FELIPE ZAMBALDI

THE BRAZILIAN CREDIT MARKET FOR SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED FIRMS:

an adaptive marketing approach

THE BRAZILIAN CREDIT MARKET FOR SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED FIRMS:

an adaptive marketing approach

Tese apresentada à Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getulio Vargas, como requisito para obtenção do título de Doutor em Administração de Empresas.

Campo de Conhecimento: Macro-Marketing

Orientador: Prof. Dr. Francisco Aranha

adaptive marketing approach / Felipe Zambaldi. - 2008.

231 f.

Orientador: Francisco Aranha.

Tese (doutorado) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo.

1. Pequenas e médias empresas – Brasil Financiamento. 2. Créditos Brasil. 3. Custos de transação. I. Aranha, Francisco. II. Tese (doutorado) -Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. III. Título.

THE BRAZILIAN CREDIT MARKET FOR SMALL AND MEDIUM-SIZED FIRMS:

an adaptive marketing approach

Tese apresentada à Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getulio Vargas, como requisito para obtenção do título de Doutor em Administração de Empresas. Campo de Conhecimento:

Macro-Marketing Data de aprovação:

____/____/_______ Banca examinadora:

__________________________________ Prof. Dr. Francisco Aranha (orientador) FGV-EAESP

__________________________________ Profa. Dra. Inês Pereira

FGV-EAESP

__________________________________ Prof. Dr. George Avelino Filho

FGV-EAESP

__________________________________ Profa. Dra. Lúcia Pereira Barroso

IME-USP

__________________________________ Prof. Dr. Leonardo Pagano

I would like to thank people and institutions that have helped me during my doctoral studies. Professor Francisco Aranha, my advisor, who has always been very dedicated and supportive, having motivated me from the very beginning. I appreciate all his efforts to transmit his knowledge to me, all his reviews of my work, and all the results he has helped me to achieve over these years. This work surely owes much to his contribution.

Professor Hedibert Lopes, who supervised me as a visiting student in the Econometrics and Statistics Department of the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business. I thank him for his friendship and dedication, and for all the methodological advice he gave me.

Professors Inês Pereira, Lúcia Barroso, George Avelino and Leonardo Pagano, for being panel members and for the advice they provided me.

Professors Wilton de Oliveira Bussab, André Samartini and Eduardo Diniz, for their participation and contribution in our research group on Low Income Studies. Professor Fernando Garcia, for the suggestion of quantifying the transaction costs of lending to small firms by means of a binary response regression model.

My research colleagues Mateus Ponchio, Eduardo Francisco, Ana Moura and Plínio Bernardi, for their friendship and teamwork. My good friend Ricardo Politi, for his companionship and for the academic work we have developed together. André Mascarenhas, who encouraged me to apply for the Doctoral Program at FGV-EAESP. And many other course colleagues, namely Rafael Goldszmidt, Igor Tasic, Maurício Serafim, Antônio Gelis, Rebeca Chu, and Selim Rabia, who have been incredibly supportive over these years.

My wife, Carol, my parents, Leila and Luiz, and all my family, for their love, understanding, and for believing in my dream.

Neste trabalho, o mercado brasileiro de crédito para pequenas e médias empresas (PMEs) é analisado sob a perspectiva do marketing adaptativo, em que se assume que atividades mercadológicas como segmentação, gestão de relacionamento com clientes, apreçamento e desenvolvimento de produtos, são determinadas pela utilidade obtida por agentes de mercado ao atenderem a demanda. Identifica-se que a existência de assimetria de informações e de custos de transação limita e direciona as atividades de marketing no mercado estudado.

A partir de uma amostra com 65.535 propostas de crédito, recebidas e avaliadas por um grande banco brasileiro entre janeiro de 2004 e setembro de 2006, estima-se a utilidade do banco em operações de crédito. Adicionalmente, 17.149 transações de empréstimos concedidos pelo banco ao segmento de pequenas empresas entre abril de 2006 e março de 2007, são investigadas. Finalmente, um conjunto de dados com 1,636 registros obtidos pela junção das bases de dados de propostas e de transações mencionados, é analisado em termos das relações entre taxas de juros e os totais de cobertura oferecidas por meio de garantias de crédito.

Os resultados revelam a existência de um ambiente de marketing adaptativo, em que os pequenos tomadores de crédito produtivo são racionados, e aceitam pagar taxas de juros mais elevadas do que outros segmentos. Produtos de créditos baseados em garantias líquidas e com altas taxas de juros são desenvolvidos para suprir de maneira oportuna este segmento racionado de pequenas empresas. Ademais, a utilidade do banco em operações de crédito é afetada pela informação privada que captura ao longo de relacionamentos mantidos com seus cientes.

Os resultados implicam que o sistema de marketing financeiro brasileiro não desempenha papel formativo no desenvolvimento econômico, que seria de fomento ao crédito produtivo por meio de empréstimos a baixo custo para pequenas e médias empresas. Um sistema formativo de

públicas e monetárias de fomento ao crédito; e empreendedores de pequeno e médio porte que necessitem de financiamento externo para seus negócios.

In this work, the Brazilian credit market for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) is analyzed from an adaptive marketing perspective, in which marketing activities such as segmentation, customer relationship management, pricing and product development are determined by the utility that market players get when they satisfy the demand. The existence of information asymmetry and transaction costs is identified to limit and drive marketing initiatives in the studied credit market.

From a sample of 65,535 credit proposals analyzed by a large Brazilian bank from January 2004 to September 2006, the bank’s utility in a credit transaction is studied. Additionally, 17,149 credit transactions provided by the bank to the small business segment from April 2006 to March 2007 are investigated. Finally, a data set with 1,636 registers, obtained from the merge of the mentioned samples of proposals and transactions, is investigated in terms of the relations between interest rates and the collateral committed in credit proposals.

The results reveal the existence of an adaptive marketing environment, in which small business borrowers are credit rationed and accept to pay higher interest rates than other segments. Credit products based on liquid collateral and high interest rates are designed to opportunistically supply this rationed small business segment. Also, the bank’s utility from a credit transaction is affected by the private information it captures along its relationships with customers.

Findings imply that the Brazilian financial marketing system does not perform a formative function in economic development, which would be to foster the demand for productive credit by means of low-priced loans to small and medium-sized enterprises. However, a formative marketing system is not likely to occur in an environment characterized by imperfect information, like the Brazilian credit market.

Keywords: Credit rationing, small and medium-sized enterprises, macromarketing, asymmetric

Figure 2.1 – Interest rate that maximizes the expected return to the bank. ... 43

Figure 2.2 – Optimal interest rate... 44

Figure 2.3 – Optimal level of collateral... 50

Figure 6.1 - Trajectories of the last 1,000 iterations of all parameters in Model 1 ... 155

Figure 6.2 – MCMC diagnostics for the intercept (0) of Model 1... 156

Figure 6.3 -Trajectories of the last 1,000 iterations of all parameters in Model 2 ... 168

Graph 6.1 – Histogram and selected statistics of Annual_Revenue - R$. ... 135 Graph 6.2 – Histogram and selected statistics of Loan_Size –R$ ... 137 Graph 6.3 - Histogram and selected statistics of Collateral_Percentage (%) for the proposals

which included some kind of collateral... 138 Graph 6.4 - Histogram and selected statistics of Collateral_Percentage (%) for the proposals

which include illiquid collateral. ... 139 Graph 6.5 - Histogram and selected statistics of Firm’s_Age (in years) of the sampled proposals

