability to physically view the product before purchase. Secondly, the number of alternative sellers is very high, leaving consumers facing a high number of possible retailers. Customers tend to avoid risk, showing preferences for retailers that are more familiar than unknown (Bornstein, 1987). When facing a number of possibilities or when the uncertainty about a product is high, consumers tend to engage in excessive information search (Dowling et

al., 1994). Having a loose return policy can therefore prove to be a competitive advantage, as

Wood (2001) showed that it can reduce the consumer product search time and increase the pre-purchase expectations of product quality. Despite being a potential demand booster, lenient return policies also increase the return rate, where in the case of e-commerce retailers it is estimated to reach as much as 35% (Gentry, 1999, Ram, 2016).

Regardless of customers preferring a lenient policy, these are costly to operate and vulnerable to consumer abuse. Despite the number of returns increasing due to “free return” policies, the net profit per consumer is said to increase in a number of studies (Petersen et al., 2010, Wang, 2009). In fact, there are other variables that were found to increase the return rate. Impulse buying is a sales strategy used by many retailers in order to persuade consumers to buy goods or services that they were not planning on buying. In the e-commerce sphere, such impulse is usually prompted by sales or free delivery promotions. When free delivery is offered to consumers, there is a tendency to order more items, however there is an increase in return rate (Lantz et al., 2013). Unlike most studies that use a study group as a sample, Lantz and Hjort preformed a study on real consumers of an e-commerce platform. The website in question is the Nordic nelly.com, that focuses on fashion and beauty, further increasing the relevance of their findings on the present paper.

Indeed, there are studies that focus not only on the topic of product returns, but also on the e-fashion retail. Due to the increase in product returns given by a lenient return policy, there is some discussion as to the profitability of offering such a loose policy. Profitability aside, there are certain products and online industries that strive for a long-lasting healthy relation with customers. Fashion eTailers usually apply to this rule, and are happy to charge a premium for offering a loose return policy (Yan, 2009). This is especially the case when dealing with luxury products. Uché Okonkwo (2009) is commonly cited on the topic of online sale of luxury products. This author clearly proposes that luxury items are completely distinct from goods of regular consumption. Luxury provides a very special relation between item and consumer. These products often enter the realm of art and craftsmanship and thus their differentiating role in the society we live in. This distinction of supreme quality and exclusivity that these products offer should therefore be matched by the overall service and purchasing experience. In a customer segment perspective, luxury is amongst the most exquisite, and for the return policy to be constructed similarly, it should be loose and hassle free (Hjort et al., 2016). In fact, for a healthy and prolonged relation between retailers and customers to prosper, and for new customers to be converted into recurring ones, the relation between both parties must be based on trust (Ramanathan, 2011). The relation between trust and frequency of purchase is shown in Figure 6.

3 Description of Current Situation

3.1 Ordering Process at FarfetchIn order to understand the return process at Farfetch, it is relevant to first understand how orders are dealt with. This is of particular importance to the company in the sense that the whole company revolves around the 6 steps that founder and CEO José Neves devised in the first stages of the company, so that orders would be fulfilled efficiently. This breakdown is not only important for organizational purposes but also to streamline efficiency through the measurement and control of each step, while acting as cornerstones for the operational departments’ responsibilities. The span of action of each team will be presented afterwards. For the flow of processes to be triggered, an order must be placed by the customer. When the checkout is completed by the user, the shopping cart in question (with one or more items) is assigned a Portal Order Number. This identification defines the basket of goods contained in a given order. Ordered items often belong to different Boutiques, and therefore a Portal Order is then broken down to one or more Boutique Orders. A Boutique Order thus includes solely items of a particular Boutique from a given order. Figure 7 aids the understanding of this order segmentation.

The stages of order processing are as depicted in Figure 8, following the description of each step.

