Abstract

Many countries in Europe are searching for new ways to engage citizens and involve the third sector in the provision and governance of social services in order to meet major demographical, political and economic challenges facing the welfare state in the 21st century. Co-production provides a model for the mix of public service agents and citizens who contribute to the provision of a public service. New Public Governance (NPG) puts much greater emphasis on citizen participation and third sector provision of social services than either traditional public administration or New Public Management. Co-production is a core element of NPG that promotes the mix of public service agents and citizens who contribute to the provision of a public service. This paper explores the implications of two comparative studies of parent participation in preschool services in Europe. They observe that citizen participation clearly varies between different providers of social services, as too does client and staff influence. This empirical overview concludes that some third sector providers can facilitate greater citizen participation, while a ‘glass ceiling’ for participation exists in municipal and for-profit preschool services. These findings can contribute to a better understanding of the emerging paradigm of New Public Governance.

Key words: Participation, co-production, New Public Governance, third sector and social services.

Resumo

Muitos países na Europa estão buscando novas maneiras de envolver os cidadãos e o terceiro setor na provisão e gestão dos serviços sociais a fim de atender aos principais desafios demográ-ficos, políticos e econômicos do Estado no século 21. A coprodução fornece um modelo para a combinação de agentes de serviços públicos e cidadãos que contribuem para a prestação de um serviço público. Nova Governança Pública (NPG) coloca muito mais ênfase na participação do cidadão e oferta de serviços sociais do terceiro setor do que a administração pública tradicional ou Nova Gestão Pública. A coprodução é um elemento central da NPG, que promove a mistura de agentes de serviços públicos e cidadãos que contribuem para a prestação de um serviço público. Este artigo explora as implicações de dois estudos comparativos de participação dos pais nos serviços de pré-escola na Europa. Foi observado que a participação do cidadão varia de acordo com os diferentes prestadores de serviços sociais e também de acordo com a influência de clientes e funcionários. Esta visão empírica conclui que alguns provedores do terceiro setor podem facilitar a maior participação dos cidadãos, enquanto uma “barreira invisível” para esta participação existir no município e nos serviços pré-escolares com fins lucrativos. Esses achados podem contribuir para uma melhor compreensão do paradigma emergente da Nova Governança Pública.

Palavras-chave: participação, coprodução, Nova Governança Pública, Terceiro Setor, serviços sociais. Victor Pestoff1

victor.pestoff@esh.se

Co-production, new public governance

and third sector social services in Europe

1 Professor Emeritus in Political Science and Guest

Professor, Institute for Civil Society Studies, Ersta Sköndal University College. Ersta Sköndal högskola Enheten för forskning om det civila samhället, Box 11189, 100 61, Stockholm, Sweden.

Co-Produção, nova governança pública e

serviços sociais no Terceiro Setor na Europa

Introduction

The concept of governance gained extensive attention recently, becoming a buzz word in the social sciences. It is used in a wide array of contexts with widely divergent meanings. Van Kersbergen and van Waarden (2004) survey the literature and identify no fewer than nine different definitions of the concept, while Hirst (2002) attributes it five different meanings or con-texts. They include economic development, international insti-tutions and regimes, corporate governance, private provision of public services in the wake of New Public Management and new practices for coordinating activities through networks, partner-ships and deliberative forums (Hisrt, 2002, p. 18-19). Hirst ar-gued that the main reason for promoting greater governance is the growth of ‘organizational society’. Big organizations on ei-ther side of the public/private divide in advanced post-industrial societies leave little room for democracy or citizen influence. This is due to the lack of local control and democratic processes for internal decision-making in most big organizations. The con-cept of governance points to the need to rethink democracy and find new methods of control and regulation, ones that do not rely on the state or public sector having a monopoly of such practices (Hisrt, 2002, p. 21).

Concerning standards for legitimate governance beyond the state, Gbikpi and Grote (2002) note that three demands of democratic theory and practice should be considered. They are (a) the principle of differentiation, territorial vs. functional; (b) the political style, horizontal vs. hierarchical, and (c) the mode of legitimation, participation vs. effectiveness. They argue that the political space beyond the state appears to be more conducive to deliberative communication modes of arguing and bargaining than to majority voting. Thus, it is necessary to break free from thinking linked to the model of majoritarian-democracy char-acterizing the territorial state, especially in terms of multi-level governance. Participatory governance tries to make sure that all those who will be affected by the policies at stake in the gover-nance arrangements will be associated to the policy process in question. Thus, participatory governance is less a question of in-stitutionalizing a set of procedures for choosing those in charge of the policy-making than it is a kind of ‘second best’ solution for approaching the question of effective participation of the persons likely to be affected by the policies designed (Gbikpi and Grote, 2002, p. 23). Moreover, participatory governance can be effective in the realization of policy objectives because it can help to overcome problems related to implementation, due to motives and compliance. This also holds true at the sub-munici-pal level, particularly in public private partnerships between the state and civil society to implement national policies (Pestoff, 2008a). Elsewhere, Rokkan (1966) argues that “[...] votes count in the choice of governments, but other resources will decide which policies they will pursue”. This suggests that the tensions between the principle of territorial representation is not always at odds with functional representation via corporative channels

of influence. Thus, it is more a question of when and where to promote participative models than whether to do so.

