AbstrAct

Introduction. The aim of the study was to evaluate the frequency and severity of a sense of uncertainty con-cerning important determinants of human existence in selected groups of young women in Poland and the Czech Republic, when they found themselves to be at the right age to have children. Material and methods. Data were obtained based on a self developed questionnaire. The study involved 42 nursing students in the second year of studies in Poland and 51 nursing students in the Czech Republic. The average age in these two groups was 21.7 and 22.8 years respectively The results were analyzed sta-tistically using the chi-square test. Results. Polish young women in comparison to Czech women are more often afraid of considerable nuisance problems with future work, unsatisfactory relationships with future partners, and a sense of forthcoming impending dangers. Conclu-sions. The results suggest considerable uncertainty with regard to important spheres of human existence among young people. In the light of similar observations made by authors from countries of different economic standard, the insecurity is only one affecting factor among others. The results indicate the advisability of undertaking re-search on different approved models of the family.

Key words: decline of fertility, birth rate, feeling of economic uncertainty, unemployment, sense of security, model of family

strEszczENiE

Wstęp. Celem pracy była ocena częstości i nasilenia poczucia niepewności dotyczącej ważnych uwarunkowań egzystencjalnych w wybranych grupach młodych kobiet w Polsce i Czechach, które są w wieku poprzedzającym podjęciem decyzji o posiadaniu dzieci. Materiał i metody. Dane uzyskano poprzez badanie sondażowe przy pomocy własnego kwestionariusza ankietowego. Badaniu poddano 42 studentki pielęgniarstwa II roku studiów w Polsce i 51 studentek pielęgniarstwa w Czechach. Średni wiek w tych dwóch grupach wynosił odpowiednio 21,7 i 22,8 lat. Wy-niki poddano opracowaniu statystycznemu, przy użyciu testu chi-kwadrat. Wyniki. Młode kobiety żyjące w Polsce znamiennie częściej niż w Czechach obawiają się znacz-nych uciążliwości w przyszłej pracy, niesatysfakcjonującej relacji z przyszłym partnerem oraz częściej mają poczucie grożących w przyszłości niebezpieczeństw. Wnioski. Uzys-kane wyniki przemawiają za częstym istnieniem wśród młodych ludzi znacznego poczucia niepewności w zakresie ważnych sfer egzystencjalnych. W świetle analogicznych spostrzeżeń autorów, pochodzących z krajów o różnej za-sobności, poczucie niepewności ekonomicznej jest jedynie jednym z czynników oddziaływujących. Wyniki wskazują na celowość podjęcia badań nad różnymi akceptowanymi modelami rodziny.

Słowa kluczowe: spadek dzietności, wskaźnik uro-dzeń, poczucie niepewności ekonomicznej, bezrobocie, poczucie bezpieczeństwa, model rodziny

Nadesłano: 20.01.2014

Zatwierdzono do druku: 7.03.2014

Preliminary trial to ascertain the feeling of uncertainty of young women in Poland

and Czech Republic in the context of their intention to have a child

Wstępna próba porównania poczucia niepewności wśród młodych kobiet w Polsce i Czechach

w kontekście ich zamiaru posiadania dziecka

Andrzej Brodziak1, 3 (a, b, c, d), Jana Kutnohorska2 (a, c), Martina Cicha2 (b, c), Karina Erenkfeit1

(c, d), Barbara Białkowska3 (b, c)

1Institute of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, Sosnowiec, Poland

Head of Institute.: P.Z. Brewczyński, M.D., Ph.D.

2Institute of Health Care Studies of Tomas Bata University, Zlin, Czech Republic

Head of Institute.: M. Cicha, M.S., Ph.D.

3Institute of Nursing, State Higher School of Applied Sciences, Nysa, Poland

Head of Institute.: prof. A. Brodziak, M.D. Ph.D.