Figure 7 - Division of Portal Orders into Boutique Orders

Step 1 - Check Stock

This is the first stage of the order process, where Boutiques are responsible for checking the existence of stock for the items ordered by the Farfetch customer. In case there is no available SKU for that order, it is immediately cancelled and the customer is informed of the “No Stock” occurrence.

Step 2 - Approve Payment

As with the first step, the payment approval is also triggered upon the customer checkout. This stage evaluates the legitimacy of the payment, approving the order if the customer is deemed genuine or cancelling it in case of fraudulent activity. There are cases in which this step is performed autonomously with the use of black and whitelists according to customer history, where orders are cancelled or approved automatically.

Step 3 - Decide Packaging

After the two previous stages being completed successfully, the item’s packaging must be decided. Farfetch’s order management software suggests a box size depending on the item category, however, the Boutique has the freedom to choose whichever size suits the given items best. All the documentation necessary for the parcel shipment must also be printed in order for this stage to be completed.

Step 4 - Create Shipping Label

In this step the air waybill (AWB) for parcel dispatch is created. The generation of the AWB is normally automatic, however due to mistakes when filling out shipment forms, or due to postal code mismatch, some parcels need to have their information corrected and the AWB is generated manually by the Delivery Support Team.

Step 5 - Send Parcel

When the items are ready for collection they are flagged for pickup. Boutiques with high throughput rates are assigned a daily pickup, however, if this is not the case a pickup request is booked by Farfetch.

Step 6 - In Transit

Upon parcel scanning by the courier, package is considered “in transit” and the customer is given the tracking number in order to monitor the parcel’s journey. The delivery teams also track the parcel in order to tackle issues that might occur during this stage.

As previously stated, these steps Farfetch uses for order control can also be used to delimit the span of action of teams, shown in Figure 9.

The delivery department is divided into two different clusters: Delivery Support and Delivery Development. The Delivery Support team handles day-to-day issues, managing and resolving tickets that have to do with shipping issues. These can range from creating manual returns to tracking parcels or dealing with unexpected issues with custom authorities. This daily maintenance of the delivery flow (forward and reverse) is essential in order to keep the delivery service as smooth and as efficient as possible. The Delivery Development team’s main objective is to draft and execute projects that mitigate problems that can arise. Also it is this team that explores other markets and analyses solutions for cost saving in the shipping of items.

3.2 Returns Overview

Returns are often a part of any eCommerce platform. Due to the business model that Farfetch uses, the control over items and processes is performed differently as if Farfetch owned its own inventory. Notwithstanding, the framework for return handling matches the complexity needed for such control. In order to fully understand the scope of the returns in Farfetch, the distinction between the two types of returns must be made: RTOs (“Return to Origin”) and Returns by Users.

3.2.1 RTO - “Return to Origin”

RTO stands for “Return to Origin”, and is defined by the cancelation of shipping, and therefore the request for return, happening before the item reaches the customer. For an RTO to be initiated, a post-order reason must be triggered. After the respective delivery provider is informed, the package is identified and tagged in order for the delivery not to be completed and for it to be dispatched to its origin location. There are times however, where the RTO is triggered too close to delivery and the lag between the trigger and the parcel identification is

The reasons for the cancellation of the order delivery are the following: Customer Request

These types of RTOs occur when the customer contacts the Customer Services in order to cancel the order while the parcel is still in transit. The Customer Services inform the Delivery Team of this situation and the order is tracked and cancelled.

RTO by Fraud

These situations exist when the Fraud team approves the payment of a given order wrongfully. In these circumstances a customer was thought to be legitimate and fraudulency is detected while the parcel is transit.

RTO by Boutique

The Boutiques, due to human error or other might send the wrong item size or colour, only realizing this after the order has been shipped. Boutiques contact Partner Services who in turn inform the Delivery team of the occurrence.

In any case, a delivery performed after a RTO is issued, is a situation that should be avoided. In case of customer request, it might raise doubts about the efficiency of delivery processes; if the cancellation was ordered by a Boutique it might leave customers with a flawed image of both Farfetch and the Boutique; if the reason for the RTO was fraud then this implies the total loss of the item value and the probable refund of the customer that was victim of fraud.

