REVISTA

PAULISTA

DE

PEDIATRIA

www.rpped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Acute

effect

of

vigorous

aerobic

exercise

on

the

inhibitory

control

in

adolescents

Rodrigo

Alberto

Vieira

Browne

a,∗,

Eduardo

Caldas

Costa

a,

Marcelo

Magalhães

Sales

b,

André

Igor

Fonteles

a,

José

Fernando

Vila

Nova

de

Moraes

c,

Jônatas

de

Franc

¸a

Barros

aaUniversidadeFederaldoRioGrandedoNorte(UFRN),Natal,RN,Brazil bUniversidadeCatólicadeBrasília(UCB),Brasília,DF,Brazil

cUniversidadeFederaldoValedoSãoFrancisco(Univasf),Petrolina,PE,Brazil

Received4April2015;accepted9August2015 Availableonline3February2016

KEYWORDS

Sports;

Physicaleducation andtraining; Cognition;

Executivefunction; Puberty

Abstract

Objective: Toassesstheacuteeffectofvigorousaerobicexerciseontheinhibitorycontrolin adolescents.

Methods: Controlled, randomized study with crossover design. Twenty pubertal individuals underwenttwo30-minutesessions:(1)aerobicexercisesessionperformedbetween65%and 75%ofheartratereserve,dividedinto5minofwarm-up,20minatthetargetintensityand5min ofcooldown;and(2)controlsessionwatchingacartoon.Beforeandafterthesessions,the computerizedStrooptest---TestinpacsTMwasappliedtoevaluatetheinhibitorycontrol.Reaction

time(ms)anderrors(n)wererecorded.

Results: Thecontrolsessionreactiontimeshowednosignificantdifference.Ontheotherhand, thereactiontimeoftheexercisesessiondecreasedaftertheintervention(p<0.001).The num-beroferrorsmadeattheexercisesessionwerelowerthaninthecontrolsession(p=0.011). Additionally,therewasapositiveassociationbetweenreactiontime()oftheexercisesession andage(r2=0.404,p=0.003).

Conclusions: Vigorousaerobicexerciseseemstopromoteacuteimprovementintheinhibitory controlinadolescents.Theeffectofexerciseontheinhibitorycontrolperformancewas asso-ciatedwithage,showingthatitwasreducedatolderageranges.

©2015SociedadedePediatriadeSãoPaulo.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:rodrigodenatal@gmail.com(R.A.V.Browne). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rppede.2016.01.005

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Esporte;

Educac¸ãofísicae treinamento; Cognic¸ão;

Func¸ãoexecutiva; Puberdade

Efeitoagudodoexercícioaeróbiovigorososobreocontroleinibitórioem adolescentes

Resumo

Objetivo: Verificaroefeitoagudodoexercícioaeróbiovigorososobreocontroleinibitórioem adolescentes.

Métodos: Estudocontroladoerandomizadocomdelineamentocruzado.Vintepúberesforam submetidosaduassessõesde30minutos:1)sessãoexercícioaeróbiofeitoentre65---75%da fre-quênciacardíacadereserva,comcincominutosparaaquecimento,20minutosnaintensidade alvoecincominutosdevoltaàcalma;e2)sessãocontroleassistindoadesenhoanimado. Pre-viamenteeapósassessões,otestedeStroopcomputadorizado(Testinpacs®)foiaplicadopara

avaliarocontroleinibitório.Otempodereac¸ão(ms)eoserroscometidos(n)foramregistrados.

Resultados: Otempodereac¸ãodasessãocontrolenãoapresentoudiferenc¸asignificativa.Por outro lado,o tempo dereac¸ãoda sessãoexercício diminuiu apósaintervenc¸ão(p<0,001). Oserroscometidosnasessãoexercícioforammenoresdoquenasessãocontrole(p=0,011). Adicionalmente,houveassociac¸ãopositivadotempodereac¸ão()dasessãoexercíciocoma idade(r2=0,404;p=0,003).

Conclusões: Oexercícioaeróbiovigorosoparecepromovermelhoriaagudanocontroleinibitório emadolescentes.Oefeitodoexercíciosobreodesempenhodocontroleinibitóriofoiassociado àidadeedemonstrouserreduzidoemfaixasetáriasmaisaltas.

©2015SociedadedePediatriadeSãoPaulo.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Esteéumartigo OpenAccesssobalicençaCCBY(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.pt).

