Anna Kotyashko

Contested Views of the Responsibility to

Protect: The Cases of Brazil and Russia

Universidade do Minho

Escola de Economia e Gestão

Anna K o ty ashk o C o n te st e d Vi e w s o f th e R e sp o n si b il it y t o P rot e c t: T h e C a se s o f B ra z il a n d R u ss ia 1 7

Anna Kotyashko

Contested Views of the Responsibility to

Protect: The Cases of Brazil and Russia

Universidade do Minho

Escola de Economia e Gestão

Tese de Mestrado

Mestrado em Relações Internacionais

Trabalho efetuado sob a orientação da

Professora Doutora Laura C. Ferreira-Pereira

e sob co-orientação da

DECLARAÇÃO

Nome: Anna Kotyashko

Endereço electrónico: anna.kotyashko@gmail.com

Título dissertação: Contested Views of the Responsibility to Protect: The Cases of Brazil and Russia

Orientadores: Professora Doutra Laura C. Ferreira-Pereira e Professora Doutora Alena Vysotskaya Guedes Vieira

Ano de conclusão: 2017

Designação do Mestrado: Mestrado em Relações Internacionais

É AUTORIZADA A REPRODUÇÃO INTEGRAL DESTA TESE/TRABALHO APENAS PARA EFEITOS DE INVESTIGAÇÃO, MEDIANTE DECLARAÇÃO ESCRITA DO INTERESSADO, QUE A TAL SE COMPROMETE;

Universidade do Minho, ___/___/______

Assinatura: ________________________________________________

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My first expression of gratitude is to my supervisors, Professor Alena and Professor Laura Ferreira-Pereira, for their guidance and insightful comments. I am deeply honoured and indebted to their commitment, patience and words of encouragement.

I am grateful to my friends and colleagues for their sharp eyes and clever suggestions. This dissertation is stronger because of their valuable input.

To my parents, for their endless support and unconditional love.

CONTESTED VIEWS OF THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT: THE CASES

OF BRAZIL AND RUSSIA

ABSTRACT

The principle of Responsibility to Protect (RtoP) epitomises an answer to gross and systemic violations of human rights. Nonetheless, the implementation of RtoP is not a given and remains contested, for it has been caught in the conundrum of ensuring human security and respecting state sovereignty. As the normative evolution of RtoP has been occurring in parallel to important transformations of the world order, where emerging powers resort to normative resistance to raising their international influence, the principle has become a major point of divergence between key international players, notably within the United Nations. Drawing upon the norm diffusion theoretical approach, against the backdrop of the Critical Constructivist framework, the present dissertation analyses the contestation of RtoP in a compared perspective by taking Brazil and Russia as case-studies. According to the norm diffusion literature, foreign policy concerns, identities and self-perceptions play the major role in the adoption of divergent normative behaviour. Along these lines, the present dissertation shows that these countries’ reactions to RtoP reflect the roles that both seek to play in a changing global order. It concludes that while Russia, as a permanent member of the Security Council, has been able to afford the luxury of being the so-called ‘norm antipreneur’ and oppose RtoP without presenting an alternative to the RtoP principle; Brazil, in its pursuit of becoming a permanent member of the Security Council, has felt impelled to exhibit a stance that can be described as contesting entrepreneurship by putting forward the new concept of Responsibility while Protecting. The assessment of differences underlying the contesting views of Russia and Brazil provides us with valuable insights into the complexities of the norm diffusion process in times of emerging multipolarity.

Keywords: Responsibility to Protect; Normative Diffusion; UN Security Council; Russia; Brazil; Responsibility while Protecting

VISÕES CONTESTADAS DO PRINCÍPIO DA RESPONSABILIDADE DE

PROTEGER: O CASO DA RÚSSIA E DO BRASIL

RESUMO ANALÍTICO

O princípio da Responsabilidade de Proteger (RdP) traduz uma resposta a violações graves e sistémicas dos direitos humanos. No entanto, a implementação da RdP não é de todo garantida e continua a ser contestada, particularmente face ao dilema entre a segurança humana e a soberania. Visto que a evolução normativa da RdP tem ocorrido paralelamente a transformações importantes da ordem mundial, no seio da qual as potências emergentes adotam uma postura de resistência normativa visando aumentar sua influência internacional, esse princípio tornou-se um dos maiores pontos de divergência entre os principais atores internacionais, manifestando-se com mais intensidade nas discussões no âmbito das Nações Unidas. Tendo por base o framework teórico conhecido por difusão normativa (‘norm diffusion’), influenciado pelo do Construtivismo Crítico, a presente dissertação visa analisar a contestação da RdP numa perspetiva comparada, tendo o Brasil e a Rússia como estudos de caso. De acordo com os pressupostos teóricos da difusão normativa, diferentes conceções de política externa, identidades e de auto-perceções do papel internacional constituem as principais causas do comportamento normativo divergente por parte dos atores estaduais. Nessa linha argumentativa, defendemos que as reações da Rússia e do Brasil à RdP refletem os papéis que ambos Estados procuram desempenhar na atual ordem global em mudança. A presente dissertação conclui que, ao passo que a Rússia, enquanto membro permanente do Conselho de Segurança, teve condições de adotar uma atitude caracterizada na literatura como sendo de ‘norm antipreneur’ e objetar a implementação da RdP sem propor qualquer princípio alternativo, o Brasil, na sua ambição de conquistar um lugar no Conselho Permanente de Segurança, sentiu-se compelido a adotar uma postura aqui descrita como ‘constesting entrepreneurship’ (‘empreendedorismo contestatário’), ao propor um novo conceito de Responsabilidade ao Proteger. A análise das diferenças subjacentes às posições brasileira e russa em relação à RdP oferecida neste trabalho contribui para lançar luz sobre as complexidades do processo de difusão normativa em tempos de multipolaridade emergente.

Palavras-chave: Responsabilidade de Proteger; Difusão Normativa; Conselho de Segurança da ONU; Rússia; Brasil; Responsabilidade ao Proteger

