Jorge

Vala

.

Sven Waldzus

Maria

Manuela Calheiros

Editors

The

Social

Developmental

Construction

of

Violence

and

Intergroup Conflict

Editors Jorge Vala

Instituto de Ciências Sociais (ICS-UL) Unive¡sidade de Lisboa

Lisbon Portugal

Maria Manuela Calheiros CIS-IUL

Instituto Universirário de Lisboa (ISCTE) Lisbon

Portugal

Sven Waldzus CIS-ruL

Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE) Lisbon

Portugal

To

Maria

Benedicta

Monteiro

dedicated

social

psychologist,

admired

mentor,

indispensable colleague

and dear

friend

rsBN 978-3-3 t9 -427 26_3 DOI 1 0. 1 007/97 8-3 -319 -427 27 -0

ISBN 978-3-3 19-42727

-0

(eBook) Library of Congress Control Number : 2016944915O Springer Inremarional Publishing Switzerland 2016

This work is.subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whethe¡ the whole or part

of the material is concernecl,

_specificalþ the rights of fa;slation, reprinting, i"ur"-àr illustrations,

recjtation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physicai'way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electlonic aclaptation,

"omputer sofnváre, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter cleveloped.

Th:..ur: of_general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc,

in

this publication does not imply, even in the absenðe of a specific statement, that such names are exempt fromthe relevant protective raws and regulations ancr therãfore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this

book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neittrer tna fuulisher nor the authors or the editors give a wananty, exprcss or implied, witi respect to tne mate¡afcåntained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made.

Printed on acid-free paper

This Springer imprint is published by Springer Nature

Contents

Part

I

Power,

Selfand

Intergroup

Relations1

Power and the

Social Self.Ana

Guinote andAlice

Cai2

From a

Senseof

Setfto

Understanding Relations

BetweenSocialGroups...

Dalila Xavier

de França3

Intergroup

Relations and

Strategiesof

Minorities

.

.

,

.

'

.Joana Alexandre,

Miriam

Rosa and Sven Waldzus3

35

55

Part

II

Social Construction of Identities and Social

Categories4

*Back to

theFuture:"

Ideological Dimensions

of Intergroup

Relations

Jacques-Philippe Leyens and Jorge Vala

5

The Common

Ingroup ldentity Model

and the

Developmentof

aFunctional

Perspective:A

Cross'National Collaboration

Sam Gaertner,

Rita

Guerra, Margarida Rebelo, JohnDovidio,

Erick

Hehman and Mathew Deegan6

When Beliefs

BecomeStronger

than Norms:

Paradoxical

Expressions

of Intergroup

Prejudice

Annelyse Pereira

85

105

r27

Part

III

SocialDevelopmental

Processesof

Violence7

Parent-Child

Interactions

as a Sourceof

Parent

Cognition

in

the Context

of Child Maltreatment

'

. .

'

.Maria

Manuela Calheiros and Leonor Rodriguest45

v111 Contents

8

The Promotion

of

Violence

by

the Mainstream Media

of

Communication

.Patrícia Arriaga,

Dolf

Zillmann

and Francisco Esteves9

Creating a

More

InclusÍve Society:

Social-Developmental Researchon

Intergroup

Relations

in

Childhood

and Adolescence

.João

H.

C.António,

Rita Correia,Allard R.

Feddes and Rita Morais10

The

Multi-Norm Structural

Social-DevelopmentatModel

of Children's Intergroup Attitudes: Integrating

Intergroup-Loyalty

and

Outgroup

FairnessNorms

Ricardo Borges Rodrigues, Adam Rutland and Elizabeth Collins

Contributors

171

t97

219

Joana Alexandre GIS-IUL, Instituto universitário

de

Lisboa

(ISCTE-ruL)'

Lisbon,

PortugalJoão H.C. António CIS-ruL, Instituto

Universitário

de Lisboa

(ISCTE-IUL)'

Lisbon,

PortugalPatrícia

arriaga

CIS-IUL, Instituto universitário

de

Lisboa

(ISCTE-IUL),

Lisbon, Portugal

Alice

Cai

University

Collegeof

London, London,UK

Maria

Manuela

Calheiros

CIS-IUL,

Instituto

Universitário

de

Lisboa(ISCTE-IUL),

Lisbon, PortugalElizabeth Collins CIS-IUL, Instituto Universitário

de

Lisboa

(ISCTE-IUL)'

Lisbon,

PortugalRita

correia

QIS-IUL, Instituto universitário

deLisboa

(IScTE-ruL),

Lisbon,Portugal

Mathew

Deegan University

of

Delaware, Newark,DE, USA

Dalila xavier

deFrança

sergipe Federaluniversity-uFS,

Aracaju,Brazil

John

Dovidio

YaleUniversity, New

Haven,CT, USA

Francisco

Esteves

CIS-ruL, Instituto

UniversitáLriode

Lisboa

(ISCTE-ruL),

Lisbon,

Portugal;Mid

SwedenUniversity,

Hämösand, Swedenallard

R. Feddes university

of

Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The NetherlandsSam

Gaertner

University

of

Delaware, Newark,DE, USA

Rita Guerra CIS-IUL,

Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (ISCTE-IUL),

Lisbon,Portugal

X

Contributors

Ana

Guinote

university college

of

London, London,

uK;