... 141 Graph 6.6 - Histogram and selected statistics of Annual_Interest_Rate (%) of the sampled

transactions ... 143 Graph 6.7 - Histogram and selected statistics of Annual_Revenue (R$) after the merge of the

sampled proposals and transactions... 147 Graph 6.8 - Histogram and selected statistics of Loan_Size (R$) after the merge of the sampled

proposals and transactions... 148 Graph 6.9 - Histogram and selected statistics of Firm’s_Age (in years) after the merged of the

sampled proposals and transactions... 149 Graph 6.10 - Histogram and selected statistics of Annual_Interest_Rate (%) after the merge of the

sampled proposals and transactions... 150 Graph 6.11 - Branch Location residuals of Model 1 in ascending order with 95% confidence

limits. ... 159 Graph 6.12 - Estimated fixed effects of collateral on the bank’s utility in credit proposals for both

illiquid_collateral (%) and liquid_collateral (%) ... 162 Graph 6.13 - Estimated fixed effects of customer’s annual revenue (R$) on the bank’s utility for

Graph 6.15 - Branch Location residuals in ascending order with 95% confidence limits for Model 2 ... 171 Graph 6.16 - Fixed Effect of Annual_revenue (R$) on the customer’s utility when demanding a

discount of receivables ... 172 Graph 6.17 - Fixed Effect of Firm’s_age (in years) on the customer’s utility when demanding a

discount of receivables ... 173 Graph 6.18 - Fixed Effect of Loan_size (R$) on the customer’s utility when demanding a

Exhibit 2.1 – Summary of the Formulated Propositions ... 69

Exhibit 4.1 – Methodological Summary... 98

Exhibit 6.1 - Summary of results... 179

Quadro 8.1 – Sumário metodológico... 204

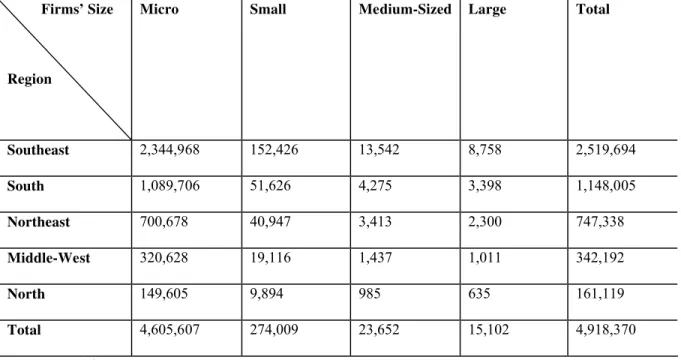

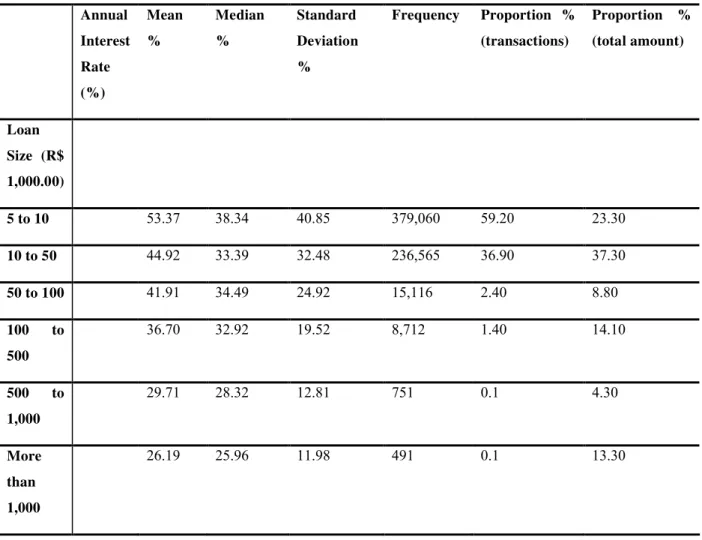

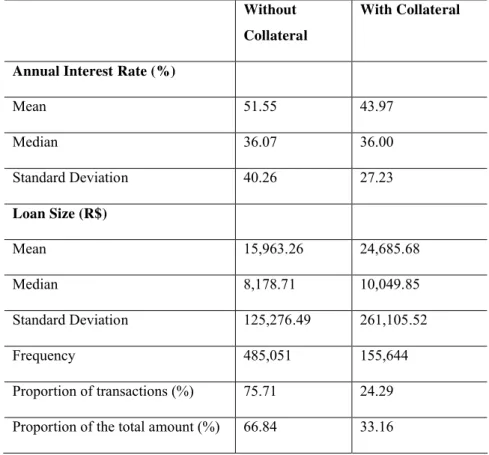

Table 3.1 – Number of formal enterprises in geographic regions in Brazil, 2002 ... 74 Table 3.2 – Annual interest rates (%) per loan size (R$) of operations contracted in Brazil in May 2004 ... 76 Table 3.3 – Annual interest rates (%) and Loan Sizes (R$) of credit operations of May 2004,

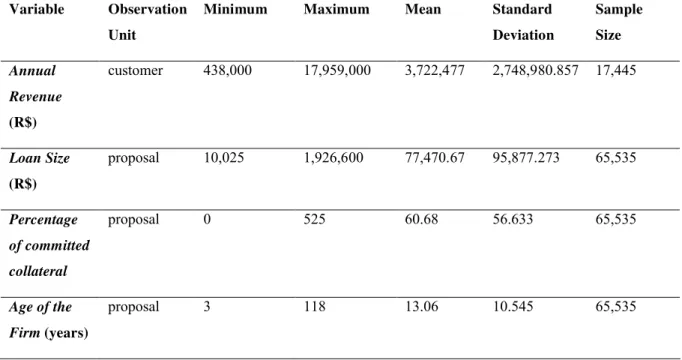

covered with collateral and without collateral... 77 Table 3.4 – Annual Interest rates (%) for different types of productive credit products in Brazil in May 2004... 78 Table 3.5 – Annual interest rates (%) and loans sizes (R$) per firms’ size in credit transactions in May 2004... 79 Table 6.1 - Geographic distribution of the sampled proposals... 132 Table 6.2 – Descriptive statistics of the main continuous variables of the sampled proposals... 133 Table 6.3 - Mode and median of the main continuous variables of the sampled proposals... 134 Table 6.4 – Descriptive statistics of Collateral_Percentage for the whole sample; for proposals

including liquid collateral; and for proposals including illiquid collateral, respectively ... 140 Table 6.5 - Geographic distribution of the sampled transactions ... 142 Table 6.6 – Geographic distribution of transactions resulting from the merge of sampled

proposals and transactions... 144 Table 6.7 - Descriptive Statistics of the main continuous variables after the merge of the sampled proposals and transactions... 145 Table 6.8 - Mode and Median of the main continuous variables after the merge of the sampled

Table 6.13 - Parameters Estimated in alternative Model 2, with sub-sample of proposals... 175

Table 6.14 - Pearson Correlations between annual_revenue, firms’_age, collateral_percentage, and annual_interest_rate... 176

Table 6.15 - Descriptive Statistics of Annual_interest_rate for each category of collateral... 177

Table 6.16 - One-way ANOVA results for Annual_interest_rate (%) by Collateral_type. ... 177

Table 6.17 - Bonferroni intervals of the One-way ANOVA for Annual_interest_rate (%) by Collateral_type. ... 178

Tabela 8.1 – Estatísticas descritivas das principais variáveis contínuas das propostas amostradas ... 210

Tabela 8.2 - Estatísticas descritivas das principais variáveis contínuas das transações após junção com variáveis de propostas disponíveis ... 211

Tabela 8.3 – Parâmetros estimados para o Modelo 1 ... 214

Tabela 8.4 – Parâmetros estimados para o Modelo 2 ... 218

Tabela 8.5 - Estatísticas descritivas da taxa_de_juros_anual por tipo de garantia... 220