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction ... 1

Objective ... 4

Research Gap and Added Value ... 7

Methodology ... 9

Structure of the Dissertation ... 11

1. The Emergence and Evolution of Responsibility to Protect ... 13

1.1 From the ‘Right to Intervene’ to ‘Responsibility to Protect’ ... 13

1.1.1 The 20th Century Tradition of Non-Intervention ... 15

1.1.2 ‘Humanitarian Turn’ in World Politics ... 17

1.1.3 Contesting Notions of Sovereignty ... 21

1.1.4 Conception of Responsibility to Protect: from Idea to Emerging Norm ... 23

1.1.5 2005 Onwards: Evolution of Responsibility to Protect ... 26

1.2 Norm Contestation and the Global Power Shifts ... 29

1.2.1. Theories of Norm Diffusion ... 29

1.2.2 Responsibility to Protect as a Composite Norm ... 33

1.3 Normative Power of Contestation ... 34

2. Case Study I: Brazil ... 39

2.1 Brazil’s Foreign Policy and Security Culture: The Defence of the Non-Intervention Tradition ... 40

2.1.1 ‘Paradigmatic Resilience’: Between Change and Continuity ... 40

2.1.2 Peacekeeping as a Power-Enhancing Instrument ... 47

2.1.2.1 ‘Brazilian Way’ of Peacekeeping: MINUSTAH as a Testing Ground ... 49

2.2 Brazil’s Reaction to Responsibility to Protect ... 52

2.2.1 From ‘Non-Indifference’ to Responsibility while Protecting ... 54

2.2.1.2 Regulating Military Intervention: A Case for Responsibility while Protecting ... 57

3. Case Study II: Russia ... 64

3.1 Russia’s Foreign Policy and Security Culture ... 65

3.1.1 Rising from the Ashes: A Thorny Road to Great Powers’ Club ... 65

3.1.2 Russia Resurgent: Increasing Great Power Assertiveness ... 69

3.1.3 A Tale of Russia as a Responsible Power ... 73

3.1.3.1 Paradox of Russian Peacekeeping ... 75

3.2 Russia’s Response to Responsibility to Protect ... 78

3.2.1 From Tolerance to Contestation ... 78

3.2.2 The ‘Imitation Game’: Cases of Intervention in Russia’s Backyard ... 81

4. Brazilian and Russian Approaches to Responsibility to Protect: A Comparative Perspective ... 87

4.1 Drawing Some Parallels ... 87

4.2 Implications of Russian and Brazilian Contestation for the Norm Evolution ... 96

Conclusion ... 99

Future Evolution of Responsibility to Protect and Possible Avenues for Further Research 105 Appendix ... 109

Table 2. RtoP in Crisis Situations, 2006-2016 ... 109

Annex 1 ... 112

Responsibility to Protect as formulated in the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document ... 112

Annex 2 ... 113

Peacekeeping Contributor Profile: Brazil ... 113

Annex 3 ... 114

Responsibility while Protecting: elements for the development and promotion of a concept . 114 Annex 4 ... 117

Peacekeeping Contributor Profile: Russia ... 117

Bibliography ... 119

Statements and Official Documents ... 119

LIST OF FIGURES

Table 1 - Stages of norm life cycle……….30

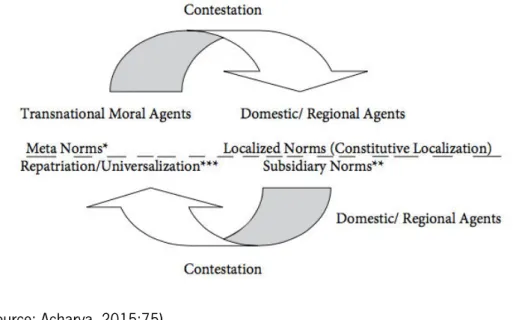

Figure 1 - Norm circulation………32

Figure 2 - The norm dynamics role-spectrum………36

Figure 3 – Alternative view of the norm dynamics role-spectrum………..90

Table 2 - RtoP in Crisis Situations, 2006-2016……….109

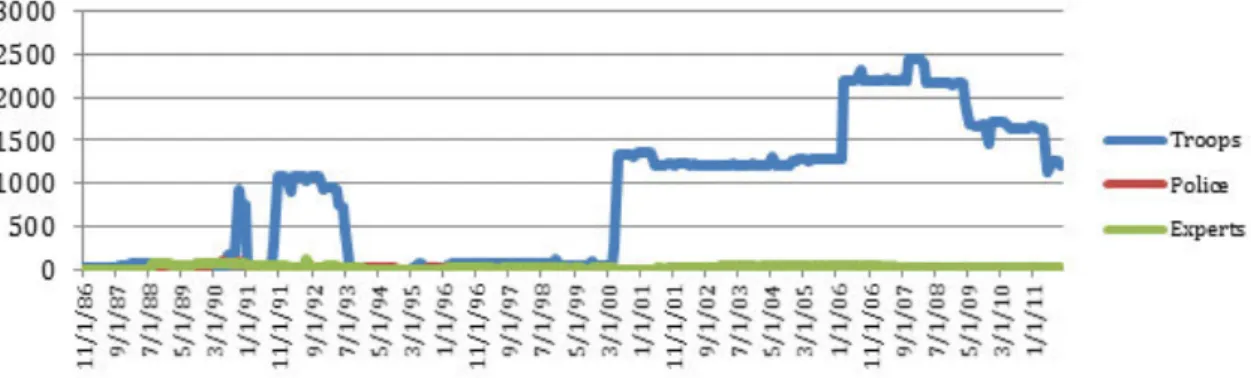

Figure 4 - Brazil’s Uniformed Personnel in UN Peacekeeping Operations, 1990-2015…113 Figure 5 - Russia’s Uniformed Personnel in UN Peacekeeping Operations, 1990-2016..117

ABBREVIATIONS

CIS Commonwealth of Independent States

CSCE Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe

CSCO Collective Security Treaty Organization ECOWAS Economic Community of West African States

EU European Union

GA General Assembly of the United Nations GCR2P Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect

ICISS International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty

ICRtoP International Coalition for the Responsibility to Protect

IDP Internally Displaced Persons

IICK Independent International Commission on Kosovo

INTERFET International Force for East Timor

MINUSTAH United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti

MONUSCO

United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

OAS Organization of American States OAU Organization of African Union

ONUMOZ United Nations Operation in Mozambique

P5 Permanent Members of the Security Council of the United Nations

POC Protection of Civilians

RtoP Responsibility to Protect RwP Responsibility while Protecting

SOD Summit Outcome Document

UK United Kingdom

UN United Nations

UNASUR Union of South American Nations

UNAVEM United Nations Angola Verification Mission UNDP United Nations Development Program UNEF I First United Nation Emergency Force UNFIL United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon UNSC Security Council of the United Nations

US United States of America

USSR Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

INTRODUCTION

The atrocities perpetrated in Rwanda, Srebrenica and Somalia in the 1990s appealed to the conscience of the international community about the value of human security and the limits of state sovereignty. Given the protection discourse (related to individuals in armed conflicts) 1 that

arose as a response to the shocking human rights abuses, the latter ceased to be seen as an unquestionable prerogative of states over the use of force. While previously considered a sole state responsibility to manage it as it sees appropriate, national sovereignty became subject to certain requirements. As stated by Newman, “the international legitimacy of state sovereignty rests not only on control of territory, but also upon fulfilling certain standards of human rights and welfare for citizens” (Newman, 2013:143). Therefore, when a state fails to respect the dignity and basic rights of all the people within its borders, its legitimacy becomes questionable. This notion of sovereignty as a ‘dual responsibility’ found expression in the emerging norm of ‘Responsibility to Protect’ (RtoP) (ICISS, 2001).

