REVISTA

BRASILEIRA

DE

ANESTESIOLOGIA

OfficialPublicationoftheBrazilianSocietyofAnesthesiologywww.sba.com.br

SCIENTIFIC

ARTICLE

Effects

of

elevated

artificial

pneumoperitoneum

pressure

on

invasive

blood

pressure

and

levels

of

blood

gases

Octavio

Hypolito

a,∗,

João

Luiz

Azevedo

b,

Fernanda

Gama

c,

Otavio

Azevedo

b,

Susana

Abe

Miyahira

c,

Oscar

César

Pires

c,

Fabiana

Alvarenga

Caldeira

c,

Thamiris

Silva

caUniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo(Unifesp),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

bEscolaPaulistadeMedicina,UniversidadeFederaldeSãoPaulo(Unifesp),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil cHospitalMunicipalJosédeCarvalhoFlorence,SãoJosédosCampos,SP,Brazil

Received25September2012;accepted20March2013 Availableonline4April2014

KEYWORDS

Artificial

pneumoperitoneum; Laparoscopy; Surgicalinstruments; Monitoring;

Intraoperative

Abstract

Backgroundandobjective: toevaluatetheclinical,hemodynamic,gasanalysisandmetabolic

repercussionsofhightransientpressuresofpneumoperitoneumforashortperiodoftimeto ensuregreatersecurityforintroductionofthefirsttrocar.

Methods:sixty-sevenpatientsundergoinglaparoscopicprocedureswerestudiedandrandomly

distributedinP12group:n=30(intraperitonealpressure[IPP]12mmHg)andP20group:n=37 (IPPof20mmHg).Meanarterialpressure(MAP)wasevaluatedbycatheterizationoftheradial artery; andthrough gasanalysis, pH,partialpressure ofoxygen(PaO2), partialpressureof CO2(PaCO2),bicarbonate(HCO3)andalkalinity(BE)wereevaluated.Theseparameterswere measuredinbothgroupsattimezerobeforepneumoperitoneum(TP0);attime1(TP1)when IPPreaches12mmHginbothgroups;attime2(TP2)afterfiveminwithIPP=12mmHginP12 andafter5minwithIPP=20mmHgatP20;andattime3(TP3)after10minwithIPP=12mmHg inP12andwithreturnofIPPfrom20to12mmHg,starting10minafterTP1inP20.Different valuesfromthoseconsiderednormalforallparametersassessed,ortheappearanceofatypical organicphenomena,wereconsideredasclinicalchanges.

Results:therewerestatisticallysignificantdifferencesinP20groupinMAP,pH,HCO3andBE,

butwithinnormallimits.Noclinicalandpathologicalchangeswereobserved.

Conclusions:highandtransientintra-abdominalpressurecauseschangesinMAP,pH,HCO3and

BE,butwithoutanyclinicalimpactonthepatient.

©2014SociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologia.PublishedbyElsevier EditoraLtda.Allrights reserved.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:octaviohypolito@hotmail.com(O.Hypolito).

Introduction

Minimallyinvasivemethodsusedtoaccessorgansand struc-turesoftheabdominalcavitycauseareductionofmetabolic

0104-0014/$–seefrontmatter©2014SociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

response to trauma and other benefits for patients. This appliesparticularlytolaparoscopy.1---3However,being

rela-tivelyrecent,thelaparoscopicsurgicaltechniquesstillshow controversy.One of them is thebest wayof creating the pneumoperitoneum.Althoughnoconsensusexistsregarding the best method for accessing the peritoneal cavity with respect to the establishment of pneumoperitoneum, the puncture with Veress needle is the technique most often used.4,5Thecomplicationsoccurringduringtheintroduction

ofthefirstcatheterarestillbeingdiscussed.

Muchofthecomplicationsinlaparoscopyprocedures(in about 50% of them) occur at the beginning of the proce-dure,duringtheintroductionoftheVeressneedleandthe firsttrocar.Forthatreason,laparoscopy isa peculiar sur-gical procedure, in which the surgical approach is more dangerousthanthesurgeryitself.6Inarecentreviewofthe

literatureconcerninginjuriescausedbytheuseofaVeress needleandthefirsttrocarin357,257patients,aprevalence of 0.04% of gastrointestinallesions and 0.02% of vascular lesionswasfound.7 These iatrogenicevents arerelatively

rare,buttheconsequencesareexceptionallygrave.Insuch circumstances,bleeding,peritonitis,multipleorganfailure, deathandmedico-legalimplicationsmayoccur.

