www.jbp.org.br

ISSN 1806-3713

Volume 44, Number 5 September | October 2018

HIGHLIGHT

V

olume 44, Number 5

Sept

ember | Oct

ober

20

18

Pulmonary

microbiome

Global TB Network

Patterns of electronic

www.jornaldepneumologia.com.br

FATOR

DE

IMPACTO

1.532

ISSN 1806-3713

Published once every two months J Bras Pneumol. v.44, number 5, p. 341-442 September/October 2018

Publicação Indexada em: Latindex, LILACS, Scielo Brazil, Scopus, Index Copernicus, ISI Web of Knowledge, MEDLINE e PubMed Central (PMC)

Disponível eletronicamente nas versões português e inglês: www.jornaldepneumologia.com.br e www.scielo.br/jbpneu

Associação Brasileira de Editores Científicos

I N T E R N A T I O N A L

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Rogerio Souza - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP DEPUTY EDITOR

Bruno Guedes Baldi - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP EXECUTIVE EDITORS

Caio Júlio Cesar dos Santos Fernandes - Universidade de São Paulo - São Paulo - SP

Carlos Roberto Ribeiro de Carvalho - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Carlos Viana Poyares Jardim - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Afrânio Lineu Kritski - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, RJ

Andre Luis Pereira de Albuquerque - Universidade de São Paulo - São Paulo - SP

Bruno Hochhegger - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul - Porto Alegre – RS

Edson Marchiori - Universidade Federal Fluminense, Niterói - RJ

Fernanda Carvalho de Queiroz Mello - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro - Rio de Janeiro - RJ

Frederico Leon Arrabal Fernandes - Universidade de São Paulo - São Paulo - SP

Giovanni Battista Migliori - Director WHO Collaborating Centre for TB and Lung Diseases, Fondazione S. Maugeri, Care and Research Institute, Tradate - Italy

Giovanni Sotgiu - University of Sassari, Sassari - Italy

Irma de Godoy - Universidade Estadual Paulista, Botucatu - SP

Marcelo Alcântara Holanda - Universidade Federal do Ceará - Fortaleza - CE

Pedro Caruso - Universidade de São Paulo - São Paulo - SP

Pedro Rodrigues Genta - Universidade de São Paulo - São Paulo - SP

Renato Tetelbom Stein - Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre - RS

Ricardo de Amorim Corrêa - Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais - Belo Horizonte - MG

Ricardo Mingarini Terra - Universidade de São Paulo - São Paulo - SP

Simone Dal Corso - Universidade Nove de Julho - São Paulo – SP

Tomás Pulido - Instituto Nacional de Cardiología Ignacio Chávez - México

Ubiratan de Paula Santos - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Veronica Amado - Universidade de Brasília, Brasília - DF EDITORIAL COUNCIL

Alberto Cukier - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo – SP

Álvaro A. Cruz - Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, BA

Ana C. Krieger - Weill Cornell Medical College - New York – USA

Ana Luiza Godoy Fernandes - Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Antonio Segorbe Luis - Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra - Portugal

Ascedio Jose Rodrigues - Universidade de São Paulo - São Paulo - SP

Brent Winston - University of Calgary, Calgary - Canada

Carlos Alberto de Assis Viegas - Universidade de Brasília, Brasília - DF

Carlos Alberto de Castro Pereira - Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Carlos M. Luna - Hospital de Clinicas, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires - Argentina

Carmen Silvia Valente Barbas - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Celso Ricardo Fernandes de Carvalho - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Dany Jasinowodolinski - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Denis Martinez - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre - RS

Douglas Bradley - University of Toronto, Toronto, ON - Canadá

Emílio Pizzichini - Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis - SC

Fábio Biscegli Jatene - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Frank McCormack - University of Cincinnati School of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH - USA

Geraldo Lorenzi Filho - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Gilberto de Castro Junior - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Gustavo Javier Rodrigo - Hospital Central de las Fuerzas Armadas, Montevidéu – Uruguay

Ilma Aparecida Paschoal - Universidade de Campinas, Campinas - SP

C. Isabela Silva Müller - Vancouver General Hospital, Vancouver, BC - Canadá

J. Randall Curtis - University of Washington, Seattle, Wa - USA

John J. Godleski - Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA - USA

José Alberto Neder - Queen’s University - Ontario, Canada

José Antonio Baddini Martinez - Universidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto - SP

José Dirceu Ribeiro - Universidade de Campinas, Campinas - SP

José Miguel Chatkin - Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre - RS

José Roberto de Brito Jardim - Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

José Roberto Lapa e Silva - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro - RJ

Kevin Leslie - Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN - USA

Luiz Eduardo Nery - Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Marc Miravitlles - University Hospital Vall d’Hebron - Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain

Marisa Dolhnikoff - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Marli Maria Knorst - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre - RS

Mauro Musa Zamboni - Instituto Nacional do Câncer, Rio de Janeiro - RJ

Nestor Muller - Vancouver General Hospital, Vancouver, BC - Canadá

Noé Zamel - University of Toronto, Toronto, ON - Canadá

Oliver Augusto Nascimento - Universidade Federal de São Paulo - São Paulo - SP

Paul Noble - Duke University, Durham, NC - USA

Paulo Francisco Guerreiro Cardoso - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Paulo Manuel Pêgo Fernandes - Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo - SP

Peter J. Barnes - National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College, London - UK

Renato Sotto Mayor - Hospital Santa Maria, Lisboa - Portugal

Richard W. Light - Vanderbili University, Nashville, TN, USA

Rik Gosselink - University Hospitals Leuven - Bélgica

Robert Skomro - University of Saskatoon, Saskatoon - Canadá

Rubin Tuder - University of Colorado, Denver, CO - USA

Sérgio Saldanha Menna Barreto - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre - RS

Sonia Buist - Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR - USA

Talmadge King Jr. - University of California, San Francisco, CA - USA

Thais Helena Abrahão Thomaz Queluz - Universidade Estadual Paulista, Botucatu - SP

ISSN 1806-3713

Expediente

BRAZILIAN THORACIC SOCIETY

Office: SCS Quadra 01, Bloco K, Asa Sul, salas 203/204. Edifício Denasa, CEP 70398-900, Brasília, DF, Brazil. Tel. +55 61 3245-1030/+55 0800 616218. Website: www.sbpt.org.br. E-mail: sbpt@sbpt.org.br

The Brazilian Journal of Pulmonology (ISSN 1806-3713) is published once every two months by the Brazilian Thoracic Society (BTS). The statements and opinions contained in the editorials and articles in this Journal are solely those of the authors thereof and not of the Journal’s Editor-in-Chief, peer reviewers, the BTS, its officers, regents, members, or employees. Permission is granted to reproduce any figure, table, or other material published in the Journal provided that the source for any of these is credited.

BTS Board of Directors (2017-2018 biennium): President: Fernando Luiz Cavalcanti Lundgren - PE

Secretary-General: Benedito Francisco Cabral Júnior - DF

CFO: Simone Chaves Fagondes - RS

Scientific Director: Ana Luisa Godoy Fernandes - SP

Director, Communications: Fernanda Miranda de Oliveira - GO

Director, Education and Professional Practice:: Irma de Godoy - SP

Director, Professional Advocacy: Marcelo Gervilla Gregório - SP

President, BTS Congress 2018: Marcelo Fouad Rabahi - GO

President Elect (2019/2020 biennium): José Miguel Chatkin - RS

Editor-in-Chief of the Brazilian Journal of Pulmonology: Rogério de Souza - SP

AUDIT COMMITTEE:

Active Members: Ronaldo Rangel Travassos Júnior - PB, Eduardo Felipe Barbosa Silva - DF,

Filadélfia Passos Travassos Martins - CE

Alternates: Leandro Genehr Fitscher - RS, Ciléa Aparecida Victória Martins - ES, Eduardo Pamplona Bethlem - RJ

COORDINATORS, BTS DEPARTMENTS:

Thoracic Surgery – Darcy Ribeiro Pinto Filho -RS

Sleep–disordered Breathing – Pedro Rodrigues Genta -SP

Respiratory Endoscopy – Mauro Musa Zamboni -RJ

Pulmonary Function – Silvia Carla Sousa Rodrigues -SP

Imaging – Pablo Rydz Pinheiro Santana -SP

Lung Diseases – Vera Luiza Capelozzi -SP

Pediatric Pulmonology – Marina Buarque de Almeida -SP

COORDINATORS, BTS SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEES:

Asthma – Maria Alenita de Oliveira - SP

Lung Cancer – Gustavo Faibischew Prado - SP

Pulmonary Circulation – Marcelo Basso Gazzana -SP

Advanced Lung Disease – Paulo Henrique Ramos Feitosa -DF

Interstitial Diseases – José Antônio Baddini Martinez -SP

Environmental and Occupational Respiratory Diseases – Carlos Nunes Tietboehl-Filho -RS

COPD – Frederico Leon Arrabal Fernandes -SP

Epidemiology – Juliana Carvalho Ferreira - SP

Cystic Fibrosis – Rodrigo Abensur Athanazio – SP

Respiratory Infections and Mycoses – Mônica Corso Pereira - SP

Pleura – Roberta Karla Barbosa de Sales -SP

Smoking – Maria da Penha Uchoa Sales - CE

Intensive Care – Eduardo Leite Vieira Costa -SP

Tuberculosis – Denise Rossato Silva -RS

ADMINISTRATIVE SECRETARIAT OF THE BRAZILIAN JOURNAL OF PULMONOLOGY

Address:SCS Quadra 01, Bloco K, Asa Sul, salas 203/204. Edifício Denasa, CEP 70398-900, Brasília, DF, Brazil. Tel. +55 61 3245-1030/+55 0800 616218.

