„Revista română de sociologie”, serie nou , anul XXVII, nr. 3–4, p. 279–299, Bucureşti, 2016

Creative Commons License Attribution-NoDerivs CC BY-ND

THE POPULATION IN THE APUSENI MOUNTAINS AREA:

PAST, PRESENT AND PERSPECTIVES (1900–2030)

IOAN PL IAŞ* MIRCEA ANDREI SCRIDON,

L CR MIOARA RADOMIR

ABSTRACT

Among the phenomena that drew attention to the Apuseni Mountains area, the population dynamics recorded over time has a prominent place. The present article carries out research regarding the evolution of this phenomenon over the last 110 years. The information the article relies upon was gathered from the censuses that were started in 1900 and continued in the years 1910, 1930, 1941, 1956, 1966, 1977, 1992 and 2011. The problem that requires attention nowadays concerning the population of the Apuseni Mountains is the constant and gradual population decline, which registered different intensities in all villages of the area included in the perimeter. The period we analyze witnessed different types of intervals: some of them were characterized by significant increases in population, others by relative stagnations and the last ones (since the 1966 census) by a dramatic reduction in the number of inhabitants. The demographic decline which has taken place in the Apuseni Mountains area over the last 60 year has, among other consequences, that of modifying the age structure of the population in an unfavorable direction with regards to the population stability in the area on the medium and long term. The changes in the population structure have led, and will continue to do so, to acceleration in the demographic decline over time. As it stands, the prognosis for the year 2030 underlines an increasingly worrisome situation.

Keywords: population dynamics, demographic phenomena, depopulation, population age structure, demographic decline.

INTRODUCTION

On approximation, the mountainous regions in Romania occupy over a third of the total national territory (37,9%) and account for over 15,4% of the population in their 824 administrative centers (744 counties and 80 cities and municipalities),

*

which include 3,580 villages (Rey, 2010, p. 86). Among them, the Apuseni Mountains area accounts for 15% of the mountain dwelling population, 22% of the agricultural land and 31% of cultivable area, with its 850 villages organized inside

122 communes (Pl iaş, 2013, p. 91). The extent of the mountain areas (Table 1),

their role in Romania’s economic and social life and, also, the number of people

living there (Table 2), signify the importance of the region to any national

development strategy.

Table 1

The number and total surface area of the counties included in the study

County Number of communes

Total surface area

(ha)

The county’s share in the total surface

area (%)

Cultivated surface area (ha)

The county’s share in the total cultivated surface

area (%)

Alba 37 303,235 27.0 129,611 26.1

Arad 13 137,836 12.3 46,768 9.4

Bihor 27 241,147 21.5 112,696 22.7

Cluj 20 232,234 20.6 120,197 24.2

Hunedoara 17 153,783 13.7 54,081 10.9

S laj 8 54,972 4.9 32,934 6.6

Total 122 1,123,207 100 496,287 100,0

The Apuseni Mountains area have been one of the earliest places with a human population, as it was proven in a significant number of studies, reports, dissertations and communications on the area and its population, which were written in several scientific domains (history, archeology, sociology, economy, biology, ethnographical studies, anthropology, medicine and linguistics).

What is specific to the Apuseni Mountain area is the extend of the human settlements up to 1,300–1,350 m altitude (Miftode, 1978) as a result of the gentle incline of the cliffs, which does not appear anywhere else in the Carpathian Mountains. This domestication of the mountain was initiated through „deforestation, by needs and means, the result being a void, a clean place, used for creating a household and its dependencies, which then turned into pastures and cultivated areas. A more numerous family created another void, for another household and so, by successive steps a grove was created, which included all the members of the family with a common ancestor, common name, name that was then given to the location which turned into a village with a pastoral and forest based economy”(Toth, 1965, p. 102).

Once all the available space has been occupied by the local population and

the properties – called „seşii” became so fragmented that they couldn’t sustain a

Table 2

The total population of the counties included in the study (census of 2011)

County Number of communes in the Apuseni Mountains area County’s total population (people)

Population in the Apuseni Mountains area /

county (people)

The share of the population in the Apuseni Mountains area in the county’s total

population (%)

The county’s share in the

population in the Apuseni Mountains

area (%) Alba 37 342,376 86,161 25.2 28.0

Arad 13 430,629 23,185 5.4 7.5

Bihor 27 575,398 77,453 13.5 25.2

Cluj 20 691,106 57,086 8.3 18.5

Hunedoara 17 418,565 45,546 10.9 14.8

S laj 8 224,384 18,518 8.3 6.0

Total 122 2,682,458 307,949 11.5 100.0

Therefore, between the phenomena that represented the region over time, a special place was reserved to the study of the massive increase of the population in the Apuseni Mountains area over time. Eventually, the excess population was absorbed in other areas with a population deficit (Banat, the German areas, The Western Plain where some of the new villages took names found in the Apuseni

area, such as Albacu Nou and Sc rişoara Nou ) or industrialized areas where

workforce was needed.