(a) ideas

(b) compilation of methods (c) collection of materials (d) work on text and references

iNtroductioN

An important contemporary social problem in most European countries is the decline of birthrate. The consequences of falling birthrates have already been experienced by all citizens. We realize that the „so-called” demographic crisis resulted in many schools being closed, a decrease in the number of potential students and the extension of retirement age. Due to the aging of the population the number of pensioners is increasing and the obligation to care for the elderly is becoming more demanding. The reasons for birthrate decline are not fully un-derstood. Therefore we have devoted the recent pa-per to this problem [1–3]. First, we have tried to verify an interdisciplinary hypothesis explaining the decrease in the number of births [1]. This hypothesis assumes that the decline is the result of psychologi-cal changes that have occurred in modern societies. We have enumerated in our paper about 40 changes of perceived and altered attitudes [1]. The formulat-ed changes allowformulat-ed for the development of detailformulat-ed questionnaire, which verified the convictions and attitudes of a particular person under consideration [1].

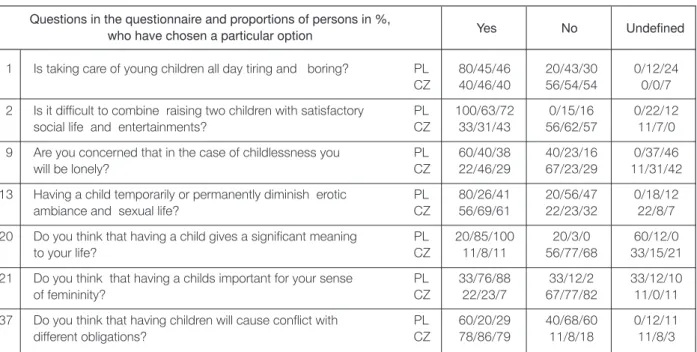

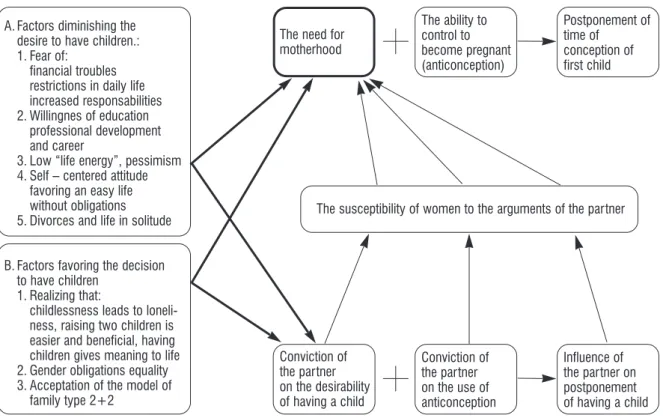

We have also checked which questions from our questionnaire meet the answers of the women who are childless, women who have only one child and women who have two or more children. Table I pre-sents seven such questions for which differences in frequencies of responses in these subgroups of women are considerable and statistically significant. In order to put the detected regularities in a com-pact manner it should be noted that: The key ele-ment is usually the overwhelming desire of a woman to have a child. This desire has recently been counterbalanced by several factors e.g. the willingness to get an education. Therefore women have recently tended to postpone the time of getting pregnant. That postponement is possible due to the ability to control the time of getting pregnant by effective contraception and increasing acceptance of its use.

To better understand the true reasons for the de-clining birthrate we decided to compare the beliefs and attitudes of middle-aged women in Poland and the Czech Republic, ie countries, which are charac-terized by one of the lowest fertility rates in Europe. It is known that the average living standard of Czech citizens is better than of Polish ones. A separate

pa-Table I. Selected questions of the questionnaire with significant differences between Polish and Czech women. The first number relates to women, who did not have children, second - who had only one child, a third - who had two or more children. The second row of numbers determine the same values for Czech women, however sometime the differences are here not significant

Tabela I. Wybrane pytania ankiety dla których występują znamienne statystycznie różnice w odpowiedziach kobiet z Polski i Czech. Pierwsza cyfra dotyczy kobiet które nie miały dzieci, druga – kobiet które urodziły jedno dziecko, trzecia – kobiet które urodziły dwoje lub więcej dzieci. W drugim wierszu podano wartości uzyskane dla kobiet zamieszkujących w Czechach Odpowiedzi dla kobiet z Czech nie zawsze wykazują znamienność statystyczną

