Length of stay in a neonatal intensive care unit and its association with

low rates of exclusive breastfeeding in very low birth weight infants

CLAUDIA MAIA

1,2, RAILSON BRANDA

˜ O

3, A

ˆ NGELO RONCALLI

4,5, & HE

´ LCIO MARANHA˜O

1,21

Department of Pediatrics, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), Natal, RN, Brazil,2Medicine course of federal university, Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), Natal, RN, Brazil,3Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), Natal, RN, Brazil,4Department of Dentistry, UFRN, Natal, RN, Brazil, and5Postgraduate Program of Dentistry, UFRN, Natal, RN, Brazil

Abstract

Objective. To identify the inpatient maternal and neonatal factors associated to the weaning of very low birth weight (VLBW) infants.

Methods. One hundred nineteen VLBW (51500 g) infants were monitored from July 2005 through August 2006, from birth to the first ambulatory visit after maternity discharge. This maternity unit uses the Kangaroo Method and the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative. Out of 119 VLBW infants monitored until discharge, 88 (75%) returned to the facility, 22 (25%) were on exclusive breastfeeding (EB), and 66 (75%) were weaned (partial breastfeeding or formula feeding).

Results. Univariate analysis found an association between weaning and lower birth weight, longer stays in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and longer hospitalization times, in addition to more prolonged enteral feeding and birth weight recovery period. Logistic regression showed length of NICU stay as being the main determinant of weaning.

Conclusion. The negative repercussion on EB of an extended stay in the NICU is a significant challenge for health professionals to provide more adequate nutrition to VLBW infants.

Keywords:Breastfeeding, preterm, very low birth weight infants, risk factors and weaning

Introduction

The use of maternal milk in preterm infants affords early be-nefits such as providing the recommended source of enteral nutrition, lowering rates of infection, and of necrotizing enterocolitis and having a positive long-term impact on intellectual and neuropsychomotor development [1,2]. These advantages, along with others, support its use in the nutritional management of premature infants both as inpatients and after discharge [3]. However, premature newborns have difficulty maintaining maternal breastfeeding for the recommended period, especially those with very low birth weight (VLBW) [4]. These difficulties arise from prematurity (requiring inten-sive care), longer hospitalization, and delayed onset of oral feeding, all contributing factors to mother–child separation, and, in turn, higher weaning rates [5]. Breastfeeding, however, may be prolonged when the mother intends to nurse and has received instructions for the management of lactation, such as prenatal orientation, early visits to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) to strengthen the mother–child bond as well as early and systematic breastmilk pumping [6]. In summary, low maternal breastfeeding rates are found in VLBW infants, even when inpatient incentive policies are applied [7,8].

The aim of this study was to determine the rate of exclusive breastfeeding in VLBW infants at the first ambulatory follow-up visit follow-up to 7 days after discharge from the maternity unit and to identify the inpatient maternal and neonatal factors

associated with its low incidence. This maternity unit uses the Kangaroo Method (KM) and is part of the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative for following the ten steps to successful breastfeeding recommended by the WHO, which are recognized strategies for stimulating exclusive maternal breastfeeding [9].

Methods

The Janua´rio Cicco Maternity School is a teaching institution affiliated with the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), in Natal, Northeast Brazil. The facility is a referral center for high-risk pregnancies and treats patients exclusively from the National Health System. The maternity unit was awarded the title of Baby Friendly Hospital in 1995 and its multidisciplinary team is periodically trained in the promotion of maternal breastfeeding. The hospital uses the KM for all VLBW infants, which allows the mothers to remain in the institution for the entire hospitalization of her child, that is, during the NICU phase and rooming-in. After hospital discharge, the method recommends ambulatory follow-up as a third stage [10].

This cohort study was composed of all the VLBW infants admitted to the NICU from July 2005 through August 2006. Of the 5258 deliveries during the period, 14.5% were premature (537 weeks) and 3.0% were VLBW (51500 g).