Assistant Managing Editor: Luana Maria Bernardes Campos.

E-mail:jbp@jbp.org.br | jbp@sbpt.org.br

Circulation:4.000 copies

Distribution: Free to members of the BTS and libraries Printed on acid-free paper

ISSN 1806-3713

Published once every two months J Bras Pneumol. v.44, number 5, p. 341-442 September/October 2018

Contents

EDITORIAL

341 - Epidemiology of asthma: it is necessary to expand our concepts

Maria Alenita de Oliveira

343 - Getting to know our pneumococcus

Fernando Luiz Cavalcanti Lundgren

345 - Electronic cigarettes – the new playbook and revamping of the tobacco industry

Ubiratan Paula Santos

347 - Global TB Network: working together to eliminate tuberculosis

Denise Rossato Silva, Adrian Rendon, Jan-Willem Alffenaar, Jeremiah Muhwa Chakaya, Giovanni Sotgiu, Susanna Esposito, Giovanni Battista Migliori

350 - The importance of strong fundamentals in scientific methodology

Rogério Souza

CONTINUING EDUCATION: IMAGING

352 - Paravertebral mass

Edson Marchiori, Bruno Hochhegger, Gláucia Zanetti

CONTINUING EDUCATION: SCIENTIFIC METHODOLOGY

353 - Meeting the assumptions of statistical tests: an important and often forgotten step to reporting valid results

Cecilia Maria Patino Juliana Carvalho Ferreira

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

354 - Asthma mortality in Brazil, 1980-2012: a regional perspective

Thaís de Sá Brito, Ronir Raggio Luiz, José Roberto Lapa e Silva, Hisbello da Silva Campos

361 - Theoretical pneumococcal vaccine coverage: analysis of serotypes isolated from inpatients at a tertiary care hospital

Cynthia Rocha Dullius, Luciana Zani, José Miguel Chatkin

367 - Electronic cigarette awareness and use among students at the Federal University of Mato Grosso, Brazil

Wemerson José Corrêa de Oliveira, Alexandre Figueiredo Zobiole,

Claudia Bonadiman de Lima, Rebeca Melo Zurita, Pedro Eduarto Muniz Flores, Luís Guilherme Val Rodrigues, Raissa Carolina de Assis Pinheiro,

Victor Francisco Figueiredo Rocha Soares e Silva

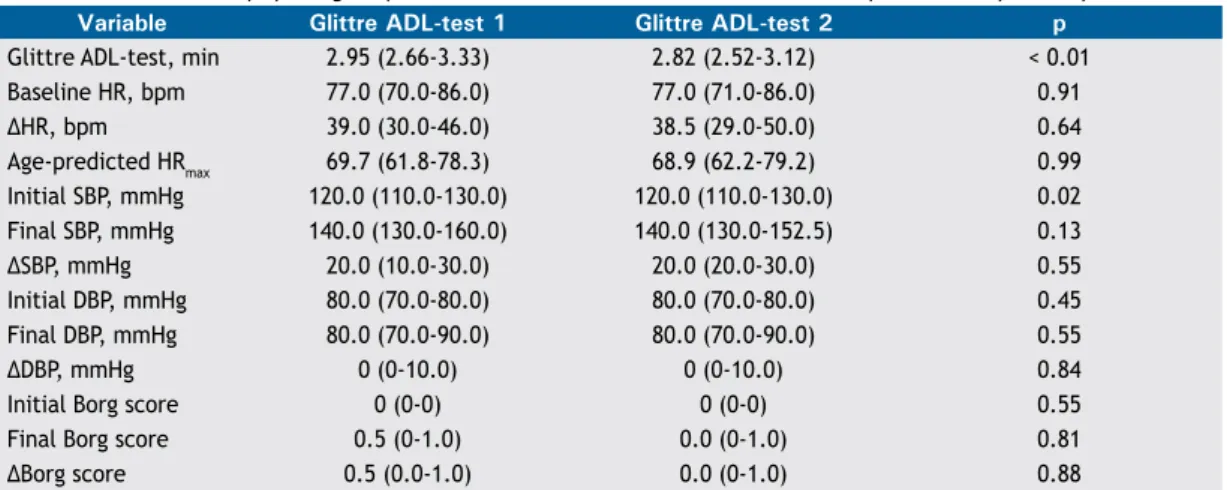

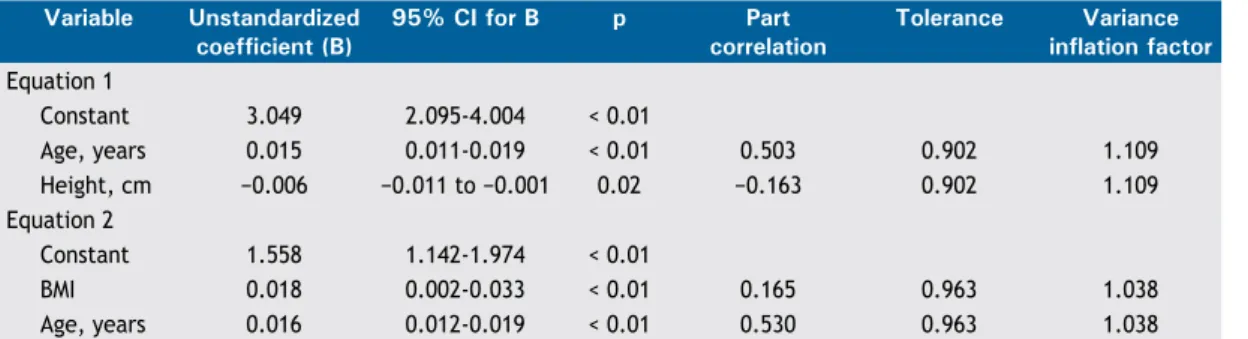

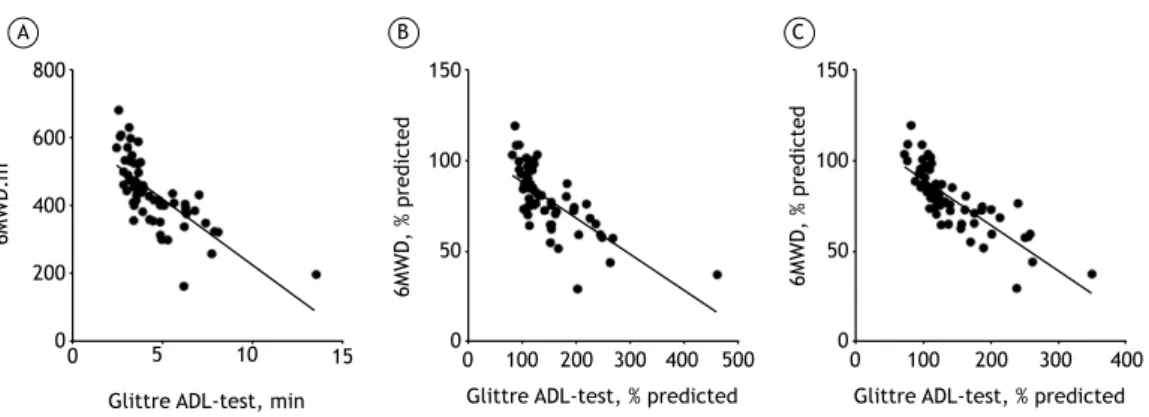

370 - Functional capacity measurement: reference equations for the Glittre Activities of Daily Living test

Cardine Martins dos Reis, Manuela Karloh, Fernanda Rodrigues Fonseca, Roberta Rodolfo Mazzali Biscaro, Giovana Zarpellon Mazo, Anamaria Fleig Mayer

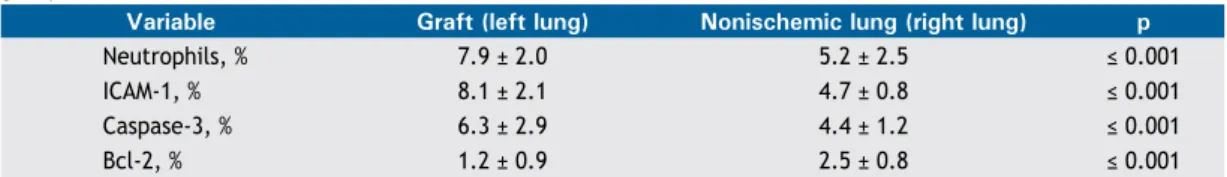

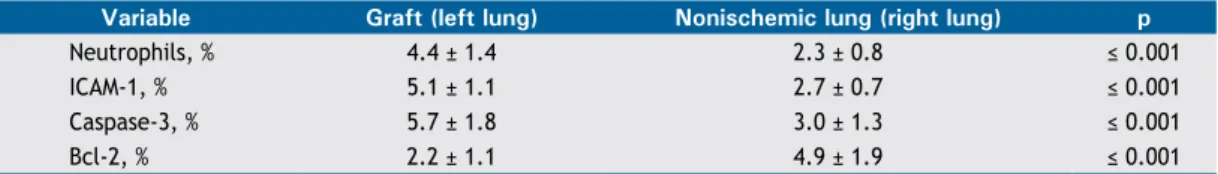

378 - Does methylene blue attenuate inflammation in nonischemic lungs after lung transplantation?