LeardershipKnowledge

center, Nova school of

Business and Economics, Lisbon, portugalErick Hehman

Dartmouth College, Hanover,NH,

USA

Jacques-Philippe

Leyens

catholic university

of Louvain-La-Neuve, Louvain-La_ Neuve, BelgiumRila Morais

cls-ruL,

Instiruto universirário de Lisboa

(IscrE-IUL),

Lisbon, PorlugalAnnelyse

Pereira

cIS-ruL,

Instituto universitário

de

Lisboa

(ISCTE-IUL),

Lisbon,

PortugalMargarida Rebelo

National

Laboraroryof

civil

Engineering(LNEC),

Lisbon,Portugal

Leonor Rodrigues

Institute

of

Sociar sciences(ICS-ulisboa),

universidade

of

Lisbon,

Lisbon, PortugalRicardo

Borges

Rodrigues

CIS-IUL, Instituto

universitário

de

Lisboa(ISCTE-IUL), Lisbon,

PorrugalMiriam

Rosa

cIS-[rL,

Instituto universitário

deLisboa (ISCTE-IUL),

Lisbon. PortugalAdam Rutland

Goldsmiths,University

of

London, London,UK

Jorge

vala

Instituro de ciências sociaisecS-ulisboa),

universidade de Lisboa,Lisbon,

Portugalsven

waldzus

cIS-IIJL,

Instituto universitário

de Lisboa(IscrE-ruL),

Lisbon, PortugalChaPter

4

ooBack

to

the

Future:o' Ideological

Dimensions

of Intergroup

Relations

Jacques-Phiìippe Leyens

and Jorge Vala

Atlstract

Many

phenomena studiedby

social psychology are based on ideologies.Ideologies are ideas

or

systems of ideas inspiredby

values and objectifiedin

social norms about theway

societies should be.This

chapter guides our attentionto

the importanceof

the ideological dimensionof

intergroup relations.This

dimensions had been emphasized aheadyby Tajfel in

his

latestwritings,

but

has then been largely neglectedin

intergroup research.This

chapter covers researchon explicit

ideologies such as colorblindness and

multiculturalism

aswell

as equalitarianism and meritocracy, but also on rather ideology constituting fundamental beliefs such asbelief

in

ajust

world, limited

scopeof justice,

and denialof

full

humanity to outgroup members. The research the authorsreport

demonstrateshow

ideologies and shared fundamental beliefs have a pervasive influence on people's construction of reality and can bias their judgment and their moral feelings, often undetected bytheir

consciousness.Importantly,

these processesare

fundamentalfor

the

legit-imizationof

asymmetric status and power relations between membersof

different social groups.Keywords

Ideologies

.

Intergrouprelations

.

Multiculturalism

'

Meritocracy

'Belief

in

ajust

world .

Infra-humanizationIntroduction

Many phenomena studied

by

social psychology are based on ideologies. Ideologies are ideasor

systemsof

ideas inspiredby

values and objectifiedin

social notms about theway

societies should be. These ideologies can influence the way peopleperceive

the world, and

impact people's behaviors

within social

interactionsJ.-P. Leyens

(X)

Catholic University of Louvain-La-Neuve, Louvain-La-Neuve, Belgium e-mail: jacques-philippe.leyens @uclouvain.be

J. Vala

Instituto de Ciências Sociais (ICS-ULisboa), Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal

O Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016

J. Vala et al. (eds.), The Social Developmental Constntction of Víolence

and Int e r g r o up C onJlict, DOI 1 0. 1 007/97 8-3 -3 19 -427 27 -0

-4

86 J.-P. Leyens and J. Vala

(e.g.,Katz

and Hass 1988; Lerner 1980; Sidanius and Pratto 1999; Guimond et al. 2014).Adopting

an inclusive perspective on the conceptof

ideology(for

a review seeBillig

i984),

this

chapterwill

be devotedto

analyzing therole

of

some core ideological principlesin

the dynamicof

intergroup relations. That is, we focus on the impactof

ideals about sociallife

and specifically about perceived optimal paths toward harmonious intergroup relations on intergroup attitudes and behaviors.lThroughout its history, the study of intergroup relations has been structured by a

diversified

rangeof

theoretical perspectives,from

personality and psychopatho-logical factors(Adomo

etal.

1950) to socio-structural variables (Sherif et al. 196I), cognitive structures(Allport

1954; Hamilton andGuifford

1916), and cognitive andmotivational

mechanisms articulatedby the

Social

Identity

Theory

(Tajfel

andTumer

1979). Despite thefact

that ideologies andtheir

underlying psychological processes wereinitially

considered asimpofiant

factors associatedwith

thetrig-gering, exacerbation, and

mitigation

of

intergroupconflicts, they

did

not

inspiremain

stream research.For

instance, conservatism and authoritarian ideologies are present in the seminal theoretical approach of Adorno et al. (1950) to discrimination againstminority

groups, and"social myths"

concerning socialjustice

wereiden-tified by Tajfel

(1981)

ascore

organizersof

intergroup relations. Despite theseconhibutions, however, the

importanceof

ideologies haseither

been relativelyforgotten

or

the

object

of

radical

criticism (Lichtman

1993).Radical criticism

considers ideologies as literary scenarios (Freeden

et al.2OI3).

Ideologies might be considered scenarios but,far from

beingliterary

options, they determine people's thoughts and behaviors.This

chapterfollows

the

forgotten research avenue openedby Tajfel

(1981),when he proposed the importance

of

ideologiesor

"social myths"

to

understand intergroup relations.First, we

discuss some research results where ideologies are thetriggering

processes.We

will

limit

ourselvesto

researchwe

have personally conducted.This

constraint leads usto

concentrate oncolor

blindness versuscolor

consciousness ideologies (e.g.

Maquil et

al. 2009),belief

in

ajust

world

(Lerner 1980; Correia et al. 2007), and beliefs underlying infra-humanization (Leyens et al. 200'D.2 Second,we

present researchthat highlights the

role

of

egalitarian andmeritocratic ideologies

that

frame

justice norms and mitigate

or

exacerbate lThereare, in fact, diferent focuses on the relationship between ideologies and psychological

phenomena. For instance, Jost et al. (2003) studied some relevant associations between motivated social cognition and conservative ideologies. Our point of view takes another approach: the study of the impact of some core ideological principles about social life on intergroup relations.

zlf

colorblindness and color consciousness are controversial ideological principles applied to "ethnic" relations, the belief in a just world as well as infra-humanization (based on the common

sense prominence of secondary emotions in relation to primary ones concerning the definition of

humanness) are largely diffused ideological principles that constitute important elements of crucial ideological systems. Indeed, the belief

in

a just world is part of conservative ideology and isconsidered a prototype of the ideological level of analysis in social psychology by Doise (1982). Infra-humanization per se is not an ideology but a psychological process associated with the belief that "mine is better than yours," that is, with the ideological principle that suppofts group-lsased

hierarchies (see Sidanius and Pratto 1999).

4

"Back to the Future:" Ideological Dimensions 87inßrgroup conflicts. Finally,

we

conclude

by

insisting

on

the need

for

anenlargement

of

the

study

of

the

role

of

ideologiesin

the

constructionof

psy-chosocial dimensions of social reality and specifically on the constructionof

social categories and the dynamicsof

intergroup relations.This

chapteris

dedicatedto

Maria

BenedictaMonteiro

and honors her contri-butionto

the studyof

violence and intergroup relations. Considering social normsas

the

objectivation

of

values and ideological principles,

this

paper has

been inspiredby Maria's

contribution to the studyof

the impactof

social nonns on the way intergroup attitudesform

and develop (e.g.Monteiro

etal.