RTOs consist of a very specific type of return due to the reasons why they are issued. Despite there being room for improvement in terms of RTO rate, this return type is of a much smaller number when compared to returns created by users.

3.2.2 Returned by User

As opposed to returns by RTO, these returns are characterised by being created by the customer - meaning that the parcel did in fact reach its final destination in terms of the outbound order perspective. These types of returns account for the majority of returns when comparing with RTOs. Returned orders by users represent around 20% of total orders. The return rate is not exceptionally high, especially when compared to other online merchants. However, it does consist of a considerable amount, particularly when taking into account the company’s order growth rate. The rate of returns is a challenge in itself and is being tackled by other teams and departments inside Farfetch. This dissertation attempts not to approach the return rate but to optimise the framework for existing and future returns.

Customers may return products without necessarily having a reason to do so. Nonetheless, users are prompted to leave a reason upon return creation. The distribution of these reasons is detailed in the Figure 10.

As it is easily observed, the main reason for item return is due to sizing issues. This is commonly the issue generating most returned items (Reid et al., 2016). The majority of products being wearable, it is often hard to achieve the perfect fit with an online purchase. Elaborate sizing guides help the choice of the most indicated size, however this issue will always pose a challenge when selling clothes online compared to brick-and-mortar retail.

Due to the fact that RTOs will not be a matter of study in this paper, and their introduction was merely to expose the different types of returning items, “Returns by User” will be referred to solely as “returns” in an attempt to simplify future analysis.

3.3 Return Policy

3.3.1 Customer Responsibility

Farfetch, as do many fashion e-commerce platforms, offer free returns. This means that customers may return items free of charge, regardless of the reason for return. The majority of orders are shipped with a return AWB enclosed, alongside all of the billing documents and return procedure. Farfetch allows for a simple process to be followed in order for customers to arrange for item pickup for return. Despite this flexible approach by Farfetch, there is a return policy and procedure that customers must respect to ensure that this process is concluded smoothly.

In order to create a return, a customer must follow the following steps as per indicated in the return instructions sheet:

1. Go to the Farfetch website, logging into their personal account and accessing the “My Orders & Returns” page;

2. Selecting the return “by courier” option;

3. Confirming the address and choosing a convenient time for collection;

4. Preparing the package for return, implying that the return label and a signed return invoice are attached to the outside of the Farfetch box and that the item(s) are placed in the inside, with all of the original packaging. The box should be left open for the courier to check its’ contents.

67% 22% 5% 3%3%

Reasons for Returns by User

Sizing Issues No Given Reason Quality Issues Wrong Item Sent Item Not as Describedunworn and undamaged, and in case of beauty, hosiery or lingerie, unused and in unopened packaging where applicable.

In case the customer and the Boutique from which the item was purchased are located in the same city, Farfetch also offers the possibility of returning “in-store”. In this case the customer transports the item to its destination directly. This happens mostly in Italy, where the majority of Boutiques are located.

It is of crucial importance that Farfetch suggests that returned items are within acceptable Standards of quality. In case a Boutique receives a returned item that does not comply with these Standards, it might want to contest the return all together. Due to the partnership quality of the relation between Farfetch and the Boutiques, the negotiation of “refused returns” (denomination given to returns that Boutiques do not consider to have the necessary quality requirements and which return is contested) is fundamental. Negotiation attempts are made by Partner Services where, if the damage does not compromise the sale of the item entirely, Farfetch is made responsible for the eventual discount of the product, covering for part of the item’s value. In case the item is stained and an attempt to repair the item is made, the cost of doing so is also Farfetch’s responsibility. In some cases, the item is not appropriate for sale and in this case Farfetch must assume the purchase of the article.