Thus,itisessentialtoseektechnicaloptionssaferthan themostcommonlyusedmethod,whichconsistsofthe Ver-essneedlepunctureinthemidlineoftheabdomen,inthe vicinity ofthe umbilicus; abdominalinsufflationtoobtain intraperitonealpressureof10and12mmHg;andtheblind introductionofthefirsttrocarinthesamelocationusedfor needleinsertion.4,5

A literature review revealed that the most serious injuries occurwhentheVeressneedle isinserted intothe midlineoftheabdomenattheleveloftheumbilicus.7The

insertion of the Veress needle in the left hypochondriac region,however,issafeandeffective8andthelikelihoodof

seriousinjuryislower,becausethisplacedoesnotinvolve vitalstructures,suchastheretroperitonealvessels.7

However,theinsertionofthefirsttrocarshouldbedone in the midline at the level of the umbilicus, and not in the left hypochondrium, as recommended for the Veress needle.8 This recommendation is based on the fact that

thetrocaristheplacewherethelaparoscopiccannulawill be introduced.4,5 When the laparoscope is introduced in

the midline at the umbilicus, we get better clarity, bet-ter imagesof organs and intra-abdominal structures, and abroadervisionfortheintroductionoftheothertrocars.

The establishment of a regime of very high pressure by an artificial pneumoperitoneum, during a period just sufficient for the introduction of the first trocar, taken blindly in theclosed method, may contribute tothe pro-tectionoftheintra-abdominalstructuresagainstinjury,but without any organic repercussion in the form of clinical complications.9,10Novascularinjurywasreportedinastudy

thatinvestigated 3041patients undergoingblind insertion of the firsttrocar in the midline withan intra-abdominal pressurebelow25---30mmHg.11

Onestudyinvestigatedtheprotectiveeffectofelevated intraperitonealpressureonintra-abdominalstructures fac-ingthe aggression shown by theblind introduction of the first trocar into the peritoneal cavity.12 The authors

cor-relatedthedistance betweentheanteriorabdominalwall and intra-abdominal viscera withdifferent intraperitonial

pressuresandvolumes,andalsotheobserveddistanceswith therequired forceforinsertionofthefirsttrocarintothe abdominalcavity.Theseauthorsalsocouldobservethathigh intraperitoneal pressures cause an important increase in thesedistancesandinthevolumeofgasbubblesandprovide abetterslippageof thetrocarintothecavity. Itwasalso shownthat,withtheuseofhighintraperitonealpressure, theabdominalwallbecomestenserandreducesitselastic deformationcausedbyaforceappliedtothetrocar.12

Despite the absence of clear clinical signs of complications, the artificial pneumoperitoneum with very high pressures over a prolonged period of time can cause hemodynamic and structural changes in the host, directly related to the magnitude of the tensional lev-els and detectable by monitoring hemodynamic and gas analysis parameters. Thus, under high intraperitoneal pressures,decreases incardiacoutput andvenousreturn, increasesofmean arterial pressureandsystemic vascular resistance and changesin renal perfusion and glomerular filtrationwere demonstrated,besides ischemic lesionand reperfusion of intra-abdominal organs.13---19 Because of

thesedeleterious effectsofhigh intraperitonealpressures duringlaparoscopic procedures, most authorsrecommend maintainingthepressureatalevelof12mmHg(nevermore than15mmHg,consideredasahighpressure).5,20---26

Despite the above considerations, hemodynamic, metabolicandstructuralchangesmayoccurwithelevated intra-abdominalpressures for aprolonged periodof time. Theliteraturedoesnotprovideimportantinformationabout gasanalysisandmetabolicchangesinpatients undergoing high transient intraperitoneal pressure. This means that laparoscopic surgeonsmay not have takeninto accounta safestrategyfortheintroductionofthefirsttrocar.

The aim of this study is to improve the safety of the introduction of the first trocar and evaluate the clinical, hemodynamic, gas analysis and metabolic effects of high transientpneumoperitoneumpressuresforshortperiodsof time.

Materials

and

methods

Forthis prospective, randomized clinical trial, authoriza-tion was obtained from the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP) Research Ethics Committee under num-ber1.219/07, andfromtheUniversityofTaubaté(Unitau) ResearchEthics Committee,under number007/2.007. All patients signed an informed consent.The study was con-ductedatHospitalMunicipalDr.JosédeCarvalhoFlorence (HMJCF)inSãoJosédosCampos(SP).

BetweenOctober2007andMay2008,67patients sched-uledfor electivelaparoscopic surgery,between 20and79 yearsold,classifiedintoASA Ior ASAII accordingtotheir physical condition, with no history of abdominal surgery onorganslocated at theabdominalsupramesocolic level, withoutpreviouslydiagnosedperitonitisandwithbodymass index(BMI)lessthan35,werestudied.