Johansson and Hviden (2010) propose a post-Marshallian analytical framework for understanding social citizenship in the 21st century. They argue that the development of the European discourse on citizenship appears to challenge some of Marshall’s original presentation of social citizenship, in particular through (a) renewed emphasis on citizens’ duties; (b) also on their partici-pation and (c) the emergence of citizen consumerism (Johans-son and Hviden, 2010, p. 6). They relate these developments to David Miller’s (2000) threefold conceptualization of citizenship, on the one hand, and the distinction between passive and active citizenship, on the other. Miller emphasized that citizenship in the Social-Liberal understanding conceives of the relationship between the individual and the state as one based on an encom-passing set of mutual rights and responsibilities. From the Liber-tarian perspective the relationship is narrower and it underlines the individual’s own responsibility and autonomy, combined with very limited activities of the state. Finally, citizenship in a (Civic) Republican understanding focuses on a citizen’s partici-pation in the affairs of his/her community and the expectation that he/she is committed to promoting the well-being of the community as a whole (Johansson and Hviden, 2010, p. 1).

Turning to participation, Johansson and Hviden argue that a more dynamic relationship between welfare states and citizens is evolving today since citizens themselves expect (or are expected) to play a more active role in taking diverse risks and promoting their own welfare (Giddens, 1998). Throughout Europe there are new discourses on citizens’ involvement and a search for new forms of civil participation beyond representative democracy. They often go under the heading of ‘civil dialogue’, ‘collaborative governance’, ‘participatory governance’ or ‘asso-ciative democracy’ (Gbikpi and Grote, 2002; Fung and Wright, 2003; Hirst, 1994; Westall, 2011). Today European welfare states pay greater attention to the role of citizens as co-producers of welfare, through volunteering to help others (Johansson and Hviden, 2010, p. 9) or the spread of self-help groups.

The post-Marshallian framework proposed by Johansson and Hviden combines both these dimensions and is summarized in Table 1 (Johansson and Hviden, 2010, p. 12-13). First, in the Socio-Liberal view more active citizenship would imply that the state asks citizens to more actively fulfill specific duties in the form of welfare-to-work programs in return for social benefits of different kinds. Here the distinction between passive and ac-tive citizens plays out either in receiving and claiming rights or the fulfillment of duties in return for entitlements. This was the basis of the welfare reforms promoted by US President Clinton in the 1990s and British PM Tony Blair nearly a decade later. Second, from a Libertarian perspective, greater emphasis is giv-en to the responsibility and autonomy of an individual and the tasks of the state remain very limited. Here the focus is on wel-fare consumerism and greater user choice in the private mar-ket, which corresponds to the view of New Public Management (NPM). Third, citizenship in a (Civil) Republican understanding

generally focuses more on a citizen’s participation in the affairs of his or her community (Johansson and Hviden, 2010, p. 11-12). Here there can either be managed participation, informed con-sent or agency-directed help for passive citizens, while self-governed activity, co-responsibility and commitment to par-ticipate in deliberation and decision-making motivate the more active ones (Johansson and Hviden, 2010, p. 12-13). The latter appears closer to the New Public Governance (NPG) perspective.

Definitions of co-production range from “the mix of public service agents and citizens who contribute to the provi-sion of public services” to “a partnership between citizens and public service providers”. The concept of co-production was originally developed by Elinor Ostrom and the Workshop in Po-litical Theory and Policy Analysis at Indiana University during the 1970s to describe and delimit the involvement of ordinary citizens in the production of public services. They struggled with the dominant theories of urban governance, whose underlying policies recommended massive centralization of public services, but they found no support for claims of the benefits of large bureaucracies. They also realized that the production of services, in contrast to goods, was difficult without the active participa-tion of those persons receiving the service.

Thus, they developed the term co-production to describe the potential relationship that could exist between the ‘regular producer’ (street-level police officers, schoolteachers, or health workers) and their clients who want to be transformed by the service into safer, better-educated or healthier persons (see Parks et al., 1999 [1981]). Co-production is, therefore, charac-terized by the mix of activities that both public service agents and citizens contribute to the provision of public services. The former are involved as professionals or ‘regular producers’, while ‘citizen production’ is based on voluntary efforts of individuals or groups to enhance the quality and/or quantity of services they receive (Parks et al., 1999 [1981]).

Moreover, in recent decades, changes in the public sec-tor itself were brought to the fore by various scholars in order to better understand the role of citizens and the third sector in the provision of public services. First, Vincent Ostrom chal-lenged the dominant perspective of unitary provision of most public services and developed an alternative version of respon-sible government and democratic administration (2008 [1973]). Then, his wife, Elinor Ostrom and her colleagues analyzed the role of citizens in the provision of public services in terms of co-production (Parks et al., 1999 [1981]). More recently several other prominent scholars of public administration and manage-ment joined the discussion. Hartley (2005) identified and ana-lyzed three approaches to the public sector itself in the postwar period and their implications for policy-makers, managers and citizens. These three approaches are traditional public adminis-tration, New Public Management and Networked Governance; Osborne (2006, 2010) viewed New Public Management as a tran-sitory stage in the evolution towards New Public Governance; Bovaird (2007) argued for a radical reinterpretation of policy making and service delivery in the public domain, resulting in

Public Governance; while Denhardt and Denhardt (2008) pro-mote New Public Service as serving citizens rather than steering them. Common to all these newer perspectives on public ser-vices is a central role attributed to greater citizen participation, co-production and third sector provision of public services.

This paper focuses on co-production, particularly of so-cial services, and discusses the third sector and the role of citi-zens in the provision and governance of such services. In doing so, it also addresses the questions about the changing relation-ship between the third sector and the state in Europe. Can dif-ferent perspectives on these changes be captured by difdif-ferent approaches to the study of public administration and manage-ment? What role is attributed to citizen participation and third sector provision of public services by traditional public adminis-tration, New Public Management and New Public Governance? What does comparative empirical evidence from preschool ser-vices in Europe say about the co-production of social serser-vices? This chapter proposes to explore these questions.