2009; França andMonteiro

2013).Disentangling Racially Prejudiced and Non-racially

Prejudiced

Aspects

of Color

Blindness

and

Color

Consciousness

In

1954, the SupremeCourt

of

theU.S.A.

decided that schools should be deseg-regated (seeBrown

vs. Board of Education of Topekain

1954).This

decision was sustained by research published some years before,in

1950,by

Kenneth Clark (seeBenjamin

and Crousse 2002).In

his

research,Clark

concluded that institutional discrimination, and specifically racial segregationin public

schools, was harmful tothe

psychological developmentof

black children.

This point

of

view

was

later developedby

the hypothesis that social categories automaticallyled to

prejudice and that social categories necessarilyimply

ethnocentric conflicts between groups' The same categories were supposed to nourish the negative stereotypes that supportprejudice. Specifically,

research accentuatedthe

role

of

decategorizationin

theelimination of frontiers

(Wilder

1981), and as a pathto

personalized information (Brewer andMiller

1984). Such a perspective can feed theideology

calledcolor

blindness, which posits that the best way to curb prejudice is by treating individuals equally and

without

regard to their color orto their

so-called ethnicity. Supportersof

decategorization were helpedby

the fact that this process favored conditionsof

intergroup contacts

(Allport

1954). This chapter is not the place to develop ideas on contact conditions leading to harmonious relations between groups butit

is proven that,given

the presenceof

those conditions, contactis

the best predictorof

prej-udice reduction (Pettigrew and Tropp 2006). But this line ofreasoning is not a pathwithout

obstacles.For

instance, some authors arguethat the

practiceof

forceddesegregation does not colrespond to appropriate contact conditions (Gerard 1983).

The relation

betweenthe

accentuationof

categorization and negative intergroup attitudes was questioned (e.g. Park and Judd 2005), and more complex modelsof

social categonzation and intergroup harmony andconflict

have been developed bothin

theUSA

(Gaertner andDovidio

2000) and in Europe (Hewstone and Brown88 J.-P. Leyens and J. Vala

Adversaries

of

color

blindnessin

Europe andelsewhere-notably

in

Canada-support

color

conscíousness(or multiculturalism).

Such ideology emphasizes that differences between groups should be recognized, respected, andpositively

eval-uated (Berry et al.20O6; Bourhis et aL1991).In

many ways, color consciousness is incongruentwith

color

blindness. Debates over the advantages and disadvantagesof

both ideologies are not lacking.For

instance,in

France,color

consciousness is condemned becauseit

is

often presumed thatit

will

lead at bestto

communitari-anism or amultiplicity

of neighboring ghettos, and, at worst, to endemic racism (see Guimond 2010).In

fact, the accentuationof

cultural differences between majorities and minorities isempirically

associatedwith

subtle racial prejudice (Pettigrew and Meertens 1995) orwith

cultural racism (Vala and Pereira 2012). On the other hand,color

blindnessis criticized primarily

because equalityis

understood assimilarity

and the

models

for

this similarity are

necessarily membersof

the

dominantmajority.

Consequently, suchsimilarity

meansthe

assimilationof

minorities

by dominant cultural models (Jones 1998) and,from

this perspective, color blindness can promote a society where themajority

doesnot

recognize the negative experi-encesof

minorities and minimizes or makesinvisible

their culture and history.It

isin

this context that, during the past decade, research has accumulated evidencein

favor

of

color consciousness as an ideology that can diminish racial prejudice (e.g.,Apfelbaum et al.

2008;Demoulin

et

al. 2OO2:Nofion

et

al.

2006; Richeson and Nussbaum 2004;Wolsko

etal. 2000,2006;

Verkuyten 2006).Leyens and collaborators (Maquil et al. 2009) took a nuanced approach to the two ideologies

trrg.4.1)

and suggestedthat

eachideology

comprisesa positive

and negative aspect (see also Park and Judd 2005). Theirreasoning was based on two key factors: the importance (high vs. low) attributed to the diversity that characterizes oursocial

world or

the

categoricalethnic

heterogeneityof

a

given

society, and the salience of an ethnocentric worldview (high vs. low). As illustrated inFig.

4. 1, when associatedwith low

ethnocentrism,that is,

recognizinggroup

differences and at sametime

respecting andpositively

evaluating these differences,color

conscious-ness ideology could be associatedwith

the strategyof

acculturation calledintegra-tion

or multiculturalismin

the cultural relations' models proposed byBerry

(2001) ancl by Bourhis etal. (1991). However,if

color consciousness is associated with highImportance of "ethnic" orisins High

colot conscír¡usness

Low Color blindness

Ethnocentrism

Low Integration Individualism

High Segregation Assimilation

Fig.

4.1

Dimensions of color consciousness and color blindness (majorities' perspective). Basedon Maquil et al. (2009)

4

"Back to the Future:" [deological Dimensions 89ethnocentrism, or devaluation

of minorities'

culture,it

can generate the segregation of minorities and express racial prejudice (Pettigrew and Meeltens 1995) or promote the essentializationof

group differences (Verkuyten 2006).On the other hand, color blindness ideology associated

with

low

ethnocentrism correspondsto

a strategyof

acculturation thatBerry

and Bourhis calledindividu-alism, i.e,, recognizing the salience of the uniqueness of each human being over and above social categories.

In

contrast, the combinationof

color

blindness and high ethnocentrism sustains a strategy that produces assimilation, a modelof

accultur-ation basedon

the cultural inferiorization

of

minorities.

In

fact,

sucha

strategy requires that minorities conform to the wayof life

that majorities consider superior, i.e.,their own

culture.This

picture illustrateshow effectively color

blindness and color consciousness have both a dark and abright

side as ideological principlesin

relation

to

cultural relations between asymmetrical groups(Levin

et

al. 2012).In

the contextof

this theoretical framework,Maquil

et al. (2009) tested whetherthe

degreeto

which

people

unconsciously adhereto

the different

strategiesof

acculturation (assimilation,

individualism,

integration-multiculturalism, and segre-gation) correlateswith

the performancein

an intellectual task carried out in different contexts(with

an assimilatedor

with

an integrated parlner). Participants were rall-domly assigned to one of two conditions:in

one condition, participants had to solve a problem togetherwith

a clearly Moroccan female student, dressedin

European style, i.e., completely assimilated;in

another condition, participants had to interactwith

the

same student dressedin

the identical

Europeanclothing but

wearing aMuslim veil

(integrated). The more the Belgian female participants endorsed color conscious ideology (pro-integration of pro-segregation), the better their performance was. Other researchers have already produced such a resultin

White-Black

inter-actions(Dovidio

2001), demonstrating that clear racists or non-racists wete betterin

a task

with

a black person than aversive racists. Moreover, the more students favored assimilation,the

betterthey

performedwhen

theMoroccan

girl

was completely assimilated. This result is not surprising sinceit

corresponds to what assimilation is and wants.More

surprising, atfirst

sight, was the resultof pro-individualism

(po

color blindness and non-ethnocentric) students: they succeeded least when the stu-dent wore the

Muslim veil.

