Artigo

*e-mail: elucas@ima.ufrj.br

EFFECT OF THE STRUCTURE OF COMMERCIAL POLY(ETHYLENE OXIDE-B-PROPYLENE OXIDE)

DEMULSIFIER BASES ON THE DEMULSIFICATION OF WATER-IN-CRUDE OIL EMULSIONS: ELUCIDATION OF THE DEMULSIFICATION MECHANISM

João Batista V. S. Ramalho

Petrobras Centro de Pesquisas, Av. Horácio Macedo, 950, Cidade Universitária Ilha do Fundão, 21941-915 Rio de Janeiro - RJ, Brasil Fernanda C. Lechuga e Elizabete F. Lucas*

Instituto de Macromoléculas Profa. Eloisa Mano, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, CT, Bl. J, Ilha do Fundão, 21945-970 Rio de Janeiro - RJ, Brasil

Recebido em 29/10/09; aceito em 8/4/10; publicado na web em 24/8/10

Water-in-crude oil emulsions are formed during petroleum production and asphaltenes play an important role in their stabilization. Demulsiiers are added to destabilize such emulsions,however the demulsiication mechanism is not completely known. In this paper, the performances of commercial poly(ethylene oxide-b-propylene oxide) demulsiiers were studied using synthetic water-in-oil emulsions and model-systems (asphaltenes in organic solvent). No change in the asphaltene aggregate size induced by the demulsiier was observed. The demulsiication performance decreased as the asphaltene aggregate size increased, so it can be suggested that the demulsiication mechanism is correlated to the voids between the aggregates adsorbed on the water droplets surface.

Keywords: poly(ethylene oxide-b-propylene oxide); demulsiication mechanism; water-in-crude oil emulsion.

INTRODUCTION

Normally petroleum is produced along with water containing large amounts of inorganic salts. These two phases are dispersed one into the other and form stable emulsions as they are squeezed through the pores in the reservoir and low through the production column and lines. The emulsiication of these insoluble phases occurs by the shear induced during low and by the indigenous surfactant species existing in crude oil, which are adsorbed at the water droplet surface and form a physical barrier that prevents the water droplets from coalescing. The water-in-oil emulsion type, i.e. water droplets dispersed in crude oil, is preferably formed because of the amphiphilic characteristic of these natural surfactants is mainly lipophilic.

Water and salts bring serious problems to the reinery processes, such as corrosion, scaling and impeded activity of some catalysts, which are used to crack bigger molecules into smaller ones.1-6

Due to the complex composition of crude oils, it is common to characterize each crude oil in terms the four SARA-fractions: satura-tes (S); aromatics (A); resins (R); asphaltenes (A).7 The asphaltenes are deined as the crude oil fraction insoluble in high apolar light n-alkanes, such as n-pentane or n-heptane, and soluble in low polar solvents, such as benzene and toluene. The resins comprise the frac-tion soluble in n-pentane and n-heptane but insoluble in propane. The asphaltene macromolecules are generally distinguished by having fused aromatic rings carrying aliphatic chains and rings containing some polar functional group such as sulide, aldehyde, carbonyl, carboxylic, amine, amide and some metals like nickel, vanadium and iron, which confer polarity and amphiphilic characteristics to these macromolecules. The resins have similar molecular structure to the asphaltenes, but they are smaller, have fewer aromatic rings, functional groups and metals. The asphaltene macromolecules inte-ract with each other by the π-bond overlap of fused aromatic rings, hydrogen bonding and Lewis acid-base interactions, leading to their aggregation. It is believed that the resins solvate the asphaltene ma-cromolecules and disperse the asphaltenes into smaller aggregates.

It has been suggested that the asphaltene aggregates are adsorbed on the water droplet surface and form a rigid interfacial ilm.8-11

Many researchers have shown that asphaltene and resin fractions have a large effect on the stability of water-in-oil emulsions.11-13 Sjöblom et al. proved that asphaltenes play a great role in water-in-oil emulsion stability. Later they concluded that the stability is strongly affected by the interaction between asphaltenes and resins.14,15 Mingyuan et al. noted that asphaltenes cause water-in-oil emulsions to be much more stable than the resins do and that the emulsion stability is a function of: the aromaticity; the type of functional group existing in the macromolecular structure; and the molecular size of these fractions.16 Mohammed et al. also observed that resins do not yield stable water-in-oil emulsions and they afirmed that asphaltenes mainly contribute to the stability of the water-in-oil emulsions.17 Førdedal et al. showed that resins alone cannot stabilize water-in-oil emulsions and the ratio of resins to asphaltenes is an important factor determining emulsion stability.18 Working with model oil formulated by dissolving different amounts of resins and/or asphaltenes in mixtures of toluene and heptane, MacLean and Kilpatrick correlated the stability of the water-in-oil emulsion with the asphaltene aggregation grade, which is sensitive to the aromaticity of the medium, the ratio of resins to asphaltenes and the polar group concentration. They attributed decreasing water-in oil emulsion stability to the decrease of the asphal-tene aggregate size.19,20 Further works have also correlated the emulsion stability to the asphaltenes aggregation grade.21-25 However, none of these researchers quantiied the asphaltene aggregate size.

of the commercial demulsiiers are polyoxyalkylated alkyl-phenol-formaldehyde resins and polyoxyalkylated glycols. Other compo-nents, such as polyoxyalkylated epoxy resins, polyoxyalkylated amines, polyestereamines and sulfonic acid salts, can be used at lower concentrations. Normally, each crude oil requires the use of a speciic demulsiier formulation, due to the difference in the chemical composition of each oil. The suppliers generally use the bottle test to formulate the best commercial demulsiier formulation for a speciic crude oil emulsion. The demulsiier dosage added to the emulsion in the ield normally varies from 10 to 100 ppm.29-31

A widely accepted theory explains emulsion stabilization by the Marangoni-Gibbs effect.32 When two water droplets approach each other, a surface deformation forms between the droplets and a thin liquid interstitial ilm remains between them. By capillarity, the liquid ilm tends to be drained out and some adsorbed surfactant molecules are carried out from the interface. This surfactant loss generates a tension gradient at the interface. Then, a reverse lux is created in order to re-generate the surfactant concentration at the interface and the interstitial ilm thinning stops. The coalescence between the droplets only will take place with the thinning and the drainage of the interstitial ilm.