3.3.2 Farfetch Responsibility

Customers are not the only party that must comply with a certain return policy. Farfetch also agrees with the Boutiques that, in case of a return, it should arrive no later than 28 days upon the item’s arrival at the customer’s location. Articles that arrive beyond this period are considered Late Returns and can be legitimately contested by Boutiques.

3.4 Return Process

As happens with order processing, returned items also follow an internal procedure to guarantee control over all the steps. Analogously, the stages of returns depend on several triggers. The process overview is depicted in Figure 11.

Step 1 – Review Return

This step assures that the customer return policy was respected and that the return was created correctly and successfully.

Step 2 – Return Transportation

The return is shipped to the Boutique location. Step 2.1 – Return in Store

When customers live in the same area as the Boutique the item originates from, the user can deliver the item directly to the store, eliminating the need for item transportation.

Step 3 – Return Verification

The Boutique evaluates the state of the item and checks for usage and damage signs and if all the security tags are still attached to the item in proper condition.

Step 4 – Return Accepted

If all the necessary conditions are met, the Boutique accepts the return. Returned items are automatically accepted if the Boutique does not raise any complaints in regard to the item’s quality in two days of the return’s arrival.

Step 5 – Return Refused

In case the Boutique finds that it does not wish to accept the return, because it did not meet the minimum quality requirements, the return is contested. When this happens, the item is sent to the Farfetch office in Lionesa, Porto - Portugal, assuming the purchase of the item and the shipping cost involved.

In order to describe the framework for return processing, a summary of procedure flow is shown in Figure 12.

3.5 Cost Structure 3.5.1 Costs

The cost of any return can be broken down into different types of charges. Essentially, return costs can be separated into 4 main categories:

Shipping Cost: associated with the actual cost of moving merchandise, varying with origin and destination zones and with parcel weight and/or volume. Sometimes referred to as AWB cost. Duties: tax levied on imports by a given country’s customs authority. This cost depends on the country, value of good, type of good, and other factors depending on custom authority. The rate of duty imposed on the type of good normally depends on the Harmonised System (HS) of product classification, developed by the World Customs Organisation (WCO).

Tax: in addition to the duties charged on imports, each country may or may not charge Value Added Tax (or equivalent).

Other charges: couriers may charge additional fees (usually denominated as “surcharges”) for additional fuel, unusually demanding parcel handling, delivery to remote destinations, etc. The contribution of the aforementioned charges is represented by Figure 13.

Return shipping charges are the focus of this work and represent an annual cost of around £7M.

3.5.2 Revenue

Due to the luxury status of Farfetch’s items and of its customer base, the company strives to offer the best possible service level to its customers. In order to assure this, one of the many initiatives for this purpose was designed by the Supply department and is denominated as “Service 3.0”. This project establishes an agreement between Boutique partners and Farfetch and comprises of a monthly payment of 1,5% of the Actual Transaction Value (ATV) of each Boutique to Farfetch.

The ATV is a common metric in the eCommerce sector, used to measure the inflow of revenue. It is calculated by considering the sales minus “No Stock” occurrences, cancellations and refused payments. 57% 40% 3%

Average Charge Type Contribution per Shipment

Shipping Charges Duties and Tax (D&T) Other ChargesIn order to understand the conditions that arise from this initiative, the concept of “No Stock” (NS), introduced in Chapter 3.1 must be further explained. A NS occurs when a customer places an order and the Boutique informs Farfetch that it does not possess the item in its stock. The platform tries to source the item from another Boutique therefore minimizing the problem. However, there are cases where the item does not exist elsewhere and the user must be informed of the item’s unavailability. This creates a bad customer experience, damaging Farfetch’s reputation, and driving the need to minimize these cases. A monthly report is created with each Boutique’s performance regarding the monthly number of “No Stocks” it generates.

In an attempt to minimize these cases, the Supply department created thresholds that define objectives for the Boutique’s efficiency in sending items and updating stock on Farfetch’s platform. Boutiques are exempt of the payment of 1,5% of their ATV if they are able to keep their “No Stock” levels below or equal to 0.75%.