In other words, when Belgian students werein

favorof

individualism,

they

did not

accept

that

others displayed

belongingnessto

agroup. These findings tend

to

show that theindividualistic

strategy, albeit not eth-nocentric, is the one that generates most "misunderstandings"in

social interaction,specifically

more than

integration/multiculturalism

(the other

non-ethnocentric strategy).In

a more general context, other researchby Maquil

et al.

(2009) also showed that both among the majorities and minorities integration and individualism correlated negatively and signiflcantlywith

different measures of prejudice, whereas assimilation and separation cortelatedpositively with

prejudice.Because ideologies are systems of well-entrenched ideas inspired by values, they are often resistant

to

empirical data.For

instance, despite resealch results,multi-culturalism is increasingly criticized

in

GreatBritain, with

the argument being thatghettos are replacing integration

or

that

integration

is

generating segregation. Interestingly, those most opposedto

the non-racist aspectof

color

consciousness90 J.-P. Leyens and J. Vala

(integration

or

multiculturalism)

arethe

non-ethnocentricprocolor

blind

persons(individualists).

The

individualists

supportthe idea that

their

sranceis

rheonly

democratic one (Gauchet 2002). They resist the reality that people,

willingly

or not, are partsof

groups andcould

not

survive

without

group protection. Encounters between two individuals are certainly better than encounters between a Black and aWhite

person.Individualism

is,

however,

impossibleon a

large

scale, whereas integration may attain the aims lookedfor by

individualists: successful integration leadsto

encounters betweenindividuals who

are also membersof

groups.Concerning

the impact

of

assimilationistideology

on

public policies,

Frenchpolicy

toward immigration is clearly shaped by this ideology (Guimondet aI.2014,

2015). France

is

not

alonein

this

domain.In

Flanders,Belgium,

languageis of

paramount impoftance. People speak

different Flemish

dialectsbut

the

Flemish gover'Ílment wants to make Dutch anofficial

language, evenfor

foreigners who donot

plan

to

stay

in

Flanders.The

paradoxin

the vicinity

between France and Flanders is thatif

the Belgian government hadfollowed

French assimilation during the nineteenth century, Flanders would speak French like the rest of Belgium. These examples show a preferencefor official

assimilationist positionsin

France3 andin

Flemish Belgium.

Recently

in

the United Kingdom and Germany, the conservative and center-right have beencalling

for

an endof

multiculturalist policies.

However, research con-tinuesto

show thatmulticultural ideology

can overcome thepotentially

negative aspectsof

salient categorization,that

is,

salienceof

diversity

in

a

given

social context. Indeed,following

the

researchby

Wolsko

et al.

(2000,2006)

into

thepositive impact

of

multiculturalism salience

on

judgments about

groups,Costa-Lopes et" al. (20L4) manipulated the salience of ethnic categories

in

Portugal,as

well

asthe

salienceof

multiculturalism.

Results showedthat

categorizationsalience

led

to

more ingroup bias unless amulticultural ideology

was also made salient.Multiculturalism

buffered the negative impactof

categonzation salience.Color

blindness andcolor

consciousness are the most discussed dimensionsof

ideological

thinking

in

diverse

societiesnot only

by

common people

but,

asillustrated above, by public decision

policy

makers. The importance of a discussion about the advantages and disadvantagesofthose

ideologies is based on the fact that both reflect preoccupationswith

social harmony andtry

to

solve social problems.The

model presentedin

Fig. 4.1

intendsto

enlarge the contextof

the traditional approachto

the ideologies aboutcultural diversity

and goes beyond the modelof

Bery

(2001)

about

acculturation becauseit

integratesacculturation

strategieswithin

the contextof

ideological options.Like

color

blindness andcolor

consciousness ideologies,beliefs

about socialjustice are other crucial factors studied

in

the searchfor

a more harmonious society.3Guimond

et al. (2015) surveyed a representative sample of French people. The results do not corespond to the oficial policy. Whereas the French think that their compatriots are in favor of assimilation, they are in fact pro-integration. Only the extreme rightwing favors assimilation.

4

"Back to the Future:" Ideological Dimensions 91We

will

focus now on the JustWorld

Theory proposedby

Lerner (1980), asit

canopen stimulating contributions

to

the understandingof justice

ideologies as orga-nizersof

intergrouP relations.Belief

in

øjust

World,

Secondøry

Victimization,

ønd

IntergrouP

Relations

According to the

just world

hypothesis(Lemer

1980), individuals consider, at leastimplicitly,

that theworld

isjust

because people get what they deserve and deservewhat they get,

a key

aspectof

conservativeideological thinking.

In

this

sense, injustice,particularly

the sufferingof

innocentvictims,

constitutes a threatto

thebelief

in

a just world,

leading individuals

to

engagein

different

strategies tore-establish the

truth

of

this

fundamental belief,A

logical

andrational

strategy to restorejustice

is to

help the victims through

emotionalor

instrumental supporl, actingfor

example on the conditions that ledto

suffering and injustice. However, when people believe thatit

is impossible or non-normative to help, they engage in strategiesof victims'

secondaryvictimization.

Secondaryvictimization

can assume differentfotms,

such as devaluing thevictims'

sufferingor

implicitly

considering thatthey

deserveto

suffer.This

secondaryvictimization

is

mainly

applied whenvictims

arc perceived as innocent (Correia andVala

2003).An

overviewof

Lerner's theory about thisbelief

in

thejust wodd

shows thatit

wasprimarily

conceivedin

orderto

understand judgmentsof

fairness at theindi-vidual

or

interpersonallevel (Lerner

andClayton 2011; Hafer

and Bègue 2005; Dalbert 2009).Building

on this

research,Coreia

et

al. (2007) extended thejust

world belief to the intergroup levelof

analysis. They formulated and experimentally analyzed the hypothesis that injustices that occurto

innocentvictims only

threaten our beliefin

ajust world

if

the victims belong to"our world"

(our ingroups) but notwhen

victims

are

membersof

outgroups,namely disliked minorities.