Introduction

Executivecontrol(or executivefunctions) referstohigher cognitiveprocessesthatmanagethecontrolofother,more basic cognitive functions and direct the ideal behavior toachievegoal-orientedbehaviors.1 Ingeneral,executive

control is subdivided into inhibitory control (IC),working

memoryandcognitiveflexibility.1The ICisconsidered the

maindomainofexecutivecontrolandadeterminantof

aca-demic success, asit controls attention, behavior, thought

and/or emotion to override a strong internal

predisposi-tion or external attraction and adapt itself to conflicting

situations.1

School activities constitute a model of environmental

requestregardingtheautonomyandcontrolofattentional,

organizationandplanningfunctions,whichrequiresan

effi-cient performance of the IC.2 Evidence suggests that the

development of IC skills during childhood promotes an

increasedcapacity for success in the development of the

theoryofmind---facilitatesthinkingandlearning3---aswell

asa betterperformance in counterfactual4 reasoningand

strategic5 tasks. The ICalso has been strongly associated

withintelligencelevel6andschoolperformance.7

Bothfrontal regions,cortical andsubcortical,subserve

theexecutive control.8 The prefrontalcortex(PFC) is the

onethat playsa keyrole.8Increasedbrain activityof the

PFCwasobservedduringthetaskmakingoftheIC(Stroop

Test).9 The PFC comprises from a quarter to a third of

the cerebral cortex and contains rich reciprocal

connec-tionswithitself,withother corticalareasandsubcortical

and limbic regions.10 The performance of executive

con-troldevelopsfromearlychildhood,throughoutadolescence,

to adulthood,11 concurrently with the neuroanatomical,

functional12 andbrainbloodperfusion13 changes,including

thePFCregions.

Physical exercise has been considered an important

environmentalfactorfor neurodevelopment,14 topromote

cognitiveand brain health,15 aswell as for a better

per-formance of the executive and school control.7 A single

sessionofaerobicexerciseshasbeenshowntoimprovethe

efficiencyof theIC inchildren16 and young adults,17---19 in

contrasttowhatwasobservedinadolescentsafter20minof

aerobicexerciseperformedonacycleergometerat60%of

maximumheartrate(HRmax).20Cognitiveperformanceafter

acuteexerciseseemstobedependentontheintensity.21In

themeta-analysisofChangetal.,21thestudiesthatusedlow

intensity,<50%ofHRmax,hadanegativeeffectoncognitive

performance.Ontheotherhand,instudieswithintensities

>64%ofHRmax,theeffectswerepositive.

Apossiblephysiologicalhypothesisthatmayexplainthe

acuteeffectofexerciseintensityontheICisincreased

cere-bralbloodflowgeneratedbyexerciseeffort,whichcanhave

an impactonpost-exercise cognitiveperformance.17---19 In

thestudy byYanagisawaetal.,19 therewasan increasein

cerebralbloodflow(↑oxygenatedhemoglobin)inthePFC

andimprovedperformanceintheStrooptestinyoungadults

after 10min of aerobic exercise at 50% of the peak

oxy-genconsumption(peakVO2).Thesameeffectwasobserved

insimilarexperimentscarriedoutwithyoungadultsafter

20minofexercisebetween60%and70%ofHRmax18andafter

15minofexerciseat40%ofmaximumload,respectively,17

andinchildrenafter20minofaerobicexercisebetween65%

and75%ofHRmax.16

However, there is still a gap of knowledge whether

a vigorous aerobic exercise session can improve the IC

in adolescents, which may be important, as their PFC is

still undergoing the maturation phase. It is a period of

structural,functional12andbloodperfusion13changes.The

studyhypothesisisthattheuseofaprescriptionofaerobic

confoundingfactorsassociatedwithcognitiveimprovement

byacuteexercise,mayfavorthephysiologicalbrain

mecha-nismsinducedbyexerciseandinfluencethepost-exerciseIC

performance,asshowninchildren16 andyoungadults.17---19

Therefore,theaimofthisstudywastoinvestigatetheacute

effectofvigorousaerobicexerciseontheICinadolescents.

Theintensity andvolumeof theexercisewere prescribed

accordingtovigorousexerciserecommendationsfor

adoles-centsfromtheWorldHealthOrganization22andaccordingto

thebesteffectobtainedbymeta-analysisofChangetal.21

Other control factors, such as time of the exercise and

thetimeintervaltoapplythepost-exercisecognitivetest,

werealsosupportedbythemeta-analysisofChangetal.21

Method

This was a controlled, randomized study with crossover design,carried out onthe seaside,in the municipality of Icapuí(CE). The acute effectof theexercise prescription protocolwastestedintwosessions,withaminimumof48h ofinterval,namely: (1) vigorousaerobicexercisesession; and(2)controlsessionwatchinganage-appropriatecartoon. Halfoftheparticipants,randomly,firstreceivedthe exper-imental treatment and then the control, while the other half firstreceivedthe controland after theexperimental treatment.Finally, the assessmentof ICperformance was performedbeforeandafterthesessions.

Sample size was calculatedusing the statistical power (1−ˇ), with analysis of variance being used in the main study outcome (Split Plot ANOVA), with an effect size of

f=0.333(consideredmiddle-sized)andanalphaof0.05.The statisticalpowergiventothissample,regardlessofgender, was80%(G*Power®,version3.1.9.2;Institutefor

Experimen-talPsychologyinDusseldorf,Germany).