Public administration regimes

and co-production

We need to inquire how changes in the nature of the pu-blic sector itself and different pupu-blic administration and mana-gement regimes might impact on the relationship between the third sector and the public sector in general. More specifically, how do different relationships between the government and its citizens impact on the role of the third sector as a provider of social services? The Ostroms’ sketched the development and gro-wth of the study of public administration in the USA, including such foreground figures as Woodrow Wilson, Herbert Simon, the public choice school, etc. (Ostrom and Ostrom, 1999). They pro-pose a new perspective on the study of public administration and argue that if the traditional principles of public adminis-tration are inapplicable, then we must develop a new theory of public administration that is more appropriate for citizens living in democratic societies. They conclude that perhaps a system of public administration composed of a variety of multi-organiza-tional arrangements that is highly dependent upon mobilizing clientele support would come reasonably close to a public ad-ministration with a high level of performance in advancing the public welfare (Ostrom and Ostrom, 1999, p. 48).

Calabrò (2010) documents the growth in recent years of academic interest in ‘networked governance’ and ‘public go-vernance’, in a review of journals on public administration and management between 1970 and 2009. Hartley identified and analyzed three approaches to the public sector in the post-war period for their implications for policy-makers, managers and citizens. She spells out the various dimensions, similarities and differences of these three public sector paradigms, i.e., tradi-tional public administration, New Public Management and Ne-tworked Governance. The first two paradigms are familiar, while the third is based on evidence of emerging patterns of

gover-nance and service delivery, which can be called ‘citizen-centered governance’ or Networked Governance. In particular, the actors include hierarchies and public servants in the first paradigm; markets, purchasers and providers and clients and contractors in the second; and networks, partnerships and civil leadership in the latter. Key social benefits associated with each of them are public good in the former, public choice in the second and public value in the latter (Calabrò, 2010, p. 28).

Each paradigm or public administration regime may be linked to a particular ideology and historical period. However, they can also be seen as competing, according to Hartley, since they co-exist as ‘layered realities’ for politicians and managers (Calabrò, 2010, p. 29), and in academic and public discourse. The role of citi-zens in the respective paradigms is either as clients, with little say about services; customers, with some limited choice in the scope and content of services; or as co-producers, who can play a more direct role in the provision of services. Hartley argues that as the UK moves to Networked Governance, the role of the state becomes to steer action within complex social systems rather than to control it solely through hierarchies or market mechanisms.

Bovaird (2007, p. 217) argues that the emergence of governance as a key concept in the public domain is relative-ly recent, and he traces the evolution of the concept in public administration. He suggests that ‘governance’ provides a set of balancing mechanisms in a network society, although it is still a contested concept, both in theory and in practice. By the end of the 1990s various concerns about corporate governance, local governance and network society had crystallized into a wider focus on ‘public governance’, which he defines as “[...] the ways in which stakeholders interact with each other in order to in-fluence the outcomes of public policies” (Bovaird, 2007, p. 220). Co-production becomes a key concept and the importance attri-buted to it by Public Governance has two major implications for public administration. First, it seriously questions the relevance of the basic assumptions of NPM that service delivery can be separated from service design, since service users now play key roles in both service design and delivery. Second, service users and professionals develop a mutual and interdependent rela-tionship in which both parties take risks and need to trust each other (Bovaird, 2007 p. 222).

Osborne (2006, 2010) argues that New Public Manage-ment (NPM) has actually been a transitory stage in the evolution from traditional public administration (PA) to what he calls New Public Governance (NPG). He agrees that public administration and management (PAM) has gone through three dominant sta-ges or modes: a longer pre-eminent one of PA until the late 1970s/early 1980s; a second mode of NPM, until the beginning of the 21st century; and an emergent third one, NPG since then. The time of NPM has thus been a relatively brief and transitory one between the statist and bureaucratic tradition of PA and the embryonic one of NPG (Osborne, 2006, 2010).

Hierarchy is the key governance mechanism for PA, with a focus on vertical line management to insure accountability for the use of public money. By contrast, NPM is a child of

neo-classi-cal economics and particularly of rational/public choice theory. It has an emphasis on implementation by independent service units, ideally in competition with each other and a focus on economy and efficiency. Finally, NPG is rooted firmly within organizational sociology and network theory and it acknowledges the increa-singly fragmented and uncertain nature of public management in the 21st century. “It posits both a plural state where multiple interdependent actors contribute to the delivery of public services and a pluralist state, where multiple processes inform the public policy making system” (Osborne, 2006, p. 384).

Moreover, Bovaird (2007) argues that there has been a radical reinterpretation of the role of policy making and service delivery in the public domain. Policy making is no longer seen as a purely top-down process but rather as a negotiation among many interacting policy systems. Similarly, services are no longer simply delivered by professional and managerial staff in public agencies, but they are co-produced by users and communities. He presents a conceptual framework for understanding the emerging role of user and community co-production. Traditional conceptions of service planning and management are, therefore, outdated and need to be revised to account for co-production as an integrating mechanism and an incentive for resource mobilization – a poten-tial that is still greatly underestimated (Bovaird, 2007).

Finally, Denhardt and Denhardt (2008) argue that the theoretical framework for New Public Service (NPS) gives full priority to democracy, citizenship and service in the public in-terest. It offers an important and viable alternative to both the traditional and the now dominant managerialist model of public management. They suggest that public administration should begin with the recognition that an engaged and enli-ghtened citizenship is crucial to democratic governance. Accor-dingly, public interest transcends the aggregation of individual self-interest. From this perspective the role of government is to bring people “to the table” and to serve citizens in a manner that recognizes the multiple and complex layers of responsibili-ty, ethics, and accountability in a democratic system (Denhardt and Denhardt, 2008, p. 198-199).

Due to the conceptual similarity between these authors I will employ the term New Public Governance for a regime or paradigm that emphasizes greater citizen engagement in and co-production of public services and greater third sector pro-vision of the latter. However, co-production in the context of multi-purpose, multi-stakeholder networks raises some crucial democratic issues that have important implications for public service reforms.