Questions in the questionnaire and proportions of persons in %,

who have chosen a particular option Yes No Undefined

1 Is taking care of young children all day tiring and boring? PL 80/45/46 20/43/30 0/12/24

CZ 40/46/40 56/54/54 0/0/7

2 Is it difficult to combine raising two children with satisfactory PL 100/63/72 0/15/16 0/22/12

social life and entertainments? CZ 33/31/43 56/62/57 11/7/0

9 Are you concerned that in the case of childlessness you PL 60/40/38 40/23/16 0/37/46

will be lonely? CZ 22/46/29 67/23/29 11/31/42

13 Having a child temporarily or permanently diminish erotic PL 80/26/41 20/56/47 0/18/12

ambiance and sexual life? CZ 56/69/61 22/23/32 22/8/7

20 Do you think that having a child gives a significant meaning PL 20/85/100 20/3/0 60/12/0

to your life? CZ 11/8/11 56/77/68 33/15/21

21 Do you think that having a childs important for your sense PL 33/76/88 33/12/2 33/12/10

of femininity? CZ 22/23/7 67/77/82 11/0/11

37 Do you think that having children will cause conflict with PL 60/20/29 40/68/60 0/12/11

per shows the outcome of theses comparisons [2]. The data obtained allowed us formulate the follow-ing complementary theoretical explanation of the decline in the birth rate.

There are some convictions, attitudes and influ-ences, which encourage women to have children. The most important factors encouraging a woman to have a child is the awareness that childlessness leads to loneliness, therefore raising two children is easier than raising one child and beneficial be-cause it makes life meaningful. These encouraging factors can be suppressed by negative influences. It can lead women to stay childless or to decide to have only one child. The possible negative influ-ences have been summarized as the following types of impact:

1. Fear of increased responsibilities and restric-tions due to having a child.

2. Fear of inadequate financial situation. 3. Concern that having children will mean

respon-sibilities and efforts right throughout lifetime. 4. Low life energy and existential optimism. 5. Self-centered attitude, favoring an easy life,

without obligations, and freedom of action

It is possible to ascertain for a particular couple whether the different factors are in force or not. This provides a picture of the couple’s social and mental situation. Identification of the causes of falling birth rates provides guidance for counteract-ing the decline in the birth rate. One possibility is the promotion of „so-called „system of rapid tran-sition to a second child”. Therefore we have tried to check if there are favorable conditions in Poland for promoting shortening the time between the birth of the first two children [3]. In the observed groups of women a relatively large time gap was found between the average age of birth of the first and second child, which indicates the existence of a large group of women who could give birth to a second child earlier. The estimated attitude and sentiments of these women indicate the circum-stances which would promote the more rapid tran-sition to a second child [3]. There are different ways to explain the reasons for the decline of the birth rate [4–8]. Some researchers recently have taken into consideration the influence of uncertainty in various aspects of life which impacts the decision of young people to have children [9–13]. Brienna Perelli-Har-ris notes that the reasons for the decline of birth rate in European countries fall into four categories: economic uncertainty, social stress and anomie, changing values and belief systems, and unequal gender relations [13]. She wrote that economic

un-certainty caused by the bad economic situation of a country is one of the crucial determinants for the low fertility. According to this point of view, macro-level economic instability leads to financial uncer-tainty on the personal level, delaying partnership formation and childbearing.

Similar data are also available for countries in other parts of the world. Adsera et. al. have analyzed the impact of economic uncertainty on fertility in 18 countries of Latin America [11]. The most com-mon is uncertainty of employment and economic conditions. Some other researchers also evaluate the influence of the recent economic recession on fer-tility [14–17]. However many authors point also to other areas. The authors who considered the impact of the feeling of uncertainty conclude, that there is no immediate, direct relationship between wealth and fertility. Brienna Perelli-Harris is convinced for instance that the actual low fertility rate is rather due to social stress and anomie [13].