Twentyadolescents(Table1)ofbothgendersand

physi-callyactive,between10and16yearsofage,wererandomly

enrolledfrompublicelementaryschoolsinthemunicipality

of Icapuí. Posters about the study were fixed in the

bul-letinboardsofschools torecruitvolunteers andalecture

wasgivenat apredeterminedtimeandlocationfor those

interested.Inclusioncriteriawere:(i)availabilitytoattend

theinitialassessmentandthecontrolandexercisesessions

inthe morning;(ii)to bephysically active,that is,tobe

enrolledandregularlypracticephysicalexercises(≥1year

and≥2×/week,respectively)inextracurricularsports

pro-gramstaking placein theschools in the shift opposite to

theschoolshift;(iii)meetthecriteriaofthephysical

activ-ityreadinessquestionnaire(PAR-Q);(iv)tobeclassifiedas

‘‘pubertal’’(Tanner stages 2---4)23;and (v) have no

physi-calor intellectual disabilitiesand/orclinical, neuromotor,

psychologicaland/orcognitivecontraindications.

The researchproject wasapprovedbytheInstitutional

Review Board of Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do

Norte (Protocol No. 876286/2014 CEP/UFRN), consistent

withtheDeclarationofHelsinkiandResolutionN.466/2012

oftheNationalHealthCouncil.Allselectedadolescentshad

theinformedconsentandassentform,PAR-Qand

medical-historyquestionnairefilledoutanddulysigned.

Bodyweightandheightweremeasuredbyamechanical

scale(G-Tech®)andastadiometerfixedtothewall(Sanny®),

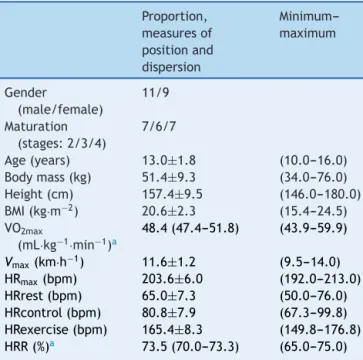

Table 1 Characterization of the sample of adoles-cents (n=20). Data expressed as mean and standard deviationfor parametricvariables,medianand95% confi-dence intervals for nonparametric variables and range (minimum---maximum).

Proportion, measuresof positionand dispersion

Minimum---maximum

Gender

(male/female)

11/9

Maturation (stages:2/3/4)

7/6/7

Age(years) 13.0±1.8 (10.0---16.0) Bodymass(kg) 51.4±9.3 (34.0---76.0) Height(cm) 157.4±9.5 (146.0---180.0) BMI(kg·m−2) 20.6±2.3 (15.4---24.5)

VO2max

(mL·kg−1·min−1)a

48.4(47.4---51.8) (43.9---59.9)

Vmax(km·h−1) 11.6±1.2 (9.5---14.0)

HRmax(bpm) 203.6±6.0 (192.0---213.0)

HRrest(bpm) 65.0±7.3 (50.0---76.0)

HRcontrol(bpm) 80.8±7.9 (67.3---99.8) HRexercise(bpm) 165.4±8.3 (149.8---176.8) HRR(%)a 73.5(70.0---73.3) (65.0---75.0)

HRcontrol,meanheartrateofthecontrolsession;HRexercise, meanheartrateoftheexercisesession;HRmax,maximumheart

rate; HRR, percentage of heartrate reserve at theexercise session;HRrest,restingheartrate;BMI,bodymassindex;Vmax,

maximumvelocity;VO2max,maximaloxygenuptake. a Nonparametricvariable.

respectively. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated throughtheformula:[BMI=bodymass(kg)×height(m)2].24

Sexual maturation wasevaluated by Tanner stage23 to

differentiatepre-pubertalindividualsfrompubertalones,as

inclusioncriteriainthestudy.25TheTablesconsistofimages

withcaptionsthatcharacterize thegenitalsandbodyhair

forboysandbreastsandbodyhairforgirls.Themethodand

itspurposewere individually explainedand,through

self-assessment,theadolescentspointedoutinaprivateform

whichimagestheirconditionmostresembled.Thepubertal

stagewasratedonascalefrom1to5,namely:

1=prepuber-tal;2---4=pubertal;and5=post-pubertal.

The maximal multistage 20-m shuttle run test26 was

appliedtoobtaintheHRmax.Thistestwasperformedinan

indoorsportscourt(between7and10h)andconsistsof

rac-ingbackandforthatadistanceof20meters.Thevelocity

wascontrolledbyametronomeaudio.The initialvelocity

was8.5km/h,followedbyincrementsof0.5km/hatevery

one-minutestage.Heartrate(HR)wasmonitored

through-outthe test bya heartrate monitor(Beurer®,Germany).

HRmaxwasconsideredasthehighestHRattainedduringthe

test,validonlywhensignsofintenseeffortwereobserved.27

Subjectswereverballymotivatedtoendureaslongas

possi-ble.Thetestwascontinueduntilvoluntaryexhaustion.The

maximumvelocity(Vmax)wasusedtoestimatethemaximum

The resting heartrate(HRrest)wasmeasured withthe

subjectatrestinthesupinepositionfor5min.Itwas

consid-eredthelowestHRobtained.TheHRreserve(HRR)wasthe

differencebetweenHRmaxandHRrest(HRR=HRmax−HRrest).