ISSN 1806-3713

Published once every two months J Bras Pneumol. v.44, number 5, p. 341-442 September/October 2018

Contents

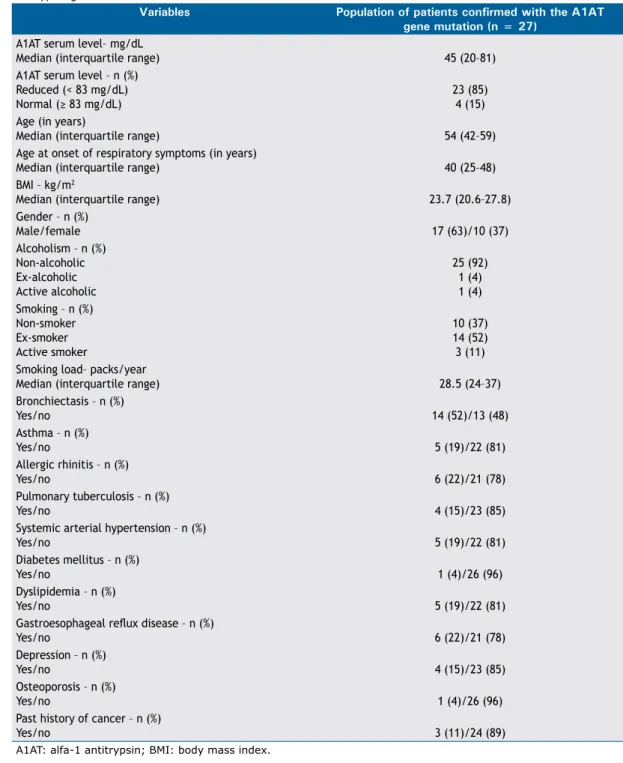

383 - The patient profile of individuals with Alpha-1 antitrypsine gene mutations at a referral center in Brazil

Manuela Brisot Felisbino, Frederico Leon Arrabal Fernandes,

Maria Cecília Nieves Maiorano de Nucci, Regina Maria de Carvalho Pinto, Emilio Pizzichini, Alberto Cukier

390 - Impact of adherence to long-term oxygen therapy on patients with COPD and exertional hypoxemia followed for one year

Carolina Bonfanti Mesquita, Caroline Knaut, Laura Miranda de Oliveira Caram, Renata Ferrari, Silmeia Garcia Zanati Bazan, Irma Godoy, Suzana Erico Tanni

398 - Noncompliance with the law prohibiting the sale of cigarettes to minors in Brazil: an inconvenient truth

André Salem Szklo,Tânia Maria Cavalcante

SPECIAL ARTICLE

405 - 2018 recommendations for the management of community acquired pneumonia

Ricardo de Amorim Corrêa, Andre Nathan Costa, Fernando Lundgren, Lessandra Michelim, Mara Rúbia Figueiredo, Marcelo Holanda, Mauro Gomes, Paulo José Zimermann Teixeira, Ricardo Martins, Rodney Silva, Rodrigo Abensur Athanazio, Rosemeri Maurici da Silva, Mônica Corso Pereira

REVIEW ARTICLE

424 - The pulmonary microbiome: challenges of a new paradigm

André Nathan Costa, Felipe Marques da Costa, Silvia Vidal Campos, Roberta Karla Salles, Rodrigo Abensur Athanazio

IMAGING IN PULMONARY MEDICINE

433 - Hamman’s syndrome

João Filipe Alves Mesquita Rosinhas, Sara Maria Castelo Branco Soares, Adelina Branca Madeira Pereira

CORRESPONDENCE

434 - Clinical aspects of the Mycobacterium abscessus complex

Beuy Joob, Viroj Wiwanitkit

435 - Authors’ reply

José Tadeu Colares Monteiro

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

436 - Smoking cessation before initiation of chemotherapy in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: influence on prognosis

Ana Rita Diegues Linhas, Margarida Carmo Pinho Dias, Ana Maria Paixão Barroso

439 - Omalizumab as add-on therapy in patients with asthma and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis

Fernanda Sales da Cunha, Solange Oliveira Rodrigues Valle, José Elabras Filho, Sérgio Duarte Dortas Júnior, Alfeu Tavares França

442 - Lung transplantation with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as intraoperative support

ISSN 1806-3713

© 2018 Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37562018000050004

Epidemiology of asthma: it is necessary to

expand our concepts

Maria Alenita de Oliveira1,2,a

1. Centro Universitário de João Pessoa – UNIPÊ – João Pessoa (PB) Brasil. 2. Universidade Federal da Paraíba – UFPB – João Pessoa (PB) Brasil. a. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1009-6988

The knowledge on the epidemiology of diseases, based on data on morbidity and mortality, is important, because it allows to create public health policies for disease prevention and to promote investment in key areas in order to improve health care indicators.

In epidemiological studies that evaluate asthma morbidity and mortality, two large databases, which were brilliantly described in an editorial published in the

JBP by Stelmach and Cruz.,(1) have been available for

the population in Brazil. One of these databases, from

the Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de

Saúde (DATASUS, Information Technology Department

of the Brazilian Unified Health Care System), allows the correlation of data in order to demonstrate the trends regarding mortality and morbidity in the various regions of the country, specified by the municipalities. The

second database is provided by the Instituto Brasileiro

de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE, Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics), which allows the analysis of data in a geographical perspective, according to the regions, allowing the classification of urban and rural populations.

The statistical agencies generally adopt two criteria for the classification of urban and rural areas: the political-administrative criterion, adopted until recently in Brazil, and the demographic index, adopted in other parts of

the world, such as Australia and the European Union.(2)

In the present edition of the JBP, the article by Brito et al.(3) analyzed regional data on asthma mortality in

the period between 1980 and 2012. For the analysis of the data, urban and rural areas were defined considering population size, population density, and degree of urbanization, as proposed by Veiga et al.(4);

IBGE adopted this definition in 2017, replacing the political-administrative method, which was adopted in

previous studies. The authors(3) found a reduction in

the mortality rate during the study period, which was similar to the results of previous studies,(4-6) as well as

a predominance in females.

In relation to the analysis by urban and rural areas,

the study of Brito et al.(3) showed a trend toward a

decrease in mortality from asthma in large municipalities;

however, there was an increase in asthma mortality in small and medium-sized municipalities. In relation to rural areas, an increase in asthma mortality was found when compared with that in urban areas, in disagreement with the results found in a study by Ponte et al.,(7) in

which urbanization was associated with higher asthma morbidity and mortality.

The influence of geographic variations on asthma morbidity is important to improve our understanding of the disease so that interventions to reduce its impact can be developed. Factors, such as indoor and outdoor pollution, exposure to allergens, socioeconomic status, and access to health care services, might interfere with morbidity and mortality.(8,9)

One of the examples reported in the article by Brito et al.(3) is the significant bias caused when we classify

a municipality as a participant of a metropolitan area, because it results in a population profile with greater access to health care services. The old classification system, which did not take into account demographic density, could consider some municipalities with small populations but close to large centers as rural municipalities.

Having increased access to health care services is recognized as a factor that reduces morbidity and mortality; in recent years in Brazil, the Family Health Program has provided greater access to health care services for the general population, which might explain the results presented in the study by Brito et al.,(3) since there is

greater access to these facilities in areas with higher population density.(10) However, the increase in mortality

in rural areas might be associated with factors such as socioeconomic status, limited access to medications, or even a greater number of cases diagnosed with asthma, and, consequently, identifying a greater number of asthma-related deaths due to the amplification of the health care network.

The methodology of epidemiological studies, the need for studies that analyze asthma indicators by differentiating between urban and rural areas, and the mechanisms that influence these indicators should be carefully reflected upon, so that health care policies are stimulated to reduce asthma mortality.

REFERENCES

1. Stelmach R, Cruz ÁA. The paradox of asthma: neglect, burden, and big data. J Bras Pneumol. 2017;43(3):159-160. https://doi.org/10.1590/ s1806-37562017000300002

2. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Classificação e caracterização dos espaços rurais e urbanos do Brasil: uma primeira

aproximação. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2017. 84p.