1 INTRODUCTION ...21

2 LITERATURE REVIEW ... 26

2.1 MARKETING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT... 27

2.1.1 Adaptive Marketing ... 28

2.1.2 Formative Marketing... 29

2.1.3 Marketing, Economic Development, and the Financial System... 30

2.2 INFORMATION ECONOMICS... 31

2.2.1 The Economics of Transaction Costs... 33

2.3 CREDIT MARKETS AND IMPERFECT INFORMATION... 36

2.3.1 The Effects of Transaction Costs on Credit Constraints ... 38

2.3.2 Regional Economics and Credit Markets ... 40

2.3.3 Imperfect Information, Interest Rates and Credit Rationing ... 41

2.4 LENDING TECHNIQUES... 45

2.4.1 Relationship Banking ... 45

2.4.2 Financial Statement (Ratio) Lending ... 47

2.4.3 Collateralization and Securitization ... 49

2.5 COMPETITION AND PRICE IN CREDIT MARKETS... 52

2.6 THE ADAPTIVE MARKETING FUNCTION OF CREDIT MARKETS WITH IMPERFECT INFORMATION... 57

2.6.1 Segmentation... 57

2.6.2 Pricing ... 59

2.6.3 Product Development... 60

2.6.4 Customer Relationship Management ... 61

2.7 LITERATURE REVIEW SUMMARY... 61

2.8 RESEARCH PROBLEM... 66

2.8.1 Research Hypotheses ... 67

3 RESEARCH CONTEXT ...69

3.1 RESEARCH UNIVERSE... 72

3.1.1 Research Object ... 80

4 METHODOLOGY ...81

4.1 QUALITATIVE INTERVIEW... 82

4.1.1 Choosing the Respondent... 83

4.2 QUANTITATIVE TECHNIQUES... 87

4.2.1 Discrete Choice Models ... 87

4.2.2 Hierarchical Models ... 90

4.2.3 Bayesian and Classical Approaches to Statistical Inference ... 92

4.2.4 Additional Techniques ... 96

4.3 METHODOLOGICAL SUMMARY... 97

5 QUALITATIVE INTERVIEW STUDY...99

5.1 QUALITATIVE DATA... 99

5.1.1 The Process of Conceding Productive Credit... 99

5.1.2 Customer Evaluation ... 111

5.1.3 Product Development... 113

5.1.4 Relationship Banking ... 115

5.1.5 Collateral... 116

5.1.6 Pricing ... 120

5.1.7 Market Trends ... 122

5.2 PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS... 124

6 QUANTITATIVE DATA AND RESULTS ...130

6.1 QUANTITATIVE DATA... 130

6.1.1 The Proposals Data Set ... 131

6.1.2 The Transaction Data Set ... 141

6.1.3 The Merged Data Set ... 144

6.2 QUANTITATIVE RESULTS... 150

6.2.1 Model 1: The bank’s decision to perform a credit transaction ... 151

6.2.2 Model 2: Customer’s demand for cash flow management credit products ... 166

6.2.3 The Relations between Interest Rates, Customer’s Revenue, Loan Size, Firm’s Age, and Collateral 175 6.3 RESULTS SUMMARY... 178

7 CONCLUSIONS ...180

7.1 LIMITATIONS AND POSSIBILITIES FOR FUTURE STUDIES... 184

8 SÍNTESE DO ESTUDO ...187

8.3 UNIVERSO DE ESTUDO... 198

8.3.1 Objeto de Estudo ... 199

8.4 METODOLOGIA... 200

8.4.1 Metodologia Qualitativa... 201

8.4.2 Metodologia Quantitativa... 202

8.4.3 Sumário Metodológico... 203

8.5 DADOS E RESULTADOS... 204

8.5.1 Resultados da Entrevista ... 205

8.5.2 Análise Quantitativa... 208

8.6 CONCLUSÕES, LIMITAÇÕES E POSSIBILIDADES DE ESTUDOS FUTUROS... 221

1 INTRODUCTION

This study is in the domains of small business economics and credit rationing, concepts which frequently appear in the literature on development economics, information economics, and transactions costs. It investigates the effects of asymmetric information on the credit supply to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), specifically related to the development of credit products, pricing, customer’s prospecting, market segmentation, and customer’s relationship management. Therefore, this work is also in the domains of macromarketing, a research field in which objects include the relations between marketing and economic development (REDDY; CAMPBELL, 1994).

Small businesses are known to have a great potential for market development and managerial innovation (SCHUMPETER, 1961). In Brazil, more than 99% of the employers were micro and small firms in 2002, supplying about 53% of the formal jobs in the country (SEBRAE, 2005a), and contributing to approximately 25% of the Brazilian Gross Internal Product (KOTESKI, 2004).

However, only about 11% to 14% of the Brazilian micro and small enterprises contracted credit to fund their fixed investment and to manage their cash flows in 2004 (see SEBRAE, 2005b), even though contracting credit is fundamental to the prosperity of small businesses (LUCAS, 1988).

In 2006, there has been growth of about 25%, in reference to 2005, of the credit supplied to small and middle size enterprises (SMEs) in Brazil (BILLI; VIEIRA, 2007). This growth may be attributed to the servicing of previously credit rationed small business borrowers, who accepted to pay higher interest rates than those prevailing in other segments; the large firms count on greater credit supply than the small ones and, therefore, they are able to bargain credit agreements, including the price of money (HERNÁNDEZ-CANOVA; MARTINEZ-SOLANO, 2007).

players get when they satisfy an existing demand, given economic and environmental circumstances (BARTELS, 1981). The adaptive function of marketing in the Brazilian credit industry is characterized in terms of market segmentation, relationship banking, pricing, and product development.

Among the main drivers of the credit supply to productive activities in a market, there are informational issues and their related costs. Because of informational asymmetry, private and public banks usually deny credit to borrowers who are unable to reveal their credit behavior, especially those who operate in complete or partial informality, which is the case of most Brazilian small firms (PINHEIRO; MOURA, 2001).

The rationed segment of small enterprises which cannot provide reliable information about their credit behavior (HERNÁNDEZ-CANOVA; MARTINEZ-SOLANO, 2007) becomes attractive because of its propensity to pay higher interest rates than the rates paid by companies in other segments.

With informational aspects of small business credit behavior being censored to the market, a strategy to cover the lenders position in case of default may be to demand liquid collateral in credit contracts. Liquid collateral are monetary instruments such as credit derivatives and receivables, which are used to cover the loans principal values and are known to practically neutralize default risks (KIMBER, 2004; BOMFIM, 2005), being valuable to the lender.

Liquid collateral differs from the illiquid forms of coverage, such as mortgages, in the sense that illiquid collateral are practically only incentives to the borrowers' payback, that is, they do not have much value to the lender. The higher the amount of liquid collateral in a credit contract, the more effective the transaction is to the lender in terms of risk control. Assuming that small business borrowers are rationed in the market, and therefore accept to pay higher interest rates than other segments, liquid collateral allows banks to charge higher interest rates from small loan borrowers without risk. So, the development of credit products covered by liquid collateral emerges as a marketing strategy to securely satisfy this demand with increases in prices, transferring the borrower’s surplus to the bank.

In this study, the main theoretical propositions of information asymmetry in credit markets are reviewed, and hypotheses about the decision process of a bank when providing credit to small firms are proposed to verify an adaptive function in the Brazilian credit market for SMEs. Then, the research universe is characterized and the applied methods are presented. Hypotheses are tested with the purpose of characterizing the bank’s decisions according to the utility it gets from a credit transaction.

Particularly, it is intended to measure: if small and young firms are more credit rationed than large firms; the effects of collateral on a bank’s utility when a credit transaction is provided; the relations between interest rates and collateral; and the demand pattern for credit products of small firms.