The excess population occurred even when the material situation of the inhabitants of the Apuseni area was very low. This behavior changed however overtime, and now the demography in the Apuseni Mountains area is in a completely different situation.

The problem that needs to be resolved today, regarding the population in the Apuseni Mountain area, is the constant and progressive population decline, which happened in the last decades at various intensities, by sub-zones and time intervals, in all the rural settlements in the region included in the study. This is a phenomenon that can be seen as well in other mountainous regions of the globe (Brown, 2008).

For all the countries with an interest in mountainology (Gascon and Paşca,

Romanian society. The population present in the mountain areas can help realize at

least the following national objectives (Pl iaş, 2013): a. ensuring the societal use of

natural food producing resources; b. maintaining the normal exploitation potential

of the soil, which is paramount when it comes to ensuring Romania’s general food security, but especially important in times of military or economic crises;

c. contributing to the soil’s protection from corrosion; d. it represents an important,

pollutant-free, natural food source, with an always available internal and external

market; e. contributing to an decentralized habitat; f. participating to the realization

and protection of attractive landscapes; g. it is at the basis of the system for the

protection of traditional cultural goods and values.

Although the agricultural natural resources are economically weaker in the mountain areas, especially when compared with those from the hills and plains areas, because of their extent and their potential as a national food source, they are too important to ignore.

The objectives of the current research are that to determine the population dynamics over the past 11 decades, the age structure of the current population in the Apuseni Mountains area, and to create a prognosis regarding the demographic evolution until 2030.

In most countries the cause for the massive exodus from the mountain area is seen as the existence of a complex gap between the mountain and non-mountain areas, centered on the differences that exist between the personal incomes of the inhabitants. Furthermore, a Swiss study (Leibungut, 1976) proves the existence of a strong parallel between the extent of the personal income gap between the mountain and non-mountain areas and the tendencies and overall depopulation dynamics in the after mentioned areas. Therefore, in the before mentioned study, and many others, the authors consider that one of the solutions to the critical situation presented by depopulation is to significantly increase the inhabitants personal income, by diversifying the available human activities (such as industry, tourism, services and others), modernizing the economy, implicitly the agriculture and the habitat, including here the infrastructure as well.

THE RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

For the current article, the information was provided mainly by nine censuses of the Romanian population, starting with the one performed in 1900 and ending

with the one from 2011 (Pl iaş, 2014). More than that, the research uses data from

To better underline the way in which the population dynamics in a mountain area are dependent on altitude and complementary natural and socio-economic factors, we grouped the communes from the studied area by their placement in the territory by altitude groups, a criterion which was then used to calculate and interpret several indicators. In order to group the communes by altitude groups we

used the study: Climate zoning of farmland soil in R.S.R. – scale 1:500,000

(Raionarea pedoclimatică a terenurilor agricole din R.S.R. – scara 1:500,000), written by the Institute of Pedology and Agrochemical Research in 1972. The administrative territorial delimitation of the region, especially for the five altitude groups identified within it, was done by selecting the communes with the entire or most of the surface area as part of the Apuseni Mountains area, which can be

considered as the region between the Mureş corridor, in the south, and the Someş

corridor in the north, the Transylvanian plateau in the east and the West Plain and Hills in the west.

For complex regional studies (with both a natural and a social and economic point of view) it is imperative to use an administrative territorial delimitation which, in most cases, is not identical with the natural delimitation of the territory. This type of delimitation is necessary since the current study contains social and economic indicators (total population, population density, birthrate, migratory rate, population dynamics, total land use, production indicators, territory usage indicators etc.) which in turn is based on data evidence that is available only on communes level, whose territory extends most of the time over several natural areas (the Apuseni Mountains area and its neighbors). In order to better underline the particularities of the mountain area, there were several communes not included in the study, since most of their territory is outside the studied region, although

their social and economic life is closely linked to the mountain (Ilia, Br nişca,

Soimuş, H r u, Rapoltu Mare, Geoagiu etc.).