3. Brito TS, Luiz RR, Lapa e Silva JR, Campos HS. Asthma mortality in Brazil, 1980-2012: a regional perspective. J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(5):354-60. 4. Veiga JE. Cidades Imaginárias. Campinas (SP) : Autores Associados;

2002. J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(5):341-342

Epidemiology of asthma: it is necessary to expand our concepts

5. Graudenz GS, Carneiro DP, Vieira RP. Trends in asthma mortality in the 0- to 4-year and 5- to 34-year age groups in Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2017;43(1):24-31. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1806-37562015000000253

6. Cardoso TA, Roncada C, Silva ERD, Pinto LA, Jones MH, Stein RT, et al. The impact of asthma in Brazil: a longitudinal analysis of data from a Brazilian national database system. J Bras Pneumol. 2017;43(3):163-168. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1806-37562016000000352

7. Ponte EV, Cruz AA, Athanazio R, Carvalho-Pinto R, Fernandes FLA, Barreto ML, et al. Urbanization is associated with increased asthma morbidity and mortality in Brazil. Clin Respir J. 2018;12(2):410-417. https://doi.org/10.1111/crj.12530

8. Jie Y, Isa ZM, Jie X, Ju ZL, Ismail NH. Urban vs. rural factors that affect adult asthma. Rev Environ Contam Toxicol. 2013;226:33-63. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-6898-1_2

9. Wright RJ, Subramanian SV. Advancing a multilevel framework for epidemiologic research on asthma disparities. Chest. 2007;132(5 Suppl):757S-769S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.07-1904

ISSN 1806-3713

© 2018 Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37562018000050002

Getting to know our pneumococcus

Fernando Luiz Cavalcanti Lundgren1,2,a1. Coordenador de Residência em Pneumologia, Hospital Otávio de Freitas, Recife (PE) Brasil. 2. Presidente da Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia, Brasília (DF) Brasil. a. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2188-4282

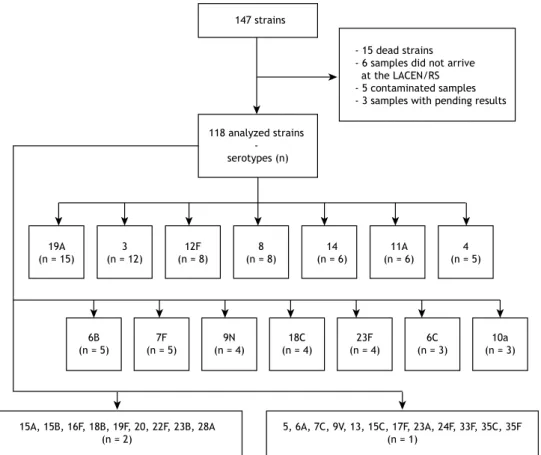

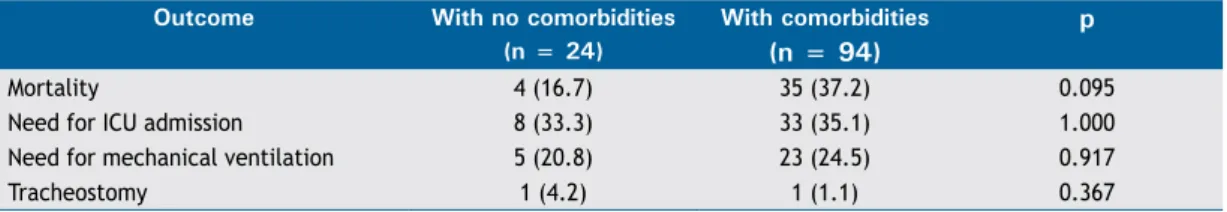

In this issue of the JBP, Dullius et al.(1) present the results

of their study involving a population of adult patients with invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD). Although similar studies have been conducted in populations of pediatric patients and immunosuppressed patients, there have been few such studies involving adult populations.

Among pulmonologists, the most well-known pathogenic bacterium is pneumococcus.(2) The species Streptococcus

pneumoniae causes localized diseases, such as otitis and sinusitis, as well as invasive diseases, such as pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis. There are more than 90 known serotypes, which differ in terms of their aggressiveness and antibiotic resistance profile.(3)

The occurrence of IPDs among adults in Brazil has not been widely studied. Determining the serotype involved can facilitate the prevention and treatment of the disease in our patients.

Although recommendations for the treatment of pneumonia suggest that the agents involved be investigated in critically ill patients, there is as yet no

recommendation for routine pneumococcal serotyping.(3,4)

In Brazil, the antimicrobial resistance of pneumococcus has been shown to be low for penicillins, the group of antibiotics that are most widely used in the treatment of IPDs. Among younger individuals with IPD, the associated hospitalization rate has declined, as has the mortality rate. The higher rates of hospitalization and mortality among older individuals with IPD have been attributed to factors such as immunosenescence and the presence of comorbidities.(5,6)

The study conducted by Dullius et al.,(1) published in this

issue of the JBP, brings us the knowledge of pneumococcus in one region of Brazil (the state of Rio Grande do Sul), as well as of the serotyping of isolates from patients with IPD. A series of cultures were collected over an 11-year period, and the pneumococcal serotypes were correlated with the clinical status recorded in medical records and with the mortality rates found. The strength of their study is that it provides us with information about the pneumococcal strains present in adults with IPD, information not generally obtained in studies of patients followed at a general hospital. All of the samples were collected and cultured at the same hospital. Samples for antimicrobial susceptibility testing were sent, via the state epidemiological surveillance program, to a national referral center for pneumococcal serotyping.

Recognizing the most common serotypes and determining which serotypes are present in patients with severe pneumococcal disease could prompt suggestions

for adopting new therapies and vaccines. The cases in which the culture was positive for pneumococcus were serotyped and later compared to the data in patient charts, which were not specific to the research, those data then being tabulated.

The study could have been more informative if the data on mortality and bacterial resistance to penicillins had been related to the serotype. The most common IPD cases were those of pneumonia, with comorbidities in 85% of the cases and a mortality rate of 33%. Those are comparable to the values reported in other studies of IPD in patients categorized as being at high risk and reflect the fact that the presence of comorbidities increases the difficulty of treating these patients, even with the correct choice of antimicrobial.(7-9) Some pneumococcal strains

are more prone to bacterial resistance and require a differentiated approach.(10,11)

Our knowledge about invasive strains of pneumococci comes from the microbiological surveillance of complex biological samples, such as cerebrospinal fluid and pleural fluid, as well as of blood cultures. A surveillance project on pneumonia and bacterial meningitis at the Adolfo Lutz Institute, in the city of São Paulo,(12) receives such

samples from regional surveillance laboratories throughout Brazil, reporting on the behavior and presentation of the most common serotypes, as well as on their bacterial resistance profiles. The series of confirmed strains has shown changes since the introduction of the pneumococcal vaccine into the national pediatric vaccination schedule. The data from this project show that, in Brazil, pneumococcal resistance to beta-lactams is low in samples collected from individuals with respiratory diseases. Data from the Information Technology Department of the Brazilian Unified Health Care System show that there has been a recent increase in the rates of hospitalization and mortality due to pneumonia in elderly patients.(2)

The use of a pneumococcal vaccine has been associated with a reduction in the incidence of IPD. Two types of anti-pneumococcal vaccines are used in adults: the pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV) and the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV). The PPV does not result in changes in the oropharynx and does not produce the herd effect obtained with the PCVs. The PCV currently available for use in adults is the 13-valent PCV13, which covers the 13 most expected, most aggressive serotypes of pneumococci. Various studies have reported that the PPV provides good coverage for IPD in immunocompetent individuals.(13-16) However, there is a failure of that

protection in immunocompromised individuals and in

J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(5):343-344

Getting to know our pneumococcus

individuals at high risk for IPD. In the at-risk patients, the PCV13 has shown good protection and reduced the incidence of IPD, as well as the number of pneumonias caused by vaccine strains and by strains not covered by the vaccine.(13-16)

The Brazilian Thoracic Association and the Brazilian Immunization Society have recommended the use of the regimen adopted internationally; that is, vaccinating patients with chronic lung diseases with PCV13 followed by the 23-valent PPV, taking age and other aggregated risk factors into account.(17-19) It has become necessary

to monitor changes in the serotypes found in the population in order to modify the vaccine strains and maintain the population coverage for pneumococcus.(20)

In their study, Dullius et al.(1) identified 35

pneumococcal serotypes; the authors theorized that, if the recommended vaccination regimen were used, the coverage would be 50.8%, because the strains

not covered by the existing vaccines accounted for 49% of the cases. The Dullius et al.(1) study has the

merit of indicating the importance of vaccinating our patients, with a potential reduction in the number of cases of IPD and, consequently, mortality.

There is a need for studies, conducted in settings in which patients are treated, that determine the distribution of serotypes and their sensitivity to antimicrobials, as well as evaluating the prior use of pneumococcal vaccines.

Dullius et al.(1) showed that it is possible to work

in collaboration with other institutions, improving treatment and increasing our knowledge of our patients. We hope that the authors will continue to pursue this line of research and will be able to provide us with more answers.

REFERENCES

1. Dullius CR, Zani L, Chatkin JM. Theoretical pneumococcal vaccine coverage: analysis of serotypes isolated from inpatients at a tertiary care hospital. J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(5):361-6 https://doi. org/10.1590/s1806-37562017000000056

2. Correia RA, Lundgren FL, Pereira-Silva JL, Frare e Silva RL, Cardoso AP, Lemos AC, et al. Brazilian guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults - 2009. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;34(6):574-601.