In

other words,they

tested the hypothesis thatthe

sufferingof

an outgroupvictim is

not evaluatedwithin

the framework of justice principles.In

oneof

the

studies carriedout

to

testthis

hypothesis (Correiaet

al. 2O0l), participants were confrontedwith

a five-minutefilm

showing achild

experiencing great suffering. The innocenceof

thevictim

was manipulated, aswell

as thevic-tim's

group (achild

belonging to a typical Pofiuguesefamily

vs. achild

belonging to a Gypsyfamily). After

thefilm,

participants were invited to collaboratein

a colorperception

task. This

perceptual

task was actually an

emotional Stroop

task developedby Hafer

(2000), throughwhich

the threatto

thebelief

in

ajust

world

was measured.

In

the perceptual color task, parlicipants were invited toidentify

thecolor

of

a setof

asterisks that appearedon

a computer screen. The displayof

the asterisks was precededby

the subliminal projectionof

aword

relatedor

notwith

justice on the screen.

It

was expected that words related tojustice would

interfere morein

the task (higher latencies)in

the condition where thevictim

was presented92

Innocent

Non-Innocent

Innocent

Non-InnocentIngroup

Outgroupfig.4.2

Meansof

color identification latencies for justice-related wo¡ds and neutral-related words (Based on study 2, in Coneia et al.20O7)as an innocent ingroup

victim.

The resultsfollowing

the hypothesis allowedfor

the interpretation thatonly

the innocentvictim

ofthe

ingroup threatened the observers' beliefin

ajust world (Fig. a.Ð.

These results were replicatedin

other experiments whereit

was also possibleto verify

when,in

an intergroup context, an innocentvictim

is

more

likely to be

the

targetof

secondaryvictimization (Aguiar

et

al.2008).

Aguiar et al. (2008) designed their studies based on the scenario used by Correia

et

al. (2001). Oneof

these studies analyzed the degreeof

victim

discrimination, aform

of

secondaryvictimization.

As

in

previous

studies, participantswere

con-fronted

with

afilm

about a child who was presented as an ingroup member (achild

belonging

to

a typical

Portuguesefamily)

versus an outgroup member(a

gypsychild,

asin

previous studies). However,in

this new research, the authors notonly

manipulated the group the

child

belongedto but

also contrasted his status(victim

vs. non

victim).

The derogationof

the targetchild

was evaluated using animplicit

measure, called o'intergroup time bias"

(ITB)

(Vala etal.2Ol2).

The intergroup time bias refersto

the time

people investmaking

ajudgment

abouta

target (e.g. an ingroup member) comparedwith

thetime

spent on the same judgment relative to another target (e.g. an outgoup member). To measureITB,

participants were invited to form an accurate impression oftargets indicating whether or not traits that appearon

a computer screenapply to

those targetsor

not. The time

spenton trait

attri-bution

(andnot their

valence)to

the

targets indicatesthe

interestand

attention deservedby

targets:the

longer

the

time

invested

by

participants

to

form

an impression, the greater the value of the target under evaluation. In the experimentof

Aguiar

et al. (2008), participants formed an impression aboutfour

targets (ingroup vs. outgroupchild;

victim

vs. non-victim).As expected, the

victim

of the ingroup was more derogated (less time invested toform

an

impression

of

ingroup

victim) than the non-victim

of

the

ingroup. According to our interpretation, this occurred because the ingroupvictim

threatenedJ.-P. Leyens and J. Vala

800 750 700 650 600 550 -500

I

n Justice Neutral4

"Back to the Future:" Ideological Dimensions 93paficipants' belief

in

ajust

world.

Moreover, participants invested the same timejudging

thevictim

andnon-victim of

the outgroup because outgroup membersdid

not threaten their belief in a

just

world.In

sum, together, these studies show that the sufferingof

ingroupmembers-but

notof

disliked outgrôupmembers-is

affected by justice concerns. Moreover, this last research also shows that, paradoxically, aningroup

victim is

ryore derogatedor

the objectof

more secondary victimization than an outgroup victim.It

wasin

this research context that Correiaef

al. (2007) proposedrevisiting

the conceptof

scopeof

justice

(Deutsch 1985;

Opotow

1990; Staub

1990). This concept proposesthat people

createideological frontiers

for the

application

of

justice principles and, consequently, that some people are excluded

from

the 'Justworld."

Indeed Lima-Nunes

et

al.

(2013)

found that the

relationship

betweenprejudice and discrimination against immigrants is mediated by a restricted scope

of

justice. This mediation is moderated by people's belief

in

ajust world.

Specifically, the mediationonly

occursfor

high

believers. Moreover, the relevanceof

the phe-nomena describedis

stressedby

the resultsof Alves

and Correia (2013) demon-strating that thebelief

in

ajust

world

is

socially normative.That is,

thisbelief

is perceivedas

a

socially valued

way

of

thinking

and

an

acceptableprinciple

of

legitimation

of

social relations (Costâ-Lopes etal.

2013).Graded

Humnnity

Relíes

on Metaphorical

ldeologies

About

Alterations

of

Humanness

Results presented

in

the

previous section

suggestthat not

all

human

beings,including ingroup

members, are includedin

the scopeof justice. This is

perhaps because not all human beings are perceived to be part of our moral community and are perceived as not totally human. Indeed, it is not infrequent that some groups label themselvesas

'opeople"or, like

the

Bantus,call

themselves"humans" and

call neighboring groups derogative names such as "louse's eggs."As

will

be seen later, dehumanization is oftenlinked to

human-made disasters such as genocides (Staub 1989). However,this

extremity

is

not

necessary and peoplemay

unconsciously dehumanize outgroupsin

everyday life.The

broadest sense

of

dehumanízationis

the

restriction

of

humanness. Dehumanized groups are not as human as our group is. Two metaphors are normally used to describe the dehumanized groups (Haslam 2006). Either they arelike

ani-mals (animalistic dehumanization)or they look

like

objectsor

machines(mecha-nistic

dehumanization). Thesetwo

types

of

dehumanization correspondto

twodistinct kinds of humanness. Humanity may be defined in terms

of

what is uniquely human compared to animals.It

is the case of uniquely human or secondary emotions (e.g.,love,

admiration, contempt,envy)

in

oppositionto

non-uniquely human or primary emotions (e.g., happiness, surprise, fear, sadness).It

can also be defined by the negative core characteristics thatform

human nature (e.g., narrow-mindedness,94 J.-P. Leyens and J. Vala

stubbornness).