Despite the calculation of this value not being directly correlated with the product returns, this revenue source contributes to compensate the value spend by Farfetch on returned items. 3.6 Carriers and Shipping Services

The carriers used on a returned order are, by general rule, the same carriers used in the outbound sending of the parcel. Thus, to understand the delivery scheme of the reverse item flow, it is important to firstly understand the outbound delivery methods and providers. Farfetch works with several carriers but their availability to deliver orders depends on the country of origin and the country of destination of the items.

Farfetch works mostly with DHL and UPS, and together they constitute around 97% of the total shipments. The remaining are shipped using a number of different carriers, and are used due to two main situations:

• Specific Domestic orders: when the Boutique and customer are in the same country, and there is a local, specialized carrier for the country that operates better than other carriers. This is the case for domestic orders in Brazil, Japan, Singapore, Taiwan;

• Special services: when the delivery service is more exclusive regarding to the time of delivery (services that are neither Express nor Standard). This is mainly used for VIP customers.

Each carrier can offer different services for parcel delivery. They differ from each other in terms of delivery time and in terms of cost of delivery. Although shipping prices vary depending on the carrier used, delivery times depend mostly on the service used:

• 90 MD: delivery in 90 minutes from order placing; • Same day: delivery in the same day the order is placed;

• Next day: delivery in the day following the day the ordered was placed; • Express for most of Europe and USA: delivery within 2-4 days;

• Express for Rest of the World: delivery within 3-7 days; • Standard: delivery within 5-7 days.

Although there is quite a wide range of services for order delivery, returned items use an Express delivery service as default. In general terms, the carrier used for the return route is the same used in the sending of the item.

3.7 Return Transhipment

Duties and Taxes (D&T) costs that occur in cross-border parcel sending can be extremely cost demanding, and in an effort to minimize these types of costs, Farfetch has introduced a transhipment point for some return routes.

The European Union constitutes a customs union, where goods are freely traded among members and where a common customs policy is used for goods imported from non-member countries. Despite this normalization of duty costs, the same does not happen with Value Added Tax (VAT), varying amongst EU member states. Moreover, the common customs union rules may not apply in terms of returned items. Some countries opt by considering returned items as being imported goods and therefore tax them as new parcels entering the country.

The United Kingdom processes returned parcels as “exports returning to origin”, and therefore does not levy import D&T for these items. Furthermore, the main DHL account that Farfetch uses is based in the UK and issues relating to the UK’s customs are solved with a fair degree of ease. This led Farfetch to use the UK as a transhipment point for some countries inside the EU. Thus, for a specific list of countries (and Boutiques) that agree to this transhipment method, returned items from outside the EU first enter the UK before reaching their final destination, avoiding excess D&T costs.

Farfetch uses a transhipment partner – Norsk – in the United Kingdom that receives returned parcels, processes them and dispatches them to Boutique’s locations. This interruption in the return delivery process generated the need to define the first shipment (from customer country to the UK) as “1st leg” and the second shipment (from the UK to the Boutique country) as “2nd leg”. For orders that are included in this origin/destination set, the AWB that is printed upon return creation has its destination as the transhipper’s address. Norsk receives the parcels, scans them and prints the AWB for the 2nd leg using a tool developed by Farfetch, this tool is integrated with the sales management platform used internally.

These returns are referred to as “Via UK” and apply to returns from outside the EU to the following countries: Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Portugal and Spain.

Returns that do not apply to this transhipment method are denominated as “Direct” as they are delivered directly from customer to Boutique country.

3.8 Geographic Analysis

The purpose of this dissertation is to analyse and study logistics solutions for the return framework. Logistic operations depend greatly on the location of the items to be handled, thus, in order to understand the flow of products, a geographic analysis becomes useful to understand the main suppliers and customers of the Farfetch marketplace platform.