The concept of RtoP was first introduced in the report of International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS) in 2001 and soon was hailed “one of the most important developments in world politics in the last decade” (Thakur and Maley, 2015:3). Described as an “acknowledgment by all who live in zones of safety of a duty of care towards those trapped in zones of danger” (Ibid., emphasis added), it advocates that the international community has the right to act when a state, either due to the lack of ability or willingness, fails to protect its population. In an attempt to bridge the gap between the centuries-old tradition of non-interference and institutionalized non-indifference (Thakur, 2011a:12), RtoP was presented as a set of proposals ranging from the possibility to react to humanitarian crises to the responsibility to prevent such crises and, ultimately, transform failed and tyrannical states (Bellamy, 2008). The normative diffusion of the concept began at the 2005 World Summit, where the international community’s collective responsibility to protect peoples from the four crimes of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity was enshrined in the articles 138 and 139 of the Outcome Document, endorsed by world leaders without a vote (Rotmann et al., 2014).

Nevertheless, it has to be noted that political agreement around RtoP was not achieved without its share of criticism. Particularly after the unilateral invasion of Iraq in 2003 and its ex-post facto humanitarian justification, the nascent doctrine of contingent sovereignty was met with

1 The ‘protection discourse’ is characterized by the increasing concern about the protection of individuals during armed conflicts. For more

detailed information see: Adropoulos, George J. Lantsman, Leonid. 2010. “The Evolving Discourse on Human Protection”. Criminal Justice Ethics. 29(2): 73-92

a wide international backlash. The possibility of coercive protection under RtoP was equated by some with ‘right to intervene’ and an expression of military humanism, leading to conclusions that the principle might well be “buried in the dustbin of history” (Newman, 2009). In light of these major challenges, the advocacy of the then Secretary-General Kofi Annan proved to be of critical importance. As he emphatically noted, the United Nations (UN) had a “special burden” regarding the protection of human security, and if the organization was to rise to the challenge of meeting new threats the governments should “embrace” RtoP and “agree to act on it”2. Whereas

the inclusion of the principle in the final text of the 2005 Summit was not guaranteed, its acceptance by states was made possible by the particular way it was framed: as non-transformational and consistent with the prevailing conceptions of threats to international peace and security (Pollentine, 2012; Welsh, 2014). Moreover, as it was confined to four specific atrocity crimes and was to be considered on a case-by-case basis, the language used to circumscribe RtoP was oriented towards a long-term perspective of its implementation, as it increased its specificity and ultimately enabled RtoP’s endorsement.

However, the progression of RtoP after the World Summit was by no means assured, as profound disagreements remained about the meaning, significance and scope of the principle, hindering its operationalization. In order to overcome some criticism and clarify its mandate, on January 12, 2009, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon released a report titled Implementing the Responsibility to Protect. The outlined implementation strategy was designed through a “narrow but deep” approach to RtoP, intended to capitalize on “the whole prevention and protection toolkit” of the UN while strictly limiting the content of the principle to what was agreed to in 2005 (Bellamy, 2011:33). As such, it was divided into three pillars. The first pillar underlined that the primary and permanent responsibility for protecting populations lied with the state. The second one stressed the duty of the international community to assist states in fulfilling their responsibilities through the national capacity building, based on cooperation between states, international, regional and sub-regional organizations, civil society and private sector. The third pillar called for a timely and decisive response of the international community when a state was unable or unwilling to protect its population. This response ranged from peaceful measures under Chapter VI of the UN Charter, to the coercive Chapter VII and/or collaboration with regional and sub-regional agreements as referred to in Chapter VIII.

2 See Kofi Annan. 2005. In Larger Freedom: Towards Development, Security and Human Rights for All. Report of the Secretary-General of the

While the first two pillars have obtained broad declarative consent, the possibility of coercive measures under the third pillar has generated substantial controversy. Fears that RtoP could be transformed into an excuse to declare just wars and give carte blanche for humanitarian interventions in weaker countries (Tadjbakhsh and Chenoy, 2007, Rotmann et al., 2014) remained clamorous. Among the most vocal critics of the emerging norm and its eventual implementation based on coercive measures featured the BRICS countries (i.e. Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa). Such (re)emerging powers3 have often been depicted as

disrupters and opponents to RtoP, since they regard with scepticism the fact that the principle of non-intervention should yield to the international responsibility to protect, which might serve as a fig-leaf for powerful Western states to pursue their interests.

In the light of recent conflicts and crises in Africa and the Middle East, RtoP has been placed at the forefront of international discourse again. The “first road test” of the coercive action under the third pillar (Thakur, 2013) was carried out in Libya. The intervention was baptized as a “coming age” of RtoP (Evans, 2015a); however, its outcome was a mix of conceptual success and practical failure. It can hardly be denied that the operation Unified Protector4 was a

ground-breaking and a “spectacular step forward”, as it was based on the first of its kind Security Council (UNSC) resolution5 specifically invoking RtoP in a particular country situation and allowing

coercive measures without the government’s consent (Evans, 2011). However, the intense backlash that followed the overthrow of Gaddafi regime demonstrated the need for legitimacy criteria to guide decisions on authorizing and overseeing international military intervention. As a result, Syria has been paying the price of excess regarding the implementation of RtoP. As some have observed, “[t]here is no doubt that the bitter debate over whether NATO overstepped its Libya mandate has hampered efforts at the UN to consistently apply all the preventive, mediated and coercive elements in the RtoP toolkit” (Adams, 2012).

3 We chose to describe these states as ‘emerging rather than ‘rising’ for two reasons. First, it has to be noted that the adjectivizing the ‘BRICS’

members as ‘rising’ powers might be subject to contestation. As Jacobs and Rossem demonstrate, the acronym cannot be used as an analytical category of ‘rising powers’ since the paths of the BRICS to integration in the global political, economic and military networks differ fundamentally, culminating in widely divergent global power positions (Jacobs and Rossem,2013). Moreover, as Trinkunas and Mares demonstrate, the use of the term ‘rising’ implies a positive change in a set of state capabilities, namely GDP, military force or technological development. Conversely, ‘emerging’ implies legitimacy for a rising power’s participation on shaping the rules of global order (Mares and Trinkunas, 2016:5). Arguably, the rise of BRICS has not been linear, as all the countries have been experiencing political, economic and social crises, to varied degrees, however, their growing influence within international governance cannot be denied. Precisely because of the notion of the diffusion of power and the emergence of a multipolar international system, throughout the present dissertation we will refer to the BRICS members as ‘emerging’ powers.

4 The NATO Operation Unified Protector, which has enforced UNSC resolutions 1970 and 1973, consisted of three elements: an arms embargo, a

no-fly-zone and actions to protect civilians, using “all necessary measures” needed.