To determine the HR-targetfor exercise prescription, we

usedthe percentage of HRR. The percentage of HRR was

added to HRrest to determine the HR-targetin exercise:

HR-target=(%intensity(indecimal)×HRR)+HRrest.24

Onadifferentdayoftheexercisesession,subjectswere

familiarizedwithexerciseintensityandhowtostayonthe

HR-target.Attheexercisesession,awarm-upof5minwas

performed throughwalking,followedby 20min ofrunning

atvigorousintensity(65---75% ofHRR)and5minof cooling

down,totaling30min.TheHRwasmonitoredthroughoutthe

sessionbyaheartratemonitor(Beurer®,Germany),sothat

theparticipantremainedintheHR-target.Inadditiontothe

individualcontroloftheparticipantsthemselves,according

tothe guidelines givenduring the familiarization session,

theHRwasmonitoredandrecordedevery3min. If

neces-sary,verbaldirectionswereprovidedtoadjusttheintensity.

Theexercisewasperformedonthebeachsand(wetsand,

lowtideandflatterrain),withthesubjectsbarefoot.The

sessionswerecarriedoutbetween7and10AMwitha

tem-peratureandairhumiditybetween26---30◦Cand52%---74%,

respectively.

Duringthecontrolsession,thesubjectsremainedseated

for 30min in the school computer lab watching an

age-appropriate cartoon (Kung Fu Panda). HR was monitored

andrecordedevery3minbyaheartratemonitor(Beurer®,

Germany).

TheICperformancewasevaluatedbythecomputerized

Strooptest (Testinpacs®),withtheaid ofadesktopand a

14-inchmonitor.29Recallingwasdonebeforeeverysession.

Thetestwasappliedbeforeandafter10minofeachsession.

The instrument hasthree Phases, the first twocongruent

and the last one incongruent. The index and middle

fin-gersoftheright handremainedontheleft(←)andright

(→)arrowkeys,respectively,whichwereactivated

accord-ingtoeachstimulus.Instage1,rectanglesingreen,blue,

blackandredwereindividuallyshowninthecenterofthe

monitor.Inthelowercornersofthemonitor,answers

corre-spondingornottotherectanglecolorwereexhibiteduntil

the participantresponded tothe attemptby pressing the

keys←or →.Instage2,bothstimuliandresponseswere

shownaswords,alwaysinwhitecolor.Theresponsewas

con-sideredcorrectwhenthestimulusandresponsecoincided.

Finally,instage3, thewordofoneofthefourcolorswas

exhibitedinincompatiblecolor.Thesubjectwasinstructed

to press the key corresponding to the color of the word

andinhibittheresponsetothewordidentity.Atallstages

thestimuliwerepresentedautomaticallyandrandomly,12

attemptsperstage.Thereactiontime(RT)inmilliseconds

(ms)andthenumberoferrors(n)madeateachstagewere

recorded.

TheStatisticalprocedureswereperformedwithSPSSfor

Win/v.19.0(StatisticalPackageforSocialSciences,Chicago,

IL,USA)andG*Powerversion3.1.9.2(Institutefor

Experi-mentalPsychologyinDusseldorf,Germany).Thenormality

and homogeneity of data variance were tested by the

Shapiro---WilkstestandLevenetest,respectively.

Paramet-ricvariableswereexpressedasmeanandstandarddeviation

orstandarderror,andthenonparametricasmeanormedian

andtheirrespective95%confidenceintervals.Thelevelof

significancewassetatp<0.05.

ThereliabilityoftheStrooptest(RT)betweenbaseline

values (pre×pre) was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha (˛).

The ttest for independent sampleswasused tocompare

thebaselineRT betweenthe conditions(pre×pre).

Split-PlotAnova,adjustedforchronologicalage,wasappliedto

the comparison of intra- and inter-conditions of RT. The

hypothesisof sphericitywasverifiedby Mauchlytestand,

whenviolated,thedegreesoffreedomarecorrectedbythe

Greenhouse---Geisserestimates.Theeffectsizeofthe

vari-ance was calculated by the eta squared (2). The paired

t-test was applied to each group separately, in order to

locatethedifferences observedintheSplit-Plot. Thesize

effectwascalculatedbytheequation:

r=

t2

t2+gl

Quade’sNon-parametricAncova,adjustedby

chronolog-icalage,wasappliedtocomparethedeltas(=pre---post)

of the amount of errors made between the conditions

(control×exercise).Aftertheassessmentofnormalityand

homogeneity of the variance residues, the simple linear

regression(r2)andPearson’scorrelationcoefficient(r)were

appliedtoassociatetheRTdelta(=post-pre)ofthe

incon-gruentPhase3withchronologicalage.