3. Navarro-Torné A, Dias JG, Hruba F, Lopalco PL, Pastore-Celentano L, Amato Gauci AJ, et al. Risk factors for death from invasive pneumococcal disease, Europe, 2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(3):417-25. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2103.140634 4. Lee JS, Giesler DL, Gellad WF, Fine MJ. Antibiotic Therapy for Adults

Hospitalized With Community-Acquired Pneumonia: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2016;315(6):593-602. https://doi.org/10.1001/ jama.2016.0115

5. Lim WS, Smith DL, Wise MP, Welham SA. British Thoracic Society community acquired pneumonia guideline and the NICE pneumonia guideline: how they fit together. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2015;2(1):e000091. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2015-000091 6. Eljaaly K, Alshehri S, Aljabri A, Abraham I, Al Mohajer M, Kalil AC,

et al. Clinical failure with and without empiric atypical bacteria coverage in hospitalized adults with community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):385. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2495-5 7. Falcone M, Tiseo G, Russo A, Giordo L, Manzini E, Bertazzoni G,

et al. Hospitalization for Pneumonia is Associated With Decreased 1-Year Survival in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: Results From a Prospective Cohort Study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(5):e2531. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002531

8. Cillóniz C, Ewig S, Ferrer M, Polverino E, Gabarrús A, Puig de la Bellacasa J, et al. Community-acquired polymicrobial pneumonia in the intensive care unit: aetiology and prognosis. Crit Care. 2011;15(5):R209. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc10444

9. Arnold FW, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, Ramirez JA, Brock GN. Mortality differences among hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia in three world regions: Results from the Community-Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) International Cohort Study. Respir Med. 2013;107(7):1101-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. rmed.2013.04.003

10. Thomas JC, Kong Y, Sabharwal V, Pelton SI, Pettigrew MM. Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 6C: An intra- and interclonal complex comparison. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(13):3409-10. https://doi. org/10.1128/JB.05079-11

11. Pinto TC, Kegele FC, Dias CA, Barros RR, Peralta JM, Merquior VL,

et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae Serotypes 9 and 14 Circulating in Brazil over a 23-Year Period Prior to Introduction of the 10-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine: Role of International Clones in the Evolution of Antimicrobial Resistance and Description of a Novel Genotype. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(11):6664-6672. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00673-16

12. Secretaria do Estado da Saúde do Estado de São Paulo. Coordenadoria de Controle de Doenças. Instituto Adolfo Lutz. Informação da vigilância das pneumonias e meningites bacterianas: Sireva II. São Paulo: Instituto Adolfo Lutz; 2016. 43p.

13. Yildirim I, Shea KM, Pelton SI. Pneumococcal Disease in the Era of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(4):679-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2015.07.009 14. Lamb KE, Flasche S, Diggle M, Inverarity D, Greenhalgh D, Jefferies

JM, et al. Trends in serotypes and sequence types among cases of invasive pneumococcal disease in Scotland, 1999-2010. Vaccine. 2014;32(34):4356-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.079 15. Isturiz R, Webber C. Prevention of adult pneumococcal pneumonia

with the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: CAPiTA, the community-acquired pneumonia immunization trial in adults. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(7):1825-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/216 45515.2015.1043502

16. Mangen MJ, Rozenbaum MH, Huijts SM, Van Werkhoven CH, Postma DF, Atwood M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of adult pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in the Netherlands. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(5):1407-16. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00325-2015

17. Lundgren F, Maranhão B, Martins R, Chatkin JM, Rabahi MF, Corrêa RA, et al. Vaccination in the prevention of infectious respiratory diseases in adults. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2014;60(1):4-15. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9282.60.02.004

18. Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia. Sociedade Brasileira de Imunizações [homepage on the Internet]. Brasília: SBPT [cited 2018 Aug 1]. Pneumologia. Guia de Imunização SBIm/SBPT 2018/19. [Adobe Acrobat document, 34p.]. Available from: https:// sbpt.org.br/portal/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/guia-pneumologia-sbim-2018-2019.pdf

19. Kim DK, Riley LE, Harriman KH, Hunter P, Bridges CB; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Recommended Immunization Schedule for Adults Aged 19 Years or Older, United States, 2017. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(3):209-219. https://doi.org/10.7326/M16-2936

ISSN 1806-3713

© 2018 Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37562018000050003

Electronic cigarettes – the new playbook

and revamping of the tobacco industry

Ubiratan Paula Santos1,a1. Divisão de Pneumologia, Instituto do Coração, Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo (SP) Brasil a. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4919-884X

The smoking epidemic began in the late nineteenth century, driven by the invention of the cigarette making machine. In the twentieth century, it was driven by the advertising industry, the cinema, and the great wars, as well as by the greater circulation of goods and people. The major health hazards of tobacco use have been consistently demonstrated since 1950.(1) Beginning in the 1990s, efficient anti-smoking policies gained momentum worldwide(2), thus reducing the impact on public health. In Brazil, the implementation of anti-smoking policies, such as a ban on cigarette advertising, warnings on cigarette packs, increased dissemination of information about the harmful effects of tobacco use, a ban on smoking in enclosed spaces, an increase in the price of tobacco products, and the expansion of smoking cessation support services, contributed to a significant reduction in the prevalence of smoking among males and females(3), which fell from 43.3% and 27.0%, respectively, in 1989(4) to 12.6% and 8.2%, respectively, in 2015.(5) However, worldwide and in Brazil, smoking is still the second leading risk factor for mortality, there having been an estimated 7.13 million smoking-related deaths in 2016.(6) In addition, approximately 1.1 billion people

≥ 15 years of age still smoke.(7)

In reaction to the world closing ranks against tobacco use, the recent efforts to ban the use of flavorings, and the imposition of laws to make cigarette packaging more generic, the tobacco industry has devised new strategies. The industry seeks to present itself as a defender of public health, has finally recognized the harmful effects of smoking, and has begun to offer alternatives. It has started to produce products such as electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes, heating to near 100°C) and vape pens (vaporizers, heating to near 300°C), both of which supply nicotine in a heated form.

The topic of the moment is the controversy among researchers and medical societies about the use of e-cigarettes to reduce harm or as another treatment option for smoking cessation.(8-11) This new strategy of the

tobacco industry—investing in e-cigarettes and vaporizers as a way of offering nicotine to current smokers and of encouraging smoking initiation—has been the subject of studies worldwide. By manufacturing vaporizers with attractive designs and adding flavorings to e-liquids, the tobacco industry seeks to attract new users, especially young ones, as a means of maintaining the numbers of individuals who are dependent on nicotine, stimulating dual consumption—the burning of tobacco and the vaporizing of nicotine in electronic devices—and thus retaining its lucrative market.

A growing number of studies provide evidence of increased e-cigarette use by young people and that those individuals are more likely to become regular users of tobacco products, due to the perception of reduced risk,

and to become addicted to nicotine.(12) Those factors,

together with the risks of e-cigarettes, which contain not only nicotine, an addictive substance that increases the risk cardiovascular disease, but also numerous toxic chemicals(13) and offer a quantity of inhaled particles that far exceeds the recommended limit for environmental exposure to particulate matter,(14) have led international respiratory medical societies(12) to recommend that the devices be classified and regulated as tobacco products, that their sales to minors be prohibited, and that there be a ban on their use in enclosed spaces (i.e., that they be considered to have a negative environmental impact), encouraging further studies on their effects.

In the study conducted by Oliveira et al.,(15) published in this issue of the JBP, the authors evaluated awareness of e-cigarettes and the frequency of experimentation with/ use of the devices on the part of university students. They found that 37% were aware of e-cigarettes, 2.7% had it experimented with them, and 0.6% used them regularly. The prevalence of e-cigarette use was associated with being younger, having parents with a higher level of education, and having smokers in the family.(15) Although the prevalence of regular e-cigarette use was lower than that reported for other countries,(16,17) as well as being

lower that reported in a study evaluating a sample of individuals over 18 years of age in the Brazilian cities

of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Porto Alegre,(18) the

Oliveira et al. study(15) calls attention to the high rate of awareness of e-cigarettes.

A recently published study, conducted in Canada and involving more than 28,000 individuals of both sexes (15-54 years of age), underscores the need for more attention to be given to the subject.(19) That study revealed that 7.7%, 6.0%, and 4.9% of the participants made use of conventional cigarettes only, e-cigarettes + conventional cigarettes, and e-cigarettes only, respectively. The authors found that the level of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) was higher among the users of e-cigarettes + conventional cigarettes than among the users of conventional cigarettes only. Although the level of ETS exposure among exclusive users of e-cigarettes was lower than that observed for exclusive users of conventional cigarettes, it was still higher than the level of ETS exposure observed for never-smokers, which provides evidence of the behavioral profile of the e-cigarette user.

J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(5):345-346

Electronic cigarettes – the new playbook and revamping of the tobacco industry

In Brazil, the implementation of the abovementioned anti-smoking policies is responsible for the sharp drop in the prevalence of smoking, which should discourage the adoption of policies allowing the marketing of yet another product by the tobacco industry, whether as a strategy for reducing risks or as a tool for promoting smoking cessation. While we await additional research on the impact of the chronic use of the new devices, there are other measures that can be implemented: banning the use of flavorings in cigarettes; curbing the traffic in contraband cigarettes; eliminating the sale

of loose cigarettes at newsstands and other outlets; and expanding smoking cessation support services.