In order to better understand the overall location of outbound supply and demand, Figure 14 was constructed. This figure exhibits origins and destinations for a total number of orders above 3000 in the year of 2016.

The Boutique concentration is high in the European Union, accounting for almost 90% of total orders. Italy leads the list, being responsible for supplying 50% of orders globally. This European Boutique density explains the importance and interest of using a transhipping location such as the United Kingdom for D&T reduction.

Consumer distribution is much more disperse than of Boutiques. In terms of customers, the United States is the country where most items are sent to, accounting for around 28% of the total number of orders. The United Kingdom and Australia are the two following countries with more outbound flow, representing around 7 to 8% of total orders each.

For the returned products’ geographic flow, shown in Figure 15, it was expectable that items would flow from the major customer locations to the major Boutique locations. The major return routes are depicted below, and as was expected, they come from the main customer countries. What can also be concluded is that a great majority of returns use the United Kingdom as transhipment location – due to the largest share of customers being located outside of the European Union.

4 Proposed Solutions

Based on the previous analysis, two major lines of action to improve return process were developed: the delivery service change and alternative transhipment countries. Both solutions aim to reduce the cost of returned parcels.

4.1 Delivery Service Change 4.1.1 Solution Overview

As previously explained in this dissertation, the delivery services that carriers offer differ mainly in terms of time and cost of delivery. The faster the delivery service, the more expensive the delivery charge. At present time, all of the returns are associated to an Express AWB. This faster service is used in order to ensure that returned items arrive at Boutiques inside the return period. However, due to the significant difference between Express and Standard delivery costs, and given the volume in terms of number of returned items, a change in delivery service type presented itself as a plausible area of opportunity.

Ultimately, this change would imply differences in terms of time, cost, implementation requirements and other negative externalities that could eventually arise. Before considering the impact that this change could have on the cost structure of returned items or even the implementation requirements necessary for such change, a thorough analysis of return delivery times had to be performed.

Return Times

At the root of this consideration was the slack time existent due to the difference between the time that the customer has to create a return and the maximum return time that Farfetch assures the Boutiques. To recall both Farfetch’s and Customer’s compromise to return policies, the return deadlines are illustrated in Figure 16.

What this time overview indicates is that, if a customer submits a return request on the return policy deadline, Farfetch has 14 days to ensure the return’s arrival at the Boutique. This period seemed, in an initial phase, enough to perform the delivery for at least some select routes.

4.1.2 Express vs Standard Delivery

Cost

As a result of Farfetch’s large order volume, the company has a quasi-partnership relation with delivery service providers and therefore there is constant information flow and negotiation of price rates. At the end of each agreement in terms of prices, price rate sheets are sent to and validated by the Delivery Team in order to predict future shipping costs. These price rates vary in format and in calculation method depending on the provider. However, prices depend essentially on origin, destination, weight and volume of the parcel. Carriers use a formula that calculates what is denominated as volumetric weight. The formula used by DHL as follows:

𝐷𝐻𝐿 𝑉𝑜𝑙𝑢𝑚𝑒𝑡𝑟𝑖𝑐 𝑊𝑒𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑡 = 345678 9: × <=>78 9: × 84=687 [9:]ABBB

The cost of a shipment can be affected by the amount of space that it occupies rather than the actual weight. Thus, carriers measure both the weight and volumetric weight of parcels and use the highest value of the two in order to calculate shipment costs.

In order to illustrate the cost differences between services, a weighted average taking into account route occurrence was used, presented in Table 1.

Table 1 - Average Shipping Costs per Delivery Service Type Avg. Express Shipping Cost £14

Avg. Standard Shipping Cost £10.55 -25%

Speed

The cost difference of using these two different services was a straight forward analysis. In spite of the possibility of some variation of surcharges and differences between predicted price rates and actual costs, the price of a given shipment can be estimated with a fair degree of accuracy. Despite carriers suggesting the predicted time for given types of routes, delivery time in not ensured. As such, an analysis of delivery times was performed in order to understand, based on Farfetch’s history of returns, the difference between Express and Standard delivery times.