Co-Production:

two comparative studies

The empirical materials briefly reviewed in this paper come from two separate studies reported elsewhere: a compara-tive multiple case study of family policy and alternacompara-tive provi-sion of preschool services in promoting social coheprovi-sion in several

European countries and a comparative survey study of public, private for-profit, parent cooperative and worker cooperative preschool services in Sweden. They permit a discussion of the political value added by the third sector provision of social ser-vices. Some third sector providers can facilitate greater citizen participation and thereby help to breach the ‘glass ceiling’ found in public and for-profit social services. This will be discussed in greater detail in section (ii) below.

(i) Co-production: two comparative studies of parents’ participation in preschool services

Turning briefly to two comparative studies of parent par-ticipation in preschool services in Europe, the first is the TSFEPS Project2 that permitted us to examine the relationship between parent participation in the provision and governance of pre-school services in eight EU countries (Pestoff, 2008c). We found different levels of parent participation in different countries and in different forms of provision, i.e., public, private for-profit and third sector preschool services. The highest levels of parent participation were found in third sector providers, like parent associations in France, parent initiatives in Germany, and parent cooperatives in Sweden (Pestoff, 2008c). We also noted different kinds of parent participation, i.e., economic, political, social and service specific. Economic participation involves contributing time and materials to the running or maintenance of a facility; political participation means being involved in discussions and decision-making; while social participation implies planning and contributing to various social events, like the Christmas party, Spring party, etc. Service specific participation can range from the management and maintenance of a facility, or replacing the staff in case of sickness or when they attend a specialized course, to actually working on a regular basis in the childcare facility. All four kinds of participation were readily evident in third sector providers of preschool services, while both economic and politi-cal participation were highly restricted in municipal and private for-profit services. Moreover, we observed variations in the pat-terns of participation between countries. Parents participated actively in the provision of third sector preschool services at the site of delivery in France, Germany and Sweden, but only in the first two countries in their governance at the local or regional levels, and not in the latter one (Pestoff, 2008c).

The second is a study of the Swedish welfare state that focuses on the politics of diversity, parent participation and service quality in preschool services (Vamstad, 2007). It com-pared parent and worker co-ops, municipal services and small for-profit firms providing preschool services in Ostersund and Stockholm. This study not only confirms the existence of the four dimensions of co-production noted earlier in the TSFEPS study, but it also underlines clear differences between various

providers concerning the importance attributed to these di-mensions of co-production. Vamstad study demonstrates that parent co-ops promote much greater parent participation than the other three types of preschool service providers, in terms of economic, social, political and service specific participation. This comes as no great surprise, since the essence of the parent co-operative model is parent participation. However, his study also shows that neither public nor private for-profit services allow for more than marginal or ad hoc participation by parents in the preschool services. For example, parents may be welcome to make spontaneous suggestions when leaving their child in the morning or picking her/him up in the evening from a municipal or small private for-profit preschool facility. They may also be welcome to contribute time and effort to a social event like the annual Christmas party or Spring party at the end of the year. Also discussion groups or “Influence Councils” can be found at some municipal preschool services in Sweden, but they provide parents with very limited influence. More substantial participa-tion in economic or political terms can only be achieved when parents organize themselves collectively to obtain better quality or different kinds of preschool services than either the state or the market can provide.

Thus, parent co-ops in Sweden promote all four kinds of user participation: economic, social, political and complementa-ry. They provide parents with unique possibilities for active par-ticipation in the management and running of their child(ren)’s preschool facility with unique opportunities to become active co-producers of high quality preschool services for their own children and the children of others. It is also clear that other forms of preschool services allow for some limited avenues of co-production in public financed preschool services, but the parents’ possibilities for influencing the management of such services remain rather limited.

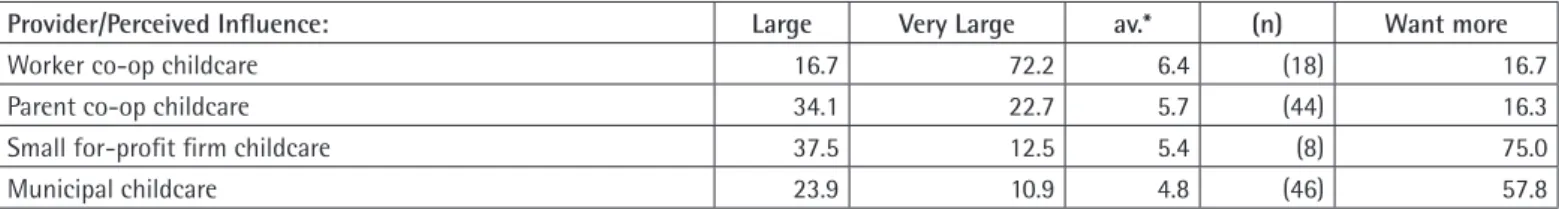

However, participation does not always translate into influence. So, different types of service provider may or may not promote greater client and/or staff influence on the provi-sion and governance of social services. Therefore, Vamstad asked parents and staff at the childcare facilities he studied how much influence they currently had and whether they wanted more. Respondents to the question about their current influence could choose between seven alternatives ranging from “very little” and “little” at the low end to “large” and “very large” at the high end. By contrast, answers to the question about wanting more in-fluence had simple “yes/no” answers. The results presented here only use some of the information about the current level of influence. Only the most frequent categories at the high end of the scale of influence are included in the two tables below. Ta-ble 1 reports parents’ influence and their desire for more, while Table 2 expresses the staff’s influence and its desire for more.

2 The TSFEPS Project, Changing Family Structures and Social Policy: Childcare Services as Sources of Social Cohesion, took place in eight European

countries between 2002-04. They were: Belgium, Bulgaria, England, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Sweden. See www.emes.net for more details and the country reports.