Specifically, the adaptive characteristics of the Brazilian productive credit marketing are investigated by means of two Generalized Hierarchical Liner Models (GHLMs). Both models are developed with a random sample of 65,535 credit proposals, which were submitted to a particular bank by 17,445 different customers in 19 different regions from January 2004 to September 2006; the first model contemplating the decision of the bank to approve or not a credit proposal as a discrete response variable, and the second dealing with the choice of a firm to submit a credit proposal for a short-term credit product or for another credit option.

The parameters of both models are estimated from a Bayesian perspective, by means of a Gibbs sampler. The benefits of performing Bayesian generalized hierarchical linear models are their capacity of capturing the particular contextual effects related to customers’ and regional specificities in this study. Hierarchical models are proper to model panel data structures in which observations are unbalanced at different contexts, and collected in different occasions (LUKE, 2004). Also, Bayesian methods are more effective than classical procedures such as maximum likelihood and its variations when modeling non-linear relations (ZELLNER; ROSSI, 1984). Finally, Bayesian inference brings advantages regarding shrinkage effects on hierarchical regression parameters, especially when there are contextual groups with a very small number of observations (RAUDENBUSH; BRYK, 2002). All of these situations are observed in this study, justifying the choice for Bayesian GHLMs.

collateral is revealed to have an optimal level to financers, identified by means of a non-monotonic relation between the percentage of principal coverage and the bank’s utility when providing a credit contract to a small firm. That result is theoretically consistent with the propositions of Stiglitz and Weiss (1981), which have been the main reference in studies of credit markets with imperfect information for decades.

A particular contribution of this study is the identification of different levels of efficiency of illiquid and liquid collateral. Liquid collateral leads to greater utility of banks in a credit transaction, being less risky. Furthermore, rationed small and new firms, which demand credit products to manage their cash flows, are charged higher interest rates than other firms, even when providing liquid collateral to cover their loans.

The relations between collateral and interest rates are not consensual in the literature; also empirically, collateral and interest rates have been found to be positively and negatively related, depending on different studies (see LEHMANN et al., 2004). In the present research, the relation between collateral and interest rates has been identified to be positive. The interpretation is that, when default risk is reduced by means of effective collateral, the price of credit is determined by the relations between supply and demand, and high interest rates are charged from the rationed small business segment. That conclusion considers the price of credit as explained by microeconomics assumptions that prices are determined by supply and demand, being alternative to the explanation that high interest rates are charged to compensate default risks.

The main conclusions of this study are:

a) the productive credit market in Brazil is segmented according to firms’ sizes and to the publicly available information about credit behavior of borrowers;

b) small and new enterprises are more credit rationed than other firms;

c) small and new firms are more likely to demand credit to manage cash flow than other firms;

e) in the presence of information asymmetry, low-risk credit transactios involving the discount of receivables are more expensive to small firms, because they are the most credit rationed segment in the market.

The results of this work are coherent with the effects of an adaptive marketing function in the Brazilian productive credit market. That implies that the credit marketing system does not perform a formative role, which would be to foster an aggregate demand with low priced services (KAYNAK, 1986) and to reduce transaction and exchange costs (MOYER, 1972; REDDY; CAMPBELL, 1994).

A restrictive and expensive supply of credit to SMEs limits the growth opportunities of small firms; marginal outcomes of capital tend to be significant to small enterprises (LUCAS, 1988). Considering the vast participation of small business in the Brazilian economy (see SEBRAE, 2005a), the knowledge about the nature of productive credit restrictions is very relevant to the country’s economic development.

Findings may be useful to policy makers concerned with small business prosperity and with the regulation of credit markets; for marketing professionals interested in fostering the demand for credit products under a competitive perspective; for researchers focused on the role of marketing in economic development; and for credit bureaus agents committed to provision of credit information to the market.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

In this research, the credit market for small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) in Brazil is analyzed under a marketing perspective, with implications to economic development. The research field that deals with socio-economic impacts of marketing activities is known as macro-marketing (REDDY; CAMPBELL, 1994). The particular macro-macro-marketing issue focused in this study is the analysis of marketing decisions of an economic agent which relates to the economic environment (KAYNAK, 1986).

Marketing activities of small business loan suppliers can be explained by economic theories about the demand for credit and the competitive scenario in which they are embedded. That approach is called adaptive marketing, which states that the marketing function of an economic agent is a response to economic conditions (BARTELS, 1981).

Particularly, in this work, the decisions of a bank about supplying credit transactions to small businesses are analyzed with the tools of information economics, in which informational asymmetry influences the choices of players about contractual relationships, due to adverse selection and moral hazard (MACHO-STADLER; PÉREZ-CASTRILLO, 2001).

So the relations between marketing and economic development are presented as a macro-marketing issue under an adaptive macro-marketing approach. The adaptive macro-marketing function in credit markets with imperfect information is characterized as a result of adverse selection and moral hazard, with the decision of a bank to offer a credit transaction to a small business entrepreneur being the unit of analysis in this study.

It is proposed, therefore, that imperfect information establishes the level of credit rationing and determines competitive standards in credit markets, molding lending techniques and contractual terms of small loans, such as loan securitization and interest rates. Basically, the marketing strategies of the financial sector, namely market segmentation, pricing, product development and customer relationship management (EHRLICH; FANELLI, 2004), are theoretically characterized as responses to transaction costs in credit markets with imperfect information.

2.1 Marketing and Economic Development

According to Reddy and Campbell (1994), effective marketing may lead to economic development. The recognition of the significance of marketing in development processes enables scholars, public policy makers and business professionals to make use of marketing knowledge, skills and techniques to efficiently achieve economic goals. According to Moyer (1972), a marketing system can avoid economic risks by providing adequate information flows and therefore reduce transaction and exchange costs.

Marketing can be defined as a process of planning and executing the development, pricing, promotion and distribution of goods or services, and of generating exchanges to satisfy consumer and organizational needs; this is a micro definition of marketing, because it considers its role within an individual firm (REDDY; CAMPBELL, 1994).

Douglas (1975) postulates that patterns of marketing systems and structures result from the size and organization of firms, managerial attitudes, channel structures, institutional types, and marketing orientation at different stages of the country’s economic development. But a basic problem in marketing theory is to determine the relationship between marketing systems and economic development structures, since there is no consensus about the nature of this relationship (KAYNAK, 1986).

According to Bartels (1981), the marketing activity may act as a catalyst to economic development and simultaneously be a response to economic conditions; so it is difficult to determine whether it plays a leading or a lagging role. The author argues that marketing plays both “adaptive” and “formative” functions in the economic environment; the adaptive function means that marketing activities are consequences of the environmental circumstances, while the formative function implies that the actions of marketing stimulate economic development. Next,

both adaptive and formative functions are separately discussed.

2.1.1 Adaptive Marketing

The adaptive - or determinist - function of marketing follows the perspective according to which the function of marketing is not necessarily to create new demand, but to satisfy a demand that already exists (BARTELS, 1981). The adaptive marketing function is coherent with a passive assumption, in which a change in the marketing system and its influences on economic development occur only if environmental conditions change, what is frequently observed in less developed countries (KAYNAK, 1986). So, in other words, determinists attribute the modifications of marketing systems to environmental changes.

which already exists. In such a scenario, less developed countries should struggle to design high quality and competitively priced products in order to develop an efficient economic environment. Although the adaptive marketing approach to economic development is theoretically consistent and accepted by researchers and marketing professionals, the nature of relationships between marketing systems and economic structures is not consensually defined and, therefore, Kaynak (1986) signals the importance of considering an alternative approach, the formative marketing function, which is described below.