22 and 72 years (mean±SD: 47.2±14.5 years), withBMI between20.2and33.4kgm−2(mean±SD:26.3±4kgm−2).

P20 group consisted of 30 women and seven men, aged between 20 and 79 years (mean±SD: 46.5±15 years),withBMIbetween17.5and34.6kgm−2(mean±SD:

26.2±3.8kgm−2).Nostatisticallysignificantdifferencewas

observed between groups in the demographic data com-pared(p≤0.05).

All patients received pre-anesthetic evaluation in the clinic in a prior date tothe surgery. No patientreceived anestheticpremedication.

Before the start of anesthesia, the modified Allen test was performed.27 The patients were hydrated with

Ringer Lactate after venipuncture with a 18G catheter. The patients were monitored by lines installed in order to assess data from cardioscopy, pulse oximetry, non-invasive blood pressure,28 capnometry and intratracheal

pressure.

Allpatientsreceivedgeneralanesthesia.Theanesthetic procedurewasinducedwithsufentanil0.5mcgkg−1,

rocuro-nium 0.6mgkg−1 and propofol 2mgkg−1. The anesthesia

was maintained with sevoflurane in a mixture of oxygen andcompressedair. Allpatientswere mechanically venti-latedbyconstantfluxinacyclingtimefan.ErgoSystemPC 2700-ShogunTakaoka anesthesiaandmonitoring machines wereused,aswellasFabiusGSDrägeranesthesiamachine with Dixtal model DX 2010 monitors. Initial ventilation was achieved with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 60%, positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP)=4cm H2O, tidal

volume=7mLkg−1,respiratoryrate=15breathsperminute

andinspiration/expirationratio=1:2.

With the establishment of an appropriate anesthetic plan and a negative Allen test (modified by Asif),26 the

radialartery wascatheterized in the non-dominant limb. Amaximumofthreeattemptsweredone,withexclusionof patientsinwhomnosuccesswasobtainedintheprocedure. Sixpatientswereexcludedfromthestudy:onehad bron-chospasmafterinduction;onewithdifficultintubationand withneedofadditionalproceduresnotincludedinthestudy protocol;two,withfailureinthethirdattemptto catheter-izationof theradialartery;andintheremainingtwo,the samplewaslostbyclotformation.

The creation of pneumoperitoneum was obtained by closedtechniquewithabdominalpuncturethroughthe Ver-essneedleandCO2flowof1L/min.

Duringtheprocedure,MAPandbloodgasanalysis---pH, PaO2(inmmHg),PaCO2 (inmmHg),HCO3 (inmmol/L),BE

(inmmol/L)withabloodgas analyzerRapidlab348Bayer HealthCare,Model348pH/AnalyzerSN6678.These param-eterswereevaluatedin both groups at timezero, before pneumoperitoneum; at time 1 (TP1), when IPP reaches 12mmHginbothgroups:at time2(TP2),after5min with IPP=12mmHginP12andafter5minwithIPP=20mmHgin P20;andat time3(TP3),after10minwithIPP=12mmHg inP12andwithreturnofIPPfrom20to12mmHg,counted 10minafterTP1inP20.

Allpatientswerefollowedduringtheanesthetic-surgical procedure through the following parameters: heart rate, heartrhythm,pulseoximetry,capnometry(EtCO2)andmean

arterial pressure. In the post-anesthesia recovery room, heart rate, heart rhythm, mean arterial pressure, pulse oximetry,level ofconsciousness andmuscle activitywere

110

100

90

80

70

60

M0

Mean arterial pressure

mmHg

M1 M2 M3

MAP P12 n=30 p.0000 MAP P20 n=37 p.0000

Figure1 Meanarterialpressure(MAPinmmHg).

theobservedparametersobserved,untilpatients’discharge totheward.

Weconsidered as‘‘occurrence of clinical change’’ the measured valuesof the various parametersthat extrapo-latedthelimitsconsiderednormalforhealthypeople,orthe emergence of atypical phenomena indicative of the pres-enceoforganicdisease.HRlessthan75beatsperminute; MAP between 70mmHg and120mmHg;SaO2 greater than

93%; EtCO2 between 30 and45mmHg;intrathoracic

pres-sure (ITP) below 35cm H2O; pH between 7.35 and 7.45,

PaCO2between30and45mmHg;PaO2above80mmHg;BE

between−2and+2;andHCO3 between22and26mEqL−1

wereconsiderednormalvalues.

As for the statistical analysis, in the descriptive anal-ysis, position measurements for continuous variables and frequencyforcategoricalvariableswereused.Tocompare genderbetweengroups,weusedthechi-squaredtest,and to compare age and BMI between groups, we used the nonparametric Mann---Whitneytest. Forcomparisonamong timesofvariablesofinterest,weusedtheanalysisof vari-ance(ANOVA)forrepeatedmeasureswithtransformationby posts.Alevelof5%(p=0.05)wasconsideredsignificant.