(Received 11 April 2010; revised 16 August 2010; accepted 17 August 2010)

Correspondence: Claudia Rodrigues Souza Maia, Av. Governador Sı´lvio Pedrosa, n8306, apto.:1302, Areia Preta, Natal, RN, Brazil, CEP:59014-100. Tel:þ55-84-88144709 andþ55-84-32154317. Fax:þ55-84-32154317. E-mail: claudiasouzamaia@gmail.com

Newborns with malformations, those who died or were transferred to other services before discharge were excluded. Maternal and newborn data were recorded daily on specific charts during the entire hospital stay and at the first post-discharge consultation.

During hospitalization, the guidelines of the facility recommend that the multiprofessional team encourage the practice of maternal breastfeeding for preterm babies and when this is not possible, the use of milk from the human milk bank. Diet is initiated as soon as possible after clinical and hemodynamic stabilization, using minimum enteral nutrition, and the daily progression of the volume obeys digestive tolerance. The institution does not use formulas or human milk fortifiers during the inpatient period, owing to the absence of an internal protocol, the policy recommended by Baby Friendly Hospital and adopted by the facility, as well as the high cost of supplements, nor does it provide milk from the human milk bank to VLBW infants after discharge.

The mothers were informed about the importance of ambulatory follow-up and a scheduled visit up to 1 week after discharge. At this visit, the patients were classified according to the use of exclusive breastfeeding (EB) or weaning. Weaning was defined as infants receiving formula partially (partial breastfeeding) or exclusively.

For statistical analyses, we studied categorical and numer-ical variables to determine EB or weaning. Thew2 test and Fisher’s test were used to analyze categorical variables and the Student’st-test to analyze numerical variables, which followed normal distribution, according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Statistical significance was established asp50.05, and logistic regression was applied for multivariate analysis.

All the mothers were informed about the study proposals and signed a free and informed consent form. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of UFRN (protocol 071/05).

Results

During the study period, 160 VLBW infants were admitted to the NICU. Thirty-two (20%) died, 9 (6%) were transferred to other institutions, and 119 (74%) were discharged using mother’s milk and with no formula prescribed. Of these 119 patients, 88 (75%) returned for a follow-up visit up to 1week after discharge. Only 22 (25%) of these received EB and 66 (75%) were already using formula. Sixty-three of these (71.5%) received maternal milk along with formula and 3 (3.5%) only formula.

Maternal factors such as mean age (in years) (p¼ 0.93), residing or not with the child’s father (p¼ 0.44), location of residence (state capital or countryside) (p ¼ 1.00), mean number of years of schooling (p¼ 0.22), and mean family income (number of minimum monthly wages) (p¼0.63) did not differ between the EB and weaning groups, nor did the number of prenatal visits (5or 6) (p ¼ 0.25) or type of delivery (normal or cesarean) (p ¼ 1.00). No associations were observed between EB and the following conditions: breastfeeding the previous child for more than 4 months (p¼0.65), desire to breastfeed the newborn child (p¼0.74), and onset of pumping 24 h postpartum (p¼0.34).

There was no difference in the occurrence of weaning between the VLBW before and after 32 weeks of gestational age (p¼0.312), between sexes (p¼0.802), and between the small and adequate for gestational age (p¼0.900).