Zaprynova et al. determined that the thinness of the ilm is signi-icantly affected by the interfacial tension gradient, which results in a reduction in the mobility of the ilm surface and a decrease in the rate of ilm thinning.33 Mohammed et al. established that the main role of the demulsiier is to enhance the ilm thinning by suppressing the tension gradient at the interface.34 Some works have shown a good cor-relation between the performance of some commercial demulsiiers and the interfacial tension gradient, with the performance improving as the gradient declines.35,36 Nevertheless, Djuve et al. concluded that the reduction of the interfacial tension is one condition, but not alone suficient for eficient demulsiier action.37

Demulsiication is a process in which an emulsion is destabilized by the addition of a demulsiier. Some researchers state that the de-mulsiier replaces the ede-mulsiier at the interface since the interfacial elasticity decreases.38,39 Sun et al. concluded that the demulsiier leaves small voids at the interface after occupying the water droplet surface, which keeps out the emulsiiers from the interface.40 Ese et al. suggested that the demulsiier disperses the asphaltene aggregates like resins do,41 as the images from atomic-force microscopy (AFM) of asphaltene ilms showed an open structure with regions completely uncovered when 100 ppm of demulsiier was added, similar to the effect of resins.42 Aske observed a decline in the baseline of near infrared (NIR) spectra when 10-15 ppm of demulsiier was added to North Sea crude oil and he concluded that the demulsiier had dispersed and reduced the asphaltene aggregate size.43

The main purpose of this experimental work is to contribute to better elucidation of the destabilization mechanism of water-in-crude oil emulsions by the action of emulsion breakers (demulsiiers). Three commercial poly(ethylene oxide-b-ethylene oxide) copolymers, having different molecular structures (linear, star and branched) and different molecular masses were used. Three different crude oils were used in the experimental studies, along with the asphaltene fractions extracted from them. Real systems (crude oil and commercial de-mulsiier base) and model systems (dede-mulsiier base and asphaltenes dissolved in solvents) were studied in order to correlate the demulsiier performance and asphaltene particle size.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

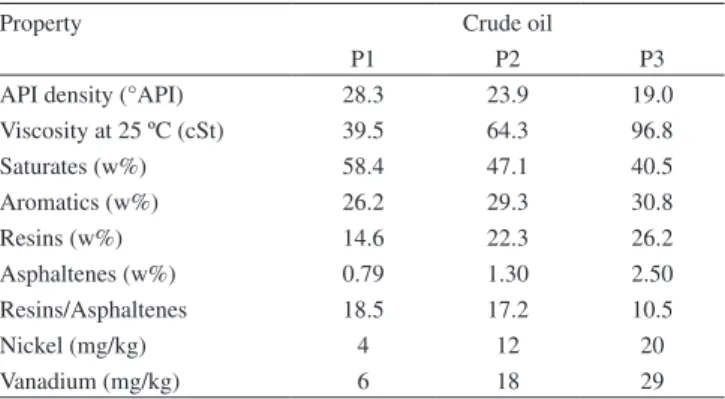

The three Brazilian crude oils were labeled P1, P2 and P3. Table 1 presents some physical and chemical characteristics of the crude

oils44 that were selected in order to predict their tendency in stabilizing water-in-crude oil emulsions.

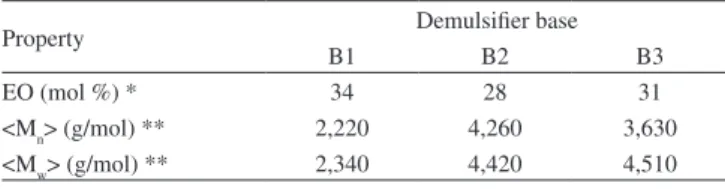

Three commercial demulsiier bases were used in the expe-rimental studies. All of them were constituted of poly(ethylene oxide-b-propylene oxide) copolymers, but having different molecular structures. The commercial demulsiier bases were supplied by Dow Química do Brasil. The base B1 was synthesized by alkoxylation of monopropylene glycol and the macromolecule had a linear coni-guration. The base B2 was synthesized by alkoxylation of glycerin and the macromolecule had a star coniguration. The base B3 was synthesized by alkoxylation of nonyl-phenol-formaldehyde resin and the macromolecule had a branched coniguration.

Methods

Asphaltene extraction and characterization

The asphaltenes were extracted from the crude oils by precipi-tation at room temperature with 40:1 v/v of n-heptane to crude oil volumetric ratio, followed by iltration and exhausted washing with n-heptane, based on the preparation method described in IP 143/01.45 The asphaltenes were labeled as AP1, AP2 and AP3, respectively to the crude oils.