Results

Meanarterialpressure(MAPinmmHg)

In P12 group, MAP presented the following values (mean and standard deviation) for M0, M1, M2 and M3, respec-tively: 68.57±10.18, 88.10±17.68, 90.10±19.03 and 99.07±18.58,withstatisticaldifference(p=0.0000).InP20 themeanandstandarddeviationvaluesofMAPforM0,M1, M2andM3were,respectively:70.57±14.58;83.57±12.86, 89.30±15.33and92.43±14.42,withstatisticaldifference (p=0.0000)(Fig.1).InP12groupthestatisticaldifference occurredinM0withM1,M2andM3;betweenM1andM3and betweenM2andM3.InP20groupadifferencewasnotedin M0withM1,M2andM3,andbetweenM1withM2andM3.

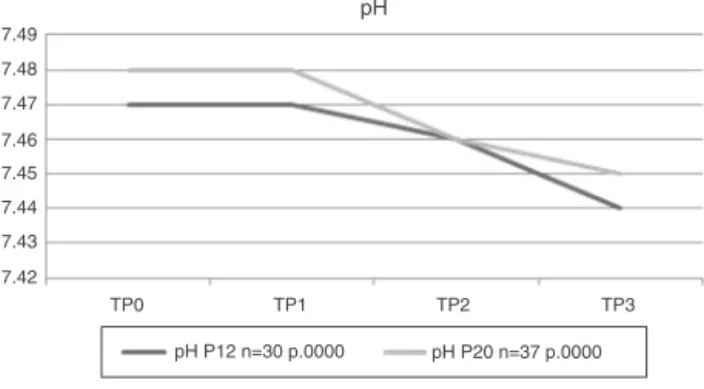

Hydrogenpotential(pH)

7.49

7.48

7.47

7.46

7.45

7.44

7.43

7.42

TP0 TP1

pH

TP2

TP3

pH P12 n=30 p.0000 pH P20 n=37 p.0000

Figure2 Hydrogenpotential(pH).

standard deviation) for M0,M1,M2and M3were, respec-tively:7.48±0.06,7.48±0.06,7.46±0.06and7.45±0.07, withstatisticaldifference(p=0.0000)(Fig.2).InP12group thepHshowedsignificantchange betweenM0andM3,M1 relativetoM2andM3,andbetweenM2andM3.InP20group differenceswereobservedbetweenM0inrelationtoM2and M3,andofM1comparedtoM2andM3.

Partialpressureofoxygeninthearterialblood (PaO2inmmHg)

In P12 group, PaO2 showed the following values (mean

and standard deviation) for M0, M1, M2 and M3, respec-tively:216.80±51.60;192.15±52.73;191.88±51.74,and 196.77±46.66, withstatistical difference (p=0.0057). In P20 group, PaO2 showed the following values (mean and

standard deviation) for M0, M1, M2 and M3, respec-tively:212.07±72.37;197.73±52.74;202.35±52.46,and 203.41±49.20, with no statistical difference (p=0.4239) (Fig. 3). In P12 group, statistical difference occurred betweenM0andM1.

Partialpressureofcarbondioxide(PaCO2inmmHg)

InP12group,meanandstandarddeviationvaluesofPaCO2

for M0, M1, M2 and M3 were, respectively: 31.96±5.20; 31.48±6.67, 32.68±6.82 and 32.63±8.30, with no sta-tistical difference (p=0.3557). In P20 group, PaCO2 had

thefollowingvalues(meanandstandarddeviation)forM0, M1, M2 and M3, respectively: 32.47±5.36; 32.43±4.84;

220 215 210 205 200 195 190 185 180 175

TP0

Partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2)

TP1

TP2

TP3

PaO2 P20 n=37 p.4239 PaO2 P12 n=30 p.0057

Figure3 Partialpressureofoxygeninarterialblood(PaO2in

mmHg).

35

34

33

mmHg 32

31

30

TP0

Partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood (PaCO2 – in mmHg).

TP1 TP2 TP3

PaCO2 P12 n=30 p.3557 PaCO2 P20 n=37 p.0887

Figure4 Partialpressureofcarbondioxideinarterialblood (PaCO2inmmHg).

33.19±5.08and34.09±6.20,withnostatisticaldifference (p=0.0887)(Fig.4).