5The Resolution 1973, aiming to create the legal context for military intervention against Gaddafi government, was adopted with abstentions from

Objective

The main purpose of the present dissertation is to assess the evolution of RtoP against the background of its contestation by emerging powers. As Negrón-Gonzales and Contarino put it, norm consolidation is more than a one-way process of socialization, “but rather a give-and-take in which governments seek to adapt the meaning of global norms to fit their local normative context (localization) or even try to influence and modify global norms”, either through ways that seek to build broader support for them (soft feedback) or to limit their scope (hard feedback) (Negrón-Gonzales and Contarino, 2014). The dynamism of this normative interplay provides norm-takers with an opportunity to become norm-shapers, since they hold the capacity to influence the normative course of emerging norms. Furthermore, the emergence of a multipolar world, characterized by the diffusion of power, has created an enabling environment for the BRICS to compete in the highly contested normative space of international politics:

Emboldened, with voices amplified, and more able to resort to side-inducements such as promises of future diplomatic, financial or military support where normative argument fails, these states look better positioned than ever to instigate a reassessment of the balance between sovereign and individual rights which is central to the RtoP debate. (Morris, 2013:1280)

Among the five countries of the BRICS bloc, the analytical focus will be on the positions adopted by Russia and Brazil. The choice of these two particular countries is guided by the fact that both have expressed willingness to take increasing responsibilities in global governance and share the ambition to participate in the reform of the international order. Moreover, both countries have traditionally stressed the primacy of state sovereignty, as well as of the non-intervention as a bedrock of the international system, while both principles constitute fundamental precepts of their foreign policies (Averre and Davies, 2015; Burges, 2013; Kurowska, 2014;). However, it should be noted that there are differences between the two actors in question. On the one hand, while Russia is a permanent member of the UNSC, and thus finds itself in a privileged position within the global security architecture, Brazil continues to claim a seat in this influential body6, arguing that its old-fashioned structure lacks representativeness

(Brimmer, 2014).

6 At the meeting of Leaders of the G-4 countries Brazil, Germany, India and Japan on United Nations Security Council Reform, on 26 September

2015, “[the] G-4 leaders stressed that a more representative, legitimate and effective Security Council is needed more than ever to address the global conflicts and crises, which had spiralled in recent years. They shared the view that this can be achieved by reflecting the realities of the international community in the 21st century, where more Member States have the capacity and willingness to take on major responsibilities with regard to maintenance of international peace and security"

Given the suspicions that Brazil and Russia share about RtoP’s third pillar being used as a pretext for regime change and other self-serving political goals, it could be expected that the both countries had an equal attitude towards the diffusion of RtoP as an international norm. In fact, the backlash against RtoP that followed after the NATO’s overstretch of the UN mandate to use force to protect civilians in Libya and the subsequent removal of the Gaddafi government seemed to suggest a formation of a united block of Russia and Brazil , followed by other BRICS countries, in opposition to the West over the crisis in Syria. Nevertheless, as the situation in Syria worsened, the positions of Russia and Brazil over civilian protection measures under RtoP started to diverge (Garwood-Gowers, 2013).

Whereas demonstrating a wide support for the first two pillars of RtoP, prioritizing thus the state’s primary responsibility in protecting its populations and the provision of consensual state assistance by the international community, the two countries exhibit different approaches to the third pillar. While both share concerns on the efficiency of non-consensual, coercive measures, Russia has objected against its implementation, conflating the third pillar with forcible humanitarian intervention. Its position is made clear through the following statement in its 2013 Foreign Policy Concept:

13b. It is unacceptable that military interventions and other forms of interference from without which undermine the foundations of international law based on the principle of sovereign equality of states, be carried out on the pretext of implementing the concept of ‘responsibility to protect’. (Concept of the Foreign Policy of Russian Federation, 2013).

Yet, Brazil has assumed a more nuanced stance through the proposal of the complementary ‘Responsibility while Protecting’ (RwP) concept in order to “guide the international community in its robust actions during humanitarian crises” (Hamann, 2012). As RwP has been advanced in the midst of growing international frustration with the implementation of the UNSC Resolution 1973, it was meant to regulate, monitor and make RtoP more accountable (rather than rejecting it, or opposing it), attempting to reduce the legitimacy vacuum the principle has been facing after Libya.

Given that the normative evolution of RtoP has been occurring in parallel to the profound changes in the current word order, where the end of international leadership and the decline of great powers coexist with the de-universalization of norms and values, the future of this particular norm will necessarily depend on at least partial accommodation of the emerging states’ perspective (Garwood-Gowers, 2015:18-19). As such, the ongoing contestation over the RtoP

implementation has consequences that go beyond the principle itself, for it represents a “key rallying point in the ideational skirmishes from a changing global distribution of power” (Kenkel and Martins, 2016:22-23). The assessment of differences in the strategies of resistance adopted by Russia and Brazil provides us with valuable insights into the complexities of the norm diffusion process in times of emerging multipolarity. Our argument draws upon Amitav Acharya’s position, who argues that in order to understand how norms matter, one has to consider whose norms matter (Acharya, 2015:59). In this sense, interpretation of the nature and intent of the both actors involved in norm contestation can be revealing of their bigger ambitions regarding influence in global governance.

In order to study the Russian and Brazilian diverging views regarding RtoP as part of the emerging powers’ influence-seeking approach, the present research adopts the following guiding question: What are the similarities and differences between the Brazilian and Russian perspectives of the RtoP principle and How they reflect the two actors’ different conceptions of identity and self-perception of their international position?

The analysis will focus on the official positions of Russia and Brazil on RtoP and the impact that these have on the international consolidation of the principle. For this purpose, in terms of temporal limitations, the study will range from 2001 to 2016, more specifically the month of September. The year of 2001 has been chosen because it corresponds to the year when the RtoP concept was first articulated by the ICISS report. While the formal birth of the principle is considered to be the 2005 World Summit, which represented the ‘tipping point’7 of its normative

formation trajectory, the time of four years prior to its adoption had been important for the formulation of initial responses to RtoP as well. The year of 2016 follows the 10th anniversary of

the principle, celebrated on September 16 - the day it was endorsed at the 2005 World Summit Outcome Document - and provides a useful opportunity for the assessment of the progress made so far and the lessons learned. Moreover, 2016 represents the year of major challenges both for RtoP as well as Russia and Brazil. On the one hand, the ongoing Syrian conflict has no end in sight, while the deterioration of the humanitarian crisis raises doubts regarding the continued relevance of RtoP. On the other hand, 2016 is the year of the controversial impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff, on 31st of August, who was responsible for the advancement of RwP at

the UN. As for Russia, various developments during 2016, most notably the extension of its

7 According to Finnemore and Sikking, the ‘tipping’ point occurs when a critical mass of relevant state actors adopt the norm (1998). Beyond it,

campaign in Syria – its first military intervention outside the former Soviet Union (USSR) since the 1991 Soviet collapse – showcase Moscow’s increased assertiveness. Moreover, its continued ‘deniable’ engagement in the ongoing conflict in Donbass region of South-eastern Ukraine represents one of the critical cases that constitute a “continuous test” for the assessment of various aspects of Russia’s foreign policy, including those related to RtoP (Baranovsky and Mateiko, 2016:58).