While the first definition

contrasts humansto

animals

(human uniqueness), the second one opposes humans to robots (human nature). Believingin

the humanity

of

ingroups and perceiving outgroups as less valuableis

partof

the principle that "mine is better than yours," andit

stems from the ideas that sustain andlegitimate

group-based hierarchies (see Sidanius and Prattoi999). In

this section,we

will

focus on infra-humanization, that is, thebelief

that outgroup members areless human than we are, and that they are closer to animals than we are (Leyens et al.

2000,2007).It

is a perception of graded humanity that should not be confusedwith

dehumanization,

where the

gradientof

humanity

is

reducedto

almost

nothing (Leyens 2015).Infra-humanization

is

particularly importantin

the understandingof

intergroup relations becauseit

does not needconflicting

relations between groups.It

requiresidentification

of

group

memberswith

their group,

aswell

as the perception thatone's

group

is

different

from

outgroups.

Another important predictor of

infia-humanization has

to

dowith

symbolic threat, thatis,

the threat that customs and valueswill

change due to the actionof

outgroups. The symbolic threat means that ingroup ideologyis

atrisk.

Stated otherwise, because our common ideology is threatened, we reactwith

another ideological principle, the ingroup superiority and related outgroup infra-humanizationthaf restores our group's perceived high status. The first studies about this topic appeared at the endoflast

century, and today anincreasing

number

of

them,

over

140

publications,

show

the

functions of

infia-humanization (Leyens 2009; Haslam and Loughnan 2014).

For

instance, byinfra-humanizing outgroups, people

do

not feel culpability

in

harming

them. Infra-humanizationalso

alleviatesresponsibility,

andjustifies

not

helping

needy persons. Moreover,it

explainswhy

discrimination may occurwithout

feelingsof

guilt.

Infra-humanization is also a specific formof

derogationof

outgroups that are not socially successful. To take an example, a study conductedinBrazil

(Lima

andYala

2004) showedhow

economic success isideologically linked with

skin color.In

this investigation, White Brazilian participants were presentedwith

a story about people that succeeded or that failed in their endeavor. The descriptionofpeople

wasillustrated

with

picturesof

Black

people versus thoseof

White

people. Pre-testsindicated

that

those people were clearly perceived as

Black

or

White

people.Independently

of

color,

targets

that

did not

succeedwere

infra-humanized. Surprisingly, peoplewho

succeeded were perceived as whiter than people whodid

not.

By

contrast, individuals who failed economically were perceived as darker thanpeople

that

succeeded.For Black

people,the judgment

is

clear:

their color

is associatedwith

failure and, as a consequence, with reduced humanity. The situationis

ambiguousfor

Whites. Their colorwill

depend ontheir

success and,if

theyfail,

they

will

become infra-humanized"Mulattoes."

Thus, 'oMulattoes" have thecolor

of

successful Blacks and offailing

Whites.Fiske

et

al. (2002) havebuilt

a stereotype content modelof

groups around two orthogonal dimensions: warmth and competence. Rich people,for

instance,will

bein

the high competence/low warmth quadrant,while

a housewifewill

bein

thelow

competenceihigh warmth quadrant.

Using

neurological imaging,Harris

and Fiske (2006) showed that the brainactivity

associatedwith

thelodlow

quadrant, such as4

"Back to the Future:" Ideological Dimensions 95the homeless and drug addicts was more similar to the brain

activity

pattem that is usually observedin

situationswith

objects thanin

situationwith

people. That is, these results suggest that peoplein

thelow/low

quadrant are no longer considered human, but disgusting objects.Similarly,

Vaes and PaladiÌro (2010) found that the more typical the characteristics oflow/low

groups are, the less human they are rated (see also Leyenset

al.2012).Research

on

dehumanizationis

still

in

limbo

and

careshould

be

taken,

asillustrated

in

thefollowing

study.Morera

et

al.(2014)

have shown that the dis-tinction between animalistic and mechanistic dehumanization and the convergence between peoplelow

in

competence andwatmth and

non-humanity arenot

that stable. Participants had to associate human, animal, and machine wordswith

three groupsof

people: professionals (e.g. radiologists, bankers),evil

persons(e.g.

a mercenary and a terrorist), and the lowest of thelow

people,like

a homeless person and adrug

addict. Professionals werelinked

to

human words;evil

persons were associatedto

animals ønd machines;finally

the lowestof

thelow

received animal qndhuman words.Evil

persons thus mixed the two kinds of dehumanization. Drug addicts and the homeless may have been seen as humans given the Spanish context where many people lost theirjobs

and homes becauseof

the ûnancial crisis. These findings do notput

earlier results atrisk but

suggest that social context caninflu-ence the meaning

of

social categories and, consequently, the infra-humanization process.E q

uølitarinnism,

M

eríto

cracy, and

Intergroup

Relntio ns

We

will

now

discussour

researchinto

therole

of

equalitarian and meritocratic ideologies that shapejustice

norms on the expression and consequencesof

preju-dice. Wewill

startby

studies on the roleof

equalitarianism and meritocracyin

the effects of infra-humanization and then wewill

discuss our research on the impactof

those ideological principles on racial prejudice.Egalitarianism,

Meritocracy,

and

Infra-Humanization

As

mentioned above, several studies have shownthat

infra-humanizationis

not inevitable and can be moderatedby

different social factors (Vaeset

al.2012,

lor

a review). Importantly, as reportedin

a study carried out by Pereira et al. (2009), the impactof

infra-humanizafionon

discdminationmay

be moderatedby

egalitarian and meritocratic ideologies.In

the study, participantsfirst

received an articlesup-posedly taken

from

a

prestigious

weekly

newspaper.In

order

to

manipulafe infra-humanization of Turkish people, for a third of the subjects, the article reported a study showingthat

the ancientTurkish

language was comparableto

European languagesin

the

frequencyof

secondary emotions words.For

anotherthird,

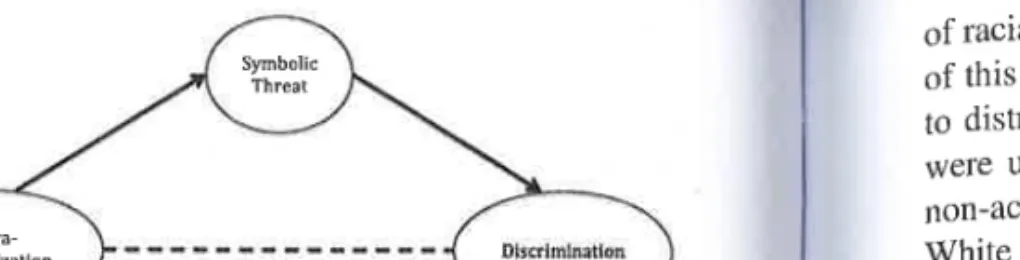

theSymbolic Threet

Infia-Hmanization

96 J.-P. Leyens and J. Vala

Fig.