Bicarbonate(HCO3inmmolL−1)

InP12group,HCO3showedthefollowingvalues(meanand

standard deviation) for M0,M1, M2and M3,respectively: 22.85±3.11, 22.50±3.85, 22.42±3.34 and 21.96±4.38, withno statistical significance (p=0.3629). In P20group, HCO3showedthefollowingvalues(meanandstandard

devi-ation)for M0,M1,M2 andM3,respectively: 23.75±3.45, 23.48±2.64, 23.06±3.04 and 23.20±3.17, with statisti-caldifference(p=0.0126)(Fig.5).InP20grouptherewas statisticaldifferencebetweenM0andM2.

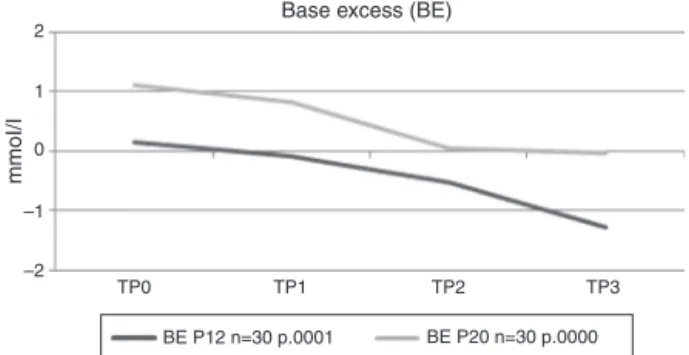

Alkalinity(baseexcess[BE]inmmolL−1)

In P12group, BE showed the following values(mean and standard deviation) for M0,M1, M2and M3,respectively: 0.15±3.00,−0.08±3.55,−0.53±3.14and −1.27±3.92, with statistical difference (p=0.0001). In P20 group, BE showed the following values (mean and standard devia-tion) for M0, M1, M2 and M3, respectively: 1.10±3.27, 0.82±2.74,0.05±3.22 and −0.03±3.12, withstatistical difference(p=0.0000) (Fig. 6). In P12 group, BE showed statistical difference group when M0 was compared with M3andM1 wascomparedwith M2and M3.In P20group,

24

23

22

21

TP0

Bicarbonate (HCO3)

mmol/l

TP1

TP2

TP3

HCO3 P12 n=30 p.3629 HCO3 P20 n=37 p.0126

2

1

0

–1

–2

TP0

Base excess (BE)

mmoI/I

TP1 TP2 TP3

BE P12 n=30 p.0001 BE P20 n=30 p.0000

Figure6 Alkalinereserve(baseexcess---BEinmmolL−1).

differencesappeared inM0comparedwithM2andM3and inM1comparedwithM2andM3.

Thevaluesmeasuredinthedifferentparameters evalu-ateddidnotsurpassthoseconsideredasnormalinhealthy populationsduringsurgicalproceduresandintheirstayuntil dischargefrompost-anesthesiarecovery.

Discussion

Inthisstudy,theorganicalterationsandgas exchangesin laparoscopic procedures with high transient pressures of pneumoperitoneum with sufficient time to introduce the firsttrocarwereanalyzed.

Patients were divided into twogroups, P12 (intraperi-toneal pressure of 12mmHg) and P20 (intraperitoneal pressureof20mmHg).

TheP12groupwasthepositivecontrolgroup,inwhich alleventsandallpossiblechangesduringthesurgical pro-cedurewithstandard(12mmHg)intraperitonealpressurein ourpopulationofinterestwereanalyzed.Thepurposeofthe inclusionofP12group inthisstudywastoclarifythe role inisolationofhighpressures(20mmHg)inanychangethat wastobeobservedinP20group,byacomparisonamongthe timesofeachgroupstudied.Thebehavioroftheparameters wasevaluatedinP12grouptoexcludethefactor‘‘exposure timetopneumoperitoneum’’ asa determinantof organic changeslikelytooccurinP20group.Thus,itmaybe pos-sibletoassignexclusivelytohighintraperitonealpressure anysuchchangesobservedinP20.

The P20 group wasthe experimental group with auto-control,becausetheirpatientsweresubjectedtodifferent intraperitoneal pressures, from absence of pneumoperi-toneumtoanintraperitonealpressureof20mmHg.