Assuming Critical Constructivism as a theoretical framework, the initial hypothesis of the present dissertation is grounded on the assumption that the contesting views of RtoP expressed by Russia and Brazil will reflect the different roles that both countries seek to play in a changing global order based on their own conceptions of identity and self-perception of their international position. In the Russian case, the conduct of more assertive foreign policy translates into objection and a more direct and assertive resistance to liberal norms. As for Brazil, it wants to position itself as a mediator, acting as a consensus-seeker in the debate about prevention, intervention and RtoP. While capitalizing on its soft power base and the long-standing tradition of negotiation and peaceful resolution of disputes, it attempts to raise its international profile through the emphasis on its comparative advantage of being a “bridge between old and new powers” (Burges, 2013) and the possibility of mediating “extreme international behaviour on all sides” (Patriota, 2013). In light of this, contestation of the principle assumes a different form and follows a different rationale. Whether through such soft feedback by Brazil or hard feedback by Russia regarding RtoP, both states have been engaged in processes of normative reframing, meaning that instead of simply accepting the rules, both intend to influence their internationalization, evolving from norm-takers into norm-shapers.

Research Gap and Added Value

Most of the theory-informed literature on RtoP assesses its normative development through the constructivist theoretical framework of the norm life-cycle model (Welsh, 2014; Ziegler, 2015), according to which the norm influence may be understood as a three-stage process, encompassing norm emergence, followed by norm cascade and internalization (Finnemore and Sikkink, 1998:895). When this last stage is completed, “norms acquire a taken-for-granted quality and are no longer a matter of broad public debate” (Ibid.). Through these theoretical lenses, the threshold of norm emergence was reached at the point of the adoption of World Summit Outcome, meaning that after this watershed moment RtoP acquired a quality of a soft

norm and entered the stage of socialization and institutionalization. One would expect a linear progression of RtoP to internalization following this moment; however, its continuing contestation blurs the division lines between different stages of norm evolution. As a result, more recently, academic attention has been directed at the impact of contestation and agency influence on the advancement of international norms. This focus on mechanisms of norm diffusion contributed to the emergence of new insights, according to which new norms are rarely adopted wholesale, but, instead, are localized and translated to fit the context and need of a norm-taker (Acharya, 2015).

Since emerging powers are seen as main opponents to the implementation of RtoP, most of the contributions to this research focus on the contesting views of the BRICS (Brockmeier et al, 2016b; Garwood-Gowers, 2013; Laskaris and Kreutz, 2015; Thakur, 2013). However, few studies have systematically explored how these views are formed and what accounts for the variation in emerging powers’ normative stances. Although there is some literature on individual perspectives of BRICS members with regard to RtoP, it is still rather limited compared to the abundance of articles on normative features and shortcomings of the principle. Therefore, the present dissertation sets out to fill a research gap by analysing the contestation of RtoP through the compared assessment of Brazilian and Russian positions, focusing on differing foreign policy concerns, identities and self-perceptions as main drivers of divergent normative behaviour. This approach aims not only at contributing to a better understanding of the impact that contesting views of two (re)emerging powers have on RtoP normative diffusion, but also to analyse how aspirations of a more influential international role have been translated into normative reframing.

While the normative resistance to the Western form of humanitarian intervention is present in the foreign policy discourses of both countries, responses to the RtoP’s third pillar take different forms. In the case of Russia, its view of global norms related to military intervention is to a significant extent interrelated with its conceptions of international, regional and domestic state order (Allison, 2013; Averre and Davies, 2015; Kurowska, 2014). This becomes evident in Moscow’s contradictory position on RtoP and inconsistencies in its argumentation for military intervention. Internationally, Russia presents itself as a ‘responsible power’ and a strong defender of the principle of intervention and international law, objecting to any possibility of non-consensual coercive measures in conflicts like civil war in Syria. However, these actions stand in stark contrast with its own practice regarding protection of Russian-speaking citizens in neighbouring countries, like in Georgia or Ukraine, which sometimes entails coercive actions,

including the use of force (Kurowska, 2014). The present dissertation aims to examine the factors explaining Moscow’s controversial position.

Brasília’s quest for global actorness has found expression in its RwP initiative. As an aspiring power, viewing itself a “latecomer to the club of great powers” (Rohter, 2010), Brazil needed to develop a notion of RtoP consistent with its international profile (Kenkel, 2008). Since president Luís Inácio Lula da Silva’s time in the office (2003-2010), Brazil adopted an “active and self-confident” foreign policy (Almeida, 2006) in its attempt to assert itself as an influential international actor. The idea of ‘Power Brazil’ (‘Brasil Potência’), as an expression of the country’s willingness to take on increasing commitments and responsibilities in the international arena (Ferreira-Pereira, 2016:62), was ultimately articulated through the posture of ‘non-indifference’. Defined as a demonstration of ‘active solidarity’ in the face of crisis situations whenever a country’s action was requested and whenever it could play a positive role (Almeida, 2013), the attitude of ‘non-indifference’ found its ultimate expression in Brasília’s diplomatic engagement in several intrastate crises as well as its growing willingness to participate in UN peacekeeping operations, including the ones under the Chapter VII. Whereas under the presidency of Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016) the political dynamism of a globally oriented foreign policy has decreased, particularly due to the government’s concerns with major domestic issues, some degree of foreign policy activism was retained (Ferreira-Pereira, 2016:63). Among its most visible expressions was the launching of the concept of RwP. Although the emergence of RwP has been explored in the literature, there is still room for further research, especially on how this attempt of normative entrepreneurship is related to the Brazilian global performance over last years, in particular through its assessment in a comparative perspective with the Russia’s global orientation.

Methodology

As indicated by the research question, the main concern of this dissertation, which focuses on the Russian and Brazilian perspectives of RtoP, brings us to the inter-subjective and ideational realm of international politics, where, depending on the context, the same phenomenon can have different meanings. Since perceptions are not susceptible of quantification, the most appropriate methodological approach will be interpretative (Coutinho, 2011). This approach is “oriented toward discovery and process (…) [and] is more concerned with deeper understanding of the

research problem in its unique context” rather than with generalizations (Ulin et al, 2004, apud Tuli, 2010).

Therefore, a prime goal of the present inquiry is to discover why and how emerging powers engage in normative international debates. Since it is acknowledged that “the strongest means of drawing inferences from case studies is the use of a combination within-case analysis and cross-case comparison” (George and Bennett, 2005:31), we will resort to the parallel assessment of normative behaviours presented by Russia and Brazil, complemented by the process-tracing method for identifying the intervening causal processes that lead to the formation of contested views of RtoP. This dual case-study falls within the ‘building blocks’ research objective, which aims at determining common patterns (George and Bennett, 2005), as well as idiosyncratic differences, accountable for the divergent normative positioning of two (re)emerging powers.