4.3

Efect of infra-humanization on discrimination againstTurkey, mediated by

syn-rbolic threat after egalitarian norm prime (Based

on Pereira et al. 2009)

vocabulary.

In

thethird

condition

(thecontrol condition),

thetext

dealtwith

therelationship between age

and

learning

a

new

language.Symbolic threat

and opposition to the entranceof

Turkeyin

theEU

were the main dependent variables. Participants exhibited greater openness to Turkey'sjoining

the European Union and expressed a lesser feeling of threat when Turkish was described as similar to theEuropean languages concerning

the

frequency

of

secondary

emotions(non-infra-humanization

condition) than when

it

was

presentedas

dissimilar. Interestingly, symbolic threat mediated thelink

between the differential perceptionof

Turkish

(infra-humanizationvs.

humanization) and the oppositionto

Turkey's enlrance in the European Union. That is, the differential perception of Turkey led to different levelsofthreat

that explained the degreeofopposition

to Turkey as partof

Europe (Fig. 4.3).

In

afollow-up

study, infra-humanization was manipulated and participants were primedwith

egalitarian versus meritocratic ideologies. Independentlyof

theideo-logical

manipulation, infra-humanization had an effecton

symbolic threat and onthe

oppositionto

Turkey's

entrancein

EuropeanUnion. The

interesting finding dealswith

the

mediation.When

meritocracywas

salient (primed), there was no mediation.It

was not the case when egalitarianism was primed. Parlicipants primedwith

an egalitarian normfelt

the need to explain their discrimination against Turkey through the evocationof

thesymbolic

threat.This justification

was unnecessarywhen the context

promoted meritocracy,that

is,

when

it

was

salientthat

some groups, dueto their

characteristics, deserve more and are superiorto

others. This study illustrated how egalitarianism and meritocracy have different implicationsfor

the legitimation

of

discrimination and the relationship between infra-humanization and discrimination.Egalitarianism,

Meritocracy,

and Racial Prejudice

Inspired

by

Sherif

andSherif's

(1953) group norms theoryof

attitudes, Crandallet

al. (2002) developed a normative theory about prejudice.This

theory proposes that social norms affect the expressionof

prejudice, i.e., prejudice decreases when group norrns proscribeit

and increases when they are permissive.In

the same vein,Monteiro

and

collaborators(Monteiro

et al.

2009;

Françaand Monteiro

2013)specifically analyzed the impact

ofthe

anti-racism norm salience on the expression4

"Back to the Future:" Ideological Dimensions 97of racial prejudice by children.

In

atypical

study of this researchline

(see Chap. 10of

this book), the experimenter asked 6-7-year-old children versus9-10

years old to distribute resourcesto Black

andWhite

children.Two

experimental conditions were used: activationof

the anti-racistnorm

(the experinienteris

present) versusnon-activation

(the

experimenteris

absent).Results showed

that

6-7-year-old White children expressed prejudice independentlyof

thenorm's

salience, whereas the9-10-year-old

only

discriminated againstBlack children when the

anti-racistnorm was

not

activated. Thesefindings

suggestthat older children

areable

tomonitor

their

behavior

in

accordancewith

group

norm

salience.Similarly,

the theoryof

aversive racism (Gaertner andDovidio

1986) stresses the importanceof

contextual anti-racism norms

on

the expressionof

racial

prejudice.According

tothis

theory,when the

interactioncontext

indicatesthe socially

desirabletype

of

response, or when individuals feel that their self-def,nition as egalitarian subjects is

in

question, they are lesslikely

tothink

and actin

a discriminatory way.Another

line of

research openedby

Katz

and Hass (1988) examined the rela-tionship betweennoms

and racial prejudice using a different perspective. This lineof

research focusedon two

oppositeideological

perspectives aboutjustice:

one based on the valueof

egalitarianism and the other based on the valueof

meritoc-racy. According to the authors' hypotheses, thepriming

of egalitarianism attenuated racial prejudice, whereas the priming of meritocracy exacerbatedit.

As proposed by Sidaniusand Pratto (1999), meritocracy and

egalitarianismconespond

to

two oppositelegitimizing myths

regardingsocial

dominance: one, meritocracy,is

a hierarchy-enheurcingmyth

accordingto

which

groups are unequal; and the othel, egalitarianism,is a

hierarchy-attenuatingmyth.

Consequently,the

salienceof

hieralchy-enhancing

myths,

like

meritocracy,in

contrastto

egalitarianism, con-tributesto

greater levelsof

racial-basedinequality

as shownin

the studyof

Katz

and Hass (1988).

Following this line

of

research, Pereira andVala

(2014) carried out a seriesof

studies to examine the impact of egalitarianism and meritocracy on the "Intergroup TimeBias"

(ITB) in

impression formation, that is, pro-ingroup bias manifestedin

the

time

investedto

make

ajudgment

aboutan ingroup

memberrelative

to

anoutgroup member.

As

mentioned above,they

proposed thattime

is

an important resource and, consequently, peoplewill

invest more timein

ingroup than outgroup members, when racialized social relations areat

stake(Vala

et

al. 2012).In

this context, less time investedin

the outgroup relativeto

the ingroup means outgroupdiscrimination.

According

to

Pereiraand Vala

(2014),

the

ITB

effect can

be moderatedby

the contextual activationof

egalitarianism and meritocracy.In

their study, participants wererandomly

assignedto

oneof

thefollowing

conditions: a condition where they were primedwith

the egalitarian norm; another one where the meritocratic norrn wasprimed;

and acontrol

(no prime). Results showed that theactivation

of

egalitarianismsignificantly

reducedthe

ITB

effect relative

to

thecontrol condition.