Results

Among the adolescents selected for the study, it was observedthat65%had faileda schoolyear.Table1 shows

the variables of the sample characteristics, sexual

matu-ration,anthropometricmeasurements,estimatedvariables

andthoseobtainedbythemaximalmultistage20-mshuttle

runtest(VO2max,VmaxandHRmax)andmeanHRofthe

con-trolandexercisesessions.Furthermore,theHRR%meanat

whichtheadolescentsremainedduringtheexercisesession

wasdepicted.

TheRTofthestages1,2and3oftheStrooptestbetween

baseline values (pre×pre) had a reliability of ˛=0.502;

˛=0.493; ˛=0.752; respectively. There was no difference

between the baseline values of RT (pre×pre) in stage 1

(t[38]=−0.567;p=0.574),instage2(t[38]=−0.740;p=0.464)

andstage3(t[38]=−0.665;p=0.510).

Inthe congruentphase1ofthe Strooptest, the

inter-action time×conditions, adjusted for age did not differ

statistically,F(1,37)=1.98;p=0.168;2=0.051.Therewasno

differencebetweentheconditions,F(1,37)=0.00;p=0.982;

2=0.000. There was also no significant effect on time,

F(1,37)=2.79;p=0.103;2=0.070(Fig.1A).

The second congruent phase, stage 2, did not show

statistical difference in the time×conditions interaction,

adjusted for age, F(1,37)=2.28; p=0.139; 2=0.058. There

was no difference between the conditions, F(1,37)=0.00;

p=0.955; 2=0.000. There was a significant effect on

time,F(1,37)=4.66; p=0.037; 2=0.112. The paired t test

(pre×post) showedthat thecontrol conditiondid not

dif-fer,t(19)=2.05;p=0.055;r=0.43;buttheexercisecondition

In theincongruent phase,stage3, therewasan

inter-action time×conditions that was statistically significant,

adjustedbyage,F(1,37)=12.49;p=0.001; 2=0.252.There

wasnodifferencebetweentheconditions,F(1,37)=0.134;

p=0.716; 2=0.004. There was a significant effect on

time,F(1,37)=5.64; p=0.023; 2=0.132. The paired t test

(pre×post) showed that the control condition did not

differ,t(19)=0.64;p=0.532;r=0.15;buttheexercise

condi-tion significantly differed, t(19)=4.94; p<0.001; r=0.75

(Fig. 1C). The errors that were made, adjusted by age,

didnotdifferbetweenthecontrol×exerciseconditionsin

phase 1 [F(1,38)=0.105; p=0.748 (Fig. 2A)] and phase 2

[F(1,38)=0.045; p=0.834 (Fig.2B)], but phase3 showeda

significantdifference[F(1,38)=7.162;p=0.011(Fig.2C)].

Assecondaryanalysis,weverifiedapositiveassociation

(p=0.003) of RT of incongruent phase 3 of the exercise

–50

Control

Exercise

A

B

–75–100

–125

Dif. [post-pre] R

T

(ms)

Dif. [post-pre] R

T

(ms)

Dif. [post-pre] R

T

(ms)

C

*

*

–150–175

–200

–75

–100

–100 –50 0 –125

–150

–150 –175

–200

–200

–250 –225

Figure1 Acuteeffect ofvigorous aerobic exercise onthe reaction time (RT) in Phases 1 (A), 2 (B) and 3 (C) of thecomputerized Stroop Test (Testinpacs®). Split-Plot Anova

adjustedfor chronological agewas applied inthe intra- and inter-comparisons between conditions (2×2). The delta data (=post---pre)areshownasmeanandstandarderror.*p<0.001; pre×post.

conditionwithchronologicalage(Fig.3).Ontheotherhand,

there was no association of RT of phase 3 of the

con-trol conditionwith chronological age (r2=0.021;p=0.545).

Samplesizecalculation,afterwards,oftheanalysisof

asso-ciationwascarriedoutwithanalphaof0.05,sample size

of20subjectsandacoefficientofcorrelationof0.635.The

statisticalpowergivenintheanalysiswas88%.

Control

Exercise 0.6

0.4

0.2

–0.2

–0.4

–0.6 0.0

Dif. [post-pre] error (n)

Dif. [post-pre] error (n)

Dif. [post-pre] error (n)

A

0.6

0.4

0.2

–0.2

–0.4

–0.6

1.2

0.8

0.4

–0.4

–0.8

–1.2 0.0 0.0

B

C

*

Figure 2 Acute effectof vigorous aerobic exercise on the errorsmadeinPhases1(A),2(B)and3(C)ofthecomputerized StroopTest(Testinpacs®).Non-parametricAncovaadjustedfor

9 –800 –700 –600 –500 –400 –300 400

r=0.635, p=0.001 r2=0.404, p=0.003

300

–200 200

–100 100 0

10 11 12 13

Chronological age (years)

Dif. [post-pre] R

T

(ms)

14 15 16 17

Figure3 Linearregression(r2)andPearson’scoefficient

cor-relation(r)betweenthedelta(=post---pre)oftheincongruent reactiontime(RT)ofStrooptestPhase3oftheexercisesession withchronologicalage.