The asphaltene fractions were characterized regarding to: (a) molar mass, by size exclusion chromatography (SEC), using a Wa-ters gel permeation chromatography system (WaWa-ters 600E pump, Waters WISP 717 sample injector and Alltech 2000ES evaporative light scattering detector) and a set of Ultrastyragel columns (7.8 x 300 mm, 103, 500 and 50 Å). Distillated tetrahydrofuran (THF) was used as a solvent (at 0.6 mL/min) and polystyrene solutions in THF as calibration standard. Number average molar mass (<Mn>) and weight average molar mass (<Mw>) were determined. (b) Some heteroatom elements, such as sulfur (S), carbon (C), hydrogen (H), nitrogen (N) and oxygen (O), according to the preparation methods described in ASTM D 1552-03 and ASTM D 5291-02.46,47 (c) Aromatic carbons and saturated, using 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (13C NMR) – Va-rian 400-MR spectrometer, operating at 50.3 MHz, room temperature, pulse angle of 90° (13.0 µs), pulse repetitions of 10 s, spectral width of 12.5 KHz, acquisition time of 1.5 s and 24000 scans. The spectra were acquired from 15% w/v of asphaltene solution in deutered chloroform (CDCl3) containing 0.05M of chrome acetyl acetonate as a relaxation agent. The aromatic carbon peaks were integrated in the interval of 100 and 180 ppm and the saturated carbons peaks were integrated from 0 to 70 ppm. (d) Aromatic hydrogen, using 1H NMR – Varian 400-MR spectrometer, operating at 200 MHz, room temperature, pulse angle of 45° (7.0 µs), pulse repetitions of 1.0 s, spectral width of 3,000 Hz, acquisition time of 1.5 s and 500 scans.

Table 1. Physical and chemical characteristics of the three crude oils (labeled P1, P2 and P3)44

Property Crude oil

P1 P2 P3

API density (°API) 28.3 23.9 19.0 Viscosity at 25 ºC (cSt) 39.5 64.3 96.8

Saturates (w%) 58.4 47.1 40.5

Aromatics (w%) 26.2 29.3 30.8

Resins (w%) 14.6 22.3 26.2

Asphaltenes (w%) 0.79 1.30 2.50 Resins/Asphaltenes 18.5 17.2 10.5

Nickel (mg/kg) 4 12 20

The spectra were acquired from the 5 w/v % asphaltene solution in CDCl3 and C2Cl3 (1:1 v/v). The aromatic hydrogen peaks were integrated in the interval between 6.4 and 9 ppm and the saturated hydrogen peaks integrated between 2 and 6 ppm.

Determination of asphaltene particle size

The size of the asphaltene particles was determined by using a Zetasizer Nano Series particle size analyzer, from Malvern Ins-truments Ltd.48 The extracted asphaltene fractions were studied in model systems constituted of toluene and n-heptane solvent mixtures at different concentrations. To formulate these concentrations, irst 0.25% w/v of each asphaltene was dissolved in toluene (T). After that, the organic phase was built up by adding 0.025% w/v of the dissolved asphaltenes to toluene and to the volumetric mixtures of toluene and n-heptane (H) in proportions of 4:3, 3:4, 2:5 and 1:6.

The effect of the commercial demulsiier bases on the asphaltene aggregation was also quantiied. 0.0050% w/v of the asphaltenes was added to the volumetric mixtures of toluene and n-heptane in proportions of 3:4 and 2:5. Each demulsiier base was added at the dosage of 50 ppm of active-material.

Characterization of the poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(propylene oxide) block copolymers

Each commercial demulsiier base was characterized in relation to: (a) molar mass by SEC, using the same equipment and conditions described in the preceding item; (b) the percentage of ethylene oxide, by 13C NMR, using a Varian 400-MR spectrometer, operating at 75.4 KHz. The spectra were acquired from the 40 w/v % demulsiier base solution in CDCl3. The carbon peaks were in the intervals: 16-20 ppm and 69-76 ppm.49

Demulsiication tests

The demulsiication tests were carried out using a synthetic water-in-oil emulsion. Two different organic phases were used: crude oil and asphaltenes in an organic solvent.

The water-in-oil emulsions were synthesized from the three crude oils to have 30.0 v/v % of water content. The aqueous phase was a 50 g/L NaCl solution. One liter of each emulsion was prepared by shearing the luids in a Polytron PT 3100 homogenizer, at 8000 rpm for 3 min.50 The emulsion demulsiication was evaluated by bottle tests. 100 mL of emulsion was previously heated at the assay tempe-rature before adding 100 µL of 50 w/v % demulsiier base solution in toluene, which corresponds to ~50 ppm of active-material of the demulsiier base (B1, B2 or B3) added to the emulsion. Each demul-siier base solution was prepared by dissolving the polymer in toluene at the concentration of 50 w/w %. The assay temperature was that at which the oil had a viscosity of 16 cSt. Such viscosity is used as standard for measurements in the Petroleum Industry. Using a DV-III Ultra programmable rheometer with spindle SC-18 (Brookield, Inc.), the 16 cSt viscosity was observed at 40, 64 and 97 °C, respectively, for P1, P2 and P3. After preparing each emulsion, a Matersizer 2000 particle size analyzer (Malvern Instruments Ltd.) was used to quantify the water droplet size. The separated water volume was quantiied during 40 min at every 5 min and the demulsiication performance was quantiied by calculating the water separation index (WSI):

where SW is the separated water (%) and N is the number of measures of the separated water.

For the tests in which the oil phase consisted of asphaltenes in organic solvent, we used 0.025 w/v % of asphaltenes in toluene and

mixtures of toluene and n-heptane in volumetric proportions of 4:3, 3:4, 2:5 and 1:6. The aqueous phase remained a 50 g/L NaCl solu-tion. The demulsiication performance was evaluated with the model emulsions prepared under the same conditions described before, but they were sheared at 8,000 rpm for 1 min. The separated water was measured during of 40 min at room temperature after adding 50 ppm of active-material of demulsiier base B1 to the emulsion.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Commercial demulsiier base characterization

Table 2 presents the chemical characterization of these com-mercial bases. The results show that the demulsiier bases have very similar ethylene oxide (EO) content (~30 mol %). The average molar masses of the star and branched structures (4,260 and 3,630 g/mol, respectively) are almost twice those of the linear one (2,220 g/mol). As expected, the polydispersity values are quite low since the products are industrially prepared by ionic polymerization.