Express deliveries are in general performed by air transportation. By contrast, Standard services, sometimes referred to as “ground” services, are done by road transportation. Consequently, and by general rule, when an origin and destination are geographically separated by an ocean, thus making the ground transportation impossible, the only available service is Express. It is relevenat to note that, this is not the case with shippings between the United Kingdom and the European continent, as the Standard shipping is made possible using the Channel Tunnel.

The total return time difference between Express and Standard delivery services is stated to be around 2 days by the shipping providers. In order to further understand this variation, a box plot was used, shown in Figure 17. Taking into consideration all of the orders in the Farfetch history, the box plot allows to understand the frequency difference between these two types of service.

As was expected, the Standard service spans over a wider range of time. The median and average time differences are less than the 2 days suggested by carriers. However, in order to assure a safer consideration for future analytical purposes a Standard delivery will be assumed to take 3 days longer than an Express delivery.

4.1.3 Implications

The solutions proposed have impact on two major dimensions: cost and time. The cost impact is of easy interpretation as a Standard service will imply a lower cost for returned items and its quantification is relatively straightforward. However, due to the increase in lead time, it was necessary to understand the effects it could have on Fafetch’s business.

Late Return

Any return that is delayed due to the slower delivery service but still arrives at the Boutique inside the return period (28 days upon arrival at the customer), is considered to have an impact on the return service level. However, when returns are delivered outside of the return period, issues of grater proportions can arise.

In an attempt to measure the costs that derive from such situations, it became necessary to expose the process that is triggered from Late Returns. When a return arrives late, Boutiques usually contest the process all together, thus generating a ticket in Farfetch’s Customer Services. This ticket management system is what allows internal teams to work together and interact with Boutiques in order to solve individual problems.

Returned items are usually contested for arriving damaged, stained, not having all the security tags, etc. From all of the contested returns in 2016, a small portion of 9% were due to Late Returns. This comprises of 3384 returns all together. When a contest occurs, the Partner Services department is informed and attempts the negotiation for the return’s acceptance. There are cases in which the customer exceeds the return policy deadline and duly informs Customer Services of the situation. In these cases, the Boutique is informed beforehand, leading to the easier resolution of the contest for Late Return.

In any case, from the 3384 contests for Late Returns recorded in 2016, 96% were later accepted by the Boutique by means of negotiation with Partner Services.

This process and the proportion of returns that go through each path is shown in the Figure 18. Figure 17 - Delivery Time Frequency per Service Type

Despite the high rate of acceptance of Late Returns by Boutiques, there are cases when Boutiques are decided not to accept the Late Return. In these situations, where after an attempt at negotiating the return’s acceptance a Boutique still refuses an item, Farfetch must assume the item’s purchase. In these circumstances, items are sent to Farfetch’s office in Lionesa, Porto - Portugal. Upon arrival, the Supply department processes items, reintroducing them in the Farfetch platform, making it once again available for sale. Due to the intrinsic seasonality of fashion articles, and especially in case of off-season items, the depreciation suffered during this period can be of considerable cost.

The cost of Late Returns can therefore be broken down into 3 different fragments: • Cost of labour derived from ticket management and issue negotiation;

• Cost of shipping the item from the Boutique to the Farfetch office (in case it is not possible to negotiate the item’s acceptance);

• Loss due to devaluation of item’s sale (or total loss of item value in case the sale is not concluded).

Despite being possible to estimate the cost of a Late Return according to the direct mathematical implications, the impacts can reach deeper consequences. Farfetch’s exceptional partnership relation with the Boutiques is one of the pillars of its success. Increasing the number of contests due to Late Returns is essentially increasing the number of complaints partners have on one of the services Farfetch provides. The decrease in service level on the Boutique’s perspective is hard to quantify, therefore, in an attempt to minimize the negative impact on reputation, the number of Late Returns shall be minimized as much as possible.