In order to proceed with it, we will look into both their strategic cultures, regarding the matters of state sovereignty, security and intervention, and respective international identities. For this purpose, primary (Concept of Foreign Policy, Strategic Concept of National Defense and Security) and secondary sources of information will be examined. Among the primary sources feature Concepts of Foreign Policy [Концепция Внешней Политики Российской

Федерации (Concept of Foreign Policy of the Russian Federation); Repertório de Política

Externa: Posições do Brasil (Directory of Foreign Policy: Positions of Brazil)] as well as Strategic Concepts on National Defense and Security [for Russia - Военная Доктрина Российской

Федерации (Military Doctrine of the Russian Federation); Стратегия национальной безопасности Российской Федерации (National Defence Strategy of the Russian

Federation); for Brazil - Estratégia Nacional de Defesa (National Defence Strategy); Política Nacional de Defesa (National Defence Policy); Livro Branco de Defesa (Defence White Paper); Doutrina Militar de Defesa (Military Defence Doctrine)]. The main method of data interpretation will be qualitative content analysis, which comprises a search-out for underlying themes in the documents to be analyzed (Bryman, 2012: 392). Moreover, the critical analysis of government statements on RtoP will be an important tool for a better understanding of the drivers of their contestation of this developing norm8.

8 Although the main style of in-text citations throughout the present dissertation follows the author-date system, the reference of official statements

will be made in footnotes. Taking into consideration a large number of primary sources subject to analysis, this choice was made with an intention to differentiate statements of government officials and UN representatives from articles that the same people have written on other occasions. In this sense, the resort to footnotes aims to make the work more reader-friendly and increase its accuracy.

Structure of the Dissertation

The outline of the present dissertation will be divided into four parts. As the central analytical focus is on the normative development of RtoP through the prism of both Brazil and Russia, Chapter 1 examines the international context underlying the inception of the principle. Firstly, the available literature on the transition from the right of intervention to the international responsibility to protect will be analysed. With this, we intend to differentiate between humanitarian interventions, based on a state-centric logic of security, from RtoP, imbued with principles of human security. Afterwards, we focus on the processes of norm diffusion and how and under what conditions emerging powers’ engagement in norm contestation results in a norm modification.

The two subsequent parts address the contested internalization of RtoP, focusing on Brazilian and Russian perspectives, in Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 respectively. The positioning of each country is assessed in the light of their international aspirations. Both chapters are structured in a symmetrical manner for the purpose of facilitating further comparison and allowing for the illumination of common threads and/or points of divergence. To this end, the guiding principles of each country’s foreign policy are examined in the period from 2001 to 2016. Moreover, special attention is paid to their security cultures, particularly their historical determinants as well as contemporary relevance. In addition, we intend to assess Brazil’s and Russia’s position towards peacekeeping operations, in general, and military interventions in particular. The focus on how these countries understand the function and purpose of peace operations allows us to better comprehend the particularities of their stance regarding RtoP. With this in mind, our analysis covers some periods prior to 2001, since a historical perspective can be of particular relevance, as it is in the case of Russia and its experience with conflicts in its immediate neighbourhood during the 1990s. At last, we address under what conditions and for what purpose both countries resorted to RtoP rhetoric, either to complement the norm - as demonstrated by Brazilian initiative of RwP - or to justify interventions - as was the case of Moscow’s legitimation discourse of its Georgian intervention in 2008 and the swift annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Finally, Chapter 4 is dedicated to the comparative analysis of the both case studies. After analyzing Brazil’s and Russia’s stances regarding interventions, informed by their particular normative baggage and background experiences, we proceed with the assessment of processes

of resistance and strategies deployed to contest RtoP. There are some common threads between the two actors’ approaches, particularly their traditional support of sovereignty and the principle of non-interference. As a result, Russian and Brazilian initial discursive resistance followed a similar line of light criticism and limited acceptance, just until 2011. However, after the intervention in Libya their positions have diverged considerably. In the light of the NATO’s overstretch of UN mandate, Moscow has underlined recurrently the susceptibility of RtoP to expedient abuse and consequently opposed to any possibility of another Libyan-scenario, exercising its power of veto whenever needed. Brasília, on the other hand, has attempted to play a more constructive role in calling for more caution in implementing RtoP’s third pillar through RwP. We will assess how these different reactions are related to Russian and Brazilian international identities and what are the main drivers of change in their resistance. It can be stated, however, that a degree to which normative contestation of emerging powers matters reflects their political position, varying in accordance with the issue in question. Thus, regarding peace and security, the definition of standards of appropriate behaviour reflects both changing distributions of power and hierarchy of prestige, with a special role reserved for Permanent Members (P5) of the UNSC. This means that Moscow enjoys an asymmetrical advantage – the veto power – which serves as a power multiplier for its resistance. This, in turn, enables it to play the role of ‘norm antipreneur’ and object and resist RtoP’s implementation, without presenting any alternative to the principle. Conversely, Brasília adopts a differentiated approach to advance its reservations. While agreeing with the imperative of civilian protection, it questions the putative utility of force as means of maintaining peace and international security. As a demonstration of its willingness to take on increased international responsibilities, Brazil has sought to influence the debate on RtoP by adopting a stance of contesting entrepreneurship through the advancement of a complementary principle of RwP. Accordingly, instead of simply criticizing the shortcoming of RtoP, Brazil has attempted to reduce the legitimacy gap RtoP has been facing after Libya, while at the same time raising the threshold for the use of force. The different strategies of resistance deployed by these two actors showcase the normative power of contestation and the inherent complexities of norm diffusion.

CHAPTER 1

1. The Emergence and Evolution of Responsibility to Protect

RtoP epitomises an answer to mass atrocity crimes that contradict every precept of our common humanity and human dignity. As such, like human rights more generally, the principle aims to overcome cultural boundaries and ultimately aspires to universality (Serrano, 2011:104). However, the emergence of RtoP cannot be understood apart from the changing international context in which it occurs. According to Martha Finnemore, norms represent systemic-level variables in both origin and effect (Finnemore, 1996), and because they are intersubjective, rather than merely subjective, they evolve through complex interaction between structure and agency. In this chapter, the first section will assess the normative development of RtoP through the examination of its historical precedents. This overview is meant to provide an appropriate background for analysis of distinctive features of RtoP and look beyond the oft-repeated argument that the norm is simply “old militarism in a new bottle” (Bellamy, 2009). It will be followed by the review of existing literature on norm diffusion and a role that contestation plays in it.

1.1 From the ‘Right to Intervene’ to ‘Responsibility to Protect’

Humanitarian interventions9 have long been considered a contradiction in terms. Ever since

arguments have been advanced for a right of intervention to protect populations from mass atrocities, their legitimacy has been eclipsed by the shadow of potential abuse. The concern that states would exploit a humanitarian exception to justify military aggressions, motivated by strategic, economic, or political interests, has long dominated the debate about the politics of intervention. Although it might seem that the political battle over ‘saving strangers’ is a 1990’s phenomenon, its roots trace back a long way. As Glanville points out, theorists have been confronted with this problem of abuse for over 2000 years. He gives us examples of ‘benevolent rulers’ in the multi-state system of ancient China, whose duty was “to punish tyrants, suppress disorders, remove the unprincipled and attack the unrighteous” (Glanville, 2014:149). This argument of a punitive war is closely associated with a just war doctrine, derived from the Greco-Roman tradition, Christian ethics, and Western philosophy. In his De Jure Belli Ac Pacis of 1625, Hugo Grotius defended the right of sovereigns, “vested in human society”, to punish those who

9 Drawing upon the definition provided by J. L. Holzgrefe, we consider the humanitarian intervention to be the threat or use of force across state

borders by a state (or a group of states) aimed at preventing or ending widespread and grave violations of the fundamental human rights of individuals other than its own citizens, without the permission of the state within whose territory force is applied” (Holzgrefe, 2003:18). This ‘narrow’ consideration accounts only for forcible action without State’s consent, excluding two other types of behaviour occasionally associated with the term, namely non-forcible interventions such as the threat or use of economic, diplomatic, or other sanctions;and forcible interventions aimed at protecting or rescuing the intervening state’s own nationals.