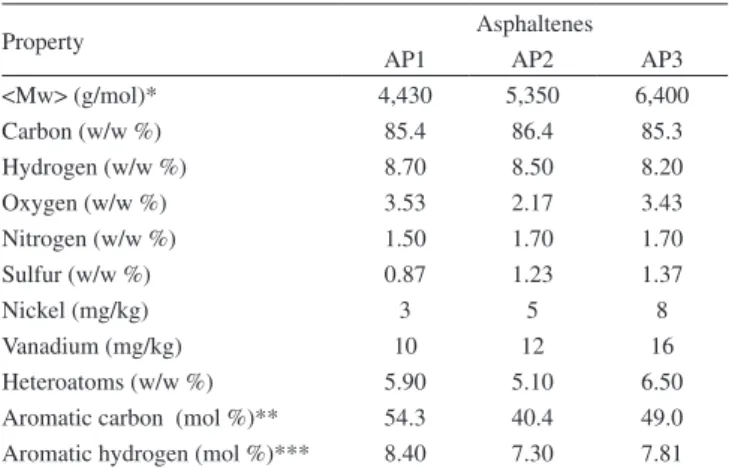

Asphaltene characterization

The chemical characteristics of the three asphaltenes (AP1, AP2 and AP3) were determined in order to predict their tendencies to form aggregates and to stabilize water-in-oil emulsions. Table 3 shows the results of weighted average molar mass (<Mw>) and the content of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, nickel, vanadium, heteroa-toms, aromatic carbon and aromatic hydrogen. The molar mass found for AP1, AP2 and AP3 were, respectively, 4,430; 5,350 and 6,400 g/ mol. The molar mass for AP3 is about 50% higher than that for AP1. In fact, such values are some higher than that suggested by the recent literature51 and, in fact, could already express the aggregate tendency of asphaltenes. The carbon and hydrogen contents were quite similar for the three asphaltene fractions: 85 and 8.5 w/w%, respectively. The nitrogen, sulfur, nickel and vanadium concentrations followed the same tendency as molar mass, i.e., they increased from AP1 to AP3. The oxygen, aromatic carbon and aromatic hydrogen concentrations increased in the following order: AP2 < AP3 < AP1. These results show the asphaltenes had different characteristics.

Demulsiier base performance for water-in-crude oil emulsions

The demulsiication performances of the three commercial de-mulsiier bases were evaluated to study the effect of the molecular structure on the demulsiication mechanism. Table 4 summarizes the assay conditions. It shows that the emulsions were synthesized having similar average water droplet diameters (~10 µm) and that the demulsiication took place at the temperature at which the oil continuous phase presented similar viscosity values (~ 16 cSt).

The results obtained for the demulsiier base performances, for demulsiication of the water-in-crude oil emulsions prepared from the three different crude oils (P1, P2 and P3). Showed that the best performances were obtained from the systems prepared using P2 crude oil (80% of separated water in about 20 min), followed by the

Table 2. Demulsiier base chemical characterization

Property Demulsiier base

B1 B2 B3

EO (mol %) * 34 28 31

P1 emulsion system (45-70% of separated water in about 20 min). The worst performances for the three different demulsiier bases were observed for the P3 crude oil system (5-35% of separated water in about 20 min). The performances of the three demulsiier bases were quite similar when used to separate the P2 crude oil emulsions: more than 90% separated water. For the P3 crude oil emulsions, the performances were quite different: 10, 33 and 50% for B1, B2 and B3, respectively.

By analyzing only the crude oil characterization data (Table 1) it could be suggested that crude oil P1 (28.3ºAPI) should have the lowest tendency to form stable water-in-crude oil emulsions than the crude oil P2 (23.9ºAPI) and crude oil P3 (19.0 ºAPI), respectively, since crude oil P1 has lower asphaltene content, higher ratio of resins to asphaltenes and the lower metal content (Ni, V) than the other two crude oils. Likewise, crude oil P3 should have the highest tendency to form more stable emulsions, since it is the most viscous crude oil, has the highest asphaltene content, lowest ratio of resins to asphal-tenes and highest metal content (Ni, V). In fact, the demulsiication

performance of the commercial demulsiier bases B1, B2 and B3 in the destabilization of the water-in-crude oil emulsions indicated that crude oil P3 produced the most stable emulsions. Nevertheless, crude oil P1 formed more stable emulsion than that prepared from crude oil P2, both having the same viscosity (~ 16 cSt).

On the other hand, the asphaltene chemical characterization (Table 3) showed that asphaltenes from crude oil P1 (AP1) had higher aromatic carbon, hydrogen and heteroatom (O, N, S) content than the asphalte-nes from crude oil P2 (AP2). These analytical results suggest that the asphaltene macromolecules from crude oil P1 contain more aromatic rings and functional groups in their structure than the asphaltene macro-molecules from crude oil P2, which may contribute to higher polarity to the asphaltene macromolecules from crude oil P1. They also suggest that asphaltene macromolecules from the crude oil P1 interact chemically with each other more intensely than do the asphaltene macromolecules from crude oil P2 and produce larger asphaltene aggregates and more rigid asphaltene interfacial ilms, which yield more stable water-in-crude oil emulsions for crude oil P1 than for crude oil P2, at the same organic phase viscosity. Although the asphaltenes from crude oil P3 (AP3) have lower aromatic carbon and hydrogen content than the asphaltenes from crude oil P1 (AP1), the asphaltene macromolecules from crude oil P3 have the highest heteroatom (O, N, S) content, which contributes to form larger and more cohesive asphaltene aggregates for AP1 and AP2, due to the higher intermolecular interaction forces induced by the functional groups. In fact, crude oil P3 rendered a more stable water-in-oil emulsion than crude oils P1 and P2, since its emulsion exhibited the lowest water separation index (WSI) values. To summarize the results observed for demulsiier performance in water-in-crude oil emulsions, the stability of water-in-oil emulsions exhibits the following order: P3 > P1 > P2.