The anestheticagentspropofol,rocuronium,sufentanil andsevofluranewereusedwiththeaimofmaintainingthe stability of cardiopulmonary parameters, providing quick accesstotheairwaysanddecreasingthepostoperative inci-denceofnausea,vomitingandpainprocesses.29---34

The initial ventilator settings were: constant flow, end inspired oxygen fraction of 60%, positive end expi-ratory pressure (PEEP) of 4cm H2O, tidal volume of

7mLkg−1,respiratoryrateof15breathsperminute,

inspi-ration/expiration ratio of 1:2 and with volume cycling, withthe intention of promoting an adequate minute vol-umetocompensateforthepatient’sexposuretoincreased intraperitonealpressurewithCO2.35

A study conducted by Abu-Rafea et al.36 showed no

cardiopulmonary complications in 100 healthy women

undergoinghighintra-abdominalpressure(between10and 30mmHg) during the introduction of the first trocar. The authors analyzed the volume of CO2 effectively inflated

into theperitoneal cavity, heart rate, blood oxygen satu-ration,meanarterialpressureandpulmonarycompliance, and observed statistically significant changes in MAP and pulmonary compliance, but these changes were not clin-ically significant. However, Abu-Rafea etal.36 did not set

parameterstoassesschangesinrespiratoryfunctionandgas exchange.Moreover,theeffectofeachpressurelevel(10, 15,20,25and30mmHg)wasevaluatedattheexactmoment itwasachieved,withouttakingintoaccountthecumulative effectof the durationof pneumoperitoneumfor insertion of the first trocar, and this makes difficult to assess the clinicaleffectsresultingfromthedurationof pneumoperi-toneum, rather than from the level of intra-abdominal pressurereached.Furthermore,thecardiovascular parame-tersweremonitoredwithnoninvasivemethodsandarterial bloodgaseswerenotanalyzed.Anotherstudyshowedthat the high intra-abdominal pressure is a safe practice, and noadverse clinical effects wereobserved by non-invasive monitoringanalysis.37

In our results, a statistically significant change was observed in MAP in both groups and throughout artificial pneumoperitoneum. The fact that this change was also observedinP12groupwouldsuggestthatitscausewasdue totheeventofexposureofthebodytopneumoperitoneum, evenwithastandardIPP.Evenatlowpressures(considered) (12mmHg),avasoconstrictionreflexistriggered,with con-sequentincreaseinbloodpressure.However,thesechanges donotrepresentclinicalproblemstothepatient(Fig.1).It isnoteworthythattherewasnocaseofhypertensioninany ofthegroups.

Laparoscopic procedures with pneumoperitoneum and the use of CO2 are associated with risk of hypercapnia

through IPP increase and of absorption of CO2 through

the peritoneum,38---40 which canlead to respiratory

acido-sis. Some studies show that CO2 absorption is dependent

ontheintraperitonealpressureandontheintegrityofthe peritoneumtoabsorbCO2.Inthepresentstudy,no

statis-tically significant change in PaCO2 values in both groups

was observed. As the ventilatory parameters were not changed during the study,the findings suggest that there wasnoincreaseinCO2absorptionbyperitoneumduetothe

increaseinIPPof12---20mmHgduring5mininthepresence ofaconsistentlungventilation.Thismaybeduetothefact thattheincreaseinintra-abdominalpressurepromotes cap-illarycompression,limitingCO2absorption;41---43ontheother

hand,itdecreasesthebloodflowtothesplanchnicregion. The present study demonstrated that patients initially developed a mild respiratory alkalosis as a consequence of the ventilatory parameters determined for the proce-dure. Becausetheseparameters werenotchanged during thestudyandthemeasuredvaluesofrespiratoryproducts (PaCO2)didnotchangesignificantly,thedropinpHvalues

---immediatelyafterthealkalosis---instatisticallysignificant valuesmayhaveoccurredbecauseofthemildelevationof PaCO2valuesandbecauseofthemetabolicacidosis

This corroborates the pathophysiological explanation that a decreased perfusion of intra-abdominal structures play a major rolein the change in pH valuesobserved in this study,sincetheother factor ofacidosis(i.e.,CO2

absorp-tion)wassimilarinP20andP12groups,asmaybeverified bythePaCO2valuesinformedbygasanalysis(Fig.4).Some

authors44 showed an increase in pH at an intraperitoneal

pressure of 15mmHg in the first30min, with subsequent decrease of these values. This result was similar to that found in this study in the presence of higher (20mmHg) andlower(12mmHg)intraperitonealpressures.Thechanges foundinthisstudyhadnoclinicalsignificance(Fig.2).

Regarding HCO3, there was a statistically significant

reductioninP20groupafterexposureofthepatienttoan IPP of 20mmHg, which was not observed at other times of this group with lower IPPs and that also did not hap-peninP12group.Thisshowsthatthepressureof20mmHg isthefactor responsiblefor thechanges.Consideringalso thefactthatthepHhasshowngreaterreductionunderan IPPof20mmHgwithoutsignificant elevationofPaCO2,all

these may be pointing to a higher consumption of bicar-bonate,in ordertoattenuating themetabolic acidosisby decreasingtheirrigationofsplanchnicorgans.Inthestudy ofSefretal.,44 therewasnodifferencebetweenpressures

of10and15mmHgwithrespecttotheproductionofHCO3,

whileinourstudythepressureof20mmHgshoweda statis-ticallysignificantdecreaseinthisparameter.However,this changehadnoclinicalsignificance(Fig.5).