Why should a doctor prescribe a product made by the same industry that, despite having been aware of the disastrous health impacts that its products have, has always been slow to admit that there is such an impact and that nicotine is in fact addictive, steadfastly refusing to pay reparations to its victims, as demonstrated by the exhaustive collection of documents produced by the tobacco industry itself and released to the public

in recent decades?(20) On the basis of the current

knowledge, there is no reason.

REFERENCES

1. DOLL R, HILL AB. Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. Br Med J. 1950;2(4682):739-48. https://doi.org/10.1136/ bmj.2.4682.739

2. World Health Organization. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. 3. Levy D, de Almeida LM, Szklo A. The Brazil SimSmoke policy

simulation model: the effect of strong tobacco control policies on smoking prevalence and smoking-attributable deaths in a middle income nation. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001336. https://doi. org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001336

4. Monteiro CA, Cavalcante TM, Moura EC, Claro RM, Szwarcwald CL. Population-based evidence of a strong decline in the prevalence of smokers in Brazil (1989-2003). Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85(7):527-34. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.06.039073 5. GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators. Smoking prevalence and

attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1885-1906. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0140-6736(17)30819-X

6. GBD 2016 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1345-422. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32366-8

7. Drope J, Schluger NW, editors. The Tobacco Atlas. 6th edition. Atlanta (GA): American Cancer Society, Vital Strategies; 2018. 8. Dautzenberg B, Adler M, Garelik D, Loubrieu JF, Mathern G, Peiffer

G, et al. Practical guidelines on e-cigarettes for practitioners and others health professionals. A French 2016 expert’s statement. Rev Mal Respir. 2017;34(2):155-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. rmr.2017.01.001

9. Yeh JS, Bullen C, Glantz SA. CLINICAL DECISIONS. E-Cigarettes and Smoking Cessation. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(22):2172-4. https://doi. org/10.1056/NEJMclde1602420

10. Aveyard P, Arnott D, Johnson KC. Should we recommend e-cigarettes to help smokers quit? BMJ. 2018;361:k1759. https://doi. org/10.1136/bmj.k1759

11. Schraufnagel DE, Blasi F, Drummond MB, Lam DC, Latif E, Rosen

MJ, et al. Electronic cigarettes. A position statement of the forum of international respiratory societies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(6):611-8. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201407-1198PP 12. Ferkol TW, Farber HJ, La Grutta S, Leone FT, Marshall HM, Neptune

E, et al. Electronic cigarette use in youths: a position statement of the Forum of International Respiratory Societies. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(5). pii: 1800278. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00278-2018

13. Benowitz NL, Fraiman JB. Cardiovascular effects of electronic cigarettes. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14(8):447-456. https://doi. org/10.1038/nrcardio.2017.36

14. Zervas E, Litsiou E, Konstantopoulos K, Poulopoulos S, Katsaounou P. Physical characterization of the aerosol of an electronic cigarette: impact of refill liquids. Inhal Toxicol. 2018; Sep 26:1-6. [Epub ahead of print] https://doi.org/10.1080/08958378.2018.1500662

15. Oliveira WJC, Zobiole AF, Lima CB, Zurita RM, Flores PEM,

Rodrigues LGV, et al. Electronic cigarette awareness and use among students at the Federal University of Mato Grosso, Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(5):367-9. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37562017000000229

16. Gravely S, Fong GT, Cummings KM, Yan M, Quah AC, Borland R, et al. Awareness, trial, and current use of electronic cigarettes in 10 countries: findings from the ITC Project. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(11):11691-704. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijerph111111691

17. Knorst MM, Benedetto IG, Hoffmeister MC, Gazzana MB. The electronic cigarette: the new cigarette of the 21st century? J Bras Pneumol. 2014;40(5):564-72. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132014000500013

18. Cavalcante TM, Szklo AS, Perez CA, Thrasher JF, Szklo M, Ouime J, et al. Electronic cigarette awareness, use, and perception of harmfulness in Brazil: findings from a country that has strict regulatory requirements. Cad Saude Publica. 2017;33Suppl 3(Suppl 3):e00074416. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-311X00074416

19. Nguyen HV, Sheikh A. Environmental tobacco smoke exposure among electronic cigarette users. Addict Behav. 2018;89:92-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.09.026

20. Cummings KM, Brown A, O’Connor R. The cigarette controversy.

ISSN 1806-3713

© 2018 Sociedade Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37562018000000279

Global TB Network: working together to

eliminate tuberculosis

Denise Rossato Silva1,a, Adrian Rendon2,b, Jan-Willem Alffenaar3,c, Jeremiah Muhwa Chakaya4,5,d, Giovanni Sotgiu6,e, Susanna Esposito7,f, Giovanni Battista Migliori8,g

1. Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre (RS) Brasil.

2. Centro de Investigación, Prevención y Tratamiento de Infecciones Respiratorias, Hospital Universitario, Universidad de Monterrey, Monterrey, México. 3. Department of Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands. 4. Union Headquarters, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France.

5. Department of Medicine, Therapeutics, Dermatology and Psychiatry, Kenyatta University, Nairobi, Kenya.

6. Sezione di Epidemiologia Clínica e Statistica Medica, Dipartimento di Scienze Mediche, Chirurgiche e Sperimentali, University degli Studi di Sassari, Sassari, Italia. 7. Sezione di Pediatria generale e specialistica, Dipartimento di Scienze Chirurgiche e Biomediche, Università degli Studi di Perugia, Perugia, Italia.

8. Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico – IRCCS – Tradate, Italia.

a. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0230-2734; b. http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8973-4024; c. http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6703-0288; d. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3229-2429; e. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1600-44740; f. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4103-2837; g. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2597-574X

In spite of the global efforts of the World Health Organization (WHO) and partners to reduce the incidence of tuberculosis (about 2% per year) and its mortality (about 3% per year), the disease is still a global killer and has primary public health importance, with an estimate of 10.4 million cases in 2016.(1)

The End TB Strategy and its vision (zero tuberculosis-related deaths, cases, and suffering) underlies the possibility to eliminate tuberculosis as a public health priority in countries with a low incidence of tuberculosis. (2-4)

Pillar 2 of the End TB Strategy clearly emphasizes the importance of collaboration at different levels. This international collaboration represents the last of the eight core areas to pursue tuberculosis elimination.(4)

Translating that into simple words, international collaboration comprises all of the interactions involving clinicians, laboratory staff, public health officers, national tuberculosis programs, other programs (HIV/AIDS programs and diabetes programs in some countries), Ministries of Health (as well as Ministries of Justice for jails/prisons, Ministries of Interior for the migration-related issues, Ministries of Transportation, etc), private sector, pharmaceutical sector, civil society, representatives of the affected communities, and international organizations, among others.(4,5)

As of today, several TB Networks exist: the Stop TB Partnership(6) has a long tradition in supporting advocacy.

In addition, one of the best examples is the Brazilian Rede

TB, which shows that the best research efforts, even

in a large country as is Brazil, can collaborate to solve country-specific priorities and involve national tuberculosis programs and authorities in the plan.(7-11) However, as

of today, no global tuberculosis network is operational enough to put together all of the abovementioned actors in order to support the fight against tuberculosis.

To respond to this need, the Global TB Network* (GTN) will be launched at the second Conference of the World Association for Infectious Diseases and Immunological Disorders (WAidid),(12) which will take place in the city

of Milan, Italy, from October 18-20 of 2018, involving an international group of experts and covering a wide range of perspectives.

The goal of the GTN is to pursue tuberculosis elimination with a global effort proactively, building on existing collaborations in the area of research, advocacy, and training. Its core objectives are to foster and conduct research on key unmet therapeutic and diagnostic needs in the field of tuberculosis elimination, leveraging on multidisciplinary, multisectoral approaches and supportive interventions (i.e., training and advocacy activities) within the framework of the WHO End TB Strategy. Preliminary plans propose to focus on latent tuberculosis infection, multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis rapid diagnosis, and other neglected areas (pediatric tuberculosis, extrapulmonary tuberculosis, rehabilitation of tuberculosis sequelae, infection control, etc.)

The GTN represents the structured evolution of pre-existing global tuberculosis networks, including the international linezolid, carbapenems and bedaquiline study groups and the International Severe Cases and Rehabilitation Study Group, which produced over 40 articles in the last five years in impact-factor, peer-reviewed journals, as well as various series on tuberculosis in different journals in collaboration with scientific societies,

such as the European Respiratory Society, Sociedade

Brasileira de Pneumologia e Tisiologia, and the Asociación Latinoamericana del Tórax.(13-18)

This new global network aims at collaborating with existing organizations, associations, institutions, and partners that are committed to fight against tuberculosis by complementing and boosting (and not duplicating) the existing initiatives.

The GTN is hosted by WAidid,(12) founded in July of

2014 in order to advance the scientific research in the field of infectious diseases and immunology and to disseminate information on the related pathologies. WAidid is the response to the previous lack of a network that links associations and scientific societies focused on infections, vaccines, and immunology. WAidid, whose membership is free of charge, represents the bridge for a global multidisciplinary approach to infections (including tuberculosis) operating across all age groups.