Asphaltenes particle size as a function of solvent aromaticity

The asphaltenes were added to organic phases with different aromaticity degrees to produce aggregates with different sizes. Figure 1 shows the mean asphaltene particle sizes and size distribution per-centage for the three different asphaltenes in model solvents (toluene and n-heptane, T:H, at different compositions). The results were quite similar for the three model systems prepared using asphaltenes AP1, AP2 and AP3. At 0.025 wt% of asphaltenes in toluene, no particles were observed using the Zeta Sizer Nano Series analyzer. That was expected, since toluene is a good asphaltene solvent and there is no tendency to aggregation at low concentration.52 When the moiety became more polar (T:H = 4:3 and 3:4), it was possible to observe particles around 10 and 20 nm, respectively.

Asphaltene aggregates (around 2,000 nm) could be observed when 0.025 wt% of asphaltenes were in contact with toluene: n-heptane at proportions of 2:5 and 1:6. The asphaltene particles size increased as

Table 3. Asphaltene chemical characterization

Property Asphaltenes

AP1 AP2 AP3

<Mw> (g/mol)* 4,430 5,350 6,400

Carbon (w/w %) 85.4 86.4 85.3

Hydrogen (w/w %) 8.70 8.50 8.20

Oxygen (w/w %) 3.53 2.17 3.43

Nitrogen (w/w %) 1.50 1.70 1.70

Sulfur (w/w %) 0.87 1.23 1.37

Nickel (mg/kg) 3 5 8

Vanadium (mg/kg) 10 12 16

Heteroatoms (w/w %) 5.90 5.10 6.50 Aromatic carbon (mol %)** 54.3 40.4 49.0 Aromatic hydrogen (mol %)*** 8.40 7.30 7.81 *Determined by SEC. **Determined by 13C NMR. ***Determined by 1H NMR

Table 4. Crude oil demulsiication assay conditions

Parameter Crude oil

P1 P2 P3

Water content (v/v %) 30.0 30.0 30.0 Water droplet mean size (µm) 10.90 9.51 9.78 Separation temperature – T (°C) 40.0 64.0 97.0 Crude oil viscosity at T (cSt) 15.7 16.1 16.4 Demulsiier active-material (ppm) 50 50 50

the n-heptane content in the solvent mixture increased and was inde-pendent of the type of asphaltene used (AP1, AP2 or AP3). The particle size increase was much more pronounced when the solvent mixture composition was changed from T:H = 3:4 to T:H = 2:5.

So, by analyzing the asphaltene aggregate size (Figure 1), induced by the addition of n-heptane to the asphaltene in toluene dispersion (at a proportion of T:H = 2:5 and 1:6), it is observed the same order as that for emulsion stability in Figure 1, that is, the asphaltene aggregate size order was P3 > P1 > P2. Figure 1 also shows that the asphaltene macromolecules aggregation degree depends on the aromaticity of the moiety. Decreasing aromaticity causes the aggregate size to increase. This means, that in fact, the aggregate size depends on the solvent’s capability to solvate and to disperse the asphaltene macro-molecules.19,20 No asphaltene particles were detected by analyzing the system containing only asphaltenes in toluene.

Focusing on the performance differences of the demulsiier bases, it is observed that for crude oil P1 the star demulsiier base B2 per-formed best, followed by the linear demulsiier base B1, and inally the branched demulsiier base B3 (B2WSI > B1WSI > B3WSI). However, for crude oil P2, the performance of base B1 was similar to that of base B2, and base B3 performed worst (B1WSI = B2W-SI > B3WB2W-SI). Although the three commercial bases presented very poor performance in demulsiication of the emulsion prepared with crude oil P3, the performance order was: B3WSI > B2WSI > B1W-SI. So, no correlation was found between the molecular architecture (linear, star and branched) of the commercial demulsiier bases and its demulsiication performance on the crude oil emulsions. These results suggest that the demulsiier macromolecule may be chemically interacting with some crude oil component, which causes a decreasing in the demulsiication action of the surfactant.