2.1.2 Formative Marketing

The formative – or activist – function of marketing reinforces the perspective in which marketing is the prime mover of exchange activities (BARTELS, 1981); this approach places marketing as a country’s economic development stimulator. According to Kaynak (1986), marketing is not merely passive and adaptive, but it is dynamic, and its function is to foster processes of economic development.

As changes in economic conditions can be attributable to changes in marketing institutions and practices, Kaynak (1986) presents two ways to promote changes in the marketing system in a formative perspective: 1) by means of widespread education of businessmen in marketing principles; and 2) by means of public administration plans and policies for the improvement of the entire marketing activity in the economy.

Considering the mutual influences between marketing and economic development and its controversial relations, a brief discussion of those relations in the context of this research is presented next. The mutual influences of marketing and economics are characterized in terms of their effects and dependences on the financial system with emphasis on the role of credit.

2.1.3 Marketing, Economic Development, and the Financial System

Poor savings and investments are obstacles to effective marketing and economic development. According to Reddy and Campbell (1994), the financial sector should guarantee the availability of credit in the market. General business efficiency stimulates the aggregate demand and is positively affected by the presence of effective capital infrastructures (KAYNAK, 1986). Impediments of capital formation and accumulation are obstacles to the development of an active entrepreneurial class and to investment initiatives (HARTARSKA; GONZALEZ-VEGA, 2006). Among those obstacles, the lack of balance between supply and demand of capital goods may limit economic development.

2.2 Information Economics

Economics of information focus on the development of contracts under asymmetric information (MACHO-STADLER; PÉREZ-CASTRILLO, 2001). A contract is a document that specifies the obligations of its participants and the actions that must be taken under different contingencies (BESANKO et al., 2004). When contracts are developed under asymmetric information, the observed behavior of participants and the level of information available to each party influence the optimal format of the contract (MACHO-STADLER; PÉREZ-CASTRILLO, 2001).

There are basically two types of informational asymmetry: 1) the adverse selection, which occurs when one party has relevant and private information regarding the contracted object before the contract is signed (MILGROM; ROBERTS, 1992); and 2) moral hazard, which occurs when asymmetric information arises after the contract has been signed (KREPS, 2004).

Information economics study optimal contractual formats. According to Macho-Stadler and Pérez-Castrillo (2001), the basic scenario is characterized by the situation in which one party, named the principal, designs and offers a contract to another party, the agent, who studies its terms and decides whether to sign it or not. The agent accepts the contract only when the utility he obtains from it is greater than the utility he would get from not signing it; this utility level is called the agent’s reservation utility. So the principal has most of the bargaining power because she decides on the terms of the agreement. The principal offers a different form of contract to each type of agent, depending on the information she owns. If the agent accepts the contract, and if the contract is effective, he must carry out the stated actions, because such a contract is a reliable promise in which the obligations of both parties are specified for all possible contingencies.

incentives to contract breach, and none of the parties would be willing to assume such a risky agreement.

In a contractual relationship, each player chooses and optimal strategy, assuming that the counterpart will do likewise (KREPS, 2004). The principal offers a contract that maximizes her utility, but not without having first inferred the expected behavior of the agent. If the agent rejects the contract, he will have to choose other opportunities available in the market, what influences his decision. The utility that the external opportunities offer to the agent is called his reservation utility (MACHO-STADLER; PÉREZ-CASTRILLO, 2001).

Usually, one of the parties has more information than the other about relevant aspects of the contractual relationship. The effective identification of these aspects permits better development of contractual forms, creating therefore optimal contracts between principals and agents (BESANKO et al., 2004).

There is a particular branch of information economics which deals with a single contract as the unit of analysis to explain the arrangements which compose the economic system, a branch known as the economics of transaction costs (WILLIAMSON, 1985). It assumes that an economic agent decides to perform or not a transaction according to its utility, which is determined on its turn by the level of risk, uncertainty, and perceived costs of dealing with potential contingencies of the transaction (BESANKO et al., 2004).

2.2.1 The Economics of Transaction Costs

Transaction costs economics focus on the costs faced by organizations to run the economic system, with a single transaction as the basic unit of analysis (WILLIAMSON, 1085). Besanko et al. (2004) state that the concept of "transaction costs" is an effort to explain why and how much of the economic activity takes place without market competitive efficiency.

According to Kreps (2004), many transactions are complex and take time to be completed, because the parties involved in a negotiation have multiple opportunities and face many uncertainties, such as hidden information and moral hazard. They are unable to imagine all possible contingencies that may arise in a transaction, or their consequences, and so they are boundedly rational.

Transaction costs include the time and expenses of negotiating, writing and enforcing contracts, and arise when one or more parties can act opportunistically (WILLIAMSON, 1985; BESANKO et al., 2004); they relate to the adverse consequences of opportunistic behavior and the costs of trying to prevent it (COASE, 1988), and are distinguished between ex ante and ex post costs (WILLIAMSON, 1985).Ex ante costs incur when agreements are drafted and negotiated, while

ex postare the costs of running and monitoring a transaction and the disputes referred to it; since the final outset of some transactions may be unpredictable, the parties adapt their actions as time passes and as circumstances demand it.

However, no economical agent enters a transaction blindly; agents may be very sophisticated when attempting to structure a transaction in a way that leads to efficient adaptation (KREPS, 2004). But, because contract law can reduce opportunism, and not eliminate it (COASE, 1988), incomplete contracting conditions inevitably imply transactions costs.

continuing negotiation (LYONS, 1994). If a relationship is complex, the ability to write complete contracts that safeguard both parties is bounded, frequently leading to renegotiations of contracts and raising transactions costs due to delays or disruptions in the exchanges (KREPS, 2004). Lack of trust is a less tangible, but real, transaction cost; it raises direct costs of negotiations as parties may insist in more formal safeguards (BESANKO et al., 2004). The existence of mutual trust avoids holdups; the greater the level of trust, the less the requirement for costly lawyers and preplanning of contingency actions (KREPS, 2004). Among the several sources of trust are the alignment of interests; the need for continued cooperation; concerns about reputation; and incentives to contract fulfillments by means of sanctions or rewards (BESANKO et al., 2004; MACHO-STADLER; PÉREZ-CASTRILLO, 2001).

Kreps (2004) states that parties are increasingly held up by their trading partners as time passes by and as relationships mature. That happens because parties develop transaction-specific assets that are valuable in the relationship and would be lost if it ends prematurely (WILLIAMSON, 1985). A party which depends on transaction-specific assets is potentially victim of holdup by the counterpart, which may demand onerous terms of trade, but not so onerous that the victim party would forfeit the value of those transaction-specific assets by taking businesses elsewhere (BESANKO et al., 2004).

Kreps (2004) presents three general conditions which would be necessary to eliminate transactions costs: unbounded rationality; simple situations; inexistence of transaction-specific assets. If not for bounded rationality, players would be able to specify all contingencies of a transaction before it was contracted; if not for the complexity of a situation, individuals would be able to draft sufficiently complete contracts; and if not for transaction-specific assets, the parties would be able to determine terms of trade in a perfect competitive market condition.

The author argues that rules, conventions and procedures by which the terms of a transaction are adapted to contingencies are essential in situations of incomplete contracts. Those rules, conventions and procedures, typically include legal rights (COASE, 1988), contractual terms (MACHO-STADLER; PÉREZ-CASTRILLO, 2001), and relationship customization (BESANKO et al., 2004).

1) the less it costs to set up, and the less it takes to achieve its needed adaptations;

2) the more the parties are willing to invest in transaction-specific assets that increase the transaction joint surplus;

3) the more the parties are willing to deal with contingencies with a flexible attitude; 4) the greater the extent to which the adaptations made meet contingencies efficiently.