Regardingthealkalinereserve(BE),therewasa statisti-callysignificantdecreaseinbothgroups.Thechangesfound arerelatedtotheexposuretimeofthebodyto pneumoperi-toneumfactor.Inthepresenceofaregimeofintraperitoneal pressure of 20mmHg, these changes appear earlier. The decreaseinthevaluesofBEatanIPPof20mmHg, associ-atedwithdecreasedpHanddecreasedHCO3factorswithout

significant change in PaCO2, can point again to alkaline

reserve(BE)consumptiontocompensatefortheischemiaof splanchnicorgans.Sefretal.44reportedadecreaseinBEIPP

of10mmHgandanincreaseinthevaluesofBEof15mmHg. InthisstudyadecreaseinBEwasobservedatIPPsof12and 20mmHg.Thesechangeshadnoclinicalsignificance(Fig.6). The high (20mmHg) and transient (5min) intra-abdominalpressurefor insertionof thefirsttrocarcauses changes in MAP, pH, HCO3 and BE without clinical

conse-quencesforthepatientandshouldbeusedtopreventthe occurrenceofiatrogenicinjuriesintheintroductionofthe firsttrocar.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.Schippers E, Ottinger AP, Anurov M, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a minor abdominal trauma? World J Surg. 1993;17:539---42.

2.RollS,AzevedoJLMC,CamposF,etal.Two-portstechniqueof laparoscopiccholecystectomy.Endoscopy.1997;29:S43.

3.Novitsky YW, Kercher KW, Czerniach DR, et al. Advan-tages of mini-laparoscopic vs. conventional laparoscopic

cholecystectomy: results of a prospective randomized trial. ArchSurg.2005;140:1178---83.

4.NeudeckerJ,SauerlandS,NeugebauerEB,etal.TheEuropean AssociationforEndoscopicSurgeryclinicalpracticeguidelineon thepneumoperitoneumforlaparoscopicsurgery.SurgEndosc. 2002;16:1121---43.

5.MolloyD,KalooPD,CooperM,etal.Laparoscopicentry:a lit-eraturereview andanalysisof techniquesand complications of primary port entry. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;42:246---53.

6.Neves JFNP, Monteiro GA,Almeida JR, et al. Lesãovascular grave emcolecistectomia videolaparoscópica. Relatode dois casos.RevBrasAnestesiol.2000;50:294---6.

7.AzevedoJL,AzevedoOC,MiyahiraSA, etal. Injuriescaused

byVeressneedleinsertionforcreationofpneumoperitoneum:

asystematicliteraturereview.SurgEndosc.2009;23:1428---32,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0383-9.

8.AzevedoOC,AzevedoJLMC,SorbelloAA,etal.Veressneedle insertionin thelefthypochondriumin creationofthe pneu-moperitoneum.ActaCirBras.2006;21:296---303.

9.Reich H, Rasmussen C,Vidali A. Peritoneal hypertension for trocarinsertion.GynaecolEndosc.1999;8:375---7.

10.TsaltasJ,PearceS,LawrenceA,etal.Saferlaparoscopic tro-carentry:it’sallaboutpressure.AustNZJObstetGynaecol. 2004;44:349---50.

11.ReichH,RibeiroSC,RasmussenC,etal.High-pressuretrocar insertiontechnique.JSocLaparoendoscSurg.1999;3:45---8.

12.Phillips G, Garry R, Kumar C, et al. How much gas is requiredforinitialinsufflationatlaparoscopy.GynaecolEndosc. 1999;8:369---74.

13.KoivusaloAM,LindgrenL.Effectsofcarbondioxide pneumoperi-toneum for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand.2000;44:834---41.

14.Safran DB, Orlando R. Physiologic effects of pneumoperi-toneum.AmJSurg.1994;167:281---6.

15.Indberg F,Bergqvist D, Bjorck M, et al. Renal hemodynam-ics during carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:480---4.

16.MacDougallEM,MonkTG,WolfJS,etal.Theeffectofprolonged pneumoperitoneumonrenalfunctioninananimalmodel.JAm CollSurg.1996;182:317---28.

17.AkbulutG,PolatC,AktepeF.Theoxidativeeffectofprolonged CO2 pneumoperitoneumonrenal tissueofrats.SurgEndosc. 2004;18:1384---8.

18.OzmenMM,KessafAlsarA,BeslerHT.Doessplanchnicischemia occur during laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Surg Endosc. 2002;16:468---71.

19.ZulfikarogluB,KocM,SoranA.Evaluationofoxidativestressin laparoscopiccholecystectomy.SurgToday.2002;32:869---74.