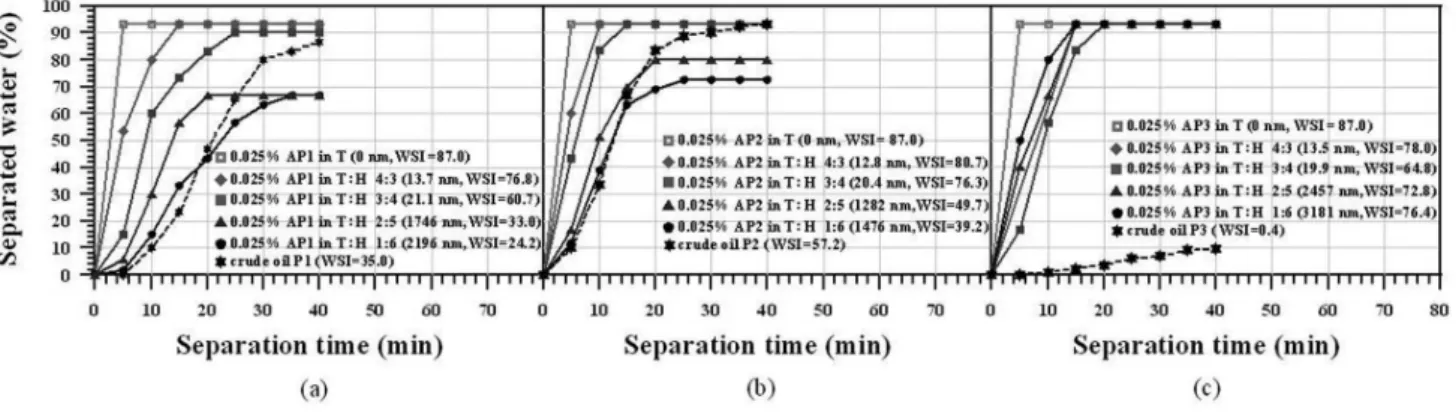

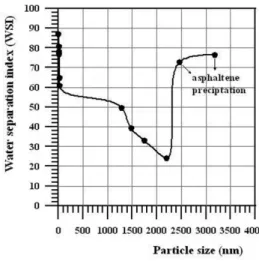

Inluence of asphaltene aggregate size on demulsiication performance

The inluence of the asphaltene aggregate size on the demulsii-cation process was investigated using model water-in-oil emulsions: 0.025 wt % of asphaltenes in solvent mixture (T:H at different compo-sitions). Figures 2a, 2b and 2c show the demulsiication performances of B1 (at 50 ppm) added to the model systems prepared with P1, P2 and P3 crude oil, respectively. For comparison, Figure 2 also shows the B1 performance in water-in-crude oil emulsions. It is clear that the performance was better when testing the model systems, except for the P2 system, in which the performance for crude oil was better than that for the model system having aggregate sizes higher than 1,000 nm.

An analysis of the effect of base B1 on the model systems (asphal-tenes in toluene and n-heptane at several concentrations) showed that

the asphaltenes are indeed able to stabilize water-in-oil emulsions. Figure 2 shows different demulsiication processes, induced by base B1 addition, for each emulsion that was synthesized with different asphaltene kinds and aggregate. These experimental results also conirm that the asphaltene aggregate size plays an important role in the demulsiication mechanism. Furthermore, the demulsiication process was much faster for the model system, which can be related to the viscosity differences and/or some kind of interaction between the surfactant and crude oil components, as supposed at the end of the preceding paragraph.

Effect of the demulsiier bases on asphaltene aggregation

The effect of the commercial demulsiier bases on the asphaltene aggregation was quantiied in order to investigate whether the demul-siier bases change the asphaltene aggregate size like the resins do.41,43 It was measured the asphaltene particle sizes and their size distribution percentages for the model systems prepared with 0.0050 wt % of asphaltenes in T:H = 3:4 and 2:5. The two solvent mixture compo-sitions were selected based on the signiicant difference in particle size observed in Figure 1. In all cases, B1, B2 and B3 demulsiier bases were added at 50 ppm. No signiicant change in particle size was observed after addition of the demulsiier, independently of the molecular structure (linear, star or branched).

Since it was veriied that the asphaltene aggregate size inluen-ced the demulsiication process, some experiments were performed adding demulsiier bases in asphaltene model systems containing smaller (~10 nm) and bigger (~1,000 nm) asphaltene particle sizes, respectively T:H solvent content of 3:4 and 2:5. No changes in as-phaltenes aggregate size were observed when the demulsiier was added, for both small and large particles sizes. This means that the polyoxyalkylated demulsiier bases used in these experimental studies were not able to disperse the asphaltenes as well as resins do.19,20

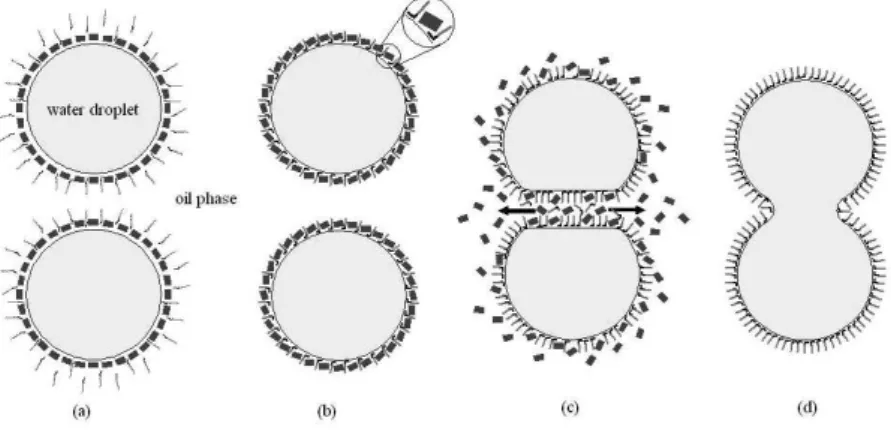

whole demulsiication process. More voids are available with smaller asphaltene aggregate than for larger ones. The emulsion stabilized by the asphaltenes from crude oil P3 (AP3) had its demulsiication performance increased when the asphaltenes aggregates size reached mean sizes of 2,500 and 3,100 nm (Figure 3), because such aggre-gates are too large to be adsorbed at the interface. Under these two conditions asphaltene precipitation was also observed.