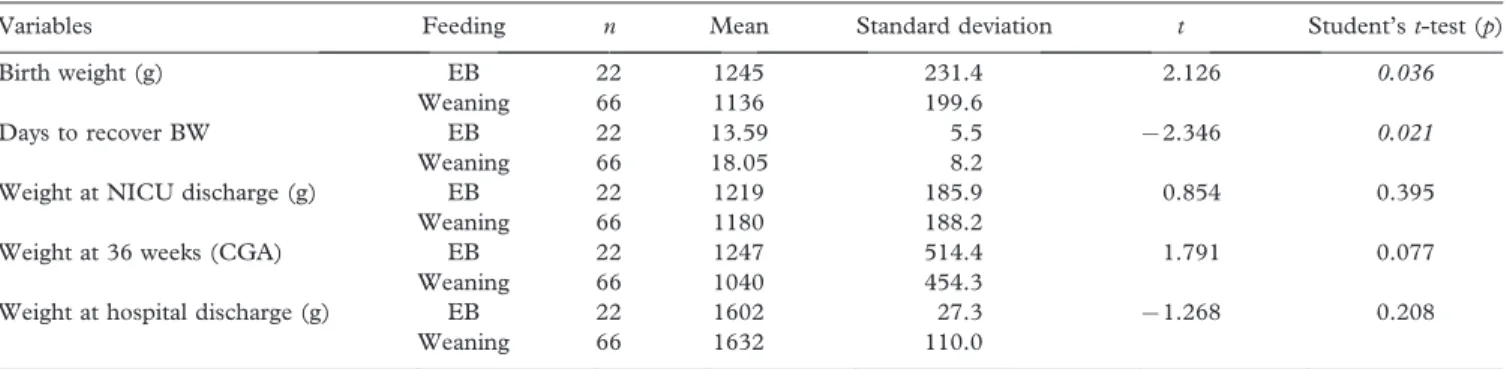

The neonatal variables related to weight (Table I) show an association between lower EB incidence and both lower birth weight and length of time to regain it.

The variables analyzed with respect to perinatal respiratory depression and central nervous system impairment in the infants, such as the need for positive pressure ventilation in the delivery room (p¼1.000), Apgar57 at the 5th min of life (p ¼ 1.000), and the presence of cranial ultrasonography abnormalities (p¼0.673), were not important for weaning.

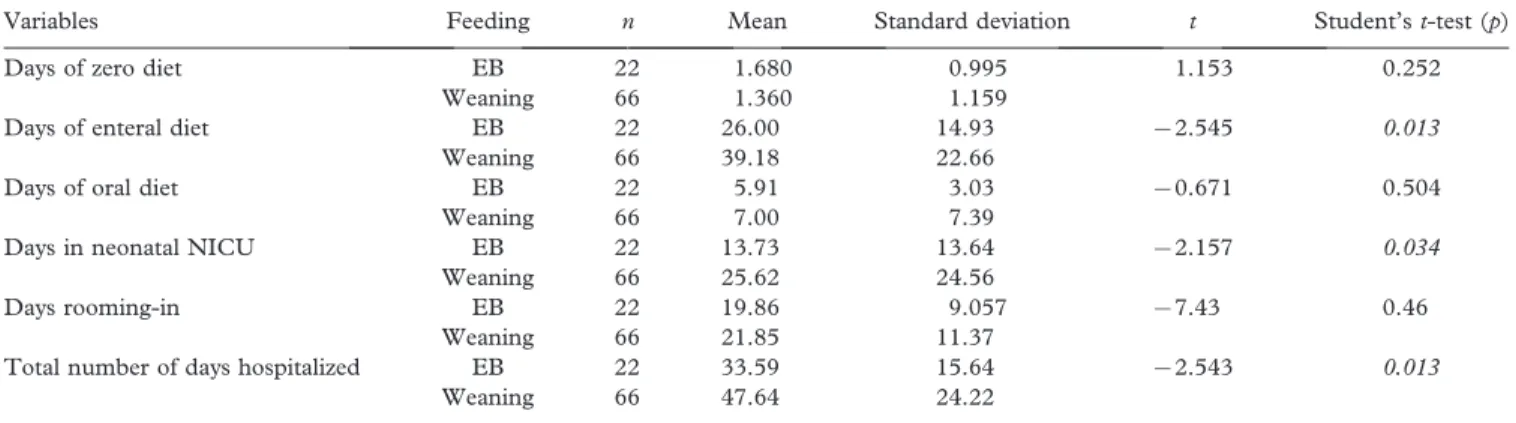

Mean length of time on zero, enteral, and exclusive oral diet was 1.4, 34.3, and 6.5 days, respectively. Table II shows that duration of enteral feeding, longer stay in the NICU, and longer hospitalization were associated with weaning.