Discussion

Thepresentstudyinvestigatedtheacuteeffectofvigorous aerobicexerciseontheICinadolescents.Themainfindings suggestthatvigorousaerobicexerciseacutelyenhancesthe performanceoftheIC,astherewasanimprovementonthe Stroopinterference(inhibitionofresponse)observedbythe decreaseintheRToftheincongruentphase(Fig.1C),with

afocaleffectconsideredlarge(r=0.75),accompaniedbya

smallernumberoferrorsmade(Fig.2C).Theseresultscan

beveryimportanttoelucidatetheinfluenceofexerciseon

theICefficiencyand,therefore, contributetotheprocess

oflearningintheschoolenvironment.2

TheinfluencethatexercisepromotedonICperformance

isinaccordancewiththeevidencefromstudiescarriedout

withchildren16 and young healthy adults.17---19 As exercise

intensity is an important factor to enhance post-exercise

cognitiveperformance,21thisstudyadoptedavigorous

exer-ciseprotocol,whichinadditiontobeingrecommendedby

theWorldHealthOrganizationforadolescents,22 wouldbe

adequatetoinducethephysiologicalmechanisms

responsi-bleforfavoringthecognitiveperformance.21Forinstance,

inameta-analysis,theintensityoftheexercisehada

sig-nificant influence sothat the prescribedexercise <50%of

HRmax resulted ina significant negativeeffect (d=−0.113)

oncognitiveperformance,butwhenprescribedat64---76%

or77---93%oftheHRmax,theresultswerepositive,withan

effectof0.202and0.268,respectively.21

Inadditiontoexerciseintensity,othercontrolledfactors

mayhavebeenequallyimportantfortheexercisetofavor

thecognitivebenefits,includingthevolumeandtimeofthe

exercise,aswell asthetimeintervalfor the

implementa-tionof thepost-exercise cognitivetest. Inthissense, the

exercise volume was also adjusted according to the

rec-ommendations of the World Health Organization22 on the

volumeof vigorousexercisefor adolescentsand,asother

studies have shown, resulting in cognitive benefits after

20minofaerobicexerciseinchildren16andyoungadults.18

Thetimeintervaltoapplythecognitivetestwasdefined

between 10 and 20min post-exercise, according to the

best effect size obtained by the meta-analysis of Chang

et al.,21 in which this control factor was considered a

primary moderator of cognitive benefits. For instance,

Changetal.21 categorizedthetimetoapplythecognitive

testsin0---10min; 11---20min or>20minaftertheexercise

and obtained an effect size of −0.060, 0.262 and 0.171

respectively.Thatis,thepost-exerciseapplicationtime

sig-nificantly influenced the effect size. The positive effects

wereobservedonlyafter11minpost-exercise.

The statistical findings of the meta-analysis by Chang

et al.21 on the time interval for the application of the

post-exercise cognitive tests is consistent with

reticular-activating hypofrontalitymodel proposed by Dietrich and

Audiffren,30 whichsuggests adecrease inbrain activation

in regions not directly associated with physical exercise

(i.e.,PFC)tosupplydirectlyassociatedregions.

Corroborat-ingthisunderstanding,thestudy byWangetal.31 showed

adeclinein ICperformance duringvigorousaerobic

exer-cise,whichcouldinfluenceICefficiencyimmediatelyafter

theexercise.Thus,thesestudiesandthistheoreticalmodel

agreewiththeneed for atimeinterval betweenthe end

of the exercise and the beginning of a cognitive task for

homeostasistooccuratthebrainlevel,morespecificallyin

thePFC.

Our data show that aerobic exercise seems to have

been a tool capable of acutely influencing the

physiolog-icalmechanisms responsible for favoring IC performance.

The mechanisms arestill somewhat controversial and

lit-tle explored, but the main physiological hypothesis that

couldexplainthese effects refer tothe increase in

cere-bralbloodflow,whichcaninfluencecognitiveperformance

afterexercise.17---19Forinstance,Yanagisawaetal.,19using

near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), evaluated the cortical

activation during Stroop test performed before and after

10minofaerobicexerciseat50%of peakVO2 in20young

adults.Infact,therewasincreasedbloodflowfromthe

lat-eralPFCinbothhemispheres(↑oxygenatedhemoglobin)due

toStroopinterference(incongruence).Incontrast,this

acti-vationwassignificantlyincreasedintheleftdorsolateralPFC

andcoincidedwithimprovedperformanceonthecognitive

task(↓RT).