Even though, it is possible that other components within the oil sample may inluence the effectiveness of the demulsiier, from experimental results obtained in this work, it is suggested a better understanding of the demulsiication mechanism of water-in-crude oil emulsions. The asphaltene aggregates are adsorbed at the water droplet interface and form a barrier that prevents the water droplets from coalescing. Voids are between adjacent asphaltene particles and the demulsiiers added to the system penetrate through the voids and occupy the vacancies at the surface. Asphaltenes presenting high intermolecular interaction forces form large aggregates and a few voids are available, which impairs the penetration of the demulsiier. The more hydrophilic part of the demulsiier molecule strongly interacts with the water molecules and annuls the interac-tion between the asphaltene aggregates and the water molecules. At this point, the asphaltene aggregates start moving away from the water droplet surface and more demulsiier goes gradually to the surface. The Marangoni-Gibbs effects are suppressed allowing the water droplets to coalesce.

CONCLUSIONS

This study conirmed that asphaltenes in crude oil play an impor-tant role in the stabilization of the water-in-crude-oil emulsions. The demulsiication mechanism depends on the aggregation degree of the asphaltene macromolecules in the crude oil, besides the asphaltene content and the crude oil viscosity. The asphaltene aggregate size depends on the intensity of the intermolecular interaction forces: asphaltene macromolecules with higher interactive forces tend to form larger aggregates. However, the aromaticity of the moiety also inluences the asphaltene aggregation degree, since the highly aromatic moiety can suppress the asphaltene macromolecules’ inte-ractions, reducing the asphaltene aggregate size. The demulsiiers based on poly(ethylene oxide-b-propylene oxide) do not change the asphaltene aggregation degree by peptizing the asphaltene macro-molecule as well as resins do. There is no evidence of correlation between the molecular coniguration (linear, star and branched) of the demulsiiers based on poly(ethylene oxide-b-propylene oxide) and

their performance in the crude oil demulsiication process. It is likely that the demulsiier macromolecule interacts differently with some crude oil components, which cause differences in the demulsiication performance. Demulsiication mechanism could be correlated to the voids left between the asphaltene aggregates adsorbed on the water droplet surface: small asphaltene aggregates generate more voids, making it easier for the demulsiier macromolecule to be adsorbed on the water droplet surface, thus facilitating the demulsiication; similarly, larger asphaltene aggregates prevent the demulsiier ad-sorption at the interface.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The following material is available for free at PDF format at http://quimicanova.sbq.org.br: Figure 1S showing the demulsiier base performance on demulsiication of crude oil (a) P1, (b) P2 and (c) P3; Figure 2S showing the asphaltene aggregate size of (a) AP1, (b) AP2 and (c) AP3 with and without the addition of 50 ppm of active demulsiier base material, at different toluene/heptane ratios; Figure 3S illustrating in simpliied form the voids between the asphaltene aggregates adsorbed at the water droplet surface; and Figure 4S exhibiting a schematic illustration of the demulsiication mechanism of the water-in-oil emulsions proposed in this work.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank FINEP, CNPq, CAPES, FAPERJ, the National Petroleum Agency (ANP) and PETROBRAS for inancial support.

REFERENCES

1. Strassner, J. E.; J. Pet. Technol.1968, 20, 301.

2. Kimbler, O. K.; Reed, R. L.; Silberberg, I. H.; Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1966, 6, 153.

3. Eley, D. D.; Hey, M. J.; Symonds, J. D.; Willison, J. H. M.; J. Colloid Interface Sci.1976, 54, 462.

4. Johansen, E. J.; Skjarvo, I. M.; Lund, T.; Sjöblom, J.; Soderland, H.; Bostrom, G.; Colloids Surf.1989, 34, 353.

5. Schramm, L. L. In Petroleum emulsion: basic principles, in Emulsions: fundamentals and applications in the petroleum industry; Schramm, L. L, ed.; American Chemical Society: Washington, D. C., 1992, cap. 1. 6. Sjöblom, J.; Aske, N.; Aulem, I. H.; Brandal, O.; Havre, T. E.; Saether,

O.; Westvik, A.; Johnsen, E. E.; Kallevik, H.; Adv. Colloid Interface Sci.

2003, 100-102, 399.

7. Sjöblom, J.; Hemmingsen, P.; Kallevick, H. In Asphaltenes, heavy oils, and petroleomics; Mullins, O. C.; Sheu, E. Y.; Hammani, A.; Marshall, A. G., eds.; Springer: New York, 2007, cap. 21.

8. Kilpatrick, P. K.; Spiecker, P. M. In Encyclopedic Handbook of Emulsion Technology; Sjöblom, J., ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, 2001, cap. 30. 9. Aske, N.; Kallevik, H.; Sjöblom, J.; Energy Fuels2001, 15, 1304. 10. Andersen, S. I.; Speight, J. G.; Pet. Sci. Technol.2001, 19, 1. 11. Sheu, E. Y.; Energy Fuels2002, 16, 74.

12. Neumann, H. J.; Paczynska-Lahme, B.; Prog. Colloid Polym. Sci.1988, 77, 123.

13. Sjöblom, J.; Urdahl, O.; Holland, H.; Christy, A. A.; Johansen, E. J.; Prog. Colloid Polym. Sci.1990, 82, 131.

14. Sjöblom, J.; Söderlund, H.; Lindblad, S.; Johansen, E. J.; Skärvö, I. M.; Colloid Polym. Sci.1990, 268, 389.

15. Sjöblom, J.; Urdahl, O.; Borve, K. G. N.; Mingyuan, L.; Saeten, J. O.; Christy, A. A.; Gu, T.; Adv. Colloid Interface Sci.1992, 41, 241. 16. Mingyuan, L.; Christy, A. A.; Sjöblom, J. In Emulsions: a fundamental

and a practical approach; Sjöblom, J., ed.; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Netherlands, 1992, cap. 11.