Multivariate analysis, using logistic regression, showed birth weight as a confounding variable, and was excluded from the model. Among the variables analyzed, longer stay in the NICU was the determinant of weaning for VLBW infants (Table III).

Discussion

Maintaining EB in VLBW infants continues to pose a challenge. In this study, conducted in a maternity unit that encourages maternal breastfeeding, only 25% practiced it exclusively at the first follow-up visit. Partial or total maternal breastfeeding was observed in 96.5% of the VLBW infants. Breastfeeding rates in VLBW infants vary in the literature, from 29.7% (4) to 61.1% [11]. Thus, the breastfeeding results can be considered quite satisfactory; in contrast to those for exclusive breastfeeding, which is an essential condition for prolonging lactation and, in turn, breastfeeding.

Table I. Exclusive breastfeeding (EB) or weaning at the first ambulatory follow-up visit (up to 7 days after hospital discharge) of 88 VLBW infants according to mean birth weight, number of days to recover birth weight (BW), weight at NICU discharge, weight at 36 weeks corrected gestational age (CGA), and weight at hospital discharge.

Variables Feeding n Mean Standard deviation t Student’st-test (p)

Birth weight (g) EB 22 1245 231.4 2.126 0.036

Weaning 66 1136 199.6

Days to recover BW EB 22 13.59 5.5 72.346 0.021

Weaning 66 18.05 8.2

Weight at NICU discharge (g) EB 22 1219 185.9 0.854 0.395

Weaning 66 1180 188.2

Weight at 36 weeks (CGA) EB 22 1247 514.4 1.791 0.077

Weaning 66 1040 454.3

Weight at hospital discharge (g) EB 22 1602 27.3 71.268 0.208

Weaning 66 1632 110.0

Numbers in italic signifyp50.05.

In a traditional follow-up, it was observed that only 34% of VLBW infants continued to use maternal milk at 40 weeks corrected gestational age. This study proposed the KM as a good weaning prevention strategy [12]. Nevertheless, in Brazil, maternal breastfeeding rates in VLBW infants using the KM method remain unsatisfactorily low [13]. Regardless of the method applied, intervention studies have obtained conflicting but consistently inadequate results, suggesting that inpatient problems must be better identified to elaborate more specific strategies to promote breastfeeding in this high-risk group [6,7,14,15].

In relation to maternal factors, more maternal breastfeed-ing has been reported in older married mothers with both higher schooling levels and higher incomes [11,12], but none of these were determining factors in the present study. The fact that all of the mothers used the same public health facility and exhibited similar economic conditions and social profiles may explain these findings.

The importance of prenatal follow-up to promote maternal breastfeeding in high-risk newborns is recognized [4,7]. Despite the breastfeeding limitations imposed by the birth of a VLBW infant, the similarity in the number of prenatal visits between the EB and weaned groups raises concern about the quality of these consultations, where the aim is to encourage the use of maternal milk and prevent the factors that interfere with this practice. It should be pointed out that 78% of those who were weaned and 63% of those exclusively breastfeeding made fewer than the minimum of six follow-up visits recommended by the WHO [16].

Factors related to previous breastfeeding and the current breastfeeding proposal did not influence weaning despite the favorable effects found by other authors [17]. On the other hand, Pinelli et al. [6] observed that mothers who exclusively

breastfed were not influenced by intervention strategies, but rather were conditioned by other in-hospital factors. The early onset of postpartum pumping did not differ between groups, but in other studies, not only early onset, but also the frequency and effectiveness of pumping during hospitalization were factors directly related to the success of prolonged breastfeeding [6,11–13].