Solving this apparently simple problem created several practical difficulties when it came to grouping the territory on altitude levels, because sometimes the difference in altitude between the lowest and the highest point within the territory of one commune is greater than 1,000 m. Considering the way the 122 communes are grouped by altitude, five sub-zones were created:

– low sub-zone (100–600 m), which includes 36 communes, with more than

75% of their territory inside the 100-600 m altitude range;

– mixed-low sub-zone (100–1,000 m), which includes 25 communes, with

more than 60% of their territory under 600 m altitude, while more than 75% of it being situated under 800 m altitude;

– mixed sub-zone (400–1,000 m), which includes 20 communes, with more

– mixed-high sub-zone (600–1,000 m), which includes 20 communes, with more than 75% of their territory inside the 600 and 1000 m altitude range;

– high sub-zone (over 800 m), which includes 21 communes, with more than

75% of their territory over 800 m altitude;

For the rest of the article we will provide a differentiated assessment of the indicators on these five sub-zones, every time the research requires it.

THE RESEARCH RESULTS

THE EVOLUTION OF THE TOTAL POPULATION

The first instances of the census, called “urbarii”, had a fiscal origin and included only the head of the household. They were done in 1652, 1691, 1692, 1698 (the last one known as „nova connumeratio”), 1714, 1715, when they started to get better, and by the 1750 the census was based on more scientific criteria, although only in 1784–1785 they mentioned the number of people.

In those times, as a result of the social and economic conditions, the locals in the Apuseni Mountains area used to hide their wealth and especially their livestock. “The people of the mountain used to hide many things, and even themselves.” (Toth, 1965, p. 102) Hiding goods and even the entire household was how the mountain people fought for survival, by using the forests around them to create new groves and households, even without the knowledge of the local authority. And while living there was tough, they at least had the illusion of freedom.

As a result, the “urbarii” from the Apuseni Mountains area were not the most accurate appraisal of the total population living there. However, one can conclude that between 1692 and 1750 there was a progressive increase in the population in

the area, despite the disasters from that time: “the changes in authority, the

extremely high fiscal taxes, the wrongdoings of the armed forces, and the lack of security inside the country, all of which led to devastation, partial emigration and emptied villages.” (Toth, 1965, p. 102)

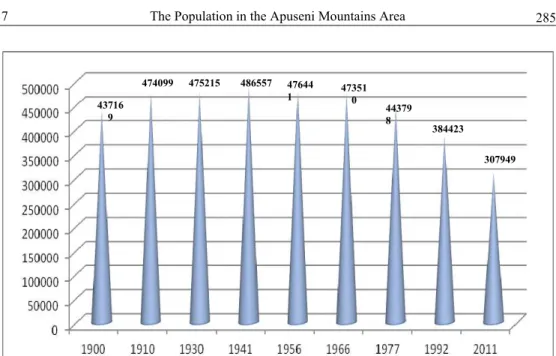

Figure 1 – The population dynamic in the Apuseni Mountains area (1900–2011).

Following the available data for the analyzed period, we can see that in the last 11 decades there have been time intervals when the population increased significantly, sometimes when it stagnated, and the last periods of time starting with the 1966 census, when the population decreased dramatically.

As the graph shows, by the 1992 census the population reached 384,423 individuals, a constant decrease compared to the maximum reached at the beginning of the Second World War (486,557 for the 1941 census), and this tendency continues: the 2002 census records only 350,315 individuals, while the 2011 census shows only 307,949 people. As a conclusion, it can be said that in the last decades the Apuseni Mountains area has experienced an accelerated depopulation process, which meant that by the year 2011 the population was under two thirds compared to the value registered before the Second World War and only 80.1% of the value registered at the end of the communist regime. The graph in

Figure 1 underlines the fact that decrease in the population from the mountain area is without precedent and, if not addressed with suitable recovery strategies, it could lead to total depopulation.

The depopulation of the Apuseni Mountains area started over six decades ago, yet became accentuated only after the political changes following the 1989 Revolution, changes that were added to the economic and social factors influencing the area (the existence of an inequality complex between the mountain and non-mountain areas) and other reasons (the emancipation of women, the increased cost for raising a child, the reduction of the economic role of children in the household economy, the use of modern contraception, the changes in legislation regarding

43716 9

474099 475215 486557 47644

1 473510

44379 8

384423

abortion, the chances in lifestyle philosophy etc.), not to mention the changes in the demographic behavior of the Romanian mountain population (the increase of social mobility).

The decrease in the number of inhabitants in the Apuseni Mountains area in the last six decades also happened while the country’s population experienced continuous growth. However, lately there has been a decrease of the country’s total population as well, especially in the rural areas, but this is a more recent

development and at a lesser scale (Table 3).