However, meritocracydid

not significantly

increaseITB.

Thislater result can

be

discussedin

the

context

of

the

diverse social

meaningsof

meritocracy. Indeed,

Son

Hing et al.

(2011)

showedthat

meritocracy can mean different things to people: descriptive meritocracy, that is the perception that society98 J.-P. Leyens and J. Vala

actually rewards effort and merit; or prescriptive meritocracy, that is, an ideal about the functioning

of

a society, a society where effort andmerit

should be effectively rewarded.According

to

SonHing et al.

(2011)the

later meaningof

meritocracy functions as a principleofjustice

whereas descriptive meritocracy is associatedwith

the

legitimization

of

social inequalities. Coming backto

the resultsof

Pereira andYala

(2014),it

seemsvery

likely

that the manipulationof

meritocracythey

used was perceived by participants as a mixture of prescriptive and descriptive meaningsof

meritocracy and, consequently,only slightly

increased outgroup discrimination.Egalitarianism also has different

meanings.A

study

by Lima et al.

(2005) showed that descriptive meritocracyclearly

increased theimplicit

racial prejudice measuredby

the

IAT

(Greenwaldet

al.

1998). However,

egalitarianism only reducedimplicit

prejudice whenprimed

as"solidarity

egalitarianism"(i.e.

socialegalitarianism

that involves solidarity

between

citizens)

but

no

effects

were obtained whenit

was primed as"formal

egalitarianism"(in

the senseof

constitu-tional

equalityof rights

and dutiesfor

all).Despite the ambiguity

of

the meaningsof

egalitarianism and meritocracy,liter-ature

is not

scarce about the effectsof

these normativeprinciples on

intergroup attitudes.Work

by Augoustinos et al. (2005) further illustrates this. They examined anti-affirmative action attitudesin

Australia and demonstrated that attitudes corre-latedto

the endorsementof

meritocratic orientations. Thepriming

of

meritocracy also led membersof low

status groups to perceive that they were not discriminated against(McCoy

andMajor

2006),On

the contrary,the

contextual activationof

egalitarianism

facilitates individuation

in

impressionformation (Goodwin

et

al. 2000). In the same vein, Bodenhausen and Macrae (1998) suggest that the egalitarian norrn mayinhibit

the categonzation of members ofminority

groups, andMaio

et al. (2001) report effectsofthe

salience ofreasons for equality on egalitarian behaviorin

a

minimal

group paradigm.Using

representative samplesof

European countries, Vala et al. (2004) and Ramos and Vala (2009) showed that egalitarianism predicts positive attitudes toward immigrants whereas meritocracy predicts negative ones.Conclusions

Humans are social beings and,

for

most aspectsof their

wellbeing, people need to interactwith privileged

others and these others are at theorigin

of

groups. Social psychology theorized groups as a resultof

the social categorization process and,in

this

sense, groups arelike

boundaries.But history

tells us that boundaries alwaysimply

more

or

less cooperativeor

conflicting relations

andthat

boundaries andrelations are fed

by beliefs

and ideologies. Most research has been dedicated to the studyof

boundaries through the processof

social categorization andits

dynamicthat

createsgroups,

superordinategroups,

recategonzationof

groups,

or

evenimplosion

of

groupsvia

decategonzation. Less research has been directedto

thestudy

of

group

relations

and how the

nature

of

those relations moves

fromcooperation to

conflict

and shapes people's minds and collective action. Even less4

"Back to the Future:" Ideological Dimensions 99research has studied the

way

ideologies configure categories and intergrouprela-tions. This

chapter

aims

to

contribute

to

underlining

and

foregrounding

theimportance

of

researchon

ideologies

and

intergroup

creation and

relations. Nevertheless, ideologies were present at the beginningof

theinquiry

about inter-groupconflict,

as can be illustratedby

the research program developed byAdomo

et al.

(1950) and inspiredby

the intellectual climateof

theFrankfurt

School.In

addition, the last paper

by Tajfel

(1984) dealswith

ideologies,justice,

and inter-group relations.Accordingly,

ideologies that trigger intergroup processes are presented and dis-cussedin

this

chapter: ideologiesof

color blind/color

consciousness about inter-group differences and the constructionofjuster

societies; thebeliefin ajust

world, based on the conservative ideology, and its impact on ingroup and outgroupvictims'

evaluations;

the

ideas about humannessthat

structurethe

infra-humanizationof

groups

in

the context

of

a

bounded scopeof

justice

and group-based hierarchy ideologies; andfinally

meritocratic and egalitarian ideologies objectifiedin

socialnorns.

In

other words,we

proposed andtried

to

showhow

ideologies and their conespondent social norms inspire the efforts to regulate diverse societies, establishthe

boundariesof

humanness, andunderlie the

meaningsof justice

and justice principles thatjustify

racial prejudice and discrimination.This chapter has been

mainly

structuredby

our own research and its relation to the researchof

other authorswho

sharesimilar

perspectiveson

therole

of

ide-ologiesin

intergroup relations.This

option has allowed us to present our approachand

research.However,

it

excludesthe

discussionof

important

dimensionsof

intergroup relations also shaped

by

ideologies,like

the studyof

extreme formsof

conflict,

such as nationalism (Staub 1989;Billig

1995), dehumanizing, moral dis-engagement, anddeligitimization

(Bandura 1999;Bar-Tal

2004), to givejust

a few examples. Indeed, thebanality

of

torture after September 11, the current reemer-genceof

nationalism

in

Europe, the religious

neo-extremisms,the

banality

of

submission

in

the

different

spheresof

society should

be the

object

of

urgent researchby

social

psychologistsin

the

context

of

an

inclusive

conceptionof

ideologies.

To sum up, group boundaries are sometimes

like

walls. Because groups and their boundaries are social constructions, ideologies have arole

in

this

landscape too. Ideologies may reinforce the strength of the walldividing

groups, but they may also indicate holesin

the

concrete,or

even produce them,In

fact,

boundaries are no more than whatwe

makeof

them and the cementis

providedby

our ideas about what societies should be.Àcknowledgments The authors want to thank Denis Sindic, Rob Outten, Cicero Pereira, Rui

Costa Lopes, Sven Waldzus, Isabel Correia, and Pedro Magalhães for providing helpful comments