Long term exchanges need relationship contracting (WILLIMASON, 1985), in which the involved parties are economically independent, but are held up because of their interests, mutual dependency, or the need to maintain their reputation of good trading partners (KREPS, 2004). Nearly every relationship has aspects which should be adjudicated by legal or administrative authorities. These aspects demand reliance on outside authority to interpret the law and contracts. Rationality requires that a third party should be disinterested and equitable, but this is not always true, because of the possibility of corruption. So, the reputation of the arbitrator is relevant in relationship-based contracts (KREPS, 2004).

2.3 Credit Markets and Imperfect Information

The literature on capital market imperfections and their effects on corporate investment comprises studies in which adverse selection, moral hazard, and consequently credit rationing, are frequently analyzed (HYYTINEN; VÄÄNÄNEN, 2006).

The essence of adverse selection theories in credit markets refers to the problem of an external financier being confronted with a pool of firms needing credit, but not being able to distinguish a good firm from a bad firm in terms of solvency. Therefore, the financier can only grant financing at a higher rate, sufficient to compensate losses in case of eventual default (JENSEN; MECKLING, 1976). But this measure results in worsening the pool of firms that demand external finance (STIGLITZ; WEISS, 1981), as it will be discussed later, and credit rationing may be optimal to financiers because of risk (HYYTINEN; VÄÄNÄNEN, 2006).

The essence of moral hazard, on its turn, refers to the problem faced by an external financier when the firm to which financing was granted uses the resources for purposes other then the indicated previously, when it takes decisions that endanger repayment, or when it assumes more risk than would be optimal from the point of view of the financier (STIGLITZ; WEISS, 1981). If firms do not behave diligently, credit rationing may be optimal (BESTER; HELLWIG, 1987). Both adverse selection and moral hazard are complimentary problems (HYYTINEN; VÄÄNÄNEN, 2006); the former can translate into the latter (DIAMOND, 1989; PETERSEN and RAJAN, 1995).

The worse the moral hazard and the adverse selection problems are, the higher the probability that a firm will be financially constrained. Because of credit rationing, a financially constrained firm cannot raise external financing from the capital market. If a firm is financially constrained, it foregoes important investment (HYYTINEN; VÄÄNÄNEN, 2006).

proposition. Hartarska and Gonzalez-Vega (2006) found that young firms in Russia face significant financial constraints. Empirical findings of Audretsch and Elston (2002) suggest that the growth of medium-sized firms is limited by the availability of finance.

Even though it is assumed that the growth of small and medium-sized enterprises is constrained by the availability of finance (AUDRETSCH; ELSTON, 2002; CARPENTER; PETERSEN, 2002; HUBBARD, 1998), little about the origins of financial constraints has been empirically studied, according to Hyytinen and Väänänen, (2006). Economic theory suggests that both adverse selection and moral hazard are the primary sources of frictions in capital markets, what was empirically corroborated by these authors, who also found that adverse selection is more prevalent in the small and medium-sized business credit market than moral hazard. Their results were based on data of the Finnish credit market to small firms.

Hutchinson and Xavier (2006) state that access to finance for SMEs in transition economies should be improved by greater diversification in the range of financial products available to this segment, since access to financing is considered one of the main obstacles to small business development and growth.

Feakins (2004) points out the relevance of bringing decision-making and processing structures into the academic analysis of commercial bank lending and into discussions about the nature of the finance available to SMEs. Hartarska and Gonzalez-Vega (2006) argue that there is limited ability of providers of formal finance to solve problems resulting from asymmetric information in lending to small firms; banks do not know if they are lending to the most profitable firms and usually do not use the entrepreneur’s characteristics in lending decisions. Therefore, there is a lack of innovative lending technologies to meet the needs of small business demand for credit. Also according to these authors (2006), the high information costs of external financing represent obstacles to the formation of capital. Therefore, policies that decrease the cost of external financing are needed to help banks and other financial institutions to acquire information processing capabilities and lending technologies to overcome asymmetric information with cost-effective financial services to small firms.

SCHROOTEN, 2006). Since perfect competition is harmed by asymmetric information, banks should benefit from obtaining information about borrowers (DIAMOND, 1989).

The informational problem effects of credit markets to small businesses are characterized in this study in terms of the contractual forms of credit offered by a bank to small firms. According to the concepts presented so far, lenders decide to provide credit according to their expected returns, previously evaluating the conditions of each credit transaction. So, it is assumed that the supply of credit to small firms is determined by the decisions which take place in the transaction level. Therefore, the credit constraints to small and medium sized enterprises may be addressed as a consequence of transactions costs, what is briefly discussed below.

2.3.1 The Effects of Transaction Costs on Credit Constraints

Under usual conditions, business expansion results in economies of scale, followed by greater return. However, expansion may also produce loss if it is related to risk and transaction costs, resulting in diseconomies of scale (BESANKO et al., 2004). That seems to be the particular case of credit markets with imperfect information. Small firms are more informationally opaque and, therefore, have less access to external funding than larger firms, what makes the credit market unable to resolve problems of asymmetric information and to adequately fund the expansion of small businesses (HARTARSKA; GONZALEZ-VEGA, 2006).

Hyytinen and Väänänen (2006) empirically found that inefficient production of information about solvency of SMEs is related to frictions in the market for small business financing. These findings suggest that imperfections of credit markets can be empirically analyzed as an adverse selection problem characterized as an ex ante transaction cost of credit transactions.

developed and property rights are clearly determined and supported by an effective legal system, transaction costs are reduced and the market tends to be efficient (WILLIAMSON, 1985). Usually, the established and market oriented economies of developed countries count on more effective institutions and property rights than the transition economies of less developed countries.

King and Levine (1993) argue that financial institutions play a role of funding entrepreneurial activity that leads to productivity and growth only if there is a functioning financial market and if property rights are clearly defined and enforced, which is the case of developed countries; these financial conditions and property rights are different from those found in transformation (transition) economies (FEAKINS, 2004). The well functioning of property rights allow players to enforce contractual terms when dealing with transactional contingencies and to verify formal behavior signalization provided by counterparts.

Another theoretically expected effect of transaction costs in credit markets is the holdup problem. If it is assumed that transaction costs limit the supply of credit to small businesses and its expansion, it can also be assumed that the rationed demand for credit tend to raise its equilibrium price (interest rates), which is a natural law of economics (STIGLITZ; WEISS, 1981). Jensen and Meckling (1976) state that, in the presence of transaction costs and asymmetric information, loans are either rationed or available at a premium.

Baas and Schrooten (2006) attest that information about small and medium-sized enterprises is rare and costly for financial intermediaries; the lack of reliable information leads to high interest rates even in a long-term relationship between the borrower and the bank. Small business entrepreneurs who depend on a financier for long-term relationships in a rationed credit market may be held up, because the financier may behave opportunistically by raising interest rates. Even if borrowers show to be good during the long-term credit relationship, they may not have another option to obtain credit in the market, and therefore agree to pay for overpriced continuing loans (SHARPE, 1990). High interest rates, on the other hand, are expected to be followed by a reduction in the demand for credit (BAAS; SCHROOTEN, 2006).

which the financing of SMEs depends on external credit and in which regional and local banks are relatively important. Even so, financial constraints caused by adverse selection are also relevant in credit systems that are more market oriented (AUDRETSCH; ELSTON, 2002; CARPENTER; PETERSEN, 2002).

In fact, the relations between information asymmetry in credit markets and regional economics have not been directly - nor deeply - analyzed by researchers (LEHMANN et al., 2006). On the other hand, factors which are relevant to the discussion of credit risk, such as the birth, growth and death rates of SMEs, have been addressed in studies of regional economics (AUDRETSCH; FELDMANN, 1996). A brief review of some of these studies, which provided useful insights for the development of this research, is presented below.