Table 3

The evolution of the population in the Apuseni Mountains area, compared to that of the total population (1900–2011)

The relative variation of the population compared to that of the 1900–1930 period

Area

1900 1910 1930 1941 1956 1966 1977 1992 2011

Apuseni Mountains 100 108,4 108,7 111,3 109,0 108,3 101,5 87,9 70,4 Apuseni Mountains – – 100 102,4 100,3 99,6 93,4 80,9 64,8

Romania – – 100 111,1 122,5 133,8 151,0 159,3 111,4

Inside the Apuseni Mountains area there are also differences regarding the triggering moment for the depopulation phenomenon and the scale on which it has developed over time. To underline this aspect, and starting from causes that generally start the depopulation of the mountain regions (weak soil production potential, rough climate for the agriculture which provides the means for existing, lack of infrastructure and communications, terrain configuration with implications towards work output and possible work means, all these and many more generating a low standard of living for those living on the mountains) and considering the fact that each of these causes are a consequence of altitude, we considered that the population should be investigated based on the altitude sub-zones previously identified (Table 4).

Table 4

The evolution of the population by altitude sub-zones

The relative variation of the population compared to that of 1900 = 100% Altitude sub-zone

1910 1930 1941 1956 1966 1977 1992 2011

100–600m 109,2 108,0 111,4 113,6 117,7 111,5 101,4 81,3 100–1000m 114,6 114,6 114,9 112,1 102,3 99,8 87,7 72,9

400–1000m 107,0 106,4 104,5 99,7 96,1 92,2 74,1 55,5

600–1000m 98,7 97,7 104,9 94,4 97,6 87,1 75,4 53,3

Over 800m 111,8 118,6 122,4 124,7 126,4 112,5 91,4 71,2

The evolution of the numbers in the before mentioned table confirms that the depopulation phenomena started earlier in areas with a higher altitude and it gets more intense with growing altitude, yet altitude, with all its implications is not the only cause for depopulation. Because of this, the group living at over 800 m altitude is in a different situation than the ones in the other sub-zones, being also the one with the more distinct evolution. The fact that the group living in the toughest conditions, when it comes to soil production, has, at least in the beginning of the depopulation phenomenon the lowest migration, confirms what Jonathan Power (cited by Miftode, 1984, p. 150) said when enumerating the causes of the

rural exodus: „the village remains behind when it comes to cultural and civilization

development; the villagers understanding what a city is; the differences between the urban and rural standard of living; the frustration they feels as they come in contact with the city and its lifestyles etc. As long as the rural people didn’t move away from their villages and didn’t know about city life they didn’t consider abandoning their village life. As they became aware of the existence of a different social medium, and especially of its advantages (economic, cultural, social status etc.) the rural people became potential migrators, waiting only for the opportunity to go to better, more favorable regions”. As it appears, this awareness, and the occasion to migrate was made available later for those living more isolated at higher altitudes, who in this case are the group situated in the over 800 m altitude sub-zone.

The experience of other countries (France, Switzerland, Italy) shows that once the mountain dwelling people became aware of their situation, their frustration becomes more apparent as they are more isolated (at a higher altitude), and as a consequence of the massive migration depopulation occurs. This is done mainly by young people leaving to schools and workplaces which can provide them with a better standard of living. And young people leaving an area worsens not only the current demographic situation but also the future one.

The most intense overall depopulation in the Apuseni Mountains area took place in the last five decades, when the number of people decreased by 165,561, roughly 35% of the population existing in 1966.

To better understand the facts, we used the five altitude sub-zones we

previously defined to research their recent demographic evolution (Table 5). What

Table 5

The population’s evolution in the Apuseni Mountains area (1992–2011), altitude sub-zones

Absolute numbers Percentage (1992=100) Altitude sub-zone

altitude 1992 2002 2011 1992 2002 2011

100–600 meters 135,961 125,617 109,096 100 92.4 80.2 100–1,000 meters 83,724 77,702 69,633 100 92.8 83,2 400–1,000 meters 52,737 46,733 39,526 100 88.6 74.9 600–1,000 meters 59,710 53,033 42,214 100 88.8 70.7 Over 800 meters 52,291 47,230 40,742 100 90.3 77.9

Total 384,423 350,315 301,211 100 91.1 78.4

Still, currently the high altitude group is less affected by depopulation, as the decrease in the number of individuals was less intense than that in the other altitude sub-zones. The fact that the phenomenon reacted similarly in both high altitude and low altitude groups should not deceive us with regards of its causes and mechanism. People from low altitude areas have a generally better standard of living and can do a much more diverse number of economic activities compared with those living at higher altitude in the Apuseni Mountains area. Furthermore, they have better access to workplaces and urban services, so they are less inclined to leave their birthplace.