As secondary analysis,we demonstratedan association

ofRToftheincongruentphase(stage3)oftheexercise

condition withchronological age (r2=0.404) (Fig. 3). That

is,post-exerciseICimprovementwasreducedinolderage

groups. The regression analysis shows that 40.4% of the

variability found in post-exercise IC performance can be

explainedby chronological age.In this sense,due to

evi-dencethatoneofthephysiologicalmechanismsresponsible

forthe improvementof post-exercise ICcanbeincreased

cerebralbloodflow,17---19thevariabilityincanberelated

tothematurationofthecerebralperfusionmechanism

dur-ingadolescence.13Notably,Satterthwaiteetal.13 observed

asignificantimpactofpubertyoncerebralperfusion

devel-opment.The authorsevaluatedthecerebralblood flowof

922youngindividualsagedeightto22yearsandfoundthat,

duringadolescence, the brainflow throughout the cortex

decreasesconsiderably,includinginthePFC.The cerebral

blood flow of the middle gray matter undergoes a sharp

declineinlatechildhoodandearlyadolescenceuntilabout

16---18years,followedbyaslightincreaseduringearly

adult-hood.

Althoughoriginalthisstudyhaslimitations,oneofwhich

with a neuroimaging technique, which could promote

greatersupport inconfirming the evidence.Nevertheless,

severalstudieshaveconfirmedthatacuteaerobicexercise

canimproveICatthemacroneurallevel,asitpromotes

sig-nificantimpactonPFCbrainactivityduringICtaskmaking

after10---20minofaerobicexerciseinchildren16andyoung

adults.17,18

Theuseofsexualmaturationself-assessmentprocedure

todistinguish thepre-pubertyandpubertyasaninclusion

criterion is also considered a limiting factor. The

evalu-ation by visual inspection by a trained evaluator is the

most reliable indirect method.25 However, it can be

jus-tifiedthat the sample consisted mostly of adolescents at

the pubertal stage.25 In the study by Rasmussen et al.,25

carried out with 898 children and adolescents, the

self-assessmentofsexualmaturationshowedtobeasufficiently

accuratetechniquetosimplydifferentiatesimplesbetween

prepubertalandpubertalstages.Breaststagewascorrectly

assessed by 44.9% of the girls (=0.28; r=0.74; p<0.001)

and the genital stage by 54.7% of boys (=0.33; r=0.61;

p<0.001).Pubichairwascorrectlyassessedby66.8%ofgirls

(=0.55;r=0.80;p<0.001)and66.1%ofboys(=0.46;r=0.70;

p<0.001).

It is noteworthy that this study is a pioneer in

inves-tigating the acute effects of vigorous aerobic exercise

on IC in adolescents and contributes to elucidate the

effectsof aerobicexercisein this population,which have

an executive control performance11 and brain functions,

structures12 and perfusion13 still undergoing maturation.

Additionally, thestudy hadthe premiseof controllingthe

possiblevariables,suchastheequalnumberofadolescents

of both genders, obtaining the HRmax through a maximal

effort progressive running test, the intensity and volume

ofthe experimentalcondition exercise,the timeof

phys-ical exercise, the use of a computerized cognitive test

that records the performance in milliseconds, and the

time for application of the post-exercise cognitive test.

Therefore,the study mayprovide subsidies for the

appli-cability of this aerobic exercise protocol in the school

context.32

Inconclusion, avigorousaerobicsessionperformed for

20min seems to promote improvement in IC capacity in

adolescents.Additionally, the effectof exerciseontheIC

performance was associated with chronological age. This

demonstratesthat the benefits of exercise were reduced

in older age groups. As practical implications, the

find-ings of this study contribute to justify the inclusion of

physical education classes during school hours, that is,

among the other school subjects (i.e., Portuguese and

mathematics), as well as the inclusion of a physically

activeinterval/recess,as20minof vigorousaerobic

exer-cise can favor the IC efficiency and therefore contribute

to learning improvement after 10min of post-exercise

recovery.

Funding

Master’s Degree Scholarship granted by Programa de DemandaSocial (DS)of Coordenac¸ão de Aperfeic¸oamento dePessoaldeNívelSuperior(Capes)tothefirstauthor(RAV Browne).

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

ToProf.AntônioJosédaCosta,whoprovidedapprovaland welcomefor theresearchtobe carriedoutlocally at the educationalinstitutionofwhichheistheprincipal,Professor JoanaMarquesBezerraElementarySchool,inthe municipal-ityofIcapuí(CE).

References

1.Diamond A. Executive functions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2013;64:135---68.

2.CypelS. O papel dasfunc¸õesexecutivas nostranstornos da aprendizagem. In: Rotta N, Ohlweiler L, Riesgo R, editors. Transtornosdaaprendizagem:abordagemneurobiológica emul-tidisciplinar.PortoAlegre:Artmed;2006.p.375---87.

3.Benson JE, Sabbagh MA, Carlson SM, Zelazo PD. Individ-ualdifferencesinexecutivefunctioningpredictpreschoolers’ improvement from theory-of-mind training. Dev Psychol. 2013;49:1615---27.

4.BeckSR,RiggsKJ,GorniakSL.Relatingdevelopmentsin chil-dren’scounterfactualthinkingandexecutivefunctions.Think Reason.2009;15:337---54.

5.ApperlyIA,CarrollDJ.Howdosymbolsaffect3-to4-year-olds’ executivefunction?Evidencefromareverse-contingencytask. DevSci.2009;12:1070---82.