The notion of social anomie was introduced by Durkheim in 1894 as a breakdown in social stan-dards. It seems useful to explain the reasons for the drop in birth rate in some former communist coun-tries. Brienna Perelli-Harris emphasizes the impor-tance of mentality changes. She thinks that fertility decline in Ukraine may also be due to changes in values and belief systems. The breakup of the Soviet Union caused Ukraine to be flooded with external influences that may be changing priorities, behav-iors, and the way people think. It influenced the changes in family structures like later age of first marriage and birth, increase in cohabitation and non-marital childbearing all these occur concomi-tantly with a reorientation towards autonomy. It is important to compare the comments made by the authors, who analyze impact of anxiety, fear and insecurity in rich countries and countries with low-income, especially those that have recently under-gone profound social and economic transformation. Thus, a study of approximate assessment of the anx-iety and uncertainty among young women in Poland and the Czech Republic would be helpful. So we decided to make an approximate assessment of the existence of the anxiety and uncertainty among young women in Poland and the Czech Re-public. This time we attempt to check the state of mind of young women in the age range (21–23) yet before the optimal time for maternity.

MAtEriAl ANd MEthods

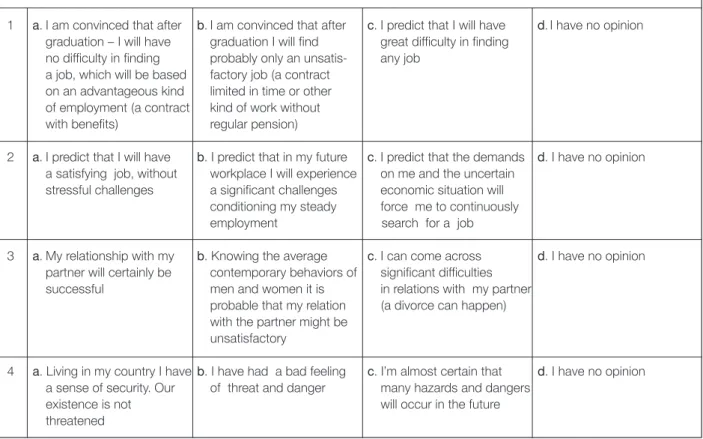

The data were collected in the groups of female students of nursing pursuing full-time studies classes in the academic year 2012/2013. We obtained the data from 42 students in Poland and from 51 stu-dents in the Czech Republic. The average age of young women in these groups was 21.7 years and 22.8 years respectively. Data were collected by means of self developed questionnaire presented in Table II. The questionnaire contains questions re-lated to uncertainty of possible future employment,

the rigors and the atmosphere in the future work, relationships with current or future partner and gen-eral feeling of insecurity and threats of living in the country. The questions included in the questionnaire aim to roughly determine whether the examined person feels uncertainty towards the enumerated existential fields. The obtained differences in the frequency of possible options of answers were veri-fied by the use of chi square test. We used the tool accessible under http://statpages.org/ctab2x2.html This program calculate also the Yates-corrected chi-square and the Mantel-Haenszel chi-chi-square.

We are kindly asking to complete the questionnaire.

The questionnaire is completed by: woman ■ years old ... man ■ year old ... I have no children ■

I have one child ■; two children ■; three children ■; >3 children ■

I born my child at the age of ■ years; second in age of ■ years; third in age of ■

I have no children yet, but I plan to have one child ■; two children ■; three children ■

I plan, I’ll have my first child at the age of ■, and the other at the age of ■

I live in a village ■; in a small town ■; in a medium-sized town (between 15–50 thousand inhabitants) ■; in a large town (>50 thousand inhabitants) ■

Please choose in any row numbered 1–4 one possible option a, b, c, d and circle.

1 a. I am convinced that after b. I am convinced that after c. I predict that I will have d. I have no opinion graduation – I will have graduation I will find great difficulty in finding

no difficulty in finding probably only an unsatis- any job a job, which will be based factory job (a contract

on an advantageous kind limited in time or other of employment (a contract kind of work without with benefits) regular pension)

2 a. I predict that I will have b. I predict that in my future c. I predict that the demands d. I have no opinion a satisfying job, without workplace I will experience on me and the uncertain

stressful challenges a significant challenges economic situation will conditioning my steady force me to continuously employment search for a job

3 a. My relationship with my b. Knowing the average c. I can come across d. I have no opinion partner will certainly be contemporary behaviors of significant difficulties

successful men and women it is in relations with my partner probable that my relation (a divorce can happen) with the partner might be

unsatisfactory

4 a. Living in my country I have b. I have had a bad feeling c. I’m almost certain that d. I have no opinion a sense of security. Our of threat and danger many hazards and dangers

existence is not will occur in the future

threatened

rEsults

Collective results obtained by the discussed ques-tionnaire are presented in Table III. This table shows the frequency of answers for particular options of possible responses to each item of the questionnaire provided by the young women in Poland and the Czech Republic.