Parent influence is greatest in parent co-ops and least in small for-profit firms. This is an expected result, and nearly nine out of ten parents in parent co-ops claim much influence. However, this is twice as many as in municipal services. Half of the parents in worker co-ops also claim much influence, which is also greater than the proportion in municipal childcare. Finally only one out of eight parents claims much influence in small for-profit firms. The differences in influence between types of providers appear substantial.

Turning to their desire for more influence, again we find the expected pattern of answers, which inversely reflect how much influence they currently experience. Very few pa-rents in parent co-ops want more influence, while nearly three out of five do so in small for-profit firms. In between the-se two types come the worker co-ops, where more than one out of four wants more influence, and municipal childcare, where more than one out of three does so. With as many as one-third of the parents wanting more influence in municipal childcare, a solid base exists for increased parent representa-tion in decision-making. Thus, it is not merely a quesrepresenta-tion of selective choice between various providers, where the more interested parents choose the more demanding, participative forms of childcare, while the more passive ones choose less demanding forms. There appear to be widespread expectations of being able to participate in important decisions concerning their daughter’s or son’s childcare among parents in all types of providers. Perhaps this reflects the spread of the norm of participation from parent co-ops to all public financed welfare services, regardless of the provider. Moreover, the Swedish re-form known as “Councils of Influence” in municipal preschools would benefit greatly by involving many more of these mo-tivated parents, if it were possible to offer them meaningful opportunities to influence decisions. Similarly, worker co-ops

would gain greater legitimacy and trust if they could find ways to involve more parents in a meaningful fashion.

Shifting to the staff of childcare facilities, there were many more who answered that they had much influence, but with some notable differences in the distribution of the fre-quencies, so both the “large” and “very large” categories are included separately in the table above. Again the logically ex-pected pattern of influence can clearly be noted here, where the staff in worker co-ops claims the most influence and the staff in municipal facilities claims the least influence. Nearly nine out of ten staff members claim large or very large influence in worker co-op childcare, while only a third does so in municipal facilities. Nearly three out of five members of staff claim much influence in parent co-ops, while half of them do so in small for-profit firms. Again, the proportion of the staff desiring more influen-ce inversely reflects those claiming much influeninfluen-ce. Few want more influence in either the worker or parent co-ops, while the opposite is true of the staff in the other two types of childcare providers. Nearly three out of five want more influence in mu-nicipal childcare and three out of four do so in small for-profit firms. Thus, there appears to be significant room for greater staff influence in both the latter types of childcare. Greater staff in-fluence could also contribute to improving the work environ-ment in these two types of childcare providers (Pestoff, 2000).

However, one interesting detail is the relatively low pro-portion of staff in parent co-ops wanting more influence. It is almost identical with that found for the staff in worker co-ops. In spite of differences in “ownership”, the striking similarity in the proportion of staff expressing a desire for more influence suggests that there must already be such a high degree of collaboration between the staff and parents in parent co-ops as to eliminate the need for more influence. It seems important to explore this matter closer in future research on third sector social services.

Provider/Perceived Infl uence: Much* av.** (n) Want more

Parent co-op childcare 88.7 5.6 (107) 13.2

Worker co-op childcare 50.0 4.6 (48) 28.3

Municipal childcare 44.9 4.4 (89) 37.3

Small for-profi t fi rm childcare 12.5 3.6 (24) 58.3

Provider/Perceived Infl uence: Large Very Large av.* (n) Want more

Worker co-op childcare 16.7 72.2 6.4 (18) 16.7 Parent co-op childcare 34.1 22.7 5.7 (44) 16.3 Small for-profi t fi rm childcare 37.5 12.5 5.4 (8) 75.0 Municipal childcare 23.9 10.9 4.8 (46) 57.8

Table 1. Perceived and desired user influence, by type of childcare provider.

Source: Adapted from Tables 8.6 and 8.8 in Vamstad (2007). * Combines three categories: “rather large”, “large” and “very large”. ** Average score, based on a scale ranging from 1 to 7, where low scores mean little influence.

Table 2. Perceived and desired staff influence, by type of childcare provider.

Source: Adapted from Tables 8.7 and 8.8 in Vamstad (2007). *Average score, based on a scale ranging from 1 to 7, where low scores mean little influence.

Thus, we found that neither the state nor the market allows for more than marginal or ad hoc participation or in-fluence by parents in the childcare services. More substantial participation in economic or political terms can only be achieved when parents organize themselves collectively to obtain better quality or different kinds of childcare services than either the state or the market can provide. In addition, worker co-ops seem to provide parents with greater influence than either municipal childcare or small private for-profit firms can do. In addition, the staff at worker co-ops obtains maximum influence, resulting in more democratic work places. But the staff at parent co-ops does not express a desire for more influence. Thus both the pa-rent and the worker co-ops appear to maximize staff influence compared to municipal and small for-profit firms, while parent co-ops also maximize user influence.

(ii) Third sector co-production: breaching the ‘glass ceiling’? Co-production not only implies different relations be-tween public authorities and citizens; it also facilitates different levels of citizen participation in the provision of public services. However, participation also depends on the institutional setting or form of provision, i.e., who provides the services. Citizen par-ticipation in public service provision can be distinguished along two main dimensions. For the sake of simplicity only three cate-gories or levels will be considered here, but there can, in fact, be greater differences between them. The first dimension relates to the intensity of relations between the provider and the clients of public services. Here, the intensity of relations between pu-blic authorities and citizens can either be sporadic and distant, intermittent and/or short-term or it can involve intensive and/ or enduring welfare relations. In the former, citizen participation in providing public services involves only distant contacts via the telephone, postal services or e-mail, etc., while in the latter it means direct, daily and repeated face-to-face interaction be-tween providers and citizens over a longer period of time. For example, citizen participation in crime prevention or a neigh-borhood watch, filing their tax forms or filling in postal codes normally only involves sporadic or indirect contacts between the citizens and authorities. Face-to-face interactions for a short duration or intermittent contacts are characteristic of partici-pation in public job training courses or maintenance programs for public housing that involve resident participation in some aspects (Alford, 2002). By contrast, citizen participation in the management and maintenance of public financed preschool or elementary school services involves repeated long-term con-tacts. This places them in the position of being active subjects in the provision of such services, not merely the passive objects of public policy (Pestoff, 2008c). Here they can both influence the development and help decide about the future of the services provided. The same is true of other enduring social services.