The GTN is composed of three pillars: J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(5):347-349

Global TB Network: working together to eliminate tuberculosis

Pillar 1 includes the Technical Committees covering the main areas relevant to tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteriosis management (Tuberculosis Prevention/Latent Tuberculosis Infection; Tuberculosis Diagnosis; Tuberculosis Treatment; Tuberculosis Pharmacology; Pediatric Tuberculosis; Migrants/Vulnerable Populations; Nontuberculous Mycobacteriosis; Tuberculosis Infection Control; Impact Evaluation, Strategies & Global Health; Clinical Support to Patients (Tuberculosis Consilium); Clinical Trials; Tuberculosis and Surgery; Basic Science; and Epidemiology, Statistics and Methodology).

Pillar 2 includes representatives from each association/organization active in tuberculosis control interested in participating in the GTN.

Pillar 3 includes the private and pharmaceutical sectors.

Several global projects have already started, including an online clinical service aimed at supporting the correct management of difficult-to-treat tuberculosis cases and of individuals with latent tuberculosis infection, as well as the rational introduction of new drugs; a project monitoring adverse events of new antituberculosis drugs; one study on tuberculosis and surgery; and one study on tuberculosis sequelae and rehabilitation.

We hope this initiative will contribute to reaching the ambitious goals of the End TB Strategy.

*Global TB Network provisional Steering Committee:

Chair: Giovanni Battista Migliori Secretary General: Denise Rossato Silva

Other Members: Jan-Willem Alffenaar, Jeremiah Muhwa Chakaya, Adrian Rendon, Daniela M. Cirillo, James Chalmers, Sergey Borisov, Erlina Buran, Isabel Saraiva, Masae Kawamura (Observer)

Global TB Network Secretariat

Secretariat in Tradate (Italy): Rosella Centis, Lia D’Ambrosio, Dina Visca, Antonio Spanevello

Secretariat in Milano (Italy): Elisabetta Di Felice

Global TB Network Chairs of Committees

TB Pharmacology Committee: Jan-Willem Alffenaar Epidemiology, Statistics and Methodology Committee: Giovanni Sotgiu

TB Prevention/LTBI Committee: Delia Goletti TB Diagnosis Committee: Daniela Maria Cirillo TB Treatment Committee: Marcela Muňoz Torrico Paediatric TB Committee: Ben Marais

Migrants/Vulnerable Populations Committee: Claudia Dobler

NTM Committee: James Chalmers

TB Infection Control Committee: Edward Nardell Impact Evaluation, Strategies & Global Health Committee: Alberto Garcia Basteiro

Clinical Support to Patients (TB Consilium): Marina Tadolini

Clinical Trials Committee: Emanuele Pontali TB and Surgery Committee: Alessandro Mariani Basic Science Committee: Tom H.M. Ottenhoff

World Association for Infectious Diseases and Immunological Disorders (WAidid): President: Susanna Esposito

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

2. Lönnroth K, Migliori GB, Abubakar I, D’Ambrosio L, de Vries G, Diel

R, et al. Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(4):928-52. https://doi. org/10.1183/09031936.00214014

3. D’Ambrosio L, Dara M, Tadolini M, Centis R, Sotgiu G, van der Werf MJ, et al. Tuberculosis elimination: theory and practice in Europe. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(5):1410-20. https://doi. org/10.1183/09031936.00198813

4. Duarte R, Silva DR, Rendon A, Alves TG, Rabahi MF, Centis R, et al. Eliminating tuberculosis in Latin America: making it the point. J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(2):73-76 https://doi.org/10.1590/s1806-37562017000000449

5. Silva DR, Mu-oz-Torrico M, Duarte R, Galvão T, Bonini EH, Arbex FF, et al. Risk factors for tuberculosis: diabetes, smoking, alcohol use, and the use of other drugs. J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(2):145-152. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1806-37562017000000443

6. Stop TB Partnership [homepage on the Internet]. Geneva: Stop TB Partnership; c2018 [updated 2018 Aug 31; cited 2018 Aug 31]. Available from: http://www.stoptb.org/

7. Kritski A, Dalcolmo MP, Mello FCQ, Carvalho ACC, Silva DR, Oliveira MM, et al. The role of the Brazilian Tuberculosis Research Network in national and international efforts to eliminate tuberculosis. J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(2):77-81. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1806-37562017000000435

8. Navarro PD, Almeida IN, Kritski AL, Ceccato MD, Maciel MM,

Carvalho WD, et al. Prevalence of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in prisoners. J Bras Pneumol. 2016;42(5):348-355. https:// doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37562016000000001

9. Moreira Ada S, Huf G, Vieira MA, Fonseca L, Ricks M, Kritski AL. Performance comparison between the mycobacteria growth indicator tube system and Löwenstein-Jensen medium in the routine detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis at public health care facilities in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: preliminary results of a pragmatic clinical trial. J Bras Pneumol. 2013;39(3):365-7. https://doi. org/10.1590/S1806-37132013000300014

10. Ramalho DMP, Miranda PFC, Andrade MK, Brígido T, Dalcolmo MP, Mesquita E, et al. Outcomes from patients with presumed drug resistant tuberculosis in five reference centers in Brazil. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):571. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2669-1 11. de Almeida IN, de Assis Figueredo LJ, Soares VM, Vater MC, Alves

S, da Silva Carvalho W, et al. Evaluation of the Mean Cost and Activity Based Cost in the Diagnosis of Pulmonary Tuberculosis in the Laboratory Routine of a High-Complexity Hospital in Brazil. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:249. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00249

12. World Association for Infectious Diseases and Immunological Disorders (WAidid) [homepage on the Internet]. Milan: WAidid; c2014 [updated 2018 Aug 31; cited 2018 Aug 31]. Available from: http://www.waidid.org/

Silva DR, Rendon A, Alffenaar JW, Chakaya JM, Sotgiu G, Esposito S, Migliori GB

14. Tiberi S, Sotgiu G, D’Ambrosio L, Centis R, Abdo Arbex M, Alarcon Arrascue E, et al. Comparison of effectiveness and safety of imipenem/clavulanate- versus meropenem/clavulanate-containing regimens in the treatment of MDR- and XDR-TB. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(6):1758-66. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00214-2016 15. Tiberi S, Payen MC, Sotgiu G, D’Ambrosio L, Alarcon Guizado

V, Alffenaar JW, et al. Effectiveness and safety of meropenem/ clavulanate-containing regimens in the treatment of MDR- and XDR-TB. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(4):1235-43. https://doi. org/10.1183/13993003.02146-2015

16. Tiberi S, Sotgiu G, D’Ambrosio L, Centis R, Arbex MA, Alarcon Arrascue E, Alffenaar JW, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Imipenem-Clavulanate Added to an Optimized Background Regimen

(OBR) Versus OBR Control Regimens in the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant and Extensively Drug-Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(9):1188-90. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw088

17. Borisov SE, D’Ambrosio L, Centis R, Tiberi S, Dheda K, Alffenaar JW, et al. Outcomes of patients with drug-resistant-tuberculosis treated with bedaquiline-containing regimens and undergoing adjunctive surgery. J Infect. 2018 Aug 7. pii: S0163-4453(18)30246-9. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2018.08.003

18. Munoz M, Tiberi S, Gomez R, Carvalho A, Cordeiro dos Santos M, Ferreira D, et al. Desenlaces de casos graves de tuberculosis en América Latina y Europa [Abstract]. In: Vásquez García JC, editor. Proceedings of the 11th Congreso ALAT (Asociación Latinoamericana del Tórax); 2018 Jun 27-30; Ciudad de México, Mexico; 2018.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37562018000500005

The importance of strong fundamentals in

scientific methodology

Rogério Souza1,2,a

1. Disciplina de Pneumologia, Instituto do Coração, Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo (SP) Brasil. 2. Editor-Chefe do JBP - Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia, Brasília (DF) Brasil.

a. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2789-9143

In recent decades, there has been considerable growth of the scientific literature. Although that growth has not been uniform across the different fields of science, a persistent trend can be seen in the various databases available. In PubMed for example, there was an annual growth rate of more than 5% between 1997 and 2006.(1)

More recently, increases in the number of online journals and the publication of collections of abstracts presented at conferences, as well as expanded access to databases, might have further influenced such growth.

However, such growth is not free from bias—quite the

opposite. A few years ago, an article published in The

Economist, entitled “Unreliable research - Trouble at the Lab,”(2) called attention to numerous problems associated

with the state of scientific literature at that time, such as the low reproducibility of published studies and biases related to the exclusive publication of studies showing positive results, which were potentially influenced by funding sources. In addition, within the academic environment, there is increasing pressure to publish, which results in low-quality articles or the “salami slicing” phenomenon, which is characterized primarily by dividing individual research projects into multiple articles, not only reducing

their relevance but also increasing redundancy.(3)

One of the mechanisms to minimize or at least to discourage many of the current biases in the scientific literature is to encourage a more solid training of researchers in the fundamentals of scientific research. Information regarding the precepts, not only good practices in clinical research but also the associated technical aspects, should first be offered in undergraduate courses and should be maintained throughout the academic life of the researcher, as continuing education.