These options of answers to which the statisti-cally significant difference in response rates were found between a group of young women in Poland and the Czech Republic are marked in the table III with an asterisk*. The most important findings are illustrated in Figure 1.

The analysis of obtained results convinces that the young women living in Poland were concerned sig-nificantly more frequently than in the Czech Republic – by a possible burden in future work, unsatisfactory relationships with future partners, and more often with a sense of impending danger in the future.

This finding should be interpreted in the light of our previous results presented in our formed publi-cations, which focused on older women. The results presented in this paper relate to younger women in the age preceding the decision to have children. The importance of frequent feeling of uncertainty of young people for the whole range of factors relevant to making decisions about having children requires

detailed discussion. Such considerations should fa-cilitate Figure 2.

Table III. Number of answers a, b, c, d of young Polish and Czech women concerning the level of anxiety in four existential areas. The table should first be read after reading the questionnaire presented in table II. The quantities are given separately for a group of Polish and Czech young women. The answers statistically significant are marked with an asterisk (*) Tabela III.Liczba odpowiedzi a, b, c, d młodych kobiet polskich i czeskich dotyczących poziomu niepokoju w czterech zakresach

egzystencjonalnych. Tabelę należy odczytać zapoznając się wpierw z formularzem ankiety zamieszczonym w tabeli II. Odpowiedzi dla których znaleziono znamienne statystycznie różnice w częstościach zaznaczono gwiazdką (*)

Type

Number of answers Number of answers Number of answers Number of answers of

in-of the type a./other of the type b./other of the type c./other of the type d./other security

1 a. PL 17/25 (40,5 %) b. PL 13/29 (30.9%) c. PL 1/41 (2,4 %) d. PL 11/31 (26,2%) CZ 15/36 (29,4 %) CZ 10/41 (19,6%) CZ 7/44 (13,7% CZ 19/32 (37,2%)

2 a. PL 3/39 (7,1%) b. PL 35/7 (83,3%) * c. PL 4/38 ((9,5%) d. PL 0/42 (0 %) * CZ 11/40 (21,6%) CZ 20/31(39,2%) CZ 4/47 (7,8%) CZ 16/35 (31,4%)

3 a. PL 16/26 (38,1%) b. PL 24/18(57,1%) * c. PL 2/40 (4,8%) d. PL 0/42 (0%) * CZ 16/35 (31,4%) CZ 14/37 (27,4%) CZ 2/49 (3,9%) CZ 19/32(37,2%)

4 a. PL 5/36 (11,9%) b. PL 30/11(71,4%) * c. PL 6/35 (14,3%) d. PL 0/42(0%) * CZ 12/39 (23,5%) CZ 5/46 (9,8%) CZ 14/37 (27,4%) CZ 20/31(39,2%)

2 – b χ2

418,55, p*0,0001 3 – d χ2

419,66, p*0,0001 2 – d χ2

415,91, p*0,0001 4 – b χ2440,88, p*0,00001 3 – b χ2

48,40, p*0,004 4 – d χ2

420,98, p*0,00001

Fig. 1. Proportion in % of answers of young Polish and Czech women concerning the level of uncertainty in four existential areas (troubles of finding a job, challenges in the future place of employment, possible difficulties in relation with the partner, general insecurity and threats in the country). The differences in proportions of answers for three last items are statistically significant

discussioN

This paper presents the results of the next stage of surveys conducted by us in order to clarify the reasons for the decline in the birth rate. Our previous publications focused on the attitudes and beliefs of older women in childbearing age. According to many authors from different countries also the in-security of young people in the age preceding the decision to have a child must be taken into account. The results provide data that truly young Polish and Czech women perceive uncertainty in several existential areas. What’s more the feeling of uncer-tainty is more pronounced among women living in Poland. The discussion, however is required about the importance of feeling of uncertainty on the background of other possible influences such as anomie, change of values, unequal gender relations and especially the predominant accepted model of family. It is necessary to remember that many dif-ferent hypotheses are proposed to explain the rea-sons of decline of number of birth. We try to illus-trate the relations of factors which are at play with the help of Figure 2. Frejka sees similar reasons for the decline in the birth rate in all post-communist