Similarly, the level of citizen participation in the provi-sion of public services can either be low, medium or high. By combining these two dimensions we can derive a three by three table with nine cells. However, not all of them are readily evident

in the real world or found in the literature on co-production. Moreover, an additional or third dimension needs to be included and made explicit--the degree of civil society involvement in the provision of public services. This clearly reflects the form of citizen participation, i.e., organized collective action, individual or group participation and individual or group compliance. This figure is depicted in Pestoff (2008b).

In general, we can expect to find a trend where increasing intensity of relations between public authorities and citizens in the provision of public services leads to increased citizen parti-cipation. Sporadic and distant relations imply low participation levels, while enduring social services will result in greater parti-cipation. However, when it comes to providing intensive and/or enduring welfare services, two distinct patterns can be found in the literature. First, a high level of citizen participation is noted for the third sector provision, since it is based on collective ac-tion and direct citizen participaac-tion. Parent associaac-tions or co-op preschool services in France, Germany and Sweden illustrate this. Second, more limited citizen participation is noted for the public provision of enduring social services. It usually focuses on public interactions with individual citizens and/or user councils. Citizens are allowed to participate sporadically or in a limited ad hoc fashion, like parents contributing to the Christmas or Spring Party in municipal preschool services. But they are seldom given the opportunity to play a major role in, to take charge of the service provision, or given decision-making rights or responsibi-lity for the economy of the service provision.

This creates a ‘glass ceiling’ for citizen participation in public services that limits citizens to playing a more passive role as service users who can perhaps make some demands on the public sector, but who have little influence, make few, if any, decisions and take little responsibility for implementing public policy. Thus, it might be possible to speak of two types of co-production: ‘heavy’ co-production and ‘light’ co-production. The space allotted to citizens in the latter is too restricted to make participation very meaningful or democratic. ‘Heavy’ co-production is only possible when citizens are engaged in orga-nized collective groups where they can reasonably achieve some semblance of direct democratic control over the provision of publicly financed services via democratic decision-making as a member of such service organizations. A similar argument can be made concerning user participation in for-profit firms provi-ding welfare services.

We also note that service delivery takes quite different forms in preschool services. Most preschool services studied here fall into the top-down category in terms of style of service provision. There are few possibilities for parents to directly in-fluence decision-making in such services. This normally includes both municipal preschool services and for-profit firms providing preschool services. Perhaps this is logical from the perspective of municipal governments. They are, after all, representative institutions, chosen by the voters in elections every fourth or fifth year. They might consider direct client or user participa-tion in the running of public services for a particular group, like

parents, as a threat both to the representative democracy that they institutionalize and to their own power. It could also be argued that direct participation for a particular group, like pa-rents, would provide the latter with a ‘veto right’ or a ‘second vote’ at the service level. There may also be professional resis-tance to parent involvement and participation, including some misunderstanding about the extent of such client involvement and responsibilities, i.e., whether it concerns core or comple-mentary activities.

The logic of direct user participation is also foreign to private for-profit providers. Exit, rather than voice, provides the medium of communication in markets, where parents are seen as consumers. So, this logic also curtails most types of direct user participation. Only the parent cooperative services clear-ly fall into the bottom-up category that facilitates ‘heavy’ co-production. Here we find the clearest examples of New Public Governance, where parents are directly involved in the running of their daughter’s and/or son’s preschool center in terms of being responsible for the maintenance, management, etc. of the preschool facility. They also participate in the decision-making of the facility, as members and ‘owners’ of the facility. Howe-ver, both these comparative studies of preschool services also illustrate the co-existence of several different layers of public administration regimes in the same sector and country, as Har-tley and the Denhartds suggested. In Sweden, for example, most preschool services are provided by municipalities in a traditional top-down public administrative fashion, which may facilitate ‘light’ co-production. Private for-profit preschool services seem inspired by ideas of greater consumer choice related to NPM.

It should, however, be clearly noted that not all third sector organizations can automatically be equated with greater client participation. Whether or not they are depends primari-ly on their own internal decision-making rules. Many nonprofit organizations are not governed in a fashion that promotes the participation of either their volunteers or clients. Most charities and foundations are run by a board of executives that is appoin-ted by key stakeholders, rather than elecappoin-ted by their members or clients. Very few such organizations can be found among provi-ders of preschool services in Sweden. However, social enterprises in Europe usually include representatives of most or all major stakeholder groups in their internal decision-making structures, and they are often governed as multi-stakeholder organizations. In fact, participation of key stakeholders and democratic deci-sion-making structures are two of the core social criteria applied by the European EMES Research Network to define and delimit social enterprises (see www.emes.net for more information).

Summary and conclusions:

crowding-in and crowding-out?