People living at high altitudes, on the other hand, do not have these facilities, so the answer to why they do not migrate too heavily, should be searched elsewhere. There is a distinct possibility that their lifestyle is based on a different set of values and aspiration than that of their low altitude brethren, as a result of the relative isolation in which they are living. Therefore, they are not so mobile, and, more likely, they do not have the same access to all the information needed to migrate, which in turn makes leaving a much more risky alternative. But this is not a stable solution, since anytime the living conditions at high altitude become very rough, it can trigger a migration wave which will cause a drastic reduction of the population, something that may have already happened recently, as the current study will show.

AGE STRUCTURE OF THE POPULATION

A graphical analysis of the 2011 census, putting the male population on the left side and the female population on the right side, by age group will give us the

age pyramid for the analyzed region (Figure 2).

the end result looking like pyramid. Unfortunately, our graphical representation does not look like a pyramid, but more like a diamond. Its base is much more restricted compared with its middle, and, more importantly, it also has a high tendency for getting even smaller. The phenomena captured in this “photograph” of the current demographic situation in the Apuseni Mountains area underline an unnatural state for a demographic situation. The aspects shown in it are of a grave importance not only because of their current level, but also because their tendency shape up an unfortunate future for the region. Currently, there are less young people than they should for a healthy population. Furthermore, their numbers are rapidly declining. If we add to this the changes (Rotariu, 2009, 2010) that happened in the current demographic behavior (the decrease in fertility, birthrate, number of weddings and marriages, and the increase in the number of legal separations), and the growing tendency of the young to migrate, we can conclude that in the Apuseni Mountains area we are losing precisely the element needed to regenerate the population. In other words the area has the most important loses of population from the age group that is most relevant to maintaining a healthy population.

Although the phenomena underlined in the five altitude sub-zones are the same overall, their intensity is significantly different. What needs a special attention is the situation present in the mixed sub-zones, where the population is

most affected from a demographic point of view (Figure 3). As it can be seen, the

percentage of children under five years of age in these regions is only 3.73%, and that of children aged between five and nine years is 4.19%, a situation even worse than that present overall in the Apuseni Mountains area, where children under 5 years of age account for 4.20%, and those aged between five and nine years are 4.68%. To make a broader comparison, at national level, the percentage is 5.19% for children under five years of age and 5.24% for those aged between five and nine years. As it stands, the danger of depopulation is far more present in the mountain region as compared to the national situation. And this is the result of the fact that the migration began earlier in these altitude sub-zones, as compared to the

others we’ve already identified (Pl iaş, 1994).

Figure 3 – The population in the mixed sub-zones in the Apuseni Mountains area, grouped by age and gender, according to the 2011 census Average age.

none of the governments so far showing that they are mindful of Romania’s demographic problems. And while the negative aspects we’ve identified are more developed in the Apuseni Mountains area, the current national demographic situation is not much better (Ghe u, 2007, 2012). We also want to underline that it is not the decrease in the number of inhabitants that is the most troubling aspect, but the structure of the pyramid that is weaker at its base, which shows a weakening natural capacity of the population to reproduce. The decrease in the number of young people, coupled with more numerous old people leads to hard to overcome economic and social situations.

The demography specialists (Trebici and Hristache, 1986) claim that the average age of a population is calculated based on statistics which reflect the age structure of the population by years and not by time intervals.

Table 6

The average age for the population in the Apuseni Mountains area, by altitude, 2011 census

Domain

Average age for the total population

(years)

Average age for the female population

(years)

Percentage of women aged between 15 and 49 years old (%)

Romania 40,60 42,1 23,37

Apuseni Mountains total area, of which:

42,44 43,88 21,05

– Low sub-zone (100–600 m) 41,82 43.46 21,39

– Mixed-low sub-zone (100–1000 m) 42,21 43,59 21,00

– Mixed sub-zone (400–1000 m) 44,23 45,98 19,74

– Mixed-high sub-zone (600–1000 m) 43,19 44,71 21,06

– High sub-zone (over 800 m) 41,74 43,28 20,31

Still, when lacking this type of data for the 2011 census, we used a computing artifice in which we used the number of individuals and the median age value for each sub-zone. Although this approach may influence the end results, the differences, whether they are on the positive or the negative side, annul one another, which eventually gives us the correct trend for the research phenomenon, even if the calculated value might differ by 1 or 2 decimals from the real one.

In this case, the data from Table 6 show without any doubt just how high the

THE DEMOGRAPHIC AGING OF THE POPULATION

This indicator is calculated by reporting the number of people over 60 years of age to the number of people up to 20 years of age, and its interpretation is done

by percentage (Table 7). When this ratio, which shows demographic aging, is equal

or greater than 52%, the population is considered to be very aged. By comparing the values from the table below with the threshold of 52%, we can understand just how grave is the demographic situation in the Apuseni Mountains area, since an indicator of 125,92% highlights an extremely aged population. Even in this case, the mixed sub-zone is the worst with a value of 154,64%. We should also mention that even on national level the indicator is evolving in a negative direction, but the aging phenomenon is far less advanced.