countries [18]. Lithuanian researchers are inclined to the hypothesis that the major impact on the de-cline in the number of births were social, economic and mental changes. Stankuniene et al. says that in the second half of the 1990s, the effect of the eco-nomic determinants started to weaken and was in-creasingly superseded by determinants related to mental changes which were taking place in the Lithuanian society [19]. These authors argue that the social transformation produced a sense of a so-cial loss after some of the Soviet era guarantees, such as employment and income, free education and health care [19]. They emphasized also the in-fluence of diffusion of individualization due to the consolidation of market relations, increasing free-dom of choice, democratization of the society, and the liberalization of value-orientated lifestyles. Stankuniene et al. says that in Lithuantia young people spend more and more time now studying, looking for opportunities for self realization, and development of their own professional career. In-creasing importance is attached to quality of life, hedonistic aspirations, and consumption [19]. The authors analyzing the demographic situation in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Estonia, Slovenia, Slovakia

and Russia also generally refer to the impact of sim-ilar social changes [20–26]. The influence of eco-nomic uncertainty, anomie and changing values, can be exacerbated by unequal gender relation. The gender inequity may worsen in the light of com-bining work and childbearing. In southern Euro-pean countries like Italy and Spain where fertility rate is low, women have taken major steps in equal-ity in the educational system and labor force, but have not achieved similar equality at home. Women are provided with little domestic childcare or state childbearing support and must decide whether to limit their childbearing or reduce their career aspi-rations [27]. In northern European countries, on the other hand, women receive more support from their partners and from governmental resources, in-cluding subsidized childcare and maternity leave [28–30]. As a result, these countries have maintained fertility rates at satisfactory level. The above men-tioned authors are of the opinion that in the post – communist countries, women have experienced in-creased equality in the workforce-similar to south-ern European countries). A large proportion of the female population enjoy higher education and par-ticipates in the labour force, however as in southern Europe the gender distribution of domestic work is unequal and, in addition, there is a little state sup-port for families. Understanding of these conditions facilitate the comparison of the explanations for-mulated in post – communist, rather poor countries with the analogous considerations of the authors from Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Netherlands, Germany and France [28–34].

Dorbritz says that Germany is a low-fertility country with a rapidly ageing population and ac-cordingly the trend will remain so for the foreseeable future [31]. He argues that there are several reasons for this trend. Germany is among countries with the highest rates of childlessness in the world, and that fact has become widely accepted. This is illus-trated by changes in living arrangements. A broad range of living arrangements has been added to the basic model of marriage with children; single living, non-marital cohabitation, lone parenthood, patch-work families and living together but apart. Dorbritz is convinced that a culture of individualism has spread across Germany, which forms the basis for widespread decisions against family formation [31]. The desired number of children has become low and family policy is considered to be a failure in terms of its influence on fertility. German family policy has had a traditional orientation centered on monetary support to families and on the promotion of the male breadwinner model. Women have been

largely forced to choose between family and work, and leave the labor market when a child is born. The still prevailing concept of family policy does not help to reduce the pressure to choose between work and family life, and thus makes it easier to decide not to have children, especially in case of highly educated women [31].

There are some countries in Europe, which are characterized by rather high fertility rate. It is inter-esting how this phenomenon is explained by ex-perts representing these countries [28–30]. Olah et al. notes that in Sweden post-modern values are dominant and that the society is highly secularized [28]. The desired number of children is among the highest in the European Union, and childlessness is not frequent. The level of female labor-force par-ticipation is the highest in Europe and young women are just as much educated as men. Family policies, based on the principle of equality across social groups and gender, seem to play an important role in keeping fertility rate relatively high. The fam-ily policies, with such elements as eligibility to parental-leave as well as the availability of public childcare has an impact on the fluctuations of fer-tility rates.