2.3.2 Regional Economics and Credit Markets

spatial concentration of research and development activities being crucial for the achievement of profitable outputs (AUDRETSCH; FELDMANN, 1996).

Lehmann et al. (2004) state that there is no direct evidence about the determinants of regional credit risk, but that there is indirect evidence of the impact of regional factors on birth, growth and death rates of SMEs, variables which should influence their solvency capacity. The authors argue that growth rates of regional economies influence default risks and consequently access to credit, so more economically developed regions tend to face a larger supply of credit. On the other hand, economically growing regions are characterized by turbulence, with simultaneous high rates of birth and death of firms, what can be explained by intense competition; these conditions may lead to operational difficulties and default.

2.3.3 Imperfect Information, Interest Rates and Credit Rationing

Credit markets with imperfect information share common characteristics regarding interest rates and conditions of credit rationing (STIGLITZ; WEISS, 1981). These markets are theoretically discussed below, in terms of the relationship among asymmetric information, interest rates and credit rationing, in order to further explain techniques and decision processes made by banks when providing credit to small firms.

The main theoretical contributions of information economics about credit rationing and interest rates were introduced by Stiglitz and Weiss in 1981. The authors discuss the existence of rationing of productive credit by analyzing the relations between supply and demand; if the credit demand exceeds its supply, the price of credit does not follow an orthodox market structure in which prices increase until the market reaches its equilibrium.

riskiest borrowers agree to pay higher interest rates. It is a typical adverse selection situation (AKERLOF, 1970).

In credit markets under imperfect information there is also the moral hazard problem, which concerns the decision of the borrower to pay or not for the loan after the contract is signed, or even to invest the obtained monetary resources in projects which are riskier than the ones indicated before the contract was signed (RAY, 1998; TASIC, 2005, HYYTINEN; VÄÄNÄNEN, 2006). It happens because the agents’ behavior is not observable by the principal. The agent’s behavior is usually the most beneficial for himself, but not necessarily for the principal (MACHO-STADLER; PÉREZ-CASTRILLO, 2001). The moral hazard problem may be intensified when high interest rates are charged, because they stimulate borrowers to invest the loan resources in risky projects, usually with great potential returns, in an attempt to cover the cost of capital (STIGLITZ; WEISS, 1981).

Even though there are entrepreneurs who agree to pay higher interest rates to obtain credit, those rates may not be desired by lenders, since they imply higher default risk. To provide high priced loans would not be an optimal decision to the bank, and so disequilibrium between the supply and the demand for credit may be perpetuated.

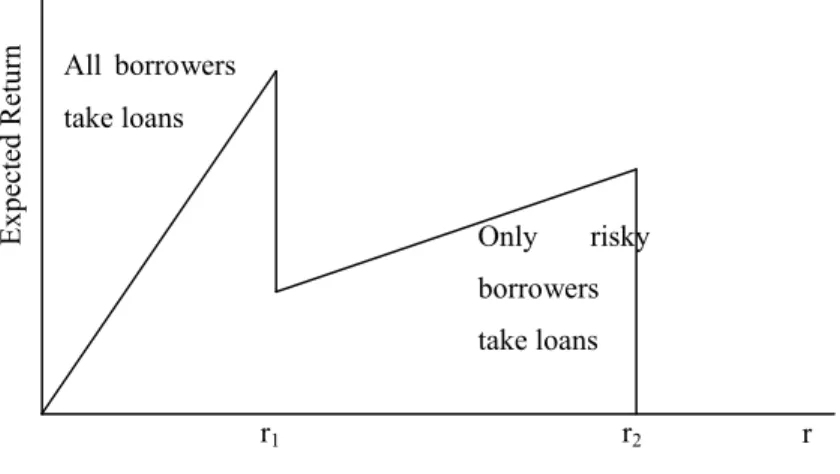

Figure 2.1 – Interest rate that maximizes the expected return to the bank.

Source: Adapted from Stiglitz and Weiss, 1981, p. 394.

In Figure 2.1, the expected return of the bank occurs at interest rate r*. It is possible that at that rate, the demand for credit exceeds its supply. According to orthodox microeconomics, there should be an increase in interest rates until the supply of credit equaled to its demand; however, loans contracted at a rate higher than r* would reduce the expected return to the bank. Thus, an entrepreneur who accepts to take loans at a rate higher than r* will not be able to do it, and so, a situation of credit rationing is established.

According to Stiglitz and Weiss (1981), there are two groups of borrowers: 1) the risk-free group, which takes loans only at rate r1 or lower; and 2) the risky group, which accepts to take loans at

rates r2 or lower (r1 < r2). When interest rates are higher than r1, the borrowers’ risk profile

changes drastically, because risk-free borrowers give up the transaction. That results in adverse selection, as can be seen in Figure 2.2.

r* Interest Rates

E

x

p

ec

te

d

R

et

u

Figure 2.2 – Optimal interest rate.

Source: Adapted from Stiglitz and Weiss, 1981, p. 397.

Still according to Stiglitz and Weiss (1981), interest rates are not the only relevant terms in credit contracts. The loan size also signals credit risk. A loan tends to become riskier as its size becomes larger (STIGLITZ; WEISS, 1981; TASIC, 2005). Collateral, which will be discussed in detail later, is also very relevant for the credit granting decisions (RAY; 1998; TASIC, 2005).

In fact, there are different factors which financiers take into account when deciding about a credit transaction to a small firm. These factors result from attempts of financiers to opportunistically charge the high interest rates that the credit rationed borrowers accept to pay without leveraging the imminent risk of default which is implicit in highly priced loans. These attempts include techniques applied by banks to deal with information asymmetry when trying to expand their credit activities and obtain economies of scale with their pools of small business loans (RAUCH; HENDRICKSON, 2004), such as the screening of the borrower’s credit behavior ex ante (BAAS; SCROOTEN, 2006) or the management of credit contracts by means of loans collateralization (RAY, 1998) and securitization (MESTER, 1997).

In the next section, lending techniques to small businesses and contractual aspects of loan collateralization and securitization are discussed as strategies used by banks to cope with imperfect information in small business credit markets.

r1 r

E

x

p

ec

te

d

R

et

u

rn

r2

r = Interest Rates All borrowers

take loans

Only risky

borrowers

2.4 Lending Techniques

Baas and Schrooten (2006) argue that financial providers can make an efficient decision to finance a given project only on the base of sufficient information, which is not always publicly available. The literature distinguishes between two types of loan decision processes: 1) relationship banking; and 2) statement – or ratio – banking. A relationship loan is based on objective and subjective information about borrowers obtained by means of their relationships with the bank (DIAMOND, 1989), while a ration loan is made according to predetermined objective procedures such as credit scoring and loan securitization (RAUCH; HENDRICKSON, 2004).

Relationship lending and statement lending are characterized and discussed next.

2.4.1 Relationship Banking

Specifically, SMEs are not forced to use sophisticated accounting techniques nor to publish balance sheets. In such circumstances, information about their solvency capacity becomes costly for financiers to obtain, so relationship banking might be used in preference to statement (or ratio) lending (BAAS; SCHROOTEN, 2006).

relationship by banks may be exploited in order to charge greater interest rates (SHARPE, 1990; HERNÁNDEZ-CANOVA; MARTINEZ-SOLANO, 2007).

According to Diamond (1989), perfect competition is impeded by asymmetric information and financiers benefit from obtaining information about borrowers; relationship lending is generated by the bank’s past experience with a borrower (BAAS; SCHROOTEN, 2006). Since reliable information on SMEs is rare and costly, relationship banking is considered an appropriate technique for the collection of information about these firms. The process is simple: the firm and the bank enter a long-term relationship, which assures credit to the firm and financial information to the bank (BERGER et al., 1995). The result is the increase of the value of information owned by banks.