In sum, after introducing the distinction between tra-ditional public administration, New Public Management and New Public Governance, we explored two comparative studies

of parent participation in childcare in Europe. We found that there are four kinds or dimensions of parent participation in the provision of publicly financed social services. They are economic, political, social, and service specific participation. In the Swedish study, parent participation was clearly the greatest in all four of these dimensions in parent co-op preschool services. Then the influence of both parents and the staff was compared in four types of service providers: parent co-ops, worker co-ops, muni-cipal services and small private for-profit firms in Sweden. Both the parents and the staff of parent and worker co-ops claim more influence than those of either the municipal services or for-profit firms. Thus, we concluded that neither the state nor the market allow for more than marginal or ad hoc participa-tion of parents in the preschool services. More substantial par-ticipation in economic or political terms can only be achieved when parents organize themselves collectively to obtain better quality or different kinds of preschool services than either the state or the market can provide. In addition, worker co-ops seem to provide parents with greater influence than either municipal preschool services or small private for-profit firms can do, and the staff at worker co-ops obtains maximum influence, resulting in more democratic work places.

Both public services and small for-profit firms demonstrate the existence of a ‘glass ceiling’ for the participation of citizens as clients of enduring welfare services. Evidence also suggests similar limits for staff participation in the public and private for-profit forms of providing enduring social services. Only social enterprises like the small consumer and worker co-ops appear to develop the necessary mechanisms to breach these limits by empowering the clients and/or the staff with democratic rights and influence.

Thus, co-production is a core aspect of New Public Gover-nance and implies greater citizen participation and greater third sector provision of public services. The third sector provision of public services can, in turn, promote greater citizen participa-tion as well as user and staff influence. Third sector provision of social services helps to breach the ‘glass ceiling’ for citizen par-ticipation that otherwise exists in public and for-profit services. These findings can contribute to the development of a policy that promotes democratic governance (Pestoff, 2008b) and em-powered citizenship (Fung, 2004). However, it is important to emphasize the interface between the government, citizens and the third sector and to note that co-production normally takes place in a political context. An individual’s cost/benefit analysis and the decision to cooperate with voluntary efforts are condi-tioned by the structure of political institutions and the facilita-tion provided by politicians. Centralized or highly standardized service delivery tends to make the articulation of demands more costly for citizens and to inhibit governmental responsiveness, while citizen participation seems to fare better in decentralized and less standardized service delivery (Ostrom, 1999).

There are important differences between empty ritu-als and real influence. There is a substantial risk in promoting more citizen participation and co-production in the provision of public services. It can initially result in broad citizen support

and enthusiasm, but if the promise of greater citizen influence remains hollow, if it appears merely to be window dressing, or even worse only manipulation, then it may turn into frustra-tion, cynicism and withdrawal from public pursuits. Empirical research discussed below from parent participation in childcare in Europe shows that there is in fact a ‘glass ceiling’ in partici-pation. Therefore, it is possible to distinguish between ‘heavy’ co-production in third sector services and ‘light’ co-production in public and for-profit services. However, not everyone may be willing and able to engage in ‘heavy’ co-production at the out-set. Some citizens may need more time to develop their political resources and skills, before they are willing to assume more res-ponsibility. While the difference between levels of participation may appear controversial, and greater citizen participation may cause some tensions with the professional public service provi-ders, this is to be expected in political processes. Nor will citizens be willing to engage in co-production in many types of public service. Citizens are not like a jack-in-the-box, just waiting for someone to push a button or latch to release their potential engagement in co-production. They will pick and choose when and where to participate according to their own preferences. The importance or salience of a particular service to them and/ or their loved ones will help to trigger their willingness to par-ticipate. In addition the facility or hurdles that they meet when they attempt to participate will serve to encourage or discoura-ge them to participate in co-production.

The way in which the third sector can deliver services and have an impact on society is both related to the global forces of marketization and privatization, on the one hand, and the expe-rimentation with new forms of citizen participation, co-produc-tion and collective soluco-produc-tions to social problems, on the other. In Europe many welfare states experienced extensive change star-ting in the early 1980s and will likely face even greater changes in the next 10 to 20 years in terms of providing welfare services. The growing division between financing and delivery of welfa-re services is becoming mowelfa-re appawelfa-rent. Ideological clashes over the future of the welfare state began with the appearance of neo-liberalism and New Public Management (NPM). At the same time the alternative provision of welfare services was marginal in some countries, usually only found in specialized niches. Ho-wever, by the first years of the 21st century it had grown consi-derably, with a varying mix of for-profit firms and third sector providers in different social service areas and countries.

A continued public monopoly of the provision of welfare services seems therefore highly unlikely or ruled out by domestic political circumstances in most European countries. Thus, there appears to be two starkly different scenarios or trajectories for the future of the welfare state in Europe: either rampant pri-vatization, with accelerated NPM, or the growth of New Public Governance (NPG), with greater welfare pluralism and more co-production. The latter scenario would include a major role for the third sector and the social economy, as an alternative to both public and private for-profit providers of welfare services. These two alternatives are sketched by Figure 1.

A public administration regime can ‘crowd-out’ certain behaviors and ‘crowd-in’ others in the population. For example, a welfare reform policy inspired by NPM that emphasizes eco-nomically rational individuals who maximize their utilities and provides them with material incentives to change their behavior tends to play down values of reciprocity and solidarity, collec-tive action, co-production and third sector provision of welfare services. By contrast, one that emphasizes mutual benefit and reciprocity will promote public services that are “[...] truly owned by the citizens they serve and the staff on whose service and innovation they rely” (HM Government, 2010).

Moreover, one-sided emphasis by many European go-vernments either on the state maintaining most responsibility for providing social services or turning most of them over to the market will hamper the development of co-production and democratic governance. The state can ‘crowd-out’ certain beha-viors and ‘crowd-in’ others in the population. A favorable regime and favorable legislation are necessary for promoting greater co-production and third sector provision of welfare services. Only co-production and greater welfare pluralism can promo-te New Public Governance and more democratic governance of social services.