Fokkema et al. notes that in the Netherlands the periodical total fertility rate has stabilized since the late 1970s at around 1.6 children per woman [30]. So, the drop in fertility, however, has not been as sharp as in many other regions of Europe. Although the Netherlands has one of the oldest first-time mothers, total fertility rate is still rather high com-pared to other European countries. The main driv-ing force behind specific fertility trends in the Netherland explains Fokkema et al. by changing patterns of home leaving and partnership formation, declining its stability, and the growing acceptability of contraception, extended education, rising partic-ipation of women in labor force, economic uncer-tainties, growing migrant population, and family policies.

cur-rent low level of fertility in most European countries (delay in fertility, decline in marriage, increased birth control, greater economic uncertainty). These au-thors are convinced that France’s fertility level can be partly explained by its active family policy intro-duced after the Second World War, and adapted in the 1980s to accommodate women’s entry into the labour force. This policy is the result of a battle, fu-elled by pro-natalism, between the conservative sup-porters of family values and the promoters of state-supported individual equality. French family policy thus encompasses a wide range of measures based on varying ideological backgrounds, and it is difficult to classify in comparison to the more precisely fo-cused family policies of other European welfare states. The active family policy seems to have created especially positive attitudes towards two- or three child families in France [33]. Pailhé et al. investigated whether unemployment and insecure employment periods merely delay fertility or also impact on fer-tility in France. They conclude that employment un-certainty tends to delay a first parenthood but has a relatively little effect on lifetime fertility in France. They state that in France the generous state support to families associated with a generous unemploy-ment insurance system, and the strong French two-child family norm, may explain why economic un-certainty affects fertility less there than elsewhere [34]. We try to illustrate the importance of the feeling of uncertainty and the relationships between various others factors influencing the number of birth, raised in th above discussion with the help of Figure 2.

coNclusioNs

1. The young women living in Poland are frequently concerned by uncertainty related to employment, possible burden in future work, possible unsatis-factory relationships with future partners, and a sense of impending dangers in the future. 2. The young women living in Poland were

con-cerned significantly more frequently than in the Czech Republic uncertainty related to possible burden in future work, unsatisfactory relation-ships with future partners, and more often with a sense of impending danger in the future. 3. The assessment of the impact of uncertainty on

the decision to have a child, carried out by the authors from more prosperous countries and in countries that have recently passed political trans-formation leads to the conclusion that these feel-ings of insecurity are only one of the factors af-fecting the decisions.

4. Further studies are needed to verify the legitimacy of other explanations of the decline in the num-ber of births, in particular the prevalence and ac-ceptance of different, desired models of the fam-ily.

Funding:authors’ financial sources

rEfErENcEs

1. Brodziak A., Wolińska A., Ziółko W.: Próba weryfikacji in-terdyscyplinarnej hipotezy wyjaśniającej spadek liczby uro-dzeń i niską dzietność. Medycyna Środowiskowa-Environ-mental Medicine, 2012, 15(4): 104-115.

2. Brodziak A., Kutnohorska J., Cicha M., Wolińska A., Ziółko E.: Comparison of fertility ratios, attitudes and beliefs of Po-lish and Czech women. Medycyna Środowiskowa-Environ-mental Medicine, 2013, 16(2): 69-78.

3. Brodziak A., Wolińska A., Ziółko E.: Czy zachodzą okolicz-ności sprzyjające promowaniu systemu szybkiego przejścia do drugiego dziecka? Medycyna Środowiskowa-Environmen-tal Medicine, 2013, 16(1): 67-74.

4. Hoem J.M.: Childbearing Trends and Policies in Europe. De-mographic Research, 2008, 19: 1-4.

5. Frejka T., Sobotka T.: Fertility in Europe: Diverse, delayed and below replacement. Demographic Research, 2008, 19: 15-46.

6. Sobotka T., Toulemon L.: Changing family and partnership behaviour: Common trends and persistent diversity across Europe. Demographic Research, 2008, 19: 85-138. 7. Lutz W.: Fertility rates and future population trends: will

Eu-rope’s birth rate recover or continue to decline? Int J Androl. 2006, 29: 25-33.

8. Lutz W.: Dimensions of global population projections: what do we know about future population trends and structures? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010, 365(1554): 2779-91.