“exercise such Tyrannies over Subjects, as no good Man living can approve of” (Bass, 2008:4). He bases this right on the natural law notion of societas humana – the universal community of humankind (Holzgrefe, 2003:26). Furthermore, he argued against the problem of abuse, noting that just because a principle can be misused does not necessarily make the principle itself unjust: “…but the Use that wicked Men make of a Thing, does not always hinder it from being just in itself. Pirates sail on the Seas, and Thieves wear Swords, as well as others” (Grotius, 1625, apud Glanville, 2014:155; emphasis in original).

The debate over the ends and means of humanitarian intervention was further explored in the late 18th century through works of moral philosophers such as Immanuel Kant10 and Stuart

Mill11, who, albeit arguing for state legitimacy as the basis for adhering to non-intervention,

reserved the right of intervention to protect human rights. Michael Walzer12 presents a modern

version of this argument, allowing intervention in exceptional cases “that shock the moral conscience of mankind” (Tesón, 2003). In his view, a duty of humanitarian intervention13 is just

because it “fits” the “inherited cultures” of political communities everywhere (Walzer, 1980, apud Holzgrefe, 2003:33).

Apart from these intellectual precursors, Europe’s Oriental policies during the 19th century

evidenced humanitarian intervention in its actual practice. During this period, moral justifications for repeated interventions14 of European powers against the Ottoman Empire were based on

humanitarian appeals to stop “‘excesses of injustice and cruelty’ that deeply injure European-Christian morals and civilization” (Köchler, 2001:2). This kind of humanitarianism, often

10 Kant develops an idea of ‘common morality’, according to which “human beings have rights not as members of this or that community but as

members of the human community.” Applied to the particular issue of humanitarian intervention, the Kantian logic runs like this: 1) human beings, as rational agents, are owed respect; and 2) respecting other human beings means not only refraining from interfering with their freedom, but also assisting them in achieving their ends (Welsh et al, 2002:501). The issue is extensively discussed at Hill, Thomas. 2009 “Kant and Humanitarian Intervention”. Philosophical Perspectives 23(1):221-240;

11 Mill argued that ‘civilized’ nations had a right to intervene in ‘barbarous’ ones in order to meet out to them 0such treatment as may fit them for

becoming’ civilized. (Mill apud Howorth, 2013)

12 His book Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations is considered to be a classic of just war doctrine. It examines the

moral issues surrounding military theory, war crimes, and the spoils of war through the assessment of a variety of conflicts over the course of history: from the Athenian attack on Melos to the My Lai Massacre, from the wars in the Balkans to the first war in Iraq. Walzer claims that humanitarian intervention is an ‘imperfect duty’: “The general problem is that intervention, even when it is justified, even when it is necessary to prevent terrible crimes – even when it poses no threat to regional or global stability, is an imperfect duty – a duty that doesn’t belong to any particular agent. Somebody ought to intervene, but no specific state or society is morally bound to do so.”

13 For a more profound discussion see Nardin, Terry. 2013. “From Right to Intervene to Duty to Protect: Michael Walzer on Humanitarian

Intervention”. The European Journal of International Law. 24(1):67-82

14 The often-cited cases relate to the Greek War of Independence (1821-1827), Syria (1860-1861), and Armenia (1894-1917). The ‘self-declared’

humanitarian mission of European powers was documented in the Act of the Holy Alliance: “We who deny the general abstract right of interference, but admit the possibility of interfering in cases of specific interests or specific obligations” (Bass, 2008:354). Its practice displayed the double-standards of the epoch: “sovereignty in Europe, imperial bullying in the weak and ostensibly barbarous periphery” (Bass, 2008:352).

described as a ‘new imperialism’, exploited the claim for the respect of human rights as an accessory motive of intervention15 and underlined the problem of expedient abuse.

1.1.1 The 20th Century Tradition of Non-Intervention

During the 20th century, the doctrine of humanitarian intervention underwent profound

changes. In particular, three moments of ideological reorientation can be identified. The first one coincided with the period after the First World War, following the collapse of the old European order of the 19th century. Another critical moment for the humanitarian cause was provided by

the reconstruction of the international system after the Second World War and the adoption of the UN Charter. At last, the end of the Cold War and the consequent ‘humanitarian turn’ in world politics present us with the third moment of ideological reorientation.

In the aftermath of the First World War, the magnitude of destruction and the scale of atrocities exposed the dangers of an absolutely posited state sovereignty. As Köchler observes,

What has been aptly described, in German terminology, as Souveränitäts- anarchie - anarchy among sovereign states as a result of the unrestrained exercise of that very sovereignty - had become the most serious threat to international peace and security, indeed to the survival of mankind, and was perceived as such by a growing number of scholars, diplomats and politicians. (Köchler, 2001:9)

Consequently, this has led to the abrogation of the jus ad bellum (right to war)16 and led to

the banning of the use of force in international relations17, which constituted a major step towards

an international order of peace and prosperity for all nations (Ibid., 2001:9). Nevertheless, this order of peace was precarious, collapsing only two decades after in the conflagration of the Second World War.

In the wake of the Second World War, the tragic legacy of Holocaust was translated into a haunting slogan of ‘never again’, which, in turn, forged the “moral universalism (…) predicated on humanity’s shame at its ‘abandonment of the Jews’, which created ‘a new kind of crime: the crime against humanity’” (Ignatieff, 1986, apud Wheeler, 2000:302). The reconstruction of the international system in the post-1945 period comprised the establishment of laws prohibiting

15 In his book, Freedom’s Battle (2008), Bass recognizes this problem and notes that great powers are guided by their own material interests:

“After all, governments are opportunistic in their humanitarianism, as they are with any military venture: believing in human rights does not make one suicidal” (8). Through the comprehensive assessment of several cases of humanitarian interventions in the 19th century, he attempts to

deepen the understanding of their true motives and go beyond the arguments of ‘hegemonic interests’ to demonstrate that “[even] in the heyday of imperialism and realpolitik, the politics of human rights made a big impact on foreign policy” (6).

16 Notably, the jus ad bellum tradition had been already subdued through the development of norms of jus in bello (humanitarian principles of the

conduct of warfare) introduced by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907.