References

ALFORD, J. 2002. Why do Public Sector Clients Co-Produce? Towards a Contingency Theory. Administration & Society, 34(1):32-56.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0095399702034001004

BOVAIRD, T. 2007. Beyond Engagement and Participation: User and Com-munity Co-Production of Public Services. Public Administration Review,

67(5):846-860. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00773.x

CALABRÒ, A. 2010. Governance Structures and Mechanisms in Public Service Organizations – A Review and Research Agenda. In: A. CALA-BRÒ, Governance Structures and Mechanisms in Public Service

Organi-Figure 1. Development of the European Welfare State, ca. 1980-2030.

zations: Theories, Evidence and Future Directions. Rome, Italy. Ph.D.

Dissertation. University of Rome Tor Vergata, p. 1-31.

DENHARDT, J.V.; DENHARDT, R.B. 2008. The Now Public Service: Serving,

not Steering. Armok/New York/London, M.E. Scharpe, 198 p.

FUNG, A. 2004. Empowered Participation: Reinventing Urban

Democ-racy. Princeton, Princeton University Press, 278 p.

FUNG, A.; WRIGHT, E.O. 2003. Deepening Democracy: Institutional

In-novations in Empowered Participatory Governance. London, Verso, 310 p.

GBIKPI, B.; GROTE, J.R. 2002. Introduction. In: B. GBIKPI; J.R. GROTE (eds.), Participatory Governance: Political and Social Implications. Leske/Budrick, Opladen.

GIDDENS, A. 1998. The Third Way – The Renewal of Social Democracy. Cambridge, Polity Press, 166 p.

HARTLEY, J. 2005. Innovation in Governance and Public Services: Past and Present. Public Money & Management, 25(1):27-34.

HIRST, P. 1994. Associative Democracy: New Forms of Economic and

Social Governance. Cambridge, Polity Press, 222 p.

HIRST, P. 2002. Democracy and Governance. In: J. PIERRE (ed.), Debating

Governance, Authority, Steering and Democracy. Oxford, Oxford

Uni-versity Press.

HM GOVERNMENT. 2010. Mutual Benefit: Giving People Power over

Public Services. Available at:

http://www.hmg.gov.uk/media/60217/mu-tuals.pdf Acessed on: May 16, 2011.

JOHANSSON, H.; HVIDEN, B. 2010. Towards a Post-Marshallian

Frame-work for the Analysis of Social Citizenship. Oslo & Malmo, [s.n.].

MILLER, D. 2000. Citizenship and National Identity. Cambridge, Polity Press, 216 p.

OSBORNE, S. 2006. The New Public Governance. Public Management

Review, 8(3):377-387. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14719030600853022

OSBORNE, S.P. (ed.). 2010. The New Public Governance? Emerging

Per-spectives on the Theory and Practice of Public Governance. London/

New York, Routledge, 431 p.

OSTROM, E. 1999. Crossing the Great Divide: Coproduction, Synergy, and Development. In: M.D. McGINNIS (ed.), Polycentric Governance

and Development: Readings from the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, Chapter 15.

OSTROM, V. 2008 [1973]. The Intellectual Crisis in American Public

Ad-ministration. 3rd ed., Tuscaloosa, University of Alabama Press, 230 p.

OSTROM, V.; OSTROM, E. 1999. Public Choice: A Different Approach to the Study of Public Administration. In: Michael D. McGINNIS (Ed.),

Polycentric Governance and Institutions: Readings from the Workshop

in Political Theory and Policy Analysis. Ann Arbor, MI, Univ. of Michigan

Press, chapter 1.

PARKS, R.B.; BAKER, P.C.; KISER, L.; OAKERSON, R.; OSTROM, E.; OS-TROM, V.; PERCY, S.L.; VANDIVOT, M.B.; WHITAKER, G.; WILSON, R. 1999 [1981]. Consumers as Co-Producers of Public Services: Some Economic and Institutional Considerations. In: M.D. McGINNIS (ed.), Local Public

Economies: Readings from the Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, Chapter 17.

PESTOFF, V., 2000; Enriching Swedish Women’s Work Environment: The Case of Social Enterprises in Day Care. Economic & Industrial

Democ-racy – an International Journal, 21(1):39-70.

PESTOFF, V. 2008a. Co-Production, the Third Sector and Functional Rep-resentation. In: S. OSBORNE (Ed.), The Third Sector in Europe: Prospects

and Challenges. London/New York, Routledge.

PESTOFF, V. 2008b. A Democratic Architecture for the Welfare State:

Promoting Citizen Participation, the Third Sector and Co-production.

London & New York, Routledge.

PESTOFF, V. 2008c. Citizens as Co-Producers of Welfare Services: Pre-school Services in Eight European Countries. In: V. PESTOFF; T. BRAND-SEN (eds.), Co-production: The Third Sector and the Delivery of Public

Services. London/New York, Routledge, Chapter 2.

ROKKAN, S. 1966. Norway: Numerical Democracy and Corporate Plural-ism. In: R. DAHL (ed.), Political Opposition in Western Democracies. New Haven, Yale University Press.

VAMSTAD, J. 2007. Governing Welfare: The Third Sector and the

Chal-lenges to the Swedish Welfare State. Östersund. Ph.D. Thesis.

Mittuni-versitetet, 259 p.

VAN KERSBERGEN, K.; VAN WAARDEN, F. 2004. “Governance” as a Bridge between Disciplines: Cross-disciplinary Inspiration Regarding Shifts in Governance and Problems of Governability, Accountability and Legitimacy. European Journal of Political Research, 43(2):143-171.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2004.00149.x

WESTALL, A. 2011. Revisiting Associative Democracy: How to Get more

Co-operation, Co-ordination and Collaboration into Our Economy, Our Democracy, Our Public Service and Our Lives. [s.l.], Lawrence & Wishart

Available at: http://www.lwbooks.co.uk/ebooks/RevisitingAssociative-Democracy.pdf. Accessed on: May 16, 2011.

Submetido: 28/02/2011 Aceito: 13/04/2011