Although studies demonstrated that birth weight and gestational age are causal factors for lower breastfeeding rates [4,18], the neonatal variables analyzed here showed that lower birth weight had greater impact on breastfeeding than lower gestational age. Moreover, in relation to ponderal assessment, an important aspect was the longer birth weight recovery period in the VLBW infants of the weaning group. Worsening nutritional status during hospitalization causes frequent morbidity in VLBW infants and those most affected have greater breastfeeding difficulties [19]. Growth failure during this initial period is worrisome and is likely related, among other factors, to the hospital’s policy of not fortifying human milk.

More prolonged enteral feeding time was a contributing factor for weaning. The immaturity of these newborns leads to delayed onset of breast sucking and the need for enteral feeding, factors that contribute to prolonged mother–child separation compromised lactation and shortened duration of breastfeeding [5,6,12].

Multivariate analysis, however, revealed that length of stay in the NICU was the determinant for low EB rates. Kirchner et al. found similar results in VLBW infants monitored between 2000 and 2005 [5]. Longer mother–child separation has been shown to be a negative condition for breastfeeding success, even when the mother rooms in (the kangaroo ward) and takes part in caring for her child in the NICU [20,21].

The current evidence about the nutrition of VLBW infants encourages members of multiprofessional teams to promote EB and identify factors that may favor or hinder this practice [3]. The use of fortified human milk is one of the strategies for maintaining EB. Besides stimulating the use of breast milk, it avoids or minimizes growth failure, a condition considered adverse for such a practice. This knowledge is indispensable to the development of prevention and intervention strategies that are better designed and more effectively implemented, mainly during the critical inpatient phase [14].

Nutritional support for VLBW infants through the ex-clusive use of maternal breast milk in the hospital and after

Table II. Exclusive breastfeeding (EB) or weaning at the first ambulatory follow-up visit (up to 7 days after hospital discharge) of 88 VLBW infants according to mean number of days with zero diet, enteral diet, oral diet, in the NICU, rooming-in and total hospitalization time (NICU þrooming-in).

Variables Feeding n Mean Standard deviation t Student’st-test (p)

Days of zero diet EB 22 1.680 0.995 1.153 0.252

Weaning 66 1.360 1.159

Days of enteral diet EB 22 26.00 14.93 72.545 0.013

Weaning 66 39.18 22.66

Days of oral diet EB 22 5.91 3.03 70.671 0.504

Weaning 66 7.00 7.39

Days in neonatal NICU EB 22 13.73 13.64 72.157 0.034

Weaning 66 25.62 24.56

Days rooming-in EB 22 19.86 9.057 77.43 0.46

Weaning 66 21.85 11.37

Total number of days hospitalized EB 22 33.59 15.64 72.543 0.013

Weaning 66 47.64 24.22

Numbers in italic signifyp50.05.

Table III. Multivariate analysis of the variables selected by bivariate analysis: number of days in the NICU, of enteral diet and to recover birth weight (BW).

Variables p

Adjusted odds ratio

Confidence interval (95%)

Days of NICU 0.032 5.778 1.16–28.774

discharge remains a challenge for multiprofessional teams, which must become aware of the risk factors, especially a prolonged stay in the NICU, that compromise this practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the entire multiprofessional team that provides newborn care at Janua´rio Cicco Maternity School and the Heriberto Bezerra Pediatric Hospital at UFRN, in addition to the Department of Pediatrics and Postgraduate Program of Health Sciences at UFRN.

Declaration of interest:The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

1. Vohr BR, Poindexter BB, Dusick AM, McKinley LT, Higgins RD, Langer JC, Poole WK; NICHD. Persistent beneficial effects of breast milk ingested in the neonatal intensive care unit on outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants at 30 months of age. Pediatrics 2007;120:e953–e959.