17 The banning of the use of force was codified though the Kellogg-Briand Pact of 1928 (officially General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy). It was further complemented by the procedural restrictions of the right to conduct war included in the Covenant of the League of Nations, which Article 10 clearly prohibited wars of aggression and threats of aggression against members of the League.

genocide, forbidding the mistreatment of civilians, and recognising basic human rights (Bellamy and Wheeler, 2008). As a “beacon for all humanity”18, the UN system was designed to “save the

succeeding generations from the scourge of war” (United Nations, 1945).

On the one hand, the UN Charter reinforced the limits imposed upon the use of force, stipulating the non-intervention as a corollary of state sovereignty in its Art. 2 (4)19. Accordingly,

the use of force was only acceptable in the case of legitimate self-defence (Art. 51) or collective security measures under Chapter VII of the Charter, “as may be necessary to maintain or restore international peace and security” (Art. 42). On the other hand, the Charter contained several provisions for the development of human rights as a global issue which were further reinforced by other relevant instruments, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Since the humanitarian intervention represents the most assertive form of promoting human rights, it was clearly not compatible with the norm of non-intervention and was effectively rendered illegitimate. In this way, the UN Charter epitomizes the core of the humanitarian dilemma - a tension between sovereignty and human rights. Indeed, “the balance between state and individual right (…) was struck firmly in favour of the sovereignty of the former” (Morris and Wheeler, 2012, apud Morris, 2015:3). One major agreed exception to the non-intervention principle was the Genocide Convention of 1948. However, as Bellamy argued, the signing of this convention was not followed by practical implementation of its terms (Bellamy, apud Evans, 2015b:276). Due to the bipolar opposition, the UNSC was often paralysed by the reciprocal operation of the veto20,

hindering the possibility of collective action endorsed by the UN. In these circumstances, several cases of unilateral interventions took place, mostly motivated by reasons related to strategic security21.

18 This expression was used by the incumbent UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon at his message on United Nations Day, on 24th of October of

2015. Available at: http://www.un.org/press/en/2015/sgsm17246.doc.htm

19 “All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence

of any state (…)”

20 For a comprehensive discussion of the role of the UN in peacekeeping during the Cold War see: MacQueen, Norrie.1999. The United Nations

Since 1945: Peacekeeping and the Cold War. Addison-Wesley Longman.

21 The Soviet Union interventions in the former Czechoslovakia in 1968 and in Afghanistan in 1971, US interventions in the Dominican Republic in

1965 and Grenada in 1983, India’s intervention in Bangladesh in 1971, Tanzania’s in Uganda in 1979, and Vietnam’s resort to force in Cambodia in 1979 are a few examples (Badescu, 2010:22). The case of Vietnamese intervention is of particular relevance. After invading Cambodia to displace the Khmer Rouge, which had terrorized the country since April 1975, Vietnam received widespread international condemnation. The Khmer Rouge’s crimes against humanity had taken the lives of somewhere between 2 and 3 million Cambodians – an estimated quarter or a third of the entire Cambodian population. The outrageous images of the killing fields made it clear that although “Hanoi’s motives may have been neither pure nor humanitarian, its intervention did stop the génocidaires in their tracks” (Evans, 2015:277). Falk summarises the international posture of reproof as “based on geopolitical calculations in the face of the extremity of humanitarian considerations: it was deemed more important, in effect, to avoid the extension of Vietnamese influence and to placate China (then hostile to Vietnam) than to relieve the people of Cambodia from the grotesque burden imposed on their lives by the Khmer Rouge regime” (Falk, 1995:505). Three decades after, the problem of regime change vs the responsibility to protect endangered populations is again in stark display in Syria.

With the advent of globalization and increase in media accessibility, the coverage of mass atrocities crimes brought the attention of people throughout the world to the suffering of other. This empathy framing resulted in the so-called CNN effect in support of victims of human rights abuse, thus contributing to a demand for robust policy responses and, consequently, putting the sacrosanct principle of state sovereignty under strain. Among the building-blocks of the protection discourse was the emerging notion of the ‘right to intervene’ (originally le droit d’ingérence), coined in the late 1980s by politician Bernard Kouchner. Greatly influenced by the Biafra famine22, Kouchner advocated for the tradition of ‘political humanitarianism’, arguing that

“political and humanitarian action could not and should not be disassociated” (Weiss, 1999:2). It comprised two solidarity principles such as the ‘freedom of criticism’ or ‘denunciation’ and ‘the right of intervention’ on humanitarian grounds, associated with the notion of ‘subsidiarity of sovereignty’ (Chandler, 2001:5). It has to be noticed that this approach focused primarily on humanitarian relief and, therefore, any intervention on its terms did not entail stopping the actual fighting that was causing the humanitarian crisis. Albeit its valuable contribution to the history of humanitarianism, for it signalled a departure from a traditional understanding of state sovereignty, it was largely contained within France until the 1990s.

1.1.2 ‘Humanitarian Turn’ in World Politics

The end of the Cold War was a turning point towards the increasing “humanization of international relations” (Bogliolo, 2009:19). Against the backdrop of possible threats of conventional wars between states or groups of states, sub-conventional conflicts - ranging from intra-state conflict to global terrorism - have started to gain prominence. The horrendous reality of civil wars and internal atrocities perpetrated on a massive scale as witnessed in several conflicts during the 1990s reminded the world that the state itself can be a source of insecurity (Ayoob, 2005). As a result, the idea of the state as a Leviathan, whose authority and the legitimate exercise of monopoly over violence were supposed to ensure the security within and beyond its

22 In the context of the Nigerian Civil War (1967-1970), between the self-declared secessionist nation of Biafra and the independent nation of

Nigeria, one of the tactics of the central government to force the rebels into negotiations consisted in denying them access to humanitarian assistance. Since the stance of aid agencies had traditionally been to adopt a strict line of impartiality, neutrality, and independence, the absence of state consent impeded aid agencies to intervene. Subsequently, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) suspended its airlift in Biafra and gradually ended its activities in the conflict22. As a member of ICRC, Kouchner along with his other fellow colleagues were shocked by

the organisation’s response to the situation on the ground and its policy of confidentiality. He argued that the silence over “state policy of forced starvation and migration” in Biafra made ICRC’s workers “accomplices in the systematic massacre of a population” (Allen and Styan, 2000:830). The objections against traditional approach to humanitarian assistance were translated into the foundation of a new agency, Médecines sans Fentières (MSF), the first non-military, non-governmental relief organisation to specialise in emergency medical assistance ‘without borders’. As James Orbinski stated, on accepting the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of MSF: “Our mission is very simple. It is to seek to relieve suffering, to reveal injustice, to provoke change, and to locate and insist upon political responsibility”. Therefore, MSF has since been perceived as a symbol of the ‘new humanitarian’ cause. For more profound discussion, see, for example, Torrelli, Maurice. 1992. “From humanitarian assistance to “intervention on humanitarian grounds”?”. International Review of the Red Cross. 32 or Chandler, David C. 2001. “The Road to Military Humanitarianism: How the Human Rights NGOs Shaped a New Humanitarian Agenda”. Human Rights Quarterly.23(3):678-700.