Table 7

The demographic aging of the population

Demographic aging (%) Dependency ratio (‰) Domain

+60/–20 –20+ 60/rest of the population

Romania 92,82 779,57

Apuseni Mountains total area, of which: 125,92 890,95

– Low sub-zone (100–600 m) 115,84 876,53

– Mixed-low sub-zone (100–1000 m) 125,26 882,25

– Mixed sub-zone (400–1000 m) 154,64 941,46

– Mixed-high sub-zone (600–1000 m) 135,65 886,81

– High sub-zone (over 800 m) 115,66 917,67

Compared with 1st of July, 1993 when our demographic aging indicator had a

value of 52,8% at a national level, the 2011 census revealed a value of 92,82%. But in the Apuseni Mountains area the situation is incomparably worse. Because of this, we have a very high dependency ratio, when compared with the one at a national level, its value almost becomes 1 on 1 for the mixed sub-zone from the Apuseni Mountains area. This ratio shows the economic burden supported by the adult population in order to support the young and the old, who, in general, are not economically active.

underline the fact that for many settlements the aging process is at a very advanced stage, so advanced, in fact, that total depopulation is imminent.

Specifically, the current demographic situation is the accumulated result stemming from the direct action of three important factors (birthrate, mortality and external migration). The decrease in birthrates is not something that happens only

in mountain areas. As Jean Claude Chesnais (1986) said, “the fertility changes are

but an aspect of the great transformations which affect contemporary society, demographic evolutions are transnational and more and more on a global scale, just like the evolution of ideas, fashion and technology.” From the three factors previously mentioned, the decrease in birthrates has the more important implications and it is also the hardest to control when it comes to demographic decline, as it is a contributing negative factor not only to the current population, but also to the future evolution of the number of individuals, by disturbing the age structure. Still, external migration should not be ignored either. External migration contributed not only to the decline of the current population, but, by having most of the young people leaving, it has influenced the structure of the fertile population, which in turn affected the birthrate and implicitly the future age structure in the area.

Table 8 shows that lately, the high sub-zone has had the most worrisome depopulation as a result of the massive migration from the area. Here, the phenomenon took place later than in other sub-zones where, although the people had access to higher quality food resources, they had also realized much sooner that they could achieve a better standard of living by migrating elsewhere. Still, the depopulation is accentuated, especially in the higher altitude areas, and it will get worse unless measures are taken to encourage to population to remain in the region.

Table 8

The comparative evolution of demographic phenomena by altitude sub-zones

Average natural growth Average migratory

growth Average total growth Altitude

sub-zone

1981–1990 2008–

2010 1981–1990

2008-2010 1981–1990 2008–2010

100–600 m –0,6 –6,9 –5,1 –1,7 –5,7 –8,6

100–1 000 m –2,2 –7,7 –8.8 2,0 –11,0 –5,7

400–1 000 m –3,5 –9,4 –10,8 –1,1 –14,3 –10,5

600–1 000 m –0,4 –8,0 –11,2 –9,3 –11,6 –17,3

Over 800 m 4,9 –6,0 –17,3 –7,1 –12,4 –13,1

ApuseniTotal –0,5 –7,5 – 9,4 –2,6 – 9,9 –10,1

degradation of the social and economic situation in the region, and as a consequence to an almost total depopulation.

The most sensible indicator with regards to structural changes, as it is mostly

dependent on population aging, is the mortality gross rate (15,2‰). Also, another

indicator that can influence the total number of individuals at a certain moment in time

is the infantile death rate (deceased up to 1 year old reported to the number of live

births in a calendar year), rate which has a value a bit higher in the area (12‰) than the national average (10,3‰) in the three years worth of data included in the study.

Considering the poor situation of the studied area for both dimensions (low birthrate and high mortality), it is obvious that the standardized value of the

average natural growth can only be negative. And, as it can be seen from Table 8,

this is actually the case in the region: the population in the Apuseni Mountains area is decreasing by this natural process of birthrates and mortality as well, on average by 7,5 individual to every 1,000.

Moreover, in the three years we’ve analyzed, the Apuseni Mountains area had a negative migration score (including here both population exchanges with

other regions of the country and the external migration), the average migration

rate being – 2,6‰.