17. Mohammed, R. A.; Bailey, A. I.; Luckham, P. F.; Taylor, S. E.; Colloids Surf., A1993, 80, 237.

18. Føderdal, H.; Schildberg, Y.; Sjöblom, J.; Volle, J. L.; Colloids Surf., A

1996, 106, 33.

19. MacLean, J. D.; Kilpatrick, P. K.; J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 189, 242.

20. MacLean, J. D.; Kilpatrick, P. K.; J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 196, 23.

21. Schorling, P.-C.; Kessel, D. G.; Rahimian, I.; Colloids Surf., A1999, 152, 95.

22. Spiecker, P. M.; Gawrys, K. L.; Trail, C. B.; Kilpatrick, P. K.; Colloids Surf., A2003, 220, 1309.

23. Fingas, M.; Fieldhouse, B.; Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2003, 47, 369. 24. Havre, T. E.; Sjöblom, J.; Colloids Surf., A2003, 228, 131. 25. Xia, L.; Lu, S.; Cao, G.; J. Colloid Interface Sci.2004, 271, 504. 26. Xu, Y.; Wu, J.; Dabros, T.; Hamza, H.; Energy Fuels2005, 19, 916. 27. Kang, W.; Jing, G.; Zhang, H.; Li; M.; Wu, Z.; Colloids Surf., A2006,

272, 27.

28. Rondón, M.; Bouriat, P.; Lachaise, J.; Energy Fuels2006, 20, 1600. 29. Spencer, E. T.; Chem. Ind.1992, 20, 770.

30. Mohammed, R. A.; Bailey, A. I.; Luckham, P. F.; Taylor, S. E.; Colloids Surf., A1994, 83, 261.

31. Bolívar, C. R. A.; Contreras, P.; Méndes, R.; Tovar, J. G.; Visión Tecnológica2000, 7, 167.

32. Wasan, D. T. In ref. 16, cap. 19.

33. Zaprynova, Z.; Malhota, A. K.; Aderangi, N.; Wasan, D. T.; Int. J. Multiphase Flow1983, 9, 105.

34. Mohammed, R. A.; Baily, A. I.; Luckham, P. F.; Taylor, S. E.; Colloids Surf., A1994, 83, 261.

35. Kim, H. Y.; Wasan, D. T.; Breen, P. J.; Colloids Surf,. A 1995, 95, 235. 36. Kim, H. Y.; Wasan, D. T.; Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1996, 35, 1141. 37. Djuve, J.; Yang, X.; Fjellanger, I. J.; Sjöblom, J.; Pelizzetty, E.; Colloid

Polym. Sci.2001, 279, 232.

38. Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sun, T.; Zhao, S.; Yu, J.; J. Colloid Interface Sci.

2004, 270, 163.

39. Kang, W.; Jing, G.; Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Wu, Z.; Colloids Surf., A 2006, 272, 27.

40. Sun, T.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Peng, B.; Li, M.; Yu, J.; J. Col-loid Interface Sci.2002, 255, 241.

41. Ese, M.-H.; Galet, L.; Clausse, D.; Sjöblom, J.; J. Colloid Interface Sci.

1999, 220, 293.

42. Sjöblom, J.; Johnsen, E. E.; Westvik, A.; Ese, M.-E.; Djuve, J.; Aulem, I. H.; Kallevik, H. In ref. 8, cap. 25.

43. Aske, N.; PhD Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technol-ogy, Trondheim, 2002.

44. PETROBRAS – Research Center, private Database.

45. Standard test methodfordetermination of asphaltenes (heptane insolu-ble) in crude petroleum and petroleum products, Institute of Petroleum, London, IP 143/01, 2001.

46. Standard test method forsulfur in petroleum products (high-temperature method), American Standard Test Methods, West Conshohocken, ASTM D 1552-03.

47. Standard test methods forInstrumental Determination of carbon, hy-drogen and nitrogen in petroleum products and lubricants, American Standard Test Methods, West Conshohocken, ASTM D 5291-02. 48. Ramalho, J. B. V. S.; Oliveira, M. C. K.; Boletim Técnico da

PETROBRAS1999, 42, 72.

49. Mansur, C. R. E.; Lucas, E. F.; Pacheco, C. R. N.; González, G.; Quim. Nova2001, 24, 47.

50. Mansur, C. R. E.; Barboza, S. P.; González, G.; Lucas, E. F.; J. Colloid Interface Sci.2004, 271, 232.

51. Mullins, O. C.; Martinez-Haya, B.; Marshall, A. G.; Energy Fuels2008, 22, 1765.

52. Middea, A.; Monte, M. B. M.; Lucas, E. F.; Chem. Chem. Technol.

Material Suplementar

*e-mail: elucas@ima.ufrj.br

EFFECT OF THE STRUCTURE OF COMMERCIAL POLY(ETHYLENE OXIDE-B-PROPYLENE OXIDE)

DEMULSIFIER BASES ON THE DEMULSIFICATION OF WATER-IN-CRUDE OIL EMULSIONS: ELUCIDATION OF THE DEMULSIFICATION MECHANISM

João Batista V. S. Ramalho

Petrobras Centro de Pesquisas, Av. Horácio Macedo, 950, Cidade Universitária Ilha do Fundão, 21941-915 Rio de Janeiro - RJ, Brasil

Fernanda C. Lechuga e Elizabete F. Lucas*

Instituto de Macromoléculas Profa. Eloisa Mano, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, CT, Bl. J, Ilha do Fundão, 21945-970 Rio de Janeiro - RJ, Brasil

Figure 1S. Demulsiier base performance on demulsiication of crude oil (a) P1, (b) P2 and (c) P3

Figure 3S. Voids generated by asphaltene adsorption at the water droplet surface. More voids are generated from small-sized asphaltene aggregates