2. McGuire W, Anthony MY. Donor human milk versus formula for preventing necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants: systematic review. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2003;88:11–14. 3. Griffin IJ, Cooke RJ. Nutrition of preterm infants after hospital

discharge. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2007;45:S195–S203. 4. Lee HC, Gould JB. Factors influencing breast milk versus

formula feeding at discharge for very low birth weight infants in California. J Pediatr 2009;155:657–662.

5. Kirchner L, Jeitler V, Waldho¨r T, Pollak A, Wald M. Long hospitalization is the most important risk factor for early weaning from breast milk in premature babies. Acta Paediatr 2009;98: 981–984.

6. Pinelli J, Atkinson SA, Saigal S. Randomized trial of breastfeeding support in very low-birth-weight infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155:548–553.

7. Bicalho-Mancini PG, Vela´squez-Mele´ndez G. Aleitamento ma-terno exclusive na alta de rece´m-nascidos internados em berc¸a´rio de alto risco e os fatores associados a essa pra´tica. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2004;80:241–248.

8. Merten S, Dratva J, Ackermann-Liebrich U. Do baby-friendly hospitals influence breastfeeding duration on a national level? Pediatrics 2005;116:e702–e708.

9. WHO/UNICEF Innocenti Declaration on the protection, pro-motion and support of breast-feeding. In Meeting ‘‘Breast-feeding in the 1990s: A global initiative’’. Cosponsored by the United States Agency for International Development (AID) and the Swedish International Development Authority (SIDA), 30 July–1 August, Spedale degli Innocenti, Florence, Italy; 1990. 10. Ministe´rio da Sau´ de [homepage internet]. Brası´lia: Normas de

atenc¸a˜o humanizada do rece´m-nascido de baixo peso (Me´todo Canguru). Internet. 2006. Electronic Citation. http://portal. saude.gov.br/saude/. Last accessed 12 November 2003. 11. Boo NY, Jamli FM. Short duration of skin-to-skin contact effects

on growth and breastfeeding. J Paediatr Child Health 2007:43: 831–836.

12. Furman L, Minich N, Hack M. Correlates of lactation in mothers of very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2002:109:57–64. 13. Venaˆncio SI, Almeida H. Me´todo Ma˜e Canguru: aplicac¸a˜o no

Brasil, evideˆncias cientı´ficas e impacto sobre o aleitamento materno. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2004;80:173–180.

14. Pineda RG, Foss J, Richards L, Pane CA. Breastfeeding changes for VLBW infants in the NICU following staff education. Neonatal Netw 2009;28:311–319.

15. Santoro Junior W, Martinez FE. Effect of intervention on the rates of breastfeeding of very low birth weight newborns. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2007;83:541–546.

16. Serruya SJ, Cecatti JG, Lago TG. The Brazilian Ministry of Health’s Program for Humanization of Prenatal and Childbirth Care: preliminary results. Cad Sau´ de Pu´ blica 2004;20: doi:10.1590/S0102–311X2004000500022.

17. Sisk PM, Lovelady CA, Dillard RG, Gruber KJ, O’Shea TM. Maternal and infant characteristics associated with human milk feeding in very low birth weight infants. J Hum Lact 2009;25(4):412–419.

18. Penalva O, Schwartzman JS. Descriptive study of tha clinical and nutritional profile and follow-up of premature babies in a Kangaroo Mother Care Program. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2006;82:33–39. 19. Lemons JA, Bauer CR, Oh W, Korones SB, Papile LA, Stoll BJ, Verter J, Temprosa M, Wright LL, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Very low birth weight. Outcomes of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 2001;107.

20. Hallbauer U, Grobler JM, Niemand I. Factors influencing a mother’s choice of feeding after discharge of her baby from a neonatal unit. S Afr Med J 2002;92:634–637.

21. Dall’Oglio I, Salvatori G, Bonci E, Nantini B, D’Agostino G, Dotta A. Breastfeeding promotion in neonatal intensive care unit: impact of a new program toward a BFHI for high-risk infants. Acta Paediatr 2007;96:1626–1631.