The gravity of the depopulation of the Apuseni Mountains area is accentuated by the fact that, as foreign literature has already successfully stated (Egger, 1992), once a mountain area loses its population there are no viable solutions to repopulate it with inhabitants willing to take on all the responsibilities currently attached to mountain households. The experience from other countries has shown that repopulating the mountain regions with individuals coming from non-mountain areas is not a viable solution (Christians, 1991). All this means that there is only one possible strategy for the recovery of the population in the mountain area: increase in natural fertility combined with a massive reduction of external migration. However, the evolution of external migration is unpredictable, as it depends directly on the economic and social evolution of the zone. Our presumption is that people will continue to migrate from the area in the following years as well, which in turn will make the demographic situation in the Apuseni Mountains even worse.

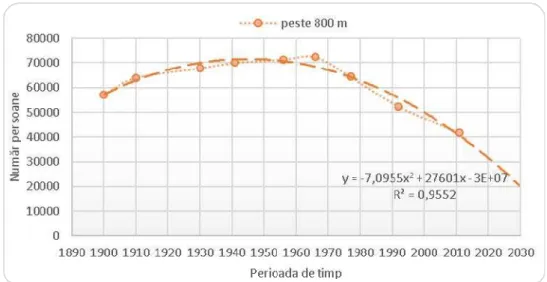

Population prognosis (2015–2030). By using as computing basis the data

acquired from the censuses (1900–2011) we created, by the least squares method, a prognosis for the evolution of the population in the Apuseni Mountains area for the next 15 years.

The curve in Figure 4, which was modelled after the evolution in the 1900–

Figure 4 – Evolution of the total population in the Apuseni Mountains area (1900–2030).

The high degree of depopulation identified in the mixed sub-zone in the last decades, more pronounced than the overall one, will lead to an even more drastic reduction in the number of inhabitants, so that by 2030 the sub-zone might have

only 21,735 people living there (Figure 5), that is 46,1% less than the numbers

living there in 2011. As the analysis has shown, the depopulation phenomenon gets progressively worse, “feeding” on itself, and becoming both a cause and a consequence with effects similar to the factors which previously led to depopulation, as the ones who will leave first are the young people.

Figure 5– Evolution of the population in the mixed altitude sub-zone (1900–2030). 600000

500000

400000

300000

200000

100000

N

u

m

r

pe

rsoa

n

The isolation, the lack of communication, infrastructure, of information and contact with the aspects of the modern and more economically developed world made the inhabitants of the high altitude sub-zone from the Apuseni Mountains area to understand later that there are better alternatives to the standards of living that they were accustomed to. Because of the rough living conditions in the area (poor soil, rough climate, lack of infrastructure and services, great distance to reach the minimum services they might need etc.), once they realized they had better alternatives for living, they started an accelerated depopulation of the area located at over 800 m altitude in the Apuseni Mountains, that will eventually be greater than the one present in lower altitude regions. The calculations show that by the year 2030, this sub-zone will have only 20,198 inhabitants, 51,6% less than the ones accounted for with the 2011 census.

Figure 6 – Evolution of the population in the high altitude sub-zone (1900–2030).

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the study of the population dynamic and age structure in the Apuseni Mountains area, we have reached the following conclusions:

– in the current period, the population in the studied region is at its lowest point in the last 11 decades;

– the rhythm in which the demographic situation from the Apuseni Mountains area degraded is extremely worrisome;

– nowadays, the population is dangerously aged, especially in the mixed sub-zone;

– the “demographic pyramid” has a dangerously narrow base, which signifies an important reduction of the number of young people, and implicitly an increase in the ratio of older people, with all the negative consequences which can spring from it (lower birthrates and fertility, lower number of women in their fertile years, higher mortality rates and dependency ratio);

– the average age and the ratio between the number of individual over 60 years of age and that of the population younger than 20 years, explicitly shows just how aged is the population in the Apuseni Mountains, with differences from one altitude sub-zone to another;

– the decrease of the population takes place not only because of lower birthrates, but it is also due to higher migration and mortality rates, as a general result of population aging;

– the main cause for the registered exodus of young people is the low standard of living, based on very low income coming from agriculture, which is the central economic activity in the area. To that, we can add as causes: the impossibility of supplementing the income with complementary activities due to their inexistence; the total or partial absence of infrastructures; the feeling of frustration generated by isolation and the perception that mountain inhabitants have been abandoned by the society etc.

– the projected prognosis shows a significant increase in the depopulation of the Apuseni Mountains area for the following years;

– the Romanian society should intervene, through its authorities, in order to stop this depopulation process;

– there should be no more delays in creating and implementing a strategy to encourage people to remain in the area. Even if we passed the point of no return, it is still worthwhile to implement an urgent strategy that will help avoid a total and irreparable depopulation.

reproduction. Without at least one component directed at stopping the current demographic decline in the region, any economic development strategy for the area would be incomplete and would fall short on the long term. Delays in implementing this type of strategy will lead, most certainly, to the worsening of the current demographic situation and implicitly to higher costs for future interventions.