Hernández-Canovas and Martinez-Solano (2007) state that the establishment of relationships between moneylenders and borrowers is one way to reduce the problem of asymmetric information in markets where businesses have need for funds unsatisfied by the banking sector, because these relationships reveal valuable information about borrowers.

Rating agencies and the financial press seldom supervise small firms, and that is one of the reasons why information asymmetry between these companies and moneylenders is considerable (PETERSEN; RAJAN, 1995). Also, young firms typically do not have an established reputation about their competence and honesty, nor about the risk of projects they may take (HERNÁNDEZ-CANOVAS; MARTINEZ-SOLANO, 2007). As a result, the cost of information is elevated and the value of relationship is increased to both borrower and lender.

Despite the potential of relationship banking to reduce information asymmetry between borrowers and lenders, empirical and theoretical literature shows ambiguous results about the relation between interest rates and relationship banking. Petersen and Rajan (1995) suggest that loan interest rates decline with relationship banking, while Sharpe (1990) reveals conditions in which lenders take the borrower’s surplus by means of raising prices because of the private information they collect in relationship lending.

2.4.2 Financial Statement (Ratio) Lending

When a company needs external financing and faces credit rationing because of adverse selection, financial intermediaries do not know its actual degree of risk (DETRAGIACHE et al., 2000). For small businesses, which are less transparent from the informational point of view, adverse selection can be so severe that it prevents them from getting the necessary financing outside their established banking relationships (HERNÁNDEZ-CANOVAS; MARTINEZ-SOLANO, 2007).

That situation can be reverted if banks develop alternative techniques to provide loans for small business, including procedures which would reduce screening costs and avoid default. Financiers willing to apply lending techniques driven buy a massive supply depend on automated lending processes based on credit scoring and on contractual terms such as collateralization and securitization. These techniques are known as statement– or ratio – lending techniques (RAUCH; HENDRICKSON, 2004). They theoretically allow the credit market to deal with adverse selection and therefore should relief the rationing situation which imposes difficulties to small firms when they need to diversify their financial providers.

Ratio loans are based on the analysis of the firm’s balance sheet, relying strongly on credit scoring, and, in some cases, on securitization of loans. Ratio borrowers usually have an established operational history and encounter standardized underwriting procedures for obtaining credit (BERGER; UDELL, 1996).

Large banks, due to superior technology, have comparative advantage when making ratio loans in mass at relatively low rates; if a consistent loan system and available information is disposable, it is easier for them to monitor loan officers in a large and complex organization (RAUCH; HENDRICKSON, 2004).

author argues that statistical methods to predict the probability that a loan applicant will default, known as credit scoring, represent benefits for small business lenders. She reveals, however, that credit scoring strongly depends on the availability of data. Among the benefits of credit scoring, it is less necessary for a bank to have a presence via a branch in local credit markets, what allows banks to expand the supply of small business loans. Also, credit scores reduce the time needed to approve a transaction (LAWSON, 1995) and make it easier to register the reasons for a lending decision.

Credit scoring methods rely on data about the borrowers’ performances in previous loans, obtained mostly from the bank’s historical records and from credit bureaus (MESTER, 1997). Variables such as the entrepreneur’s business revenue, outstanding debt and financial assets are typically used, and therefore, credit scoring usually refers to the analysis of the borrower’s financial statement.

But even a good credit score system cannot predict with certainty any particular loan performance, although it provides a fairly accurate guess. A challenge for the development of good credit scoring models to small businesses is the lack of information about these firms due to poor accounting registers. Also, since small firms are frequently credit rationed, there is not enough historical data about their loans to constitute sufficient information for a scoring model. Large banks, which had enough historical data, were the first to use scoring for small business loans, during the 1990s (WANTLAND, 1996).

Some banks rely on automatic processes to approve small amounts of credit based on credit scoring, but many review their score-based decisions for each transaction, eventually changing them. There are banks that use credit scores as a first input to more detailed analysis in lending decisions. Many efficient credit scoring models show that, among the most important indicators of small businesses’ loan performances are the personal characteristics of the business owner, rather than of the business itself, because small businesses’ financial statements are less sophisticated than those of larger businesses. Small businesses owners’ and their businesses’ finances are often commingled (MESTER, 1997).

However, because of the heterogeneity of small business loans performances and lack of information, securitization for small business lending is difficult to manage (MESTER, 1997). The mechanisms used to securitize loans and the effects of collateral are quite particular in small business lending, and therefore, collateralization and securitization of small business loans in markets with imperfect information are specifically discussed next.

2.4.3 Collateralization and Securitization

Collaterals strongly influence credit granting decisions (TASIC, 2005). When it is only valuable to the borrower, but not to the lender, collateral works as an incentive to solvency, but there is a ceiling level of this kind of collateral that a bank should demand to maximize its expected return, because risky borrowers tend to commit larger amounts of collateral in credit contracts since they are not risk averse (STIGLITZ; WEISS, 1981).

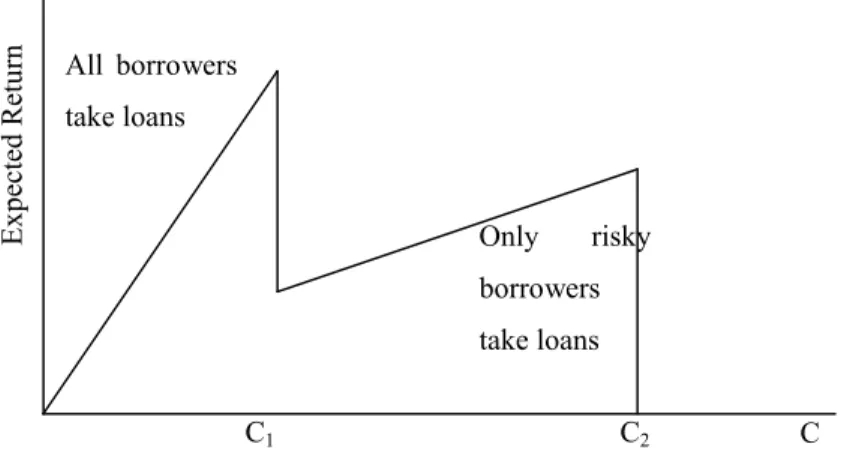

Figure 2.3 – Optimal level of collateral

Source: Adapted from Stiglitz and Weiss, 1981, p. 405

In Figure 2.3, the existence of two groups is assumed: 1) the risk-free group, in which borrowers take loans only at the level C1of collateral or lower; and 2) the risky group, in which borrowers

accept to commit an amount of collateral equal to or less than C2 (C1 < C2). When the level of

demanded collateral exceeds C1, the pool of borrowers change its profile, risk-free borrowers do

not accept the loan conditions, and so adverse selection arises.

The preceding arguments stands predominantly for collateral which is valuable to borrowers but not to lenders. Because collateral which is only valuable to the borrower represents nothing but an incentive to solvency (RAY, 1998), and only to some extent, there is an optimal level of that kind of collateral to the lender (STIGLITZ; WEISS, 1981).

On the other hand, collateral that is valuable to both parties has the advantage of covering the lender against default, besides being an incentive to the borrower’s payback (RAY, 1998). According to the financial literature, collateral that most covers default risk is liquid, such as credit derivatives and monetary instruments (BOMFIM, 2005) like checks or other receivables (KIMBER, 2004).

Basically, to demand liquid receivables as collateral in a loan is a securitization strategy. Securitization is defined as the packaging of pools of loans (or receivables) and the redistribution of these pools to an investor in the form of securities (or loans), which are collateralized with the

C1 C

E x p ec te d R et u rn C2

C = Level of colllateral demanded

All borrowers

take loans

Only risky

borrowers