6.Lee HW, Lo YH, Li KH, SungWS, JuanCH. Therelationship between thedevelopmentof responseinhibition and intelli-genceinpreschoolchildren.FrontPsychol.2015;6:802.

7.VanderNietAG,HartmanE,SmithJ,VisscherC.Modeling rela-tionshipsbetweenphysicalfitness,executivefunctioning,and academicachievementinprimaryschoolchildren.PsycholSport Exerc.2014;15:319---25.

8.Badre D. Cognitive control, hierarchy, and the rostro-caudal organization of the frontal lobes. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:193---200.

9.Zhang L, Sun J, Sun B, Luo Q, Gong H. Studying hemi-sphericlateralizationduringaStrooptaskthroughnear-infrared spectroscopy-basedconnectivity.JBiomedOpt.2014;19:57012.

10.Olson EA, LucianaM. The development ofprefrontal cortex functions inadolescence: Theoretical models and a possible dissociationofdorsalversusventralsubregions.In:NelsonCA, LucianaM,editors.Handbookofdevelopmentalcognitive neu-roscience.2nded.Cambridge:MITPress;2008.p.575---90.

11.RomineCB,ReynoldsCR.Amodelofthedevelopmentoffrontal lobefunctioning:findingsfromameta-analysis.Appl Neuropsy-chol.2005;12:190---201.

12.Blakemore SJ. Imaging brain development: the adolescent brain.Neuroimage.2012;61:397---406.

13.Satterthwaite TD, Shinohara RT, Wolf DH, et al. Impact of pubertyontheevolutionofcerebralperfusionduring adoles-cence.ProcNatlAcadSciUSA.2014;111:8643---8.

14.HertingMM,ColbyJB,SowellER,NagelBJ.Whitematter con-nectivity and aerobic fitness in male adolescents. Dev Cogn Neurosci.2014;7:65---75.

15.KhanNA,HillmanCH.Therelationofchildhoodphysicalactivity andaerobicfitnesstobrainfunctionand cognition:areview. PediatrExercSci.2014;26:138---46.

performance in children with ADHD. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2013;162:543---51.

17.EndoK,MatsukawaK,LiangN,etal.Dynamicexerciseimproves cognitivefunctioninassociationwithincreasedprefrontal oxy-genation.JPhysiolSci.2013;63:287---98.

18.LiL, MenWW,ChangYK,Fan MX,JiL, WeiGX. Acute aero-bicexerciseincreasescorticalactivityduringworkingmemory: afunctionalMRIstudyinfemalecollegestudents.PLoSOne. 2014;9:e99222.

19.YanagisawaH,DanI,TsuzukiD,etal.Acutemoderate exer-cise elicits increased dorsolateral prefrontal activation and improvescognitiveperformancewithStrooptest.Neuroimage. 2010;50:1702---10.

20.StrothS,KubeschS,DieterleK,RuchsowM,HeimR,KieferM. Physicalfitness,butnotacuteexercisemodulatesevent-related potentialindicesforexecutivecontrolinhealthyadolescents. BrainRes.2009;1269:114---24.

21.ChangYK,LabbanJD,GapinJI,EtnierJL.Theeffectsofacute exerciseoncognitiveperformance:ameta-analysis.BrainRes. 2012;1453:87---101.

22.WorldHealthOrganization.Globalrecommendationson physi-calactivityforhealth.Geneva:WHO;2010.

23.TannerJ.Growthatadolescencewithageneralconsideration oftheeffects ofhereditary and environmental factorsupon growthandmaturationfrombirthtomaturity.2nded.Oxford: BlackwellScientificPublications;1962.

24.HeywardVH.Avaliac¸ãofísicaeprescric¸ãodeexercício:técnicas avanc¸adas.6thed.PortoAlegre:Artmed;2013.

25.Rasmussen AR, Wohlfahrt-Veje C, Renzy-Martin KT, et al. Validityofself-assessmentofpubertalmaturation.Pediatrics. 2015;135:86---93.

26.LégerLA,LambertJ.Amaximalmultistage20-mshuttlerun test to predict VO2 max. EurJ Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1982;49:1---12.

27.ArmstrongN, Welsman JR. Assessmentand interpretationof aerobicfitnessinchildrenandadolescents.ExercSportSciRev. 1994;22:435---76.

28.LégerLA, MercierD, GadouryC,LambertJ. The multistage 20 metre shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. J Sports Sci. 1988;6:93---101.

29.Córdova C, Karnikowski M, Pandossio J, Nóbrega O. Caracterizac¸ão de respostas comportamentais para o teste de Stroop computadorizado-Testinpacs. Neurociencias. 2008;4:75---9.

30.Dietrich A,AudiffrenM.Thereticular-activating hypofrontal-ity (RAH) model of acute exercise. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1305---25.

31.WangCC,ChuCH,ChuIH,ChanKH,ChangYK.Executive func-tionduringacuteexercise:theroleofexerciseintensity.JSport ExercPsychol.2013;35:358---67.