9. Bachrach Ch.A., Philip Morgan Ph.: A Cognitive – Social Model of Fertility Intentions. Population and Development Review, 2013, 39: 459-485.

10. Adsera A.: The interplay of employment uncertainty and education in explaining second births in Europe. Demograp-hic Research. 2011, 25: 513-544.

11. Adsera A., Menendez A.: Fertility changes in Latin America in periods of economic uncertainty. Popul Stud (Camb). 2011, 65: 37-56.

12. Kotowska I., Jóźwiak J., Matysiak A., Baranowska A.: Poland: Fertility decline as a response to profound societal and labour market changes? Demographic Research, 2008, 19: 795-854. 13. Perelli-Harris B.: Ukraine: On the border between old and

new in uncertain times. Demographic Research, 2008, 19: 1145-1178.

14. Sobotka T., Skirbekk V., Philipov D.: Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. Popul Dev Rev. 2011, 37: 267-306.

15. Uutela A.: Economic crisis and mental health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010, 23: 127-30.

17. Billingsley S.: Economic crisis and recovery: Changes in se-cond birth rates within occupational classes and educational groups. Demographic Research, 2011, 24: 375-406. 18. Frejka T.: Determinants of family formation and childbearing

during the societal transition in Central and Eastern Europe. Demographic Research, 2008, 19: 139-170.

19. Stankuniene V., Jasilioniene A.: Lithuania: Fertility decline and its determinants. Demographic Research, 2008, 19: 705 -742.

20. Sobotka T., Šťastná A., Zeman K., Hamplová H., Kantorová V.: Czech Republic: A rapid transformation of fertility and family behaviour after the collapse of state socialism. De-mographic Research 2008, 19: 403-454.

21. Spéder Z., Kamarás F.: Hungary: Secular fertility decline with distinct period fluctuations. Demographic Research 2008, 19: 599-664.

22. Speder Z.: Rudiments of recent fertility decline in Hungary: Postponement, educational differences, and outcomes of changing partnership forms. Postponement, educational dif-ferences, and outcomes of changing partnership forms. De-mographic Research, 2006, 15: 253-283.

23. Klesment M., Puur A.: Effects of education on second births before and after societal transition: Evidence from the Esto-nian Generations and Gender Survey. Demographic Research, 2010, 22: 891-932.

24. Stropnik N., Šircelj M.: Slovenia: Generous family policy wit-hout evidence of any fertility impact. Demographic Research, 2008, 19: 1019-1058.

25. Vaňo B. Pilinská V., Jurčová D. Potančoková M. Slovakia: Fer-tility between tradition and modernity. Demograpgic Re-search, 2008, 19: 973-1018.

26. Zakharov S. Russian Federation: From the first to second de-mographic transition. Dede-mographic Research, 2008, 19: 907-972.

27. Delgado M., Meil G., Zamora-López F. Spain: Short on chil-dren and short on family policies. Demographic Reserarch, 2008, 19: 1059-1104.

28. Oláh L., Bernhardt E. Sweden: Combining childbearing and gender equality. Demographic Research, 2008, 19:1105-1144 29. Lassen T.H., Sobotka T., Jensen T.K. et al.: Trends in rates of

natural conceptions among Danish women born during 1960-1984. Hum Reprod. 2012, 27: 2815-22.

30. Fokkema T., de Valk H., de Beer J., van Duin C.: The Nether-lands: Childbearing within the context of a „Poldermodel” society. Demographic Research, 2008, 19: 743-794. 31. Dorbritz J.: Germany: Family diversity with low actual and

desired fertility. Demographic Research, 2008, 19: 557-598. 32. Prskawetz A., Sobotka A., Buber I. Engelhardt H., Gisser R.: Austria: Persistent low fertility since the mid – 1980s. De-mographic Research, 2008, 19: 293-360.

33. Toulemon L., Pailhé A., Rossier C.. France: High and stable fertility. Demographic Research, 2008,19:503-556. 34. Pailhé A., Solaz A.: The influence of employment uncertainty

on childbearing in France: A tempo or quantum effect? De-mographic research. 2012, 26: 1-40.

Address for correspondence: Prof. Andrzej Brodziak, MD, PhD Institute of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health in Sosnowiec, Poland Phone number 48 774355951