In terms of the technical aspects, the entire rationale for the design of a study should be understood, from the development of the main research question(4) to the critical

analysis of the methodology used and its limitations, as well as the appropriate use and interpretation of the various statistical tests. Graduate programs tend to focus on those aspects, because their main purpose is to prepare professors and researchers by constructing discipline-specific training centers. However, this initiative seems insufficient, given the extent of the scientific environment and the limited scope of those disciplines.

Scientific journals also play a relevant, albeit less explored, role in this process, not only by creating mechanisms to identify and prevent biases associated with the scientific publishing process but also by disseminating the best practices to be followed. In those two aspects,

there is a pressing need to improve the performance of scientific journals. First, they should be able to identify biases. In general, it is well established that the peer review process, despite its various positive qualities, is unable to identify such biases. The lack of alternative models that do not significantly delay the publishing process has perpetuated this limitation of one of the most common editorial processes. One enormous opportunity that has yet to be taken advantage of by scientific journals is the dissemination of methodological concepts. There are few scientific journals in the field of internal medicine that have sections dedicated to the discussion of the fundamentals of scientific research. The potential gains from the dissemination of this type of knowledge are quite significant, not only in terms of improving the training of researchers but also in terms of increasing the overall critical thinking capacity of readers in general, which can, over time, function as a mechanism to improve the quality of the available scientific research.

What the JBP has specifically been doing over the past four years is publishing a series of articles about continuing

education in scientific methodology,(5) addressing

extremely diverse topics, from how to structure a research project(4,6-8) to the proper interpretation of different types

of studies.(9-11) We are now investigating the impact that

the publication of that series of articles has had on the JBP readership. However, in general terms, those articles have already been being used as a point of reference for researchers in the area.

The dissemination of methodological concepts addresses only one small aspect of the larger problem. Obviously, continuing education plays an important role, although other initiatives are needed in order to improve the scientific research scenario over the next few years. Funding agencies might have to take more direct action in that sense. The use of audits, making the reporting of formal aspects regarding methodology mandatory, and requiring analysis of the results in a more conclusive fashion are actions that can be implemented and added to the current project review format without significantly increasing the bureaucracy involved in the current submission and review processes.

Any interventions in the scientific publishing process should be agreed upon by consensus among the members of academia, funding agencies, scientific journals, and even readerships. Otherwise, the organic growth in the scientific literature will not be accompanied by a similar growth in quality.

J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(5):350-351

Souza R

REFERENCES

1. Larsen PO, von Ins M. The rate of growth in scientific publication and the decline in coverage provided by Science Citation Index. Scientometrics. 2010;84(3):575-603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-010-0202-z

2. The Economist [homepage on the Internet]. London: The Economist; c2018; [updated 2013 Oct 18; cited 2018 Oct 10]. Unreliable research. Trouble at the lab; [about 27 screens]. Available from: https://www.economist.com/briefing/2013/10/18/trouble-at-the-lab

3. Sasaki K, Tan S. Publication ethic (1) “salami slicing”. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25(6):321. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.561 4. Patino CM, Ferreira JC. Developing research questions that make a

difference. J Bras Pneumol. 2016;42(6):403.

5. Souza R. 2016 - a second step. J Bras Pneumol. 2016;42(1):5-6. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37562016000100001

6. Ferreira JC, Patino CM. Types of outcomes in clinical research. J Bras Pneumol. 2017;43(1):5. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1806-37562017000000021

7. Patino CM, Ferreira JC. What is the importance of calculating sample size? J Bras Pneumol. 2016;42(2):162. https://doi.org/10.1590/ S1806-37562016000000114

8. Ferreira JC, Patino CM. Choosing wisely between randomized controlled trials and observational designs in studies about interventions. J Bras Pneumol. 2016;42(3):165. https://doi. org/10.1590/S1806-37562016000000152

9. Ferreira JC, Patino CM. What does the p value really mean? J Bras Pneumol. 2015;41(5):485. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132015000000215

10. Ferreira JC, Patino CM. Understanding diagnostic tests. Part 1. J Bras Pneumol. 2017;43(5):330. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1806-37562017000000330

11. Patino CM, Ferreira JC. Understanding diagnostic tests. Part 2. J Bras Pneumol. 2017;43(6):408. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1806-37562017000000424

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37562018000000256

Paravertebral mass

Edson Marchiori1,a, Bruno Hochhegger2,b, Gláucia Zanetti1,c

1. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro (RJ) Brasil.

2. Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre (RS) Brasil.

a. http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8797-7380; b. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1984-4636; c. http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0261-1860

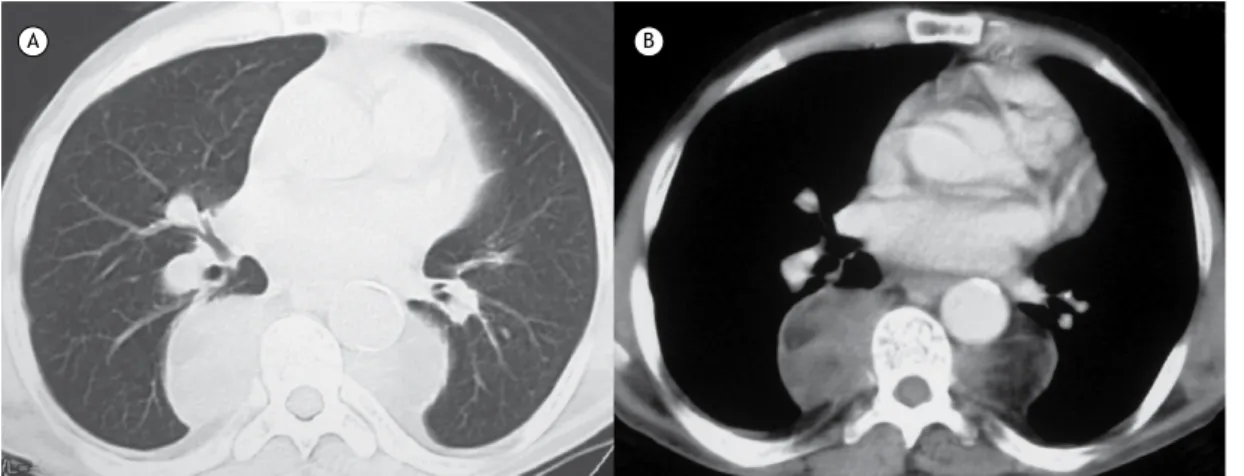

A 59-year-old man presented with anemia and weight loss. He had a history of sickle-cell disease since he was 10 years of age. Chest CT scans revealed bilateral, well-marginated paravertebral masses in the lower half of the thorax, with heterogeneous density (Figure 1). He also presented with a large splenic calcification.

DISCUSSION

The CT features presented by the patient are typical of extramedullary hematopoiesis (EMH), defined as the development and growth of hematopoietic tissue outside the bone marrow. The main considerations in the differential diagnosis of masses in the posterior mediastinum, particularly in the paravertebral region, include neurogenic masses, lymphoma, paravertebral abscess, lateral meningocele, and EMH. EMH is seen in a variety of hematologic disorders, particularly severe hemolytic anemia (thalassemia, sickle-cell anemia, and spherocytosis). Extensive replacement of normal bone marrow occurs when production is insufficient to meet the demands of the body. The most common sites of EMH are the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes, although it can occur in any organ. Thoracic involvement is less frequent, usually manifesting as bilateral lobulated masses in the lower paravertebral areas. The destruction of adjacent

ribs and vertebrae is not seen in EMH. The erythropoietic masses are usually asymptomatic, although the presence of EMH within the spinal canal may be associated with spinal cord compression and neurologic deficit related to the level of involvement. The imaging manifestations of thoracic EMH can be unilateral or bilateral, sharply circumscribed, often lobulated, paraspinal soft-tissue

masses,(1) most frequently seen in the distal thoracic

paraspinal region. CT scans can also be helpful in detecting areas of fat attenuation within these lesions, in depicting bony changes related to hematologic disorders, such as thalassemia and sickle-cell anemia, and in demonstrating splenic infarcts with focal calcifications or a small and dense calcified spleen (autosplenectomy), which can aid the differential diagnosis. The diagnosis of EMH can be established with reasonable certainty on the basis of characteristic radiologic findings in a patient with a predisposing hematologic condition. Invasive diagnostic procedures are potentially hazardous because of the highly vascular nature of the thoracic masses and the hemorrhagic potential of this condition. Microscopic examination shows well-formed hematopoietic tissue. In conclusion, the presence of bilateral, paravertebral masses with associated splenic calcifications are highly suggestive of EMH. The main clinical finding in these patients is anemia.

Figure 1. Chest CT scans with lung window (in A) and mediastinal window (in B) settings showing bilateral masses in the inferior paravertebral thoracic regions. The masses were heterogeneous, with low density areas, suggesting a fatty component. The lung parenchyma showed no abnormalities. There is also a large splenic calcification (not shown).

A B

REFERENCE

1. Marchiori E, Escuissato DL, Irion KL, Zanetti G, Rodrigues RS, Meirelles

GS, et al. Extramedullary hematopoiesis: findings on computed tomography scans of the chest in 6 patients. J Bras Pneumol 2008;34(10):812-6. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132008001000009 J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44(5):352-352