Increase in Lead Time

Despite the attempt of keeping the number of Late Returns to a minimum, the proposed solution of changing the delivery service type implies the increase of an average of 3 days in the return delivery. This additional lead time could have effects in two different dimensions that will be introduced separately: Sales and Customer perspectives.

Sales Perspective

Returned items are processed and reintroduced in the Farfetch platform after being evaluated for item quality. If a return is to be delivered 3 days later, this means that the item will ultimately be reintroduced with the same lead time increase. This could lead to a failure to meet demand and could therefore imply lost sales.

In order to perform this analysis, it became necessary to study the sales behaviour of returned items. Thus, the time span from return reintroduction to item sale was evaluated. Items were organized by Stock Keeping Unit (SKU), defined by Product ID, colour and size. It was calculated that from all items that are returned, 74% have a posterior sale.

The frequency of the number of days between a return and a sale of a given SKU (from those that actually posteriorly sold) is given in Figure 19.

Cumulatively, out of the 74% of SKUs that are returned and later sold on the Farfetch platform, around 10% are sold 3 days after return reintroduction.

A sale is considered lost if there is a supply shortage. In other words, if only one SKU exists in Farfetch’s platform. The frequency of number of available SKUs was plotted in Figure 20, in order to estimate what would be the portion of items that would be in risk of such a situation.

As was formerly mentioned, Farfetch’s business model enhances stock breadth rather than depth. A very high concentration of items consists of single SKUs, making it impossible to source items elsewhere. Hence, vulnerability due to lead time increase is assumed to be focused on this set of items, that total 66%.

The degree to which these sales can be considered as totally lost is debatable. In fact, it is not possible to state that in case of impossibility of sale during this time window, the sale would not be converted after a later reintroduction. It is however relevant to state that, in case the reintroduction delay was to affect sales, it would only affect a relatively small amount of returns.

Customer Perspective

As described earlier in this paper, Farfetch offers a full money back policy when it comes to returns. Upon return arrival at the corresponding boutique and after the quality evaluation has

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Fr eq ue nc y Days Cumulative Frequency of Number of Days between SKU Return and Sale 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Fr eq ue nc y (% ) Number of Available SKUs Frequency Distribution of Number of Available SKUs

Figure 19 - Cumulative Frequency of Number of Days between SKU Return and Sale

for problem resolution. Adding to the undesirability of customer contacts for negative reasons, ticket management incurs a labour cost for the company.

In order to obtain a brief understanding on whether or not return delivery time has an impact on ticket generation. The return delivery time of orders that have an associated refund ticket was plotted, alongside the return delivery times of all orders, depicted in Figure 21.

Both distributions present a similar shape, suggesting that returns that generate a ticket are not necessarily delivered over a longer period of time. This overview indicates that there is a possibility that the number of tickets will not be affected by lead time.

4.1.4 Returns Intra EU

Returns that occur inside the European Union account for about 20% of the total return costs. It is important to note that given the scale and the extensive number of returns that Farfetch deals with, it represents a considerable absolute value. Furthermore, it is reasonable to acknowledge that due to the relatively small distance span and due to the inexistence of custom processing times, these types of returns could impose a minor disruption in terms of return times.

Return Time Breakdown

The total return time represents the full amount of time it takes for a return to be completed. This means that it takes into account the moment from return creation (by the user) to the moment of return delivery at the respective Boutique.

There are however, different phases of the return itself and the total time can therefore be broken down according to different triggers, depicted in Figure 22.

0% 2% 4% 6% 8% 10% 12% 14% 16% 18% 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Fr qu en cy (% ) Return Delivery Time (days) Return Delivery Time Frequencies - All Orders vs. Orders with Refund Related Ticket Orders with Refund Related Tickets All Orders