20.Dexter SP, Vucevic M, Gibson J, et al. Hemodynamic con-sequencesof high andlow pressurecapnoperitoneumduring laparoscopiccholecystectomy.SurgEndosc.1999;13:376---81.

21.RosenDMB,LamAM,Chapman M,et al.Methodsofcreating pneumoperitoneum:areviewoftechniquesandcomplications. ObstetGynecolSurv.1998;53:167---74.

22.Motew M, Ivankovich AD, Bieniarz J, et al. Cardiovascu-lar effects and acid---base and blood gas changes during laparoscopy.AmJObstetGynecol.1973;115:1002---12.

23.GreimCA,Broscheit J,Kortlander J,et al. Effects of intra-abdominal CO2-insufflation on normal impaired myocardial function: an experimental study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:751---60.

24.Ivankovich AD, Albrech RF, Zahed B, et al. Cardiovascu-lar collapse during gynecological laparoscopy. Ill Med J. 1974;145:58---61.

26.Barczynski M, Herman RM. A prospective randomized trial on comparison of low-pressure (LP) and standard-pressure (SP)pneumoperitoneumforlaparoscopiccholecystectomy.Surg Endosc.2003;17:533---8.

27.AsifM,SarkarPK. Three-digitAllen’stest.Ann ThoracSurg. 2007;84:686---7.

28.Amaral JLG, Ferreira ACP, Ferez D, et al. Monitorizac¸ão da respirac¸ão:oximetria e capnografia. RevBrasAnestesiol. 1992;42:51---8.

29.Turazzi JC, Bedin A. Sevoflurano em cirurgia videola-paroscópica.RevBrasAnestesiol.1999;49:299---303.

30.FilipovicM,MichauxI,WangJ,etal.Effectsofsevofluraneand propofolonleftventriculardiastolicfunctioninpatientswith pre-existingdiastolicdysfunction.BrJAnaesth.2007;98:12---8.

31.Filipovic M, Wang J, Michaux I,et al. Effects of halothane, sevoflurane,andpropofolonleftventriculardiastolicfunction inhumansduringspontaneousandmechanicalventilation.BrJ Anaesth.2005;94:186---92.

32.Dobson AP, McCluskey A, Meakin G, et al. Effective time to satisfactory intubation conditions after administration of rocuronium in adults. Comparison of propofol and thiopen-toneforrapidsequenceinductionofanaesthesia.Anaesthesia. 1999;54:172---97.

33.DershwitzM,MichałowskiP,ChangY,etal.Postoperativenausea andvomitingaftertotalintravenousanesthesiawithpropofol andremifentaniloralfentanil:howimportantistheopioid?J ClinAnesth.2002;14:275---8.

34.Thomson IR, Harding G, Hudson RJ. A comparison of fen-tanyl and sufentanil in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2000;14: 652---6.

35.Kaba A, Joris J. Anaesthesia for laparoscopic surgery. Curr AnaesthCritCare.2001;12:159---65.

36.Abu-RafeaB,VilosGA,AhmadR,etal.High-pressure laparo-scopicentrydoesnotadverselyaffectcardiopulmonaryfunction inhealthywomen.JMinimInvasiveGynecol.2005;12:475---9.

37.HypólitoO,AzevedoJ,CaldeiraFLA,etal.Creationof pneu-moperitoneum:noninvasive monitoring of clinicaleffects of elevatedintraperitonealpressurefortheinsertionofthefirst trocar.SurgEndosc.2010;24:1663---9.

38.Gándara V, Vega de DS, Escriú A, et al. Acid-base bal-ancealterationsinlaparoscopiccholecystectomy.SurgEndosc. 1997;11:707---10.

39.IwasakaH,MiyakawaH, YamamotoH.Respiratorymechanics andarterialbloodgasesduringandafterlaparoscopic chole-cystectomy.CanJAnaesth.1996;43:129---33.

40.Pearce DJ. Respiratory acidosis and subcutaneous emphy-sema during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:314---6.

41.IshizakiY,BandaiY,ShimomuraK,et al.Changesin splanch-nicbloodflowandcardiovasculareffectsfollowingperitoneal insufflationofcarbondioxide.SurgEndosc.1993;7:420---3.

42.ListerDV,Rudston-BrownB,WrinerB.Carbondioxide absorp-tionis notlinearly relatedto intraperitonealcarbon dioxide insufflationpressureinpigs.Anesthesiology.1994;80:129---36.

43.Mullet CE, VialeJP, Sagnard PE. Pulmonary CO2 elimination duringsurgical proceduresusingintraorextraperitonealCO2 insufflation.AnesthAnalg.1993;76:622---6.