Romania’s interest regarding the capitalization of its natural resources in its mountain areas should be promoted in every long term policy, starting with a thoughtful demographic strategy for these regions, which should be supported by economic and social development, necessary to give the people living there an optimistic view of their future. Capitalizing the natural resources (agriculture, forestry, services, environmental protection etc.) cannot be done without the presence of people in the area, people who are at the right number and structure, by age and gender (education, religion, maintaining the local traditions and values, social life etc.)

It has become apparent the need for creating and implementing alternative projects which can, in turn, deliver solutions for revitalizing the mountain areas which are now experiencing demographic, social and economic decline. These projects should focus on improving the standard of living for the local residents. When elaborating a strategy for durable development of the Apuseni Mountains, the local population should be its central component. The solutions should provide with a substantial increase in individual income, habitat and infrastructure modernization and diversification of the available economic activities.

REFERENCES

1. BROWN, R.L. (2008). PLAN B 3.0 General mobilization for saving civilization, Technical Publishing House: Bucharest.

2. CHESNAIS, J.C. (1986). La transition démografique. Etapes, formes, implications économiques. Etude de series temporelles relatives à 67 pays, Press Universitaire de France.

3. CHRISTIANS, C.H. (1991). “Les regions defavorisées en Europe”, Buletin de la Société Géografique de Liége.

4. EGGER, U. (1992). Sustainable Development in Rural Areas, Some Methodological Issues, Zürich: ETH – Zentrum 8092.

5. GASCON, H.; PAŞCA, L.A. – Padima seminar (2012). Policies Against Depopulation in Mountain Areas, Seminar on rural youth migrations and employment, Bruxelles: Euromontana.

6. GHE U, V. (2007). Declinul demografic şi viitorul populaţiei României, Editura ALPHA MDN. 7. GHE U, V. (2012). Evoluţia natalităţii şi fertilităţii, [Online] at http://www.insse.ro/, accesed August. 8. HUBNER, B. (2001). The Policy of European Union in Favor of Mountain Human Areas,

“Mountain policies in Europe” International Conference, Bucharest.

9. LEIBUNGUT, H.J. (1976). Ranmordoungspolitiche Aspecte der Wirtschaftaforderung im Schweizerischen Berggebiet, Bern.

10. MIFTODE, V. (1978). Migraţiile şi dezvoltarea urbană, Iaşi: Editura Junimea.

12. PL IAŞ, I. (1994). Agricultură montană-societate: un necesar contract posibil, Cluj-Napoca: Libris.

13. PL IAŞ, I. (2013). “Dinamica fenomenelor demografice în zona Mun ilor Apuseni”, Revista de montanologie, 1.

14. PL IAŞ, I. (2014). “Considera ii privind structura pe vârste a popula iei din zona Mun ilor Apuseni”, Revista de montanologie, 2.

15. REY, R. (2010). Munţii şi secolul XXI, Bucureşti: Academia Român .

16. ROTARIU, T. (2009). “A Few Critical Remarks on the Culturalist Theories on Fertility with Special View on Romania’s Situation”, Romanian Journal of Population Studies, 1, p. 11–32. 17. ROTARIU, T. (2010). “Nonmarital Births in Romania versus Other European Countries – A Few

Considerations”, Studia: Sociologia, 2, p. 37–60.

18. TOTH, Z. (1986). Mişcările ţărăneşti din Munţii Apuseni până la 1848, Editura Academiei Republicii Populare Romania, (1965).

19. TREBICI, V.; HRISTACHE, I., Demografia teritorială a României, Editura Academiei.

20. *** Mun ii Apuseni (1982). Problematica modernizării, optimizării socio-economice, Universitatea “Babeş-Bolyai” Cluj-Napoca

21. *** L’agriculture alpine et ses évolutions entre 2000 et 2007, 2010, Institut de la Montagne, France.

22. *** Dynamics of Depopulation in Mountain Areas: Vulnerability and Teritorial Responses – 16th-20th Century, 2014, European Society for Historical Demography, Alghero.

23. *** Extreme Depopulation in the Spanish Rural Mountain Areas: A Case Study of Aragon in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Countries, Rural History, 2004, 15, 1, p. 149–166, Cambridge University Press, UK.

24. *** Mountain Forum, 2008, Active Marketing Solutions to the Depopulation Problem on Depopulated and Mountain Area, http://www.mtnforum.org/